Abstract

This study investigates the utilization of Bayer red mud (BRM) from Shandong Xinfa Group as a partial cement replacement, with replacement levels of 0.5%, 1%, 5%, 10%, and 15% by mass. The effects of BRM incorporation on setting time, compressive strength (at 3 and 28 days), and microstructural properties were systematically evaluated. Results indicate that the addition of BRM prolongs setting times but remains within standard limits. Compressive strength remained comparable to the control group at replacement levels up to 5%, while higher substitutions (10% and 15%) led to significant reductions. Microstructural analyses with XRD, TG/DTG, and SEM revealed that BRM primarily acts as a micro-filler and nucleation site, participating partially in hydration reactions. Leachability tests (TCLP) confirmed that all heavy metal concentrations in BRM-blended mortars were below regulatory thresholds, demonstrating minimal environmental risk. The findings support the feasibility of using Xinfa BRM as a supplementary cementitious material at doses below 10%, contributing to sustainable solid waste management in the alumina industry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Red mud is the main solid waste produced by the alumina industry and is produced and stockpiled in large quantities. Making good use of red mud is important for protecting the environment and enhancing the use of industrial resources. As the global leading producer of alumina (accounting for 55% of global production), China is expected to generate approximately 107 million tonnes of red mud in 2023. However, only 10.5 million tonnes will be utilised, representing a mere 9.8% utilisation rate (down from 10% in 2022)1.The national Action Program for Comprehensive Utilization of Red Mud requires: In 2027, the new utilization rate of red mud reached 15% (about 16 million tons per year), and in 2030, it reached 25% (about 25 million tons per year)1.

Based on the alumina extraction methodology, red mud can be classified into three primary types: Bayer red mud, Sintered red mud, and Combined red mud. Among them, Bayer red mud (BRM) accounts for 70%, which is characterized by strong alkalinity, high iron content (Fe2O3 accounted for 5%~20%) and low calcium content (CaO about 2%~8%). Because of the high alkalinity and high sodium salt of BRM, it is difficult to be resourced and the traditional utilization is limited2. The red mud used in this study produced by Shandong Xinfa Aluminum Co., Ltd. is BRM. Approximately 0.8 to 1.8 tons of red mud are generated per ton of alumina produced3. The current disposal method of BRM in Xinfa Aluminum Co., Ltd. is stockpile treatment, which causes greater environmental harm.

In recent research, red mud has been utilized in the manufacturing of Portland clinker4,5,6,7,8,8, employed as a supplementary cementitious material9,10,11, and applied as an alkaline activator in alkali-activated materials (AAMs)12,13,14,15,16,17. In a related study, Maddi Anirud et al.18 explored the behavior of cement mortar when cement was proportionally replaced with red mud in the range of 0% to 20% (at 5% intervals). The results showed that the strength of mortar mixes incorporated with 10% red mud was enhanced by 26.44% and 23.68% after 7 and 28 days of maintenance, respectively, compared to ordinary cement mortar. L. Senff19 noted that as the RM content increases, the water absorption rate of mortar rises while its mechanical strength decreases. When the RM content in mortar exceeds 20%, the maximum reaction temperature of the mortar decreases. EP Manfroi et al.20 investigated the microstructure and mineral composition of cement slurries containing up to 15% dry or calcined RM. The results indicate that RM waste can replace cement in preparing cement-based composites with microstructures, mechanical properties, and moisture absorption characteristics suitable for civil engineering applications. Tang et al.21 proposed replacing fly ash with red mud in self-compacting concrete and systematically investigated the effects of red mud on the properties of fresh mortar, hardened concrete, and durability. José Marcos Ortega et al.22 analyzed the short-term effects of red mud as a clinker substitute (with a maximum blending ratio of 20%) on the pore structure, mechanical properties, and durability of mortar. The research findings indicate that compared to the reference cementitious material, the incorporation of red mud significantly refines the microstructure of mortar. While it does not adversely affect chloride ion permeability, it reduces compressive strength. Liu23 reviewed the application progress of BRM in concrete, focusing on its feasibility as a cementitious material. Research indicates that red mud enhances mechanical properties at later ages, and using sufficient quantities promotes a denser structure with reduced total porosity and smaller pore sizes. Kancir I V et al.24 investigated the synergistic effects of locally available red mud and common supplementary cementitious materials (such as fly ash, slag, calcined clay, and limestone) in cement mixtures. The results indicate that synergistic interactions among these materials enable higher levels of cement replacement without compromising the mechanical properties of the mortar. Ribeiro D V et al.25’s research indicates that non-calcined red mud can be used in mortars and concrete for non-structural applications, partially replacing cement in mixtures. Maddi Anirudh et al.26 focused on exploring the application value of red mud as a cement substitute material. Through systematic experiments, they evaluated the mechanical properties and microstructural characteristics of red mud-based cement mortars. The results indicated that mortar with a 10% red mud replacement ratio exhibited optimal performance.

However, the chemical and mineralogical composition of red mud depends to a large extent on the source of bauxite and the method of its processing23. Less research has been done on BRM from Shandong Xinfa Group Co. for direct replacement of cement cementitious materials. Table 1 compares the oxide composition of Xinfa red mud with that of cement.The chemical composition was determined using XRF testing methods. The red mud samples in the table were dried in a constant temperature oven at 105 °C for 24 h after sunlight exposure, removed and cooled naturally27. The test results showed that the iron trioxide content in red mud was much higher than that in cement, reaching 35.36%. The total amount of silicon dioxide, calcium oxide and iron trioxide reached 54.25%. The high content of ferric oxide allows the red mud to be used only as a filler without hydration reactions when replacing cementitious materials. Silicon dioxide and calcium oxide can be hydrated in the alkaline environment of red mud27,28,29.

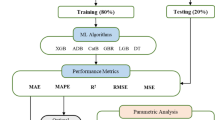

In this paper, it evaluated Xinfa BRM as a supplementary cementitious material by partially replacing cement at 0.5%, 5%, 10%, and 15% by mass. The investigation assessed its impact on setting time and compressive strength (at 3 and 28 days), alongside microstructural characteristics. X-ray diffraction (XRD) and thermogravimetric/differential thermogravimetric (TG/DTG) analyses elucidated the hydration products and reaction mechanisms associated with varying BRM levels. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) further revealed the microstructure of cement pastes incorporating BRM. Additionally, the Toxicity Characteristic Leaching Procedure (TCLP) quantified the immobilization efficacy of heavy metals within the cement matrix. Based on these findings, the feasibility of utilizing Xinfa BRM as a supplementary cementitious material is discussed, providing a theoretical basis for the resource recovery of Xinfa red mud solid waste.

Materials and methods

Materials

In the dissolution stage of the Bayer method, the alumina in the bauxite is dissolved into solution by the concentrated alkali (forming a sodium aluminate solution), while the iron, titanium, most of the silica (in the form of hydrated sodium alumino-silicate), calcium (in the form of hydrated calcium alumino-silicate or hydrated garnet), and incompletely reacted aluminium minerals in the ore, etc., form a complex solid-phase mixture that is chemically stable and insoluble in alkali under the conditions of strong alkali, high temperatures, and high pressures. Subsequently, this solid-phase residue is separated from the sodium aluminate solution in a dilution settling and multistage countercurrent washing process, and after washing to recover some of the alkali and alumina, the red mud, which needs to be stockpiled or disposed of on a large scale, is finally obtained. A schematic diagram of the alumina production process is shown in Fig. 1.

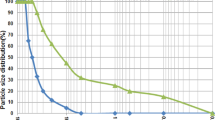

This investigation utilized BRM sourced from Liaocheng Xinfa Group Co. Following drying procedures, the material was pulverized using an FII-1000 C high-speed mill (32,000 rpm; Dongwuancheng, Guangdong, China). Particle size distribution analysis (Fig. 2 using a Malvern 3000 Laser Particle Size Analyzer) reveals the red mud exhibits both finer particle dimensions and a narrower size distribution profile compared to conventional cement. Median particle diameters (D50) were quantified at 19.5 μm for cement and 1.06 μm for red mud. Figure 3 shows the micromorphology of BRM. As can be seen in the figure, BRM is composed of very fine spherical particles with uniform particle size. The reduced particle scale facilitates two key functions within cementitious systems: (1) micro-filler behavior during matrix solidification, and (2) enhanced nucleation sites for hydration reactions. This nucleation effect anchors hydration products within the developing microstructure, ultimately improving the mechanical strength of the cured composite28. Specific surface area measurements yielded values of 393.1 m²/kg for cement versus 689.7 m²/kg for red mud. This substantial surface area differential necessitates proportionally greater water demand for effective hydration of the red mud component27.

Mixture design

Table 2 demonstrates the mortar ratios formulated using different dosages of BRM as supplementary cementitious material. The cement type used is P•O 42.5 cement. All mortar mixtures were formulated using a constant water-to-binder ratio (w/b) of 0.4. 100% pure cement was used in the control group. The BRM dosages in the BRM-OPC system were 0.5%, 1%, 5%, 10%, and 15%, respectively.

Sample Preparation and characterizations

Compressive strength

In accordance with EN 19630, mortar specimens were fabricated with the specified binder compositions (Table 2) to evaluate the development of compressive strength. A planetary mixer was employed to combine cement and water following a standardized mixing procedure: initial low-speed mixing for 120 s, a brief pause of 15 s, and subsequent high-speed mixing for an additional 120 s. The fresh mortar was then cast into 40 mm × 40 mm × 40 mm molds and consolidated using mechanical vibration for 60 s. The molds were sealed with plastic film and transferred to an environmental chamber for curing (20 ± 1 °C, 90% relative humidity). Demolding took place after 24 h, after which the specimens were returned to the same curing conditions until testing. For every mix design, six paste specimens were manufactured and their compressive strength was determined at 3-days and 28-days following ASTM C10931. Testing was performed using a Denison hydraulic testing machine (3,000 kN capacity) under a constant loading rate of 0.6 MPa/s, in compliance with GB/T 50,081 − 201932. The results presented are the average of three individual tests.

The setting time

The initial and final setting times of the cement paste were determined using a Vicat apparatus (Shanghai Luda Test Instrument Co., Ltd., China) in compliance with ISO 9597:200833. The initial setting time was recorded as the time elapsed until the needle reached a depth of 34 ± 3 mm. The final setting time was identified as the moment when the needle penetration did not exceed 0.5 mm. To ensure reproducibility, duplicate measurements were conducted at two separate locations on each sample to verify the final setting time.

XRD, TG/DTG and SEM

Following a 24-hour curing period, the mortar specimens were demolded and subsequently placed in a controlled curing environment (20 ± 1 °C, 90% relative humidity) for 28 days. To examine the hydration products and microstructural characteristics after this period, the samples were analyzed using X-ray diffraction (XRD), thermogravimetric analysis (TG/DTG), and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). To arrest hydration, the cement paste was crushed and submerged in isopropyl alcohol at the conclusion of the 28-day curing. The material was then dried in a vacuum oven at 40 °C for 24 h. A portion of the crushed samples was prepared for SEM observation by applying a gold sputter coating. The remainder was finely pulverized for XRD and TG/DTG examinations. XRD measurements were conducted on a Smart Labs 9 kW diffractometer employing Cu Kα radiation, scanning between 5° and 65° (2θ) at a rate of 5° per minute. Simultaneous TG/DTG analysis was carried out from room temperature up to 1100 °C with a constant heating rate of 10 °C per minute under a controlled atmosphere. Microstructural evaluation of the fracture surfaces was performed via scanning electron microscopy.

TCLP

The leaching behavior of heavy metals (HMs) from cement composites incorporating red mud was assessed via the Toxicity Characteristic Leaching Procedure (TCLP), following GB5085.3–200734. Samples cured for 28 days were prepared according to HJ/T 299–200735. The samples were comminuted to particles smaller than 9.5 mm and subjected to extraction using a sulfuric acid solution (pH 2.88) with a solid-liquid ratio maintained at 1:20. The mixture was rotated continuously at 30 rpm for 18 h. Following the extraction process, the leachate was passed through a 0.45 μm membrane filter and subsequently subjected to analysis by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) for the quantification of trace metal content27,28. The ICP-OES instrument was configured with an RF power of 1.15 kW, employed argon as the carrier gas, and maintained a plasma gas flow rate of 15 L/min. The target analytes—Ag, Hg, Ni, Cu, Zn, Pb, Cd, As, Ba, and Cr—were evaluated relative to the regulatory thresholds established in GB5085.3–200734. The method detection limit for ICP-OES was 0.001 mg/L, enabling precise quantification of trace heavy metals. All extractions and measurements were performed in triplicate to ensure reproducibility, and mean values are reported.

Results

Setting times

It shows the setting times of cement paste with different BRM content in Table 3. As shown in the table, the higher the BRM content, the longer the setting time. The addition of BRM prolongs the setting time of cement. The initial setting time of cement paste with 15% BRM is 50 min longer than that of pure cement, and the final setting time is 81 min longer. BRM generally prolongs the setting time of cementitious materials, primarily due to its high alkalinity, low reactivity, and adsorption properties36,37. The high alkalinity of BRM slows down the formation of initial hydration products in cement and inhibits the hydration reaction rate of C3S (tricalcium silicate). The abundant Fe2O3, Al2O3, and quartz phases in BRM have low hydration activity at room temperature and cannot effectively participate in early hydration reactions, thereby diluting the active components of cement. The porous surface of BRM particles may adsorb water molecules and Ca2+ions, reducing the free water and ion concentration around cement particles available for hydration. According to GB/T 175–2007 ‘Common Portland Cement’38, the initial setting time of Portland cement must be greater than 45 minutes, while the final setting time should be no more than 600 minutes. In this study, the setting times of cement with different BRM dosages all comply with the specifications.

Compressive strengths

Figure 4 shows the development of compressive strength for samples containing different proportions of BRM. As shown in the figure, when the BRM dosage was 0.5%, 1%, and 5%, the 3-day and 28-day compressive strengths were comparable to those of the control group. At a dosage of 10%, the 3-day and 28-day compressive strengths decreased by 27.5% and 22.3%, respectively. At a dosage of 15%, the 3-day and 28-day compressive strengths decreased by 28.1% and 23.7%, respectively. The variability in 28-day compressive strength was significant for pure cement and mixes with 1%, 10%, and 15% BRM. The analysis results indicate that when the BRM content is below 5%, the micro-filling effect enhances the compressive strength of the cementitious material, with superior long-term structural performance (28 days). The microfilling effect resulted in the 28-day compressive strength of the 1% BRM-modified mixture being slightly higher than that of the 0.5% modified mixture. However, the effectiveness of this effect diminished at higher modification levels. When a small amount of BRM is added, the material strength is comparable to that of RM-free mortar. However, high BRM content significantly reduces compressive strength and adversely affects the structural serviceability. Reference18 indicates that mixtures containing 10% red mud showed strength increases of 26.44% and 23.68% after 7 and 28 days of curing, respectively. The alkalinity of red mud promotes favorable pozzolanic reactivity, while its high specific surface area plays a crucial role in cement hydration. During cement hydration, excess aluminum oxide, silicon dioxide, and titanium dioxide in red mud react with chemical substances, thereby enhancing concrete strength20. For Xinfa red mud, this phenomenon is only evident at a 1% admixture ratio. Senff et al.19 noted that the mechanical strength of mortar decreases with increasing red mud content. Manfroi et al.20 also observed a decline in compressive strength at higher red mud contents in mortar, suggesting that from a mechanical performance perspective, the optimal red mud replacement rate should be controlled below 5%. Nikbin et al.39 studied red mud lightweight concrete and found that compressive strength decreased with increasing red mud content—specimens containing 25% red mud exhibited approximately 29.5% lower 28-day compressive strength than the reference concrete. These findings are consistent with the results of this study.

Hydration products

It investigate the influence of varying Bayer red mud (BRM) concentrations on the phase composition of hydration products in cement paste with X-ray diffraction (XRD). It presents the XRD spectra of pastes cured for 28 days with different BRM incorporation levels in Fig. 5. The dominant crystalline phases identified include Portlandite (Ca(OH)2), ettringite (AFt), Calcite (CaCO3), and Gypsum(CaSO4•2H2O). This is similar to the results in Reference20. X-ray diffraction analysis results also indicate no significant difference between red mud-blended and pure cement mortar, suggesting that red mud addition does not alter the product type. This is because cement additives in the mixture undergo hydration reactions to form hydrates such as C-S-H/C-A-S-H and Aft gel, regardless of red mud inclusion40.

Quantitative analysis of hydration products was conducted based on thermogravimetric (TG) and derivative thermogravimetric (DTG) measurements. Figure 6 displays the TG and DTG curves for OPC and cement pastes incorporating varying amounts of BRM, measured with a Hitachi STA200 simultaneous thermal analyzer. As shown in the figure, both the reference OPC and the BRM-modified cement mortars after 28 days of curing exhibit comparable thermal curve profiles, each displaying four characteristic endothermic peaks. The DTG curves indicate four major decomposition events: the first peak (80–100 °C) is attributed to the loss of bound water from C–S–H gel and calcium aluminate hydrate phases; the second peak (160–190 °C) corresponds to the dehydration of monosulfoaluminate (AFm); the third event (400–450 °C) reflects the dehydroxylation of portlandite (Ca(OH)2); and the fourth peak (650–720 °C) signifies the decarbonation of calcite (CaCO3). This is consistent with the findings of Reference24. A decrease in calcium-containing phases was observed with increasing BRM content, consistent with XRD findings. The similarity in thermal decomposition behavior between BRM-blended mortars and the pure OPC mortar suggests comparable degrees of hydration, which correlates well with the consistent 28-day compressive strength results across all mixtures.

Microstructure

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to investigate the surface morphology of cement pastes incorporating varying amounts of BRM, with a focus on the analysis of hydration products and pore structure. Figure 7 shows the microscopic structural comparison images of BRM-modified specimens at 28 days of age. As shown in the figure, C-S-H gel, Ca(OH)2, and calcite are the main hydration products, which are consistent with the results of X-ray diffraction (XRD) and thermogravimetric (TG) analysis. As shown in the figure, a higher BRM dosage leads to increased porosity of the structure, resulting in reduced compressive strength. Red mud, with its strong alkalinity and hydrolytic action, promotes the formation of additional cementitious materials such as C-S-H/C-A-S-H and calcium aluminate hydrate. These hydration products, along with fine particles and aggregates from the red mud, can adhere to particle surfaces or fill intergranular pores, thereby forming a more compact and stable soil structure40. In the micromorphology of BRM-1, the micro-aggregate filling effect of BRM can be clearly observed, which contributes to the structural strength40. Reference22 indicates that compared to standard cementitious materials, the incorporation of red mud results in a more compact microstructure of the mortar, with this effect being more pronounced at a 1% addition rate of Xinfa red mud.

Environmental properties

The raw BRM used in this study contains varying concentrations of metallic (metalloid) elements, with specific data detailed in Table 4. Research indicates that arsenic (As) and chromium (Cr) are the most abundant elements in red mud, while zinc (Zn) and barium (Ba) are the most prevalent elements in red mud-based cementitious materials. Furthermore, TCLP results indicated that the leachability of all target metals (and metalloids) was significantly lower than the regulatory limits established by TCLP standards. The corresponding leachable concentrations of heavy metals in cement mortar specimens with varying BRM contents are provided in Table 4. For mortar samples containing different BRM content levels, the leaching concentrations of all metals (metalloids) are below both the TCLP standards and the limits specified in GB 5085.3–200734. The enhancement of specific diffraction peaks in the XRD pattern indicates that heavy metal ions participate in the formation of hydration products. They may enter the C-S-H gel lattice via isomorphous substitution or form insoluble heavy metal hydroxide/silicate precipitates. The specific microstructures observed in SEM images, including a denser matrix and uniform distribution of heavy metal elements within the C-S-H gel, indicate that as hydration progresses, hydration products such as C-S-H gel and AFt encapsulate heavy metal compounds, isolating them from the external environment and thereby reducing their leaching risk. Simultaneously, the high specific surface area of red mud itself and the enormous specific surface area of the cement hydration product C-S-H gel exert a strong physical/chemical adsorption effect on heavy metal ions. The metals (metalloids) leached from the mortar specimens are effectively solidified, indicating that after the hydration of the cementitious materials, the metals (metalloids) are firmly bound, posing minimal environmental hazards20,27,28,36. Therefore, cement mortar prepared using a certain amount of BRM does not pose environmental or health risks.

Discussions

After mixing cement and BRM with water, C3S (tricalcium silicate), C3A (tricalcium aluminate), and C4AF (tetracalcium aluminoferrite) hydrate rapidly, while gypsum dissolves quickly to form a saturated solution of Ca(OH)2 and CaSO4. The hydration products initially include hexagonal plate-like Ca(OH)2 and needle-shaped AFt phase (3CaO•Al2O3•3CaSO4•32H2O), andamorphous C-S-H (calcium silicate hydrate). Subsequently, as SO42−continues to decrease due to the ongoing formation of AFt phase, the AFm phase, C-A-H crystals, and C4•(A•F)H13 crystals subsequently form. This is consistent with the results of the XRD, TG/DTG, and SEM analyses described earlier. The chemical reactions are as follows:

\(\begin{gathered} {\text{3CaO}}\cdot {\text{Si}}{{\text{O}}_{\text{2}}}{\text{+n}}{{\text{H}}_{\text{2}}}{\text{O=xCaO}}\cdot {\text{Si}}{{\text{O}}_{\text{2}}}\cdot {\text{y}}{{\text{H}}_{\text{2}}}{\text{O+(3-x)Ca(OH}}{{\text{)}}_{\text{2}}} \hfill \\ {\text{2(3CaO}}\cdot {\text{A}}{{\text{l}}_{\text{2}}}{{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}}{\text{)+27}}{{\text{H}}_{\text{2}}}{\text{O=4CaO}}\cdot {\text{A}}{{\text{l}}_{\text{2}}}{{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}}\cdot {\text{19}}{{\text{H}}_{\text{2}}}{\text{O+2CaO}}\cdot {\text{A}}{{\text{l}}_{\text{2}}}{{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}}\cdot {\text{8}}{{\text{H}}_{\text{2}}}{\text{O}} \hfill \\ {\text{4CaO}}\cdot {\text{A}}{{\text{l}}_{\text{2}}}{{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}}\cdot {\text{F}}{{\text{e}}_{\text{2}}}{{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}}{\text{+4Ca(OH}}{{\text{)}}_{\text{2}}}{\text{+22}}{{\text{H}}_{\text{2}}}{\text{O=2(4CaO}}\cdot ({\text{A}}{{\text{l}}_{\text{2}}}{{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}},{\text{F}}{{\text{e}}_{\text{2}}}{{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}}){\text{)}}\cdot {\text{13}}{{\text{H}}_{\text{2}}}{\text{O}} \hfill \\ \end{gathered}\)

During the hydration process of C3A, when sufficient gypsum is present, the following reaction occurs:

\({\text{3CaO}}\cdot {\text{A}}{{\text{l}}_{\text{2}}}{{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}}{\text{+3(CaS}}{{\text{O}}_4}\cdot 2{{\text{H}}_{\text{2}}}{\text{O)+26}}{{\text{H}}_{\text{2}}}{\text{O=3CaO}}\cdot {\text{A}}{{\text{l}}_{\text{2}}}{{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}}\cdot 3{\text{CaS}}{{\text{O}}_4}\cdot {\text{32}}{{\text{H}}_{\text{2}}}{\text{O}}\)

Among them, \({\text{CaO}}\cdot {\text{A}}{{\text{l}}_{\text{2}}}{{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}}\cdot 3{\text{CaS}}{{\text{O}}_4}\cdot {\text{32}}{{\text{H}}_{\text{2}}}{\text{O}}\)is known as trisulfoaluminate hydrate (AFt), also called ettringite. During the hydration of C3A, the formation of 4CaO•Al2O3•19H2O may lose its crystal water under relative humidity below 85%, converting to 4CaO•Al2O3•13H2O. When C3A is not fully hydrated while gypsum is depleted, the resulting 4CaO•Al2O3•13H2O reacts with previously formed AFt as follows:

\({\text{3CaO}}\cdot {\text{A}}{{\text{l}}_{\text{2}}}{{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}}\cdot {\text{3CaS}}{{\text{O}}_4}\cdot {\text{32}}{{\text{H}}_{\text{2}}}{\text{O+2(4CaO}}\cdot {\text{A}}{{\text{l}}_{\text{2}}}{{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}}\cdot 19{{\text{H}}_{\text{2}}}{\text{O)=3(3CaO}}\cdot {\text{A}}{{\text{l}}_{\text{2}}}{{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}}\cdot {\text{CaS}}{{\text{O}}_4}\cdot {\text{12}}{{\text{H}}_{\text{2}}}{\text{O)+2Ca(OH}}{{\text{)}}_2}+{\text{20}}{{\text{H}}_{\text{2}}}{\text{O}}\) Among these, \({\text{3CaO}}\cdot {\text{A}}{{\text{l}}_{\text{2}}}{{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}}\cdot {\text{CaS}}{{\text{O}}_4}\cdot {\text{12}}{{\text{H}}_{\text{2}}}{\text{O}}\) is referred to as monosulfoaluminate hydrate (AFm). The hydration products of cement with varying BRM dosages primarily consist of C-S-H gel, Ca(OH)2, AFt, and AFm. The C-S-H gel exhibits an amorphous colloidal form with poor crystallinity; Ca(OH)2 maintains the alkalinity of the cement paste system, stabilizing the C-S-H gel; AFt possesses a needle-like or rod-like structure, which promotes structural connectivity among red mud aggregates during its formation and growth; AFm appears as hexagonal platelets or irregular flower-like crystals with relatively high crystallinity.

With further development, the long fibrous C-S-H crystals and AFt crystals become increasingly interlaced within the cement paste, gradually forming a network-like structure. This three-dimensional mesh, formed by the interconnection of hydrate crystals, interlaces and anchors onto red mud particles, creating a dense and robust integrated system. During this process, porosity significantly decreases, the network structure continues to densify, and strength progressively increases.

Conclusion

This study investigates the feasibility of utilizing BRM from Liaocheng Xinfa Group as a partial cement replacement. By incorporating it into cement at appropriate ratios, the mechanism and application potential of high-iron-content BRM as a partial cement replacement were examined. The research further compares the functional mechanisms and application prospects of BRM as a cement admixture, leading to the following conclusions:

(1) The incorporation of BRM prolongs the setting time of cementitious materials. Within 20% dosage, the setting time of cement complies with standard GB 175–2007 requirements.

(2) The compressive strength of cement with less than 5% BRM dosage is comparable to that of the control cement at both 3-day and 28-day ages. When the BRM dosage exceeds 10%, the compressive strength decreases with increasing dosage.

(3) Mortars with different BRM dosages exhibit identical hydration products at 28 days of curing. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis indicates that their crystalline phases and chemical compositions include portlandite, ettringite, calcite, and gypsum. Thermogravimetric-differential thermogravimetric (TG-DTG) analysis indicates four exothermic peaks corresponding to calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) and ettringite (AFt), monosulfoaluminate (AFm), calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)2), and calcium carbonate (CaCO3). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) observations demonstrate that higher BRM dosages result in increased porosity of the structure. Hydration and microstructural analyses indicate that RBM partially participates in the hydration reaction while also acting as a filler material within the pores of the cement mortar.

(4) For mortar samples incorporating different dosages of BRM, the heavy metal leaching concentrations were lower than the limits specified by both the TCLP standard and GB 5085.3–2007. Hydration reactions contribute to the solidification of heavy metal elements within the samples. Mortar samples with low BRM dosages do not pose environmental hazards.

(5) The high-iron BRM produced by Liaocheng Xinfa Group during alumina production can be used as a partial cement replacement when the dosage is below 10%.

(6) This study confirms that by precisely controlling the red mud dosage, its high alkalinity can be transformed from a ‘processing challenge’ into a ‘chemically activated resource.’ This enables the large-scale resource utilization of red mud while ensuring adequate mechanical properties. However, the research only conducted short-term mechanical property tests in the laboratory. Its long-term durability (such as resistance to carbonation and alkali-aggregate reaction) and feasibility for application in large-scale engineering projects require further validation.

Data availability

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

References

Action Program on Comprehensive Utilization of Red Mud, Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT)(in China), 12, 31. (2024).

Ye, N. et al. Synthesis and strength optimization of one-part geopolymer based on red mud. Constr. Building Mater. 111 (may15), 317–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.02.099 (2016).

Tang, W. C. et al. Influence of red mud on mechanical and durability performance of self-compacting concrete. J. Hazar. Mat. 379(5): 120802.1-120802.9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.120802 (2019).

Tsakiridis, P. E., Agatzini-Leonardou, S. & Oustadakis, P. Red mud addition in the Raw meal for the production of Portland cement clinker. J. Hazard. Mater. 116 (1/2), 103–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2004.08.002 (2004).

Singh, M., Upadhayay, S. N. & Prasad, P. M. Preparation of special cements from red mud. Waste Manage. 16, 665–670. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0956-053X(97)00004-4 (1996).

Singh, M., Upadhayay, S. N. & Prasad, P. M. Preparation of iron rich cements using red mud. Cem. Concrete Res. 27, 1037–1046. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0008-8846(97)00101-4 (1997).

Vangelatos, I., Angelopoulos, G. N. & Boufounos, D. Utilization of ferroalumina as Raw material in the production of ordinary Portland cement. J. Hazard. Mat. 168:473–478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.02.049 (2009).

Liu, D. Y. & Wu, C. S. Stockpiling and comprehensive utilization of red mud research progress. Materials 5 (7), 1232–1246. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma5071232 (2012).

Samal, S., Ajoy, K. R. & Bandopadhyay, A. Proposal for resources, utilization and processes of red mud in India—A review. International J. mineral. Processing. 118: 43–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.minpro.2012.11.001 (2013).

Zhihua, P., Dongxu, L., Jian, Y. & Nanru, Y. Properties and microstructure of the hardened alkali-activated red mud–slag cementitious material. Cem. Concrete Res. 33, 1437–1441. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0008-8846(03)00093-0 (2003).

Zhihua, P., Yanna, Z. & Zhongzi, X. Strength development and microstructure of hardened cement paste blended with red mud. J Wuhan Univ. Technol-Mater. 24:161–165 . https://doi.org/10.1007/s11595-009-1161-1 (2009).

Kaya, K. & Soyer-Uzun, S. Evolution of structural characteristics and compressive strength in red mud-metakaolin based geopolymer systems. Ceram. Int., 42 (6): 7406–7413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2016.01.144(2016).

Pan, Z. et al. Properties and microstructure of the hardened alkali-activated red mud–slag cementitious material. Cem. Concrete Res. 33 (9), 1437–1441. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0008-8846(03)00093-0 (2003).

Yuan, B. et al. Activation of binary binder containing fly Ash and Portland cement using red mud as alkali source and its application in controlled low-strength materials. Journal Mater. Civil Engineering. 12(2), 357–361. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)mt.1943-5533.0003023 (2020).

Krivenko, P. et al. Development of alkali activated cements and concrete mixture design with high volumes of red mud. Constr. Building Mater. 151 (oct.1), 819–826. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.06.031 (2017).

Wang, Z. et al. Effective reuse of red mud as supplementary material in cemented paste backfill: durability and environmental impact. Constr. Build. Mater. 328, 127002–127009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.127002 (2022).

Nie, Q. et al. Strength properties of geopolymers derived from original and desulfurized red mud cured at ambient temperature. Construction & Building Materials, 125(OCT.30): 905–911. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.08.144 (2016).

Anirudh, M. et al. Characterization of red mud based cement mortar; mechanical and microstructure studies-ScienceDirect. Mater. Today. 43 (2), 1587–1591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.09.504 (2021).

Senff, L. & Hotza, Labrincha, J. A. Effect of red mud addition on the rheological behaviour and on hardened state characteristics of cement mortars. Construction & Building Materials. 25(1):163–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2010.06.043 (2011).

Manfroi, E. P., Cheriaf, M. & Rocha, J. C. Microstructure, mineralogy and environmental evaluation of cementitious composites produced with red mud waste. Construction & Building Materials, 67(pt.a):29–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.10.031 (2014).

Tang, W. C. et al. Influence of red mud on mechanical and durability performance of self- compacting concrete. J. Hazard. Mater. 379 (5), 120802.1-120802.9 (2019).

José, M. O. et al. Effects of red mud addition in the microstructure, durability and mechanical performance of cement mortars. Appl. Sci. 9(984), 2–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9050984 (2019).

Liu, Q. Advancements in the use of bayer red mud as a sustainable cementitious material in concrete: challenges and opportunities. Adv. Res. 26 (1), 167–174. https://doi.org/10.9734/air/2025/v26i11244 (2025).

Kancir, I. V. & Serdar, M. Contribution to Understanding of synergy between red mud and common supplementary cementitious materials. Materials 15 (5), 1968. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15051968 (2022).

Ribeiro, D. V., Labrincha, J. A. & Raymundo, M. M. Potential use of natural red mud as Pozzolan for Portland cement. Mater. Res. 14 (1), 60–66. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1516-14392011005000001 (2011).

Anirudh, M. et al. Characterization of red mud based cement mortar; mechanical and microstructure studies - ScienceDirect. Materials Today: Proceedings. 9(504): 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.09.504 (2020).

Gu, H. et al. Utilization of high iron content sludge and Ash as partial substitutes for Portland cement. Mater. (1996 – 1944). 18 (10), 2–12. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18102309 (2025).

Gu, H. et al. Investigations into replacing calcined clay with sewage sludge Ash in limestone calcined clay cement (LC3) (1996-1944). Materials, 18, 2–16. (2025).

Kriskova, L. et al. Alkali-activated mineral residues in construction: case studies on bauxite residue and steel slag pavement tiles. Materials 18, 257. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18020257 (2025).

EN 196-1:2016; Methods of testing cement—Part 1: determination of strength. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium. (2016).

ASTM C109. Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Hydraulic Cement Mortars (Annual Book of ASTM Standards, 2016).

GB50081-2019; Standards for test methods of physical and mechanical properties of concrete, Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China. (2019).

ISO 9597. :2008; EN Cement—test methods—determination of Setting time and Soundness (ISO, 2008).

GB 5085. 3–2007; Chinese Standard: Identification Standards for Hazardous wastes-identification for Extraction Toxicity (PRC Environmental Protection Agency, 2007).

Solid waste. Extraction procedure for leaching toxicity. Sulphuric acid & nitric acid method. 299-2007. (Ministry of Environmental Protection, 2007).

Xiaoming, L. et al. Characterization on a cementitious material composed of red mud and coal industry byproducts. Constr. Build. Mater. 47 (10), 496–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.05.030 (2013).

Romano, R. C. et al. Using isothermal calorimetry, X-ray diffraction, thermogravimetry and FTIR to monitor the hydration reaction of Portland cements associated with red mud as a supplementary material. Journal Therm. Anal. Calorimetry, 137:1877–1890. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-019-08095-x(2019)

GB 175–. ; Common portland cement. Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China(2007) (2007).

Nikbin, I. M. et al. Environmental impacts and mechanical properties of lightweight concrete containing bauxite residue (red mud). J. Clean. Prod. 095–9652617328160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.11.143 (2017).

Chen, R. et al. Mechanical properties and micro-mechanism of loess roadbed filling using by-product red mud as a partial alternative. Construction Building Materials, 216(8.20):188–201 .https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.04.254(2019).

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Liaocheng University [318052355].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Funding acquisition, Visualization, H.G.; Writing—review & editing, Supervision, M.T.; Data curation, S.W.; Data Collection H.W.; Formal analysis, Writing—review & editing, Z.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gu, H., Tang, M., Wu, S. et al. Performance of cementitious composites with bayer red mud as a partial cement replacement. Sci Rep 15, 44628 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29623-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29623-w