Abstract

To investigate the association of different diurnal blood pressure patterns with heart rate variability (HRV) and hypertensive retinopathy (HR) risk in essential hypertension patients. A total of 181 patients (Jan 2023−Jun 2025) were grouped by nocturnal systolic blood pressure fall rate (SBPF): dipper (n = 57, 10%≤SBPF < 20%), non-dipper (n = 62, 0 ≤ SBPF < 10%), reverse-dipper (n = 62, SBPF < 0%). Ambulatory blood pressure (BP), HRV indices, and HR detection rate were compared. Reverse-dipper had higher nocturnal SBP (nSBP), 24-hour SBP (24hSBP) than the other two groups (all P < 0.05), and higher nocturnal DBP (nDBP) than dipper (P = 0.002). Dipper’s HRV indices (SDNN, SDANN, RMSSD, PNN50, LF, HF) were better than non-dipper (P < 0.05); SDNN, SDANN, LF were better than reverse-dipper (all P < 0.001). Reverse-dipper’s LF/HF was lower than others (P < 0.05). HR detection rates: 3.5% (dipper), 46.8% (non-dipper), 50.0% (reverse-dipper) (P < 0.001). Multivariable regression: BMI (OR = 1.131) was an independent risk factor; dipper (vs. reverse-dipper, OR = 0.031) was protective (P < 0.05). Reverse-dipper has the highest nocturnal BP load, dipper the most favorable (better autonomic regulation). Ambulatory BP monitoring and BMI control are crucial to reduce target organ damage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hypertension is one of the important factors causing the global burden of disease, affecting over one-quarter of the world’s population1. In healthy individuals, blood pressure follows a diurnal pattern characterized by a nocturnal decline and daytime rise. A physiological nocturnal decline of 10–20% (dipper pattern) is considered protective for target organs. When the nighttime fall is < 10% (non-dipper) or paradoxically rises (reverse-dipper), cardiovascular risk increases substantially2,3. These abnormalities are closely associated with circadian clock dysfunction and dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system4,5. Heart rate variability (HRV) is a noninvasive marker for autonomic function6,7, and reduced HRV independently predicts cardiovascular mortalit8. Because both diurnal blood pressure rhythm and HRV are governed by autonomic regulation, their abnormalities may share common pathophysiological mechanisms9.Hypertensive retinopathy is increasingly prevalent. The ocular fundus provides a unique window to observe the microcirculation in vivo; retinal vasculature is often regarded as a mirror of systemic small-artery health10. Abnormal blood pressure patterns—especially absent or paradoxically elevated nighttime blood pressure—can expose retinal vessels to sustained pressure, accelerating damage11. However, the relationship between diurnal blood pressure patterns and HRV, and the impact of different patterns on hypertensive retinopathy, remain insufficiently defined. This study characterizes ambulatory blood pressure and HRV features across diurnal patterns and evaluates their association with the risk of hypertensive retinopathy, aiming to improve risk stratification for target organ damage and inform early prevention.

Materials and methods

Participants

From September 2023 to June 2025, patients with essential hypertension attending the Departments of General Practice and Cardiology at the 940th Hospital of the Joint Logistic Support Force were screened. A total of 181 eligible patients (88 males, 93 females) were included. Inclusion criteria: meeting diagnostic criteria for hypertension per the 2024 Chinese Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Hypertension12; age 20–70 years; completed valid 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) and 24-hour ambulatory electrocardiography; provided informed consent. Exclusion criteria: secondary hypertension; severe cardiac, hepatic, or renal dysfunction; acute cardiovascular or cerebrovascular events within 3 months; thyroid dysfunction; pregnancy; shift workers; cognitive impairment precluding monitoring; incomplete or poor-quality monitoring data.

Methods

Baseline data collection

Collected variables included sex, age, BMI, hypertension duration, smoking, alcohol use, and antihypertensive medication use. Fasting blood samples were analyzed for total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C).

Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring and grouping

ABPM was performed over 24 h. Measurements were taken every 30 min during daytime (06:00–22:00) and every 60 min during nighttime (22:00–06:00). Extracted indices: daytime mean systolic blood pressure (dSBP), daytime mean diastolic blood pressure (dDBP), nocturnal mean systolic blood pressure (nSBP), nocturnal mean diastolic blood pressure (nDBP), 24-hour mean systolic blood pressure (24hSBP), and 24-hour mean diastolic blood pressure (24hDBP). The nocturnal systolic blood pressure fall rate (SBPF) was calculated as SBPF = (dSBP − nSBP)/dSBP × 100%. Grouping followed consensus recommendations13: SBPF ≥ 10% and < 20% (dipper, n = 57); 0 ≤ SBPF < 10% (non-dipper, n = 62); SBPF < 0% (reverse-dipper, n = 62).

HRV analysis

HRV indices were derived from 24-hour ambulatory ECG. Time-domain indices14: SDNN, the standard deviation of all normal RR intervals over 24 h; SDANN, the standard deviation of the averages of NN intervals in 5-min segments over 24 h; RMSSD, the root mean square of successive differences between adjacent NN intervals; PNN50, the percentage of successive NN intervals differing by > 50 ms. Frequency-domain indices: LF, low-frequency power; HF, high-frequency power; LF/HF ratio.

Diagnosis of hypertensive retinopathy

Diagnostic criteria for hypertensive retinopathy15: (1) history of primary or secondary hypertension; (2) retinal arterial caliber/wall changes and increased vascular permeability leading to retinal lesions (e.g., hemorrhages, exudates) and even optic disc edema on fundus examination; (3) exclusion of other retinal/optic nerve disorders with similar manifestations (e.g., diabetic retinopathy, central retinal vein occlusion, optic disc vasculitis, anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, papilledema due to raised intracranial pressure).

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed using SPSS 27.0. For continuous variables, normality and homogeneity of variance were assessed. Normally distributed data with equal variances are presented as mean ± standard deviation ((\(\:\stackrel{-}{x}\) ± s) and compared across groups with one-way ANOVA; otherwise, data are presented as median (interquartile range) [M (P25, P75)] and compared with the Kruskal–Wallis H test. Post hoc pairwise comparisons used Dunn’s test when overall differences were significant. Categorical variables are expressed as n (%) and compared with the χ2 test. A two-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Multivariable analysis employed logistic regression.

Ethics statement

All methods involving human participants in this study were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and relevant national guidelines and regulations for medical research involving human subjects. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the 940th Hospital of the Joint Logistic Support Force of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army, with the approval number 2024KYLL16. Before participating in the study, all eligible patients were fully informed of the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant to confirm their voluntary participation.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 181 patients were included: 57 dipper, 62 non-dipper, and 62 reverse-dipper. There were no significant differences among groups in age, sex, smoking, alcohol use, medication use, and most laboratory indices ( P > 0.05) (Table 1).

Ambulatory blood pressure indices

Among the ABPM indices, dSBP, dDBP, and 24hDBP showed no significant differences among groups (P > 0.05). nSBP, nDBP, and 24hSBP differed significantly (P < 0.05). Post hoc Dunn tests: nSBP was significantly higher in the reverse-dipper group versus dipper (P < 0.001) and non-dipper (P < 0.001); no difference between dipper and non-dipper. nDBP was significantly higher in the reverse-dipper versus dipper (P = 0.002); other pairwise comparisons were not significant. 24hSBP was significantly higher in the reverse-dipper versus dipper (P = 0.028) and non-dipper (P = 0.022); no difference between dipper and non-dipper (Table 2).

HRV indices

There were significant overall differences in HRV time- and frequency-domain indices among groups (P < 0.05). Post hoc Dunn tests showed that SDNN, SDANN, and LF were significantly higher in the dipper group than in the non-dipper and reverse-dipper groups (all P < 0.001), with no difference between non-dipper and reverse-dipper. RMSSD, PNN50, and HF were significantly higher in the dipper than in the non-dipper group (RMSSD P < 0.001, PNN50 P = 0.013, HF P = 0.016); other pairwise comparisons were non-significant. LF/HF was significantly lower in the reverse-dipper than in the dipper (P < 0.001) and non-dipper (P = 0.032) groups; no difference between dipper and non-dipper (Table 3).

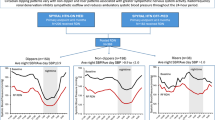

Detection rates of hypertensive retinopathy

Based on fundus examinations, the overall detection rates of hypertensive retinopathy were 3.5% (dipper), 46.8% (non-dipper), and 50.0% (reverse-dipper), with a highly significant difference among groups (χ2=35.066, P < 0.001). The dipper group was significantly lower than the non-dipper (P < 0.001) and reverse-dipper (P < 0.001) groups, while the difference between non-dipper and reverse-dipper was not significant (P = 1.000), (Table 4). The bar chart clearly shows that the detection rate in the dipper group is significantly lower than in the non-dipper and reverse-dipper groups (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1).

Factors associated with hypertensive retinopathy (multivariable logistic regression)

Occurrence of hypertensive retinopathy (1 = yes, 0 = no) was the dependent variable. Independent variables included blood pressure pattern (reference: reverse-dipper), age, sex (reference: female), BMI, 24hSBP, PNN50, and LF/HF (n = 181). BMI was an independent risk factor (OR = 1.131, 95% CI: 1.014–1.261, P = 0.027). Compared with reverse-dipper, the dipper pattern was an independent protective factor (OR = 0.031, 95% CI: 0.006–0.166, P < 0.001). Age, 24hSBP, PNN50, LF/HF, non-dipper (vs. reverse-dipper), and sex were not significant in this model (Table 5). The forest plot intuitively displays the associations of each variable with the risk of hypertensive retinopathy. The OR values (points) and their 95% confidence intervals (horizontal lines) clearly show that, compared with the reverse-dipper, the dipper blood pressure pattern is a significant protective factor, whereas BMI is a significant independent risk factor. The confidence intervals of the other variables all cross the null line (OR = 1), indicating no statistical significance, (Fig. 2).

Discussion

This study systematically compared ambulatory blood pressure and HRV features among dipper, non-dipper, and reverse-dipper patterns in patients with essential hypertension and analyzed their associations with hypertensive retinopathy.

Ambulatory blood pressure features across diurnal patterns

ABPM results showed that nSBP, nDBP, and 24hSBP were highest in reverse-dippers, followed by non-dippers, with dipper patients showing the most favorable profile. Daytime blood pressures did not differ significantly, suggesting that abnormal nocturnal load may be a key driver of target organ damage such as retinal microvascular disease16. Nighttime blood pressure is a stronger predictor of cardiovascular and target-organ outcomes than daytime blood pressure, and the reverse-dipper pattern is closely linked to adverse prognosis. Potential mechanisms include autonomic imbalance—with relatively heightened sympathetic tone and reduced vagal tone—leading to increased nocturnal peripheral resistance and pressure load; abnormal nocturnal activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) may also contribute to absent or paradoxical nocturnal BP fall17. Thus, the abnormally elevated nocturnal load in reverse- and non-dippers may be the key link connecting “abnormal circadian rhythm—autonomic/RAAS imbalance—microvascular damage.”

HRV features across diurnal patterns

As a noninvasive marker of autonomic function, HRV provides important clues to the pathophysiology underlying abnormal BP rhythms. Multiple HRV time- and frequency-domain indices were significantly superior in dipper patients compared with non-dippers and reverse-dippers, indicating more stable and healthier autonomic regulation. This aligns with evidence that reduced HRV predicts adverse cardiovascular events[8]. Notably, the LF/HF ratio was lowest in the reverse-dipper group. Although LF/HF is often used as an index of sympathovagal balance18, its marked reduction may reflect a distinct autonomic imbalance pattern in reverse-dippers—such as relatively lower sympathetic activity or disproportionately elevated vagal tone—differing from the traditional view of sympathetic overactivity in hypertension19. The exact mechanisms warrant further investigation. In patients presenting with non-dipper or reverse-dipper patterns alongside global reductions in SDNN, SDANN, and LF, reversible contributors should be considered (e.g., obstructive sleep apnea, chronic psychological stress, physical inactivity, metabolic abnormalities). Addressing these factors often improves both circadian BP patterns and HRV. Therapeutically, when sympathetic overdrive is evident, beta-blockers or centrally acting antihypertensives may be prioritized, supplemented by nonpharmacological strategies that enhance vagal tone (regular aerobic exercise, breathing/mindfulness training, sleep hygiene). Conversely, in patients with high vagal tone and bradycardia or conduction issues, heart rate–lowering agents should be used cautiously.

Factors associated with hypertensive retinopathy

We observed markedly higher detection rates of hypertensive retinopathy in non-dipper and reverse-dipper patients compared with dipper patients, indicating that absent or paradoxical nocturnal BP fall is a key contributor to retinal vascular damage. Sustained pressure load and hemodynamic alterations may aggravate retinal arteriolosclerosis and leakage10. Multivariable regression further highlighted the dipper pattern as an independent protective factor and elevated BMI as an independent risk factor, consistent with the recognized cardiovascular risk profile of obesity. Obesity may amplify target-organ damage via chronic inflammation, insulin resistance, and activation of RAAS, independently or synergistically with hypertension20. For non-dipper and reverse-dipper patients, a “nighttime BP–first” strategy is recommended, favoring long-acting agents providing smooth 24-hour coverage and, where safe, optimizing dosing time based on individual rhythm characteristics. Structured fundus follow-up (baseline and periodic fundus photography, supplemented by optical coherence tomography when needed) is advised for early detection of microvascular damage. Weight management (caloric control and exercise) should be a core therapeutic target, alongside screening and management of comorbidities (sleep-disordered breathing, metabolic dysregulation, chronic kidney disease) to reduce cumulative microvascular risk.

Limitations include the single-center, cross-sectional design and relatively small sample size, which preclude causal inference. Future large, multicenter prospective studies are needed to validate the long-term impacts of different BP patterns on target-organ damage and to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions targeting abnormal rhythms. For example, assessing whether bedtime dosing of specific antihypertensives to correct diurnal BP rhythm can reduce incident retinopathy would provide more direct evidence for individualized hypertension management. Additionally, the present findings underscore weight control as a key component of comprehensive hypertension management; future work may extend endpoints to other target organs (hypertensive nephropathy, cerebrovascular events) to more comprehensively delineate the prognostic significance of abnormal BP rhythms.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the 940th Hospital of the Joint Logistic Support Force of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the Ethics Committee of the 940th Hospital of the Joint Logistic Support Force of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army.

References

Brouwers, S. et al. Arterial hypertension. Lancet 398(10296), 249–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00221-X (2021).

Kario, K. & Williams, B. Nocturnal hypertension and cardiovascular disease: mechanisms, evidence, and new treatment strategies. Hypertension 78(3), 564–577. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.121.17440 (2021).

Zhao, Y. et al. Heart rate variability and cardiovascular diseases: a Mendelian randomization study. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 54 (1), e14085. https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.14085 (2024).

Fishbein, A. B., Knutson, K. L. & Zee, P. C. Circadian disruption and human health. J. Clin. Invest. 131(19). https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI148286 (2021).

Costello, H. M. & Gumz, M. L. Circadian rhythm, clock genes and hypertension: recent advances in hypertension.Hypertension,2021,78(5):1185–1196. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.121.14519

Geng, Y. J. et al. Circadian rhythms of risk factors and management in atherosclerotic and hypertensive vascular disease: modern Chronobiological perspectives of an ancient disease. Chronobiol. Int. 40(1), 33–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/07420528.2022.2080557 (2023).

Grégoire, J. et al. Autonomic nervous system assessme-nt using heart rate variability. Acta Cardiol. 78(6), 648–662. https://doi.org/10.1080/00015385.2023.2177371 (2021).

Fang, S. C., Wu, Y. L. & Tsai, P. S. Heart rate variability and risk of all-cause death and cardiovascular events in patients with cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Biol. Res. Nurs. 22(1), 45–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/1099800419877442 (2020).

Khan, S. et al. The role of circadian misalignment due to insomnia, lack of sleep, and shift work in increasing the risk of cardiac diseases: a systematic review. Cureus 12(1). https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.6616 (2020).

Dziedziak, J. et al. Impact of arterial hypertension on the eye: a review of the pathogenesis, diagnostic methods, and treatment of hypertensive retinopathy. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 28, e935135–e935131. https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.935135 (2022).

Tsukikawa, M. & Stacey, A. W. A review of hypertensive retinopathy and chorioretinopathy. Clin. Optom.. 67–73. https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTO.S183492 (2020).

Ji-Guang, W. Chinese guidelines for the prevention and treatment of hypertension (2024 revision). J. Geriatric Cardiology: JGC. 22(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.26599/1671-5411.2025.01.008 (2025).

Kario, K. et al. Expert panel consensus recommendatio-ns for ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in asia: the HOPE Asia Net-work. J. Clin. Hypertens. 21(9), 1250–1283. https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTO.S183492 (2019).

Electrophysiology, T. F. O. T. E. S. O. C. T. N. A. S. O. P. Heart rate variability: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Circulation 93(5), 1043–1065. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.93.5.1043 (1996).

Cheung, C. Y. et al. Hypertensive eye disease. Nat. Reviews Disease Primers. 8(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-022-00342-0 (2022).

Del Pozo-Valero, R., Martin-Oterino, J. A. & Rodriguez-Barbero, A. Influence of elevated sleep-time blood pressure on vascular risk and hypertension-mediated organ damage. Chronobiol. Int. 38(3), 367–377. https://doi.org/10.1080/07420528.2020.1835944 (2021).

Parati, G. et al. Nocturnal blood pressure: pathophysiology, measurement and clinical implications. Position paper of the European society of Hypertension. J. Hypertens. 43(8), 1296–1318. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0000000000004053 (2025).

Hayano, J. & Yuda, E. Assessment of autonomic function by long-term heart r-ate variability: beyond the classical framework of LF and HF measuremen-ts. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 40(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40101-021-00272-y (2021).

Seravalle, G. & Grassi, G. Sympathetic nervous system and hypertension: new evidences. Auton. Neurosci. 238, 102954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2022.102954 (2022).

Murray, C. J. L. et al. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet 396(10258), 1223–1249. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30752-2 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express sincere gratitude to Dr. Yurong Li and Dr. Zhe Wang for literature retrieval and other contributions to this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Formal analysis: Hui Li.Project administration: Tianfeng HuangSupervision: Chen Gao.Writing—original draft: Fengping Gong.Writing—review and editing: Chen Gao.All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gong, F., Li, H., Huang, T. et al. Association of diurnal blood pressure patterns with heart rate variability and retinopathy in patients with essential hypertension. Sci Rep 16, 240 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29694-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29694-9