Abstract

To investigate the advantages of microstructure in enhancing multiple performance characteristics of conveyor idler bearings and other friction pairs in open-pit coal mines, this study conducted computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations on NU205 cylindrical roller bearing. Based on the structural features of prototype bearings, we designed an elliptical-opening offset parabolic microstructure (hereinafter referred to as EOOPT) configuration for the inner raceway surface. Response surface analysis was employed to investigate the influence patterns of microstructure characteristic parameters on bearing performance. Through multi-objective optimization design, optimal microstructure parameters were determined. Comparative analysis with prototype bearings demonstrated that the optimized microstructure significantly improved average bearing pressure by 15.58% while reducing average friction coefficient by 16.33%, temperature by 9.28%, and wear volume by 6.37%. Experimental studies revealed the influence of microstructure column count on vibration suppression characteristics, temperature stability, and torque variation. This study innovatively designs an elliptical-opening offset parabolic microstructure (EOOPT) for cylindrical roller bearings in open-pit coal mines-filling the gap in existing research that lacks exploration of non-simple microstructure opening shapes, cross-sectional depth optimization, and their integrated impact on bearing thermal stability; meanwhile, it establishes a multi-objective optimization model for EOOPT parameters, realizing the synergistic improvement of bearing load capacity, friction reduction, and vibration suppression, which is rarely reported in studies on mine conveyor bearings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rolling bearings are critical components in major equipment such as aero-engines, high-speed trains, and CNC machine tool spindles. Their development level reflects a nation’s capabilities in advanced manufacturing1,2,3,4. Surface microstructures refer to arrays of micro-protrusions or depressions with specific geometries and arrangements. Research indicates that introducing these structures can significantly enhance structural integrity and functionality5,6,7,8,9,10. As key components in coal transportation, the performance of conveyor roller bearings directly impacts operational efficiency and reliability in open-pit coal mines. Consequently, exploring microstructure applications in bearings has become a research hotspot worldwide11,12,13,14,15,16,17, playing a vital role in improving bearing performance.

Josephine K et al.11 created strip-shaped microstructures on the raceways of tapered roller bearings and conducted simulation analysis and experimental studies on their performance. The research demonstrated that these microstructures could reduce frictional wear between raceway surfaces and rollers in tapered roller bearings. Xudong Z et al.12 selected cylindrical thrust roller bearings (CTRBs) as research subjects, using laser marking to create circular microstructures on the bearing raceway surfaces. Experimental results showed that these microstructures improved both friction reduction performance and dynamic characteristics of CTRBs. Long R et al.13 introduced five different depths of 250 µm diameter microstructure arrays on the inner ring of cylindrical roller thrust bearings via laser marking. Wear tests under oil-deficient lubrication conditions revealed that shallow pits enhanced lubrication duration, thereby improving tribological performance and vibration suppression. Wang Lin et al.14 established a 2mm side-length, 0.1mm depth three-dimensional square microstructure model at sliding bearing journals. Through CFD simulations, they investigated how microstructures affect lubrication performance under elastic deformation. Results indicated that microstructured bearings exhibited significantly reduced maximum oil film temperature, load capacity, and oil film pressure. Hua Xijun et al.15 used CFD methods to study the influence of microstructure density, bearing load, and rotational speed on oil film pressure in cylindrical roller bearings. Their findings revealed positive correlations between oil film pressure and load/rotational speed, but observed an initial increase followed by decrease with increasing microstructure density. Wang Yueyong17 employed laser marking technology to fabricate circular open microstructures on the inner raceway of radial tapered roller bearings and on the shaft surface of thrust cylindrical roller bearings. Through experimental studies, the research investigated how the diameter, depth, and surface density of these microstructures affect bearing friction wear, vibration, and noise, while analyzing the mechanisms through which microstructures enhance bearing performance. Current global research on microstructure applications in bearings predominantly focuses on how single or simple morphological combinations influence load capacity and friction/wear characteristics. However, studies addressing design details such as microstructure opening shapes, cross-sectional depth, thermal stability impacts, and optimization of microstructure parameters using multi-objective optimization theory remain relatively scarce.

Given the frequent roller bearing failures in open-pit mine conveying systems that severely impact conveyor efficiency and reliability, this study investigates the application of the NU205 cylindrical roller bearing. As a critical component, its performance directly determines service life and operational stability. Different from existing studies that mostly focus on single/simple microstructures (e.g., circular, rectangular) and only discuss load capacity or friction/wear independently, this research innovates in two aspects: first, it proposes the EOOPT with a special opening shape and offset cross-section, which is more suitable for the harsh working conditions of open-pit mine conveyors (high dust, variable load) and can better store lubricating oil and reduce localized stress; second, it constructs a response surface-based multi-objective optimization framework for EOOPT parameters, integrating the analysis of load, friction, temperature, and wear, and realizing the comprehensive improvement of bearing multi-performance indicators, providing a new technical path for the performance enhancement of mine conveyor idler bearings. These findings provide valuable references for maximizing microstructures’ advantages in improving multiple performance parameters across bearings and friction systems.

Selection and characteristic analysis of prototype bearing

Selection of prototype bearing

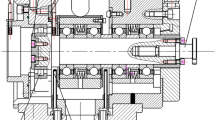

In this paper, NU205 cylindrical roller bearing is selected as the prototype. The main dimensions and operating parameters are shown in Fig. 1 and Table 1

Since this paper studies the superior performance of microstructured cylindrical roller bearings under full film lubrication, the lubrication state of the bearings is selected as the full film lubrication state of ISOVG68 lubricating oil.

The main performance parameters of ISOVG68 are shown in Table 2.

Modeling of friction pair properties of rolling bearings

Elastic hydrodynamic lubrication follows the following five basic equations:

-

(1)

Reynolds18 equation:

$$\frac{\partial }{\partial x}\left( {\frac{{\rho h^{3} }}{\eta }\frac{\partial p}{{\partial x}}} \right) + \frac{\partial }{\partial y}\left( {\frac{{\rho h^{3} }}{\eta }\frac{\partial p}{{\partial y}}} \right) = 12u_{{\text{e}}} \frac{\partial (\rho h)}{{\partial x}}$$(1)

In the form: h for oil film thickness, mm; p is the oil film pressure, Pa; ρ is the oil film density, kg/mm3; η is the viscosity of lubricating oil (Pa·S); ue is the rolling speed of the roller and the oil film on the inner circle, mm/s. Its value can be calculated according to formula(2) 15:

The boundary conditions are:

In this formula, xin、xout、yin、yout are the coordinates of the oil film in the contact area calculation domain, mm.

-

(2)

Film thickness equation.

When the roller and the inner raceway of the bearing are not deformed, the oil film thickness at the centerline of the two is h0. Then, when the roller and the inner raceway of the bearing are in contact, the oil film thickness at any point (x, y) in the contact area is expressed as:

In the formula, R = DwFw/(DW + FW) represents the equivalent curvature radius (mm); Ω denotes the micro-pit area; E′ = (1 − µ12)/E1 + (1 − µ22)/E2 indicates the equivalent elastic modulus. µ1、µ2, along with E1、E2, correspond to the Poisson’s ratio and elastic modulus of the bearing inner ring and roller materials respectively, with specific values detailed in Table 3. A, B, and D represent the open long axis, short axis, and depth of the microstructure respectively (see Fig. 8).

-

(3)

Energy equation19

$$\begin{aligned} & C_{p} \left( {\rho u\frac{\partial T}{{\partial x}} + \rho v\frac{\partial T}{{\partial y}} - \left( {\frac{\partial }{\partial z}\int_{0}^{z} {\rho u{\text{d}}z^{\prime} + } \frac{\partial }{\partial y}\int_{0}^{z} {\rho v{\text{d}}z^{\prime}} } \right) + \frac{\partial T}{{\partial z}}} \right) \\ & \quad = k\frac{{\partial^{2} T}}{{\partial z^{2} }} - \frac{T}{\rho }\frac{\partial \rho }{{\partial T}}\left( {u\frac{\partial \rho }{{\partial x}} + v\frac{\partial \rho }{{\partial y}}} \right) + \left[ {\left( {\frac{\partial u}{{\partial z}}} \right)^{2} + \left( {\frac{\partial v}{{\partial z}}} \right)^{2} } \right] \\ \end{aligned}$$(5)

In this formula, u、v are the velocity components of lubricating oil along x, y directions, m/s; Cp is the specific heat capacity at constant pressure J/(kg·K); k is the thermal conductivity; T is the actual temperature of oil film, K.

-

(4)

Viscosity-pressure equation20

$$\eta = \eta_{0} \exp \left\{ {\left( {\ln \eta_{0} + 9.67} \right)\left[ {\left( {1 + 5.1 \times 10^{ - 9} p} \right)^{0.68} \left( {\frac{T - 138}{{T_{0} - 138}}} \right)^{ - 1.1} - 1} \right]} \right\}$$(6)

In this formula,T0 is the ambient temperature, K.

-

(5)

Density-temperature–pressure equation15

$$\rho = \rho_{0} \left[ {1 + \frac{{0.6 \times 10^{ - 9} p}}{{1 + 1.7 \times 10^{ - 9} p}} - 6.5 \times 10^{ - 4} \left( {T - T_{0} } \right)} \right]$$(7)

According to the above basic equation, the mathematical models of oil film carrying capacity w and average temperature T1 can be derived as Formula (8) and (9) respectively:

In this formula, S is the oil film area, mm.

In this formula, kp is the pressure balance number, usually taken as 1.96 × 108N/m2.

According to the Ree-Eyring hyperbolic sinusoidal constitutive model20, the nonlinear viscous rheological state constitutive equation of lubricating oil in the bearing is:

In the formula, \(\tau_{{\text{e}}} = \sqrt {\tau_{{\text{x}}}^{2} + \tau_{{\text{y}}}^{2} }\); \(\tau_{{\text{x}}}\) and \(\tau_{{\text{y}}}\) are the shear forces of the oil film along the x and y directions, respectively, in Pa; \(\tau_{0}\) is the reference stress20, taken as \(\tau_{0} = 18 \times 10^{6}\) Pa. The friction force fx can be calculated by formula (12).

The friction force fx can be calculated by formula (12).

Therefore, the friction coefficient of the bearing is:

Friction performance simulation analysis of prototype rolling bearings

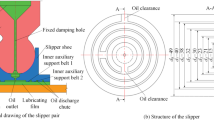

As can be seen from Fig. 1, there are actually three pairs of friction pairs in the cylindrical roller bearing. The first pair is the friction pair formed between the inner ring outer surface and the contact surface of the roller; the second pair is the friction pair formed between the outer ring raceway surface and the contact surface of the roller; the third pair is the friction pair formed between the cage and the contact surface of the roller.

This study focuses exclusively on micro-texturing of the first friction pair (hereafter referred to as “bearing friction pair”). The simplified 1/12th model of the NU205 bearing lubricant flow field is presented in Fig. 2. A 0.3mm lubricant film is maintained on the outer surfaces of rolling elements, inner ring, and outer ring’s inner surface as depicted in Fig. 3(a). The configuration defines rotating inner surfaces (inner), oil outlet (outlet), rotating outer surfaces (outer), symmetry planes (sym), roller rotation surfaces (gunzi), and periodic boundary conditions (side-a and side-b) as shown in Fig. 3(b). Structured quadrilateral elements are employed for oil film meshing, ensuring at least two layers of mesh in regions with minimal oil film thickness, as illustrated in Fig. 3(c).

In standard operation of NU205 cylindrical roller bearings, the outer ring remains stationary while the inner ring rotates. The rollers undergo combined rotational and orbital motions. However, significant displacement of the roller simulation nodes may compromise computational accuracy and potentially cause errors. To address this, our study simplifies the relative motion between the bearing rings and rollers by setting the outer ring to rotate counterclockwise around the bearing axis—mimicking the orbital motion of rollers. This simplified configuration requires only boundary conditions for roller rotation, significantly streamlining simulation setup.

According to the motion principle of cylindrical rolling bearings, when the speed of cylindrical roller bearing is n, the speed of roller na, the rotating speed of inner ring wall ni and the speed of outer ring ne can be calculated by formula (14), (15) and (16) respectively15

This paper sets n = 2000rad/min, so we get na = 807.2rad/min, ni = 2000rad/min, ne = 8373.3rad/min.

The bearing oil film pressure, shear stress and temperature distribution cloud obtained by simulation analysis according to the above process are shown in Fig. 4(a), (b) and (c):

According to the above cloud Figure and formula (8) ~ (13), the average bearing pressure, friction coefficient and temperature of the prototype bearing can be calculated as 20.7MPa, 0.09 and 33.21 °C respectively.

Simulation analysis of friction loss performance of prototype rolling bearings

To improve computational efficiency, a single roller unit from the bearing was selected for simulation analysis. After 3D modeling using SolidWorks software, the model was imported into Ansys Workbench’s transient structural simulation module. The patch conforming method was adopted with quad-sided cells for meshing. Grid size adjustments were performed separately on the inner ring and rollers of the cylindrical roller bearing: the inner ring cells were set to 0.5mm and roller cells to 0.3mm, resulting in a total of 28,856 mesh elements (as shown in Fig. 5). Since both the prototype bearing rings and rolling elements are made of high-carbon chromium bearing steel (Table 3), the simulation analysis can be conducted according to the material properties specified in Table 3

According to the computational model proposed by J F Archard for the volume of material removed during adhesive wear:

In the formula,V is Volume of material removed by adhesive wear, mm3;K is wear coefficient with dimension 1;N is normal load, Pa;L is Sliding distance, mm.

The radial load on the bearing is set to 1000N. The inner ring’s outer surface and rollers are in line contact. The inner ring’s outer surface is designated as the Contact Body, which defines the “moving” component in the contact pair that undergoes displacement or deformation during analysis21,22. The rollers are classified as Target Bodies, representing the “stationary” side of the contact interface that typically remains stationary or exhibits minimal movement. The contact mode is set to frictional contact, with boundary conditions configured for z-axis rotational connections between the inner ring and rollers (as shown in Fig. 6).

Through the analysis process, we can ultimately generate wear cloud diagrams of the prototype bearing at various time points. For instance, Fig. 7 shows the inner ring wear cloud diagram at 1/600s of operation. By accumulating wear amounts at each time point, we conclude that the total wear volume of the prototype bearing after 1/600s of operation is 4.3496 × 10−7mm3.

Micro-textured bearing design and performance simulation analysis

Preliminary design of the texture scheme

For the bearing friction pair studied in this paper, the micro-texturing can be applied either to the outer surface of the inner ring of the bearing or to the cylindrical surface of the cylindrical rollers. Considering that the former is more conducive to the storage of lubricating oil within the texture and is easier to process compared to the rollers, it is chosen to apply the texture to the outer surface of the inner ring of the bearing. As shown in Fig. 8, the micro-texturing cells are selected from the EOOPT23,24,25,26,27 used in the previous related research of the research group. The opening long axis is A, the short axis is B, the offset is C, and the depth is D. The distribution of the texture is as follows: a series of texture E rows are uniformly distributed circumferentially on the outer surface of the bearing outer ring, and in the axial direction, centered on the width centerline, texture F circles are arranged at equal intervals on both sides.

Analysis of the influence law of micro-texture parameters on bearing performance

In order to analyze the influence patterns of the characteristic parameters of micro-textures—A, B, C, D, E and F on the bearing’s load-bearing capacity, friction coefficient, temperature rise and wear amount, using the CCD central composite design method in Design Expert 10 software28,29,30, 39 sets of different parameter combinations of the texture parameters (the first 2 to 7 columns in Table 4 were constructed. Then, the bearing-related performance of these 39 sets of different parameter combinations of micro-textures was simulated and analyzed. Finally, the results are shown in the last 4 columns of Table 4

Based on the prototype bearing and micro-texture parameters, a three-dimensional solid model of the lubricating oil film between the outer surface of the inner ring of the 1/12 micro-textured bearing and the rollers was established. The remaining simulation analysis steps were basically the same as those for the prototype bearing, except that during meshing, the oil film mesh at the micro-textured area needed to be densified, as shown in Fig. 9.

According to the data in Table 4, the response surface of the interaction effects of the micro-texture parameters on the bearing-related performance can be analyzed using the Design Expert 10 software. Due to space limitations, only the average friction coefficient response surface is presented here, as shown in Fig. 10

From the response surface diagram, it can be analyzed that the influence degree of the six parameters of the micro-texture on the bearing’s bearing capacity, friction factor, temperature rise and wear amount are respectively E > B > A > C > D > F, E > B > F > A > D > C, F > A > E > B > C > D and F > A > C > E > D > B. Based on the data in Table 3, the quadratic regression equations for the influence of the six factors on the bearing’s bearing capacity, friction factor, temperature rise and wear amount are respectively formulas (17) to formula (20)

Optimization of micro-texture parameters

Optimize model construction

Set the 6 characteristic parameters of EOOPT as design variables, with the maximum average bearing pressure of the bearing being the largest, while the average friction coefficient, temperature, and wear amount being the smallest as multiple optimization objectives. Based on the following requirements, multiple constraints are set: On one hand, it is required that the average bearing pressure of the textured bearing be greater than that of the prototype bearing, and the friction coefficient, temperature rise, and wear amount of the textured bearing should be less than the corresponding values of the prototype; on the other hand, according to the structural characteristics, manufacturing feasibility, and existing research results of EOOPT, it is required that the sizes of the 6 characteristic parameters of EOOPT do not exceed a certain range. Thus, a multi-objective optimization mathematical model is established as:

The optimization module of Design Expert 10 was used to solve the formula (21), and the optimal parameters A, B, C, D, E, and F were determined to be 450 μm, 350 μm, 50 μm, 100 μm, 24 columns, and 10 rings respectively.

Simulation analysis of optimal microstructure bearing performance

The relevant performance of the EOOPT textured bearing with the optimal parameters was simulated and analyzed. Finally, the corresponding cloud diagram is shown in Fig. 11.

compared with the prototype bearing, the bearing pressure of the optimized parameter textured bearing increased by 15.58%, while the friction coefficient, average temperature and wear amount decreased by 16.33%, 9.28% and 6.37% respectively. In addition, the simulation analysis values of various performance indicators of the optimal textured bearing with the optimized texture parameters were within 3% of the predicted values of the established model (Formulas (17) to (20)). Thus, EOOPT can significantly improve the performance of the bearing; at the same time, it verifies that the established bearing performance prediction model has sufficient accuracy.

Experimental study on performance of micro-structure bearing

Preparation of microstructure bearing inner ring

Since the experimental research part of this study only investigates the influence laws of the number of texture rows E on the vibration characteristics, torque characteristics and temperature rise of the bearing, for this reason, the texture E of the bearing was set to 12, 24, 36, 48, and 60 rows respectively using a laser marking machine, while other parameters remained constant at A = 450 μm, B = 300 μm, C = 0 μm, D = 100 μm and F = 10 turns for five types of micro-textured inner rings, as shown in Fig. 12(a) to (e). The surface morphology of the micro-textures measured by the VHX-5000 ultra-depth microscope is shown in Fig. 13(g) and (h). That is, the size parameters of the micro-textures are A = 451 μm, B = 307 μm, C = 0 μm, and D = 108 μm, which meet the experimental requirements.

Construction of a bearing performance testing experimental platform

The bearing performance test experimental platform is shown in Fig. 14. It is composed of the BNQI mechanical transmission simulation test bench, equipped with vibration acceleration sensors, vibration signal processors, torque sensors, a computer (with built-in signal analysis software), and an AS887 four-channel thermocouple temperature sensor. Among them, the BNQI mechanical transmission simulation test bench mainly consists of the drive motor, support base, rotor unit, coupling, loading device, etc.31.

The main process, results and analysis of the test

The tested bearing was installed on the BNQI mechanical transmission simulation test bench. A radial load of 12 KN was applied to the tested bearing using a torque wrench. An acceleration sensor was attached above the bearing support housing. The signals picked up by the acceleration sensor and the torque sensor were sent to the computer through a data acquisition card. The four-channel thermocouple temperature sensors’ four probes were fixed on the upper, lower, left, and right positions of the bearing housing where the tested bearing was located using insulating tape. The operating speed of the bearing was set at 2000 rad/min. The experimental device was started, and the vibration acceleration signals and bearing torque of the bearing in a stable moving state for 20 s were tested. Each bearing operated for 1 h, and the average temperature measured by the 4 probes of the thermocouples was taken as the final temperature test result.

Through the above experimental steps, the time-domain signals of the vibration acceleration of the prototype bearing and the 12-column, 24-column, 36-column, 48-column, and 60-column micro-textured bearings were obtained. These signals were integrated twice with respect to time to obtain the vibration displacement–time curves as shown in Fig. 14.

From Fig. 14, the amplitudes of the vibrations of the prototype and the 5 types of textured bearings can be obtained. The amplitude reduction percentages of each textured bearing compared to the prototype bearing are shown in Fig. 15. From this figure, it can be seen that compared to the non-textured bearing, the amplitudes of any column number micro-textured bearings have significantly decreased. Among them, the 60-column micro-textured bearing has the smallest amplitude displacement reduction, with a reduction of 15.4%, while the 24-column micro-textured bearing has the largest amplitude displacement reduction, reaching 31.9%. This proves the superiority of micro-texturing in improving the vibration resistance of bearings.

Through the experimental procedures, the average operating temperatures of fabric-structured bearings with E = 0, 12, 24, 36, 48, and 60 were measured as 27.7 °C, 25.2 °C, 24.7 °C, 26.5 °C, 26.2 °C, and 25.0 °C respectively, with corresponding average torques of 0.651N·m, 0.637N·m, 0.613N·m, 0.625N·m, 0.642N·m, 0.636N·m. For comparative analysis, we first calculated the friction coefficients and average temperatures of six bearing types in the experimental control group using formulas (18) and (19) from the previously established prediction models. These predicted values were then plotted alongside the experimentally measured torque and temperature data in Fig. 16. Since bearing torque should exhibit a positive correlation with friction coefficient, the variation pattern of measured torque with fabric column count indirectly reflects the trend of friction coefficient changes with fabric column count.

As shown in Fig. 16 the experimental studies and simulation analyses demonstrate consistent trends in bearing average temperature and friction coefficient with the number of microstructure columns. Both parameters first decrease, then increase, and subsequently decrease again as the number of columns increases. Among the five types of microstructured bearings examined, the 24-column configuration exhibits the lowest temperatures and friction coefficients. This validation confirms the accuracy of the performance simulation methodology developed for cylindrical roller bearings and the conclusions derived from it.

Conclusion

(1) Through response surface analysis, this study investigated the variation patterns of multiple bearing performance characteristics (load capacity, anti-friction wear resistance, and temperature rise) with EOOPT characteristic parameters. The influence order on average bearing pressure, friction coefficient, temperature, and wear rate was determined as: E > B > A > C > D > F、E > B > F > A > D > C、F > A > E > B > C > D、F > A > C > E > D > B. Additionally, a high-precision predictive model based on texture parameters was established for bearing performance. (2) Multi-objective optimization design identified optimal micro-texture parameters as A = 450 μm, B = 350 μm, C = 50 μm, D = 100 μm, E = 24, and F = 10. Compared to non-textured bearings, these parameters resulted in a 15.58% increase in average bearing pressure, while reducing friction coefficient by 16.33%, temperature by 9.28%, and wear rate by 6.37%. (3) Experimental results demonstrated significant improvements in vibration resistance, anti-friction performance, and thermal stability of multi-row textured bearings over non-textured counterparts. Consistency between experimental observations and simulation analyses regarding temperature variations and reduced friction (indirectly measured through torque data) across different textured configurations validated the validity of our cylindrical roller bearing simulation methodology and conclusions.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request will be made available on request.

References

Zhiyuan, H. E. et al. Crack initiation and evolution model of rolling bearings considering fluid lubrication. J. Mech. Eng. 60(23), 164–176 (2024) (in Chinese).

Yu, W. et al. A tapered rolling bearing based on tribovoltaic effect for active rotational speed sensing. Nano Energy 134, 110607 (2025).

Yongjian, Y. U. et al. The influence of roller geometric errors on the rotational accuracy of cylindrical roller bearings. J. Northwest. Polytech. Univ. 37(04), 774–784 (2019) (in Chinese).

Gouda, B. et al. Effects of positioning of inner race micro-textures on the tribodynamic performances of radial ball bearings. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 223, 111908 (2025).

CHEN, Y. et al. Lubrication characteristics of gear end friction pair for aviation high speed gear pump. China Mech. Eng. 35(07), 1178–1187 (2024).

ZHANG, Y. et al. Analysis of the bearing capacity of asymmetric surface micro-textured sliders under the coupling effect of cavitation and inertial forces. J. Northwest. Polytech. Univ. 35(06), 1026–1032 (2017).

Arif, M. et al. Investigating linear and non-linear dynamic characteristics of textured journal bearings with slip boundary condition and pseudoplastic lubricants: a numerical study. Phys. Scr. 99(9), 095246 (2024).

Zhenhua, D. O. U. et al. Study on friction and wear characteristics of groove texture of disc friction pair. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 58(11), 200–209 (2022) (in Chinese).

Wang, Y. et al. A biomimetic micro-texture based on shark surface for tool wear reduction and wettability change. J. Manuf. Process. 129, 202–214 (2024).

Kumar, A. S. et al. Performance of hybrid thrust bearing textured surface operating with electro-rheological lubricant. Proc. Institution Mech. Eng. Part J J. Eng. Tribol. 237(04), 911–925 (2023).

Josephine, K., Gerhard, P. & Florian, P. Investigation of the possible applications for microtextured rolling bearings. Front. Manuf. Technol. 2, 1012343 (2022).

XU dong, Z. & Yimin, Z. Tribological and dynamic performance analysis of rolling bearings with varied surface texture operating under lubricant contamination. Wear 532–533, 205109 (2023).

Long, R. et al. Influence of micro-texture radial depth variations on the tribological and vibration characteristics of rolling bearings under starved lubrication. Tribol. Int. 194, 109545 (2024).

WANG, L., ZHANG, Y. & CEN, G. Thermal elastohydrodynamic lubrication analysis of high-speed high specific pressure textured sliding bearings. J. Northwest. Polytech. Univ. 37(04), 751–756 (2019).

HUA, X. et al. Numerical analysis of surface lubrication performance of laser micro-textured rolling bearing. Surf. Technol. 47(03), 36–41 (2018).

Hongwei, Q. I. Research on Dynamic Characteristics of Cylindrical Roller Bearing with Surface Texture[D] (Taiyuan University of Technology, 2022).

Yueyong, W. A. N. G. Research on Friction Wear and Contact Fatigue Reliability of Surface Textured Rolling Bearings [D] (Shenyang University of Technology, 2023).

Winkler, A. et al. Numerical modeling of wear in a thrust roller bearing under mixed elastohydrodynamic lubrication. Lubricants 8(05), 58–58 (2020).

Liu, X. & Yang, P. Analysis of the thermal elastohydrodynamic lubrication of a finite line contact. Tribol. Int. 35(03), 137–144 (2002).

Kim, H. J. et al. Thermal elastohydrodynamic analysis of circular contacts, Part 2: Non-Newtonian model. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J. Eng. Tribol. 215(04), 353–362 (2001).

Bhat, A. J. et al. Performance enhancement of hydrodynamic thrust bearings: Investigating cooling strategies, deep recesses, and textured surfaces. Tribol. Int. 211, 110877 (2025).

Jiang, S. et al. A soft self-adaptive surface texturing to improve dynamic stability of bearing sliders under speed varying conditions. Tribol. Int. 212, 110976 (2025).

Yinghua, Y. U. et al. Analysis and optimization of special micro-texture multi-oil-wedge sliding bearings characteristics. J. Northwest. Polytech. Univ. 41(01), 222–229 (2023) (in Chinese).

Yinghua, Y. U. et al. Multi-objective optimization design of micro-texture of machine tool sliding guide. Aeronautical Manuf. Technol. 65(06), 36–44 (2022).

Yinghua, Y. U. et al. Optimization of Micro-texture Parameters of Tool Surface Elliptic Opening Offset Parabola[J]. J. Ordnance Equip. Eng. 44(02), 225–233 (2023) (in Chinese).

Ping, X. U. et al. Research on performance and optimal design of textured disc friction pairs. China Mech. Eng. 35(10), 1774–1782 (2024).

Yinghua, Y. U. et al. Research on parabolic microtexture of elliptical opening of engine cylinder hole. Lubr. Seal. 48(07), 100–106 (2023) (in Chinese).

Le, Z. H. O. U. Analysis of Characteristics and Optimization of Textural Parameters for Radial Sliding Bearings with Three Oil Wedges and Special Micro-Textured Structures (Liaoning Technical University, 2023).

Xu, P. et al. Optimization design and performance analysis of micro-textured sliding shoe pair in axial piston pump. J. Ordnance Equip. Eng. 46(06), 27–37 (2025).

Yu, Y., Guo, W., Shen J., et al. Optimization Design and Performance Analysis of Special Micro-texture for Thrust Roller Bearings. Mech. Sci. Technol. 1–12. (2025).

Qiulin, N. et al. Research progress on the synergistic technology of tool surface micro-texturing and micro-lubrication. China Mechanical Engineering. 135, 1–24 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Letpub for the English language editing.

Funding

This work were supported by “Tianchi Talent” Introduction Plan、Postdoctoral Program: 410713 and Natural Science Foundation of Xinjiang Autonomous Region 2024D01A101.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zhiyong Yang: Writing—original draft, Methodology, Investigation,Conceptualization. Zhiqun Wang: Writing—review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization. Qiqi Li:Validation, Methodology. Guilin Hu: Writing—review & edit-ing, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization. Jinnan Lu: Writing—review & editing,Validation, Supervision, Conceptualization. Fucheng Yang: Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization. Hongyu Zhang: Writingreview & editing, Validation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Z., Wang, Z., Li, Q. et al. Study on surface microstructure of cylindrical roller bearings for open-pit coal mine conveyors. Sci Rep 16, 407 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29792-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29792-8