Abstract

The rapid advancement of Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) sequencing technology has gained more attention, especially in interpreting high-dimensional, low-sample-size microarray data for disease identification. However, conventional gene selection techniques struggle to identify optimal biomarker subsets from gene data within a feasible time. To address this, we propose a novel hybrid method for robust cancer classification and biomarker discovery. To reduce the dimensionality of gene data while preserving biologically meaningful patterns, in the first stage of our approach, Kernel Principal Component Analysis (KPCA) is utilized. The refined gene subsets are then processed by the Multi-Population Gravitational Search Algorithm (GSA) known as MPKGSA with Opposition-Based Learning (OBL). The hybridization mechanism involves using OBL to generate a set of opposite solutions for each population, which is then integrated into the GSA update process. This process provides a more diverse exploration of the search space, preventing premature convergence on suboptimal gene subsets. The effectiveness of MPKGSA was evaluated on six microarray cancer datasets and a breast cancer single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) dataset from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). Numerical results demonstrate that MPKGSA excels at balancing convergence and diversity, achieving high prediction accuracy with minimal biomarker subsets. Furthermore, it outperformed existing meta-heuristic methods, selecting a small number of gene biomarkers strongly correlated with the biological response class, confirming its utility for precise cancer identification and classification.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The human genome is the full set of deoxyribonucleic acid sequence for humans. It consists approximately three billion base pairs in the double helix of DNA, more than 99% of them are the same among all populations, and less than 1% differ among individuals. The majority of DNA changes happen as Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs). SNPs are the most important markers used for mapping diseases/cancers with genes. Over the past few years, microarray technology has been commonly used to measure the expression levels of thousands of genes simultaneously in a single experiment and analyze them to extract relevant genes to different areas of cancer types1. Gene expression profiles represent the abundance of messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) corresponding to specific genes2. Therefore, microarray technology has become a revolutionary tool for understanding human diseases. As a response, the rapid development and maturation of microarray technology allow researchers to measure the expression profiles of thousands of genes for discovering molecular disease biomarkers and aiding cancer diagnosis. To solve several issues like high-dimensionality, small sample size and noise, researchers have developed novel models that were effective and efficient for differentially expressed genes and for predicting the class of unknown samples3,4. The majority of high-dimensional gene expression data contains a significant amount of redundant genes, posing challenges for machine learning algorithms due to their high dimensionality. So, gene selection has been shown to be a successful method for improving performance by addressing several objectives, such as reducing the number of features and improving classification accuracy5.

In the field of bioinformatics and precision medicine, high-dimensional data generated by high-throughput technologies can significantly impact medical diagnosis models6. Accurate cancer-type screening is critical for effective cancer identification and targeted treatment selection. To remove unnecessary genes from microarrays and retrieve useful information, several feature selection (FS) technique is applied7 to classify the cancer accurately. However, identifying relevant genes from tumors data is challenging due to the presence of redundant or irrelevant genes. However nature-inspired algorithms have shown promising results for selecting predictive genes8 in comparison with other gene methods. To alleviate this situation and enhance the confidence of microarray data analysis, an evolutionary optimized diverse ensemble learning framework was introduced in Ref.9, which improved cancer classification performance on gene expression datasets.

Due to the vast search space, feature selection has become a critical task in modern bioinformatics, focusing on identifying important characteristics while eliminating redundant or irrelevant ones10. To address problems in microarray data, there are many challenges, such as sparsity of gene data, complicated data processing, and increased risk of overfitting, that are faced during predictive modeling on microarray data. Generally speaking, Feature selection (FS) plays a vital role in reducing the dimensionality of microarray datasets by selecting a subset of significant features from the original feature space based on their discriminative capability11. High False Positive Rate (FPR), often associated with classical methods, represents a significant drawback in tumor detection. To effectively reduce the dimensionality, principal component analysis (PCA) is used to identify relevant features with low FPR and high accuracy, which is highly desirable in order to handle high-dimensional data problems12.

Groundbreaking study of author13 used the opposition-based learning (OBL) technique to enhance the efficacy of metaheuristic optimization algorithms, resulting in preventing slow convergence, susceptibility to overfitting, and convergence towards local minima. In OBL, candidate solutions from a stochastic iteration scheme are paired with their opposing solutions, which are located in different regions of the search space and are closer to the global optimum than random solutions14. Generally speaking, feature selection methods are classified into four types: filter, wrapper, hybrid, and embedded15. In most cases, exhaustively searching for the optimal subset of features within a data set is nearly impossible. Recent literature has explored various wrapper techniques, including random, heuristic, and iterative search methods, for feature selection16. However, most existing FS techniques suffer from high computational costs and stagnation in local optima17. Conventional methods struggle to handle the large number of features in high-dimensional datasets. To effectively reduce data dimensionality, researchers have incorporated additional specific fitness functions into search algorithms for feature selection. To minimize features in high-dimensional datasets, some researchers have employed metaheuristic-based FS techniques such as Gravitational Search Algorithm (GSA), Ant Colony Optimization (ACO), Artificial Bee Colony (ABC), Genetic Algorithm (GA) and Correlation-based Feature Selection with particle swarm optimization for tumor cancer/tumor classification18.

To address the aforementioned challenges and to improve diversity preservation, the gravitational search algorithm (GSA) is a straightforward and powerful optimization algorithm that maintains population diversity and enhances solution diversity for gene selection19. Researchers have employed GSA as a wrapper method for gene selection to address existing limitations20. To further explore GSA’s variants in gene selection, an investigation of multi-population mechanisms called the multi-population gravitational search algorithm (MPGSA) has been developed. Consequently, MPGSA effectively identifies irrelevant genes, preserves population diversity through rapid convergence, and maintains a robust balance between global and local search capabilities.

Contributions

Although many existing metaheuristic algorithms yield impressive results on specific microarray datasets, few consistently perform well across diverse challenges21. To enhance the efficiency and predictive accuracy of selected feature subsets, our approach first pre-processes the feature space using principal component analysis to eliminate redundant and weakly correlated features before applying the multi-population gravitational search algorithm (MPGSA) based on the opposition-based learning (OBL) strategy. Secondly, in order to avoid local optima during optimization, the MPGSA algorithm employed an information-sharing mechanism in sub-populations for the diversity of solutions. Additionally, we employ an individual enhancement technique to optimize performance by classifying individuals in each sub-population into three layers. By integrating gene selection techniques with learning approaches, this method improves understanding of biological domains. Also our method is evaluated on a genomics data publicly available on the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). The main contributions of this study, outlined below, address the stagnation problem inherent in conventional optimization approaches:

-

This paper introduced the KPCA strategy to strengthen the diversity of the gene subsets of the algorithm, which effectively removes noisy genes from the initial feature space.

-

To improve solution diversity, opposition-based learning (OBL) and multi-population (MP) mechanisms are integrated into GSA to reduce the probability of the algorithm falling into local optima.

-

Additionally, the integration of kernel PCA and MPKGSA boosts exploration and improves the performance of gene data sets to increase processing speed, reduce predictive error, and prevent incomprehensible and misleading data knowledge.

-

By the help of support vector machine classification, a new fitness function is introduced. Additionally, compared to other SVM variants, it is discovered that the MPKGSA approach with SVM-R performs the best, achieving a high rate of accuracy and sensitivity.

-

Moreover, to assess the microarray performance of MPKGSA determines the best gene subset in terms of accuracy and number of genes on the six microarray datasets and GEO data include GSE16619 series.

In the proposed method, the OBL approach is used to increase the diversity of feature subsets. Then, we thoroughly assessed the performance of MPKGSA on several gene datasets. The article structure is as follows: A quick overview of the various evolutionary algorithms in the literature survey is given in “Literature review” section. The existing feature selection method based on metaheuristics is discussed in “Design and implementation of proposed method” section. Our wrapper algorithm for feature selection is compared with the support vector machine (SVM) strategy for six microarray datasets in “Experimental analysis and discussion” section, which is followed by a conclusion in “Conclusion” section.

Literature review

High dimensionality is a significant characteristic of microarray data. Nonetheless, it may result in a decline in the efficacy of ML-based models. Dimensionality reduction may serve as a novel way to address challenges associated with high-dimensional features. Stability in feature selection is a challenging issue16. Although many feature selection methods for microarray studies have been out, their performances on microarray data have not been carefully evaluated. Therefore, wrapper-based feature selection results are strongly influenced by the underlying data distribution, sample size, and feature selection technique mechanisms22.

From Ref.23, motivated to develop a novel hybrid multi-population adaptive genetic algorithm that can correctly identify cancer while ignoring the genes that are not important. There were two stages to the hybrid algorithm. In the first stage, multi-layer and F-score techniques were combined to create an ensemble gene selection method that filters out redundant and noisy genes in high-dimensional datasets. Then, in order to find the high-risk differential genes, a wrapper was created using a multi-population adaptive evolutionary algorithm that used naive Bayes classifiers and support vector machines as objective functions. Ten microarray sub-population datasets representing a wide variety of tumor types were used to assess the effectiveness of the author’s method. Additionally, the comparative tests showed that the hybrid approach worked better in terms of classification accuracy with an ideal number of genes than a variety of cutting-edge wrapper and filter techniques.

Recent research has attempted to mitigate this high dimensionality through the application of diverse feature selection strategies. From Ref.24 study introduced novel ensemble feature selection methodologies utilising the Wilcoxon Signed Rank Sum test (WCSRS) and Fisher’s test (F-test). Data preprocessing was conducted in the initial phase of the trial. Subsequently, feature selection was conducted using the WCSRS and F-test, whereby the p-values from both the WCRSR and F-test were utilised for the identification of carcinogenic genes. The collected gene set was employed to categorise cancer patients via ensemble learning models, including extreme learning machines, random forest, extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost), CatBoost, and AdaBoost. We enhanced the performance of the ELM by optimising the settings of all ELMs via the Grey Wolf optimiser. The experimental investigation was conducted on colon cancer, encompassing 2000 genes from 62 people. The optimised XGBoost exhibited 100% accuracy while employing a WCSRS test for feature selection. The optimised CatBoost, conversely, exhibited 100% accuracy utilising the F-test for feature selection. This signifies a 15% enhancement compared to previously documented values in the literature.

From Ref.25 method used a cellular learning automaton that adaptively regulated its update schemes to modify the behavior of each sub-population. An evolving population may experience many state transitions as the environment changes. A modified evolutionary method for one state might not be appropriate for the next, since each state requires different qualities from an optimizer. Additionally, because environmental changes occur often, a learning strategy may not have enough time to adjust to a newly encountered situation. As a result, the dynamic optimizer cannot unlearn its preexisting beliefs to support the behaviors needed to accept newly encountered states. To tackle this problem, we present a context-dependent learning strategy that can modify each sub-population behavior based on the circumstances of its various states. The proposed method’s performance was evaluated against several cutting-edge dynamic optimizers using the GDBG benchmark set.

Current methodologies frequently focus on a singular purpose or address gene selection and categorisation separately, thus constraining their overall efficacy. In Ref.26 introduced a cohesive framework called MORPSO_ECD+ELM Gene selection and classification are framed as a multimodal multiobjective optimisation problem to concurrently optimise both objectives. The framework presents two principal innovations: an enhanced crowding distance metric to augment diversity preservation and an advanced multi-objective particle swarm optimisation variant (MORPSO_ECD) that integrates ECD and ring topography to efficiently navigate the MMOP solution space. Designed system together with the Extreme Learning Machine, accomplishes robust and efficient cancer categorisation. Comprehensive experimental validations indicate that the suggested method attained elevated classification accuracy while discerning biologically relevant gene subsets, offering a robust strategy to connect gene selection with cancer classification.

The research proposed a multiple kernel learning (MKL) integrated multi-objective swarm intelligence method to find prospective biomarker genes from the transcriptome profiles of arsenicosis data27. A multi-objective random spatial local best particle swarm optimisation (MO-RSplbestPSO) has been employed to get optimal classification accuracy while minimising the number of genes. The suggested MO-RSplbestPSO additionally directs the multiple kernel learning method, facilitating data-specific categorisation. The proposed computational framework has been utilised on the generated whole-genome DNA microarray created from blood samples obtained from a designated arsenic-exposed region in the Indian state of West Bengal. A collection of twelve biomarker genes, including four unique genes, has been effectively found for the classification of arsenic exposure and its subcategories, which may serve as future predictive biomarkers for screening arsenic-exposed populations. The biological importance of each gene is elaborated to clarify the intricate molecular networking and mechanism of toxicity.

By Ref.28, the Binary HOA and BHOA-CM, an enhanced version, were examined. By altering their pace in reaction to the slope of the ground, HOA successfully climbs mountains by imitating hikers’ adaptive behaviour. Continuous values were transformed into binary outputs using a hyperbolic tangent transfer function. In order to enhance the algorithm’s ability to exploit gene selection, BHOA-CM combined one-point crossover and self-adaptive mutation operators. Differential Expressed Genes analysis was the first step in finding pertinent genes. BHOA and BHOA-CM were employed with a hybrid classifier that integrated Adaptive Sparse Partial Least Square and Logistic Regression in order to optimise gene selection performance. Experimental results on six benchmark microarray datasets showed that the author’s strategy outperformed recent state-of-the-art strategies in classification accuracy while selecting fewer marker genes.

In Ref.29, a method was developed to create a dual-angle feature for single-modal gene data to enhance efficacy and robustness, addressing the challenge of high-dimensional tumour classification. The proposed framework comprises three components: Deep matrix factorisation, double-angle decomposition, and feature purification. A robust deep matrix factorisation model was suggested for feature learning to improve classification stability and achieve superior features in the presence of noisy data. Secondly, the double-angle feature (RDMF-DA) was constructed by cascading the RDMF features with sparse features, hence including more complete information within gene data. Third, to mitigate the impact of redundant genes on representation capability, a gene selection technique was given to refine the features using RDMF-DA, grounded in the principles of sparse representation and gene coexpression. The suggested technique was ultimately applied to gene expression profiling datasets, and its performance was thoroughly validated.

Combining different algorithms to determine the most efficient method of SNP data processing is the primary objective of Ref.30. As a result, an effective technique is put forth to classify sick and healthy samples and find important SNPs. First, in this context, the nominal SNP data is converted to numeric using Mean Encoding, an intelligent technique. The redundant and unnecessary features are then eliminated by feature selection using a two-step filter approach. Lastly, classification is done using the suggested deep auto-encoder, which automatically builds its structure from input data. We use five distinct SNP datasets—thyroid cancer, mental retardation, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, and autism—obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) dataset to assess the suggested methodology. With 100%, 94.4%, 100%, 96%, and 99.1% accuracy, respectively, the suggested method has been successful in feature selection and classification, allowing it to classify healthy and sick samples based on specific features in thyroid cancer, mental retardation, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, and autism. When compared to previous published efforts, the results show that it has achieved excellent efficiency.

To solve the stagnation problem, Ref.31 presented two new migration policies in a multi-population version of the kidney-inspired algorithm (KA). The first algorithm, MultiPop-KA, carried out a preset migration policy. On the other hand, the second algorithm, AutoMultiPop-KA, used an adaptive migration policy selection procedure that chooses the kind of migration depending on the average fitness of sub-populations. These strategies seek to improve the KA efficacy by leveraging a multi-population framework and combining two migration policies to attain a more sophisticated balance between exploration and exploitation. The effectiveness of suggested methods was demonstrated by experimental assessments applied to 18 benchmark feature selection problems and completed across 25 test functions. These findings suggest that the AutoMultiPop-KA strategy can greatly improve the overall quality and performance of optimization algorithms.

Design and implementation of proposed method

Many gene selection algorithms based on DNA datasets are used today32. To overcome the drawbacks of rule-based systems, many gene datasets employ meta-heuristic techniques in examining large DNA data structures to identify identifiable patterns or models33. Additionally, effectively identifying patterns of regular activity to spot irregularities, extracting DNA sequences to spot misuse, and developing classifiers to spot tumor/cancer types are all possible with machine learning. More adaptability and deployment ability may be possible with nature-inspired methods34. Instead of finding the optimal optimization solution, these algorithms seek to find one reasonably excellent. So, in this study, a new variant of GSA meta-heuristic algorithms is utilized. Additionally, the majority of researchers have thought of a promising and successful wrapper technique for choosing feature subsets that are optimal or nearly optimal, including Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)35, TLBO36, DE37, Genetic Algorithm (GA)38. Gravitational Search Algorithm (GSA)39.

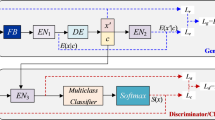

To address the above issues, we propose a wrapper-based feature selection method based on KPCA and MPGSA while OBL is utilised to boost population diversity. Combining Kernel PCA model with multi-population GSA algorithm is used to enhance search efficiency and avoiding local optima stagnation. The KPCA approach reduces the high dimension of the gene datasets in the first stage of the search process, while OBL is utilised to boost population diversity when populations are generated by GSA. In used gene datasets, the variance of each of the original attributes is computed in order to evaluate the eigenvalues and eigenvectors. The second step of the gene selection procedure, MPKGSA, uses the created multi-population wrapper feature selection. The number of characteristics was decreased with the KPCA method. Once more, the MPGSA feature selection method is used to decrease features. The second phase uses the SVM-R classifier to identify the different forms of cancer or tumours. Figures 1 and 2 display the framework for our gene selection model.

Opposition-based learning (OBL)

The concept of opposition-based learning (OBL) was first proposed in 200540. Since then, OBL has been widely applied to improve the performance of metaheuristic algorithms, reinforcement learning, and other machine intelligence techniques. Using OBL to help a metaheuristic optimisation algorithm locate the global optimum is the primary objective of this work. Usually, a metaheuristic starts with a population that is generated at random and updates the current solutions in an interactive manner. OBL is used to create the opposite of the present answer. After that, OBL compares the current solution to the corresponding opposing solution and retains the better one. Therefore, OBL may facilitate the discovery of optima and accelerate the convergence of the meta-heuristic algorithm. Suppose that x is a real number that belongs to the interval [u,l]; the opposite value of several x is defined as:

where \(u_N\) and \(l_N\) are the upper and lower values of the feature selection, respectively. For higher-dimensional micro-array, let \(x=(x_1,x_2,...,x_N)\) belongs to \(R_N\) be a N-dimension matrix, where \(x_i\) belongs to \([u_i,l_i]\) , i=1,2,...,N . The opposite vector \(\bar{x}\) can be defined as:

where \(\bar{x}\) = \(u_i + l_i- x_i\) , i=1,2,...,N . Furthermore, if x is a binary matrix, \(x=(x_1,x_2,...,x_N)\) belongs to (0,1) , then \(u_i\)=1 , \(l_i\)=0 . Thus, in binary space, the opposite vector of x is defined as:

Kernel-principal-component-analysis

Despite the limitations, PCA is still a powerful method for data analysis, visualization, and dimensional reduction41. Because of numerous modifications were developed to overcome its drawbacks and broaden the scope of applications. Kernel principal component analysis, or PCA, is a nonlinear generalization of PCA using kernel methods, also known as the “kernel trick. The main idea is to map the original data non-linearly into a feature space Fe by

and then perform PCA, which implicitly defines nonlinear principal components in the original data space. Even if Fe has an arbitrarily large dimension, for certain choices of \(\delta\), it is still possible to perform PCA in Fe.

Consider a microarray data set X containing S tissues of D biomarkers \((D < S)\) and a non-linear transformation \(\delta (x)\) into an N-dimensional feature space Fe. For now, let us assume that projected gene datasets are centered, so \(\dfrac{1}{S}\sum _{n=1}^{S}{\delta (x_n)}=0\). The \(M \times N\) covariance matrix in feature space is given by

We need to solve the following eigenvalue problem

\(i=1,...,N\). Our goal is to solve this equation without working directly in the feature space as, due to its size, this will be computationally inefficient. Substituting Co from (2) we get

Provided \(\lambda _i > 0\), the vector \(v_i\) is given by a linear combination of the \(\delta (x_n)\) and so \(\forall \ i \ \exists\) column vector \(\varvec{\alpha }_i \in R^S\) such that:

Substituting (2) and (5) into (3), we obtain

The key thing here is to express last equation in terms of kernel function defined as \(k(x_n, x_m) = \delta (x_n)^T\delta (x_m)\). It is done by multiplying both sides by \(\delta (x_l)^T\) which results to the next:

or in matrix notation

If we remove a factor of K from both sides, we obtain the following eigenvalue problem

By solving the problem,m we find eigenvectors \(\varvec{\alpha }_i\). Note that solutions of (8) and (9) differ only by eigenvectors that correspond to zero eigenvalues of K, hence removing K from both sides of (8) does not affect principal components.

So far, we assumed that the projected data set has zero mean. But in general, it will not be the case. The standard way to centralize a data set is to compute the mean and subtract it from every data point. Here, we wish to avoid working in feature space and express everything regarding kernel function. Let’s denote the projected data set after centering as \(\widetilde{\delta }(x_n)\).

and the corresponding elements of the Gram matrix

or in a matrix notation

where \(\widetilde{K}\) is centered kernel matrix, \(1_S\) is \(S \times S\) matrix in which every element equals to \(\dfrac{1}{S}\)42. So, we can evaluate \(\widetilde{K}\) using only the kernel function.

After solving the eigenvalue problem \(\widetilde{K}\varvec{\alpha }_i = \lambda _i S \varvec{\alpha }_i\), We can find projections of principal components in terms of kernel function. Using (5), projection of a point x onto eigenvector i is given by

Note that neither (3) nor (13) requires the \(\delta (x)\) in explicit form, we only need their dot product to use kernel function without actually performing the map \(\delta\).

Kernel principal component analysis (KPCA) provides a powerful nonlinear dimensionality reduction approach for gene expression analysis. Given a microarray dataset \(X = \{x_1, x_2, \ldots , x_n\} \in \mathbb {R}^d\) where n is the number of samples and d is the number of genes, KPCA transforms the data while preserving complex gene interactions.

where \(\phi\) maps the gene expression vectors to a higher-dimensional feature space \(\mathscr {F}\) implicitly defined by the kernel function \(k(x_i,x_j) = \langle \phi (x_i), \phi (x_j) \rangle\). The algorithm begins by constructing the kernel matrix \(K \in \mathbb {R}^{n \times n}\):

Common kernel choices for gene expression data including Radial Basis Function (RBF), Polynomial Kernel. The kernel matrix is centered to remove biases:

where \(1_n\) is an \(n \times n\) matrix with all elements equal to \(\frac{1}{n}\). This step ensures the data has a zero mean in the feature space. KPCA solves the eigenvalue problem:

The eigenvalues \(\lambda _i\) are sorted in descending order, and the top m eigenvectors corresponding to the largest eigenvalues are selected. Each eigenvector \(v_i\) represents a principal component in the feature space. The gene expression data is projected onto the new feature space:

where \(\alpha _j\) is the j-th component of the eigenvector. The transformed dataset \(Z = \{z_1, z_2, \ldots , z_n\} \in \mathbb {R}^m\) captures the most biologically relevant variations in the gene expression data.

The combination of KPCA with the multi-population evolutionary algorithm enables efficient search for optimal gene subsets in the transformed feature space. This approach is particularly effective for identifying small biomarker panels from thousands of genes, discovering nonlinear gene interactions that affect disease phenotypes, and improving classification performance while maintaining biological interpretability.

Multi-population scheme

Several multi-population methods have been implemented into evolutionary algorithms to solve numerous problems to improve the searchability of EAs43. Inspired by biological/natural evolution processes. firstly, this method decomposes the initial population in multi-population into several small sub-populations. Then, these sub-populations are evaluated in parallel using GSA. Finally, to find optimal solutions, different sub-populations collaborate to search other local areas.

The size of the population can significantly influence the average calculation time of EAs, transforming exponential time into polynomial time under certain circumstances. Studies have revealed that introducing a population can enhance the first striking probability44,45. Therefore, adjusting the population size to an appropriate value is advisable to minimize calculation time and improve the striking probability. A practical approach to managing population size, which reduces calculation time without compromising diversity, involves dividing a large initial population into multiple smaller sub-populations and performing parallel executions. The prevailing research literature presents two primary approaches. The first approach involves a multi-population scheme, where each sub-population follows a distinct strategy. However, one specific sub-population maintains the same search strategy throughout the process. The second approach is a single population scheme incorporating multiple strategies and parameters. A set of parameters is selected as the current parameters based on specific rules. This approach frequently switches between multiple evolutionary strategies, with each evolution using only one strategy46. It is possible to adjust the algorithm parameters to leverage parallel computing and reduce computational time to ensure compatibility with parallel processing. With this in mind, the algorithm proposed in this study divides the entire population into equal N sub-populations. Each subpopulation size is set to Pop/N, and mutation strategies and control parameters are applied. Notably, Pop’s overall population size remains, thereby preserving population diversity and preventing premature convergence, as seen in Fig. 2.

Information exchange scheme

In this study, we have utilized cross-sub-population migration as an information communication scheme that replaces solutions based on the solution quality implemented by probabilistic choosing31. Then, we find the pairs of sub-populations suitable for migration based on the levels of sub-populations. We use the distance levels to decide which sub-populations to migrate to or from Ref.47. The rationale behind this approach is that sub-populations exhibiting higher fitness distance are more likely to benefit from migration than those with lower distance. Once the pair of sub-populations to migrate from is determined, we can calculate the distance between the solution being replaced, and then the sub-population will be selected. The utilization of distance is rooted in diversity, recognizing that a more diverse population offers increased opportunities for discovering optimal solutions.

Gravitational search algorithm

Gravitational search algorithm (GSA) is a nature-inspired metaheuristic optimization technique that mimics Newton’s law of gravitation to solve complex feature selection problems in high-dimensional genomic data48. In GSA, candidate solutions (gene subsets) are treated as masses in a search space, where their fitness determines their gravitational attraction. Higher-quality solutions exert stronger forces on others. Every agent is also attracted to every other agent. Newton’s universal law of gravity is used to calculate the gravitational force of each element, and Newton’s rule of movement is used to calculate the speed of each factor. The agents can scan the search space for the best answers after applying the gravitational force. GSA has a number of advantageous characteristics over other evolutionary systems, including ease of usage, reliable performance, and fewer tweaking limitations. The method skips over each mass randomly generated value throughout the whole search space in a system with pop agents. The gravitational forces (F) from agent j on agent i at a specific moment \(t_0\) are defined by Eq. (14) as the learning duration.

\(M_{aj}^{t_0} \!\!~\!\!\;\;\) represents the active gravitational mass connected with pop j, whereas \(M_{pi}^{t}\) represents the passive gravitational mass associated with pop j. The Euclidian distance between two agents i and j is represented as \(\;\;\!\!~\!\;\;R_{i,j}^{t}\), i, \(G(t_0)\) is the gravity constant at time \(t_0\), and \(\phi\) is a small constant. The formula of \(Gr\left( t \right)\) is estimated using Eq. (15).

\({{G}_{0}}\) is set to 100, \(\textit{iter}\) displays the current iteration, and \(\aleph\) displays the maximum number of generations. The alpha value, which was obtained straight from49, is 20. Equation (16) is used to determine the total force acting on i.

where \(ran{{d}_{j}}\) indicates that the random number is in the range of 0 to 1. According to the law of motion idea, an agent’s acceleration is inversely proportional to its mass and relative to the resulting force; hence, Eq. (19) may be used to quantify the acceleration of all pops.

where \(ran{{d}_{j}}\) denotes the random value in the interval [0, 1], \(t_n\) denotes the precise time, and \(M_{i,i}^{t}\) denotes the mass of object i. First, GSA initializes all masses with random integers. Every mass serves as a potential solution. Equations (15)–(17) are used to determine accelerations, total forces, and the gravitational constant. We may update the gravitational and inertial masses using the equations above, as shown in Eqs. (18) and (19).

Equations (20) and (21) define worst (\(t_n\)) and best (\(t_n\)), while \(f_i (t_n)\) denotes the fitness value of the agent i at time \(t_n\).

where j=1,2,...,nPop. Additionally, an agent’s upcoming velocity is calculated as a proportion of its current velocity plus acceleration. Consequently, Eqs. (22) and (23) might be used to determine its position and velocity.

In the interval [0,1], \(rand_i\) is a uniform random variable. We give the search a randomized characteristic by using this random integer.

For biomarkers, to improve their population diversity in the search space, kernel principal component analysis (KPCA) and the MP-gravitational optimization algorithm, called MPKGSA, are introduced. Kernel principal component analysis is introduced for feature dimensionality to extract the most essential features. The obtained features are input for dimensionality reduction. The method’s overall performance can be improved by effectively transforming a multidimensional input set. The capacity to summarize the entire input. Then, MPKGSA incorporates a division of the entire population into sub-populations. This ground-breaking mechanism leverages chaos theory to promote efficient exploitation of potential local regions while effectively improving the quality of neighborhood structures and preserving population diversity. Additionally, the migration mechanism facilitates the sharing of valuable information among the sub-populations throughout the search process. Furthermore, integrating the differential evolution strategy into the GSA enhances the local search capabilities of the proposed variant. This integration boosts the GSA algorithm’s ability to explore local optima and significantly improves the overall quality of the generated solutions. The main aim is to strike a balance between exploitation and exploration. The entire procedure of our method is ascertained as follows:

-

Set up the GSA random population. The generated population, or Pop, is set to 90. GSA uses OBL to increase the population diversity of its search.

-

To initialise the population, use the binary encoding approach. The generated population is designated as such and represented in binary form. Each length may represent a few genes in the reduced dataset by use of encoding.

-

As shown in Fig. 1, divide the entire population into subpopulations.

-

Use the new fitness function to determine the fitness value for each population while taking accuracy into account.

-

After the first phase, choose a population with a high fitness value since the intelligent population is a target. Then, update the position value to create a new updated mass. Update the old pop according to the most recent population value. Determine the new pop fitness and compare it to the old pop. If the new pop fitness is lower, use MPKGSA solutions as a starting point to obtain the most recent, optimal solution.

-

Stay after if the most recent best fitness value satisfies the termination criterion; proceed to the preceding step.

-

The output is a subset of the SVM-based fitness and optimal gene.

In Algorithm 1, the Multi-Population Kernel Gravitational Search Algorithm (MPKGSA) combines kernel-based dimensionality reduction with an enhanced gravitational search metaheuristic for optimal biomarker selection from high-dimensional gene expression data. The algorithm operates through several key phases. The algorithm begins with opposition-based population initialization to enhance exploration:

where \(x_{i,j}\) represents gene j in solution i, and \(lb_j\), \(ub_j\) are the min/max expression values for gene j. Each solution’s mass \(M_i(t)\) at iteration t is computed based on fitness:

The gravitational force between solutions follows:

where \(G(t) = G_0e^{-\alpha t/t_{max}}\) controls the search intensity. Solutions update positions based on:

The population is divided into \({nsub_{pop}}\) subpopulations that evolve semi-independently. Top solutions \(\delta _i\) migrate between subpopulations:

Each \(x_i\) represents a candidate biomarker panel, Fitness \(\xi\) typically combines a fitness function based on Eq. (24). The gravitational metaphor naturally handles. The final output is the solution with maximal fitness across all runs, representing the most discriminative and parsimonious biomarker set.

Support vector machine

The support vector machine learning algorithm to address classification difficulties was proposed by Vapnik50. The kernel functions have drawn much attention in recent decades, especially as Support Vector Machines (SVMs) have become more and more prominent. Since the kernel (k) function offers a straightforward connection between linearity and non-linearity for algorithms that can be stated in terms of dot products, it can be applied to a wide range of situations. The problem can be solved in various ways, but in this publication, we have employed three SVM kernels extracted from the LibSVM tool51.

Kernel function and parameters of SVM

The primary learning algorithms have drawn much attention in recent decades, especially since SVM has become more widely used. Since the kernel (k) function provides a straightforward connection between linearity and non-linearity for algorithms that can be expressed in terms of dot products, it can be used in various applications. Three kernel functions that are formulated as follows will be listed in this article:

-

Linear function (SVM-L) \(k\left( {{R}_{i}}\;\;\!\!~\!\!\;,\;\;\!\!~\!\!\;\;{{R}_{j}} \right) =\left( {{R}_{i}}^{T}\text {* }\!\!~\!\!\;\;{{R}_{j}}+d \right)\).

-

Polynomial function (SVM-P) \(k\left( {{R}_{i}}\;\;\!\!~\!\!\;,\;\;\!\!~\!\!\;\;{{R}_{j}} \right) ={{\left( {{R}_{i}}^{T}\text {* }\!\!~\!\!\;\;{{R}_{j}}+d \right) }^{p}}\).

-

RBF function (SVM-R) \(k\left( {{R}_{i}}\;\;\!\!~\!\!\;,\;\;\!\!~\!\!\;\;{{R}_{j}} \right) =\;\;\!\!~\!\!\;\;exp\;\;\!\!~\!\!\;\;\!\!~\!\!\;\;\left\{ -\;\;\!\!~\!\!\;\;\frac{{{\left| {{R}_{i}}-{{R}_{j}} \right| }^{2}}}{2{{\sigma }^{2}}} \right\}\),

where d is a constant value, \({{R}_{i}}\) and \({{R}_{j}}\) are records or instances, and p is the order of function.

New fitness function

The best gene subsets identified by the fitness function alone may still contain potential duplication because the essential functions do not aim to restrict the number of biomarkers. We speculate that a similar classification accuracy can be obtained from a subset of less essential genes. A novel fitness function is being researched to lessen the number of genes and increase classification accuracy in order to get around the problem. The recently proposed fitness function is demonstrated by Eq. (24):

fit indicates the fitness value; \(\delta\) represents the classification accuracy by SVM; \(\theta\) measures the length of the chromosome; \(\beta\) represents the upper bound of a selected gene from the candidate solutions; and the constant \(\alpha\) value falls between 0 and 1.

Datasets description

Efficient datasets are required to assess the efficacy and dependability of any microarray program. In this paper, the evaluation of the Evolutionary techniques is carried out on six widely-used microarray datasets available in52,53. It is worth mentioning that all datasets have numerical features. The reason for choosing binary/multi datasets is that they are common in the literature. Table 1 summarize the properties of the datasets for each dataset, the number of features (#genes), classes, and number of samples (#instances). GSE16619 series54 includes SNP data related to BC with more than 500.000 SNPs. This study used 111 individuals, 69 as cases and 42 as controls.

There are two types of microarray datasets presented in the literature: binary class and multi-class datasets. In this study, we have used six gene expression datasets for different types of tumors/cancer. For example, the CNS dataset represents central nervous system embryonal tumors with 60 samples across 7129 gene expressions, classified into two distinct tumor types. This dataset contains gene expression profiles that typically distinguish between classic medulloepitheliomas and malignant gliomas or other CNS tumor variants55. The SRBCT dataset, containing 83 samples with 2308 gene expressions across four classes, stands as one of the most renowned benchmark datasets in cancer genomics, originally introduced by Ref.52. This dataset encompasses four morphologically similar but molecularly distinct tumor types: Ewing sarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and neuroblastoma, collectively known as small round blue cell tumors due to their similar microscopic appearance. The MLL dataset focuses on acute leukemias characterized by mixed lineage leukemia gene rearrangements, comprising 77 samples with 12,582 gene expressions distributed across three classes. This dataset typically represents acute lymphoblastic leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia, and mixed lineage leukemia subtypes, each requiring distinct therapeutic approaches.

The lung cancer dataset contains 181 samples with 12,533 gene expressions classified into two primary categories, representing the largest sample size among the datasets examined. This dataset typically distinguishes between major lung cancer subtypes such as adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, or alternatively between normal and tumor tissue samples. The substantial sample size provides better statistical power for machine learning applications, though the high dimensionality still necessitates robust feature selection methodologies to identify clinically relevant biomarkers. The ovarian cancer dataset represents the highest-dimensional challenge among all datasets, containing 253 samples with 15,154 gene expressions across two classes. This dataset, likely derived from Ref.56, typically focuses on distinguishing between normal and cancerous ovarian tissue or different stages and grades of ovarian malignancy. The combination of substantial sample size and extremely high dimensionality creates significant computational demands and requires sophisticated algorithms capable of handling large-scale genomic data efficiently. The leukemia dataset comprises 72 samples with 5327 gene expressions distributed across three classes for gene expression-based cancer classification. The three classes likely encompass acute lymphoblastic leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia subtypes.

Experimental analysis and discussion

In this experiment, the simulation model is built on MATLAB 2020a software. Different experiments have been carried out for GSA, current EA, and state-of-the-art gene selection methods. The proposed system is created using the Windows 10 operating system with 16 GB of RAM and an Intel i7 processor running at 2.4 GHz. Our work focuses on applying several methods that are inspired by nature. This section demonstrates the gene selection technique based on fitness functions and algorithms inspired by nature. Each optimization technique uses the fitness function to select the best characteristics. To decrease the number of characteristics and increase classification accuracy, a population size of 90 and several iterations of 100 in each bio-inspired technique can be seen in Table 2. The population size (Pop) of 90 solutions provides sufficient diversity to explore the vast search space of potential gene combinations. The algorithm runs for 100 generations, allowing adequate iterations to converge toward optimal gene subsets without overfitting to the training data, with this entire process repeated across 10 independent runs to ensure statistical reliability of the results. The chromosome length corresponds directly to the dimensionality (D) of the microarray dataset, enabling the algorithm to evaluate all potential genes during the evolutionary process. Performance evaluation uses classification accuracy as the fitness metric (Fit), directly optimizing the biological relevance of selected gene signatures for diagnostic of cancers. The inertia weight (\(\omega\) = 0.7) controls the momentum from previous iterations, balancing exploration of new gene combinations with exploitation of promising regions in the search space, while the gravitational constant \(G_0\) = 2048 appropriately scales the attraction forces between solutions to facilitate effective local search refinement. Selecting a limited number of significant qualities that improve classification performance is the main objective of feature selection. A confusion matrix that summarizes the number of samples that the classifiers correctly or erroneously predicted is used to assess the classifier’s performance, as seen in Tables 2 and 3.

Performance measures

A set of performance metrics is established to assess the effectiveness of the proposed technique and other EA techniques. These metrics, which include accuracy,Sensitivity, Specificity, F-measure and Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), are defined as follows:

We assessed the effectiveness of wrapper FS approaches using the six gene datasets, where TP, TN, FP, and FN stand for True Positive, True Negative, False Positive, and False Negative, respectively, based on the confusion matrix57.

Experimental results and analysis

The effectiveness of the suggested approach is demonstrated using the microarray gene expression data. For experimental purposes, microarray gene datasets are gathered from Ref.3. While the genes are organised in columns of the data matrix, the samples are maintained in rows during the experiments. A critical aspect of FS approaches is assessing the quality of the selected subsets, as seen in Table 4. The filter-based approach with learning algorithms should be included in the evaluation process. The evaluators consider the classification performance of the chosen features and converge in this study of wrappers, including SVM variants. The more relevant the desired qualities are, the higher the classification accuracy of a subset. Increasing classification accuracy is one objective of FS methods; reducing the number of selected attributes and fewer features in the solution is another essential objective.

In the other section of the experimental part of the study, we use tenfold cross-validation to assess our system performance. First, we explained the six data sets on DNA cancer that were used to determine the system’s effectiveness. As a result, existing traditional algorithms are compared and analyzed with the learning method. According to KPCA, we have selected the top 100 genes from the original gene dataset. To determine classification accuracy, we consider five distinct filter-based feature-selection methods, such as KPCA, MRMR, JMI, CMIM, and PCA, including without FS, as shown in Table 4. The comparative analysis of classification accuracy across six genomic datasets reveals distinct performance patterns when combining different Support Vector Machine variants with various feature selection methods. The results demonstrate that no single combination outperforms others across all datasets, indicating that the optimal approach is dataset-dependent and influenced by the underlying biological characteristics and data structure of each cancer type. The performance variations range from extremely poor results ( low for Ovarian cancer with SVM-P) to excellent classification accuracy (high for Lung cancer with SVM-R and KPCA), highlighting the critical importance of appropriate method selection for genomic data analysis. SVM-R demonstrates the most consistent and robust performance across the majority of datasets, achieving the highest accuracy scores in four out of six datasets. The Lung cancer dataset shows exceptional performance with SVM-R, reaching 94.83% accuracy when combined with Kernel Principal Component Analysis (KPCA), followed by 92.79% with Minimum Redundancy Maximum Relevance (MRMR) feature selection. This superior performance on lung cancer data suggests that the radial basis function kernel effectively captures the nonlinear relationships inherent in lung cancer gene expression patterns. The SRBCT dataset also responds well to SVM-R, achieving 91.96% accuracy with KPCA, indicating that the complex multi-class nature of small round blue cell tumors benefits from the non-linear mapping capabilities of the RBF kernel. However, SVM-R shows more modest performance on the CNS dataset, with accuracies ranging from 59.73 to 71.69%, suggesting that central nervous system tumor classification may require different analytical approaches or that the dataset’s small sample size limits the effectiveness of complex kernel methods. The polynomial kernel SVM variant exhibits highly dataset-specific performance patterns, with remarkable variation across different cancer types. Most notably, SVM-P does not show good performance on the Ovarian cancer dataset across all feature selection methods. This failure likely results from the polynomial kernel’s tendency to create overly complex decision boundaries that do not generalize well to the high-dimensional, sparse nature of ovarian cancer genomic data. Conversely, SVM-P achieves its best performance on the CNS dataset, reaching 88.89% accuracy with KPCA, suggesting that central nervous system tumor classification benefits from the polynomial kernel’s ability to capture specific types of feature interactions. The linear SVM variant provides moderate but consistent performance across most datasets, offering the advantage of model interpretability and computational efficiency. SVM-L achieves its highest performance on the SRBCT dataset, with JMI feature selection yielding 92.69% accuracy, demonstrating that the four-class small round blue cell tumor classification can be effectively handled through linear decision boundaries when appropriate feature selection is applied. The Lung cancer dataset also shows strong performance with SVM-L, reaching 89.83% accuracy when combined with KPCA, indicating that despite the complexity of lung cancer genomics, linear relationships between selected features can provide effective classification. The consistent moderate performance of SVM-L across datasets makes it a reliable baseline approach, particularly valuable in clinical applications where model interpretability is crucial for understanding the biological basis of classification decisions.

From Table 5, SVM-L achieves the best performance on the MLL dataset with 95.96% accuracy, complemented by sensitivity (92.96%) and F-measure (91.96%), indicating that the three-class MLL leukemia classification can be effectively handled through linear decision boundaries in the selected feature space. The SRBCT dataset also demonstrates strong linear separability with SVM-L achieving 96.95% accuracy. However, SVM-L shows some performance degradation in specific metrics, particularly evident in the Leukemia dataset, where the MCC drops significantly compared to sensitivity and specificity scores, and most notably in the MLL dataset, where the MCC score shows an anomalous value of 88.90%, likely indicating a computational or reporting error that warrants investigation. The polynomial SVM exhibits the most variable performance characteristics across datasets, with significant fluctuations in effectiveness that appear strongly dependent on the underlying biological and technical characteristics of each genomic dataset. SVM-P achieves the best performance on the SRBCT dataset with 94.95% accuracy and balanced sensitivity (93.94%) and specificity (93.94%). Conversely, SVM-P shows its weakest performance on the Leukemia dataset with 88.86% accuracy and notably reduced sensitivity (79.88%) and specificity (80.86%). The intermediate performance on other datasets, with accuracies ranging from 90.91% to 91.92%, indicates that while SVM-P can provide reasonable classification results, its application requires careful consideration of dataset-specific characteristics and potentially more extensive hyperparameter optimization.

Table 6 compares the performance of the Gravitational Search Algorithm (GSA) and a proposed method across six microarray datasets (Leukemia Cancer, MLL, Ovarian, CNS, SRBCT, and Lung Cancer), evaluating accuracy (Acc) and the number of selected features (feat) using best, average (Avg), and worst-case metrics. The proposed method consistently outperforms GSA in terms of best and average accuracy across all datasets, achieving perfect accuracy 100% for SRBCT and Lung Cancer in the best case, and higher average accuracies. Additionally, the proposed method selects fewer features in most cases, with best-case feature counts as low as 11 for SRBCT and 14 for Ovarian, compared to GSA’s 17 for both, indicating greater efficiency in identifying compact, relevant gene subsets. While GSA shows competitive worst-case accuracies, the proposed method generally maintains better worst-case performance and fewer features, highlighting its robustness and effectiveness for gene selection in cancer classification tasks.

An analysis of Fig. 3 reveals the comparative performance of several optimization algorithms, including the proposed method, evaluated on the SRBCT, Ovarian, and Lung cancer gene datasets. Each graph plots the average fitness values as a measure of solution quality against the number of iterations, providing insights into the convergence behavior and effectiveness of the algorithms. The algorithms evaluated include our method, TLBO, GA, DE, PSO, and GSA. In the SRBCT dataset, the proposed method consistently outperforms the other algorithms, achieving the highest average fitness values across all iterations. TLBO and GA show competitive performance but plateau at slightly lower fitness levels, while DE, PSO, and GSA exhibit slower convergence and significantly lower fitness values. The Ovarian dataset reveals a tight performance among the top algorithms, with the proposed method and TLBO leading in fitness values. GA and DE perform moderately, while PSO and GSA lag. Notably, all algorithms converge quickly, reaching stable fitness levels by around 20 iterations. For the Lung dataset, the proposed method again demonstrates superior performance, achieving the highest fitness value. TIBO and GA follow closely, while DE, PSO, and GSA trail behind. Across all three datasets, the proposed method consistently ranks at the top, showcasing its robustness and adaptability to varying gene expression profiles. Similarly, Fig. 4 shows that ours performs better than the existing state-of-the-art techniques over 100 iterations and early iterations in all three datasets. In other words, our method outperforms other methods and obtains an excellent fitness value.

The average PR curves of the five wrapper methods and our six microarray gene datasets are shown in Fig. 5. It can be seen that TLBO and GSA show moderate AUC values in most of the CNS and Ovarian data, while DE has the lowest convergence. It is worth mentioning that 100 iterations were enough for GA and PSO to come close to our modest goal in all cases. To obtain statistically meaningful findings, 10 independent folds are performed for each method. Results, including average classification accuracies, are calculated for each approach after a certain number of iterations. Convergence curves are also included for each approach.

The comparative performance of the proposed method against five evolutionary algorithms (Genetic Algorithm, Particle Swarm Optimization, Differential Evolution, Teaching-Learning-Based Optimization, and Gravitational Search Algorithm) is summarized in Table 7. The evaluation uses six microarray datasets and metrics for precision (Acc ± Std), feature selection count (feat), and execution time (ETime). The proposed method consistently achieves the highest accuracy with the lowest standard deviations on 94.71 ± 0.57 for Leukemia Cancer, 99.52 ± 0.38 for SRBCT and selects the fewest features as 11 for SRBCT, 14 for Ovarian, demonstrating superior efficiency and precision in gene selection for cancer classification. Additionally, it exhibits the lowest execution times (secs) in most datasets 522.85 for Lung Cancer, outperforming the other algorithms, which require more features and longer runtimes, thus highlighting the proposed method’s effectiveness and computational efficiency. Table 8 display the best accuracy and selected number of features in our and GA. From Table 8, findings indicated that, on average, 97.66% of the Lung cancer data achieves the average classification accuracy on TLBO, and our method with SVM-R demonstrated good performance values compared to the other on gene datasets and was very competitive regarding fitness values.

Figure 6 presents a comparative analysis of the execution times for six optimization algorithms, TLBO, PSO, DE, GA, and GSA, across six gene datasets: Leukemia, CNS, Ovarian, Lung, SRBCT, and MLL. The proposed method consistently demonstrates the lowest execution times across all datasets. This simplicity allows TLBO to maintain competitive execution times, particularly in datasets like Leukemia and Ovarian. Traditional algorithms, including GA, DE, PSO, and GSA, exhibit varying levels of efficiency. GA and DE show moderate execution times, with GA often slower due to its reliance on computationally intensive operations like crossover and mutation, as well as population-based evaluations that require extensive fitness calculations. PSO and GSA, on the other hand, tend to perform less efficiently, especially in high-dimensional datasets such as Lung and MLL.

The boxplot described in Figs. 7 and 8 visualizes MCC performance metric for six algorithms: Our, Genetic Algorithm (GA), Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Differential Evolution (DE), Teaching-Learning-Based Optimization (TLBO), and Gravitational Search Algorithm (GSA) across six gene datasets. The median MCC values indicate the central tendency of each algorithm’s performance, with our algorithm and PSO both achieving the highest median MCC, followed by TLBO, while GA, DE, and GSA each have a median MCC. The interquartile range (IQR) shown in the boxplot represents the spread of MCC values within the middle 50% of the data, indicating variability in performance consistency. Additionally, the boxplot includes the minimum and maximum MCC values for each algorithm, highlighting the full range of performance across the datasets. Since the description of used methods across used datasets suggests that the MCC values are averaged across datasets, the Proposed algorithm has superior performance based on its higher median MCC, while the lower medians of GA, DE, and GSA indicate relatively less consistent performance in optimizing gene selection for six cancer datasets.

Table 9 shows a comprehensive performance comparison of various nature-inspired optimization algorithms applied to SNP microarray data from the NCBI GEO dataset GSE16619, which contains breast cancer (BC)-related genetic information. The proposed method results are compared with the Acc and Sen, Sep , Fmeas, MCC achieved using the GA, PSO, DE,TLBO, GSA and our algorithm. As can be clearly seen, the performance of the proposed wrapper was significantly better and outperformed the compared methods on the given BC data. The evaluation employs five standard metrics that assess different aspects of classification performance when identifying breast cancer biomarkers from the SNP data. Genetic Algorithm (GA) demonstrates strong overall performance with 89.52% accuracy, showing balanced sensitivity (90.65%) and specificity (87.25%), indicating its effectiveness in correctly identifying both positive (cancer) and negative (normal) cases. Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) shows slightly lower but comparable results (88.74% accuracy), with particularly good specificity (88.63%), suggesting it may be more conservative in making positive predictions.

Differential Evolution (DE) exhibits an interesting performance profile, where while its accuracy is lower (81.25%), it achieves the highest specificity (91.52%) among the conventional methods, indicating exceptional ability to correctly identify negative cases, though at the cost of some overall accuracy. Teaching-Learning-Based Optimization (TLBO) shows good sensitivity (90.36%) but relatively lower F-measure (84.78%), suggesting it may struggle slightly with precision in its positive predictions. Gravitational Search Algorithm (GSA) maintains high accuracy (89.32%) but shows the lowest specificity (83.33%) among the baseline methods, indicating a tendency toward more false positives.

The proposed “Our” method outperforms all other approaches across every metric, achieving 93.52% accuracy, 95.62% sensitivity, and 94.12% specificity, demonstrating its superior capability to correctly classify both cancer and normal samples in the SNP microarray data. The particularly high Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) of 96.52% strongly suggests that this method maintains excellent performance even when accounting for potential class imbalances in the breast cancer dataset. These results indicate that the proposed approach may be better at identifying meaningful SNP patterns associated with breast cancer while minimizing both false positives and false negatives compared to established optimization algorithms.

Statistical analysis

The Friedman test58 is a non-parametric statistical method used to detect differences in treatments across multiple related samples, making it ideal for analyzing repeated measures or matched data in bioinformatics, such as gene expression levels across different conditions. It ranks the observations within each subject across treatments and evaluates whether the rank sums differ significantly to test the null hypothesis that all treatments have identical effects. This test is particularly valuable when data violates normality assumptions, offering a robust alternative to parametric tests. By accounting for within-subject variability, the Friedman test ensures reliable comparisons, though post-hoc tests are often needed to identify specific pairwise differences. The Table 10 presents the average rankings of six optimization algorithms based on the Friedman test, a non-parametric statistical method used to compare multiple algorithms across different datasets. The rankings reveal clear performance differences among the algorithms, with the proposed method (denoted as OUR) achieving the best possible ranking of 1, indicating superior performance compared to all other methods. Differential Evolution (DE) follows as the second-best performing algorithm with an average ranking of 5.1667, demonstrating its effectiveness as a conventional optimization approach. Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) obtains a ranking of 4.3333, placing it in the middle of the performance spectrum. The remaining algorithms—Genetic Algorithm (GA), Teaching-Learning-Based Optimization (TLBO), and Gravitational Search Algorithm (GSA)—show relatively similar performance levels with rankings of 3.6667, 3.3333, and 3.5 respectively. These closely clustered rankings suggest comparable effectiveness among these three methods, though all are outperformed by both the proposed method and DE. The significant gap between the top-ranked proposed method (1) and the next best algorithm (DE at 5.1667) highlights the substantial performance improvement achieved by the novel approach. These rankings provide valuable insights for algorithm selection in optimization tasks, with the proposed method emerging as the clear preferred choice based on this statistical evaluation. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of the Friedman test in discriminating between algorithm performances and establishing robust performance hierarchies. Friedman statistic (distributed according to chi-square with 5 degrees of freedom): 16.761905. P-value computed by Friedman Test: 0.004974.

The Table 11 presents a post-hoc statistical comparison of multiple nature-inspired algorithms using the Friedman test with a significance level \((\alpha )\) set at 0.05. The Friedman test, a non-parametric alternative to repeated-measures ANOVA, ranks the algorithms across different datasets to detect significant performance differences. The table lists five algorithms in descending order of their statistical significance: Differential Evolution (DE), Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Genetic Algorithm (GA), Gravitational Search Algorithm (GSA), and Teaching-Learning-Based Optimization (TLBO). Each algorithm’s performance is compared against a control method (presumably the best-performing one, denoted as \(R_0\)) through the standardized test statistic \(z = (R_0 - R_i)/SE\), where \(R_0\) is the control’s average rank, \(R_i\) is the algorithm’s average rank, and SE is the standard error of the difference. The p-values indicate the probability of observing the given differences under the null hypothesis (no performance difference). DE shows the strongest statistical significance with \(p = 0.000115\), far below the \(\alpha\) threshold, suggesting it outperforms the control method with high confidence. PSO follows with \(p = 0.002028\), also significant, though less so than DE. GA, GSA, and TLBO exhibit progressively weaker evidence against the null hypothesis, with p-values of 0.013555, 0.020638, and 0.030754, respectively. While these values are below the conventional \((\alpha )\) = 0.05, their significance is marginal compared to DE and PSO. The Holm and Li columns represent adjusted p-value thresholds for multiple comparisons. The Holm procedure, a step-down method, sequentially tightens the significance threshold to control the family-wise error rate (FWER). Here, DE, PSO, and GA remain significant under Holm’s correction, as their p-values are below their respective adjusted thresholds (0.01, 0.0125, and 0.016667). GSA and TLBO, however, fail to meet their stricter Holm thresholds (0.025 and 0.05, respectively).

Li’s procedure rejects those hypotheses that have an unadjusted p-value \(\le 0.05\).

Biological interpretation

From a biological perspective, only a small subset of genes in microarray datasets is relevant for the diagnostic and prognostic prediction of cancer. The proposed method aims to identify an optimal, compact subset of genes that achieves high classification accuracy across six gene datasets. Analyzing these selected genes alongside those reported in the literature is crucial to uncovering their biological significance for each dataset. In this section, we evaluate the final subset of genes selected by our proposed model (see Table 12), focusing on the most significant genes identified for each of the six datasets, emphasizing their optimality and classification accuracy.

Table 12 presents gene selected by our method across six cancer types, demonstrating high classification accuracy ranging from 94.25 to 100%. While these results show strong discriminative power, the biological interpretation requires careful consideration of each gene molecular functions and clinical relevance. For leukemia, the 17-gene signature includes well-characterized hematopoietic markers such as J04794 (myeloperoxidase, MPO), a key enzyme in myeloid cells that serves as a standard immunohistochemical marker for acute myeloid leukemia (AML). The signature also contains L06499 (cathepsin G, CTSG), a serine protease expressed in neutrophil granules, and M62402 (CD33), a transmembrane receptor used clinically as an immunotherapy target in AML. These markers collectively suggest our algorithm has captured essential features of myeloid differentiation and leukocyte activation pathways. Particularly noteworthy is the inclusion of D14822 (CEBPA), a transcription factor critical for granulocytic differentiation whose mutations are recognized in the WHO classification of AML. The presence of V00535 (a hemoglobin subunit) and several immunoglobulin-related transcripts (e.g., X84213) indicates the signature appropriately discriminates between myeloid and lymphoid lineages, crucial for accurate leukemia classification. The co-selection of these biologically validated markers with less characterized genes (e.g., AB002318) suggests our method maintains sensitivity to both established and potentially novel biomarkers.

The ovarian cancer gene signature identified by our method demonstrates compelling biological significance through its inclusion of multiple molecular markers with well-characterized roles in ovarian cancer pathogenesis. The signature contains GAPDH (AFFX-HUMGAPDH/M33197_5_at), a crucial glycolytic enzyme whose overexpression is strongly associated with tumor progression and development of chemoresistance in ovarian carcinomas. Particularly significant is the detection of HOXA9 (36076_g_at), a member of the HOX gene family whose dysregulation represents a molecular hallmark of ovarian cancer, known to critically influence cellular proliferation, adhesion dynamics, and metastatic dissemination through modulation of key oncogenic pathways.The signature encompasses genes participating in several fundamental ovarian cancer-related biological processes. These include critical DNA repair mechanisms, potentially involving BRCA1/2-associated genes (38674_at), which are especially relevant given the importance of homologous recombination deficiency in ovarian cancer biology. Additionally, the signature captures genes involved in extracellular matrix remodeling, likely including matrix metalloproteinases (37208_at), which facilitate tumor invasion and metastasis. Genes such as 41159_at and 41731_g_at can be involved in clinically relevant processes including peritoneal metastasis formation, the maintenance of stem cell-like properties in tumor cells.

The lung cancer gene signature includes several markers with well-established diagnostic significance, such as TTF-1 (35494_at, NKX2-1), a crucial transcription factor that serves as a key immunohistochemical marker for lung adenocarcinoma differentiation. The presence of mesothelin (36395_at) is particularly noteworthy as it represents a well-characterized marker for malignant pleural mesothelioma, suggesting our algorithm can distinguish between these histologically challenging differential diagnoses. The inclusion of surfactant-associated proteins (potentially represented by 33015_at and 34600_s_at) aligns with the alveolar origin of many lung adenocarcinomas. The signature also contains genes likely involved in cellular proliferation (32398_s_at) and apoptosis regulation (32974_at), processes frequently dysregulated in non-small cell lung cancer. The combination of well-characterized diagnostic markers (TTF-1, mesothelin) with less studied genes (1381_at, 172_at) indicates our approach maintains sensitivity to both established and potentially novel biomarkers in lung cancer pathology.

Conclusion

In the current era, microarray technology enables the simultaneous sequencing of thousands of gene expression levels in biological samples. One of the most prevailing applications is the prediction of cancer or tumor types. However, classifying microarray data is challenging due to its high dimensionality and small sample sizes. Gene selection techniques offer a practical solution to address these challenges in microarray data analysis. In the literature, several bio-inspired wrapper methods have been applied for gene selection and cancer classification, demonstrating promising classification accuracy. Nevertheless, identifying genes linked to cancer-associated biomarkers is critical for understanding the complex origins and expression networks of cancer. By enabling biologists to identify a subset of genes as biomarkers, wrapper-based feature selection provides a promising approach for gene selection. To identify genes associated with cancer, this study proposed a multi-population GSA algorithm combining Opposition-Based Learning (OBL) with kernel Principal Component Analysis (kPCA) method, termed MPKGSA, in order to achieve primary objectives: selecting the most predictive genes and achieving the highest classification accuracy from gene expression datasets. The MPKGSA method aims to distinguish cancer stages and uncover biologically relevant relationships within gene pools, thereby revealing underlying biological mechanisms and guiding clinical decision-making. The performance of MPKGSA was evaluated against other bioinspired techniques on six microarray datasets. Additionally, to evaluate proposed approach performance we have used SNP dataset obtained from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) related to breast cancer of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Experimental results demonstrated that MPKGSA outperformed state-of-the-art methods in classification accuracy by effectively selecting highly relevant genes for tumor classification. In the future, a new hybrid evolutionary model with deep learning, based on CNN, will be proposed for the classification of cancer/tumor.

Data availability

Data will be available on request to the corresponding author.

References

Yaqoob, A., Verma, N. K., Aziz, R. M. & Shah, M. A. Rna-seq analysis for breast cancer detection: a study on paired tissue samples using hybrid optimization and deep learning techniques. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 150, 455 (2024).

Yaqoob, A. et al. Sga-driven feature selection and random forest classification for enhanced breast cancer diagnosis: A comparative study. Sci. Rep. 15, 10944 (2025).

Agarwalla, P. & Mukhopadhyay, S. Gene expression selection for cancer classification using intelligent collaborative filtering and hamming distance guided multi-objective swarm optimization. Appl. Soft Comput. 1, 112654 (2025).

Saheed, Y. K., Balogun, B. F., Odunayo, B. J. & Abdulsalam, M. Microarray gene expression data classification via Wilcoxon sign rank sum and novel grey wolf optimized ensemble learning models. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinf. 20, 3575–3587. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCBB.2023.3305429 (2023).

Dey, A., Das Sharma, K., Sanyal, T., Bhattacharjee, P. & Bhattacharjee, P. Identification of biomarkers for arsenicosis employing multiple kernel learning embedded multiobjective swarm intelligence. IEEE Trans. NanoBiosci. 22, 383–392. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNB.2022.3194091 (2023).

Vashistha, R., Noor, Z., Dasgupta, S., Pu, J. & Deng, S. Application of statistical machine learning in biomarker selection. Sci. Rep. 13, 18331 (2023).

Yaqoob, A., Verma, N. K., Aziz, R. M. & Saxena, A. Enhancing feature selection through metaheuristic hybrid cuckoo search and harris hawks optimization for cancer classification. In Metaheuristics for Machine Learning: Algorithms and Applications 95–134 (2024).

Shah, E. & Maji, P. Multi-view kernel learning for identification of disease genes. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinf. 20, 2278–2290. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCBB.2023.3247033 (2023).

Qiu, Y., Li, R. & Zhang, X. Simultaneous svm parameters and feature selection optimization based on improved slime mould algorithm. IEEE Access 12, 18215–18236. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3351943 (2024).

Bonilla-Huerta, E., Hernández-Montiel, A., Morales-Caporal, R. & Arjona-López, M. Hybrid framework using multiple-filters and an embedded approach for an efficient selection and classification of microarray data. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 13, 12–26 (2016).

Chen, Y., Li, Y., Narayan, R., Subramanian, A. & Xie, X. Gene expression inference with deep learning. Bioinformatics 32, 1832–1839 (2016).