Abstract

Nickel-based superalloys like Inconel 718 exhibit large machining challenges attributable to their poor thermal conductivity and pronounced work hardening behaviors. They normally contribute to quick tool wearing away and poor surface quality. In order to get around this problem, a hybrid deep learning system that fused a CNN and an LSTM was devised and successfully optimized through the JOA. The model was incorporated in MATLAB/Simulink, making it possible to predict surface roughness and flank wear in real-time while hard turning using a CBN tool under MQL conditions. The experimental data used for model training and validation were derived from 27 full-factorial machining trials that covered a range of cutting speeds, feed rates, and depths of cut. The data was preprocessed through normalization and outlier removal using the IQR and Z-score methods. The CNN–LSTM model that was optimized by JOA displayed remarkable prediction power with R = 0.9991, RMSE = 0.0095, and MAPE = 2.21%, thus being far superior to the conventional models, like SVM, ANN, and ANFIS, etc. The findings indicate the model’s ability to precisely understand complex nonlinear interactions between the machining parameters and the corresponding responses, hence, the model’s strong generalization across different cutting conditions. The inclusion of the MATLAB/Simulink environment extends the model’s real-time deployment potential, digital-twin compatibility, and scalability, providing a low-cost and sensor-free solution that is perfect for smart and sustainable manufacturing. This study offers a scientifically interpretable and industrially deployable method for predictive modeling in the machining of hard-to-cut materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Superalloys were originally developed around the early 20th century to address the demand for materials with the ability to withstand high-temperature creep, oxidation, and impact stresses in gas turbine hot sections. Iron–nickel superalloys were first the ones engineered from stainless steels, and then the development continued with the addition of nickel and cobalt elements1,2. Superalloys generally fall under three broad categories: nickel-based, cobalt-based, and iron–nickel-based alloys. Of these, nickel-based superalloys—mainly Inconel 718—are widely utilized in high-performance applications, i.e., aerospace, nuclear energy, and gas turbines, due to their exceptional mechanical strength, corrosion resistance, and resistance to high-temperature usage3. While nickel-based superalloys have superior performance properties, they are notoriously difficult to machine because of their limited thermal conductivity and great work hardening behaviors. Such properties are known to induce tool–material adhesion during cutting, which enhances tool wear and reduces tool life4. Due to these effects, cutting fluids are traditionally applied in machining for assisting heat dissipation, lubrication, and chip removal5,6. While efficient, classical cutting fluids have environmental and health implications as well as manufacturing costs related to their disposal and recycling7. As a more sustainable alternative, MQL has been developed over the past few years. MQL ensures better cooling efficiency with minimal amounts of fluid involved, providing a greener as well as cost-effective alternative to conventional wet machining3,8. However, certain research has shown that MQL fails to deliver adequate lubrication at times, particularly in machining high-strength alloys such as nickel-based superalloys9,10.

Machining is the process of manufacturing wherein a workpiece is shaped and sized according to specific technical requirements11,12. Out of numerous machining techniques, drilling is particularly significant in making holes with precision. Cutting performance in the drilling process is, however, often hindered by excessive heat generation and severe friction at the tool–workpiece interface. These conditions result in elevated cutting temperatures and forces, which can reduce tool life significantly and surface quality13,14. To counter these challenges, the heavy use of cutting fluids is a standard practice. This serves to reduce the temperature of the drill bit, minimize friction, increase tool life, allow better control of cutting speeds, improve surface finish, and allow efficient chip evacuation. Flood cooling with cutting fluids in industry remains widespread in drilling15. However, this practice has increasingly come under criticism due to its negative environmental implications that have become a central problem for sustainable manufacturing. As such, reducing the consumption of cutting fluids has emerged as a leading strategy to promote environmentally sound manufacturing practices. Different other methods have been researched, including dry drilling, compressed air cooling, and MQL that are currently universally applied as green machining processes. Among these, dry drilling that completely eliminates cutting fluids often faces technical problems like accelerated tool wear, heat-induced drill bit damage, and compromised workpiece surface integrity16.

In conventional machining operations, cutting fluids are typically employed to reduce the cutting temperature, friction, and force, which in turn will ultimately cut down the cost of production17,18. Conventional cutting fluids are typically categorized into two general groups: neat cutting oils and water-soluble fluids. Their principal advantages in machining are: (i) inhibition of chemical diffusion between the tool and workpiece, (ii) ease of chip evacuation from rake face, (iii) decrease in tool wear, (iv) decrease in energy consumption, and (v) prevention of corrosion on the machined surface19. However, the effectiveness of cutting fluids also focuses significantly on factors such as type of material for the workpiece, type of operation in machining, and selected cutting parameters. Different cooling techniques are applied in conventional systems, including flooding using a coolant, mist spraying, and high-pressure cooling systems. Although they are beneficial, conventional coolants have some disadvantages, such as negative effects on cutting tools, failure to give good surface finish quality, health hazards like skin irritation to the users, high cost of acquisition and disposal, and high environmental effects. A few of the space materials—nickel, cobalt-chromium, and titanium alloys—must be machined at high speeds for which dry machining is not feasible. For these, while traditional cutting fluids are necessary, other sophisticated lubrication methods like solid lubricants, cryogenic and gaseous cooling, and MQL can be used. MQL is a big improvement over flood coolants with the utilization of ecologically friendly, biodegradable lubricants in minimal amounts that tend to lubricate superior to conventional fluids. Moreover, MQL avoids most issues related to flood coolants, such as untidy shops, chip wetting, complex lubrication systems, skin irritation, and fluid disposal problems20.

The connection between information technologies and manufacturing Ioperations has become stronger with the arrival of Industry 4.0, smart manufacturing, and platform-based production systems. It is made possible by the usage of big data and AItechnology particularly by means of machine learning methods which depend on the data coming from the machining processes and signal analysis21. Consequently, the machine learning predictive models have been made to be an essential part of the letting efficient resource distribution, management of materials and equipment, scheduling of maintenance, tuning of process parameters, assessment and prediction of tool wear, and predicting the life of tool material that eventually results in product surface quality enhancement in manufacturing. Machine learning (ML) which is a part of artificial intelligence, refers to the algorithms that can learn to a certain degree by themselves from the input parameters, recognize complicated data patterns, and generate useful for the monitoring of the process and tool condition predictions22,23. Depending on the specific aims of the experiments and the datasets available, ML algorithms have been extensively used in different engineering and manufacturing fields for several tasks like mapping, regression, classification, and process optimization24. Among the most commonly employed ML methods are artificial neural networks (ANNs), adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference systems (ANFISs), decision trees (DTs), genetic algorithms (GAs), response surface methods (RSMs), and hybrid models which combine various approaches for better performance and robustness. A lot of studies have reviewed in great detail the application of ML-based predictive and optimization models inmanufacturing sciences and particularly in the areas of modeling, fault diagnosis, prognostics, and process conditions optimization25,26,27.

Although many research studies have delved into optimization in hard turning by employing sophisticated lubrication techniques, hybrid cutting fluids, and sensor-based monitoring systems, there remain multiple limitations preventing practical and scalable utilization in manufacturing environments. Perhaps most importantly, most current strategies are highly reliant on sophisticated sensor infrastructures to detect tool wear, vibration, cutting forces, and thermal reactions. While such systems provide precise diagnostics, their cost and operational intensity make them problematic for use in smaller- to medium-scale machining operations. In addition, most predictive models reported in the literature are designed using stand-alone statistical software packages (e.g., Taguchi, ANOVA, or RSM) or machine learning environments isolated from real-time control platforms. Only a limited number of papers have exploited the strengths of Deep Learning (DL) models within MATLAB/Simulink, which is a robust simulation and control system widely implemented in smart manufacturing systems. Besides, there is no evident lack of predictive modeling approaches based exclusively on machining process variables— depth of cut, feed rates and speed —without sensor data to predict key output variables like tool wear and surface roughness. This creates a large knowledge gap in designing light-weight, low-cost, simulation-friendly models for predictive maintenance and surface quality control during hard turning.

Identified research gaps and motivation

Most predictive studies in hard turning have focused on sensor-based monitoring systems or statistical models, such as ANOVA, RSM, and Taguchi methods, which are often complex, costly, and difficult to scale for small and medium enterprises. Furthermore, there is limited research integrating deep learning models within MATLAB/Simulink environments, which are essential for real-time control and digital twin compatibility. Existing models rarely predict machining outcomes based solely on basic cutting parameters (cutting speed, feed rate, and depth of cut) without sensor dependencies. This represents a significant gap in developing lightweight, low-cost, and simulation-ready predictive models. This work fills these gaps by creating a DL-based predictive model integrated into MATLAB/Simulink that predicts flank wear and surface roughness based solely on basic cutting parameters. Addressing these issues, this study develops a hybrid deep learning model—JOA-optimized CNN–LSTM—capable of predicting flank wear and surface roughness during hard turning of Inconel 718 under MQL conditions. By implementing the model in MATLAB/Simulink, it provides a real-time, scalable, and low-cost predictive system that bridges the gap between academic modeling and industrial deployment. The suggested approach offers a scalable and low-complexity solution compared to sensor-based systems, with direct applicability in digital twin settings and adaptive machining control. Machining Inconel 718 continues to pose significant challenges due to its high strength, poor thermal conductivity, and severe tool–workpiece adhesion, which lead to accelerated tool wear and deteriorated surface finish. Despite advances in cutting fluids and hybrid cooling techniques, achieving consistent surface integrity and tool longevity remains difficult under minimum quantity lubrication (MQL) conditions.

Rest of the section: Sect. “Related works” briefly discusses recent and pertinent research contributions in predictive modeling for machining, including the application of ML and DL methods for tool wear and surface integrity forecasting. Section “Experimental setup and methodological framework” provides the experimental setup, along with information on workpiece material (Inconel 718), specifications of CBN cutting tool, MQL system, and nano-cutting fluid ingredients. It further discusses full factorial design and measurement process for flank wear and surface roughness. Section “Experimental design” discusses the design and architecture of the suggested model. It contains data preprocessing operations, model development, hyperparameter optimization using JOA, and implementation using Simulink. Section “Experimental design” provides comprehensive model performance evaluation based on statistical parameters. and Sect. “Estimation of surface roughness and flank wear using hybrid JOA-CNN-LSTM model” concludes the findings, highlights the high accuracy and real-time applicability of the model, and provides research directions for future work.

Related works

Some of the recent literatures related to the current research are described as follows:

During hard turning of AISI M2 steel, the operation encounters serious difficulties resulting from the hard and strong material, which consequence in severe and fast tool wear. Such rapid wear compromises not only the economic efficiency and quality of the surface attainable through hard turning, but also significantly. To meet this challenge, Tianwen Zhou et al.28 performed 15 Box–Behnken design (BBD) experiments to develop a model that minimized flank wear compared to material removal. The research determined several wear types in CBN tools, including abrasive wear, crater formation, and edge chipping. They had a high prediction accuracy with R² = 0.9922 and adjusted R² = 0.9843. Depth of cut and Feed rate were the controlling factors, accounting for 48.83% and 22.05% of tool wear variability, respectively. Yet the constraints on test runs limited the general applicability of the model.

Cooling and lubrication in hard machining have also become more crucial as they affect not only the presentation of machining but also the surface quality. Of several innovative strategies, MQL with nano-cutting fluids were seen as a highly potential solution for hard turning, among others. Here, Ngo Minh Tuan et al.29 investigated the impact of MQL parameters—namely, MoS₂ nanoparticle concentration, air pressure, and air flow rate—on surface roughness and cutting force in hard turning with CBN tools. They used a BBD combined with ANOVA to evaluate the significance of each parameter and to determine optimal conditions. Their conclusion provides details regarding the application of MQL variables and provides valuable suggestions for improving hard turning operations with nano-lubricants. Nonetheless, one of the major drawbacks of the study lies in the lack of tool wear analysis, which confines the knowledge on long-term tool life under nano-MQL.

Cutting fluids are vital during high-speed machining to cool and effectively remove chips, and their efficiency can be increased with hybrid nanoparticles. Along these lines, Ariffin Arifuddin et al.30 examined the efficiency of Al₂O₃–TiO₂ hybrid nano-cutting fluid in turning machining operations. The cutting fluid was produced by a single-step approach within CNC coolant with a concentration up to 4%, and sprayed through an air-assisted MQL setup. Important performance parameters assessed in the research were cutting temperature, surface roughness (Ra), and tool wear. To organize the experiments and optimize the machining parameters, the researchers used the Response Surface Methodology (RSM). The optimal conditions found were 4% concentration of hybrid nanoparticles, rate of 0.1 mm/rev, and cut depth of 0.55 mm. These conditions gave rise to the lowest observed cutting temperature (25.3 °C), the lowest surface roughness (0.480 μm), and the lowest amount of tool wear (0.0104%). The results proved that the incorporation of hybrid nano-lubricants greatly improved both tool lifespan and surface quality and were thereby found to be extremely appropriate for CNC turning operations. The investigation did not determine the long-term stability or dispersion behavior of the hybrid nanoparticles, which could influence repeatability in the manufacturing environment.

Tool life extension is one of the significant parameters for maximizing machining parameters to obtain the expected surface finish in different engineering applications. Significant input parameters play a major role in determining both surface finish and tool life. Here, Mustafa Kuntoğlu et al.31 proposed a new method in which five different sensor-based variables—concurrent with tool wear and surface roughness—were optimized by a Tool Condition Monitoring System (TCMS), representing the first in published literature. The experiment used the Taguchi L9 orthogonal array in order to check how cutting speed, feed rate, and depth of cut influenced the turning of AISI 5140 steel. The lathe machine was provided with five different sensors: dynamometer, vibration sensor, acoustic emission (AE) sensor, temperature sensor, and motor current sensor. The data from the sensors, tool wear (VB), and surface roughness (Ra) were measured and analyzed to find their respective effects. RSM was used to optimize. Out of all the sensors, cutting force was found to be the most consistent (97.8%), followed by temperature (92.9%), AE (95.7%), motor current (74.6%), and vibration (81.3%). The best machining parameters were found to be the feed rate of 0.09 mm/rev, the depth of cut of 1 mm, and the cutting speed of 150 m/min, with an overall optimization efficiency of 82.5%. While the encouraging results, they create higher complexity and cost by relying on several sensors, thus making it less viable for small to mid-scale manufacturing businesses.

During hard turning processes, surface finish and dimensional accuracy act differently with respect to conventional turning because of the harsh machining environment. To analyze these differences, Sasan Yousefi and Mehdi Zohoor32 embarked on an in-depth study of the influence of different cutting parameters on surface roughness and dimensional accuracy with CBN tools. Cutting forces, vibrations, and tool wear were also examined in the study as a means of creating a potential knowledge-based expert system. Findings revealed that spindle speed and depth of cut have a considerable effect on dimensional accuracy and that roughness is mostly influenced by the feed rate. Other findings showed that even though tool flank wear had a slight effect on dimensional accuracy, vibration had a considerable effect. Interestingly, with the rise in rate from 0.08 to 0.32 mm/rev, dimensional deviation initially reduced, achieving its lowest value at 0.16 mm/rev, and then increased very steeply beyond this value. The best dimensional accuracy was obtained under low cutting depth, medium feed rate, and slightly decreased spindle speed. The research is not supported by statistical modeling or optimization methods, and hence its use for predictive or automated control in industry is restricted.

To enhance the machinability of compacted graphite iron (CGI), several methods have been investigated, including optimizing cutting conditions and developing advanced metalworking fluids. In this regard, Long Zhu et al.33 examined the machining performance of CGI with CBN tools at different cutting speeds using both soluble and fully synthetic water-based fluids with different sulfur contents and dilution ratios. Their research disclosed that at speed = 200 m/min, the tool life of the soluble fluid diluted to 4% with sulfur compound of 0.3% was the highest, allowing for a 23.8 km cutting distance. In another side, a soluble fluid with the same sulfur compound but diluted to 9% reduced its performance by 28.6%, only reaching 17.0 km. When raised to 300 m/min cutting speed, all fluids gave rise to considerably lower cutting distance values, all of which were below 6.0 km, with the worst performance by the full-synthetic fluid at 4.8 km. Tool life, however, takes a drastic hit at increased cutting speeds, independent of the type of metalworking fluid used.

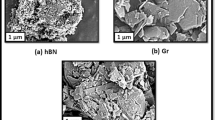

Muhammad Juzaili bin Hisam et al.34 evaluated the performance of palm oil-based nanolubricants with hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) improvement in high-speed milling of Inconel 718 with an uncoated carbide tool under MQL conditions. They found that enhancing hBN concentration enhanced the viscosity of the lubricant, with an affirmative influence on machining performance. Of the tested samples, NPO1—which had 0.05 wt% hBN—showed the best tribological belongings with lower temperatures and cutting forces, lower surface roughness, longer tool life, and minimum tool wear. The NPO3 formulation gave the worst performance with higher mechanical loads and thermal stress, coarser surface finishes, and rapid tool degradation. Thus, NPO1 appears to be a viable green substitute for traditional cooling methods, aligning with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. In addition, excessive or unbalanced hBN levels can negatively impact machining by raising cutting forces and speeding up tool wear.

Experimental setup and methodological framework

This part describes the experimental settings and methodological approach used for forecasting surface roughness and flank wear during turning of Inconel 718 alloy with the aid of a CBN TNMG160404 insert under MQL. The experiments have been conducted on a CNC lathe with solid Inconel 718 samples. A specially designed nano-cutting fluid, made with coconut oil and supported with SiC and MWCNT nanoparticles, was employed for lubrication. A complete factorial experimental design was conducted with three levels of feed rate, depth of cut, and cutting speed, which equated to 27 trials. Flank wear and surface roughness have been quantitatively measured after every run with surface metrology tools and a toolmaker’s microscope. All these data formed the basis of designing a JOA-optimized CNN-LSTM model, which was modeled, validated, and deployed on MATLAB/Simulink for real-time prediction and optimizing machining.

Experimental design

The specific aims of the current work are to forecast flank wear and surface roughness during machining Inconel 718 by utilizing various deep learning models, notably a hybrid CNN-LSTM approach, with tuned hyperparameters utilizing the JOA. The model is implemented and tested in MATLAB/Simulink to enable direct interfacing with machining systems. Model predictive performance is contrasted with experimental results for testing accuracy and stability. In addition, process parameter optimization is carried out to regulate the optimum set to reduce surface roughness and tool wear for sustainable machining under MQL.

Experiments were carried out on solid cylindrical Inconel 718 samples of dimensions 100 mm/times 60 mm. Inconel 718 is a nickel-based superalloy showing higher strength and oxidation resistance than others, finding its applications in turbine blades, nuclear reactors, and aerospace alloys because of excellent high-temperature characteristics. The Inconel 718 alloy’s chemical structure is shown in Table 1. The work piece material was chosen according to the difficulty of machining and thus was suitable for assessing high-end tool wear and surface quality prediction models. Machining was performed by a CBN tool insert (TNMG160404), with an obstruction-type chip breaker as a chip flow controller and crater-wear-reduction agent. Tool nose radius was 0.4 mm, and it was held in a conventional ISO-assigned turning tool holder. Figure.1 shows the setup of experimental, MQL layout and cutting tool.

Machining was conducted on a high-precision CNC lathe machine with spindle control facilitated through NC code (G-code), providing constant cutting speeds with precise accuracy. MQL system was incorporated, utilizing a specially designed nano-cutting fluid (NCF). The fluid was developed from clean coconut oil as the base due to its superior biodegradability, chemical compatibility, and low contact angle of 9.06°. It was reinforced with MWCNTs and SiC as nano-additives, both of which were selected for their thermal conductivity, stability, and tribological performance. The nanoparticle suspensions were created through ultrasonic agitation and ranged in concentration from 0.5% to 5% by weight, to assess their impact on lubrication and heat transfer.

The machining trials have been carried out on a CNC lathe machine. The CBN insert specification is shown in Table 2, totalling 27 experimental runs, which is shown in Table 3. This setup allows for a thorough examination of interactions among parameters and their effect. In every experimental run, the MQL flow rate was held constant at 60 mL/h, and compressed air pressure was held constant at 6 bar. Temperature readings at the cutting zone were recorded using an infrared thermal camera (Testo 872), which has a range of − 20 °C to 650 °C with ± 2% accuracy. Ra and VB were measured after each cutting pass with appropriate surface metrology and flank wear monitoring techniques based on toolmaker’s microscope reading and high-resolution imaging systems. Each test was conducted both under MQL and dry conditions to enable comparison and was replicated thrice for the sake of statistical reproducibility.

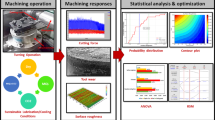

Estimation of surface roughness and flank wear using hybrid JOA-CNN-LSTM model

In order to accurately model surface roughness and flank wear in turning of Inconel 718 by employing a CBN TNMG160404 insert under MQL conditions, a hybrid deep learning architecture including CNN and LSTM is constructed. The model is optimized by employing the JOA and implemented in MATLAB/Simulink for providing a real-time, scalable prediction system integrated with adaptive machining systems. The input parameters utilized in the prediction model are gathered from 27 experimental runs with a three-level full factorial design. Two key output responses are obtained in each experiment measured after each pass under dry as well as MQL conditions. The proposed workflow architecture is shown in Fig. 2.

Dataset composition

In this research, 27 experimental trials were performed with a full factorial design having 3 levels for every one of the three main input variables (\(\:{V}_{c},f,{a}_{p}\)) and thus extensive coverage of the parameter space. One record results from each experiment with the following structure, given in Eq. (1)}.

Here, \(\:{R}_{a}\) indicates surface roughness, and \(\:{V}_{b}\) represents flank wear. Experiments were all duplicated to ensure consistency and reproducibility, and average values were noted.

Data pre-processing

Prior to training the hybrid JOA-CNN-LSTM model, the experimental dataset obtained is processed through a thorough pre-processing pipeline. The process is important to improve the accuracy of the model, make it stable for training, and remove inconsistencies or noise that can negatively affect the learning process. The pre-processing process includes three main stages: normalization, detection and removal of outliers, and partitioning of the dataset.

Feature normalization

The input features have different magnitudes and units. In order to make all the features equally contribute to the learning process and to accelerate convergence, Min-Max normalization is used. The process converts the raw values to a standard range, often [0,1], using Eq. (2).

Where, \(\:X\) indicates given feature’s actual value, \(\:{X}_{min}\) represents the minimum value of that feature in that database, \(\:{X}_{max}\) is the maximum value of that feature in that database, and \(\:{X}_{norm}\) indicates the normalized value between 0 and 1. This scaling prevents larger numerical values (e.g., cutting speed in m/min) from dominating smaller ones, and it stabilizes gradient-based learning.

Outlier detection and removal

The experimental data can have outliers due to machine abnormal conditions, sensor drift, or measurement noise. These outliers will mislead the model and decrease generalization. Thus, a two-step statistical approach is used:

-

(a)

Interquartile Range (IQR) method.

The IQR technique identifies extreme values as those which lie beyond 1.5 times the interquartile range, which is shown in Eqs. (3) and (4).

Where, \(\:{Q}_{1}\) is first quartile (25th percentile), and \(\:{Q}_{3}\) is third quartile (75th percentile). Any data point that falls outside of these limits is identified as an outlier and excluded from the dataset.

-

(b)

Z-score analysis for cross-validation.

To confirm the IQR filtering, Z-score analysis is employed. It measures how far a value is from the mean in terms of standard deviations, which is given in Eq. (5).

Where, \(\:Z\) is a standard score, \(\:\mu\:\) represents mean of the feature, and \(\:\sigma\:\) indicates standard deviation. If a data point has ∣Z∣>3, the data point will be labeled as a statistical outlier. This is a good method for validating outliers in almost normal distributions. Any data satisfying this condition is removed to avoid model bias. The combined use of Min–Max normalization and IQR–Z-score outlier detection improved the model’s stability and learning rate. Training convergence was achieved 15% faster, and RMSE reduced by approximately 22% compared to the unprocessed dataset, demonstrating the critical role of preprocessing in predictive accuracy.

Dataset partitioning

Once normalized and outliers have been removed, the clean dataset is divided into two subsets:

-

Training Set (80%): Utilized for training the CNN-LSTM model. It comprises a large range of input-output pairs to enable the model to learn the hidden relationships between the cutting parameters and output responses (Ra and VB).

-

Testing Set (20%): Utilized solely for validation to test the model’s predictive performance on novel data.

The split guarantees that the model will generalize well beyond the training set and not overfit. To ensure additional performance improvement, stratified sampling is used to keep the proportional representation of every machining condition in both subsets, thus maintaining the original distribution and preventing bias.

Hybrid JOA-CNN-LSTM architecture

In order to well-model and predict machining results—namely tool flank wear and surface roughness—under different input conditions, a hybrid DL model integrating CNN and LSTM networks is proposed. The integration takes advantage of the feature extraction ability of CNNs and the sequential pattern recognition strength of LSTMs and is very suitable for learning machining process data with complicated, nonlinear dependencies. The architecture is further optimized through the JOA, which tunes the hyperparameters automatically to enhance accuracy, convergence, and generalization.

CNN-LSTM architecture

CNN-based Spatial feature extraction

The CNN block is utilized to learn automatically and extract spatial features from the input parameter. The features are interdependencies among machining inputs and their effect on output responses. The input vector (Eq. (6)) is converted to a one-dimensional array and passed through a sequence of convolutional filters. The 1D convolution operation is mathematically represented in Eq. (7).

Where, \(\:{f}_{i}^{\left(l\right)}\) indicates output of the \(\:i\) th neuron in the \(\:l\) th layer, \(\:{w}_{j}^{\left(l\right)}\) denotes the weight associated with \(\:j\)th filter, \(\:{x}^{(l-1)}\) represents the input to the current layer from the previous layer, and \(\:{b}^{\left(l\right)}\) indicates the bias. Non-linearity is imposed by applying the ReLU activation function, which is shown in Eq. (8).

After convolution, max pooling is used to decrease feature dimensionality and highlight prominent features, which is described in Eq. (9).

This leads to a dense feature representation that preserves important information for further temporal analysis by the LSTM layers. The CNN identifies the spatial relationships among the cutting parameters, while the LSTM takes care of the sequence of tool wear development over several runs. This combination allows the system to master the spatial and temporal representations of the machining data at the same time, which is a prerequisite for the precise prediction of the dynamic machining results.

LSTM-based Temporal sequence modelling

The output feature maps from the CNN layers are fed into an LSTM network in order to capture temporal sequences, the time-dependent nature of surface wear progress and evolution of surface texture. An LSTM network consists of memory cells with three gates: forget, input, and output gates, which decide the flow of information between successive time steps. The computation in an LSTM cell is based on the following equations (10) to (15).

Where, \(\:{f}_{t}\) denotes forget gate, \(\:{i}_{t}\) represents input gate, \(\:\stackrel{\sim}{{C}_{t}}\) is the candidate cell state, \(\:{C}_{t}\) represents updated cell state, \(\:{o}_{t}\) indicates output gate, \(\:{h}_{t}\) represents final hidden state, \(\:W\) is the weight, \(\:{x}_{t}\) denotes the input at time step \(\:t\), and \(\:\sigma\:\) and \(\:tanh\) are the sigmoid and hyperbolic tangent activation functions. The last hidden state output from the LSTM is used as an input to a fully connected layer to produce the final predicted surface roughness values and flank wear values.

JOA for hyper-parameter tuning

To further improve the forecasting capability of the suggested model and eliminate the dependency on manual tuning, the JOA is utilized. JOA is a metaheuristic algorithm inspired by nature that mimics the movement of jellyfish in oceans, specifically the passive floating by ocean currents and active swimming towards nutrient-rich regions. This mechanism enables the algorithm to achieve a balance between global exploration and local exploitation within the hyperparameter search space. A starting population of candidate hyperparameter vectors is created randomly. Every vector \(\:\theta\:\) corresponds to a distinct model parameter configuration controlling the learning structure and behavior of the CNN-LSTM model. The hyperparameter vector is stated in Eq. (16).

Every hyperparameter is sampled from its defined range: Learning rate: 0.001 to 0.01; CNN filters: 32, 64, 128; LSTM units: 32 to 128; Batch size: 16, 32, or 64; and Dropout rate: 0.2 to 0.5. Every candidate solution \(\:\theta\:\) is employed to set up and train a CNN-LSTM model on the experimental dataset obtained from machining Inconel 718. The performance of every setup is computed in regards of RMSE between the forecasted and original values of \(\:{R}_{a}\) and \(\:{V}_{B}\) on the validation set, which is represented by Eq. (17).

Where, \(\:{y}_{i}\) indicates the actual experimental output, \(\:\widehat{{y}_{i}}\) represents the model-predicted output, and \(\:n\) denotes the number of samples in the validation set. Moreover, lower RMSE depicts a better-fitting model. In addition, every jellyfish (candidate solution) experience position updates in the hyperparameter space based on one of two motion strategies:

-

Passive Motion: Simulates ocean current drift by jellyfish. This encourages exploration by adding random perturbations to hyperparameter values, so the search can break out of local optima.

-

Active Motion: Guides movement towards improved food sources. A candidate approaches (or recedes from) a better solution depending on relative fitness. This maximizes exploitation of high-performing areas of the search space.

The direction of motion is dynamically regulated through a time-dependent function that optimizes exploration and exploitation as iterations advance. Furthermore, the algorithm checks if the best solution found so far gets better over subsequent generations. The population is renewed by keeping the top-performing candidates and rejecting worse ones. The optimization loop stops when:

-

A pre-defined maximum number of iterations has been reached, or.

-

Improvement in fitness becomes negligible over a few iterations.

The optimal hyperparameter set \(\:{\theta\:}^{*}\)is used to set the final CNN-LSTM model that is implemented on MATLAB/Simulink for online prediction during MQL-assisted turning of Inconel 718. The pseudocode of the presented research and the flow chart is depicted in algorithm.1 and Fig. 3, respectively. In contrast to the mutation–crossover operations of GA or the velocity-based adjustments of PSO, the JOA method uses time-controlled active and passive motion phases to maintain a global-local search balance. Such a mechanism avoids getting trapped in a local optimum too soon and results in the hyperparameter tuning process taking less time, thus leading to a model with better accuracy and stability.

Algorithm 1: JOA-optimized CNN-LSTM model for flank wear and surface roughness prediction.

Model’s performance evaluation

There are various statistical measures employed to estimate the predictive power for actual and predicted values. In the present work, comparison between experimental and predicted output is measured through three most important metrics.

Correlation coefficient

R is the measure of the direction and magnitude of the relationship between two variables among − 1 and + 1. High R value near + 1 indicates high predictive accuracy and strong positive correlation. Low value near 0 indicates no or weak correlation, and low value near − 1 specifies strong negative correlation. The sign of R is usually the same as the sign of the regression slope. The R is computed by Eq. (18)

RMSE

The RMSE is a popular measure that is the square root of the mean of the squared alterations between definite and projected values. It is mathematically done by adding the squared prediction errors and then dividing them by the number of observations before taking the square root35,36. Small values of RMSE suggest good model performance, ideally zero, while large ones show higher deviation from true results and lower accuracy37, which is computed by Eq. (19).

MAPE

MAPE computes the mean of the absolute errors expressed as a percentage of the actual (measured) values. It is very much favored as a measure for assessing predictive models since it measures performance in relative terms38,39. MAPE comes particularly in handy when comparing models between different datasets or scales36. Based on the categorization by Lewis, a model is termed:

-

Extremely accurate if MAPE < 10%.

-

Poor if MAPE > 50%.

-

Satisfactory if 20% ≤ MAPE ≤ 50%.

-

Good if 10% ≤ MAPE ≤ 20%.

Where, \(\:{\widehat{p}}_{j}\) indicates predicted value, \(\:{m}_{j}\) represents measured values, \(\:\widehat{m}\) denotes mean of measured values, \(\:\widehat{p}\) denotes predicted value’s mean, and \(\:n\) represents number of observations, as shown in Eqs. (18) to (20).

Result and discussion

The chosen machining parameters—\(\:Vc\), \(\:f\), and \(\:{a}_{p}\),—and the respective average Ra and VB, were solved using MATLAB/Simulink. This part discusses the effect of these process variables on the response output. In developing each DL and Machine Learning (ML) model, such as RNN, LSTM, conventional SVM, and ANN, input features and measured output were divided systematically in order to enable model training and testing. The Simulink-based deployment allows direct real-time integration with CNC controllers through block-level representation, enhancing predictive automation. The system’s digital-twin compatibility supports closed-loop feedback, making the model readily scalable to industrial shop-floor conditions.

The figure.4 shows the Simulink block architecture of the developed DL-based model developed for predicting Ra and VB. The input block ‘XVal′’ indicates the validation dataset fed to the neural network’s sequence input layer. The system core involves a trained DL regression network that receives the input data and produces an estimated surface roughness value through the regression output layer. The regression layer output is transformed from DL to numeric double precision through the toDouble MATLAB function block. Lastly, the predicted value is routed to the output port ‘out.Ypred’, which is the estimated surface roughness.

Training progress and convergence analysis of the JOA-Optimized CNN-LSTM model

For guaranteed reliability and accuracy of the presented model, optimized with the JOA, its training dynamics and convergence behavior must be examined. The following section gives an enhanced description of the model’s learning trajectory for several epochs based on important metrics such as loss and RMSE for validation and training sets. The trend of convergences provides a view of how accurately the model fits the training data and generalizes to new unseen test data. From observing the trend in loss and RMSE during training, it is possible to detect overfitting, underfitting, or instability problems early in the training process. The trend of these metrics captures the effectiveness of the model optimization, the efficiency of learning, and the strength of the model, which are all essential for applying the model in real-time predictive machining applications. The findings also support the advantages of employing JOA for tuning hyperparameters in predictive models based on DL.

Figure. 5 shows the convergence behavior of the JOA-optimized CNN-LSTM model by representing the training and validation loss over 2000 epochs. The training loss (black curve) drops consistently and levels off after around 1000 epochs, suggesting that the model has successfully learned the latent data distribution. The validation loss (red curve) also tends downward but with higher fluctuations as a result of changing unseen data. Notably, the training and validation loss gap is small and steady, indicating little overfitting and excellent generalization of the model. The initial sharp decrease in both losses indicates fast learning at the early stages of training.

This Fig. 6 displays the RMSE with respect to training epochs for the training (black curve) and validation (red curve) sets. The RMSE values start high, indicating the initial errors of the model. The two curves do begin to significantly decrease in the first couple of hundred epochs. The training RMSE then continues to improve gradually and levels off at a very low value, suggesting high accuracy on the training set. The validation RMSE also decreases significantly but with greater variability because of the dynamic character of the test samples. However, the validation RMSE is still quite close to the training RMSE, which affirms the model’s strength and predictive accuracy.

Performance analysis based on testing data

Figures 7 (a) and (b) present the comparison values, for five test cases from experiments using the developed JOA-optimized CNN-LSTM model. The predicted values exhibit excellent agreement with the experimental data, testifying to the model’s strength and high unseen-data generalization capability. In Fig. 7 (a), both the predicted and measured trend of flank wear values are similar in all five experiments with only a slight variation. For example, at Experiment 1, measured VB is ~ 205 μm, whereas the predicted value is 208 μm. Maximum flank wear is seen in Experiment 3 when the measured and predicted values are ~ 340 μm and 348 μm, respectively. In Experiment 5, the wear is remarkably low at ~ 120 μm (measured) and ~ 110 μm (predicted). Figure 7 (b) shows a comparison of predicted vs. actual surface roughness value. At Experiment 1, Ra = 0.24 μm (measured) and 0.26 μm (predicted). Peak roughness is seen at Experiments 2 and 3, with both approaching 0.68–0.69 μm in measured and predicted values. At Experiment 5, the values drop to 0.26 μm (measured) and 0.24 μm (predicted). The small difference verifies the model’s capability to represent the nonlinear and intricate relationships that preside over surface finish across changing machining conditions.

Figures 7 (c) and (d) are the plots of regression between flank wear and surface roughness, respectively. They visualize the linear relationship between measured and predicted values and give the regression coefficient (R) as a quantitative measure of the strength of prediction. In Fig. 7 (c), the regression coefficient for prediction of flank wear is R = 0.99759, showing very strong positive correlation. The data points on the plot all fall closely along the perfect diagonal line (Y = T), agreeing with the minimal prediction error. Likewise, Fig. 7 (d) presents an R-value of 0.99812 for predicting surface roughness. The closeness of the data points to the fit line indicates that the model predictions are nearly identical to the actual experimental results.

Performance assessment based on training data

To evaluate the fidelity of the suggested model in training, a direct comparison was established for all 27 experimental runs. The graphical comparisons are shown in Figs. 8(a) and (b). From Fig. 8(a), the predicted flank wear values are very much comparable to the experimentally measured data across the whole experimental spectrum. The highest measured VB was found to be around 830 μm, and the calculated value also reached ~ 820 μm, indicating a small deviation of less than 10 μm. Likewise, for reduced flank wear situations (such as Experiments 12 and 19), calculated values closely replicated the steep dips in the measured values, and the errors were always less than ± 15 μm. In the same way, Fig. 8 (b) shows the comparison for roughness. The range of measured Ra was 0.22 μm to 0.92 μm, and the predicted values accurately modeled this trend with very little deviation. For regions of high surface finish (e.g., Ra ≈ 0.25 μm), the predicted roughness remained within ± 0.02 μm of the true value. Under more abrasive machining conditions (e.g., Ra ≈ 0.88–0.91 μm, experiments 1 and 18), the model proved very accurate with predicted values in the 0.90 μm to 0.93 μm range.

The regression analysis of Figs. 8(c) and (d) also testifies further to the accuracy of prediction from the model. The correlation coefficient (R) for flank wear estimation was 0.99888 and for surface roughness, 0.99937. Both are close to unity, implying a virtually perfect linear association between predicted and actual response. These findings confirm that the introduced DL model is not only able to learn complex process-parameter correlations during training but also operates stably with very low error over a broad range of experimental conditions. This consolidates the promise of the developed model as a trustworthy predictive model in sustainable machining situations.

Effect of machining parameters: 3D response surface analysis

Knowledge of the effect of dominant machining parameters is vital to gain high surface quality and reduced tool wear in turning hard-to-machine materials such as Inconel 718. This section introduces a comprehensive 3D response surface analysis for visualizing and interpreting how process parameters interact and affect two important output responses: surface roughness (Ra) and flank wear (VB). The investigation is founded on experimental results obtained under MQL environments through a manual CBN cutting tool. The non-linear relationships and synergies between the parameters are demonstrated by anisotropic 3D surface plots, yielding insightful information on optimal machining zones. Visualization facilitates the identification of the most promising parameter combinations, which optimize the surface finish and tool life, to facilitate predictive modeling and real-time control concepts in modern manufacturing environments.

The 3D plots reveal that the lowest surface roughness occurs at high cutting speed (100 m/min) and low feed rate (0.04 mm/rev), while flank wear is minimized under similar conditions. These zones represent the optimal machining conditions where improved chip evacuation and reduced thermal stress coexist.

Figure 9(a) is a 3D surface plot showing the combination of cutting speed and feed rate on Ra. The plot indicates that higher speeds yield lower surface roughness. The reason for the improvement is due to improved chip formation and lesser cutting forces at higher speeds. Increasing the feed rate, however, causes a steep increase in Ra values owing to greater chip thickness and a rough surface profile. The minimum roughness is achieved at high cutting speeds and low feed rates, marking this region as the ideal zone for better surface finish. Figure 9(b) shows the interaction between feed rate and depth of cut on Ra. There is a steady increase in Ra with higher feed rates regardless of the range of depth of cut. Depth of cut, however, seems to have relatively lesser impact on surface roughness here. The near-horizontal orientation of the plot along the depth of cut axis indicates that feed rate has a very overwhelming effect on Ra. The best surface finish is achieved at low feed rates and low to medium depths of cut. Figure 9(c) investigates the effect of cutting speed and depth of cut on surface roughness. The plot shows a downward trend in Ra with higher cutting speeds, marking the advantage of high-speed machining to improve surface quality. Parallel to that, the effect of depth of cut is nonlinear—whereas at lower speeds, increasing the depth slightly increases Ra, the effect does weaken at higher speeds. This indicates that higher cutting speeds have the potential to counter the adverse effects of increased depths of cut on surface finish.

Figure 9(d) shows the variation of VB with cutting speed and feed rate. Severe VB increase is evident with increasing feed rates owing to higher mechanical loads and higher tool-workpiece friction. Conversely, increasing cutting speeds cause a dramatic reduction in VB, especially at low feed rates. Minimum flank wear is seen under the high cutting speed and low feed rate conditions, which indicates this as the optimum combination to achieve maximum tool life. Figure 9(e) explores the combined influence of feed rate and depth of cut on VB. The plot reveals that VB increases sharply with the increase in feed rates, particularly when the depth of cut is high to moderate. This is owing to higher cutting loads and heat generation in addition to higher material removal rates. The effect of depth of cut on VB is unexpectedly nonlinear—beyond a depth value, further increase causes only minor changes in wear. Optimal tool longevity is realized when feed rate and depth of cut are maintained low. Figure 9(f) shows a response surface plot. The surface is of a saddle-like type, where VB increases with depth of cut at moderate cutting speeds but decreases slightly at very high speeds. Maximum flank wear occurs in mid-region, which is a critical region with extreme thermal and mechanical stress. There is less VB in low speed and shallow depth or high speed and moderate depth, i.e., best conditions for wear resistance.

Internal comparison with traditional models

In machining predictive modeling, it is crucial to assess the reliability and precision of various methodologies in order to choose the most efficient method. In this section, the comparison between the traditional ML models, i.e., SVM and ANN, and the other DL models, i.e., RNN, LSTM, and the proposed JOA-optimized hybrid CNN-LSTM model, is presented. The comparison is grounded in the predictive accuracy of each model for two key machining outputs: VB and Ra, over 27 controlled experiments on the turning of Inconel 718 under MQL conditions. Figures 4 and 5 graphically show how predicted values compare with experimentally measured results. Performance measurement criteria like R, RMSE, and MAPE are employed for the measurement of quality of prediction. The hybrid model, developed through JOA, exhibits better accuracy and stability, with much greater performance than standard models, in capturing the nonlinear and time-varying nature of tool wear and surface finish. This internal verification is a strong validation of the ability of the proposed model in real-time machining operations.

Figure 10 illustrates Comparison between measured flank wear and predicted values based on traditional SVM, ANN, RNN, LSTM, and the proposed JOA-optimized CNN-LSTM model in 27 experiments. This figure depicts the performance of various ML and DL models in predicting flank wear (VB) in turning Inconel 718 alloy under MQL conditions. The black solid line indicates experimentally measured flank wear and the colored lines indicate the predicted values from: Conventional SVM (red), ANN (purple), RNN (yellow), LSTM (green) and proposed hybrid JOA-CNN-LSTM model (blue dashed line with circles). The suggested model closely tracks the observed trend in all experiments, especially recording the peak wear at around Experiment 18 (~ 860 μm). All other models reveal noticeable deviations from the trend, with SVM tending to underestimate or overestimate sudden changes. ANN reveals comparatively smoother curves, while LSTM and RNN record the trend better but are still less accurate than the suggested model. This comparison verifies the model proposed to have a better capability in generalizing and fitting nonlinear changes in flank wear.

Figure 11 indicates Comparison between measured surface roughness and predicted values with traditional SVM, ANN, RNN, LSTM, and the proposed JOA-optimized CNN-LSTM model for 27 experiments. This plot compares the predictive accuracy of a number of ML/DL models for surface roughness (Ra) over the same 27 experimental trials. Black line indicates actual measured values, whereas predictions are plotted for: traditional SVM (red), ANN (purple), RNN (yellow), LSTM (green), and proposed JOA-CNN-LSTM model (blue dashed line with circles). The suggested model shows high prediction accuracy, exhibiting almost perfect correspondence to the experimental outcomes, particularly in dynamic areas like Experiments 1, 10, 19, and 22. Conventional SVM overestimates sharper peaks and troughs, whereas ANN and RNN offer more generalized fits. LSTM performs similarly but does not keep up with the proposed model’s accuracy in extreme transitions. In general, the suggested hybrid model demonstrates improved stability and accuracy and is very well-suited for predictive monitoring of surface finish in actual machining conditions.

Performance comparison of ML/DL models: flank wear and surface roughness

To compare the proposed model’s efficacy, its predictive accuracy was compared with conventional ML and regular DL approaches. The comparison was made on primary statistical performance metrics—R, RMSE, and MAPE—for both surface roughness and flank wear. The intention was to compare the most accurate and stable model for predictive machining under MQL conditions.

The suggested model exhibits better prediction accuracy for flank wear compared to conventional ML and baseline DL models, which is shown in Table 4. It attains the highest correlation coefficient of (R = 0.9987), reflecting a near-perfect linear association between measured and predicted values. Moreover, the lowest RMSE (0.0822) and MAPE (3.67%) reflect minimal error and extremely accurate predictions. In comparison, classical SVM and ANN models have much greater error rates with RMSE values well above 0.42 and MAPE well over 18%, reflecting poorer predictive robustness.

For roughness prediction on the surface, the suggested model outcompetes other models yet again, which is depicted in Table 5. It has the highest value of correlation coefficient R = 0.9991 among all, which indicates a near-perfect conformity between calculated and experimental values. It also has the lowest RMSE value of 0.0095 and the MAPE value of 2.21%, making the model “highly accurate” as per the interpretive scale of Lewis. The LSTM model stands at second position, with only marginally increased error boundaries, whereas the SVM model performs worst with the maximum MAPE of 13.48%, indicating poor applicability for accurate surface quality prediction. Moreover, Table 6 shows a comparative study of different predictive modeling approaches adopted to forecast surface roughness. The performance of the models is compared using three measures. These measures test the precision, reliability, and predictability of each model. The competing methods involve some common machine learning algorithms like adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS), Gaussian process relation (GPR), ANN, and SVM40, and Bayesian regularization neural network (BRNN)41, with the last row for the Proposed model’s performance.

The model proposed here shows better performance on all three of our evaluation metrics: It has a near-excellent R value of 0.9991, meaning an almost perfect agreement between predicted and actual surface roughness values. The RMSE is appreciably lower (0.0095) than that of all other models, meaning very low prediction error. MAPE of 2.21% indicates a tremendous improvement in the accuracy of prediction, where errors are decreased more than 90% as compared to the best-performing conventional technique (ANFIS). Conversely, current techniques like ANFIS, GPR, ANN, and SVM, retrieved from21, exhibit mediocre predictive performances with R values between 0.78 and 0.81, RMSEs of about 0.17–0.19, and excessive MAPE values (in excess of 30%). The BRNN model, as quoted from22, does not provide an R value but possesses comparatively higher RMSE (0.1844) and MAPE (37.38%), which indicates poorer performance than the proposed technique. The table effectively demonstrates the potential of the proposed model for prediction of surface irregularity with astonishingly high accuracy and dependability, surpassing all current methods quoted. This highlights the model’s applicability to real-world machining or manufacturing processes where surface finish is a key quality measure.

Discussion

The JOA-optimized CNN-LSTM framework has produced results that correlate very well between the predicted and actual values of surface roughness and flank wear during hard turning of Inconel 718 under minimum quantity lubrication (MQL) conditions. The model is extremely precise, as evidenced by the correlation coefficients (R) of 0.9991 for surface roughness (Ra) and 0.9987 for flank wear (VB), which verifies the model’s capability to detect the nonlinear relations between the machine settings and the output performance. The low RMSE and MAPE scores are further proof of the strength and broad applicability of the suggested hybrid deep learning model. The main reason for the observed reduction in surface roughness at higher cutting speeds is the better chip flow and less formation of built-up edge (BUE), which are the main contributors to the reduction of surface roughness at higher temperatures. With faster cutting, the workpiece layer BUE gets softened and goes through the smoother removal at the tool spot where adhesion is rated really low, resulting in the best surface conditions. At the same time, an increase in feed rate results in higher uncut chip thickness, which in its turn creates pronounced feed marks and surface irregularities. The 3D response surface plots confirm the findings that surface roughness is very sensitive to feed rate, whereas cutting speed plays a stabilizing role affecting thermal softening and chip formation).

Flank wear (VB) showed a nonlinear progression affected by the interaction of cutting speed, feed rate, and depth of cut. Moreover, the increase in feed rate and depth of cut caused the frictional contact to become stronger, the cutting temperature to rise, and tool life to be reduced through the processes of abrasive and adhesive wear. On the contrary, at the cutoff of higher speeds, the thermal softening of Inconel 718 lowers the shear strength at the chip-tool interface thus limiting abrasive wear and enhancing wear resistance. These interactions indicate the thermo-mechanical balance between heat generation, material flow, and lubrication efficiency in MQL machining. One way to explain the more excellent prediction accuracy of the JOA-optimized CNN–LSTM model can be scientifically justified by its hybrid architecture that fuses the spatial and temporal feature extraction. The CNN layers come into play to reveal the spatial correlations among process parameters (cutting speed, feed, and depth of cut), thus capturing the hidden interactions that influence tool wear and surface finish. The LSTM layers, on the contrary, model the sequential evolution of machining responses over time and, thus, are able to capture temporal dependencies in wear progression and surface deterioration patterns. The synergy of both layers gives the network the capability to learn complex, nonlinear relationships that traditional machine learning models such as SVM, ANN, and ANFIS cannot represent.

The application of the Jellyfish Optimization Algorithm (JOA) leads to even higher model performance as a result of optimal hyperparameter tuning. JOA is different from Genetic Algorithms or Particle Swarm Optimization as its dynamic exploration and exploitation balancing is done through active and passive movement modes which makes it not to converge prematurely. Stable learning, overfitting control, and faster convergence rates are the outcomes of this. Therefore, the JOA–CNN–LSTM framework proves to be the most reliable for prediction when compared to deep learning alone or classical statistical modeling methods. The advantage of the predictive model is not only in its high numerical performance but also in its capability to represent the relationships of the machining physics. The very high correlation coefficients (R > 0.99) are proof that the model has internalized the real cause-and-effect relationships of cutting dynamics instead of simply fitting statistics to the data. The trends predicted by the model are in line with the physical laws of metal cutting: high-speed machining results in less BUE formation, while higher feeds lead to more mechanical stress and rougher surfaces. This could point to the CNN–LSTM architecture implicitly capturing the characteristics of thermo-mechanical interactions associated with chip formation, tool–workpiece friction, and MQL-related lubrication.

The hybrid model that is being proposed has significantly better accuracy when compared with traditional techniques such as SVM, ANN, ANFIS, and GPR. The RMSE for surface roughness prediction was down from 0.0533 (SVM) and 0.0389 (ANN) to 0.0095 (JOA–CNN–LSTM), which is a whopping 75–80% drop in prediction error. This progress can be credited to the combined learning approach of CNN–LSTM, where the instances of the process variations and the long-term degradation behavior are captured. The JOA optimizer plays the part of fine-tuning model parameters so that the loss function converges to the global optimum and not a local minimum. The 3D response surfaces (Fig. 9) give a deeper understanding of the interaction of cutting speed, feed rate, and depth of cut. In the case of surface roughness, the lowest Ra value is at high cutting speeds (100 m/min) and low feed rates (0.04 mm/rev), thus pointing to the thermal softening and BUE being reduced at the optimal lubrication levels taking over. For tool wear, VB shows a parabolic behavior where wear is increased with feed and depth but decreased at moderate speed because of better lubrication film formation. The optimal zone has been identified as being the one where temperature, friction, and lubrication forces are balanced, thus ensuring low roughness and no wear. The scientific interpretation of the results essentially validates the synergism of hybrid deep learning and machining physics as a robust trail to predictive machining. The JOA–CNN–LSTM model not only assures high prediction accuracy but also promotes interpretability by comparing the data-driven results with the physical process behavior. The Simulink implementation of it makes the adaptability to real-time possible, which in turn fosters predictive control and digital twin integration for sustainable, smart manufacturing. The enlightening of these factors shows that data-driven models can be at the same time accurate and physically informative thus making them the very instruments for the next-gen machining systems.

Conclusion

This paper proposes an original DL approach to predictive modeling of tool VB and Ra during Inconel 718 machining with a CBN tool under MQL conditions. The designed hybrid model, with hyperparameters optimized by the JOA, shows an excellent ability to model intricate nonlinear interactions between cutting parameters and machining results. By implementing the model in MATLAB/Simulink, the article fills the gap between state-of-the-art AI modeling and real-world industrial practice, allowing smooth integration with cyber-physical manufacturing systems that can immediately benefit from the developed model. The model surpasses outstanding performance results with R of 0.9991, RMSE of 0.0095, and MAPE of 2.21% in predicting surface roughness, significantly outperforming traditional ML methods like SVM, ANN, and statistical methods like ANFIS and GPR. For the prediction of flank wear, the model also has a high R value of 0.9987, indicating consistent and accurate predictions under changing machining conditions. Integrating real-time sensor feedback (vibration, cutting force, temperature) will enable the hybrid CNN–LSTM to retrain adaptively during live machining, thereby improving robustness under variable cutting conditions and further supporting digital twin implementations. Additionally, its benefit is not just predictive capability but also its independence from expensive, sensor-laden monitoring systems. Being based on process parameters alone, it provides low-cost, mass-producible capabilities for SMEs operating in hard-to-machine alloy processing. The 3D response surface analysis also validates the model’s sapience for comprehending the impact of machining constraints on surface quality and tool wear. This research contributes to smart and sustainable manufacturing by offering a low-cost, sensor-independent predictive framework deployable on standard CNC systems. Its compatibility with MQL machining and Simulink integration supports digital-twin readiness, resource efficiency, and scalable predictive maintenance—especially suited for SMEs processing difficult-to-machine alloys. Future research will extend this model to a multi-objective optimization framework using JOA, defining a composite function \(\:f={w}_{1}Ra+{w}_{2}VB+{w}_{3}{E}_{c}\text{\--}{w}_{4}MRR\). This approach will enable simultaneous optimization of surface integrity, tool longevity, and energy efficiency. Additionally, integrating real-time sensor feedback—vibration, temperature, and cutting forces—will improve the model’s robustness and adaptability, particularly under dynamic and interrupted machining conditions.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the correspondingauthor upon reasonable request. Due to confidentiality agreements and institutional policies, access to certain data may be restricted. However, processed and anonymized data supporting the findings of this study can be made available upon request for academic and research purposes.

References

Eskandari, B., Bhowmick, S. & Alpas, A. T. Flooded drilling of inconel 718 using graphene incorporating cutting fluid. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 112 (1–2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-020-06195-9 (2021).

Wayal, V., Ambhore, N., Chinchanikar, S. & Bhokse, V. Investigation on cutting force and vibration signals in turning: mathematical modeling using response surface methodology. J. Mech. Eng. Autom. 5 (3B), 64–68 (2015).

Makhesana, M. A., Patel, K. M. & Bagga, P. J. Evaluation of surface Roughness, tool wear and chip morphology during machining of Nickel-Based alloy under sustainable hybrid Nanofluid-MQL strategy. Lubricants 10 (11), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants10110315 (2022).

Khanna, N., Shah, P., Agrawal, C., Pusavec, F. & Hegab, H. Inconel 718 machining performance evaluation using Indigenously developed hybrid machining facilities: experimental investigation and sustainability assessment. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 106 (11), 4987–4999. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-020-04921-x (2020).

Said, Z. et al. A comprehensive review on minimum quantity lubrication (MQL) in machining processes using nano-cutting fluids. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 105 (5), 2057–2086. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-019-04382-x (2019).

Manikanta, J. E., Raju, B. N., Ambhore, N. & Santosh, S. Optimizing sustainable machining processes: a comparative study of multi-objective optimization techniques for minimum quantity lubrication with natural material derivatives in turning SS304. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. IJIDeM. 18 (2), 789–800 (2024).

Waydande, P., Ambhore, N. & Chinchanikar, S. A review on tool wear monitoring system, J. Mech. Eng. Autom., 6(5A), 49–53 Accessed: Oct. 31, 2025. [Online]. (2016). Available: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?cluster=16638737476696855021&hl=en&oi=scholarr

Ambhore, N., Kamble, D. & Chinchanikar, S. Prediction of cutting tool vibration and surface roughness in hard turning of AISI52100 steel, in MATEC Web of Conferences, EDP Sciences, 03011. Accessed: Oct. 31, 2025. [Online]. (2018). Available: https://www.matec-conferences.org/articles/matecconf/abs/2018/70/matecconf_vetomacxiv2018_03011/matecconf_vetomacxiv2018_03011.html

Agrawal, C., Khanna, N., Gupta, M. K. & Kaynak, Y. Sustainability assessment of in-house developed environment-friendly hybrid techniques for turning Ti-6Al-4V. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 26, e00220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.susmat.2020.e00220 (2020).

Ambhore, N. H., Hivarale, S. D. & Pangavhane, D. D. A comparative study of parametric models of magnetorheological fluid suspension dampers, Int. J. Mech. Eng. Technol., 4 (1), 222–232 Accessed: Oct. 31, 2025. [Online]. (2013). Available: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?cluster=10921658903684175916&hl=en&oi=scholarr

Karpuschewski, B., Byrne, G., Denkena, B., Oliveira, J. & Vereschaka, A. Machining processes. In Springer Handbook of Mechanical Engineering (eds Grote, K. H. & Hefazi, H.) 409–460 (Springer International Publishing, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47035-7_12.

Ghule, G., Ambhore, N. & Chinchanikar, S. Tool condition monitoring using vibration signals during hard turning: a review, in International Conference on Advances in Thermal Systems, Materials and Design Engineering (ATSMDE, 2017).

Wang, B. et al. Advancements in material removal mechanism and surface integrity of high speed metal cutting: A review. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 166 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmachtools.2021.103744 (2021).

Dhumal, A. R., Kulkarni, A. P. & Ambhore, N. H. A comprehensive review on thermal management of electronic devices. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 70 (1), 140. https://doi.org/10.1186/s44147-023-00309-2 (2023).

Singh, J., Gill, S. S., Dogra, M. & Singh, R. A review on cutting fluids used in machining processes. Eng. Res. Express. 3 (1), 012002. https://doi.org/10.1088/2631-8695/abeca0 (2021).

Duc, T. M., Long, T. T. & Van Thanh, D. Evaluation of minimum quantity lubrication and minimum quantity cooling lubrication performance in hard drilling of Hardox 500 steel using Al2O3 nanofluid. Adv. Mech. Eng. 12 (2). https://doi.org/10.1177/1687814019888404 (2020).

N., S. R. R. J. H., Krolczyk, G. M. & S. K. J., and A comprehensive review on research developments of vegetable-oil based cutting fluids for sustainable machining challenges. J. Manuf. Process. 67, 286–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmapro.2021.05.002 (2021).

Ambhore, N., Kamble, D., Chinchanikar, S. & Wayal, V. Tool Condition Monitoring System: A Review, Mater. Today Proc., 2 (4), 3419–3428, (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2015.07.317

Pedroso, A. F. V. et al. A comprehensive review on the conventional and Non-Conventional machining and Tool-Wear mechanisms of INCONEL®. Metals 13 (3), 585. https://doi.org/10.3390/met13030585 (2023).

Kumar, A., Sharma, A. K. & Katiyar, J. K. State-of-the-Art in sustainable machining of different materials using nano minimum quality lubrication (NMQL). Lubricants 11 (2), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants11020064 (2023).

Rai, R., Tiwari, M. K., Ivanov, D. & Dolgui, A. Machine learning in manufacturing and industry 4.0 applications. Int. J. Prod. Res. 59 (16), 4773–4778. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2021.1956675 (2021).

Raffin, T., Reichenstein, T., Werner, J., Kühl, A. & Franke, J. A reference architecture for the operationalization of machine learning models in manufacturing. Procedia CIRP. 115, 130–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2022.10.062 (2022).

Serin, G., Sener, B., Ozbayoglu, A. M. & Unver, H. O. Review of tool condition monitoring in machining and opportunities for deep learning. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 109 (3–4), 953–974. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-020-05449-w (2020).

Soori, M., Arezoo, B. & Dastres, R. Machine learning and artificial intelligence in CNC machine tools, A review. Sustain. Manuf. Serv. Econ. 2, 100009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smse.2023.100009 (2023).

Imad, M., Hopkins, C., Hosseini, A., Yussefian, N. Z. & Kishawy, H. A. Intelligent machining: a review of trends, achievements and current progress. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 35 (4–5), 359–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/0951192X.2021.1891573 (2022).

Bertolini, M., Mezzogori, D., Neroni, M. & Zammori, F. Machine learning for industrial applications: A comprehensive literature review. Expert Syst. Appl. 175 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2021.114820 (2021).

Upase, R. & Ambhore, N. Experimental investigation of tool wear using vibration signals: An ANN approach, Mater. Today Proc., 24, 1365–1375, (2020).

Zhou, T. et al. Optimization of cutting parameters for cubic Boron nitride tool wear in hard turning AISI M2. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 33 (20), 11298–11308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11665-023-08743-2 (2024).

Tuan, N. M., Long, T. T. & Ngoc, T. B. Study of effects of MoS2 nanofluid MQL parameters on cutting forces and surface roughness in hard turning using CBN insert. Fluids 8 (7), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/fluids8070188 (2023).

Arifuddin, A., Redhwan, A. A. M., Azmi, W. H. & Zawawi, N. N. M. Performance of Al2O3/TiO2 hybrid Nano-Cutting fluid in MQL turning operation via RSM approach. Lubricants 10 (12), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants10120366 (2022).

Kuntoğlu, M. et al. Optimization and analysis of surface Roughness, flank wear and 5 different sensorial data via tool condition monitoring system in turning of AISI 5140. Sensors 20 (16). https://doi.org/10.3390/s20164377 (2020).

Yousefi, S. & Zohoor, M. Effect of cutting parameters on the dimensional accuracy and surface finish in the hard turning of MDN250 steel with cubic Boron nitride tool, for developing a knowledged base expert system. Int. J. Mech. Mater. Eng. 14 (1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40712-018-0097-7 (2019).

Zhu, L., Evans, R., Zhou, Y. & Ren, F. Wear study of cubic Boron nitride (cBN) cutting tool for machining of compacted graphite iron (CGI) with different metalworking fluids. Lubricants 10 (4). https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants10040051 (2022).

bin Hisam, M. J. et al. Assessment of novel palm oil modifications performance in High-Speed milling of inconel 718 through minimum quantity lubrication application. Int. J. Precis Eng. Manuf. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12541-025-01213-w (2025).

Rafighi, M., Özdemir, M., Shehabi, S. A. & Kaya, M. T. Sustainable hard turning of high chromium AISI D2 tool steel using CBN and ceramic inserts. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 74 (7), 1639–1653. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12666-021-02245-2 (2021).

Adizue UL, Nwanya SC, Ozor PA .rtificial neural network application to a process time planning problem for palm oilproduction. Engineering and Applied Science Research 47(2), 161–169 https://doi.org/10.14456/easr.2020.17(2020)

Chicco, D., Warrens, M. J. & Jurman, G. The coefficient of determination R-squared is more informative than SMAPE, MAE, MAPE, MSE and RMSE in regression analysis evaluation. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 7, e623. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.623 (2021).

Jachak, S., Giri, J., Awari, G. K. & Bonde, A. S. Surface finish generated in turning of medium carbon steel parts using conventional and adhesive bonded tools, Mater. Today Proc., 43, 2882–2887 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2021.01.127

Pant, P. & Chatterjee, D. Prediction of clad characteristics using ANN and combined PSO-ANN algorithms in laser metal deposition process. Surf. Interfaces. 21 (100699). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfin.2020.100699 (2020).

Adizue, U. L., Tura, A. D., Isaya, E. O., Farkas, B. Z. & Takács, M. Surface quality prediction by machine learning methods and process parameter optimization in ultra-precision machining of AISI D2 using CBN tool. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 129 (3–4), 1375–1394. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-023-12366-1 (2023).

Adizue, U. L. & Takács, M. Exploring the correlation between design of experiments and machine learning prediction accuracy in ultra-precision hard turning of AISI D2 with CBN insert: a comparative study of Taguchi and full factorial designs. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 137 (3–4), 2061–2090. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-025-15186-7 (2025).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Symbiosis International (Deemed University).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Contributing authors: [subhash.khetre.phd2019@sitpune.edu.in](mailto: subhash.khetre.phd2019@sitpune.edu.in); [arun.bongale@sitpune.edu.in](mailto: arun.bongale@sitpune.edu.in); [satishkumar.vc@gmail.com](mailto: satishkumar.vc@gmail.com)These authors contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions