Abstract

To investigate the mechanistic pathways and intrinsic stability of biochar functional groups under controlled oxidation, a novel approach integrating Fourier transform infrared two-dimensional correlation spectroscopy (2D-COS) and moving window 2D-COS (MW2D-COS) analysis was employed. Wheat straw (WS) and dairy manure (DM) were pyrolyzed at 500/700°C (WSB500, DMB500, WSB700, DMB700) and oxidized with 5%-30% H2O2. Ultimate/proximate analyses, dissolved organic carbon (DOC) measurements, and 2D-COS/MW2D-COS analyses were applied to track compositional and functional group changes. Results showed that pyrolysis temperature was the primary factor influencing oxidation-induced changes. 2D-COS analysis revealed the lower stability of WSB500 and DMB500, attributed to their functional groups’ higher oxidation susceptibility. The evolution sequences of carbon-related functional groups were identified as: C-O → CH2/C=C/aromatic C=C → C=O → C-OH (for WSB500), C-O → aromatic C=C → CH2/C=C → C-OH/C=O (for DMB500), C=O → =C-H/aromatic C-H (for WSB700), and C=O → aromatic C-H/carbonate → =C-H (for DMB700). MW2D-COS analysis confirmed aromatic C=C/CH₂/C=C degradation and C=O formation in WSB500 and DMB500 during oxidation, aligning with significant alterations in C, O, fixed carbon, DOC, and atomic ratios (p < 0.01). WSB700 demonstrated superior oxidation resistance. These findings provide a mechanistic basis for predicting biochar’s long-term carbon sequestration potential and guide the selection of optimal pyrolysis conditions for specific environmental applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Biochar is a carbon-rich material produced through the pyrolysis of agricultural straw, wood, and other biomass materials under oxygen-limited conditions at high temperatures. It has demonstrated significant potential in soil improvement, pollutant treatment, carbon sequestration, and greenhouse gas reduction1,2,3. With anthropogenic activities driving a 0.9–1.3 °C global average temperature rise (2010–2019 vs. pre-industrial levels)4, biochar and its application to farmland have garnered widespread attention as an effective strategy for mitigating climate change5.

The long-term effectiveness of biochar in carbon sequestration relies on its stability-its resistance to decomposition/oxidation and structural integrity6. Once applied to soil, biochar is susceptible to degradation by biotic factors (e.g., plants and microorganisms) and abiotic factors (e.g., oxygen, ozone, and environmental oxidants like H2O2 and HNO3)7,8. Among these, the oxidative degradation of biochar has attracted increasing attention due to its significant impact on functional groups, the release of dissolved organic carbon (DOC), and alterations to carbon structure9,10,11.These changes influence the distribution of carbon forms, such as total C, fixed carbon (FC), and DOC, thereby directly affecting biochar’s carbon stability12 and its adsorption capacity of heavy metal in the soil environment13,14.

Traditional wet chemical analyses are widely used to characterize changes in biochar carbon forms15,16. Techniques such as ultimate and proximate analyses are used to determine variations of C and FC contents17,18. The calculation of H/C and O/C ratios are used to reflect changes in carbon structure of biochar19,20. The DOC content is obtained using water extraction21. In parallel, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) technology provides molecular-level insights into carbon forms in biochar by identifying changes in functional groups and aromatic ring structures through chemical bond vibrations and rotations, which offered rapid and non-invasive analysis with high sensitivity and resolution11,22. However, one-dimensional FTIR spectra faces challenges in complex systems due to some issues such as peak overlapping, complicating spectral interpretation.

Two-dimensional correlation spectroscopy (2D-COS) is an advanced technique that enhances spectral resolution and analytical capability by correlating dynamic spectra response under controlled perturbations (e.g., temperature, concentration, and pressure changes)23,24. Compared with one-dimensional FTIR analysis, 2D-COS significantly improves the identification of functional group variations. Moving window 2D-COS (MW2D-COS), an important extension of 2D-COS, divides spectral data into several submatrices (which were called windows) based on perturbation variables and then performs 2D-COS analysis on each window separately. This method effectively resolved complex spectral overlapping, revealing the dynamic changes in spectral signals as perturbations changes25,26. Recent studies have successfully applied 2D-COS and MW2D-COS to identify the changes in functional groups during biochar pyrolysis and adsorption processes26,27,28. Despite their potential, their application to clarify functional groups evolution during oxidation remains limited.

The oxidation resistance of biochar is primarily influenced by both pyrolysis temperature and feedstock type20,29,30. Elevated pyrolysis temperatures improve oxidation resistance by increasing aromaticity and graphitization29,30, while feedstock-inherent minerals such as Si can further enhance oxidative resistance31,32. Furthermore, researchers have used chemical oxidants such as KMnO4, K2Cr2O7, and H2O2 to simulate biochar oxidation in natural environment33,34. Compared with other chemical oxidants, H2O2 is widely employed for biochar oxidation due to its high applicability and minimal additional impurities interference35,36. Although accelerated H2O2 oxidation in the laboratory cannot fully replicate the long-term natural aging processes, which involve complex interactions between biotic and abiotic factors37,38, this approach can effectively trigger specific aging pathways (such as microbial metabolites oxidation)39. By characterizing the ensuing changes in physio- chemical properties under controlled conditions, key mechanisms underlying natural aging can be elucidated. Previous studies have utilized varying H2O2 concentrations or intensities to simulate different oxidative stages over short periods, primarily tracking changes in C and FC contents to assess biochar’s oxidation resistance22,36. However, a detailed understanding of how functional groups evolve during H2O2-induced oxidation remain unclear, particularly regarding the combined effects of pyrolysis temperature and feedstock type.

To address the fundamental knowledge gap regarding the mechanistic pathways and intrinsic stability of functional groups in biochars under controlled oxidative conditions, this study prepared biochars derived from wheat straw and dairy manure at 500 °C and 700 °C. The resulting samples were then oxidized using different H2O2 concentrations (as external perturbations). Changes in elemental composition, industrial composition, and dissolved organic carbon (DOC) content of biochars were characterized by wet chemical analyses. Simultaneously, functional groups changes were collected by FTIR spectroscopy. Most importantly, a novel spectroscopic approach incorporating 2D-COS and MW2D-COS was employed to elucidate the evolution of functional groups, providing new insights into biochar oxidation behavior. These mechanistic insights represent a critical first step toward ultimately predicting and optimizing biochar’s environmental applications.

Materials and methods

Biochar preparation

Wheat straw (WS) and dairy manure (DM), as typical agricultural and animal husbandry wastes, exhibit distinct physicochemical properties30,40. Due to their abundance and low cost, WS and DM are commonly utilized for biochar preparation. In this study, WS and DM were collected from the Shangzhuang Experimental Station of China Agricultural University (Beijing, China) and Jinyindao Dairy Farm (Beijing, China), respectively. After being dried at 105 °C for 48 h, the materials were crushed using a pulverizer (RT-34, Rong Tsong Precision Technology Co. Ltd., China) and sieved through a 20-mesh screen. The resulting powder samples were stored in self-sealing bags for future use.

Previous research by the authors revealed that although biochar produced at temperatures ≥ 500 °C exhibited enhanced resistance to chemical oxidation12, its physicochemical properties still changed with varying environmental conditions (such as environmental temperature)21. Therefore, this study selected 500 °C and 700 °C as the pyrolysis temperatures for biochar preparation. Biochar samples were prepared using a tube furnace (GSL-1100X, Hefei Kejing Materials Technology Co. Ltd., China), with a heating rate of 10 °C/min to reach target temperatures, and then held at these temperatures for 1 h. Biochars obtained through pyrolysis at 500 °C and 700 °C from WS (WSB) and DM (DMB) were designated as WSB500, WSB700, DMB500, and DMB700, respectively.

Biochar H2O2 oxidation experiments

Various H2O2 concentrations (0%-30%, w/w) have been used to simulate the oxidation process of biochar22,36,41. Five H2O2 concentrations of 5%, 10%, 15%, 20%, and 30% were selected for the oxidation experiments to simulate varying oxidative degrees of biochar, allowing for the comparative of oxidative susceptibility across biochars rather than replicating natural process. The oxidation process was conducted as follows19,41: biochar samples containing 1 g of C were mixed with 70 mL of H2O2 at different concentrations in Erlenmeyer flasks. Control samples (denoted as CK) were prepared by mixing the biochar with ultrapure water in the same proportions. All mixtures were placed in a shaking incubator at 80 °C for 72 h to ensure thorough oxidation. After that, the mixtures were oven-dried at 105 °C until residual H2O2 and moisture were removed. The dried biochar samples were subsequently mixed with ultrapure water at 1:20 mass-to-volume ratio (g/mL) and agitated in a shaking incubator at 25 °C for 2 h12. The suspensions were filtered through 0.45 μm polyethersulfone membranes to remove free carbon components and minerals released during oxidation. The filtrates were stored at 4 °C in the dark, and the retained biochar residues were redried at 105 °C for 24 h and then sealed for storage. All oxidation treatments, including CK, were performed in triplicate.

Biochar physicochemical analysis

The contents of volatile matter (VM) and ash were determined by a thermogravimetric analyzer (SDTQ600, TA Instruments, Germany). The samples were held at 900 °C for 10 min under N2 for VM and under air atmosphere for ash, until a constant weight was achieved12. The FC content was obtained by subtraction.

The C, H, N, and S contents were measured by an elemental analyzer (Vario MACRO cube, Elementar, Germany). The O content was calculated by mass difference30, and the H/C and O/C ratios were also calculated.

The crystal structure of biochar was characterized by an X-ray diffractometer (XD3, Persee, China) with Co-Kα radiation as the emission source. The instrument was operated at a tube voltage 36 kV and a tube current of 30 mA. Scanning was performed over a 5°‒60° range with step-scan mode parameters: 0.02° step interval and 2°/min scanning speed.

The DOC content in the filtrate was analyzed by a total organic carbon analyzer (Vario TOC, Elementar, Germany).

2D-COS analysis

Collection and processing of FTIR spectra

The FTIR spectra of oxidized biochar were acquired using a spectrometer (Spectrum 400, PerkinElmer, USA). The specific steps were as follows: biochar samples were mixed with KBr powder at 1:150 ratio (w/w) and subsequently scanned to obtain their spectral information. The spectral scanning wavenumber range was set from 4000 to 400 cm⁻¹, with 4 cm⁻¹ resolution and 32 scans. OPUS 8.1 (Bruker, Germany) was used for spectral baseline correction, spectral averaging, and normalization to minimize background interference such as baseline drift during spectral acquisition and to enhance comparability of spectra across different samples.

Calculation of synchronous and asynchronous 2D-COS spectra

A series of one-dimensional FTIR spectra obtained under varying external perturbations were calculated by correlation analysis to obtain two-dimensional correlation intensities, presented as contour plots defined by two independent spectral axes, i.e., 2D-COS spectra. The 2D-COS spectra consist of both synchronous and asynchronous spectra. The synchronous spectrum represents the similarity in spectral intensity changes at two spectral variables (e.g. wavenumber), reflecting the degree of concerted changes between spectral signals. The asynchronous spectrum represents the dissimilarity in spectral intensity changes, indicating the sequential order of changes between spectral signals. The two-dimensional correlation intensities for synchronous (Φ) and asynchronous (Ψ) spectra can be expressed by Eqs. (1) and (2)42,43.

where \({{{v}}_{{1}}}\)and \({{{v}}_{{2}}}\) are two independent spectral variables (wavenumbers), m is the number of spectra used for analysis, \(\tilde{y}\left( {v,t_{j} } \right)\) represents the change in spectral intensity induced by the jth perturbation, and \(~{N_{jk}}\) is the Hilbert-Noda matrix. Here, \(\tilde{y}\left( {v,t_{j} } \right)\)and \({N_{jk}}\) can be expressed by Eqs. (3) and (4), respectively, where t is the perturbation variable (i.e., H2O2 concentration), and j is a discrete variable.

The above calculations were performed using the 2D Shige (Kwansei-Gakuin University, Japan). The resulting synchronous and asynchronous spectra of the 2D-COS were plotted using Origin 2022 (Origin Lab, USA). According to Noda’s theory43, in the synchronous spectra \({{\varvec{\Phi}}}({{{v}}_{{1}}}{{,~}}{{{v}}_{{2}}})\), peaks located on the diagonal (\({{{v}}_{{1}}}={{{v}}_{{2}}}\)) are auto peaks (all with positive values), with their magnitudes indicating the susceptibility of functional group to external perturbations. Peaks located off the diagonal are cross-peaks (with positive and negative values), where positive values indicate similar vibrational changes at \({{{v}}_{{1}}}\)and \({{{v}}_{{2}}}\), and negative values indicate opposite vibrational changes. In the asynchronous spectra \({{\varvec{\Psi}}}({{{v}}_{{1}}}{{,}}{{{v}}_{{2}}}{{~}})\), only cross-peaks exist. When \({{{v}}_{{1}}}>{{{v}}_{{2}}}\), if the signs of the cross-peaks in \({{\varvec{\Phi}}}({{{v}}_{{1}}}{{,}}{{{v}}_{{2}}})\)and \({{\varvec{\Psi}}}({{{v}}_{{1}}}{{,}}{{{v}}_{{2}}})\) are the same, it indicates that the vibration at \({{{v}}_{{1}}}\) precedes \({{{v}}_{{2}}}\); conversely, the vibration changes at \({{{v}}_{{1}}}\) follows \({{{v}}_{{2}}}\).

Calculation of synchronous MW2D-COS spectra

To further reveal the dynamic changes of infrared spectral signals in response to the perturbation variable (H2O2 concentration), the synchronous MW2D-COS analysis was employed. The calculation expression is shown in Eq. (5)44.

where v is the wavenumber, \({{p}}\) represents the perturbation (H2O2 concentration), \({\tilde {y}_{{j}}}\left( {{{v}},~~{{{p}}_{{J}}}} \right)\) represents the dynamic change of the spectrum within a center window of 2n + 1 columns centered at column j (j and J denote the window position and the index of individual spectra within the window, respectively), and \(\tilde{p}_{j}\) is the dynamic perturbation at column j. Herein, \({y_{{j}}}\left( {{{v}},~~{{{p}}_{{J}}}} \right)\) and \(\tilde{p}_{j}\) are expressed as Eqs. (6) and (7), respectively.

The MW2D-COS data were calculated using the 2D Shige (Kwansei-Gakuin University, Japan) with a moving window size of 3. The synchronous MW2D-COS spectra were plotted using Origin 2022 (Origin Lab, USA), where a positive \(\prod {{{\varvec{\Phi}}}_{{j}}}({{v,~}}{{{p}}_{{j}}})\) indicates an increase in spectral intensity, and vice versa.

Statistical analysis

The physicochemical properties of biochar are presented as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 22 (IBM, USA), employing analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) multiple comparison tests at a significance level of 0.01.

Results and discussion

Changes in physicochemical properties of different biochars after H2O2 oxidation

The changes in elemental composition, atomic ratios, industrial composition, and DOC contents for four biochars are shown in Table 1.

In the CK group, WSB demonstrated higher contents of C, H, and FC, while DMB showed higher atomic ratios and ash content at the same pyrolysis temperatures, which may be due to the inherently high presence of these properties in the raw materials21. And there were similar DOC contents of WSB and DMB prepared at the same pyrolysis temperatures. DMB500 exhibited lower H/C ratios and higher O/C ratios than WSB500, indicated its weaker aromaticity and stronger polarity18. Elevated pyrolysis temperature (700 °C) increased the contents of C and FC but reduced the contents of H, O, VM, and DOC as well as atomic ratios. This may be due to further volatilization of unstable organic components (such as aliphatic compounds) at high pyrolysis temperatures, as well as the formation of more stable carbon structures dominated by condensation reactions12. The decrease in DOC content indicated a reduction in soluble organic matter in high-temperature (700 °C) biochar and a trend towards carbon matrix stabilization45.

During oxidation, WSB500 and DMB500 exhibited similar trends in their physicochemical property changes: the contents of C, FC, and H significantly decreased, while the contents of O, VM, ash, and DOC as well as atomic ratios significantly increased with increasing H2O2 concentrations (p < 0.01). Notably, DMB500 initiated changes in the contents of C and FC at a lower H2O2 concentration (15%) than WSB500 (20%), reflecting a lower oxidation resistance of its carbon-related compositions. The physicochemical properties of WSB700 and DMB700 changed little, and their trends with increasing H2O2 concentrations were different. For WSB700, the C content significantly decreased, while the O, VM, and DOC contents as well as atomic ratios significantly increased (p < 0.01). There were no significant changes in the contents of H, ash, and FC (p ≥ 0.01). DMB700 showed no obvious changes in the contents of C, O, ash, FC, and DOC as well as the O/C ratio (p ≥ 0.01), while the contents of H and VM as well as the H/C ratio increased markedly (p < 0.01). These differences may result from different reaction mechanisms during pyrolysis and oxidation processes of the different feedstocks.

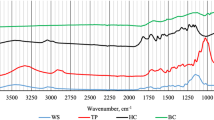

One-dimensional FTIR analysis of Biochar oxidation with different H2O2 concentrations

As shown in FTIR spectra (see supplementary materials), both WSB500 and DMB500 exhibited absorption peaks at 3400–3200 cm− 1, 1600 cm− 1, 1330–1320 cm− 1, 1076 cm− 1, 800 cm− 1, and 440–460 cm− 1. With distinct intensity variations, WSB500 showed the strongest intensity of aromatic C=C peak (1600 cm− 1), while DMB500 exhibited the strongest intensity of C-O peak (1076 cm− 1). Both WSB700 and DMB700 showed strong absorption peaks at 1550–1500 cm− 1 and 1000 cm− 1. Compared with biochar prepared at 500 °C, WSB700 and DMB700 showed stronger intensity of aromatic C=C peaks (1550–1500 cm− 1), confirming that high temperatures favored the formation of aromatic carbon structures45.

As the H2O2 concentration increased, significant changes were observed only in certain peaks of WSB500 and DMB500 (see supplementary materials). Specifically, compared with the CK group, WSB500 oxidized with 5% H2O2 exhibited significant intensity changes at 3600–3000 cm− 1 (-OH). The -OH peaks in both WSB500 and DMB500 exhibited a blue shift as the H2O2 concentration increased, indicating weakening or breakage of hydrogen bonds that formed with hydroxyl group in the biochar46. At 30% H2O2, the intensity of C-O peak (for WSB500) and C=O peak (for DMB500) significantly increased. However, peak overlapping in one-dimensional FTIR spectra obscured most functional group changes in WSB500 and DMB500 during oxidation, consist with previous observations19. Furthermore, the influence of oxidation on the FTIR spectra of WSB700 and DMB700 was minimal, which complicated the spectral interpretation.

2D-COS analysis of biochars oxidized with different H2O2 concentrations

Figure 1 presents the results of 2D-FTIR-COS analysis for four biochars after oxidation in the wavelength range of 4000–400 cm− 1.

As shown in Fig. 1 (a), the synchronous spectrum of WSB500 showed seven auto peaks at 3450 cm− 1, 1718 cm− 1, 1650 cm− 1, 1575 cm− 1, 1416 cm− 1, 1100 cm− 1, and 1000 cm− 1, indicating significant changes in the peaks of -OH, C=O, aromatic C=C, C=C/CH2, C-O/Si-O, and C-OH during oxidation. The highest intensities of auto peaks at 1650 cm− 1 (C=O) and 1575 cm− 1 (aromatic C=C) indicated their high susceptibility to oxidation, which was consistent with previous studies47. The positive cross-peaks Φ(1718, 1650), Φ(1718, 1100), Φ(1575, 1416), and Φ(1416, 1000) indicated the similar changing trends between the peaks of C=O and C-O/Si-O, as well as between the peaks of C=C/CH2 and aromatic C=C (or C-OH). While the negative Φ(1718, 1575), Φ(1718, 1416), Φ(1718, 1000), Φ(1650, 1575), and Φ(1575, 1100) showed that the changing trends in C=O and C-O/Si-O were opposite to those of aromatic C=C, C=C/CH2, and C-OH, which indicated the opposite effects of the increased oxidative stress on the intensity of aromatic C=C/C=C/CH2/C-OH versus C=O and C-O/Si-O48. As shown in Fig. 1(b), the signs of asynchronous cross-peaks Ψ(1718, 1575) and Ψ(1650, 1575) were positive, indicating aromatic C=C changes preceded C=O alternations. The negative Ψ(1575, 1100) suggested that the change in the aromatic C=C peak occurred later than the C-O/Si-O peak. Furthermore, the sign of Ψ(1416, 1000) was positive, and the signs of Ψ(1650, 1000) and Ψ(1718, 1000) were negative, indicating that the change in the C=C/CH2 peak preceded the C=O peak, with the C-OH peak following subsequently. Except for the undeterminable change in the -OH, the oxidation process of WSB500 proceeded in the order of C-O/Si-O → aromatic C=C/C=C/CH2 → C=O → C-OH. The initial oxidative changes of C-O groups reflected the oxidation of residual labile aliphatic fractions18. In contrast, previous studies on naturally aged straw-derived biochar have rarely reported significant alterations in the carbon skeleton (such as the changes of aromatic C=C and C=C)39,49. This difference may be attributed to two main factors: (1) natural oxidation is a milder process, requiring longer filed-experimental observation to detect comparable changes; and (2) the presence of protective mechanisms in natural environments-such as complexation with soil mineral-that may hinder the degradation of carbon structure33.

For WSB700, four auto peaks were observed at 3450 cm− 1, 1745 cm− 1, 938 cm− 1, and 862 cm⁻ 1, which corresponded to the peaks of -OH, C=O, =C-H, and aromatic C-H, respectively. The auto peaks at 3450 cm− 1 (-OH) and 1745 cm− 1 (C=O) had the highest intensities, indicating these two functional groups more sensitive during oxidation. As illustrated in Fig. 1 (c), the signs of Φ(3450, 1745), Φ(3450, 938), and Φ(3450, 862) were negative, whereas the signs of Φ(1745, 938), Φ(1745, 862), and Φ(938, 862) were positive. This indicated inconsistent changes between the -OH and other three functional groups (C=O, =C-H, and aromatic C-H), but consistent changes among the C=O, =C-H, and aromatic C-H. The positive Ψ(3450, 1745), Ψ(3450, 938), Ψ(3450, 862), Ψ(1745, 938), Ψ(1745, 862), and Ψ(938, 862) are shown in Fig. 1(d). According to the signs of above cross-peaks, the evolution of functional groups as the H2O2 concentration increased followed C=O → =C-H/aromatic C-H → -OH. This indicated that the carbon structure of WSB700 was aromatically stabilized, making C=O groups the preferential sites for initial oxidative attack. This may be due to their location at conjugated edges, which makes them more vulnerable to H2O250.

As shown in Fig. 1 (e), DMB500 exhibited six auto peaks at 1650 cm− 1, 1573 cm− 1, 1416 cm− 1, 1260 cm− 1, 1020 cm− 1, and 870 cm− 1, indicating notable changes in the peaks of C=O, aromatic C-C, C=C/CH2, C-O, C-OH, and aromatic C-H during oxidation. The C=O and C-OH peaks had the highest intensities, followed by the peaks of aromatic C=C and C=C/CH2. This suggested that oxygen-containing functional groups and aromatic structure in DMB500 were more susceptible to oxidation48, which aligned with the significant changes in the H/C and O/C ratios (Table 1). Notably, the higher oxidation susceptibility of C=O/C-OH in DMB500 implies its potential for rapid changes under mild oxidation conditions, which may further affects its affinity for certain contaminants20,22. These findings highlight the need to consider such transformations when assessing the environmental remediation performance of DMB500. The positive Φ(1650, 1573), Φ(1650, 1416), Φ(1650, 1260), Φ(1650, 1020), and Φ(1650, 870) indicated inconsistent changes between the C=O peaks and other functional groups, while the positive Φ(1573, 1416), Φ(1573, 1260), Φ(1573, 1020), Φ(1416, 1260), and Φ(1416, 1020) showed consistent changes among the aromatic C=C, C=C/CH2, and C-O peaks. As depicted in Fig. 1 (f), the signs of Ψ(1650, 1573), Ψ(1650, 1416), Ψ(1650, 1260), and Ψ(1650, 870) were positive, indicating the C=O peak changing last. Combing with the positive values of Ψ(1575, 1416) and Ψ(1416, 1020) as well as the negative value of Ψ (1573, 1260), the sequence of functional group evolution followed C-O → aromatic C=C → C=C/CH2 → C-OH/C=O. Compared to WSB500, the early involvement and high susceptibility of aromatic C=C in DMB500 may suggest a less condensed and more vulnerable carbon structure, possibly due to the different feedstock compositions and mineral content. The inherent minerals in manure, such as alkali and alkaline earth metals, have been reported to catalyze the oxidative cleavage of aromatic C-C bonds39, which could explain the early transformation of aromatic rings observed here.

Figure 1 (g) shows five auto peaks for DMB700 with intensities in descending order: 3450 cm− 1 (-OH) > 1655 cm− 1 (C=O) and 625 cm− 1 (carbonate) > 916 cm− 1 (=C-H) and 853 cm− 1 (aromatic C-H). The auto peaks in DMB700 exhibited greater intensity than WSB700, indicated its inferior oxidation resistance; however, DMB700 showed less extensive compositional changes (Table 1). The differences between the bulk compositional changes and spectral response may be related to complex effects of minerals on biochar oxidation31. The positive Φ(3450, 1655), Φ(3450, 625), Φ(1655, 916), Φ(1655, 853), Φ(1655, 625), Φ(916, 853), and Φ(916, 625) were identified in Fig. 1 (g), indicating consistent effects of oxidation on these five functional groups. The signs of Ψ(3450, 1655), Ψ(3450, 916), Ψ(3450, 853), Ψ(1655, 916), Ψ(1655, 853), and Ψ(1655, 625) were positive, while the signs of Ψ(916, 853) and Ψ(916, 625) were negative. These results indicated that sequence of functional group changes followed the order of -OH → C=O → aromatic C-H/carbonate → =C-H.

It is important to note that H2O2 treatment represented an extreme abiotic oxidation scenario. Therefore, the oxidation susceptibility and sequence of functional groups observed in different biochars may not directly comparable to the slower, multi-factorial aging processes (e.g., biological, hydrological) in natural environments49,50. Nevertheless, this method effectively compares the relative stability of different biochars at the functional group levels. For example, the less pronounced intensity changes of functional groups in WSB700 and DMB700, compared to WSB500 and DMB500, during H2O2 oxidation highlighted their superior resistance even under intense chemical oxidation.

MW2D-COS analysis of biochars oxidized with different H2O2 concentrations

Figure 2 presents the results of synchronous MW2D-FTIR-COS analysis for four biochars after oxidation, further elucidating the changes in biochar functional groups.

From Fig. 2 (a), there were two correlated peaks for WSB500 at 3450 cm− 1, with peak values being negative and positive at 5% and 15% H2O2, respectively, which indicated that the intensity of -OH peak first decreased and then increased with increasing H2O2 oxidation degree. The negative correlated peaks appeared in the range of 3100–2200 cm− 1 (C-H) were found above 15% H2O2, suggesting that the oxidation process led to the cleavage of aliphatic C-H bands in biochar48. The correlated peaks related to C=O (1718 cm− 1 and 1650 cm− 1), aromatic C=C (1550 cm− 1), C=C/CH2 (1395 cm− 1), C-O/Si-O (1096 cm− 1), and aromatic C-H (837 cm− 1) were all observed above > 15% H2O2. The signs of aromatic C=C, CH₂/C=C, and aromatic C-H correlated peak were negative, while those of C=O and C-O/Si-O correlated peaks were positive, indicating that the oxidation led to the loss of aromatic carbon structures, the formation of carboxyl groups, and the retention of Si-containing components in the biochar29,39. This aligned with the changes observed in C and O contents as well as atomic ratios for WSB500 (as shown in Table 1). Such a correlation between functional group evolution and bulk compositional change suggests that the oxidation of WSB500 can fundamentally compromise its carbon sequestration potential. Therefore, for applications aimed at long-term carbon sequestration, the susceptibility of WSB500 to oxidative degradation poses a significant challenge, highlighting the need for developing stabilization strategies to enhance their environmental persistence6. And the increase in the Si-O peak intensity may be related to the formation of a dense C-Si structure at 500 °C, enhancing the oxidation resistance of Si-related structures51. This was evidenced by the enhanced intensity of SiO2-related peaks in the X-Ray Diffraction patterns of WSB500 with increasing H2O2 concentrations (see supplementary materials).

As illustrated in Fig. 2 (b), there were two correlated peaks at 3450 cm− 1 (-OH) in WSB700. Based on the signs of correlated peaks, the intensity of -OH peak showed increased at 10% and decreased at 20% H2O2. Both C=O (1793 cm− 1) and =C-H (938 cm− 1) peaks showed two correlated peaks, and their peak values were negative, indicating that the intensities of C-O and =C-H peaks decreased with increasing oxidation degree. This decrease in C=O groups was noteworthy, given that oxygen-containing functional groups played a crucial role in the adsorption mechanisms of organic pollutants37,52. Therefore, the observed reduction could impair the effectiveness of WSB700 in long-term environmental applications, especially in organic pollutant adsorption. The negative C=O cross-peak reached its maximum value at 20% H2O2, indicating a significant decrease in its intensity. This was related to the further oxidation of C=O to CO2 or other substances under higher oxidation degree53. The negative correlated peak related to aromatic C-H at 862 cm− 1 indicated that the oxidation process led to a decrease in its intensity. In addition, there were positive correlated peaks related to C-O and Si-O at 1200 cm− 1 and 466 cm− 1 (at 5% H2O2), indicating that the C-O and Si-O peaks changed dramatically at lower concentrations and reached equilibrium later.

In Fig. 2 (c), the positive correlated peak related to -OH (3450 cm− 1) and the negative correlated peak related to C-H (3100–2400 cm− 1) were observed in DMB500. This indicated that the oxidation led to an increase in -OH peak intensity and a decrease in the C-H intensity. There was a positive correlated peak related to C=O (1650 cm− 1) in the range of 5%-30% H2O2, indicating that the entire oxidation process was accompanied by an increase in the C=O intensity. The signs of correlated peaks related to aromatic C=C (1570 cm− 1) and C=C/CH2 (1412 cm− 1) were positive below 10% H2O2. This may be due to the oxidation, more aromatic carbon structures on the biochar surface, which in turn increased the intensity of absorption peak47. The signs of correlated peaks related to the aromatic C=C and C=C/CH2 turned negative in the 10%-30% H2O2 concentration range with higher absolute peak values, indicating that the carbon structures in biochar were severely damaged at > 10% H2O2 concentration. This damage is likely to facilitate the leaching of carbon components from biochar into the aquatic system39, as evidenced by the obvious increased DOC content of DMB500 at this specific H2O2 concentration (Table 1). However, the severe damage to aromatic C=C and C=C/CH₂ structures at H2O2 concentrations > 10%, coupled with the massive DOC release, was more drastic than changes typically observed in field studies52,54. This suggests that the high H2O2 concentration employed served as a tool for assessing the theoretical maximum oxidation risk of biochar, rather than a direct simulation of field changes. There were negative correlated peaks related to C-O (1260 cm− 1) and C-OH (1040 cm− 1) in the 20%-30% concentration range, indicating a decrease in the intensity of these two peaks. This decrease may be due to their oxidative decomposition, driven by a large amount of reactive oxygen species generated under highly oxidizing conditions52.

From Fig. 2 (d), there were two correlated peaks related to -OH (3450 cm− 1) in DMB700, which were negative at 10% H2O2 and positive at 25% H2O2. This was opposite to the changes of - OH in WSB700. Only one negative C=O correlated peak (1745–1650 cm− 1) was identified in DMB700 at 5% H2O2. This indicated that compared with WSB700, the C=O peaks in DMB700 reached stability at a relative lower H2O2 concentration. In addition, there were two correlated peaks at 625 cm− 1 in DMB700 (assigned to carbonate). The negative values in this functional group were found below 15% H2O2, indicating that its intensity decreased at initial oxidation process. This was supported by the disappearance of CaCO3 peak (2θ = 28.4°) after oxidation in the XRD patterns (see supplementary materials). Furthermore, there were negative correlated peaks related to =C-H (916 cm− 1) and aromatic C-H (853 cm− 1), indicating that their intensities decreased with increasing oxidation degree.

Conclusions

The application of 2D-COS and MW2D-COS analyses elucidated the evolution of functional groups under H2O2 oxidation, revealing different oxidation resistance among the biochars. The biochar prepared at 700 °C, especially WSB700, exhibited enhanced oxidation resistance compared with DMB500 and WSB500. 2D-COS analysis revealed different oxidation susceptibilities and sequences of functional groups in four types of biochars. During oxidation, WSB500 showed more sensitive changes in the C=O and aromatic C=C peaks, with C-O/Si-O peak changing first; while DMB500 showed more sensitive changes in the C=O, aromatic C=C, C=C/CH2, and C-OH peaks, with the C-O peak changing first. Both WSB700 and DMB700 showed minimal functional group changes, starting with C=O changes. MW2D-COS analysis further indicated consistent trends in the aromatic C=C, C=C/CH2, and C=O peaks for WSB500 and DMB500, which was consisted with compositional changes during oxidation. Higher temperature (700 °C) enhances biochar oxidation resistance, with straw-based biochar showing better oxidation resistance.

Future studies will focus on further validating these results, connecting functional group stability to actual environmental performance, and elucidating the underlying structure-activity relationships.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Cowie, A. L. Biochar as a fast track to net zero. Nat. Food. 4 (3), 203–204 (2023).

Hossain, M. Z. et al. Biochar and its importance on nutrient dynamics in soil and plant. Biochar 2 (4), 379–420 (2020).

Singh, H., Northup, B. K., Rice, C. W. & Prasad, P. V. V. Biochar applications influence soil physical and chemical properties, microbial diversity, and crop productivity: a meta-analysis. Biochar 4 (1), 8 (2022).

Deng, X. et al. Exploring negative emission potential of Biochar to achieve carbon neutrality goal in China. Nat. Commun. 15 (1), 1085 (2024).

Cook-Patton, S. C. et al. Protect, manage and then restore lands for climate mitigation. Nat. Clim. Chang. 11 (12), 1027–1034 (2021).

Luo, L. et al. Carbon sequestration strategies in soil using biochar: advances, challenges, and opportunities. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57 (31), 11357–11372 (2023).

Rahim, H. U., Allevato, E., Radicetti, E., Carbone, F. & Stazi, S. R. Research trend of aging Biochar for agro-environmental applications: a bibliometric data analysis and visualization of the last decade (2011–2023). J. Soil. Sci. Plant. Nutr. 23 (4), 4843–4855 (2023).

Zimmerman, A. R. Abiotic and microbial oxidation of laboratory-produced black carbon (biochar). Environ. Sci. Technol. 44 (4), 1295–1301 (2010).

Kamali, M. et al. Biochar for soil applications-sustainability aspects, challenges and future prospects. Chem. Eng. J. 428, 131189 (2022).

Han, L. et al. Quantifying the negative effects of dissolved organic carbon of maize straw-derived Biochar on its carbon sequestration potential in a paddy soil. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 196, 109500 (2024).

Wang, L. et al. Biochar aging: mechanisms, physicochemical changes, assessment, and implications for field applications. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54 (23), 14797–14814 (2020).

Zhang, X. et al. Effect of pyrolysis temperature on composition, carbon fraction and abiotic stability of straw biochars: correlation and quantitative analysis. Carbon Res. 1 (1), 17 (2022).

Duan, W., Oleszczuk, P., Pan, B. & Xing, B. Environmental behavior of engineered biochars and their aging processes in soil. Biochar 1 (4), 339–351 (2019).

Nguyen, B. T., Lehmann, J., Hockaday, W. C., Joseph, S. & Masiello, C. A. Temperature sensitivity of black carbon decomposition and oxidation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44 (9), 3324–3331 (2010).

Kim, H., Kim, J., Kim, T., Alessi, D. S. & Baek, K. Interaction of Biochar stability and abiotic aging: influences of pyrolysis reaction medium and temperature. Chem. Eng. J. 411, 128441 (2021).

Leng, L., Huang, H., Li, H., Li, J. & Zhou, W. Biochar stability assessment methods: a review. Sci. Total Environ. 647, 210–222 (2019).

Liu, Y. et al. Oxidative ageing of Biochar and hydrochar alleviating competitive sorption of cd (II) and Cu (II). Sci. Total Environ. 725, 138419 (2020).

Nie, T., Hao, P., Zhao, Z., Zhou, W. & Zhu, L. Effect of oxidation-induced aging on the adsorption and co-adsorption of Tetracycline and Cu2+ onto Biochar. Sci. Total Environ. 673, 522–532 (2019).

Chang, R., Sohi, S. P., Jing, F., Liu, Y. & Chen, J. A comparative study on Biochar properties and cd adsorption behavior under effects of ageing processes of leaching, acidification and oxidation. Environ. Pollut. 254, 113123 (2019).

Long, X., Yu, Z., Liu, S., Gao, T. & Qiu, R. A systematic review of Biochar aging and the potential eco-environmental risk in heavy metal contaminated soil. J. Hazard. Mater. 472, 134345 (2024).

Zhang, X., Yuan, X., Yang, X., Zhang, H. & Han, L. Environmental leaching of biochar: a full factorial analysis of composition and redundancy. Biomass Conv. Biores. (2025).

Mia, S., Dijkstra, F. A. & Singh, B. Aging induced changes in biochar’s functionality and adsorption behavior for phosphate and ammonium. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51 (15), 8359–8367 (2017).

Wei, J. et al. Limited Cu(II) binding to Biochar DOM: evidence from C K-edge NEXAFS and EEM-PARAFAC combined with two-dimensional correlation analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 701, 134919 (2020).

Zhang, H. et al. Impact of biomass constituent interactions on the evolution of char’s chemical structure: an organic functional group perspective. Fuel 319, 123772 (2022).

Leng, E. et al. In situ evolution of functional groups in char during cellulose pyrolysis under the catalysis of KCl and CaCl2. Fuel 309 (1), 122227 (2022).

Wu, J., Tu, W., Li, C. & He, F. Binding characteristics of copper onto biochar-derived DOM using general, heterospectral and moving-window two-dimensional correlation analyses. J. Hazard. Mater. 435, 129021 (2022).

Dai, Z., Zhao, L., Tian, H., Peng, S. & Yue, Z. Study on removal of Oxytetracycline by KOH-modified chestnut shell biochar: based on two-dimensional spectroscopy and molecular density functional theory. J. Water Process. Eng. 56, 104356 (2023).

Yu, S. et al. The chemical compositions and carbon structures of pine sawdust- and wheat straw-derived biochars produced in air-limitation, carbon dioxide, and nitrogen atmospheres, and their variation with charring temperature. Fuel 315, 122852 (2022).

Maree, Z., Strydom, C. A. & Bunt, J. R. Chemical and physical characterization of spent coffee ground Biochar treated by a wet oxidation method for the production of a coke substitute. Waste Manage. 113, 422–429 (2020).

Zhang, X., Zhang, P., Yuan, X., Li, Y. & Han, L. Effect of pyrolysis temperature and correlation analysis on the yield and physicochemical properties of crop residue Biochar. Bioresour Technol. 296, 122318 (2020).

Liu, G., Pan, X., Ma, X., Xin, S. & Xin, Y. Effects of feedstock and inherent mineral components on oxidation resistance of biochars. Sci. Total Environ. 726, 138672 (2020).

Nan, H. et al. A missing role for enhanced Biochar carbon sequestration from the thermal conversion of biomass to the application in soil. Earth-Sci. Rev. 234, 104215 (2022).

Wang, H., Nan, Q., Waqas, M. & Wu, W. Stability of Biochar in mineral soils: assessment methods, influencing factors and potential problems. Sci. Total Environ. 806, 150789 (2022).

Xu, Z., He, M., Xu, X., Cao, X. & Tsang D.C.W. Impacts of different activation processes on the carbon stability of Biochar for oxidation resistance. Bioresour. Technol. 338, 125555 (2021).

Hardy, B. & Dufey, J. E. The resistance of centennial soil charcoal to the Walkley-Black oxidation. Geoderma 303, 37–43 (2017).

Han, L. et al. Oxidation resistance of biochars as a function of feedstock and pyrolysis condition. Sci. Total Environ. 616, 335–344 (2018).

Yang, X. et al. A critical review of Biochar as an environmental functional material in soil ecosystems for migration and transformation mechanisms and ecological risk assessment. J. Environ. Manage. 360, 121196 (2024).

Li, H., Lu, X., Xu, Y. & Liu, H. How close is artificial Biochar aging to natural Biochar aging in fields? A meta-analysis. Geoderma 352, 96–103 (2019).

Chen, X. et al. Rapid simulation of Decade-Scale charcoal aging in soil: changes in physicochemical properties and their environmental implications. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57 (1), 128–138 (2023).

Struhs, E., Mirkouei, A., You, Y. & Mohajeri, A. Techno-economic and environmental assessments for nutrient-rich Biochar production from cattle manure: a case study in Idaho, USA. Appl. Energy. 279, 115782 (2020).

Liu, Y., Sohi, S., Jing, F. & Chen, J. Oxidative ageing induces change in the functionality of Biochar and hydrochar: mechanistic insights from sorption of atrazine. Environ. Pollut. 249, 1002–1010 (2019).

Harvey, O. R., Herbert, B. E., Kuo, L. & Louchouarn, P. Generalized two-dimensional perturbation correlation infrared spectroscopy reveals mechanisms for the development of surface charge and recalcitrance in plant-derived biochars. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46 (19), 10641–10650 (2012).

Noda, I. Generalized two-dimensional correlation spectroscopy. Front. Mol. Spectrosc. 47 (3), 367–381 (2009).

Morita, S. & Ozaki, Y. Moving-window two-dimensional correlation spectroscopy and perturbation-correlation moving-window two-dimensional correlation spectroscopy. Chemometrics Intell. Lab. Syst. 168, 114–120 (2017).

Sun, T., Sun, Y. B., Huang, Q., Xu, Y. & Jia, H. Sustainable exploitation and safe utilization of biochar: multiphase characterization and potential hazard analysis. Bioresour. Technol. 383, 129241 (2023).

Li, M. et al. Effects of low-frequency and high-intensity ultrasonic treatment combined with curdlan gels on the thermal gelling properties and structural properties of soy protein isolate. Food Hydrocoll. 127, 107506 (2022).

Krzyszczak, A. et al. Long-term physical and chemical aging of Biochar affected the amount and bioavailability of PAHs and their derivatives. J. Hazard. Mater. 440, 15 (2022).

Ghorbani, M. et al. How do different feedstocks and pyrolysis conditions effectively change Biochar modification scenarios? A critical analysis of engineered Biochars under H2O2 oxidation. Energy Conv. Manag. 300, 117924 (2024).

Wang, L. et al. Effects of Biochar aging in the soil on its mechanical property and performance for soil CO2 and N2O emissions. Sci. Total Environ. 782, 146824 (2021).

Yang, X. et al. Aging features of metal(loid)s in Biochar-amended soil: effects of Biochar type and aging method. Sci. Total Environ. 815, 152922 (2022).

Wang, Y., Xiao, X., Xu, Y. & Chen, B. Environmental effects of silicon within Biochar (sichar) and carbon–silicon coupling mechanisms: a critical review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53 (23), 13570–13582 (2019).

Dai, L. et al. Tuning oxygenated functional groups on Biochar for water pollution control: a critical review. J. Hazard. Mater. 420, 126547 (2021).

Ying, Z. et al. Electrochemical upcycling of Biochar particles at anode-electrolyte interface in Biochar-assisted water electrolysis for hydrogen production. Chem. Eng. J. 498, 155681 (2024).

Murtaza, G. et al. Effects of biotic and abiotic aging techniques on physiochemical and molecular characteristics of Biochar and their impacts on environment and agriculture: a review. J. Soil. Sci. Plant. Nutr. 23 (2), 1535–1564 (2023).

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the from the program for National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFD2002101) and Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in the University of the Education Ministry of China (IRT_17R105).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiaoxiao Zhang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Validation, Writing – review & editing. Xiangru Yuan: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Xueqi Yang: Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Zengling Yang: Methodology, Funding acquisition. Lujia Han: Supervision, Funding acquisition, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, X., Yuan, X., Yang, X. et al. Two-dimensional correlation infrared spectroscopy reveals the evolution of functional groups governing biochar oxidation resistance. Sci Rep 16, 1565 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29539-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29539-5