Abstract

Health anxiety is often linked to lower pain thresholds and heightened sensitivity to health-related stimuli, yet the relationship between these psychological and physiological traits remains complex. In this study, we relied on the use of the brain’s ability to discriminate fast and periodically presented stimuli (i.e. oddballs) of a given image category within a stream of unrelated images, to investigate whether neural responses to health-related visual stimuli are associated with individual differences in pain sensitivity and psychological traits such as anxiety and depression. We hypothesized that, if the periodically presented health-related oddball elicits a periodic neural response, this image category might lead to a stronger response in individuals with health anxiety and psychological malaise. This is the first evidence that periodically presented health-related images elicit a neural response which can be clearly differentiated from unrelated images. Additionally, this response shared a relationship with depression, which was in turn moderated by the pain threshold. While these results offer insight into the interaction between psychological traits, pain threshold and the processing of health-related images, future studies will have to confirm the specificity of the obtained relationships.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The human brain continuously processes external stimuli, often below the level of conscious awareness1. Among these, health-related stimuli are of particular interest due to their potential relevance for survival and well-being. Understanding how the brain responds to such stimuli, even when they are not consciously perceived, can shed light on interacting mechanisms of conceptual and visual processing. The present study aims to investigate whether the brain shows an implicit processing of health-related images and whether this response is modulated by individual psychological traits such as anxiety, emotion regulation, impulsivity, and stress or the individuals’ pain threshold.

Health anxiety, a construct characterized by excessive worry and preoccupation with one’s health2, provides a compelling framework for examining selective and heightened sensitivity to health-related stimuli. Numerous studies have shown that individuals with high levels of health anxiety tend to exhibit selective attention to illness-related information3,4, and this attentional bias is often accompanied by stronger emotional and physiological responses when confronted with such stimuli. These findings suggest that health-related stimuli may trigger stronger responses in the brain, especially in individuals with elevated anxiety levels. However, the neural mechanisms underlying these responses remain underexplored, and understanding the neural underpinnings of these responses is crucial for developing effective interventions and therapies.

To address this, our study seeks to determine whether we can capture neural responses elicited by health-related stimuli. To this end, we employed the Fast Periodic Visual Stimulation (FPVS) paradigm. This technique is based on the well-established principle that a periodic stimulation elicits a periodic modulation of the EEG signal at the frequency of the stimulation and its harmonics5. Thus, when combined with electroencephalography (EEG), this paradigm allows to “tag” the neural response to a periodic oddball stimulus within a stream of unrelated images at the frequency at which both the oddballs and unrelated images were presented. This paradigm has been widely applied in vision research6, with a particular success in the studies of facial discrimination (see Rossion, et al.7 for a comprehensive review). Additionally, it has been successfully implemented in object categorization8, the recognition of letters and words9,10, as well as visual recognition of semantic categories11,12. To our knowledge, this is the first application of FPVS to differentiate between health-related and neutral visual stimuli, adding a novel dimension to the growing body of research using the FPVS paradigm.

In addition to assessing the neural response to these stimuli, we also explored the potential role of individual psychological traits in modulating this response. Psychological factors such as anxiety, emotion regulation, impulsivity, coping strategies and stress have been linked to attentional biases and heightened emotional reactivity13,14,15,16. Specifically, trait anxiety, particularly health anxiety, has been associated with an increased focus on threat-related or illness-related information, as demonstrated in numerous behavioral and neuroimaging studies17,18. Moreover, the interplay between health anxiety and individual traits such as impulsivity and emotional regulation is an area ripe for exploration. Impulsivity may drive individuals to react quickly and sometimes maladaptively to health-related stimuli, while effective emotional regulation can help mitigate anxiety responses. By examining these traits in conjunction with neural responses to health-related images, we aimed to elucidate the complex relationships that govern how individuals with varying levels of health anxiety engage with health-related information. We hypothesized that individuals with higher levels of anxiety and related traits may exhibit a stronger unconscious neural response to health-related stimuli, as measured by EEG during the FPVS task.

Furthermore, we investigated the potential contribution of physical traits, such as the individual pain threshold, to the neural processing of health-related stimuli. Pain is inherently linked to health and survival and engages in both psychological and physiological processes. Previous research reports that individuals with high levels of anxiety, including health anxiety, tend to experience lower pain thresholds19,20 and higher pain sensitivity21,22. These findings are consistent with the well-established understanding that pain perception is influenced not only by physical factors, but also by affective and cognitive processes - particularly anxiety.

Moreover, recent research suggests that individual differences in pain perception are closely tied to neural responses to threat and health-related cues23,24,25. In this study, we used thermal cutaneous stimulation to measure pain thresholds and assess whether individuals with lower pain thresholds exhibit heightened neural responses to health-related stimuli, aiming to understand how both psychological and physical traits may jointly influence the brain’s reaction to health-related information. Psychological constructs were measured using validated questionnaires, each selected for its established link with attention to threat, emotional reactivity, or health-related cognitive biases. Based on previous research, the underlying hypothesis is that the periodic brain response to health-related images may be associated with higher features of psychological distress.

In summary, we investigated whether the brain is able to distinguish periodically presented health-related images from a stream of random images and explored whether this response is associated with individual differences in psychological traits and pain thresholds.

Results

Participants completed a series of questionnaires assessing their psychological traits, as well as a measurement of their individual pain threshold. Then, participants had to focus on fast periodic visual stimuli depicting health-related images, which were embedded in a periodic stream of unrelated images, while their neural response to the visual stimuli was measured using EEG.

Behavioral response

To ensure that participants were paying attention to the presented visual stimuli, they had to count the number of times the dot in the middle of the presented visual stimuli changed to the color red within each trial. Accuracy rates in this behavioral task were similar in both conditions (Original: 33.88% ± 12.28%; Scrambled: 36.72% ± 11.44%) and no significant difference was found between conditions in accuracy rates (F(1,40) = 1.327, p = 0.256, ηp2 = 0.032).

Neural response

In the scrambled condition, only few and nonconsecutive oddball harmonics were statistically different from zero (i.e., z-score > 1.64). Conversely in the original condition, all oddball harmonics up to the 5th harmonics (i.e. ~7.29 Hz) showed a significant periodic response to the health-related visual stimuli. Thus, for the statistical analysis, the response at the oddball frequency was summed up with the first 5 of its harmonics (excluding the 4th harmonic at ~ 6 Hz, which overlaps with the base presentation rate). To be consistent, the same number of oddball harmonics was summed up in the scrambled condition. Following the same rationale, the response at the base presentation rate was aggregated with its first harmonic in both conditions. Thus, 4 main responses were consecutively analyzed: an aggregated amplitude consisting of oddball responses and an aggregated amplitude consisting of responses at the base presentation frequency, for both conditions separately.

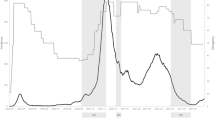

Congruent to other investigations using the FPVS paradigm, the largest response to the original images at this aggregated base presentation frequency was found at electrode PO8 (0.75 ± 0.65 µV, range: 0.09–2.56 µV), which was thus chosen as electrode of interest for the original image condition. In the scrambled condition, responses were mainly found at the base frequency at electrode Oz (0.66 ± 0.47 µV, range: 0.07–2.05 µV). Figure 1a illustrates the frequency spectra for these EEG responses at electrodes PO8 (original images) and Oz (scrambled images) in both conditions. For the correlation with pain thresholds and personality traits, the aggregated oddball response (i.e. signal at electrode PO8 in the original images condition) was used (0.47 ± 0.34 µV, range: -0.08-1.92 µV).

The three-way ANOVA (condition: original / scrambled, frequency: oddball / base, electrode: PO8/ Oz) revealed significant main effects of condition (F(1,40) = 45.163, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.530), frequency (F(1,40) = 161.020, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.801) and electrode (F(1,40) = 5.761, p = 0.021, ηp2 = 0.126), as well as significant interactions between condition and frequency (F(1,40) = 46.333, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.537), and condition and electrode (F(1,40) = 24.949, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.384). Post-hoc pairwise comparisons demonstrated a significant difference between conditions at the oddball frequency (t(81) = 13.245, p < 0.001) but not at the base presentation frequency (t(81) = 0.907, p = 0.367). Further, for each electrode of interest, a significant difference was found in the log-amplitude between original and scrambled images (Oz: t(81) = 4.106, p < 0.001; PO8: t(81) = 4.416, p < 0.001) (Fig. 1b).

The multi-sensor cluster-based t-test comparing the neural activity at the oddball frequency between the original and scrambled condition demonstrated multiple clusters of electrodes with larger activity during the original condition. Precisely, a fronto-central clusters of interest was formed (F1, Fz, FC3, FC1, FCz, FC2, C1, Cz) as well as a occipital-temporal cluster (the latter corresponding to frequently observed distribution of responses7 consisting of left (PO7, PO3, P7, P9), middle (Oz, O2, O1, Iz) and right (PO8, PO10, P8, P6, P4) temporal-occipital electrodes (Fig. 1c).

(a) Frequency spectrum representation of the EEG response at the electrodes of interest (EOI). Neural response to the periodic presentation of original (i.e. intact images; EOI: electrode PO8) vs. scrambled (i.e. phase-scrambled version of the intact images, making it impossible to recognize what was shown originally while preserving the picture properties; EOI: electrode Oz) images (mean (bold) ± 95% within-subject confidence interval (dashed)). Topographic plots show global channel activity at 1.215 Hz (frequency of the oddball) and 6.075 Hz (base image presentation frequency). (b) Comparison of aggregated responses at the oddball and base presentation frequency. Sum of the neural responses at the oddball and base frequency and its first 4 harmonics (summed up separately into the “frequency of interest” for each condition and electrode). Differences between the magnitude of the response were assessed using paired t-tests (nsp>0.05, ****p < 0.0001). Jittered dots (grey) indicate individual data points; horizontal lines link the data points of the same participant for the compared condition. (c) Topographic illustration of the difference between the aggregated oddball response for intact and scrambled images. Aggregated responses consisted of the sum of the 1.215 Hz and its harmonics at 2.43 Hz, 3.645 Hz, 4.86 Hz and 7.29 Hz for each condition. Differences between conditions were assessed using a cluster-based multi-sensor analysis employing a paired t-test (p < 0.0001, right-tailed, 2000 permutations and set to 4 neighbors on average for each electrode).

Pain threshold

Pain thresholds were rated on average at 46.66 ± 2.01 °C (mean ± std dev), which corresponds to normative values for this age group26. Of the total sample, 20 participants had an above-average pain threshold.

Psychological traits

The psychological individual characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1.

Relationship between neural, behavioral and psychological factors

Pearson correlation analyses were conducted to explore the relationships between the recorded EEG signal amplitude at the presentation frequency of the oddball stimuli and other psychological and pain-related variables. Results indicated no significant correlation between amplitude and pain threshold (r = − 0.133 p = 0.408), or most psychological indices. However, a significant positive correlation was observed between amplitude and depression (r = 0.327, p = 0.037). This suggests a potential relationship between higher EEG amplitude and levels of depression. No other significant correlations were found between amplitude and measures of psychological distress (e.g., anxiety, perceived stress, emotion dysregulation) or coping strategies.

Significant negative correlations were observed between pain threshold and several subscales of emotional dysregulation (i.e., “Nonacceptance of Emotional Responses”, r=-0.385, p = 0.013; “Difficulties Engaging in Goal-Directed Behavior”, r=-0.421, p = 0.006; “Impulse control difficulties”, r=-0.426, p = 0.005; “Limited Access to Emotion Regulation Strategies”, r=-0.512, p < 0.001; “Lack of Emotional Clarity”, r=-0.347, p = 0.026), as well as overall emotional dysregulation (p < 0.01), indicating that people who tend to better regulate their emotions have also a higher pain threshold. Additionally, a significant negative correlation was observed between pain threshold and the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11) subscale “Motor Impulsivity” (r=-0.38, p = 0.014), as well as with the Brief-COPE subscale “Positive Reframing” (r = − 0.331, p = 0.035), suggesting that individuals with higher motor impulsivity and using this coping strategy had lower pain thresholds.

A linear regression analysis also revealed the predictive role of emotional dysregulation on pain threshold (B = − 0.051, SE = 0.013, β=−0.541, p < 0.001, adjusted R²=0.274, f²=0.41). Based on this information, to better investigate the relationship between depression and brain signal, the moderating role of pain threshold was examined, using depression as the independent variable and EEG amplitude as the dependent one.

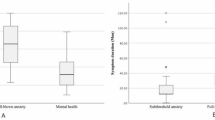

The overall model was significant (F(3, 37) = 6.79, p = 0.001, R² = 0.355, f2 = 0.55), as well as the interaction of depression and pain threshold (B = 0.118, SE = 0.032, t(37) = 3.740, p = 0.006, ΔR²=0.244, f²=0.38), indicating that the latter significantly moderate the way depression affect brain response to health images. Figure 2a shows the model between the three variables.

As shown in Fig. 2b, the effect of depression on EEG amplitude was stronger at higher levels of pain threshold. Thus, at lower (1SD – mean) pain thresholds the effect of depression on EEG amplitude was not significant (B=-0.005, SE = 0.083, t(37)=-0.062, p = 0.951), while the effect of depression on EEG amplitude was positive and significant both at medium pain threshold (B = 0.231, SE = 0.072, t(37) = 3.195, p = 0.003) and at higher (1SD + mean) pain threshold (B = 0.469, SE = 0.107, t(37) = 4.348, p = 0.0001).

Moderation models between depression, aggregated EEG amplitude and pain threshold. (a) Graphic illustration of the moderation model and the relationship between the variables. (b) Graphs show slopes of pain threshold predicting aggregated oddball EEG amplitudes at low, mean, and high levels of depression. When plotting the graphs, data automatically generated by the PROCESS analysis algorithm are used to classify low, mean, and high levels of continuous variables.

Pearson correlation showed a positive association between depression and oddball amplitude. In the moderation model, pain threshold significantly moderated this association (ΔR² = 0.244, p = 0.006). Simple-slope analyses indicated that the effect of depression on amplitude was non-significant at low pain thresholds, but positive and significant at medium (B = 0.231, p = 0.003) and high pain thresholds (B = 0.469, p = 0.0001). (see Fig. 2a). This shift in direction likely reflects the influence of the moderator, emphasizing that the association between depressive symptoms and neural response is not uniform across different levels of pain sensitivity. These results suggest that pain threshold moderates the relationship between depression and EEG amplitude. At higher pain threshold levels, depression is more strongly associated with increased EEG amplitude, while at lower pain threshold levels, the effect of depression on EEG amplitude is not significant.

Discussion

Notably, this study is the first to demonstrate that also the periodic presentation of health-related images can evoke distinguishable neural responses, even when these stimuli are more abstract and do not belong to a naturalistic category such as faces or tools. Specifically, the periodically presented health-related images (i.e. oddball) elicited a periodic neural response at the presentation frequency of this image category, which could be clearly differentiated from the response to images with random content. These findings support the hypothesis that FPVS can be used to “tag” neural responses to conceptual categories, broadening the applicability of this paradigm beyond its traditional domains. Additionally, we found that psychophysiological features, such as depression levels and individual pain threshold, are significantly related to the neural response to those oddball stimuli.

Generally, periodically presented stimuli (such as human faces) have the ability to elicit a periodic neural response, which can be easily assessed in the EEG frequency domain6,7,8,27,28,29,−30. As in previous studies using the FPVS paradigm, a consistent periodic response was found at the base image presentation frequency (~ 6 Hz), for both the presentation of original as well as scrambled images. Scalp topographies and channels with the largest activity at this frequency also matched these previous investigations, highlighting that the basic assumptions of the paradigm have been met. More importantly though, a periodic neural response was also found at the presentation frequency of the health-related oddball images (~ 1.2 Hz and harmonics), with neural activity being distributed similarly over the scalp as in the base response. Presenting scrambled images led to a much smaller, but nevertheless statistically significant periodic response at some oddball harmonics (but not its frequency of presentation). Thus, this demonstrates that an abstract image category as oddball stimulus can lead to a periodic neural response in the FPVS paradigm, even considering the relatively low rate of correct answers in the behavioral task. Previously, it had already been demonstrated that the FPVS paradigm elicits neural responses not only related to faces or tools but also related to semantic processing. This was achieved by presenting images which could be categorized into semantic categories of different specificity (e.g. natural vs. non-natural, animal vs. non-animal images)12 and natural vs. man-made images11. While the present results extend these findings, as the health-related images represent a more abstract image category than the semantic subgroups and support the use of FPVS to study conceptual processing beyond traditional domains, caution is needed in interpreting the specificity of response. Although the comparison with scrambled images addressed low-level visual confounds, we cannot attribute this response specifically to the “health” content of the images, as we did not include a control image category (e.g., tools or neutral objects) matched for affective valence and arousal, but unrelated to health (e.g., stimuli of violence or accidents). Indeed, FPVS studies demonstrate that emotional salience can modulate neural responses31,32, therefore, it is possible that the observed neural response reflects a general processing of emotionally salient or images, rather than a specific response to health-related content. In addition, other semantic dimensions that are not explicitly controlled (i.e., animacy and naturalness) may also have contributed to such neural discrimination. Also, the absence of formal validation for arousal and valence for neutral images is a further limitation in the interpretation of health-specific effects. Future studies could address this limitation by using standardized and validated sets such as the International Affective Picture System (IAPS;33), which provide standardized ratings for valence and arousal.

One possible explanation for the small but nevertheless present response during the scrambled oddball images would be that it was not only the recognition of the image category itself which led to the periodic response at the oddball frequency, but also some low-level qualities in this image category. Basic features such as contrast, and luminance were controlled by adjusting these characteristics across the entire image sample (including both health-related and non-health-related images) pre-experiment. Yet, other features such as animacy34 or spatial frequency and orientation11 (commonly assessed qualities in machine learning algorithms for visual features) could also elicit a neural response. Although luminance and contrast were standardized using the SHINE toolbox, other uncontrolled visual or semantic dimensions (e.g., spatial frequency orientation, animacy) might still have contributed to neural discrimination. Future studies should include non-health control categories matched for valence and arousal to more rigorously assess the health-specificity of neural responses. Nevertheless, as demonstrated by our cluster-based analysis, the responses to the intact oddball images were not only considerably larger than the ones elicited by the oddball using scrambled images, but also demonstrated a different distribution of the neural activity across the scalp, with a marked frontal activity which was not present in the scrambled condition (similar to Stothart, et al.12). As any of these low-level characteristics should be present in both the original as well as scrambled images, they are unlikely to be the main contributor to the observed response to the health-related images.

An exploratory objective of the study was to examine whether individual differences in psychological traits, such as anxiety, depression, emotional regulation, impulsivity or coping strategies, modulate neural responses to health-related images. Although in previous studies emotional dysregulation has been associated with attentional biases (e.g., Ciccarelli, et al.35;Harrison, et al.36), and health anxiety has been linked to stronger responses to illness-related stimuli4,37, in the current investigation a significant correlation was only observed between the neural responses to the oddball stimuli and one of the major psychological traits, namely depression. It should be noted that anxiety was assessed using a general trait measure, capturing dispositional anxiety rather than health-specific concern. While this approach allows us to examine whether broader trait-level vulnerabilities influence neural responses to health cues, the absence of a dedicated health anxiety scale also explains why anxiety did not emerge as a significant predictor. These findings should be interpreted with caution, as they represent exploratory and secondary analyses. Nevertheless, they are consistent with the hypothesis of an attentional bias toward emotionally salient stimuli in depressed individuals (see Suslow, et al.38 for a comprehensive review), and with evidence indicating amplified processing of signals of threat or vulnerability to illness39,40 in those individuals. However, a particularly novel element of this study concerns the role of pain threshold in moderating this relationship. Indeed, moderation analyses showed that the association between depression and neural response to health stimuli was significant only in participants with medium or high pain thresholds, whereas it was absent in subjects with low thresholds. Additionally, pain threshold was negatively predicted by emotional dysregulation trait. This finding not only align with prior research linking emotional dysregulation to heightened pain sensitivity41,42, but suggests that pain threshold, potentially indicative of broader affective and physiological functioning43, may influence, in specific psychological conditions, how an individual processes this kind of periodic information.

This analysis on pain threshold shed light on an interesting and potentially counterintuitive aspect. Indeed, emotional dysregulation represents a transdiagnostic factor commonly associated with depression44,45 and is in turn correlated to an increased experience of pain46. Nevertheless, our data show that the psychophysiological relationship between depression and neural response to health-related stimuli is only significant in participants with higher pain threshold (i.e., with an improved emotional regulation). This apparent inconsistency can be interpreted in light of neurocognitive models that consider the role of residual affective-sensory resources in modulating brain responses, such as the allostatic load model47,48,49 and related research on chronic stress and pain interactions (e.g., 50,51,52) which posit that the ability to process emotionally salient information depends on available affective-sensory resources. These models propose that the ability to allocate neural resources to emotionally salient stimuli depend on residual effective-sensory capacity. In the case of our study, the individual’s affective system may need to maintain sufficient responsiveness to allow depression to amplify neural activity in response to emotionally relevant stimuli, such as the health-related images. Accordingly, individuals with augmented levels of depression and with higher pain threshold (i.e., potentially more emotionally regulated) may have enough neural resources to actively process the stimulus and have an increased EEG response to that. On the contrary, individuals with augmented levels of depression but lower pain threshold (i.e., potentially less emotionally regulated) may have a blunted neural response as a response of combined affective vulnerability and sensory overload. Although these findings converge with epidemiological evidence showing a positive relationship between pain severity and allostatic load (e.g.,53,54), as well as with model describing how chronic stress affects pain and HPA-axis regulation55, this interpretation remains speculative and should be approached with caution. Furthermore, while the moderation analysis was statistically robust, we cannot rule out a priori the influence of potential confounding factors (e.g., age, sex, medical status, medication use) on pain sensitivity and affective processing, which were not considered in our analysis due to the small sample size and lack of variety in these variables.

These findings have several implications for the understanding of neural processing of health-related stimuli. First, they demonstrate the feasibility of using FPVS to explore neural responses to abstract and potentially emotionally salient categories. Second, while preliminary, the psychophysiological correlates suggest that individual factors might modulate this implicit neural response to emotionally meaningful visual cues. Yet, one of the main limitations of the present study is the inability to conclusively determine whether the observed neural activation is specifically driven by the health-related content of the stimuli. Further research is needed to corroborate these hypotheses and to establish the specificity of neural responses to health-related stimuli, for example by directly contrasting them with other categories of stimuli in future studies, including matched control categories to disentangle the influence of health-specific relevance from more general affective or semantic properties.

In summary, this study expands the utility of the FPVS paradigm to abstract categories such as health-related stimuli and highlights the need to consider psychological well-being when investigating individual differences in the processing of health-related cues such as illness representations or medical imagery. Future research should continue to refine the methodological approaches used to investigate the complex interplay between neural, psychological, and physiological processes in health-related contexts.

Methods

Participants

A sample size of 30 participants was estimated using the software G*Power to be necessary for a repeated- measures ANOVA with two within-factors (condition: ordinary/scrambled; electrode: PO8/OZ) to reach a power of 0.90 with an effect size of 0.25 and with the statistical significance set to 0.05. A total of 44 participants were recruited for this experimental study. For reasons of lack of compliancy with the research directions (n = 2) and technical problems (n = 1), only 41 participants were considered for statistical analysis (age (mean ± std. dev.): 25.17 ± 6.3, 32 females). With n = 41, the study is well-powered for medium-to-large within-subject effects at the oddball frequency; smaller brain–trait associations warrant replication in larger samples.

Recruitment was carried out on an established website through the distribution of a flyer, which described the study as an investigation into how individual psychophysiological characteristics influence brain signals. The flyer specified that participation in the study would require approximately 1 h and 45 min, and participants would be compensated 20 euros for their participation.

After scheduling and signing an informed consent form, participants were screened for inclusion criteria (aged 18–65, in good health). Those meeting the criteria were contacted by the experimenter to be enrolled in the study.

Procedure

Prior to their laboratory session, participants received a link from the experimenter, inviting them to read and sign the informed consent. Then they were invited to complete a series of questions, including assessments of sociodemographic information (e.g., gender, age, occupation) and a set of validated psychological questionnaires for individual characteristics (depression, anxiety, stress, impulsivity trait, emotion regulation strategies, coping strategies).

Upon arrival at the laboratory on the scheduled day and time, participants underwent two experimental procedures. First, individual pain thresholds were measured using thermal cutaneous stimulations. Next, participants completed the FPVS task, during which EEG data were collected.

The local Research Ethics Committee approved all experimental procedures (Commission d’Ethique hospitalo-facultaire Saint-Luc UCLouvain, 2024/14FEV/074 – HSP) and all procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent before participating and were debriefed after the completion of their laboratory session.

Questionnaires for the assessment of psychological characteristics

A battery of validated questionnaires was employed to assess specific individual characteristics potentially related to the participant’s pain threshold and neural response to the FPVS task. The following questionnaires were included in the battery: (i) Beck Depression Inventory (BDI56: a self-report questionnaire widely used to assess levels of depressive traits in the general population, composed by 21 questions and each question is scored on a scale value of 0 to 3; (ii) State-Trait Anxiety Inventory – Y2 (STAI-Y257;): a commonly used self-report scale to assess trait anxiety levels, composed by 20 items to answer using a 4-point Likert scale; (iii) Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS44: a self-report scale designed to assess difficulties in regulating emotions, not only about the control of emotional arousal but also the awareness, comprehension, and acceptance of emotions. It is composed of 36 items and divided into 6 subscales (Nonacceptance of Emotional Responses, Difficulties Engaging in Goal-Directed Behavior, Impulse Control Difficulties, Lack of Emotional Awareness, Limited Access to Emotion Regulation Strategies, Lack of Emotional Clarity). Answers are provided on a 5-point Likert scale; (iv) Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-1158): a 30-item self-report scale assessing three types of impulsivities (attentional, motor, non-planning) and a general score of impulsivity trait. Answers are provided using a 4-point Likert scale. (v) Behavioral Inhibition System and Behavioral Activation System Scales (BIS/BAS59): two self-report scales assessing individual differences in the sensitivity of motivational systems, one related to avoidant behaviors and one related to approaching behaviors, composed by a totality of 20 items answered by the use of a 4-point Likert scale; (vi) Brief Coping Orientation to Problem Experiences Inventory (Brief-COPE60: the brief version of a self-report questionnaire measuring effective and ineffective ways to cope with a stressful life situation (Active Coping, Planning, Instrumental Support, Using Emotional Support, Venting, Behavioral Disengagement, Self-Distraction, Self-Blame, Positive Reframing, Humor, Denial, Acceptance, Religion, Substance Use), grouped into three macro-categories (Emotion-Focused Coping, Problem-Focused Coping, Dysfunctional Coping), composed of 28 items and answers are provided by using a 4-point Likert Scale; (vii) Perceived Stress Scale (PSS61: a 10-items self-report questionnaire widely used to assess individual’s perception of stress in daily life with a 5-point Likert scale used to provide answers.

Being the sample of the present study composed by French speakers, validated French-language versions of the questionnaires described were administered (BDI62; STAI63; DERS64; BIS-1165; BIS/BAS66; Brief—COPE67.

Pain threshold assessment

The individual pain threshold was measured using thermal stimulation and the method of limits26,68,69. Thermal stimuli were delivered to the volar forearm of the subject before the start of the visual task using a contact-heat thermode made of 15 micro-Peltier elements (stimulation surface: 1.2 cm2) (TCS, QST.Lab, Strasbourg, France). For each subject, the stimulation temperature was set to skin temperature (~ 32 °C) and subsequently the temperature was raised by 1 °C/s until the subject perceived that the stimulation started to be painful and pressed a response button. This procedure was repeated 3 times (each time displacing the thermode to avoid habituation / sensitization), and the average of those trials was considered as the subject’s pain threshold. For safety reasons, the stimulation would automatically stop at 50 °C, no matter whether the button was pressed or not. 50 °C would then be considered as the pain threshold for that trial. To ensure that each participant understood when to press the button, standardized instructions were used, defining “pain” as a burning or pricking sensation.

Fast periodic visual stimulation task

FPVS is typically employed to capture periodic EEG responses elicited by fast visual stimuli delivered at a specific frequency7,8,30,70,71. The paradigm consists of rapidly presenting “neutral” images at a frequency F, with every nth image (frequency = F/n) representing the “salient” image (i.e., the oddball) which is different from the neutral images and adhere to an image category in line with the study’s hypothesis (e.g. face individuation). This technique underlies the hypothesis that a periodic stimulation elicits a periodic neural response at the frequency of the stimulation (and its harmonics), allowing the precise “tagging” of the neural response in the frequency domain5. Hence, neural responses to the neutral and oddball images can easily be differentiated7.

In the current investigation, the oddballs were images representing health-related objects and features (e.g., syringes, hospital settings, pills, masks, white coats), while the neutral images could be any object (e.g. house, flower, cooking utensil, furniture, ….). The selected health-related stimuli were rated in their arousal by an independent sample of 31 participants, with the aim to select health-related images that are similarly arousing. Participants were presented with a series of images related to the medical and health domain and were instructed to evaluate each image based on its arousing quality, defined as the degree to which the image elicited a feeling of activation, regardless of its emotional valence, consistent with the dimensional framework of affective responses proposed by Bradley and Lang72. Responses were given using a visual analog scale (VAS) ranging from 1 (not at all) to 10 (totally). Neutral images were not subjected to a formal validation procedure in terms of arousal or valence. Instead, their selection followed a strategy aimed at maximizing comparability with the visual and structural comparability of the health-related ones (e.g., a hospital bed-domestic bed; vertically oriented syringe-vertically oriented key). This approach was intended to balance low- and mid-level visual characteristics e.g., shape, orientation, spatial layout), while minimizing potential semantic overlap with the health domain. At the end, 75 health-related and 302 non-health-related images were selected.

The images were then equalized for size (200 × 200 pixels), color (gray scale), contrast and pixel luminance across neutral and oddball images, to avoid confounding the results with differences in low-level image features. The MATLAB toolbox “SHINEtoolbox”73 was used for this process. Additionally, both oddball and neutral images were phase-scrambled, to create the images for the control condition. Although the neutral images were not formally validated in terms of arousal or valence, all stimuli, along with the MATLAB presentation scripts are publicly available in the OSF repository associated with this investigation (https://doi.org/10.17605/osf.io/9423j), to enable replication and future validation efforts.

FPVS was performed using a custom MATLAB script (MATLAB 7, The MathWorks Inc, Natick, MA) and the images were shown to the participant on a Philips LCD 190S6 monitor (1280 × 1024 pixels, panel size: 19”/48 cm). The refresh rate was set to ~ 50 Hz and a resolution of 1024 × 768 was used. Participants were seated ~ 58 cm away from the screen. The images were presented against a uniform gray background, from which it emerged with increasing contrast after a 2–5 sec presentation of a fixation point (Fig. 3). Then, images were presented for about 1 min at a rate of 6.075 Hz with every 5th image being a health-related image (rate of presentation 1.215 Hz) introduced every fifth stimulus (i.e., ~ 6 Hz/5 = 1.2 Hz). Within a condition (i.e. neutral / oddball), the sequence of the images was randomized via a MATLAB script for each participant. In total, 36 trials (6 blocks of 6 trials each) were applied, and the order of conditions (scrambled vs. original) was counterbalanced across participants. Each trial was composed of a stimulation which lasts 60 s and was flanked by 2 s of fade-in and fade-out at the beginning and the end of the sequence, respectively. During the fade-in, the contrast modulation depth of the periodic stimulation progressively increased from 0% to 100% (full contrast), while the opposite manipulation was applied during the fadeout. This fading is aimed at reducing blinks and abrupt eye movements due to the sudden appearance or disappearance of flickering stimuli. Full contrast is reached at 85 ms and then decreased at the same rate. A rate of ~ 6 Hz was used because this frequency leads to a large response over occipitotemporal regions and falls in an area of the EEG spectrum (theta band) where the noise level is low (i.e., above the EEG delta band but below the alpha band of 8–12 Hz)70. See Fig. 3 for a graphic representation of the task.

During the presentation of the images, participants were asked to focus their attention on a colored dot in the middle of the screen, and to count the number of times it would change to the color red within one trial (i.e. ~1 min of image presentation) [similar to other studies, e.g. De Keyser, et al.8; Rossion, et al.70] This was done to ensure the participants’ focus on the presented images. Participants reported the number of counted color changes verbally to the experimenter after seeing a prompt being displayed on the screen. The time in between trials was self-paced by the participants and depended on the time they took to answer the task-related question.

EEG recording

The neural response to the FPVS paradigm was recorded through scalp EEG, using an elastic electrode cap with 64 active, pre-amplified Ag-AgCl electrodes (BioSemi, Netherlands), arranged according to the international 10–10 system. The direct-current offset was kept below 30 µV during the electrode placement and subsequent experimental session. One participant’s data was acquired at 256 Hz instead of 1024 Hz and was subsequently removed from the analysis.

EEG preprocessing

As the individual trials had slightly different durations due to the randomization of the fade-in and fade-out of the images, a custom MATLAB script was used to trim each trial to the exact duration of image presentation (cropped to 57344 bins / trial, equals ~ 56 s). The same script was used to label the randomized trials for the conditions (scrambled / original). The data were then imported into Letswave7, an open-source MATLAB toolbox (www.letswave.cn). The EEG signal was filtered using a 4th order Butterworth filter (0.1–100 Hz). Then, a 50 Hz notch filter (width: 2 Hz) was applied and the data was re-referenced to the average of all electrodes. For each condition, the trials were averaged, and a discrete Fourier Transform (FFT)74 was applied to transform the data into the frequency domain (spectrum ranging from 0 to 512 Hz, frequency resolution: ~ 0.018 Hz). Then, the signal was baseline corrected to remove residual noise, by subtracting at each electrode and at each frequency bin the average amplitude of the signal measured at the 10 neighboring frequency bins.

Finally, the baseline-subtracted group- and channel-averaged signal was z-scored by calculating the difference between the amplitude at a given frequency bin and the mean amplitude of the 20 surrounding (i.e. ± 10 ) bins divided by the standard deviation of these 20 surrounding bins70. This pooled data was then used to define the number of harmonics that are statistically different from zero (i.e. harmonics with z > 1.64, one-sided, signal > noise) in consecutive order (Table 2), which were then aggregated from the baseline-subtracted data75. This means that aggregation stopped at the first non-significant harmonic. The same steps were applied to aggregate responses at the base response frequency and its harmonics. The electrodes of interest for the original and scrambled condition were consecutively defined based on the electrode exhibiting the largest group-level response (i.e. amplitude) across these aggregated base stimulation frequencies.

Statistical analysis

To detect electrode activity clusters in response to the health-related visual stimuli and compare the distribution of the neural activity of the aggregated responses between the original and scrambled condition, a multi-sensor cluster-based analysis12 employing a paired t-test (set to an alpha of 0.0001 with 2000 permutations, the sensor connection threshold was set so each electrode has four neighbors on average) was used.

The remaining statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 28 and R Studio (v4.3.1, R Core Team (2023)). To assess differences in the aggregated neural responses to oddball and base frequency stimuli in the different conditions (original vs. scrambled images) and across different electrodes (PO8 vs. Oz), a repeated-measured ANOVA was used. A log-transform was applied to all EEG data to correct right-skewedness and conform them to the assumption of normality76 (for the purpose of illustrating the data accurately and keep the data comparable, all figures display the original µV amplitudes of the EEG data). Significant results were further assessed post-hoc using pairwise t-tests. The relationship between pain thresholds, neural responses and psychological traits was assessed using correlational analyses, regression analyses and moderation analyses (PROCESS analysis algorithm77. Behavioral differences between the conditions were examined through a repeated-measure ANOVA. For all statistical analysis, the significance threshold was set at p < 0.05.

Data availability

The raw data (EEG), and individual data for pain thresholds and trait characteristics as well as supporting material (e.g. images used for the FPVS paradigm, Letswave preprocessing pipelines) are openly available on OSF (https:/osf.io/9423j).

References

Kouider, S. & Dehaene, S. Levels of processing during non-conscious perception: a critical review of visual masking. Philosophical Trans. Royal Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 362, 857–875. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2007.2093 (2007).

Ferguson, E. A taxometric analysis of health anxiety. Psychol. Med. 39, 277–285. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291708003322 (2009).

Kaur, A., Butow, P. N. & Sharpe, L. Health threat increases attentional bias for negative stimuli. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry. 44, 469–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2013.06.003 (2013).

Sagliano, L. et al. Health comes first: action tendencies to Health-Related stimuli in people with Health-Anxiety as revealed by an emotional Go/No-Go task. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 18, 9104 (2021).

Regan, D. Human brain electrophysiology. Evoked potentials and evoked magnetic fields in science and medicine (1989).

Norcia, A. M., Appelbaum, L. G., Ales, J. M., Cottereau, B. R. & Rossion, B. The steady-state visual evoked potential in vision research: A review. J. Vis. 15, 4–4. https://doi.org/10.1167/15.6.4 (2015).

Rossion, B., Retter, T. L. & Liu-Shuang, J. Understanding human individuation of unfamiliar faces with oddball fast periodic visual stimulation and electroencephalography. Eur. J. Neurosci. 52, 4283–4344. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejn.14865 (2020).

De Keyser, R., Mouraux, A., Quek, G. L., Torta, D. M. & Legrain, V. Fast periodic visual stimulation to study tool-selective processing in the human brain. Exp. Brain Res. 236, 2751–2763. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-018-5331-2 (2018).

Lochy, A., Van Belle, G. & Rossion, B. A robust index of lexical representation in the left occipito-temporal cortex as evidenced by EEG responses to fast periodic visual stimulation. Neuropsychologia 66, 18–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2014.11.007 (2015).

Lochy, A., Van Reybroeck, M. & Rossion, B. Left cortical specialization for visual letter strings predicts rudimentary knowledge of letter-sound association in preschoolers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113, 8544–8549. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1520366113 (2016).

Milton, A. et al. Fast periodic visual stimulation indexes preserved semantic memory in healthy ageing. Sci. Rep. 10, 13159. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-69929-5 (2020).

Stothart, G., Quadflieg, S. & Milton, A. A fast and implicit measure of semantic categorisation using steady state visual evoked potentials. Neuropsychologia 102, 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2017.05.025 (2017).

Garbóczy, S. et al. Health anxiety, perceived stress, and coping styles in the shadow of the COVID-19. BMC Psychol. 9, 53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-021-00560-3 (2021).

Gross, J. J. Emotion regulation: taking stock and moving forward. Emotion 13, 359–365. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032135 (2013).

Tamir, M. & Robinson, M. D. Knowing good from bad: the paradox of Neuroticism, negative Affect, and evaluative processing. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 87, 913–925. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.6.913 (2004).

Ochsner, K. N., Silvers, J. A. & Buhle, J. T. Functional imaging studies of emotion regulation: a synthetic review and evolving model of the cognitive control of emotion. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1251, E1–E24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06751.x (2012).

Bar-Haim, Y., Lamy, D., Pergamin, L., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J. & van Ijzendoorn, M. H. Threat-related attentional bias in anxious and nonanxious individuals: A meta-analytic study. Psychol. Bull. 133, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.1 (2007).

Gehrt, T. B. et al. Resting-state connectivity and neural response to emotional images in patients with severe health anxiety: an fMRI study. J. Affect. Disord. 324, 370–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.12.138 (2023).

Crombez, G., Van Ryckeghem, D. M. L., Eccleston, C. & Van Damme, S. Attentional bias to pain-related information: A meta-analysis. PAIN 154, 497–510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2012.11.013 (2013).

Hadjistavropoulos, H. D., Craig, K. D. & Hadjistavropoulos, T. Cognitive and behavioral responses to illness information: the role of health anxiety. Behav. Res. Ther. 36, 149–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(98)00014-X (1998).

Asmundson, G. J. G. & Taylor, S. Role of anxiety sensitivity in pain-related fear and avoidance. J. Behav. Med. 19, 577–586. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01904905 (1996).

Gundes, B., Ozkaya, Y., Demircan, T., Adnan, Y. & Eliacik, K. Health anxiety and somatosensory amplification in adolescents with unexplained chest pain: A comparative study. Australian J. Gen. Pract. 54, 117–121 (2025).

Chapman, S. & Martin, M. Attention to pain words in irritable bowel syndrome: increased orienting and speeded engagement. Br. J. Health. Psychol. 16, 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1348/135910710X505887 (2011).

Heathcote, L. C. et al. The relationship between adolescents’ pain catastrophizing and attention bias to pain faces is moderated by attention control. PAIN 156, 1334–1341. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000174 (2015).

Wiech, K. & Tracey, I. Pain, decisions, and actions: a motivational perspective. Front. Neurosci. 7 https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2013.00046 (2013).

Yarnitsky, D., Sprecher, E., Zaslansky, R. & Hemli, J. A. Heat pain thresholds: normative data and repeatability. Pain 60, 329–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3959(94)00132-X (1995).

Barbero, F. M., Talwar, S., Calce, R. P., Rossion, B. & Collignon, O. Intermodulation frequencies reveal common neural assemblies integrating facial and vocal fearful expressions. Cortex 184, 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2024.12.008 (2025).

De Rosa, M., Ktori, M., Vidal, Y., Bottini, R. & Crepaldi, D. Frequency-based neural discrimination in fast periodic visual stimulation. Cortex 148, 193–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2022.01.005 (2022).

Su, Y. et al. Increased sensitivity to social hierarchy during social competition versus cooperation. Soc. Cognit. Affect. Neurosci. 19 https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsae060 (2024).

Vettori, S. et al. Reduced neural sensitivity to rapid individual face discrimination in autism spectrum disorder. NeuroImage: Clin. 21, 101613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2018.101613 (2019). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/

Dzhelyova, M., Jacques, C. & Rossion, B. At a single glance: fast periodic visual stimulation uncovers the Spatio-Temporal dynamics of brief facial expression changes in the human brain. Cereb. Cortex. 27, 4106–4123. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhw223 (2016).

Naumann, S., Bayer, M. & Dziobek, I. Enhanced neural sensitivity to brief changes of happy over angry facial expressions in preschoolers: A fast periodic visual stimulation study. Psychophysiology 62, e14725. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.14725 (2025).

Lang, P. J., Bradley, M. M. & Cuthbert, B. N. International Affective Picture System (IAPS): Affective Ratings of Pictures and Instruction Manual (NIMH, Center for the Study of Emotion & Attention Gainesville, 2005).

New, J., Cosmides, L. & Tooby, J. Category-specific attention for animals reflects ancestral priorities, not expertise. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104, 16598–16603 https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0703913104 (2007).

Ciccarelli, M., Nigro, G., Griffiths, M. D., Cosenza, M. & D’Olimpio, F. Attentional bias in non-problem gamblers, problem gamblers, and abstinent pathological gamblers: an experimental study. J. Affect. Disord. 206, 9–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.07.017 (2016).

Harrison, A., Sullivan, S., Tchanturia, K. & Treasure, J. Emotional functioning in eating disorders: attentional bias, emotion recognition and emotion regulation. Psychol. Med. 40, 1887–1897. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291710000036 (2010).

Cannito, L. et al. Health anxiety and attentional bias toward virus-related stimuli during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci. Rep. 10, 16476. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-73599-8 (2020).

Suslow, T., Hußlack, A., Kersting, A. & Bodenschatz, C. M. Attentional biases to emotional information in clinical depression: A systematic and meta-analytic review of eye tracking findings. J. Affect. Disord. 274, 632–642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.140 (2020).

Li, S. & Li, X. The relationship between attentional Bias, anxiety Sensitivity, and depression and anxiety symptoms: evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Front. Public. Health. 10–2022 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.832819 (2022).

Liu, X. et al. Attentional bias toward threatening stimuli in major depressive disorder: A free-viewing eye-tracking study. J. Affect. Disord. 378, 352–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2025.02.039 (2025).

Zaorska, J. et al. Childhood Trauma, emotion Regulation, and pain in individuals with alcohol use disorder. Front. Psychiatr. 11 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.554150 (2020).

Bruton, A. M. et al. Pain sensitivity and perceptual sensitivity are associated with severity of emotional dysregulation in children with ADHD: a cross-sectional analysis using the temperament in middle childhood questionnaire. Disabil. Rehabil. 45, 848–856. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2022.2043946 (2023).

Lumley, M. A. et al. Pain and emotion: a biopsychosocial review of recent research. J. Clin. Psychol. 67, 942–968. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20816 (2011).

Gratz, K. L. & Roemer, L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor Structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 26, 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94 (2004).

Aldao, A., Nolen-Hoeksema, S. & Schweizer, S. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 30, 217–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004 (2010). https://doi.org/https://doi.

Hampton, A. J. D., Hadjistavropoulos, T., Gagnon, M. M., Williams, J. & Clark, D. The effects of emotion regulation strategies on the pain experience: a structured laboratory investigation. PAIN 156, 868–879. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000126 (2015).

McEwen, B. S. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. N. Engl. J. Med. 338, 171–179. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199801153380307 (1998).

McEwen, B. S. & Gianaros, P. J. Stress- and Allostasis-Induced brain plasticity. Annu. Rev. Med. 62, 431–445. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-med-052209-100430 (2011). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/

McEwen, B. S. Allostasis and allostatic load: implications for neuropsychopharmacology. Neuropsychopharmacology 22, 108–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00129-3 (2000).

Borsook, D., Maleki, N., Becerra, L. & McEwen, B. Understanding migraine through the lens of maladaptive stress responses: A model disease of allostatic load. Neuron 73, 219–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2012.01.001 (2012).

Woda, A., Picard, P. & Dutheil, F. Dysfunctional stress responses in chronic pain. Psychoneuroendocrinology 71, 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.05.017 (2016). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/

Rabey, M. & Moloney, N. I don’t know why i’ve got this Pain! Allostasis as a possible explanatory model. Phys. Ther. 102 https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzac017 (2022).

Sibille, K. T., McBeth, J., Smith, D. & Wilkie, R. Allostatic load and pain severity in older adults: results from the english longitudinal study of ageing. Exp. Gerontol. 88, 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2016.12.013 (2017).

Nelson, S., Bento, S. & Enlow, M. B. Biomarkers of allostatic load as correlates of impairment in youth with chronic pain: an initial investigation. Children 8, 709 (2021).

Lunde, C. E. & Sieberg, C. B. Walking the tightrope: A proposed model of chronic pain and stress. Front. NeuroSci. 14–2020 https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2020.00270 (2020).

BECK, A. T., MENDELSON, W. A. R. D. C. H., MOCK, M., ERBAUGH & J. & J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 4, 561–571. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004 (1961).

Spielberger, C., Gorsuch, R., Suchene, R., Vagg, P. & Jacobs, G. Manual for the state-anxiety (form Y): self evaluation questionnaire. Palo Alto (CA) (1983).

Patton, J. H., Stanford, M. S. & Barratt, E. S. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J. Clin. Psychol. 51, 768–774. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(199511)51:6%3C768::AID-JCLP2270510607%3E3.0.CO;2-1 (1995). https://doi.org/https://

Carver, C. S. & White, T. L. Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: the BIS/BAS scales. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 67, 319–333. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.2.319 (1994).

Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F. & Weintraub, J. K. Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 56, 267–283. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.56.2.267 (1989).

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T. & Mermelstein, R. A. Global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 24, 385–396. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136404 (1983).

Alsaleh, M. & Lebreuilly, R. Validation of the French translation of a short questionnaire Beck depression (BDI-FS-Fr). Ann. Med. Psychol. 175, 608–616 (2017).

Bruchon-Schweitzer, M. & Paulhan, I. Adaptation française de l’Inventaire d’Anxiété Trait-état. Forme Y (STAI-Y). Les Éditions du centre de psychologie appliquée, Paris (1993).

Dan-Glauser, E. S. & Scherer, K. R. The difficulties in emotion regulation scale (DERS). Swiss J. Psychol. 72, 5–11. https://doi.org/10.1024/1421-0185/a000093 (2013).

Baylé, F. J. et al. Structure factorielle de La traduction française de l’échelle d’impulsivité de Barratt (BIS-10). Can. J. Psychiatry. 45, 156–165. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370004500206 (2000).

Caci, H., Deschaux, O. & Baylé, F. J. Psychometric properties of the French versions of the BIS/BAS scales and the SPSRQ. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 42, 987–998. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.09.008 (2007).

Muller, L. & Spitz, E. Évaluation multidimensionnelle du coping: validation du brief COPE Sur Une population française. L’encéphale 29, 507–518 (2003).

Yarnitsky, D., Simone, D. A., Dotson, R. M., Cline, M. A. & Ochoa, J. L. Single C nociceptor responses and psychophysical parameters of evoked pain: effect of rate of rise of heat stimuli in humans. J. Physiol. 450, 581–592. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019144 (1992).

Reulen, J. P. H., Lansbergen, M. D. I., Verstraete, E. & Spaans, F. Comparison of thermal threshold tests to assess small nerve fiber function: limits vs. levels. Clin. Neurophysiol. 114, 556–563. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1388-2457(02)00405-4 (2003).

Rossion, B., Torfs, K., Jacques, C. & Liu-Shuang, J. Fast periodic presentation of natural images reveals a robust face-selective electrophysiological response in the human brain. J. Vis. 15, 18–18. https://doi.org/10.1167/15.1.18 (2015).

Xu, B., Liu-Shuang, J., Rossion, B. & Tanaka, J. Individual differences in face identity processing with fast periodic visual stimulation. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 29, 1368–1377. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn_a_01126 (2017).

Bradley, M. M. & Lang, P. J. Measuring emotion: the self-assessment manikin and the semantic differential. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry. 25, 49–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7916(94)90063-9 (1994).

Willenbockel, V. et al. Controlling low-level image properties: the SHINE toolbox. Behav. Res. Methods. 42, 671–684. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.42.3.671 (2010).

Frigo, M. & Johnson, S. G. Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing, ICASSP ‘98 (Cat. No.98CH36181). vol.1383, 1381–1384 (1998).

Retter, T. L. & Rossion, B. Uncovering the neural magnitude and spatio-temporal dynamics of natural image categorization in a fast visual stream. Neuropsychologia 91, 9–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2016.07.028 (2016).

Bland, J. M. & Altman, D. G. Statistics notes: transforming data. BMJ 312, 770. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.312.7033.770 (1996).

Hayes, A. F. Introduction To mediation, moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A regression-based Approach (Guilford, 2017).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the CATL team and especially Fanny Fievez for their help in setting up the experiment and Valéry Goffaux for valuable advice. Additionally, we would like to thank the NOCIONS lab for the valuable discussions.

Funding

PC was supported by a doctoral fellowship of the National Operation Program (PON) Research and Innovation 2014–2020 (CCI. 2014IT16M2OP005), ESF REACT-EU resources, Action IV.4 “Doctorates and research contracts on themes of innovation” and Action IV.5 “Doctorates on Green themes.” CUP code J35F21003350006. CL was supported by a FRIA doctoral grant by the Belgian Fund for Scientific Research (F.R.S.–FNRS, grant: 5118622). This study was further supported by a Mandat d’Impulsion Scientifique (MIS) - F.N.R.S grant awarded to GL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: PC, GL; Methodology: PC, CL, GL; Investigation: PC; Validation : CL; Formal analysis: CL (EEG), PC (psychological traits); Data Curation: CL; Visualization: PC, CL; Supervision: MM, GL; Funding acquisition: GL; Writing—Original Draft: PC, CL; Writing—Review & Editing: PC, CL, MM, GL.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Castellano, P., Leu, C., Mazzetti, M. et al. Using fast periodic visual stimulation to investigate the processing of health-related images in the human brain. Sci Rep 15, 45597 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29515-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29515-z