Abstract

Oncoplastic breast-conserving surgery (OBCS) comprises diverse techniques aimed at enhancing aesthetic outcomes and safety in breast cancer treatment. However, a knowledge gap exists in understanding the comprehensive assessment of safety factors and satisfaction rates associated with OBCS techniques. This systematic review and meta-analysis aim to compare volume displacement (VD) and volume replacement (VR) techniques concerning oncological safety, complication rates and patient satisfaction. A systematic literature search was conducted in three databases—PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library (CENTRAL)—up to November 2023. Original articles with quantitative satisfaction rates, recurrence, re-excision, margin status, and complications (hematoma, seroma, wound infection, fat necrosis). The systematic search identified 17,374 records, with 80 eligible studies and 46 providing quantitative data. Results showed comparable oncological safety between VD and VR techniques, including similar recurrence (Prop: 0.02; CI 0.02–0.03) and re-excision rates (Prop: 0.05; CI 0.04–0.07). VR techniques had a higher incidence of fat necrosis (Prop: 0.07; CI 0.04–0.12). Overall satisfaction was high (Prop: 0.83; CI 0.78–0.87), with VD yielding the highest satisfaction (Prop: 0.93; CI 0.85–0.97). Oncoplastic breast-conserving surgery emerges as a successful approach for treating early-stage breast cancer, characterized by low associated risks and high satisfaction rates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common malignancy among women globally1 and often requires surgery2 impacting both physical and psychological well-being3. Oncoplastic breast-conserving surgery (OBCS) combines oncological resection with plastic surgery techniques to optimize aesthetic outcomes without compromising cancer control. The two main approaches are volume displacement (VD) and volume replacement (VR). Despite OBCS’s growing use, evidence comparing VD and VR remains unclear, particularly regarding oncological safety, complications, and patient satisfaction4. Although studies suggest OBCS yields high patient satisfaction5 and low complication rates6, variability in study designs, outcome measures, and reporting practices complicates direct comparisons7. Key clinical outcomes such as recurrence, margin positivity, re-excision, and postoperative complications (hematoma, fat necrosis, wound infection) are inconsistently reported.

In contemporary discourse, numerous surgeons advocate for the superiority of either VR or VD techniques in OBCS. However, the lack of standardized tools and heterogeneous reporting practices across studies further complicate comparisons between VD and VR techniques. This variability underscores the need for a comprehensive synthesis of the available evidence to guide clinical practice.

In oncoplastic breast-conserving surgery, two major reconstructive strategies can be distinguished based on the mechanism of volume management8. VD techniques rely on parenchymal reshaping and tissue redistribution within the same breast following tumor excision. They are typically indicated for patients with moderate to large breasts and smaller tumor-to-breast volume ratios, where tissue rearrangement can help restore contour symmetry. Contraindications include small breast size or limited glandular mobility. VR techniques, on the other hand, involve the reconstitution of resected breast tissue by introducing autologous flaps or grafts, such as LICAP (Lateral Intercostal Artery Perforator), AICAP (Anterior Intercostal Artery Perforator), TDAP (Thoracodorsal Artery Perforator), LD (Latissimus Dorsi), DIEP (Deep Inferior Epigastric Artery Perforator), TRAM (Transverse Rectus Abdominis Myocutaneous). VR is preferred when large defects must be replaced in patients with smaller breasts or when tumor excision results in significant volume loss9. While both approaches achieve oncological safety and cosmetic restoration, VR generally carries longer operative times, donor-site morbidity, and higher risks of flap-related complications, such as seroma or fat necrosis. In contrast, VD procedures are more limited by parenchymal tension and asymmetry.

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to compare VD and VR techniques in oncoplastic breast-conserving surgery. Specifically, we evaluate their respective oncological safety outcomes, complication profiles, and patient satisfaction rates. By synthesizing data from existing literature, we aim to offer evidence-based insights to support clinical decision-making in oncoplastic breast surgery, ultimately improving both oncological and aesthetic outcomes for patients undergoing breast-conserving procedures10.

Methods

The study was performed according to the Cochrane Handbook’s recommendations for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.311. The study was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42023477714) and adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines12. All authors have read the PRISMA 2020 (Supplementary Table S1) checklist, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to it.

Eligibility criteria

We included all studies that met the following pre-specified inclusion criteria: women underwent partial breast reconstruction using volume replacement or displacement in breast-conserving surgery for early breast cancer (cT1–cT2). The primary outcome was patient-reported satisfaction rates for all OBCS techniques. The secondary outcomes included oncological safety factors and complications. Literature published in English or Chinese was used.

In our study, it was intended to exclude women with advanced breast cancer (cT3 or higher) and male participants with any stage of breast cancer.

For the purpose of this study, VD was defined as parenchymal reshaping or redistribution after wide local excision without flap transfer, whereas VR referred to reconstruction using autologous tissue flaps. These categories were analyzed separately, recognizing their distinct clinical indications and complication profiles.

Literature search

A comprehensive search across three databases was conducted: MEDLINE (via PubMed), EMBASE, and Cochrane Library (CENTRAL) on November 20, 2023 (Supplementary Table S2). The systematic search of references was conducted by Citationchaser13 on January 17, 2024. For inaccessible articles, we requested full-text access via ResearchGate or email on January 4, 2024.

Selection and data extraction

Duplicates were removed using EndNote version 21 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA)14. The research team conducted a title-abstract and full-text assessment using Rayyan15, by two independent reviewers (LNy and ACL) overseeing the screening process for eligible studies. Cohen’s kappa coefficient was calculated at both levels to access the inter-reviewer agreement. The conflict resolution was conducted by an independent third reviewer (ZK).

Data items

The following data was extracted from each eligible article: first author, publication year, countries, study design, gender, age, number of patients, confounders (BMI, smoking, DM, breast size, adjuvant and neoadjuvant therapy), overall satisfaction, and the satisfaction score in detail, follow-up time, parameters regarding oncological safety such as recurrence rate, re-excision rate, positive margins, secondary mastectomy rate, distant metastases, and complications including bleeding, hematoma, dehiscence, swelling, infection, etc. Margin positivity was standardized according to the most commonly reported criteria, corresponding to ‘no tumor on ink’ for invasive carcinoma and a 2 mm margin threshold for DCIS, where available. Only a few included studies explicitly described their margin evaluation methods; therefore, DCIS and invasive carcinoma were analyzed together, as both groups may require reconstructive intervention. Re-excision was defined as any additional breast-conserving procedure or completion mastectomy performed after the primary surgery. Although we attempted to extract information regarding the re-excision time window, this was inconsistently reported across studies. In most cases, re-excision involved completion mastectomy, but data were insufficient for quantitative analysis. The classification of interventions was based on the recommendations of Clough et al.16. The data were extracted to a predefined Excel sheet (Office 365, Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA).

Study risk of bias (ROB) assessment and quality of evidence

The evaluation of (ROB) was independently conducted by two independent reviewers (LENy, ACL). Disagreements were resolved by a third independent reviewer (ZK). Quality was assessed using the Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies (MINORS) system17. A grading assessment utilizing GRADEPro18 was established to evaluate the level of evidence.

Synthesis methods

Both qualitative and quantitative syntheses were performed, with a minimum of three studies required for meta-analysis. A random-effects model using a frequentist approach pooled effect sizes, with proportions/prevalence reported alongside 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Random intercept logistic regression was also applied.

The pooled CI was modified using the Hartung-Knapp method for a more conservative estimate. Heterogeneity variance (tau-square, τ2) was assessed via the maximum likelihood method, while Higgins and Thompson’s I2 statistics evaluated heterogeneity. Statistical significance was determined if the CI excluded the null value.

Findings were summarized using forest plots, with prediction intervals reported where applicable. Model fitting parameters and potential outliers were explored using influence measures and plots. Statistical analyses were conducted using R, Stata 15.1 SE, and Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software. Pooled hazard ratios (HRs) and odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs were calculated for recurrence, re-excision, and treatment groups. A DerSimonian-Laird random-effects model was applied. Forest plots visualized pooled and individual study results.

Analyses were excluded if HRs had asymmetrical CIs. I2 and χ2 tests assessed heterogeneity, with p < 0.1 indicating statistical significance. Egger’s test and funnel plots were used to assess publication bias for analyses including at least ten studies. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Literature search

The primary literature search provided 17,374 results after duplicate removal and screening; from the remaining 13,533 articles, 13,078 were excluded based on title and abstract (Cohen’s Kappa: 0.89). From the remaining 455 articles, 70 studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria based on full text (Cohen’s Kappa: 0.98), with 46 studies providing adequate data for quantitative analysis19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64. The details of the selection process are summarized in Fig. 1.

Basic characteristics of included studies

This meta-analysis included 3434 patients, all women between 20 and 86. 1845 underwent volume replacement19,21,22,23,29,30,34,35,36,37,38,39,42,43,44,46,47,48,49,51,53,54,55,57,58,61,62,63,64 and 1589 volume displacement20,24,25,26,27,28,31,32,33,39,40,41,45,50,52,54,56,59,60 surgery. The characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1.

In the case of studies19,23,24,26,30,31,32,34,35,36,37,38,39,42,43,44,45,48,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,60,61,63,64, for the reason of the high number of reported individual interventions and the purpose of efficient subgrouping, we post-hoc categorized volume replacement techniques into either latissimus dorsi flaps 19,30,34,35,39,43,48,51,55 or perforator flaps19,23,36,37,38,39,42,44,45,52,53,54,57,61,63,64. In a similar manner, volume displacement techniques were grouped based on their application in the medial24,26,31,45,56, lateral39, or cetral24,31,32,39,50,54,60 quadrants. The detailed forest plot is shown in Fig. 2.

While a few studies used BREAST-Q or numerical scales to assess satisfaction, their number was insufficient for reliable quantitative synthesis. Consequently, these were excluded from the satisfaction analysis. Only studies reporting dichotomous satisfaction outcomes (satisfied vs. not satisfied) were included to maintain consistency and comparability across datasets.

To explore potential sources of heterogeneity, subgroup analyses were conducted according to the different surgical techniques, as detailed in the Supplementary Figs. S7–S12. These subgroup analyses focused on oncological safety parameters, patient satisfaction, and complication rates. Other aspects of heterogeneity, such as differences in tumor characteristics, breast size, and geographic distribution, were not analyzed statistically.

Oncological safety

An evaluation of recurrence rates across 31 studies20,21,22,24,26,27,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,39,40,41,45,46,48,49,51,52,54,55,56,58,59,62,63,64, involving 3654 patients and 55 events, demonstrated no statistically significant difference between the two subgroups. Recurrence definitions varied among studies; however, in this analysis, we specifically focus on local recurrence. The overall incidence was equivalently low in VR and VD, providing a pooled proportion of 0.02 (95 CI 0.02–0.03, I2 = 4%). The summary is shown in Fig. 3. We did not observe any dissimilarities between the two methods regarding the re-excision factor, identifying an overall rate of 5% (CI 0.04–0.07, I2 = 66%, Supplementary Fig. S1. Similarly, no disparities were observed in positive margins, with a proportion of 0.07 (CI 0.05–0.09, I2 = 59%, Supplementary Fig. S2. Margin positivity was defined according to national guidelines, with most considering 2 mm clearance for invasive tumors65.

Complications

For hematoma incidence, 26 studies19,20,21,22,23,25,27,28,29,31,32,33,39,40,41,44,45,48,49,50,54,55,56,58,59,60,61,64 were combined, yielding a proportion of 0.04 (CI 0.03–0.06, I2 = 32%). Subgroup analysis demonstrated no significant difference. Hematomas were classified based on clinical significance, with major hematomas requiring reoperation and minor ones managed conservatively. The hematoma incidence is summarized in Fig. 4. Upon examining the incidence of fat necrosis across 20 studies22,23,24,27,30,33,38,39,40,41,42,45,46,47,52,53,54,55,57,58,62. The approach involving VR had a higher incidence, with a prevalence of 7% (CI 0.04–0.12, I2 = 54%). In contrast, the VD group displayed lower incidence, with a proportion of 0.04 (CI 0.01–0.08, I2 = 66%). Fat necrosis, clinically or radiologically confirmed areas of fat liquefaction or fibrosis, was defined variably across studies, with some relying on clinical diagnosis and others on radiological or pathological confirmation. Summarized plots can be found in Supplementary Fig. S3. In the aggregate, fat necrosis occurrence was 5% (CI 0.03–0.09, I2 = 59%). Wound infection rates, evaluated based on studies that clearly defined infection severity, ranged from minor infections treated with oral antibiotics to severe cases requiring reoperation or intravenous antibiotic therapy (CI 0.03–0.06, I2 = 28%, Supplementary Fig. S4). Seroma rates, clinically or radiologically detected fluid collections requiring aspiration, were excluded from the analysis due to inconsistent definitions and limited clinical relevance in OBCS.

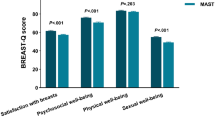

Satisfaction

Our meta-analysis involved synthesizing 22 studies19,20,22,23,24,30,31,34,35,38,39,42,43,44,45,49,51,52,53,54,56,61,63,64 with 694 observations, accounting for 571 events. The pooled overall satisfaction proportion was 0.83 (CI 0.78–0.87, I2 = 51%). We found no clinical and mathematical subgroup differences for VD and VR outcomes. The results are summarized in Fig. 2. Satisfaction was measured using validated patient-reported outcome measures such as the BREAST-Q. In cases where data were not presented in this format, patient satisfaction was evaluated using satisfaction tools.

Risk of bias assessment

The analysis showed that most studies were comprehensive in reporting their aims, patient inclusion, and appropriateness of their endpoints. However, variability in the scores was observed in the areas of unbiased assessment of study endpoints and prospective calculation of the study size. Most of the studies had an appropriate follow-up period relevant to the aim of the study. However, scores varied in the baseline equivalence of groups. In summary, out of 16 points, 9 or under were considered a high Risk of Bias (Fig. 5, ROB detailed in Supplementary Fig. S5). Due to the inclusion of single-arm studies and the absence of randomized controlled trials (RCTs), the examination of patient satisfaction yielded relatively low quality, according to GRADEPro (Supplementary Fig. S6).

Discussion

After our thorough examination, our results suggest that VD and VR are equally satisfactory, oncologically safe, and complication-free. VD methods may be preferred for patients with smaller defects or larger breasts, which inherently carry a lower risk of incomplete tumor removal or complications and contribute to a lower incidence of secondary mastectomies. VR techniques, on the other hand, are often used when the defect is larger or moderate or when the breast is smaller, addressing the need for more extensive tissue removal. Furthermore, ensuring symmetry and maintaining the aesthetic appearance of the breast can lead to unsatisfactory results that require revision surgeries66. This variability underscores the need for personalized approaches in OBCS, such as the importance of adapting the methods to the patient’s and tumor’s characteristics. Current evidence does not support the superiority of either VD or VR techniques. Both demonstrate comparable oncological safety and satisfaction. The optimal approach should be selected individually, considering patient anatomy, tumor characteristics, and surgeon expertise. A balanced framework integrating these factors offers the most practical guidance for clinical decision-making.

The high overall satisfaction5 rate of 83% indicates that most patients were pleased with the outcomes of their procedures. However, the moderate level of heterogeneity suggests variability in satisfaction levels across different studies. This variability could be attributed to several factors, including differences in patient populations, surgical techniques, expertise, and postoperative care protocols67. Addressing this clinical heterogeneity in OBCS is crucial due to the ever-increasing diversity and emergence of new surgical approaches68. This heterogeneity includes a wide range of factors such as tumor grades, breast sizes69, tumor locations, and the types of surgeries performed. For example, higher-grade tumors may necessitate more extensive tissue removal, impacting the complexity of the reconstruction required. Breast size and the location of the tumor can affect both the feasibility and the aesthetic outcomes of different surgical approaches70. The type of surgery performed is another variable, ranging from traditional lumpectomies to more advanced oncoplastic techniques71. For instance, larger tumors or tumors located in challenging positions may require more sophisticated oncoplastic techniques to achieve satisfactory results.

Additionally, the experience and expertise of surgeons72 and the capabilities of different medical centers play a significant role in outcomes73. Variability in surgeon expertise, learning curves, and institutional capabilities likely contributes to the heterogeneity observed in complication and satisfaction outcomes across studies. Centers with established oncoplastic programs and higher surgical volumes may achieve more consistent aesthetic and oncological results, while less experienced teams could encounter higher complication rates, particularly in technically demanding volume replacement procedures. Recognizing the role of surgical experience is essential when interpreting outcome variability and in developing training strategies to standardize oncoplastic practice.

In two studies31,52 markedly elevated dissatisfaction rate compared to other studies analyzed was observed. In the Ogawa et al.52, the cosmetic outcomes were evaluated using photographs 1 year post-operation, and a supraclavicularly extended glandular flap was used. Cosmetic results remained stable for patients with small breasts after 1 year. In the study of Essa et al.27, the limitation is the relatively small patient number and the localization of breast cancer (central), as well as the short duration of the follow-up period. In the case of centrally based tumors, the removal of the nipple-areola complex is unavoidable and thus can lead to more unfavorable aesthetic results for the patient.

Both VD and VR techniques are associated with comparable effectiveness in minimizing tumor recurrence and the incidence of positive margins. Comparable outcomes have also been reported in other breast cancer settings, including after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, where volume displacement and replacement approaches demonstrated similar oncological safety and patient satisfaction results74. Factors such as tumor biology, patient demographics, and variations in surgical expertise can influence oncological outcomes. For instance, larger tumors or those with more aggressive characteristics may pose a greater challenge in achieving clear margins75, regardless of the oncoplastic technique used. Oncological safety is a critical concern in breast-conserving surgery, as the primary goal is to remove all cancerous tissue while preserving as much healthy breast tissue as possible.

In breast surgery, hematoma development76 is a frequent postoperative complication that significantly impacts patient morbidity77. The slightly higher incidence of fat necrosis observed in VR procedures may be related to technical factors such as limited flap vascularity, increased ischemia time, or variations in flap thickness. These mechanisms could explain minor differences in complication rates between VR and VD procedures, though most cases were self-limiting and did not compromise oncologic or cosmetic outcomes. While seroma formation was excluded from the pooled analysis due to inconsistent reporting, it is worth noting that flap harvesting can predispose to seroma development, reflecting the increased surgical complexity of VR techniques.Although the subgroup differences in seroma formation were not statistically significant in our findings, the clinical relevance is notable. The nearly twofold higher incidence of seroma in the VR group suggests a need for careful consideration when selecting surgical techniques. However, the above-mentioned confounder limits the interpretation because more experienced surgeons are likely to have refined their techniques to minimize complications78, patient-specific factors such as age, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, and pre-existing medical conditions (e.g., diabetes) can influence wound healing79 and seroma formation. Furthermore, the tumor’s characteristics, the placement, duration, and management of surgical drains80, the use of neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapies81, and the presence of comorbid factors. Enhanced surgical techniques, postoperative care protocols, and monitoring may help further.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, there has been no prior meta-analysis or direct or indirect comparison between VR and VD techniques in breast-conserving surgery. Secondly, we included a wide array of surgical techniques within both the VR and VD subgroups, Making these findings highly relevant and applicable to contemporary surgical settings. Furthermore, our study design was comprehensive and grounded in a rigorous methodology with preregistered protocol.

Regarding the limitations, there is a limited extent of available data, particularly when considering the high clinical heterogeneity of OBCS patients, Moreover, the studies lack standardized parameters to measure objective patient satisfaction, and also there is an absence of universally accepted tools for its measurement, which limits the interpretability of this data. Additionally, the lack of direct comparison between VR and VD prevents us from conducting pairwise analysis, thereby limiting the current level of evidence. In the field of OBCS, achieving a higher level of evidence through RCTs is needed. However, the diverse characteristics of patients and tumors, along with varying patient needs, expectations, and preferences, make randomization impractical or impossible. Follow-up duration varied substantially among the included studies, as shown in the Basic Characteristics Table. Although recurrence and margin status were defined consistently across studies, this variability in follow-up limits the ability to draw definitive conclusions about long-term oncological equivalence.

Clinical implication and research implication

Due to high satisfaction rates across all methods, the choice of technique may be best guided by the patient’s specific anatomy, the tumor’s characteristics, and the surgeon’s expertise. The study findings contribute to the ongoing medical education82 of surgeons and plastic surgeons performing OBCS. The research outcomes highlight the importance of surgeon experience and medical center capabilities, which can be integrated into training programs to improve surgical outcomes. This can drive continuous learning and standardization of best practices, enhancing the quality of oncoplastic breast surgery. Lastly, these results empower patients through education about available techniques, associated satisfaction rates, potential complications and re-excision, and the importance of individualized treatment planning. This leads to an informed decision-making process which enables patients to participate actively in their care83.

The field of OBCS requires more standardized definitions and outcome metrics, acknowledging that the satisfaction of the partner is also crucial because it affects the patient’s emotional well-being and relationship quality, not solely aesthetic satisfaction. The current reporting standard of OBCS outcome measurements remains largely subjective84, making comparison difficult. The researcher should embrace more objective tools, such as the BREAST-Q questionnaire79, and focus on more specific domains, including the physical, psychological, and sexual aspects of women’s well-being after OBCS.

Conclusion

Volume displacement and replacement techniques are equally safe regarding oncological safety parameters and complication rates with comparable satisfaction rates. Careful planning is indispensable, with due consideration given to each patient’s anatomy and desired outcome before selecting the optimal surgical technique or combination thereof.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article.

References

Arnold, M. et al. Current and future burden of breast cancer: Global statistics for 2020 and 2040. Breast. 66, 15–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2022.08.010 (2022).

Heil, J. et al. Eliminating the breast cancer surgery paradigm after neoadjuvant systemic therapy: Current evidence and future challenges. Ann. Oncol. 31(1), 61–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2019.10.012 (2020).

Colby, D. A. & Shifren, K. Optimism, mental health, and quality of life: A study among breast cancer patients. Psychol. Health Med. 18(1), 10–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2012.686619 (2013).

Torras, I., Cebrecos, I., Castillo, H. & Mension, E. Evolution of breast conserving surgery—Current implementation of oncoplastic techniques in breast conserving surgery: A literature review. Gland Surg. 13(3), 412–425 (2024).

Chand, N. D. et al. Patient-reported outcomes are better after oncoplastic breast conservation than after mastectomy and autologous reconstruction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open. 5(7), e1419. https://doi.org/10.1097/gox.0000000000001419 (2017).

Chakravorty, A. et al. How safe is oncoplastic breast conservation?: Comparative analysis with standard breast conserving surgery. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. (EJSO) 38(5), 395–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2012.02.186 (2012).

Crown, A. et al. Oncoplastic breast conserving surgery is associated with a lower rate of surgical site complications compared to standard breast conserving surgery. Am. J. Surg. 217(1), 138–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2018.06.014 (2019).

Chu, C. K., Hanson, S. E., Hwang, R. F. & Wu, L. C. Oncoplastic partial breast reconstruction: concepts and techniques. Gland Surg. 10(1), 398–410. https://doi.org/10.21037/gs-20-380 (2021).

Yang, J. D. et al. Surgical techniques for personalized oncoplastic surgery in breast cancer patients with small- to moderate-sized breasts (part 2): Volume replacement. J. Breast Cancer. 15(1), 7–14. https://doi.org/10.4048/jbc.2012.15.1.7 (2012).

Mansell, J. et al. Oncoplastic breast conservation surgery is oncologically safe when compared to wide local excision and mastectomy. Breast 32, 179–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2017.02.006 (2017).

Higgins, J., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119536604 (2019).

Page, M. J. et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71 (2021).

citationchaser: An R package for forward and backward citations chasing in academic searching. Version 0.0.3. 2021. https://github.com/nealhaddaway/citationchaser.

Gotschall, T. Resource review: EndNote 21 desktop version. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 111(4), 852–853. https://doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2023.1803 (2023).

Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z. & Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 5(1), 210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 (2016).

Clough, K. B., Kaufman, G. J., Nos, C., Buccimazza, I. & Sarfati, I. M. Improving breast cancer surgery: A classification and quadrant per quadrant atlas for oncoplastic surgery. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 17(5), 1375–1391. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-009-0792-y (2010).

Slim, K. et al. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): Development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J. Surg. 73(9), 712–716. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1445-2197.2003.02748.x (2003).

Schünemann, H. B. J., Guyatt, G. & Oxman, A. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. 2013;

Abdelrahman, E. M. et al. Oncoplastic volume replacement for breast cancer: Latissimus Dorsi flap versus thoracodorsal artery perforator flap. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open. 7(10), e2476. https://doi.org/10.1097/gox.0000000000002476 (2019).

Adimulam, G. et al. Assessment of cosmetic outcome of oncoplastic breast conservation surgery in women with early breast cancer: A prospective cohort study. Indian J. Cancer. 51(1), 58–62. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-509x.134629 (2014).

Agrawal, A. et al. ‘PartBreCon’ study. A UK multicentre retrospective cohort study to assess outcomes following PARTial BREast reCONstruction with chest wall perforator flaps. Breast. 2023–10(71), 82–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2023.07.007 (2023).

Almasad, J. K. & Salah, B. Breast reconstruction by local flaps after conserving surgery for breast cancer: An added asset to oncoplastic techniques. Breast J. 14(4), 340–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4741.2008.00595.x (2008).

Amin, A. A., Rifaat, M., Farahat, A. & Hashem, T. The role of thoracodorsal artery perforator flap in oncoplastic breast surgery. J. Egypt. Natl. Cancer Inst. 29(2), 83–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnci.2017.01.004 (2017).

Bramhall, R. J. et al. Central round block repair of large breast resection defects: Oncologic and aesthetic outcomes. Gland Surg. 6(6), 689–697. https://doi.org/10.21037/gs.2017.06.11 (2017).

Caziuc, A., Andras, D., Fagarasan, V. & Dindelegan, G. C. Feasibility of oncoplastic surgery in breast cancer patients with associated in situ carcinoma. J. Buon. 26(5), 1970–1974 (2021).

Clough, K. B. et al. Level 2 oncoplastic surgery for lower inner quadrant breast cancers: The LIQ-V mammoplasty. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 20(12), 3847–3854. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-013-3085-4 (2013).

Clough, K. B. et al. Long-term results after oncoplastic surgery for breast cancer: A 10-year follow-up. Ann. Surg. 268(1), 165–171. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0000000000002255 (2018).

Colombo, P. E. et al. Oncoplastic Resection of breast cancers located in the lower-inner or lower-outer quadrant with the modified McKissock mammaplasty technique. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2015–12(22), S486–S494. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-015-4727-5 (2015).

De Biasio, F. et al. A simple and effective technique of breast remodelling after conserving surgery for lower quadrants breast cancer. Aesthet. Plast. Surg. 40(6), 887–895. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-016-0709-7 (2016).

El-Marakby, H. H. & Kotb, M. H. Oncoplastic volume replacement with latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap in patients with large ptotic breasts. Is it feasible?. J. Egypt. Natl. Cancer Inst. 23(4), 163–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnci.2011.11.002 (2011).

Essa, M. S., Ahmad, K. S., Salama, A. M. F. & Zayed, M. E. Cosmetic and oncological outcome of different oncoplastic techniques in female patients with early central breast cancer. Int. J. Surg. Open 2021, 32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijso.2021.100336 (2021).

Fernando, H., Noelia, G., Maria, E. & Pedro, M. Centrally located breast carcinomas treated with central quadrantectomy and immediate nipple-areola reconstruction: a cohort study. Breast Cancer 30(4), 552–558. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12282-023-01445-6 (2023).

Gardfjell, A., Dahlbäck, C. & Åhsberg, K. Patient satisfaction after unilateral oncoplastic volume displacement surgery for breast cancer, evaluated with the BREAST-Q™. World J. Surg. Oncol. 17(1), 96. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-019-1640-6 (2019).

Hernanz, F. et al. Oncoplastic breast-conserving surgery: Analysis of quadrantectomy and immediate reconstruction with latissimus dorsi flap. World J. Surg. 31(10), 1934–1940. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-007-9196-y (2007).

Hernanz, F., Sánchez, S., Cerdeira, M. P. & Figuero, C. R. Long-term results of breast conservation and immediate volume replacement with myocutaneous latissimus dorsi flap. World J. Surg. Oncol. 9, 159. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7819-9-159 (2011).

Hirata, M. et al. Modification of oncoplastic breast surgery with immediate volume replacement using a thoracodorsal adipofascial flap. Breast Cancer. 29(3), 531–540. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12282-022-01331-7 (2022).

Huizum, M. A. V., Hage, J. J., Oldenburg, H. A. & Hoornweg, M. J. Internal mammary artery perforator flap for immediate volume replacement following wide local excision of breast cancer. Arch. Plast. Surg. 44(6), 502–508. https://doi.org/10.5999/aps.2016.00458 (2017).

Izumi, K. et al. Immediate reconstruction using free medial circumflex femoral artery perforator flaps after breast-conserving surgery. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 66(11), 1528–1533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2013.07.003 (2013).

Kang, M. J. et al. Surgical strategies for partial breast reconstruction in medial-located breast cancer: A 12-year experience. J. Breast Cancer. 26(1), 35–45. https://doi.org/10.4048/jbc.2023.26.e8 (2023).

Kelemen, P. et al. Comparison of clinicopathologic, cosmetic and quality of life outcomes in 700 oncoplastic and conventional breast-conserving surgery cases: A single-centre retrospective study. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 45(2), 118–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2018.09.006 (2019).

Kelemen, P. et al. Evaluation of the central pedicled, modified wise-pattern technique as a standard level II oncoplastic breast-conserving surgery: A retrospective clinicopathological study of 190 breast cancer patients. Breast J. 25(5), 922–926. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbj.13371 (2019).

Kim, J. B. et al. Utility of two surgical techniques using a lateral intercostal artery perforator flap after breast-conserving surgery: A single-center retrospective study. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 143(3), 477e–487e. https://doi.org/10.1097/prs.0000000000005374 (2019).

Kim, S., Lee, S., Lee, H. & Lee, J. The safety and cosmetic effect of immediate latissimus dorsi flap reconstruction after breast conserving surgery. J. Breast Cancer. 12(3), 186–192 (2009).

Lee, J., Bae, Y. & Audretsch, W. Combination of two local flaps for large defects after breast conserving surgery. Breast. 21(2), 194–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2011.09.011 (2012).

Lee, S., Lee, J., Jung, Y. & Bae, Y. Oncoplastic surgery for inner quadrant breast cancer: Fish-hook incision rotation flap. ANZ J. Surg. 87(10), E129–E133. https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.13336 (2017).

Lee, J. et al. Oncologic outcomes of volume replacement technique after partial mastectomy for breast cancer: A single center analysis. Surg. Oncol. 24(1), 35–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suronc.2014.12.001 (2015).

Lee, J. W., Kim, M. C., Park, H. Y. & Yang, J. D. Oncoplastic volume replacement techniques according to the excised volume and tumor location in small- to moderate-sized breasts. Gland Surg. 3(1), 14–21. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2227-684X.2014.02.02 (2014).

Mericli, A. F. et al. The latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap is a safe and effective method of partial breast reconstruction in the setting of breast-conserving therapy. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 143(5), 927e–935e. https://doi.org/10.1097/prs.0000000000005577 (2019).

Ng, E. E., French, J., Hsu, J. & Elder, E. E. Treatment of inferior pole breast cancer with the oncoplastic ‘Crescent’ technique: The Westmead experience. ANZ J. Surg. 86(1), 88–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.13268 (2016).

Nguyen-Sträuli, B. D. et al. Single-incision for breast-conserving surgery through round block technique. Surg. Oncol. 44, 101847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suronc.2022.101847 (2022).

Noguchi, M. et al. Wide resection with latissimus dorsi muscle transposition in breast conserving surgery. Surg. Oncol. 1(3), 231–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/0960-7404(92)90069-w (1992).

Ogawa, T., Hanamura, N., Yamashita, M., Kimura, H. & Kashikura, Y. Breast-volume displacement using an extended glandular flap for small dense breasts. Plast. Surg. Int. 2011(2011), 359842. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/359842 (2011).

Orabi, A., Youssef, M. M. G., Manie, T. M., Shaalan, M. & Hashem, T. Lateral chest wall perforator flaps in partial breast reconstruction. J. Egypt. Natl. Cancer Inst. 34(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43046-021-00100-5 (2022).

Orsaria, P. et al. Subaxillary replacement flap compared with the round block displacement technique in oncoplastic breast conserving surgery: Functional outcomes of a feasible one stage reconstruction. Curr. Oncol. 29(12), 9377–9390. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29120736 (2022).

Rainsbury, R. M. & Paramanathan, N. Recent progress with breast-conserving volume replacement using latissimus dorsi miniflaps in UK patients. Breast Cancer. 5(2), 139–147. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02966686 (1998).

Roshdy, S. et al. Safety and esthetic outcomes of therapeutic mammoplasty using medial pedicle for early breast cancer. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press). 2015(7), 173–178. https://doi.org/10.2147/bctt.S83725 (2015).

Shen, M. et al. Partial breast reconstruction of 30 cases with peri-mammary artery perforator flaps. BMC Surg. 23(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-023-01937-4 (2023).

Soumian, S. et al. Chest wall perforator flaps for partial breast reconstruction: Surgical outcomes from a multicenter study. Arch. Plast. Surg. 47(2), 153–159. https://doi.org/10.5999/aps.2019.01186 (2020).

Sparavigna, M. et al. Oncoplastic level II volume displacement surgery for breast cancer: Oncological and aesthetic outcomes. Updates Surg. 75(5), 1289–1296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-023-01472-0 (2023).

Stocco, C. et al. Central mound technique in oncoplastic surgery: A valuable technique to save your bacon. Clin. Breast Cancer. 23(3), e77–e84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clbc.2023.01.004 (2023).

Yang, J. D. et al. Usefulness of oncoplastic volume replacement techniques after breast conserving surgery in small to moderate-sized breasts. Arch. Plast. Surg. 39(5), 489–96. https://doi.org/10.5999/aps.2012.39.5.489 (2012).

Youssif, S. et al. Pedicled local flaps: a reliable reconstructive tool for partial breast defects. Gland Surg. 8(5), 527–536. https://doi.org/10.21037/gs.2019.09.06 (2019).

Zaha, H. Oncoplastic volume replacement technique for the upper inner quadrant using the omental flap. Gland Surg. 4(3), 263–269. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2227-684X.2015.01.08 (2015).

Zaha, H. et al. Free omental flap for partial breast reconstruction after breast-conserving surgery. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 129(3), 583–587. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182402cc6 (2012).

Pilewskie, M. & Morrow, M. Margins in breast cancer: How much is enough?. Cancer 124(7), 1335–1341. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.31221 (2018).

Millen, J. C. et al. Simultaneous symmetry procedure in patients undergoing oncoplastic breast-conserving surgery: An evaluation of patient desire and revision rates. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 30(10), 6135–6139. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-023-13893-7 (2023).

Vrieling, C. et al. The influence of patient, tumor and treatment factors on the cosmetic results after breast-conserving therapy in the EORTC ‘boost vs. no boost’ trial. Radiother. Oncol. 55(3), 219–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-8140(00)00210-3 (2000).

Karadeniz, C. G. Innovative standards in oncoplastic breast conserving surgery: From radical mastectomy to extreme oncoplasty. Breast Care. 16(6), 559–573. https://doi.org/10.1159/000518992 (2021).

Savioli, F. et al. Extreme oncoplasty: Breast conservation in patients with large, multifocal, and multicentric breast cancer. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press). 13, 353–359. https://doi.org/10.2147/bctt.S296242 (2021).

Hiotis, K. et al. The importance of location in determining breast conservation rates. Am. J. Surg. 190(1), 18–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2004.12.002 (2005).

Mohamedahmed, A. Y. Y. et al. Comparison of surgical and oncological outcomes between oncoplastic breast-conserving surgery versus conventional breast-conserving surgery for treatment of breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 31 studies. Surg. Oncol. 42, 101779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suronc.2022.101779 (2022).

de Oliveira-Junior, I. et al. Oncoplastic surgery: Does patient and medical specialty influences the evaluation of cosmetic results?. Clin. Breast Cancer. 21(3), 247–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clbc.2020.09.012 (2021).

Hughes, L., Hamm, J., McGahan, C. & Baliski, C. Surgeon volume, patient age, and tumor-related factors influence the need for re-excision after breast-conserving surgery. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 23(5), 656–664. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-016-5602-8 (2016).

Tinterri, C. et al. De-escalation surgery in cT3-4 breast cancer patients after neoadjuvant therapy: Predictors of breast conservation and comparison of long-term oncological outcomes with mastectomy. Cancers (Basel). https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16061169 (2024).

Ananthakrishnan, P., Balci, F. L. & Crowe, J. P. Optimizing surgical margins in breast conservation. Int. J. Surg. Oncol. 2012, 585670. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/585670 (2012).

Unger, J. et al. Potential risk factors influencing the formation of postoperative seroma after breast surgery—A prospective study. Anticancer Res. 41(2), 859–867. https://doi.org/10.21873/anticanres.14838 (2021).

Turner, H. E. J., Benson, J. R. & Winters, Z. E. Techniques in the prevention and management of seromas after breast surgery. Future Oncol. 10(6), 1049–1063. https://doi.org/10.2217/fon.13.257 (2014).

Franceschini, G. Performance of standardized tasks and evidence-based surgery may increase the chance of success in breast conserving treatment. Gland Surg. 9(4), 1069–1071. https://doi.org/10.21037/gs-20-523 (2020).

Burgess, J. L., Wyant, W. A., Abdo Abujamra, B., Kirsner, R. S. & Jozic, I. Diabetic wound-healing science. Medicina 57(10), 1072 (2021).

Papanikolaou, A. et al. Management of postoperative seroma: Recommendations based on a 12-year retrospective study. J. Clin. Med. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11175062 (2022).

Sutton, T. L., Johnson, N., Schlitt, A., Gardiner, S. K. & Garreau, J. R. Surgical timing following neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer affects postoperative complication rates. Am. J. Surg. 219(5), 741–745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.02.061 (2020).

Hegyi, P., Erőss, B., Izbéki, F., Párniczky, A. & Szentesi, A. Accelerating the translational medicine cycle: The Academia Europaea pilot. Nat. Med. 27(8), 1317–1319. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01458-8 (2021).

Hegyi, P. et al. Academia Europaea position paper on translational medicine: The cycle model for translating scientific results into community benefits. J. Clin. Med. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9051532 (2020).

Valderas, J. M. et al. The impact of measuring patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice: A systematic review of the literature. Qual. Life Res. 17(2), 179–193. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-007-9295-0 (2008).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LENy: conceptualization, writing, investigation, title-abstract-full text selection, data extraction; ACL: investigation, title-abstract-full text selection, data extraction; JH: writing—review and editing, supervision; PH: supervision, conceptualization; PF: data curation, formal analysis; PNy: supervision, article drafting, conceptualization; NA: conceptualization, supervision; PR: conceptualization, supervision; ASz: article drafting, conceptualization, supervision; ZK: conceptualization, supervision, article drafting

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

No ethical approval was required for this systematic review with meta-analysis, as all data had already been published in peer-reviewed journals. No patients were involved in our study’s design, conduct, or interpretation.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nyirády, L.E., Czébely-Lénárt, A., Hoferica, J. et al. Evaluating oncoplastic breast-conserving surgery: oncological safety, risks, and satisfaction—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 16, 444 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30062-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30062-w