Abstract

Water loss in soil and plants occurs through processes such as evaporation and transpiration, giving rise to evapotranspiration. In water resource management and precision agriculture, it is important to have accurate estimates of water loss in order to optimize agricultural irrigation and improve crop productivity. To estimate evapotranspiration data, this study used different machine learning methods such as multiple linear regression, polynomial regression, and neural networks using libraries such as Scikit-learn, Statsmodels, TensorFlow, and Keras. Climate data gathered by the Cenicaña weather station located in Florida, department of Valle del Cauca, Colombia, were used to train the machine learning models and later compare evapotranspiration estimates based on the FAO 56 Penman–Monteith method. To ensure the best estimate, 13 different data combinations were used, each combination involving three of the six parameters studied. Combinations involving relative humidity and minimum, maximum or mean temperatures showed the lowest precision, presenting values such as R = 0.7, R2 = 0.51 and RMSE = 0.57, as compared with combinations that considered net radiation and wind speed, which presented the most accurate predictions with values of R = 0.99, R2 = 0.98 and RMSE = 0.73. These results highlight the relevance of machine learning models in estimating evapotranspiration, particularly in areas with limited availability of climate data.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Evapotranspiration (ET) describes water loss in the soil due to evaporation and in the plant due to transpiration (Allen et al. 2006)1,2. It is influenced by climate factors (solar radiation, ambient temperature, relative humidity, wind speed), cultivation conditions (crop, variety, phenological stage), crop management and environmental conditions (soil characteristics such as texture, structure and density, soil water content, vegetation cover, among others), (Allen et al. 2006)1,3.

It is fundamental for farmers to measure ET because this information allows them to design irrigation schemes and optimize water use to satisfy crop water requirements more efficiently [5]. The measurement of ET involves the use of specialized equipment and meticulous measurements of several physical parameters using methods such as energy and microclimatic balance, soil water balance or lysimeters. These methods, however, are not only expensive, but also demand highly qualified personnel and therefore considered not suitable for routine measurements but rather for the evaluation of indirect methods. (Allen et al. 20061).

As a result, it is common to use weather data to calculate ET (Allen et al. 20061). Over the years, different empirical and analytical equations have been developed based on different climate parameters. These, however, are mostly site-specific and used for specific climate and agronomic conditions. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) therefore proposed a standard method to calculate reference evapotranspiration (ETo), referred to as the FAO 56 Penman–Monteith (PM) method (Allen et al. 2006)1,2,4,5.

Crop evapotranspiration (ETc) is calculated based on the ETo and is determined by multiplying the ETo by the crop coefficient (Kc). This yields the ETc/ETo ratio, which can be determined experimentally for different crops, so that ETc = Kc x ETo. However, ETc also depends on plant phenological stage and crop species, as crop characteristics may vary during the different growth periods. The ETc is determined under standard cropping conditions and refers to the amount of water lost through ET, measured in terms of water sheet (mm) (Allen et al. 20061).

To precisely calculate ET, data must be available on several climate variables such as maximum and minimal temperature, relative humidity, solar radiation, wind speed and water vapor pressure. However, the lack of precise climate data is a widespread problem worldwide. Malfunctioning of weather stations generates the loss of crucial information, and their maintenance or repair is usually complex due to their remote locations. In addition, limited access to data on variables such as solar radiation restricts the use of empirical equations, adversely affecting the precision of ET calculations6,7.

Thanks to the rapid development of both computing capacity and artificial intelligence (AI), determining ET based on weather data has been considered a regression task that can be addressed by different automated learning models such as classic machine learning (CML) and deep learning (DL)8. Machine learning (ML) technology has also proven useful to predict temporary data series, without prior knowledge of physical processes, basing ET estimation on a limited amount of weather data4,5,9,10.

Different studies have shown that ML techniques, such as artificial neural networks (ANNs), support vector machines (SVMs), extreme learning machines (ELMs), and random forest (RF), can precisely predict ET, and that these CML models perform better than empirical models5,6,11,12,13.

They also suggest that the appropriate algorithm to estimate ET may differ depending on the spatial and climate characteristics of study targets and training data composition due to ML characteristics that reproduce empirical patterns4,5,8,13. This is because ML is a subsection of AI that uses previous experience (data training) to learn and then apply it to execute new tasks. As AI maps non-linear relationships between input and output variables, prediction precision is improved10,14.

Based on the above, in this study the ETo is calculated from two third-degree polynomial linear regression models with different libraries, a multivariate linear regression model and a ANN. The data obtained were compared with the ETo calculated using the FAO 56 PM method, and the correlation values between the different ML algorithms used are determined to define their level of accuracy.

Materials and methods

According to the recommendations of different researchers15, it is essential to follow the steps outlined in Fig. 1 when developing a ML model to estimate ET in an area where some of the weather variables are unknown.

Each ML model used has a specific characteristic that differentiates it from the rest. Both multivariate linear regression and polynomial regression are based on their mathematical definitions and how they model the relationship between variables. Multivariate linear regression assumes the existence of a linear relationship between predictor variables and the response variable16. This means that the model seeks to fit a straight line that best fits the data. On the other hand, multivariate polynomial regression allows polynomial-type relationships between variables, meaning that it can capture more complex and nonlinear relationships between variables16,17. This is achieved by including higher-degree polynomial terms in the model, which allows a more flexible relationship between variables as well as a better fit to data not following a linear trend17. The differences between linear regressions and neural networks can also be inherent. Linear regression is simpler and easier to interpret as it is represented by an equation at the end of the process16, whereas neural networks offer greater flexibility and ability to model complex relationships between data, but do not have an equation that represents them. Neural networks have proven to be better in situations involving nonlinear problems. However, this additional flexibility can come at the cost of increased complexity and difficulty in interpreting model results18.

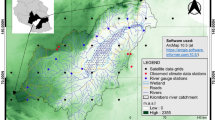

Gathering of weather data in the study area

Data of a series of weather variables collected by the Cenicaña automated station located in the municipality of Florida, department of Valle del Cauca (latitude 03° 21′ 37.38 N; longitude 76° 17′ 59.90 W; altitude, 1020 m above sea level), were used to study ET using ML methods. These weather variables were as follows: mean temperature “Tmean”, minimum temperature “Tmin”, maximum temperature “Tmax”, mean relative humidity “Hu”, solar radiation “Ra” and mean wind speed “u”. The historical period covered went from 1 January 1994 to 31 December 2014.

Equation 1 indicates the data used to determine PM ET.

where:

-

ETo = reference ET (mm/day)

-

Rn = net radiation (MJ/m2/day)

-

G = ground-level heat (MJ/m2/day)

-

T = air temperature 2 m above ground level (°C)

-

u = wind speed 2 m above ground level (m/sec)

-

es = saturation vapor pressure (kPa)

-

ea = real air vapor pressure (kPa)

-

Δ = vapor pressure deficit (kPa/°C)

-

\(\upgamma\) = psychrometric constant (kPa/°C)

Datasets

One of the main purposes of ML applications is to predict dependent variables using a limited dataset [21]. This study accordingly carried out a process of selection and clustering of weather variables. From the initial data pertinent to six climate variables, 13 smaller datasets were created, each clustering three climate variables, as detailed in Table 1. These subsets were used as input for the ML models.

Machine learning

For the ML process, each data subset was divided into training and testing datasets, with 80% destined for training and 20% for performance testing as recommended by Kim et al.18and Chacón Ch19.. This division allows the model’s generalization capability to be assessed by exposing it to data not seen during training.

Although this “hold‑out” approach is widely used, previous studies have highlighted that simple 80 / 20 splits may fail to expose models to the full range of relevant events20,21, introduce bias depending on which portion of the time series is reserved for testing20, overlook temporal dependencies and autocorrelation in hydrometeorological data20, provide only a partial view of over‑ or underestimation trends, and increase the risk of overfitting or underfitting, particularly when extreme values are unevenly allocated20,22. More rigorous validation techniques such as k‑fold cross‑validation, temporal validation using complete growth‑season blocks, and spatial generalization via auxiliary station data have therefore been recommended20,21,23,24. Nevertheless, given the simplicity and prevalence of the hold‑out method in the literature, we have applied the 80 / 20 split in this study.

Training data were used to streamline model parameters, whereas testing data was reserved to assess its performance once the model was trained. This separation helps avoid model overfitting25.

Three linear regression models and one ANN model19 were evaluated to determine ETo using the station’s weather variables. These three linear regression models were (1) third-degree polynomial linear regression with the Sklearn library (POL_SK), third-degree polynomial linear regression with the Statsmodels library (POL_ST) and multivariate linear regression with the Statsmodels library (RLMULTI_ST). The neural network was created with the help of the Keras and Tensorflow libraries (RED_N). In addition, the Numpy, Pandas, and Matplotlib libraries were used to create and mathematically manage the linear regression models.

The models were trained to predict the ETo value according to the FAO 56 PM method.

Performance testing

Three performance tests were conducted to (1) determine the performance and accuracy of each of the models, and (2) identify the best combinations of climate variables against the known ETo generated by FAO 56 PM. These were the Pearson correlation coefficient (Cxy), the coefficient of determination (R2) and the root mean square error (RMSE) [8]. Each test was carried out for each model applied to each of the combinations presented in Table 1.

Pearson correlation coefficient (Cxy):

where:

-

\({C}_{xy}=\) Pearson correlation coefficient

-

\({x}_{i}=\) PM ET value

-

\(\overline{x} =\) Mean of the PM ET value

-

\({y}_{i}=\) Prediction value as determined by the ML model

-

\(\overline{y}=\) Mean of prediction value as determined by the ML model

Coefficient of determination (R2):

where:

-

\({R}^{2}=\) Coefficient of determination

-

\(\overline{{\varvec{x}} }=\) PM ET value

-

\({x}_{i}=\) Mean of the PM ET value

-

\({y}_{i}=\) Prediction value determined by the ML model

Root mean square error (RMSE):

where:

-

\(RMSE\) = Root mean square error

-

\({x}_{i}=\) PM ET value

-

\({y}_{i}=\) Prediction value as determined by the ML model

Results and discussion

The ETo was predicted based on the ML models used, and performance tests were generated for each of the evaluated subsets as shown in Table 2.

Performance tests were used to determine the best ratio between estimated ETo value and actual ETo value. In this analysis, it is important to highlight that the three regression models (RLMULTI_ST, POL_SK and POL_ST) exhibit greater stability, with a mean correlation coefficient of 0.859 for RLMULTI_ST and 0.873 for POL_SK/POL_ST, while the neural network (RED_N) reaches 0.863. Additionally, the average RMSE of the regressions is 0.28 , approximately, compared to 0.63 for RED_N, confirming the higher precision of polynomial methods on this dataset (Table 3).

However, the variable combinations in Table 1 “Tmax, Ra, u” (combination 1), “Tmax, Hu, u” (combination 3), “Tmean, Ra, u” (combination 4), and “Tmin, Ra, u” (combination 7) showed Cxy and R2 values greater than 0.9 (Table 2), indicating a strong correlation and that these are the best combinations to accurately estimate ET. This superior performance is physically linked to the fact that solar radiation (Ra) and wind speed (u) are the most influential variables in the FAO56‑PM equation and, at Cenicaña station, exhibit low extreme variability, favoring the consistency of polynomial models.

Meanwhile, the combinations “Tmean, Tmin, Hu”, “Tmin, Tmax, Hu”, “Tmax, Tmean, Tmin” and “Tmax, Tmean, Hu” showed Cxy and R2 values less than 0.8 (Table 2), indicating a low correlation as compared with the other combinations evaluated. Omitting critical variables such as solar radiation (Ra) and wind speed (u) markedly reduces the predictive capacity of ML models. In fact, when averaging the R2 values of combinations that include only one of these variables, we obtain approximately 0.75, whereas when both are present, the mean R2 rises to 0.98, confirming their decisive representativeness and influence on ETo estimation. Conversely, for combinations that include neither Ra nor u, the mean R2 falls to around 0.598 across all models, highlighting how essential the inclusion of these two variables is for improving prediction accuracy and consistency.

In a study conducted with weather data pertinent to the Adana plain in Turkey26, R2 values ranged from 0.6 to 0.922 in performance tests using a multivariate linear regression model to determine ET, which is consistent with the data found in this study. The most accurate R2 for the Adana plain was found with the parameters “Tmax, Tmin, ea, es, u, extraterrestrial radiation, hours of sunlight”, which agrees with the results of this study because the wind speed parameter is present in the combinations presenting best R2. The near‑identical performance demonstrates that third‑degree polynomial regression models (POL_SK, POL_ST) can match the accuracy of the FAO56‑PM reference method, despite not being explicitly based on its physical equations. These models effectively infer and replicate the same underlying physical relationships with high fidelity, particularly when site‑specific climatic conditions do not exhibit abrupt fluctuations.

Similarities were found in a study conducted in India using multivariate linear regressions to determine the ETo with different numbers of input parameters27, where R2 coefficients ranged from 0.746 to 0.950, the lowest value being obtained for two input parameters and the highest value for six-input parameters. This indicates that with an increasing number of parameters submitted to the models, the higher their accuracy. Likewise, by using variables such as maximum and minimum temperature, wind speed, relative humidity and hours of sunlight, the ETo calculated using ML models is close to the values obtained by the FAO 56 PM method. However, an increased number of variables also raises model complexity; our polynomial regressions maintained an average RMSE of 0.277 even with three variables, whereas RED_N reached 0.630, indicating lower tolerance to input noise.

On the other hand, RMSE values follow a pattern like those of the Cxy and R2 coefficients. Hence, the combinations presenting the best values for these coefficients also show a low RMSE. When these results were compared with those of the studycarried out by Koç and Erkan in Turkey’s Adana Plain26, values were very similar, as the combinations including Ra and u showed a better predictive ability due to the important role they play in the FAO 56 PM equation28. The consistency of these errors reinforces the hypothesis that combinations with Ra and u are more stable in environments with controlled thermal variability, as in the present study the results suggest a high correlation of these variables for estimating Eto with ML methods.

The POL_SK and POL_ST models present identical values, indicating that, although the process for generating algorithms and their presentation differ, their results are identical. This reproducibility (identical mean RMSE of 0.277 and mean Cxy of 0.873) demonstrates the robustness of the Scikit‑Learn and Statsmodels implementations.

In study on ET carried out by Kim et al. in South Korea based on data gathered from multiple weather stations19 , third-degree polynomial regressions were observed to reach R2 values ranging from 0.536 to 0.537, which are very low compared with those found in the present study. The discrepancy in R2 values between the two studies may be attributed to the increase in the number of weather stations evaluated and the implementation of an algorithm that provides zonal ET, indicating that linear regressions may lose precision in zonal ET studies. This contrast illustrates the limitation of polynomial regressions in contexts of high spatial heterogeneity, where RED_N could outperform if network architecture and validation are adjusted.

The least accurate model, according to the performance test results indicated in Table 2, is RED_N, evidenced by its lower Cxy and R2 correlation coefficient values in comparison with other models, as well as its higher RMSE values. For example, in the combination “Tmin, Ra, u”, the average RMSE value of the regressions was 0.11, whereas for the neural network it was 0.73, indicating a significant discrepancy in prediction accuracy between the neural network and other models regarding this specific dataset. his greater error in RED_N is consistent with its mean RMSE of 0.630, highlighting the need for deeper architectures and regularization to improve performance on long-term time series.

Compared with the results of the aforementioned study conducted by Pangam et al. in India26, apart from the multivariate linear regressions, neural networks with a variable number of data inputs and a single processing layer (hidden layer) were used. In this case, R2 data ranging from 0.827 to 0.997 were obtained, giving the lowest values for two-input parameters and the highest value for six-input parameters, confirming the hypothesis that with increasing number of climate variables, the higher the model accuracy will be with respect to the ETo value obtained by FAO 56 PM. These superior results suggest that RED_N can improve substantially with deeper architectures, as our data show that a single layer limits its potential.

A study conducted by El-Magd et al. in Egypt used neural networks with variable number of data inputs and a single processing layer to determine ET, finding similar data for Cxy (0.838‒0.959) and for RMSE (0.453‒0.857)28. The highest Cxy value and the lowest RMSE value were obtained for data such as Tmax, Tmin, dew point temperature (Tdw), wind speed (u) and precipitation (P), highlighting the importance of the variables “temperature” and “wind speed” in the model. This annotation is clear in the RED_N model as Cxy values are above 0.9 for these input data, dropping to 0.8 if relative humidity is included.

It should be highlighted that the accuracy of the neural network with three processing layers and three inputs was similar to that of neural networks with one processing layer and six inputs, based on the Cxy, R2 and RMSE data presented in Table 2. This highlights the importance of neural network architecture for the best determination of ETo; however, it is recommended to study how these changes fluctuate with a given dataset.

As can be observed in Table 2, there are similarities in the data of performance tests carried out using ML models. However, it should be highlighted that for all combinations, the RMSE values of neural networks are higher in comparison with those of regression models.

Together, these results suggest that, for Cenicaña station over 1994–2014, third-degree polynomial regressions balance complexity and interpretability more effectively, whereas neural networks require additional architectural tuning and more rigorous validation to outperform physics-based FAO56‑PM methods.

In our findings, third-degree polynomial regressions (POL_SK/POL_ST) maintain a high mean correlation coefficient of 0.8731 and a low mean RMSE of 0.277, confirming their stability under moderate ETo variability, as observed at Cenicaña. Studies in arid climates of Iran show that linear models outperform ANFIS and ANFIS‑DE thanks to strong linear autocorrelation, analogous to our polynomial regressions when including radiation and wind29. In the sub‑humid and semi‑arid regions of Morocco, hybrids like XGBoost‑LightGBM reached R2 close to 0.95, matching our finding that adding wind speed and humidity greatly improves precision22.

Meanwhile, the RED_N network achieved a mean correlation coefficient of 0.8638 and a mean RMSE of 0.630, evidencing its greater sensitivity to architecture and data volume, as reported for ANN‑M1 in southwest Colombia, where high accuracies were achieved only with deeper nets or local calibration5. In insular arid environments of Iran, wind speed explained most ETo variability, reinforcing the need always to include u21,in fact, our wind-inclusive combinations raised R2 from 0.75 to over 0.90. Finally, cases in Bangladesh and Malaysia, where simple radiation or MLP‑NN models achieved Cxy > 0.90, show that, although FAO56‑PM’s physics provides a solid foundation, the key to improving RED_N lies in tuning its depth and temporal validation, thus ensuring robust generalization across climatic regimes30,31.

The FAO 56 PM method, while considered the gold standard for estimating reference evapotranspiration (ETo), imposes important limitations when employed as the training target for machine learning (ML) models5,20,21,22,24,29,31,32,33,34. Since FAO56‑PM depends on multiple meteorological inputs (air temperature, relative humidity, solar radiation, and wind speed) any gaps or inaccuracies in these data directly degrade ML performance5,20,22,31,32,34,35.

Moreover, because FAO56‑PM yields a calculated rather than directly measured value, ML algorithms trained on these estimates may inherit and even amplify biases, such as the known overestimation of ETo in arid climates22,32. Thus, whereas FAO56‑PM’s physical formulation is transparent, many ML models act as “black boxes,” obscuring how inherited biases impact predictions22,32. To mitigate these effects, rigorous validation schemes: k‑fold cross‑validation with growth‑season folds, temporal strategies that preserve series continuity, and spatial generalization using auxiliary station data, are recommended20,24,33. Nevertheless, given its widespread adoption, FAO56‑PM remains our reference for model training.

Conclusions

The application of machine learning (ML) methods, including linear regression and neural networks, demonstrated high effectiveness in estimating evapotranspiration (ET) even in the absence of comprehensive climate data. Notably, these models achieved remarkable accuracy, with R2 values reaching up to 0.99, underscoring their potential for reliable ET prediction in data-scarce regions. These findings highlight the feasibility of integrating advanced ML techniques into water resource management and precision agriculture, particularly where traditional climate data is limited.

Among the tested variables, four three-parameter combinations—Tmin/Ra/u, Tmean/Ra/u, Tmax/Hu/u, and Tmax/Ra/u—emerged as the most effective for ML-based ETo modeling, all yielding R2 > 0.9. This suggests that solar radiation (Ra), wind speed (u), and temperature variants (Tmin, Tmean, Tmax) or humidity (Hu) are key drivers of accurate ETo prediction in data-constrained scenarios and solar radiation and wind speed are the most influential variables in the FAO56 PM.

Furthermore, the three-layer neural network model, utilizing three input parameters, exhibited exceptional performance in ET estimation, achieving an R2 of 0.99. However, despite its strong correlation, the model’s root means square error (RMSE) ranged between 0.57 and 0.87, suggesting some variability in absolute error that should be considered in practical applications. It is suggested to explore multi-layered and deeper neural network architectures.

These results emphasize the promise of ML-driven approaches for enhancing agricultural water management, particularly in regions facing climate data limitations, while also indicating areas for further refinement to reduce prediction errors.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed in this study are not publicly available because the meteorological network belongs to the Colombian sugarcane agroindustry (ASOCAÑA-CENICAÑA). The network is owned by them, and publication of the datasets is not permitted. However, they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Allen et al. A Recommendation on Standardized Surface Resistance for Hourly Calculation of Reference ETo by the FAO 56 Penman-Monteith Method. Agricultural Water Management 81(1–2), 1–22, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2005.03.007 (2006).

Treviño López, E.A. Estimación de la evapotranspiración real en cultivos hortícolas bajo condiciones de invernadero. Specialization in Applied Chemistry, Centro de Investigación en Química Aplicada (CIQA). (2004). Available online: https://ciqa.repositorioinstitucional.mx/jspui/bitstream/1025/366/1/Eduardo%20Alfonso%20Trevi%C3%B1o%20Lopez.pdf.

CENICAÑA (Centro de Investigación de la Caña de Azúcar de Colombia). Evapotranspiración del cultivo–Cenicaña, (2015). Available online: https://www.cenicana.org/evapotranspiracion-del-cultivo-etc/ (accessed 2 December 2023).

Al-Mousawi, N. M. M., Al-Jiboori, F. H. & Al-Shawi, A. A. Linear regression machine learning algorithms for estimating reference evapotranspiration using limited climate data. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 16(6), 15–24 (2023).

Triana-Madrid, J. C. et al. Estimation of monthly reference evapotranspiration with scarce information using machine learning in southwestern Colombia. Meteorologica https://doi.org/10.24215/1850-468Xe024 (2023).

Herrera, W., Bedoya, O. & Rincón, M. Aplicación de redes neuronales para la reconstrucción de series de tiempo de precipitación y temperatura utilizando información satelital. Rev. EIA 17(34), 34008. https://doi.org/10.24050/reia.v17i34.1292 (2020).

Jimenez, V., Will, A., Rodriguez, S., Lamelas, C. Imputación de Datos Climáticos Utilizando Algoritmos Genéticos Niching. In Acta de la XXXVII Reunión de Trabajo de la Asociación Argentina de Energías Renovables y Medio Ambiente (ASADES). 2, 11139‒11148, (2014).

Chen, Z., Zhu, Z., Jiang, H. & Sun, S. Estimating daily reference evapotranspiration based on limited meteorological data using deep learning and classical machine learning methods. J. Hydrol. 591, 125286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2020.125286 (2020).

Das, S., Baweja, S. K., Raheja, A., Gill, K. K. & Sharda, R. Development of machine learning-based reference evapotranspiration model for the semi-arid region of Punjab, India. J. Agric. Food Res. 13, 100640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafr.2023.100640 (2023).

Považanová, B., Čistý, M. & Bajtek, Z. Using feature engineering and machine learning in FAO reference evapotranspiration estimation. J. Hydrol. Hydromech. 71(4), 425–438. https://doi.org/10.2478/johh-2023-0032 (2023).

Aly, M. S., Darwish, S. M. & Aly, A. A. High performance machine learning approach for reference evapotranspiration estimation. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 38, 689–713. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00477-023-02594-y (2024).

Duhan, D. et al. Modeling reference evapotranspiration using machine learning and remote sensing techniques for semi-arid subtropical climate of Indian Punjab. J. Water Clim. Change 14(7), 2227–2243. https://doi.org/10.2166/wcc.2023.003 (2023).

Mendoza, C. & Peña, Q. Reference evapotranspiration estimation by different methods for the sucroenergy sector of Colombia. Rev. Bras. Eng. Agric. Ambient. 25(9), 583–590. https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-1929/agriambi.v25n9p583-590 (2021).

Bhandari, S., Sharpe, C. A., Hayes, M. J. 2021 Assessing the performance of machine learning models for estimating reference evapotranspiration in a semi-arid climate. Agric. Forest Meteorol. 290p.

Moncho V., J. Análisis de regresión lineal simple y múltiple. In Moncho V. J., Eds. Estadística Aplicada a las Ciencias de la Salud. 157‒223 ,Elsevier, (2015) https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-84-9022-446-5.00005-7 and https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9788490224465000057.

Dong, Q.; Chen, X.; Huang, B. Regression. In Dong, Q., Chen, X., Huang, B., Eds. Data Analysis in Pavement Engineering. 107‒140. (Elsevier, 2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-443-15928-2.00018-5

Mulyadi, A.W.; Yoon, J.S.; Jeon, E.; Ko, W.; Suk, H.-I. An introduction to neural networks and deep learning. In Zhou, S.K., Greenspan, H., Shen, D., Eds. Deep Learning for Medical Image Analysis, 2nd ed. 3‒31 (Academic Press, 2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-32-385124-4.00009-X

Kim, S.-J., Bae, S.-J. & Jang, M.-W. Linear regression machine learning algorithms for estimating reference evapotranspiration using limited climate data. Sustainability 14(18), 11674. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811674 (2022).

Chacón Ch., M.V. Estudio de la reducción del sobreajuste en arquitecturas de redes neuronales residuales ResNet en un escenario de clasificación de patrones. Master’s Degree in Science–Applied Mathematics, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Faculty of Exact and Natural Sciences, Manizales, Colombia, 2023.

Hossein Kazemi, M., Shiri, J., Marti, P. & Majnooni-Heris, A. Assessing temporal data partitioning scenarios for estimating reference evapotranspiration with machine learning techniques in arid regions. J. Hydrol. 590, 125252. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JHYDROL.2020.125252 (2020).

Shiri, J. Modeling reference evapotranspiration in island environments: Assessing the practical implications. J. Hydrol. 570, 265–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JHYDROL.2018.12.068 (2019).

Acharki, S. et al. Comparative assessment of empirical and hybrid machine learning models for estimating daily reference evapotranspiration in sub-humid and semi-arid climates. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41598-024-83859-6 (2025).

Biazar, S. M., Shehadeh, H. A., Ghorbani, M. A., Golmohammadi, G. & Saha, A. Soil temperature forecasting using a hybrid artificial neural network in Florida subtropical grazinglands agro-ecosystems. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41598-023-48025-4 (2024).

Shiri, J., Marti, P., Karimi, S. & Landeras, G. Data splitting strategies for improving data driven models for reference evapotranspiration estimation among similar stations. Comput. Electron. Agric. 162, 70–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COMPAG.2019.03.030 (2019).

Koç, D. L. & Erkan Can, M. Reference evapotranspiration estimate with missing climatic data and multiple linear regression models. PeerJ 11, e15252. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.15252 (2023).

Pangam, H., Singh, P. K., Rao, K. V. R. & Subeesh, A. Modelling reference evapotranspiration using gene expression programming and artificial neural network at Pantnagar, India. Inf. Process. Agric. 10(4), 547–563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inpa.2022.05.007 (2023).

Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Raes, D.; Smith, M. Crop Evapotranspiration: Guidelines for Computing Crop Water Requirements. FAO Irrigation and Drainage Paper No. 56. 300 (1998).

El-Magd, A.A.; Baraka, S.M.; Eid, S.F.M. Using artificial neural networks to predict the reference evapotranspiration. J. Water Land Dev. 2023, 57, 1‒8. https://doi.org/10.24425/jwld.2023.143768.

Aghelpour, P., Varshavian, V., Khodamorad Pour, M. & Hamedi, Z. Comparing three types of data-driven models for monthly evapotranspiration prediction under heterogeneous climatic conditions. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41598-022-22272-3 (2022).

Hanoon, M. S. et al. Developing machine learning algorithms for meteorological temperature and humidity forecasting at Terengganu state in Malaysia. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41598-021-96872-W (2021).

Salam, R. et al. The optimal alternative for quantifying reference evapotranspiration in climatic sub-regions of Bangladesh. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41598-020-77183-Y (2020).

Ruiz-Ortega, F. J., Clemente, E., Martínez-Rebollar, A. & Flores-Prieto, J. J. An evolutionary parsimonious approach to estimate daily reference evapotranspiration. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41598-024-56770-3 (2024).

Sarkar, S. S., Bedi, J. & Jain, S. A deep learning based framework for enhanced reference evapotranspiration estimation: evaluating accuracy and forecasting strategies. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41598-025-99713-2 (2025).

Shiri, J. et al. Evaluation of different data management scenarios for estimating daily reference evapotranspiration. Hydrol. Res. 44(6), 1058–1070. https://doi.org/10.2166/NH.2013.154 (2013).

Manuel Gríllo, F. (1971). DETERMINACION DE LA EVAPOTRANSPIRACION CON LISIMETROS. ACTA AGRONÓMICA, XXI, 179–196

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Model validation and comparative adjustment using evapotranspiration data generated by model use and, analysis of results and editing of manuscript, C.J. Mendoza-Castiblanco and C.A. Cortés-Bello; adjustment of programming and evaluation of machine learning models, A.F. Rodríguez-Vasquez; development and implementation of machine learning models used in the process, J.F. Rueda-Cadavid and D.M. Cañón-Castillo.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rueda Cadavid, J.F., Cañón Castillo, D.M., Mendoza Castiblanco, C.J. et al. Evaluating machine learning models for estimating evapotranspiration in Colombia’s Cauca River Valley. Sci Rep 16, 278 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29514-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29514-0