Abstract

Bifunctional electrocatalysts are in demand to pursue dual functions in applications like energy conversion and pollution treatment. In this study, we synthesize the iron-copper-nickel sulfide (FeCuNiS) catalysts with partial amorphous character via the hydrothermal method. The iron rich composition with optimal copper and nickel ratios exhibits robust performances on hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) and oxygen evolution reaction (OER) in alkaline conditions. The partial amorphous feature offers more active sites for reaction due to the partial disordered structure. The partially amorphous FeCuNiS exhibits lower overpotential for HER and OER at 50 mAcm− 2. Moreover, all compositions were found to be electrocatalytically stable. The optimum design and synthesis strategy of the partially amorphous bifunctional electrocatalysts provided in this work will open pathways to advanced electrocatalysts for energy conversion applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Electrocatalysis offers a sustainable pathway to convert water into chemical fuel via water splitting. Pt-based materials are currently the most effective electrocatalysts with the highest activity for the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER), while metal oxides of Ru and Ir metals are used for the oxygen evolution reaction (OER)1. Recently, various crystalline electrocatalysts have been studied, including those containing noble metals (such as Pt, Pd, Ir, Rh, and Ru) and non-noble metals (such as Fe, Ni, and Co).2,3,4,5 However, slow kinetics and high overpotential are the major issues that motivated the designing of new electrocatalysts. The strategies for suppressing the slow kinetics and enhancing electrocatalytic performance for HER and OER can be categorized as: (1) exposure of active sites by decreasing the size of catalysts; (2) enhancing the surface area and shape of crystalline electrocatalysts via morphology engineering (e.g. nanoneedle, nanorod arrays); (3) better electron transfer by heterostructures engineering; and (4) better electron transfer by substrate application6. Even with these initiatives, striking a perfect balance between stability, cost, and performance is still a challenge. Therefore, it is important to keep looking for simple, effective, and low-energy catalytic techniques6.

The amorphous structures have advantage of having more active sites and surface defects due to the generation of various randomly oriented bonds providing a higher number of unsaturated sites for electrocatalysis7. Unfortunately, amorphous materials suffer from low conductivity and are less stability due to the fall in corrosion causing property of material which under the continuous current/potential supply, suffer from structural deformation8. Whereas the crystalline materials offer higher electrical conductivity and more stability. Such materials also provide very high corrosion resistance due to their compact structure and their structural sternness block the interfacial atomic distortion9. In spite of having several advantages, the practical applications of the crystalline materials are impaired by less defect levels and smaller number of active sites10. In order to achieve the advantages of amorphous and crystalline material, designing partially amorphous material could be a smart strategy which could offer balanced surface area, enhanced conductivity, higher ECSA, rich active sites and higher stability.

In this study, we employed the hydrothermal method to synthesize the partially amorphous ternary metal sulfides FeCuNiS and utilized them as electrocatalysts for HER and OER in alkaline conditions. The as-synthesized FeCuNiS were characterized by powder X-ray diffraction (pXRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy dispersive X-ray diffraction spectroscopy (EDX), inductive coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) and Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) analysis. The as synthesized electrocatalysts exhibit distinct lower overpotential values for HER and OER with good stability for 19,000 s.

Experimental

Chemicals

Ferric chloride (FeCl3), copper acetate monohydrate (Cu (CO2CH3)2·H2O), nickel sulphates hexahydrate (NiSO4. 6H2O), sodium sulfide (Na2S), and ethanol were purchased from sigma Aldrich and are used without additional purification.

Synthesis of ternary transition metal sulphide (TTMS) electrocatalysts

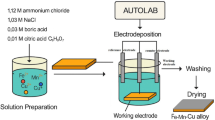

The synthesis of TTMS was performed by the hydrothermal method. Initially, 1.4 mmol of ferric chloride (FeCl3), 1.2 mmol of copper acetate monohydrate (Cu (CO2CH3)2·H2O), and 0.4 mmol of nickel sulphate hexahydrate (NiSO4. 6H2O) were dissolved in 20 mL distilled water to make solution A. Solution B was prepared by dissolving Na2S in 20 mL of distilled water. Then solution A was added dropwise into solution B under constant stirring for 90 min. The resulting solution was placed in an autoclave for 16 h at 160 °C. After that, the product obtained was washed with ethanol and distilled water and dried in an oven at 70 °C. All the other electrocatalysts were synthesized using the same procedure with varying ratios of metal precursors.

Electrochemical measurements

TTMS electrocatalysts were deposited on the surface of nickel foam to make an electrode. For this purpose, a slurry of electrocatalysts whose electrochemical activity is under testing was made by taking 10 mg of FexCuxNixS in 1.0 mL of distilled water, 1.0 mL ethanol, and 10 µL of nafion as binder. The mixture was sonicated for 15 min until the homogenous slurry was formed. The slurry was then deposited to cover the surface of a pre-activated nickel foam. The resulting electrode was then dried at 70 °C and left to rest for 24 h to ensure the complete and good deposition of slurry. This electrode was then tested for its electrochemical water splitting potential. Gamry potentiostat reference 3000 was used for all electrochemical experiments using a standard three-electrode system. The electrocatalysts prepared by depositing the material on the surface of 1 cm2 × 1 cm2 nickel foam was used as the working electrode against Ag/AgCl as the reference electrode, and 99.9% pure platinum wire with 1 mm diameter was used as counter electrode. A 1.0 M KOH solution was used as electrolyte.

Nernst equation (Eq. 1) is used for the calibration of all the potentials.

Equation 2 is used for the overpotential calculation and Eq. 3 is used for Tafel slope calculations where '\(\eta\)' indicates overpotential, ‘a’ is constant, ‘b’ is Tafel slope, and ‘j’ is the current density.

Results and discussion

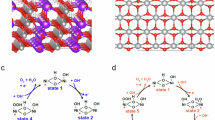

Figure 1a presents the schematic of synthesized FeCuNiS mixed metal sulfide via the hydrothermal method. The as-synthesized materials are isotropic due to the unsymmetrical short-range order, which offers a large active surface area for catalytic activities (Fig. 1b). Moreover, compared to the crystalline form (Fig. 1c), the amorphous electrocatalysts show rich defects due to structural disorders, which justifies that the amorphous catalysts show more electrochemical surface area, ultimately enhancing the catalytic activity11. Three compositions of mixed metal sulfides were synthesized by adjusting the precursor ratios (Fig. 1d). The amorphous/crystalline nature of the as-synthesized mixed metal sulfides (FeCuNiS) was determined by powder X-ray diffraction (pXRD). The as-synthesized FeCuNiS shows broad diffraction peaks, indicating the combination of crystalline and amorphous phases (partially amorphous) (Fig. 1e). The 2θ degree diffraction pattern at 31.4º, 37.63º, 53.66º, and 58.41 corresponds to the (102), (104), (108) and (116) lattice planes of hexagonal phase of CuS12. For iron sulphide (FeS), the crystal planes (011), (211), (212) and (411) are indexed at 28.50º, 31.4º, 37.63º and 47.81º respectively indicating no other plane than monoclinic13. Similarly, the peaks observed at about 18.50º, 31.4º, 33.07º, 37.63º, 47.81º, 53.66º and 58.41º correspond to (110), (020), (311), (511), (440) and (442) planes respectively and confirm the presence of NiS14. The presence of diffused humps with sharp peaks in the XRD plot are a clear indication of the existence of symmetrical but short range order in the synthesized products15. All the diffraction peaks are present in the Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S, Fe0.4Cu1.2Ni1.4S and Fe1.4Cu0.4Ni1.2S mixed metal sulfide, indicating the formation of a partially amorphous phase, acknowledging the coexistence of amorphous and crystalline regions. This partially amorphous structure was expected to contribute to enhanced catalytic activity by increasing defect density and exposing more active sites.

(a) Schematic representation of the hydrothermal synthesis steps of ternary transition metal sulphides (TTMS), (b, c) general structure of amorphous and crystalline TTMS with short-range order and long range order (respectively), (d) concentration of each metal in synthesized Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S, Fe0.4Cu1.2Ni1.4S and Fe1.4Cu0.4Ni1.2S (e) powdered X-ray diffraction patterns of Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S, Fe0.4Cu1.2Ni1.4S and Fe1.4Cu0.4Ni1.2S indicating the presence of FeS, CuS and NiS amorphous phases.

The as-synthesized Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S, Fe0.4Cu1.2Ni1.4S, and Fe1.4Cu0.4Ni1.2S partially amorphous samples were analyzed by SEM and EDX elemental mapping. The SEM images are shown in Figs. 2a, c, e, and EDX elemental mapping is presented in Figs. 3b, d, and f. Figure 2a reveals irregularly shaped, uniformly distributed Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S particles. Whereas the elemental mapping of Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S shows a uniform distribution of corresponding metal ions and sulfides in the interrogated area of the electrocatalysts (Fig. 2b). However, the faded mapping image of Ni represents the very low concentration in the sample. The EDX elemental composition was also determined for the Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S sample. Figure S1 (supporting information) shows the 0.51 at% Fe, 0.2 at% Cu, 0.009 at% Ni, and 6.87 at% sulfur. The lowest concentration of Ni in atomic % ratio is well matched by the EDX elemental mapping results. Figure 2c shows the SEM image of Fe0.4Cu1.2Ni1.4S revealing the formation of flower-like structures. A decrease in particle size can also be observed. This change in size and morphology happens with the increase in Ni concentration and the lowering of Fe concentration in Fe0.4Cu1.2Ni1.4S. As expected, the increase in Ni concentration and the lowering of Fe concentration are visible in elemental mapping (Fig. 2d). Whereas, at% ratio of Fe was 0.48%, 0.32% for Cu, and 1.2% for Ni was observed (Figure S2, supporting information). Figure 2e shows the SEM image of as-synthesized Fe1.4Cu0.4Ni1.2S. With the lowering of Cu concentration while keeping the Fe and Ni concentrations high, small sized irregular structures were appeared. The elemental mapping shows the presence of all the required elements with the lower Cu concentration (Fig. 2f). In elemental EDX, 0.6 at% Fe, 0.28 at% Cu and 0.09 at% Ni were observed as shown in Figure S3 (supporting information). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images further support the presence of amorphous domains. The observed irregular morphologies, non-uniform particle shapes, and absence of well-defined crystalline facets suggest a lack of long range periodicity, which is characteristic of amorphous materials. Combined with the XRD evidence, the SEM analysis reinforces our conclusion that the synthesized FeCuNiS materials possess a partially amorphous character, which plays a critical role in their bifunctional electrocatalytic performance.

(a, c, e) are scanning electron microscopic images of image of Fe1.4 Cu1.2 Ni0.4 S, Fe0.4 Cu1.2 Ni1.4 S and Fe1.4 Cu0.4 Ni1.2 S, indicating the flake like, uniform distribution of metals in electrocatalysts, scale bar is equal to 10 μm (b, d, f) represents the elemental mapping of elements in respective electrocatalysts.

To further determine the concentration of the required elements in the as-synthesized samples. Inductively coupled plasma (ICP) mass spectrometry was performed. Table 1 shows the calculated at% of Fe, Cu, Ni, and S in the as-synthesized samples based on the precursor amounts, and the observed at% of each metal calculated by ICP-MS. In Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S, the 60% higher at% of Fe was observed while at% of Cu and Ni were decreased by -59% and − 33%, respectively. The Fe0.4Cu1.2Ni1.4S sample shows 124% higher at% of Fe than the calculated at%. Likewise, Ni was also increased to 34% compared to the calculated at%. Whereas, the Cu at% was decreased to 80%, which shows that the Fe0.4Cu1.2Ni1.4S is Cu deficient. Finally, in Fe1.4Cu0.4Ni1.2S, again 69% more Fe was observed, but the Cu and Ni at% were dropped to -83% and − 53% respectively. All three samples are highly Fe-rich and Cu deficient. Whereas, in Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S and Fe1.4Cu0.4Ni1.2S, the Ni was found deficient, but the Fe0.4Cu1.2Ni1.4S was Ni-rich. The deficiency of Cu and Ni in the respective samples, could be due to incomplete incorporation of precursors in the final product and material losses during centrifugation and washing of products.

The surface area and pore size distribution in Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S was determined by BET (Brunauer-Emmett-Teller). The N2 gas was used as an adsorptive, and the bath was kept at a temperature of 77.35 K. Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S has a BET surface area of 12.78 m2/g and a total pore volume of 6.2 × 10− 3 cc/g for the pores smaller than 2.6 nm. The micropore surface area obtained using V-t (variable temperature) plot method was 122.29 m²/g, micropore volume was 0.062 cc/g with the external surface area of 109.51 m²/g (Table 2). The high external surface area is associated with small particle size and high degree of porosity16.

Electrochemical HER performance

The HER performance of as-deposited electrocatalysts was investigated in a 1.0 M KOH aqueous solution as an electrolyte within the potential range of -1.5 to 0 V vs. Ag/AgCl. Figure 3a shows the LSV curve of all as-deposited electrocatalysts and the performance of LSV is tabulated in Table S1 (supporting information). The polarization curves are plotted after 100% iR correction to remove the effect of solution resistance. The catalytic loading was maintained at 10 mg/cm2 at the surface of pre-activated nickel foam. To achieve the cathodic current density of -10 mA cm− 2, the Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S requires a very small overpotential of 98 mV, Fe1.4Cu0.4Ni1.2S requires 115 mV, and Fe0.4Cu1.2Ni1.4S requires 107 mV. We compared our results with 20% Pt/C electrode, which requires only 11 mV overpotential to reach − 10 mA cm− 2. Moreover, we also measured the overpotential at a higher current density of 50 mA cm− 2. The Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S requires the overpotential of 171 mV, Fe0.4Cu1.2Ni1.4S requires 175 mV, and the lowest overpotential of 149 mV was required by Fe1.4Cu0.4Ni1.2S to reach the current density of 50 mA cm− 2. Whereas the 20% Pt/C commercial standard has 158 mV overpotential at 50 mA cm− 2. Results indicate that the best HER response at -10 mA/cm− 2 is for the samples with the highest concentration of iron and copper. However, at higher current densities, the lowest overpotential is for samples with the highest iron and nickel concentrations. To evaluate the intrinsic electrocatalytic efficiency of the synthesized FeCuNiS materials, we calculated the mass activity, defined as the current generated per unit mass of catalyst (mA mg⁻¹) at a potential of -0.12 V. This metric provides a normalized comparison of catalytic performance. The Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S catalyst exhibits a mass activity of 1.35 mA mg⁻¹, while Fe0.4Cu1.2Ni1.4S and Fe1.4Cu0.4Ni1.2S show values of 1.00 mA mg⁻¹ and 1.53 mA mg⁻¹, respectively. While, the mass activity of Pt/C was 2.8 mA mg− 1. These results indicate that despite differences in overpotential, all compositions maintain competitive mass normalized activity, reinforcing their potential for scalable and cost-effective water-splitting applications. The Tafel slope was derived from the LSV curves (Fig. 3b), to compare the HER reaction kinetics of the electrocatalysts. The Tafel slopes of Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S, Fe0.4Cu1.2Ni1.4S and Fe1.4Cu0.4Ni1.2S was 31 mV/dec, 41 mV/dec and 37 mV/dec, respectively, which yield the fastest kinetics with Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S for the hydrogen evolution reaction.

As the electrocatalytic performance of all the electrodes was tested in KOH electrolyte solution, the uncompensated resistance (Ru) and charge transfer resistance (Rct) of the electrocatalysts were determined at their respective overpotentials, which are 0.11 V, 0.13 V and 0.12 V for Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S, Fe0.4Cu1.2Ni1.4S and Fe1.4Cu0.4Ni1.2S, respectively, from electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). Figure 3c represents the fitted Nyquist plot with the inset representing the Randles circuit as well as the extended view of Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S, Fe0.4Cu1.2Ni1.4S, and Fe1.4Cu0.4Ni1.2S. Among these catalysts, Fe0.4Cu1.2Ni1.4S has the lowest solution resistance (Rs) of 3.03 Ω, and the Rs values of Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S and Fe1.4Cu0.4Ni1.2S are 3.28 Ω and 3.25 Ω, respectively, as presented in Table S2. Whereas the polarization resistances, also known as charge transfer resistance (Rct), were 47.2 Ω, 49.3 Ω, and 237.8 Ω for Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S and Fe0.4Cu1.2Ni1.4S, respectively, yielding the fastest kinetics of Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S electrocatalysts for HER.

Interestingly, Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S has the lowest overpotential of 98 mV to achieve − 10 mAcm− 2 current, 171 mV overpotential to achieve − 50 mAcm− 2, with the lowest charge transfer resistance (polarization resistance Rp) of 47.2 Ω, indicating the fastest kinetics of the electrocatalyst. This high resistance is due to the higher porosity in the structure17. Although Fe1.4Cu0.4Ni1.2S shows 107 mV overpotential to achieve − 10 mAcm− 2 current, but at -50 mAcm− 2 it requires a lower overpotential of 149 mV as well as lower solution resistance than Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S. Nickel plays a significant role in improving the HER performance, as it provides more active sites and facilitates electron transfer. At the same time, the presence of copper contributes not only to the active sites but also enhances the electrical conductivity of the electrocatalysts18.

(a) Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) plots of Fe1.4 Cu1.2 Ni0.4 S, Fe1.4 Cu0.4 Ni1.2 S and Fe0.4 Cu1.2 Ni1.4 S as compared to the reference Pt/C electrode, (b) Tafel plot of electrocatalysts obtained by plotting potential against log |j|. (c) HER Nyquist plots of Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S, Fe1.4Cu0.4Ni1.2S and Fe0.4Cu1.2Ni1.4S electrocatalysts with the inset indicating the fitted circuit.

Based on these, it can be proposed that the Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S electrocatalysts with higher copper concentration exhibit copper induced higher valence states in nickel, which improve the electrocatalytic performance19. Moreover, copper promotes the Volmer step in the HER mechanism20. These results also reveal the synergy between Fe-Cu and Fe-Ni. The nickel-rich electrocatalysts with Fe-Ni synergy and a small copper concentration show good results at 50 mAcm− 2 with low electrode resistance.

Likewise, the electrocatalytic OER performance of as-synthesized electrocatalysts were also determined. Figure 4a shows the LSV curves of the as-deposited electrocatalysts in the alkaline media. We recorded the reverse LSV to calculate the overpotential of electrocatalysts to avoid the contribution of Ni oxidation peaks in the current density. The overpotentials were calculated at 10 mA cm− 2 and 50 mA cm− 2. To achieve an anodic current density of 10 mA cm− 2, both the Fe1.4Cu0.4Ni1.2S and Fe0.4Cu1.2Ni1.4S require lower overpotential of 340 mV, which is lower than Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S (350 mV), but it was slightly higher than the overpotential of RuO2 (320 mV @ 10 mA cm− 2). The RuO₂ was selected as the reference material due to its well-established activity in alkaline media. As expected, RuO2 exhibits lower overpotentials at both 10 mA cm− 2 and 50 mA cm− 2 current densities. However, our FeCuNiS catalysts, despite showing slightly higher overpotentials, demonstrate comparable Tafel slopes, and favorable charge transfer resistance. These characteristics highlight the practical viability of FeCuNiS as a non-precious, cost-effective alternative for bifunctional water splitting. The trade-off between catalytic activity and material cost is a critical consideration for scalable energy applications, and our results suggest that partially amorphous FeCuNiS electrocatalysts strike a promising balance between performance, and affordability.

To further evaluate the intrinsic efficiency of the synthesized electrocatalysts, mass activity measurements were conducted at a fixed potential of 1.55 V vs. RHE. This metric reflects the current generated per unit mass of catalyst and serves as a reliable indicator of how effectively the active material contributes to the overall reaction. Among the FeCuNiS compositions, both Fe0.4Cu1.2Ni1.4S and Fe1.4Cu0.4Ni1.2S exhibited the highest mass activity values of 0.357 mA mg− 1, while Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S showed a slightly lower value of 0.21 mA mg− 1. For comparison, the benchmark RuO2 catalyst delivered a mass activity of 1.00 mA mg− 1 under the same conditions. Although the FeCuNiS catalysts do not surpass RuO2 in absolute activity, their performance is notable given their non-precious composition. These results highlight the potential of FeCuNiS systems as cost-effective alternatives for oxygen evolution, especially when considering the balance between activity, material abundance, and stability.

The overpotential was also calculated at 50 mA cm− 2, which shows that Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S and Fe1.4Cu0.4Ni1.2S exhibit an overpotential of 380 mV, whereas Fe0.4Cu1.2Ni1.4S overpotential rises to 410 mV, as compared to 370 mV overpotential of RuO2 at 50 mAcm− 2. To probe the reaction kinetics, the Tafel plot of as-deposited catalysts was drawn in Fig. 4b. The Tafel slope of Fe0.4Cu1.2Ni1.4S was 63 mV/dec, much lower than Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S (100 mV/dec) and Fe1.4Cu0.4Ni1.2S (106 mV/dec). The lower Tafel slope indicates faster kinetics and possibly a change of rate-determining steps. Overpotentials and Tafel slopes for all the electrocatalysts are tabulated in Table S3.

The charge transfer resistance on the surface of the as-deposited electrocatalysts was analyzed by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). The uncompensated resistance (Ru) and polarization resistance (Rp), along with the complex transfer function (Cf), are listed in Table S4. As shown in Figure 4c, OER Nyquist plots of the electrocatalysts were fitted with an equivalent Randles model circuit, to obtain various impedance elements.

(a) Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) plots of Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S, Fe1.4Cu0.4Ni1.2S, Fe0.4Cu1.2Ni1.4S and Fe0.4Cu1.4Ni1.2S as compared to the reference Pt/C electrode, (b) Tafel plot of electrocatalysts obtained by plotting potential against log |j|. (c) OER Nyquist plots of Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S, Fe1.4Cu0.4Ni1.2S, Fe0.4Cu1.2Ni1.4S, and Fe0.4Cu1.4Ni1.2S electrocatalysts with the inset showing the Randles circuit model used for fitting.

The uncompensated resistance for Fe0.4Cu1.2Ni1.4S electrocatalyst was 3.21 Ω and the polarization resistance (Rp) was as low as to 12.99 Ω. The Rp values suggest the fastest reaction kinetics for Fe0.4Cu1.2Ni1.4S which was exactly in correspondence with the lowest Tafel slope. Solution resistances of 3.54 Ω, 3.23 Ω, and 1.88 Ω were observed for Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S, Fe1.4Cu0.4Ni1.2S, and Fe0.4Cu1.4Ni1.2S electrocatalysts. Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S exhibits Rp value of 14.39 Ω. Whereas, the Rp value of Fe1.4Cu0.4Ni1.2S was 198.3 Ω, and Fe0.4Cu1.4Ni1.2S was 277.8 Ω.

Cyclic voltammetry (CV) in 1.0 M KOH was used to electrochemically characterize the as-deposited mixed metal catalysts at different scan rates, ranging from 5 mVs− 1 to 100 mVs− 1 (Figure S4a-d, supporting information). The CV curves of the as-deposited electrodes at the same scan rate are shown for comparison in Fig. 5a. The redox peaks are seen from 1.2 to 1.7 V for all the FeCuNiS electrodes. These peaks can be attributed to the oxidation/reduction M+ 2/M+ 3 process (Faradic redox behavior) due to the hydroxyl OH− ions in the electrolyte. Anodic peak current (Ip.a.) and cathodic peak current (Ipc) were calculated from CV redox peaks for all materials (Fig. 5b). The anodic peak currents for Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S, Fe1.4Cu0.4Ni1.2S, and Fe0.4Cu1.2Ni1.4S were 22.49 mA cm− 2, 18.11 mA cm− 2, and 12.71 mA cm− 2 and the cathodic peak currents were − 19.55 mA cm− 2, -16.10 mA cm− 2, and − 11.57 mA cm− 2 respectively. The highest peak current was observed in Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S, indicating the high redox activity of this electrocatalyst. Both anodic (Ip.a.) and cathodic (Ipc) current peaks manage to conserve their linearity when plotted against the square root of the scan rates (Fig. 5b), which is a clear indication of diffusion-controlled transfer of electrons from electrode to electrolyte. The ratio of anodic and cathodic peak current (Ip.a./Ipc) is slightly larger than one (Table 3), which shows that the reaction is not fully reversible.

(a) Cyclic voltammograms of synthesized electrocatalysts at the potential range of 1 to 2 V (vs. RHE), (b) Anodic peak current (Ipa) and cathodic peak current (Ipc) values of electrocatalysts, (c) Plot of double layer capacitance (Cdl) of electrocatalysts in µFcm− 2 obtained by plotting ∆J against scan rate, (d) Electrochemical surface area of electrocatalysts in cm− 2.

To support our claim of increased active sites, we carried out cyclic voltammetry (CV) measurements in the non-faradaic regions at different scan rates and calculated the electrochemical double-layer capacitance (Cdl) for each sample. Cdl is commonly used as an indirect measure of electrochemical surface area (ECSA), which reflects the portion of the catalyst surface actively involved in the reaction. A higher ECSA generally suggests a greater number of accessible active sites. Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S exhibits the highest Cdl of 120 µFcm− 2, whereas the lowest Cdl is observed for Fe0.4Cu1.2Ni1.4S (85.5 µFcm− 2) and Fe1.4Cu0.4Ni1.2S has a Cdl of 89 µFcm− 2 (Fig. 5c). ECSA is calculated using Eq. 5, which is the highest for Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S. The same electrocatalysts also have the highest Cdl as well as Ip.a. and Ipc. The ECSA of Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S, Fe1.4Cu0.4Ni1.2S and Fe0.4Cu1.2Ni1.4S was 300 cm− 2, 222.5 cm− 2 and 213.7 cm− 2 respectively (Fig. 5d). The high ECSA of Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S reveals high intrinsic activity. With a BET surface area of 12.78 m2g− 1 and a pore size of approximately 2.6 nm, Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S appears to have a mesoporous structure that facilitates ion diffusion. The Cdl value of the respective electrocatalyst appears to 120 µFcm− 2 compared to the other two electrocatalysts Fe0.4Cu1.2Ni1.4S (85.5 µFcm− 2) and Fe1.4Cu0.4Ni1.2S (89 µFcm− 2) which is consistent with the ECSA values derived from Cdl.

The higher ECSA of Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S suggests a higher number of available electrochemical active sites which corresponds directly to its superior electrocatalytic performance characterized with lower overpotential and a smaller Tafel slope value. Although the exact TOF calculation for such multimetallic sulphides is challenging due to the dynamic surface reconstruction of active sites under the applied conditions. The consistent improvement in BET surface area, Cdl and ECSA combined with enhanced charge transfer kinetics clearly indicate that good catalytic activity of electrocatalyst is due to intrinsic electronic and structural optimization rather than surface area alone.

These results indicate that more electrochemically active sites are present on the surface of Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S, yielding its excellent bifunctional electrocatalytic activity for both the OER and HER activities.

The improved electrocatalytic performance observed in the FeCuNiS systems can be attributed, in part, to their partially amorphous nature. The presence of disordered regions within the catalyst structure introduces a high density of structural defects, unsaturated coordination sites, and increased surface heterogeneity. These features are known to facilitate faster reaction kinetics and enhance charge transfer efficiency. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) data support this interpretation, showing lower polarization resistance for the Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S sample compared to its counterparts, indicating more efficient electron transport across the electrode-electrolyte interface. Additionally, cyclic voltammetry (CV) profiles reveal more pronounced redox peaks, suggesting higher faradaic activity and a greater number of electrochemically accessible active sites. Together, these findings underscore the beneficial role of partial amorphous nature in promoting catalytic activity and stability under alkaline conditions.

The electrochemical stability of the electrocatalysts was determined by chronoamperometry. It was investigated at a constant applied current density (japp). As shown in Fig. 6 all the electrodes are completely stable for 19,000 s under the applied current density. The step 1 current was 0.16 Amperes, and the step 2 current was set to 2.0 Amperes for the Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S electrocatalyst. For Fe0.4Cu1.2Ni1.4S, the applied current intensities were 1.0 Amperes for step 1 and 2.0 Amperes for step 2. For Fe1.4Cu0.4Ni1.2S, the corresponding current intensities were 1.0 Amperes and 2.3 Amperes, respectively. Fe1.4Cu0.4Ni1.2S has the highest potential of ~ 2.25 V, while Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S and Fe0.4Cu1.2Ni1.4S have ~ 2.1 V and ~ 1.95 V, respectively. Due to experimental constraints, we were unable to extend the stability testing duration further. Therefore, we reflect moderate stability rather than robust claims. Future studies will aim to explore long-term cycling and extended durability under practical conditions.

As Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S shows the best electrochemical response towards electrochemical HER and OER among all the electrocatalysts; therefore, we performed the XPS analysis of Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S. Figure 7a represents the survey plot containing all the characteristic peaks of respective elements in the electrocatalyst, confirming the synthesis of Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S. The high-resolution spectra of respective elements are given in Fig. 7b-e. The two binding energy peaks at 706 eV and 720 eV were attributed to the Fe2p3/2 and Fe2p1/2 (Fig. 7b). The presence of a satellite peak at about 715 eV suggests the mixed oxidation state for iron in the electrocatalysts, likely a combination of Fe+ 2 and Fe+ 3.19 Fig. 7c shows the high-resolution Cu 2p XPS spectra of Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S. The asymmetric peaks of Cu 2p are due to the different oxidation states of copper in the as-synthesized sample. The binding peaks at 932 eV and 952 eV for Cu2p3/2 and Cu2p1/2, respectively. The two peaks are separated by 20 eV, which indicates the presence of monovalent Cu+ species.19 As shown in Fig. 7d, the Ni2p3/2 binding peak was observed at 855 eV, and Ni2p1/2 was at 872 eV of Ni2+, and both are followed by satellite peaks, centered at 856.9 eV and 875.9 eV, suggesting Ni+ 2 oxidation state in the final product. Sulphur XPS peaks, S2p3/2 and S2p1/2 can be observed at the binding energy values of 157.5 eV and 163.5 eV, respectively (Fig. 7e)21. The binding energy values for Fe 2p3/2, Fe 2p1/2, Cu 2p3/2, Cu 2p1/2, Ni 2p3/2, Ni 2p1/2, S2p3/2, and S2p1/2 peaks are consistent with the binding energy values of Fe, Cu, Ni being in a sulfide environment.

The XPS survey spectrum indicated the presence of Fe, Cu, Ni and S with the corresponding concentration (atomic %) of 64.61%, 17.50%, 11.59% and 6.30% confirming the successful incorporation of multi-metallic species in the sulphide matrix (Table S6). The relative concentration of each oxidation state is given in table S7. Where coexisting Fe+ 3 (70.46%) and Fe+ 2 (29.54%) indicate the generation of highly abundant Fe sites acting as the redox active center for OER. Copper (Cu+ 1 and Cu+ 2) is present with dominant Cu+ 2 state which is 88.56% and Nickel (Ni+ 2 and Ni+ 3) with dominant Ni+ 3 state which is 81.59%. The coexistence of these metal centers indicating the strong electronic coupling among the metal centers. This coupling promotes rapid electron transfer and enhance the intrinsic catalytic activity of electrocatalysts. The presence of S2p3/2 and S2p1/2 confirms the metals are stable in sulfide matrix that promotes charge delocalization. The predominance of high valent Fe, Cu and Ni sites noticed in XPS also emphasized that the catalytic activity is not solely because of higher surface area but also due to the enhanced intrinsic activity of these surface states.

We have compiled a comprehensive comparison table (Table S5) summarizing key performance metrics: overpotential at 10 mA cm⁻² for both OER and HER, Tafel slope, and stability duration for our electrocatalysts alongside representative state-of-the-art non-precious electrocatalysts reported in the literature. Our Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S electrocatalyst demonstrates an OER overpotential of 340 mV and a Tafel slope of 63 mV dec− 1, which are competitive with or superior to many benchmark materials such as Fe-Ni3S2 nanosheet arrays (214 mV, 42 mV dec− 1) and Ni–Fe–Co–S nanosheets (207 mV, 63 mV dec− 1), while also offering robust HER performance (115 mV overpotential) and 5-hour stability22. Although some systems like MoS2/Fe5Ni4S8 heterostructures report lower Tafel slopes (28.1 mV dec− 1), our catalyst balances both OER and HER activity with favorable kinetics and structural simplicity23. Notably, while certain LDH-based systems such as NiFeLa-LDH/v-MXene/NF exhibit exceptional long-term stability (up to 400 h), our material maintains consistent performance over 5 h, which can be further optimized24. This comparative analysis positions our multi-metallic sulfide catalysts as promising bifunctional electrocatalysts, combining efficient charge transfer, favorable surface states, and competitive activity metrics within the broader landscape of non-precious OER/HER materials.

Conclusions

In summary, FeCuNiS-based partially amorphous sulfides with superior electrocatalytic HER and OER activities have been synthesized via a facile method. The Fe1.4Cu1.2Ni0.4S, Fe0.4Cu1.2Ni1.4S, and Fe1.4Cu0.4Ni1.2S compositions show significantly lower overpotentials of 430 mV, 460 mV, and 410 mV for OER at 50 mAcm− 2 and 171 mV, 175 mV, 149 mV for HER at -50 mAcm− 2, respectively. Moreover, all the compositions synthesized maintain reliable performance over 19,000 s. The unique partial amorphous structure and synergistic effect of Fe, Cu, and Ni improve the bifunctional OER and HER performances. This work provides insights into the perspective of high-entropy amorphous ternary metal sulfide electrocatalysts for bifunctional processes.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper, its supplementary information files.

References

Che, M., Zhao, X. & Gong, Y. Synthesis of Ni-Cu-Fe trimetallic Selenides on nickel foam for efficient oxygen evolution reaction. Available SSRN 5098655.

Li, Y. et al. Recent advances on water-splitting electrocatalysis mediated by noble‐metal‐based nanostructured materials. Adv. Energy Mater. 10 (11), 1903120 (2020).

Cao, L. et al. Identification of single-atom active sites in carbon-based cobalt catalysts during electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution.

Han, N.; Yang, K. R.; Lu, Z.; Li, Y.; Xu, W.; Gao, T.; Cai, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Batista, V. S.; Liu, W. Nitrogen-doped tungsten carbide nanoarray as an efficient bifunctional electrocatalyst for water splitting in acid. Nature communications 2018, 9 (1), 924

Zhou, Y.; Zhang, J.; Song, E.; Lin, J.; Zhou, J.; Suenaga, K.; Zhou, W.; Liu, Z.; Liu, J.; Lou, J Enhanced performance of in-plane transition metal dichalcogenides monolayers by configuring local atomic structures. Nature Communications 2020, 11 (1), 2253. (2019).

Zhou, Y. & Fan, H. J. Progress and challenge of amorphous catalysts for electrochemical water splitting. ACS Mater. Lett. 3 (1), 136–147 (2020).

Singh, M. et al. A critical review on amorphous–crystalline heterostructured electrocatalysts for efficient water splitting. Mater. Chem. Front. 7 (24), 6254–6280 (2023).

Anantharaj, S., Reddy, P. N. & Kundu, S. Core-oxidized amorphous Cobalt phosphide nanostructures: an advanced and highly efficient oxygen evolution catalyst. Inorg. Chem. 56 (3), 1742–1756 (2017).

Fominykh, K. et al. Ultrasmall dispersible crystalline nickel oxide nanoparticles as high-performance catalysts for electrochemical water splitting. Adv. Funct. Mater. 24 (21), 3123–3129 (2014).

Zhang, L. et al. Sodium-decorated amorphous/crystalline RuO2 with rich oxygen vacancies: a robust pH‐universal oxygen evolution electrocatalyst. Angew. Chem. 133 (34), 18969–18977 (2021).

Guo, T. et al. Recent development and future perspectives of amorphous transition metal-based electrocatalysts for oxygen evolution reaction. Adv. Energy MaterialsSmall Sci. 121 (24)(9)), 2200827 (20222021).

Simonescu, C. M., Teodorescu, V. S., Carp, O., Patron, L. & Capatina, C. Thermal behaviour of CuS (covellite) obtained from copper–thiosulfate system. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 88, 71–76 (2007).

Sathiyaraj, E. & Thirumaran, S. Structural, morphological and optical properties of iron sulfide, Cobalt sulfide, copper sulfide, zinc sulfide and copper-iron sulfide nanoparticles synthesized from single source precursors. Chem. Phys. Lett. 739, 136972 (2020).

Balayeva, O. O. et al. Effect of thermal annealing on the properties of nickel sulfide nanostructures: structural phase transition. Mater. Sci. Semiconduct. Process. 64, 130–136 (2017).

Güneri, E. & Kariper, A. Optical properties of amorphous CuS thin films deposited chemically at different pH values. J. Alloys Compd. 516, 20–26 (2012).

Gregg, S. J., Sing, K. S. W. & Salzberg, H. Adsorption surface area and porosity. Journal of The electrochemical society 114 (11), 279Ca. (1967).

Dumont, H., Los, P., Brossard, L. & Menard, H. Influence of physicochemical properties of alkaline solutions and temperature on the hydrogen evolution reaction on porous Lanthanum-Phosphate‐Bonded nickel electrodes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 141 (5), 1225 (1994).

Gao, D. et al. Copper mesh supported nickel nanowire array as a catalyst for the hydrogen evolution reaction in high current density water electrolysis. Dalton Trans. 51 (13), 5309–5314 (2022).

Wang, H. et al. Copper doping-induced high-valence nickel-iron-based electrocatalyst toward enhanced and durable oxygen evolution reaction. Chem Catalysis 3 (3). (2023).

Zhang, L. et al. Electrocatalytically inactive copper improves the water adsorption/dissociation on Ni 3 S 2 for accelerated alkaline and neutral hydrogen evolution. Nanoscale 13 (4), 2456–2464 (2021).

Li, L. et al. FeS 2/carbon hybrids on carbon cloth: a highly efficient and stable counter electrode for dye-sensitized solar cells. Sustainable Energy Fuels. 3 (7), 1749–1756 (2019).

Tang, Q. et al. Mechanism of hydrogen evolution reaction on 1T-MoS2 from first principles. Acs CatalysisNanoscale. 611 (835), 4953–4961 (20162019).

Wu, Y. et al. Coupling interface constructions of MoS2/Fe5Ni4S8 heterostructures for efficient electrochemical water splitting. Adv. Mater. 30 (38), 1803151 (2018).

Yu, M., Zheng, J. & Guo, M. La-doped NiFe-LDH coupled with hierarchical vertically aligned MXene frameworks for efficient overall water splitting. J. Energy Chem. 70, 472–479 (2022). Nature Catalysis 2 (2), 134–141

Funding

This research work is supported by the Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE) under the 2023 Translational Research Program for the Energy Sustainability Focus Area (Project ID: MMUE/240001), the 2024 ASEAN IVO (Project ID: 2024-02), and Multimedia University, Malaysia. Research at Queen’s was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (RGPIN-2020-07016). Author also would like to extend their sincere appreciation to the ongoing Research Funding Program (ORF-2025-579), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mehak Ghafoor: formal analysis, investigation, write-original draftMuhammad Aamir: supervision; Visualization, Writing - Review & EditingMuhammad Sher: Methodology, Resources*Vidhya Selvanathan: Resources and formal analysis**Hamad Fahad Alharbi: supervising and editing**Md. Shahiduzzaman: investigtion and idea**Tetsuya Taima: Reviewing and supervising*Jean-Michel Nunzi: funding acquisition, writing–review & editingIt Ee Lee: funding acquisition, resourcesQamar Wali: funding acquisition, resources, Project management.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

*Corresponding

amir.chem@must.edu.pk; ielee@mmu.edu.my; nunzijm@queensu.ca.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ghafoor, M., Aamir, M., Lee, I.E. et al. Partially amorphous iron-copper-nickel sulfides for robust bifunctional electrocatalysis. Sci Rep 15, 45582 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29540-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29540-y