Abstract

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has a higher prevalence in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients compared to the general population. Herein, the prevalence and predictors of NAFLD in a large IBD cohort were evaluated by non-invasive method. A multicenter retrospective study was conducted among 592 inpatients diagnosed with IBD who underwent abdominal ultrasound. Characteristics of IBD and metabolic status were collected, presence of hepatic steatosis was assessed, and predictors for NAFLD were analyzed. A total of 509 IBD patients were included in the final analysis including 245 NAFLD (48.1%) subjects. IBD patients with NAFLD were older than those without NAFLD. NAFLD patients had more diabetes, higher body mass index (BMI) and more obesity. The patients with NAFLD showed increased levels of gamma-glutamyl transferase, uric acid, glycemia, triglycerides and low density lipoprotein. The localization of ulcerative colitis showed a more extensive trend in NAFLD patients compared with non-NAFLD subjects. Multivariate analysis showed that NAFLD was independently associated with BMI levels, biologic agents using, and prior surgery in IBD patients. NAFLD is common in Chinese patients with IBD. Obesity and biologics using are risk factors, and prior intestinal surgery is a protective factor of NAFLD development. These findings should be interpreted in the context of an inpatient-based study population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) ranges from hepatic steatosis to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, which is considered to have a close association with metabolic syndrome1. For the past few decades, NAFLD has become the most common chronic liver disease as an important cause of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma2,3. Although NAFLD is typically related to obesity-associated metabolic disorders, it also increasingly occurs in non-obese individuals including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients4. In recent years, increasing studies have showed higher prevalence of NAFLD in IBD patients compared with the general population5, suggesting that intestinal inflammation and interruption of the enterohepatic circulation may also play an important role in NAFLD pathogenesis.

In IBD patients, the development of NAFLD might be associated with disease-related factors including duration of IBD, disease activity and previous intestinal surgery, or the intestinal inflammation control with medication, such as glucocorticoids, immunosuppressants and biologics6. Meanwhile, metabolic factors such as advanced age, high body mass index (BMI) and lipid consumption might increase the risk of NAFLD in patients with IBD5,7. Recently, the prevalence of NAFLD and factors related to the development of NAFLD in IBD patients have been revealed based on the data pooled from Europe, North America, and Asia, including India, Japan, and South Korea5. Nevertheless, all of the available studies concerning NAFLD in IBD did not include the statistics of Chinese mainland accounting for approximately 18% population around the world.

The concurrence of IBD and NAFLD raises some challenges for patient management. About 5% of IBD patients can experience severe liver diseases8, whereas liver inflammation and abnormal biochemical tests related to NAFLD may complicate IBD therapy. Besides, a higher inpatient mortality was reported in patients with IBD and concomitant chronic hepatobiliary disease comparing with IBD alone9.

This study aims to evaluate the prevalence and risk factors for NAFLD in a large nationwide IBD cohort. The current study focuses on the coexistence of NAFLD and IBD, which may provide useful insights on the complicated relations between metabolic disturbance, gut dysfunction and intrahepatic cellular abnormality.

Materials and methods

Study design and population

Between January 2018 and June 2022, consecutive IBD inpatients in regular follow-up were evaluated through medical examination and blood tests in 9 representative tertiary digestive centers in China covering a large area of the country (Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, Wuxi Second People’s Hospital, Huai’an Second People’s Hospital, Zhangzhou Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University, Changzhou Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Anqing Municipal Hospital, Zhangjiagang First People’s Hospital, The First Affiliated Hospital of Wannan Medical College, and Yancheng Third People’s Hospital). Endoscopy was performed according to the international guidelines for routinely follow-up10. At the time of enrollment, all patients underwent abdominal ultrasound to establish the presence of NAFLD. The research project has been approved by Nanjing University Medical School Affiliated Drum Tower Hospital Medical Ethics Committee (2023-554-01). Each participating institute obtained individual ethical approval from its respective ethics committee before the study was conducted. The medical ethics review committee waived the need for informed consent owing to the retrospective observational study design. The study was conducted based on the Helsinki Declaration.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients aged 14 years or older with a diagnosis of IBD for at least 6 months who underwent abdominal ultrasound were enrolled. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, significant alcohol consumption, defined as higher than 20 g in females and 30 g in males daily, and any other known chronic liver disease different from NAFLD, such as genetic, cholestatic, autoimmune factors. The presence of other causes of chronic liver disease was excluded through laboratory tests (hepatotropic viruses markers, aminotransferases, cholestatic indices, serum ferritin, transferrin saturation, autoimmune markers, and ceruloplasmin) and, when necessary, through radiological exams [computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)].

Data collection and diagnostic criteria

From the electronic medical records, demographic data, disease duration, prior surgery, comorbidities, the use of medications and fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), laboratory data, IBD clinical activity score, disease classification and extent, and disease recurrence were collected. Laboratory data including the biochemical assessment of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), albumin, white blood cell (WBC) and platelet counts, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP) and calprotectin, and the metabolic parameters of triglycerides, cholesterol, low density lipoprotein (LDL), high density lipoprotein (HDL) and fasting glycemia were performed within 3 months before the enrollment. The use of medications was recorded mainly including 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA), glucocorticoids, immunosuppressants and biologic agents. Obesity was defined as a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 in accordance with the criteria of the Asian-pacific region11.

According to international guidelines, IBD was diagnosed in combination of clinical examination, imaging, endoscopy, chemical and histologic analyses12,13. The disease activity was calculated based on the Crohn’s disease activity index (CDAI) score and modification of Mayo Score system for Crohn’s disease (CD)14 and ulcerative colitis (UC)15,16, respectively. The CDAI score ≥ 150 for CD and the Mayo score ≥ 3 for UC were used to stratify IBD activity14,15. Disease extension was evaluated by endoscopy or radiologic methods including CT and MRI. According to the Montreal classification17, IBD was conventionally referred as “extensive disease” when inflammation involved beyond the splenic flexure for UC, and when inflammation affected bowel segment longer than 100 cm for CD, regardless of the location18.

All subjects underwent abdominal ultrasound examination in the course of disease. At enrollment, an expert gastrointestinal radiologist reevaluated the abdominal ultrasound to estimate the presence of steatosis as recently reported19. In detail, the presence of hepatic steatosis was according to the evidence of a bright liver ultrasonographic pattern with increased liver-kidney contrast.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as median [interquartile range (IQR)] or mean [standard deviation (SD)] as appropriate, and categorical as number of cases (percentage). The Student’s t test was performed to compare continuous variables after assessing for normality, and Chi-square test for categorical variables. P value < 0.05 was considered statistically different. Screening all variables with P value < 0.2, a multivariate binary logistic regression analysis was performed using the presence/absence of NAFLD as dependent variable and metabolic-, clinical- and laboratory-related variables as predictors. Missing values were processed using the baseline observation carried forward method. Existing excessive missing data because of CD patients, Mayo score and UC localization were not included in statistics. Odd ratios (OR) and the 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated, and P value < 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed with the software package SPSS 21.0 (IBM, Armonk, United States).

Results

Study chart

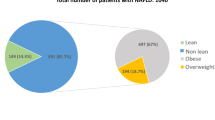

According to the inclusion criteria, 592 consecutive IBD patients were evaluated for eligibility. Of these, 83 patients were excluded based on the exclusion criteria. The characteristics of the remaining 509 individuals, 245 IBD patients with NAFLD and 264 IBD patients without NAFLD were retrospectively analyzed (Fig. 1).

Characteristics of the enrolled population

The mean age of enrolled IBD patients was 48.8 years (range from 15 to 87 years). The male-to-female ratio was 0.99. Of the included patients, 324 (63.7%) were identified as UC and 185 patients (36.3%) as CD. Due to the inclusion of hospitalized patients, most IBD patients (401/509, 78.8%) showed active disease. The prevalence of NAFLD was determined in 245 patients (48.1%). Nevertheless, obesity only accounted for 13.4% (68/509) according to BMI in the enrolled IBD patients.

Comparison between IBD patients with and without NAFLD

The characteristics of studied IBD patients with and without NAFLD were summarized. In terms of metabolic data (Table 1), there were no significant differences between the two groups in gender, smoking, low alcohol consumption (less than 20 g in females and 30 g in males daily), and hypertension. IBD patients with NAFLD were statistically older than those without NAFLD (52.0 vs. 47.5 years, P = 0.012). Moreover, NAFLD patients suffered from more diabetes (11.0% vs. 3.8%, P = 0.002). Patients with IBD and NAFLD had higher BMI than IBD patients without NAFLD (22.5 vs. 20.6 kg/m2, P < 0.001). Meanwhile, the proportion of obesity was higher in patients with IBD and NAFLD (19.2% vs. 8.0%, P < 0.001).

In the aspect of clinical data (Table 2), there were no statistical differences between the two groups in IBD diagnosis (CD or UC), prior surgery, duration of IBD, disease activity (CDAI for CD and Mayo score for UC), extraintestinal manifestation (EIM), extensive disease, CD localization, CD behavior, IBD relapse, medications (5-ASA, glucocorticoids, immunosuppressants, and biologic agents), and FMT. The localization of UC showed a more extensive trend in NAFLD patients (P = 0.038).

Among laboratory tests (Table 3), there were no significant differences between IBD patients with and without NAFLD in ALT, AST, ALP, Albumin, WBC, platelets, ESR, CRP, calprotectin, cholesterol, and HDL. Compared with IBD patients without NAFLD, the patients with NAFLD showed increased levels of GGT (22.0 vs. 18.1 U/L, P = 0.004), uric acid (293.0 vs. 271.0 µmol/L, P = 0.013), glycemia (4.8 vs. 4.6 mmol/L, P < 0.001), triglycerides (1.2 vs. 1.1 mmol/L, P = 0.002) and LDL (2.5 vs. 2.3, P = 0.019).

Risk factors for NAFLD

Multivariate analysis showed that NAFLD in IBD was independently associated with BMI levels (OR = 1.182, 95% CI 1.085–1.288, P < 0.001), the presence of prior surgery (OR = 0.480, 95% CI 0.250–0.920, P = 0.027), and the application of biologic agents (OR = 2.263, 95% CI 1.200–4.270, P = 0.012). Overall details are summarized in Table 4.

Discussion

Accompanied by increasing prevalence of obesity-associated metabolic disorders, the global prevalence of NAFLD has been estimated to 25% varying with different regions of the world. Compared with the general population, a higher prevalence of NAFLD has been found in IBD patients5. In our study, the prevalence of NAFLD in IBD patients was higher than most previous studies reported to vary from 8% to 59%6,20,21,22,23,24. The prevalence can be influenced by many factors, such as inclusion criteria, diagnostic methods and regional differences. In this study, the included individuals were all inpatients with a large proportion of active and relatively severe diseases. A retrospective study reported 29 of 49 (59%) IBD patients had evidence of NAFLD based on pathology report21. Pathological results are the gold standard for diagnosing NAFLD, but ultrasonography has been a widely accessible imaging technique for the detection of hepatic steatosis with satisfactory sensitivity and specificity in comparison with pathology25. Additionally, the introduction of non-invasive biomarkers for NAFLD prediction with metabolic score for insulin resistance, lipid accumulation product, and triglyceride/high-density lipoprotein into clinical assessments of IBD patients could prove useful in preventing liver and cardiovascular complications26.

The prevalence of malnutrition in IBD patients can go up to 85%6,27 resulted from malabsorption, reduced food intake, chronic proteins loss, and intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Hence, IBD patients with NAFLD can be classified as lean NAFLD to some extent. The BMI in patients with IBD and NAFLD was 22.5 in this study, conforming to the definition of lean NAFLD. Though IBD patients may suffer fewer metabolic risk factors28, accompanying malnutrition can promote lipid accumulation in the liver29. On the other hand, It should be noted that most lean NAFLD patients exist “metabolic obesity” with insulin resistance and increased visceral fat, which can explain the concurrent differences in diabetes, glycemia, uric acid, triglycerides and LDL between IBD patients with lean NAFLD and without NAFLD. Aging was also a stimulation to the metabolic risk factors related to NAFLD with older age in IBD and NAFLD patients. The difference in GGT between the two groups might exist as a result rather than the cause of NAFLD.

IBD-related data have been reported as risk factors of NAFLD including disease duration, disease activity, and history of small bowel resection6,27,30. The observed protective effect of prior intestinal surgery warrants consideration. While counterintuitive, this association may be attributed to postsurgical alterations in gut microbiota, bile acid metabolism, or nutrient absorption that could potentially modulate hepatic steatosis. However, this finding should be interpreted with caution and requires validation in prospective studies. According to our study, the type of IBD seemed to have no influence on NAFLD. Nevertheless, CD was showed to be an independent risk factor for liver fibrosis in patients with IBD and NAFLD, which suggested that fibrosis progression should be monitored in CD patients with simultaneous NAFLD31. In the present study, more extensive inflammation in UC significantly increased hepatic steatosis. However, other IBD-related factors such as disease duration, prior surgery, disease activity score, EIM, CD localization and behavior, and disease relapse were undifferentiated distinguished from previous reports. Similarly, IBD-related therapies including medications and FMT did not show effects on the occurrence of NAFLD, which was in conflict with a previous study20. The study has found a relationship of glucocorticoids with NAFLD in IBD patients. Interestingly, biologics use became an independent risk factor in the multivariate analysis in addition to BMI. Moreover, our study demonstrated that FMT had low correlation with NAFLD in IBD patients (OR = 3.036, 95% CI 0.891–10.350, P = 0.076). We speculate that intestinal inflammation or microbiota may interact with metabolism, thereby affecting NAFLD. Further studies are needed to elucidate the underlying mechanisms.

The early treatment with intestinal resection might have a protective effect on NAFLD in IBD patients (OR = 0.480, 95% CI 0.250–0.920, P = 0.027) through the reducing intestinal inflammation and improvement of metabolic profile. On the contrary, advanced treatments such as biologics use and FMT became risk factors on NAFLD in IBD patients. The association between biologic therapy and NAFLD may be influenced by confounding with indication, as patients receiving biologics often have more severe or long-standing IBD. Our retrospective design cannot establish causality, and future studies with detailed treatment data are needed to clarify this relationship. A previous study showed that the prevalence of NAFLD was 54% (43/80) in IBD patients receiving anti-TNF therapy32. Further researches need to clarify whether early biologics use and FMT can effectively reduce the occurrence of NAFLD.

There are several strengths to our study, including multicentric design, well-defined study population, and consistent expert ultrasonic assessment. However, this study also has some limitations. First, a key limitation of our study is its restriction to an inpatient cohort. This population is inherently biased toward individuals with more active or severe IBD, which may limit the generalizability of our findings. The observed NAFLD prevalence and its associations with factors like biologic agent use might differ in an outpatient setting with less severe disease. Therefore, caution should be exercised when extrapolating these results to the entire IBD spectrum. Nevertheless, this suggests that we should pay more attention to NAFLD when facing hospitalized IBD patients. Second, we decided the diagnosis of NAFLD based on ultrasound imaging as a substitute for invasive liver biopsy. Studies with large sample employing liver biopsy in IBD patients seem impossible to be conducted in consideration of the invasiveness, ethical concern, and high cost33. Among the noninvasive diagnostic tools for NAFLD, CT and MRI may have a superior sensitivity and specificity comparing with ultrasound imaging34. However, the sensitivity using these imaging techniques decreases when liver fat content is under 30%35. In the patients with morbid obesity, the sensitivity can be lower using ultrasound imaging because of the influence of abdominal fat34. The use of ultrasound without steatosis grading, while clinically practical, may limit the precise quantification of hepatic fat accumulation compared to MRI/CT or controlled attenuation parameter. Although the proportion of obesity was at a lower level in our study, this characteristic might still affect the incidence of NAFLD. This methodological aspect should be considered when interpreting our findings. Third, our study did not classify the degree of hepatic steatosis making it difficult to determine the effects of various factors on the severity of NAFLD. In addition, this study did not explore the impact of various variables on hepatic fibrosis. Fourth, some interested data were missing such as the frequency, dosage and duration of biologic agents because of the retrospective design. A future prospective study can address the drug effects that IBD patients with NAFLD receive biologics at the time of assessment. Despite using some statistical methods, the missing values had an influence on the final results. Moreover, a prospective study can avoid data loss and add some additional variables.

Conclusions

IBD patients appeared to have a higher prevalence for NAFLD compared to the general population. The higher BMI and the use of biological agents are independent risk factors for NAFLD in patients with IBD. On the contrary, prior surgery is an independent protective factor for NAFLD in IBD patients. Therefore, alleviating intestinal inflammation by appropriate medication or surgical treatment may be an effective measure to avoid or delay the occurrence of NAFLD. Further studies aimed at clarifying the timing of surgery and biologics application are needed. In addition, healthy lifestyle and weight may also be helpful to keep away from NAFLD in IBD patients.

Data availability

The author confirms that all data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Younossi, Z. et al. Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 15, 11–20 (2018).

Younossi, Z. M. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease - A global public health perspective. J. Hepatol. 70, 531–544 (2019).

Huang, T. D., Behary, J. & Zekry, A. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a review of epidemiology, risk factors, diagnosis and management. Intern. Med. J. 50, 1038–1047 (2020).

Ye, Q. et al. Global prevalence, incidence, and outcomes of non-obese or lean non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 5, 739–752 (2020).

Lin, A., Roth, H., Anyane-Yeboa, A., Rubin, D. T. & Paul, S. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 27, 947–955 (2021).

Bessissow, T. et al. Incidence and predictors of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease by serum biomarkers in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 22, 1937–1944 (2016).

Sartini, A. et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease phenotypes in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Cell. Death Dis. 9, 87 (2018).

Patel, P. & Dalal, S. Hepatic manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Liver Dis. (Hoboken). 17, 292–296 (2021).

Nguyen, D. L., Bechtold, M. L. & Jamal, M. M. National trends and inpatient outcomes of inflammatory bowel disease patients with concomitant chronic liver disease. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 49, 1091–1095 (2014).

McCain, J. D., Pasha, S. F. & Leighton, J. A. Role of capsule endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastrointest. Endosc Clin. N Am. 31, 345–361 (2021).

Oh, S. W. Obesity and metabolic syndrome in Korea. Diabetes Metab. J. 35, 561–566 (2011).

Gionchetti, P. et al. 3rd European Evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of crohn’s disease 2016: part 2: surgical management and special situations. J. Crohns Colitis. 11, 135–149 (2017).

Magro, F. et al. Third European Evidence-based consensus on diagnosis and management of ulcerative Colitis. Part 1: Definitions, diagnosis, Extra-intestinal Manifestations, Pregnancy, cancer Surveillance, Surgery, and Ileo-anal pouch disorders. J. Crohns Colitis. 11, 649–670 (2017).

Best, W. R., Becktel, J. M., Singleton, J. W. & Kern, F. Jr. Development of a crohn’s disease activity index. National cooperative crohn’s disease study. Gastroenterology 70, 439–444 (1976).

Schroeder, K. W., Tremaine, W. J. & Ilstrup, D. M. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. A randomized study. N Engl. J. Med. 317, 1625–1629 (1987).

D’Haens, G. et al. A review of activity indices and efficacy end points for clinical trials of medical therapy in adults with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 132, 763–786 (2007).

Satsangi, J., Silverberg, M. S., Vermeire, S. & Colombel, J. F. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut 55, 749–753 (2006).

Gomollón, F. et al. 3rd European Evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of crohn’s disease 2016: part 1: diagnosis and medical management. J. Crohns Colitis. 11, 3–25 (2017).

Paige, J. S. et al. A pilot comparative study of quantitative Ultrasound, conventional Ultrasound, and MRI for predicting Histology-Determined steatosis grade in adult nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 208, W168–W177 (2017).

Sourianarayanane, A. et al. Risk factors of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J. Crohns Colitis. 7, e279–e285 (2013).

Bosch, D. E. & Yeh, M. M. Primary sclerosing cholangitis is protective against nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in inflammatory bowel disease. Hum. Pathol. 69, 55–62 (2017).

Bargiggia, S. et al. Sonographic prevalence of liver steatosis and biliary tract stones in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: study of 511 subjects at a single center. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 36, 417–420 (2003).

Carr, R. M. et al. Intestinal inflammation does not predict nonalcoholic fatty liver disease severity in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Dig. Dis. Sci. 62, 1354–1361 (2017).

Likhitsup, A. et al. Prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease on computed tomography in patients with inflammatory bowel disease visiting an emergency department. Ann. Gastroenterol. 32, 283–286 (2019).

Hernaez, R. et al. Diagnostic accuracy and reliability of ultrasonography for the detection of fatty liver: a meta-analysis. Hepatology 54, 1082–1090 (2011).

Abenavoli, L. et al. Use of metabolic scores and lipid ratios to predict metabolic Dysfunction-Associated steatotic liver disease onset in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. J. Clin. Med. 14, 2973 (2025).

Bamba, S. et al. Sarcopenia is a predictive factor for intestinal resection in admitted patients with crohn’s disease. PLoS One. 12, e0180036 (2017).

Cheng, Y. L. et al. Prognostic nutritional index and the risk of mortality in patients with acute heart failure. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 6, e004876 (2017).

Gibiino, G. et al. The other side of malnutrition in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): Non-Alcoholic fatty liver disease. Nutrients 13, 2772 (2021).

Cushing, K. C., Kordbacheh, H., Gee, M. S., Kambadakone, A. & Ananthakrishnan, A. N. Sarcopenia is a novel predictor of the need for rescue therapy in hospitalized ulcerative colitis patients. J. Crohns Colitis. 12, 1036–1041 (2018).

Martínez-Domínguez, S. J. et al. Crohn´s disease is an independent risk factor for liver fibrosis in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 120, 99–106 (2024).

Likhitsup, A. et al. High prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with inflammatory bowel disease receiving anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy. Ann. Gastroenterol. 32, 463–468 (2019).

Rockey, D. C., Caldwell, S. H., Goodman, Z. D., Nelson, R. C. & Smith, A. D. Liver biopsy. Hepatology 49, 1017–1044 (2009).

Wieckowska, A. & Feldstein, A. E. Diagnosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: invasive versus noninvasive. Semin Liver Dis. 28, 386–395 (2008).

Hamer, O. W. et al. Fatty liver: imaging patterns and pitfalls. Radiographics 26, 1637–1653 (2006).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YH Shen and XQ Zhang generated the ideas and designed experiments. F Liang, BJ Wen, WP Huang and QQ Li performed most experiments and organized the figure. Y Zhang, C Fu, HJ Ge and XM Sun participated in experimentation. WD Fan, Y Xie, CY Peng and L Wang provided important materials. YH Shen and LL Zhang wrote the manuscript. All authors read, approved the final manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shen, Y., Liang, F., Li, Q. et al. The prevalence and predictors of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Chinese patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a multicenter retrospective study. Sci Rep 16, 515 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30031-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30031-3