Abstract

The evaluation of asphalt pavement aging is a critical foundation for road maintenance decision-making and plays a significant role in ensuring traffic safety. Traditional monitoring methods often rely on manual field surveys, which are time-consuming and inefficient. This study proposes an innovative framework that integrates multi-endmember mixed pixel unmixing, automated sample generation, and deep learning. The goal is to enable rapid and accurate assessment of asphalt pavement aging over large areas. Based on WorldView-3 remote sensing data, high-quality training and validation samples were generated using multi-endmember spectral unmixing and neighborhood filtering. The Jeffries–Matusita (J-M) distance values exceeded 1.9 for model training samples and 1.7 for validation samples. In addition, a one-dimensional convolutional neural network (1D-CNN), combined with an unsupervised zero-shot transfer approach, was employed for model training and inference. The proposed framework was applied to several study areas. Overall classification accuracy and Kappa coefficients reached 95.95% and 0.9459 in study area-I (the south-central part of the Wuhan Economic and Technological Development Zone), and 89.70% and 0.8628 in study area-II (the northern part of the zone). This study highlights the effectiveness of the proposed framework for rapidly assessing asphalt pavement aging over large areas. The results are valuable for pavement maintenance and traffic safety warning applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Highways play a critical role in China’s social and economic development. By the end of 2023, the total highway mileage in China reached 5.437 million kilometers1. Asphalt pavement is the primary surface type used on high-grade highways, and it is a mixture of asphalt and aggregates, characterized by low cost, high comfort, and strong durability. However, asphalt pavements gradually deteriorate over time. Environmental factors such as temperature fluctuations, moisture, weathering, and traffic loads accelerate surface aging and damage. This degradation deteriorates structural strength and surface performance, leading to significant economic losses and increased safety risks2. Therefore, timely and accurate assessment of asphalt pavement aging is essential for ensuring the quality and safety of highway transportation.

Currently, asphalt pavement aging in China is mainly assessed through manual inspections and multifunctional road survey vehicles3. These conventional monitoring methods, which rely on direct human observation and specialized survey equipment, provide relatively accurate evaluations at the road segment level but are limited in spatial coverage. Nevertheless, when employed for large-scale monitoring, these methods face substantial limitations. High costs and limited sampling coverage make it difficult to capture the overall aging condition across extensive road networks. Remote sensing offers a powerful alternative for rapid, wide-area, and efficient monitoring, with applications in road network extraction, pavement material analysis, road corridor monitoring, and vehicle detection and localization4. With the rapid advancement of high-resolution satellite remote sensing, it has become possible to retrieve detailed spectral information from high-quality imagery5. This capability enables more accurate detection and analysis of spectral variations in asphalt surfaces. Consequently, these data provide a reliable foundation for developing large-scale asphalt aging assessment models.

In recent studies, high-resolution satellite imagery has become the primary data source for quantitatively assessing asphalt pavement aging due to its high spatial and spectral resolution6. For example, Mei et al. used IKONOS and QuickBird multispectral imagery to monitor the condition of asphalt roads in urban areas and airports7. Karimzadeh et al. developed a road quality assessment model by analyzing the relationship between the International Roughness Index (IRI) and spectral features from Sentinel-2 imagery8. Emery et al. applied a histogram thresholding method to classify panchromatic WorldView-2 images, identifying asphalt surfaces at different aging levels9. Pan et al. successfully mapped pavement aging in Fangshan District, Beijing, using WorldView-2 multispectral imagery10. With the rapid advancement of deep learning, many researchers have begun exploring neural network-based approaches for asphalt pavement assessment11. For instance, Chen et al. used an improved recurrent neural network to automatically detect aging asphalt areas from high-resolution satellite images. Their results showed that such imagery enables efficient large-scale pavement condition monitoring12. Pan et al. combined UAV-collected imagery with a CNN and SVM classifier to evaluate asphalt pavement aging13. Asphalt aging leads to changes in surface roughness and the chemical composition of the asphalt mix, which in turn alters its spectral characteristics, and the 1D-CNN treats spectral bands as a one-dimensional input sequence. Through convolution operations, 1D-CNN captures correlations between adjacent bands and extracts deep spectral features. This enhances the model’s sensitivity to subtle spectral changes14. Therefore, applying a 1D-CNN to asphalt aging assessment is not only feasible but also offers an effective trade-off between accuracy and efficiency.

However, despite previous attempts to assess asphalt pavement aging, several limitations and challenges remain. First, many approaches rely heavily on manual sample collection, lacking effective strategies for generating large-scale, balanced, and representative training datasets. Second, most studies are confined to small-scale or single-road scenarios, which restricts their applicability for large-area monitoring. Third, traditional spectral classification methods often struggle to distinguish subtle differences among early, mid, and late aging asphalt. Finally, the transferability of existing models has not been sufficiently validated, limiting their practical deployment in large-scale applications. Moreover, in practical road scenarios, the surrounding areas often include lane markings, vegetation, bare soil, and shadows, which result in heterogeneous environments where multiple land cover types are mixed within a single pixel15. The inclusion of these mixed components poses challenges to the precise evaluation of asphalt aging and increases the complexity of the analysis, which remains a major challenge for previous studies.

To overcome this issue, we propose a integrated framework that combines mixed pixel unmixing, automated sample generation, and deep learning model selection. This framework is designed to support rapid, large-scale, and multi-region assessment of asphalt pavement aging. This study develops an integrated framework comprising three key strategies: (i) enhancing the separation of asphalt pavements from surrounding features through an improved mixed pixel unmixing (spectral unmixing) model, (ii) establishing an automated procedure for generating reliable training samples to reduce manual selection effort, and (iii) applying a transferable deep learning model to support accurate and scalable assessment across large regions.

Study area and data source

Study area

The Wuhan Economic and Technological Development Zone (WEDZ) is located in the southwestern part of Wuhan, adjacent to the Yangtze River, a key waterway in central China. Geographically, it spans from 113°25′E to 114°9′E and from 30°11′N to 30°29′N16, and the zone covers a total land area of approximately 489.74 square kilometers (Fig. 1). The WEDZ is characterized by the typical geomorphology of the Han River alluvial plain, with terrain that is higher on the periphery and lower in the center17,18.

As a national-level economic and technological development zone, the WEDZ plays a central role in China’s pilot program for intelligent and connected vehicles (ICVs). Its road system is dense, well-planned, and highly connected, comprising expressways, arterial roads, and major transport corridors such as the Beijing–Hong Kong–Macau Expressway and the Wuhan Third Ring Road, which ensures efficient regional connectivity19.

Location of the study area. (a) Hubei Province Region within China; (b) Location of Wuhan City; (c) Image of Study area-I; (d) Image of Study area-II. The imagery was purchased from Maxar Technologies, Inc., and was processed and mapped using QGIS v3.42.3 (open-source software, available for download at https://qgis.org/download/).

In recent years, with the rapid pace of urbanization, the operational pressure on roads within urban areas has been steadily increasing. The quality of asphalt pavements has been significantly affected by traffic load, manufacturing processes, and environmental conditions20. Consequently, the degree of pavement aging exhibits significant spatial heterogeneity (Fig. 2). Early aging refers to the initial stage of asphalt pavement deterioration, during which the surface color gradually lightens, accompanied by slight wear and the appearance of fine cracks, while the overall structure remains intact. Mid aging refers to the intermediate stage of asphalt pavement deterioration, where the asphalt binder continues to degrade, resulting in aggregate exposure and increased cracking and loosening. Late aging refers to the advanced stage of asphalt pavement deterioration, characterized by extensive cracking, potholes, and surface peeling, leading to a significant reduction in pavement strength, often accompanied by settlement.

Therefore, rapid and accurate identification and monitoring of asphalt pavement aging are essential for sustaining regional economic development and ensuring the effective operation of the national ICV testing and demonstration base.

Causes of asphalt pavement aging. The imagery was purchased from Maxar Technologies, Inc., and was processed and mapped using QGIS v3.42.3 (open-source software, available for download at https://qgis.org/download/).

Satellite data processing

The WorldView-3 is a fourth-generation high-resolution optical satellite launched in August 2014 by DigitalGlobe, and it offers a panchromatic spatial resolution of 0.31 m, making it the highest-resolution commercial optical satellite currently available. In addition to 0.31 m panchromatic and eight-band multispectral imagery, WorldView-3 is equipped with eight shortwave infrared bands. With its ability to capture fine spatial details and its broad spectral coverage across the visible, near-infrared, and shortwave infrared regions, WorldView-3 provides data quality comparable to that of airborne sensors. These characteristics make it highly suitable for quantitative remote sensing applications, including vegetation monitoring, mineral exploration, and coastal and marine environmental studies21.

To accurately evaluate the aging condition of asphalt pavements over a broad area within the specified study region, the primary dataset consisted of two WorldView-3 scenes acquired on August 12 and 19, 2022. The dataset was acquired under relatively favorable weather conditions, ensuring high data quality and minimizing adverse effects on the assessment of asphalt pavement aging. The dataset includes 0.5 m panchromatic imagery and 2 m multispectral imagery. The spectral features used in this study consist of eight spectral bands: coastal, blue, green, yellow, red, red edge, near-infrared 1, and near-infrared 2 (Table 1).

The spectral characteristics of remote sensing imagery are essential for assessing pavement aging. Therefore, a series of preprocessing steps were applied to derive accurate surface reflectance of asphalt pavements from the WorldView-3 imagery. Specifically, digital numbers of the multispectral bands were converted to radiance via radiometric calibration. Subsequently, atmospheric correction was performed using the FLAASH model to derive surface reflectance. Similarly, radiometric calibration was applied to the panchromatic imagery to obtain apparent reflectance. Both panchromatic and multispectral images were orthorectified using rational polynomial coefficients and a digital elevation model (DEM). The orthorectified images were then fused using the Gram-Schmidt pan-sharpening method to generate pan-sharpened multispectral imagery at 0.5 m spatial resolution22 (Fig. 3). Finally, a road network vector was used to clip the fused multispectral imagery, ensuring that the analysis focused exclusively.

Notably, compared with the 2 m multispectral imagery, the 0.5 m pan-sharpened imagery offers significantly finer spatial detail. Considering that different stages of asphalt pavement aging are characterized by varying degrees of color fading, surface cracking, and raveling, the use of higher spatial resolution imagery is particularly advantageous for evaluating pavement aging. Therefore, the preprocessing of WorldView-3 imagery yields both high spatial resolution and rich spectral diversity, thereby greatly enhancing the accuracy and reliability of detecting and classifying different stages of pavement aging.

WorldView-3 satellite imagery. The imagery was purchased from Maxar Technologies, Inc., and was processed and mapped using QGIS v3.42.3 (open-source software, available for download at https://qgis.org/download/).

Building road surface spectral library

To accurately characterize the spectral characteristics of asphalt pavement, a FieldSpec 4 portable spectroradiometer (ASD Inc., USA) was employed. The instrument covers a spectral range of 350–2500 nm6. Representative road sections within the study area were selected for in-situ measurements of pavement spectral reflectance, using relatively clean and representative pavement samples. The collected spectra covered: (i) asphalt pavement with varying degrees of aging; (ii) pavement distresses such as cracks and potholes; (iii) typical non-asphalt surface features such as lane markings, roadside vegetation, manhole covers, zebra crossings, pedestrian paving bricks, and concrete pavement. Among them, (i) corresponds to early, mid, and late aging asphalt pavement, whereas (ii) and (iii) correspond to the non-asphalt pavement category.

All collected spectral data were preprocessed through gain calibration and other standard procedures. Multiple measurements are made for each sampling point, and the average value is taken. Then the noise is suppressed by low-pass filtering. Finally, the abnormal value caused by atmospheric water vapor absorption is eliminated by interpolation23. In order to collect the road surface aging state information more conveniently and quickly, according to the actual field investigation and the experience of other scholars, a Munsell value scale (full-gloss) was used during field measurements to visually assess the pavement lightness level at each sampling point24.

An asphalt pavement aging assessment table based on MunseIl brightness color chart-full gloss was established, thereby providing a reference for surface aging severity (Table 2). These reflectance ranges not only reflect the statistical distribution of the measured spectra but also correspond to the deterioration phenomena at different stages of asphalt pavement aging. Specifically, low reflectance values (early aging) indicate that the pavement remains largely intact with only minor wear; intermediate reflectance values (mid aging) reflect binder degradation, aggregate exposure, and increased cracking; while high reflectance values (late aging) are associated with severe binder loss, extensive cracking, potholes, and peeling, which correspond to a significant reduction in pavement strength and durability. Based on this information, a spectral library of typical pavement surfaces was constructed.

Method

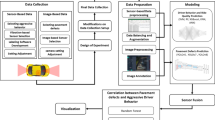

The detailed research workflow is illustrated in Fig. 4 and comprises the following main steps: (i) Mixed pixel unmixing using a combination of two-endmember and three-endmember MESMA model; (ii) Automated sample generation based on the mixed pixel unmixing result; (iii) Construction of the 1D-CNN model for regional asphalt pavement aging assessment; (iv) Model transfer using an unsupervised zero-shot transfer approach; (v) Assessment of asphalt pavement aging identification accuracy.

Mixed pixel unmixing

Multiple Endmember Spectral Mixture Analysis (MESMA) is an advanced mixed pixel unmixing method developed based on Linear Spectral Mixture Analysis (LSMA). The LSMA typically employs a fixed set of endmembers for the entire image, whereas the MESMA allows the selection of multiple spectral signatures for each land cover type, enabling the generation of diverse endmember combinations. Subsequently, spectral unmixing is performed for each pixel by selecting the combination that minimizes the least squares error, thereby deriving the pixel-specific endmember proportions. By accounting for intra-class spectral variability and different combinations of materials within a pixel, the MESMA effectively addresses the “same object, different spectra” phenomenon frequently encountered in remote sensing imagery25.

Based on the above, in order to reduce the influence of non-asphalt elements such as lane markings, shadows and vegetation on the quality evaluation of asphalt pavement, this study combined with the high resolution satellite imagery, proposed a mixed pixel unmixing model based on MESMA. The model is specifically designed to support large-scale, rapid evaluation of asphalt pavement conditions.

The LSMA assumes that the spectrum of a mixed pixel is a linear combination of the spectra of several distinct land cover types26. The basic model can be expressed as follows:

where \(\:{{\uprho\:}}_{{\uplambda\:}}^{{\prime\:}}\) represents the reflectance of endmember i in spectral band \(\:{\uplambda\:}\), \(\:{\text{f}}_{\text{i}}\) denotes the proportion of the endmember within the pixel, \(\:\text{N}\) is the total number of endmembers, \(\:{{\upepsilon\:}}_{{\uplambda\:}}\) is the residual error, j indicates the index of the endmember with the highest abundance, and M is the total number of spectral bands.

Compared to traditional LSMA, the MEMSA approach enhances the diversity and richness of endmember combinations within mixed pixels by evaluating and selecting the optimal endmember combination model that best represents each pixel. Optimization criteria commonly used include the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Endmember Average Root mean square error (EAR), and Minimum Average Spectral Angle (MASA)27. The formulas for calculating EAR and MASA are as follows:

where A is the end element category, Ai is the end element, B is the modeling spectrum category, and n is the number of modeling spectra in class B; \(\:{\uptheta\:}\:\)is the spectral Angle, \(\:{\text{L}}_{\text{p}}\) is the length of the end element vector, and \(\:{\text{L}}_{{\text{p}}^{{\prime\:}}}\) is the length of the modeling spectrum vector.

To rapidly assess the aging condition of asphalt pavements using high-resolution satellite remote sensing images, this study constructs a MEMSA model based on hybrid two-terminal and three-terminal elements for both asphalt and non-asphalt pavements, as well as shadows. Specifically, the two-endmember model includes combinations of asphalt pavement and shadow, or non-asphalt pavement and shadow, while the three-endmember model refers to combinations among asphalt pavement, non-asphalt pavement, and shadow. The specific process of running this model is as follows: each spectral element from the asphalt pavement terminal group, each spectrum from the non-asphalt pavement terminal group, and the shadow terminal element are combined according to the two-terminal and three-terminal models. Then, linear spectral unmixing is performed on each combination, and the RMSE for each pixel is calculated. Finally, the terminal group with the smallest RMSE for each pixel is selected as the optimal terminal combination for that pixel. This combination is then used for spectral unmixing to obtain the abundance of asphalt pavement, non-asphalt pavement, and shadow \(\:{f}_{R}\), \(\:{f}_{notR}\), \(\:{f}_{shade}\). The shadow component caused by light changes is removed through a normalization factor weighting method28, resulting in the final abundance of asphalt pavement\(\:\:{F}_{R}\:\)and non-asphalt pavement \(\:{F}_{notR}\):

Considering that the asphalt pavement endmember includes three spectral types corresponding to early aging, mid aging, and late aging, the endmember combinations selected for each pixel during the operation of the three-endmember MEMSA model may vary. To further determine the specific aging stage of the asphalt pavement, each pixel is examined individually and classified based on its selected endmember combination according to the following rules:

-

If the endmember combination does not include any asphalt pavement spectra, the pixel is classified as non-asphalt pavement;

-

If the endmember combination includes asphalt pavement spectra, but the abundance of asphalt pavement is lower than that of non-asphalt pavement, the pixel is still classified as non-asphalt pavement;

-

If the endmember combination includes asphalt pavement spectra, and the abundance of asphalt pavement is higher than that of non-asphalt pavement, the pixel is classified as asphalt pavement at the corresponding aging stage, according to the specific type of asphalt endmember selected.

Automated sample generation

Based on the abundance raster data obtained using the two-endmember and three-endmember combined MESMA model, a sample set was constructed following the principles of class balance, spatial uniformity, sample independence, and representativeness. The dataset comprised categories representing early aging, mid aging, and late aging of asphalt pavement, as well as non-asphalt pavement surfaces.

Nevertheless, the samples generated for each land cover category still involved a certain degree of uncertainty. To improve the reliability and representativeness of the generated samples and to reduce the impact of noise (e.g., minor disturbances caused by road damage or natural environmental factors) in remote sensing imagery, principles from the First Law of Geography (FLG) were integrated into the sample generation process. The FLG states that everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things29. Based on this principle, a spatial filter was specifically designed to refine the generated sample set for each class.

This method helps to avoid sampling points near class boundaries, thereby reducing classification uncertainty, enhancing spatial continuity, and minimizing noise30. The detailed process is illustrated in Fig. 5.

The screening process was as follows: first, the pixels of the type to be screened in the abundance map are assigned a value of 1, while other types are assigned a value of 0. Then, a 3 × 3 filter with kernel values of 1 is used to filter the 3 × 3 object centered on the pixel to be screened. When the filtering result (N) equals 9, the pixel was retained; otherwise, it is deleted. The filtering formula is as follows:

where \(\:{\text{P}}_{\text{i},\:\text{j}}\) denotes the neighboring pixel values of the target class to be filtered, \(\:{\text{K}}_{\text{i},\:\text{j}}\) represents the kernel values of the filter, and i and j refer to the row and column indices, respectively.

To ensure the quality of the proposed four types of sample sets, the sample sets were evaluated by combining the remote sensing images and the sample data using the J-M distance. The J-M distance provides a widely used statistical measure to evaluate the discriminability between classes based on the divergence of their sample distributions31. The J-M distance ranges between 0 and 2, with higher values reflecting better class separability. Typically, a J-M distance above 1.8 indicates strong separability, values from 1.4 to 1.8 indicate moderate or acceptable separability, while values below 1.4 reflect poor class differentiation. The calculation method and formula for the J-M distance are detailed below:

where B represents the Bhattacharyya distance on a specific feature dimension. For the samples selected from different types, the formula for calculating the Bhattacharyya distance B is given as follows:

where m represents the mean value of the feature, and δ represents the variance of a specific feature.

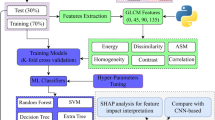

1D-CNN model construction and transfer

Given the sensitivity of spectral information in remote sensing imagery to the aging condition of asphalt pavements, a convolutional neural network (CNN) was employed to evaluate pavement aging based on the composite dataset. The pixel-based 1D-CNN is specifically designed to process sequential data. By leveraging a multi-layer architecture to mine and extract high-dimensional features, this model can automatically learn complex patterns embedded within the data, and has demonstrated strong performance in previous studies32.

The complete 1D-CNN architecture comprises four main components: input, convolutional layers, fully connected layers, and output. In this study, the proposed 1D-CNN model consists of two convolutional layers with 64 and 128 filters, respectively, each using a kernel size of 3 and the ReLU activation function. Each convolutional layer is followed by a batch normalization layer to accelerate convergence and enhance model generalization. A max pooling layer and a dropout layer (0.3) were added after the first convolutional layer to reduce dimensionality and mitigate overfitting. After flattening the features, a fully connected layer with 128 neurons and a ReLU activation function is applied, followed by a dropout layer (0.5) for further regularization. The final output layer uses the Softmax function to perform multi-class classification. The architecture of the 1D-CNN is illustrated in Fig. 6.

To enable automated assessment of asphalt pavement aging across multiple target regions, the generalization capability of the proposed model was further evaluated through model transfer. Given the high similarity in data distribution and task characteristics between source and target regions, an unsupervised zero-shot transfer approach was employed. In this method, the asphalt pavement aging assessment model, originally trained on the source region, is directly applied to new target regions without requiring additional labeled data or retraining33. This strategy not only demonstrates the feasibility of large-scale, rapid assessment of asphalt pavement aging but also reduces the cost of practical applications.

Assessment of classification accuracy

To evaluate the classification performance of asphalt pavement aging states in the training, transfer, and prediction regions while mitigating the effects of randomness and overfitting, which may otherwise lead to overly optimistic results, this study adopted a strategy that combines five-fold cross-validation with confusion matrix analysis34,35.

The five-fold cross-validation method partitions the dataset into five equally sized subsets (folds) and conducts five rounds of validation. In each round, one subset is used as the validation set, while the remaining four subsets are used for training. The final performance metrics were obtained by averaging the results across the five rounds, thereby reducing the influence of randomness from any single data split and providing a more robust and reliable performance evaluation (Fig. 7).

Based on each validation set, user accuracy, producer accuracy, overall accuracy, Kappa coefficient, and F1-score were calculated as evaluation metrics to assess the classification accuracy of asphalt pavement aging conditions. Assuming there are correctly classified pixels and a total of N pixels, the formulas used to calculate each metric are presented below:

User’s Accuracy (UA) refers to the ratio of correctly classified pixels for a specific category to the total number of pixels that were classified as that category.

Producer’s Accuracy (PA) refers to the ratio of correctly classified pixels of a specific category to the total number of reference pixels that actually belong to that category.

Overall Accuracy (OA) refers to the ratio of correctly classified pixels to the total number of pixels.

The Kappa is a statistical metric used to evaluate the consistency or agreement of classification results beyond chance level.

The F1-score comprehensively evaluates both the accuracy and the discriminative ability of the model.

Results

Mixed pixel unmixing based on Two-Endmember and Three-Endmember combinations

Asphalt pavements are exposed to harsh natural environments from the moment they are constructed, enduring long-term impacts from temperature fluctuations, water erosion, and heavy traffic loads. These repeated stressors often lead to aging effects such as surface wear and asphalt volatilization. Asphalt pavement aging is a progressive process that follows a relatively predictable pattern, typically categorized into early, mid, and late stages36.

In the early stage of aging, vehicle-induced abrasion, combined with asphalt volatilization and oxidation, leads to a reduction in surface asphalt content. As a result, pavement roughness begins to increase, surface color gradually fades, and fine cracks may start to appear. However, the overall structural integrity of the pavement remains largely intact. During the mid stage, the loss of asphalt binder becomes more pronounced, and the adhesion between aggregates and asphalt weakens. The pavement surface begins to loosen, asphalt debris accumulates, and structural damage becomes evident, compromising the strength and stability of the pavement. In the late stage of aging, further degradation and material deterioration result in surface spalling or peeling, the formation of extensive cracking and potholes, and a marked decline in structural stability. At this point, severe issues such as subgrade settlement and pavement collapse may occur, posing significant safety and maintenance challenges37.

The coexistence of asphalt and non-asphalt surfaces can affect the spectral reflectance in remote sensing images to some extent. Therefore, a spectrometer was used to collect the spectral reflectance data for asphalt roads (early, mid, and late aging), non-asphalt surfaces (cement roads, planted sidewalks, lane lines, and bare soil), and shadow spectra. By selecting 147 representative sampling sites covering asphalt pavements at different aging stages as well as typical non-asphalt surfaces, we measured the spectral reflectance ten times at each site and used the average value to reduce random noise. Based on the value of EAR and MASA, 14 spectra from early aging asphalt pavements, 53 spectra from mid aging asphalt pavements, 17 spectra from late aging asphalt pavements, 6 spectra from cement pavements, 4 spectra from vegetation, 10 spectra from sidewalks, 16 spectra from lane lines, and 2 spectra from bare soil were selected from the spectral library as the optimal end-member spectra. The subset of optimal spectra for each type are shown in Fig. 7.

According to the spectral reflectance distributions shown in Fig. 8, early aging asphalt pavements exhibit reflectance values primarily ranging from 0.060 to 0.090. In the mid of aging, the reflectance mainly falls between 0.090 and 0.135, while in the late aging, it increases significantly, ranging from 0.105 to 0.240. Moreover, the spectral variation across wavelengths becomes more pronounced in the late aging asphalt compared to the early and mid aging. In contrast, cement pavement spectra are mainly distributed between 0.080 and 0.130, vegetation between 0.010 and 0.550, sidewalks between 0.100 and 0.290, lane markings between 0.200 and 0.425, and bare soil between 0.040 and 0.330. Notably, vegetation and bare soil spectra demonstrate greater variability across the wavelength range than other surface types. These distinct spectral characteristics among different surface types after filtering offer a robust basis for their effective differentiation and identification in remote sensing imagery.

Considering the characteristics of high-resolution remote sensing imagery, pure asphalt pixels are relatively rare. Pixels located near the central median or road edges are often influenced by non-asphalt surface features such as shadows, bare soil, lane markings, medians, and paving stones. Therefore, pixels representing central asphalt pavement areas are better suited for unmixing using a two-endmember model, with two possible endmember combinations: (1) asphalt pavement and shadow, or (2) non-asphalt surface and shadow. In contrast, pixels near the median or road edges are better decomposed using a three-endmember model, consisting of asphalt pavement, non-asphalt surface, and shadow. Based on this analysis, three types of endmember combinations can be defined for asphalt pavement. Accordingly, an adaptive endmember combination model is proposed for asphalt pavement quality assessment. This model selects between two-endmember and three-endmember unmixings by minimizing the RMSE of the spectral unmixing results (Table 3).

According to Table 3, the proportions of pixels that could not be successfully unmixed in Study area-I and Study area-II account for 20.63% and 13.67% of the total pixels in the respective study regions. This is mainly due to the limited spectral types of the surveyed road surfaces and the presence of various interference factors, such as different types of vehicles, vegetation, and road surface wetness. Despite these interferences, the majority of pixels were successfully unmixed. Specifically, in Study area-I and Study area-II, the proportions of pixels successfully unmixed by the two-endmember model were 69.07% and 76.74%, respectively, while those successfully unmixed by the three-endmember model were 12.97% and 14.07%, respectively. These results indicate that in high-resolution satellite imagery, mixed pixels on asphalt pavements are relatively few, and most are suitable for the two-endmember model. In contrast, pixels near central medians and road edges are more affected by non-asphalt features such as bare soil, lane markings, medians, and paving stones, and are thus more appropriate for the three-endmember model. This further demonstrates the necessity of integrating both two-endmember and three-endmember models when performing mixed pixel unmixing of road surfaces using high-resolution satellite imagery.

Based on the three-endmember linear spectral mixing model composed of asphalt pavement, non-asphalt pavement, and shadows, the effective unmixing of mixed pixels is realized by combining the optimized endmember spectra with high-resolution WorldView-3 satellite images. To ensure model reliability, the spectral abundance range (the fractional coverage values of each endmember within a pixel) was constrained. Specifically, the abundance range for non-shadow components was set between − 0.05 and 1.05, the maximum allowable shadow abundance was limited to 0.8, and both RMSE and residual thresholds were restricted to 0.02538. These constraints enhance the robustness and physical interpretability of the unmixing process.

Following spectral unmixing, the abundance maps for asphalt pavement and non-asphalt pavement endmembers were derived after normalizing the shadow components, as illustrated in Fig. 9. Specifically, asphalt pavement abundance represents the contribution of asphalt spectral endmembers (early, mid, or late aging asphalt) within a mixed pixel, while non-asphalt pavement abundance corresponds to the contribution of other surface types (e.g., cement pavement, vegetation, sidewalks, lane markings, and bare soil).

Automated sample generation and assessment

Based on the MEMSA mixed pixel unmixing model, which integrates both two- and three-endmember configurations, the abundance maps of asphalt and non-asphalt surfaces were analyzed to identify pixels corresponding to early, mid, and late aging, as well as non-asphalt surfaces. Specifically, for each pixel, if it was modeled using a two-endmember combination, its type (i.e., early, mid, or late aging asphalt, or non-asphalt surface) could be directly determined based on the combination of endmembers and the spectral signatures employed. In contrast, for pixels using the three-endmember model, classification was based on a comparison between the abundance of asphalt and non-asphalt endmembers. The pixel was assigned to the category corresponding to the higher abundance value. For those identified as asphalt, the aging was further distinguished using the specific spectral curves (early, mid, or late aging) involved in the three-endmember model.

To further improve the quality of the sample set, a 3 × 3 neighborhood spatial filter was applied to the classified pixels to iteratively extract non-boundary samples, thereby reducing label uncertainty near class boundaries. Figure 10 depicts the local original samples alongside the automatically generated samples for comparison.

Spatial local sample distribution. Diamonds within the rectangle indicate the original samples, whereas circles denote the generated samples. The imagery was purchased from Maxar Technologies, Inc., and was processed and mapped using QGIS v3.42.3 (open-source software, available for download at https://qgis.org/download/).

Therefore, a balanced and spectrally pure 1D-CNN training and testing sample set was generated, comprising 2,239 samples of early aging asphalt pavement, 1,949 samples of moderately aging asphalt pavement, 2,124 samples of severely aging asphalt pavement, and 1,862 samples of non-asphalt pavement (Table 4). To evaluate the final classification accuracy in the two study areas, 6,000 sample points were generated for each region using the same approach. In addition, we conducted manual visual interpretation of a portion of the automatically generated validation samples on the remote sensing imagery to ensure their reliability. Based on five-fold cross-validation, 300 validation points per class were used in each iteration, and the average values across all folds were computed to derive the final classification metrics.

To evaluate the quality of the sample sets used for model training and testing, as well as those used for classification accuracy assessment in the two study areas, we further calculated the J-M distance between different classes based on the generated samples to enable quantitative assessment (Fig. 11). As shown in Fig. 11, the J-M distances for the training and testing sample sets are all above 1.9, indicating that the sample quality meets the requirements of the 1D-CNN model and is conducive to enhancing both model performance and generalization ability. For the samples used in accuracy assessment, the inter-class J-M distances are all above 1.7, suggesting good class separability. Additionally, the results reveal some degree of spectral confusion in the remote sensing imagery, particularly between moderately aging and severely aging asphalt pavement, as well as between severely aging asphalt pavement and non-asphalt surfaces.

Assessment results of asphalt pavement aging conditions

Based on the sample set from study area-I and WorldView-3 remote sensing imagery, we trained and tested a 1D-CNN model. The model was compiled using the Adam optimizer and a categorical cross-entropy loss function, with accuracy and loss serving as the primary evaluation metrics. During training, stratified sampling was employed to partition the validation set, ensuring a balanced class distribution. The model was trained 300 epochs with a batch size of 64 samples.

The training process, including changes in accuracy and loss, is illustrated in Fig. 12. Based on the performance of accuracy and loss on the training and testing sample sets shown in the Fig. 10, the model demonstrates satisfactory overall performance. Specifically, the training accuracy eventually stabilizes around 0.96 with a corresponding loss value of approximately 0.09. In terms of the testing set, the model achieves a final accuracy of around 0.95, while the loss converges to approximately 0.13.

The trained model was applied to study area-I and study area-II to assess the asphalt pavement condition in both regions rapidly. The prediction results are presented in Fig. 11, which illustrates both the overall and local classification outcomes. At the regional scale, the pavement condition in study area-I is generally better than that in study area-II. Specifically, asphalt surfaces in study area-I are predominantly in the early aging, whereas those in study area-II are mainly in the mid to late aging. In addition, the detailed local views in Fig. 13 demonstrate the model’s effectiveness in accurately distinguishing non-asphalt surfaces such as medians, vehicles, and roundabouts at intersections.

Global and local visualization of classification results. (a) Classification result for study area-I; (b) Classification result for study area-II. The imagery was purchased from Maxar Technologies, Inc., and was processed and mapped using QGIS v3.42.3 (open-source software, available for download at https://qgis.org/download/).

To quantitatively evaluate the classification performance in the two regions, 6,000 samples were collected for each region, with 1,500 samples per class. A five-fold cross-validation strategy was employed to compute the classification accuracy metrics. In each fold, 300 samples from each class were used for evaluation. The final results for UA, PA, F1-score, OA, and the Kappa coefficient were obtained by averaging the outcomes across the five iterations (Table 5).

For study area-I, the OA and Kappa coefficient reached 95.95% and 0.9459, respectively, with the UA, PA, and F1-score for each class all exceeding 94%, indicating high classification performance. For study area-II, the OA and Kappa were 89.70% and 0.8628, respectively, and the UA, PA, and F1-score for each class were all above 79%. Although the overall accuracy in study area-II was slightly lower compared to study area-I, it remains relatively high and generally meets the classification accuracy requirements of this study.

Discussion

Analysis of aging causes of asphalt pavement in the study area

According to the 2024 Wuhan Transportation High-Quality Development Report, by the end of 2023, the total length of operational roads in Wuhan reached 17,000 km. The city had 24 expressways totaling 975 km, forming a “six-ring, fifteen-radial” expressway network. Construction of the extended “seven-ring, thirty-radial” system is progressing steadily, with a 85% completion rate. Asphalt pavement accounts for the majority of this network. In recent years, rapid urban development has significantly increased traffic pressure in Wuhan. As a result, asphalt pavement deterioration has become increasingly prevalent. Although local authorities have emphasized road maintenance through routine inspections and targeted repairs such as crack sealing, the timeliness of asphalt pavement maintenance remains inadequate.

In this study, we propose a large-scale, rapid, and transferable framework for asphalt pavement assessment. Using this framework, we evaluate the degree of asphalt aging within two subregions of the Wuhan Economic and Technological Development Zone. The goal is to provide valuable maintenance information for transportation authorities. According to the classification results of asphalt pavement quality (Fig. 14), the number of pixels in each category was obtained. Combined with the spatial resolution of the remote sensing imagery, the spatial distribution area of each category was then calculated. Specifically, the areas of early, mid, and late aging in study area-I are approximately 480,000 m², 230,000 m², and 88,000 m², accounting for 32.69%, 15.83%, and 6.07% of the total, respectively. Other pavement types cover 660,000 m², representing 45.40%. In study area-II, the areas of early, mid, and late aging are about 200,000 m², 420,000 m², and 210,000 m², corresponding to 15.97%, 33.81%, and 17.00%, respectively. Other pavement types account for 410,000 m² or 33.21% of the total.

In study area-I, asphalt pavement is mostly in the early aging, followed by the mid aging, with late aging being the least prevalent. This indicates that pavement quality in the area is relatively good. In study area-II, mid and late aging dominate, while early aging is relatively uncommon. This suggests that pavement conditions in this region are poorer. Both regions also show a considerable presence of non-asphalt surfaces, mainly due to non-asphalt pavements and other surface features along the roads. Further analysis of the remote sensing imagery (Fig. 1) and classification results (Fig. 13) for the two asphalt pavement assessment areas reveals distinct spatial characteristics. Study area-I is located in the south-central part of the Economic Development Zone, representing a newly developed urban area. In contrast, Study area-II lies in the northern part of the zone, near Hanyang District, and belongs to the older urban core. The road network and residential facilities in study area-II were established earlier and are more densely distributed. This contributes significantly to the poor condition of asphalt pavements in the area, which are mostly in the mid aging. Although infrastructure development in study area-I began more recently, the imagery reveals widespread industrial facilities. Increased heavy vehicle traffic has led to early aging pavement aging across the region.

In fact, the aging of asphalt pavement is a progressive process that occurs before the appearance of apparent surface damage. Although most maintenance activities focus on repairing visible distresses such as cracks and potholes, different stages of aging may indicate the trend of deterioration toward such damage. Therefore, timely knowledge of the spatial distribution of asphalt pavement aging stages (as shown in Fig. 11) and the regional proportions of aging conditions (as shown in Fig. 12) can provide early-warning information. This information can be used to schedule preventive maintenance strategies (e.g., rejuvenation, surface sealing, or localized rehabilitation), prioritize the allocation of limited resources, and reduce the probability of costly large-scale rehabilitation. In this way, aging evaluation complements traditional distress surveys and offers significant value for pavement maintenance and management.

Advantages and uncertainties of the research framework

Traditionally, the assessment of asphalt pavement aging relies field surveys, which is time-consuming and inefficient, making it unsuitable for large-scale evaluations. To address this limitation, we propose a novel framework that integrates multi-endmember spectral unmixing, automatic sample generation, and deep learning. The method enables efficient and high-quality sample set construction while supporting rapid, high-precision assessments of asphalt aging over large spatial extents. Moreover, only a small number of representative surface spectra need to be collected in the field. Spectral unmixing combined with neighborhood filtering enables automatic generation of a large numbers of training samples, significantly reducing the labor and time requirements of manual sample preparation.

Although the proposed framework for asphalt pavement aging classification and assessment showed strong applicability in both study areas within the Wuhan Economic and Technological Development Zone, some uncertainties remain. Firstly, Although this study employed high-quality imagery and field-collected representative spectral data to reduce the influence of external factors, certain uncertainties still remain. Specifically, pavement wetness, illumination variations, and surface cleanliness may alter the apparent spectral response of asphalt pavements, which is reflected in remote sensing imagery. These factors may introduce subtle spectral variations that affect the stability of classification results, particularly when applying the framework to broader regions with different environmental conditions. Secondly, this study demonstrated the effectiveness of the proposed asphalt pavement aging assessment framework for large-scale monitoring, as only a small number of representative field spectra and a training model derived from a limited area were sufficient for successful application across a broader region. Although the two study areas were selected from newly developed and older urban districts with certain differences in pavement aging levels, surrounding environments, and traffic conditions, both areas are located in Wuhan, and thus a degree of regional homogeneity still exists. Therefore, the generalizability of the model requires further validation. In more diverse regions, where climatic conditions, traffic loading, construction materials, or maintenance practices differ significantly, the model may require additional adjustments, calibration, or multi-source training data. Finally, when the monitoring scope is expanded to a larger scale (e.g., provincial or nationwide highway networks), the volume of high-resolution remote sensing imagery becomes enormous. Large-scale data preprocessing (including atmospheric correction, orthorectification, and image fusion) and model inference require substantial computational resources. Relying solely on local data processing makes it difficult to ensure timely results, thereby limiting the efficiency of practical applications. Although this study still has certain limitations, overall, the framework offers a scientific paradigm for rapid, large-scale assessment of asphalt pavement aging, addressing key limitations of traditional methods.

Future research directions

To address the limitations of the current asphalt pavement aging assessment framework, future research can be explored in the following directions: First, future research should aim to reduce uncertainties in automatically generated classification samples and evaluate the proposed method across different climatic regions and pavement material conditions to improve its universality and generalization. Second, integrate multi-temporal or multi-condition remote sensing datasets and develop more robust feature optimization strategies to enable dynamic monitoring of pavement aging. Third, improve model dimensionality to better integrate spectral and spatial features of remote sensing imagery, and strengthen cloud computing–based data and feature processing capabilities to increase the efficiency of large-scale pavement monitoring.

Conclusions

As one of the most common pavement types, asphalt roads require timely assessment of aging conditions to ensure traffic safety. This study proposes a novel and highly automated framework that integrates multi-endmember spectral unmixing, automatic sample generation, and 1D-CNN to efficiently identify asphalt aging levels over multiple regions. From the experimental results and analysis, the following conclusions are derived:

-

1.

The combined use of two- and three-endmember models enables more accurate decomposition of complex mixed pixels.

-

2.

A spatial neighborhood filter based on the FLG was applied to optimize the sample space, thereby improving sample quality and enhancing model stability.

-

3.

The model achieved high-accuracy assessments of asphalt pavement aging across multiple regions, confirming both its strong generalization ability and the overall effectiveness of the proposed framework.

-

4.

Through timely identification of the spatial distribution and proportions of different asphalt pavement aging stages, early-warning information can be provided to support preventive maintenance planning. This approach helps reduce the high costs and risks of large-scale rehabilitation, thereby offering important value for pavement management.

Overall, the proposed framework provides a scientific approach for rapid, large-scale assessment of asphalt pavement aging, addressing key limitations of traditional methods while supporting visualization of aging patterns and aiding in maintenance planning. In future work, we aim to explore the integration of multi-temporal data and further enhance the generalization capacity of multi-dimensional models, thereby enabling dynamic monitoring of asphalt pavement aging across broad geographic regions.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bu, T. & Tang, D. Transportation infrastructure and good health in urban China. Humanit. Social Sci. Commun. 12, 1–18 (2025).

Wang, Y. Analysis on construction technology and quality control of asphalt pavement in highway engineering. J. Theory Pract. Manage. Sci. 3, 18–24 (2023).

Hu, G. et al. Assessment of intelligent unmanned maintenance construction for asphalt pavement based on fuzzy comprehensive evaluation and analytical hierarchy process. Buildings 14, 1112 (2024).

Schnebele, E., Tanyu, B. F., Cervone, G. & Waters, N. Review of remote sensing methodologies for pavement management and assessment. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 7, 1–19 (2015).

Yao, J., Wu, J., Xiao, C., Zhang, Z. & Li, J. The classification method study of crops remote sensing with deep learning, machine learning, and Google Earth engine. Remote Sens. 14, 2758 (2022).

Wang, J. et al. Research progress of optical satellite remote sensing monitoring asphalt pavement aging. Photogrammetric Eng. Remote Sens. 90, 471–482 (2024).

Mei, A., Salvatori, R., Fiore, N., Allegrini, A. & D’Andrea, A. Integration of field and laboratory spectral data with multi-resolution remote sensed imagery for asphalt surface differentiation. Remote Sens. 6, 2765–2781 (2014).

Karimzadeh, S. & Matsuoka, M. Development of nationwide road quality map: remote sensing Meets field sensing. Sensors 21, 2251 (2021).

Emery, W., Yerasi, A., Longbotham, N. & Pacifici F. 13–18.

Pan, Y. et al. Mapping asphalt pavement aging and condition using multiple endmember spectral mixture analysis in Beijing, China. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 11, 016003–016003 (2017).

Bayat, R., Talatahari, S., Gandomi, A. H., Habibi, M. & Aminnejad, B. Artificial neural networks for flexible pavement. Information 14, 62 (2023).

Chen, X., Zhang, X., Li, J., Ren, M. & Zhou, B. A new method for automated monitoring of road pavement aging conditions based on recurrent neural network. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 23, 24510–24523 (2022).

Pan, Y., Chen, X., Sun, Q. & Zhang, X. Monitoring asphalt pavement aging and damage conditions from low-altitude UAV imagery based on a CNN approach. Can. J. Remote. Sens. 47, 432–449 (2021).

Qamar, F. Urban Air Quality Monitoring Using Ground-Based Hyperspectral Imaging of Vegetation (University of Delaware, 2023).

Qureshi, W. S. et al. An exploration of recent intelligent image analysis techniques for visual pavement surface condition assessment. Sensors 22, 9019 (2022).

Wang, L., Li, Z. & Zhang, Z. City profile: Wuhan 2004–2020. Cities 123, 103585 (2022).

Li, J., Gong, J., Guldmann, J. M. & Yang, J. Assessment of urban ecological quality and Spatial heterogeneity based on remote sensing: a case study of the rapid urbanization of Wuhan City. Remote Sens. 13, 4440 (2021).

Lu, Y., Liu, Y., Huang, D. & Liu, Y. Evolution analysis of ecological networks based on spatial distribution data of land use types monitored by remote sensing in Wuhan urban agglomeration, China, from 2000 to 2020. Remote sensing 14, 2618 (2022).

Zhang, R. et al. The innovation effect of intelligent connected vehicle policies in China. IEEE Access. 10, 24738–24748 (2022).

Ahmad, M., Khedmati, M., Mensching, D., Hofko, B. & Haghshenas, H. F. Aging characterization of asphalt binders through multi-aspect analyses: A critical review. Fuel 376, 132679 (2024).

Cantrell, S. J. et al. System Characterization Report on the WorldView-3 Imager (Report No. 2331 – 1258, (US Geological Survey, 2021).

Panđa, L., Radočaj, D. & Milošević, R. Methods of land cover classification using Worldview-3 satellite images in land management. Tehnički Glasnik. 18, 142–147 (2024).

Jackson, R. S., Wang, Q. & Lien, J. Data preprocessing method for the analysis of spectral components in the spectra of mixtures. Appl. Spectrosc. 76, 81–91 (2022).

Munsell, A. H. A Color Notation: a measured color system, based on the three qualities Hue, Value and ChromaDigiCat,. (2022).

Tan, K., Jin, X., Du, Q. & Du, P. Modified multiple endmember spectral mixture analysis for mapping impervious surfaces in urban environments. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 8, 085096–085096 (2014).

Yao, Y. et al. Remotely estimate the cropland fractional vegetation cover using linear spectral mixture analysis and improved band operations. Int. J. Remote Sens. 46, 3466–3486 (2025).

Fan, F. & Deng, Y. Enhancing endmember selection in multiple endmember spectral mixture analysis (MESMA) for urban impervious surface area mapping using spectral angle and spectral distance parameters. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 33, 290–301 (2014).

Alavipanah, S. K. et al. The shadow effect on surface biophysical variables derived from remote sensing: a review. Land 11, 2025 (2022).

Eshetie, S. M. Exploring urban land surface temperature using Spatial modelling techniques: a case study of addis Ababa city, Ethiopia. Sci. Rep. 14, 6323 (2024).

Omia, E. et al. Remote sensing in field crop monitoring: A comprehensive review of sensor systems, data analyses and recent advances. Remote Sens. 15, 354 (2023).

Zhang, X. et al. Comparison of the applicability of JM distance feature selection methods for coastal wetland classification. Water 15, 2212 (2023).

Sun, H., Wang, L., Lin, R., Zhang, Z. & Zhang, B. Mapping plastic greenhouses with two-temporal sentinel-2 images and 1d-cnn deep learning. Remote Sens. 13, 2820 (2021).

Wang, C. et al. GCFC: Graph convolutional fusion CNN network for Cross-Domain Zero-Shot extraction of winter wheat map. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observations Remote Sensing (2024).

Abriha, D., Srivastava, P. K. & Szabó, S. Smaller is better? Unduly nice accuracy assessments in roof detection using remote sensing data with machine learning and k-fold cross-validation. Heliyon 9 (2023).

Sajid, M. Impact of Land-use change on agricultural production & accuracy assessment through confusion matrix. Pakistan J. Science 74 (2022).

Gong, X., Gu, H., Qian, G., Cai, J. & Zhong, C. Correlation between the performance of asphalt fine aggregate matrix and the performance of Hot-Asphalt mix under ultraviolet aging. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 37, 04025212 (2025).

Zhen, T. et al. Multiscale evaluation of asphalt aging behaviour: A review. Sustainability 15, 2953 (2023).

Wang, H. et al. Assessment of asphalt pavement aging condition based on GF-2 high-resolution remote sensing image. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 18, 014528–014528 (2024).

Acknowledgements

All authors are grateful for the funding support of the projects.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2023YFB3907105), the project “Intelligent Recognition of Highway Landslides and Debris Flows and Route Selection Application Research” (Grant No. KJFZ-2024NZ-042KJ), and the project “Key Technologies for Multi-source Remote Sensing Monitoring and Health Assessment of Highway Bridges” (Grant No. KJFZ-2024NZ-041KJ).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Y. and S.Y.; methodology, J.Y., Q.X.and F.Y.; software, J.Y.; validation, J.Y., Q.X. and F.Y.; investigation, J.Y., Q.X. and F.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Y. and S.Y.; and writing—review and editing, F.Y. and S.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yao, J., Xu, Q., Yu, F. et al. The remote sensing method for large-scale asphalt pavement aging assessment with automated sample generation and deep learning. Sci Rep 15, 45432 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29966-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29966-4