Abstract

Lower serum parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels are reported to improve mortality and fracture incidence in patients using calcimimetics. We investigated the prognosis of calcimimetic users and non-users with similar PTH levels within the target range. This retrospective study compared 2-year all-cause mortality and the incidence of any fracture in dialysis patients between calcimimetic users (n = 131) and non-users (n = 294) with PTH levels between 60 and 240 pg/mL using a propensity score-matched model. Kaplan–Meier survival curves censored by PTH level, calcimimetic use, and other factors were compared; then, adjusted Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was performed. After matching, mortality was significantly lower in calcimimetic users than in non-users (n = 130; hazard ratio [HR] 0.243, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.073–0.801, P = 0.022, log-rank test). The PTH levels of users and non-users were 142.4 ± 49.4 and 132.7 ± 48.0 pg/mL, respectively (P = 0.127). Cox regression analysis demonstrated that mortality was significantly lower in users than in non-users (adjusted HR 0.260, 95% CI 0.071–0.947, P = 0.041). Calcimimetic use had no effect on fracture incidence. These findings suggest that, among dialysis patients with PTH levels between 60 and 240 pg/mL, mortality risk was significantly lower among calcimimetic users than in non-users. However, fracture risk was not significantly different between these groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 2012, the Japanese Society for Dialysis Therapy (JSDT) has published clinical practice guidelines for the management of chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder. Based on the JSDT Renal Data Registry (JRDR) database before calcimimetics were available, the biochemical targets for patients on hemodialysis (HD) and online hemodiafiltration (OHDF) were 3.5–6.0 mg/dL for serum phosphate (P), 8.4–10.0 mg/dL for corrected calcium (Ca), and 60–240 pg/mL for intact parathyroid hormone (PTH)1.

A recent report using the JRDR 2009–2018 database2 indicated that among 22,853 cinacalcet users, there was no increase in mortality, even with PTH levels < 60 pg/mL. The study was based on time-dependent and time-averaged models. This suggests that the lower limit of PTH targets can be reduced when calcimimetics are used. It has therefore been suggested that the that increased mortality associated with PTH levels < 60 pg/mL prior to the availability of calcimimetics3 was due to hypercalcemia and vascular calcification from the use of active vitamin D analogues and calcium carbonate.

Although the effect of cinacalcet on fractures was not significantly different from that of a placebo in an unadjusted intention-to-treat analysis, a significant reduction in fractures was observed in a prespecified lag-censoring analysis with adjustment for baseline characteristics and multiple fractures4. The administration of etelcalcetide was associated with improvements in central skeleton areal bone mineral density and trabecular quality, as well as reduced bone turnover5. A meta-analysis of randomized trials in HD patients with secondary hyperparathyroidism (SHPT) demonstrated that calcimimetics reduced the fracture incidence relative to placebo6. In a study based on the JRDR 2016–2017 database, higher PTH levels were associated with an increased risk of fractures requiring hospitalization, while lower PTH levels were associated with a decreased fracture incidence in high-risk patients, including elderly individuals, women, and patients with lower body mass index (BMI) values7.

As mentioned above, lower PTH levels improved mortality and reduced the fracture incidence in dialysis patients using calcimimetics. However, the PTH levels of non-users were higher than those of users. Because there have been no reports examining whether continuing or discontinuing calcimimetics would improve the prognosis of patients with similar PTH levels, we investigated the effects on all-cause mortality and the incidence of any fracture between calcimimetic users and non-users within the target PTH range.

Methods

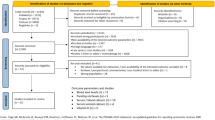

Patient selection

A total of 944 patients on maintenance dialysis at our corporate facilities as of July 1, 2017, were registered in our records database as described in a previous report8. Our corporation has seven facilities in Tokushima Prefecture, Japan. The patient selection process is shown in Fig. 1. The exclusion criteria were age < 20 years, blood purification methods other than HD or OHDF, dialysis frequency of < 3 sessions per week, dialysis time < 3 h, substitution volumes for predilution OHDF < 60 L and postdilution OHDF < 8 L, missing values of covariates, pregnancy or lactation, PTH levels < 60 pg/mL and > 240 pg/mL, dialyzers with in vitro β2-microglobulin (β2MG) clearance < 70 mL/min or a type S dialyzer, and a change in dialysis conditions (dialysis method, dilution method, substitution volume, or membrane material) from April 1, 2017 to July 1, 2017. A total of 425 patients on HD and OHDF with PTH levels between 60 pg/mL and 240 pg/mL were recruited to prepare a propensity score-matched model (calcimimetic users, n = 131; cinacalcet, n = 127; etelcalcetide, n = 4; and calcimimetic non-users n = 294).

We confirmed the use of calcimimetics, PTH levels, dialysis method, and albumin leakage annually. In the Kaplan–Meier survival analysis, we censored instances of switching between the use and non-use of calcimimetics, switching dialysis method (HD, predilution OHDF, or postdilution OHDF), albumin leakage changing between < 3 g/session and ≥ 3 g/session, and PTH levels changing to < 60 pg/mL or > 240 pg/mL. As a result, only patients in stable condition during the first year who did not have censoring events were eligible for further follow-up. The dialysis method was selected by the patient’s physician, and blood test results were extracted from the patients’ medical records.

Outcomes

The primary endpoint was 2-year all-cause mortality and the secondary endpoint was incidence of any fractures during the 2-year study period.

Preparation of propensity score-matched pairs

Propensity scores were matched for 130 pairs of patients. The following 18 items were used to calculate the propensity scores for comparing patient outcomes: age, sex, dialysis vintage, presence or absence of diabetes mellitus (DM), presence or absence of cardiovascular disease (including angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, stroke, peripheral artery disease, and limb amputation), administration of active vitamin D analogues (oral and intravenous), administration of P binders, Kt/V, β2MG, albumin leakage, BMI, normalized protein catabolism rate, albumin, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, systolic blood pressure, hemoglobin, Ca, and P, which were all measured in the same laboratory. The duration of each dialysis session was 4 h, the blood flow rate was 250–350 mL/min, and the membrane surface area was 2.1–2.5 m2 in HD and 2.0–3.0 m2 in OHDF. Both the dialysate flow rate (QD) in HD and total QD (QD plus the substitution volume) in OHDF were fixed at 500 mL/min.

To calculate the propensity score for each patient, multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed using the two patient groups (calcimimetic user and non-users) as the dependent variable and 18 covariates as independent variables, followed by logit transformation. The propensity scores were calculated to 14 decimal places. Regardless of the number of cases, patients in the two groups were paired by nearest available matching at a 1:1 ratio, within a caliper of 0.316688 (0.2 times the standard deviation of the logit value) for all patients in both groups9.

Statistical analysis

Survival was determined from the medical records, which included information on death and transfer to other hospitals. A daily survival analysis was performed for the two groups, including deaths and transfers, using the Kaplan–Meier method. The statistical significance of differences between the two groups was assessed using the log-rank test. Cox regression analysis was performed to calculate hazard ratios (HRs). Cox proportional hazards analysis was used to compare all-cause mortality between the two groups, adjusting for covariates that remained significantly different after propensity score matching.

We analyzed the distribution of fracture frequency over a 2-year period in calcimimetic users and non-users. For data handling and analysis, fractures were treated in the same way as in the mortality analysis, with censoring applied as appropriate. Thus, the analysis was restricted to periods of exposure or non-exposure, thereby minimizing the misclassification of patients outside the period consistent with their true treatment status. The distribution of fracture frequency over 2 years between the two groups was compared using the Mann-Whitney U test.

All analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics for Windows (ver. 26, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Two-tailed P-values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethics

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Kawashima Hospital (1289–1295) on October 1, 2024, and registered in the UMIN Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN000055838 registered 15 October, 2024 - prospectively registered, https://center6.umin.ac.jp/cgi-bin/ctr_e/ctr_view.cgi?recptno=R000063817). All clinical investigations were conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. The need to obtain informed consent was waived by Research Ethics Committee of Kawashima hospital. The research information was disclosed to patients based on Ethical Guidelines for Life Science and Medical Research Involving Human Subjects before enrollment.

Results

The average observation period was 513.9 ± 247.2 months for calcimimetic users and 462.7 ± 232.8 months for calcimimetic non-users (P = 0.077). In calcimimetic users and non-users, the numbers of deaths, transfers to other hospitals, and censored cases were 3 and 11, 3 and 2, and 87 (some patients counted more than once: changed to non-users, n = 14; outside of the target PTH range, n = 37; different dialysis method, n = 28; and change of albumin leakage group, n = 23) and 89 (some patients counted more than once: changed to users, n = 12; outside of the target PTH range, n = 46; different dialysis method, n = 36; and change of albumin leakage group, n = 25), respectively. The annual mortality rates in the first and second years were respectively 2.3% and 0% for calcimimetic users and 6.2% and 2.5% for non-users.

Comparison of patient survival between calcimimetic users and non-users

Table 1 shows the comparisons of the variables recorded before and after propensity score matching. Before matching, the PTH levels in calcimimetic users and non-users were 141.8 ± 49.6 pg/mL and 131.9 ± 49.1 pg/mL, respectively (P = 0.053). After matching, the levels were 142.4 ± 49.4 pg/mL in calcimimetic users and 132.7 ± 48.0 pg/mL in non-users (P = 0.127). Additionally, the dialysis vintage was longer, the prevalence of DM was lower, and the rate of active vitamin D analogue administration was higher in users than in non-users. Two-year all-cause mortality was significantly lower in calcimimetic users than in non-users (HR 0.243, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.073–0.801, P = 0.022, log-rank test) (Fig. 2a). In Cox regression analysis, adjusted for significant covariates (age, sex, dialysis vintage, presence or absence of DM, presence or absence of cardiovascular disease, administration of active vitamin D analogues use, P binder use, Kt/V, β2MG, and albumin leakage), 2-year all-cause mortality remained significantly lower in calcimimetic users (adjusted 0.260, 95% CI 0.071–0.947, P = 0.041), as shown in Fig. 2b. The PTH levels after 2 years were 177.2 ± 115.8 pg/mL in calcimimetic users and 149.2 ± 98.1 pg/mL in non-users (P = 0.088).

Comparison of patient survival between calcimimetic users and non-users after propensity score matching. (a) Kaplan-Meier plots. (b) Adjusted variable plots by Cox proportional hazard model. HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval. Adjusted for age, sex, dialysis vintage, presence or absence of diabetes mellitus, presence or absence of cardiovascular disease, administration of active vitamin D analogues, administration of P binders, Kt/V, β2-microglobulin, and albumin leakage.

Distribution of fracture frequency and total number of fractures over 2 years in calcimimetic users and non-users

Regarding fracture history, there were no significant differences between calcimimetic users and non-users before matching (2.3% vs. 4.4%, P = 0.410) or after matching (2.3% vs. 5.4%, P = 0.334) (Table 1). Similarly, fracture incidence did not differ significantly between calcimimetic users and non-users before matching (7.6% vs. 6.8%, P = 0.749) or after matching (7.7% vs. 10.0%, P = 0.511) (Table 2). The mean (± SD) total number of fractures in calcimimetic users vs. non-users was 0.12 ± 0.50 vs. 0.10 ± 0.40/2 years (P = 0.749) before matching and 0.12 ± 0.50 vs. 0.15 ± 0.54/2 years (P = 0.511) after matching. The distribution of fracture frequency over 2 years between calcimimetic users and non-users, with and without censoring after matching, is shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Discussion

Among HD and OHDF patients, mortality was significantly lower in calcimimetic users than in non-users (HR 0.243, 95% CI 0.073–0.801, P = 0.022, log-rank test) with similar PTH levels (142.4 ± 49.4 vs. 132.7 ± 48.0 pg/mL, respectively, P = 0.127) after matching. Although some covariates remained significant, Cox regression analysis showed that mortality was significantly lower in calcimimetic users than in non-users (adjusted HR 0.260, 95% CI 0.071–0.947, P = 0.041). However, the incidence of any fracture was not significantly different between calcimimetic users and non-users whose PTH levels were within the target range.

We examined mortality and fracture incidence in HD patients using dialyzers with β2MG clearance ≥ 70 mL/min and in OHDF patients together using a propensity score-matched model that included serum albumin concentration and albumin leakage. Mortality in patients using dialyzers with β2MG clearance of ≥ 70 mL/min was significantly lower in comparison to those with β2MG clearance of < 70 mL/min10. Mortality rates did not differ significantly between patients undergoing predilution OHDF and those undergoing postdilution OHDF8. Survival of patients with albumin leakage ≥ 3.0 g/session was significantly improved in comparison with those with albumin leakage < 3.0 g/session11, while the mortality rates of patients undergoing HD and those undergoing OHDF did not differ significantly when patients had similar levels of serum albumin and albumin leakage12. Therefore, cases in which albumin leakage switched between < 3 g/session and ≥ 3 g/session were censored annually.

There has been only one report in which calcimimetic users showed improved survival. Although no significant difference was observed in the primary composite endpoint (death or the first nonfatal cardiovascular event) in the unadjusted intention-to-treat analysis, calcimimetic users showed a significantly reduced endpoint relative to the placebo group in a lag-censoring analysis, which censored data at 6 months after study-drug discontinuation13.

In the 2017 clinical practice guidelines of Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes, the target for P was the normal range, the target for Ca was the avoidance of hypercalcemia, and the target for PTH was 2–9 times the upper limit of normal14. The incidence of parathyroidectomy in Japanese patients is reported to be lower than in American patients15 likely due to the higher PTH target in the guidelines. Additionally, the prevalence of cardiovascular disease has been reported to be lower in Japanese patients than in American patients16. Furthermore, the mortality rate of Japanese HD patients is lower than that of American HD patients17. Therefore, analysis of the Japanese database is important for generating new evidence.

In Japan, calcimimetics are indicated for SHPT in dialysis patients. Since the standard reference range for PTH is 10–65 pg/mL and the guideline-recommended target PTH range in dialyzed patients is 60–240 pg/mL1, the PTH levels at which the initiation of calcimimetics is indicated vary among physicians. In general, calcimimetics are administered at PTH levels ≥ 300 pg/mL, > 240 pg/mL, or in cases of progressive PTH elevation, even when levels are ≤ 240 pg/mL, and PTH levels are maintained within the 60–240 pg/mL range.

Although mortality increased when PTH levels dropped to < 60 pg/mL in the era before calcimimetics became available3, the mortality rate of calcimimetic users did not increase in either time-dependent or time-averaged models, even when PTH levels were < 60 pg/mL2. At present, however, a problem in Japan is that no lower limit has been established for calcimimetic users whose PTH levels drop to < 60 pg/mL.

In the time-dependent and time-averaged models, the HRs (95% CIs) for cardiovascular mortality in calcimimetic users with PTH levels of 29 to < 52 pg/mL were 1.18 (0.90–1.55) and 0.8 (0.53–1.21), respectively, relative to the reference category (< 29 pg/mL); however, neither was significantly different from the reference category in either model2.

The JRDR is conducted annually, and dialysis facilities are required to record the results of tests conducted during December and medication survey results as of the end of December. The time-dependent model, which reflects short-term changes immediately before death, is highly reliable within the target PTH range, but its reliability decreases outside this range because prescriptions are promptly adjusted. In contrast, the time-averaged model is considered more reliable outside the target PTH range, reflecting cumulative survival effects over time. The HR at PTH levels of 29 to < 52 pg/mL was 0.8 relative to that at PTH levels of < 29 pg/mL.

The guidelines prioritized Ca control over PTH control1, so we have continued calcimimetics when PTH levels fell to < 60 pg/mL, even after adjusting the dosages of active vitamin D analogues and calcium carbonate, to avoid hypercalcemia when serum Ca levels remained ≥ 9.5 mg/dL. On the other hand, we have discontinued calcimimetics to prevent low turnover bone and adynamic bone when serum Ca levels were < 9.5 mg/dL or PTH levels fell below 30 pg/mL. Accordingly, we propose a lower limit of 30 pg/mL for the PTH target in calcimimetic users. Among dialyzed patients—since calcimimetic users with PTH levels between 60 and 240 pg/mL showed a decreased mortality risk relative to non-users, despite having similar PTH levels—it is suggested that the target PTH range in calcimimetic users should be between 30 and 240 pg/mL.

The mechanism underlying the decreased mortality of calcimimetic users relative to non-users with similar PTH levels is suggested to include several factors. Activation of Ca sensing receptors reduces osteogenic transformation of vascular smooth muscle cells by stimulating matrix-Gla protein and attenuating the upregulation of bone morphogenetic protein-2. Additionally, this activation reduces fibroblast growth factor-23 levels, thus reducing the risk of vascular calcification18,19.

Studies have reported that the incidence of fractures was reduced by 16–29% in calcimimetic users, based on a prespecified lag-censoring analysis with adjustments. The fracture rate in calcimimetic users was significantly lower than that in non-users in patients ≥ 65 years of age, but not in patients < 65 years of age4. Additionally, a meta-analysis showed that calcimimetic users had a significantly reduced incidence of fractures6.

The Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study 2002–2011 found that the incidence of any fracture requiring hospitalization varied across countries, with Japan having the lowest rate (12 events/1000 patient year) and Belgium having the highest (45/1000 patient year). However, the fracture rates in HD patients were higher in comparison to the general population in all countries studied20.

Given the lower target PTH range in Japan1, it is important to analyze fracture incidence using a Japanese database. According to a study using the JRDR 2016–2017 database7, higher PTH levels were associated with an increased risk of any fracture requiring hospitalization, and this difference in risk was more pronounced in the elderly, women, and individuals with lower BMI. This suggests that lower PTH levels are desirable for individuals at high risk for fracture. Additionally, comparing the fracture incidence between calcimimetic users and non-users with similar PTH levels is necessary, as PTH levels in calcimimetic non-users were higher than those in calcimimetic users in these studies4,6. Among dialyzed patients with PTH levels within the target range, no significant difference in fracture incidence was found between calcimimetic users and non-users.

To increase the reliability of this study, we extracted data from medical records for the 3 months prior to the start of the study. First, we found that 98.5% and 99.3% of calcimimetic users and non-users, respectively, at baseline continuously had the same treatment status for the past 3 months. As noted, 96.9% of patients in the calcimimetic group received cinacalcet, while only 3.1% of patients were treated with etelcalcetide. Etelcalcetide was released in Japan in February 2017 and adopted by our corporation in April 2017. There was a possibility that either cinacalcet resistance or more severe SHPT occurred in 4 etelcalcetide users. One patient managed without cinacalcet received intravenous etelcalcetide due to PTH elevation (244 pg/mL). The PTH levels and dosages of cinacalcet before the administration of etelcalcetide in the other 3 patients were 365 pg/mL and 25 mg/day, 280 pg/mL and 25 mg/day, and 125 pg/mL and 75 mg/day, respectively. It is therefore likely that PTH levels could been controlled within the target range in 2 patients if the dosage of cinacalcet had been increased. We found no evidence that their inclusion could have driven the observed difference in mortality. In light of their very small number relative to the total cohort, we believe that excluding them would not materially change the results. For these reasons, the mortality outcome essentially represents the effect of cinacalcet. Although PTH levels were broadly similar between groups during the study, calcimimetic users likely had higher prior PTH levels, with a correspondingly greater degree of hyperplasia. The PTH values on April vs. July 2017 were 200.6 ± 139.6 vs. 141.8 ± 49.6 pg/mL (P < 0.001) before matching and 201.8 ± 139.4 vs. 142.4 ± 49.4 pg/mL (P < 0.001) after matching in users and 145.9 ± 76.7 vs. 131.9 ± 49.1 pg/mL (P = 0.006) before matching and 140.9 ± 77.2 vs. 132.7 ± 48.0 pg/mL (P = 0.539) after matching in non-users. In April, PTH levels were significantly higher in calcimimetic users than in non‑users, both before matching (P = 0.001) and after matching (P < 0.001).It is therefore suggested that continuing calcimimetic treatment to maintain lower target PTH levels improved mortality relative to non-treated patients, despite previously higher PTH levels.

The main limitation of this study was the small number of patients relative to nationwide database studies. Our corporation, which includes seven facilities, has created a unified basic healthcare management policy with the aim of eliminating any differences among facilities based on dialysis room rounding guidelines. All blood tests were performed using the same method and central measurement. We therefore consider it reliable to set a caliper value of 0.2 times the standard deviation of the logit transformed value of the propensity score for all cases, even if the number of cases is relatively small9. Second, in comparison to calcimimetic users, non-users were on average older and more frequently diabetic, despite propensity score matching. The residual imbalance remained, likely due to the limited sample size. To minimize this concern, we additionally adjusted for age, DM, and other covariates that remained imbalanced after matching in the Cox regression analysis. The results were consistent with our main findings, suggesting that the mortality benefit observed in calcimimetic users was not fully explained by these baseline differences.

Thirds, we did not determine whether calcimimetic users and non-users actually continued their respective treatments throughout the study period. We targeted patients with baseline PTH levels of 60–240 pg/mL. We assumed that calcimimetic users continued taking their medication unless their PTH levels dropped to < 60 pg/mL, and that non-users continued to not use calcimimetics unless their PTH levels rose above 241 pg/mL according to the dialysis room rounding guidelines. We then annually censored cases in which PTH levels changed to < 60 pg/mL or > 240 pg/mL, as well as cases in which the patients switched between using calcimimetics and not using calcimimetics.

Fourth, although there is a significant difference in fracture risk between men and women, especially postmenopausal women, we did not examine fracture incidence by sex or age. In this study, the male-to-female ratio was approximately 2:1, and propensity score matching included sex and age as covariates. Therefore, while we could not perform separate analyses stratified by menopausal status or age, we believe the impact of sex and age differences was at least partially controlled in our analysis. In Japan, the average age of menopause is approximately 51 years. In this study, in which PTH levels were controlled at 60–240 pg/mL, the history of fractures in women < 51 years and > 51 years was 1 of 10 (10.0%) and 5 of 123 (4.1%), respectively. The fracture incidence during the study was 7.7% in calcimimetic users and 10.0% in non-users. Further analysis of the relationship between calcimimetic use and the risk of any fracture according to menopausal status or age was limited by the small sample size and the low incidence of fractures in each group.

Fifth, serum albumin concentration was not included as a censoring variable. We considered that albumin leakage could be substituted by including it as a counterbalance variable, since we switched to dialyzers or hemodiafilters with lower albumin leakage when the level of serum albumin was < 3.0 g/dL, as measured by a photometric method with bromocresol green21. Finally, data on the residual kidney function were not available, although dialysis vintage in patients receiving HD or OHDF was > 3 months. A randomized controlled trial is needed to confirm our findings.

In conclusion, this study is the first to suggest that, among patients with PTH levels of 60–240 pg/mL on HD or OHDF using membranes with in vitro β2MG clearance of ≥ 70 mL/min, the mortality rate was significantly lower in calcimimetic users than in non-users, based on a Cox proportional hazards analysis adjusted for covariates after propensity score matching, including albumin leakage. These findings suggest that continued calcimimetic therapy may improve survival even when PTH levels fall to 60–240 pg/mL.

The HR for cardiovascular mortality in calcimimetic users with PTH levels of 29 to < 52 pg/mL, based on the time-averaged model, was 0.8 relative to the reference category (< 29 pg/mL)2. We propose that the lower limit of the PTH target be set to 30 pg/mL for calcimimetic users. These results suggest that among calcimimetic users, continuing calcimimetics—even when PTH levels fall to 30–240 pg/mL—reduces mortality relative to calcimimetics non-users. On the other hand, among HD and OHDF patients whose PTH levels were within the target range, the incidence of any fracture did not differ between calcimimetic users and non-users.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study have been deposited in the Japan Institute of Statistical Technology (https://www.jiost.com/). The data are available from the authors upon reasonable request and with the permission of the Research Ethics Committee of Kawashima Hospital.

References

Fukagawa, M. et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of chronic kidney Disease-Mineral and bone disorder. Ther. Aphr Dial. 17, 247–288. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-9987.12058 (2013).

Goto, S. et al. Hypocalcemia and cardiovascular mortality in Cinacalcet users. Nephrol. Dial Transpl. 39, 637–647. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfad213 (2024).

Taniguchi, M. et al. Serum phosphate and calcium should be primarily and consistently controlled in prevalent Hemodialysis patients. Ther. Apher Dial. 17, 221–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-9987.12030 (2013).

Moe, S. M. et al. Effects of Cinacalcet on fracture events in patients receiving hemodialysis: the EVOLVE trial. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 26, 1466–1375. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2014040414 (2015).

Khairallah, P. et al. Changes in bone quality after treatment with Etelcalcetide. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephro L. 18, 1456–1465. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.0000000000000254 (2023).

Wakamatsu, T. et al. Effectiveness of calcimimetics on fractures in Dialysis patients with secondary hyperparathyroidism: meta-analysis of randomized trials. J. Bone Min. Metab. 42, 316–325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00774-024-01500-y (2024).

Komaba, H. et al. Lower parathyroid hormone levels are associated with reduced fracture risk in Japanese patients on hemodialysis. Kidney Int. Rep. 9, 2956–2569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ekir.2024.07.008 (2024) (2956 – 2569).

Okada, K. et al. Effects of Japanese-style online hemodiafiltration on survival and cardiovascular events. Ren. Replace. Ther. 7, 70. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41100-021-00385-1 (2021).

Austin, P. C. Optimal caliper widths for propensity-score matching when estimating differences in means and differences in proportions in observational studies. Pharm. Stat. 10, 150–161. https://doi.org/10.1002/pst.433 (2011).

Abe, M. et al. Super high-flux membrane dialyzers improve mortality in patients on hemodialysis: a 3-year nationwide cohort study. Clin. Kidney J. 15, 473–483. https://doi.org/10.1093/ckj/sfab177 (2021).

Okada, K. et al. Comparison of survival for super high-flux hemodialysis (SHF-HD) with high albumin leakage versus online hemodiafiltration or SHF-HD with low albumin leakage: the SUPERB study. Ren. Replace. Ther 9, 32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41100-023-00490-3 (2023).

Okada, K. et al. Effects of high albumin leakage on survival between online hemodiafiltration and super high-flux hemodialysis: the HISTORY study. Ren. Replace. Ther. 8, 52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41100-022-00440-5 (2022).

Chertow, G. M. et al. Effect of Cinacalcet on cardiovascular disease in patients undergoing Dialysis. N Engl. J. Med. 367, 2482–2494. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1205624 (2012).

Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD-MBD Update Work group. KDIGO 2017 clinical practice guideline update for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney Int. Suppl. 7, 1–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kisu.2017.10.001 (2017).

Tentori, F. et al. Recent changes in therapeutic approaches and association with outcomes among patients with secondary hyperparathyroidism on chronic hemodialysis: the DOPPS study. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 10, 98–109. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.12941213 (2015).

Imaizumi, T. et al. Excess risk of cardiovascular events in patients in the united States vs. Japan with chronic kidney disease is mediated mainly by left ventricular structure and function. Kidney Int. 103, 949–961. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2023.01.008 (2023).

Robinson, B. et al. World-wide, mortality is a high risk soon after initiation of Hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 85, 158–165. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2013.252 (2014).

Lim, K., Hamano, T. & Thadhani, R. Vitamin D and calcimimetics in cardiovascular disease. Semin Nephrol. 38, 251–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semnephrol.2018.02.005 (2018).

Shoji, T. et al. Comparative effects of Etelcalcetide and maxacalcitol on serum calcification propensity in secondary hyperparathyroidism: A randomized clinical trial. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 16, 599–612. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.16601020 (2021).

Tentori, F. et al. High rates of death and hospitalization follow bone fracture among Hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 85, 166–173. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2013.279 (2014).

Okada, K. et al. Improved survival on super high flux-albumin leaking Hemodialysis and online hemodiafiltration with high albumin leakage in patients with mild hypoalbuminemia: evidence and a hypothesis. Ren. Replace. Ther. 10, 27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41100-024-00543-1 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all of the staff in our medical corporation for providing a similar quality of healthcare management and dialysis conditions across facilities. We are also grateful to Dr. Shigeaki Ohtsuki of Japan Institute of Statistical Technology for performing the statistical analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.O. was responsible for the research idea and study design, and contributed to the drafting of the manuscript. M.T., S. Y,. T.I., T.K. and J.M. contributed to the design, interpretation of data and revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Okada, K., Tashiro, M., Yamaguchi, S. et al. Lower mortality in calcimimetic users compared to non-users in dialysis patients with serum parathyroid hormone levels within the target range. Sci Rep 16, 241 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29458-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29458-5