Abstract

This study systematically evaluated the effects of three typical desert restoration models in the Hobq Desert—the integrated photovoltaic-agriculture model (PV-Ag), the artificial shrub aerial seeding model (ASS), and the bare sand with photovoltaic panels model (BS-PV)—on soil physicochemical properties, microbial characteristics, and vegetation recovery. The results indicated that the PV-Ag model performed most prominently in improving soil structure, increasing nutrient content, and enhancing microbial activity. The fine particle content in the soil reached 92.9%, while organic matter and total nitrogen content increased by 388.9–544.4% and 476.7–551.8%, respectively, compared to those in shifting sand dune (LS). Under PV-Ag model, the total soil microbial count increased more than 10 times, and microbial biomass carbon and nitrogen rose by 10.8–13.9 times and 13.4–17.1 times, respectively. The shade provided by photovoltaic panels in the PV-Ag model effectively optimized the soil hydrothermal environment, with humidity (0.043 m3/m3) and temperature (11.75 °C) being significantly better than those under the ASS and LS models, thereby promoting root biomass (1.8 g/kg) and the accumulation of available nitrogen and potassium (average increases of 188.7% and 258.5%). Correlation analysis revealed that species richness was significantly positively correlated with soil organic matter, total nitrogen, and microbial biomass carbon (r ≥ 0.96), and significantly negatively correlated with pH (r = − 0.95). Root biomass showed stronger correlations with total phosphorus, available phosphorus, and fungal abundance (r ≥ 0.80), indicating differentiated driving mechanisms of soil nutrients and microbial communities on vegetation restoration. The comprehensive soil quality index (SQI) evaluation demonstrated that the SQI value under the PV-Ag model was 810–1185 times higher than that of LS, significantly exceeding the values under the ASS (2.5–3.9 times) and BS-PV (11.3 times) models. The study demonstrates that the integrated photovoltaic-agriculture model can significantly improve desert soil quality and ecological function, offering an effective pathway for synergizing ecological restoration and renewable energy development in arid regions of the Hobq Desert.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Desertification can trigger severe environmental issues, including the destruction of biological habitats, loss of biodiversity, accelerated depletion of carbon stocks exacerbating global warming, and water scarcity1,2,3. Currently, desertification is one of the most critical and widespread environmental challenges worldwide4. Desertified land covers 24.1% of the Earth’s land surface5, with over 2 billion people across more than 100 countries residing in arid and semi-arid regions highly prone to desertification6. China faces significant desertification problems7. According to the Sixth National Survey on Desertification and Sandification, by 2019, the area of desertified land in China reached 2.5737 million km2, accounting for 26.81% of the country’s total land area, while sandy land covered 1.6878 million km2, representing 17.58% of the national territory8. Annual direct economic losses due to desertification are approximately 54 billion CNY9. Furthermore, against the backdrop of climate change, the severity of global drought is expected to intensify10, making desertification a critical long-term issue that humanity must confront and address.

In response to the threat of desertification, countries are adopting comprehensive measures. Remote sensing, digital mapping, and machine learning technologies are widely used in monitoring efforts. For instance, Kazakhstan developed a new technical framework revealing that 76.1% of its land is moderately to highly sensitive to desertification, with about 104,000 km2 accurately identified as desertified areas, laying a foundation for targeted management11. China extensively employs satellite remote sensing combined with field measurements for dynamic monitoring4,12,13. In terms of management practices, sustainable land and water resource management are key. Examples include strict water usage quotas in Northwestern China and sustainable farming and grazing practices in Northeastern regions9. Studies in the Mediterranean have shown that improved soil and land management practices have a moderate and growing impact14. In ecological restoration, biocementation and crusting technologies are promoted globally for soil stabilization. Initiatives such as shelterbelt construction in China, reforestation in Iraq, and oasis recovery are common practices. It is estimated that such ecological restoration efforts could create approximately 10 million green jobs in developing countries15,16. At the policy and socioeconomic levels, comparative studies within the “Belt and Road” framework highlight the foundational role of sound policies and management systems. Capacity building, education, and training covering communities and decision-makers, integrated with traditional and modern knowledge, form a systematic solution to curb desertification and promote green development17.

As a key area in China’s desert control efforts, the Hobq Desert holds strategic importance as a stronghold of the “Three-North” Shelterbelt Program, a dust source affecting the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region, and the sand source area of the Yellow River’s Great Bend. After decades of comprehensive management, 6000 km2 have been restored and 3200 km2 greened, earning its designation as a “Global Model of Desert Eco-Economy” by the United Nations18. In recent years, driven by China’s national “Dual Carbon” goals (peak carbon emissions and carbon neutrality)—aimed at promoting a comprehensive green transition in economy and society, building a new power system dominated by renewable energy, and enhancing ecosystem carbon sink capacity—the Hangjin Banner region of the Hobq Desert has innovatively developed an integrated “photovoltaic-agriculture” model. This approach synergizes desert control, power generation, and agriculture. Compared with traditional single-method plant-based sand fixation, the integrated photovoltaic-agriculture model not only reduces water evaporation through panel shading and improves microclimatic conditions but also supplies clean energy for agricultural planting, enhancing land use efficiency and economic returns. However, photovoltaic facilities may also cause potential ecological disturbances, such as uneven shading and increased soil disturbance. The comprehensive impact mechanisms of these facilities on the structure and function of soil ecosystems remain unclear. Although research in the Hobq Desert has extensively covered the physio-ecology of xerophytes19,20, eco-hydrological benefits21,22, and the regulatory mechanisms of traditional “plant-based sand fixation” models (artificial shrub plantations) on soil physicochemical properties and microbial communities21,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30—where root activities drive positive “soil-vegetation” feedback loops considered core to ecological restoration—significant gaps remain in understanding how the emerging “photovoltaic-agriculture” model systematically influences soil ecological functions. Particularly lacking are quantitative comparisons with traditional sand fixation methods and in-depth analyses of microbial community response mechanisms.

Therefore, this study aims to systematically clarify the impact mechanisms of the photovoltaic-agriculture model on the soil ecosystem and quantitatively evaluate its innovation and ecological benefits compared to traditional sand fixation models. The specific research objectives include: (1) revealing differences in soil physicochemical properties and microbial activity among the integrated photovoltaic-agriculture model (PV-Ag), the artificial shrub aerial seeding model (ASS), the bare sand with photovoltaic panels model (BS-PV), and shifting sand dune (LS) as a control; (2) constructing a soil quality index (SQI) system to quantitatively evaluate the soil improvement effects of different models; (3) analyzing the shaping effects of the integrated photovoltaic-agriculture model on soil microbial community diversity and the structure of functional microbial groups. Through this research, we aim not only to fill the knowledge gap regarding soil ecological responses under the context of “photovoltaic-agriculture synergistic” desert control but also to provide a theoretical basis and practical support for optimizing photovoltaic desert control technology systems and promoting the integrated development of ecology, energy, and agriculture in desertification-prone regions.

Data and methods

Study area

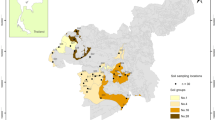

This study was officially launched in July 2023, aiming to systematically evaluate the impact of different desertification control models on soil quality. The study area is situated within the 200 MWp photovoltaic power station in the Hobq Desert, Duguitala Town Industrial Park, Hangjin Banner, Ordos City, Inner Mongolia (Fig. 1). It spans geographical coordinates from 37° 20ʹ N to 39° 50ʹ N and 107° 10ʹ E to 111° 45ʹ E. This region experiences a temperate continental monsoon climate, with an annual average temperature ranging from 6.2 to 8.7 °C and an effective accumulated temperature (≥ 10 °C) of 3197 °C. The annual average sunshine duration is 3138.7 h31. Characterized by arid conditions and frequent winds, the dominant wind directions are southwest (31.9%) and northwest (34.9%). The annual average wind speed is 3.3 m/s, reaching maximum speeds of 28.7 m/s, often accompanied by sandstorms. The annual average precipitation is 420 mm, primarily concentrated between June and September, while the annual average evaporation is 2560 mm. Wind and sand activities mainly occur from March to May32, with annual strong wind days ranging from 25 to 35. Influenced by long-term human activities, the natural vegetation in the experimental area has developed into various community types, including natural shrublands, artificial shrublands, and artificial grasslands. The dominant species are wind-erosion and drought-tolerant plants, such as Artemisia ordosica, Hedysarum mongolicum, Salix psammophila, and Artemisia sphaerocephala31.

Site selection

The experimental area was divided into three main desertification control models based on land surface types: the integrated photovoltaic-agriculture model (PV-Ag), the artificial shrub aerial seeding model (ASS), the bare sand with photovoltaic panels model (BS-PV), as shown in Fig. 1. Representative sample plots were established within each model: the PV-Ag area included a natural restoration community of Artemisia ordosica (PV-Ag (AO)), artificially planted potato (PV-Ag (Po)), and watermelon (PV-Ag (Wm)); the ASS area contained an artificially aerial-seeded Hedysarum mongolicum shrubland (ASS (HM)) and a Salix psammophila shrubland (ASS (SP)); and the BS-PV area consisted of a bare sand site with photovoltaic panels (BS-PV (BS)). Shifting sand dune (LS) was set up as a control plot, characterized by very low vegetation coverage (approximately 5%) with Agriophyllum squarrosum as the dominant species. The soil in this area has long been affected by wind erosion, maintaining a natural desertified state with minimal human disturbance. No large-scale agricultural, forestry, or ecological restoration projects have been implemented historically in this region, making it representative of the baseline desertification conditions. Essential information for each sample plot, including altitude, dominant species, species richness, and root biomass, is detailed in Table 1. The layout of the experimental area ensured consistent topography and comparability of environmental factors across all plots, guaranteeing that conditions were essentially identical except for the treatment methods, thereby enhancing the reliability of the experimental results.

Soil sample collection

In July 2023, researchers collected soil samples from three 1 m × 1 m plots established for each of the seven vegetation restoration types (PV-Ag (AO), PV-Ag (Po), PV-Ag (Wm), ASS (HM), ASS (SP), BS-PV (BS), and (LS)). They conducted sampling at the center of each plot across three depths: 0–10 cm, 10–20 cm, and 20–30 cm, with three replicates at each depth. Each replicate yielded approximately 1 kg of soil, which was then air-dried, cleaned, and sieved. The analysis included determining the soil organic matter (SOM), pH, total nitrogen (TN), total phosphorus (TP), available nitrogen (AN), available phosphorus (AP), and available potassium contents, as well as soil microbial biomass carbon (MBC), nitrogen, and quantity. Additionally, sediment particle size measurements for each plot at the three depths were performed using a Mastersizer 2000 laser particle size analyzer.

Root biomass and species richness measurement

In July 2023, a 20 × 20 m quadrat was established within each standard sample plot (Fig. 2). All shrub and herbaceous communities, including underground roots, were cut off at ground level and cleared of debris. The aboveground and belowground parts were mixed together and weighed to determine the fresh weight. A subsample representing 1/3 to 1/2 of the total material was collected, sealed in bags, and transported to the laboratory.

The samples were oven-dried at 85 °C until constant weight was achieved, and then weighed to the nearest 0.1 g. Moisture content was calculated based on the fresh and dry weights of each plant organ, allowing estimation of organ-specific biomass. The total biomass per plant was obtained by summing the biomass of all individual organs.

Meteorological observation

To investigate the influence of different desertification control models on the soil environment, 10-m meteorological towers were installed in March 2023 in the integrated photovoltaic-agriculture (PV-Ag) area, the artificial shrub aerial seeding (ASS) area, and the shifting sand dune (LS) area for comparative observation (Fig. 3). Each tower was equipped with anemometers, wind vanes, and air temperature and humidity sensors at heights of 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 4.0, and 10.0 m. In addition, soil temperature probes were buried at depths of 0, 5, 10, and 20 cm, and soil moisture sensors were installed at 5, 10, and 20 cm depths to analyze the potential effects of underlying surfaces on soil microbial activity and nutrient cycling. Data were automatically recorded using a CR1000 data logger at intervals of 1 min, 30 min, and 1 h. Hourly data were used for analysis in this study.

Determination methods

-

(1)

Soil physical and chemical property determination.

Soil organic matter was determined using the potassium dichromate external heating method. Here, pH values were measured using the 1:2.5 soil-to-water ratio extraction method with a pH meter. Available nitrogen was determined using the alkaline hydrolysis distillation method. Available phosphorus was measured using the Olsen method. Available potassium was determined using the ammonium acetate extraction-flame photometry method.

-

(2)

Soil Microbial Determination.

Soil microbial quantities were determined using the dilution plating method. We cultured bacteria number on beef extract peptone agar medium, actinomycetes number on Gause’s No. 1 agar medium, and fungi number on Martin’s medium. We sterilized the media at 121 °C for 20 min. We selected two dilution levels and incubated the cultures at 25–28 °C. We counted bacteria, fungi, and actinomycetes within 2–7 days.

-

(3)

The soil microbial biomass carbon was determined using the fumigation method, and the soil microbial biomass nitrogen was measured using the Kjeldahl method.

Soil quality evaluation method

To comprehensively evaluate soil quality, this study innovatively integrates Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and the Comprehensive Soil Quality Index (SQI) method. PCA used to analyze the correlation between soil microorganisms and soil physicochemical properties, applying the eigenvalue contribution rates of each index as weights to calculate the soil physicochemical and microbial index values across seven different vegetation restoration types under three desertification control models. The comprehensive soil index method was then employed to assess the overall health status of the soil.

-

(1)

Owing to the varying dimensions and significant differences in absolute values and ranges among the evaluation indices, which can differ by several orders of magnitude, we standardized the original data before applying PCA to ensure accurate calculation results. The standardization formula for each evaluation index is given as follows:

$$\text{Q}\left({X}_{i}\right)=\left({X}_{ij}-{X}_{i{\text{min}}}\right)/\left({X}_{i{\text{max}}}-{X}_{i{\text{min}}}\right)$$(1)where \(\text{Q}\left({X}_{i}\right)\) represents the membership value of each factor, \({X}_{ij}\) is the value of each factor, and \({X}_{i{\text{max}}}\) and \({X}_{i{\text{min}}}\) are the maximum and minimum values, respectively, of factor i.

-

(2)

Because the importance of each SQI varies, weight coefficients are commonly used to represent the significance of each index. In this study, we use SPSS software to calculate the factor loadings of the principal components, which determines the significance of each factor in soil quality. The formula is

$${W}_{i}={C}_{i} \bigg/\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left({C}_{i}\right)$$(2)where \({W}_{i}\) is the weight of each soil index, and \({C}_{i}\) is the factor loading of soil index i.

-

(3)

The formula for calculating the SQI is

$${\text{SQI}} = \sum\limits_{i}^{{\text{m}}} {{\text{K}}_{i} \left[ {\sum\limits_{{i = 1}}^{{\text{n}}} {{\text{W}}_{i} \times {\text{Q}}({\text{x}}_{i} )} } \right]}$$(3)where n is the number of evaluation indices, taken as 13; m is the number of selected principal components, taken as 2; and \({K}_{i}\) is the variance contribution rate of principal component i.

Data analysis

Prior to performing correlation analysis and principal component analysis using SPSS 18.0, all variables passed the Shapiro–Wilk test for normality (p > 0.05) and Levene’s test for homogeneity of variances (p > 0.05), thereby satisfying the fundamental assumptions of parametric tests and ensuring the validity of subsequent statistical inferences. Figures were generated using SigmaPlot and Origin 2024 software.

Results and analysis

Soil mechanical composition and nutrient element characteristics of typical vegetation communities under different desertification control models

The surface sediments of typical vegetation communities under the three desertification control models in the study area predominantly consist of fine sand (Fig. 4). The vegetation communities PV-Ag (AO), PV-Ag (Po), and PV-Ag (Wm) show the highest content of fine particles, with fine sand, very fine sand, and silt making up 92.9%. The vegetation communities ASS (HM) and ASS (SP) contain a moderate level of fine particles, comprising 78.8% of fine sand, very fine sand, and silt. The vegetation communities BS-PV (BS) and shifting sand dune (LS) have the lowest content of fine particles, accounting for 65.6%. Overall, the vegetation communities under the integrated photovoltaic-agriculture model (PV-Ag) have the highest content of fine particles. This is followed by the artificial shrub aerial seeding model (ASS), and the bare sand with photovoltaic panels model (BS-PV), which has the least fine particles. These findings align with the results of Dang et al.33 and Yan et al.32 in their studies on the Hobq Desert. The soil organic matter content in the 0–30 cm soil layer of the typical vegetation communities is highest in PV-Ag (AO), PV-Ag (Po), and PV-Ag (Wm), showing increases of 544.4%, 411.1%, and 388.9%, respectively, compared to the shifting sand dune (LS). The soil organic matter content in ASS (HM) and ASS (SP) is moderate, showing increases of 211.1% and 188.9%, respectively. The soil organic matter content in BS-PV (BS) is the lowest, showing an increase of 80.0%. Additionally, the nutrient content in the soil surface layer (0–10 cm) exhibits a surface aggregation effect, which gradually decreases with increasing soil layer depth. Overall, the integrated photovoltaic-agriculture model (PV-Ag) has the highest soil organic matter content, followed by the artificial shrub aerial seeding model (ASS), and the bare sand with photovoltaic panels model (BS-PV) has the lowest content, in the following order: PV-Ag (AO) > PV-Ag (Po) > PV-Ag (Wm) > ASS (HM) > ASS (SP) > BS-PV (BS) > LS.

The above analysis shows that finer soil particles are associated with higher organic matter content, primarily because the larger specific surface area of these particles can adsorb more nutrient elements. Moreover, the smaller pores between fine particles help retain nutrients and reduce nutrient loss. In addition, microbial activity occurs more frequently in soils with fine particles, which facilitates the transformation and release of nutrients, thereby enhancing the soil’s nutrient content.

Figure 5 shows the distribution of soil chemical properties in vegetation communities under three different desertification control models. The pH values in the 0–30 cm soil layer across various vegetation communities are generally weakly alkaline or alkaline and tend to increase with soil layer depth. Compared with the mobile sand dune, the pH values in PV-Ag (AO), PV-Ag (Po), and PV-Ag (Wm) decrease by 11.6%, 8.6%, and 7.9%, respectively, averaging a reduction of 9.3%. The pH values in ASS (HM) and ASS (SP) decrease by 4.7% and 5.6%, respectively, with an average reduction of 5.2%. The pH value in BS-PV (BS) decreases by 2.0%. Overall, the soil pH under the integrated photovoltaic-agriculture model (PV-Ag) tends to be neutral or slightly alkaline, which is favorable for vegetation growth. In contrast, the soil pH under the artificial shrub aerial seeding model (ASS) and the bare sand with photovoltaic panels model (BS-PV) shows alkalinity or strong alkalinity, which is unfavorable for plant growth.

In terms of available nutrients, the soil in the 0–30 cm layer of various vegetation communities under three sand control models shows varying degrees of increase in available nitrogen and potassium content compared to the shifting sand dune (LS). Specifically, the increases in available nitrogen and potassium in PV-Ag (AO), PV-Ag (Po), and PV-Ag (Wm) are 248.3% and 334.3%, 150.8% and 217.5%, and 166.9% and 223.7%, respectively, with an average increase of 188.7% and 258.5%. In ASS (HM) and ASS (SP), the increases are 107.6% and 64.4%, and 102.5% and 47.6%, respectively, with an average increase of 105.1% and 56.0%. The increase in BS-PV (BS) is 4.2% and 23.9%. Thus, the integrated photovoltaic-agriculture model (PV-Ag) exhibits significantly higher soil available nitrogen and potassium content compared to the artificial shrub aerial seeding model (ASS) and the bare sand with photovoltaic panels model (BS-PV).

In contrast, the soil available phosphorus content in the 0–30 cm soil layer shows a significant increase in the areas with the artificial shrub aerial seeding model (ASS), with increases of 388.2% in ASS (HM) and 329.0% in ASS (SP). Similarly, in the integrated photovoltaic-agriculture model (PV-Ag), the increases are 270.9% in PV-Ag (AO), 306.1% in PV-Ag (Po), and 284.9% in PV-Ag (Wm). Overall, the artificial shrub aerial seeding model (ASS) exhibits a notably higher soil available phosphorus content compared to both the integrated photovoltaic-agriculture model (PV-Ag) and the bare sand with photovoltaic panels model (BS-PV). The ranking of soil phosphorus content from highest to lowest is as follows: ASS (HM) > ASS (SP) > PV-Ag (Po) > PV-Ag (Wm) > PV-Ag (AO) > BS-PV (BS) > LS.

Figure 6 shows the distribution of total soil nutrient content across vegetation communities under three different desertification control models in the study area. When compared with shifting sand dune (LS), the total nitrogen content in the 0–30 cm soil layer is significantly higher under the integrated photovoltaic-agriculture model (PV-Ag) than under the artificial shrub aerial seeding model (ASS) and the bare sand with photovoltaic panels model (BS-PV). The nitrogen content follows this order: PV-Ag (AO) (551.8%) > PV-Ag (Wm) (517.8%) > PV-Ag (Po) (476.7%) > ASS (HM) (330.4%) > ASS (SP) (300.0%) > BS-PV (BS) (100.0%) > LS.

Conversely, the total phosphorus and available phosphorus contents in the same soil layer are significantly higher under the artificial shrub aerial seeding model (ASS) than under the integrated photovoltaic-agriculture model (PV-Ag) and the bare sand with photovoltaic panels model (BS-PV). The phosphorus content follows this order: ASS (HM) (325.9%) > ASS (SP) (301.7%) > PV-Ag (Po) (289.6%) > PV-Ag (AO) (244.8%) > PV-Ag (Wm) (243.1%) > BS-PV (BS) (94.8%) > LS.

Analysis of soil microbial properties in typical vegetation communities under different desertification control models

Analysis of soil microbial quantity

The distribution of microorganisms in soil not only reflects the transformation and cycling of soil materials and energy, but also indicates soil fertility status. As shown in Fig. 7, compared with mobile sand dunes, the total number of soil microorganisms in the 0–30 cm soil layer of vegetation communities under three sand control models shows a significant increase. Overall, the order of increase is as follows: PV-Ag (AO) (10.6 times) > PV-Ag (Wm) (10.2 times) > PV-Ag (Po) (10.0 times) > ASS (HM) (7.8 times) > ASS (SP) (6.5 times) > BS-PV (BS) (3.7 times) > LS. Regarding the distribution of the three major groups of soil microorganisms, compared with mobile sand dunes, the numbers of soil bacteria, fungi, and actinomycetes in vegetation communities under the three sand control models in the study area all show significant increases. The number of soil bacteria under the integrated photovoltaic-agriculture model (PV-Ag) is significantly higher than that under the artificial shrub aerial seeding model (ASS) and the bare sand with photovoltaic panels model (BS-PV). However, the numbers of soil fungi and actinomycetes show an opposite trend, with the artificial shrub aerial seeding model (ASS) being significantly higher than the integrated photovoltaic-agriculture model (PV-Ag) and the bare sand with photovoltaic panels model (BS-PV).

Analysis of soil microbial biomass

Figure 8 shows the distribution of soil microbial biomass carbon and nitrogen across various vegetation communities under three different sand control models in the study area. When compared to the mobile sand dunes, the soil microbial biomass carbon in the communities PV-Ag (AO), PV-Ag (Po), PV-Ag (Wm), ASS (HM), ASS (SP), and BS-PV (BS) shows an increase by factors of 13.9, 10.8, 11.3, 9.3, 7.0, and 1.2, respectively. Similarly, the nitrogen contents in these communities increase by 17.1, 13.4, 15.8, 12.0, 13.1, and 5.0 times, respectively. Overall, the data show that the integrated photovoltaic-agriculture model (PV-Ag) exhibits significantly higher soil microbial biomass carbon and nitrogen than both the artificial shrub aerial seeding model (ASS) and the bare sand with photovoltaic panels model (BS-PV).

Differential driving mechanisms of soil nutrients and microbial characteristics on species richness and root biomass in Sand-Fixing Vegetation

Figure 9 shows the correlations between soil physicochemical properties, microbial characteristics, and plant-related variables (species richness and root biomass) under different desertification modes. Based on the correlation coefficient matrix, we found that species richness was significantly positively correlated (p ≤ 0.001) with most soil nutrient and microbial indicators. For example, it showed strong positive correlations with soil organic matter (SOM, r = 0.96), total nitrogen (TN, r = 0.98), available nitrogen (AN, r = 0.97), microbial biomass carbon (MBC, r = 0.98), and microbial biomass nitrogen (MBN, r = 0.96), indicating that soil fertility and microbial activity play an important role in promoting plant diversity. In contrast, species richness was significantly negatively correlated with pH (r = -0.95), suggesting that alkaline soils may limit species diversity. Biomass was strongly correlated with total phosphorus (TP, r = 0.82), available phosphorus (AP, r = 0.80), and fungi (r = 0.59), indicating that phosphorus supply and fungal communities have a more pronounced influence on root growth. In comparison, its correlations with most bacterial indicators and nutrients were weaker (TN r = 0.69, MBC r = 0.73), suggesting that root biomass relies more on specific nutrients and fungal interactions rather than overall microbial activity.

Overall, soil nutrients (particularly nitrogen and organic matter) and bacterial-related microbial activities are closely associated with species richness, while root biomass is more related to phosphorus and fungi. These results reflect the synergistic mechanisms between vegetation restoration and soil microbial and nutrient cycling under desertification modes.

Soil quality evaluation of different vegetation communities under various desertification control models

The comprehensive SQI integrates various soil factors, and soil quality evaluation can sensitively reflect changes in the soil ecosystem and its capacity for restoration and degradation34. In this study, we perform PCA, using the contribution rate of each index’s eigenvalue as the weight. We calculate the chemical and microbiological index values of soil from different vegetation communities under three sand control models using a weighted approach. We then use the soil comprehensive index method to evaluate the overall health of the soil.

The original experimental data were standardized to obtain the membership values of soil quality indicators for different vegetation communities (Table 2). As Table 2 shows, compared with the mobile sand dune control, all indicators except pH had a membership value of zero. For PV-Ag (AO), the membership values for soil organic matter, total nitrogen, available nitrogen, available potassium, total microbial count, bacteria, and microbial biomass carbon and nitrogen were all one. Similarly, for ASS (HM), the membership values for total phosphorus, available phosphorus, and actinomycetes were all one, and for ASS (SP), the fungal membership value was also one.

The PCA results for evaluating soil quality indicators across different vegetation communities under three sand control models are shown in Table 3. Here, the variance contribution rate of the first principal component is 79.16%, and the cumulative variance contribution rate of the first and second principal components is 97.88%. It is widely accepted that a cumulative variance contribution rate above 85% effectively reflects the variability of the system. Thus, the first and second principal components adequately represent the variability of soil quality among the seven vegetation communities under the three sand control models. The first principal component mainly captures the integrated variables of organic matter, total nitrogen, available nitrogen, total microbial count, bacteria, and biomass carbon and nitrogen, highlighting their significant role in assessing soil quality. The second principal component focuses on the integrated variables of total phosphorus, available phosphorus, fungi, and actinomycetes, which also contribute to soil quality evaluation, albeit to a lesser extent.

The first and second principal component equations of the soil quality evaluation system are derived from the normalized eigenvectors, as follows:

By using the membership values of soil quality for different vegetation communities (Table 2) and their corresponding weight values (Table 3), we calculate the comprehensive SQI for each vegetation community using Eq. (3) (Table 4). Table 4 shows that the soil comprehensive index ranking is as follows: PV-Ag (AO) > PV-Ag (Wm) > PV-Ag (Po) > ASS (HM) > ASS (SP) > BS-PV (BS) > LS. A comparison of the SQI values shows that all vegetation communities significantly improve soil quality compared to the mobile sand dune control. Overall, the integrated photovoltaic-agriculture model (PV-Ag) significantly outperforms the artificial shrub aerial seeding model (ASS) and the bare sand with photovoltaic panels model (BS-PV).

Discussion and conclusion

Discussion

Differences in soil microbial characteristics under different desertification control modes and their driving factors

The results of this study indicate that different sand-fixing modes have significantly varying effects on improving soil properties, with the PV-Ag mode (the integrated photovoltaic-agriculture) demonstrating clear advantages in terms of soil nutrient content and microbial activity. Specifically, under this mode, soil organic matter content increased by 388.9%–544.4% compared to that in shifting sand dune (LS), while available nitrogen and available potassium showed average increases of 188.7% and 258.5%, respectively. The total microbial count increased more than tenfold, and microbial biomass carbon and nitrogen increased by 10.8–13.9 times and 13.4–17.1 times, respectively. This series of data indicates that the PV-Ag mode significantly enhances soil fertility and microbial functionality during the restoration of desert ecosystems.

From a soil microbial physiology perspective, the higher microbial biomass supported by the PV-Ag mode may stem from its improvement of soil physical structure and chemical environment. Under PV-Ag mode, the content of fine particles (silt, very fine sand, and fine sand) reached 92.9%, significantly increasing the soil’s specific surface area and pore structure. This not only enhanced nutrient adsorption and water retention capacity but also provided a more suitable habitat for microbial colonization and proliferation35,36,37,38. Simultaneously, the soil pH in the PV-Ag mode area decreased significantly (by 7.9–11.6%), approaching neutral levels. This change particularly favors the dominance of bacterial communities, as bacterial-dominated microbial systems typically exhibit higher organic matter decomposition efficiency and nutrient cycling rates39,40.

In contrast, soils under the ASS mode (artificial shrub aerial seeding) remained alkaline, with higher counts of fungi and actinomycetes, indicating functional adaptive adjustments of the microbial community structure in stressful habitats. Similarly, Wang et al.41 suggested that an increase in the soil fungi/actinomycetes ratio could serve as an indicator of soil quality degradation, which aligns with the relatively weaker microbial response and poorer nutrient conditions observed in the AAS and BS-PV modes in this study.

Compared to other arid region restoration projects globally, the increase in microbial biomass under the PV-Ag mode in this study was significantly higher than that reported in the Tengger Desert12,13. This may be attributed to the more efficient organic matter return and microclimate regulation achieved by the “photovoltaic-agriculture” integrated system used in this study. Similarly, studies on photovoltaic fields in the Mojave Desert of the United States also reported increases in soil microbial biomass and activity, though the increases were generally modest42. This may be attributed to the region’s lower precipitation and simpler vegetation types, which limit the intensity of interactions within the root-soil-microbial continuum. This could be due to lower precipitation and simpler vegetation types in the region, limiting the intensity of root-soil-microbial interactions.

In summary, the PV-Ag mode significantly enhances soil quality and ecological function in desert systems by synergistically optimizing soil physical structure, chemical properties, and microbial community functionality. The high level of microbial biomass benefits not only from the habitat space supported by fine particles but also from the enhanced carbon–nitrogen cycling driven by root-microbe interactions. These results highlight the great potential of the “photovoltaic-agriculture” integrated model in achieving dual goals of energy production and ecological restoration, providing a theoretical basis and practical pathway for comprehensive land management in arid regions.

It should be noted that all samples in this study were collected in July 2023, representing a single-season sampling design. Therefore, the potential effects of seasonal environmental changes (such as temperature, humidity, and vegetation phenology) on soil properties and microbial communities were not captured. This limitation may restrict the generalizability of our conclusions across the entire year. Future studies involving multi-season dynamic sampling would help provide a more comprehensive assessment of the long-term ecological effects and seasonal adaptability of sand-fixing modes.

PV-Ag mode significantly enhances soil fertility and microbial activity by optimizing hydrothermal environment

This study analyzed measured data on soil temperature, moisture, and various soil indicators under different sand-fixing modes (Fig. 10). The results revealed that the PV-Ag mode (herbaceous plant area under photovoltaic panels) exhibited superior soil hydrothermal conditions, with a soil moisture content of 0.043 m3/m3 and a soil temperature of 11.75 °C, outperforming both the AAS mode (moisture 0.013 m3/m3, temperature 10.86 °C) and the LS mode (moisture 0.011 m3/m3, temperature 13.55 °C). This relatively moist and thermally stable environment significantly promoted improvements in soil quality.

Specifically, under the PV-Ag mode, soil organic matter (SOM) content reached 2.9 g/kg, total nitrogen (TN) was 365 mg/kg, and microbial biomass carbon (MBC) was 125 mg/kg, substantially higher than those in the AAS mode (SOM 1.4 g/kg, TN 241 mg/kg, MBC 84 mg/kg) and the LS mode (SOM 0.5 g/kg, TN 56 mg/kg, MBC 9 mg/kg). Simultaneously, microbial populations in the PV-Ag area increased significantly, with bacteria reaching 132 × 10⁶ cfu/g, fungi at 32 × 104 cfu/g, and actinomycetes at 34 × 105 cfu/g. Root biomass was also the highest (1.8 g/kg) in this mode.

These findings demonstrate that the PV-Ag mode effectively enhances soil microbial activity and nutrient retention capacity by maintaining higher soil moisture and optimal soil temperature, thereby significantly improving soil fertility and ecological function. In contrast, the LS mode, characterized by poorer temperature and humidity conditions, exhibited the lowest levels across all soil indicators, further confirming the critical role of temperature and humidity regulation in the sand-fixing process.

Conclusion

-

(1)

The PV-Ag mode (the integrated photovoltaic-agriculture model) demonstrated the most outstanding performance in improving soil structure, nutrient content, and microbial activity. Its fine particle content reached 92.9%, while soil organic matter and total nitrogen content increased by 388.9%–544.4% and 476.7%–551.8%, respectively, compared to those in shifting sand dune (LS). The soil pH decreased by 7.9%–11.6%, approaching neutral levels. Under this mode, the total soil microbial count increased more than tenfold, microbial biomass carbon and nitrogen increased by 10.8–13.9 times and 13.4–17.1 times, respectively, and bacterial counts reached 132 × 10⁶ cfu/g, indicating excellent microbial-driven nutrient cycling capacity.

-

(2)

The PV-Ag mode effectively improved soil hydrothermal conditions through photovoltaic panel shading, with moisture (0.043 m3/m3) and temperature (11.75°C) superior to those of the GW and LS modes. This significantly promoted root biomass (1.8 g/kg) and the accumulation of available nitrogen and potassium (increases of 188.7% and 258.5%, respectively). Correlation analysis revealed that species richness was significantly positively correlated with organic matter, total nitrogen, and microbial carbon (r ≥ 0.96), while negatively correlated with pH (r = -0.95). In contrast, biomass was more closely associated with phosphorus and fungi (r ≥ 0.80), indicating differential driving mechanisms of soil nutrients and microbial communities on vegetation restoration.

-

(3)

Evaluation using the comprehensive soil quality index (SQI) showed that the SQI value under the PV-Ag mode increased by 810–1185 times compared to that in mobile dunes, significantly higher than that in the GW mode (2.5–3.9 times) and the AAS mode (11.3 times). These results demonstrate that the integrated “photovoltaic-agriculture” model not only significantly improves soil fertility and microbial activity but also provides a scalable practical pathway for ecological restoration in arid regions.

References

Berdugo, M. et al. Global ecosystem thresholds driven by aridity. Science 367(6479), 787–790 (2020).

Cui, G. P. et al. Combating desertification in the Great Green Wall Project: Scientific concepts, technologies, and achievements[J]. J. Desert Res. 45(3), 11–20 (2025) ((In Chinese)).

Li, C. et al. Drivers and impacts of changes in China’s drylands[J]. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2(12), 858–873 (2021).

Gu, Y. et al. Spatio-temporal dynamic monitoring of land desertification in Shangri-La city based on OSAVI-Albedo feature space[J]. Acta Ecol. Sin. 45(13), 6524–6543 (2025) ((In Chinese)).

Pravalie, R. Drylands extent and environmental issues: A global approach[J]. Earth Sci. Rev. 161, 259–278 (2016).

Reynolds, J. F. et al. Global desertification: Building a science for dryland development[J]. Science 316(5826), 847–851 (2007).

Song, C. C. et al. Application of photovoltaics on different types of land in China: Opportunities, status and challenges[J]. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 191, 114–116 (2024).

Zan, G. S., Wang, C. P., Li, F., Liu, Z. & Sun, T. Main results and analysis of the sixth national survey on desertification and sandification[J]. Forest Resources Manag. 1, 1–7 (2023).

Zhang, Z. H. & Huisingh, D. Combating desertification in China: Monitoring, control, management and revegetation[J]. J. Clean. Prod. 182, 765–775 (2018).

Liu, J. et al. Contributions of plant litter to soil microbial activity improvement and soil nutrient enhancement along with herb and shrub colonization expansions in an arid sandy land[J]. CATENA 227, 107098 (2023).

Hu, Y. F., Han, Y. Q. & Zhang, Y. Z. Land desertification and its influencing factors in Kazakhstan[J]. J. Arid Environ. 180, 104203 (2020).

Liu, Y. et al. Trampling to biocrusts declined soil microbial biomass and altered soil microbial communities in desert ecosystems[J]. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 206, 105879. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2025.105879 (2025).

Liu, Y. J. et al. Monitoring of wind erosion desertification process in the Mu Us Desert based on Google Earth Engine (GEE)[J]. J. Desert Res. 45(2), 262–274 (2025) ((In Chinese)).

Egidi, G. et al. Assessing the impact of multiple drivers of land sensitivity to desertification in a Mediterranean Country[J]. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 89(12), 106594 (2021).

Ahmed, Z. et al. An overview of global desertification control efforts: Key challenges and overarching solutions. Soil Use Manag. 40(4), 13154 (2024).

Al-Obaidi, J. R. et al. The environmental, economic, and social development impact of desertification in Iraq: A review on desertification control measures and mitigation strategies. Environ. Monit. Assess. 194(6), 440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-022-10102-y (2022).

You Y, Zhou N, Wang Y D. Comparative study of desertification control policies and regulations in representative countries of the Belt and Road Initiative[J]. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2021.e01577.

Wu, R. X. et al. Spatialtemporal dynamics and trend prediction of desertification land in the Hobq Desert from 1987 to 2022. Scientia Geographica Sinica 44(8), 1448–1458 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Effects of vegetation restoration on soil ecological stoichiometry in the eastern Kubuqi Desert [J]. Arid Zone Res. 39(03), 924–932 (2022) ((In Chinese)).

Shi, S. L. et al. Soil nutrients and stoichiometric characteristics of Elaeagnus angustifolia shelterbelts in the Kubuqi Desert [J]. Arid Zone Res. 39(02), 469–476 (2022) ((In Chinese)).

Han, Q. C. et al. Water conservation function of artificial forests in Hobq Desert[J]. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 43(6), 133–141 (2023) ((In Chinese)).

Wang, T. et al. Hydrological effects of understory litter and soil in artificial shelterbelts in the Kubuqi Desert [J]. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 30(04), 700–707 (2021) ((In Chinese)).

An D, Wang H B. Spatial distribution of typical shrub forests and their biomass in the Hobq Desert[D]. Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, 2024. (In Chinese)

Li H N, Meng Z J. Effects of Restoration of Typical Sand-fixing Vegetation in the Hobq Desert on Soil Quality and Bacterial Community Characteristics[D]. Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, 2024. (In Chinese)

Lu, L. Y. et al. Effects of three sand-fixing shrubs on soil water evaporation in the Hobq Desert. J. Arid Land Resources Environ. 39(03), 141–151 (2025) ((In Chinese)).

Li, Z. H. et al. Species richness is an important mediator of multifunctionality changes in Hobq desert shrub ecosystem[J]. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 29152. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14521-y (2025).

Meng, R. et al. Positive soil responses to different vegetation restoration measures in desert photovoltaic power stations. Front. Plant Sci. 16, 1607404. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2025.1607404 (2025).

Yin, J. et al. Interaction between aeolian processes and vegetation and its landscape effect in the southern fringe of Hobq Desert. Acta Ecol. Sin. 42(21), 8869–8880 (2022) ((In Chinese)).

Yang, H., Cao, J. & Hou, X. Characteristics of Aeolian Dune, Wind Regime and Sand Transport in Hobq Desert, China. Appl. Sci. 9(24), 5543. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9245543 (2019).

Zhang, L. X. et al. Soil microbial biomass and nutrient characteristics of different artificial sand-fixing shrub plantations in the Kubuqi Desert [J]. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 28(12), 3871–3880 (2017) ((In Chinese)).

Guo Y D, Zhang Q L Study on biomass and carbon density of artificial shrub forest in Hobq Desert[D]. Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, 2021. (In Chinese)

Yan, M. et al. Material redistribution of wind-sand flow and enrichment effect on nutrient elements over different underlying surfaces at the edge of Kubuqi Desert[J]. Arid Land Geogr. 46(06), 889–899 (2023) ((In Chinese)).

Dang, M. J. et al. Particle characteristics of surface sediment in the photovoltaic power station in the South Margin of the Hobq Desert[J]. Chin. J. Soil Sci. 50(2), 260–266 (2019).

Liu, Z. F. et al. Soil quality: Concept, indicators and its assessment[J]. J. Ecol. 26(3), 901–913 (2006).

Cheng, B. et al. Bioavailability of selenium nanoparticles in soil and plant: the role of particle size[J]. Environ. Exp. Bot. 220, 105682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2024.105682 (2024).

Luo, Z. P. et al. Dynamic of organic matter, nutrient cycling, and PH in soil aggregate particle sizes under long-term cultivation of Camellia Oleifera. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 24, 2599–2606 (2024).

Wu Z Q, Fan Y Q, Zhou Z Q, et al. Interaction between biochar particle size and soil salinity levels on soil properties and tomato yield. Biochar, 2025, 7(30).

Xiao, S. & He, Y. Application of near-infrared spectroscopy and multiple spectral algorithms to explore the effect of soil particle sizes on soil nitrogen detection. Molecules 24(13), 2486. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24132486 (2019).

Pan, Y. Q. et al. Response of the soil bacterial community to seasonal variations and land reclamation in a desert grassland. Ecol. Ind. 165, 112227 (2024).

Yuan, B. et al. Community structure, distribution pattern, and influencing factors of soil Archaea in the construction area of a large-scale photovoltaic power station. Int. Microbiol. 25(26), 571–586 (2022).

Wang, B. et al. Effects of vegetation restoration on wind-blown sand soil carbon flux and carbon storage in the Hobq Desert[J]. Soils 54(03), 539–546 (2022) ((In Chinese)).

Chen, X. et al. Response of vegetation and soil property changes by photovoltaic established stations based on a comprehensive meta-analysis. Land. 13(4), 478 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to all the staff members of the Urumqi Institute of Desert Meteorology, China Meteorological Administration.

Funding

This research was funded by the Intelligent Identification and Fine Forecasting Research on Cross-border Sand and Dust Weather Hazards in Mongolia (Grant no. U2242209); the “Tianshan Talent” Training Program-Science and Technology Innovation Team (Tianshan Innovation Team) Project (2022TSYCTD0007); the Youth Innovation Team of China Meteorological Administration (CMA2024QN13); The China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2022MD723851), and the S&T Development Fund of CAMS (2021KJ034).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mingjie Ma: Conceptualization; Writing-original draft. Fan Yang: Conceptualization, Writing-review and editing; Xiannian Zheng: Investigation; Xinghua Yang: Conceptualization; Ali Mamtimin: Data curation. Chenglong Zhou: Data curation; Chaofan Li: Investigation; Wen Huo: Data curation; Xinqian Zheng: Data curation; Tianhe Wang: Investigation; Peng He: Investigation; Qing Gong: Investigation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, M., Yang, F., Zheng, X. et al. Integrated photovoltaic-agriculture systems enhance soil health in desert ecosystems: evidence from microbial biomass and nutrient synergies. Sci Rep 16, 472 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29815-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29815-4