Abstract

To meet ambitious carbon neutrality targets, the transition to renewable energy has amplified demand for grid-scale storage, with pumped storage hydropower emerging as the dominant solution due to its technical maturity and economic viability. However, the embodied carbon emissions of pumped storage hydropower infrastructure construction remain critically underexplored. This study presents a systematic assessment of embodied carbon emissions from China’s pumped storage hydropower development from 2000 to 2020, employing an environmentally extended input-output model combined with decomposition analysis. The results show that the cumulative emissions rose from 2.38 million tons (Mt) in 2000 to 23.83 Mt in 2020, with significant spatial variation. Anhui and Zhejiang had the largest embodied carbon emissions, while Henan and Inner Mongolia had the largest embodied carbon emission per unit of GDP. By employing the Logarithmic Mean Divisia Index (LMDI) decomposition model, five key driving factors of these emissions were identified: carbon emission intensity, investment efficiency, energy conversion efficiency, capacity generation efficiency, and economic scale. LMDI decomposition reveals that economic scale, investment efficiency, and energy conversion efficiency were the dominant drivers of emission growth, whereas carbon intensity of inputs and capacity generation efficiency exerted significant offsetting effects. These findings emphasize the need for continuous technical innovation, promotion of a circular economy, tailored regional policies, and efficient cost management to mitigate embodied carbon emissions from pumped storage hydropower projects, thereby promoting sustainable energy transitions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the rapid urbanization and industrialization, China has emerged as the world’s largest energy consumer1. This surge in energy demand has led to significant environmental challenges, notably the increase in greenhouse gas emissions. In response to global climate change, China announced ambitious targets in 2020, aiming to peak carbon emissions by 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 20602. Energy transition towards clean and renewable energies is crucial to meeting these targets. However, most renewable energy sources are inherently unstable and intermittent due to their reliance on natural conditions3. To address this issue, numerous countries, including the United States, European Union, China, and India, have invested heavily in energy storage systems4. For example, China plans to install over 30 GW of energy storage capacity by 2025, while India aims for 51 to 84 GW by 2031–20324. Similarly, eight U.S. states have targeted a combined 20.5 GW of energy storage capacity by 2030–20355. The European Association for Storage of Energy estimates that the EU will require at least an additional 127 GW of energy storage power by 20306. These developments underscore the critical role of energy storage systems in future energy transitions.

Among various energy storage technologies, pumped storage hydropower (PSH) stands out as the most economical large-scale option globally7. In 2021, the global installed capacity of pumped storage hydropower was approximately 160 GW, and the International Energy Agency (IEA) predicts that it will account for 30% of global hydropower capacities by 20308. China has made the largest investment in pumped storage hydropower around the world, which now accounts for 89.3% of the domestic energy storage system4,9,10. Nearly a hundred pumped storage hydropower projects have been approved for construction in China, primarily in the eastern, southern, and northwestern regions, encompassing provinces such as Zhejiang, Hubei, and Guangdong11. By the end of 2020, the total installed capacities of pumped storage hydropower in China had exceeded 30 GW12. According to the National Energy Administration’s medium and long-term development plan (2021–2035), installed capacities are projected to surpass 60 GW by 2025 and reach 120 GW by 203013,14. Pumped storage hydropower projects typically comprise upper and lower reservoirs3. Water serves as the storage medium, enabling the conversion of electrical energy into potential energy during off-peak periods when water is pumped into the upper reservoir. During peak demand, the water is released to the lower reservoir to generate electricity, converting potential energy back into electrical energy. Pumped storage hydropower fulfills multiple functions, including peak load shifting, frequency regulation, energy storage, emergency backup, and multi-benefit reservoir usage3,7,8,9. The construction of a typical pumped storage project spans 8–10 years, with an operational lifespan of over 50 years7,15.

Although pumped storage hydropower is usually regarded as a low-carbon technology during the operation phase, the construction stage is highly resource-intensive and generates significant upstream emissions through energy- and carbon-intensive supply chains, such as cement, steel, and electromechanical equipment. For example, these projects are extremely material-intensive, with typical installations demanding approximately 2.8 to 3.5 million metric tons of concrete and 50,000 to 70,000 metric tons of steel per gigawatt of installed capacity. The production processes of these materials are major emission sources that are often overlooked in conventional environmental assessments. Additionally, long-distance transportation of heavy components such as turbines and transformers further exacerbate carbon footprints during construction. Furthermore, geochemical interactions at reservoir sites introduce additional variability in carbon emissions. These embodied carbon emissions are different in nature from direct emissions, which mainly arise from on-site fuel use or reservoir processes. Embodied carbon emissions instead account for the carbon released along multi-tier supply chains before the facility becomes operational. Clarifying this distinction is essential, because overlooking embodied carbon emissions may underestimate the near-term climate burden of large-scale infrastructure expansion and lead to incomplete evaluations of technology choices, siting, and material procurement. Throughout this paper, the term “embodied carbon emissions” refers specifically to supply-chain emissions associated with the construction phase, covering materials, equipment, and services from cradle to gate. Direct emissions during construction and operation are outside the scope of this accounting. Our baseline follows the production perspective. Hence, in order to address these issues, it is imperative to conduct a nationwide investigation of embodied carbon emissions generated by pumped storage hydropower projects construction while systematically exploring the influencing factors, thereby establishing a comprehensive understanding of the carbon footprint throughout the construction lifecycle of such renewable energy infrastructure.

Some previous studies have accounted such carbon emissions of hydropower by using different methods16,17. Gilfillan and Pittock 20223 analyzed the potential environmental impacts of pumped storage hydropower projects in 24 Pacific Rim economies by establishing a comprehensive framework, presuming a high prospect of pumped storage. Ge et al. (2020)18 evaluated the effect of constructing pumped storage power in underground coal mines on reducing carbon emissions by using structural path analysis model. Some studies also calculated the carbon emissions through life cycle assessment (LCA). For instance, Wang et al. (2019)19 calculated the large-scale water footprint and carbon footprint of 50 representative hydropower stations in China, considering all life cycle stages. Li et al. (2017)16 used Input-Output LCA to analyze the carbon footprint of 5 large hydropower projects in China. Such life cycle assessment is commonly used to evaluate emissions on project level, such as specific projects evaluation and comparison between different projects20. Nevertheless, the existing studies in this field still have some limitations. Firstly, most studies focused on the carbon emission of conventional hydropower projects, with a lack of analysis on pumped storage hydropower projects21. Secondly, studies on pumped storage hydropower mainly considered the carbon emission of some specific projects, without considering a holistic picture at regional or national level22. Against this background, a national-scale assessment of construction-phase embodied carbon emissions in pumped storage hydropower is particularly timely for China. Such an assessment enables comparison across projects and provinces, reveals abatement opportunities in upstream sectors such as cement or steel, and highlights how large investment programs may create short-term “carbon debt” even in the process of expanding clean energy infrastructure. These insights are directly relevant to China’s dual-carbon goals and to policy instruments such as provincial carbon targets, the national emissions trading scheme, and green procurement standards.

In addition, to systematically investigate the influencing factors of carbon emissions, decomposition analysis has become a widely adopted method for quantifying individual contributions. Among various decomposition approaches, the Logarithmic Mean Divisia Index (LMDI) method is particularly favored due to its unique advantages, such as residual-free decomposition, strong applicability, ease of implementation, and clear interpretability23. This technique has been extensively applied to analyze carbon emissions and energy consumption patterns across multiple sectors. For instance, Chong et al. (2023)24 employs Energy Allocation Analysis and LMDI decomposition to systematically examine the technical drivers (including energy conversion efficiency, end-use structure, and power generation mix) behind China’s coal consumption changes from 2005 to 2020. He et al. (2022)23 analyzed the influential factors driving carbon emissions from China’s electricity industry at both national and provincial levels, utilizing a combination of LMDI decomposition and K-means clustering to identify targeted emission reduction strategies for different regions. However, existing studies show a critical research gap in applying LMDI decomposition to electricity infrastructure construction. Specifically, the factor decomposition of embodied carbon emissions from pumped storage hydropower projects construction remains understudied. While environmentally extended input–output (EEIO) analysis provides a complete view of supply-chain emissions, very few studies have combined EEIO with decomposition methods to understand the drivers of embodied carbon emissions in infrastructure construction. Here we integrate EEIO with the LMDI, which allows us to attribute changes in embodied carbon emissions to interpretable factors such as carbon intensity, investment efficiency, energy conversion efficiency, and economic scale.

This study differs from previous hydropower-related embodied carbon research in three respects. First, unlike project-level LCAs focusing on single dams, we provide a comprehensive national-scale inventory of pumped storage hydropower construction embodied emissions across two decades. Second, while earlier IO-based studies described general infrastructure, we specifically target pumped storage hydropower as a critical flexibility asset, reflecting China’s rapid build-out. Third, instead of a descriptive review, we critically identify the research gap that national pumped storage hydropower construction has not been systematically quantified despite its policy importance under the dual-carbon strategy. This study covers all 76 pumped storage hydropower projects (27 in operation and 49 approved for construction) in the country. The study period spans from 2000 to 2020, and nine input sectors are considered. Spatial distributions are considered by setting up a bottom-up inventory list at the provincial level so that region-specific mitigation solutions can be found. Influential factors such as investment cost, carbon emission intensity, energy efficiency, and economic scale are also decomposed to obtain valuable insights on carbon reduction. Some feasible policy recommendations are proposed to mitigate embodied carbon emission from the construction of such pumped storage hydropower projects. This study significantly advances the understanding of carbon emissions from pumped-storage hydropower projects, filling crucial gaps in existing literature. It also provides practical guidance for policymakers and project developers to formulate more effective carbon reduction strategies. This is of great significance for promoting the sustainable development of pumped storage hydropower as a clean energy source and achieving global climate goals. The whole paper is organized as follows: after this introduction, the section “Method and data sources” provides a detailed explanation of the methods and data, the section “Results” presents the research results, and the section “Discussion” proposes discussions and policy recommendations

Method and data sources

Embodied carbon emission calculation

Input-output model displays the domestic and foreign economic interdependencies between sectors and regions, which describes the whole supply chains by linking the consumption and production perspectives. For Environmentally Extended Input-Output model (EEIO), it replaces the economic interdependencies by environmental influences such as carbon emissions, so that the embodied emissions between different input sectors can be determined25. Such an input-output method has been successfully applied in many studies to estimate the embodied carbon emissions generated by infrastructure construction, especially for those energy projects26,27,28,29. Relative to earlier EEIO-based infrastructure analyses16,18, this study offers three methodological advances. (i) Nine-sector disaggregation of pumped storage hydropower construction inputs aligned with Chinese budget categories, which avoids aggregation bias where high- and low-intensity inputs are mixed. In this study, an exhaustive input inventory list for pumped storage hydropower infrastructure construction was compiled. According to the Chinese industrial classification standard, we attributed an enormous amount of inputs into different 9 sectors which are “construction auxiliary engineering”, “construction engineering”, “environmental protection and soil and water conservation project”, “electrical and mechanical equipment and installation works”, “metal structure equipment and installation”, “compensation for land acquisition and resettlement”, “independent fee”, “reserved budget” and “interest incurred during construction”30. Detailed information can be found in the supplementary material Table S1. For clarity, we summarize that the nine pumped storage hydropower construction input categories were each mapped to their closest EXIOBASE counterparts, including construction-related sectors (e.g., civil works, auxiliary works), equipment manufacturing (e.g., electromechanical machinery, fabricated metal products), and service-related items (e.g., financial intermediation for interest during construction). (ii) Consistent data harmonization: project expenditures are converted to constant prices and mapped one-to-one to EXIOBASE China sectors, ensuring comparability across provinces and years. (iii) Integration with residual-free LMDI, enabling a transparent decomposition of drivers from investment intensity to economic scale.

Based on the conventional input-output framework, the EEIO table developed in this study captures the monetary transactions among various economic sectors, thus reflecting the relationships between goods production and associated environmental impacts. We constructed the extended input-output table specific to pumped storage hydropower infrastructure construction using data from the EXIOBASE database and the China Electric Power Yearbooks. The fundamental balance of the input-output table is given by:

where X represents the total outputs matrix, A represents the technical coefficient matrix whose element ai, j represents the direct input from Sector i to Sector j, AX defines the intermediate demands of economic activities, Y represents the final demands matrix. By incorporating the identity matrix I, the equation can be rearranged to solve for X.

To calculate the embodied carbon emissions, we introduced direct carbon emission intensities derived from EXIOBASE31,32. The direct carbon emission intensity for sector i, denoted as \(\:{e}_{i}\), is computed as:

where \(\:{E}_{i}\) represents the direct emissions from economic sector i, and \(\:{X}_{i}\) represents the total outputs of sector i.

The embodied carbon emission intensities are obtained through:

Here, L is the matrix of embodied carbon emission intensities, and E is the row vector of direct carbon emissions per sector. The China block of EXIOBASE is derived from the full global Multi-Regional Input–Output (MRIO) table, so sectoral intensities already incorporate both domestic production and international trade linkages; imports are thus endogenously reflected and not assumed to be domestic.

With the embodied emission intensities calculated and the classified inputs data, the embodied carbon emissions of each pumped storage hydropower project generated by infrastructure construction (CTL, t) can be calculated by:

where Xi, t (CNY/KW) is the monetary costs of sector i in year t in one project and Li, t (ton CO2/CNY) is the corresponding embodied carbon intensity of that sector.

The embodied carbon emission per kilowatt of each pumped storage hydropower project can be calculated as:

where CTL, x,t is the total embodied carbon emissions of pumped storage hydropower project x, Pk, x is the total installed capacity hydropower project x.

The embodied carbon emission per economic unit in each region can be calculated as:

where the ETL, j,t is the total embodied carbon emissions of pumped storage hydropower infrastructure in province j in year t, Gj, t is the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of different provinces in year t.

LMDI decomposition model

The Logarithmic Mean Divisia Index (LMDI) methodology, an extension of the Index Decomposition Analysis (IDA) framework, has gained prominence in energy-system studies and has since been extended to carbon emission analysis. Unlike traditional approaches such as the Laspeyres index or other decomposition techniques, the LMDI model exhibits distinct advantages in multi-factor disaggregation through systematic indicator construction. This complete decomposition eliminates residual terms, thereby ensuring greater analytical rigor and enhanced generalizability of findings—features critical for robust policy-relevant insights in sustainability research. In this study, we decompose the embodied carbon emissions induced by pumped storage hydropower construction into five influencing factors as Eq. (7):

where \(\:{C}_{j}\) represents the embodied carbon emissions in province j; \(\:{IT}_{j}\) represents the total investment costs of pumped storage hydropower projects in province j; \(\:{PC}_{j}\) represents the total power generation capacities of pumped storage hydropower projects in province j; \(\:{IC}_{j}\) represents the total installed capacities of pumped storage hydropower projects in province j; \(\:{G}_{j}\) represents the GDP in province j.

The five influencing factors of embodied carbon emissions are as follows: \(\:{CT}_{j}\) is the embodied carbon emissions per investment unit, defines the carbon emission intensity; \(\:{IP}_{j}\) is the investment cost per unit of electricity generated, serves as an indicator of investment efficiency; \(\:{PI}_{j}\) is the electricity generation per installed capacity, evaluates energy conversion efficiency; \(\:{IG}_{j}\) is the installed capacity supported per unit GDP, represents the capacity generation efficiency; \(\:{G}_{j}\) defines the economic scale.

Based on the LMDI model, the embodied carbon emissions change from the base year 0 to year t (\(\:{\varDelta\:C}_{TL}\)) can be decompsed into the effects of these five influencing factors:

where \(\:{\varDelta\:C}_{CT}\), \(\:{\varDelta\:C}_{IP}\), \(\:{\varDelta\:C}_{PI}\),\(\:\:{\varDelta\:C}_{IG}\), \(\:{\varDelta\:C}_{G}\) represent the contribution of the factors of carbon emission intensity effect, investment efficiency effect, energy conversion efficiency effect, capacity generation efficiency effect and the economic output effect. In Eq. (9), the notation \(\:{ln}\left(a,b\right)\) denotes the logarithmic mean. Here, a represents the value of each factor in Eq. (8) in the target year (t), and b represents the corresponding value in the base year (0).

Uncertainty analysis

Embodied carbon estimates for large-scale infrastructure are inevitably affected by uncertainties in data sources and parameter settings. For the present study, two sources of uncertainty are most relevant: (i) the project-level input inventories that are mapped to EXIOBASE sectors, (ii) the sectoral direct carbon emission intensities derived from EXIOBASE. To evaluate the robustness of our results, we conducted an uncertainty analysis based on Monte Carlo simulation.

The simulation was repeated 10,000 times to approximate the distribution of outcomes under parameter uncertainty. Following established practice, we specified the distributions as follows: input inventories and emission intensities were modeled as lognormal distributions to ensure non-negative values. The coefficient of variation (CV) was used as a standardized measure of uncertainty. For emission intensities, in the absence of EXIOBASE-specific CVs, we used 15% as a representative value, reflecting averages reported for OECD (≈ 10%) and non-OECD countries (≈ 20%)35,36. For the input inventories derived from IO tables, we applied a CV of 10%, consistent with prior studies of infrastructure-related IO analysis30. Because this study employs a global MRIO framework, provincial variation in input inventories and sectoral carbon intensities is not explicitly represented. We also performed an additional sensitivity test to mimic the range of variation observed in Chinese provincial statistics.

The results showed that while absolute embodied emission levels shift accordingly, the temporal trends and relative provincial patterns remain stable. The Monte Carlo analysis indicates that uncertainty in embodied emissions is relatively modest compared with the overall magnitudes reported: the 95% confidence interval of total embodied emissions lies within ± 12% of the mean estimate. Detailed results of this uncertainty analysis are illustrated in Figure S1 and S2 of the supplementary material, indicating that the uncertainties of these parameters have marginal impacts on the main findings of this study. Hence, these exercises confirm that the conclusions of this study are not sensitive to reasonable parameter variations or regional differences in emission intensities.

Data sources

In this study, the data of input-output table and direct carbon emission intensity were downloaded from EXIOBASE33,34. 200 commodities and 163 industries are involved in the EXIOBASE, and we matched them to the input sectors of pumped storage hydropower infrastructure construction standard in China as shown in Table S1. According to the industrial enterprise database and China Electric Power Yearbook, basic information about investment cost, installed capacity and power generation of all pumped storage hydropower projects was collected35, detailed information can be found in Table S2-S6. In addition, Google Earth was used to locate these projects, which are presented in a map generated by QGIS. Provincial GDP data was abstracted from the China Statistical Yearbook36.

Consent to participate

All the authors agree to participate in this study.

Results

Overview: cumulative embodied carbon emissions from 2000 to 2020

China’s pumped storage hydropower infrastructure construction began in the 1990s37. In 2000, the cumulative embodied carbon emissions from China’s pumped storage hydropower were 2.38 Mt. By 2020, this figure had increased dramatically to 23.83 Mt. The primary contributor to these emissions was the “construction engineering” sector, which involves the use of numerous carbon-intensive materials such as steel. This upward trend can be largely attributed to substantial investments in hydropower infrastructure construction. Since the turn of the 21 st century, the Chinese government has gradually accelerated the pace of energy transition, with hydropower becoming increasingly crucial. Consequently, numerous pumped storage hydropower projects have been constructed to bolster the development of energy storage systems. The emission structure of pumped storage hydropower infrastructure has evolved significantly from 2000 to 2020.

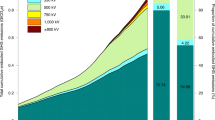

Figure 1 illustrates that in 2000, only medium scale (50 MW-300 MW) and large (1) scale projects (1200 MW-3000 MW) were constructed. Large (1) scale projects accounted for over 95% of the total embodied carbon emissions, while medium-scale projects contributed only a modest 5%. From 2001 to 2005, due to limited demand for energy storage, only medium scale pumped storage hydropower projects were undertaken, and the cumulative embodied carbon emissions rose from 0.1 Mt to 0.52 Mt. Meanwhile, the cumulative embodied carbon emissions of large (1) scale projects remained steady at 2.3 Mt. Since 2006, however, with the construction of conventional hydropower infrastructure and a growing demand for energy storage that could not be met by medium-scale projects alone, large (2) scale projects (300 MW-1200 MW) were introduced. This resulted in a surge in cumulative embodied carbon emissions, which increased from 0.19 Mt to 4.97 Mt. By the end of 2020, large (1) scale projects possessed the largest installed capacities and accounted for 75% of all projects. Accordingly, these projects also had the highest share (75%) of cumulative embodied carbon emissions, followed by large (2) scale projects (23%) and medium-scale projects (2%). The temporal profile also reflects policy- and market-driven construction cycles. In 2001–2005, subdued demand for storage coincided with small annual additions; after 2006, the step-up in large-unit deployment aligned with broader power-infrastructure expansion; and during 2010–2015 incremental growth moderated. A renewed acceleration after 2015 tracks the new wave of pumped storage hydropower construction and approvals.

China’s embodied carbon emission intensities across different sectors have exhibited a declining trend over the past two decades, thanks to technological advancements (Fig. 2). Notably, the construction engineering sector reported the highest embodied carbon emission intensities, ranging from 1.5 to 18 times higher than those of other sectors. From 2000 to 2020, these intensities in the construction engineering sector dropped markedly by 74%. Similarly, the embodied carbon emission intensities in the “water resource management,” “electrical machinery manufacturing,” and “banking, securities, and other financial activities” sectors also decreased by 35%, 74%, and 86%, respectively. These observable declines constitute the empirical basis for technological advancements. They are consistent with project-owner practices documented over the study period-tighter construction budgeting and process control, optimization of logistics that reduces unnecessary material movement, progressive equipment upgrades in electromechanical works, and the gradual substitution of lower-intensity inputs within sectoral supply chains-together lowering embodied intensities without altering system boundaries.

Spatial distributions of embodied carbon emissions

As demonstrated in Fig. 3a, China has constructed 27 pumped storage hydropower projects over the past two decades. These projects are predominantly located in the eastern region, attributable to geographical and economic advantages. Currently, these projects span 16 provinces across China. Anhui stands out as the province with the highest number of projects, contributing 2.86 million tons (Mt) of embodied carbon emissions from 2000 to 2020, accounting for 16% of the national total. Zhejiang follows closely, with its three projects generating the highest total embodied carbon emissions of 4.39 Mt, equivalent to 18% of the national total. Guangdong, Henan, Hubei, and Jiangsu have also constructed multiple projects, resulting in emissions of 3.73 Mt, 1.13 Mt, 0.72 Mt, and 2.17 Mt, respectively. Conversely, Jilin has the lowest share of embodied carbon emissions, accounting for only 0.8%. Regarding the construction of these projects across national power grids, the Central China Grid and the South China Grid are the leading contributors. Notably, no projects have been constructed in the Northwest China Grid or the Southwest China Grid to date. Figure 3b reveals a distinct spatial distribution pattern for embodied carbon emissions per economic unit (GDP) compared to total embodied carbon emissions. Hainan tops the list with the highest embodied carbon emissions per unit of GDP, at 13.53 tons per Chinese yuan (CNY). Inner Mongolia (7.12 tons per CNY) and Shanxi (7.13 tons per CNY) also exhibit high emissions per unit of GDP, primarily due to economic underdevelopment despite relatively low cumulative emissions. In contrast, Jiangsu, despite having higher total emissions, records a lower emissions rate of 2.11 tons per CNY per unit of GDP. Shandong and Hunan have the lowest emissions per unit of GDP, at 1.43 tons per CNY and 1.45 tons per CNY, respectively.

Furthermore, the scale of pumped storage hydropower projects significantly influences embodied carbon emissions per installed capacity, as illustrated in Fig. 4. Economies of scale dictate that larger projects generate lower emissions per installed capacity. For instance, in the East China Grid, which hosts projects of various scales, Large (2) scale projects exhibit the lowest embodied carbon emissions per installed capacity (0.75 tons/KW), whereas medium-scale projects have the highest (1.25 tons/KW). A similar trend is observed in the North China Grid and the Northeast China Grid, where Large (2) scale projects also demonstrate the lowest emissions per installed capacity. Therefore, investing in Large (2) scale projects in these regions is more environmentally friendly and can help mitigate additional embodied carbon emissions. In the Central China Grid, where no Large (2) scale projects have been constructed, Large (1) scale projects still offer lower emissions per installed capacity (0.63 tons/KW) compared to medium-scale projects (1.58 tons/KW).

These differences suggest that beyond project count and size, structural factors also influence the carbon intensity of construction. Provinces such as Hunan, Anhui, and Zhejiang combine intensive pumped storage hydropower deployment with strong industrial bases in cement, steel, and electromechanical sectors, which amplify construction-related carbon emissions. In addition, many eastern load centers import bulk materials from other regions, raising indirect embodied carbon emissions. Finally, spatial clustering also reflects system functions: provinces like Zhejiang and Guangdong serve as load centers within the West-East electricity transfer framework, where pumped storage hydropower is crucial for peak shaving and renewable integration.

Embodied carbon emissions (a) and Embodied carbon emissions per economic unit (b) of pumped storage hydropower projects. (This figure was drawn by QGIS-OSGeo4W-3.32.0, URL: https://download.osgeo.org/qgis/win64/).

Contributions of the influencing factors

Given that China’s pumped storage hydropower infrastructure development aligns with the Five-Year Plan (FYP) and the nation’s evolving carbon management policies, this study temporally decomposes the driving factors into four phases: 2000–2005 (Stage I), 2006–2010 (Stage II), 2011–2015 (Stage III), and 2016–2020 (Stage IV). As shown in Fig. 5, the decomposition results of embodied carbon emissions from pumped storage hydropower projects construction reveal that three positive influencing factors collectively increased embodied carbon emissions by 16.03 Mt during 2000–2020: economic output effect (dominant at 79.86%), investment efficiency effect (11.34%), and energy conversion efficiency effect (9.01%). Conversely, carbon emission intensity effect (4.37 Mt) and capacity generation efficiency effect (4.95 Mt) jointly offset 9.32 Mt of emissions. The stage-wise analysis demonstrates distinct patterns. Stage I (2000–2005) exhibited continuous emission growth, driven by all factors except capacity generation efficiency effect (1.25 Mt offset), reflecting the 10th FYP’s economic-priority strategy with substantial infrastructure investments but limited low-carbon technology deployment. Both Stage III (2011–2015) and Stage IV (2016–2020), corresponding to intensive pumped storage hydropower projects construction periods, showed significant emission surges, though partially mitigated by technological innovations (carbon emission intensity effect) and scale economies (capacity efficiency effect). Stage II (2006–2010) uniquely recorded a 1.73 Mt emission decrease from Stage I, primarily attributable to the energy conversion efficiency effect becoming an offsetting factor, due to enhanced grid integration technologies and operational optimizations during the 11th FYP period.

Taking the entire study period as the analytical timeframe, we conducted a provincial-level decomposition analysis of the driving factors of the embodied carbon emissions from pumped storage hydropower projects in six provinces: Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Anhui, Henan, Hubei, and Guangdong, each of which constructed more than one pumped storage hydropower project during this period (Fig. 6). The results reveal that the economic output effect emerged as the most significant contributor to emission increases across all provinces, driving up embodied carbon emissions by 7.91 Mt in Zhejiang, 1.61 Mt in Jiangsu, 2.11 Mt in Anhui, 2.63 Mt in Henan, 0.79 Mt in Hubei, and 1.87 Mt in Guangdong, respectively. Notably, the specific mechanisms through which these factors interacted varied substantially across provinces. Guangdong Province exhibited a pattern mirroring the national profile, where the carbon emission intensity effect and capacity generation efficiency effect jointly offset 4.70 Mt of embodied carbon emissions, while other factors exerted positive driving effects. Zhejiang, Jiangsu, and Hubei demonstrated similar offsetting dynamics, with the carbon emission intensity effect and energy conversion efficiency effect collectively counteracting 5.93 Mt, 0.61 Mt, and 1.01 Mt of emissions, respectively. Anhui Province achieved emission reductions through a dual mechanism: the carbon emission intensity effect and investment efficiency effect jointly offset 0.83 Mt of emissions. Henan Province presented a unique case, where only the investment efficiency effect contributed to a 0.28 Mt emission offset, suggesting province-specific technological adoption pathways and policy responsiveness.

Discussion

Future embodied carbon emissions projection

By 2021, a total of 49 pumped storage hydropower projects in China had been approved for construction, signifying a substantial potential for future embodied carbon emissions (Fig. 7). Notably, the majority of these projects are situated in the eastern region, with a few located in the west. Collectively, these future projects will span across 21 provinces in China. The Northeast China Grid (with 11 projects) and the East China Grid (with 13 projects) lead in the number of approved pumped storage hydropower projects, primarily due to their technological advancements and geographical advantages. Additionally, four projects are scheduled for construction in the Northwest China Grid, and two in the Southwest China Grid. Given the current insufficiency of cost data for these western regions, this study employs national average data to project future trends. It is worth noting that no medium-scale pumped storage hydropower projects were approved for construction, with Large (1) scale projects accounting for over 80% of the total. Only nine Large (2) projects were approved. Consequently, reducing the embodied carbon emissions from Large (1) scale projects will be crucial in the future.

The construction of these approved pumped storage hydropower projects is expected to generate approximately 53.45 million tons (Mt) of additional embodied carbon emissions, more than double the emissions from currently operating projects. Among the provinces, Zhejiang, Hebei, Shandong, and Fujian will rank at the top in terms of embodied carbon emissions, with estimates of 8.15 Mt, 6.95 Mt, 5.30 Mt, and 5 Mt, respectively. In contrast, Ningxia, Jiangxi, and Inner Mongolia will contribute minimally, accounting for only 1% of the total emissions. The predictions in this study are based on current embodied carbon intensities and construction cost data to estimate the future embodied carbon emissions of the approved projects. However, with efficient cost management and new technological breakthroughs, the actual embodied carbon emissions in the future may be slightly lower than predicted. Therefore, this study should be viewed as an exploratory estimation of future trends rather than a precise projection. The aim of this prediction is to provide a comprehensive overview of future pumped storage hydropower projects and their embodied carbon emissions, enabling the formulation of feasible mitigation policies.

Embodied carbon emissions and spatial distributions of both constructed and approved projects. (This figure was drawn by QGIS-OSGeo4W-3.32.0, URL: https://download.osgeo.org/qgis/win64/).

Comparison with other energy technologies

In this section, we undertake a comparative analysis of our results with those of other energy technologies, specifically conventional hydropower and wind turbines. All these projects were constructed in China within a similar timeframe, facilitating a meaningful comparison of their embodied carbon emissions. Table 1 presents the comparison results alongside other pertinent data. For hydropower projects (including pumped storage), all results in Table 1 are derived from the same EEIO framework, with consistent sectoral carbon intensities and construction-phase boundaries, ensuring direct comparability. In contrast, most published estimates for wind power are based on life cycle assessment. To enable comparison, we extracted only the construction-stage embodied emissions from such studies. We note that this cannot guarantee complete consistency of system boundaries with the EEIO results, but it provides the best available benchmark given the scarcity of construction-focused studies. Although pumped storage is functionally a storage technology, its construction process is dominated by large-scale hydro infrastructure and civil engineering works. For this reason, it is more appropriate to compare its embodied emissions with other electricity infrastructure projects rather than with battery or thermal storage systems, whose manufacturing-based processes are not technically comparable. The findings reveal that pumped storage hydropower project construction yields the lowest embodied carbon emissions among the technologies considered, amounting to merely 0.71 tons per kilowatt (tons/KW). In contrast, conventional hydropower station manufacturing exhibits the highest embodied carbon emission of 2.53 tons/KW, as reported by Ge et al. (2023)30. Hence, the construction of additional pumped storage hydropower stations is poised to be more environmentally benign compared to conventional hydropower in the forthcoming years. Furthermore, although wind turbines represent another clean energy technology, the carbon emissions incurred during their construction (0.98 tons/KW) are marginally higher than those of pumped storage hydropower38. Solar technology and coal power are excluded from this comparison, as studies pertinent to these technologies have calculated carbon emissions per kilowatt-hour rather than per installed capacity, rendering direct comparison challenging. To enhance the accuracy of our results, this study established comprehensive inventories that encompass the entire construction phase of each pumped storage hydropower project in China. We considered both the physical and financial aspects of each project, leveraging the typically existing single project financial plan for construction. This holistic approach ensures that our findings are more precise and reflective of real-world conditions.

Policy implications for future carbon emission reduction

Although pumped storage hydropower is recognized as a crucial energy storage system, its construction has significantly contributed to embodied carbon emissions. To address this issue and promote sustainable development, several policy recommendations are proposed.

First, continuous technological progress is indispensable. Our decomposition shows that reductions in sectoral carbon intensities helped offset part of the emission increase, especially in provinces where cleaner production processes were adopted. Strengthening low-carbon cement and steel technologies, optimizing construction logistics, and encouraging substitution with greener materials will further reduce intensities39. Such improvements are especially critical in the “Construction engineering,” “Independent fee,” and “Electromechanical equipment and installation” sectors, which dominate the embodied carbon footprint.

Second, promoting circular economy practices can generate additional mitigation. Recycling of steel and other bulk materials reduces reliance on carbon-intensive primary production, while refurbishment and remanufacturing extend infrastructure lifetimes. For instance, critical minerals essential for renewable energy infrastructure, including hydropower and wind turbines, can achieve resource savings of up to 30% through recycling40,41. Considering that the approved projects may add 53.45 Mt of embodied emissions, even modest gains in recycling or efficiency improvements could translate into sizeable reductions. For example, our results on scale effects indicate that shifting from medium-scale to large projects can reduce unit intensities by 0.50–0.95 tons/KW depending on the grid, which implies measurable reductions when applied to future capacity additions. This involves various activities throughout the construction process, including eco-design, cleaner production, end-of-life management, repair, refurbishment, and remanufacturing. Given that current pumped storage hydropower projects have a lifespan of 50–100 years; responsible management of end-of-life products will be crucial.

Third, policies should address trade-offs between project scale, location, and embodied emissions in the context of the East–West electricity transfer strategy. Large projects consistently achieve lower unit intensities, but provincial decomposition shows that the drivers of emission change vary: in Guangdong, mitigation mainly arose from improvements in carbon intensity and capacity efficiency, while in Zhejiang and Jiangsu, energy conversion efficiency was more prominent. Incorporating embodied-carbon criteria into siting and sizing decisions can thus help align system flexibility with emission reduction, ensuring that eastern demand is met without disproportionately raising construction-phase emissions.

Finally, potential rebound effects deserve careful attention. The LMDI analysis revealed that economic scale expansion was the dominant driver of emission growth, accounting for nearly 80% of the increase. If lower unit intensities are used to justify accelerated project approvals, overall embodied emissions could still rise rapidly. To guard against this, policymakers should complement supply-side decarbonization with demand-side governance, such as setting embodied-carbon budgets for new construction consistent with Five-Year Plans and the dual-carbon targets. Currently, the prices of such materials in China only reflect their economic value, excluding ecological costs. By internalizing these externalities through resource/energy taxes and carbon emission trading tools, construction costs can be managed more rationally.

Broader implications for storage choices and carbon neutrality

This study’s findings also carry broader implications for debates on energy storage portfolios and carbon-neutrality pathways. Pumped storage hydropower provides multi-hour to long-duration flexibility with synchronous stability support, while electrochemical batteries are optimized for short-duration balancing. Our construction-phase embodied carbon inventory therefore complements battery-focused evidence, showing that upstream carbon loads differ substantially across technologies.

From a policy perspective, this implies that storage portfolio design should not rely solely on levelized cost or performance metrics, but also consider embodied emissions as an explicit decision attribute. In carbon-neutral pathways, pumped storage hydropower can serve as a pivotal option for low-carbon long-duration flexibility, while batteries provide fast-response balancing; sequencing and regional siting strategies can minimize total embodied emissions while ensuring reliability.

By making construction-phase embodied emissions transparent, our results can be incorporated into carbon-aware capacity expansion models and procurement frameworks. This creates an analytical bridge from project-level emission inventories to system-level planning, thereby strengthening the evidence base for least-regret decarbonization strategies.

Conclusion

Pumped storage hydropower is one kind of clean energy and plays an important role in the energy transition. Nevertheless, the construction of such projects also generated enormous embodied carbon emissions. This study calculated the embodied carbon emissions induced by the pumped storage hydropower projects construction in China from 2000 to 2020. The results indicated that there was total 27 pumped storage hydropower projects constructed and the cumulative embodied carbon emissions were 23.83 Mt. Large (1) scale pumped storage hydropower projects accounted for over 75% of the total embodied carbon emissions. Most projects were constructed in the east area of China, Anhui and Zhejiang had the largest embodied carbon emissions. Henan and Inner Mongolia had the largest embodied carbon emission per unit of GDP. Decomposition analysis identifies economic output as the primary emissions driver, offset partially by improvements in carbon intensity (−18%) and capacity efficiency (−9%). This study also predicted that constructing 49 approved pumped storage hydropower projects in China will generate about 53.45 Mt of embodied carbon emissions in the future. To mitigate these emissions, we propose several policy recommendations: firstly, continuous technical innovation is essential for reducing embodied carbon emission intensities; secondly, promoting a circular economy through recycling and resource efficiency can lower emissions and enhance resource availability; thirdly, regional and national policies should be tailored to local conditions to address disparities in emissions; and finally, economic policies such as carbon pricing and resource taxes can incentivize cost management and rational use of carbon-intensive materials. By providing a detailed account of emissions from pumped storage hydropower projects in China, this study fills a crucial research gap and offers valuable insights for policymakers and project developers. Although this study mainly focuses on China, it offers a method to assess the embodied carbon emissions generated by pumped storage hydropower infrastructure construction. Relevant insights can be shared in other countries as well.

However, as an initial attempt, this study still has some limitations. Firstly, regional disparities on embodied carbon emission intensity were ignored since EXIOBASE is a global and national database. This choice reflects a methodological trade-off: the use of a global input–output framework (EXIOBASE, China block) allows for consistent accounting of international supply-chain linkages and long-term time series, which is particularly relevant for large-scale electricity infrastructure construction. In contrast, Chinese MRIO tables would enable detailed interprovincial analysis but are built on different accounting conventions and typically cover shorter periods. Future research could adopt a Chinese MRIO framework to better capture spatial heterogeneity and regional linkages. The LMDI decomposition assumes independence among factors, while in reality some interactions may exist. Although this simplification does not affect the consistency of our results, it suggests that efficiency-related effects should be viewed with caution. Future studies may consider alternative approaches to better capture potential interdependencies. Additionally, this study solely focused on the embodied carbon emissions generated during the construction of pumped storage hydropower infrastructure. In the future, embodied carbon emissions generated in the operation process should be accounted as well to provide a more comprehensive view on environmental impact of pumped storage hydropower.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Teng, X., Liu, F. & Chiu, Y. The impact of coal and non-coal consumption on china’s energy performance improvement. Nat. Resour. Forum. 44, 334–352. https://doi.org/10.1111/1477-8947.12207 (2020).

Xing, X. et al. Spatially explicit analysis identifies significant potential for bioenergy with carbon capture and storage in China. Nat. Commun. 12, 3159. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-23282-x (2021).

Gilfillan, D. & Pittock, J. Pumped storage hydropower for sustainable and low-carbon electricity grids in Pacific rim economies. Energies https://doi.org/10.3390/en15093139 (2022).

IEA. Tracking clean energy progress 2023, Paris. (2023). https://www.iea.org/reports/tracking-clean-energy-progress-2023

Twitchell, J., & Dave, P. Energy Storage Market Transformation through Stored Energy Targets. In 2024 IEEE Electrical Energy Storage Application and Technologies Conference (EESAT), San Diego, CA, USA, 1–6. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1109/EESAT59125.2024.10471208

European Association for Storage of Energy. Energy Storage Targets 2030 and 2050. (2022). https://ease-storage.eu/publication/energy-storage-targets-2030-and-2050/

Kong, Y. et al. Pumped storage power stations in china: the past, the present, and the future. Renew. Sustainable Energy Rev. 71, 720–731 (2017).

IEA. Hydropower special market report, Paris. (2021). https://www.ieahydro.org/publications/international-energy-agency-reports

Al Shaqsi, A. Z., Sopian, K. & Al-Hinai, A. Review of energy storage services, applications, limitations, and benefits. Energy Rep. 6, 288–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2020.07.028 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Carbon peak and carbon neutrality in china: Goals, implementation path and prospects. China Geol. 4, 720–746. https://doi.org/10.31035/cg2021083 (2021).

China Renewable Energy Engineering Institute, Pumped storage hydropower branch of China society for hydropower engineering development report of pumped storage industry 2022. China Water Power Press, Beijing (2023).

Chen, X. & Wenjia, Z. Support carbon neutrality target — Which flexible power source is the best option for China? Energy 285, 128682. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2023.128682

NEA. Medium and long–term development plan for pumped storage (2021–2035). General Department of the National Energy Administration, People’s Republic of China. (2021). http://zfxxgk.nea.gov.cn/2021-09/17/c_1310193456.htm

Xie, Y. et al. Gleaning insights from German energy transition and large-scale underground energy storage for china’s carbon neutrality. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 33, 529–553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2023.04.001 (2023).

Haddad, O. B., Ashofteh, P. S., Rasoulzadeh-Gharibdousti, S. & Mariño, M. A. Optimization model for design-operation of pumped-storage and hydropower systems. J. Energy Eng. 140, 04013016. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)EY.1943-7897.0000169 (2014).

Li, Z. et al. Carbon footprints of pre-impoundment clearance on reservoir flooded area in china’s large hydro-projects: implications for GHG emissions reduction in the hydropower industry. J. Clean. Prod. 168, 1413–1424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.09.091 (2017).

Kusre, B. C., Baruah, D. C., Bordoloi, P. K. & Patra, S. C. Assessment of hydropower potential using GIS and hydrological modeling technique in Kopili river basin in Assam (India). Appl. Energy. 87, 298–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2009.07.019 (2010).

Ge, S., Gao, Y., Yao, X. & Liu, J. Can pumped-storage power in underground coal mine reduce carbon emissions? J. Clean. Prod. 255, 120344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120344 (2020).

Wang, J. et al. Assessing the water and carbon footprint of hydropower stations at a National scale. Sci. Total Environ. 676, 595–612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.04.148 (2019).

Kumar, A., Yang, T. & Sharma, M. P. Long-term prediction of greenhouse gas risk to the Chinese hydropower reservoirs. Sci. Total Environ. 646, 300–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.11.427 (2019).

Zhang, J. & Xu, L. Embodied carbon budget accounting system for calculating carbon footprint of large hydropower project. J. Clean. Prod. 96, 444–451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.10.060 (2015).

Almeida, R. M. et al. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions of Amazon hydropower with strategic dam planning. Nat. Commun. 10, 4281. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12179-5 (2019).

He, Y. et al. Factors influencing carbon emissions from china’s electricity industry: analysis using the combination of LMDI and K-means clustering. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 93, 106724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2021.106724 (2022).

Chong, C. H. et al. LMDI decomposition of coal consumption in China based on the energy allocation diagram of coal flows: an update for 2005–2020 with improved sectoral resolutions. Energy 285, 129266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2023.129266 (2023).

Peters, G. P. & Hertwich, E. G. CO2 embodied in international trade with implications forglobal climate policy. Environ. Sci. Technol. 42 (5), 1401–1407. https://doi.org/10.1021/es072023k (2008).

Mi, Z. et al. Chinese CO2 emission flows have reversed since the global financial crisis. Nat. Commun. 8, 1712. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01820-w (2017).

Meng, J. et al. The rise of South–South trade and its effect on global CO2 emissions. Nat. Commun. 9, 1871. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04337-y (2018).

Ali, Y., Pretaroli, R., Socci, C. & Severini, F. Carbon and water footprint accounts of italy: A Multi-Region Input-Output approach. Renew. Sust Energ. Rev. 81, 1813–1824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2017.05.277 (2018).

Duarte, R., Pinilla, V. & Serrano, A. Factors driving embodied carbon in international trade: a multiregional input–output gravity model. Econ. Syst. Res. 30 (4), 545–566. https://doi.org/10.1080/09535314.2018.1450226 (2018).

Ge, Z. et al. Embodied carbon emissions induced by the construction of hydropower infrastructure in China. Energy Policy. 173, 113404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2022.113404 (2023).

Wang, F., Wang, B., Zhou, T., Chen, T. & Ma, J. CO2 emission and organic carbon burial in the Xinanjiang reservoir. Acta Geochim. 36, 465–468. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11631-017-0197-8 (2017).

Behrens, P. et al. Evaluating the environmental impacts of dietary recommendations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 114, 13412–13417. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1711889114 (2017).

Wood, R. et al. Global sustainability accounting—developing EXIOBASE for multi-regional footprint analysis. Sustainability 7, 138–163. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7010138 (2015).

Stadler, K. et al. EXIOBASE 3: developing a time series of detailed environmentally extended multi-regional input-output tables. J. Ind. Ecol. 22, 502–515. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.12715 (2018).

China Electricity Council. Annual compilation of statistics for power industry, 2000–2020.

National Bureau. of Statistics of China, China statistical yearbook, 2000–2020.

Sun, X., Wang, X., Liu, L. & Fu, R. Development and present situation of hydropower in China. Water Policy. 21, 565–581. https://doi.org/10.2166/wp.2019.206 (2019).

Li, H., Jiang, H. D., Dong, K. Y., Wei, Y. M. & Liao, H. A comparative analysis of the life cycle environmental emissions from wind and coal power: evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 248, 119192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119192 (2020).

Wei, W. et al. Embodied greenhouse gas emissions from Building china’s large-scale power transmission infrastructure. Nat. Sustain. 4, 739–747. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-021-00704-8 (2021).

Wei, W. et al. Toward carbon neutrality: Uncovering constraints on critical minerals in the Chinese power system. Fundamental Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fmre.2022.02.006 (2022).

Wang, P. et al. Critical mineral constraints in global renewable scenarios under 1.5°C target. Environ. Res. Lett. 17 (12), 125004. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aca4ea (2022).

Funding

This work was supported by the research incubation program of Xiamen University Tan Kah Kee College (Grant No. YM2023W02).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zewen Ge: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing, Supervision. Jiayi Zhang: Formal analysis, Software, Visualization. Zixin Qiu: Formal analysis, Software, Methodology. All the authors agree to publish this study in this journal.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ge, Z., Zhang, J. & Qiu, Z. Embodied carbon emissions of pumped storage hydropower infrastructure construction in China across temporal–spatial and driving factors dimensions. Sci Rep 15, 45012 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30019-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30019-z