Abstract

Addressing the challenge of coal pillar stability control in gob-side entries of gently inclined coal seams, this study utilizes the 7134 working face of a specific mine as an engineering case. By integrating theoretical analysis, numerical simulation, physical similarity modeling, and field monitoring, the research comprehensively investigates the mechanism of pre-cutting pressure relief technology and bilateral reinforcement of coal pillars, along with their impact on the stability of surrounding rock in roadways. The study reveals the critical role of cutting parameters in blocking stress transfer from the overlying strata of the goaf to the roadway, identifying the optimal pre-cutting scheme (18 m height, 90° angle) that effectively eliminates the influence of main roof rotation and squeezing on the coal pillar. Innovatively, the core mechanism concerning the relative positioning of the anchored sections within the bilateral support structures of the coal pillar is elucidated: when the support bodies create overlapping zones within the pillar, a “tension-anchoring effect” is generated. This effect significantly improves the internal stress distribution, effectively constrains the bulking deformation of the coal pillar, and inhibits crack development, thereby substantially enhancing the overall stability and load-bearing capacity of the narrow coal pillar. Building upon this mechanism, the research also proposes a novel design method for determining the length of anchor cables on the ribs of narrow coal pillars, identifies key design parameters, and validates the reliability of this method through similarity simulation and field engineering practice. Field application demonstrates that employing a combined support system with high pre-stressed bolts and cables effectively controls roadway surrounding rock deformation, significantly improving safety and stability throughout the service life of the roadway. This research provides a theoretical foundation and an effective technical approach for controlling surrounding rock stability in gob-side entries of gently inclined coal seams.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent years have witnessed continuous advancement in coal mining technology, leading to the widespread application of narrow coal pillar gob-side entry driving in mine roadways in China1,2,3,4. The stability of the coal pillar is a critical factor for the successful implementation of this technology, as it directly influences the effectiveness of surrounding rock control5. Therefore, systematically exploring effective methods to enhance the stability and load-bearing capacity of narrow coal pillars is of great significance for ensuring safe and efficient coal mining.

Existing research on the stability of narrow coal pillars in gob-side entry driving has mainly progressed along three aspects.

The first aspect focuses on the optimization of coal pillar width. For various mining conditions such as thick coal seams, closely spaced coal seams, and deep soft coal seams, systematic methods for determining reasonable coal pillar widths have been developed6,7,8,9,10,11, providing a theoretical basis for pillar width design under different geological conditions. Among these, Li Feng et al.12 investigated gently inclined medium-thick coal seams and derived reasonable section coal pillar dimensions. Zaisheng Jiang et al.13 addressed the challenges of coal pillar design and support in deep, high-stress soft coal seams for gob-side entry driving. Using theoretical calculations and numerical simulation, they determined an appropriate pillar width and proposed a combined support technology.

The second aspect concerns roadway surrounding rock control. For different engineering conditions, diverse surrounding rock control systems have been established, including combined bolt-cable support14,15,16, synergistic support integrating bolts/cables with grouting17, and coordinated control technology combining bolts/cables with internal pressure relief18. Notably, Chen Dongdong et al.19,20 proposed innovative technologies involving asymmetric pressure relief in the rib coal mass and related rock pressure monitoring. These technologies demonstrated satisfactory application results through numerical simulation and engineering validation. Xianyu Xiong et al.21 established a multi-factor coupled strength criterion for roadways in gently inclined coal seams and proposed a zonal differentiated support strategy. Lianpeng Dai et al.22,23 introduced a rockburst control mechanism based on the theory of “constant-resistance large-deformation support and multi-balance points in the surrounding rock,” laying a theoretical foundation for the quantitative design of support systems in high-stress roadways.

The third aspect involves controlling the surrounding rock through roof cutting. Employing integrated research methods combining theoretical analysis, numerical simulation, physical modeling, and engineering practice24,25,26,27,28,29,30, systematic studies have been conducted on the effectiveness of various pressure relief methods, including hydraulic fracturing31 and deep-hole blasting32,33,34,35,36,37,38. These studies provide multiple technical solutions for controlling surrounding rock stability under different geological conditions.

The aforementioned research has laid a crucial foundation for stability control of narrow coal pillars in gob-side entry driving with roof cutting. However, two key issues remain to be addressed. Firstly, most studies focus predominantly on evaluating the individual effectiveness of either roof cutting or unilateral coal pillar reinforcement, generally neglecting the synergistic mechanism between goaf-side roof cutting for entry protection and high-side coal pillar reinforcement within the narrow coal pillar structure, particularly under conditions where the coal seam possesses a certain dip angle. Secondly, the spatial synergistic effects of support elements during coal pillar reinforcement and their influence mechanism on stability have not yet been systematically revealed.

To address these gaps, this study, set against the background of gently inclined coal seams, initiates for the first time an investigation into the synergistic mechanism between roof cutting for entry protection and bidirectional reinforcement of the coal pillar. It focuses on exploring the following key issues: (1) the influence of different roof cutting heights and angles on the fracture patterns of the main roof; (2) the formation conditions and functional mechanisms of the overlapping effect of anchorage zones from bilateral support bodies within the coal pillar (i.e., the “interlocking anchorage” mechanism); (3) the control mechanism of the synergistic action of bilateral support on coal pillar stability. By integrating numerical simulation39, physical similarity simulation, and field measurement, this research aims to systematically reveal the synergistic relationships between roof cutting parameters and the support system, thereby providing an effective theoretical basis and technical approach for surrounding rock control in gob-side entry driving under gently inclined coal seam conditions.

Project overview and difficulty analysis

Engineering geological conditions

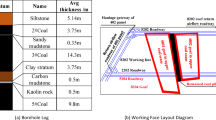

Panel 7134 is situated in the East Wing No. 7 Mining District of the minefield. It is bounded by the goaf of Panel 7126 to the north, the unmined Panel 7173 to the south, the setup entry to the east, and lies approximately 30 m west of the No. 7 Mining District Auxiliary Haulage Drift. The buried depth of 7134 working face is about 620 m. The primary mining seam of Panel 7134 is the Carboniferous-Permian No. 7 coal seam, mined at a depth of 610 m. The coal seam exhibits a dip angle ranging from 12° to 18°, with an average of 15°. The average seam thickness is 3.5 m, and the seam structure is relatively simple. The immediate roof consists of 5.4 m of mudstone, while the immediate floor comprises 1.7 m of mudstone. The main roof is composed of 11.7 m of sandstone. The stratigraphic column of the coal seam is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Field investigations of the ground pressure behavior in the tailgate and headgate of adjacent Panel 7126 (which are trapezoidal roadways with a higher side of 4.6 m, a lower side of 3.7 m, and a width of 5.2 m, driven horizontally along the bottom to form semi-coal-rock entries) revealed significantly challenging geological conditions in the inner sections. Controlling roadway stability proved highly difficult due to poor conditions in both ribs and the roof, resulting in severe roadway deformation. The roadway deformation site is shown in Fig. 2. The layout of the working face is shown in Fig. 3.

Main difficulties

(1) Extremely Poor Geological Conditions in Inner Sections: The geological conditions in the inner sections of the panel headgate and tailgate are extremely poor, significantly increasing the difficulty of stability control. Due to the considerable thickness of the overlying strata, the time required for them to reach a stable state is prolonged. Consequently, effectively managing support efficacy and controlling surrounding rock deformation are critical priorities during the roadway driving stage.

(2) Complex Geological Structure and High-Stress Environment: The area features complex geological structures and is situated at a significant depth, resulting in a high-stress environment. This high-stress field substantially impacts the stability of the roadway surrounding rock.

(3) Severe Mining Impact and Fragmented Coal Pillar Rib: The coal pillar rib is subjected to significant mining-induced disturbances. Furthermore, the coal pillar is predominantly loose and fragmented. The relatively short bolt length typically anchors only within the fractured zone of the coal rib, failing to provide effective support.

(4) Sensitivity to Pre-Cutting Parameters and Reinforcement Mechanism: Improper pre-cutting height or angle will lead to severe roadway deformation and adversely affect coal pillar stability. It is essential to investigate reasonable pre-cutting parameters. Furthermore, the influence of the bidirectional bolt-cable reinforcement mechanism within the coal pillar on its overall stability requires detailed analysis.

Aiming at the aforementioned engineering challenges associated with gob-side entry driving in gently inclined coal seams, this study integrates the actual site conditions. Utilizing numerical simulation, physical similarity simulation, theoretical analysis, and theoretical calculation methods, a multidimensional systematic investigation into the principles of pre-cutting entry driving and the mechanism of coal pillar bidirectional reinforcement is conducted. The goal is to achieve synergistic optimization of pre-cutting parameter selection and the bidirectional reinforcement mechanism, thereby enhancing roadway support effectiveness and ensuring long-term project stability.

Principles of Gob-Side entry driving with Pre-Cutting in gently inclined coal seams

Pre-cutting pressure relief technology optimizes the stress environment of roadway surrounding rock by actively controlling the fracture location of the roof strata and the stress transfer path within the overlying rock. When the deviation between the pre-cutting angle and the coal seam dip angle is minimal, it can guide the roof to fracture along the predetermined cutting line, avoiding asymmetric deformation caused by deviation of the stress transfer path. Research indicates that determining the cutting angle based on caving angle theory requires comprehensive consideration of the rotation and subsidence behavior of the roof strata after fracture. Furthermore, the pre-cutting angle significantly influences the control of roof bed separation; a rational angle design can mitigate disturbances to roadway stability caused by roof rotation and subsidence.

Study on Pre-Cutting angle

To investigate the caving behavior of the goaf roof and the variation patterns of surrounding rock stress under different pre-cutting angles for gob-side entry driving with pre-cutting in gently inclined coal seams, a numerical model (Fig. 4) was established using the discrete element software UDEC(7.00 www.itascacg.com/staging/cn/software/udec). The model dimensions are length × height = 125 m × 115 m. The simulated roadway has a width of 5.2 m, a lower rib height of 3.5 m, a higher rib height of 4.6 m, and employs a coal pillar width of 5.5 m, consistent with field practice.

The upper boundary of the model applies a stress boundary condition, simplified as a uniformly distributed load. The bottom boundary employs a displacement boundary condition, fixed in the vertical direction and unconstrained horizontally. The left and right boundaries, representing coal-rock masses, are also modeled with displacement boundary conditions, fixed horizontally and unconstrained vertically. Rock blocks are simulated using the Mohr-Coulomb constitutive model, while joints are modeled using the Coulomb slip model. The mechanical parameters of the coal and rocks are listed in Table 1. Pre-split cutting seams with varying angles and heights were simulated by excavation to replicate field pre-splitting operations. This setup allowed observation of the main roof caving behavior under different pre-cutting angles and heights, and its subsequent impact on the stability of the surrounding rock during entry driving.

To systematically investigate the influence of the roof-cutting angle on the stability of the surrounding rock, this study initially took the 90° vertical roof-cutting scheme as a benchmark and conducted a comparative analysis of several adjacent angles, including 95°, 85°, and 80°. The results indicated that while a 5° angular interval induced continuous variations in the stress state of the surrounding rock, it was insufficient to cause fundamental changes in the roof fracture pattern. The differences between the various working conditions were minor, exhibiting limited representativeness. Based on this finding, a 15° interval was ultimately selected as a typical increment to balance research efficiency with the need to adequately reveal the underlying patterns.

Following the above research design, a roof-cutting height of 18 m was selected to ensure complete severance of the main roof. The roof-cutting angle was varied within the range of 75° to 120° at 15° increments, establishing four representative scenarios: 75°, 90°, 105°, and 120°. Using a combined approach of simulation experiments and theoretical analysis, this study systematically examines the characteristics of stability changes in the roadway and overlying strata under different roof-cutting angles. This provides crucial data support and a theoretical basis for the subsequent optimization and determination of roof-cutting parameters.

As shown in Fig. 5, at 75° and 90°, main roof block B fractured entirely along the pre-cut line and collapsed into the goaf. This confirms both angles completely severed the main roof (overlying strata of the gob-side entry) and fully disrupted stress transfer between the goaf and roadway overburden. The overlying strata formed a stable cantilever beam, eliminating rotational extrusion impacts on the coal pillar. However, in practice, the 75° angle faces significant implementation challenges due to drilling rig constraints. In contrast, the 90° angle proved more feasible, offering construction convenience, lower operational difficulty, and better quality assurance.

At 105° and 120° (Fig. 5), main roof block B fractured but bridged over block A due to excessive inclination, failing to disrupt stress transfer. This subjected the coal pillar and roadway to excessive stress concentrations, causing severe deformation. Both angles are therefore unsuitable.

Systematic simulations and analysis confirm the 90° vertical pre-cutting angle delivers superior stability control and operational feasibility, establishing it as the optimal solution.

Study on Pre-Cutting height

The pre-cutting height must satisfy the fundamental requirement of severing the key load-bearing strata while balancing pressure relief effectiveness with construction costs. Theoretical analysis indicates that the pre-cutting height should cover the critical fracture zones within both the immediate roof and the main roof to eliminate the cantilever beam effect. For hard roof strata, an increased cutting depth is necessary to sever thick main roof layers, thereby creating an effective pressure relief space. Conversely, for fractured roof strata, an insufficient pre-cutting height will result in continuous subsidence of the residual roof. Furthermore, the design of the pre-cutting height must coordinate with the coal pillar dimensions and the support system. This coordination aims to reconstruct the overlying strata into a “Cantilever Beam-Voussoir Beam” structure, enabling collapsed gob debris and the coal pillar to cooperatively bear the overburden load, thereby establishing a stable stress equilibrium system.

By employing FLAC3D 6.0 and UDEC 7.0 numerical simulations, the deformation characteristics of the roadway and the stability of the surrounding rock under different pre-cutting heights were modeled. Different fracture line positions were observed to investigate a rational pre-cutting height.

According to the bulking theory, the roof-cutting height is closely related to the working face mining height and the bulking coefficient. To accurately calculate the roof-cutting height, the calculation formula was determined based on principles of engineering mechanics and field geological parameters40.

In the formula,M represents the mining height of the working face (coal seam thickness: 3–4 m); Kp denotes the average bulking coefficient of the rock strata (typically Kp = 1.2–1.3). Comprehensive calculations determined an effective pre-cutting height of 16–18 m.

Under gob-side entry driving with pre-cutting, analyzing overlying strata block structure and coal pillar deformation is critical. UDEC 7.0 discrete element software was selected for its capability to accurately simulate rock block movements. Simulations examined four cases: no pre-cutting, 6 m, 12 m, and 18 m pre-cutting heights, focusing on overlying strata behavior and surrounding rock deformation.

As shown in Fig. 6, at 6 m height, insufficient cutting allowed main roof fracture lines to develop either above the coal pillar or roadway. Fractures above the pillar caused main roof rotation-induced extrusion pressure on the narrow pillar, substantially increasing gob-side roadway instability. Fractures above the roadway subjected both pillar and roadway to excessive stress concentrations, risking roof falls and severe pillar rib deformation that compromised stability and increased support complexity. This height fails to maintain stability, necessitating increased cutting.

At 12 m height, fracture lines remained above the roadway or pillar (Fig. 6b), indicating incomplete severance of the main roof. The persistent stress transfer linkage between goaf and solid coal overburden meant the narrow pillar remained vulnerable to main roof rotation-induced deformation, rendering roadway maintenance challenging despite partial pressure relief. Further height increase was required.

At 18 m height (Fig. 6c), main roof block B fractured completely along the cut line and collapsed into the goaf, confirming complete severance of the main roof and full disruption of stress transfer linkage. The overburden formed a stable cantilever beam structure, eliminating roof rotation impacts on the pillar and significantly reducing surrounding rock control difficulties. This height is optimal for gob-side entry stability.

In summary, under the condition of no pre-cutting, the fracture line of the main roof may develop above the coal pillar, the roadway, or the solid coal. As shown in Fig. 7, the characteristic where the fracture line occurs above the coal pillar is highlighted. In this scenario, the rotation of the main roof exerts significant extrusion pressure on the coal pillar, leading to substantial deformation of the roadway. This deformation arises because the coal pillar itself, being relatively narrow and possessing limited load-bearing capacity, cannot effectively resist the extrusion forces imposed by the main roof. Continuous squeezing of the pillar by the main roof significantly reduces the pillar’s stability.

Furthermore, Fig. 8 presents the vertical stress distribution obtained from FLAC3D 6.0 numerical simulations, comparing scenarios with no pre-cutting and an 18 m pre-cutting height. Analysis reveals a significant pressure relief effect: after pre-cutting implementation, the maximum vertical stress on the solid coal rib side decreased by 5.9 MPa, while the maximum vertical stress above the coal pillar decreased by 3 MPa.

Comprehensive analysis demonstrates that without pre-cutting, maintaining the stability of both the coal pillar and the gob-side roadway would be unattainable. Implementing pre-cutting technology is therefore essential to effectively sever the stress linkage between the overlying strata of the goaf and the gob-side roadway zone. This effectively shields the coal pillar and roadway from the detrimental effects of main roof rotation and extrusion.

In summary, failure to implement pre-cutting measures would critically compromise the stability of the coal pillar and gob-side roadway. Consequently, adopting pre-cutting technology is imperative to effectively disrupt the stress transfer path within the overlying strata between the goaf and the gob-side roadway area, thereby preventing extrusion forces induced by main roof rotation on the pillar and roadway. This technical measure not only significantly enhances the stability of the coal pillar and gob-side roadway but also provides a reliable foundation for their long-term safety and functional integrity.

Bidirectional reinforcement mechanism of coal pillar in gently inclined coal seams

Coal pillar bidirectional reinforcement mechanism

The stability of narrow section coal pillars is influenced by multiple factors beyond overlying strata characteristics and pillar width, with internal support conditions playing a critical role. Narrow pillars, as unique support targets, typically employ bolt or cable reinforcement on both ribs. Crucially, the relative positioning of these bilateral support elements within the coal pillar significantly impacts stability—specifically, whether they form an overlapping zone creating an opposing anchor structure directly determines stability performance.

When bilateral bolt/cable supports lack interior overlap, the structure fails to establish effective internal connectivity. Under overall plastic deformation of the narrow pillar, support elements on each rib exert counteracting tensile forces toward their respective surrounding rock. This induces reverse stretching forces within the pillar core, exacerbating stress concentration and damage propagation, thereby significantly compromising stability.

FLAC3D 6.0 numerical simulations modeling pre-stress fields of varying bolt/cable lengths (using a consistent 5.5 m pillar width matching field conditions) revealed critical mechanics. As evidenced in Fig. 9 Non-overlapping pre-stressed field diagram of bilateral support of coal pillar (2.4 m anchor cable), absent interior overlap: minimum principal pre-stress and horizontal pre-stress components reside within compressive zones while maximum stress concentrates near the goaf-side rib—accelerating pillar failure. Simultaneously, highly non-uniform vertical pre-stress distribution prevents effective constraint of peripheral coal mass, establishing an inhomogeneous stress state extremely detrimental to stability.

Furthermore, as schematically illustrated in Fig. 10 Non-overlapping schematic diagram of bilateral support of coal pillar (2.4 m anchor cable), when the cable length on the gob-side entry pillar rib is 2.4 m, the support bodies on both sides of the coal pillar fail to form an overlapping zone within its interior. Under this condition, the anchoring force direction of the cables in the newly driven entry segment opposes that of the cables in the original roadway. This configuration subjects the narrow coal pillar, already in its plastic deformation stage, to counteracting tensile forces from the bilateral support systems. Consequently, the instability of the pillar’s core region is significantly exacerbated.

Under compressive loading, the pillar deforms laterally outward, resulting in severe deformation of the pillar ribs. Simultaneously, the opposing tensile effect from both ends induces substantial damage deformation and crack propagation within the pillar’s central region. This progressive damage ultimately leads to a complete loss of the pillar’s load-bearing capacity, triggering significant roadway deformation and failure. When the support bodies within the pillar cannot establish an opposing anchor zone, the stability of the coal pillar cannot be effectively ensured.

As depicted in Fig. 11 showing the pre-stress field for bilateral pillar support without overlap (using 3.2 m cables), when the support bodies on both sides of the coal pillar are positioned further inward yet still fail to form an overlapping zone, the minimum principal pre-stress and horizontal pre-stress components on the pillar sides remain within compressive stress regions. Comparatively, while the maximum stress concentration zone shifts toward the pillar center relative to the 2.4 m cable pre-stress field, it predominantly persists near the goaf-side rib. This persistent lateral stress concentration significantly exacerbates pillar failure. Simultaneously, although the distribution of vertical pre-stress across the pillar sides shows improvement compared to the 2.4 m cable scenario, its overall uniformity remains poor. Consequently, while the constraint capacity on the peripheral coal mass is somewhat enhanced, it remains insufficient to effectively restrain pillar deformation and falls short of meeting pillar stability requirements.

As schematically illustrated in Fig. 12 coal pillar bilateral support non-overlapping schematic diagram (3.2 m anchor cable), increasing the cable length on the gob-side entry pillar rib to 3.2 m brings the bilateral support bodies closer within the coal pillar interior, yet still fails to establish an effective overlapping zone. Compared to the 2.4 m cable scenario, despite the increased cable length, the anchoring force direction in the newly driven entry segment remains opposite to that in the original roadway. Consequently, the narrow coal pillar, operating within its plastic stage, continues to experience significant core instability induced by the counteracting tensile forces from the bilateral supports, with no fundamental improvement achieved. Under compressive loading, the pillar deforms laterally outward, resulting in severe pillar rib deformation. Simultaneously, the persistent opposing tensile effect from both ends continues to cause substantial damage deformation and pronounced crack propagation within the pillar’s central region. While roadway deformation shows some improvement, it remains severe overall. Critically, the pillar’s load-bearing capacity remains inadequate. This demonstrates that although increasing cable length provides some stability enhancement, effective stability cannot be fully ensured when the support bodies fail to form a functional opposing anchor zone within the pillar. The extent of cable length increase remains insufficient to meet pillar stability requirements.

As shown in Fig. 13 Coal pillar bilateral support partially overlapping prestressed field diagram (4.3 m anchor cable), when the support bodies on both sides of the coal pillar possess sufficient length to form an overlapping zone within its interior, the minimum principal pre-stress and horizontal pre-stress components on the pillar sides reside entirely within compressive stress regions. Crucially, the maximum stress concentration zone is centralized within the pillar’s core, enabling the pillar’s load-bearing capacity to be fully mobilized and thereby significantly contributing to pillar stability. Simultaneously, the vertical pre-stress exhibits uniform distribution across the pillar sides, establishing a continuous and extensive compressive stress zone. This configuration provides exceptionally strong constraint capacity over a large peripheral volume of the coal mass, effectively restraining pillar deformation and thus achieving the required pillar stability.

As schematically illustrated in Fig. 14 coal pillar bilateral support partial overlap schematic diagram (4.3 m anchor cable), when the cable support length in the original roadway is increased to 3.5 m and the cable length on the gob-side entry pillar rib is extended to 4.3 m, the support bodies on both sides of the coal pillar form an overlapping zone within its interior, establishing an opposing anchor reinforcement zone. The relative positioning of the bolts/cables is shown in Fig. 15 coal pillar bilateral support schematic diagram (there are some overlapping areas). In this configuration, the anchoring forces from the cables in the newly driven entry segment and the original roadway are interlocked and opposing, generating a counter-tension effect between the bilateral support bodies. This counter-tension effect effectively constrains bulking expansion deformation of the narrow coal pillar (operating in its plastic stage) towards both ribs, significantly enhancing pillar stability. Consequently, deformation of both pillar ribs is minimal. Furthermore, due to the counter-tension effect of the support system, the pillar interior remains stable, exhibiting virtually no damage deformation or crack propagation within the central region. Overall pillar stability remains robust.

In summary, the opposing-anchorage technique for coal pillars significantly enhances pillar stability, increases its load-bearing capacity, and effectively reduces the risk of failure due to uneven stress distribution. This technique is particularly advantageous for the stability of narrow section pillars.

Based on the aforementioned mechanistic analysis, this study reveals the critical role of the effective interlocking anchorage effect formed by the support system within the narrow coal pillar. This effect is of paramount importance for designing the cable bolt length in the rib of a gob-side entry. Accordingly, this research innovatively proposes a new method for determining the cable bolt length in the rib of a narrow coal pillar. The core design principle of this method is the establishment of an effective “interlocking anchorage zone” as the design criterion. Relying on the principle of stress field superposition, the method involves the scientific selection of cable bolt lengths to ensure sufficient overlap (≥ 1.0 m) of the anchorage segments from both sides within the coal pillar, thereby fully activating its interlocking constraint function. This design facilitates the formation of a continuous compressive stress zone inside the coal pillar, effectively optimizes the stress state, controls deformation, and ultimately transforms the fragmented coal mass into a composite load-bearing structure with high integrity.

Simulation experiment

To systematically investigate the mechanism of bidirectional reinforcement technology for coal pillars in gently inclined gob-side entry driving, laboratory physical similarity model tests were conducted. Based on the actual geological conditions of the working face, a corresponding physical similarity model was constructed. During the model construction phase, pre-embedded miniature self-made bolts and cables were employed to accurately simulate the field support system. The experiment strictly followed the sequential procedure of “working face excavation → pre-cut roof splitting → gob-side entry driving → coal pillar stability testing.” Systematic observations and comparative analyses were conducted to examine the deformation characteristics, fragmentation patterns, and ground pressure behavior of the narrow coal pillar under different bolt and cable lengths.

Strata of different lithologies were constructed using mixtures of lime, gypsum, river sand, and water with varying proportions. Specimens with these proportions underwent rock mechanical testing to achieve specified strength requirements. Based on in-situ stress measurements and similarity scaling principles, hydraulic jacks applied a vertical load of 15.2 kN to the model surface to replicate field stress conditions. Three models were prepared, differing exclusively in bolt/cable length while maintaining identical geological and loading parameters. The initial state before the experiment begins is shown in Fig. 16, Schematic Diagram of the Physical Similarity Simulation Experiment.

Similarity simulation results are shown in Fig. 17. The simulations reveal that with a cable length of 2.4 m, insufficient anchoring depth prevented the formation of an effective opposing anchor zone within the pillar. Severe deformation and fragmentation occurred, with partial cable exposure due to pillar fragmentation compromising anchoring functionality. Loading further exacerbated deformation. Failure analysis indicated progressive fragmentation initiating from the pillar core toward both ribs under overburden stress. Particularly severe rib fragmentation substantially reduced load-bearing capacity, rendering the pillar incapable of supporting overburden pressure and critically undermining support system stability—confirming this scheme’s inability to ensure pillar integrity.

Increasing cable length to 3.2 m improved stability marginally, yet still failed to establish an effective opposing anchor zone. Significant deformation and fragmentation persisted during loading, with localized rib deformation. Although moderately reduced compared to the 2.4 m case, fragmentation severity remained substantial, indicating continued failure to guarantee stability.

At 4.3 m cable length, an effective opposing anchor zone formed within the pillar, maintaining overall integrity. Support efficacy was fully realized with no central deformation or fragmentation, confirming successful stabilization. Thus, the 4.3 m cable scheme ensures pillar stability.

In summary, comparative simulations demonstrate cable length’s critical influence: insufficient lengths preclude opposing anchor zone formation, causing severe deformation/fragmentation and drastic load-bearing reduction. Adequate cable lengths enable effective opposing anchor zones, mobilizing full support capacity to significantly enhance stability and load-bearing performance. This underscores that establishing an opposing anchor zone through bidirectional reinforcement is paramount for pillar stability, and rationally increasing cable length is essential for optimizing support design in underground coal mine entries.

Engineering practice

Based on previous numerical simulations, physical similarity simulations, and other studies, and comprehensively considering on-site construction conditions, economic factors, and tunneling safety, the roof-cutting angle was determined as 90°, the roof-cutting height as 18 m, and the coal pillar width as 5.5 m. Gob-side entry driving with roof pre-cutting was implemented in the 7134 working face’s machine gateway. To effectively ensure the stability of the surrounding rock in the retained roadway, high pre-stressed cable bolts were adopted. This maximizes the improvement of the stress state of the surrounding rock, guarantees the stability of the coal pillar, and reduces roadway deformation.

Roadway support scheme

The specific layout of the support is shown in Fig. 18 (Roadway Support Diagram).

(1) Roof Support: A combined bolt and cable bolt support system was employed. The bolts have a diameter of 20 mm, a length of 2.4 m, and are spaced at 800 mm × 800 mm. The bolt plates are arched square plates measuring 150 × 150 × 12 mm. The cable bolts have a diameter of 21.8 mm, a length of 7.3 m, and are spaced at 1050 mm × 1600 mm. The cable bolt plates measure 300 × 300 × 16 mm. Each row of bolts and cable bolts is connected by steel straps. The pre-tension force of the cable bolts is no less than 300 kN.

(2) Coal Pillar Rib Support: Full cable bolt support was used. High pre-tensioned cable bolts with a diameter of 21.8 mm and a length of 4.3 m were installed at a spacing of 1000 mm × 1000 mm. The cable bolt plates are 300 × 300 × 16 mm. Each row of cable bolts is connected by steel straps. Following support installation, a thin layer of shotcrete with a specified strength of C20 and an approximate thickness of 100 mm was applied to the coal pillar rib.

(3) Solid Coal Rib Support: A combined bolt and cable bolt support system was applied to the solid coal rib. The bolts have a diameter of 20 mm, a length of 2.4 m, and are spaced at 800 mm × 800 mm. The cable bolts have a diameter of 21.8 mm, a length of 4.3 m, and are spaced at 1600 mm × 1625 mm. Each row of bolts and cable bolts is connected by steel straps.

Roadway displacement monitoring

To evaluate the effectiveness of the support, displacement measurements were conducted within the roadway using the cross-point method. A laser rangefinder was employed to measure distances at designated points, primarily monitoring deformations of the roof and both ribs. Measurements were conducted at a fixed frequency of once every 3 days over a continuous 60-day period, yielding 20 complete sets of valid data. The layout of the roadway displacement monitoring sections is shown in Fig. 19.

Field monitoring data revealed that the deformation of the surrounding rock exhibited distinct stage-specific characteristics following roadway excavation. As shown in the monitoring curve of surrounding rock displacement in Fig. 19, three clear deformation phases were observed: during the initial stage (0–15 days), deformation increased rapidly as the surrounding rock underwent stress redistribution; in the intermediate stage (15–36 days), the deformation rate significantly decreased, entering a phase of stable growth; after 36 days, the deformation essentially stabilized. This convergence characteristic demonstrates that stress within the surrounding rock has been effectively redistributed and a stable bearing structure has formed. The support system has proven effective in controlling surrounding rock deformation. Upon stabilization, deformation measurements showed the coal pillar rib surface experienced the maximum displacement of approximately 78 mm, while the solid coal rib and roof deformations reached about 69 mm and 54 mm, respectively. All deformation values remained within reasonable engineering limits. The control effect on the rock mass surrounding the roadway was satisfactory, meeting the requirements for safe production and achieving effective control of the surrounding rock in the gob-side entry.

Conclusions

(1) Comparative studies on surrounding rock deformation in gob-side entry driving within gently inclined coal seams under different roof-cutting parameters revealed that improper parameters cause the main roof fracture line to locate above the entry or coal pillar, severely impacting the gob-side entry. It was comprehensively determined that a roof-cutting scheme with a height of 18 m and an angle of 90° can completely sever the stress connection between the overlying strata of the goaf and the gob-side entry. This effectively prevents the impact of main roof rotation and extrusion deformation on the entry and significantly enhances the stability of the gob-side entry.

(2) Research on the influence of the relative positions of bilateral support structures on the stability of narrow coal pillars in gently inclined gob-side entries showed that without overlapping supports, internal stresses within the pillar distribute towards both sides, causing lateral expansion. Accordingly, this study proposed a bidirectional reinforcement mechanism and a novel support design method for narrow pillars. When bilateral support structures create an overlapping zone within the pillar, an interlocking anchorage region forms. An overlap exceeding 1 m effectively improves the stress distribution within the pillar, restricts the propagation and coalescence of cracks, and thereby enhances the pillar’s overall bearing capacity. This finding provides a new approach for designing narrow coal pillar support.

(3) For the gob-side entry driving project in the gently inclined coal seam of the studied mine, the roof and solid coal side were supported using a combination of “rock bolts + high pre-stressed cable bolts”. The pillar side employed full-height pre-stressed cable bolts. Coordinated with the support of the No. 7134 machine roadway, an interlocking anchorage zone was formed, achieving a 1.5 m overlap in situ. Field monitoring demonstrated that this support system effectively controlled surrounding rock deformation. Displacements of the roof and both sides were confined within engineering allowable limits, showing a reduction of nearly 90% compared to previous deformation levels, significantly improving entry stability. This successful practice provides a valuable technical reference for surrounding rock control in gob-side entry driving under similar geological conditions.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Zha, W. et al. Surrounding rock control of gob-side entry driving with narrow coal pillar and roadway side sealing technology in Yangliu coal Mine[J]. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 27 (5), 819–823 (2017).

Xu, X. et al. A new method of mining pressure control for roof cutting in advance working face[J]. Eng. Fail. Anal. 161, 108302 (2024).

Yang, G. et al. Experimental and numerical investigations of Goaf roof failure and bulking characteristics based on gob-side entry retaining by roof cutting[J]. Eng. Fail. Anal. 158, 108000 (2024).

Gang, Y. et al. Failure mechanism and bulking characteristic of Goaf roof in no-pillar mining by roof cutting technology[J]. Eng. Fail. Anal. 150, 107320 (2023).

Fulian, H. et al. Reasonable coal pillar width and surrounding rock control of Gob-Side entry driving in inclined Short-Distance coal Seams[J]. Appl. Sci. 13(11), 6578 (2023).

Xue, P. Y. Optimization of small coal pillar width and control measures in gob-side entry excavation of Thick coal seams[J]. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 23304–23304 (2024).

Chengshuai, W. & Huimiao, Y. Stability control of goaf-driven roadway surrounding rock under interchange remaining coal pillar in close distance coal seams[J]. Energy Sci. Eng. 12 (6), 2553–2567 (2024).

Meng, W. et al. A study on the reasonable width of narrow coal pillars in the section of hard primary roof hewing along the air excavation roadway[J]. Energy Sci. Eng. 12 (6), 2746–2765 (2024).

Wen, W. et al. Study on small coal pillar in gob-side entry driving and control technology of the surrounding rock in a high-stress roadway[J]. Front. Earth Sci. 10, 1020866 (2023).

He, F. et al. Reasonable coal pillar width and surrounding rock control of Gob-Side entry driving in inclined Short-Distance coal Seams[J]. Appl. Sci. 13(11), 6578 (2023).

Qing, M. et al. Monitoring and evaluation of disaster risk caused by linkage failure and instability of residual coal pillar and rock strata in multi-coal seam mining[J].Geohazard Mechanics. 1(4), 297–307 (2023).

Feng, L. & Zhipei, Z. Study on Optimization of Shallow Section Coal Pillar Width of Gently Inclined Medium-Thickness Coal Seam[J]. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 719(4), (2021).

Jiang, Z., Guo, W. & Xie, S. Coal pillar size determination and surrounding rock control for Gob-Side entry driving in deep soft coal Seams[J]. Processes. 11(8), 2331 (2023).

Houqiang, Y. et al. Stability control of deep coal roadway under the pressure relief effect of adjacent roadway with large deformation: A case Study[J]. Sustainability 13 (8), 4412–4412 (2021).

Mingzhong, W. et al. Control technology of Roof-Cutting and pressure relief for roadway excavation with strong mining small coal Pillar[J]. Sustainability 15 (3), 2046–2046 (2023).

Yang, L. et al. Deformation Characteristics and Countermeasures of Roadway Surrounding Rock in Gas- and Water-Rich Coal Seam[J].Rock Mechanics and Rock 58(6):1–16. (2025).

Hongbao, Z. et al. Static blasting roof cutting surrounding rock control technology for narrow coal pillar Gob-Side entry driving in Thick coal Seams[J]. Int. J. Geomech. 25(6), 04025083 (2025).

Dongdong, C., Zaisheng, J. & Shengrong, X. Mechanism and key parameters of stress load-off by innovative asymmetric hole-constructing on the two sides of deep roadway[J]. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol.. 10(1), 82 (2023).

Dongdong, C. et al. Evolution law and engineering application on main stress difference for a novel stress relief technology in two ribs on deep coal roadway[J]. J. Cent. South. Univ. 30 (7), 2266–2283 (2023).

Dongdong, C. et al. Study on the failure mechanism and a new monitoring method of borehole stress gauge monitoring coal seam mining stress[J]. Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 1–21 (2025).

Xiong, X. et al. Principal stress rotation effect and multi-factor coupling support optimization in roadways of inclined coal seams[J]. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 25628–25628 (2025).

Dai, L. et al. Quantitative principles of dynamic interaction between rock support and surrounding rock in rockburst roadways[J]. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 35 (1), 41–55 (2025).

Dai, L. et al. Microseismic criterion for dynamic risk assessment and warning of roadway rockburst induced by coal mine seismicity[J]. Engineering Geology. 357, 108324 (2025).

Xizhan, Y. et al. Stability and cementation of the surrounding rock in Roof-Cutting and Pressure-Relief entry under mining Influence[J]. Energies 15 (3), 951–951 (2022).

Liu, B., Chen, D. & Xu, C. Deep-hole blasting roof cutting technology for pressure relief in the final mining phase of the working face: a case study[J]. Front. Earth Sci. 13, 1566968 (2025).

Zheng, R. et al. Study on the ground pressure manifestation patterns of roof cutting and pressure Relief[J]. Appl. Sci. 15 (11), 6049–6049 (2025).

Lang, D. et al. Study of reasonable roof cutting parameters of Dense-Drilling roof cutting and pressure relief Self-Forming roadway in Non-Pillar Mining[J]. Appl. Sci. 15 (5), 2685–2685 (2025).

Dongyin, L. et al. Risk field assessment of Longwall working face by the double-sided roof cutting along the gob[J].Geohazard Mechanics. 1(4), 277–287 (2023).

Yang, T. et al. Research on the roof failure law of downward mining of gently inclined coal seams at close Range[J].Applied Sciences. 15(12), 6609 (2025).

Jia, C. et al. Simulation on instability behaviour of roadway surrounding rock under dynamic-static loading in Thick coal seam[J]. Eng. Fail. Anal. 182 (PB), 110066–110066 (2025).

Wenli, Z. et al. Roof cutting mechanism and surrounding rock control of small pillar along-gob roadway driving in super high coal seam[J]. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 82(4), 151 (2023).

You, H. & Liu, Z. Key parameters of the roof cutting and pressure relief technology in the Pre-Splitting blasting of a hard roof in Guqiao coal Mine[J]. Appl. Sci. 14 (24), 11779–11779 (2024).

Zhang, J. et al. Study on stress distribution law of surrounding rock of roadway under the Goaf and mechanism of pressure relief and impact reduction[J]. Eng. Fail. Anal. 160, 108210 (2024).

Guo, Y. & Yu, H. Research and application of roof cutting and pressure release technology of Retracement roadway in large height mining working Face[J]. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 39 (2), 1–10 (2020).

Wang, H. & Guo, J. Research on the deformation and failure mechanism of flexible formwork walls in Gob-Side-Entry retaining of Ultra-Long isolated mining faces and pressure Relief-Control technology via roof Cutting[J]. Appl. Sci. 15 (11), 5833–5833 (2025).

Jianning, L. et al. Effect of the roof cutting technique on the overlying geotechnical structure in coal mining[J]. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 82(8), 289 (2023).

Xuelong, L. et al. Corrigendum to rockburst mechanism in coal rock with structural surface and the microseismic (MS) and electromagnetic radiation (EMR) response. [Eng Fail. Anal. 124, 105523 (2021). 105396][J].Engineering Failure Analysis,2021,(prepublish).

Gang, Y. et al. Effect of Roof Cutting Technology on Broken Roof Rock Bulking and Abutment Stress Distribution: A Physical Model Test[J] 57, 3767–3785 (Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2024). 5.

ltasca Consulting Group, Inc. UDEC- Universal Distinct Element Code, Ver. 7.0 (ltasca, 2019).

Shangyuan, C. et al. Determination of key parameters of gob-side entry retaining by cutting roof and its application to a deep mine[J]. Rock. Soil. Mech. 40 (1), 332–342 (2019).

Funding

This research was supported with funding awarded from the National Natural Science Foundation of Chi-na (Grant No. 52004286, 52374149).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CRediT author statement D.C. and Z.Q.Z.: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. X.Y.: Investigation, Methodology, Software, Laboratory testing, Writing – original draft. W.Z.: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. X.J., Z.S., J.C., and Z.X.Z.: Data curation, Laboratory testing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.Conceptualization: Dongdong Chen; Zhenquan ZhangData curation: Wenkang Zhao; Xiaodong Jing; Zhenxing Shan; Jingchen Chang; Zhixuan ZhangFunding acquisition: Dongdong Chen; Zhenquan ZhangInvestigation: Dongdong Chen; Xiangyu YangMethodology: Xiangyu Yang; Wenkang ZhaoSoftware: Xiangyu Yang; Zhenquan ZhangSupervision:Dongdong Chen; Zhenquan Zhanglaboratory test: Xiangyu Yang; Xiaodong Jing; Zhenxing Shan; Wenkang ZhaoWriting – original draft: Xiangyu Yang; Wenkang ZhaoWriting – review & editing: Dongdong Chen; Zhenquan Zhang.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, D., Yang, X., Zhang, Z. et al. Mechanism and control of pillar bidirectional reinforcement during pre-cut roof gob-side entry driving in gently inclined coal seams. Sci Rep 16, 352 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29848-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29848-9