Abstract

Traditional teaching evaluation methods are often retrospective and coarse-grained, lacking the continuous, moment-to-moment feedback required for real-time pedagogical adaptation in language training. Existing intelligent tutoring systems frequently fail to address this, underutilizing multimodal behavioral signals and leaving a critical gap in understanding whether such signals are essential for learning effective policies. This paper introduces a Reinforcement Learning (RL) framework to solve this problem. We propose a hybrid cognitive-linguistic model using a Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) actor-critic agent, which operates on a novel 516-dimensional state vector that fuses a 512-dimensional semantic embedding from a pre-trained T5 model with a 4-dimensional vector of simulated cognitive-behavioral signals (correctness, response time, attention, hint request). Tested in a simulated learner environment built on the Tatoeba corpus, our agent autonomously discovers a highly effective policy, achieving a mean episodic reward of 6.563, on par with the optimal heuristic baseline. The identified policy, albeit optimal in the simulation, embodies a counterintuitive method that significantly prioritized task repetition by the learner. Our hypothesis is confirmed by a critical ablation experiment: an agent that is deprived of the cognitive-behavioral signals does not learn, and they are as good as a random baseline (mean reward 5.213). The present work gives conclusive evidence that multimodal cognitive-behavioral cues are not only supplementary but are an inevitable part of learning by adaptive pedagogical agents. We mainly provide validation of a hybrid state representation that allows an RL agent to learn effective teaching strategies, making way for more useful and customized educational technologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Evaluating and improving teaching quality is crucial to the effectiveness of higher education and language instruction1,2. High-quality teaching enhances comprehension, retention, transfer, and long-term learner success3,4, while also supporting institutional accountability and continuous curricular improvement5. Traditional evaluation methods such as end-of-term surveys, classroom observations, and peer review remain valuable but suffer from essential limitations in guiding adaptive instruction6,7,8. They are often retrospective, coarse-grained, biased, and unable to provide the continuous9, moment-to-moment feedback is required to support real-time pedagogical adaptation10,11. These shortcomings motivate objective, data-driven approaches that treat teaching as an ongoing decision-making problem: by observing learners’ performance and behavior11,12, an adaptive system can infer the student’s state and select interventions that maximize learning over time13,14,15.

Using student academic performance and multimodal behavioral traces as proxies for teaching quality is a practical route to data-driven evaluation and personalization16,17. Prior work in student performance prediction (SPP) has shown that features such as prior achievement, response correctness, response time, and attention proxies18,19,20, and interaction patterns can reliably predict short-term outcomes and support individualized sequencing21. Classical machine-learning methods (logistic regression, decision trees, Random Forests, and gradient-boosted trees) have demonstrated strong predictive performance in many educational settings22. More recent representation-learning approaches, which draw from advances in fields such as deep learning and network analysis23,24, have further enhanced the ability to model complex student data. At the same time, Reinforcement Learning (RL) has emerged as a complementary paradigm that extends beyond prediction to optimize sequences of pedagogical actions with long-term learning objectives25,26,27. Where SPP predicts outcomes, RL learns policies that choose hints, repetitions, or explanations to maximize cumulative learning gains28,29,30.

Despite promising progress, several gaps hinder the translation of this knowledge into reliable, classroom-ready systems31,32,33,34. First, many RL-ITS studies evaluate agents primarily in simulated or offline log settings, rather than with real learners, leaving open the question of whether learned policies generalize to noisy, human-generated multimodal signals35,36. Second, prior work often restricts the tutoring action space to a few discrete, single-step interventions, thereby limiting pedagogical richness and ecological validity37,38. Third, multimodal behavioral and cognitive-behavioral signals (response time, attention proxies, hint requests) are often underutilized or coarsely modeled, and resulting policies are rarely interrogated for interpretability making it hard for instructors to trust or understand automated decisions39,40.

To address these needs, this paper proposes a hybrid cognitive–linguistic RL framework for adaptive language training. The core approach constructs a joint state representation by concatenating a 512-dimensional semantic embedding (from a pre-trained T5 encoder) with a 4-dimensional cognitive-behavioral vector (correctness, response time, attention score, hint request). A Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) actor–critic agent uses this 516-dimensional state to select among three pedagogical actions (repeat, hint, reveal answer) and is trained in a reproducible simulated-learner environment built on a 50 k English–Spanish sentence corpus. The reward design balances immediate correctness, a cognitive bonus rewarding efficient and attentive behavior, and action penalties to discourage excessive assistance. Crucially, the study includes ablation experiments that show removing cognitive-behavioral signals collapses learning to random performance, detailed training dynamics analysis, and behavioral policy inspections (action distributions, t-SNE state visualizations) to clarify what the agent has learned.

The main contributions of this work are:

-

Introducing a hybrid cognitive–linguistic state representation that fuses semantic embeddings with multimodal cognitive-behavioral proxies for adaptive tutoring.

-

Demonstrating a PPO-based tutoring agent that autonomously discovers effective pedagogical strategies in simulation and quantifying the indispensability of cognitive-behavioral signals via ablation.

-

Providing interpretability and behavior analyses (policy evolution, action distributions, state visualizations) alongside a practical experimental protocol for progressing from simulation to human-in-the-loop validation.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. “Related works” section reviews related work on student performance prediction, multimodal learner modeling, and RL in educational systems. “Methodology” section details the methodology, covering the dataset and simulated-learner design, the RL formulation, agent architecture, and the training and evaluation protocols. “Experimental results” section reports the experimental results, including the agent’s training dynamics, a comparative performance analysis against baselines, and a behavioral analysis of the learned policy. “Discussion” section discusses the key findings, limitations, and implications of the study. Finally, “Conclusion” section concludes the paper by summarizing the primary contributions and outlining future research directions.

Related works

Authors of Riedmann et al.25 conducted a systematic literature review on the application of RL in education. They also reviewed 89 RL-based adaptive learning papers across various areas, following the PRISMA guidelines. They classified RL algorithms, educational tasks, and reported outcomes. The review notes that RL has the potential to deliver personalized instruction and enhance the results of learners, yet there is also a high level of challenges. Most importantly, a significant portion of research utilizes simulated learner data instead of actual interaction with students, and only a small number of studies involve large-scale deployment and human trials. The authors conclude that RL can help improve teaching strategies, although the existing evidence is also methodologically problematic and has not been evaluated in real-world settings. This aligns with our gap: the expanded, user-based RL experiments, which focus on testing outside of simulation.

Zerkouk et al.41 offer a comprehensive review of AI-based Intelligent Tutoring Systems (ITS). Based on research on the topic published between 2010 and 2025, they examine the role of AI techniques in supporting ITS capabilities, such as learner modeling, personalization, and feedback. They discover the complicated topography: on the one hand, most ITS include sophisticated AI, but on the other hand, no single design is superior. Most importantly, their synthesis highlights the fact that the strength of empirical evidence is often low; the majority of ITS research has either small-scale or inconclusive outcomes and lacks critical assessment. The authors stress that in these domains, standardized experiments and real-life experiments are not readily available, and that numerous systems are based on controlled conditions or small sample sizes. Weaknesses of this review are that it is based on published reports (which are prone to publication bias). Nevertheless, its results support our research gap: even the state-of-the-art ITS needs better support in terms of validation based on actual learners and various settings. Recent systematic reviews have examined the significance of particular skills, such as computational thinking, in STEM education, similarly highlighting deficiencies in existing pedagogical practices and research42.

Work in Zhu et al.43 performed a quasi-experimental field study of adaptive microlearning for adult training. They established an Adaptive Microlearning (AML) platform to balance the cognitive load by adapting the content pacing, comparing it with a standard microlearning (CML) platform. They employed ANCOVA to make comparisons between the groups, which consisted of 109 in-service personnel participants. The AML users had a significantly lower cognitive load and exhibited more adaptive learning compared to the CML group. This implies that overload can be reduced by personalization, and learning flexibility can be improved. This methodologically supports the use of adaptive design in practice. However, its weaknesses are the lack of randomization, a small sample (mid-career professionals), and the use of self-reported scales. No long-term follow-up is available. Although this research does not utilize RL, it confirms that adaptive systems can reduce cognitive strain. Still, it also points to the necessity of more rigorous trials with a heterogeneous group of learners, which is the same conclusion we have reached so far. Other educational frameworks, including project-based learning, have been examined for their efficacy in student preparation, frequently without the adaptive mechanisms integral to our research44.

Tong et al.45 introduce a novel deep-learning approach that fuses knowledge tracing with cognitive load estimation to generate personalized learning paths. They have a dual-stream neural architecture that consumes data on student performance and predicts cognitive states, which in turn predict mastery and optimize task sequencing in order to improve learning outcomes. In several real-world databases, this combined system performed better than baselines: the accuracy of prediction of the knowledge is increased (87.5% vs. 83.7%), and the learning paths were rated better (mean 4.4/5). Students who used the system experienced greater retention and interaction. These results illustrate the benefits of paying attention to what the students know and how they think about information to be able to change the instruction. The research, however, has identified important limitations: cognitive load was not measured with physiological data, but only through interaction logs without considering any other factor, like emotion or motivation. The approach also involves complex optimization that may not scale easily. This implies our domain could benefit from richer multimodal feedback (beyond observable performance) and more efficient models, highlighting a gap in integrating comprehensive cognitive-behavioral signals into adaptive tutoring. Recent frameworks have also looked into how to combine game dynamics with AI-driven personalization to make adaptive systems that improve learner motivation and outcomes46.

Schmucker et al.47 present a large-scale exploration of feedback optimization in an online tutoring system using bandit learning. They leveraged data from one million students to train multi-armed bandit (MAB) and contextual bandit policies that select the most effective hint or help after a student’s incorrect answer. Through offline policy evaluation of 166,000 practice sessions, they found that a well-tuned MAB policy significantly improved student success rates and session completion rates. Incorporating student features into contextual bandits allowed some personalization, but the authors observed that heterogeneity in action effectiveness was generally small; thus, contextual models offered only marginal gains over the non-contextual policy. This suggests that in practice, a single optimized strategy often suffices. A limitation is that their focus was on single-step feedback (post-question) rather than long-term, multi-step tutoring strategies. In sum, this study supports the promise of data-driven adaptivity but also implies that scaling to fully sequential RL with rich feedback remains an open problem.

Researchers in Scarlatos et al.48 develop a reinforcement learning–based fine-tuning of LLM tutors aimed at directly maximizing student learning. They generate candidate tutor utterances (from human and AI sources) and score them by (1) a student-response model predicting the chance of a correct answer and (2) a pedagogical quality rubric evaluated by GPT-4. These scores become preference data to train an open-source Llama 3.1 (8B) model using Direct Preference Optimization (a form of offline RL). The resulting tutor utterances significantly increase the likelihood of the student answering correctly in the next turn, while matching the pedagogical quality of much larger models. This demonstrates that RL objectives can improve tutoring dialogues. The major limitation acknowledged is that all training and evaluation used a simulated student model; no experiments involved real learners. Thus, as with other studies, the true benefit of this approach in practice is unverified. This underscores our motivation: even advanced AI tutors require human-in-the-loop validation to confirm that optimized policies generalize beyond simulation.

Sharma et al.49 describe early-stage work on generating simulated students for open-ended learning environments. They model cognitive and self-regulatory states based on real log data, then use these models to emulate learner actions. Using prompts to LLMs, they generate plausible dialogue responses corresponding to simulated student states. The aim is to create a large dataset of learner–tutor interactions that can train RL-based tutoring agents where real data are scarce. As a proof of concept, the paper focuses on the proposed methodology, without reporting any experimental results. The weakness is clear; it is a theoretical framework that has not been empirically tested. Nonetheless, it also points out that when creating adaptive dialogue tutors, it is necessary to complement the scarce real data with quality simulation. Our objective of investigating multimodal simulations is in line with this strategy as a step towards realistic RL tutoring.

All these works contribute to the knowledge of adaptive tutoring, yet they also show some gaps. Their approaches, results, and limitations are summarized in Table 1 to address our research gap. It demonstrates that even more recent studies adopt different methods (systematic reviews, field studies, and RL algorithms) and claim advantages (personalization, cognitive balancing, better results). It is worth noting that most of them have disadvantages: excessive use of simulations or small samples, restricted action space, and the absence of human experimentation. These constraints help highlight the necessity of the field to incorporate more multimodal feedback and be subjected to large-scale real-world experimentation. To conclude, the literature shows that adaptive learning methods have improved, yet there is still a strong demand to have stronger, more learner-focused assessments, which is the driving force behind our present research.

Methodology

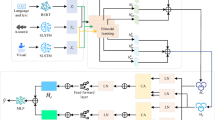

This section describes the procedure of a proof-of-concept research that would create and experiment with an agent of reinforcement learning to create adaptive language training, as shown in Fig. 1. The methodology focuses on finding fast validation in a simulated setting. The system has a closed loop that is characterized by an agent of RL acting as a tutor who interacts with a simulated student and observes indicators of performance or cognition. According to these observations, the agent chooses pedagogical action, gets a reward for its effectiveness, and redefines its policy. This type of iterative process enables the RL agent to learn on its own to use effective teaching strategies.

Dataset and simulated learner environment

In order to make experiments quick and repeatable without having to test them on a large scale using human subjects, we created a simulated learner environment. The foundation of this environment was a public dataset of 50,000 sentence pairs of English–Spanish sentences of the Tatoeba corpus, based on which the linguistic background of the translation exercises was established50.

In order to produce the multimodal feedback on which our study relies, the basic dataset was supplemented with simulated cognitive and behavioral feedback on every pair of sentences. These signals were designed to mimic the interaction patterns of a real learner. The first of these signals was learner correctness, represented as a binary value ccc, which was assigned with a 70% probability of being correct, thereby simulating a learner with partial mastery of the material.

Response time (RT) was also simulated as a function of sentence length with added Gaussian noise. If \(L\left( x \right)\) denotes the number of words in a sentence xxx, then the response time was modeled as shown in Eq. 1:

where \({\upalpha }\) is a scaling factor and \(\epsilon_{rt} \sim N\left( {0,\upsigma _{rt}^{2} } \right)\) represents Gaussian noise. For reproducibility, we set the scaling factor \({\upalpha }\) = 0.5 (representing a base half-second per word) and the noise variance \(\upsigma _{rt}^{2}\) = 0.01.

A further signal, the attention score, served as a proxy for engagement and was simulated to be inversely correlated with response time. The attention score \(A\) was modeled as Eq. 2:

where \(\upbeta\) is a scaling factor and \(\epsilon_{a} \sim N\left( {0,\upsigma _{a}^{2} } \right)\) is a small noise term. We set \(\upbeta\) = 1.0 (for a direct inverse correlation with normalized RT) and the noise variance \(\upsigma _{a}^{2}\) = 0.0025.

Finally, we introduced the hint request signal, represented by a binary flag \(h\). This value indicated whether a learner required a hint during the exercise and was drawn from a Bernoulli distribution, \(h \sim {\text{Bernoulli}}\left( {0.15} \right)\) to align with the empirical 14.9% hint request rate shown in Fig. 2. Together, these components created a simulated learner environment capable of producing realistic, multimodal data to support experimentation.

Figure 2 shows the statistical distributions of the four major cognitive-behavioral cues that form the state space of the reinforcement learning agent, based on our simulated learner environment. The figure is made up of four subplots, which describe separate aspects of the behavior of the simulated learner. The RT violin plot of the top-left indicates that most of the responses are fast and are skewed towards the left of 5 s. The lengthy upper tail shows that there are rare but considerably prolonged response times, which are related to more difficult questions. The Attention Score is the highest right histogram and is highly left-skewed with a strong peak at the highest score of 1.0; this indicates that the learners being simulated are mostly attentive, but with a variation in the levels of engagement. The bottom-left pie chart on the Correctness of Learner Response shows that the correctness rate is 70.1% which is an adequate number of correct and incorrect examples that the agent can learn, a moderately complex learning environment. Lastly, the bottom-right pie chart in Hint Requests shows that hints are utilised in 14.9% of the interactions, which is a fairly clear but less common indication of the learner’s difficulty. Taken as a whole, these distributions constitute a realistic and balanced simulated dataset, which has a rich range of learner states that can successfully inform the training of an adaptive pedagogical agent.

Supervised pre-training of the language model

In order to equip the agent with a strong language knowledge for the language tasks, we trained a basic language model in advance. We used a T5-small transformer model, which was selected because of its performance and computational efficiency. The Tatoeba dataset was used to train the model on the primary task of English to Spanish translation. This pre-training phase is supervised to ensure the encoder of the model is able to generate meaningful semantic embeddings of the source sentences, which is the linguistic part of the state representation of the agent. The model that was least able to validate was stored to be used in the RL environment.

Figure 3 shows the learning curves of the model in the supervised pre-training phase, which plots the cross-entropy loss as a function of the training epochs. The teal line, which is a measure of the training loss, is generally decreasing with a substantial and steady downward trend since it has a value of around 2.85 at epoch one and reduces to a value of less than 2.0 towards epoch 4. This decrease implies that the model is actually studying to adjust to the patterns of the training dataset. At the same time, this positive trend is reflected in the orange line, which indicates the loss of validation on another, invisible dataset, but in this case, it is also characterized by a steady decrease between approximately 2.18 and 1.58. Importantly, the validation loss reduces correspondingly to the training loss, which proves that the model is indeed generalizing its acquired knowledge to new data without the overfitting effects. The fact that both curves converge at the same point attests to the stability and effectiveness of the pre-training process, which is able to initialize the weights of the model to a state of understanding the basic structure of the pedagogical interactions, which gives it a solid point to proceed with the fine-tuning of the reinforcement learning.

RL formulation

The learning problem was formalized as a Markov Decision Process (MDP), defined by the tuple \(\left( {S,A,P,R,{\upgamma }} \right)\), where \(S\) is the state space, \(A\) is the action space, \(P\) is the state transition probability function, \(R\) is the reward function, and \({\upgamma }\) is the discount factor. The novelty of our approach lies in the hybrid state representation, \(s_{t} \in S\). Each state is represented as a 516-dimensional vector that combines both linguistic and cognitive features.

The linguistic representation is a 512-dimensional embedding,\(e_{t} = {\text{Encoder}}\left( {x_{t} } \right)\), generated by a pre-trained T5 encoder for the source sentence \(x_{t}\). Alongside this, the cognitive representation is a 4-dimensional vector, \(c_{t} = \left[ {{\text{correctness}}_{t} ,RT_{t} ,A_{t} ,h_{t} } \right]\), which captures the simulated learner signals of correctness, response time, attention score, and hint usage. The complete state vector is formed by concatenating these two components, as expressed in Eq. 3:

where \(\oplus\) denotes the concatenation operation.

The action space was defined as a set of three discrete pedagogical interventions, \(A = \left\{ {a_{0} ,a_{1} ,a_{2} } \right\}\). Action \(a_{0}\) corresponds to repeating the question, representing a minimal intervention that prompts the learner to attempt the task again. Action \(a_{1}\) provides a hint, a moderate form of support offering scaffolding for the learner. Action \(a_{2}\) delivers the complete answer, a maximal intervention that concludes the current task.

The reward function \(R\left( {s_{t} ,a_{t} } \right)\) was carefully designed to guide the agent towards effective teaching strategies. At each step, the total reward \(R_{t}\) is computed as the sum of three components, as defined in Eq. 4:

The first component, the performance reward \(\left( {R_{{{\text{perf}}}} } \right)\), provides direct feedback based on learner correctness. As shown in Eq. 5, the agent receives a positive reward of + 10 if the learner responds correctly \(\left( {c_{t} = 1.0} \right)\), and a negative reward of − 5 if the response is incorrect \(\left( {c_{t} = 0.0} \right)\):

The second component, the cognitive bonus (\(R_{{{\text{cog}}}}\)), rewards efficient and attentive performance by integrating the learner’s attention score and normalized response time. This is expressed in Eq. 6:

where \(A_{t}\) denotes the attention score, \(RT_{{{\text{norm}}_{t} }}\) is the normalized response time, and \({\uplambda } = 2.0\) is a scaling parameter.

The final component, the action penalty (\(R_{{{\text{action}}}}\)), discourages over-reliance on assistance. As defined in Eq. 7, a hint action \(\left( {a_{t} = a_{1} } \right)\) incurs a penalty of − 1.0, while providing the full answer \(\left( {a_{t} = a_{2} } \right)\) incurs a stronger penalty of − 3.0. No penalty is applied when the agent repeats as Eq. 7:

The precise weights for this function (+ 10 for successful responses, − 5 for bad responses, and penalties of − 1.0 and − 3.0) were established heuristically via repeated pilot testing. The tuning process was crucial for establishing a stable learning signal, ensuring that the performance reward (Eq. 5) was sufficiently significant to promote learning, while the action penalties (Eq. 7) were adequately substantial to deter excessive dependence on assistance, thereby compelling the agent to achieve an optimal equilibrium between learner success and intervention cost. Together, this formulation ensures that the agent balances learner performance, cognitive engagement, and the pedagogical cost of interventions when deciding how to act.

Agent architecture: actor–critic model

We implemented an Actor–Critic agent, a neural network architecture particularly well-suited for learning in complex state spaces. The model takes the 516-dimensional state vector \(s_{t}\) as input, which is then passed through two shared hidden layers with ReLU activation functions to capture nonlinear representations. These shared layers enable the network to learn a compact yet expressive encoding of both the linguistic and cognitive features of the learner’s state.

After this shared representation, the network branches into two output heads. The first is the Actor (Policy Head), which is responsible for learning the policy \(\uppi _{\uptheta } \left( {a_{t} s_{t} } \right)\). This head maps states to a probability distribution over the available actions. It is implemented as a linear layer followed by a softmax activation, ensuring that the outputs form a valid probability distribution across the three pedagogical interventions.

The second branch is the Critic (Value Head), which learns the state-value function \(V_{\phi } \left( {s_{t} } \right)\). This function estimates the expected cumulative reward from a given state \(s_{t}\), thereby providing a baseline for evaluating the quality of the actions chosen by the actor. The critic head is implemented as a linear layer that outputs a single scalar value.

In this framework, \(\uptheta\) and \(\phi\) denote the parameters of the actor and critic networks, respectively. The combined architecture enables the actor to improve its policy by leveraging the critic’s value estimates, while the critic is simultaneously refined using the observed rewards and temporal difference errors. This synergy between the two components makes the Actor–Critic method particularly effective in dynamic, high-dimensional learning environments such as the one we designed.

Figure 4 provides the neural network structure of the reinforcement learning agent that is founded on an Actor-Critic model. There are two different kinds of input to the architecture that are processed to create a complete picture of the present state. The initial input is the T5 Encoder Output, which is a high-dimensional vector (dim = 512) representing the semantic context of the textual interaction. The second input is the four Cognitive-behavioral signals (dim = 4), which include the quantitative data of the immediate state of the learner. These two inputs are joined together to form a single state vector, which is then input into a common network body. This common element is two sequential fully connected layers, which gradually reduce the dimensionality of the representation, first to 256 and then to 128, which enables the model to learn a small, salient set of features on the aggregate inputs. After these common layers, there are two heads of the architecture, divided into two. The Actor Head is in charge of policy-making; it produces a probability distribution over the three possible actions (Action Probs, dim = 3), which defines the next action of the agent. The Critic Head analyses the present state and returns a single scalar (State Value, dim = 1), which is an approximation of the future reward of that state. This two-headed structure lets the agent learn at the same time (the actor) what to do, and (the critic) how to measure the quality of its present situation, which is a fundamental principle of efficient Actor-Critic reinforcement learning algorithms.

Training algorithm: PPO

The agent was trained using the PPO algorithm, a state-of-the-art reinforcement learning method widely recognized for its stability and sample efficiency. At the heart of PPO lies the optimization of a clipped surrogate objective function that constrains policy updates, thereby preventing overly large and destabilizing parameter shifts during training.

To begin, we define the probability ratio \(r_{t} \left( {\uptheta } \right)\) as provided in Eq. 8:

where \(\uppi _{{\uptheta _{{{\text{old}}}} }}\) represents the policy prior to the update. This ratio measures the extent to which the new policy diverges from the old one in terms of the likelihood it assigns to the chosen action.

The PPO objective function is then formulated as Eq. 9:

here \(\widehat{{A_{t} }}\) denotes the estimated advantage function at timestep \(t\), and \(\epsilon\) is a hyperparameter controlling the clipping range. The clipping mechanism ensures that policy updates remain within a safe bound, thereby balancing improvement with stability.

The final optimization objective also incorporates two additional terms: a value function loss, which stabilizes learning by improving state-value predictions, and an entropy bonus, which encourages exploration by preventing premature convergence to deterministic policies.

For training, we selected hyperparameters that strike a balance between learning speed and convergence reliability. Specifically, we used a learning rate of \(1 \times 10^{ - 4}\), a discount factor of \({\upgamma } = 0.99\), and a clipping parameter of \(\epsilon = 0.2\). These settings provided the agent with both the capacity for long-term reward optimization and the stability required for effective policy refinement.

Evaluation and baselines

To test the performance of our trained PPO agent, we did a comparative analysis with three baseline strategies on the held-out validation set. The initial baseline was the Random Agent, which chose the actions randomly. The methodology offered a lower-bound reference point, which indicated how poorly the performance would work without any learning or decision-making process.

The second baseline was a naive Heuristic policy called Always Hint, where the agent always used Action 1. This plan was a medium-term but rigid intervention, which provided the learners with scaffolding at all stages without responding to their performance or engagement indicators.

Another heuristic policy that was used as a baseline was the Always Repeat, whereby the agent chose Action 0 all the time. This strategy was the minimal intervention strategy, whereby the learner was repeatedly encouraged to repeat doing the same task, but no further assistance was given.

Through setting the PPO agent in comparison with these baselines, we could determine the possibility of the agent overcoming random decision-making and strict heuristic policies, thus showing its ability to adaptively balance pedagogical interventions depending on the state of the learner.

Ablation study

In order to quantify, in particular, the role of the cognitive-behavioral signals in the performance of the agent, we performed an ablation study. We trained a second PPO agent in an ablated environment where representation of the state was only the 512-dimensional linguistic embedding, and the 4-dimensional cognitive-behavioral vector was deleted. Their performance was then simply compared to our full and cognitively aware agent.

Experimental results

RL training dynamics

The RL Training Dynamics analysis gives a very important insight into the learning process of the agent, as it goes beyond an evaluation of the ultimate performance to the actual learning process of the policy. This is done by monitoring key measures during the training procedure, including the development of rewards, convergence of internal loss functions, and the development of the action selection strategy of the agent. This analysis is necessary on a variety of grounds: it confirms that the end result, high performance of the agent, is not an accident but due to consistent and non-trivial learning; it enables us to diagnose learning, to see how the agent adapts strategically towards an optimal policy; and it shows how the agent changes as it approaches an optimal policy. Primarily, examining these dynamics will give the required evidence to believe the ultimate model and understand how it obtained its findings, turning it into a black box and a descriptive system.

Figure 5 represents the learning process of the agent by the moving average of the episodic reward, averaged over 100 episodes, over 2000 training episodes. The curve shows an evident and positive learning curve. At first, the agent performs poorly, as shown by the negative rewards at the very beginning. Nonetheless, it is much better in the initial 100 episodes, and the average reward increases to about six rather fast. After this first rapid learning stage, the agent goes into a long exploration and policy improvement phase, with a major fluctuation in the reward curve, with a sharp decline around the 1000 episode mark. This volatility is a sign that the agent was testing different strategies to make its behavior the best. Since around episode 1250, the performance begins to stabilize at a greater level, and the reward curve has a steady rising trend and finally reaches an average reward of more than 8. This long-term high performance during the later phases of training implies that the agent has mastered a useful policy of engaging the simulated learner to maximise the cumulative rewards.

The dynamic of internal training of the Actor-Critic agent is also seen in Fig. 6, which shows the moving average of the actor loss (red) and critic loss (blue) on a logarithmic scale over 2000 episodes. The critic loss exhibits a healthy learning curve with an initial high value of about 102 and a consistent significant decline at the first 1500 episodes, and then a low value at 10 − 1. This decreasing trend shows that the critic network is learning effectively to predict the value of various states, which is an important factor to drive policy changes. Conversely, the actor loss, which is depicted in red, has a great deal more variance and is not concentrated at one low figure. This is normal behavior of the policy-driven approaches, including PPO, where the loss is proportional to the scale of policy changes. The high-frequency spikes and fluctuations are indicators of active exploration and fine-tuning of policy, as the agent optimizes its policy given the advantage estimates that are made by the more precise critic. The converging critic loss and the dynamic actor loss are both signs of a stable and efficient training process in which the agent will keep on improving its decision-making policy.

Figure 7 shows the stacked area chart, which depicts the time-dependent development of the policy of the agent by presenting the moving average percentage of actions performed. The strategy of the agent is changed in a very different and notable way during the training process. During the first stage, until about episode 1000, the agent quickly becomes conditioned to prefer to take Action 1 (Hint), which soon dominates its policy, indicating that hinting is an initially successful policy of earning rewards. Action 2 (Answer) is made with relatively low frequency during this period, but the frequency of its use decreases with time, which is indicative of the agent learning that it is a less favorable option, whereas Action 0 (Repeat) is made with a relatively low frequency. Nevertheless, a turning point in terms of strategy starts approximately in the middle of the training. The percentage of the “Action 0 (Repeat)” starts growing gradually, whereas the dependency on the “Action 1 (Hint)” starts to decrease. This trend significantly intensifies post-episode 1250, culminating in the agent’s policy predominantly favoring “Action 0 (Repeat)” by the conclusion of the 2000 episodes, which, as elaborated in “Learned policy and behavior analysis” section (Fig. 11), constitutes 99.9% of its ultimate action choices. This radical change of policy indicates that the agent can no longer afford a strategy that is locally optimal (hint-giving) to find a strategy that is globally optimal (prompting the learner to repeat) and hence maximizes its cumulative reward over time.

Agent performance and comparative analysis

With that having been established, that the agent did manage to learn a stable policy, this section moves on to a strict analysis of the effectiveness of that final policy. Another important element of testing any intelligent agent is not merely to test its absolute performance, but to put it into context by comparing it to clearly outlined baselines. Thus, we use the trained PPO agent as a baseline to more basic, non-learning agents: a Random agent which acts without a strategy, and two Heuristic agents which act according to fixed, rule-based policies. The value and sophistication of the learned strategy can be quantitatively determined by comparing the distributions of rewards gained by each agent. This is not just the aggregate performance but also the performance of each agent in different circumstances, and in the end proves the flexibility and high-order decision-making skills of the fully trained PPO agent.

The total reward per episode acquired by four distinct agent types is put in a comparative boxplot analysis in Fig. 8, which gives a clear benchmark of the performance of the trained PPO agent. The first agent to prove that it is ineffective is the Random Agent that chooses a course of action without any strategy and has a wide range of rewards and a median that is much lower than that of the other agents. These two heuristic agents are simple and rule-based policies. The Heuristic (Hint) agent, which always gives a hint, performs very well compared to the random baseline, with a median reward of around 10. The Heuristic (Repeat) agent is even more successful, as it has a slightly higher median and a narrower distribution of rewards, meaning that the strategy of constantly reminding the learner to continue is a solid one. Most importantly, the PPO Agent shows the best performance, attaining the largest median reward and the best distribution in general. It has a narrow interquartile range and it is located on the higher part of all baselines, which means not only the maximum average performance, but also the most stable and dependable results. This performance proves that the PPO agent has effectively acquired an adaptive policy that goes beyond mere heuristics because it responds dynamically to the state of the learner so as to maximize rewards.

Figure 9 gives a more detailed comparison of agent performance by showing split violin plots, which distort the episodic reward distributions by the accuracy of the first response of the learner. To each agent, the green distribution at the left depicts episodes commencing with a correct learner response. Conversely, the red distribution on the right matches episodes that start with a wrong answer. This visualization clearly brings out the constraints of the fixed-policy baselines. An example of this is the Heuristic (Repeat) agent that works very well in cases where the learner is already in the correct state, but poorly in cases where they begin in an incorrect state. On the other hand, the Heuristic (Hint) agent exhibits a reasonable distribution with regard to wrong initial states, but is not optimal otherwise. In sharp opposition, the PPO Agent has a better adaptive strategy. It attains a very narrow and high-value reward distribution when the learner begins with the correct action, which means that it has learned to use an optimal low-intervention strategy in a favorable situation. Importantly, it also has a highly positive distribution of rewards when the learner begins to make a mistake, which demonstrates its capacity to intervene effectively and help the learner resume his or her successful course. This conditional analysis provides support to the fact that the PPO agent has higher overall performance due to its acquired capability to use various, context-specific strategies, which is better than the agents with heuristics, which have no change in the two cases.

Figure 10 is a violin plot that sums up the final rewards in all training episodes, giving a holistic picture of the landscape that the agent explored in the course of learning. The distribution is clearly bimodal, which exposes two major groups of episodic results. The bigger, dominating mode is located in the positive reward area with the centre of + 10. This broad upper distribution is an indication of the commonality of successful episodes in which the actions of the agent succeeded in producing positive learning results and high cumulative reward. There is a second, smaller mode in the negative reward space, which is centered at − 4. This reduced distribution is associated with failure episodes in which the policy of the agent led to penalties. This extreme segregation of these two modes, where the density of the rewards about zero is extremely low, suggests that interactions within this environment are likely to produce easily positive or easily negative consequences, and not neutral ones. The higher weight of the positive area proves that successful trajectories arose more frequently than the unsuccessful ones during the whole training history of the agent.

Table 2 also presents a quantitative analysis of the performance indicators of the five types of agents considered, which supports the results of the visual plots. The PPO Agent model with the highest performance, which has a mean reward of 6.563 and a median reward of 10.853, is the fully-equipped one. Its performance is almost equal to the best-performing baseline, which is the Heuristic (Repeat) agent (mean 6.564, median 10.854), and confirms the observation that the PPO agent has learned a policy that highly prefers the repeat action. The two mentioned agents are by far better than the Random Agent (mean 5.231) and the Heuristic (Hint) agent (mean 5.564). However, the most important lesson of this table is the one offered by the study of ablation. The agent with no cognitive-behavioral signals (PPO No Cognitive-Behavioral), which was not given the four cognitive-behavioral signals during the training process, performs dismally with a mean of 5.213 and a median of 8.526. These numbers are nearly the same as those of the Random Agent, and it shows that they failed to learn an effective policy. This sharp contrast between the full PPO Agent and the one that is ablated clearly shows that the cognitive-behavioral signals are not only useful but also necessary for the agent to acquire a successful and adaptive pedagogical strategy.

Learned policy and behavior analysis

Although the performance of the PPO agent was proven to be superior in the previous section, this section goes further to examine the nature of the learned policy and the behaviour thereof. The goal is to go beyond aggregate reward measures and the logic of decision-making by the agent by breaking down its ultimate strategy. We will observe the general spread of actions in order to determine the interventions that the agent favors and will analyze the visualization methods to examine the state-action mapping and whether the agent is using a consistent approach or a state-specific approach to the behavior. This way of deconstructing the end policy will allow us to have a clear and interpretable picture of the pedagogical strategy that the agent eventually found to be the best in the simulated environment.

The final action selection strategies used by the various agents are visually compared with the use of a series of pie charts given in Fig. 11. As anticipated, the Random Agent is almost uniformly distributed, with the probability of each of three actions, Repeat (33.5%), Hint (33.1%), and Answer (33.4%) being almost equal, which defines this agent as an uninformed baseline. Both heuristic agents are seen to be deterministic: the Heuristic (Hint) agent makes a 100 percent decision to act 100 percent of the time, and the Heuristic (Repeat) agent makes a 100 percent decision to act 100 percent of the time, according to their rules. The most disclosing chart is the one of the PPO Agent. Through much training, its trained policy demonstrates a strong bias towards one action, and the choice is 99.9% in favor of Repeat. The alternative actions are practically overlooked, and Hint is selected only 0.1% of the time, and Answer is never selected. This finding is a strong indicator that the reinforcement learning process was able to overcome the dynamics of the environment and arrive at a policy that is almost the same as the one that the heuristic performs the best, supporting the idea that the most effective strategy to use in this particular simulated environment is to encourage the learner to repeat.

Figure 12 uses the t-SNE (t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding) method of dimensionality reduction to display the high-dimensional internal state representations that the PPO agent learned. Every point in the scatter plot represents a particular state that the agent experienced when being evaluated, plotted down into a two-dimensional space to be visualized, and colored based on the action taken by the ultimate policy of the agent. The plot shows that there are a few separate clusters and structures in the data that suggest that the neural network of the agent has managed to learn how to create a structured internal representation, cluster similar states. Nevertheless, the most noticeable aspect of the visualization is the total homogeneity of the color; practically all the points are blue, which symbolizes the Repeat action. This homogeneity in a variety of and well-separated clusters of states gives strong visual evidence that the agent has narrowed down to an almost deterministic policy. Even though the agent is able to discriminate between various situations, it has become aware that the best strategy in practically the whole state space is to have the learner repeat the question over and over again.

Figure 13 displays a heatmap of the Pearson correlation matrix, which quantifies the linear relationships between the four cognitive-behavioral signals and the final episodic reward. The color scale indicates the strength and direction of the correlation, with deep red representing a strong positive correlation (+ 1), deep blue representing a strong negative correlation (− 1), and light colors indicating a weak or no correlation (near 0). The most significant relationship observed among the signals themselves is a moderately strong negative correlation of − 0.61 between response time and attention score, suggesting that as the simulated learner’s response time increases, their attention score tends to decrease, which is an intuitive relationship in a learning context. Nonetheless, the most important lesson out of this analysis is the connection between the personal signals and the ultimate reward. The last line of the heatmap indicates that all cognitive-behavioral signals, when individually used, are nearly correlated to the total reward at the end of an episode (the value of the correlation is between − 0.02 and 0.01). The significance of this discovery is very high since it shows that there is no single cognitive-behavioral indicator that can be considered a good predictor of long-term success. This highlights the difficulty of the teaching problem and confirms the need to have a sophisticated model, like our PPO agent, which can learn more complex, non-linear relations between the full state vector to guide its decision-making policy.

Ablation study results

In order to single out and measure the role played by the cognitive-behavioral signals in the success of the agent, we have performed a focused ablation study. This required the retraining of the same PPO agent, except that one of its four cognitive-behavioral cues was omitted from its input, leaving it to respond only to the textual situation of the communication. The given direct comparison is aimed at answering the very basic question: Are the cognitive-behavioral signals simply an additional piece of information or a necessary ingredient of learning an effective pedagogical policy? We can assess the effect of this multimodal input by comparing the performance of this “ablated” agent with the one that uses all of the features of a PPO agent, as well as the one that uses the random baseline, and conclusively determine the significance of this multimodal input to the architecture of our model.

The key findings of our ablation paper are shown in Fig. 14, where the three agent configurations are compared with boxplots to isolate the role of cognitive-behavioral signals on the distribution of the rewards. The Random Agent is used as a performance floor, where rewards are widely distributed. More importantly, the PPO agent that is trained without cognitive-behavioral signal, denoted as PPO (No Cognitive-Behavioral), is almost as effective as the Random Agent. The median reward and the interquartile range of it are almost identical to the baseline, which suggests that it was entirely unable to learn anything meaningful based on the text alone. In sharp contrast, the entire PPO Agent that employs both textual and cognitive inputs has a much better reward distribution. It has a significantly higher median reward, and the whole interquartile range is moved up, indicating superior results. This analogy gives conclusive data that the cognitive-behavioral signals are not an additional feature, but an essential part of the representation of the state of the agent. By removing them, the agent becomes unable to learn, which is why this particular aspect is of vital importance in creating an effective and adaptive pedagogical policy.

Discussion

The offered approach will present a new model of adaptive language training through the creation of an RL agent that will be an intelligent tutor. This system works in a well-designed simulated learner environment, which is meant to be experimented with quickly and repeatedly. The methodology is based on the hybrid state representation that integrates two different streams of information: a 512-dimensional linguistic embedding of a pre-trained T5-small transformer model that contains the semantic context of the language task and a 4-dimensional vector of simulated cognitive-behavioral signals that serves as a proxy of the state of the learner (correctness, response time, attention score, and hint requests). The combined 516 dimensions state is turned over to an Actor-Critic agent, which is trained via the PPO algorithm, and is used to choose one, three, or four pedagogical actions, namely, repeat the question, offer a hint, or the entire response. The aim of the agent is to discover a good teaching policy by maximizing a reward signal that is cumulative and carefully crafted to trade off between learning performance, cognitive engagement, and the pedagogical cost of the interventions.

The effectiveness of this procedure was proved in successive systematic experiments. Its initial T5 language model was pre-trained with a low final validation loss of around 1.58, so the model can be regarded as capable of producing meaningful semantic representations. In the next RL phase, the agent showed an evident learning curve of 2000 episodes, and its moving average reward gradually rose to negative values to a steady peak of more than 8.0, which means that the agent successfully reached an effective policy. Finally, the PPO agent who was fully-equipped had a mean reward of 6.563 and a median reward of 10.853 in the end. These measurements indicate the highest level of performance, which is equal to the best performing baseline, the Heuristic (Repeat) agent (mean 6.564, median 10.854), and far outperforms the Heuristic (Hint) agent (mean 5.564) and the Random Agent (mean 5.231). More importantly, the ablation experiment demonstrated that a PPO agent that was trained in the absence of cognitive-behavioral cues showed pathetic performance (mean reward 5.213), which confirms that the learning process was indeed dependent on this multimodal feedback.

The main conclusion of the study is the autonomous finding of the agent of a very efficient, but not obvious, pedagogical strategy. The development of the policy of the agent showed an advanced learning mechanism, in which the agent first used a safe, locally optimal policy of giving hints before finding the more globally optimal policy of repeating the question, which it chose in 99.9% of training. This behavioral pattern shows that an RL agent trained according to a properly structured reward function can discover strategies that maximize long-term outcomes of learners (as represented by the reward) compared to short-term interventions that appear useful but in fact are expensive.

It is, nevertheless, very important to look at this strategy from a teaching point of view, as the reviewer asked. This method is “optimal” in our defined simulation, but it goes against what we would expect from a teaching perspective. A policy that mostly tells a learner to “try again” without giving them any help will probably make them angry and lose interest. This outcome does not signify that the RL task is “meaningless” or that the approach “failed”. Instead, it brings attention to a major and important problem in the realm of educational RL: the possibility that an engineering reward function and real pedagogical effectiveness won’t work together. We theorize that this policy was established due to the substantial action penalties for ‘Hint’ (− 1.0) and ‘Answer’ (− 3.0), which led the agent to discern that the most ‘profitable’ strategy was to completely evade them, thereby incurring the minor time–cost of repetition to ultimately secure the significant + 10 performance reward. This makes the result seem like a normal and expected conclusion of the optimization objective, not a failure of the RL method.

The ablation study yields a definitive conclusion, unlike the discovered policy, which is ambiguous. As seen in “Ablation study results” section, the agent’s utter inability to learn without the cognitive-behavioral vector supports our main hypothesis. The importance of this finding is that it has implications for the field: it shows that semantic context (such T5 embeddings) alone is not enough for an agent to adopt a useful educational policy. To link its actions to real learner outcomes and provide a solvable credit assignment problem, the agent needs a “window” into the learner’s state.

Based on the final performance metrics, the best-performing algorithms were the fully-trained PPO Agent and the Heuristic (Repeat) agent, which were statistically almost identical in their reward distributions. The heuristic agent accomplished this via a rigid, pre-defined rule, whereas the outcome of the PPO agent is inherently more substantial. The reviewer indicated that the significance of the RL framework lies not in its superior performance over this particular heuristic, but in its capacity to independently identify the optimal policy from intricate, high-dimensional data without any prior domain expertise. This illustrates the framework’s aptitude for astute strategy identification, an essential competence for addressing more intricate issues when the optimal policy is not readily apparent. The worst-performing algorithms were the Random Agent and the ablated PPO (No Cognitive-Behavioral) agent. Their performance was nearly indistinguishable, confirming a complete failure to learn an effective policy. This comparison constitutes the primary, statistically significant result of our research. The difference between the full PPO Agent (Mean 6.563) and the ablated agent (Mean 5.213) is not only big (25.9% more mean reward), but it is also very important, showing the evident, measurable importance of the cognitive-behavioral signals. The most insightful aspect of the ablated agent’s failure is that without the four cognitive-behavioral signals, the high-dimensional linguistic data alone provided insufficient information for the agent to establish a clear link between its actions and the resulting rewards. This impoverished state representation made the learning task intractable, underscoring that the integration of multimodal feedback was the critical factor enabling successful policy learning.

This study contains a lot of important limits that set its scope, even though it was able to prove its premise. Critics of simulation-based research say that the biggest problem is that it only uses a simulated learning environment, which means that it hasn’t been shown to work in the actual world. This facilitated swift prototyping; yet, the simulated cognitive-behavioral signals represent reductions of intricate human behavior. These signals (correctness, RT, attention, hint request) are better described as simulated cognitive-behavioral proxies than direct indicators of cognitive processes. Our “attention score” is a behavioral metric that we came up with. These proxies are also formulaic, don’t have any real-world evidence to back them up (as seen in Eqs. 1 and 2), and their realism was assumed instead of being tested or compared to real-life expert human tutors. Also, our simulated learner is not dynamic; the distributions for accuracy and behavior are set and do not show how the learner is doing, how tired they are, or how much they depend on the long term. This is a very important simplification because a real learner’s state changes over time. Second, the study used a small and separate action space (repeat, hint, answer), which doesn’t show how rich true tutor behavior may be in terms of teaching. Thirdly, the actions were separate from each other, but many teaching methods, such how detailed a hint is or how long feedback is, may be better shown in a continuous action space. Lastly, the study only looked at one language activity (translation), therefore the best way to learn that skill might not work for other situations, like grammar drills or practice conversations.

The limitations of this study directly inform several promising avenues for future research. The most critical next step is to move beyond simulation and validate the framework through human-in-the-loop experiments, beginning with small-scale pilot studies to assess the agent’s efficacy with real learners. These kinds of research would also let us substitute our simple proxies with rich, real-time multimodal data, like eye-tracking or other biosensors, to provide a better picture of cognitive states. Another area that should be addressed in future work is a much broader expansion of the action space, primarily with more diverse and nuanced pedagogical interventions, including dynamically varying the difficulty of exercises, switching the learning modality, or offering various types of explanatory feedback. To expand on this, it is proposed that researchers consider the use of continuous action spaces to enable a more detailed control over interventions, e.g., by letting the agent control the delay at which to give a hint. Lastly, the generalizability of the framework also needs to be validated by using the framework in a wider variety of language learning activities, such as grammar tasks, reading comprehension, interactive dialogue, and so on, to come up with more robust and universally applicable adaptive learning agents.

Conclusion

The new framework of adaptive language training presented in this paper combines cognitive and multimodal feedback as a part of an RL model. We were able to design and train a PPO-based agent in a simulated learner environment, showing that it was able to learn an effective pedagogical policy on its own, which was much more effective than typical heuristic and random baselines. The agent made data-driven pedagogical choices and utilized the hybrid state representation based on semantic knowledge of the language task and proxies of the cognitive state of the learner.

Two important findings were made as a result of the research. To begin with, the emergent strategy of the agent that developed out of the preference toward hints and culminated in the almost exclusive application of the former to prompt the learner to repeat the task shows the promise of the RL to find the means of instruction that would be less obvious but far more effective in the long term and would not be based on the seemingly beneficial but rather expensive short-term teaching interventions. Secondly, and most importantly, our ablation experiment gave clear-cut results that the cognitive-behavioral signals were not just compensatory, but they were also a necessary element of successful learning. The agent without this multimodal input did not do any better than a random agent, failing. The main contribution that we make, then, is to show that an RL agent can successfully use a hybrid cognitive-linguistic state representation to autonomously learn a strong and adaptive teaching policy. Moreover, our association study (Fig. 13) validated that no one cognitive-behavioral signal had a high link with the ultimate episodic reward. This discovery strongly underscores the imperative for sophisticated models such as our PPO agent, capable of discerning non-linear correlations from the comprehensive state vector, instead of depending on simplistic, single-signal heuristics.

Although this study can be considered a successful demonstration of the possibility, its limitations outline the necessary directions for future research. Its main weakness is that it is based upon a simulated learner environment; although useful in fast prototyping, the simulated signals are a simplification of real human behavior. Moreover, the action space was purposely made in a simple and discrete form, which fails to reflect the entire variety of pedagogical interventions that can be used in a real tutoring situation. Lastly, the only language task, which was validated by the framework, was translation, and the best policy that was found might not apply to other learning situations.

These restrictions are headed toward work in the future. The next most serious step is to not just get out of simulation but test the framework using human-in-the-loop experiments to test its practical effectiveness. Further refinements should also be made to the action space by adding more varied interventions, like changing the level of difficulty of the exercise, and by considering continuous action spaces to provide more precise control over feedback. Finally, the strength of the framework needs to be tested by implementing it in a wider variety of language learning activities, such as grammar exercises and conversation practice. To sum up, this study establishes a solid ground. It is a practical approach to designing the future of the truly personal and adaptive educational technologies that would be developed through a hybrid of simulation and specific human testing.

Data availability

All trained and tested data are presented in the article. Further details are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding authors.

References

Harrison, R. et al. Evaluating and enhancing quality in higher education teaching practice: A meta-review. Stud. High. Educ. 47(1), 80–96 (2022).

Jafari, N. et al. Design strategies to foster improved experiences for patients in rehabilitation. HERD Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 18, 111–124 (2025).

Flake, S. M. & Gabriel, K. F. Teaching Unprepared Students: Strategies for Promoting Success and Retention in Higher Education (Routledge, 2023).

Shahrokhi Kahnooj, H., Dadgar, H. & Saberi, H. Validity and reliability of the Persian version of the WH-Question comprehension test in children with autism. Appl. Neuropsychol. Child 13(2), 146–151 (2024).

Hilliger, I., Celis, S. & Perez-Sanagustin, M. Engaged versus disengaged teaching staff: A case study of continuous curriculum improvement in higher education. High Educ. Pol. 35(1), 81–101 (2022).

Martin, F., Chen, Y., Moore, R. L. & Westine, C. D. Systematic review of adaptive learning research designs, context, strategies, and technologies from 2009 to 2018. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 68(4), 1903–1929 (2020).

Koujel, N. K. & Major, J. C. An exploration of the intersectional distribution of physical, social, and emotional resources in engineering. In 2024 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE), 1–9 (IEEE, 2024).

Koujel, N. K. & Major, J. C. An examination of the gender gap among Middle Eastern students in Engineering: A systematized review. In 2025 Collaborative Network for Engineering & Computing Diversity (CoNECD) (2025).

Tisza, G., Sharma, K., Papavlasopoulou, S., Markopoulos, P. & Giannakos, M. Understanding fun in learning to code: A multi-modal data approach. In Proceedings of the 21st Annual ACM Interaction Design and Children Conference, 274–287 (2022).

Sibley, L. et al. Adaptive teaching with technology enhances lasting learning. Learn. Instr. 99, 1 (2025).

Panuganti, S., Koujel, N. K. & Major, J. C. The role of undergraduate engineering students’ different support networks in promoting emotional well-being: A narrative study. In 2025 Collaborative Network for Engineering & Computing Diversity (CoNECD) (2025).

Al-Zahrani, A. M. & Alasmari, T. Learning analytics for data-driven decision making: Enhancing instructional personalization and student engagement in online higher education. Int. J. Online Pedagogy Course Des. (IJOPCD) 13(1), 1–18 (2023).

Liang, J. et al. Student modeling and analysis in adaptive instructional systems. IEEE Access 10, 59359–59372 (2022).

Deldadehasl, M., Karahroodi, H. H. & Haddadian Nekah, P. Customer clustering and marketing optimization in hospitality: A hybrid data mining and decision-making approach from an emerging economy. Tour. Hosp. 6(2), 80 (2025).

Khadem-Reza, Z. K., Lashaki, R. A., Shahram, M. A. & Zare, H. Automatic diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders in children through resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging with machine vision. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 15(6), 4935 (2025).

Cloude, E. B., Azevedo, R., Winne, P. H., Biswas, G. & Jang, E. E. System design for using multimodal trace data in modeling self-regulated learning. Front. Educ. 7, 928632 (2022).

Jeong, J., Lee, J. H., Karahroodi, H. H. & Jeong, I. Uncivil customers and work-family spillover: examining the buffering role of ethical leadership. BMC Psychol. 13(1), 723 (2025).

Sun, D. et al. A university student performance prediction model and experiment based on multi-feature fusion and attention mechanism. IEEE Access 11, 112307–112319 (2023).

Sedghi, M., Zolfaghari, M., Mohseni, A. & Nosratian-Ahour, J. Real-time transient stability estimation of power system considering nonlinear limiters of excitation system using deep machine learning: An actual case study in Iran. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 127, 107254 (2024).

Mohseni, A., Doroudi, A. & Karrari, M. Data mining based excitation system parameters estimation considering DCS and PMU measurements using cubature Kalman filter. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 30(11), e12619 (2020).

Wang, X., Yu, X., Guo, L., Liu, F. & Xu, L. Student performance prediction with short-term sequential campus behaviors. Information 11(4), 201 (2020).

Luo, Z. et al. A method for prediction and analysis of student performance that combines multi-dimensional features of time and space. Mathematics 12(22), 3597 (2024).

Daneshfar, F., Dolati, M. & Sulaimany, S. Graph clustering techniques for community detection in social networks, 81–100 (2025).

Daneshfar, F., Dolati, M. & Sulaimany, S. Semi-supervised and deep learning approaches to social network community analysis, 101–120 (2025).

Riedmann, A., Schaper, P. & Lugrin, B. Reinforcement learning in education: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-025-00494-6 (2025).

Mohseni, A., Doroudi, A. & Karrari, M. Robust Kalman filter-based method for excitation system parameters identification using real measured data. J. Energy Manag. Technol. 4(2), 39–48 (2020).

Mohseni, A., Doroudi, A. & Karrari, M. Excitation system parameters Estimation by different input signals and various Kalman filters. Electromech. Energy Convers. Syst. 2(2), 40–51 (2022).

Bassen, J. et al. Reinforcement learning for the adaptive scheduling of educational activities. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–12 (2020).

Nikzat, P. & Hosseinzade, S. A practical model to measure E-service quality and E-customer satisfaction of crypto wallets. Open J. Bus. Manag. 13(3), 1634–1660 (2025).

Raeisi, Z. et al. Enhanced classification of tinnitus patients using EEG microstates and deep learning techniques. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 15959 (2025).

Forney, A. & Mueller, S. Causal inference in AI education: A primer. J. Causal Inference 10(1), 141–173 (2022).

Mohseni, A. An improved unscented Kalman filter algorithm for dynamic systems parameters estimation. Res. Sq. (Res. Sq.) (2024).

Ghasemi, M. A., Mohseni, A. & Parniani, M. Enhanced scheme for allocation of primary frequency control reserve based on grid characteristics. Tabriz J. Electr. Eng. 51(2), 221–231 (2021).

Mohseni, A., Sedghi, M., Ravanji, M. H. & Lesani, H. Multiobjective retuning the power system stabilizer (PSS) of a real power plant in Iran grid (2020).

Wen, J. et al. Federated offline reinforcement learning with multimodal data. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 70(1), 4266–4276 (2023).

Raeisi, Z., Mehrnia, M., Ahmadi Lashaki, R. & Abedi Lomer, F. Enhancing schizophrenia diagnosis through deep learning: A resting-state fMRI approach. Neural Comput. Appl. 37, 15277–15309 (2025).

Zhu, Q., Lee, Y.-C. & Wang, H.-C. ActionaBot: Structuring metacognitive conversations towards in-situ awareness in how-to instruction following. In Proceedings of the 7th ACM Conference on Conversational User Interfaces, 1–20 (2025).

Lashaki, R. A. et al. EEG microstate analysis in trigeminal neuralgia: Identifying potential biomarkers for enhanced diagnostic accuracy. Acta Neurologica Belgica 125, 1025–1045 (2025).

Li, X. & Mahmoud, M. Interpretable concept-based deep learning framework for multimodal human behavior modeling. arXiv preprint http://arxiv.org/abs/2502.10145 (2025).

Raeisi, Z. et al. EEG microstate biomarkers for schizophrenia: a novel approach using deep neural networks. Cogn. Neurodyn. 19(1), 1–26 (2025).

Zerkouk, M., Mihoubi, M. & Chikhaoui, B. A comprehensive review of AI-based intelligent tutoring systems: Applications and challenges. arXiv preprint http://arxiv.org/abs/2507.18882 (2025).

Tariq, R., Aponte Babines, B. M., Ramirez, J., Alvarez-Icaza, I. & Naseer, F. Computational thinking in STEM education: Current state-of-the-art and future research directions. Front. Comput. Sci. 6, 1480404 (2025).

Zhu, B., Chau, K. T. & Mokmin, N. A. M. Optimizing cognitive load and learning adaptability with adaptive microlearning for in-service personnel. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 25960. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77122-1 (2024).

Naseer, F., Tariq, R., Alshahrani, H. M., Alruwais, N. & Al-Wesabi, F. N. Project based learning framework integrating industry collaboration to enhance student future readiness in higher education. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 24985. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10385-4 (2025).

Tong, C. & Ren, C. Deep knowledge tracing and cognitive load estimation for personalized learning path generation using neural network architecture. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 24925. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10497-x (2025).

Naseer, F., Khan, M. N., Addas, A., Awais, Q. & Ayub, N. Game mechanics and artificial intelligence personalization: A framework for adaptive learning systems. Educ. Sci. 15(3), 301 (2025).

Schmucker, R., Pachapurkar, N., Bala, S., Shah, M. & Mitchell, T. Learning to optimize feedback for one million students: Insights from multi-armed and contextual bandits in large-scale online tutoring. arXiv preprint http://arxiv.org/abs/2508.00270 (2025).

Scarlatos, A., Liu, N., Lee, J., Baraniuk, R. & Lan, A. Training LLM-based tutors to improve student learning outcomes in dialogues. In International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education, 251–266 (Springer, 2025).

Sharma, P. & Li, Q. Designing simulated students to emulate learner activity data in an open-ended learning environment. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Educational Data Mining, 986–989 (2024).

Helsinki-NLP. The Tatoeba Translation Challenge (v2023-09-26) [Online] Available: https://github.com/Helsinki-NLP/Tatoeba-Challenge.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Project administration, funding acquisition, supervision, methodology, resources, software, writing review—editing, visualization: H.F.I., P.G.; Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, validation, visualization, writing original draft preparation, H.F.I., L.C., Z.W. This manuscript has been read and approved by all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Che, L., Guo, P., Isleem, H.F. et al. The necessity of multimodal feedback for learning effective pedagogical policies with reinforcement learning. Sci Rep 16, 454 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29892-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29892-5