Abstract

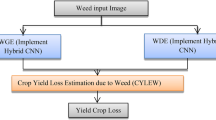

Weeds, defined by their ecological and economic impact rather than taxonomy, present a major challenge to agriculture by competing with crops for limited resources and serving as vectors for disease. In Monterey County, California, one of the most productive farming regions in the United States, Sonchus oleraceus (annual sowthistle) and Malva parviflora (little mallow) have been linked to over $150 million in crop losses due to their role in spreading Impatiens Necrotic Spot Virus (INSV). As precision agriculture becomes more important in high-value production systems, deep learning and image-based classification offer promising tools for early weed detection and disease prevention. To address the absence of region-specific image datasets, this study presents the first curated, high-resolution image collection of INSV-associated weeds from Monterey County, captured under greenhouse conditions designed to mimic field variability. This dataset fills a documented gap in existing global repositories such as PlantCLEF and DeepWeeds, which lack representation of California’s high-value crop systems. This study compares three convolutional neural networks—ResNet-50, ResNet-101, and DenseNet-121—for classifying these visually similar weeds under controlled conditions that approximate real field environments. RGB images were augmented to improve model robustness, and training was conducted across ten independent stratified data splits.

Among the tested architectures, ResNet-101 achieved the highest median classification accuracy (91%) and Cohen’s Kappa (0.87), while DenseNet-121 demonstrated the strongest F1-score and AUC values exceeding 0.99. These results confirm that dataset augmentation substantially enhanced model generalization. The results demonstrate that deep learning can support accurate and reliable weed identification, paving the way for real-time detection systems and more targeted, sustainable weed control practices in precision agriculture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Annual sowthistle (Sonchus oleraceus) and little mallow (Malva parviflora) are widespread weeds known to compete with crops for essential resources including water, nutrients, and light 1. These weeds have frequent interactions with lettuce, one of Monterey County’s highest-yielding crops, causing significant economic losses. In 2022, farmers in Monterey County faced roughly $150 million in losses due to Impatiens Necrotic Spot Virus (INSV) infected crops associated with INSV-transmitting weeds2. Annual sowthistle and little mallow, shown in Fig. 1, are major contributors to the spread of INSV and facilitate infections across seasons, adversely impacting crop yields in Monterey County3. Annual sowthistle is a highly adaptable weed species capable of thriving in a wide range of environmental conditions4. It grows year-round and has an INSV infectivity rate exceeding 20%5. Similarly, little mallow, which also grows year-round, is commonly found in production fields, waste areas, and along roadsides. It displays an infectivity rate of 20% and serves as a reservoir for INSV5.

Traditional weed management strategies have typically relied on methods such as pesticide application, manual herbicide spraying, and physical labor. These approaches are often expensive and can negatively impact the environment6. Recent advancements in agricultural robotics have enabled the development of autonomous systems that can perform tasks that include the planting, watering, and harvesting of crops. However, these tasks do not require as much precision and effort compared to challenges posed by selective weeding7. Traditional image processing technologies and machine learning methods have become increasingly useful to differentiate between crops and weeds8. As robotics continue to evolve within the agricultural sector, the availability of robust datasets containing weed specimens has become critical for accurate weed detection and identification9.

Machine learning (ML), and in particular deep learning (DL), has shown significant promise in automating weed classification through image-based methods. DL has demonstrated significant success in automating weed species classification, enabling more accurate and timely detection of invasive plants 1. ML methods have found widespread applications in multiple domains including biochar10, drug design11, solar cells12, glassware identification of chemistry equipment13, structural motifs identification in asphaltenes14, classification of fungi based on microscopic images15, and numerous others. While ML is widely applied across agricultural and scientific domains, prior studies on weed identification have largely focused on common weed species with limited regional specificity16,17,18. Traditional methods of identifying plant species through visual identification methods can be time-consuming and inaccurate, which is often unsuitable in practice. However, despite these advances, current datasets often lack representation of region-specific weed species that act as disease vectors. Sonchus oleraceus and Malva parviflora, two species linked to Impatiens Necrotic Spot Virus outbreaks in California’s Salinas Valley have not been the subject of dedicated image-based classification efforts. Existing large-scale datasets such as PlantCLEF17 and DeepWeeds18 focus on broader geographic regions and do not include high-resolution images of these specific weeds under simulated field conditions. Our study bridges this gap by developing a localized dataset and testing the performance of three Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)19, ResNet-5020,21,22, ResNet-10122,23, and DenseNet-12124,25, under conditions designed to simulate practical deployment26.

Additionally, DL techniques have been used to identify diseases by extracting and classifying specific features indicative of leaf blotch, powdery mildew, and rust, as well as disease symptoms from abiotic environmental stressors. However, these methods have limitations that prevent the detection of more subtle or early stages of disease and even in processing certain images27. DL techniques, including CNNs and deep belief networks (DBNs), are becoming more popular for their ability to detect plant diseases through their meticulous scanning of the images. However, they do come with drawbacks, such as extensively labeled data, expensive computations, and unknown data. To address these challenges, researchers have increasingly applied transfer learning and ensemble methods, which improve model performance on limited datasets and enhance generalizability.27 Additionally, data augmentation has also increased in popularity to create more robust data sets. Support vector machines are advanced techniques used to analyze images and detect specific plant features and diseases. However, their effectiveness is limited by the need for well-labeled and robust datasets and the challenge of incorporating new diseases. DL models like CNNs and DBNs can quickly learn from new data without support, but similarly require large, labeled data sets and expensive, computational resources27.

DL uses network feature structures and extracts these features using various methods, that have been proven to be more effective than manually extracted features. Methods associated with deep learning use spatial and semantic feature differences to accurately identify and detect crops and weeds8. These methods improve the overall accuracy of weed detection and are combined with the use of CNNs or Fully Convolutional Networks (FCNs). CNNs utilize learning-based segmentation and color space transformations, allowing the network to segment images and identify weeds. These networks require learning complex patterns that include lighting variations, overlapping leaves, and occlusions28. CNNs and DBNs have gained prominence in agricultural applications due to their capacity to learn complex patterns from labeled image data, enabling efficient detection of weeds and plant diseases27. However, the effectiveness of these models relies heavily on the availability of curated, annotated datasets representative of real-world variability. Although model training can be resource-intensive, well-trained neural networks have demonstrated high performance across a range of image recognition tasks, with CNNs achieving classification accuracies exceeding 99% under ideal conditions27. In this study, we address the challenge of weed identification using a regionally specific dataset featuring Sonchus oleraceus and Malva parviflora, cultivated under varied greenhouse conditions to emulate field-level heterogeneity typical of Monterey County. High-resolution RGB images were collected in controlled lighting environments that approximate natural field scenarios. We evaluated the classification performance of three well-established CNN architectures – ResNet-5021,22,29, DenseNet-12124,25, and ResNet-10123, on two datasets: a baseline (non-augmented) image set, and an augmented version designed to improve generalization. This design enabled assessment of both model accuracy and the role of data augmentation in enhancing classification robustness.

Methods

Image acquistion and dataset preparation

Images were collected using a Kodak PIXPRO AZ401RD point-and-shoot digital camera (16 MP CCD sensor, 24 mm wide-angle lens, 40 × optical zoom, and 3-inch LCD display) under uniform lighting conditions. Each image was cropped, labeled, and standardized using the Thumbnail function in the Wolfram Language, ensuring consistent input dimensions for deep-learning model training. The dataset focused on two weed species: Sonchus oleraceus (annual sowthistle) and Malva parviflora (little mallow), grown in a greenhouse environment designed to simulate field-relevant stress conditions representative of coastal California agriculture. For annual sowthistle, plants were cultivated under six treatment conditions: standard, overwatering, excess fertilizer, low fertilizer, mechanical injury, and drought. Little mallow was grown under four treatment conditions: standard, excess fertilizer, mechanical injury, and drought. The detailed specifications for each treatment condition are summarized in Table 1. To improve image consistency and minimize background interference, all images were manually cropped to center the weed specimen and exclude non-essential visual elements.

Data augmentation

The full dataset comprised images from ten distinct classes—corresponding to various environmental treatments for each of the two weed species. For each of the ten trials, we performed stratified sampling such that 80% of the images from each class were allocated to the training set and the remaining 20% to the test set. This ensured that the distribution of classes was preserved across both training and testing subsets, thereby maintaining representation of all treatment conditions. By generating multiple randomized yet class-balanced partitions, we obtained a statistically reliable estimate of model performance while mitigating the influence of any particular data split. Data augmentation was applied exclusively to the training set in each split to expand variability and simulate real-world image conditions. Augmentation techniques included controlled transformations such as blurring, lighting adjustment, sharpening, and geometric modifications (e.g., small-angle rotations and horizontal reflections), thereby increasing model robustness to common visual perturbations30,31,32. The test set remained unaugmented to ensure an unbiased assessment of generalization performance. This design is also referred to as repeated random sub-sampling validation is especially well-suited for datasets where stratified sampling and repeated trials offer improved reliability over fixed k-fold partitioning.

To assess the contribution of data augmentation to model generalization, all three neural networks were also trained and evaluated on the original, non-augmented dataset using the same stratified sampling procedure. This allowed for a direct comparison between models trained on augmented and non-augmented data, quantifying the impact of augmentation on classification accuracy and robustness. Following image acquisition, the original RGB images were computationally augmented using the ImageEffect33 and related image processing functions available in the Wolfram Language34 (Mathematica), thereby generating a larger and more diverse dataset for training and evaluating machine learning models.

DL techniques often require large amounts of labeled training data to achieve generalizable performance; a challenge mitigated through data augmentation. Augmentation techniques computationally expand and diversify datasets, improving model robustness and generalization. In this study, a range of image transformations was employed to simulate real-world variability and increase dataset complexity (Figs. 2 and 3). The augmentations included blur, noise, lightening, darkening, enhancement, and sharpening.33 The blur35 transformation was applied with varying intensities (levels 1–5), introducing controlled smoothing to reduce local pixel variation and simulate focus inconsistencies. The noise effect introduced zero-mean uniform noise with amplitude α, emulating real-world imperfections and sensor artifacts. Lightening36 and darkening37 transformations adjusted the image brightness to simulate varying illumination conditions—creating visually lightened and dimmed versions, respectively. These augmentations collectively enriched the dataset with diverse image conditions, thereby enhancing the neural networks’ capacity to generalize across a wider range of field scenarios.

To further diversify the dataset through image detail manipulation, sharpen and enhance transformations were employed.33 The sharpen function was used to increase the visual clarity of images by accentuating edges and improving focus in blurred regions. The enhance transformation applied a spatial spread parameter (σ) and a pixel value spread parameter (µ) to intensify fine details and local contrast.

In addition to pixel-level modifications, physical transformations were implemented using rotation and reflection. The rotation function altered image orientation by rotating samples counterclockwise about the center of their bounding box.38 Random rotations were applied within the intervals of –10° to –1° and 1° to 10°, thereby introducing slight angular variance while preserving semantic content. The reflect function introduced horizontal symmetry by flipping images along the vertical axis (i.e., left–right reflection).39 For the purposes of this study, only left–right reflections were included as part of the augmentation strategy.

The original dataset consisted of 433 non-augmented images of Sonchus oleraceus (annual sowthistle) and 397 images of Malva parviflora (little mallow), totaling 830 standard images. Table 2 shows the number of images present in each class corresponding to a growing condition. Through image augmentation, each original image was expanded by a factor of 28, generating 27 additional variants per image and resulting in a final dataset of 23,240 images. These images were systematically organized into training and testing sets for three neural network architectures: DenseNet-121, ResNet-101, and ResNet-50. Each model was trained and evaluated on two datasets: one comprising only the original cropped RGB images, and the other consisting of the augmented image set.

In these experiments, the dataset was randomly partitioned into stratified training and testing sets (80:20 ratio), ensuring class balance across all ten trials. Performance metrics were recorded for each trial, providing an additional perspective on model reliability.

Deep learning architectures

To evaluate the performance of deep learning models in classifying weed species under variable environmental conditions, we selected three widely adopted convolutional neural network (CNN) architectures: ResNet-50, ResNet-101, and DenseNet-121. These models represent complementary design philosophies in deep learning. ResNet-50 and ResNet-101 are part of the residual network family introduced by He et al.20, which utilize skip connections to mitigate the vanishing gradient problem and enable stable training of deeper networks. ResNet-50 offers a balance between accuracy and computational efficiency, while ResNet-101 increases model depth and representational capacity, often leading to improved classification performance in fine-grained image recognition tasks.22 Both networks have demonstrated strong results in agricultural imaging and plant species classification.18,40.

ResNet-50 is a convolutional neural network (CNN) renowned for its depth and computational efficiency. It employs a Bottleneck Residual Block, which consists of three convolutional layers: a 1 × 1 layer that reduces dimensionality, a 3 × 3 layer that captures spatial features, and a final 1 × 1 layer that restores the original channel dimension. A key innovation in ResNet-50 is the use of shortcut connections, which add the block’s input directly to its output. This residual learning mechanism facilitates the training of very deep networks by mitigating the vanishing gradient problem and preserving information flow. Through this architecture, ResNet-50 achieves high accuracy in image classification tasks while maintaining manageable computational demands41.

ResNet-101 is a deep convolutional neural network (CNN) architected for high-accuracy image classification. Central to its design are residual connections—commonly referred to as skip connections—which effectively address the vanishing gradient problem prevalent in deep neural architectures. These connections promote stable gradient propagation, thereby improving both the convergence rate and training robustness. The network comprises a series of residual blocks, each integrating convolutional layers with identity mappings, enabling enhanced feature extraction and improved recognition of complex visual patterns. Owing to this hierarchical and modular structure, ResNet-101 demonstrates strong generalization performance across a broad spectrum of image recognition tasks.22.

DenseNet-121 was selected to complement the ResNet architecture with a more compact, feature-reusing design. DenseNet24 introduces direct connections between all layers within a dense block, promoting feature propagation, reducing the number of parameters, and improving gradient flow. This architecture is known to perform well on small to moderate-sized datasets while maintaining high accuracy, making it particularly attractive for agricultural applications where data acquisition may be constrained.42 Together, these three models allow for a comprehensive comparison of residual and densely connected networks in the context of weed classification, enabling an informed assessment of architectural efficiency and generalization performance.

Model training configuration

To evaluate model performance and ensure robust generalization across weed phenotypes and stress conditions, we implemented a stratified Monte Carlo cross-validation strategy using ten independent data splits. To ensure reliable model evaluation across diverse environmental conditions, we implemented a stratified Monte Carlo cross-validation strategy with ten independent random splits. In each trial, 80% of images from each class were assigned to the training set, and 20% were held out for testing, preserving class distribution across splits.

This method was chosen over conventional k-fold cross-validation due to the limited dataset size and the presence of uneven class counts (see Table 2). Fixed k-folds can result in biased or unbalanced folds, particularly when class distributions are small or skewed. By contrast, stratified Monte Carlo sampling generates multiple random, class-balanced partitions, which reduces variance in performance estimates and mitigates the effects of atypical splits. This approach, also referred to as repeated random sub-sampling validation, has been shown to produce more stable results in small datasets with class imbalance or heterogeneity in image content.43 We adopted ten repetitions to strike a balance between computational efficiency and statistical robustness, allowing us to evaluate model performance across a range of class distributions and environmental conditions.

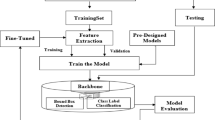

Each convolutional neural network (ResNet-50, ResNet-101 and DenseNet-121) was fine-tuned using the Wolfram Language’s NetTrain function. We replaced the final two layers of each pre-trained ImageNet model with a task-specific classification head consisting of a LinearLayer and SoftmaxLayer to distinguish among ten weed treatment classes. The training configuration included explicit control over several parameters: all convolutional layers were frozen (LearningRateMultipliers → {“linearNew” → 1, _ → 0}), a 10% validation split was reserved from the training set (ValidationSet → Scaled[0.1]), GPU acceleration was used (TargetDevice → ”GPU”), and early stopping was applied based on validation loss (TrainingStoppingCriterion → ”Loss”). Other hyperparameters — including batch size, base learning rate, and optimizer choice — were not manually tuned and were instead handled through the Wolfram Language’s internal AutoML-style pipeline, which adjusts such parameters based on dataset size, class balance, and convergence behavior44,45,46. This approach is consistent with prior machine learning workflows in the Wolfram Language47. Across the ten stratified Monte Carlo splits, training generally converged between 14 and 18 rounds, depending on class composition of each fold. Because all architectures were trained under the same configuration protocol, observed differences in performance reflect architectural and dataset effects rather than hyperparameter optimization33,34,35,36,37,38,39.

Results and discussion

Compared to existing weed detection efforts such as DeepWeeds18, which focused on broad vegetation classes in Australian rangelands, our study provides a region-specific, high-resolution image dataset targeting two morphologically similar weeds (Sonchus oleraceus and Malva parviflora) with known roles in viral disease transmission. Global repositories like PlantCLEF and LifeCLEF include diverse plant imagery but lack focused datasets under simulated agronomic conditions relevant to California’s Central Coast. The observed improvements from data augmentation (up to + 17.8% in accuracy and + 0.198 in Cohen’s Kappa for DenseNet-121) align with similar findings in weed detection literature, where geometric and photometric variation helps generalize models to real-world field scenarios. Among the tested CNNs, ResNet-101 offered the best overall accuracy–stability tradeoff, while DenseNet-121 provided the highest F1 and AUC scores in some stress classes. Limitations of this study include the use of controlled greenhouse imagery, which, although varied in treatment conditions, does not fully capture the complexity of open-field environments such as occlusions, shadows, or soil/crop backgrounds. Additionally, the dataset was limited to two weed species, albeit highly relevant to INSV. Although data augmentation substantially improved model performance, this improvement may result from both increased feature diversity and the enlarged dataset size. The augmentation process expanded the dataset by approximately twenty-eight-fold, which could reduce overfitting but may also mask the effect of true feature enrichment. Because augmentation increases both variability and total sample count, disentangling their relative contributions would require a larger base dataset or controlled augmentation ablation experiments. However, expanding the dataset further is constrained by the seasonal and logistical limitations inherent to agricultural research. Future work will explore incremental dataset growth and hybrid augmentation–synthesis methods to isolate these effects.

The use of pretrained models limits architectural customization, and the fixed augmentation strategy, while diverse, may not fully simulate all real-world perturbations.

Future directions include: (1) expanding the dataset to include additional weed species prevalent in California lettuce fields, (2) testing object detection frameworks (e.g., YOLOv5, EfficientDet) for in-situ plant localization, (3) exploring transformer-based or EfficientNet-based classifiers for improved performance–efficiency balance, and (4) deploying trained models on robotic or drone platforms for in-field real-time weed identification. The next few subsections detail the results of commonly used metrics in machine learning to quantify model performance.

Each neural network was trained to classify ten image classes, representing different environmental stress conditions applied to Sonchus oleraceus and Malva parviflora. The performance of each model was evaluated using standard classification metrics, as described in the following subsections. The original dataset consisted of 433 images of annual sowthistle and 397 images of little mallow. After applying augmentation strategies designed to simulate field variability, the dataset expanded to 23,240 images. To assess the impact of augmentation, all three neural networks—ResNet-50, ResNet-101, and DenseNet-121—were trained separately on both the original and augmented datasets. For each configuration, model evaluation was performed using ten independent stratified train-test splits to ensure a robust comparison across all metrics.

Accuracy

Accuracy is a standard performance metric that quantifies the proportion of correctly classified instances relative to the total number of predictions. While often used as a general indicator of classifier performance, it does not account for class imbalance or the distribution of errors. Classification accuracy across 10 independent data splits is shown in Fig. 4. All three convolutional neural networks, DenseNet-121, ResNet-50, and ResNet-101, exhibited substantial performance gains when trained on augmented datasets. The largest relative improvement was observed for DenseNet-121, where augmentation increased mean accuracy from 0.64 to 0.81 (a 26.6% gain). ResNet-101 and ResNet-50 showed smaller but consistent improvements of 18.5% and 17.2%, respectively. Among the augmented models, ResNet-101 achieved the highest median accuracy with minimal variability, while DenseNet-121 without augmentation had both the lowest accuracy and highest variance.

Classification accuracy across 10 independent data splits for three convolutional neural networks trained on augmented and unaugmented weed image datasets. Data augmentation significantly improves accuracy across all architectures. ResNet-101 with augmentation achieved the highest median accuracy, while DenseNet-121 showed the greatest sensitivity to augmentation.

Mean cross entropy

Mean cross entropy values across 10 independent splits are presented in Fig. 5. Models trained on augmented datasets consistently exhibited lower entropy, indicating more confident and better-calibrated predictions. DenseNet-121 trained without augmentation showed the highest average entropy (~ 1.17), suggesting frequent low-confidence predictions or misclassifications. In contrast, ResNet-101 and ResNet-50 with augmentation achieved the lowest mean entropy values (~ 0.48 and ~ 0.52, respectively), consistent with their superior classification accuracy. These results reinforce the role of data augmentation not only in improving accuracy but also in enhancing the reliability of class probability estimates.

Mean cross entropy across 10 independent data splits for each neural network trained on augmented and unaugmented weed image datasets. Models trained on augmented data consistently exhibited lower entropy, reflecting more confident and well-calibrated predictions. DenseNet-121 showed the highest entropy in the unaugmented regime, suggesting overfitting and unreliable output probabilities.

F1 score

The F1 Score is a standard metric used to assess the balance between precision and recall, particularly in binary classification contexts. It is defined as the harmonic mean of precision and recall, with values approaching 1 indicating high classification performance. In this study, F1 Scores were computed for both non-augmented and augmented image datasets across all neural network models evaluated. Specifically, Fig. 6 presents the F1 Scores for the augmented dataset across ten image classes for DenseNet-121(a), ResNet-101 (b), and ResNet-50 (c). F1 scores were computed across ten independent train-test splits using the augmented image dataset to evaluate the classification performance of each convolutional neural network. All three models: ResNet-50, ResNet-101, and DenseNet-121, demonstrated strong F1 scores, indicating effective identification of Sonchus oleraceus and Malva parviflora despite their morphological similarity. DenseNet-121 achieved the highest median F1 score with the least variability across splits, reflecting superior generalization and classification consistency. ResNet-101 also maintained high F1 scores but showed slightly greater variance. ResNet-50, while performing well overall, exhibited comparatively lower F1 scores in several splits, suggesting reduced robustness under certain training conditions. These results highlight the benefit of deeper or more densely connected architectures and emphasize the critical role of image augmentation in enhancing model performance and reliability.

F1 scores for the augmented 10 image classes across three neural networks: (a) DenseNet-121, (b) ResNet-101, and (c) ResNet-50. All models show strong class-level performance, particularly for high-fertility and drought conditions. ResNet-101 achieves the most consistent F1 scores across classes, while DenseNet-121 exhibits slightly more variability, especially for the overwatered (OS) and injured (IS) sowthistle classes. These results highlight the class-specific predictive strengths of each architecture when trained with data augmentation.

Area under ROC curve

The discrimination capabilities of various models were further quantified by computing the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC) for each class under all treatment conditions. AUC is a threshold-independent metric that quantifies a classifier’s ability to distinguish between classes; values closer to 1.0 indicate better separability. This metric is particularly useful when evaluating performance on imbalanced or noisy datasets, as it reflects the trade-off between true positive and false positive rates across varying thresholds. Figure 7 highlights the spread of 10 AUC values for each NN with the augmented data set of weeds images. ResNet-50 achieved high AUC scores across all classes, with medians generally exceeding 0.98. Despite this strong average performance, certain conditions—particularly injured sowthistle (IS) and standard sowthistle (SS)—exhibited wider interquartile ranges and lower whisker values approaching 0.92, indicating greater variability in classification confidence across splits. This suggests that the ResNet-50 model is somewhat sensitive to visual perturbations introduced by injury or environmental noise. ResNet-101 showed improved stability across splits, with AUC medians consistently near or above 0.99 for most classes. The model demonstrated reduced variance, particularly in standard and nutrient-stressed treatments. Although slight dispersion was observed in injured samples (IM and IS), AUC values remained high overall, confirming the model’s robust performance across a wider range of morphological conditions. DenseNet-121 exhibited the most consistent and highest AUC values among the three models. Nearly all treatment conditions yielded tightly clustered AUC distributions with medians at or above 0.99. The model maintained strong separability even in the most variable classes, including injured sowthistle and drought-stressed mallow. These results confirm DenseNet-121’s superior generalization capacity and stability when applied to augmented datasets featuring real-world variability.

Area under the ROC curve (AUC) for each class across 10 independent training/testing splits using (left) DenseNet-121, (middle) ResNet-101, and (right) ResNet-50, all trained on augmented weed image datasets. All three models achieved excellent AUC values across most classes, with median scores consistently above 0.96. ResNet-101 displayed the most stable and uniformly high discrimination performance, while DenseNet-121 exhibited slightly more variation for the injured (IS) and standard mallow (SM) classes. These results align with the F1 score trends and reinforce the effectiveness of data augmentation in enhancing model generalization and separability.

Cohen’s kappa

Cohen’s Kappa was computed to evaluate the agreement between predicted and true class labels while adjusting for chance. Unlike raw accuracy, which may be inflated in imbalanced datasets, Cohen’s Kappa provides a more robust assessment of model reliability by quantifying the extent of classifier agreement beyond random chance. Values range from -1 (complete disagreement) to 1 (perfect agreement), with values above 0.80 typically interpreted as strong agreement.

As shown in Fig. 8, all three CNNs achieved Kappa values consistent with substantial to near-perfect agreement. ResNet-101 attained the highest median Kappa value, approaching 0.87, with minimal interquartile variability, indicating both high predictive accuracy and consistency across splits. ResNet-50 followed closely with a slightly lower median but comparably tight variance, reflecting stable performance. DenseNet-121, while performing strongly in terms of AUC and F1 scores, exhibited greater variability in Kappa values, with a median near 0.79 and a broader interquartile range. This discrepancy may reflect increased sensitivity to class-specific imbalances or outlier effects in certain splits. Overall, Cohen’s Kappa results support the conclusion that ResNet-101 provides the most consistently reliable classification, while DenseNet-121 offers high discriminative power with some trade-off in agreement robustness.

Cohen’s Kappa values across 10 independent training/testing splits for each model trained on augmented data. All models demonstrate substantial inter-label agreement (Kappa > 0.75), with ResNet-101 achieving the most consistent performance. These values support the reliability of model predictions beyond chance agreement.

While this study employed widely used convolutional backbones (ResNet-50, ResNet-101, DenseNet-121), future work will explore more recent architectures that offer improvements in both computational efficiency and accuracy. EfficientNet48 has demonstrated state-of-the-art performance with fewer parameters through compound scaling of depth, width, and resolution. Similarly, attention-based architectures such as the Vision Transformer49 (ViT) enable global feature interactions that may improve performance on morphologically similar weed species. For tasks involving spatial localization or mapping, segmentation networks like U-Net50 or DeepLabV3 + 51 can provide pixel-level identification of weeds, which is critical for real-time precision spraying or autonomous navigation.

Conclusion

This study employed a total of 23,240 images of Sonchus oleraceus (annual sowthistle) and Malva parviflora (little mallow), generated through extensive augmentation of an initial dataset comprising 830 images. Augmentation techniques were designed to emulate real-world field conditions, thereby enriching the dataset’s variability and representativeness. This enhanced dataset served as a robust foundation for evaluating the efficacy of deep learning in weed identification. Three convolutional neural networks, DenseNet-121, ResNet-101, and ResNet-50 were trained and tested using the Wolfram Language, with performance assessed across both non-augmented and augmented datasets. Results indicated superior model accuracy and reliability on the augmented dataset, corroborating established principles that link dataset size and diversity to improved generalization in machine learning.

This study demonstrates the effectiveness of deep learning models in the classification of regionally significant weed species, Sonchus oleraceus and Malva parviflora, under simulated field conditions. Through the creation of a highly augmented and context-specific image dataset, we captured morphological variability reflective of real-world agricultural environments in coastal California. Comparative evaluation of three convolutional neural networks, DenseNet-121, ResNet-101, and ResNet-50 revealed that all models benefitted from dataset augmentation, with marked improvements in accuracy, F1 score, and AUC values. DenseNet-121 achieved the highest classification performance overall, particularly in terms of discriminative ability across complex treatment conditions. ResNet-101, while slightly lower in discriminative metrics, exhibited the highest Cohen’s Kappa, indicating strong agreement with ground truth across splits and high prediction consistency.

These results support the integration of CNN-based image classification into automated weed identification pipelines for precision agriculture Notably, this study presents the first curated image dataset focused on weed species endemic to the Monterey County region, where Sonchus oleraceus and Malva parviflora play a significant role in crop loss and disease transmission. The dataset and methods developed here offer a foundation for future efforts by researchers, agronomists, and agricultural technology developers seeking to build localized detection tools or integrate weed classification into broader disease risk management systems. In future work, we will expand the dataset to include additional species, test object detection frameworks for plant localization, and transition toward in-field validation using mobile or aerial robotic platforms. We also plan to explore more recent deep learning backbones and segmentation-based architectures to improve accuracy and efficiency in more complex deployment environments.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Hu, K. et al. Deep learning techniques for in-crop weed identification: A review. Precis. Agri. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-023-10073-1 (2021).

Johnson -, B. Weed Control Eort Seeks to Curb Virus Threat for Salinas Valley’s Lettuce. (2024).

Weeds as reservoir for Impatiens Necrotic Spot Virus (INSV) - UC Weed Science - ANR Blogs.

Manalil, S., Haider Ali, H. & Singh Chauhan, B. Interference of annual sowthistle (Sonchus oleraceus) in wheat. Source Weed Sci. 68, 98–103 (2020).

Weeds as reservoir for Impatiens Necrotic Spot Virus (INSV) - UC Weed Science - ANR Blogs.

2017 International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communications and Informatics (ICACCI) : 13–16 Sept. 2017. (IEEE, 2017).

Visentin, F. et al. A mixed-autonomous robotic platform for intra-row and inter-row weed removal for precision agriculture. Comput. Electron Agric. 214, 108270 (2023).

Wu, Z., Chen, Y., Zhao, B., Kang, X. & Ding, Y. Review of weed detection methods based on computer vision. Sensors. 21, 647. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21113647 (2021).

Champ, J. et al. Instance segmentation for the fine detection of crop and weed plants by precision agricultural robots. Appl Plant Sci 8, e11373 (2020).

Chen, M. W., Chang, M. S., Mao, Y., Hu, S. & Kung, C. C. Machine learning in the evaluation and prediction models of biochar application: A review. Sci. Progr. 106, 842. https://doi.org/10.1177/00368504221148842 (2023).

Peña-Guerrero, J., Nguewa, P. A. & García-Sosa, A. T. Machine learning, artificial intelligence, and data science breaking into drug design and neglected diseases. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Comput Mol Sci 15, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcms.1513 (2021).

Jørgensen, P. B. et al. Machine learning-based screening of complex molecules for polymer solar cells. J. Chem. Phys. 148, 210 (2018).

Sharma, A. K. Laboratory glassware identification: Supervised machine learning example for science students. J. Computat. Sci. Edu. 12, 8–15 (2021).

Sharma, A. K. et al. Machine learning to identify structural motifs in asphaltenes. Results Chem 7, 101551 (2024).

Zieliski, B., Sroka-Oleksiak, A., Rymarczyk, D., Piekarczyk, A. & Brzychczy-Woch, M. Deep learning approach to describe and classify fungi microscopic images. PLoS One 15, e0234806 (2020).

Shoaib, M. et al. Deep learning for plant bioinformatics: an explainable gradient-based approach for disease detection. Front. Plant Sci 14, 1283235 (2023).

Goeau, H., Bonnet, P. & Joly, A. Overview of PlantCLEF 2022: Image-based plant identification at global scale. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2509.17632 (2025).

Olsen, A. et al. DeepWeeds: A multiclass weed species image dataset for deep learning. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–12 (2019).

Rawat, W. & Wang, Z. deep convolutional neural networks for image classification: A comprehensive review. Neural Comput 29, 2352–2449 (2017).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. in 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 770–778 (IEEE, 2016). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2016.90.

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. in 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) vols 2016-Decem 770–778 (IEEE, 2016).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. (2015).

Wolfram-Research. ResNet-101 - Wolfram Neural Net Repository. https://resources.wolframcloud.com/NeuralNetRepository/resources/ResNet-101-Trained-on-ImageNet-Competition-Data.

Huang, G., Liu, Z., Van Der Maaten, L. & Weinberger, K. Q. Densely Connected Convolutional Networks. in 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 2261–2269 (IEEE, 2017). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2017.243.

DenseNet-121 - Wolfram Neural Net Repository. https://resources.wolframcloud.com/NeuralNetRepository/resources/DenseNet-121-Trained-on-ImageNet-Competition-Data/.

Bonnet, P., Amap, U., Goëau, H., Lu, C. & Picek, L. Plant Recognition by AI: Deep Neural Nets, Transformers, and KNN in Deep Embeddings.

Shoaib, M. et al. An advanced deep learning models-based plant disease detection: A review of recent research. Frontiers in Plant Science vol. 14 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2023.1158933 (2023).

Al-Badri, A. H. et al. Classification of weed using machine learning techniques: a review—challenges, current and future potential techniques. Journal of Plant Diseases and Protection vol. 129 745–768 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1007/s41348-022-00612-9 (2022).

Wolfram-Research. ResNet-50 - Wolfram Neural Net Repository. https://resources.wolframcloud.com/NeuralNetRepository/resources/ResNet-50-Trained-on-ImageNet-Competition-Data/.

Shorten, C. & Khoshgoftaar, T. M. A survey on image data augmentation for deep learning. J Big Data 6, 1–48 (2019).

Yang, S. R., Yang, H. C., Shen, F. R. & Zhao, J. Image data augmentation for deep learning: A survey. Ruan Jian Xue Bao/J. Softw. 36, 1390–1412 (2022).

Lébl, M., Šroubek, F. & Flusser, J. Impact of Image Blur on Classification and Augmentation of Deep Convolutional Networks. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics) 13886 LNCS, 108–117 (2023).

ImageEffect: Apply preset effect to an image—Wolfram Documentation. https://reference.wolfram.com/language/ref/ImageEffect.html.

Wolfram, S. What We’ve built Is a computational language (and that’s very important!). Journal of Computational Science vol. 46 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocs.2020.101132 (2020).

Blur: Defocus an image—Wolfram Documentation. https://reference.wolfram.com/language/ref/Blur.html.

Lighter: Increase image brightness—Wolfram Documentation. https://reference.wolfram.com/language/ref/Lighter.html.

Darker: Reduce image brightness—Wolfram Documentation. https://reference.wolfram.com/language/ref/Darker.html.

ImageRotate: Rotate an image—Wolfram Documentation. https://reference.wolfram.com/language/ref/ImageRotate.html.

ImageReflect: Mirror an image—Wolfram Documentation. https://reference.wolfram.com/language/ref/ImageReflect.html.

Shoaib, M. et al. An advanced deep learning models-based plant disease detection: A review of recent research. Front Plant Sci 14, (2023).

Potrimba, P. What is ResNet-50? Roboflow Blog https://blog.roboflow.com/what-is-resnet-50/ (2024).

Zhang, J. et al. Monitoring plant diseases and pests through remote sensing technology: A review. Comput Electron Agric 165, 104943 (2019).

Xu, Y. & Goodacre, R. On splitting training and validation set: A comparative study of cross-validation, bootstrap and systematic sampling for estimating the generalization performance of supervised learning. J. Anal. Test 2, 249–262 (2018).

Kim, D., Koo, J. & Kim, U. M. A Survey on Automated Machine Learning: Problems, Methods and Frameworks. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics) 13302 LNCS, 57–70 (2022).

Wang, C., Chen, Z. & Zhou, M. AutoML from Software Engineering Perspective: Landscapes and Challenges. Proceedings - 2023 IEEE/ACM 20th International Conference on Mining Software Repositories, MSR 2023 39–51 (2023) https://doi.org/10.1109/MSR59073.2023.00019.

He, X., Zhao, K. & Chu, X. AutoML: A survey of the state-of-the-art. Knowl Based Syst 212, 106622 (2021).

Sharma, A. K., McMillan, O., Arsala, S., Gandhok, S. & Young, R. Machine learning for asphaltene polarizability: Evaluating molecular descriptors. Digital Chem. Eng. 15, 100244 (2025).

Tan, M. & Le, Q. V. EfficientNet: Rethinking Model Scaling for Convolutional Neural Networks. 36th International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML 2019 2019-June, 10691–10700 (2019).

Dosovitskiy, A. et al. An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. Preprint at https://github.com/.

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 9351, 234–241 (2015).

Chen, L. C., Zhu, Y., Papandreou, G., Schroff, F. & Adam, H. Encoder-Decoder with Atrous Separable Convolution for Semantic Image Segmentation. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics) 11211 LNCS, 833–851 (2018).

DiTomaso, J. M. & Healy, E. A. Weeds_of_California_and_Other_Western_St. vol. 3488 (UCANR Publications, 2007).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Project Award No. 2024-67022-42531 from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Arun K. Sharma: Conceptualization, Software, Validation, Resources, Project Administration, Supervision, Funding Acquisition, Writing – Review & Editing.Arun D. Jani: Conceptualization, Validation, Program Administration, Funding Acquisition.Elijah Brunnengraeber: Software, Validation, Formal Analysis, Data Curation.Jaeyun Choi: Methodology, Software, Validation, Data Curation.Ruby Fife: Software, Validation, Formal Analysis, Data Curation.Supreet Gandhok: Resources, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Visualization, Investigation, Data Curation.Katelyn Huie: Resources, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Visualization.Alyssa Beth Ilano: Resources, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Visualization.Eduardo Lopez: Software, Validation, Formal Analysis, Data Curation, Visualization, Investigation, Writing – Review & Editing.Matthew Lopez: Methodology, Software, Validation, Data Curation.Owen McMillan: Methodology, Software, Validation, Data Curation, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – Review & Editing.Alyssa Parra: Resources, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Visualization.Trevor Pollock: Investigation, Data Curation, Visualization.Dylan Woodbridge: Methodology, Software, Validation, Data Curation.Rylend Young: Software, Validation, Formal Analysis, Data Curation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent of participate

Annual sowthistle seed and little mallow were collected by coauthor Jani from naturally growing plants on commercial farms in Salinas (36°37’20.3"N 121°33’23.1"W) and Gilroy, California (37°00’12.1"N 121°31’57.2"W), respectively. Permission to collect seed from the field was given by the farm managers at both sites. Both annual sowthistle and little mallow are listed as noxious weeds by the University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources Integrated Pest Management Program. These species are not considered endangered or at risk of extinction in California. Due to the threat they pose to crops, both through direction competition for resources and as a vector for diseases, their removal from agricultural fields is a top priority for state agencies. Coauthor Jani identified both species while in the field the day that the seed was collected. Identification confirmation was based on coauthor Jani’s professional expertise and by consulting Weeds of California and other Western States by DiTomaso and Healy (2007)51. No voucher specimens were deposited in a public herbarium because the study species are designated noxious and are already widespread in the study region.

Content of publication

During the preparation of this research, the authors used GPT4o to improve its readability and language. After using the tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sharma, A.K., Jani, A.D., Brunnengraeber, E. et al. Deep learning classification of INSV-associated weeds in Monterey county using a curated RGB image dataset. Sci Rep 15, 45395 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29552-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29552-8