Abstract

This study aimed to develop a machine learning model for accurately predicting postoperative VTE risk in these patients. The data of this study retrospectively collected the inpatients of cervical cancer in the Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Chongqing University from January 2020 to December 2023. We utilized 1,044 observations and six variables to develop seven machine learning (ML) models and selected the best-performing model for assessing postoperative venous thromboembolism (VTE) risk. The models were evaluated using ROC, PR, and DCA curves, and the prediction of the model’s process was explained using SHAP values. Among 1,044 postoperative cervical cancer patients, 82 (7.85%) developed VTE. Seven machine learning algorithms were developed and evaluated, with the random forest (RF) model showing the best overall performance (AUC = 0.852, AUPR = 0.332). Compared with other models, including logistic regression (AUC = 0.767) and XGBoost (AUC = 0.836), the RF model demonstrated superior discrimination, calibration, and generalizability. Decision curve analysis confirmed that the RF model yielded the highest net clinical benefit across a wide range of threshold probabilities (5–80%). SHAP analysis revealed that D-dimer, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), and age were the most influential variables, indicating their substantial contributions to model prediction. Our study suggests that machine learning algorithms can be practical tools for postoperative VTE risk assessment and can learn from patient characteristics to provide personalized evaluations. The RF model outperformed the other six algorithms evaluated. We developed the final RF model as a user-friendly web tool for healthcare professionals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cervical cancer, a malignant tumor of the cervix, imposes a significant burden on the health of patients, their families, and society at large. Indeed, the combined burden of cervical cancer in China and India constitutes one-third of the global burden1. It is estimated that there are more than 604,342 new cases and deaths from cervical cancer worldwide annually2. Venous thromboembolism (VTE), encompassing pulmonary embolism (PE) and deep venous thrombosis (DVT), occurs in cancer patients at a rate approximately five times greater than that of the general population. In the context of cervical cancer treatment, VTE is a common and potentially fatal complication that severely affects treatment outcomes and patient prognosis. VTE not only exacerbates the burden of cervical cancer but is also a significant cause of mortality3. Establishing an effective model allows for the periodic assessment of postoperative VTE risk in cancer patients, facilitating the provision of personalized clinical interventions to enhance treatment efficacy and patient prognosis4,5.

The Khorana score, the earliest and most widely adopted tool for assessing VTE risk in cancer patients, has inspired the development of several modified tools, including the Vienna score, PROTECHT score, and ONKOTEV score. However, these tools have demonstrated suboptimal performance in the individualized VTE risk assessment6,7. The Khorana score was originally derived from a cohort of ambulatory patients with solid tumors receiving chemotherapy; therefore, its performance in other clinical settings, such as postoperative cancer patients, is suboptimal. Moreover, this score incorporates only a limited set of variables (tumor type, platelet count, hemoglobin level, white blood cell count, and body mass index), which cannot fully capture the multifactorial nature of VTE risk. In addition, the risk factors for VTE vary considerably among different cancer types, whereas these tools lack cancer type specificity and may not adequately reflect VTE risk in cervical cancer patients8.

More and more studies are beginning to use machine learning (ML) to assess the VTE risk of cancer patients. Santi RM et al.9 developed a tool that integrates the Khorana score with non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) characteristics to predict VTE risk in NHL patients, achieving effective results. Jin S et al.10 created a cancer-related VTE prediction model via machine learning and clinically available indicators and compared its performance with the traditional Khorana score. These findings indicated that the machine learning model outperformed the Khorana score in predicting cancer-related VTE risk. Additionally, the inclusion of the D-dimer indicator was found to enhance the model’s predictive performance. Frere C11 conducted an extensive literature review on VTE in patients with pancreatic cancer and concluded that existing cancer-related risk assessment tools, such as the Khorana score, CATS/MICA score, and Caprini score, were ineffective in predicting VTE risk in patients with pancreatic cancer. Notably, an increasing number of studies are employing machine learning methods to predict cancer-related VTE risk, with the results suggesting that these methods offer superior predictive efficacy compared with traditional risk assessment tools.

Compared with the Khorana score, ML offers several advantages for assessing the risk of VTE in cancer patients12. First, ML algorithms are capable of capturing complex nonlinear relationships and higher-order interactions among multiple clinical variables, which traditional statistical methods may fail to adequately model. Second, recent advances in interpretable ML techniques, such as the SHAP values used in our study, not only improve predictive accuracy but also enhance interpretability, enabling clinicians to understand the contribution of each risk factor to the prediction. Third, with the advancement of ML deployment technologies, these models can be implemented in user-friendly web-based tools, allowing clinicians to perform real-time, individualized VTE risk assessments at the bedside, thereby supporting more precise prevention and treatment strategies. Collectively, these developments make ML a powerful and effective approach for VTE risk stratification in cancer patients. Consequently, for the assessment of postoperative VTE risk in cervical cancer patients, we chose to develop a machine learning model using clinical cohort data from postoperative cervical cancer patients rather than relying on conventional tools for evaluating postoperative VTE risk in cancer patients.

There is a close association between age, body mass index (BMI), FIGO stage, surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, white blood cell count (WBC), platelet count (PLT), D-dimer, and the risk of VTE in cervical cancer patients13,14,15,16. The predictive performance could be improved by adding the above indicators to the model. Therefore, to construct an effective predictive model, this study utilizes the aforementioned indicators, along with specific demographic characteristics of patients and clinically available parameters, to construct seven machine learning models: logistic regression (LR), random forest (RF), neural network (NN), eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), gradient boosting machine (GBM), support vector machine (SVM) and adaptive boosting (AdaBoost). We will then select the model with the best overall performance to serve as our tool for VTE risk assessment in postoperative cervical cancer patients. This tool can be used to assess the risk of postoperative VTE in cervical cancer patients, providing a reference for healthcare professionals when formulating personalized interventions for patients.

Data collection

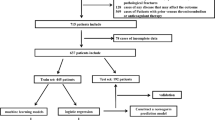

Data for this study were extracted from the electronic medical records of cervical cancer patients who underwent surgery from January 2020 to December 2023. The following inclusion criteria: (1) pathological confirmation of cervical cancer, (2) receipt of surgical treatment, and (3) availability of comprehensive case information encompassing preoperative status, surgical procedures, and results of additional tests. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) age under 18 years, (2) prior history of VTE due to reasons other than cervical cancer, and (3) the presence of secondary cervical cancer or another primary malignant tumor. After applying these criteria, data from 1044 patients were initially included. Figure 1 shows the flowchart of this study.

Data collection details

In alignment with existing research and clinical expertise, we collected data on the following indicators: age, BMI, marital status, pathological tumor type, FIGO stage (I-IV), surgical approach (transabdominal, laparoscopic, or robotic), radiotherapy, chemotherapy, targeted therapy, immunotherapy, WBC, PLT, D-dimer level, neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), and beta2-microglobulin level, as well as the duration of surgery.

Sample size

Empirical evidence suggests that logistic regression analysis requires a sample size at least ten times the number of feature variables to ensure model stability17. While no standard guidelines exist for the minimum sample size in machine learning, our model development cohort included 62 positive cases, and we limited the number of variables to 62 or fewer to maintain the reliability of our results.

VTE diagnosis

The primary outcome measure was a diagnosis of either DVT or PE. Diagnoses were established through vascular ultrasound, computed tomography (CT) angiography, CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA), or enhanced chest CT scans. Two experienced clinicians independently evaluated these results, and any discrepancies in their assessments were discussed collectively to reach a consensus.

Model building and evaluation

The dataset was divided into training and testing sets at a 7:3 ratio, with continuous variables normalized based on the training set’s range. We constructed seven machine-learning classification models, utilizing stepwise regression and expert knowledge to select variables. Hyperparameter tuning was performed via a random search and tenfold cross-validation. The optimal prediction threshold was determined via the Youden index. Model performance was evaluated via receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, the area under the curve (AUC), precision-recall (PR) curves, the area under the curve (AUPR), the matthews correlation coefficient (MCC), the Brier score, and decision curve analysis (DCA). We conducted a comprehensive analysis of the most suitable model via SHAP values. A flowchart detailing the model construction and validation process is provided in Fig. 2.

Statistical analysis

A forest plot was generated to depict patient characteristics and the outcomes of stepwise regression analysis. Continuous variables are expressed as the means ± standard deviations (SD) or medians with interquartile range (IQR) based on their normality, whereas categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages. Where appropriate, group differences for categorical variables were assessed via the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test. The t-test or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was applied for continuous variables, depending on the data distribution. For missing data, variables with a missing rate ≥ 10% were excluded from the analysis. For variables with a missing rate < 10%, multiple imputation was performed using the “mice” package in R. This method generates complete datasets by constructing multiple imputation models, thereby reducing bias caused by missing data and improving the completeness and robustness of the analysis. During feature selection and model training, bias analysis was conducted to ensure that the model was not affected by differences in the scale or distribution of specific features. All the statistical analyses were performed via R software, version 4.3.1 (https://www.r-project.org/), with a p-value less than 0.05 indicating statistical significance. The primary R package “caret 6.0.94” was used for model construction, and additional packages, including “ggplot2 3.4.3”, “ROCR 1.0.11”, “DALEX 2.4.3”, “rms 6.7.0”, “dcurves 0.4.0”, and “fastshap 0.1.1”, were utilized for visualizing model performance. The “shiny 1.7.5” package facilitated the deployment of an interactive web tool to refine the model, accessible at the following link: https://huzuhai.shinyapps.io/CervicalVTE/.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the 1,044 patients included in this study are depicted in Fig. 3. Within the study’s timeframe, VTE was observed in 82 patients, representing 7.85% of the sample. Univariate analysis revealed statistically significant differences in age, NLR, beta2-microglobulin, D-dimer, pathological type, tumor FIGO stage (I‒IV), radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and surgery time between patients who did and did not experience VTE. The dataset was randomly partitioned into a training set, comprising 731 cases, and a test set, comprising 313 cases, at a ratio of 7:3, as illustrated in Fig. 3.

Model development and performance assessment

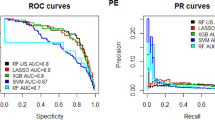

By performing stepwise regression and expert consultation, we identified the optimal variables for predicting postoperative VTE risk, which included age, tumor FIGO stage, pathological type, chemotherapy, D-dimer, and the NLR. We then developed seven machine learning models using the training set and assessed their performance using the test set. Hyperparameter tuning was conducted via a random search, with the 10-fold cross-validation (CV) results for different hyperparameters. The ROC curves and corresponding AUC values for the test dataset are presented in Fig. 4A; Table 1. The AUC values for the LR, RF, NN, XGBoost, GBM, SVM, and AdaBoost models were 0.767, 0.852, 0.787, 0.836, 0.803, 0.739, and 0.764, respectively. The PR curves and AUPR values are displayed in Fig. 4B; Table 1, with AUPR values of 0.205, 0.332, 0.248, 0.367, 0.310, 0.171, and 0.311 for the respective models. The Brier score, calibration intercept, MCC, and calibration slope are also provided in Table 1.

Figure 4A shows the ROC curves of the models, while Fig. 4B presents the PR curves, which are particularly informative for evaluating model performance on imbalanced datasets. The area under the PR curve is significantly higher than that of random guessing, as defined by the proportion of positive samples18. Figure 4C illustrates the DCA curves, indicating that although the models’ net benefits are comparable at threshold probabilities below approximately 10%, the RF, XGBoost, and GBM models exhibit significantly higher net benefits at thresholds exceeding 10%. Notably, the RF models maintain positive clinical utility across a wide range of threshold probabilities (from approximately 5% to 80%), particularly standing out in their practical application value19,20. Figure 4D presents the model’s calibration curve. Due to the low incidence rate of positive cases, both actual and predicted probabilities are concentrated on the lower side. It can be seen that there is acceptable consistency between predicted and actual probabilities, with the calibration curve closely following the diagonal line. By plotting the confusion matrix of each ML model on the validation set, we can clearly compare the prediction effects of the models. We present the results in detail in Figure S1, which indicate that the RF model has a good prediction effect.

Model interpretation

Figure 5A displays a SHAP beeswarm plot for the RF model, in which SHAP values represent the contribution of each variable to the model’s predictions. Positive SHAP values indicate an increased probability of VTE, while negative values suggest a decreased probability21. Among the variables, D-dimer, NLR, and Age emerge as the top three most influential predictors of VTE risk. D-dimer is distributed away from the area near SHAP value 0, indicating a substantial influence on prediction outcomes. In contrast, NLR and Age show more clustered distributions, suggesting relatively more minor yet consistent contributions to the model’s predictions. Figure 5B presents a web-based cervical cancer risk assessment tool. Enter patient characteristics at the provided URL to get their risk prediction. The tool also offers threshold - based advice, explains predictions via SHAP values, and identifies features with abnormal contributions. This helps doctors decide how to prevent VTE in patients.

Figure 5C provides an example of the RF model’s ability to predict postoperative VTE risk for a patient of interest. For Patient ID 1, the RF model’s average predicted risk is 0.077, influenced by factors such as a D-dimer level > 0.5 (contributing 0.033), an NLR of 2.10 (-0.015), age 72 years (0), no chemotherapy (-0.003), SCC (-0.02), and stage III-IV disease (0.009). The final predicted risk for ID 1 is 0.081, which is based on the ordered contributions of D-dimer, NLR, age, Chemotherapy, pathologic type, and stage. Importantly, this process assumes an additive model where each predictor’s effect is aggregated. The ordering of features influences their contribution to the prediction’s decomposition. Figure 5D illustrates how the contributions vary under different ordering schemes, with bar plots and box plots showing the magnitude and distribution of these contributions, respectively. Despite the impact of the order, a D-dimer level > 0.5 and stage III-IV FIGO classification are the primary reasons for the predicted risk of ID 1 exceeding the average. Figures 5D depict how the prediction changes with variations in individual variables while holding others constant. An increase in ID 1, underscoring the need to manage their NLR and D-dimer levels to mitigate postoperative VTE risk.

Risk prediction model interpretation and web tool interface display. (A) SHAP explanation plot for the model. (B) Interface display of the web-based prediction tool. (C) Interpretation of the prediction results for patient ID 1. (D) Assessment of feature contributions to the prediction for patient ID 1.

Discussion

Our investigation, corroborated by prior studies, demonstrated that leveraging real-world data from a substantial cohort of cervical cancer patients and applying machine learning models to assess VTE risk can achieve more precise and cost-effective outcomes than traditional risk assessment methods, such as the Khorana and Caprini scores22,23,24. The risk of VTE varies significantly across different cancer types and populations6. To increase the precision of VTE risk assessment among cervical cancer patients, we developed seven distinct machine-learning models to select the most efficacious model for postoperative VTE risk assessment in this patient group.

By partitioning the dataset into a 70% training set and a 30% testing set, adhering to a 7:3 ratio, we utilized the training set for model development and subsequent evaluation of the testing set. The random search method and 10-fold cross-validation were used to fine-tune the models’ hyperparameters, which involved segmenting the training data into ten equal parts. Each part served as a validation dataset, which was used to assess model performance across various hyperparameter configurations, whereas the remaining data were used for model training. This approach helps mitigate the risk of overestimating the model’s performance.

Our findings align with those of Nudel J, Kumar SB, Sheng W, and others, who identified the RF or XGBoost models as optimal for VTE risk assessment in patients25,26,27. In our analysis, the RF model demonstrated robust performance. Comprehensive evaluation metrics, including the AUC and AUPR, were utilized to assess model performance. The RF model emerged as the superior performer after a thorough evaluation that included DCA, AUC, and AUPR. Consequently, the RF model was designated as the optimal tool for postoperative VTE risk assessment in cervical cancer patients. The RF model’s 10-fold CV AUC (SD) was 0.832 (0.076) on the training dataset, with an AUC and AUPR of 0.852 and 0.332 on the testing dataset, respectively. The superior performance of the RF model can be attributed to its ensemble structure, which aggregates the results of multiple decision trees to reduce variance and enhance robustness against overfitting. This structure enables RF to capture complex nonlinear relationships between predictors and VTE risk while maintaining stable generalization to unseen data.

The DCA curve, established using the test set, clearly delineates the net benefit provided by the RF model across different thresholds28. The curve indicates that the RF model offers a more significant net benefit than a blanket clinical intervention strategy or a complete absence thereof.

SHAP analysis revealed that D-dimer, NLR, and age are the most significant predictors of postoperative VTE risk in cervical cancer patients. Notably, D-dimer was identified as the predominant predictor, with higher concentrations correlating with increased SHAP values and an elevated risk of VTE. This finding underscores the strong positive correlation between D-dimer levels and the risk of postoperative VTE.

Previous studies have identified D-dimer as a biomarker of the fibrinolytic process, where elevated levels indicate a hypercoagulable state and active fibrin formation, particularly in the postoperative period. This hypercoagulable state and fibrin formation substantially increase the risk of VTE in patients. In line with these findings, the study by Chen et al. incorporated D-dimer as a strong predictive factor for VTE risk and achieved favorable predictive performance (C-Index = 0.757)29. The study by Trinh H demonstrated that the NLR, as a marker of systemic inflammation, reflects an enhanced neutrophil-mediated proinflammatory state accompanied by a reduction in lymphocyte-mediated immune surveillance. This imbalance is closely associated with tumor-related thrombogenesis. The preoperative NLR in the VTE group was significantly higher than that in the non-VTE group (5.76 ± 5.66 vs. 3.46 ± 3.41, P < 0.001)30. Older age is often associated with reduced physical function and delayed postoperative recovery, making it an independent risk factor for postoperative VTE. A large-scale study based on the Korean National Health Insurance database (n = 49,514) reported that for every 5-year increase in age, the risk of VTE increased by 13.6% (HR = 1.136, 95% CI: 1.100–1.173)14. Moreover, advanced age frequently coexists with comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases, as well as with factors like open surgery and elevated D-dimer levels, which collectively contribute to a higher risk of VTE. Accordingly, several studies have found that incorporating age as a continuous variable in VTE risk prediction models can significantly improve the predictive accuracy of these models31. Chemotherapy has been identified as an independent risk factor for postoperative VTE in cervical cancer patients, particularly in those receiving adjuvant chemotherapy or concurrent chemoradiotherapy containing cisplatin. Platinum-based regimens (cisplatin/carboplatin) and taxane agents can directly induce DNA strand breaks and oxidative stress, leading to apoptosis of vascular endothelial cells. This process exposes subendothelial collagen and stimulates the release of von Willebrand factor (vWF). Meanwhile, activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway in monocytes upregulates tissue factor (TF) expression by three- to fivefold, triggering the extrinsic coagulation cascade. Consequently, the levels of thrombin–antithrombin complex (TAT) and D-dimer increase after chemotherapy, ultimately resulting in a markedly elevated risk of VTE in these patients32,33. Patients with squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the cervix are generally more sensitive to chemotherapy and are therefore more likely to receive postoperative cisplatin-based concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Since chemotherapy itself is a recognized risk factor for VTE, SCC patients tend to have a higher risk of developing VTE compared with non-SCC patients who undergo surgery alone.

However, this study has several limitations. First, it was conducted at a single center, and although the sample size was sufficiently large, all participants were recruited from the same hospital, which may limit the generalizability of the model. In future work, we plan to conduct a multicenter prospective cohort study based on this research to expand the sample sources and perform a more comprehensive validation of the model, thereby ensuring its clinical applicability. Second, our analysis did not account for certain treatment-related constraints, such as the potential impact of specific surgical or adjuvant therapeutic techniques. In addition, imaging and genomic data were not considered in the current study, which may restrict the applicability of our findings across different clinical settings. In future studies, we intend to incorporate these treatment-related factors, imaging features, and genomic information as predictive variables. Although this will increase research costs, it will undoubtedly enhance the accuracy of the model. Finally, hyperparameter tuning in this study was performed using random search. While this method is simple and commonly used, it may be less efficient than advanced optimization approaches. Future research could employ Bayesian optimization or other automated hyperparameter tuning strategies to improve efficiency and potentially achieve better model performance.

Conclusion

In this study, we developed and compared seven machine learning models, ultimately identifying the RF model as the most effective for assessing postoperative VTE risk in cervical cancer patients. This model outperforms traditional risk assessment tools, such as the Khorana and Caprini scores, as evidenced by its superior performance metrics, including DCA, AUC, and AUPR. Integrating patient-specific data in our model enhanced the accuracy of postoperative VTE risk assessment, enabling more personalized evaluations. These findings provide clinicians with valuable insights to inform treatment decisions and improve patient outcomes.

Data availability

The code used for the analysis in this study is publicly available on GitHub at https://github.com/huzuhai/Cervical-cancer. The datasets analyzed are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions but may be requested from the corresponding author.

References

Adiga, D. et al. Molecular landscape of recurrent cervical cancer. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 157, 103178 (2021).

Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71 (3), 209–249 (2021).

Fernandes, C. J. et al. Cancer-associated thrombosis: the when, how and why. Eur. Respir. Rev. 28 (151) (2019).

Key, N. S. et al. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis and treatment in patients with cancer: ASCO clinical practice guideline update. J. Clin. Oncol. 38 (5), 496–520 (2020).

Schrag, D. et al. Direct oral anticoagulants vs Low-Molecular-Weight heparin and recurrent VTE in patients with cancer: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 329 (22), 1924–1933 (2023).

Khorana, A. A. et al. Prediction and prevention of Cancer-Associated thromboembolism. Oncologist 26 (1), e2–e7 (2021).

Yan, A. R. et al. Risk factors and prediction models for venous thromboembolism in ambulatory patients with lung cancer. Healthcare (Basel) 9 (6) (2021).

Cella, C. A. et al. Comparison of Khorana vs. ONKOTEV predictive score to individualize anticoagulant prophylaxis in outpatients with cancer. Eur. J. Cancer. 209, 114234 (2024).

Santi, R. M. et al. PO-03 - Khorana score and histotype predict the incidence of early venous thromboembolism (VTE) in Non hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). A pooled data analysis of twelve clinical trials of Fondazione Italiana linfomi (FIL). Thromb. Res. 140 (Suppl 1), S177 (2016).

Jin, S. et al. Machine learning predicts cancer-associated deep vein thrombosis using clinically available variables. Int. J. Med. Inf. 161, 104733 (2022).

Frere, C. Burden of venous thromboembolism in patients with pancreatic cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 27 (19), 2325–2340 (2021).

Jiang, T. et al. Development and validation of a machine learning-based early warning system for predicting venous thromboembolism risk in hospitalized lymphoma patients undergoing chemotherapy: a multicenter and retrospective cohort study. Front. Oncol. 15, 1566905 (2025).

Speed, V. et al. Venous thromboembolism and women’s health. Br. J. Haematol. 183 (3), 346–363 (2018).

Yuk, J. S. et al. Incidence and risk factors of VTE in patients with cervical cancer using the Korean National health insurance data. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 8031 (2021).

Zhao, H. et al. Incidence and risk factors of perioperative venous thromboembolism in patients with cervical cancer. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 16 (6), 108 (2022).

Neto, B. V. et al. Thrombogenesis-associated genetic determinants as predictors of thromboembolism and prognosis in cervical cancer. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 9519 (2023).

Peduzzi, P. et al. A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 49 (12), 1373–1379 (1996).

Grdinic, A. G. et al. Developing a machine learning model for bleeding prediction in patients with cancer-associated thrombosis receiving anticoagulation therapy. J. Thromb. Haemost. 22 (4), 1094–1104 (2024).

Vickers, A. J. & Elkin, E. B. Decision curve analysis: a novel method for evaluating prediction models. Med. Decis. Mak. 26 (6), 565–574 (2006).

Van Calster, B. et al. Reporting and interpreting decision curve analysis: A guide for investigators. Eur. Urol. 74 (6), 796–804 (2018).

Lu, C. et al. Predicting venous thrombosis in osteoarthritis using a machine learning algorithm: A population-based cohort study. J. Pers. Med. 12 (1) (2022).

Hampe, N., Wolterink, J. M. & Van Velzen, S. G. Machine learning for assessment of coronary artery disease in cardiac CT: A survey. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 6, 172 (2019).

Nafee, T. et al. Machine learning to predict venous thrombosis in acutely ill medical patients. Res. Pract. Thromb. Haemost. 4 (2), 230–237 (2020).

Wendelboe, A. et al. Exploring the applicability of using natural language processing to support nationwide venous thromboembolism surveillance: model evaluation study. JMIR Bioinform. Biotech. 3, 1 (2022).

Kumar, S. B. et al. Is laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy safer than laparoscopic gastric bypass? A comparison of 30-day complications using the MBSAQIP data registry. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 14 (3), 264–269 (2018).

Nudel, J. et al. Development and validation of machine learning models to predict Gastrointestinal leak and venous thromboembolism after weight loss surgery: an analysis of the MBSAQIP database. Surg. Endosc. 35 (1), 182–191 (2021).

Sheng, W. et al. Development and validation of machine learning models for venous thromboembolism risk assessment at admission: a retrospective study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 10, 1198526 (2023).

Zhang, Z. et al. Decision curve analysis: a technical note. Ann. Transl Med. 6 (15), 308 (2018).

Chen, Y. et al. Development and validation of a nomogram for predicting venous thromboembolism risk in post-surgery patients with cervical cancer. World J. Surg. Oncol. 22 (1), 354 (2024).

Trinh, H. et al. Prognostic value of changes in neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR) for patients with cervical cancer undergoing definitive chemoradiotherapy (dCRT). Clin. Chim. Acta. 510, 711–716 (2020).

Soochit, A. et al. Impact of different post-operative treatment modalities on long-term outcomes in international federation of gynecology and obstetrics (FIGO) 2018 stage IIICp cervical cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 33 (6), 882–889 (2023).

Randall, L. M., Mayadev, J. & Monk, B. J. Sequential chemotherapy for Early-Stage, Post-Radical hysterectomy cervical cancer: are the STARS aligned?. JAMA Oncol. 7 (3), 353–354 (2021).

Kruger-Genge, A. et al. Vascular endothelial cell biology: an update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20 (18) (2019).

Acknowledgements

We extend our gratitude to all the participants, recognizing that their contributions were instrumental to the success of this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zuhai Hu was involved in conceptualization, formal analysis, and drafting of the original manuscript. Chunrong Chen contributed to conceptualization, data curation, and validation. Yuliang Yuan and Qianjie Xu participated in validation, software development, and reviewing and editing the manuscript. Li Yuan were responsible for formal analysis and validation. Xiaodong Zheng and Haike Lei managed the project administration, supervision, and methodology and provided a critical review of the manuscript. All the authors have read and agreed to be personally accountable for the final content.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Chongqing University Cancer Hospital (CZLS2023343-A-2), and all procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution and with the Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, C., Hu, Z., Xu, Q. et al. Development and validation of machine learning models for assessing the risk of postoperative venous thromboembolism in cervical cancer patients. Sci Rep 15, 45561 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29761-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29761-1