Abstract

This study introduces a Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) framework for aerodynamic control of weakly compressible flow around an angled airfoil, aiming to optimize lift and drag through synthetic jet actuation. By combining pressure and velocity information from strategically placed sensors, the framework enhances the agent’s learning efficiency and control precision. Results demonstrate that integrating both variables improves total reward, reduces vortex shedding, stabilizes the wake, and minimizes lift fluctuations while lowering drag. The control policy, trained through 300 episodes using a Deep Q-Network (DQN) with five hidden layers of 128 neurons, achieves stable convergence and effective wake stabilization. Among the tested architectures, i.e. Traditional DQN, Double DQN, and Dueling DQN, the latter yields the most consistent learning behavior and highest performance by distinguishing state-value and advantage functions. Overall, the proposed DRL-based approach provides an efficient and robust strategy for active flow control in compressible aerodynamic applications, highlighting its potential for future engineering and aerospace systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Flow control—the ability to regulate fluid flow to achieve a desired state—offers substantial environmental and economic benefits. Industries such as shipping and air travel can significantly reduce fuel consumption and CO₂ emissions by minimizing drag while maintaining lift, translating into billions of dollars in savings annually1,2,3. Beyond aviation, flow control plays a crucial role in diverse applications, including microfluidics and combustion systems. Optimized engineering designs utilizing flow control are essential for addressing challenges such as structural vibrations, aeroacoustics and noise reduction, enhanced mixing, and thermal regulation4,5. Despite its wide applicability, achieving effective and scalable flow control has historically been constrained by methodological and computational limitations.

Traditionally, flow control strategies have prioritized drag reduction in bluff bodies, employing various methods such as open-loop techniques with passive or active devices and closed-loop control, explored both experimentally and numerically6,7. However, these approaches often relied on trial-and-error processes, resulting in substantial time and cost burdens. Additionally, computational limitations restricted their industrial applicability. While active control systems have demonstrated promise, the direct implementation of optimal control algorithms remained challenging due to the complexity of governing partial differential equations (PDEs)8,9,10. These limitations have spurred interest in alternative approaches, particularly data-driven methods that can circumvent the need for explicit modeling of governing equations.

Recent advances in high-performance computing have accelerated the adoption of data-driven and nonintrusive machine learning (ML) approaches within fluid dynamics11,12,13. Owing to their versatility, ML-based methods provide a powerful new framework for addressing diverse challenges in fluid mechanics, including inverse modeling14,15, flow forecasting16,17, geometric optimization18,19,20, turbulence closure model development21,22, and active control of flows23,24,25. Among these applications, active flow control in aerodynamic systems has emerged as a particularly challenging yet promising domain for machine learning-based innovation.

Active flow control in aerodynamic applications presents multiple challenges, including precise control, energy-efficient operation, optimized flow configurations, and enhanced aerodynamic performance indicators26,27. Among these challenges, the most significant and common issue is the time delay inherent in flow dynamics28. This delay occurs because fluid responses require a certain time to become evident, consequently limiting the controller’s capacity for timely and informed decision-making. Active aerodynamic control presents several complexities, including ensuring precise actuation, maintaining energy efficiency, and adapting to unsteady flow configurations. A key barrier to effective control is the intrinsic time delay in fluid response, which affects the timeliness of feedback-driven adjustments.

Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL), a class of machine learning algorithms that learns optimal strategies through environment interaction, has shown remarkable success in sequential decision-making tasks. Its ability to manage delayed feedback and adapt to nonlinear dynamics makes it particularly suitable for complex control systems like those in fluid dynamics29,30.

DRL introduces a transformative approach to control systems, enabling an agent to discover optimal strategies through interaction with its environment31. Unlike traditional methods dependent on prior system knowledge, DRL’s adaptability makes it highly flexible and versatile. One of DRL’s primary advantages is its capacity to manage complex, dynamic, and unfamiliar environments, thereby overcoming constraints associated with conventional methods that require comprehensive understanding of system dynamics32.

The intersection of active flow control, DRL, and computational fluid dynamics is an emerging area that addresses longstanding challenges in controlling complex fluid systems, particularly in aerodynamic applications involving compressible flows. Recent works demonstrate significant progress in using DRL for controlling flow around bluff bodies, reducing turbulence, and mitigating flow separation, especially in laminar and transitional regimes33. However, most of the literature focuses on incompressible or low-Reynolds-number flows, with limited studies systematically exploring DRL-driven control in compressible flow regimes, especially those involving high angle of attacks incorporating high-fidelity numerical analysis34.

The application of DRL in incompressible fluid dynamics has seen rapid growth. Foundational work by Elhawary (2020) demonstrated that DRL could effectively control vortex shedding around a circular cylinder using plasma actuators, revealing the potential for intelligent control in canonical setups33. Similarly, Font et al. (2025) expanded this approach to turbulent separation bubbles, showing that DRL could outperform periodic forcing in reducing separation regions35. Studies by Rabault and colleagues contributed significantly by integrating artificial neural networks (ANN) to detect and mitigate flow separation, primarily focusing on 2D stationary flows36. In parallel, Guastoni et al. (2021) and Paris & Duriez (2021) explored the role of deep learning in enhancing turbulence modeling and real-time control using reduced-order models, albeit in low-speed, incompressible regimes34,37.

More recent studies have pushed the boundary by coupling DRL directly with Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD)-in-the-loop frameworks, as seen in the work by Li & Tang (2023)38, but these still remain within laminar flow contexts. Wu et al. (2022) and Verma et al. (2024) explored aerodynamic optimization using DRL with surrogate environments, shifting focus toward static design improvements rather than dynamic control39,40. Meanwhile, Maulik et al. introduced physics-informed DRL to preserve physical consistency in control policies41,42. These advancements underscore the significant promise of DRL-CFD in aerodynamic active flow control, leveraging the accuracy and fidelity of CFD and detailed modeling capabilities. Although DRL-CFD is relatively underrepresented in current literature, its applications to active flow control show considerable promise42. However, across these studies, there’s a recurring limitation: the lack of rigorous, high-fidelity DRL applications to compressible, unsteady aerodynamic systems, particularly those involving moving airfoils and active jet control. This clearly highlights an underexplored yet promising area for advancing flow control in real-world aerospace applications. Building on recent DRL–CFD studies such as those by41,42,43, this research extends data-driven control into the domain of low-Mach-number compressible aerodynamics involving angled airfoils and synthetic jets. While prior work has demonstrated DRL-based control for incompressible or idealized setups, systematic evaluations that couple DRL architectures (DQN, Double DQN, Dueling DQN) with state-space and sensor-placement strategies in a compressible environment remain scarce. Hence, this study contributes by addressing this underexplored yet significant aspect of high-fidelity aerodynamic control.

It is acknowledged that the present freestream Mach number (Ma = 0.2) lies below the threshold of strong compressibility effects43,44. Nevertheless, a compressible solver is employed to retain density–pressure coupling and to account for possible local Mach number variations near the leading edge and wake of the angled airfoil, where the geometry and angle of attack may induce localized compressibility. A similar approach was also used Ref45. , which adopted a compressible formulation at Ma = 0.2 for analogous reasons.

To address the limitations of current flow control strategies in compressible regimes, this study introduces a novel DRL-based framework for active aerodynamic control around a high-angle-of-attack airfoil using synthetic jets. The objective is to enhance lift and reduce drag by learning optimal control policies directly from CFD simulations. Unlike prior studies focused on incompressible flows or simplified configurations, this work tackles the more challenging case of compressible laminar flow with unsteady vortex shedding. The innovation lies in coupling DRL with CFD for real-time decision-making, integrating synthetic jets as actuators, and systematically evaluating design elements such as sensor placement, state space formulation, and algorithm selection (DQN, Double DQN, and Dueling DQN). This contribution advances data-driven control in aerodynamic systems by systematically comparing DRL design choices, i.e. state representation, sensor placement, and algorithm architecture, within a low-Mach-number compressible framework. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: “Reinforcement learning” details the methodologies and learning algorithms employed in the control framework. “Flow control around airfoil” describes the physical model, numerical setup, and simulation parameters. “Results and discussion” presents the control performance and aerodynamic effects achieved through various DRL strategies, while “Limitations” provides a detailed discussion of the results and their implications.

Reinforcement learning

Reinforcement learning (RL) is an advanced area of machine learning characterized by its use of a feedback loop 47,48,49,50. The RL process begins with observations, referred to as states (st), collected from the environment at each time step. Based on these observations, the agent determines actions (at) intended to maximize a numerical reward (rt). These actions influence the environment, subsequently generating new observations (st+1) at the following step. The cycle repeats until a predefined termination condition, such as achieving environmental stability or reaching a specified duration, signals the end of an episode. By repeatedly training over numerous episodes, the agent refines its decision-making abilities, ultimately producing optimal sequences of states and actions (s0, a0, s1, a1, …).

Two primary approaches exist within RL: model-based and model-free strategies50. In the model-based method, agents develop an internal representation or model during training, capturing the relationship between actions and resulting states within the environment51. This internal model allows the agent to anticipate the outcomes of various actions before execution. Model-based algorithms have been extensively applied to areas such as kinetics and motion planning, addressing a variety of complex problems52. However, their main limitation is the dependence on highly accurate environmental models, which is particularly difficult for nonlinear systems. In contrast, model-free approaches do not require a predefined environmental model. Instead, these methods rely on experiential learning, where agents discover optimal actions through exploration and gradual transition toward exploitation based on accumulated knowledge53.

This research primarily addresses a two-dimensional laminar flow problem with unsteady vortex shedding, solved using the compressible Navier–Stokes equations under low-Mach-number. Specifically, the study explores a two-dimensional scenario governed by the conservation laws of mass, momentum, and energy. The CFD simulation is conducted with ANSYS FLUENT54. It is also worth mentioning that the model-free approach is selected, considering the complexity of the PDEs.

Deep Q network

Markov Decision Process (MDP) represents the interaction between the environment and agent. This formulation contains of a tuple signified as \(\:(S,A,T,r,\gamma\:)\), where \(\:A\) and \(\:S\) represent sets of actions and states, respectively. The transition function, denoted by \(\:T\left(s,a,{s}^{{\prime\:}}\right)\), compresses the probability \(\:P\left[{S}_{t+1}={s}^{{\prime\:}}\mid\:{S}_{t}=s,{A}_{t}=a\right]\) of transitioning from state \(\:s\) to state \(\:{s}^{{\prime\:}}\) given action \(\:a\). Additionally, the reward function, \(\:r(s,a)\), specifies the predictable reward \(\:\mathbb{E}\left[{R}_{t+1}\mid\:{S}_{t}=s,{A}_{t}=a\right]\). The discount factor, \(\:\gamma\:\), falls within the range \(\:\left[\text{0,1}\right]\), balancing immediate and future rewards.

In the framework of Markov Decision Processes, decisions are made sequentially, where each action impacts not only the immediate reward but also future states. Therefore, the agent’s objective is to maximize the discounted return \(\:{G}_{t}\), which represents the cumulative sum of rewards, each scaled by a discount factor over successive time steps.: \(\:{G}_{t}=\sum\:_{k=0}^{{\infty\:}}\:{\gamma\:}_{t}^{\left(k\right)}{R}_{t+k+1}\). Here, \(\:{\gamma\:}_{t}^{\left(k\right)}=\prod\:_{i=1}^{k}\:{\gamma\:}_{t+i}\) represents the discount factor applied over multiple time steps, emphasizing the agent’s pursuit of optimizing long-term rewards.

Q-learning is a robust and established algorithm that functions without needing prior knowledge of the system’s dynamics, thus classifying it as a model-free method55. Using Q-learning, an agent can approximate the expected discounted return—often called the value—by constructing an action-value function:

in which, \(\:{\mathbb{E}}_{\pi\:}\), signifies the average value gotten while the agent chooses an action based on the policy \(\:\pi\:\). As previously discussed, the central objective of RL is to identify a policy that maximizes cumulative rewards. Within this framework, at least one optimal policy exists, commonly represented as \(\:{\pi\:}^{\text{*}}\), superior all others by attaining the ideal action-value function. Therefore, the optimal action-value function \(\:{Q}^{\text{*}}\) can be definite as follows:

A widely used method for creating a new policy from the action-value function is the \epsilon -greedy strategy. In this approach, the agent selects the action that yields the highest estimated value (known as the greedy action) with probability 1−\(\:\:\epsilon\), and with probability \(\:\epsilon\), it selects a random action.

Q-learning runs with the direct objective of approximating the optimum action-value function, \(\:{Q}^{\text{*}}\), over an iterative learning procedure. In fact, the vital idea of Q-learning contains uninterruptedly refining the approximation by iteratively informing the action-value function, denoted as \(\:Q\):

By iteratively applying the Bellman equation (Eq. 3), the optimal action-value function, denoted as Qn, gradually converges to Q ∗ as n approaches infinity. A key advantage of this approach is that the learned action-value function Qn directly approximates Q ∗ , regardless of the specific policy being followed. Consequently, with continuous updates across all state-action pairs, the estimates eventually align with their true values.

However, in scenarios involving large state or action spaces, such as active flow control, computing Q-values for every possible state-action combination becomes computationally infeasible. To overcome this challenge, advanced techniques leverage deep neural networks to model agent attributes, including policies π(s, a) and action-value functions Q(s, a). These networks serve as nonlinear function approximators, trained using gradient descent to minimize a loss function and enhance accuracy.

A notable example of this approach is the Deep Q-Network (DQN) introduced by Mnih et al.56,57, which successfully integrates deep learning with RL. At each step, the agent selects an action based on the current state St and records a transition (St,+1,γt+1,St+1) in a replay memory buffer that stores past experiences. The neural network parameters are subsequently optimized using stochastic gradient descent, refining the model and improving the learning process over time.

DQN algorithm

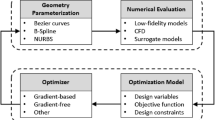

Figure 1 and Algorithm 1 illustrate the interaction between the DRL agent and the CFD solver, as well as the pseudo code for the DQN algorithm. This framework is composed of two key phases. In the first phase, the state St is defined by collecting data from the environment at time t. The agent then determines an action using the ε-greedy strategy, which directs the CFD solver in solving the governing flow equations (Eq. 1) and transitioning to the subsequent state St+1. This iterative cycle persists throughout the episode until a predefined termination condition is reached.

In the second phase, the acquired state St, along with the corresponding action at, reward rt, and next state St+1, is stored in a replay buffer. The agent periodically samples a set of transitions (mini-batches) from this buffer, computes the loss function, and updates the network parameters through optimization techniques. These two phases run simultaneously, forming the foundation of the DQN.

Flow control around airfoil

Physics of the flow

At a Reynolds number of 100 around an angled airfoil, the flow remains laminar, characterized by fluid particles moving smoothly and orderly along the airfoil’s surface. Nevertheless, under specific conditions, vortex shedding may occur, adding complexity to the aerodynamic characteristics. Vortex shedding refers to the periodic formation and detachment of vortices downstream of the airfoil, causing fluctuating aerodynamic forces such as lift and drag.

The occurrence of vortex shedding introduces transient flow behaviors, leading to variations in aerodynamic forces experienced by the airfoil over time. Importantly, the initiation and nature of vortex shedding depend mainly on the Reynolds number and are mostly unaffected by variations in Mach number, which, for this analysis, is consistently maintained at 0.2 at the inlet boundary. Consequently, even in compressible flows at low Mach numbers, laminar flow around the airfoil prevails, accompanied by additional transient effects resulting from vortex shedding.

Description of applied CFD

The CFD simulation of flow around the angled airfoil requires careful configuration to accurately capture fluid dynamics. An unstructured mesh composed of quadrilateral elements is utilized, incorporating a boundary layer mesh around the angled airfoil with an initial height of 3.6 × 10⁻⁶ m, providing sufficient grid resolution within the laminar boundary layer along the airfoil, as illustrated in Fig. 2.

To assess mesh independence, simulations were conducted using three mesh resolutions: a finer mesh (with all grid sizes halved), a baseline mesh (original configuration), and a coarser mesh (with all grid sizes doubled). The baseline grid used element sizes of \(\:{10}^{-5}\)m near the synthetic jet, \(\:5\times\:{10}^{-5}\)m adjacent to the airfoil and in the near wake region, \(\:2.5\times\:{10}^{-4}\)m in the far wake, and \(\:5\times\:{10}^{-3}\)m in the far-field region. Table 1 presents the lift and drag coefficients obtained for each case under active flow control. The results indicate that refining the mesh yields minimal variation, with errors of only 1.5% and 0.2% for the time-averaged lift and drag coefficients, respectively, compared to the baseline. However, coarsening the mesh leads to noticeable discrepancies, up to 7.3% in lift and 8.6% in drag, highlighting the importance of maintaining adequate resolution.

The chord length of the airfoil is 1.5 cm, with inlet boundary conditions set to achieve Reynolds and Mach numbers of 100 and 0.2, respectively, as detailed in Table 2. The inlet boundary, \(\:{{\Gamma\:}}_{in}\) in Fig. 5, is set to pressure farfield boundary condition with the specified Mach number and inlet temperature values from Table 2 with zero gauge pressure. The outlet boundary, \(\:{{\Gamma\:}}_{out}\) in Fig. 5, is treated as a pressure outlet where the static pressure is prescribed as zero gauge pressure, which corresponds to a Dirichlet condition on pressure while applying zero-gradient (Neumann) conditions for all velocity components. The angled airfoil surface employs a no-slip condition with specified surface roughness.

To verify time-step independence, simulations were conducted using two different time-step values: \(\:5\times\:{10}^{-6}\) and \(\:{10}^{-5}sec\), for both off-control and on-control configurations. Table 3 summarizes the time-averaged lift and drag coefficients along with their relative percentage errors. For the off-control case, the differences in lift and drag coefficients were negligible, with a maximum error of only 0.03%. Similarly, under the on-control condition, the maximum deviation observed was 0.4% in lift and 1.7% in drag coefficient. These minimal discrepancies confirm that the simulation results are insensitive to the time-step size within this range, and thus, the value of \(\:5\times\:{10}^{-6}\:sec\) has been chosen.

Moreover, flow variable convergence criteria are established at \(\:{10}^{-4}\) for each time step. The ideal gas law governs density calculations across the computational domain. Initial conditions include zero relative pressure and velocity components, with the temperature set to 3.35 °C.

To validate the accuracy of the numerical model, steady-state simulations were performed at various angles of attacks (AoAs), and the resulting aerodynamic coefficients were compared with benchmark data from the literature. Figure 3a presents the variation of the lift coefficient with AoA, while Fig. 3b shows the corresponding drag coefficient profiles. The reference data include results reported by Siddiqi and Lee58, Loftin and Poteat59, and Hoffmann et al.60. The current numerical predictions show good agreement with the literature, particularly in capturing the trends and magnitudes of the lift and drag coefficient across the AoA range. While slight underpredictions in lift are observed near the stall region and moderate overpredictions in drag appear at higher angles, the overall consistency confirms the reliability of the simulation setup.

Figure 4 presents a comparison of the lift-to-drag ratio as a function of the angle of attack between the current simulation and the laminar compressible results of Morizawa et al.45 for a NACA 0012 airfoil at Ma = 0.2. The two datasets exhibit strong agreement across the entire range of AoA, confirming that the present solver accurately captures the aerodynamic trends in laminar, weakly compressible flow. This additional validation complements the higher-Reynolds-number benchmarks and ensures the robustness of the numerical model in the regime relevant to the current study.

Controller setup

In this section, the variations and parameters integrated into the DQN controller is fully considered and explained. The impinging jet position is positioned in hole near leading edge of airfoil, as illustrated in Fig. 5.

Comparison of the lift-to-drag ratio obtained from the present numerical simulations (solid black line) with that of Ref45 (blue curve).

To evaluate the controller’s effectiveness, we systematically analysed its performance under different conditions. This involved a detailed assessment of how varying the target network size influences its efficiency. Additionally, we investigated the impact of the learning duration (episode number) on controller performance to determine its optimal configuration. Furthermore, we adjusted the episode length, representing the duration of each learning iteration, to examine its effect on the controller’s behaviour.

A key component of our study focused on the role of state monitoring in shaping controller performance. Specifically, we analysed the effect of including both velocity and pressure values in the state representation, compared to using only velocity values. Lastly, we performed a comparative evaluation of soft and hard implementations of double and Dueling DQN to gain insights into their respective performances.

The DRL-based controller interacts with the CFD solver through a closed-loop process that links actuation, flow response, and feedback. The control action in this study is defined as the synthetic jet velocity magnitude \(\:{U}_{a}\), which is adjusted by the agent during run. The actuator is modeled as a single synthetic jet orifice located near the leading edge of the airfoil (\(\:x/c=0.1\)) on the suction side, as illustrated in Fig. 5. The jet diameter is 0.2 mm, and the jet velocity is constrained between 0 and 20 m/s.

Since the DQN algorithm requires a discrete action space, the continuous velocity range is represented by a set of integer-valued actuation levels, i,e, \(\:{U}_{a}\in\:\{0,\:1,\:2,\:3,\:\dots\:,\:\:20\}\hspace{0.17em}m/s\), where each value corresponds to one output node of the DQN. The selected action index is then mapped directly to the associated jet-velocity magnitude. This discretization enables the controller to modulate momentum injection into the boundary layer while remaining compatible with the DQN architecture. This configuration allows the controller to inject momentum periodically into the boundary layer to delay flow separation and mitigate vortex shedding.

The state observations provided to the agent consist of both velocity and pressure measurements collected from various virtual sensors distributed around the airfoil and within the wake region (as shown in Fig. 6). These sensors capture transient flow features such as pressure fluctuations and vortex strength, providing the agent with the necessary information to infer aerodynamic behavior. Each control decision corresponds to one physical actuation period equal to the vortex shedding time scale determined from the baseline flow. After the agent selects an action, the CFD solver advances one actuation period, computes the updated flow field, and returns the resulting aerodynamic coefficients. The reward function is computed as a weighted combination of the mean lift enhancement and drag reduction within that interval, allowing the controller to iteratively optimize aerodynamic performance.

Results and discussion

DRL specifications

As previously discussed, the agent’s behavior is directed by a reward function specifically optimized for aerodynamic control. This function has been formulated similarly to existing studies in the literature on incompressible flow around an airfoil.

.

The aerodynamic forces, mainly the lift and drag coefficients, are averaged through each action step. To ensure the reward remains positive, two constants, R₁ and R₂, are adjusted. These constants, both positive, help balance the influence of lift relative to drag. Following recommendations from61, R₁ is assigned a value of 3, and R₂ is set to 0.2.

The training procedure comprises 300 episodes, each spanning 25 vortex shedding periods to provide sufficient exposure to varying flow conditions for the agent to converge on an effective control strategy.

State properties

Choosing the right state is crucial for guiding an agent’s decision-making, especially when tackling complex problems. A well-designed state should accurately capture the system’s dynamics, enhancing the agent’s ability to make predictions.

The placement of states plays a key role in in enabling effective DRL-based control systems. Previous research on flow dynamics around an airfoil has explored various state configurations61,62. These studies indicate that a layout similar to the one shown in Fig. 6, where states are distributed around the airfoil and in the wake region, leads to the most effective controller design.

To evaluate the impact of spatial information on controller performance, three state placement configurations are considered (illustrated in Fig. 6):

-

Foil States: Sensors located near the airfoil surface.

-

Wake States: Sensors positioned downstream of the airfoil in the wake region.

-

Full States: A combination of both Foil and Wake States, providing a comprehensive spatial representation.

The results (Fig. 7) from the evaluation of different state placements show distinct trends in their effectiveness in optimizing RL-based flow control strategies. The figure shows the cumulative reward curves presents the total reward obtained over 300 episodes for each of these state configurations. The Full States configuration, which includes both near-airfoil and wake region states, achieves the highest total reward and exhibits the most stable performance improvement over episodes. This suggests that combining information from both the foil and wake regions provides a more comprehensive representation of the flow dynamics, leading to better decision-making by the controller.

The Wake States configuration, which consists of states positioned downstream of the airfoil, also demonstrates a positive trend in total reward but remains slightly lower than the Full States setup. This indicates that while downstream flow characteristics are crucial for control, relying solely on wake information may not be sufficient to capture all relevant dynamics.

On the other hand, the Foil States arrangement, which focuses on states positioned near the airfoil, exhibits the highest variability in performance and the lowest overall reward. This suggests that while local flow conditions around the airfoil are important, they do not provide enough information about the downstream effects, which are crucial for effective control strategies.

Overall, the results highlight the importance of using a diverse and well-distributed state placement strategy. The Full States configuration, by incorporating both near-airfoil and wake states, ensures a more holistic representation of the flow, ultimately leading to superior control performance.

Traditionally, in incompressible flows, velocity is prioritized as the primary variable of interest39,61. However, our study focuses on compressible flow control, where both velocity and pressure are critical in shaping the system’s behavior. We evaluate three state vector formulations to determine the relative importance of velocity and pressure:

-

Velocity States: including only velocity components.

-

Pressure States: including only pressure values.

-

Pressure & Velocity States: combining both variables into the state representation.

Figure 8 illustrates the impact of different state representations on the performance of the reinforcement learning-based control strategy. The Pressure & Velocity States configuration consistently achieves the highest total reward, indicating that incorporating both flow variables provides the most comprehensive understanding of the flow dynamics. This combination enables the agent to capture critical interactions between velocity and pressure variations, leading to more effective control decisions.

The Velocity States configuration, which focuses solely on velocity variations, follows closely behind in terms of performance. Given that velocity is often prioritized in incompressible flows, its importance in compressible flow control remains significant. However, the slight underperformance compared to the combined state configuration suggests that ignoring pressure variations may lead to a loss of valuable information, particularly in cases where compressibility effects play a key role in the system’s response.

On the other hand, the Pressure States configuration exhibits the lowest total reward and the highest fluctuations throughout the training episodes. This suggests that while pressure is a crucial variable in compressible flows, relying solely on pressure states may lead to an incomplete representation of the environment. The increased variability in rewards indicates that pressure fluctuations alone might not provide a stable learning signal, making it more challenging for the agent to optimize its control strategy effectively.

Overall, these results highlight the advantages of using a combined state representation that includes both pressure and velocity information. This approach enables the controller to achieve a more detailed and stable understanding of the flow, ultimately leading to superior performance in RL-based flow control.

To assess the consistency and robustness of the learning algorithm, we conducted three independent training runs of the DRL controller. Figure 9 presents the episode-wise mean of the total reward along with a shaded region representing the standard deviation. The results show a consistent increase in total reward across episodes with limited variance among the three independent runs, suggesting that the DRL training process exhibits indicative stability under the chosen hyperparameters. However, given the small number of repetitions (N = 3), these results should be considered qualitative rather than statistically conclusive.

In the first stage of this research, we aim to assess the efficacy of DRL in improving the aerodynamic stability of compressible flow around an angled airfoil. The comparison of temporal variations in the time-averaged drag and lift coefficients on the angled airfoil is depicted in Fig. 10. These coefficients are defined as follows:

where \(\:\langle F{\rangle }_{ac}\) is the force on the angled airfoil during the fixed jet velocity. Figure 10 compares the lift and drag coefficients over time for an angled airfoil with and without control, utilizing a classic DQN-based RL strategy. The “on-control” scenario represents the application of the learned control strategy, while “Off Control” denotes the baseline case without active control.

In the drag coefficient plot, the on control case demonstrates a noticeable reduction in drag fluctuations compared to the off-control scenario. The average drag coefficient \(\:{\stackrel{-}{C}}_{d}\) for the on-control case is 0.058, which is lower than the off-control case’s \(\:{\stackrel{-}{C}}_{d}\)=0.079. The maximum drag coefficient is also reduced from 0.132 (off-control) to 0.1055 (on-control), indicating that the control mechanism effectively minimizes excessive drag spikes. Additionally, the on-control case maintains a more stable and consistent drag response, suggesting improved aerodynamic efficiency.

In the lift coefficient plot, the control strategy enhances lift performance. The on-control case maintains a higher mean lift coefficient (\(\:{\stackrel{-}{C}}_{l}\)=1.997) than the off-control case (\(\:{\stackrel{-}{C}}_{l}\)=1.795). The fluctuations in lift are also more constrained in the on-control case, with a smaller range between minimum and maximum values. The off-control case exhibits greater instability, with the lift coefficient frequently dropping below 1.5, whereas the on-control case stabilizes around 2.0, enhancing aerodynamic performance.

Overall, the application of the DQN-based control strategy significantly improves aerodynamic efficiency by reducing drag and increasing lift. The on-control airfoil maintains a more stable and optimal aerodynamic state, which is particularly beneficial for applications requiring sustained lift and minimal drag, such as in aircraft wing design or energy-efficient aerodynamic surfaces. These findings highlight the effectiveness of RL in flow control optimization.

The effects of active flow control on the wake structure and vortex formation behind an angled airfoil are evident in the velocity contour plots (Fig. 11). Without control, strong vortex shedding is observed, leading to increased drag and unsteady aerodynamic forces. The off-control case exhibits a typical Kármán vortex street, with large alternating vortices contributing to flow instability and energy loss. In contrast, the application of active flow control significantly suppresses vortex shedding, leading to a more structured and streamlined wake. This reduction in flow separation results in lower drag, improved lift stability, and enhanced aerodynamic efficiency. By keeping the boundary layer attached for longer, the control mechanism mitigates lift fluctuations and minimizes unsteady aerodynamic loads. Overall, active flow control proves to be an effective strategy for optimizing airfoil performance by reducing drag and stabilizing lift, highlighting its potential benefits in aerodynamics and flow management.

Figure 12 presents the impact of different learning durations—150, 300, and 500 episodes—on the evolution of the total reward for the classic DQN. All three cases initially show noticeable fluctuations as the agent explores the environment and gradually improves its policy. The 150-episode case (blue curve) exhibits early learning progress but quickly saturates at a relatively low reward level, clearly indicating that this duration is insufficient for achieving satisfactory control performance. Extending the training to 300 episodes (brown curve) leads to a substantial improvement, with markedly higher final rewards and a much more stable learning trajectory. Increasing the number of episodes further to 500 (green curve) produces only a minor additional gain in total reward. While the 500-episode run achieves the highest overall performance, the improvement over the 300-episode case is marginal when compared to the significant extra computational cost required due to the CFD-in-the-loop setup. These results demonstrate that 300 episodes provide an effective balance, delivering strong policy convergence without the heavy computational penalty associated with longer training durations.

Figure 13 presents the total reward evolution across training episodes for three different DQN architectures: Traditional DQN, Double DQN, and Dueling DQN, applied to aerodynamic control in compressible flow around an angled airfoil. The Traditional DQN shows a steady improvement in total reward, though it exhibits some fluctuations throughout the training process. The Double DQN, which aims to reduce overestimation bias in Q-value estimation, demonstrates a more fluctuating learning curve, with overall lower stability and reward accumulation compared to the other methods. This suggests that, while Double DQN can mitigate Q-value overestimation, it may not provide the best policy refinement in this specific aerodynamic control problem.

In contrast, the Dueling DQN (dashed blue line) achieves the highest total reward and exhibits the most stable improvement over episodes. The dueling architecture, which separates state-value and advantage functions, enables better decision-making by distinguishing between valuable and non-valuable state-action pairs. This results in faster convergence and superior overall performance in aerodynamic control. The findings suggest that while Traditional DQN provides a reliable baseline, and Double DQN improves value estimation, Dueling DQN offers the most effective learning approach for optimizing flow control by ensuring smoother and more consistent reward accumulation.

Limitations

While this study demonstrates the potential of DRL for active flow control in compressible aerodynamic environments, several limitations should be acknowledged:

-

1.

Simplified geometry and jet modeling: The use of a fixed-position synthetic jet with a simplified actuation model does not capture the full complexity of real actuator dynamics. In practical applications, physical constraints, actuator delays, and jet–structure interactions could affect control performance.

-

2.

Limited generalization of the DRL policy: The trained DRL agent is optimized for a specific flow condition (Re = 100, Mach = 0.2). While effective under these settings, its generalization to different Reynolds numbers, Mach regimes, or geometric configurations remains untested.

-

3.

Computational cost and training time: Despite using a relatively compact neural network architecture, the training process remains computationally expensive due to the high-fidelity CFD solver and the need for repeated environment interactions. This can hinder scalability or real-time adaptation.

-

4.

Absence of real-time feedback validation: The control strategy has not been validated in real-time or experimental environments. Sensor noise, time delays, and hardware limitations may influence the performance of the DRL-based controller when transitioning from simulation to deployment.

Additionally, it should be noted that the present study focuses on a low-Reynolds-number (Re = 100) and low-Mach-number (Ma = 0.2) laminar flow regime. While this configuration provides a controlled environment for evaluating DRL behavior and flow control performance, the results cannot be directly generalized to turbulent or strongly compressible aerodynamic conditions. The extension of the proposed DRL-CFD framework to higher Reynolds and Mach numbers, where nonlinear turbulent interactions and shock-related effects become significant, remains an important direction for future research.

Future work will also focus on addressing these limitations by extending the model to three-dimensional flows, incorporating realistic actuator constraints, evaluating policy transferability across flow conditions, and exploring hardware-in-the-loop validation frameworks.

Conclusion

The presented data highlights the effectiveness of DRL in optimizing aerodynamic control for compressible flow around an angled airfoil. Through comparative analysis of different state representations, it was observed that incorporating both pressure and velocity states led to the highest total reward, indicating a more comprehensive understanding of flow dynamics. Additionally, state placement strategies demonstrated that combining information from the foil and wake regions resulted in better policy learning and improved control performance. These findings emphasize the importance of choosing the right state variables and their placement to enhance RL efficiency in aerodynamic applications. While the global Mach number corresponds to a quasi-incompressible regime, solving the full compressible Navier–Stokes equations allows the capture of local compressibility effects that may arise around the airfoil geometry and ensures compatibility with future studies at higher Mach numbers. The primary novelty of this work therefore lies in the systematic assessment of DRL framework configurations under low-Mach-number aerodynamic conditions.

A more detailed examination of the training duration revealed that extending the number of episodes from 150 to 300 led to a substantial enhancement in policy performance, with noticeably higher accumulated rewards and markedly more stable learning behavior. However, increasing the training duration further from 300 to 500 episodes resulted in only marginal additional improvement, despite imposing a significant computational burden due to the expensive CFD-in-the-loop framework. Therefore, 300 training episodes represent an effective trade-off, providing strong policy convergence while avoiding the prohibitive computational cost associated with much longer training durations.

Furthermore, a comparative evaluation of DRL architectures shows that Dueling DQN consistently outperforms Traditional and Double DQN variants. Its ability to distinguish state-value and advantage functions enables faster convergence and more robust control policies. These findings underscore the advantage of advanced DRL frameworks in flow control applications.

Our work addresses a critical gap in the existing literature, where most DRL-based flow control efforts focus on incompressible or idealized configurations. Unlike those studies, this paper demonstrates a data-driven control strategy for compressible laminar flow with vortex shedding, a regime relevant to low-speed aerodynamic applications but often neglected in DRL research.

While the training runs demonstrated consistent convergence behavior, the stability assessment is based on a limited number of independent simulations. Future work will expand this analysis to a larger set of runs to provide statistically robust confirmation of training stability and variance.

The novelty of our approach lies in three key aspects:

-

1.

the application of DRL to compressible flow control using synthetic jets,

-

2.

a comprehensive evaluation of state design and sensor placement, and.

-

3.

a systematic comparison of classic, double, and Dueling DQN architectures, with Dueling DQN yielding superior performance.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Corbett, J.J. & Koehler, H. W. Updated emissions from ocean shipping. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 108(D20) (2003).

Martins, J. R. R. A. Aerodynamic design optimization: Challenges and perspectives. Comput. Fluids 239, 105391 (2022).

Safari, A., Saidi, M. H., Salavatidezfouli, S. & Yao, S. Numerical investigation of the drag reduction effect in turbulent channel flow by superhydrophobic grooved surfaces. Flow 3, E27 (2023).

Dengqing, C. et al. Advances in dynamics and vibration control of large-scale flexible spacecraft. Chinese Journal of Theoretical and Applied Mechanics 51(1), 1–13 (2019).

Balaji, P. S. & SelvaKumar, K. K. Applications of nonlinearity in passive vibration control: a review. Journal of Vibration Engineering & Technologies 9, 183–213 (2021).

Ma, R., Bi, K. & Hao, H. Inerter-based structural vibration control: A state-of-the-art review. Eng. Struct. 243, 112655 (2021).

Mat, M. N. H. et al. Optimizing dry ice blasting nozzle divergent length using cfd for noise reduction. CFD Lett. 11(6), 18–26 (2019).

Li, A., Chen, J., Liu, Y., Bolton, J. S. & Davies, P. Noise source identification and noise directivity analysis of bladeless fans by combined cfd and caa method. In Fluids Engineering Division Summer Meeting. Vol. 83716. V001T01A014. (American Society of Mechanical Engineers, 2020).

Yan, S., Li, C., Xia, Y. & Li, G. Analysis and prediction of nature gas noise in a metering station based on cfd. Eng. Fail. Anal. 108, 104296 (2020).

Shi, D., Gan, W.-S., Lam, B., Hasegawa, R. & Kajikawa, Y. Feedforward multichannel virtual-sensing active control of noise through an aperture: Analysis on causality and sensor-actuator constraints. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 147(1), 32–48 (2020).

Taira, K. et al. Modal analysis of fluid flows: Applications and outlook. AIAA J. 58(3), 998–1022 (2020).

Gerdroodbary, M.B., Shiryanpoor, I., Salavatidezfouli, S., Abazari, A M & Pascoa, J. C. Optimizing aerodynamic stability in compressible flow around a vibrating cylinder with deep reinforcement learning. Phys. Fluids 36(12) (2024).

Salavatidezfouli, S., Zadeh, S. M., Stabile, G. & Rozza, G. Deep reinforcement learning for the heat transfer control of pulsating impinging jets. Advances in Computational Science and Engineering 1, 401–423 (2023).

Zhou, H. et al. Design methods and strategies for forward and inverse problems of turbine blades based on machine learning. J. Therm. Sci. 31, 82–95 (2022).

Ivagnes, A., Demo, N. & Rozza, G. Towards a machine learning pipeline in reduced order modelling for inverse problems: neural networks for boundary parametrization, dimensionality reduction and solution manifold approximation. J. Sci. Comput. 95(1), 23 (2023).

Barzegar Gerdroodbary, M. & Salavatidezfouli, S. A predictive surrogate model based on linear and nonlinear solution manifold reduction in cardiovascular FSI: A comparative study. Comput. Biol. Med. 189, 109959 (2025).

Barzegar Gerdroodbary, Mostafa, and Sajad Salavatidezfouli. "A predictive surrogate model of blood haemodynamics for patient-specific carotid artery stenosis." Journal of the Royal Society Interface 22, no. 224 (2025): 20240774.

Rabault, J., Ren, F., Zhang, W., Tang, H. & Xu, H. Deep reinforcement learning in fluid mechanics: A promising method for both active flow control and shape optimization. J. Hydrodyn. 32, 234–246 (2020).

Li, J., Zhang, M., Martins, J.R.R.A. & Shu, C. Efficient aerodynamic shape optimization with deep-learning-based geometric filtering. AIAA J. 58(10), 4243–4259 (2020).

Viquerat, J. et al. Direct shape optimization through deep reinforcement learning. J. Comput. Phys. 428, 110080 (2021).

Pawar, S., San, O., Rasheed, A. & Vedula, P. A priori analysis on deep learning of subgrid-scale parameterizations for kraichnan turbulence. Theoret. Comput. Fluid Dyn. 34, 429–455 (2020).

Beck, A. & Kurz, M. A perspective on machine learning methods in turbulence modeling. GAMM-Mitteilungen 44(1), e202100002 (2021).

Ren, F., Hu, H. & Tang, H. Active flow control using machine learning: A brief review. J. Hydrodyn. 32, 247–253 (2020).

Li, Y., Chang, J., Kong, C. & Bao, W. Recent progress of machine learning in flow modeling and active flow control. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 35(4), 14–44 (2022).

Castellanos, R., Cornejo Maceda, G.Y. , De La Fuente, I. & Noack, B.R., Ianiro, A. & Discetti, S. Machine-learning flow control with few sensor feedback and measurement noise. Phys. Fluids 34(4) (2022).

Kuprat, J., van der Broeck, C.H., Andresen, M., Kalker, S., Liserre, M. & De Doncker, R.W. Research on active thermal control: Actual status and future trends. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 9(6), 6494–6506 (2021).

Phan, T.-L., Pham, Q.T., Loan Nguyen, T. K. & Nguyen, T. T.. A numerical analysis of active flow control techniques for aerodynamic drag reduction in the square-back ahmed model. Appl. Sci. 13(1), 239 (2022).

Tian, Z. Networked control system time-delay compensation based on pi-based dynamic matrix control. At-Automatisierungstechnik 69(1), 41–51 (2021).

Ramstedt, S. & Pal, C. Real-time reinforcement learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 32 (2019).

Zou, Z., Xinran, Yu. & Ergan, S. Towards optimal control of air handling units using deep reinforcement learning and recurrent neural network. Build. Environ. 168, 106535 (2020).

Wang, Y.-Z. et al. Performance analysis of reinforcement learning algorithms on intelligent closed-loop control on fluid flow and convective heat transfer. Phys. Fluids 35(7) (2023).

Mondal, A.K. & Jamali, N. A survey of reinforcement learning techniques: strategies, recent development, and future directions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2001.06921, 2020.

Elhawary, M. Deep reinforcement learning for active flow control around a circular cylinder using unsteady-mode plasma actuators. arXiv preprint arXiv:2012.10165, 2020.

Paris, J. & Duriez, T. Efficient deep reinforcement learning for real-time flow control using reduced-order models. J. Fluid Mech. 918, A31 (2021).

Font, B., Alcántara-Ávila, F., Rabault, J. & Vinuesa, R. Deep reinforcement learning for active flow control in a turbulent separation bubble. Nat. Commun. (2025).

Rabault, J., Kuchta, M., Jensen, A., Réglade, U. & Cerardi, N. Artificial neural networks for the detection and control of separated flows. Phys. Fluids 31(9), 094105 (2019).

Guastoni, L., Önstedt, E. & Azizpour, H. & Vinuesa, R. Convolutional-networks-based wall modeling in large-eddy simulations of turbulent flows. Phys. Rev. Fluids 6(5) (2021).

Li, W. & Tang, H. Adaptive flow control using deep reinforcement learning with CFD-in-the-loop. Comput. Fluids 245, 105700 (2023).

Jingwei, Wu., Kun, Xu. & Ying, Yu. Data-driven aerodynamic optimization using deep reinforcement learning. AIAA J. 60(2), 551–565 (2022).

Verma, S., Balu, A. & Papadakis, M. Deep reinforcement learning with surrogate environments for aerodynamic shape control. J. Comput. Phys. 487, 112143 (2024).

Maulik, R., San, O., Rasheed, A. & Vedula, P. Physics-informed deep reinforcement learning for unsteady flows. Comput. Mech. 67, 251–266 (2021).

Li, R., Zhang, Y. & Chen, H. Learning the aerodynamic design of supercritical airfoils through deep reinforcement learning. AIAA J. 59(10), 3988–4001 (2021).

Cavazzuti, M., Corticelli, M. A. & Karayiannis, T. G. Compressible Fanno flows in micro-channels: An enhanced quasi-2D numerical model for laminar flows. Thermal Science and Engineering Progress 10, 10–26 (2019).

Venerus, D. C. & Bugajsky, D. J. Compressible laminar flow in a channel. Phys. Fluids 22, 046101 (2010).

Morizawa, S., Nonomura, T., Oyama, A., Fujii, K. & Obayashi, S. . Effect of Mach number on airfoil characteristics at Reynolds number of 3,000. Trans. Jpn. Soc. Aeronaut. Sp. Sci. 61(6), 258–26 (2018).

Vinuesa, R., Lehmkuhl, O., Lozano-Durán, A. & Rabault, J. Flow control in wings and discovery of novel approaches via deep reinforcement learning. Fluids 7(2), 62 (2022).

Guéniat, F., Mathelin, L. & Yousuff Hussaini, M. A statistical learning strategy for closed-loop control of fluid flows. Theor. Comput. Fluid Dyn. 30, 497–510 (2016).

Novati, G. et al. Synchronised swimming of two fish. arXiv preprint arXiv:1610.04248 (2016).

Verma, S., Novati, G. & Koumoutsakos, P. Efficient collective swimming by harnessing vortices through deep reinforcement learning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 115(23), 5849–5854 (2018).

Doll, B.B., Simon, D.A. & Daw, N. D.. The ubiquity of model-based reinforcement learning. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 22(6), 1075–1081 (2012).

Kaiser, L. et al. Model-based reinforcement learning for atari. arXiv preprint arXiv:1903.00374 (2019).

Polydoros, A.S. & Nalpantidis, L. Survey of model-based reinforcement learning: Applications on robotics. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 86(2), 153–173 (2017).

Çalışır, S. & Kurt Pehlivanoğlu, M. Model-free reinforcement learning algorithms: A survey. In 2019 27th Signal Processing and Communications Applications Conference (SIU). 1–4. (IEEE, 2019).

ANSYS FLUENT. Fluent v23 R1 User’s Guide (2023).

Jang, B., Kim, M., Harerimana, G. & Kim, J.W.. Q-learning algorithms: A comprehensive classification and applications. IEEE Access 7, 133653–133667 (2019).

Mnih, V. et al. Playing Atari with deep reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1312.5602 (2013).

Mnih, V. et al. Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature 518(7540), 529–533 (2015).

Siddiqi, Z. & Lee, J.W. A computational fluid dynamics investigation of subsonic wing designs for unmanned aerial vehicle application. In Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part G: Journal of Aerospace Engineering. Vol. 233(15). 5543–5552 (2019).

Loftin Jr, L. K. & Irene Poteat, M. Aerodynamic characteristics of several NACA airfoil sections at seven Reynolds numbers from 0.7 × 10⁶ to 9.0 × 10⁶. In Technical Report (1948).

Hoffmann, M.J., Reuss Ramsay, R. & Gregorek, G.M. Effects of grit roughness and pitch oscillations on the NACA 4415 airfoil. In Technical Report, National Renewable Energy Laboratory (1996).

Niroobakhsh, Z., Emamy, N., Mousavi, R., Kummer, F. & Oberlack, M. Numerical investigation of laminar vortex shedding applying a discontinuous galerkin finite element method. Progress in Computational Fluid Dynamics, an International Journal 17(3), 131–140 (2017).

Rabault, J. & Kuhnle, A. 18 deep reinforcement learning applied to active flow control (2022).

Funding

This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2503).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.G.H. and R.K. performed simulations and investigations, L.M. and V.A.M. developed software and N.S.S.S. and H.R. wrote manuscript and K.H: and W.A. supervised the projects. All authors reviewed the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

A. Appendices

A. Appendices

A1. DRL agent architecture and training hyperparameters

The control policy is based on a DQN architecture implemented as a fully connected multilayer perceptron (MLP). The Q-network consists of five hidden layers, each with 128 neurons, followed by ReLU activation functions. A dropout layer with a dropout rate of 0.1 is applied after each hidden layer to improve generalization and reduce overfitting. The output layer returns the estimated Q-value for each discrete action available to the actuator.

The agent is trained using an off-policy DQN scheme with experience replay and a periodically updated target network. The exploration policy is ε-greedy. The fluid solver provides the environment state at each timestep, and the agent selects an actuation command for the synthetic jet. Table 4 summarizes all hyperparameters required to reproduce the training process.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hammouda, N.G., Khan, R., Mostafa, L. et al. Application of deep reinforcement learning for aerodynamic control around an angled airfoil via synthetic jet. Sci Rep 16, 528 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29997-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29997-x