Abstract

The substantial peak electrical demand for space heating in cold and freezing climates poses a significant challenge to grid stability and energy affordability. This study proposes and numerically investigates a novel active thermal energy storage system integrated directly into a building brick to address this challenge. The system features an encapsulated Phase Change Material (PCM) composite, enhanced with a high-conductivity copper oxide foam, and is coupled with a low-wattage electrical heating element. This design enables the brick to function as a ‘thermal battery,’ charging with off-peak electricity and discharging heat during peak demand periods. A comprehensive computational fluid dynamics (CFD) model was developed to analyze the system’s performance under severe winter conditions, with ambient temperatures as low as − 30 °C and varying electrical power inputs. The results demonstrate a profound improvement in the indoor thermal environment. While an unheated brick’s surface dropped to − 5 °C, the active system maintained it above a stable + 8 °C, delivering a peak heat output of over 150 W/m² to the living space. This effective load shifting reduced the wall’s net daily energy loss by nearly 70%, significantly lessening the burden on the primary HVAC system during peak hours. The findings confirm that the proposed active PCM-brick is a highly effective and viable solution for peak-shaving, enhancing occupant comfort, and improving the energy resilience of buildings in cold climates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global imperative to decarbonize the energy sector has placed significant pressure on buildings, which account for approximately 40% of total energy consumption and over a third of energy-related CO₂ emissions worldwide1,2,3,4. In regions characterized by cold or freezing climates, the vast majority of this energy is dedicated to space heating, which often represents the single largest load on residential and commercial utility grids5,6,7. The reliance on conventional heating systems during peak demand periods—typically early mornings and evenings—imposes immense strain on electrical infrastructure, necessitating the use of inefficient and carbon-intensive “peaker” power plants and contributing to grid instability7,8,9. Furthermore, the increasing electrification of the heating sector, driven by the adoption of heat pumps and electric resistance heaters as alternatives to fossil fuels, is projected to exacerbate these peak-load challenges10,11,12. Consequently, developing innovative and intelligent building envelope technologies that can manage thermal energy more effectively is not merely an objective for enhancing comfort, but a critical strategy for improving grid stability, reducing energy costs, and facilitating a sustainable energy transition13,14,15.

A highly promising approach for addressing these challenges lies in the application of Thermal Energy Storage (TES) systems within the building fabric itself16,17,18,19,20,21. TES technologies enable the capture and storage of energy during periods of low demand or low cost (e.g., overnight) and its subsequent release during periods of high demand, a process known as load shifting or peak-shaving22,23,24,25. Among various TES methods, Latent Heat Thermal Energy Storage (LHTES) using Phase Change Materials (PCMs) has garnered significant research interest for building applications26,27,28,29. PCMs are substances that can absorb and release large quantities of thermal energy at a nearly constant temperature during their phase transition (typically solid-to-liquid and vice-versa). This characteristic offers a distinct advantage over sensible heat storage materials, providing a much higher energy storage density within a narrow temperature range, which is ideal for maintaining occupant comfort28,30,31,32,33. However, a major practical challenge associated with many PCMs, particularly organic variants, is their inherently low thermal conductivity. This property can severely limit the rate of heat transfer, leading to slow and inefficient charging and discharging cycles unless a thermal conductivity enhancer is integrated34,35,36.

The integration of PCMs into building envelopes has been extensively investigated as a passive strategy, primarily for cooling applications in moderate to hot climates37,38,39,40,41. Researchers have successfully incorporated PCMs into various building components, including wallboards42,43,44,45, concrete46,47,48, plaster, and by impregnating them into the cavities of hollow bricks49,50,51. In these passive systems, the PCM absorbs solar and ambient heat during the day to prevent overheating and releases it at night. While effective for reducing cooling loads, the applicability of such passive strategies in cold or freezing climates during the heating season is severely limited. In these environments, passive solar gains are often insufficient, unreliable, or ill-timed to fully “charge” (i.e., melt) the PCM, rendering the latent heat capacity of the material largely inaccessible when it is most needed43,52,53,54,55.

To unlock the full potential of PCMs for heating applications in cold regions, an active charging strategy is required. This involves coupling the PCM-integrated building component with a controllable energy source. Electrical resistance heating presents an ideal candidate for this purpose due to its simplicity, low capital cost, and perfect compatibility with off-peak electricity tariffs56,57,58,59. By integrating a low-wattage electrical heating element with a PCM-enhanced building envelope, it becomes possible to create a "thermal battery." During off-peak hours at night, when electricity is abundant and inexpensive, the heater can be activated to charge the PCM. This stored thermal energy can then be passively discharged throughout the subsequent day to meet the building’s heating requirements, thereby drastically reducing or even eliminating the need to draw expensive electricity from the grid during peak hours60,61,62,63,64,65. This concept of an electrically-charged thermal mass aligns perfectly with the goals of demand-side management and the development of grid-interactive efficient buildings66,67,68.

Despite the clear conceptual advantages, the design and implementation of an active, electrically-coupled PCM heating system within a standard building component like a brick presents unique and complex challenges69,70. The system must be designed to ensure uniform and efficient charging of the PCM, effective heat release to the indoor space, and long-term material stability, all while operating within a harsh freezing environment. While some studies have explored electrically-coupled PCM storage for underfloor heating or standalone storage units, research on a fully integrated, brick-based wall heating and storage system remains scarce.

This study, therefore, aims to address this critical research gap by proposing and numerically investigating a novel building component: a brick integrated with an encapsulated PCM and coupled with an electrical wall heating element, specifically designed for peak-load reduction in freezing climates. The novelty of this work lies in the synergistic combination of these technologies to create an active thermal battery within the building envelope itself. By using a comprehensive numerical model, this research will analyze the system’s dynamic thermal behavior, its effectiveness in shifting electrical loads, and its overall impact on reducing peak energy consumption. The findings are intended to provide fundamental insights and design guidelines for a new generation of smart building envelopes capable of actively interacting with the electrical grid, thereby enhancing energy resilience, reducing heating costs, and supporting the broader integration of renewable energy sources.

Methodology and numerical formulation

This section outlines the comprehensive framework established to simulate and analyze the proposed active thermal energy storage system. The discussion begins by defining the physical problem and its operational context, followed by the governing mathematical models and boundary conditions. The numerical simulations were performed using a proprietary in-house computational fluid dynamics (CFD) code, which has been developed based on the Finite Volume Method (FVM). The solver is specifically engineered to handle the complex physics of the current problem, including conjugate heat transfer and solid–liquid phase transitions via the enthalpy-porosity formulation. The fidelity of this in-house code is demonstrated through a rigorous validation study presented in "Validation study" section. Finally, it details the rigorous verification and validation procedures undertaken to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the numerical results.

Problem description

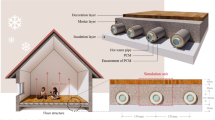

This study addresses the critical challenge of high peak electrical demand for space heating in buildings situated in cold and freezing climates. The proposed solution is a novel “thermal battery” brick, an active building envelope component designed specifically for electrical load shifting. The physical system consists of a standard clay brick integrated with a central 4 cm × 4 cm square enclosure (Fig. 1). This cavity houses a composite material comprising Pentadecane, a low-temperature Phase Change Material (PCM), and a high-conductivity Copper Oxide Foam (COF). The COF is characterized by a high porosity of 0.95 and a fine pore diameter of 0.1 mm, serving not only as a structural matrix but, more critically, as a thermal conductivity enhancer to accelerate the otherwise slow thermal response of the organic PCM. The selection of Pentadecane as the PCM is critical and was based on its thermophysical properties, particularly its melting temperature (Tm) of 10 °C and narrow melting temperature range (Tmr) of 1 °C. The melting temperature was strategically chosen to strike a balance between efficient charging and effective heat discharge. A melting point of 10 °C allows the PCM to act as an effective thermal buffer, releasing stored latent heat to maintain the indoor brick surface at a stable and comfortable temperature (e.g., above 8 °C, as shown in our results) even when the external temperature is well below freezing. This temperature is sufficiently high to provide useful radiant heat to the indoor environment (maintained at 20 °C) but low enough to be fully and efficiently charged using a low-power heating element during off-peak periods. Furthermore, the narrow melting range is highly desirable as it ensures that the phase transition occurs at a near-constant temperature, providing stable and predictable thermal regulation, which is essential for both occupant comfort and reliable peak-shaving performance

.

It is important to note the strategic placement of the electrical heating element on the indoor surface of the brick rather than in direct contact with the PCM. This configuration was chosen for three primary reasons. First, it provides a crucial dual function: during the off-peak charging period at night, the heat that is not immediately absorbed by the brick provides useful baseline heating to the indoor space, fulfilling the building’s simultaneous heating demand. Second, the brick material acts as a thermal diffuser, promoting more uniform heating of the PCM core and preventing localized overheating and potential degradation of the PCM. Finally, this surface-mounted design is significantly simpler and more cost-effective from a manufacturing and long-term durability perspective compared to embedding a heater within the sealed PCM composite.

The central innovation of this system is the integration of a low-wattage electrical heating element, which provides a uniform power output (P). To assess the system’s robustness and performance under realistic and challenging conditions, this study parametrically investigates the effect of varying this power input. The operational strategy is to leverage this heater to actively charge the PCM by melting it and storing latent heat during off-peak electricity periods, typically overnight. This stored thermal energy is then passively discharged into the indoor space during the subsequent peak demand hours. This process is designed to maintain indoor thermal comfort while substantially reducing or eliminating the need to draw expensive power from the grid.

Mathematical formulation

To capture the complex physics of the system, which involves conjugate heat transfer, buoyancy-driven fluid flow, and solid–liquid phase transition, a robust mathematical model is essential. The formulation is based on the well-established framework presented by Nassr et al. (2025), which has been successfully applied to similar PCM systems. The accuracy of the simulation is fundamentally dependent on the thermophysical properties (TPP) of the constituent materials, which are detailed in Table 1.

The fluid flow of the molten Pentadecane is modeled as incompressible, requiring the satisfaction of the continuity equation to ensure mass conservation within any given control volume49.

Momentum transport within the liquid PCM is described by the Navier–Stokes equations (Eqs. 2–4). A key feature of this model is the inclusion of the Boussinesq approximation, (ρβ)ₚcₘ(T – Tₘ)g, which accounts for the natural convection currents driven by temperature-induced density gradients. To elegantly handle the solid–liquid phase transition without explicitly tracking the interface, the enthalpy-porosity formulation is employed. This technique introduces a momentum sink term that is a function of the liquid fraction (λ), effectively immobilizing the fluid in solid regions while having no effect in fully liquid regions49.

Heat transfer throughout the system is governed by a set of energy equations. For the complex PCM region where both convection and phase change occur, a single enthalpy-based energy equation is used (Eq. 5), which inherently accounts for both sensible and latent heat effects. In the solid domains of the brick and COF, this formulation simplifies to the standard transient heat conduction equation49.

To track the progress of the phase transition, a liquid fraction parameter, λ, is defined. A smooth error function (erf) is chosen to describe this transition (Eq. 8), as it provides a numerically stable and physically representative progression from solid (λ = 0) to liquid (λ = 1) over the defined melting temperature range (Tmr)49.

Boundary and initial conditions

To solve the governing equations, a set of well-defined boundary conditions that reflect the system’s real-world operating environment is required. The indoor surface of the brick, exposed to the conditioned living space, is modeled with a convective boundary condition where the temperature is maintained at Tindoor = 20 °C via a heat transfer coefficient of hindoor = 20 W/m K. The outdoor surface is subjected to dynamic winter conditions. To model this, the 24-h ambient temperature profile was simulated as a sinusoidal function with a daily mean temperature set to Tmin + 5 °C and an amplitude of 5 °C, ensuring the temperature cycle reaches the prescribed minimum (Tmin) during the early morning hours. The minimum ambient temperatures Tmin tested in this study range down to an extreme of -30 °C; these scenarios were intentionally chosen not to represent a single specific city, but to conduct a parametric stress-test of the technology’s effectiveness and operational limits under a wide variety of demanding cold climate conditions. The heat transfer to the outdoor environment is governed by a combined convective and radiative heat transfer coefficient of hos = 25 W/m2 K. This surface is also exposed to active thermal loads with a defined daily schedule: daytime solar radiation of q′′ = 700 W/m2 is applied for 8 h (from t = 08:00 to t = 16:00), and the integrated heating element is activated during a prescribed 8-h off-peak charging period at night (from t = 22:00 to t = 06:00). The power input (P) for the heating element is parametrically analyzed at 0, 100, 200, and 300 W/m2. To accurately represent the thermal behavior of a single brick within an extensive wall assembly, the top, bottom, and side faces of the brick are treated as adiabatic (zero-gradient) boundaries. The simulation for each case begins with the entire domain at a uniform initial temperature corresponding to the ambient condition at t = 0.

Mesh and time-step independence

Ensuring the numerical results are free from discretization errors is a critical step in model verification. To this end, rigorous independence studies were conducted for a representative case (Tₘᵢₙ = − 20 °C). The simulation was performed with progressively finer meshes and smaller time-steps, with the peak heating power saved during the discharge cycle serving as the key monitoring variable. The results of this analysis, presented in Table 2 and Table 3, indicate that a computational mesh of approximately 410,000 cells and a time-step of 5 s provide a convergent solution. Since further refinement of either the mesh or the time-step yielded negligible changes in the outcome (< 0.2%), these settings were adopted for all subsequent simulations to ensure an optimal balance of numerical accuracy and computational efficiency.

Validation study

To benchmark the performance of the in-house numerical solver and ensure its fidelity, a validation study was conducted against the established findings of Alawadhi (2008)3. For this comparative analysis, a specific configuration from the reference paper was meticulously recreated, focusing on the case where the PCM-filled cylinders were positioned nearer the interior environment (Hc = H/3). The temporal profile of the indoor surface heat flux, as predicted by our simulation, is plotted alongside the reference data in Fig. 2. A high degree of congruence is observed between the two curves throughout the daily cycle, with a mean quantitative discrepancy of approximately 5%. This successful benchmark lends significant credibility to the simulation framework’s ability to accurately capture the complex thermal dynamics of PCM-integrated building components and substantiates the validity of the results presented in this work.

Result of validation study3.

Performance metrics

To quantify the overall daily energy impact of the active brick on the building’s heating load, the Daily Peak Demand Contribution (Pdc) was calculated. This metric represents the net thermal energy per unit area that the primary HVAC system must supply over a 24-h period to compensate for the heat transfer through the brick wall. It is calculated by numerically integrating the instantaneous indoor surface heat flux (q′′is) over a full 24-h cycle (T = 86,400 s), as shown in the equation below:

Here, q′′is is given in W/m2. The negative sign is applied so that a net heat loss from the indoor space over the day (a negative integral) results in a positive Pdc value, which intuitively represents a required energy input. The constant factor of 1/3,600,000 is used to convert the final result from Joules/m2 to the more conventional unit of kWh/m2.

Results and discussion

This section presents a detailed analysis of the numerical simulation results. The discussion is structured to evaluate the performance of the active PCM-brick system by first examining its direct impact on the indoor thermal environment, followed by an analysis of the energy dynamics at the building envelope, and concluding with a visualization of the internal heat storage mechanism.

Indoor thermal environment and comfort

The primary function of the proposed active brick is to transform a typically cold exterior wall into a stable, warm surface, thereby enhancing occupant comfort and providing useful heat. The impact of the integrated heating system on this critical metric is illustrated in Fig. 3, which displays the temporal variation of the indoor surface temperature (Tis) over a 24-h cycle for four different freezing conditions.

In the baseline case with no heating (P = 0 W/m2), the brick acts as a significant thermal liability. As the outdoor temperature drops, the indoor surface temperature plummets, falling well below a comfortable level. For instance, in the Tₘᵢₙ = − 20 °C scenario (Fig. 3c), the unheated wall’s surface temperature drops to a minimum of approximately − 5 °C, creating an extremely cold radiant surface that would drastically increase the building’s overall heating load and cause significant occupant discomfort.

The application of electrical heating fundamentally alters this behavior. Even a modest power input of 100 W begins to stabilize the temperature, while higher powers (200 W/m2 and 300 W/m2) transform the wall into an effective low-temperature radiant heating panel. Quantitatively, for the Tₘᵢₙ = − 20 °C case, applying 200 W/m2 of power elevates the minimum indoor surface temperature from − 5 °C to a much more manageable + 5 °C. At 300 W/m2, the temperature is maintained above 8 °C throughout the entire day. A crucial qualitative observation is the flattening of the temperature profile at higher power inputs. This stabilization is a direct result of the Phase Change Material’s activation. The electrical energy input during the off-peak charging period is absorbed as latent heat by the melting Pentadecane. This stored energy is then released as the PCM solidifies, creating a thermal buffer that dampens the effect of the fluctuating outdoor temperature and provides a more consistent heat output to the room.

Peak load reduction and heat flux dynamics

The effectiveness of the system in shifting electrical loads is best understood by analyzing the heat flux at the indoor surface (q′′ᵢₛ), as shown in Fig. 4. Here, positive values represent a heat gain for the indoor space (the wall is heating the room), while negative values indicate heat loss.

The P = 0 W/m2 case again serves as the benchmark, demonstrating a continuous and significant heat loss from the building. At Tₘᵢₙ = − 20 °C (Fig. 4c), the peak heat loss reaches nearly -50 W/m2, representing a constant drain on the building’s primary heating system. When the integrated heater is activated, the direction of the heat flux is reversed. The wall transitions from an energy sink to an energy source. The stored thermal energy is discharged into the room, particularly during the coldest hours of the day.

This behavior is the core of the peak-shaving functionality. For the Tₘᵢₙ = − 20 °C case, the 300 W/m2 system delivers a peak heat output of over 150 W/m2 to the indoor space. This is thermal energy that was generated and stored using off-peak electricity, and is now being delivered during a time that would typically coincide with the building’s peak heating demand. By providing this supplemental heat, the active brick directly reduces the load that must be met by the primary, peak-hour heating system. The sinusoidal shape of the heat output is a result of the dynamic balance between the stored energy being released and the continuous heat loss to the freezing outdoor environment. As the outdoor temperature reaches its minimum (typically in the early morning), the temperature gradient across the brick increases, driving a higher rate of heat discharge to the indoor space.

Impact on daily energy demand

To quantify the overall effectiveness of the system, the net daily energy impact is considered. Figure 5 presents the daily peak demand contribution (Pdc), which represents the net heat loss from the wall that must be compensated by the primary HVAC system over a 24-h period.

The results clearly show that as the outdoor environment becomes colder, the net daily heat loss for the unheated brick (P = 0 W) increases significantly, from approximately 1.2 kWh/m2 at Tmin= 0 °C to over 2.0 kWh/m2 at Tₘᵢₙ = − 30 °C. The application of the integrated heating system systematically reduces this net loss. This metric effectively demonstrates how much of the wall’s inherent heat loss is offset by the stored and discharged energy. For instance, at Tₘᵢₙ = − 20 °C, applying 300 W/m2 of heating power reduces the daily compensatory energy requirement from around 1.6 kWh/m2 to just 0.5 kWh/m2. This represents a reduction of nearly 70% in the energy that the primary heating system must supply to overcome the thermal losses through this section of the building envelope.

An important and counter-intuitive trend is observable in Fig. 5 for the higher heating power inputs (P = 200 and 300 W/m2), where the net daily heat loss (Pdc) is lower for the Tmin = − 20 °C scenario than for Tmin = − 10 °C. This phenomenon highlights an operational “sweet spot” for the thermal battery. At − 10 °C, the outdoor temperature is not cold enough to drive a complete discharge of the PCM’s stored latent heat during the day, meaning some of the stored off-peak energy goes unused. In contrast, the Tmin = − 20 °C condition provides a sufficient thermal gradient to force a more complete daily discharge cycle, maximizing the effective use of the stored energy to offset daytime heat loss. However, at the extreme Tmin = − 30 °C condition, the overall heat loss through the envelope becomes too great, overwhelming the system’s storage capacity and causing the Pdc to increase once more.

Internal thermal storage visualization

To provide a deeper physical insight into the heat storage and transfer mechanisms, Fig. 6 displays the temperature distribution contours within the brick’s cross-section at various times for the Tₘᵢₙ = − 10 °C scenario.

Temperature distribution contours within the PCM-brick for the Tₘᵢₙ = − 10 °C scenario. The left column shows the unheated case (P = 0 W/m2), while the right column shows the heated case (P = 200 W/m2) at corresponding times of day (from top to bottom: early charging, peak charge, and discharging phase).

The contours for the unheated brick (left column) reveal a steep and persistent thermal gradient, with the interior of the brick remaining significantly cold throughout the day. The PCM in this scenario remains permanently frozen and inert. In stark contrast, the heated brick (right column) demonstrates the formation of a warm thermal core. During the charging phase (top right), the heat from the electrical element is absorbed, raising the temperature of the PCM core above its 10 °C melting point, as indicated by the yellow and red regions. This is the stored latent and sensible heat. This thermal storage can be quantified using the temperature data from the “peak charge” phase in Fig. 6 (right column, second from top) and the properties in Table 1. In this state, the PCM core reaches temperatures of approximately 18 °C. The total energy stored per kilogram of Pentadecane can be broken down into three stages. First, initial sensible heat is absorbed as the solid PCM heats from the sub-zero ambient conditions to its melting range around 10 °C. Second, a substantial amount of latent heat—208,000 J/kg—is absorbed during the phase change. Finally, additional sensible heat is stored as the liquid PCM is heated from approximately 10 °C to a peak of 18 °C. Based on a specific heat capacity of 2070 J/kg K, this final sensible heat gain alone accounts for over 16,500 J/kg (2070 J/kg K × 8 K). This quantification clearly shows that the latent heat component is overwhelmingly dominant, representing the bulk of the brick’s “thermal battery” capacity and confirming the critical role of the phase change process in the system’s effectiveness.

During the discharge phase (bottom right), this warm core persists even as the outer layers of the brick cool down. This stored energy creates a thermal gradient that drives heat flow both inward toward the room and outward toward the freezing exterior. The relatively uniform temperature distribution within the PCM enclosure is direct visual evidence of the Copper Oxide Foam’s critical role. Without this high-conductivity foam matrix, the poor thermal conductivity of the PCM would lead to significant temperature gradients, localized overheating near the heating element, and incomplete melting of the PCM volume. The COF effectively creates a thermal scaffold, ensuring that heat is distributed rapidly and evenly, which is essential for both efficient charging and preventing material degradation. These visualizations confirm that the active system successfully creates a high-inertia thermal core, enabling the brick to function as a controllable thermal battery.

Conclusion

This study numerically investigated a novel brick integrated with a Phase Change Material and an electrical heating element, designed to function as an active thermal battery for buildings in freezing climates. The research successfully demonstrated that the proposed system can transform a thermally inefficient building envelope into a valuable energy storage and radiant heating component. The findings confirm that without intervention, the brick’s indoor surface can fall to temperatures as low as − 5 °C, creating significant thermal discomfort and a high heating load. By activating the integrated heater, the system fundamentally changes the wall’s role from a thermal liability to an active thermal barrier. It not only prevents heat loss but also provides supplemental heat to the indoor space. By maintaining the indoor surface temperature above 8 °C, even when the ambient temperature is − 20 °C, the system significantly improves the indoor radiant environment by eliminating an extremely cold surface and directly reduces the load on the primary HVAC system.

Quantitatively, the system’s ability to shift electrical loads was profound. By storing off-peak energy, the active brick delivered a peak heat output of over 150 W/m2 during critical daytime hours, directly offsetting the demand on the primary HVAC system. his resulted in a reduction of the wall’s net daily energy loss by nearly 70%. Qualitatively, the visualizations confirmed that the integrated high-conductivity Copper Oxide Foam was essential to the system’s success, ensuring uniform heat distribution for efficient charging and facilitating a stable heat discharge by overcoming the inherent low thermal conductivity of the PCM. The latent heat capacity of the PCM was crucial in stabilizing the heat discharge, providing a more consistent and comfortable radiant warmth compared to a simple heating element alone. In conclusion, this active brick system presents a highly effective and viable solution for enhancing energy resilience, improving occupant comfort, and significantly reducing peak heating demand in cold regions.

For future work, the most critical next step is the experimental validation of these numerical results through the fabrication and testing of a physical prototype. Further research should also focus on optimizing the charging and discharging cycles through advanced control strategies and integrating the model into whole-building energy simulations to assess its annual performance and grid-level impact.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CFD:

-

Computational fluid dynamics

- COF:

-

Copper oxide foam

- FVM:

-

Finite volume method

- PCM:

-

Phase change material

- PCM-B:

-

Phase change material-brick

- Pdc:

-

Daily peak demand contribution

- TPP:

-

Thermophysical properties

- A:

-

Area (m2)

- Cp :

-

Specific heat capacity at constant pressure (J/kg K)

- dp :

-

Pore diameter of foam (m)

- g:

-

Gravitational acceleration vector (m/s2)

- h:

-

Convective heat transfer coefficient (W/m2 K)

- h:

-

Latent heat of fusion (J/kg)

- k:

-

Thermal conductivity (W/m K)

- K:

-

Permeability of porous medium (mÂ2)

- P :

-

Pressure (Pa)

- p:

-

Integrated heating power per unit area

- q′′:

-

Heat flux (W/mÂ2)

- S:

-

Momentum sink term (kg/m2 s)

- t:

-

Time (s)

- T:

-

Temperature (K or °C)

- V :

-

Velocity vector (m/s)

- \(\alpha\) :

-

Solar absorptivity (–)

- \(\beta\) :

-

Thermal expansion coefficient (1/K)

- \(\Delta\) :

-

Difference or change (–)

- \(\varepsilon\) :

-

Porosity of foam (–)

- Ɛ:

-

Surface emissivity (–)

- \(\lambda\) :

-

Liquid fraction (–)

- \(\mu\) :

-

Dynamic viscosity (Pa s)

- \(\rho\) :

-

Density (kg/m3)

- \(\sigma\) :

-

Stefan-Boltzmann constant (\(5.6 \times 10^{ - 8} \,{\text{W}}/{\text{m}}^{2} \;{\text{K}}^{{4}}\))

- af:

-

Stainless steel foam

- b:

-

Brick

- d:

-

Daily

- cof:

-

Copper oxide foam

- i:

-

Indoor

- is:

-

Indoor surface

- m:

-

Melting

- max:

-

Maximum

- min:

-

Minimum

- mr:

-

Melting range

- o:

-

Outdoor

- os:

-

Outdoor surface

- pcm:

-

Phase change material

- sky:

-

Sky

- sun:

-

Solar

References

Eraza, N. et al. Vertically perforated fired clay bricks: thermal characterization and numerical analysis. J. Adv. Res. Numer. Heat Transf. 35, 25–53 (2025).

Collet, F., Serres, L., Miriel, J. & Bart, M. Study of thermal behaviour of clay wall facing south. Build. Environ. 41(3), 307–315 (2006).

Alawadhi, E. M. Thermal analysis of a building brick containing phase change material. Energy Build. 40(3), 351–357 (2008).

Kočí, V., Bažantová, Z. & Černý, R. Computational analysis of thermal performance of a passive family house built of hollow clay bricks. Energy Build. 76, 211–218 (2014).

Aouba, L., Coutand, M., Perrin, B. & Lemercier, H. Predicting thermal performance of fired clay bricks lightened by adding organic matter: Improvement of brick geometry. J. Build. Phys. 38(6), 531–547 (2015).

Nardi, I. et al. Modeling and optimization of the thermal performance of a wood-cement block in a low-energy house construction. Energies 9(9), 677 (2016).

Ramakrishnan, S., Wang, X., Sanjayan, J. & Wilson, J. Thermal performance assessment of phase change material integrated cementitious composites in buildings: Experimental and numerical approach. Appl. Energy 207, 654–664 (2017).

Al-Awsh, W. A. Y. Experimental Assessment and Numerical Validation of the Thermal Performance of Concrete Walls (King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals, Saudi Arabia, 2019).

Su, H., Wu, D., Shen, M., Chen, W. & Wang, S. Development and performance test including mechanical and thermal of new tenon composite block masonry walls. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019(1), 5253946 (2019).

Sassine, E., Cherif, Y., Dgheim, J. & Antczak, E. Investigation of the mechanical and thermal performances of concrete hollow blocks. SN Appl. Sci. 2, 1–17 (2020).

Younsi, Z. & Naji, H. Numerical simulation and thermal performance of hybrid brick walls embedding a phase change material for passive building applications. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 140(3), 965–978 (2020).

Charai, M. et al. Thermal performance and characterization of a sawdust-clay composite material. Procedia Manuf. 46, 690–697 (2020).

Selvaraj, S. & Kesavaperumal, T. Numerical investigation of optimal wall materials for effective thermal performance in warm and hot climatic regions. Open House Int. 46(2), 325–338 (2021).

Al-Rukaibawi, L. S., Szalay, Z. & Károlyi, G. Numerical simulation of the effect of bamboo composite building envelope on summer overheating problem. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 28, 101516 (2021).

Gencel, O. et al. Thermal performance optimization of lightweight concrete/EPS layered composite building blocks. Int. J. Thermophys. 42, 1–14 (2021).

Motlagh, S. Y., Golab, E. & Sadr, A. N. Two-phase modeling of the free convection of nanofluid inside the inclined porous semi-annulus enclosure. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 164, 105183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2019.105183 (2019).

Goudarzi, S. et al. Nanoparticles migration due to thermophoresis and Brownian motion and its impact on Ag-MgO/Water hybrid nanofluid natural convection. Powder Technol. 375, 493–503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2020.07.115 (2020).

Golab, E. et al. Investigation of the effect of adding nano-encapsulated phase change material to water in natural convection inside a rectangular cavity. J. Energy Storage 40, 102699 (2021).

Vahedi, B., Golab, E., Sadr, A. N. & Vafai, K. Thermal, thermodynamic and exergoeconomic investigation of a parabolic trough collector utilizing nanofluids. Appl. Therm. Eng. 206, 118117 (2022).

Golab, E., Vahedi, B., Jain, A., Taylor, R. A. & Vafai, K. Laminar forced convection in a tube with a nano-encapsulated phase change materials: minimizing exergy losses and maximizing the heat transfer rate. J. Energy Storage 65, 107233 (2023).

Goghari, A. S., Ghofrani, I., Yazdi, M. A., Golab, E. & Moosavi, A. Experimental study and economic analysis of a novel humidification-dehumidification system with a two-stage bubble column humidifier and packed bed dehumidifier for high-saline water desalination. Energy Convers. Manag. 343, 120255 (2025).

Lu, L., Zhang, T., Ren, Q. & Wang, Q. Eccentric compressive performance of circular steel slag concrete-filled steel tube stub columns. Adv. Struct. Eng. 28(9), 1575–1590 (2025).

He, X. et al. Controllable wetting characteristics of hierarchically structured surfaces. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 702, 138961 (2025).

Li, T. et al. Tensile and flexural behavior of polyvinyl alcohol engineered cementitious composites using steel slag aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 487, 142047 (2025).

Wang, B. et al. Axial compression properties of reinforced concrete columns strengthened with textile-reinforced ultra-high toughness cementitious composite in chloride environment. J. Build. Eng. 111, 113116 (2025).

Liu, D., Liang, J. & Wang, Y. Numerical simulation on anti-freezing performance of PCM-Clay in core wall during winter construction. Appl. Therm. Eng. 215, 118951 (2022).

Alfarawi, S., Omar, H., El-Sawi, A. & Al Jubori, A. Thermal performance assessment of external wall construction for energy-efficient buildings. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. Res. 6(3), em0189 (2022).

Hamdaoui, S. et al. Building hollow clay bricks embedding phase change material: Thermal behavior analysis under hot climate. Sol. Energy 237, 122–134 (2022).

Ouakarrouch, M., Laaroussi, N., Garoum, M. & Hajji, A. Thermal performances assessment and improvement of hollow concrete blocks commonly used in Morocco: Experimental and numerical approach. J. Therm. Sci. Eng. Appl. 14(10), 101005 (2022).

Lamrani, M. et al. Thermal and mechanical characterization of composite building material based on clay and date palm fibers. in Plant Fibers, their Composites, and Applications 305–322 (Elsevier, 2022).

Lamrani, M., Lkouen, A., Laaroussi, N. & Ouakarrouch, M. Thermal behaviour assessment of a new local clay-based building material and peanut shell waste: experimental and numerical approaches. Civ. Eng. Arch. 11, 3451–3470 (2023).

Li, Q. et al. Fabrication and numerical simulation of concrete block containing attapulgite-based composite phase change material. Constr. Build. Mater. 426, 136160 (2024).

Bajji, S., Bahammou, Y., Bellaziz, Y., Saba, A. & Naimi, Y. Thermo-physical characterizations and simulation study of an energy-efficient building material: Clay stabilized by wood ashes or crushed waste from traditional pottery. Heat Mass Transf. 60(6), 915–929 (2024).

Ahmed, M. I., Zafar, A., Alturki, R. & Khan, M. I. Optimization and performance of expanded polystyrene concrete for sustainable infill wall construction using response surface methodology. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 21032 (2025).

Alturki, R. Impact of manufactured waste sand on the compressive strength of concrete. J. North Basic Appl. Sci. 10(1), 29–40 (2025).

Alturki, R. Investigating the effects of aggregate gradations on the compressive strength and the cost of concrete using two proportioning methods. J. Mater. Eng. Struct. JMES 11(2), 193–208 (2024).

Rathore, P. K. S., Patel, B., Gupta, M. K., Sikarwar, B. S. & Sharma, R. K. Experimental analysis of thermal energy efficient clay brick incorporated with phase change material and insulation. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 190, 529–541 (2024).

Caruso, L., Buhagiar, V., Larcher, M., Borg, S. P. & Bottino-Leone, D. Validation of 3D thermal simulations of the Double C Block, a novel composite masonry unit, using in-situ U-value measurements. Energy Build. 325, 114956 (2024).

Lachheb, M., Younsi, Z., Youssef, N. & Bouadila, S. Enhancing building energy efficiency and thermal performance with PCM-Integrated brick walls: A comprehensive review. Build. Environ. 256, 111476 (2024).

Nath, B., Roy, S., Das, B. & Ehyaei, M. A. Experimental and numerical study of a novel composite building wall U-value. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 53, 102751 (2024).

Shuai, L., Zhang, J., Song, J., Chi, D. & Chen, Z. Numerical thermal assessment and theoretical analysis of horizontal-hole interlock composite insulation blocks. Heliyon 10(4), e26490 (2024).

Dora, S., Kuznik, F. & Mini, K. M. A novel PCM-based foam concrete for heat transfer in buildings-Experimental developments and simulation modelling. J. Energy Storage 105, 114625 (2025).

Hassan, R., Ali, A. B. M., Al-Khatib, O. & Mahariq, I. Incorporation of nano-encapsulated PCM in clay hollow blocks and cement layer for improving energy efficiency in buildings: A numerical approach. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 73, 106526 (2025).

Heniegal, A. M., Frahat, N. B., Elsied, M. M. & Agwa, I. S. Innovative technique for sustainable lightweight cement bricks incorporating popcorn coarse aggregate and PCM: Optimization of thermal, mechanical, and physical properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 493, 143262 (2025).

Huang, Y., Alekhin, V. N., Hu, W. & Pu, J. Adaptability analysis of hollow bricks with phase-change materials considering thermal performance and cold climate. Buildings 15(4), 590 (2025).

Kamel, J. A., Elsabbagh, A. M. M. & Mina, E. M. Enhancing building thermal performance using active PCM walls with regenerative water flow. Energy Build. 347, 116334 (2025).

Chabi, E., Amadji, T. A., Ahlinhan, M. F., Nazirou, I. & Adjovi, E. C. Numerical modeling and simulation of the mechanical behavior of self-locking blocks made from rice huskplastic composite material. J. Appl. Eng. Sci. 15(1), 69–76 (2025).

Rashid, F. L. et al. Latest progress in utilizing phase change materials in bricks for energy storage and discharge in residential structures. Energy Build. 330, 115327 (2025).

Nassr, A. A., Bousrih, J., Tursunzoda, F., Alshammari, F. & Al-Khatib, O. Smart bricks with phase change material capsules for green buildings: A numerical simulation alongside with techno-thermo-economic evaluation. Int. J. Energy Res. 2025(1), 9920262 (2025).

Kabeel, A. E., Attia, M. E. H., Benhmidene, A., Elazab, M. A. & Bady, M. Environmental and exergetic impacts of PCM-filled red bricks in conical solar water distillers. Int. J. Thermophys. 46(7), 94 (2025).

Daniel, J. Evaluation of the performance of different micro-PCMs in cement brick cavities for passive cooling applications. J. Build. Eng. 105, 112502 (2025).

Ahmed, Z. A. J., Ali, A. B. M., Al-Khatib, O. & Mahariq, I. Numerical investigation of passive cooling enhancement using nano-encapsulated phase change materials in electronic thermal management systems. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 65, 103965 (2025).

Hussien, S. A., Ali, A. B. M., Rahmani, Y. & Mahariq, I. Thermal Management System of LED headlights Based on the Active Cooling System of Water and Nano-encapsulated Phase Change Material. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 74, 107011 (2025).

Ahmed, Z., Ali, A. B. M., AlKhatib, O. J. & Mahariq, I. Melting behavior in a finned PCM solar thermal receiver/storage unit: a numerical study of heat load and orientation effects. Energy Rep. 14, 2927–2938 (2025).

Hussien, S. A., Ali, A. B. M., Alkhatib, O. J. & Mahariq, I. Enhanced passive thermal management of lithium-ion batteries with conical cylindrical chamber incorporating various phase change materials. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 35675 (2025).

Zehouani, Z. A., Nehari, T., Bounif, A. & Hadjadj, M. Innovative thermal optimization of hollow clay bricks with PCM integration for sustainable building solutions. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 65, 103921 (2025).

Akdağ, A. E., Koru, M. & Davraz, M. Numerical and experimental determination of thermal insulation performance of a composite block with different insulation materials. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 150, 1–14 (2025).

Saliby, A., & Kovács, B. Combining aesthetics and efficiency: PCM applications in Flemish bond walls. Pollack Periodica (2025).

Iachachene, F., Cheradi, H., Mougari, N. E., Kabache, M. & Dalkilic, A. S. Prediction of best PCM combinations used in bricks based on their performance for the improvement of thermal performance in energy-efficient building designs by multi-criteria decision. J. Energy Storage 120, 116474 (2025).

Shirani, N., Toghraie, D. & Rostami, S. Comparative study of mixed convection heat transfer of water–Cu nanofluid in an enclosure having multiple rotating circular cylinders with different configurations and considering harmonic cylinders rotation. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-020-09624-9 (2020).

Shirani, N., Toghraie, D., Zarringhalam, M. & Afrand, M. Numerical simulation of transient mixed convection of water–Cu nanofluid in a square cavity with multiple rotating cylinders having harmonic motion. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-020-09379-3 (2020).

Shirani, N. & Toghraie, D. Numerical investigation of transient mixed convection of nanofluid in a cavity with non-Darcy porous inner block and rotating cylinders with harmonic motion. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 17281. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-96733-6 (2021).

Kalateh, M. R. et al. Numerical study on heat transfer enhancement characteristics of tube inserted with centrally hollow narrow twisted tapes. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 57(3–5), 100720. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-020-09624-9 (2021).

Zhao, L. et al. Offering a channel for cooling three lithium-ion battery packs with water/Cu nanofluid: An exergoeconomic analysis. Ain Shams Eng. J. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2024.102788 (2024).

Tian, G. et al. Entropy analysis and mixed convection of nanofluid flow in a pillow plate heat exchanger in the presence of porous medium. Alexandria Eng. J. 82, 541–556 (2023).

Brahimi, M. E. et al. Investigation of the thermal efficiency of hollow bricks filled with bio-organic phase change material mixture. J. Energy Storage 122, 116667 (2025).

Salman, R., Aljabair, S. & Jalil, J. M. Enhancing thermal performance and energy efficiency in concrete bricks with phase change materials: A numerical study. J. Energy Storage 125, 116937 (2025).

Nagaraju, D., Mendu, S. S. & Chinta, N. D. Impact of PCM Enclosure Shape on the Performance of TES for Passive Building Envelope Design. Energy Storage 7(4), e70192 (2025).

Vighnesh, R., Parol, V. & Anand, K. B. Optimized parameters for novel shape stabilized PCM into porous vermiculite integrated in concrete roofings–A sustainable approach. Constr. Build. Mater. 490, 142566 (2025).

Gong, P., Wang, L., Lu, J., Liu, F. & Guo, P. Bentonite-based porous ceramic phase change bricks for thermal storage and fireproof protection in buildings. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 295, 113937 (2026).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) for funding this research work (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2503).

Funding

This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2503).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Riyadh Alturki: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Funding Acquisition, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & EditingAli B. M. Ali: Conceptualization, Software, Investigation, Validation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & EditingOmar J. Alkhatib: Formal Analysis, Resources, Methodology, Supervision, Project Administration, Investigation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & EditingIbrahim Mahariq: Resources, Data Curation, Supervision, Project Administration, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alturki, R., Ali, A.B.M., Alkhatib, O.J. et al. A numerical framework for an electrically-charged PCM brick to reduce winter peak heating demand. Sci Rep 16, 378 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29854-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29854-x