Abstract

The significance of photodegradation in litter decomposition has gained recognition in arid and semi-arid terrestrial ecosystems. However, few studies have directly examined the effects of photodegradation in hyper-arid regions (annual precipitation < 150 mm) and the role of microorganisms within this process. This study investigated how two different light conditions (full sun and shade) affected the one-year decomposition process of litter from three different species in a hyper-arid region. This study analyzed the impact of varying light conditions on litter mass loss and examined changes in the soil bacterial and fungal community composition during the decomposition process. This study found that litter exposed to environmental sunlight experienced a higher rate of mass loss compared to shade-exposed litter. Full sun conditions increased mass loss by 8.34% to 21.66%. During the litter decomposition process under full sun conditions, decomposition was not influenced by differences in initial litter composition, including variations in carbon, nitrogen, lignin, and cellulose contents. However, under shade conditions, Populus euphratica leaf litter, characterized by lower nitrogen and higher cellulose and C: N ratio, exhibited significantly lower mass loss compared to Alhagi sparsifolia and Karelinia caspia, indicating a slower decomposition of low-quality litter. Full sun conditions did not significantly change the number of bacterial and fungal ASVs in the hyper-arid desert soils during the litter decomposition period. During the litter decomposition process in the hyper-arid region, the dominant bacterial phyla were Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, and Bacteroidetes, while the dominant fungal phyla were Ascomycota and Basidiomycota. These results indicate that the higher mass loss under full sun was likely driven by the combined effects of photodegradation and microbial activity. Solar radiation plays a significant role in desert litter decomposition by accelerating mass loss, potentially through both direct photodegradation and indirect microbial facilitation, while microbial community structure remains resilient under high radiation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Litter decomposition is a critical process for carbon (C) and nutrient cycling in terrestrial ecosystems1,2. Dryland ecosystems, comprising roughly 41% of the Earth’s land area, are estimated to retain 27% of the planet’s soil organic C3, a C sink capacity related to the decomposition rate of plant litter4,5. In most ecosystems, the rates of litter decomposition and nutrient cycling are primarily controlled by factors such as climate, litter substrate quality, and the decomposer community6. However, in arid regions, especially in extremely arid areas, these factors do not entirely predict the rate of litter decomposition7. Despite extensive research, our understanding of the factors controlling litter decomposition and turnover in arid ecosystems remains unresolved.

The decomposition rate of litter is influenced by both biological and abiotic degradation processes8. Biogeochemical models that rely on traditional microbial degradation drivers, such as temperature, precipitation, and litter chemistry, often underestimate decomposition rates in arid environments9,10. Underestimations may derive from the high microenvironments heterogeneity that can be found in desert ecosystems (e.g. vegetation structure, soil/sand mobility)11,12,13. Photodegradation is a critical abiotic process in the decomposition of litter in arid ecosystems, which can significantly promote leaf litter breakdown14, although the magnitude of this effect varies with litter quality and climatic context. Microorganisms, pivotal in mineralizing soil organic matter across diverse ecosystems8, play a vital role in the process of litter decomposition15, thereby influencing nutrient cycling and ecosystem functioning. Investigating the impact of microorganisms on litter decomposition contributes to a better understanding of the mechanisms underlying litter decomposition16,17. Extensive research has unequivocally demonstrated the importance of microorganisms as primary decomposers in terrestrial ecosystems, wherein microbial activity and community composition directly govern rates of litter decomposition18,19. In arid regions, environmental conditions such as high solar radiation, elevated temperatures, and low soil moisture can constrain microbial activity, potentially limiting their contribution to decomposition20,21. The response of microbial communities to solar radiation remains a topic of debate. Photodegradation can affect microbial decomposition in different ways. For example, it can promote microbial decomposition through the disruption of recalcitrant compounds within leaf litter; However, solar radiation can also hinder microbial decomposition by suppressing microbial activity or altering the composition of microbial communities22,23. Some studies have reported that ultraviolet (UV) radiation, as part of photodegradation, can increase subsequent microbial decomposition, referred to as the “photo-priming effect”24,25,26. Austin and Ballaré27 observed that light-induced mass loss in plant litter was enhanced by both UV and visible radiation. However, Kirschbaum et al.28 did not find any significant influence of UV radiation on subsequent microbial decomposition. Such contradictory results could be caused by differences across ecosystem types. Thus, it is essential to investigate the role of photodegradation and microbial communities on leaf litter decomposition in those ecosystems currently understudied as those located in hyper-arid regions.

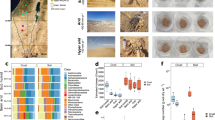

The Taklamakan Desert is the world’s second-largest mobile desert, receiving an annual average precipitation of less than 50 millimeters, classifying it as a hyper-arid desert. In the arid transition zone at the southern fringe of the Taklamakan Desert, there is a widespread presence of salt-tolerant and drought-resistant plants, including Alhagi sparsifolia, Karelinia caspia, and Populus euphratica. Due to the simplicity of vegetation communities and low organic matter content in hyper-arid regions, litter plays a vital role as a source of nutrients. The decomposition of litter is critical for maintaining the ecological balance and stability of desert ecosystems, influencing nutrient cycling, soil fertility, and biodiversity. Therefore, this study focused on the litter of three dominant species, Alhagi sparsifolia, Karelinia caspia, and Populus euphratica, at the transitional zone between the desert and oasis in the southern fringe of the Taklamakan Desert. Our research employed fixed-field sampling, laboratory quantitative analysis, and high-throughput sequencing techniques to investigate the decomposition of their litter. We aim to (i) assess how photodegradation affects the leaf litter decomposition process in hyper-arid regions; and (ii) investigate changes in microbial community structure during the photodegradation process. We studied the litter of three plant species: Alhagi sparsifolia, Karelinia caspia, and Populus euphratica. We analyzed the mass loss and decomposition rates of the three types of litter under both full sun and shaded conditions, and measuring microbial community structure, we explored the effects of photodegradation and microorganisms on litter decomposition in hyper-arid regions. We hypothesize that: (i) Full sun would increase the mass loss of all litter types; (ii) the magnitude of the photodegradation effect depends on litter quality, where photodegradation would have the greatest impact on high-quality litter; and (iii) in hyper-arid regions, high exposure to solar radiation is expected to alter soil microbial community structure. This study contributes to our further understanding of the photodegradation effects on leaf litter decomposition and mechanisms in hyper-arid regions. Additionally, it will facilitate the extension of litter decomposition models to more extensive arid climates.

Materials and methods

Study site

The study was conducted at the Cele Desert Grassland Ecosystem National Observation and Research Station, located at the junction of the Cele Oasis and the Taklamakan Desert (E 80°43’, N 37°00’). The study site features a warm-temperate desert climate with an annual average temperature of 11.9 °C. The annual precipitation in this region was less than 50 mm, and the annual average potential evaporation is 2595 mm29. The predominant soil type was sandy soil, which was characterized by poor water retention capacity, a low organic matter content (0.8%), and low total N (TN) content (0.6%). The pH levels range from 7 to 8. The ecosystem was fragile, with desert and Gobi areas covering approximately 95% of the region. The predominant vegetation consists of salt-tolerant and drought-resistant plants, including Alhagi sparsifolia, Karelinia caspia, Populus euphratica, Tamarix ramosissima, and Calligonum mongolicum. The vegetation cover was low, ranging from only 15% to 30%.

Experimental design and field sampling

The research materials consisted of the senescent leaves from Alhagi sparsifolia, Karelinia caspia, and Populus euphratica. The plant species Alhagi sparsifolia, Karelinia caspia, and Populus euphratica were identified by the authors based on morphological characteristics described in the Flora of China. Voucher specimens are available in the Herbarium of the Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences (PE), under accession numbers Alhagi sparsifolia (PE 02084936), Karelinia caspia (PE 02101442), and Populus euphratica (PE 02041065). The study collected new litter from the beginning of September to mid-October in 2019. Before the commencement of the experiments, the collected leaf litter was uniformly mixed and dried at 75 °C for 48 h to determine the initial dry mass30. We used the litter bag technique to determine leaf litter decomposition rates. In each litter bag (20 × 20 cm, 1 mm mesh size), we enclosed 20.00 g of leaf litter. The experiment commenced in November 2019 with a total of 240 litterbags placed on the soil surface. Three tree species were used, with two treatments (light exposure and shading), five replicates, and sampling conducted at eight different times. The experiment lasted for one year (from November 2019 to November 2020), and the loss of leaf litter from the litterbags was measured at 2, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12 months. To prevent the litterbags from being carried away by the wind, they were secured to stakes in the ground.

We established two radiation treatments: full sun and shade (using high-density polyethylene - HDPE - material nets that block 90.52%−96.13% of solar radiation while allowing rainfall to pass through) (Table S1). By measuring solar radiation levels under both full sun and shade conditions, with measurements taken at 10:00 AM and 2:00 PM Beijing time in China. Light radiation intensity was measured using a LI-250 A light meter (LI-COR, Lincoln, USA). The shading material nets were replaced every six months to prevent damage.

We collected soil adhering to the surface of litter in the 7th and 12th months of litter decomposition to assess microbial community diversity. Three litter bags were taken from each sampling site on each occasion. Additionally, soil samples from blank control sites under full sun conditions were collected as control (CK). The litter bags and soil samples from the blank control sites were placed in sterile bags and transported to the laboratory in an icebox kept at 4 °C. Using sterilized brushes within a laminar flow hood, soil adhering to the surface of the litter was collected and placed in sterile 1.5 ml centrifuge tubes. These samples were stored at − 20 °C for the assessment of soil microbial community diversity during litter decomposition.

Mass loss and litter chemistry analysis

The recovered litter bags were processed as follows: we used a 1 mm mesh sieve to remove sand and soil particles from the litter. Subsequently, the litter was dried in an oven at 75 °C for 48 h.

The formula for calculating mass remaining is as follows:

MR (%)=(Mt/M0)×100.

Where M0 is the initial litter mass (g), and Mt is the remaining litter mass (g) at time t.

The Olson negative exponential decay model was employed to calculate the decomposition constant (k)31:

MR = e− kt.

Where MR is the litter mass remaining (%), t is the elapsed time in years, and k is the annual decomposition rate (yr− 1).

Three sets of samples were taken for each type of litter and subjected to chemical analysis to determine the initial chemical composition of the undecomposed litter. The analyzed components of the initial litter composition primarily include parameters such as total C (TC), TN, cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin content. The TC and TN content were measured using a C-N elemental analyzer (Vario MACRO cube, Shimadzu, Japan). Cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin content were determined using a fiber determination instrument (FOSS, Hilleroed, Denmark).

Microbial bioinformatics analysis

Total DNA of soil microorganisms was extracted using the OMEGA E.Z.N. Soil DNA Kit (Omega Bio-Tek, Norcross, GA, USA). Subsequently, a 2 × 300 bp paired-end sequencing was performed using a MiSeq sequencer (Shanghai Biochip Company, Shanghai, China). For bacteria, the V3-V4 hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers 338 F (5’-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCA-3’)/806R (5’-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3’)32. For fungi, the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) 1 region was amplified using PCR primers ITS5 (5’-GGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG-3’)/ITS2 (5’-GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC-3’)33. Gel electrophoresis was used to evaluate the amplification quality of PCR products. Subsequently, PCR products meeting the standards were purified and mixed in proportion according to DNA concentration and molecular weight to generate Illumina® DNA libraries. Paired-end DNA samples were sequenced on the Illumina MiSeq platform. The sequencing datasets generated in this study have been deposited in the NCBI BioProject repository and are publicly accessible under the accession number PRJNA1081794.

After sequencing, the DADA2 method was applied to remove mismatched primer sequences, followed by sequence quality control, denoising, trimming, and removal of chimeric sequences34. Subsequently, the sequences were quality-filtered, dereplicated, and clustered at a 98% similarity threshold using the Vsearch plugin, followed by a final round of chimera removal to generate the amplicon sequence variant (ASV) table and representative sequences. A total of 42 soil samples were sequenced, with three replicates per treatment. For bacterial 16 S rRNA gene sequencing, an average of 90,050 raw reads per sample were obtained, of which 45,814 high-quality reads were retained after quality filtering. This resulted in 28,587 amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) with a total read abundance of 28,663. For ITS sequencing, an average of 106,797 raw reads per sample were generated, of which 86,751 high-quality reads were retained, yielding 1,533 ASVs with a total abundance of 62,411 reads. These sequences were used for downstream analyses of microbial community composition and diversity. The 16 S rRNA and ITS genes were annotated using the Silva (Release 132)35 and UNITE (Release 8.0)36 databases, respectively. Soil microbial alpha diversity indices, including the sample richness index (Chao1) and diversity index (Shannon), were computed using QIIME2 software (version 2019.4).

Statistical analyses

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and least significant difference (LSD) tests were employed to assess differences in leaf litter nutrient content, k values, and microbial community structure among the leaf litter species used in the experiment. Furthermore, the LSD test was conducted to examine differences between species (p < 0.05). Two-way ANOVA was used to analyze the effects and interactions of treatment and decomposition time on litter mass remaining, and used a two-way ANOVA to analyze the effects and interactions of treatment and species on the k values. An independent-samples t-tests were used to evaluate differences in litter mass remaining between the two radiation treatments. We employed Pearson correlation analysis to investigate the relationship between the k values and initial nutrient content of litter, microbial abundance, and microbial diversity. Prior to statistical data analyses, the normality of data was analyzed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and the homogeneity of variance was analyzed using Levene’s test. Box-Cox transformation was conducted when necessary. All statistical analyses were conducted using QIIME2 and R software (version 4.2.0). Using the “ggplot2” package37 in R software for data visualization.

Results

Initial leaf litter traits

Leaf litter of the 3 species selected differed in leaf traits (Table 1). Alhagi sparsifolia litter had the highest N content but the lowest C: N ratio, hemicellulose, and lignin content (p < 0.05), indicating relatively high litter quality. Karelinia caspia litter exhibited the highest hemicellulose and lignin content, reflecting a more recalcitrant, low-quality litter type. Populus euphratica litter exhibited the highest C and cellulose content, and C: N ratio, but the lowest N concentration (p < 0.05), also representing a low-quality litter type due to its nutrient limitation and high structural carbon content.

Litter mass loss and decomposition rate

The decomposition trends of leaf litter from Alhagi sparsifolia, Karelinia caspia, and Populus euphratica were generally similar under full sun and shade conditions, but there were significant differences in the decomposition time and mass loss of litter under different light conditions (Fig. 1). The decomposition exhibited a rapid initial phase followed by a slower phase, which appears to commence around the 7th month of decomposition (Fig. 1). After 12 months of decomposition, the leaf litter mass loss was significantly higher under full sun compared to shade conditions (p < 0.05). Specifically, for Alhagi sparsifolia, Karelinia caspia, and Populus euphratica, the decomposition in full sun was 13.69%, 8.34%, and 21.66% higher, respectively, than under shade conditions (Fig. 1). When there was full sun, the k values of leaf litter from all three plant species were significantly higher than under shade conditions (p < 0.05), indicating a higher decomposition rate (Fig. 2).

Mass decomposition constants (k) of litter under light and shade. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between species (p < 0.05), while different uppercase letters indicate significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05), (mean ± SE). A. sparsifolia: Alhagi sparsifolia; K. caspia: Karelinia caspia; P. euphratica: Populus euphratica.

Two-way analysis of variance indicates that both litter species and different light treatments significantly influence the k values. Under full sun conditions, there were no significant differences in the k values of the three types of leaf litter (p > 0.05; Fig. 2). However, under shade conditions, the k values of Populus euphratica leaf litter was significantly lower than those of Alhagi sparsifolia and Karelinia caspia (Fig. 2).

Bacterial diversity and community composition

In the 7th month of litter decomposition, the number of Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) in the CK soil bacterial community was the highest (Fig. 3). During this period, under shade conditions, the number of ASVs in the soil bacterial community adhering to the surface of Alhagi sparsifolia litter was significantly higher than that under full sun conditions (p < 0.05). However, there were no significant differences (p > 0.05) in the number of ASVs adhering to the surface of soil bacterial communities associated with Karelinia caspia and Populus euphratica litter independently of the treatment. By the 12th month of litter decomposition, there were no significant differences in the number of ASVs in the soil bacterial communities associated with the litter of all three plant species independently of the treatment (Fig. 3).

The number of Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) in soil bacterial communities during litter decomposition (A) Sampled at 7 months of litter decomposition; (B) Sampled at 12 months of litter decomposition. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among treatments (p < 0.05), (mean ± SE). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among treatments. A. sparsifolia: Alhagi sparsifolia; K. caspia: Karelinia caspia; P. euphratica: Populus euphratica. CK represents soil samples from the blank control plots.

An analysis of the top 10 species at the phylum level for soil bacterial abundance revealed that during the entire decomposition process of the three leaf litters, the predominant phyla were Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Firmicutes (Fig. 4). In the soil associated with Alhagi sparsifolia and Karelinia caspia leaf litters, Proteobacteria constituted the most abundant phylum, representing 35.22% to 64.34% of the bacterial community composition for Alhagi sparsifolia and 48.77% to 53.56% for Karelinia caspia. In the soil associated with Populus euphratica litter, Firmicutes was the most abundant phylum, accounting for 42.17% to 52.23% of the bacterial community composition (Fig. 4).

Soil bacterial community composition and alpha diversity during litter decomposition for three plant species under full sun (F) and shade (S) conditions. (A–D) Bacterial community composition at the phylum level; (E–H) alpha diversity indices (Chao1 and Shannon). (A, E) Alhagi sparsifolia; (B, F) Karelinia caspia; (C, G) Populus euphratica; (D, H) CK. T1 represents sampling at 7 months of litter decomposition, and T2 represents sampling at 12 months of litter decomposition. CK represents soil samples from the blank control plots. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among treatments.

Analyzing the diversity of soil microbial bacteria adhering to the surface of litter under full sun or shade, it was found that in the 7th month of litter decomposition, under full sun, the Chao1 index and Shannon index of soil associated with Alhagi sparsifolia litter were lower than those under shade conditions (Fig. 4). Under full sun, the Chao1 index and Shannon index of soil associated with Populus euphratica litter were significantly higher than those under shade conditions (p < 0.05). In the 12th month of leaf litter decomposition, different light conditions did not affect the species richness and diversity of soil microbes. Comparing soil bacterial alpha diversity of litters at different decomposition stages, it was observed that, regardless of full sun or shade conditions, the Chao1 index and Shannon index in the 12th month of leaf litter decomposition were lower than those in the 7th month of leaf litter decomposition (Fig. 4).

Fungal diversity and community composition

In the 7th and 12th months of leaf litter decomposition, there was no significant effect on the fungal ASV richness of Alhagi sparsifolia and Karelinia caspia litter (Fig. 5). However, in the 7th month of litter decomposition, the number of ASVs in the surface soil fungal community of Populus euphratica litter under shade conditions was significantly higher than under full sun conditions (p < 0.05).

The number of Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) in soil fungal communities during litter decomposition (A) Sampled at 7 months of litter decomposition; (B) Sampled at 12 months of litter decomposition. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among treatments (p < 0.05), (mean ± SE). A. sparsifolia: Alhagi sparsifolia; K. caspia: Karelinia caspia; P. euphratica: Populus euphratica. CK represents soil samples from the blank control plots.

Throughout the entire decomposition process of leaf litter from the three plant species, the dominant phylum in the fungal community was Ascomycota (Fig. 6). In the 7th month of litter decomposition, Ascomycota constituted 99.43% to 99.96% of the total fungal community, while in the 12th month of decomposition, Ascomycota accounted for 93.27% to 99.86% of the entire fungal community. The second most prevalent phylum was Basidiomycota. Additionally, the soil also contained smaller proportions of other phyla, such as Mucoromycota, Mortierellomycota, Chytridiomycota, and others (Fig. 6).

Soil fungal community composition and alpha diversity during litter decomposition for three plant species under full sun (F) and shade (S) conditions. (A–D) Fungal community composition at the phylum level; (E–H) alpha diversity indices (Chao1 and Shannon). (A, E) Alhagi sparsifolia; (B, F) Karelinia caspia; (C, G) Populus euphratica; (D, H) CK. T1 represents sampling at 7 months of litter decomposition, and T2 represents sampling at 12 months of litter decomposition. CK represents soil samples from the blank control plots. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among treatments.

In the 7th and 12th months of decomposition, the Chao1 index of soil microbial fungi adhering to the surface of litter from the three plant species was relatively higher under shade conditions (Fig. 6). Specifically, under shade conditions, the Chao1 index of soil microbial fungi adhering to the surface of litter from the Populus euphratica was significantly higher than that under full sun (p < 0.05). There were no significant differences in the Shannon index of soil microbial fungi adhering to the surface of litter from the Alhagi sparsifolia and Karelinia caspia during the decomposition process. However, during the 7th month of decomposition, the Shannon index of soil microbial fungi adhering to the surface of litter from the Populus euphratica was significantly higher under shade conditions than under full sun (p < 0.05; Fig. 6). Comparing the fungal alpha diversity of litters at different stage decomposition, it was observed that both the Chao1 and Shannon indices of litter in the 12th month were higher than those in the 7th month, under both full sun and shade conditions (Fig. 6).

The relationship between initial leaf litter traits, soil microbial communities, and litter decomposition

Correlation analysis reveals that when all three factors are included in the analysis, under full sun conditions, the abundance (ASVs_bacterial) and Chao1 index (Chao1_bacterial) of bacterial microorganisms exhibit a positive correlation with decomposition rate (k), while the abundance (ASVs_fungal) and Chao1 index (Chao1_fungal) of fungal microorganisms show a negative correlation (p < 0.05; Fig. 7A). Under shade conditions, the initial litter TC content, litter C: N, and initial cellulose content exhibit a negative correlation with decomposition rate (k) (p < 0.05; Fig. 7B).

Correlation analysis between litter decomposition constant (k) and initial leaf litter traits and microbial communities. (A) Full sun; (B) Shade. Red indicates negative correlation, while blue indicates positive correlation (p < 0.05). The numbers below the figure represent correlation coefficients. TC: total carbon content; TN: total nitrogen content; C: N: carbon: nitrogen; ASVs_ bacterial: the number of Amplicon Sequence Variants in the soil bacterial community; Chao1_bacterial: the Chao1 index within the context of the soil bacterial community; Shannon_bacterial: the Shannon index within the context of the soil bacterial community; ASVs_fungal: the number of Amplicon Sequence Variants in the soil fungal community; Chao1_fungal: the Chao1 index within the context of the soil fungal community; Shannon_ fungal: the Shannon index within the context of the soil fungal community.

Discussion

Main decomposition elements of litter in hyper-arid regions

Consistent with our first hypothesis, shade significantly decelerated the rate of litter mass loss (Figs. 1 and 2). This suggests that photodegradation plays a substantial role in the turnover of litter in arid ecosystems. We observed an increase in litter mass loss of up to 21.66% when leaf litter was exposed to full sun conditions (Fig. 1). Similarly, in a meta-analysis, King et al.38 found that litter exposed to environmental solar radiation decomposed faster than those subjected to reduced solar radiation. Photodegradation is the process of direct decomposition of organic materials by solar radiation, causing C to enter the atmospheric C cycle directly rather than entering the soil C pool14. An increasing body of research suggests that in arid and semi-arid ecosystems, UV radiation is a significant driving force behind litter decomposition39,40. In our study, we observed a significant reduction in litter mass loss for all three types of litter under full sun conditions compared to shade conditions (Figs. 1 and 2). Our study results support the hypothesis that photodegradation significantly enhances litter decomposition.

Compared to high-quality litter, low-quality litter typically has lower N content, higher C: N ratios, and higher lignin and cellulose content, resulting in slower decomposition rates41. The study by Berg et al.42 suggests that litter with higher N content decomposes more rapidly. Microbial abundance and activity are often inversely related to C: N, with lower C: N litter having higher decomposition rates43. Results obtained in arid ecosystems may sometimes appear contradictory. In our study, despite significant differences in the initial quality of litter among the three species regarding N content and C: N, and although bacterial diversity and richness (as indicated by Chao1, Shannon indices, and ASV number) were inversely related to C: N, decomposition of litter with different initial qualities showed no significant differences under full sun conditions (Figs. 2 and 7). Under shade conditions, Populus euphratica, characterized by higher C concentration, C:N, and cellulose content, exhibited the slowest decomposition (Table 1; Fig. 2). This study results suggest that while high-quality litter (characterized by higher N concentrations and lower C: N) typically decomposes faster than low-quality litter44,45, this phenomenon is only evident under shade conditions in hyper-arid regions. Under shade conditions, the decomposition rate of litter is negatively correlated with TC content, litter C: N, and initial cellulose content (Fig. 9). This is contrary to a portion of our second hypothesis, the study revealed that under shade conditions, higher-quality litter decomposed most rapidly, whereas under full sun conditions, the study did not observe significant differences. Shade reduces radiation and conserves moisture, creating a more favorable microenvironment that promotes microbial activity and accelerates the decomposition of high-quality litter. Our findings suggest that even in the extreme hyper-arid environment, where light conditions are diminished, both biotic and abiotic decomposition emerge as primary drivers of litter mass loss. As expected, the study found that photodegradation remains a crucial pathway for litter decomposition in arid areas.

Impact of sunlight on soil microbiota composition in the process of litter decomposition

Contrary to our third hypothesis, although the number of ASVs in leaf litter from the three plant species was greater under shade conditions than under full sun, solar radiation did not significantly reduce the ASV richness of bacteria and fungi during litter decomposition (Figs. 3 and 5). This suggests that microbial communities in arid ecosystems may possess adaptations to solar radiation46. Prolonged exposure can select for microbes that are more resistant to solar radiation or better at utilizing photodegraded compounds. In the case of bacteria, some traits enabling growth in arid, sunny environments, such as pigment deposition, are associated with large geographic ranges47, aiding dispersion and allowing individuals to thrive in a broader range of environments. In this extremely arid land, many dominant fungi are global species, suggesting that certain fungi might also be resistant to solar radiation. Several instances indicate that solar radiation can have detrimental effects on microbial communities, inhibiting microbial growth and damaging microbial DNA46,48. However, these negative impacts do not necessarily always occur. Baker and Allison49 found that microbial enzyme activity is higher and more effective under environmental solar radiation compared to reduced solar treatments, as microbes adapt better to the ambient environment, even in the presence of relatively higher solar radiation.

Microorganisms play a crucial role in driving the biogeochemical cycles of elements such as C and N. They exhibit a high sensitivity to changes in soil conditions, which can result in alterations in soil microbial diversity50. In this study, the number of ASVs for bacteria and fungi in the control soil was higher than that adhering to the surfaces of leaf litter from the three desert plants (Figs. 3 and 5). Species analysis of soil microbial fungi revealed that the leaf litter surfaces of the three plants and the control soil contained the same nine fungal phyla and some unidentified phyla (Figs. 4 and 6). This suggests that microbial communities in the same environmental conditions can share a similar broad-scale taxonomic composition (e.g., at the phylum level), but during the process of litter decomposition, the composition of decomposers may vary51.

Soil microorganisms play an important role in the decomposition of litter52. Soil microorganisms involved in litter decomposition mainly include fungi and bacteria, and their synergistic interactions are crucial factors in accelerating litter decomposition53. However, confirming this synergy requires future validation through cross-domain network analysis. Among soil microbial communities, soil bacteria are the most abundant in terms of both abundance and diversity. They primarily inhabit the spaces created by fungal activity, and most bacteria play a role in facilitating litter decomposition54. During litter decomposition, the phyla Proteobacteria exhibit broad ecological ranges and strong adaptability to soil nutrients55,56,57. Similarly, in our study, the main bacterial phyla adhering to the surface of litter during decomposition were Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Firmicutes (Fig. 4). The phyla Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria have been identified as critical factors in organic matter decomposition58. In our study, we observed that during the later stages of litter decomposition, the species richness and diversity of soil microbial fungal communities increased, while the species richness and diversity of bacterial communities decreased (Figs. 4 and 6). This pattern likely reflects the increasing chemical complexity of residual litter over time, as more labile compounds are depleted and recalcitrant substrates such as lignin and cellulose remain. The enhanced fungal diversity in the later stages may therefore be linked to their ability to adapt to and utilize these more complex carbon sources. This phenomenon can be attributed to the slower growth rate of fungi compared to bacteria, enabling them to decompose more recalcitrant and complex organic materials59,60. Fungi are considered key participants in the litter decomposition process due to their capacity to degrade challenging compounds such as lignin, and their dominant role in cellulose and hemicellulose decomposition61,62. Ascomycota and Basidiomycota are typically recognized as the predominant fungal phyla at the soil-litter interface63. Basidiomycota and Ascomycota are major soil fungi, playing essential roles in litter decomposition and soil nutrient cycling64. Basidiomycota produces lignin-degrading enzymes, primarily breaking down lignin and other recalcitrant substances, while Ascomycota is responsible for the decomposition of cellulose and hemicellulose in litter65. This aligns with the results of our study, where the predominant fungal phyla in the decomposition of leaf litter from the three plant species were Ascomycota, followed by Basidiomycota (Fig. 6). Ascomycota constituted 93.27% to 99.96% of the entire fungal community, while Basidiomycota accounted for 0.02% to 6.67% (Fig. 6). Our findings indicate the significant role of Ascomycota in litter decomposition, consistent with previous research66. Ascomycota emerges as a primary contributor to litter decomposition and is more abundant than Basidiomycota61.

This study suggests that in hyper-arid regions, solar radiation exerts a notable influence on litter decomposition, particularly where microbial activity may be constrained by extreme environmental conditions. Under such conditions, non-biological processes such as photodegradation make substantial contributions to mass loss, although microbial activity still plays a critical role. The relative contributions of photodegradation and microbial activity may vary with litter type, microhabitat, and moisture availability. Future studies using quantitative approaches such as Hierarchical Partitioning analysis could help disentangle the respective effects of sunlight and microbial processes on decomposition.

Conclusions

Compared to reduced sunlight, full sun conditions significantly increased litter mass loss by 8 to 22%, indicating that photodegradation plays a beneficial role in litter decomposition within hyper-arid desert ecosystems. Under full sun conditions, decomposition rates were less influenced by differences in initial litter composition, whereas under shade conditions, low-quality litter decomposed significantly slower. These results suggest that while photodegradation can accelerate decomposition under high radiation, microbial activity and litter quality remain important determinants of decomposition dynamics. In the litter decomposition process in hyper-arid regions, dominant bacterial phyla include Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, and Bacteroidetes, while dominant fungal phyla comprise Ascomycota and Basidiomycota.

In summary, our research provides evidence for the broader implications of photodegradation, extending the significance of solar radiation in plant litter decomposition to ecosystems subjected to moisture limitations. This holds crucial implications for our understanding of biogeochemical cycles in terrestrial ecosystems. Furthermore, given that the extent of photodegradation depends on climatic conditions, it is essential to gain a better understanding and incorporate it into mechanistic models to accurately predict climate-related variations.

Data availability

The sequencing datasets generated in this study are publicly available in the NCBI BioProject repository under accession number PRJNA1081794 (https://www.ncbi.nlm. nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1081794).

References

Berg, B. & McClaugherty, C. Plant Litter: decomposition, Humus formation, Carbon Sequestration (Springer, 2008).

Campos, A., Cruz, L. & Rocha, S. Mass, nutrient pool, and mineralization of litter and fine roots in a tropical mountain cloud forest. Sci. Total Environ. 575, 876–886 (2017).

Huang, J., Yu, H., Guan, X., Wang, G. & Guo, R. Accelerated dryland expansion under climate change. Nat. Clim. Change. 6 (2), 166–171 (2016).

Throop, H. L. & Archer, S. R. Resolving the dryland decomposition conundrum: some new perspectives on potential drivers. Progress in botany: Springer 171 – 94. (2009).

Poulter, B. et al. Contribution of semi-arid ecosystems to interannual variability of the global carbon cycle. Nature 509 (7502), 600–603 (2014).

Cornwell, W. K. et al. Plant species traits are the predominant control on litter decomposition rates within biomes worldwide. Ecol. Lett. 11 (10), 1065–1071 (2008).

Gholz, H. L., Wedin, D. A., Smitherman, S. M., Harmon, M. E. & Parton, W. J. Long-term dynamics of pine and hardwood litter in contrasting environments: toward a global model of decomposition. Glob. Change Biol. 6 (7), 751–765 (2000).

Georgiou, C. D. et al. Evidence for photochemical production of reactive oxygen species in desert soils. Nat. Commun. 6 (1), 7100 (2015).

Parton, W. et al. Global-scale similarities in nitrogen release patterns during long-term decomposition. Science 315 (5810), 361–364 (2007).

Adair, E. C. et al. Simple three-pool model accurately describes patterns of long‐term litter decomposition in diverse climates. Glob. Change Biol. 14 (11), 2636–2660 (2008).

Breshears, D. D., Rich, P. M., Barnes, F. J. & Campbell, K. Overstory-imposed heterogeneity in solar radiation and soil moisture in a semiarid woodland. Ecol. Appl. 7 (4), 1201–1215 (1997).

Throop, H. L. & Archer, S. R. Interrelationships among shrub encroachment, land management, and litter decomposition in a semidesert grassland. Ecol. Appl. 17 (6), 1809–1823 (2007).

Throop, H. L. & Archer, S. R. Shrub (Prosopis velutina) encroachment in a semidesert grassland: spatial–temporal changes in soil organic carbon and nitrogen pools. Glob. Change Biol. 14 (10), 2420–2431 (2008).

Austin, A. T. & Vivanco, L. Plant litter decomposition in a semi-arid ecosystem controlled by photodegradation. Nature 442 (7102), 555–558 (2006).

McGuire, K. L. & Treseder, K. K. Microbial communities and their relevance for ecosystem models: decomposition as a case study. Soil Biol. Biochem. 42 (4), 529–535 (2010).

Lajtha, K., Bowden, R. D. & Nadelhoffer, K. Litter and root manipulations provide insights into soil organic matter dynamics and stability. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 78 (S1), S261–S9 (2014).

Hobara, S. et al. The roles of microorganisms in litter decomposition and soil formation. Biogeochemistry 118, 471–486 (2014).

Sun, Q. et al. Grassland management regimes regulate soil phosphorus fractions and conversion between phosphorus pools in semiarid steppe ecosystems. Biogeochemistry 163 (1), 33–48 (2023).

Zeng, Q., Liu, Y., Zhang, H. & An, S. Fast bacterial succession associated with the decomposition of Quercus Wutaishanica litter on the loess plateau. Biogeochemistry 144 (2), 119–131 (2019).

Duguay, K. J. & Klironomos, J. N. Direct and indirect effects of enhanced UV-B radiation on the decomposing and competitive abilities of saprobic fungi. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 14 (2), 157–164 (2000).

Wang, J. et al. Temporal dynamics of ultraviolet radiation impacts on litter decomposition in a semi-arid ecosystem. Plant. Soil. 419, 71–81 (2017).

Berenstecher, P., Vivanco, L., Pérez, L. I., Ballaré, C. L. & Austin, A. T. Sunlight doubles aboveground carbon loss in a seasonally dry woodland in patagonia. Curr. Biol. 30 (16), 3243–3251 (2020). e3.

Pancotto, V. A. et al. Solar UV-B decreases decomposition in herbaceous plant litter in Tierra Del Fuego, argentina: potential role of an altered decomposer community. Glob. Change Biol. 9 (10), 1465–1474 (2003).

Gaxiola, A. & Armesto, J. J. Understanding litter decomposition in semiarid ecosystems: linking leaf traits, UV exposure and rainfall variability. Front. Plant Sci. 6, 140 (2015).

Huang, G., Zhao, H. & Li, Y. Litter decomposition in hyper-arid deserts: photodegradation is still important. Sci. Total Environ. 601, 784–792 (2017).

Lin, Y., Karlen, S. D., Ralph, J. & King, J. Y. Short-term facilitation of microbial litter decomposition by ultraviolet radiation. Sci. Total Environ. 615, 838–848 (2018).

Austin, A. T. & Ballaré, C. L. Dual role of lignin in plant litter decomposition in terrestrial ecosystems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. ;107(10):4618-22. (2010).

Kirschbaum, M. U., Lambie, S. M. & Zhou, H. No UV enhancement of litter decomposition observed on dry samples under controlled laboratory conditions. Soil Biol. Biochem. 43 (6), 1300–1307 (2011).

Gui, D., Zeng, F., Liu, Z. & Zhang, B. Characteristics of the clonal propagation of alhagi sparsifolia Shap.(Fabaceae) under different groundwater depths in Xinjiang, China. Rangel. J. 35 (3), 355–362 (2013).

Zhao, H., Huang, G., Ma, J., Li, Y. & Tang, L. Decomposition of aboveground and root litter for three desert herbs: mass loss and dynamics of mineral nutrients. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 50, 745–753 (2014).

Olson, J. S. Energy storage and the balance of producers and decomposers in ecological systems. Ecology 44 (2), 322–331 (1963).

Claesson, M. J. et al. Comparative analysis of pyrosequencing and a phylogenetic microarray for exploring microbial community structures in the human distal intestine. PloS ONE. 4 (8), e6669 (2009).

White, T. J., Bruns, T., Lee, S. & Taylor, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. PCR Protocols: Guide Methods Appl. 18 (1), 315–322 (1990).

Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods. 13 (7), 581–583 (2016).

Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41 (D1), D590–D6 (2012).

Kõljalg, U. et al. Towards a unified paradigm for sequence-based identification of fungi. Mol. Ecol. 22, 5271–5277 (2013).

Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis 2nd edn (Springer, 2016).

King, J. Y., Brandt, L. A. & Adair, E. C. Shedding light on plant litter decomposition: advances, implications and new directions in Understanding the role of photodegradation. Biogeochemistry 111 (1), 57–81 (2012).

Gallo, M. E., Porras-Alfaro, A., Odenbach, K. J. & Sinsabaugh, R. L. Photoacceleration of plant litter decomposition in an arid environment. Soil Biol. Biochem. 41 (7), 1433–1441 (2009).

Day, T. A., Zhang, E. T. & Ruhland, C. T. Exposure to solar UV-B radiation accelerates mass and lignin loss of Larrea tridentata litter in the Sonoran desert. Plant Ecol. 193, 185–194 (2007).

Mooshammer, M. et al. Stoichiometric controls of nitrogen and phosphorus cycling in decomposing Beech leaf litter. Ecology 93 (4), 770–782 (2012).

Berg, B. Litter decomposition and organic matter turnover in Northern forest soils. For. Ecol. Manag. 133 (1–2), 13–22 (2000).

Taylor, B. R., Parkinson, D. & Parsons, W. F. Nitrogen and lignin content as predictors of litter decay rates: a microcosm test. Ecology 70 (1), 97–104 (1989).

Sanchez, F. G. Loblolly pine needle decomposition and nutrient dynamics as affected by irrigation, fertilization, and substrate quality. For. Ecol. Manag. 152 (1–3), 85–96 (2001).

Su, Y., Zhao, H., Li, Y. & Cui, J. Carbon mineralization potential in soils of different habitats in the semiarid Horqin sandy land: a laboratory experiment. Arid Land. Res. Manage. 18 (1), 39–50 (2004).

Caldwell, M. M., Bornman, J., Ballaré, C., Flint, S. D. & Kulandaivelu, G. Terrestrial ecosystems, increased solar ultraviolet radiation, and interactions with other climate change factors. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 6 (3), 252–266 (2007).

Choudoir, M. J., Barberán, A., Menninger, H. L., Dunn, R. R. & Fierer, N. Variation in range size and dispersal capabilities of microbial taxa. Ecology 99 (2), 322–334 (2018).

Rohwer, F. & Azam, F. Detection of DNA damage in prokaryotes by terminal deoxyribonucleotide transferase-mediated dUTP Nick end labeling. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66 (3), 1001–1006 (2000).

Baker, N. R. & Allison, S. D. Ultraviolet photodegradation facilitates microbial litter decomposition in a mediterranean climate. Ecology 96 (7), 1994–2003 (2015).

Eisenhauer, N. Plant diversity effects on soil microorganisms: Spatial and Temporal heterogeneity of plant inputs increase soil biodiversity. Pedobiologia 9, 175–177 (2016).

Logan, J. R., Jacobson, K. M., Jacobson, P. J. & Evans, S. E. Fungal communities on standing litter are structured by moisture type and constrain decomposition in a hyper-arid grassland. Front. Microbiol. 12, 596517 (2021).

Purahong, W. et al. Effects of forest management practices in temperate Beech forests on bacterial and fungal communities involved in leaf litter degradation. Microb. Ecol. 69, 905–913 (2015).

Wright, M. & Covich, A. Relative importance of bacteria and fungi in a tropical headwater stream: leaf decomposition and invertebrate feeding preference. Microb. Ecol. 49, 536–546 (2005).

Loranger, G., Ponge, J-F., Imbert, D. & Lavelle, P. Leaf decomposition in two semi-evergreen tropical forests: influence of litter quality. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 35, 247–252 (2002).

Větrovský, T. & Baldrian, P. The variability of the 16S rRNA gene in bacterial genomes and its consequences for bacterial community analyses. PloS ONE. 8 (2), e57923 (2013).

García-Palacios, P., McKie, B. G., Handa, I. T., Frainer, A. & Hättenschwiler, S. The importance of litter traits and decomposers for litter decomposition: a comparison of aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems within and across biomes. Funct. Ecol. 30 (5), 819–829 (2016).

Xue, J., Xiao, N., Wang, Q. & Wu, H. Seasonal variation of bacterial community diversity in Yangshan Port. Acta Ecol. Sin. 36 (23), 7758–7767 (2016).

Jurado, M. et al. Exploiting composting biodiversity: study of the persistent and biotechnologically relevant microorganisms from lignocellulose-based composting. Bioresour. Technol. 162, 283–293 (2014).

Marschner, P., Umar, S. & Baumann, K. The microbial community composition changes rapidly in the early stages of decomposition of wheat residue. Soil Biol. Biochem. 43 (2), 445–451 (2011).

Rantalainen, M-L., Kontiola, L., Haimi, J., Fritze, H. & Setälä, H. Influence of resource quality on the composition of soil decomposer community in fragmented and continuous habitat. Soil Biol. Biochem. 36 (12), 1983–1996 (2004).

Boer Wd, Folman, L. B., Summerbell, R. C. & Boddy, L. Living in a fungal world: impact of fungi on soil bacterial niche development. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 29 (4), 795–811 (2005).

Meidute, S., Demoling, F. & Bååth, E. Antagonistic and synergistic effects of fungal and bacterial growth in soil after adding different carbon and nitrogen sources. Soil Biol. Biochem. 40 (9), 2334–2343 (2008).

Osono, T. & Takeda, H. Fungal decomposition of abies needle and betula leaf litter. Mycologia 98 (2), 172–179 (2006).

Du, C. et al. Seasonal dynamics of bacterial communities in a betula albosinensis forest. Eur. J. Soil. Sci. 69 (4), 666–674 (2018).

Baldrian, P. Forest microbiome: diversity, complexity and dynamics. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 41 (2), 109–130 (2017).

Li, P. et al. Rice straw decomposition affects diversity and dynamics of soil fungal community, but not bacteria. J. Soils Sediments. 18, 248–258 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We appreciated staffs at the Cele Station for field work. This study was supported by the Tianshan Talent Training Program (No. 2024TSYCLJ0028) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42171066).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Linjie Fan: Formal analysis; investigation; methodology; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Lisha Lin: Investigation; Conceptualization. Xiangyi Li: Conceptualization; funding acquisition; methodology; project administration; resources; supervision; validation; writing – review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fan, L., Lin, L. & Li, X. Mass decomposition dynamics and soil microbial community changes during the photodegradation process of leaf litter from three plant species in hyper-arid deserts. Sci Rep 15, 45417 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29836-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29836-z