Abstract

In agricultural lands, cadmium (Cd) and lead (Pb) co-contamination poses a significant threat to soil health and crop safety. This study evaluates the ryegrass-maize intercropping system as a sustainable approach to mitigate these environmental challenges. A 120-day pot experiment was conducted, revealing that the intercropping system significantly reduced soil Cd and Pb, achieving residual levels below national risk thresholds. Maize grains were confirmed safe, while ryegrass acted as an efficient bioaccumulator. The system enhanced soil ecosystem services, evidenced by a significant increase in key soil enzyme activities and nutrient cycling indicators. Specifically, the intercropping system boosted the activities of catalase, alkaline protease, and urease, which are crucial for redox regulation and nitrogen cycling. Notably, the activity of alkaline protease, responsible for organic nitrogen decomposition, increased by approximately 18.5 times in the intercropping group. Furthermore, the system increased soil organic matter by 5.89%, a core indicator of soil fertility and carbon sequestration, a key supporting service. Habitat sustainability was substantiated through the analysis of microbial community structure and diversity. Although Cd-Pb contamination initially reduced microbial diversity, the intercropping system (C2) mitigated this decline more effectively than monoculture (C1). More importantly, the intercropping system enriched metal-tolerant and functionally critical microbial taxa, such as Actinobacteriota, whose relative abundance reached 43.99% in the C2 group after the experiment. Despite observed phosphorus depletion, which suggests the need for targeted fertilization, the findings support ryegrass-maize intercropping as a viable, nature-based solution for soil remediation. This scalable strategy not only addresses contamination but also supports sustainable land management, contributing to the resilience and restoration of degraded farmlands.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Industrialization, rapid urbanization, and the intensive use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides have led to a serious accumulation of heavy metals in agricultural soils1. The National Soil Contamination Survey Bulletin reports that the overall exceedance rate of soil pollutants in China is 16.1%, with an even higher exceedance rate of 19.4% for arable soils2. Cadmium (Cd) and lead (Pb) are the most common contaminants, these two metals inhibit cell division, protein metabolism, respiration, and photosynthesis, ultimately causing plant cell death3,4. Moreover, when multiple metals coexist, they alter the speciation of each other, increasing the bioavailable fraction and thereby intensifying phytotoxicity5. Understanding how metal speciation changes under complex Cd‑Pb pollution is therefore essential for elucidating plant toxic responses.

Ryegrass (Lolium perenne) is increasingly employed in intercropping systems to capture Cd and Pb from contaminated fields. When intercropped with garlic, ryegrass not only maintained its own growth but also enhanced the uptake of Cd, Cr and Pb by the companion crop, demonstrating a positive correlation between biomass production and metal accumulation6. Similar synergistic effects were reported for ryegrass‑maize intercropping, under single Cd stress, ryegrass roots achieve a Cd bioconcentration factor (BCF) of ≈ 3.06, confirming the root as the primary accumulation organ7. Intercropping ryegrass with other species (e.g., Bidens spp., Solanum nigrum, Vicia faba) further highlighted the role of root‑secreted organic acids (oxalic, tartaric, citric) and the enrichment of beneficial microbial taxa in the rhizosphere, both of which improve metal bioavailability and plant uptake8. These studies collectively suggest that ryegrass can act as a “metal‑capture” component in mixed‑crop arrangements, improving soil structure, nutrient cycling, and overall remediation efficiency while preserving agricultural productivity.

Under combined Cd‑Pb stress, however, the remediation advantage of ryegrass becomes less predictable. Notably, field experiments demonstrated that the Cd BCF and Pb translocation factor (TF) of ryegrass did not change significantly when both metals were present, indicating that metal‑metal interactions in the rhizosphere modify speciation and limit simultaneous uptake9. Intercropping‑induced shifts in microbial community composition were observed, but their exact contribution to the joint Cd‑Pb dynamics remains unresolved10. Consequently, although ryegrass‑based intercropping clearly benefits single‑metal remediation, the specific mechanism for the simultaneous remediation of Cd and Pb by ryegrass is still unclear at present.

Addressing this knowledge gap, the present study will systematically evaluate the collaborative remediation performance of a corn‑ryegrass intercropping system on Cd‑ and Pb‑contaminated farmland. The research will focus on (i) the dynamic evolution of soil fertility indicators such as organic matter and readily available nutrients; (ii) the restructuring of rhizosphere microbial communities and their regulation of carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus cycling enzyme activities; and (iii) the coupling between metal‑speciation transformations and plant detoxification pathways. By integrating microbial facilitation, enzyme‑activity monitoring, and comprehensive soil‑fertility assessment, the work aims to provide a scientific basis and technical support for achieving simultaneous grain production and soil remediation.

Materials and methods

Experimental site and devices

The experiment was conducted at the Qinling Field Monitoring Center of Shaanxi Institute of Land Engineering Technology (107°52′E, 34°08′N) in Meixian County, Shaanxi Province. The region has a warm temperate semi-humid continental monsoon climate, with an annual average temperature of 12.8 °C, annual precipitation of 581.6 mm, sunshine duration of approximately 2015 h, and a frost-free period of 218 days—conditions favorable for the growth of maize and ryegrass, ensuring the reliability of phytoremediation trials.

Test soil was collected from local farmland, representing typical agricultural soils co-contaminated with Cd and Pb in the region. The soil was air-dried and sieved through a 2-mm mesh to standardize the material, improving the consistency and reproducibility of experimental results. Each cubic pot measured 40 × 40 × 40 cm and was filled with 55 kg of soil, achieving a bulk density of 1.15 g/cm³. This pot size and soil volume were carefully chosen to accommodate the root growth and nutrient uptake needs of both maize and ryegrass, allowing roots ample space to interact while ensuring the pots remain manageable for handling and observations. The basic properties of the experi-mental soil and their determination methods were shown in Table 1.

Plant materials: Maize (Zea mays L.) was selected due to its wide cultivation in Shaanxi Province, high yield potential, and moderate tolerance to Cd and Pb. Annual ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum Lam.) was chosen as a co-remediator, as it is a documented hyperaccumulator of both Cd and Pb, with rapid growth, high biomass, and strong metal uptake capacity. The experiment included three treatments with three replicates each (Fig. 1).

CK: Monoculture of maize in natural Cd/Pb levels, serving as a control for normal growth conditions.

C1: Monoculture of maize in soil spiked with Cd and Pb (target concentrations: 1.8 mg/kg Cd and 510 mg/kg Pb, 3 times the risk screening values specified in GB 15618 − 2018) to simulate moderate co-contamination.

C2: Intercropping of maize and ryegrass in spiked soil (same Cd/Pb levels as C1) with a 1:2 row ratio (maize: ryegrass) to evaluate synergistic remediation effects.

Seeds were sown at densities of 8 maize plants per pot (20 cm × 20 cm spacing) and 20 ryegrass seeds per pot, balancing resource competition and root interaction. Cd and Pb were added as CdCl₂·2.5 H₂O and Pb (NO₃)₂ dissolved in deionized water, mixed thoroughly into the soil, and aged for 2 weeks under controlled environmental conditions (temperature 15–23 °C, humidity 15%–20%, no wet-dry cycles applied) to stabilize bioavailability. Pots were placed in a greenhouse with controlled conditions (temperature 15–23 °C, humidity 15%–20%) and watered weekly to maintain 60% field capacity.

Sampling and measurement of agronomic parameters

During the 120-day growth period, plant height, leaf number, and root/shoot biomass were measured at the tasseling and maturity stages. At harvest, maize ears were collected to determine Cd/Pb concentrations in grains. Ryegrass aboveground biomass was har-vested separately to quantify Cd and Pb uptake.

For the determination of soil properties, rhizosphere soil samples (0–20 cm depth) were collected at the pre-experimental and post-experimental stages. Soil pH, organic matter (OM), total nitrogen (TN), total phosphorus (TP), total potassium (TK), available phosphorus (AP), and available potassium (AK) were measured following the protocols detailed in Table 1.

For the quantification of heavy metals (Cd and Pb), soil and plant samples were subjected to targeted digestion protocols prior to analysis. Specifically, total Cd and Pb in soil samples were extracted using a mixed acid solution of HNO₃-HClO₄ (4:1, v/v), whereas Cd and Pb in plant tissues (roots, shoots, and grains) were extracted with an HNO₃-H₂O₂ mixture (3:1, v/v). The concentrations of Cd and Pb in all digested solutions were quantified using graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrometry (GF-AAS, Hitachi Z-2000). It is critical to note that the reported reduction in soil heavy metal concentrations represents the net decrease in the quantifiable metal pool within the soil system. This net decrease is a comprehensive outcome of multiple, potentially concurrent processes driven by the intercropping system. These processes include: (1) active phytoextraction and removal via the harvesting of ryegrass biomass; (2) in-situ immobilization, where metals are transformed into highly stable, recalcitrant forms that may exhibit resistance to complete extraction by the standard acid digestion method; and (3) potential redistribution into soil micro-aggregates or organic fractions that are analytically inaccessible. Therefore, the data represent the overall remediation efficiency of the intercropping system in reducing the environmentally relevant and analytically detectable metal fraction, rather than a complete mass balance of all metal fates. Quality control for the analytical process was ensured by incorporating certified reference materials: GBW07405 (for soil matrix) and GBW10045 (for maize tissue matrix).

Soil enzyme activities and microbial communities were analyzed to evaluate soil nutrient cycling potential and microbial functional characteristics. Four key soil enzymes were assayed following the methods described by Tabatabai (1994): catalase (determined via KMnO₄ titration), dehydrogenase (measured using the 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) reduction method), alkaline protease (assayed by folin-phenol colorimetry), and urease (quantified through indophenol blue colorimetry). For microbial community analysis, total genomic DNA was extracted from 0.5 g of fresh soil samples using the MoBio PowerSoil Kit (MoBio Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The V3-V4 hypervariable region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified using the primer pair 338 F (5’-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCA-3’) and 806R (5’-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3’), followed by high-throughput sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Sequence data were processed using QIIME 2 (Version 2022.11): alpha diversity indices (Chao1 for richness and Shannon for evenness) were calculated to characterize microbial community diversity, and community composition was analyzed at both the phylum and genus taxonomic levels.

Data analysis

Experimental data processing was performed using SPSS 18.0 software, through which all experimental data were collated, calculated, and preliminarily analyzed. Sig-nificance tests were conducted using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the least significant range (LSR) method to determine the significance of differences between data from different treatment groups.

The bioconcentration factor (BCF) reflects the ability of crops to accumulate heavy metals from the soil. This study focused on analyzing the BCF of maize grains and ryegrass for Cd and Pb (BCF_grain), calculated using the formula:

BCF (M) = C_grain/ryegrass (M)/Cₛ(M) (1).

Where M represents the type of heavy metal (M = Cd/Pb); C_grain/ryegrass (M) is the content of the corresponding heavy metal (Cd/Pb) in maize grains (mg/kg) or ryegrass; and Cₛ(M) is the content of the corresponding heavy metal (Cd/Pb) in the soil (mg/kg).

Microbial diversity indices and community structure were analyzed in QIIME2. Ca-nonical correspondence analysis (CCA) in R (vegan package) explored relationships be-tween soil properties, enzyme activities, and microbial communities. Graphs were gener-ated using Origin 2023 and R ggplot2.

Results and discussion

Remediation efficiency of ryegrass-maize intercropping on Cd-Pb co-contaminated farmland soil

In this study, the Cd and Pb content in soil before and after the experiment in different treatment groups was precisely determined, and the results showed significant differences (Fig. 2). Before the experiment, the average soil Cd content was 1.74 mg/kg, and the average Pb content was 508.30 mg/kg, providing a consistent baseline for pollution remediation research. The untreated natural soil (CK group) served as a reference for the “clean cultivation system” in terms of heavy metal content and corn grain quality.

After a 120-day growth period, the single-cultivation group (C1) showed a limited reduction in soil Cd and Pb content, with decreases of 52.87% and 61.61%, respectively. This result is attributed to the fact that while corn has a tolerance to heavy metals, its enrichment capacity is weak (e.g., the plant enrichment coefficient for Cd is only 0.15), primarily through minor root absorption and physiological processes that reduce the mobility of heavy metals in the surface soil. In the intercropping system of ryegrass and maize (C2), the remediation effect was significantly better than in the monoculture system. The average reduction in soil Cd content was 91.95% (residual concentration reduced to 0.14 mg/kg), and the reduction in Pb content was 96.07% (residual concentration 19.95 mg/kg), both below the risk screening values for agricultural soil pollution (GB 15618 − 2018) (Cd 0.6 mg/kg; Pb 170.0 mg/kg). The observed reductions likely represent a combination of active removal and in-situ immobilization, amplified by the controlled experimental conditions. Therefore, the data represent the overall remediation efficiency of the intercropping system in reducing the environmentally relevant and analytically detectable metal fraction, rather than a complete mass balance of all metal fates.

In addition, the absence of a ryegrass monoculture under Cd‑Pb co‑contamination is a limitation of the present design. Previous studies have shown that ryegrass alone can only achieve moderate removal efficiencies (≈ 45–58% for Cd and ≈ 52–61% for Pb) under similar contamination levels11,12. Therefore, the markedly higher reductions observed in our intercropping system (Cd 91.95%, Pb 96.07%) are likely attributable to synergistic interactions between ryegrass and maize, such as complementary root architectures and altered rhizosphere chemistry. Future work will incorporate a ryegrass‑only treatment under identical Cd‑Pb stress to quantitatively separate the contribution of ryegrass from the intercropping effect.

Under Cd and Pb co-contamination, the plant enrichment and migration behavior of heavy metals varied significantly across different planting systems. In C1, the grain Cd content reached 0.13 mg/kg, exceeding the limit of GB 2762 − 2022 by 30%. In C2, the grain Cd content was significantly reduced to 0.01 mg/kg (a 92.3% reduction), and the Pb content was 1.26 mg/kg, with the BCF-Cd reduced to 0.08. These results indicate that the intercropping system’s heavy metal resistance mechanism inhibits the migration of heavy metals to the grain, with rye acting as a “heavy metal sink” that efficiently enriches Cd (BCF-Cd 1.13) and Pb (BCF-Pb 0.16), reducing the effective soil content. The intercropping system significantly enhances the safe utilization of contaminated soil13. The differences in effect highlight the remediation potential of species pairing— the physiological complementarity between rye and corn enhances the extraction efficiency of Cd/Pb by 2.1 times (Cd) and 1.6 times (Pb) compared to monoculture, while simultaneously reducing the risk of crop contamination by 65%.

Variation of Cd and Pb content in soil and maize in different experimental groups Note: Asterisks indicate significant differences: *(P < 0.05), **(P < 0.01), ***(P < 0.001). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, (n = 3). In (a), green bars represent Cd contents of soil, green squares with lines represent Cd contents of Zea mays L.; in (b), blue bars represent Pb contents of soil, light blue squares with lines represent Pb contents of Zea mays L. Red dashed lines in both charts represent background values.

Effects of changes in soil properties and fertility in ryegrass-maize intercropping

The soil properties changed before and after the experiments in different treatment groups, with significant differences (Table 2). Soil organic matter (SOM) changes indicated that the C2 group had the highest average SOM increase (5.89%), followed by the C1 group (4.51%) and the CK group (3.42%). In the C2 and C1 systems, plant residue returns and root secretion input promoted organic matter accumulation. As Zhou et al. (2025) studied, intercropping systems with different plant root exudates complement each other, stimulating microbial activity, accelerating organic matter synthesis and stabilization; monoculture corn roots can also supplement organic matter through litter, but intercropping with higher diversity of intercrops shows more significant effects14.

Total nitrogen (TN) and phosphorus-potassium nutrient differences showed that the C1 group TN decreased (12.79%) because corn monoculture requires large nitrogen input, which exceeds supplementation. The CK and C2 groups had stable TN, possibly due to nitrogen balance maintained by interspecific interactions between ryegrass and maize in intercropping, such as nitrogen input from ryegrass litter decomposition and regulation of microbial nitrogen transformation processes by root exudates15. Similar to Luo et al. (2024), who found that legume-grass intercropping maintains nitrogen balance through inter-specific interactions, although there is no legume in this study, the intercropping of blackgrass and corn may still optimize nitrogen use16. Meanwhile, the C2 group TP slightly increased (1.35%) and TK decreased (3.33%), while the C1 group TP decreased (1.35%) and TK increased (5.73%). This is related to crop absorption characteristics and root secretion effects on phosphorus-potassium transformation: C1 may promote potassium release (TK increase) and consume phosphorus (TP decrease); C2 has more complex phosphorus-potassium regulation due to root secretion interactions, as Nayeri et al. (2023) indicated that intercropping can alter root pH and enzyme activity, affecting nutrient availability17.

pH and available nutrients (AP, AK) results showed that the C2 group pH decreased (8.54%), while the C1 group slightly decreased (0.47%), possibly due to intercropping root exudates (e.g., alkaline substances from blackgrass) and microbial metabolism. Lu et al. (2025) showed that plant root exudates can regulate rhizosphere pH, and intercropping systems with species interactions more easily alter acid-base environments18. The C1 group AP significantly increased (44.11%) and AK increased (11.88%) because monoculture corn roots may secrete organic acids to dissolve insoluble phosphorus and promote potassium release; CK and C2 groups AP decreased—for the C2 group (ryegrass-maize intercropping), this available phosphorus depletion is not merely due to crop absorption and phosphorus fixation, but maybe driven by this two interconnected key factors: first, synergistic phosphorus uptake by ryegrass and maize—ryegrass requires high phosphorus inputs to support rapid biomass accumulation and synthesize phosphorus-containing root exudates (e.g., citric acid) for heavy metal chelation, while maize demands phosphorus for kernel development, leading to intensified interspecific competition for available phosphorus19; second, microbial regulation of phosphorus cycling—intercropping enriches phosphorus-mineralizing microorganisms (e.g., Actinobacteriota, as shown in Fig. 5) that decompose organic phosphorus into inorganic forms, but these mineralized nutrients are preferentially utilized by ryegrass and maize, further accelerating available phosphorus depletion20. In contrast, the CK group’s AP decrease is mainly attributed to maize’s single-crop absorption and soil phosphorus fixation. Additionally, the C2 group AK decrease (8.91%) was less than CK (10.39%), indicating intercropping’s advantage in potassium retention, similar to Long et al. (2021) who found intercropping reduces potassium leaching and maintains available potassium levels21.

Overall, different planting patterns affect soil properties and fertility through changes in plant-soil-microbe interactions. C2 performs better in organic matter accumulation, nitrogen stability, and some nutrient regulation, while C1 has specific improvements in phosphorus-potassium availability. These differences can provide insights for optimizing planting patterns and co-regulating fertility in soil remediation.

Effects of changes in soil ecosystem in ryegrass-maize intercropping

Changes in soil enzyme activities in different treatment groups

The changes in root soil enzyme activities in different treatment groups can effectively reveal the trend of changes in the soil ecosystem before and after the experiment (Fig. 3). After the experiment, the activity of catalase, a key redox-regulating enzyme in the soil, increased by approximately 277.9%, 269.6%, and 261.0% compared to before the experiment in the CK, C1, and C2 groups, respectively. The planting activity disrupted the idle state of the soil, and the root exudates (such as sugars and organic acids) from maize or ryegrass-maize systems provided carbon sources for microorganisms, driving the proliferation of bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms, thereby increasing the demand for H2O2 decomposition and activating catalase activity22. The C2 group, due to the complex root system of rye and corn, had a higher microbial diversity, and inter-species resource competition somewhat reduced the enzyme activity increase; however, compared to the low metabolic state before the experiment with no plant intervention, all three groups achieved significant enzyme activity increases due to planting inputs, clearly demonstrating the activation effect of plant-microbe interactions on soil redox metabolism function. The CK and C1 groups, due to their single species, had microbial communities more directly influenced by root exudates.

After the experiment, the activity of proteases, which are responsible for organic nitrogen decomposition, increased by approximately 9.6 times, 16.0 times, and 18.5 times in the CK, C1, and C2 groups, respectively. Before planting, the soil had insufficient organic nitrogen mineralization, and protease activity was low. After planting, the nitrogen demand of ryegrass-maize stimulated microorganisms to secrete large amounts of proteases to accelerate the decomposition of proteinaceous materials to supplement the available nitrogen pool23. The C2 group, due to the synergistic effect of root exudates from ryegrass-maize, had higher total and more complex exudate components, which more effectively induced protease-producing microorganisms, leading to a higher increase in protease activity. The C1 group, although affected by pollution stress, still had significant enzyme activity increases due to the nitrogen demand of corn growth, but the induction effect was weaker due to the single root exudate. The CK group had a relatively lower enzyme activity increase, reflecting the influence of the soil’s inherent nitrogen cycle state and the synergistic effect of planting patterns on protease function expression.

After the experiment, the activity of dehydrogenase, which reflects the intensity of microbial energy metabolism, decreased by approximately 82.6%, 71.2%, and 67.6% in the CK, C1, and C2 groups, respectively. Before planting, the soil was idle, and microorganisms primarily utilized recalcitrant substrates such as humus for anaerobic or aerobic respiration. After planting, the root system occupied soil pores, reducing the oxygen content in the rhizosphere, and root exudates provided easily degradable carbon sources, which were preferentially utilized by microorganisms, reducing the decomposition of complex humic substrates24. The C2 group, due to the more uniform distribution of ryegrass and maize roots, had a less disturbed rhizosphere microenvironment, resulting in a smaller decrease in dehydrogenase activity. The CK and C1 groups, with concentrated root systems, had more significant enzyme activity decreases due to greater disturbance of the microenvironment.

After the experiment, the activity of urease increased by approximately 740.8%, 592.3%, and 709.9% in the CK, C1, and C2 groups, respectively. Before planting, the soil had insufficient urea substrate input, and urease activity was low. After planting, the nitrogen demand of ryegrass and maize stimulated microorganisms to secrete urease to decompose urea in the soil to supplement available nitrogen25. The C1 group, affected by pollution stress, had a weak induction effect on urease-producing microorganisms due to the single root exudate, resulting in the lowest enzyme activity increase. The C2 group, due to the diverse root exudates of rye and corn, more effectively activated urease-producing microorganisms, leading to a significant increase in enzyme activity. The CK group, although without crop competition, had lower nitrogen utilization efficiency due to the lack of strong nitrogen demand driving plant absorption. The differences among the three groups highlight the role of planting patterns in the synergistic regulation of nitrogen turnover, providing insights for optimizing nitrogen use and selecting appropriate planting patterns in polluted soil fertility management.

Changes in microbial diversity and community structure

Analysis of microbial diversity

In microbial community diversity analysis, Chao1 reflects species richness and Shannon reflects the combined level of richness and evenness. Before planting, the Chao1 value of the CK group (3532.62) in the non-polluted soil maize monoculture was higher than that of the C1 group (3142.17) in the polluted soil maize monoculture and the C2 group (3123.76) in the intercropping system of rye and maize. The Shannon indice also showed a trend of CK > C1 > C2, indicating that pollution reduced the evenness of the microbial community. The intercropping system initially had weak synergistic effects from secretions, making it more sensitive to pollution responses.

After planting, the Chao1 value of the CK group decreased from 3532.62 to 2668.52 (a decrease of 24.5%), due to the homogenization of root exudates compressing the microbial habitat space. The C1 group experienced a 33.0% decrease in Chao1, due to the combined stress of pollution and monoculture leading to a sharp decline in richness. The C2 group decreased by 27.5%, with intercropping secretions complementing each other to alleviate pollution, resulting in a smaller decrease in richness compared to C1. Changes in Shannon indices showed that the C1 group had the most significant decline in diversity and evenness due to the expansion of tolerant microorganisms. The C2 group, by leveraging secretion regulation, weakened the selective pressure of pollution, maintaining community stability, demonstrating the potential of intercropping in microbial remediation of polluted soils.

Evolution of microbial community structure

Phylum level

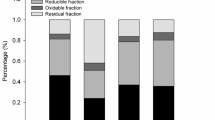

In the context of Cd and Pb co-contamination, the microbial community at the phylum level exhibits significant inter-group differences due to the interaction of dual stress and planting patterns (Fig. 5(a)). For Proteobacteria, the relative abundance in the CK group (non-contaminated soil, maize monoculture) was 32.97% before the experiment. In the C1 group (contaminated soil, maize monoculture) and C2 group (intercropping of ryegrass and maize), the abundance increased to 42.38% and 39.31%, respectively, due to the stimulation of Cd-Pb co-contamination. This is consistent with the findings of Zhu et al. (2025), which indicated that heavy metal co-contamination selects for resistant microorganisms26. Some strains within the Proteobacteria phylum possess heavy metal resistance genes (e.g., metal transporter encoding genes) that allow them to survive in contaminated environments through active efflux, chelation of heavy metals, and thus proliferate under co-contamination stress, becoming dominant groups.

The changes in Actinobacteriota reflect the temporal dynamics and tolerance advantages of contamination. Before the experiment, the abundance in the CK group was 21.51%. In the C1 and C2 groups, the immediate stress of Cd-Pb co-contamination inhibited the growth of sensitive actinobacteria, reducing their abundance to 16.10% and 14.51%, respectively. After the experiment, long-term co-contamination continued to suppress sensitive strains, while the Actinobacteria phylum, with its robust cell wall, secondary metabolites (e.g., antibiotics, chelators), and strong tolerance features (Zhu et al., 2025 indicated that actinobacteria can secrete organic acids to chelate heavy metals, reducing bioavailability26, significantly increased in abundance in the CK, C1, and C2 groups (reaching 47.16%, 36.17%, and 43.99%, respectively), becoming dominant groups in the later stages of co-contamination. It is plausible that these processes led to the formation of highly stable metal-organic complexes or micro-precipitates. These newly formed, recalcitrant phases might have adsorbed onto fine organic debris or been sequestered within stable micro-aggregates, rendering them partially resistant to complete extraction during sample preparation. The Actinobacteria abundance in the C2 group was higher than in the C1 group, likely due to the introduction of ryegrass, which, through root exudates (e.g., polysaccharides, phenolic compounds), regulates the rhizosphere micro-environment pH and redox potential, further promoting actinobacteria growth and enhancing their adaptability in co-contaminated soil.

For Chloroflexi and Gemmatimonadota, the co-contamination shows differential effects. The abundance of Chloroflexi increased to 15.18% in the C1 group after the experiment, as some Chloroflexi strains possess photosynthetic heterotrophy, the ability to metabolize recalcitrant organic matter, and can utilize root exudates from maize, and have some tolerance to Cd-Pb co-contamination (Wang et al., 2025 mentioned that under heavy metal stress, Chloroflexi adjust their metabolism to adapt to the environment27. Gemmatimonadota abundance decreased after the experiment, likely due to exceeding their tolerance threshold, leading to growth inhibition. In the C2 group, the more complex microbial interactions in the intercropping system, with synergistic effects from root exudates of ryegrass and maize, further influenced the abundance of these phyla, reflecting the fine-tuning of microbial community dynamics under co-contamination.

Genus level

In the Cd Pb composite polluted environment, the horizontal microbial community is driven by both pollution stress and planting patterns, showing significant inter group differences (Fig. 5 (b)). Under pollution stress, there is a significant differentiation between sensitive and tolerant genera: Sphingomonas is sensitive to heavy metals, and long-term Cd Pb composite pollution inhibits its proliferation by damaging cell membranes, interfering with metabolic pathways28. After the experiment, the abundance of CK, C1, and C2 groups decreased, Lysobacter is tolerant, and the abundance of C2 group was significantly higher than that of CK and C1 groups before the experiment. Due to the stimulation of compound pollution, its growth was optimized by the root exudates of ryegrass maize under intercropping mode, further promoting its proliferation and reflecting the mechanism of “intercropping driven enrichment of tolerant bacteria“29.

The response of special functional genera in composite pollution is unique. Arenimonas was significantly enriched in the C2 group before the experiment due to its Cd tolerance, and the rhizosphere ecological niche created by intercropping allowed it to continue to proliferate after the experiment; Streptomyces possess both pollution resistant survival and uncontaminated reproduction characteristics. After composite pollution, the C2 group optimizes the microbial interaction network to provide resources, significantly increasing their abundance and becoming a key functional genus for remediation.

The ryegrass-corn intercropping system precisely regulates rhizosphere microbial communities at the genus level through synergistic effects. This management enriches Cd-tolerant genera (e.g., Lysobacter, Arenimonas), whose secretions chelate heavy metals and produce functional metabolites. Simultaneously, sensitive taxa (e.g., Sphingomonas) attenuate under pollution stress, reducing ecological pressure. The system further stimulates proliferation of multifunctional genera like Streptomyces, which actively participate in remediation processes. This genus-specific differentiation in microbial responses provides targeted resources for bioremediation [30]. Subsequent metatranscriptomic analysis of functional metabolic pathways should elucidate the coupling mechanisms between complex soil pollution, planting regimes, and microbial functions.

Mechanisms for remediation of Cd-Pb co-contaminated by ryegrass-maize intercropping

The mechanism by which ryegrass contributes to soil Cd and Pb remediation in the corn-ryegrass intercropping system is driven by three core synergistic pathways, underpinning the system’s “remediation-production” integration and corn safety guarantee (Fig. 6).

This interpretation is supported by several lines of evidence pointing to a multi-pathway remediation mechanism. Firstly, the high bioconcentration factor for Cd (BCF-Cd 1.13) observed in ryegrass confirms its role as a primary “metal sink” through active phytoextraction. Secondly, the significant enrichment of functional microbial taxa, such as Actinobacteriota (relative abundance reached 43.99% in the C2 group) and Lysobacter, suggests a strong biologically-driven immobilization pathway. These microbes are known to secrete extracellular polymers and organic acids that can chelate heavy metals, forming stable complexes that are less bioavailable and potentially more resistant to chemical extraction. Finally, the substantial increase in soil organic matter (5.89%) in the C2 group provides additional sorption sites, further contributing to the immobilization and potential analytical inaccessibility of the residual metals. This multifaceted process—combining extraction, immobilization, and sequestration—explains the dramatic net reduction observed and underscores the system’s capacity to not only remove but also stabilize residual contamination. The integrated synergy of active extraction, microenvironment modulation, and micro-ecosystem enhancement not only enables high remediation efficiency but also reconstructs the soil’s ecological functions, thereby enhancing its ecosystem services.

Conclusions

Ryegrass-maize intercropping demonstrated a remarkable capacity to remediate Cd-Pb co-contaminated soil, achieving reduction efficiencies of 91.95% for Cd and 96.07% for Pb, which brought final concentrations below national risk screening thresholds. This system ensured crop safety, as ryegrass acted as an effective bioaccumulator while significantly inhibiting the transfer of heavy metals to maize grains. Beyond mere decontamination, the intercropping system actively restored soil health. It enhanced key ecosystem services by boosting soil enzymatic activities linked to redox regulation and nitrogen cycling, and fostered habitat sustainability by enriching functional, metal-tolerant microbial taxa like Actinobacteriota and Lysobacter. It is crucial to interpret these high reduction rates with caution; they likely reflect a combination of active phytoextraction and in-situ immobilization processes amplified within the controlled pot experiment environment. Therefore, these figures should be viewed as an indicator of the system’s maximum potential under idealized conditions rather than a guaranteed outcome for field applications. Future research must incorporate mass balance calculations and speciation analysis to deconvolute the relative contributions of removal versus immobilization and to validate these promising findings in real-world agricultural settings. While observed nutrient competition, particularly phosphorus depletion, necessitates optimized management strategies, the collective evidence positions ryegrass-maize intercropping as a balanced approach that effectively couples pollution control with agricultural productivity. To enhance the scalability of this green remediation technology, future work should prioritize genotype screening and environmental adaptability assessments for diverse cropland systems.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available in the [NSBI] repository [https://submit.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/subs/sra/SUB15666464/overview].

References

Pandian, K. et al. Synergistic conservation approaches for nurturing soil, food security and human health towards sustainable development goals. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 16, 100479 (2024).

Ministry of Environmental Protection. Ministry of Land and Resources. National Soil Contamination Survey Bulletin [EB/OL]. -04-17). (2014).

Huang, C. Y., Bazzaz, F. A. & Vanderhoef, L. N. The Inhibition of soybean metabolism by cadmium and lead. Plant. Physiol. 54, 122–124 (1974).

Wang, M., Zou, J., Duan, X., Jiang, W. & Liu, D. Cadmium accumulation and its effects on metal uptake in maize (Zea Mays L). Bioresource Technol. 98, 82–88 (2007).

Gong, B. et al. Interactions of arsenic, copper, and zinc in soil-plant system: Partition, uptake and phytotoxicity. Sci. Total Environ. 745, 140926 (2020).

Ali, I., Hussain, J., Yanwisetpakdee, B., Iqbal, I. & Chen, X. The effects of monoculture and intercropping on photosynthesis performance correlated with growth of Garlic and perennial ryegrass response to different heavy metals. BMC Plant. Biol. 24, 659 (2024).

Wuana, R. A. & Okieimen, F. E. Heavy Metals in Contaminated Soils: A Review of Sources, Chemistry, Risks and Best Available Strategies for Remediation. ISRN Ecology 102467 (2011). (2011).

Huang, J., Li, J., Lin, L., Jiang, W. & Liao, M. Effects of intercropping with Bidens species on nutrient absorption of grape seedlings under cadmium stress. Adv. Eng. Res. 143, 1002–1005 (2017).

Pu, C. et al. Intercropping grapevine with Solanum nigrum enhances their cadmium tolerance through changing rhizosphere soil microbial diversity. Front. Microbiol. 16 (1), 1537123 (2025).

Woźniak, A. & Kawecka-Radomska, M. Crop management effect on chemical and biological properties of soil. Int. J. Plant. Prod. 10, 391–402 (2016).

Shi, G. et al. Modification-bioremediation of copper, lead, and cadmium-contaminated soil by combined ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum Lam.) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa treatment. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 27, 37668–37676 (2020).

Zhang, J. et al. Effects of the combined pollution of cadmium, lead and zinc on the phytoextraction efficiency of ryegrass (Lolium Perenne L). RSC Adv. 9, 20603–20611 (2019).

Meng, D. et al. Clean production of cadmium contaminated paddy soil: comprehensive effects of rice intercropping and soil amendments. Field Crops Res. 331, 110009 (2025).

Zhou, D. et al. Microbial mechanisms underlying complementary soil nutrient utilization regulated by maize-peanut root exudate interactions. Rhizosphere 33, 101051 (2025).

Liedgens, M., Frossard, E. & Richner, W. Interactions of maize and Italian ryegrass in a living mulch system: (2) nitrogen and water dynamics. Plant. Soil. 259, 243–258 (2004).

Luo, C. et al. Complementarity and competitive trade-offs enhance forage productivity, nutritive balance, land and water use, and economics in legume-grass intercropping. Field Crops Res. 319, 109642 (2024).

Nayeri, S. et al. CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated genetically edited ornamental and aromatic plants: A promising technology in phytoremediation of heavy metals. J. Clean. Prod. 428, 139512 (2023).

Lu, X. et al. Combined remediation effect of ryegrass-earthworm on heavy metal composite contaminated soil. J. Hazard. Mater. 494, 138477 (2025).

Li, L. et al. Diversity enhances agricultural productivity via rhizosphere phosphorus facilitation on phosphorus-deficient soils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 104, 11192–11196 (2007).

Long, G. et al. Nitrogen levels regulate intercropping-related mitigation of potential nitrate leaching. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 319, 107540 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Comprehensive analysis of degradation and accumulation of ametryn in soils and in wheat, maize, ryegrass and alfalfa plants. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 140, 264–270 (2017).

Zhao, X. et al. Biochar enhanced polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons degradation in soil planted with ryegrass: bacterial community and degradation gene expression mechanisms. Sci. Total Environ. 838, 156076 (2022).

Huo, C., Luo, Y. & Cheng, W. Rhizosphere priming effect: A meta-analysis. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 111, 78–84 (2017).

Li, Y. et al. The effects of localized Plant-Soil-Microbe interactions on soil nitrogen cycle in maize rhizosphere soil under Long-Term fertilizers. Agronomy 13 (8), 1314 (2023).

Zhu, S. et al. Resilience mechanisms of rhizosphere microorganisms in lead-zinc tailings: metagenomic insights into heavy metal resistance. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 292, 117956 (2025).

Wang, H. et al. The hidden diversity and functional potential of Chloroflexota genomes in arsenic and antimony co-contaminated soils. Soil. Ecol. Lett. 7, 1 (2025).

Ceylan, Ö. & Uğur, A. Bio-Monitoring of heavy metal resistance in Pseudomonas and Pseudomonas related genus. J. Biol. Environ. Sci. 6, 233–242 (2012).

Ma, H. et al. Synthetic microbial community isolated from intercropping system enhances P uptake in rice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25 (22), 12819 (2024).

Leys, N. M. E. J. et al. Occurrence and phylogenetic diversity of Sphingomonas strains in soils contaminated with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70 (4), 1944–1955 (2004).

Funding

This work was financially founded by the Key Laboratory of Degraded and Unused Land Consolidation Engineering, the Ministry of Natural Resources (SXDJ2024-23), the Technology Innovation Center for Land Engineering and Human Settlements, Shaanxi Land Engineering Construction Group Co.,Ltd and Xi’an Jiaotong University (2024WHZ0229), and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2023M742865).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shenglan Ye: Validation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing - original draft. Yan Niu: Writing - review & editing, Formal analysis. Bei Zhang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - original draft, Funding acquisition, Writing - review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ye, S., Niu, Y. & Zhang, B. Integrating ryegrass-maize intercropping systems for mitigating Cd-Pb contamination: enhancing ecosystem services and habitat sustainability. Sci Rep 15, 45255 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29416-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29416-1