Abstract

Cytoplasmic Male Sterility, a maternally inherited trait which suppresses the production of viable pollen, eliminates the need for detasseling of females in hybrid maize seed production. A set of 88 diverse elite CIMMYT Asia maize inbred lines converted to CMS-C using a temperate donor, were evaluated for stable per se performance for grain yield, male sterility and Turcicum Leaf Blight resistance. Performances of CMS maize hybrids of varied genetic backgrounds across diverse environments -- seasons, years, agroecologies, countries, abiotic- and biotic stresses -- established a stable and robust diversification process which included the identification of potential maintainers and restorers that will benefit researchers, the seed industry and farmers. While multiple CMS hybrids showed a range of yield performances comparable to non-CMS checks, we report on a distinct 9.9% yield advantage of a CMS hybrid compared to its isogenic non-CMS counterpart through a head-to-head analysis. From implications in enhancing global genetic gains to addressing issues of labour availability and rising wages, the technology offers opportunities for intellectual property protection and region-wide taming of tropical Asian maize germplasm diversity by imposing a heterotic discipline.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Male sterility, a failure to produce functional pollen, can result from either a nuclear or mitochondrial gene mutation. Nuclear male sterility is conferred by over 20 mostly recessive nuclear gene mutations1. Cytoplasmic Genetic Male Sterility, commonly referred to as Cytoplasmic Male Sterility (CMS), is conferred by a mitochondrial gene mutation (“ms”)2. CMS has been documented in 140 plant species from 47 genera and 20 families3,4. In maize, the three primary types of CMS are: CMS-C (Charrua cytoplasm), CMS-S (USDA S-type cytoplasm), and CMS-T (Texas cytoplasm)5. The male sterile (“A”) line is maintained by crossing with its isogenic fertile counterpart, the maintainer (“B”) line. The B line itself is maintained by self-pollination like any other maize inbred line (Fig. 1). Restorer (“R”) lines carry nuclear fertility restoration genes (Rf) specific to each type of male sterile cytoplasm which, upon crossing6 with the corresponding CMS line, restore pollen fertility in the F1 hybrid.

Manual or mechanical detasseling remains the primary method for producing hybrid maize seeds, but it is labour-intensive, costly, prone to errors (non-removal of tassel) and can harm plant productivity due to accidental removal of structures like the flag leaf7 which reduce seed yield by about 14%8. By eliminating the need for detasseling, adoption of CMS saves moderate to high labour costs (a primary “use case”) by circumventing the dependence on a labour force which can be very scarce at times of critical field operations. Realizing enhanced seed genetic purity is a well known collateral advantage which has made CMS particularly valuable in crops where emasculation is challenging, thus significantly advancing the use of heterosis in plant breeding9,10.

CMS-T lines are susceptible to Southern Corn Leaf Blight caused by Bipolaris (Helminthosporium) maydis race T11,12. However, it was found to be most stable and best suited for baby corn cultivation as it produced more ears and increased green cob yield13,14. CMS-S line sterility is easily affected by climatic factors15 and are hence less favored. CMS-C is increasingly popular in temperate programs because of its stable sterility, resistance to disease, and positive impact on grain yield15,16,17. Recent advances include marker-assisted backcrossing to develop improved CMS-C lines more efficiently18. Additionally, proprietary systems like Ms44-SPT have demonstrated a 10% yield increase in hybrid maize in sub-Saharan Africa19.

Effective male sterility systems require the inbred female parent to be 100% sterile, while fertility restoration must be reliably achieved in F1 seeds planted by farmers. Of the Rf genes, Rf4 is a dominant restorer gene for maize CMS-C and has significant value in hybrid maize seed production. However, environmental factors, such as temperature and water stress, can influence Rf gene expression. This leads to partial fertility reversion in some genetic backgrounds15 thereby complicating the screening, identification and broader adoption of Rf4-restorer lines which are reportedly scarce20. Addressing this challenge by identifying lines with Rf4 factors, in a wide array of germplasm, is crucial for expanding the use of CMS-C in hybrid breeding programs.

Male sterility in hybrid maize seed production has been used extensively in forming hybrids in the US Corn Belt, China and Brazil while in tropical maize it is largely limited to few hybrids from a couple of large multi-national private sector companies operating in the region with seed occupying less than 3% of the market potential. CMS sources in adapted tropical Asian germplasm were not publicly available until CIMMYT’s Global Maize Program started introgressing the male sterile C-cytoplasm into adapted tropical Asian germplasm in 2016. This was in response to the demand for CMS lines by partners of the International Maize Improvement Consortium for Asia (IMIC-Asia), a CIMMYT-led consortium of public and private partners. CIMMYT’s work—both globally and in Asia—is focused on developing and providing access to diverse stress-resilient germplasm, including OPVs and inbred lines, to such a network of public and private partners. Developing and expanding access to CMS lines, such as those involving Rf4, is integral to this effort. This enables the creation of more resilient hybrid varieties that can address pressing food security and nutritional challenges. Early versions of diverse introgressions were first made available to IMIC-Asia partners in 2020—marking a significant step toward expanding access to this vital trait and strengthening maize hybrid breeding efforts in Asia.

The objectives of this study were to (a) sample a set of elite tropical Asia lines to assess variation in nuclear restorers and maintainers, (b) incorporate male sterile cytoplasm from a temperate source into diverse tropical backgrounds to develop donor lines for CIMMYT and its partners, (c) derive stable CMS-C versions of elite and adapted CIMMYT-Asia lines, and (d) expand our understanding of hybrid performances of a wider set of conversions and demonstrate their utility in hybrid combinations across multiple testers in different agroecological conditions, seasons, climatic stresses, years and countries.

Materials and methods

CMS donors

Two U.S. inbred lines with expired Plant Variety Protection (ex-PVP)—LP1 CMS HT (a male sterile “A” Line) and LP1 NR HT (a maintainer “B” Line) containing Charrua cytoplasm (Cytoplasm C), were obtained from the U.S. North Central Plant Introduction Station (Ames, IA) in 2014. These lines were developed by Pfister Hybrid Corn Company from a selection related to the Minnesota inbred line A632. The A-line was increased by a pairwise cross to the B-line while the B-line was self-pollinated.

Line conversion

A set of 88 elite CIMMYT Asia inbred lines from distinct CIMMYT heterotic groups (HG-A and HG-B) were crossed as male to CMS line LP1 CMS HT in 2016 and 2017. The resulting single crosses were planted in the following season and each tassel was carefully observed for pollen shedding. Crosses that were fully or partially fertile were eliminated, and only those exhibiting 100% male sterility were selected for backcrossing (BC). The sterile plants from each cross were repeatedly backcrossed for several generations, with pollen shedders (lines expressing fertility) eliminated at each stage (noting that during backcrossing, sterility breakdown can occur—perhaps due to high temperature). This process aimed to develop male sterile BC6F1s with at least 98% recovery of the recurrent parent while giving us an opportunity, down the cycles, to eliminate shedders and develop stable male sterility (Fig. 2). A total of 27 elite lines [including Parental Line 1 (PL1) from HG-A and Parental Line 2 (PL2) from HG-B] were successfully converted to their BC6 male sterile versions. Hybrid combinations of CMS conversions of PL1 [PL1-CMSL1 to PL1-CMSL8] were used in a head-to-head comparison with its respective non-CMS version described later in the section. In each BC generation, the plant of the recurrent parent from which pollen was used to cross to the sterile plant/s, was also self-pollinated and designated as the maintainer for that particular BC line variant. These maintainer lines of all BC conversions were planted next to the corresponding BCF1s in the subsequent cycle, and the process was repeated until the desired lines stabilized.

CMS inbred evaluation

The CMS inbred conversions were evaluated in two experiments: an unreplicated observation nursery [Inbred Trial Set 1 (ITS1)] and a replicated yield trial [Inbred Trial Set (ITS2)]. The unreplicated observation nursery consisting of 112 CMS BC4F1 or BC5F1 versions of 22 elite inbred lines were evaluated for Turcicum Leaf Blight (TLB) during the 2022 wet season (July-October) with no inoculation at a disease hot spot (Bengaluru: 12°58′N latitude - and 77°35′E longitude) in single row plots. Due to space logistics and other dynamics of the larger breeding program, we were unable to set up a replicated ITS1 trial; however, information from the observation rows presented here is deemed to be useful to support the bigger objectives of this study. ITS2 was planted at five environments (Table 1) during the 2024 dry season (December-April) under irrigated conditions as described in Section “Trial management and environments” and its respective sub-section and consisted of 13 BC6 CMS lines (PL1-CMSL1 to PL1-CMSL8 and PL2-CMSL1 to PL2-CMSL5), and seven check inbred lines (Table 2).

Hybrid evaluations

Agronomic performance of hybrid combinations of CMS conversions were evaluated in three sets of trials conducted from 2020 to 2024.

Hybrid trial set 1 (HTS1)

Evaluated in 2020, HTS1 consisted of 27 CMS BC4F1 or BC5F1 conversions of three (HG-A: VL107657, VL1110501; HG-B: PL2) elite lines which were crossed to three testers of the opposite group - HG-B (T1, T9, T12). The crosses between the CMS conversions and the testers were made during (wet 2019 – July-November). While balanced crossing of all testers to all lines was attempted, unforeseen physical damage to the plots resulted in lines not being crossed to all testers. In 2020 (wet season - July-November), a total of 42 test crosses along with six non-CMS internal and commercial check hybrids were evaluated under optimal conditions at three environments as described in Section “Trial management and environments” and its respective sub-section. The main objective of this trial was to gather preliminary performance data of this new product concept.

Hybrid trial set 2 (HTS2)

Evaluated in 2022, HTS2 consisted of 14 CMS BC5F1 conversions of 6 additional elite lines (HG-A: PL1, VL107859, VL1110517, VL183005; HG-B: VL18223, VL18430) crossed to 11 testers of the opposite group (HG-A: T3; T6, T7, T8, T10; HG-B: T1, T2, T4, T5, T9, T11). Seed and pollen availability issues resulted in imbalanced crossing (not all lines were crossed to all testers) similar to HTS1. A total of 27 test crosses along with 13 non-CMS internal and commercial check hybrids were evaluated under optimum conditions during the wet season (July-November) at three agroecologically diverse environments in two replicates as described in Section “Trial management and environments” and its respective sub-section. This experiment was primarily done to expand our understanding of hybrid performances of a wider set of conversions across diverse testers and environments in comparison to commercial checks.

Hybrid trial set 3 (HTS3)

HTS3 consisted of hybrids formed between eight CMS lines selected from HTS2 and two testers of the opposite heterotic group. The mating design was a North Carolina Design II (LxT design), where both testers were crossed with all the eight lines. The 16 F1 crosses, non-CMS commercialized isogenic hybrid (PL1/T1), and eight internal and commercial checks, were evaluated in two replications in 2023 and 2024 at nine environments (Table 1) during the wet and dry seasons as described in Section “Trial management and environments” and respective sub-sections of how trials were managed. The nine environments used were selected to capture all conditions typically encountered in the target population of environments. The objectives of this trial were to determine the combining ability of the lines, identify the best version of PL1 and compare it with the isogenic non-CMS version.

Trial management and environments

All trials were conducted in an Alpha lattice design as follows: 32 seeds were sown per entry in each replication having a row length of 4 m with spacing of 60 cm between rows and 20 cm between plants within a row. Final plant population (of 83,333 plants ha− 1) was maintained by thinning extra plants and evaluation was carried out for twenty-one plants per entry in each replication. A detailed description of testing environments is presented in Table 1. A diverse set of environments which varied by environments in India and Nepal, season (wet and dry), management (managed drought, heat, optimal, well irrigated), and years (2020, 2022, 2023, 2024) was selected for this study.

Managed drought

Post-planting, the recommended crop management schedule was followed until the crop reached 550 Growing Degree Days (GDDs), at which point irrigation was stopped (approximately two weeks before flowering). Soil moisture was recorded by using PR2/6 profile probe at different depths (10, 20, 30, 40, 60 and 100 cm) at weekly intervals. The drought stress was terminated by resuming irrigation once the soil moisture at a depth of 30–40 cm reached near permanent wilting point (PWP). Along with soil moisture data, Vapour Pressure Deficit (VPD) was calculated using Tmax after applying the last irrigation. Total accumulated VPD ~ 120.0 kPa from the day after last irrigation to the day of terminating the stress was calibrated and used along with moisture depletion data for taking a decision on terminating the stress.

Heat stress

Hybrids were planted for evaluation in the Spring/Summer of 2023 in such a way that the reproductive growth stage, from tassel emergence to early grain-filling (lag-phase), was exposed to heat stress (Tmax >35 °C, Tmin >23 °C, and RH 35%) in the month of May (rain-free window). Recommended agronomic practices were followed throughout the crop cycle.

Optimal condition

Trials were evaluated in the rainy/wet season with only lifesaving irrigation/s in the event of a prolonged dry spell. Recommended agronomic practices were followed throughout the crop cycle.

Irrigated condition

Trial was evaluated under dry/post-rainy season and provided with irrigation at 8–10 days interval depending on soil type. Recommended agronomic practices were followed throughout the crop cycle.

Data recording and analysis

Data were collected on each plot for field weight (FW) (weight of dehusked ears), days to anthesis (AD) (50% plants with pollen shedding), days to silking (SD) (50% plants with silk emergence), plant height (PH) (height of a plant from ground level to the base of tassel), ear height (EH) (height of a plant to the base of main ear), number of plants (NP) per plot, number of ears (NE) and number of fertile plants (FP) per plot. TLB scores were recorded on a 1–9 scale (1 = immune and 9 = susceptible) at 15 and 30 days after flowering in the unreplicated observation nursery. Grain yield (GY in tons ha−1), anthesis-silking interval (ASI in days), and fertility restoration (FR - percentage of plants with pollen shedding to the total number of plants per plot) were calculated. Residual maximum likelihood analysis was done using META-R software (Multi-Environment Trial Analysis with R)21. Adjusted means were estimated considering genotype effect as a fixed and environment as a random. To get the variances and the heritability, the data was reanalyzed considering genotypes and environments as random. Estimates of general combining ability (GCA) and specific combining ability (SCA) effects were derived from HTS3 using the AGD-R software (Analysis of Genetic Designs in R)22. Head-to-head comparison (Student’s T-test) of a CMS hybrid with its non-CMS version was done in HTS3.

Results

CMS conversion

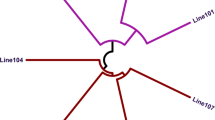

For the CMS conversion process, we selected 88 fixed lines which were parental lines of hybrids that had shown promise in Stages 1 and 2 of hybrid evaluation. After crossing with the CMS donor, only 38 lines were found to be 100% sterile. Fifty lines were found to be restoring fertility after the first cross (Table 3) indicating the presence of nuclear restorer genes. After repeated backcrossing, 27 CMS lines showed stable performance up to BC6 while 11 lines produced shedders in various BC generations (BC2, BC3, BC4) (Fig. 3). A detailed LxT study was conducted on CMS versions of PL1.

Inbred evaluation

The results of the inbred observation nursery, summarized in Table 4, revealed that among the 112 BC5F1 CMS lines tested for TLB, 33 were resistant (score 1.0 to < = 3.0), 27 were moderately resistant (score > 3.0 to 6.0), and 52 were susceptible to TLB (score > 6.0). CMS conversions PL1-CMSL2, PL1-CMSL3, PL1-CMSL4, PL1-CMSL5, PL1-CMSL7 were resistant, while PL1-CMSL1 and PL1-CMSL8 were moderately resistant, and PL1-CMSL6 was susceptible to TLB. These results indicate successful development of CMS-C A-lines for use as seed parents resistant to TLB, thereby alleviating previous concerns regarding the susceptibility of CMS germplasm to TLB and mitigating risks associated with the T-cytoplasm. Per se yields of CMS conversions of PL1 and PL2 were comparable to their non-CMS versions (Table 2). Complementing these results, the inbred trial statistical variances (Supplementary Table 1) revealed that genotypic and genotype-environment interaction variances were not statistically significant for grain yield, indicating lack of genetic variation between the CMS versions and non-CMS elite lines. These results suggest that the introgression of CMS through backcrossing did not alter grain yield of the developed inbred lines, maintaining their agronomic performance while also selecting for TLB resistance. Thus, a preliminary level of diversification of CMS-A lines in Asia tropical germplasm was achieved.

Hybrid evaluation

Hybrid yield performance (HTS1-3)

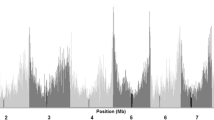

Box and whisker plots (Fig. 4A and B) indicated that the range in yield of CMS hybrids was comparable or better than non-CMS hybrids (including isogenic non-CMS hybrids and commercial checks) across 2–3 environments. “X” with a horizontal line at the center of the box represents the mean, the solid box represents 25th −75th percentile and the vertical lines (whiskers) represent the minimum and maximum of the distribution in box and whisker plots. Likewise, Figs. 5A and 6A indicated comparable to superior grain yield performances of CMS hybrids vis-à-vis non-CMS checks across genetic backgrounds in various environments. In particular, CMS derivatives of VL1110501, PL1 and VL18223 had distinct performance advantages across environments. Figures 5B and 6B indicated that CMS hybrids formed with diverse testers showed grain yield performances which were either comparable or superior to non-CMS checks across environments. Conversions of VL107859 did not yield good hybrids.

Genotype x environment (GxE) interactions

Statistical variance of test crosses of HTS1 (Table 5) and HTS3 (Table 6) showed that variances for genotypes were significant for the traits GY, AD, and FR. This implied that there was ample genetic variance amongst the entries as would be expected in the three different genetic backgrounds of CMS conversions. GxE interaction was significant for GY in HTS3. A sub-partition of the GxE interaction in HTS3 into line x environment (LxE) and tester x environment (TxE) interactions revealed that the GxE interaction was mostly due to the interaction of lines with environments rather than testers with environments. GxE interaction for AD and FR were significant in HTS1 implying that the extent of fertility restoration of a hybrid varied across environments, precisely emphasizing the need for ascertaining stability in FR of hybrids to be advanced/deployed, as done in this study. Between HTS1, HTS2 (Supplementary Table 2) and HTS3, environmental variation was significant for the traits GY, AD and SD indicating the heterogeneity of the environments selected.

Combining ability (GCA/SCA)

GCA effects of HTS3 are presented in Table 7. All the CMS lines showed negative GCA effects for the trait FR except PL1-CMSL8 (4.03%). The highest positive GCA effects for GY were as follows: PL1-CMSL4 (0.53 t ha− 1 – managed drought), PL1-CMSL8 (0.73 t ha− 1 - heat stress), and PL1-CMSL3 (0.51 t ha− 1 - optimal). PL1-CMSL7 had positive GCA effects on GY under all environments with the highest significant GCA effects for GY of 0.43 t ha− 1 under irrigated conditions and 0.38 t ha− 1 across environments, while it had the second highest GCA effect under heat stress (0.58 t ha− 1). Its GCA for FR was negative, but non-significant (−6.22%) but was still higher than many entries (Table 7). PL1-CMSL7 was thus deemed to be the best CMS version of PL1. Highest positive SCA effects for GY were as follows: CMSH9, (0.31 t ha− 1 – across environments), CMSH7 (0.86 t ha− 1 – managed drought), CMSH11 (0.50 t ha− 1 – heat), CMSH12 (1.34 t ha− 1 - optimal), and CMSH9 (0.37 t ha− 1 – irrigated) (Supplementary Table 3).

Fertility restoration and restorer identification

The top yielding hybrids were: CMSH14 (6.46 t ha− 1 – managed drought), hybrid CMSH11 (2.67 t ha− 1 - heat stress), CMSH4 (8.46 t ha− 1 – optimum), and CMSH14 (8.73 t ha− 1 - irrigated) (Table 8). All CMS hybrids with tester T2 had low fertility restoration ranging from 0.8% to 22% across all the environments, despite generally higher grain yield under different managements. Conversely, CMS hybrids with tester T1 showed good fertility restoration ranging from 89.6% to 96.8% across environments. Considering good grain yield with ample fertility restoration, the highest ranking hybrids were CMSH7 (5.42 t ha− 1 - managed drought), CMSH11 (2.67 t ha− 1 - heat stress), CMSH5 (8.31 t ha− 1 – optimal), and CMSH13 (8.29 t ha− 1 - irrigated); all combinations with T1. This result indicated that T1 can be used as a potential restorer in a hybrid breeding program while T2 could be a potential maintainer for CMS line development. This also revealed that the heterotic groups can be formed based on the presence versus absence of restorer genes in the germplasm.

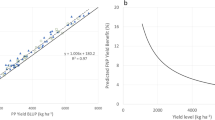

Head-to-Head comparison: CMS vs. Non-CMS

CMSH13 ranked first under irrigation (8.29 t ha− 1), second under managed drought (4.55 t ha− 1) and third under heat stress condition (1.34 t ha− 1) with fertility restoration of 96.7% (the second highest among all CMS hybrids) (Table 8) implying that the hybrid CMSH13 would be the best candidate for advancement and validating the choice of its seed parent PL1-CMSL7 in future crosses. This was supported by its high SCA for GY under optimal (0.27 t ha− 1) and across environments (0.14 t ha− 1) with an SCA for fertility restoration (8.39% - highest among all the hybrids). Head-to-head comparison between CMSH13 (Table 9) and its corresponding non-CMS hybrid (PL1/T1) over seven environments revealed a performance advantage ranging from – 2.4% to 28.7%, with an average superiority of 9.9%. In this study, the performance comparison of CMS vs. non-CMS hybrids across environments yielded a p-value of the t-test of 0.059, indicating a statistically significant superiority of the CMS hybrid at α = 0.1. Environments selected spanned diverse agroecologies, soil types (red and black, sandy to clay), management conditions which included irrigated, drought, heat, and rainfed systems, in different cropping seasons (dry and wet) across years (2023 and 2024) in two countries (India and Nepal). Importantly, the CMS hybrid had good average fertility restoration of 96.7% across environments with the lowest at 84.9% in Environment 10 as described in Table 8.

Discussion

Diversity and stability of male sterility in CMS inbreds

In this study we developed tropical C-cytoplasm CMS seed parents from a temperate germplasm source and demonstrated their utility and stability across a range of genetic backgrounds and environments. While the absence of dominant nuclear restorer genes in an inbred line being converted renders its BC generation sterile (Fig. 2) it is quite common to see the expression of fertility in backcross generations. This breakdown of sterility has been attributed to minor restoration factors (as no known major fertility restorer has been introduced in the process) triggered by environmental effects. Hence, the stability of CMS is key to its utility in commercial hybrid seed production to ensure the purity of the hybrid seed produced. The stable sterility of CMS lines developed in this study (after screening and observing pollen shed in multiple seasons in seed increase nurseries and evaluation in multi-environment trials) was demonstrated in a range of environments. This is the first such report for tropical maize and is especially relevant in the Asian context as countries are looking to reduce seed imports while in-country seed production is being increasingly emphasized to ensure seed-security. In the Indian context, 90% of 220,000 metric tons of maize seed production happens in the coastal region of the state of Andhra Pradesh and national partners and the seed sector are looking to diversify seed production environments. Therefore, any future research studies should focus on identifying minor restoration factors; a research that would help in developing more robust CMS systems. Genomic and metabolomic approaches are suggested.

Secondly, CMS-seed parental lines of the limited number of male sterile hybrids available in the Asian market are believed to have poor local adaptability. This is a point of concern that has been addressed in this study through the introgression of the CMS trait in a range of Asia-adapted genetic backgrounds. As reported, 27 CMS lines showed stable performance at BC6, many of which have already been distributed through IMIC-Asia. This sets the stage for the identification of potential B and R lines across a wider set of genotypes as follow up research.

Stability of fertility restoration in CMS-based hybrids

While this study identified some lines with good restoration, molecular and phenotypic validation of restoration factors using a large set of CIMMYT lines is in progress. Of the 12 restoration factors identified in maize, our focus is on Rf423 as a line of future work which has been primarily found to restore fertility of C-cytoplasm. It should be noted that in CMS hybrids, the potential grain production can be achieved with less than 100% fertility restoration. However, clear reports on the critical minimum level of fertility required in a grain production field are not available. Therefore, to ensure maximum grain production on farmers’ fields, it is a known industry practice to blend CMS hybrids (with less than 100% FR) with their isogenic non-CMS counterparts in commercially sold seed. Breeders have indicated that blended hybrids consist of 50% CMS : 50% isogenic normal hybrid24, while the proportion of CMS could vary between 30 and 70%. To ensure commercial viability of CMS systems with less than 100% FR, commercial blended hybrids should have minimal blending. Determining these commercially-viable farmer-profitable blending ratios is an aspect of field research that has been initiated for the many promising CIMMYT CMS hybrids.

Grain productivity, seed production costs, and dependence on labour

We have shown a 9.9% grain yield advantage of CMSH13 over its non-CMS isogenic counterpart; a huge yield gain realized through the use of a single gene. This is in line with Collinson, Hamdziripi19 who reported a 10% increase in maize grain yield of CMS hybrids in sub-Saharan Africa, a yield benefit provided by CMS hybrids with 50% fertility restoration. While more comparisons of performances of CMS hybrids with their corresponding non-CMS counterparts would validate and strengthen this trend, at the outset CMS hybrids promise to provide significant economic benefits to maize grain farmers.

Limited studies and technical manuals have reported that detasseling accounts for roughly 15–20% of total hybrid maize seed production costs globally which in India it is at least 10%25,26,27. Besides reducing the dependence on scarce labour and its associated costs, a distinct 14% increase in seed yield by CMS inbreds during hybrid seed production was demonstrated by Collinson, Cairns8 in Africa. Validating such a potential through seed production pilots would be valuable to the Asian seed industry. Tropical maize area in South and South-East Asia is estimated to be at least 25 million ha, translating to about 200,000 hectares in seed production area. While Collinson, Hamdziripi19 used the dominant male sterile Ms44-SPT system to show the benefit of male sterility for farmers in Africa, this is the first report in Asia of use of C-cytoplasm for the successful development of a stable CMS hybrid superior to its non-CMS version across a range of environments which includes severe managed drought and heat stresses.

Intellectual property (IP) protection

Inbred parental seed increase and formation of single cross females (for use in producing three-way cross hybrids) usually happens on fields under the direct control of seed companies (either through land ownership or land leased) wherein adequate fencing and security is provided to prevent trespassers (Fig. 1). Certified hybrid seed production moves to (contracted) farmers’ fields where watch-and-ward security is not guaranteed. Chopping down rows of male rows soon after pollination in seed production plots is a widely recognized global practice that enables protection of one half of the hybid IP. However, in many parts of the world, loss of IP has been reported due to theft of seed (either before planting or even soon after - by trespassers digging out planted seed) or due to illegal transfer/hand over of a sample; something that is reportedly rampant in the Asian region. Although most countries have IP protection laws to prevent such pilferage, its implementation is questionable and may be varied. Where three-way crosses are produced (as in Eastern and Southern Africa), the IP of single-cross females are inherently protected. In contrast, IP of both parents of a single-cross are exposed to IP drain. Use of CMS systems gives an opportunity to protect the IP of the seed parent as its maintenance happens on-station by crossing it with the B-line, the access to which is controlled by the legal owner. In other words, even if male sterile parental A-lines seed samples are illegally passed over by the contract seed farmer, they cannot be multiplied without a maintainer, thus protecting the IP of the female side of the hybrid. While this study does not directly address the point being made here, we opine that this will become an important use-case of male sterility in the industry.

Heterotic separation and discipline

The streamlining of US corn belt germplasm groups largely into distinct heterotic groups, mainly the stiff-stalks (BSSS) and the non-stiff stalks (NSSS), has guided temperate breeding for the last 75 years. In comparison, tropical maize has had a shorter history of hybrid improvement of about 30 years, is exposed to a gamut of abiotic and biotic stresses and, is wider in diversity (and so are the possible groups of lines that could give heterosis). Most of the increase of tropical maize area in the last two decades has been in Asia where much of the breeding in the public and the private small and medium sized enterprises has been based on derivation of lines by selfing heterotic (commercial) hybrids. Although this strategy gives good lines per se, heterotic mixing allows only a small chance for new lines to combine well with other lines available within breeding programs. Such dependence on “chance heterosis” coupled with poor record keeping, lack of data management systems, staff turnover, a lack of commitment and motivation to manage data and pedigrees, inadequate research funding (in the public sector), and use of multiple heterotic groups (where it exists) has plagued tropical maize improvement and rendered it chaotic. Although CIMMYT has played its part in demonstrating the importance of heterotic grouping and the systematic need to tame the diversity of tropical maize, abuse of heterotic patterns – that of deriving new inbred lines from across group crosses – persists, mainly due to a lack of intent and effort in applying the concept. Firstly, with the use of CMS a very clear qualitative heterotic pattern of B (maintainer) versus R (restorer) is inherently determined by the presence/absence of Rf factors; unlike in non-CMS systems where the classification of heterotic groups is based on an interpretation of (inherently quantitative measures of) combining abilities for grain yield that can tend towards subjectivity. With an established CMS system, any attempt to derive new inbred lines derived from B x R crosses would eventually hinder the conversion of seed parents of successful hybrids due to the presence of Rf factors in female lines as a result of this intermixing of pools; thus automatically enforcing respect for the B vs. R grouping. In pearl millet, molecular diversity studies in addition to the presence/absence of nuclear restorer genes has guided the classification of breeding lines into two broad-based heterotic pools—B-lines (seed parents) versus R-lines (restorers)28,29,30,31. Hence we believe that, in order to better exploit the diversity of tropical maize and enhance heterosis and genetic gains over a period of time, the separation of lines into female (B) and male (R) groups would force breeding crosses to be made only within such groups, a discipline easy to break if parental lines were amenable to be used either as female or male as in non-CMS pools. In developing and distributing commercially viable CMS lines in a range of diverse genetic backgrounds presented in this study, we believe that a strategic possibility for moving towards an objective B vs. R heterotic grouping, exists in maize. This study sets the stage for the development of CMS systems in a larger array of maize germplasm, not only that of CIMMYT, but of other public and proprietary private sector germplasm as more partners begin the use of tropicalized CMS donor base developed by CIMMYT.

Conclusion

Through this study:

-

1.

A portfolio of CMS-C seed parents and tropicalized CMS donors of diverse genetic backgrounds having stable per se performance for grain yield across various environments in India and Nepal was developed.

-

2.

Stable and consistent performance of genetically diverse CMS-C inbred seed parental lines in multiple tester combinations was proven across a range of environments (diverse agroecologies across India and Nepal, different seasons, varied managed stresses and crop management and across years).

-

3.

A CMS hybrid superior in performance (9.9% grain yield advantage) to its isogenic non-CMS combination was identified.

-

4.

A set of restorers suitable as pollen parents was identified.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request through Dataverse.

References

Neuffer, M. G., Coe, E. H. & Wessler, S. R. Mutants of Maize (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 1997).

Touzet, P. & Budar, F. Unveiling the molecular arms race between two conflicting genomes in cytoplasmic male sterility? Trends Plant. Sci. 9, 568–570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2004.10.001 (2004).

Laser, K. D. & Lersten, N. R. Anatomy and cytology of microsporogenesis in cytoplasmic male sterile angiosperms. Bot. Rev. 38, 425–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02860010 (1972).

Hanson, M. R. & Conde, M. F. Functioning and Variation of Cytoplasmic Genomes: Lessons from Cytoplasmic–Nuclear Interactions Affecting Male Fertility in Plants. In: International Review of Cytology (eds Bourne GH, Danielli JF, Jeon KW). Academic Press (1985). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0074-7696(08)60398-8

Laughnan, J. R. & Gabay-Laughnan, S. Cytoplasmic male sterility in maize. Annu. Rev. Genet. 17, 22. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ge.17.120183.000331 (1983).

Levings, C. S. Thoughts on cytoplasmic male sterility in cms-T maize. Plant. Cell. 5, 1285–1290. https://doi.org/10.2307/3869781 (1993).

Czepak, M. P. et al. Effect of artificial detasseling and defoliation on maize seed production. Int. J. Plant. Soil. Sci. 28, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.9734/ijpss/2019/v28i430114 (2019).

Collinson, S. et al. Ms44-SPT: unique genetic technology simplifies and improves hybrid maize seed production in sub-Saharan Africa. Sci. Rep. 14, 32125. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83931-1 (2024).

Chen, L. & Liu, Y. G. Male sterility and fertility restoration in crops. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 65, 579–606. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-arplant-050213-040119 (2014).

Wan, X., Wu, S. & Xu, Y. Male sterility in crops: application of human intelligence to natural variation. Crop J. 9, 1219–1222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cj.2021.11.001 (2021).

Wise, R. P., Bronson, C. R., Schnable, P. S. & Horner, H. T. The Genetics, Pathology, and Molecular Biology of T-Cytoplasm Male Sterility in Maize. In: Advances in Agronomy (ed Sparks DL). Academic Press (1999). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2113(08)60911-6

Tatum, L. A. The Southern corn leaf blight epidemic. Science 171, 1113–1116. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.171.3976.1113 (1971).

Pal, S. et al. Molecular characterization of T-, C- and S- specific cytoplasmic male sterile (CMS) maize inbreds using mitochondrial SSRs for its utilization in baby corn breeding. Mol. Biol. Rep. 52, 520. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-025-10624-x (2025).

Pal, S. et al. Influence of T-, C- and S- cytoplasms on male sterility and their utilisation in baby corn hybrid breeding. Euphytica 216, 146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10681-020-02682-y (2020).

Weider, C. et al. Stability of cytoplasmic male sterility in maize under different environmental conditions. Crop Sci. 49, 77–84. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci2007.12.0694 (2009).

Stevanovic, M. et al. The application of protein markers in conversion of maize inbred lines to the cytoplasmic male sterility basis. Genetika 48, 691–698 (2016).

Wang, Y., Tong, L., Liu, H., Li, B. & Zhang, R. Integrated metabolome and transcriptome analysis of maize roots response to different degrees of drought stress. BMC Plant. Biol. 25, 505. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-025-06505-x (2025).

Patil, A. et al. Transfer of cytoplasmic male sterility to the female parents of heat- and drought-resilient maize (Zea Mays L.) hybrids. Agronomy 15, 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15010098 (2025).

Collinson, S. et al. Incorporating male sterility increases hybrid maize yield in low input African farming systems. Commun. Biol. 5, 729. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-022-03680-7 (2022).

Bohra, A., Jha, U. C., Adhimoolam, P., Bisht, D. & Singh, N. P. Cytoplasmic male sterility (CMS) in hybrid breeding in field crops. Plant. Cell. Rep. 35, 967–993. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00299-016-1949-3 (2016).

Alvarado, G. et al. META-R (Multi Environment Trail Analysis with R for Windows) Version 6.04) (CIMMYT Research Data & Software Repository Network, 2015).

Rodríguez, F., Alvarado, G., Pacheco-Gil, R. Á., Crossa, J. & Burgueño, J. AGD-R (Analysis of Genetic Designs with R for Windows) Version 5.0. (eds International M, Wheat Improvement C). V15 edn. CIMMYT Research Data & Software Repository Network hdl:11529/10202 (2015).

Jaqueth, S. J. et al. Fertility restoration of maize CMS-C altered by a single amino acid substitution within the Rf4 bHLH transcription factor. Plant. J. 101, 101–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.14521 (2020).

Havey, M. J. The Use of Cytoplasmic Male Sterility for Hybrid Seed Production. In: Molecular Biology and Biotechnology of Plant Organelles: Chloroplasts and Mitochondria (eds Daniell H, Chase C). Springer Netherlands (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-3166-3_23

APHIS. Petition for Determination of Nonregulated Status for Maize Genetically Engineered for Male Sterility and Restorer Capability (Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, USDA, 2010).

MacRobert, J. F., Setimela, P. S., Gethi, J. & Regasa, M. W. Maize Hybrid Seed Production Manual.). Mexico, D.F.: (2014).

Ghețe, A. B. et al. Influence of detasseling methods on seed yield of some parent inbred lines of Turda maize hybrids. Agronomy 10, 729. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy10050729 (2020).

Kapila, R. K. et al. Genetic diversity among Pearl millet maintainers using microsatellite markers. Plant. Breed. 127, 33–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0523.2007.01433.x (2008).

Nepolean, T. et al. Genetic diversity in maintainer and restorer lines of Pearl millet. Crop Sci. 52, 2555–2563. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci2011.11.0597 (2012).

Gupta, S. K. et al. Patterns of molecular diversity in current and previously developed hybrid parents of Pearl millet [Pennisetum glaucum (L.) R. Br]. Am. J. Plant. Sci. 6, 1697–1712. https://doi.org/10.4236/ajps.2015.611169 (2015).

Gupta, S. K. et al. Identification of heterotic groups in South-Asian-bred hybrid parents of Pearl millet. Theor. Appl. Genet. 133, 873–888. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-019-03512-z (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the funding received from various sources for the research and publication of this article: the International Maize Improvement Consortium for Asia (IMIC-Asia), the CGIAR Research Program (CRP) MAIZE and the CGIAR Accelerated Breeding Initiative. The contribution of Desika Saravanan in generating R-scripts for box and whisker plots is acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Satish A. Takalkar – Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing; S. Murali Mohan - Investigation, Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Supervision; P. Nagesh - Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing; T. Dhliwayo – Sourcing of CMS donor germplasm, Methodology, Writing – review & editing; P. Bhaskara Naidu - Investigation, Supervision; S.C. Boregowda - Investigation, Supervision; Rajashekar M. Kachapur - Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing; Dinesh G. Kanwade - Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing; P. Mahadevu - Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing; N.K. Singh - Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing; Sudhir Kumar Injeti - Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing; Manjunatha B. Kariganur - Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing; Santosh K. Pattanashetti - Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing; B.G. Ravindra - Investigation, Supervision; Bindiganavile S. Vivek - Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Supervision, Formal analysis, Validation, Visualization, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Takalkar, S.A., Mohan, S.M., Nagesh, P. et al. Diverse and stable male sterile tropical Asian maize inbred lines provide strategic opportunities for hybrid development. Sci Rep 16, 344 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29738-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29738-0