Abstract

East Asian non-neosauropodan eusauropods have been central to the study of the evolution of Middle to Late Jurassic sauropod dinosaurs. Despite their remarkable diversity, the fragmentary condition of many taxa and the insufficiency of phylogenetic data for many specimens have hindered the study of continental-scale paleobiogeographic relationships. We described a new mamenchisaurid, Mamenchisaurus sanjiangensis sp. nov., based on a single partial skeleton from the early Oxfordian fossil site of Chongqing (Southwest China). M. sanjiangensis phylogenetically recovered as a diverged mamenchisaurid, shares a relatively near relationship with most other Mamenchisaurus. This new taxon is supported by an exclusive combination of characters that highlights strong convergences with members of the neosauropods. That indicates the niche overlap further enhances the competition between mamenchisaurids and neosauropods. Mamenchisaurids potentially developed a strategy to maintain dominance in East Asia before the recoupling of the East Asian and European sub-plates in the Early Cretaceous.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sauropod dinosaur diversity reached an apparent peak in the Late Jurassic1,2,3, comprised many wide geographically distributed non-neosauropodan eusauropod lineages (e.g., mamenchisaurids, turiasaurians), and primarily of a wide array of near-globally distributed members of neosauropodan clades (Diplodocoidea and Macronaria)4,5,6,7,8,9. The Late Jurassic sedimentary units of China preserve rich sauropod records, and most of them are dominated by mamenchisaurids, although the exact neosauropodan remains are widely recognized from early Middle Jurassic8,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. The dominance of Asian sauropod faunas is quite different from that of contemporaneous European and North and South American Formations (e.g.,6,7). Moreover, most of the Late Jurassic Asian sauropod diversity comes from the deposits assigned to the lower parts, particularly near the Middle-Late Jurassic transition period10,11,14,15,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,25,26,27,32,33.

The Middle-Late Jurassic Upper Shaximiao Formation of Sichuan Basin bears no fewer than three genera, including Daanosaurus zhangi, Qijianglong guokr, M. hochuanensis, and M. youngi11,17,18,19,23. Qijianglong guokr, M. hochuanensis, and M. youngi are generally widely accepted as nested in Mamenchisauridae in many phylogenetic analyses (e.g.,6,8,9,27,29,30). Daanosaurus zhangi is reported as a macronarian19, whereas the recent phylogenetic analyses suggest this taxon is a potential mamenchisaurid9. Despite an abundance of materials, the anatomy of some/related taxa from the Late Jurassic of China remains to be further assessed to clarify their morphological features and evolutionary interrelationships.

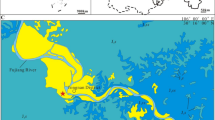

Here, we report a new Mamenchisaurus sauropod, sp. nov., based on articulated posterior cervical, dorsal, sacral, and anterior caudal vertebrae and appendicular skeletons from the Late Jurassic Upper Shaximiao Formation of Chongqing, southwestern China (Fig. 1). Anatomical comparison and phylogenetic analysis show that the new taxon is a member of Mamenchisauridae and shares relative kinship with many other Mamenchisaurus. It phylogenetically recovered in the later-diverged position in this clade. This discovery further enriches the diversity of the Late Jurassic eusauropod assemblage in East Asia. It provides additional information to help understand the evolutionary radiation of non-neosauropodan eusauropods in East Asia.

Geographic and geological setting of the palaeontological site. (A) geological map of Hochuan (Chongqing, China); (B) Type specimen of Mamenchisaurus sanjiangensis sp. nov. in the field; (C) the field map of the elements; (D) the compose of the elements. The base map of the world is from https://vemaps.com/. The skeletal reconstruction with copyright Scott Hartman (2022) (https://www.skeletaldrawing.com/sauropods-and-kin). The figure was drawn by X.X.R., using CorelDRAW 2021 (Version number: 23.0.0.363, URL link: http://www.coreldrawchina.com). Cv, cervical vertebra; D, dorsal vertebra; S, sacral vertebra.

Results

Systematic paleontology

Dinosauria Owen, 1842.

Saurischia Seeley, 1887.

Sauropodomorpha von Huene, 1932.

Sauropoda Marsh, 1878.

Eusauropoda Upchurch, 1995.

Mamenchisauridae Young and Chao, 1972.

Mamenchisaurus Young, 1954.

Mamenchisaurus sanjiangensis sp. nov. (Figs. 1 and 2)

Skeletal anatomy of Mamenchisaurus sanjiangensis sp. nov. (A,N) Cv17 and left fibula in anterior view; (B,C,D,G) Cv17-D3, D6-D9, D11, and Cd3 in left lateral view; (E) D12-S5 in right lateral view; (F,K) Cd1 and left femur in anterior view; (H) Cd4 in ventral view; (I) ilia in left view, the two element are combined and the right one are noted with red dotted line; (J) left pubis and ischium in lateral view; (L) left femur in medial view; (M) left tibia in posterior view. 4th, fourth trochanter of femur; ACDL, anterior centrodiapophyseal lamina; act, acetabulum; amp, ambiens process; af, accessory foramina; avc, anteroventral concavity of ilium; bif, PCDL, bifurcated posterior centrodiapophyseal lamina; cc, cnemial crest; CPOL, centropostzygapophyseal lamina; CPRL, centro-prezygapophyseal lamina; Cv, cervical vertebra; D, dorsal vertebra; dac, distal anterior concavity; di, diapophysis; fc, fibular condyle; fh, femoral head; ila, iliac articulation; isp, ischial peduncle; lm, lateral malleolus; lr, lateral ridge; mm, medial malleolus; nsp, neural spine; SPDL, spinodiapophyseal lamina; SPOL, spinopostzygapophyseal lamina; SPRL, spinoprezygapophyseal lamina; tc, tibial condyle; ts, tibial ligament muscle scar; tp, transverse process; p.a., parapophysis; pf, lateral pneumatic fossa or foramen; posta, postacetabular process; poz, postzygapophysis; PPDL, paradiapophyseal lamina; PRDL, prezygodiapophyseal lamina; prea, preacetabular process; PRPL, prezygoparapophyseal lamina; prz, prezygapophysis; puf, pubic foramen; pup, pubic peduncle; S, sacral vertebra.

Etymology

The species name refers to the Hechuan District, where the fossil site is from, at the meeting point of the Jialing, Fu, and Qu Rivers in Chongqing (Fig. 1). ‘sanjing’ means the three rivers (Jialing, Fu, and Qu Rivers) in Chinese Pinyin.

Holotype

CIP V0001. Two cervical vertebrae, 12 dorsal vertebrae, five sacral vertebrae, four caudal vertebrae, left and right ilia, pubes, and ischia, left femur, tibia, and fibula.

Locality and horizon

This specimen was excavated in the Hechuan district, Chongqing, southwest China. The remains were found in purplish-red silty mudstones near the middle portion of the Upper Shaximiao Formation. Traditionally, a general Callovian-Oxfordian age was inferred for this formation, whereas the exact age for this formation is still controversial34,35. The horizontal potentially belongs to the early Oxfordian.

Diagnosis

Mamenchisaurus sanjiangensis is a mamenchisaurid sauropod with the following unique combination of character states (autapomorphies are marked by *): the posterior cervical and anterior dorsal neural spines are bifurcated; an additional fossa exists on the base of the prezygodiapophyseal lamina (PRDL) on the posterior cervical and anterior dorsal vertebrae*; epipophyseal-prezygapophyseal lamina (EPRL) is preserved on the posterior cervical and anterior dorsal vertebrae; an accessory lamina extends from the prezygapophysis to the diapophysis on the anterior dorsal vertebrae*; height of neural arch/posterior centum articular surface is prominently increasing from anterior to posterior dorsal series; several accessory laminae divided the spinodiapophyseal fossa (sdf) on the dorsal vertebrae; the spinodiapophyseal lamina (SPDL) is bifurcated dorsally from Dorsal (D)3 to D7, and the two branches constituted the lateral margins of a secondary deep fossa on sdf*; five sacral vertebrae are completely fused with ‘platform’ -shaped distal portion of neural spines; lateral excavation exists on the lateral surface of sacral vertebrae; the anterior caudal centra are procoelous; dorsal margin of ilium is semicircular-shaped; the femoral head is dorsoventrally projected; the transverse width/anteroposterior length of femoral mid-shaft is about 2.6. Besides, this taxon belongs to the genus Mamenchisaurus shares the following features at least: the articular surface of anterior caudal centra is procoelous; the internal structure of the presacral vertebrae is camellate.

General comments

As discussed in many recent articles (e.g.,8,9,20,30), most researchers recognize the presence of a monophyletic eusauropod lineage, including Mamenchisaurus, predominant in the Middle to Late Jurassic East Asian terrestrial herbivore faunas (e.g.,4,5,6,8,9,23,24,27,28,29,30,36,37). Traditionally, this group has been assigned the family name Mamenchisauridae with several long-neck genera11, and the breaking of Pangaea during the late Middle Jurassic further enhanced the dominance of this clade (e.g.,1,14,24,29,38). However, more and more phylogenetic analyses indicate that the clear constituents and precise nomenclature are still controversial, let al.one the internal relationship or even the existence of this clade (e.g.,8,23,27,29,30). Fortunately, many recent works have significantly shed light on the spatiotemporal evolution of the relative East Asian taxa in this era (e.g.,8,9,27), but still far more perfectly. Thereinto, the putative ‘Mamenchisaurus’ branch includes more than three species (e.g., M. sinocanadorum, M. hochuanensis, M. youngi) at a diverged position of Mamenchisauridae in many phylogenetic works. These taxa share more than 17 cervical and four to five sacral vertebrae relative to other mamenchisaurids11. However, several genera (e.g., Xinjiangtitan, Qijianglong, Chuanjiesaurus, Wamweracaudia) usually nested in this taxonomic unit rather than only Mamenchisaurus spp.26, and the type species (M. constructus) often falls outside of this clade in many phylogenetic analyses8,9,27. Pending a comprehensive re-evaluation of the species of Mamenchisaurus spp. (especially the M. constructus) is the key step to approach the explicated relationships and the further phylogenetic definition. This time, we still use the Mamenchisauridae term here for the dominating clade of the Middle-Late Jurassic East Asian eusauropods that includes Omeisaurus, Mamenchisaurus, and related forms in this study. In our Systematic Paleontology sections, we continue to use the term ‘Mamenchisaurus’, assigning to the diverged branch of Mamenchisauridae including M. youngi, M. hochuanensis, M. sanjiangensis, and related forms, because we do not wish to list a new one as part of a formal taxonomic hierarchy in the interim till further research for the explicit phylogenetic definition. Besides, the term ‘core Mamenchisaurus-like taxa (CMT)’, created by Moore et al. (2020) as an interim measure pending further work, is also used to name the clade that M. sanjiangensis nested by using the referred matrix. Additionally, the bone-bearing horizon of M. hochuanensis is much higher than that of M. sanjiangensis; it is much closer to the boundary of Suning and Upper Shaximiao formations than that of M. sanjiangensis. However, these two specimens were all excavated in the same region (Hechuan District), both horizons are from the Upper Shaximiao Formation, and the two taxa share many morphological features with other Mamenchisaurus specimens (as mentioned in the following sections). Moreover, to avoid further nomenclatural confusion among the named members of Mamenchisauridae, we still use Mamenchisaurus as the generic name for this specimen.

Description and comparisons

The two posterior cervical vertebrae are well preserved (Fig. 2 and see Supplementary Data (SD) 1 for measurements). The centra of cervical vertebrae are opisthocoelous, and the articular surfaces are dorsoventrally compressed, as occurred in many non-neosauropodan eusauropods (e.g., Cetiosaurus oxoensis, Qijianglong guokr, M. youngi, O. maoi) and most of the neosauropodan taxa such as Apatosaurus ajax, Bellusaurus sui, Rapetosaurus krausei, Saltasaurus loicatus5,18,23,39,40. The articular surfaces of parapophyses are ventrolaterally projected and prominently anteroposteriorly extended. The lateral pneumatic fossa is anteroposteriorly extended with an acute angle on the posterior margin. Moreover, a secondary excavation occupied the anterior two-thirds of the lateral fossa. The height of the neural arch is less than the height of the centrum, reaching about 0.73 (Cervical (Cv)1) and 0.85 (Cv2) times the height of the posterior articular surface of the centrum. This ratio is also below 1.0 in most of the non-neosauropodan taxa, such as M. hochuanensis (Cv18: 0.68), O. tianfuensis (Cv17: 0.77, T5701), and Shunosaurus lii (Cv12: 0.87, T5404). The prezygapophyses are distinctly anteriorly extended beyond the anterior articular ball. The diapophyses are a robust element and project ventrolaterally. Corresponding to the prezygapophysis, the postzygapophyses are dorsolaterally inclined. The epipophyses are situated at the posterior portion of the postzygapophyses near the posterior margin of the vertebrae. This feature is present in the cervical vertebrae of most sauropods6. These rugose tubercles are sub-elliptical in outline and do not extend beyond the posterior margin of the postzygapophysis, as most other early-branching eusauropods. The centro-prezygapophyseal lamina (CPRL) is vertically extended and broadened transversely from the centrum to the prezygapophysis. It is not ‘truly’ divided, resembling that in many other mamenchisaurids such as M. youngi, Qijianglong guokr, Xinjiangtitan shanshanesis18,23,25, and other diverged neosauropods (e.g., Dashanpusaurus, Europasaurus, Sauroposeidon, Suuwassea)28,41,42,43. The anterior centrodiapophyseal lamina (ACDL) is a thin element that extends from the anterodorsal margin of the centrum to the anteroventral surface of the diapophysis. By contrast, the posterior centrodiapophyseal lamina (PCDL) expands anteroposteriorly and is much more robust than the ACDL. PRDL is a thin and relatively expanded lamina that extends ventrolaterally from the distal of the prezygapophysis and diapophysis. Moreover, this lamina is bifurcated on D12 (Fig. 2). The postzygodiapophyseal lamina (PODL) is stouter than the PRDL, extending from the distal of the postzygapophysis to the base of the diapophysis. Several fossae exist on the sdf near the basal-middle portion between the prezygapophysis and diapophysis. Notably, some fossae are deeply invaginated, which makes an elliptical opening on the right side of the PRDL of the preserved two cervicals. By contrast, this foramen is absent and the fossae on neural arch are not well-marked in M. hochuanensis11. The neural spine is bifurcated, resembling many other mamenchisaurids such as M. youngi, M. hochuanensis, M. anyuensis, Xinjiangtitan shanshanesis11,16,18,25. The two metapophyses are forming a narrow ‘V’-shaped outline, as occurred in Lingwulong shenqi, M. hochuanensis11,24,28. The median tubercle is absent on the bifurcated posterior cervical neural spines. An anteroposterior projected lamina observed in the sdf is part of the EPRL feature, as in other eusauropods (referred to as27,28). It divided the sdf into several secondary excavations. This condition resembles that in Euhelopus zdanskyi, and some other eusauropod taxa such as Klamelisaurus gobiensis, Xinjiangtitan shanshanesis, Hudiesaurus sinojapanorum, Dashanpusaurus dongi8,25,27,28,38.

Twelve articulated dorsal vertebrae are well preserved (Fig. 2 and SD1). D1–D5 are presumed to be the anterior dorsal vertebrae as the parapophysis is still touching the centrum, and the neural spines are bifurcated. We identify D6–D9 as the middle dorsal vertebrae because the neural spines are single. Besides, the SPRLs of D6 to D9 are prominently anteriorly extended, which makes the dorsal margin of this lamina about 45° to the horizontal. By contrast, the SPRL is generally dorsoventrally projected along the anterolateral margin of each neural spine of D10 to D12. D10–D12 are suggested as the posterior dorsal vertebrae, as the transverse processes are short and laterally projected compared with those on D1–D9. The centra of dorsal vertebrae are opisthocoelous, and the articular surfaces are dorsoventrally compressed in the first three dorsal vertebrae, and the articular surfaces of subsequent dorsal vertebrae are transversely compressed. This condition also occurs in Omeisaurus tianfuensis and M. youngi18,44. Whereas the dorsal centra of M. hochuanensis are transversely compressed11. A weakly developed midline keel on the anterior to middle dorsal vertebrae. The parapophyses gradually rise under the prezygapophysis at the middle dorsal vertebrae. The lateral pneumatic fossa occupies the anterodorsal portion of the lateral surface with an acute posterior margin, except D9 and D11 (quadrangle shape on D9 and D11). Moreover, a small accessory excavation is positioned above the lateral fossa with an elliptical-shaped outline on D9. By contrast, the posterior margins of lateral fossae on anterior and middle dorsal centra of M. hochuanensis, M. youngi, Qijianglong guokr, and Xinjiangtitan shanshanesis are rounded11,18,23,26. The height of the neural arch is generally similar to the height of the centrum in the anterior dorsals, and generally increases in the middle and posterior dorsal series. This condition is similar to that in M. youngi and Xinjiangtitan shanshanesis, whereas the ratio increases in the anterior and middle dorsal series of M. hochuanensis and decreases in posterior dorsals. The prezygapophyses are supported ventrally by a transversely broadened CPRL. This lamina is not divided and extends, as in the cervical series. The diapophyses are robust, situated on the dorsal margin of the neural arches, and project laterally. This condition resembles that in M. youngi, Jingiella dongxingensis, and Omeisaurus spp18,29,40,44,45. , and many other eusauropods. By contrast, those in M. hochuanensis, Klamelisaurus gobiensis, Euhelopus zdanskyi, and some taxa (e.g., Neuquensaurus australis, Saltasaurus loricatus) share dorsolaterally projected diapophyses18,27,38,46,47. The postzygapophyses are dorsolaterally inclined as in other sauropods. The epipophyses exist, and this feature is present in the cervical vertebrae of most sauropods, whereas it is uncommon in the dorsal vertebrae6. The posterior centrodiapophyseal lamina (PCDL) expands anteroposteriorly, and it is much more robust than the ACDL. Noting that the PCDL of D1 is bifurcated (Fig. 2), the PRDL and PODL are stout and extend from the base of the prezygapophysis and postzygapophysis, respectively. The centropostzygapophyseal lamina (CPOL) is not divided, extends ventromedially, and supports the postzygapophyses ventrally. The fossae are strongly invading the surface of zygapopysis, which makes many secondary fossae and even foramina (e.g., the opening on ACDLs of D4 and D5). The neural spines are dorsally and slightly posteriorly oriented. The neural spines of anterior dorsal vertebrae are bifurcated, and the rest are single ones, as occurs in many other mamenchisaurids such as M. hochuanensis11, and M. youngi18. The bifurcated neural spine is first observed in Middle Jurassic eusauropods (e.g. Dashanpusaurus, Lingwulong), and becomes familiar in the Late Jurassic48. The dorsal and lateral margins of the metapophyses of anterior bifurcated dorsal vertebrae share a narrow ‘V’-shape outline in anterior view, as mentioned in the posterior cervical vertebrae. Notably, the SPDL are bifurcated dorsally from D3 to D7, and the two branches constitute the lateral margins of a secondary deep fossa on the sdf. The triangular aliform processes project laterally, but are weakly developed. The laminae of the EPRL feature are strongly extended from the anterior extension of the epipophyses to the posterior margin of the prezygapophyses. This condition resembles that in Euhelopus zdanskyi, and many eusauropod taxa such as Klamelisaurus gobiensis, Xinjiangtitan shanshanesis, Hudiesaurus sinojapanorum8,25,28,38. As aforementioned, this prominent feature is prominent on the posterior cervical vertebrae.

The sacrum of M. sanjiangensis is composed of five sacral vertebrae (Fig. 2 and SD1), a condition widely distributed among non-somphospondylan neosauropods (e.g.,4,49), and some non-neosauropodans such as many members of Mamenchisauridae (e.g., M. youngi). Whereas some of mamenchisaurids share four sacral vertebrae, such as M. hochuanensis and Omeisaurus spp. (exp. O. Jiaoi)18,44,50. The five sacral centra are fused, with their boundaries marked by low, rounded transverse ridges. The anterior and posterior articular surfaces of the transversely compressed. This nature is widely preserved in non-neosauropodan eusauropods (e.g., Omeisaurus spp.). The ventral surfaces of the sacral vertebrae are anteroposteriorly concave and transversely convex. The lateral pneumatic fossa extends anteroposteriorly on the lateral surface. This condition is also observed on Jingiella dongxingensis, and most of neosauropods (e.g., titanosauriforms), whereas other mamenchisaurids (e.g., M. hochuanensis) have not been reported to have this feature. The sacral rib generally occupies the whole anterior portion of the centrum of each sacral vertebra. This stout element extends laterally and dorsally from the ventral portion of the centrum. It occupies the vast majority of parts of the neural arch and is nearly vertically projected. The sacral rib is roughly ‘C’-shaped with acetabular and alar ‘arms’ in anterior or posterior views. The intracostal fenestra (ICF) is positioned at the middle portion of the sacral rib. The adjacent acetabular arms of the sacral ribs contact one another distally to form the ‘sacricostal yoke’. This anteroposteriorly extended bar that contacts the base of the ilium, as occurred in eusauropods51. All the sacral neural spines are co-ossified throughout their height (except the distalmost of Sacral 5), and form a continuous plate dorsally. This fusion occurs between the SPRL and SPOL of adjacent neural spines. These are transversely compressed with a plate-like outline, maintaining this depth along the sacral vertebral series. The SPDL is absent. The lateral surfaces of the neural spines are irregularly concave, with several fossae occupied.

The preserved four caudal vertebrae are the anteriormost ones and are well preserved, except for the badly preserved Caudal (Cd)2. Centra of the preserved caudal vertebrae are procoelous (Figs. 2 and SD1). The centra share concave anterior articular surfaces and a medium convex posterior articular surface. Procoelous caudal centra are also preserved in other Mamenchisaurus, and many neosauropodans (e.g.,16,18,22,23). In anterior or posterior view, the anterior caudal centra are transversely compressed as occurred in most of the diverged mamenchisaurids (e.g., M. youngi, M. hochuanensis, Xinjiangtitan shanshanesis)11,18. By contrast, the sub-circulated caudal centra are hosted in early-branching mamenchisaurids such as O. tianfuensis44. Besides, the dorsoventrally compressed ones are generally observed in neosauropodans (e.g., Europasaurus)41. The centra of anterior caudal vertebrae are solid, as in most sauropods. The anterior-most portion of the prezygapophyses is extended beyond the anterior articular surfaces of the preserved caudal centra. The transverse process is situated on the dorsal margin of the centrum, and the dorsal portion extends to the lower portion of the neural arch. Therein, the transverse process of Cd1 is strongly dorsally and laterally extended, as is that in other sauropods (e.g., M. youngi). It is laterally and slightly ventrally projected, and that in Cd3 and 4 share a ‘wing-like’-shaped transverse process. This condition is similar to that in many mamenchisaurids such as O. tianfuensis, Wamweracaudia keranjei, and M. youngi6,18,44. The laminations of the preserved anterior caudals are well developed compared with those of other Late Jurassic sauropods. The SPRL, SPOL, PRDL, and PODL are observed in the preserved caudal vertebrae. It is worth noting that there is an accessory lamina extended from the base of SPRL to the middle portion of PRDL on the first caudal vertebrae. The dorsal portion of the postzygapophyseal centrodiapophyseal fossa (pocdf) is distinctly inwardly concaved. Superadding the prominent fossa on the base of the neural spine near the lowest portion of both prezygapophyses and an accessory fossa existed on the dorsoposterior portion of the sdf on Cd1, it seems these are relative to the pneumatic structures. The distal end of neural spines is laterally expanded and transversely convex with two shallow concavities on both sides. Laterally, the neural spines project dorsoposteriorly and are slightly curved, as occurred in other eusauropodans. These are plate-like in outline and roughly quadrilateral in cross-section. Two dorsally widened lateral excavations are present on both lateral surfaces of the neural spine in Cd1, whereas these fossae are absent in M. hochuanensis11. The triangular lateral process is absent on the neural spine, as in most other sauropods.

Both ilia are partly preserved (Fig. 2 and SD1). The pubic peduncle of the left ilium is missing, and the right one is partly preserved, with the middle to posterior portions of the iliac blade missing. Laterally, the dorsal margin of the ilium is semicircular, as in many eusauropods (e.g., O. tianfuensis, Dashanpusaurus dongi, Apatosaurus ajax), and this condition is regarded as a synapomorphy of this clade28. The preacetabular process orients anterolaterally to the body axis, as in most of eusauropodans except some titanosaurs (e.g., Epachthosaurus sciuttoi)52. It projects beyond the anterior end of the pubic peduncle in lateral view, resembling that in many early-diverging sauropod taxa such as Shunosaurus lii, and O. tianfuensis44,53. The highest point of the iliac dorsal margin is situated posterior to the base of the pubic peduncle, resembling that in most of the non-macronarian eusauropodans. The same point is situated anterior to the base of the pubic peduncle in most of macronarians, such as Tastavinsaurus sanzi54. The distal end of the postacetabular process is rounded. Medially, the dorsal portion of the ilium is coarsely textured along the articular surface of the sacral ribs. The acetabulum is internally concave, and the middle portion is broader than the anterior and posterior portions. The ventrolateral surface of the postacetabular process lacks a prominent brevis fossa, a condition that occurs in all sauropods55. The pubic peduncle is anteroventrally curved. The transverse width is generally similar to the iliac lobe, with the base and distal portions slightly broader than the middle part. Compared with the pubic peduncle, the ischial peduncle is strongly reduced, as many eusauropods such as Camarasaurus lewisi56, and most other gravisaurians24. The distal end of the ischial peduncle is transversely compressed. The articular surface of the peduncle is sub-triangular in outline.

The two pubes are well preserved (Fig. 2 and SD1). The length of the iliac articular surface is about 0.21 times the proximodistal length of the pubic shaft. The iliac articulation is transversely compressed with a shallow concavity anteroposteriorly extended. The length of the ischial articulation is about 0.4 times the proximodistal length of the pubic shaft. This ratio below 0.5 is a synapomorphy for non-neosauropodan sauropods. The ischial articulation is medioposteriorly projected, with an ‘S’-shaped outline. The acetabular articulation extends anteroposteriorly and transversely. The pubic foramen is situated on the upper portion of the shaft near the ischial articulations, and the long axis is generally parallel to the long axis of the pubic shaft. It is elliptically shaped in outline and projects medioposteriorly, resembling that in Euhelopus zdanskyi and many other diverged eusauropodans38. The pubic shaft has a comma-shaped outline in horizontal cross-section. Ventrally, the medial surface of the pubic shaft is slightly convex, compared to the mildly concave lateral surface. The distal end is slightly extended relative to the shaft. The posterior margin of the distal end of the left pubis is more transversely extended than the anterior margin. It makes the distal end share a sub-triangular shape in ventral view.

The ischia of both sides are well preserved (Fig. 2 and SD1). The pubic articulation is sub-triangular in outline, with a lateromedially extended dorsal margin and a tapering ventral apex. Laterally, the margin of this articulation is strongly convex. The acetabulum is situated between the pubic and iliac articulations. It maintains approximately the same transverse width throughout its length, as occurred in most other sauropods except Spinophorosaurus nigerensis and some rebbachisaurids29,57. Laterally, the articulation for the ilium is approximately sub-circular in outline, but shares a straight anterolateral margin that meets the acetabular surface. The ‘neck’ is absent on the iliac peduncle as in most other sauropods, whereas some rebbachisaurids (e.g., Limaysaurus tessonei) share this feature29,58. Laterally, the ischial shaft is straight, with no torsion between the distal shaft and proximal plate. In anterior or posterior view, the shaft is slightly medially curved. The distal shaft is generally oval in transverse cross-section. The distal end is generally slightly expanded, similar to most other sauropods except for some rebbachisaurids with a strongly dorsoventrally expanded distal end29.

The left femur is well preserved (Fig. 2 and SD1). The femoral head is dorsomedially oriented, rises above the level of the greater trochanter, as occurred in Shunosaurus lii, Spinophorosaurus nigerensis, and many neosauropods such as Tastavinsaurus sanzi53,54,57. The femoral shaft is straight, with the distal third being slightly expanded when compared with the mid-shaft part. The fourth trochanter is situated near the medial margin of the femur, as occurred in Klamelisaurus gobiensis, O. puxiani, Yuanmousaurus jiangyiensis27,45,59. Whereas, it differs from M. youngi, O. tianfuensis, and many other sauropod taxa, such as Lourinhasaurus alenquerensis, in that the fourth trochanter is situated near the mid-sagittal plane of the femur18,44,60. The transverse width-to-femoral mid-shaft ratio of the distal femur is 2.6. This ratio is much bigger than that of other mamenchisaurids (e.g., M. youngi: about 1.5; Jingiella dongxingensis: about 1.9). Distally, the tibial condyle is anteroposteriorly larger than the fibular condyle. The distal articular surface is restricted to the distal portion of the femur, as occurred in most of sauropods, except some titanosaurs such as Neuquensaurus australis46.

The left tibia is well preserved except for some parts missing from the cnemial crest (Fig. 3 and SD1). The length of the tibial shaft is about 0.60 times the total length of the femur. This ratio is in the typical range for sauropods36. The tibial proximal end is transversely wider than the anteroposterior length, as in most of the eusauropodans, such as M. youngi18. The shape of the tibial proximal end is sub-elliptical. The cnemial crest is robust, as in other eusauropods38. The transverse width of the mid-shaft is about 2.92 times the anteroposterior length. The transverse width of the distal tibia is about 1.48 times the mid-shaft. The ratio below 2.0 is widely found in most non-macronarians24. Distally, the anteroposterior length is greater than the transverse length, with a comma-shaped outline. The posterolateral surface terminates distally with a ventral malleolus from the medial malleolus. The medial malleolus is much robust than the lateral malleolus, as is the case in M. youngi18. Posteriorly, the medial malleolus is reduced to the point that the posterior fossa for the astragalus is exposed.

The left fibula is well preserved (Fig. 2 and SD1). The proximal end is transversely compressed and convex both anteroposteriorly and transversely. The proximal tibial scar is well-marked, with many low dorsoventrally extended ridges, as occurred in other eusauropodans. The fibula shaft shares a slight sigmoid curve in posterior view. That is, its proximal portion bows a little medially, toward the tibia, and its distal portion bows slightly laterally. The lateral trochanter is situated at approximately the mid-length of the shaft, on the lateral surface. This feature is a synapomorphy found in eusauropodans more derived than Shunosaurus38. The distal end of the fibula expands both anteroposteriorly and transversely. Thereinto, the most prominent expansion is along the medial margin of the distal end, which would have contacted the lateral depression of the astragalus. The articular surface of the distal end is rugose in its central portion, and curves convexly towards its margins.

Phylogenetic analysis

To test the hypothesis that M. sanjiangensis represents a mamenchisaurid, we have scored the specimen for the main data matrix (updated from Ren et al. (2023)) and the referred data matrix of Moore et al. (2023). We have chosen the main data matrix because it is an up-to-date version of the dataset from Xu et al. (2018), which originates from the series of data sets originally produced by Carballido and colleagues, that includes scores for many Jurassic early-diverging eusauropods. Thus, it will give our specimen yield insights for the placement. Moreover, the other referred data set is from Moore et al. (2023), which is one of the largest available for mamenchisaurids that includes a broad sample of early-diverging eusauropod diversity. Thereinto, phylogenetic analyses from the main dataset were conducted to assess the affinities of M. sanjiangensis within Mamenchisauridae (Fig. 3). Our equal weights parsimony (EWP) analysis of the main dataset (SD2-4) resulted in 1158 most parsimonious trees (MPTs) with a length of 1789 steps. Mamenchisauridae is supported by nine unambiguous synapomorphies, and M. sanjiangensis shares two characters (Middle and posterior cervical vertebrae, shape of parapophysis is anteroposteriorly elongate (ch. 392); Middle dorsal centra, articular face shape is opisthocoelous (ch. 401)). Four unambiguous synapomorphies are supporting the ‘(broad-)Mamenchisaurus’, and M. sanjiangensis shares three features (articular face shape of anterior caudal centra (excluding the first) is procoelous (ch. 193); anteroposterior length of posterior condylar ball to mean average radius [(mediolateral width + dorsoventral height) divided by 4] of anterior articular surface of centrum on anterior caudal centra are greater than 0.3 (ch. 379); posterior articular surface of anterior caudal centra is convex throughout all anterior caudal vertebrae with ribs (ch. 438)). Then, the subsequently extended implied weighting (EIW) analysis resulted in 3636 MPTs with a length of 74.75233 steps. In our EIW analysis, M. sanjiangensis is situated as the diverged branching of Mamenchisauridae, generally similar to the result of the EWP analysis and supported by nine unambiguous character changes (chs. 120, 138, 169, 193, 175, 199, 375, 405, 429). Additionally, both the EWP and EIW analyses using the referred data matrix support M. sanjiangensis within the assembly of ‘mamenchisaurid’ (SD5-6).

Discussion

The specimen is diagnosable based on several autapomorphies and is named Mamenchisaurus sanjiangensis herein. In our EWP and EIW analyses using the main data matrix, it is regarded as a diverged mamenchisaurid and is supported by several unambiguous synapomorphies, such as the shape of the parapophysis on middle and posterior cervical vertebrae, which is anteroposteriorly elongate. Comprehensive records for this feature in mamenchisaurids are recognized; beyond that, it is only present in some titanosaurs. Furthermore, this taxon also shares the ‘wing-like’-shaped transverse process of the anterior caudals, which is widely observed among mamenchisaurids. Moreover, the taxon also shares some unambiguous synapomorphies with some neosauropodan clades. Thereinto, the height divided by the width of the posterior articular surface on the cervical vertebrae is between 0.9 and 0.7. The feature is widely found in macronarians such as Dashanpusaurus dongi, Camarasaurus lewisi, and Europasaurus holgeri28,41,56. It is rarely observed in non-neosauropodan eusauropods24,29, whereas it is observed in M. sanjiangensis and M. youngi. Besides, the pleurocoels in the lateral surface of sacral centra are familiar for neosauropods (e.g., Camarasaurus lewisi, Lourinhasaurus alenquerensis, Europasaurus holgeri, Tastavinsaurus sanzi, Phuwiangosaurus sirindhornae), and it is unusual in non-neosauropodan eusauropods24,29,41,54,56,62. Mamenchisaurus sanjiangensis shares synapomorphies of different clades that may indicate the species ‘mosaic’ morphological evolution and the potential convergent evolution. Additionally, Hudiesaurus sinojapanorum is recovered as a macronarian and near the position of Euhelopus zdanskyi in our study using the main dataset. Thereinto, Hudiesaurus is traditionally regarded as a mamenchisaurid8,9, and Euhelopus as a member of Euhelopodidae outside of Neosauropoda or a macronarian9,24,27,28,29,30,38. Competition can result in evolutionary changes to coexistence between competitors63, and regardless of the limited materials, heterogeneous spatial or sampling bias, these phylogenetic positions in this study possibly reflect the niche overlap, further intensifying the competition. The possible advantages engendered by the weakly extended hyposphene-hypantrum articulations, highly pneumatized vertebrae, and relatively transversely compressed femoral midshaft in M. sanjiangensis compared with other mamenchisaurids are explored. Thereinto, the internal tissue structure is camellate in the cervical to sacral centra. These traits would promote their gigantism and create a much larger feeding envelope and efficiency, even opened up trophic niches of this lineage (e.g.,64). Several CMTs share robust antebrachia, which may potentially have increased the range of motion, and further arguments indicate CMTs and titanosaurs potentially sacrificed the ability to augment food-gathering via bipedal rearing in exchange for higher locomotion speeds and reduced travel times between patchily distributed food sources8. That may have partly aggravated heterogeneous spatial and temporal sampling. Consequently, the mamenchisaurids share convergent features with the neosauropods, potentially creating their strategy to maintain dominance in East Asian before the recoupling of the East Asian and European sub-plate in Early Cretaceous.

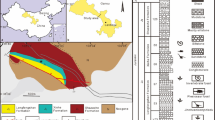

The Late Jurassic Chinese sedimentary unit has yielded evidence for at least seven sauropod genera, including more than 17 species. Additional unnamed material might indicate higher diversity (e.g.,8,27). Although the neosauropods are unambiguously proven to represent a part of sauropod diversity in Middle Jurassic East Asian terrestrial ecosystem29, most of these taxa are phylogenetically positioned as mamenchisaurids. Only three taxa are suggested as macronarians, but this is still controversial8,27,28,29. However, neosauropod dinosaurs share extremely high rates of diversification, disparity, and distribution in Late Jurassic terrestrial herbivorous faunas globally6. That indicates the Late Jurassic East Asian sauropod faunae further share strong distinctiveness and endemicity since the disconnect between Laurasia and Gondwana during the late Middle Jurassic6,24,29,65, and is crucial for the contemporaneous sauropod evolution and the subsequent period. Several other geographical regions with Late Jurassic deposits preserved diverse sauropod faunas, and brief comparisons are made below to approach the evolutionary process in this era (Fig. 4).

Paleogeographic reconstruction showing the main non-neosauropodan eusauropods (in pink), macronarians (in blue), and diplodocoids (in yellow) records. Paleogeographic reconstruction of 170 Ma from PALEOMAP. The figure was drawn by X.X.R., using CorelDRAW 2021 (Version number: 23.0.0.363, URL link: http://www.coreldrawchina.com).

Africa

Most recognized Late Jurassic African sauropod remains are reported from Tendaguru and Kadzi formations, and these others are generally too incomplete to be assigned to particular clades or confidently dated to this era6 (Mannion et al. 2019). Sauropod dinosaurs are both abundant and diverse in the Tendaguru Formation (e.g.,66). This formation had born seven Late Jurassic sauropod taxa: dicraeosaurid Dicraeosaurus hansemanni and D. sattleri (e.g.,67); (2) the brachiosaurid Giraffatitan brancai, as the new species of Brachiosaurus first, which generically differ from B. brancai then proposed the new binomial genus name68; (3) the non-titanosaurian titanosauriform/somphospondylan titanosaurian Australodocus bohetii (e.g.,69,70), that only from two associated cervical vertebrae; (4) the macronarian neosauropod Janenschia robusta (e.g.,6,29,70,71,72), that was excavated from the same location but clearly distinct at higher taxonomic levels with Tornieria africana, and the genus name replaced from the original name Gigantosaurus same as Tornieria africana (e.g.,72), and some referred elements of Janenschia possibly indicates it was recovered as a titanosauriform (/titanosaurian) or a basal eusauropod (e.g.,6,69,70); (5) the diplodocid Tornieria africana (e.g.,74), the genus name was replaced by Sternfeld (1911) and now considered as a junior synonym of Barosaurus6,73; (6) the turiasaur/basal neosauropod/non-titanosaurian somphospondylan Tendaguria tanzaniensis6,7,41,70,71,72, it also on the basis of relative limited vertebrate materials; (7) the mamenchisaurid Wamweracaudia6, based elements are originally referred to Janenschia robusta by Janensch (1929), phylogenetically shares close affinities to the contemporaneous Chinese sauropod Mamenchisaurus6,29. The sauropod dinosaur materials unearthed in the Kadzi Formation (Tithonian) of Zimbabwe are generally from the four sauropod genera Barosaurus, Brachiosaurus, Dicraeosaurus, and Tornieria75. Additionally, McPhee et al. (2016) suggested the earliest Cretaceous (Berriasian–Valanginian) or possibly latest Jurassic Kirkwood Formation of South Africa preserves fragmentary remains attributed to Diplodocidae, Dicraeosauridae, and Brachiosauridae, all of which appear closely related to taxa from the Tendaguru Formation76.

Europe

Five main areas with Late Jurassic sauropod materials have been reported: UK77,78, Spain370,72,79, Portugal80, Germany81, and France3. The most diverse European sauropod lineage is the turiasaurians, and most of the remains are found in the Iberian Peninsula7. This non-neosauropodan eusauropod clade has been known since 2006 (e.g.,7), including potential four Late Jurassic European lineages: Turiasaurus riodevensis and Losillasaurus giganteus were found at (Kimmeridgian-Tithonian) Villar del Arzobispo Formation from of Spain (e.g.,7,82); Zby atlanticus reported from Lourinhã Formation (late Kimmeridgian) of Portugal80; a possible member Amanzia greppini83, the original genus name is Ornithopsis and then reclassified as a species of Cetiosauriscus (e.g.,84), is from (early Kimmeridgian) Reuchenette Formation in Switzerland7,83. The other prosperous Late Jurassic sauropod clade is Brachiosauridae in Europe. The Portuguese Lusotitan atalaiensis from Lourinhã Formation is originally considered as a new species of Brachiosaurus85, then being assigned to its genus within Brachiosauridae5,70,86. Vouivria damparisensis was collected from middle-late Oxfordian deposits in eastern France, and phylogenetically recovered in the clade of Brachiosauridae, stratigraphically as the oldest known titanosauriform3. Aragosaurus ischiaticus, Galveosaurus herreroi were excavated in the same location from the (Kimmeridgian-Tithonian) Villar del Arzobispo Formation (e.g.,79), which phylogenetically places them as non-titanosauriform neosauropod29,86. Lourinhasaurus alenquerensis was recovered from (upper Kimmeridgian to lower Tithonian) Sobral Formation of Portugal, and phylogenetically related to it as a basal Macronarian (e.g.,29,56,61,78,85). A new specimen from the same location was erected as a new binomial Dinheirosaurus lourinhanensis by Bonaparte and Mateus (1999)87, and it was recovered as a diplodocine diplodocid (e.g.,1). Additionally, Sander et al. (2006) reported a Late Jurassic (middle Kimmeridgian) German species, Europasaurus holgeri, with diminutive body size29,80,88,89. It is generally considered a basal macronarian (e.g.,29,89) or a brachiosaurid in some phylogenetic analyses (e.g.,3).

North America

The Late Jurassic sauropod dinosaurs from North America were extremely abundant and diverse in the Morrison Formation (Oxfordian-Tithonian) of the western USA6,90. This formation represents one of the most extensive Mesozoic terrestrial depositional basins yet discovered (e.g.,91). Potentially up to 15 genera and 25 species are recognized as valid bearing in this sedimentary unit, and most of these records are diplodocids including the apatosaurines Apatosaurus (A. ajax; (A) louisae) and Brontosaurus (B. excelsus; (B) parvus; B. yahnahpin) (e.g.,92,93,94), coupled with several diplodocine genera: Barosaurus lentus, Diplodocus (D. carnegii; D. longus; D. hallorum), Galeamopus (G. hayi; G. pabsti), Kaatedocus siberi and Supersaurus vivianae, and Ardetosaurus viator (e.g.,5,61). Thereinto, Ardetosaurus viator is the least named diplodocine sauropod based on comparative anatomy95. By contrast, many other iconic sauropod lineages such as the titanosauriform Brachiosaurus altithorax68,96, the non-titanosauriform macronarian Camarasaurus (C. grandis; (C) lentus; C. supremus)36,51, and the ‘basal’ diplodocoids Amphicoelias altus and Haplocanthosaurus (H. delfsi; H. priscus), have been much longer known (based on analyses such as Ren et al.29, and the dicraeosaurid Smitanosaurus agilis and Suuwassea emilieae are recognized in this century (e.g.,97,98. Since most species of Morosaurus were subsumed into Camarasaurus in 1919 and the genus Morosaurus itself is no longer valid, the new combination Smitanosaurus agilis was proposed for the original ‘M.’ agilis (see also: 99). The three small-bodied taxa (Kaatedocus siberi, Smitanosaurus agilis, and Suuwassea emilieae) are suggested to be subadult and result in the stemward slippage as putative synonyms with Amphicoelias altus (e.g.,100), and the recent studies indicate these species are still valid and not misidentified (e.g.,101).

South America

The Late Jurassic South American sauropod faunae are dominated by neosauropods and are generally restricted to Patagonia. Two neosauropod lineages are recognized from the Cañadón Calcáreo Formation (Kimmeridgian-early Tithonian) of southern Argentina, including dicraeosaurid Brachytrachelopan mesai, Tehuelchesaurus benitezii, and a brachiosaurid (e.g.,70,72,102). Thereinto, Tehuelchesaurus benitezii was first reported as a non-neosauropod eusauropod102, and then widely accepted as a non-titanosauriform macronarian (e.g.,24,29,102).

Asia

Most of the Late Jurassic sauropod records are reported from East Asia, particularly in China, and the composition of sauropod faunas is quite different from that of contemporaneous European, North American, and South American bone-bearing units, with the dominance of non-neosauropod eusauropod (e.g.,6,29). As a paradigm, the East Asian Isolation Hypothesis (EAIH) has previously been the most accepted explanation to interpret the distinct difference between Jurassic to Early Cretaceous Asian terrestrial faunas and those elsewhere in Pangaea (e.g.,6,24,29). This hypothesis postulates that isolation of East Asia resulted in the evolution of endemic groups such as mamenchisaurids, and the absence of many sauropod lineages in this era (e.g.,23). These Chinese sauropod faunas are primarily distributed in the western part, including Xinjiang, Gansu, Sichuan, Chongqing, and Yunnan. Five species have been reported from (Callovian-Oxfordian) the Shishugou Formation: Tienshanosaurus chitaiensis10,20,24,33, Klamelisaurus gobiensis15,27, M. sinocanadorum, Bellusaurus sui12,21,103, Fushanosaurus qitaiensis32, and a small cervical vertebra was identified as a potential brachiosaurid104. Therein, the three former ones are relative to Mamenchisauridae, and Bellusaurus sui is recovered as a basal macronarian or lying outside of Neosauropoda (e.g.,6,9,27,28,29,30). Additionally, Fushanosaurus qitaiensis was reported as a titanosauriform referred to a single large femur32. Besides, the other two species from (Kimmeridgian-Tithonian) the Kalazi Formation (Hudiesaurus sinojapanorum Dong 1997, Rhomaleopakhus turpanensis Upchurch et al. 2021), and one from (Oxfordian–early Kimmeridgian) Qigu Formation (Xinjiangtitan shanshanesis Wu et al. 2013) are generally recognized as mamenchisaurids (e.g.,8,9,26). The Middle-Late Jurassic boundary and Late Jurassic strata in Sichuan Basin have been reported to contain at least four sauropod genera, including 9 species. Thereinto, M. constructus, M. hochuanensis, M. youngi, M. jingyanensis, M. sanjiangensis, and O. maoianus are reported from (Callovian-Oxfordian) the Upper Shaximiao Formation11,17,40,105. Qijianglong guokr, as a mamenchisaurid, was excavated from the Suining Formation23, and further geological surveys from the Zigong Dinosaur Museum reported the materials belong to the Upper Shaximiao Formation (unpublished). To date, the stratigraphically youngest Late Jurassic mamenchisaurid taxon is M. anyuensis from the uppermost of the Suining Formation and Penglaizhen Formation in Sichuan Basin16. Although the precise age of Penglaizhen Formation is still controversial, M. anyuensis potentially represents a diverged non-neosauropodan eusauropod in the Jurassic-Cretaceous transitional era. Moreover, Daanosaurus zhangi was the only non-mamenchisaurid sauropod named from the Upper Shaximiao Formation of Sichuan Basin as a macronarian primarily19. Whereas recent phylogenetic analysis shows this juvenile specimen was possibly recovered from Mamenchisauridae9. In the generally contemporaneous adjacent area of the Sichuan Basin, some Late Jurassic sauropod materials excavated from Gansu are suggested to refer to M. hochuanensis by further morphological comparison11. Besides, M. yunnanensis from the (Kimmeridgian-Tithonian) Anning Formation of Yunnan Province is morphologically positioned as a species of Mamenchisaurus with relatively fragmentary materials106. However, these remains have not been described in detail or included in a phylogenetic analysis. Thus, the potential mamenchisaurid position or even the validity of this taxon should be treated with caution. The recently reported mamenchisaurid Jingiella dongxingensis from Guangxi Province represents the most southern record of this lineage in China30. The prosperous mamenchisaurid-dominating East Asia, echoes with no relative mamenchisaurid record reported in the adjacent Europe or no other regionally distributed Late Jurassic European groups (e.g., turiasaurians) reported in East Asia, possibly further enhances the non-rigid Jurassic EAIH.

A partial skeleton collated from the early Late Jurassic of Chongqing, southwest China, represents a new taxon of mamenchisaurid, named Mamenchisaurus sanjiangensis. This taxon enriches the diversity of the early diverging sauropods and provides additional information to help understand the evolutionary history of sauropods in northwest China. A refined understanding of the evolutionary relationships of Middle–Late Jurassic Chinese eusauropods is pertinent to testing hypotheses concerning the isolation of East Asia from western Laurasia and Gondwana at this time and the palaeobiogeographical history of early branching sauropods and eusauropods more broadly. However, our understanding of this evolutionary stage is far from complete, and reexamination of specimens is needed for East Asian lineages to fill the ‘gaps’.

Methods

Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic analyses were carried out using TNT v. 1.5 with both EWP and EIW analyses107,108. We set a general RAM of 300 Mb and a maximum of 500,000 trees for EWP and EIW, and used a concavity constant (K) of 12 for EIW. Firstly, we using the ‘New Technology Search’: 50 search replications were used as a starting point for each hit, and the consensus was stabilized 10 times, random and constraint sectorial searches under default settings were used, five ratchet iterations and five rounds of tree fusing per replicate (‘xmult = replications 50 hits 10 css rss ratchet 5 fuse 5’). Then, we employed the most parsimonious trees (MPTs) resulting from the primary search as the starting trees for a Traditional Search using tree bisection reconnection (TBR). For both EWP and EIW analyses, we report both the absolute and the “Groups present/Contradicted” (GC) frequencies of clades on reduced strict consensus trees, based on 1000 replicates107. The latter analysis used the Traditional Search option with TBR. Character mapping was carried out in Mesquite v. 2.75.

Nomenclatural acts

This published work and the nomenclatural acts it contains have been registered in ZooBank, the proposed online registration system for the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN). The ZooBank LSIDs (Life Science Identifiers) can be resolved, and the associated information viewed through any standard web browser by appending the LSID to the prefix ‘http://zoobank.org/’. The LSIDs for this publication is LSIDurn: lsid: zoobank.org: act:3327F425-5BE9-4BA0-8571-C0B21A8EF99B.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information and Data.

References

Mannion, P. D. et al. Testing the effect of the rock record on diversity: a multidisciplinary approach to elucidating the generic richness of sauropodomorph dinosaurs through time. Biol. Rev. 86, 157–181 (2011).

Upchurch, P. et al. Geological and anthropogenic controls on the sampling of the terrestrial fossil record: a case study from the dinosauria. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 358, 209–240 (2011).

Mannion, P. D., Allain, R. & Moine, O. The earliest known titanosauriform sauropod dinosaur and the evolution of brachiosauridae. PeerJ 5, 1–82 (2017).

Wilson, J. A. Sauropod dinosaur phylogeny: critique and cladistic analysis. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 136, 217–276 (2002).

Upchurch, P., Barrett, P. M., Dodson, P. & Sauropoda. In The Dinosauria, 2nd edn, 259–322 (eds Weishampel, D. B., Dodson, P. & Osmolska, H.) (University of California Press, 2004).

Mannion, P. D. et al. Taxonomic affinities of the putative titanosaurs from the late jurassic Tendaguru formation of tanzania: phylogenetic and biogeographic implications for eusauropod dinosaur evolution. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 9, 1–126 (2019).

Royo-Torres, R. et al. Origin and evolution of turiasaur dinosaurs set by means of a new ‘rosetta’ specimen from Spain. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 191, 1–27 (2020).

Upchurch, P. et al. Reassessment of the late jurassic eusauropod dinosaur Hudiesaurus sinojapanorum Dong, 1997, from the Turpan Basin, China, and the evolution of hyperrobust antebrachia in sauropods. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 41, e1994414 (2021).

Moore, A. J. et al. Re-assessment of the Late Jurassic eusauropod Mamenchisaurus sinocanadorum Russell and Zheng, 1993, and the evolution of exceptionally long necks in mamenchisaurids. J. Syst. Paleontol. 21, 2171818 (2023).

Young, C. C. A new dinosaurian from Sinkiang. Palaeontol. Sin. (Ser. C). 2, 1–25 (1937).

Young, C. C. & Chao, X. J. Mamenchisaurus hochuanensis. In Monograph Series I. (eds Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology) 1–30 (Science Press, 1972).

Dong, Z. M. On remains of the sauropods from kelamaili Region, Junggar Basin, Xinjiang, China. Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 28, 43–58 (1990).

Dong, Z. M. A gigantic sauropod (Hudiesaurus sinojapanorum, gen. Et sp. nov.) from the Turpan Basin, China. In Sino-Japanese Silk Road Dinosaur Expedition (ed. Dong, Z. M.) 102–110 (China Ocean, 1997).

Russell, D. A. The role of central Asia in dinosaurian biogeography. Can. J. Earth Sci. 30, 2002–2012 (1993).

Zhao, X. J. A new middle jurassic sauropod subfamily (Klamelisaurinae subfam. nov.) from Xinjiang autonomous Region, China. Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 31, 132–138 (1993).

He, X. L. et al. A new species of sauropod, Mamenchisaurus anyuensis sp. nov. Proc. 30th Int. Geol. Congr. 12, 83–86 (1996).

Pi, L. Z., Ouyang, H. & Ye, Y. A new species of sauropod from Zigong, Sichuan: Mamenchisaurus youngi. In Papers on geosciences from the 30th International Geological Congress (eds Department of Spatial Planning and Regional Economy) 87–91 (China Economic Publishing House, 1996).

Ouyang, H. & Ye, Y. Mamenchisaurus youngi. In The First Mamenchisaurid Skeleton with Complete Skull, 111 (Sichuan Publishing House of Science and Technology, 2002).

Ye, Y., Gao, Y. H. & Jiang, S. A new genus of sauropod from Zigong, Sichuan. Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 43, 175–181 (2005).

Sullivan, C. et al. The search for dinosaurs in Asia. In The Complete Dinosaur. (eds Brett-Surman, M., Holtz, T. R. & Farlow, J. O.) (Indiana University Press, 2012).

Mo, J. Y. Bellusaurus sui, 231 (Henan Science and Technology Press, 2013).

Wu, W. et al. A new gigantic sauropod dinosaur from the middle jurassic of Shanshan, Xinjiang. Glob. Geol. 32, 437–446 (2013).

Xing, L. D. et al. A new sauropod dinosaur from the late jurassic of China and the diversity, distribution, and relationships of mamenchisaurids. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 35, e889701 (2015).

Xu, X. et al. A new middle jurassic diplodocoid suggests an earlier dispersal and diversification of sauropod dinosaurs. Nat. Commun. 9, 2700 (2018).

Zhang, X. Q. et al. Redescription of the cervical vertebrae of the mamenchisaurid sauropod Xinjiangtitan Shanshanesis Wu et al. 2013. Hist. Biol. 32, 803–822 (2020).

Zhang, X. Q. et al. Redescription of the dorsal vertebrae of the mamenchisaurid sauropod Xinjiangtitan shanshanesis Wu et al. 2013. Hist. Biol. 36, 49–75 (2024).

Moore, A. J. et al. Osteology of Klamelisaurus gobiensis (Dinosauria, Eusauropoda) and the evolutionary history of Middle–Late jurassic Chinese sauropods. J. Syst. Paleontol. 18, 1299–1393 (2020).

Ren, X. X. et al. Osteology of Dashanpusaurus Dongi (Sauropoda: Macronaria) and new evolutionary evidence from middle jurassic Chinese sauropods. J. Syst. Paleontol. 20, 1–72 (2022).

Ren, X. X. et al. Re-examination of Dashanpusaurus Dongi (Sauropoda: Macronaria) supports an early middle jurassic global distribution of neosauropod dinosaurs. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 610, 111318 (2023).

Ren, X. X. et al. The first mamenchisaurid from the upper jurassic Dongxing formation of Guangxi, southernmost China. Hist. Biol. 37, 465–478 (2025).

Li, N. et al. A new eusauropod (Dinosauria, Sauropodomorpha) from the middle jurassic of Gansu, China. Sci. Rep. 15, 17936 (2025).

Wang, X. R. et al. A new titanosauriform dinosaur (Dinosauria: Sauropoda) from late jurassic of Jungar Basin, Xinjiang. Glob. Geol. 38, 581–588 (2019).

Xu, X. et al. The Shishugou fauna of the Middle–Late jurassic transition period in the Junggar basin of Western China. Acta Geol. Sin (English Edition). 96, 1115–1135 (2022).

Li, Y. Q. et al. Sedimentary provenance constraints on the jurassic to cretaceous paleogeography of Sichuan Basin, SW China. Gondwana Res. 60, 15–33 (2018).

Huang, D. Y. et al. Lithostratigraphic subdivision and correlation of the jurassic in China. J. Stratigraphy. 45, 364–374 (2021).

Upchurch, P. The phylogenetic relationships of sauropod dinosaurs. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 124, 43–103 (1998).

Sekiya, T. Re-examination of Chuanjiesaurus anaensis (Dinosauria: Sauropoda) from the middle jurassic Chuanjie Formation, Lufeng County, Yunnan Province, Southwest China. Mem. Fukui Prefectural Dinosaur Museum. 10, 1–54 (2011).

Wilson, J. A. & Upchurch, P. Redescription and reassessment of the phylogenetic affinities of Euhelopus Zdanskyi (Dinosauria: Sauropoda) from the early cretaceous of China. J. Syst. Paleontol. 7, 199–239 (2009).

Upchurch, P. & Martin, J. The anatomy and taxonomy of Cetiosaurus (Saurischia, Sauropoda) from the middle jurassic of England. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 23, 208–231 (2003).

Tang, F. et al. A complete sauropod from Jingyuan, Sichuan: Omeisaurus maoianus, 128 (China Ocean Press, 2001). (2001).

Carballido, J. L. & Sander, P. M. Postcranial axial skeleton of Europasaurus Holgeri (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the upper jurassic of germany: implications for sauropod ontogeny and phylogenetic relationships of basal macronaria. J. Syst. Paleontol. 12, 335–387 (2014).

Wedel, M. J., Cifelli, R. L. & Sanders, R. K. Osteology, paleobiology, and relationships of the sauropod dinosaur Sauroposeidon. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 45, 343–388 (2000).

Harris, J. D. Cranial osteology of Suuwassea Emilieae (Sauropoda: diplodocoidea: Flagellicaudata) from the upper jurassic Morrison formation of Montana, USA. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 26, 88–102 (2006).

He, X. L., Li, C. & Cai, K. J. Omeisaurus tianfuensis. In The Middle Jurassic dinosaur fauna from Dashanpu, Zigong, Sichuan: sauropod dinosaurs, vol. 4, 143 (Sichuan Publishing House of Science and Technology, 1988).

Tan, C. et al. A new species of Omeisaurus (Dinosauria: Sauropoda) from the middle jurassic of Yunyang, Chongqing, China. Hist. Biol. 33, 1817–1829 (2021).

Otero, A. The appendicular skeleton of Neuquensaurus, a late cretaceous saltasaurine sauropod from Patagonia, Argentina. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 55, 399–426 (2010).

Powell, J. E. Osteologia de Saltasaurus loricatus loricatus (Sauropoda–Titanosauridae) Del Cretácico superior Del Noroeste Argentino. In Los Dinosaurios Y Su Entorno Biotico: Actas Del Segundo Curso De Paleontologia in Cuenca (eds (eds Sanz, J. L. & Buscalioni, A. D.) 165–230 (Institutio ‘Juan de Valdes’, 1992).

Wedel, M. J. & Taylor, M. P. Neural spine bifurcation in sauropod dinosaurs of the Morrison formation: ontogenetic and phylogenetic implications. PalArch’S J. Vertebrate Palaeontol. 10, 1–34 (2013).

Salgado, L., Coria, R. A. & Calvo, J. O. Evolution of titanosaurid sauropods. I: phylogenetic analysis based on the postcranial evidence. Ameghiniana 34, 3–32 (1997).

Jiang, S., Li, F., Peng, G. Z. & Ye, Y. A new species of Omeisaurus from the middle jurassic of Zigong, Sichuan. Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 49, 185–194 (2011).

Wilson, J. A. & Sereno, P. C. Early evolution and higher-level phylogeny of sauropod dinosaurs. Mem. Soc. Vertebr. Paleontol. 5, 1–68 (1998).

Martínez, R. D. et al. An articulated specimen of the basal titanosaurian (Dinosauria: Sauropoda) Epachthosaurus sciuttoi from the early late cretaceous Bajo barreal formation of Chubut province, Argentina. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 24, 107–120 (2004).

Zhang, Y. H. Shunosaurus lii. In The Middle Jurassic Dinosaur Fauna from Dashanpu, Zigong, Sichuan: Sauropod Dinosaurs, vol. 3, 89 (Sichuan Publishing House of Science and Technology, 1988).

Canudo, J. I., Royo-Torres, R. & Cuenca-Bescós, G. A new sauropod: Tastavinsaurus Sanzi gen. et sp. nov. From the early cretaceous (Aptian) of Spain. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 28, 712–731 (2008).

Gauthier, J. Saurischian monophyly and the origin of birds. Mem. Calif. Acad. Sci. 8, 1–55 (1986).

McIntosh, J. S. et al. A new nearly complete skeleton of Camarasaurus. Bull. Gunma Museum Nat. History. 1, 1–87 (1996).

Remes, K. et al. A new basal sauropod dinosaur from the middle jurassic of Niger and the early evolution of sauropoda. PLoS One. 4, e6924 (2009).

Salgado, L. et al. Lower cretaceous rebbachisaurid sauropods from Cerro Aguada Del León (Lohan Cura Formation), Neuquén Province, Northwestern Patagonia, Argentina. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 24, 903–912 (2004).

Lü, J. C. et al. New eusauropod dinosaur from Yuanmou of Yunnan Province. Acta Geol. Sinica. 80, 1–10 (2006).

Mocho, P., Royo-Torres, R. & Ortega, F. Phylogenetic reassessment of Lourinhasaurus alenquerensis, a basal macronaria (Sauropoda) from the upper jurassic of Portugal. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 170, 875–916 (2014).

McIntosh, J. S. Species determination in sauropod dinosaurs. In Dinosaur Systematics: Approaches and Perspective (eds. Carpenter, K. & Currie, P. J.) 53–69 (Cambridge University Press, 1990).

Martin, V. et al. Description of the type and referred material of Phuwiangosaurus Sirindhornae Martin, Buffetaut and Suteethorn, 1994, a sauropod form the lower cretaceous of Thailand. Oryctos 2, 39–91 (1999).

Pastore, A. L. et al. The evolution of niche overlap and competitive differences. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 5, 330–337 (2021).

Bates, K. T. et al. Temporal and phylogenetic evolution of the sauropod dinosaur body plan. R. Soc. Open. Sci. 3, 150636 (2016).

Poropat, S. F. et al. New Australian sauropods shed light on cretaceous dinosaur palaeobiogeography. Sci. Rep. 6, 34467 (2016).

Heinrich, W. D. The taphonomy of dinosaurs from the upper jurassic of Tendaguru (Tanzania) based on field sketches of the German Tendaguru expedition (1909–1913). Mitteilungen Aus Dem Museum für Naturkunde Berlin Geowissenschaften Reihe. 2, 25–61 (1999).

Schwarz-Wings, D. & Böhm, N. A morphometric approach to the specific separation of the humeri and femora of Dicraeosaurus from the late jurassic of Tendaguru Tanzania. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 59, 81–98 (2014).

Taylor, M. P. A re-evaluation of Brachiosaurus altithorax Riggs 1903 (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) and its generic separation from Giraffatitan Brancai (Janensch 1914). J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 29, 787–806 (2009).

D’Emic, M. D. The early evolution of titanosauriform sauropod dinosaurs. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 166, 624–671 (2012).

Mannion, P. D. et al. Osteology of the late jurassic Portuguese sauropod dinosaur Lusotitan atalaiensis (Macronaria) and the evolutionary history of basal titanosauriforms. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 168, 98–206 (2013).

Bonaparte, J. F., Heinrich, W. D. & Wild, R. Review of Janenschia Wild, with the description of a new sauropod from the Tendaguru beds of Tanzania and a discussion on the systematic value of procoelous caudal vertebrae in the sauropoda. Palaeontographica Abteilung A. 256, 25–76 (2000).

Carballido, J. L. et al. Osteology and phylogenetic relationships of Tehuelchesaurus benitezii (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the upper jurassic of patagonia. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 163, 605–662 (2011).

Janensch, W. Das Handskelett von Gigantosaurus robustus u. Brachiosaurus Brancai aus den Tendaguru-Schichten Deutsch-Ostafrikas. Centralblatt für Mineralogie, Geologie und Paläontologie. 15, 464–480 (1922).

Remes, K. Revision of the Tendaguru sauropod Tornieria Africana (Fraas) and its relevance for sauropod paleobiogeography. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 26, 651–669 (2006).

Raath, M. A. & McIntosh, J. S. Sauropod dinosaurs from the central Zambesi valley, Zimbabwe, and the age of the Kadzi formation. S. Afr. J. Geol. 90, 107–119 (1987).

McPhee, B. W. et al. High diversity in the sauropod dinosaur fauna of the lower cretaceous Kirkwood formation of South africa: implications for the Jurassic–Cretaceous transition. Cretac. Res. 59, 228–248 (2016).

Barrett, P. M., Benson, R. B. J. & Upchurch, P. Dinosaurs of dorset: part II, the sauropod dinosaurs (Saurischia, Sauropoda) with additional comments on the theropods. Proc. Dorset Nat. Hist. Archaeol. Soc. 131, 113–126 (2010).

Mocho, P. et al. Turiasauria-like teeth from the upper jurassic of the Lusitanian Basin, Portugal. Hist. Biol. 28, 861–880 (2016).

Barco, J. L., Canudo, J. I. & Cuenca-Bescós, G. Descripción de Las vértebras cervicales de Galvesaurus herreroi Barco, Canudo, Cuenca-Bescós & Ruiz-Omeñaca, 2005 (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) Del tránsito Jurásico-Cretácico En Galve (Teruel, España). Revista Española De Paleontología. 21, 189–205 (2006).

Mateus, O., Mannion, P. D. & Upchurch, P. Zby atlanticus, a new turiasaurian sauropod (Dinosauria, Eusauropoda) from the late jurassic of Portugal. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 34, 618–634 (2014).

Sander, P. M. et al. Bone histology indicates insular dwarfism in a new late jurassic sauropod dinosaur. Nature 441, 739–741 (2006).

Campos-Soto, S. et al. Revisiting the age and palaeoenvironments of the upper Jurassic–Lower cretaceous? Dinosaur-bearing sedimentary record of Eastern spain: implications for Iberian palaeogeography. J. Iber. Geol. 45, 471–510 (2019).

Schwarz, D. Re–description of the sauropod dinosaur Amanzia (Ornithopsis/Cetiosauriscus) greppini n. gen. And other vertebrate remains from the Kimmeridgian (Late Jurassic) Reuchenette formation of Moutier, Switzerland.Schwarz et al. Swiss J. Geosci. 113, 2 (2020).

von Huene. Sichtung der grundlagen der jetzigen Kenntnis der sauropoden. Eclogae Geologica Helv. 20, 444–470 (1927).

Lapparent, A. F. & Zbyszewski, G. Les dinosauriens du Portugal. Memórias Dos Serviços Geológicos De Portugal. 2, 1–63 (1957).

Poropat, S. F. et al. A nearly complete skull of the sauropod dinosaur diamantinasaurus Matildae from the upper cretaceous Winton formation of Australia and implications for the early evolution of titanosaurs. R. Soc. Open. Sci. 10, 221618 (2023).

Bonaparte, J. F. & Mateus, O. A new diplodocid, Dinheirosaurus lourinhanensis gen. Et sp. nov., from the late jurassic beds of Portugal. Revista Del. Museo Argentino De Ciencias Naturales ‘Bernardino Rivadavia’ E Instituto Nac. De Investigación De Las Ciencias Naturales Paleontología. 5, 13–29 (1999).

Marpmann, J. S. et al. Cranial anatomy of the late jurassic Dwarf sauropod Europasaurus Holgeri (Dinosauria, Camarasauromorpha): ontogenetic changes and size dimorphism. J. Syst. Paleontol. 13, 221–263 (2015).

Han, F. L. et al. A new titanosaurian sauropod, Gandititan cavocaudatus gen. Et sp. nov., from the late cretaceous of Southern China. J. Syst. Paleontol. 22 (1), 2293038 (2024).

Woodruff, D. C., Curtice, B. D. & Foster, J. R. Seis-ing up the Super-Morrison Formation sauropods. J. Anat. 00, 1–17 (2024). (2023).

Foster, J. R. Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World, 2nd edn, 531 (Indiana University Press, 2020).

Holland, W. J. A new species of apatosaurus. Ann. Carnegie Mus. 10, 143–145 (1915).

Marsh, O. C. Notice of new jurassic dinosaurs. Am. J. Sci. (Ser. 3). 18, 501–505 (1879).

Peterson, O. A. & Gilmore, C. W. Elosaurus parvus: a new genus and species of the sauropoda. Ann. Carnegie Mus. 1, 490–499 (1902).

Van der Linden, T. T. P. et al. A new diplodocine sauropod from the Morrison Formation, Wyoming, USA. Palaeontologia Electroniaca. 27, a49 (2024).

D’Emic, M. D. & Carrano, M. T. Redescription of brachiosaurid sauropod dinosaur material from the upper jurassic Morrison Formation, Colorado, USA. Anat. Rec. 303, 24198 (2019).

Harris, J. D. & Dodson, P. A new diplodocoid sauropod dinosaur from the upper jurassic Morrison formation of Montana, USA. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 49, 197–210 (2004).

Salgado, L., Carvalho, I. S. & Garrido, A. C. Zapalasaurus bonapartei, a new sauropod dinosaur from La Amarga formation (Lower Cretaceous), Northwestern Patagonia, Neuquén Province, Argentina. Geobios 39, 695–707 (2006).

Whitlock, J. A. & Wilson Mantilla, J. A. The late jurassic sauropod dinosaur ‘Morosaurus’ agilis Marsh, 1889 reexamined and reinterpreted as a dicraeosaurid. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 40, e1780600 (2020).

Woodruff, D. What factors influence our reconstructions of Morrison formation sauropod diversity? Geol. Intermt. West. 6, 93–112 (2019).

Mannion, P. D., Tschopp, E. & Whitlock, J. A. Anatomy and systematics of the diplodocoid Amphicoelias altus supports high sauropod dinosaur diversity in the upper jurassic Morrison formation of the USA. R. Soc. Open. Sci. 8, 210377 (2021).

Rich, T. H. et al. A new sauropod dinosaur from Chubut Province, Argentina. Natl. Sci. Museum Monogr. 15, 61–84 (1999).

Moore, A. J. et al. Cranial anatomy of Bellusaurus Sui (Dinosauria: Eusauropoda) from the Middle-Late jurassic Shishugou formation of Northwest China and a review of sauropod cranial ontogeny. PeerJ 6, e4881 (2018).

Hone, D. W. E. et al. A small Asian brachiosaurid sauropod dinosaur from the late middle jurassic of China. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 29, 116A (2009).

Young, C. C. On a new sauropod from Yiping, Szechuan, China. Acta Paleontologica Sinica. 2, 355–369 (1954).

Fang, X. S. et al. Discovery of late jurassic Mamenchisaurus in Yunnan, Southwestern China. Geol. Bull. China. 23, 1006–1009 (2004).

Goloboff, P. A. et al. Improvements to resampling measures of group support. Cladistics 19, 324–332 (2003). (2003).

Goloboff, P. A. & Catalano, S. A. TNT version 1.5, including full implement. Phylogenetic Morphometrics Cladistics. 32, 221–238 (2016).

Acknowledgements

For their hospitality and access to the materials in their care, we thank Zhang Yuqing and other staff. Thoughtful reviews by anonymous reviewers and the editor who improved an earlier version of this manuscript. We gratefully acknowledge the Willi Hennig Society, which has sponsored the development and free distribution of TNT.

Funding

This research was supported by the grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant No. 42472020], and the China Geological Survey [Grant No. DD20230221, DD20250102605], the Youth Talent Programme of the Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences [JKYQN202320], and Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing [Grant No. cstc2021jcyj-msxmx1117].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.D., X.F.H., C.T., Q.Y.M, and G.B.W. designed the project. X.X.R., H.D., C.T., and H.L.Y. performed the research, X.X.R. H.D., and C.T. analysed the data, X.X.R. wrote the manuscript. H.D., X.F.H., C.T., X.X.R., Q.Y.M, G.B.W., and H.L.Y author reviewed drafts of the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dai, H., Hu, XF., Tan, C. et al. A new mamenchisaurid sauropod dinosaur from the upper jurassic of Southwest China reveals new evolutionary evidence from East Asian eusauropods. Sci Rep 15, 43308 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29995-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29995-z