Abstract

Long-term fertilisation can alter soil nutrient dynamics, yet the persistence and redistribution of phosphorus (P) fractions following the cessation of combined nitrogen (N) and P inputs remain poorly understood. This study investigated how 71 years of P-only and N + P fertilisation, followed by a 3-year cessation, affected soil inorganic P fractions and associated chemical properties in a mesic South African grassland. Nitrogen-containing treatments caused severe acidification (pH decline from 4.66 to 3.36) and depletion of exchangeable Ca and Mg, whereas P-only fertilisation did not alter soil pH but increased Ca availability. These chemical shifts produced distinct P redistribution patterns: N + P treatments accumulated Fe-P and reductant-P, while P-only treatments promoted Ca-P formation. Following cessation, soluble P equilibrated across treatments, but stable Fe-P and reductant P remained high (77–122% above the control), indicating strong legacy P persistence. Two complementary PCA approaches confirmed that soil pH and exchangeable Mg were the primary drivers (PC1 = 94.2% variance) of variation in soil chemistry and strongly correlated with shifts in Fe- and reductant-P. Overall, the findings highlight that nitrogen-induced acidification – not P inputs alone – controls the long-term fate of soil P in this grassland. Effective management of acidic grassland must therefore integrate soil pH regulation with P fertilisation strategies to enhance legacy P utilization and maintain soil fertility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mineral fertilisers are often applied to improve productivity in grassland ecosystems and inevitably affect soils. Long-term experiments are crucial in understanding soil response to fertiliser application, thus assisting in providing appropriate recommendations for nutrient management in grassland ecosystems. Phosphorus (P) is essential for plant growth and development, but is often deficient in soils, especially older more weathered soils of the tropics and southern hemisphere1,2. The majority of soil total P exists in insoluble and fixed forms, such as humus P, insoluble Ca-, Fe-, and Al-phosphates, and P fixed by hydrous oxides and silicate clays3. Consequently, mineral fertilizers are applied to maintain or increase the amount of plant-available phosphorus (P) and compensate for P losses through plant uptake and to a less extent leaching and surface runoff4,5.

While long-term P fertilisation increases soil P content, repeated P fertilization often results in overapplication and build-up of P that exceeds plant requirements. Of added P, only 10–36% is taken and utilised by the plant in the year of application while the rest is retained in the soil by sorption and/or precipitation reactions thus increasing build-up of residual soil P over time6,7. This accumulated P can saturate the soil P sorption capacity8 and become susceptible to loss from land to water by erosion of particulates or dissolved P in runoff, contributing to eutrophication of water bodies9,10. Therefore, understanding P chemistry in managed ecosystems is crucial for optimizing P supply while minimizing potential environmental impacts11.

Understanding how P fractions change following cessation of long-term fertilisation is crucial for predicting P availability and environmental risk. Previous studies on fertiliser cessation in grasslands have mainly investigated effects on grassland productivity12,13,14,15. Some studies have reported a decline in bioavailable inorganic P pools after P fertilisation was discontinued16,17. Soil P testing can diagnose whether available P falls short of plant requirements; however, when P addition ceases, we have a limited understanding of the dynamics of P that remains. Managing soil P levels to optimal ranges requires understanding how different P fractions respond when fertilisation stops, particularly to develop proper guidelines to avoid negative impacts on yields.

Phosphorus fertilisers are often applied in combination with N fertiliser to improve P use efficiency due to enhanced root development and P uptake18,19. This synergistic effect extends to enzyme activity as N fertilization increases acid phosphatase activity in strongly weathered soils, thereby accelerating the transformation of organic P into plant-available forms20. Evidence of this enhanced P cycling was observed by Scheuss et al.21 at this same Ukulinga grassland site, where N + P treatments resulted in greater aboveground P stocks than N-only application. However, long-term and/or high rates of N application, particularly ammonium-based fertilisers, can lead to soil acidification22,23. Soil acidity promotes mobilization of Fe and Al23, consequently increasing soil P adsorption to Fe and Al hydroxides and redistribution of soil inorganic P fractions24,25. The effect of N fertilization on P dynamics has been reported to either improve P use efficiency18 or induce P limitations26, with the latter particularly related to soil acidification associated with ammonium-based N fertisers as ammonium sulphate.

Soil carbon and phosphorus biogeochemistry is strongly coupled, particulary in nutrient limited soils[27] . Soil organic matter plays a dual role in P cycling as it serves as both a major reservoir for organic P and influences inorganic P dynamics through its effects on P sorption capacity and mineralisation processes28. Long-term N and P fertilisation can substantially alter soil organic carbon accumulation through enhanced plant growth and increased carbon inputs. For example, increased net productivity has been reported at Ukulinga grassland following N fertilization29,30, The interactions between soil organic matter and metal oxides complicate P dynamics by altering phosphate sorption characteristics and fraction distribution [31]. Understanding these relationships is important to elucidate the effects of fertilization and its cessation on soil P fractions. However, there are limited studies on these aspects, especially those focusing on the effect of N + P fertiliser cessation.

Phosphorus fractionation provides an effective approach for investigating soil P availability, transformation processes, and potential for environmental transport32. A comprehensive understanding of P transformation processes is vital for enhancing P utilization efficiency, reducing fertiliser inputs, and mitigating P losses to the environment. Long-term field experiments offer a valuable resource for investigating P availability and the fixing capacity of P fertilizer in soil over extended time. Despite extensive research on phosphorus dynamics under long-term fertilisation, there remains a limited understanding of how cessation of combined N and P fertilisation influences the redistribution and persistence of soil inorganic P fractions in acidified grasslands. Most studies have either focused on short-term responses or isolated P or N effects, with few addressing their interactive and legacy impacts on soil P chemistry, especially under semi -arid mesic grassland systems such as Ukulinga. This study therefore, aims to fill this gap by quantifying how long-term fertilisation and its cessation reshape P fractionation patterns and related soil chemical properties in an acidified grassland ecosystem.

We hypothesized that long-term nitrogen fertilisation would affect P fractionation patterns through acidification-mediated changes in soil chemistry. The objectives of this study were to (i) quantify how long-term ammonium sulphate application affects soil P fractionation; and (ii) assess the persistence of acidification-induced P changes following fertilization cessation.

Materials and methods

Study site

The study was conducted in a long-term grassland trial located at Ukulinga research farm of the University of KwaZulu-Natal in Pietermaritzburg, South Africa (29° 24′E, 30° 24′S).

The area is semi-arid with a mean annual precipitation of 790 mm and is located on a plateau at 838 m a.s.l33. The vegetation is characterised as southern tall grass veld (KwaZulu-Natal hinterland thornveld), an open savanna of Acacia Vachellia sieberiana with patches of Hyparrhenia hirta L34. The soil is classified as a Acrisol according to the world refence base (WRB), derived from localized dolerite intrusions into shale parent material35. These soils are acidic (pH in H2O: 5.5) with high stocks of total organic C (7.3 kg C m− 2) and total N (0.47 kg N m− 2) in the upper 15 cm Schleuss et al.35. The site experiences warm summers and mild winters, with temperatures ranging from range from 8.8 °C in July to 26.4 °C in February, respectively36.

Experimental design

The experiment was established in 1951 with the application of nitrogen, phosphorus and lime as the main treatments, with an initial average soil pH of 5.737. Throughout the 71-year experimental period, the grassland was managed with annual mowing in late winter (August – September), with biomass removed from the plots. No irrigation was applied, and the site was protected from grazing by large herbivores. This study focused specifically on unlimed plots receiving phosphorus (P) and phosphorus + nitrogen (N + P) treatments. The experiment was laid out in a randomized block design with 9.0 × 2.7 m size plots replicated three times37. Nitrogen fertiliser was applied annually as ammonium sulphate at 70, 141 and 211 N kg/ha while phosphorus was applied annually as super-phosphate at 336 kg (equivalent to 28 kg P/ha) with the exception of the control plots.

In 2019, each treatment was subdivided into two equal sub-plots (4.5 × 2.7 m), with fertilization continued on one subplot (denoted with F- fertilised) but ceased in the other (denoted with C–ceased). The following treatments were selected for this study: (1) Control (0 kg P or N fertilizer/ha); (2) PF (superphosphate at 28 kg P/ha); (3) PC (superphosphate at 28 kg P/ha - CEASED); (4) N1PF(ammonium sulphate at 70 kg N/ha + superphosphate at 28 kg P/ha); (5) N1PC(ammonium sulphate at 70 kg N/ha + superphosphate at 28 kg P/ha - CEASED); (6) N2PF(ammonium sulphate at 141kgN/ha + superphosphate at 28kgP/ha); (7) N2PC(ammonium sulphate at 141 kg N/ha + superphosphate at 28 kg P/ha - CEASED); (8) N3PF (ammonium sulphate 211 kg N/ha + superphosphate at 28 kgP/ha); (9) N3PC (ammonium sulphate 211 kg N/ha + superphosphate at 28 kgP/ha - CEASED).

Sample collection

Soil samples were collected in July 2022, representing the end of a 3-year cessation period for the ceased subplots. Samples were collected at 0–10 cm depth using an auger, with multiple cores taken from each plot and combined to form a composite sample. The samples were air dried for 4 days by spreading them on a soil tray, sieved through a 2 mm sieve. Soil samples were then analyzed for exchangeable Ca and Mg, total C and pH according to Non- Affiliated Soil Analysis Committee38. This analysis uses ammonium acetate (pH 7) for the extraction of exchangeable cations, which is then quantified with atomic absorption spectrophotometry (Varian 2600). The soil pH is measured using a 1:2.5 ratio of soil: 1 M KCL, and total C with the LECO TruMAC CNS Autoanalyser (2012).

Phosphorus fractionation

Phosphorus fractions in the soil were determined following a method for non-calcareous soils by Zhang and Kovar39. This method was specifically developed and validated for acidic soil conditions, making it appropriate for this study. Soluble and loosely bound P was extracted from a 1 g of soil using 50 ml of 1 M ammonium chloride (NH4Cl). The soil residue was then treated with 50 ml of 0.5 M ammonium fluoride (NH4F) to extract Al-P. Fe-P was extracted from the same residue by adding 50 ml of 0.1 M sodium hydroxide (NaOH). Reductant soluble P was extracted by adding 40 ml of 0.3 M Na3C6H5O7.2H2O and 5 ml of 1 M NaHCO3 to the residue and heating at 85 °C on a water bath for 15 min. One gram of Na2S2O4 was added after heating followed by rapid stirring while continuously heating the samples for another 15 min. The extract was filtered with a Whatman No.1 filter paper and the soil residue washed twice using 25 ml saturated sodium chloride (NaCl). Thereafter the soil residue was treated with 0.25 M sulphuric acid (H2SO4) and shaken for 1 h to determined calcium bound P. The concentration of P was determined using phosphor-molybdate method40.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R-studio version 4.4.1. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the effects of different treatments on the studied soil properties and P fractions. Treatment means were compared using Tukey’s HSD test, with significant differences determined at p < 0.05. Two separate principal component analyses (PCA) were conducted to distinguish between the environmental drivers and the phosphorus (P) fraction responses within the studied soils. The first PCA was performed on soil chemical variables (soil pH, exchangeable Ca and Mg, and total organic carbon) to identify the dominant gradients influencing P dynamics. The second PCA was performed exclusively on soil inorganic P fractions (soluble and loosely bound P, Al–P, Fe–P, Reductant–P, and Ca–P) to explore the redistribution patterns among these pools. This separation allowed for clearer interpretation of cause–effect relationships, with the soil PCA representing the driving environmental factors and the P-fraction PCA representing the response of P pools to these factors. Both PCAs were conducted using the FactoMineR and factoextra packages in R (v4.3.2), after verifying sampling adequacy (Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin > 0.5) and sphericity (Bartlett’s test p < 0.05). Variables with communalities < 0.5 were excluded to improve factor clarity. Components were retained following the latent root criterion (eigenvalues > 1.0) and interpreted based on variable loadings ≥ 0.5.

Results

Soil chemical properties

Soil pH and exchangeable bases

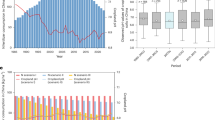

Treatments effects were highly significant for soil pH (F = 73.58, p < 0.001). Soil pH decreased progressively with increasing N application, with N1PF (3.65 ± 0.10), N2PF (3.54 ± 0.05) and N3PF (3.36 ± 0.11) having the lowest pH compared to the control (4.66 + 0.02). However, long-term P-only fertilization did not affect soil pH in either the fertilised (PF) or ceased (PC) treatments compared to the control (Fig. 1).

Some chemical properties of the grassland soil following long-term N and P fertilization and cessation. P = Phosphorus fertiliser (super-phosphate at 28kgP/ha); N1P = Ammonium sulphate (70 kg N/ha) + superphosphate; N2P = ammonium sulphate (141 kg N/ha) + superphosphate; N3P = ammonium sulphate (211 kg N/ha) + superphosphate; F = fertilised; C = ceased. Error bars represent the standard error, and different letters show statistical significance (p < 0.05).

Figure 1. Some chemical properties of the grassland soil following long-term N and P fertilization and cessation. P = Phosphorus fertiliser (super-phosphate at 28 kg P/ha); N1P = Ammonium sulphate (70 kg N/ha) + superphosphate; N2P = ammonium sulphate (141 kg N/ha) + superphosphate; N3P = ammonium sulphate (211 kg N/ha) + superphosphate; F = fertilised; C = ceased.

There was a significant effect of treatments (F = 90.71, p < 0.001) on exchangeable Ca which was lower in all N-fertilised treatments compared to P-only (11.79 ± 0.79 cmolc/kg) and the control (10.13 ± 0.70 cmolc/kg). Exchangeable Ca was in the order N1PF (4.87 ± 0.82 cmolc/kg) > N2PF (2.29 ± 0.26 cmolc/kg) = N3PF (0.88 cmolc/kg). Treatments significantly affected exchangeable Mg (F = 177.2, p < 0.001). The control (9.49 ± 0.85 cmolc/kg) recorded the highest Mg and was comparable to PF (6.72 ± 0.17 cmolc/kg).

Exchangeable Ca was significantly higher under N1PC (8.10 ± 0.46 cmolc/kg) compared to the corresponding actively fertilised plot (N1PF) and comparable to the control (10 13 ± 0.70 cmolc/kg). The cessation of other N + P treatments (N2PC and N3PC) had no effect on exchangeable Ca (p > 0.05). Exchangeable Mg increased significantly in all N + P ceased plots compared corresponding actively fertilised treatments. Upon cessation of P-only fertilization (PC), both exchangeable Ca (9.02 ± 0.79 cmolc/kg) and exchangeable Mg (4.78 ± 0.34 cmolc/kg) were significantly lower than under continued P fertilization (PF). The PC treatment showed no significant difference from control and N1PC for Ca, but was comparable only to N1PC for Mg.

Soil organic C

Treatments were significant again for total soil carbon (F = 114.8, p < 0.001) (Fig. 1). Soil organic C increased significantly under higher N application rates, with N2PF and N3PF (6.58 ± 0.06%) showing highest values compared to the control and P-only (5.57 ± 0.04%). P-only (PF) had significantly higher soil organic carbon than the control.

The cessation of P-only fertilization (PC) led to a significant decrease in total C (4.93 ± 0.02%) compared to both the control (5.28 ± 0.08%) and the PF (5.57 ± 0.04%) treatment. Cessation of N + P fertilisation had no effect on SOC which was comparable for corresponding actively fertilised plots.

Soil phosphorus fractions

Soluble P

Treatment effects were not significant for soluble P (F = 0.67, p = 0.712) (Fig. 1). All treatments showed statistically comparable soluble P levels (65–80 mg/kg). Despite numerical variation, no significant differences were detected among the control (approximately 75 mg/kg), actively fertilized treatments (N1PF-N3PF: 71–78 mg/kg), cessation treatments (N1PC-N3PC: 66–72 mg/kg), or P-only treatments (PC: 71 mg/kg; PF: 80 mg/kg).

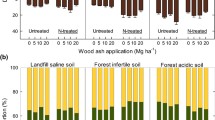

Aluminium-bound P (Al-P)

The treatment effects were high significant for Al-P (F = 18.51, p < 0.001); Fe-P (F = 23.17, p < 0.001); Reductant-P (F = 14.27, p < 0.001) and Ca-P (F = 15.73, p < 0.001). The PF treatment (78.00 ± 9.97 mg/kg) had lower Al-P, which was comparable to the control (63.80 ± 13.40 mg/kg). Actively fertilised N + P treatments had significantly higher Al-P levels compared to the control. Notably, Al-P decreased with increasing nitrogen rates among active N + P treatments: N1PF (154.00 mg/kg) = N2PF (140.80 ± 6.68 mg/kg) > N3PF (91.20 ± 10.80 mg/kg). Cessation treatments did not significantly affect Al-P levels which ranged from 98.30 to 125.20 mg/kg.

Iron-bound P (Fe-P)

Unlike Al-P, Fe-P increased under nitrogen fertilization treatments: N1PF (313.30 ± 44.00 mg/kg), N2PF (329.20 mg/kg), N3PF (369.40 mg/kg). The control showed the lowest Fe-P (122.70 ± 6.09 mg/kg). Cessation of combined N + P fertilization resulted in Fe-P levels (242.50–334.50.50.50 mg/kg) that remained substantially elevated compared to the control but were comparable to or slightly lower than their corresponding active fertilization treatments. P-only treatments (221.40 ± 30.90 mg/kg) also showed significantly higher Fe-P then the control (122.70 ± 6.09 mg/kg) with the lowest concentration. Cessation of P-only fertilization (PC: 251.40 ± 20.50 mg/kg) showed similar Fe-P levels as PF and both significantly higher than the control but lower than N + P treatments.

Reductant-P

The highest Reductant-P was observed in N3PF (314.20 ± 14.30 mg/kg) and significantly decreased with N rate but still remained higher than the control (102.90 ± 11.70 mg/kg). Cessation treatments (171.30–288.70.30.70 mg/kg) showed substantial accumulation compared to the control, with values generally maintained at levels comparable to active fertilization. Notably, PC (171.30 ± 5.22 mg/kg) and PF (172.90 ± 35.50 mg/kg) were not significantly different and had significantly lower reductant-P, than all N + P combinations and was comparable to the control.

Figure 2. Soil P fractions following long-term N and P fertilization and cessation. = Phosphorus fertiliser (super-phosphate at 28 kg P/ha); N1P = Ammonium sulphate (70 kg N/ha) + superphosphate; N2P = ammonium sulphate (141 kg N/ha) + superphosphate; N3P = ammonium sulphate (211 kg N/ha) + superphosphate; F = fertilised; C = ceased. Error bars represent the standard error, and different letters show statistical significance (p < 0.05).

Soil P fractions following long-term N and P fertilization and cessation. P = Phosphorus fertiliser (super-phosphate at 28 kg P/ha); N1P = Ammonium sulphate (70 kg N/ha) + superphosphate; N2P = ammonium sulphate (141 kg N/ha) + superphosphate; N3P = ammonium sulphate (211 kg N/ha) + superphosphate; F = fertilised; C = ceased. Error bars represent the standard error, and different letters show statistical significance (p < 0.05).

Calcium-bound P (Ca-P)

Ca-P showed a distinctly different pattern from other P fractions. The PF treatment exhibited exceptionally high Ca-P (80.33 ± 8.06 mg/kg), more than doubling the control (35.83 ± 8.93 mg/kg) and significantly exceeding all other treatments. Active N + P treatments maintained moderate and comparable Ca-P levels (40.75 to 50.40 mg/kg) that were significantly higher than the control. Cessation of N + P treatments showed intermediate comparable Ca-P levels: N1PC (52.83 ± 2.98 mg/kg), N2PC (44.00 ± 2.98 mg/kg), and N3PC (43.33 ± 3.56 mg/kg), all significantly elevated above the control. However, the cessation of P-only - PC (52.78 ± 4.74 mg/kg) showed significantly lower Ca-P than corresponding fertilised treatment (PF) but remain higher than the control.

Principal component analysis

Principal component analysis was performed to summarize relationships among soil properties and phosphorus fractions across treatments (Fig. 3). The first two components (PCs) of the soil PCA explained 85% (PC1) and 9.8% (PC2) of the total variance, respectively. Soil pH (0.97), exchangeable Mg (0.97) contributed strongly and positively to PC1 (Supplementary Table S1), together representing the primary axis of variation. Exchangeable Ca also loaded positively while SOC exhibited a strong negative loading on PC1. Distinct treatment clusters were evident, with fertilised and cessation plots separating clearly from the control.

Principal component analysis (PCA) showing treatment-related patterns in (a) soil chemical properties and (b) phosphorus (P) fractions after long-term N and P fertilization and cessation. Ellipses represent 95% confidence intervals around treatment group centroids. In (a), soil variables (pH, exchangeable Ca and Mg, and total C) are projected as vectors illustrating their contribution to the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2). In (b), P fractions (soluble and loosely bound P, Al–P, Fe–P, reductant–P, and Ca–P) are displayed similarly.

The PCA for P fractions explained 45.8% (PC1) and 28.9% (PC2) of the total variance. Fe-P and reductant-P loaded strongly on PC1 (0.92 and 0.93), respectively), whereas Ca-P (0.73) and soluble P (0.77) were positively aligned with PC2 (Supplementary Table S1). Al-P showed moderate loadings on both components (−0.52 on PC1 and 0.51 on PC2). Similar to the soil PCA, there was a clear separation of treatment clusters along both PC1 and PC2.

Figure 3. Principal component analysis (PCA) showing treatment-related patterns in (a) soil chemical properties and (b) phosphorus (P) fractions after long-term N and P fertilization and cessation. Ellipses represent 95% confidence intervals around treatment group centroids. In (a), soil variables (pH, exchangeable Ca and Mg, and total C) are projected as vectors illustrating their contribution to the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2). In (b), P fractions (soluble and loosely bound P, Al–P, Fe–P, reductant–P, and Ca–P) are displayed similarly.

Correlation analyses confirmed significant relationships between soil chemical properties and P fractions. The PCA1 scores of P fractions were highly and negatively correlated with soil pH (r =−0.88, p < 0.001) and exchangeable Mg (r = −0.92, p < 0.01). Distinct treatment clusters were observed in both PCA plots, with fertilisation and cessation plots separating clearly from the control.

Discussion

Effect of long-term fertilisation on soil properties and P fractions

The soil pH values below 4 in the N + P treatments (Fig. 1) indicate that long-term (71 years) continuous fertilisation with N + P led to significant soil acidification, particularly at higher N rates. This acidification became more severe with increasing N application rates, causing a unit drop in soil pH from 4.66 in the control to 3.36 in the N3PF treatment. The severe acidification in N + P treatments resulted in the displacement and loss of exchangeable bases, as evidenced by the lower concentrations of exchangeable Ca and Mg (Fig. 1). The effect was most pronounced under the highest rate of N, where exchangeable Ca decreased dramatically from 10.13 cmolc/kg in the control to 0.88 cmolc/kg in the N3PF treatment.

The increased SOC when P was combined with the highest rate of N could be attributed to enhanced plant growth and biomass production (518 g/m2) as previously reported by Fynn and O’Connor41, leading to higher carbon inputs to the soil. All the N + P treatments showed remarkable carbon stability after cessation which can be attributed to acidification-induced protection mechanisms, where organo-mineral associations physically protect carbon from microbial decomposition by restricting enzyme access.

For P-only treatments, the continued decline in SOC after cessation (from 5.57% in PF to 4.93% in PC) suggests persistent alterations in carbon cycling pathways. When P fertilization ceases, the microbial communities previously selected under high-P conditions likely shift their metabolic strategies toward mining organic-matter-associated phosphorus, thereby accelerating carbon decomposition. This metabolic shift is supported by findings reported by Magadlela et al.42 of increased phosphatase enzyme activities in unfertilised treatments compared to P-only plots at the same site. Additionally, the competition between phosphate and organic matter for mineral sorption sites likely influences carbon persistence, as P outcompetes dissolved organic matter for adsorption sites on Fe/Al oxides due to phosphate’s stronger inner-sphere bonding mechanism compared to organic matter’s weaker outer-sphere interactions [58]. This competitive exclusion effect would be particularly pronounced in P-only treatments, potentially reducing carbon protection and increasing vulnerability to microbial decomposition.

The distribution of P among different fractions provides insights into the fate of applied P in this long-term experiment. The N + P treatments showed dramatic increases in Fe-P and Al-P fractions, particularly at higher N rates, indicating that severe soil acidification facilitated P binding to Fe and Al oxides. This can be explained by the fact that soil inorganic P is dominated by Al-P and Fe-P in acidic soils25,43. This response of inorganic P has been reported by similar studies44,45,46,47,48. The preferential accumulation of P in Fe-P rather than Al-P fractions in the highly acidic N + P treatments can be explained by the pH-dependent nature of P adsorption mechanisms. According to Horanyi and Joo49 and Tanada et al.50 phosphate adsorption on Al oxides reaches maximum efficiency around a soil pH 4, while Fe oxides maintain high P adsorption capacity even below pH 3.5. Furthermore, the high P concentrations in these treatments may have approached the adsorption maxima on Al oxides, as suggested by Huang et al.51, leading to preferential binding with Fe oxides. The P-only fertilization significantly altered the distribution of P fractions without inducing acidification observed in N + P treatments. There seems to be limited Al-P formation in these non-acidified soil conditions as this fraction was comparable between PF and the control. However, significantly higher Fe-P P-only plots suggest that added P is rapidly transformed into less labile P bound to Fe oxides52,53,54. The correlation between Fe-P and Reductant-P (r = 0.86) indicates progressive occlusion of P within Fe oxide structures, creating increasingly stable pools. This is also supported by no significant changes in soluble P across all treatments, though PF (80 mg/kg) displayed highest numeral value (Fig. 2). Moreover P-only treatment also had significantly higher Fe-P and reductant-P compared to the control. Long-term P only and N + P at (N1 and N2 rates) resulted in significantly high Ca-P than the control due to lower extent of acidification. Ca-P in P-only treatment (80.33 mg/kg) more than doubled the control (35.83 mg/kg) reflecting adequate exchangeable calcium levels (Fig. 1) creating favourable conditions for calcium phosphate formation.

The total P accumulated across all fractions in N + P treatments showed a progressive increase with higher N application rate with 790 mg/kg, 844 mg/kg and 885 mg/kg for N1PF, N2PF and N3PF while 633 mg/kg was recorded for P-only. This significant accumulation of P in different fractions across fertilised treatments represents a substantial build-up of soil P, raising concerns about potential P losses through leaching and runoff. While this accumulated P, often referred to as “legacy P”, can serve as a long-term source of P for plant uptake, it also poses risks if mobilised and transported to water bodies10,55. Management implications of this P accumulation, however, may vary with fertilization regime. For example, in N + P treatments, acidification enhanced P retention through Fe/Al-P and Reductant-P fractions which may temporarily reduce leaching risks. However, adverse effects of severe soil acidification on soil aggregation already observed in this site22 could potentially increase particulate P loss, especially with great total P accumulation.

Effect of fertiliser cessation on soil properties and P fractions

The slight increase in soil pH following the cessation of N + P fertilisation suggests the beginning of a natural recovery process from severe acidification, supported by a significant increase in exchangeable Ca (N1PC) and Mg compared to continued fertilization. However, the persistence of very low pH values (< 4) in all ceased N + P treatments indicates that soil acidification remains substantial after 3 years without additional ammonium sulphate inputs indicating slow recovery process especially without base cation replenishment.

The response of P fractions to fertilisation cessation provides insights into the short-term dynamics of soil P transformation. Although not statistically significant, the lower numerical values of soluble P across all ceased treatments compared to continued fertilization indicate a response of this labile P fraction to changes in P inputs consistent with previous studies reporting a decline in labile P pools following cessation of fertilisation16,17. In contrast, the stable P fractions (Al-P, Fe-P, reductant P) remained significantly high in all N + P ceased treatments compared to the control, due to persistent acidic soil conditions after long-term fertilisation. Figure 2 shows that cessation of P-only fertilisation resulted in notable redistribution between Al-P and Ca-P fractions, favouring the formation of the former, which showed an increased, although not statistically significant (Fig. 2). This suggests a dissolution of previously formed Ca-P, with released P subsequently binding to aluminium oxides.

Multivariate patterns in soil phosphorus fractions and chemical properties

Soil pH emerged as a critical driver within this system, displaying a strong positive loading on PC1 (0.97), which accounted for the vast majority (94.2) of total variance (Fig. 3). This strong gradient reflects the cumulative effect of long-term fertilisation and subsequent cessation on soil acidity and associated cation chemistry. The alignment of pH with exchangeable Mg on the positive side of PC1 confirms that base cation availability co-varies with pH buffering, while plots subjected to prolonged N fertilisation clustered towards the negative axis indicative of acidification-driven cation depletion.

This acidification gradient provides a coherent explanation for the observed redistribution among inorganic P fractions. The strong negative correlation of soil pH with Fe-P and reductant-P (Supplementary Table S1) supports enhanced sorption of phosphate to Fe and Al oxides under acidic conditions, consistent with findings by Tan et al.56 In contrast, Al-P displayed a complex pattern with moderate negative loading on PC1 (−0.515) and substantial positive loading on PC2 (0.507), suggesting a non-linear response to acidification – initially increasing but declining under severe acidification conditions. This indicates that phosphate adsorption on Al oxides may have reached a maximum efficiency before Fe-P dominates (Horanyi and Joo49 and Tanada et al.50.

Meanwhile, the positive loadings of Ca-P and soluble P with PC2 (0.732 and 0.767, respectively) suggest that these fractions are influenced by factors beyond acidification gradient, likely linked to calcium availability. This aligns with high Ca concentrations observed in P-only treatments (Fig. 1), where Ca-P accumulation occurred despite only minor pH changes relative to the control. Calcium in known to induce phosphate precipitation forming Ca-P phases in soils57.

Total organic carbon exhibited a strong negative loading on PCI (−0.789), aligning with metal-bound P fractions rather than exchangeable cations (Fig. 3). This association implies that organic matter stabilization may occur through the formation of ternary complexes – a mechanisms previously described in acidic soils31,58. Collectively, these findings illustrate the central role of soil acidity and Ca-Fe-Al interactions in governing redistribution of P fractions following fertilisation and nutrient cessation.

This study demonstrates that effects of long-term fertilization and its cessation on soil P dynamics cannot be understood through simple input-output relationships but must be viewed within the broader context of soil chemical evolution. It is important to note that our study captured only a snapshot of soil P status after 3 years of cessation rather than tracking changes over time, which represents a limitation in fully understanding the temporal dynamics of P transformation following cessation. Nevertheless, the comparison between fertilised and ceased treatments provides valuable insights into the short-term response of soil P fractions to the cessation of long-term fertilisation. Long-term studies with plant update and productivity data are needed to determine how long the legacy effects of accumulated P persist and how they influence grassland productivity and environmental quality over extended periods.

Conclusion

The 71-year experiment shows that nitrogen fertilisation has been the dominant force shaping soil chemical properties and P dynamics in this grassland system. Nitrogen fertiliser significantly acidified the soil, depleted base cations, and shifted P from soluble and Ca-bound pools towards more stable Fe and reductant-bound forms. In contrast, P-only fertilisation increased Ca-P without causing marked acidification. Three years after fertiliser cessation, soluble P had largely equilibrated across treatments, yet legacy P remained strongly expressed, with stable P pools persisting at 77–122% above control levels. Carbon responses also differed by treatment, with N + P maintaining more stable C pools while P-only cessation resulted in notable C declines. Multivariate analysis supported these treatments effects, with soil pH and exchangeable Mg explaining most of the variation in soil chemistry and strongly correlated with P fraction distribution.

Overall, the findings highlight that nitrogen-driven acidification – note P inputs alone governs long-term P retention and transformation, and effective management of acidic grassland soils requires strategies that jointly address soil Ph, P availability, and carbon stability. However, given the limitations of the current study, future research should focus on tracking longer-term dynamics of P transformation and carbon cycling following cessation, integrating plant and microbial P components, and developing targeted management strategies to optimise the utilisation of legacy P while minimising environmental risks and promoting soil carbon storage.

Data availability

The data collected analysed and used during the study are available from the corresponding author at reasonable request.

References

Helfenstein, J. et al. Combining spectroscopic and isotopic techniques gives a dynamic view of phosphorus cycling in soil. Nat. Commun. 9(1), 3226. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-018-05731-2. (2018).

Sharpley, A. N. et al. Future agriculture with minimized phosphorus losses to waters: research needs and direction. Ambio 44 (S2), 163–179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-014-0612-x (2015).

Stevenson, F. J. & Cole, M. A. Cycles of Soil: Carbon, Nitrogen, Phosphorus, Sulfur, Micronutrients. 2nd Edition, Wiley, New York, 448. (1999).

Ayaga, G., Todd, A. & Brookes, P. C. Enhanced biological cycling of phosphorus increases its availability to crops in low-input sub-Saharan farming systems. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 38 (1), 81–90 (2006).

Bauke, S. L. et al. Subsoil phosphorus is affected by fertilization regime in long‐term agricultural experimental trials. Eur. J. Soil. Sci. 69 (1), 103–112 (2018).

Syers, J. K., Johnston, A. E. & Curtin, D. Efficiency of soil and fertilizer phosphorus use: reconciling changing concepts of soil phosphorus behaviour with agronomic information. FAO Fertilizer Plant. Nutr. Bull. 18. 108. (2008).

Dhillon, J., Torres, G., Driver, E., Figueiredo, B. & Raun, W. R. World phosphorus use efficiency in cereal crops. Agron. J. 109, 1670–1677. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2016.08.0483 (2017).

Schoumans, O. F. & Chardon, W. J. Phosphate saturation degree and accumulation of phosphate in various soil types in The Netherlands. Geoderma 237–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2014.08.015 (2015).

Cade-Menun, B. J., Doody, D. G., Liu, C. W. & Watson, C. J. Long-term changes in grassland soil phosphorus with fertilizer application and withdrawal. J. Environ. Qual. 46 (3), 537. https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2016.09.0373 (2017).

Doydora, S. et al. Accessing legacy phosphorus in soils. Soil. Syst. 4 (4), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems4040074 (2020).

Chen, S. et al. The influence of long-term N and P fertilization on soil P forms and cycling in a wheat/fallow cropping system. Geoderma 404, 115274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2021.115274 (2021).

Chiarucci, A. & Maccherini, S. Long-term effects of climate and phosphorus fertilisation on serpentine vegetation. Plant. Soil. 293, 133–144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-007-9216-6 (2007).

Hrevušová, Z. et al. Long-term dynamics of biomass production, soil chemical properties and plant species composition of alluvial grassland after the cessation of fertilizer application in the Czech Republic. Agr Ecosyst. Environ. 130 (3–4), 123–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2008.12.008 (2009).

Niinemets, Ü. & Kull, K. Co-limitation of plant primary productivity by nitrogen and phosphorus in a species-rich wooded meadow on calcareous soils. Acta Oecol. 28 (3), 345–356 (2005).

Willems, J. H. & Van Nieuwstadt, M. G. L. Long-term after effects of fertilization on above‐ground phytomass and species diversity in calcareous grassland. J. Veg. Sci. 7 (2), 177–184 (1996).

Dodd, R. J., McDowell, R. W. & Condron, L. M. Changes in soil phosphorus availability and potential phosphorus loss following cessation of phosphorus fertiliser inputs. Soil. Res. 51 (5), 427–436 (2013).

Magid, J. Vegetation effects on phosphorus fractions in set-aside soils. Plant. Soil. 149, 111–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00010768 (1993).

Grant, C., Bittman, S., Montreal, M., Plenchette, C. & Morel, C. Soil and fertilizer phosphorus: effects on plant P supply and mycorrhizal development. Can. J. Plant. Sci. 85, 3–14. https://doi.org/10.4141/P03-182 (2004).

Wen, Z. et al. Combined applications of nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers with manure increase maize yield and nutrient uptake by stimulating root growth in a long-term experiment. Pedosphere 26 (1), 62–73 (2016).

Margalef, O. et al. Global patterns of phosphatase activity in natural soils. Sci. Rep. 7, 1337 (2017).

Schleuss, P. M., Widdig, M., Heintz-Buschart, A., Kirkman, K. & Spohn, M. Interactions of nitrogen and phosphorus cycling promote P acquisition and explain synergistic plant-growth responses. Ecology 101, e03003 (2020).

Buthelezi, K. & Buthelezi-Dube, N. Effects of long-term (70 years) nitrogen fertilization and liming on carbon storage in water-stable aggregates of a semi-arid grassland soil.. Heliyon 8(1), p.e08690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08690 (2022).

Tian, D. & Niu, S. A global analysis of soil acidification caused by nitrogen addition. Environ. Res. Lett. 10, 024019. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/10/2/02401 (2015).

Celi, L., Lamacchia, S., Marsan, F. A. & Barberis, E. Interaction of inositol hexaphosphate on clays: adsorption and charging phenomena. Soil. Sci. 164 (8), pp574–585 (1999).

Gérard, F. Clay minerals, iron/aluminum oxides, and their contribution to phosphate sorption in soils—A myth revisited. Geoderma 262, 213–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2015.08.036 (2016).

Deng, Q., Hui, D., Dennis, S. & Reddy, K. C. Responses of terrestrial ecosystem phosphorus cycling to nitrogen addition: A meta-analysis. Glob Ecol. Biogeogr. 26 (6), 713–728. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12576 (2017).

Ma, X. et al. Long-term nitrogen and phosphorus fertilization reveals that phosphorus limitation shapes the microbial community composition and functions in tropical montane forest soil. Sci. Total Environ. 1, 854:158709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.158709 (2023).

Pierzynski, G. M., McDowell, R. W. & Sims, J. T. Chemistry, cycling, and potential movement of inorganic phosphorus in soils, in: Sims JT, Sharpley AN (Eds), Phosphorus: agriculture and the environment. J Am. Soc. Agron. pp 53–86. (2005).

Buthelezi, K. & Buthelezi-Dube, N. N. Long-term effects of nitrogen and lime application on plant–microbial interactions and soil carbon stability in a semi-arid grassland. Plants 14, 1302. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14091302 (2025).

Zama, N. Z. Responses of a South African mesic grassland to long-term nutrient enrichment and cessation of nutrient enrichment. PhD Thesis, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg. (2023). chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/579973731.pdf

Fink, J. R., Inda, A. V., Tiecher, T. & Barrón, V. Iron oxides and organic matter on soil phosphorus availability. Ciênc Agrotec. 40 (4), 369–379. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-70542016404023016 (2016).

Sui, Y., Thompson, M. L. & Shang, C. Fractionation of phosphorus in a Mollisol amended with biosolids. Soil. Sci. Soc. Am. J. 63 (5), 1174–1180. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj1999.6351174x (1999).

Ward, D., Kirkman, K. P., Tsvuura, Z., Morris, C. & Fynn, R. W. Are there common assembly rules for different grasslands? Comparisons of long-term data from a subtropical grassland with temperate grasslands. J. Veg. Sci. 31 (5), 780–791. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvs.12906 (2020).

Rutherford, M. C., Mucina, L. & Powrie, L. W. Biomes and bioregions of southern Africa. The vegetation of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland. Strelita, 19. South African National Biodiversity Institute. pp 30–51. (2006).

Schleuss, P. M. et al. Stoichiometric controls of soil carbon and nitrogen cycling after long-term nitrogen and phosphorus addition in a mesic grassland in South Africa. Soil Biol. Biochem. 135, 294–303 (2019).

Tsvuura, Z. & Kirkman, K. P. Yield and species composition of mesic grassland savanna in South Africa are influenced by long-term nutrient addition. Austral J. Ecol. 38, 959–970 (2013).

Scott, J. D. & Rabie, J. W. Effects of certain fertilizers on Veld at ukulinga. S Afr. J. Sci. 52 (10), 240–243 (1956).

Non-Affiliated Soil Analysis Work Committee. Handbook of Standard Soil Testing Methods for Advisory Purposes (Department of Agriculture and Development, Pretoria, 1990).

Zhang, H. & Kovar, J. L. Fractionation of soil phosphorus. Methods of Phosphorus Analysis for Soils, Sediments, Residuals, and Waters (ed. Pierzynski, G. M.) 50–59, (Manhattan, 2009).

Murphy, J. & Riley, J. P. A modified single solution method for the determination of phosphate in natural waters. Anal. Chim. Acta. 27, 31–36 (1962).

FynnRWS & O’ConnorTG Determinants of community organization of a South African mesic grassland. J. Veg. Sci. 16, 93–102 (2005).

Magadlela, A., Lembede, Z., Egbewale, O. & Olaniran, A. The metabolic potential of soil microorganisms and enzymes in phosphorus-deficient KwaZulu-Natal grassland ecosystem soils. Appl. Soil. Biology 181, 104647 (2023).

Asomaning, S. K. Processes and factors affecting phosphorus sorption in soils. In ‘Sorption in 2020s’. (Eds G Kyzas, Lazaridis N), IntechOpen: London, UK. (2020). https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.90719

Zhou, J. et al. Influences of nitrogen input forms and levels of phosphorus availability in karst grassland soils. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 8, 343283. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2024.1343283 (2024).

Crews, T. E. & Brookes, P. C. Changes in soil phosphorus forms through time in perennial versus annual agroecosystems. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 184, 168–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2013.11.022 (2014).

Schefe, C. R. et al. 100 years of superphosphate addition to pasture in an acid soil—current nutrient status and future management. Soil. Res. 53 (6), 662–676. https://doi.org/10.1071/SR14241 (2015).

von Sperber, C., Stallforth, R., Du Preez, C. & Amelung, W. Changes in soil phosphorus pools during prolonged arable cropping in semiarid grasslands. Eur. J. Soil. Sci. 68, 462–471. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejss.12433 (2017).

Lu, X. et al. Long-term application of fertilizer and manures affect P fractions in Mollisol. Sci. Rep. 1, 14793. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-71448-2 (2020).

Horanyi, G. & Joo, P. J. Some peculiarities in the specific adsorption of phosphate ions on hematite and γ-Al2O3 as reflected by Radiotracer studies. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 247, 12–17. https://doi.org/10.1006/jcis.2001.8103 (2002).

Tanada, S. et al. Removal of phosphate by aluminum oxide hydroxide. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 257, 135–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9797(02)00008-5 (2003).

Huang, X., Foster, G. D., Honeychuck, R. V. & Screifels, J. A. The maximum of phosphate adsorption at pH 4.0: why it appears on aluminum oxides but not on iron oxides. Langmuir 25 (8), 4450–4461. https://doi.org/10.1021/la803302m (2008).

Johan, P. D., Ahmed, O. H., Omar, L. & Hasbullah, N. A. Phosphorus Transformation in Soils Following Co-Application of Charcoal and Wood Ash. Agron https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy11102010 (2010).

Zhang, T. Q., MacKenzie, A. F., Liang, B. C. & Drury, C. Soil test phosphorus and phosphorus fractions with long-term phosphorus addition and depletion. Soil. Sci. Soc. Am. J. 68, 519–528. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2004.5190 (2004).

Crews, T. E. & Brookes, P. C. Changes in soil phosphorus forms through time in perennial versus annual agroecosystems. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 184, 168–181 (2014).

Sharpley, A. N. et al. Managing agricultural phosphorus for protection of surface waters: issues and options. J. Environ. Qual. 23 (3), 437–451. https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq1994.00472425002300030006x (1994).

Tang, Z. et al. Mechanisms and implications of phosphate retention in soils: insights from batch adsorption experiments and geochemical modeling. Water 17 (7), 998. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17070998 (2025).

Geng, Y. et al. Phosphorus biogeochemistry regulated by carbonates in soil. Environ. Res. 214(2), 113894. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2022.113894.

Kaiser, K. & Guggenberger, G. Mineral surfaces and soil organic matter. Eur. J. Soil. Sci. 54, 219–236. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2389.2003.00544.x (2003).

Acknowledgements

No additonal person contributed to the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.N. conceptualized the research idea, provided supervision, conducted data analysis and prepared the manuscript.Z. conducted soil sampling and soil analysis data analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Buthelezi-Dube, N.N., Sithole, Z. Acidification-driven soil phosphorus fractionation following long-term fertilization and cessation at ukulinga mesic grassland in South Africa. Sci Rep 16, 513 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29986-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29986-0