Abstract

The study of deep geostress and stress disturbance patterns near faults is critical for ensuring the safety of ultradeep wells, optimizing the effect of fracturing stimulation and accurately predicting “engineering sweet spots”. As oil and gas exploration has expanded to deeper and more complex tectonic areas, understanding the problem of fault-stress perturbation patterns under different stress backgrounds has become very urgent. In this study, to address the scientific problem in which the geostress perturbation pattern of deep (> 4500 m) faults is unclear, the Kelasu tectonic zone in the Kuqa depression was taken as the research object, and well logging data, seismic data and geomechanical modeling methods were used to systematically reveal the quantitative influence of the fault dip angle on in situ stress. The quantitative effects of the fault dip angle on the geostress under different stress types were investigated. The image logging data were used to identify wellbore breakouts and induced fractures, and the current geostress direction was confirmed to be nearly N‒S. A geological model of reverse faults with different dip angles was constructed on the basis of equilibrium section technology. The finite element numerical simulation method was used to analyze the relationship between the fault dip angle and geostress under three stress mechanisms: normal faulting, stress conversion and strike-slip faulting. The results show that in the normal fault stress field, the horizontal maximum and minimum principal stresses both decrease with increasing fault dip angle. Near the stress transformation zone, the principal stress increases slightly with increasing dip angle, but the control by faults weakens. In the strike-slip stress field, both increase significantly with increasing dip angle. In addition, the fault dip angle affects the distribution pattern of shear stress: the shear stress of low-angle faults has a wider range, whereas that of high-angle faults has stronger stress concentrations. This study has important guiding significance for geostress prediction, drilling trajectory optimization and fracturing design of deep reservoirs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The study of geostress in deep layers (burial depth > 4500 m) is the cornerstone of oil and gas exploration and development. The goal of this study is to determine the distribution pattern of the geostress field under ultrahigh-temperature, ultrahigh-pressure and strong-compression environments and its effects on reservoir physical properties and engineering safety1,2,3. At present, the study of geostress is carried out mainly through experimental simulations, well logging evaluations and numerical simulations4,5,6,7. In terms of experimental simulations, the magnitude of the principal stress in different directions can be revealed through differential strain experiments and Kaiser effect tests, which, together with the paleomagnetic orientation of the core, can be used to determine the direction of the present geostress4,8. In terms of well logging evaluation, the quantitative calculation of the magnitude and direction of geostress is realized through the combination of image logging (such as identification of induced fractures and borehole wall caving) with array acoustic data; thus, the coupling of stress around the wellbore on the coupling of matrix pores and fracture development can be revealed9,10. Recent progress in stress field simulation has focused on three main aspects. (1) Breakthrough in the fine characterization of complex geological structures: In view of the influence of the anisotropy of layered rock masses and the influence of weak interlayers, a secondary inversion analysis method has been developed11,12. In this method, the large-scale initial stress field is inverted on the basis of the stratum denudation simulation for the first time, and then the tectonic movement through effective nodal force loading is simulated to invert the local stress field of the layered rock mass for the second time. 3D geological structure–geostress integrated modeling technology integrates multisource heterogeneous data (such as experimental, borehole, and geophysical prospecting data) to achieve seamless integration of structural models and mechanical properties and supports finite element subsection and geostress calculations13,14. (2) Multiscale coupling modeling is combined with physical simulation, and numerical simulation methods are being developed in the direction of multifield coupling: the finite element method (FEM) outperforms tectonic stress field simulation, the finite difference method (FDM) optimizes seismic wave propagation calculations, and the boundary element method (BEM) effectively addresses the problems of fault mechanics and fluid flow15,16,17. (3) Multisource data fusion and the application of intelligent algorithms, deep learning and generative adversarial networks (GANs) significantly improve the accuracy and computational efficiency of geostress prediction18,19.

At present, the importance of geostress for oil and gas exploration and development is prominent in two aspects: (1) Reservoir evaluation and development optimization: The geostress field controls the distribution of high-quality tight sandstone reservoirs, and fracture development in the low horizontal stress difference area increases porosity. It is a key indicator for “sweet spot” prediction; at the same time, the direction of geostress constrains the propagation path of hydraulic fractures, affecting the design of fracturing programs for ultradeep wells20,21,22. (2) Improving project safety and benefits: Geostress heterogeneity leads to high wall instability risk. Therefore, well structures should be optimized on the basis of rock mechanics parameter profiles and four pressure profiles; deep geostress dynamic models also support good pattern deployment and storage conditions23,24. The economics of layer stimulation have promoted the efficient development of ultradeep resources with depths of up to 8,000 m in the Tarim Oilfield. In summary, deep geostress studies constitute the core technology for overcoming the bottleneck of ultradeep reservoir development of high stress, high temperature, high pressure, and low permeability and for providing an integrated geological engineering solution for deep energy development.

Accurately describing the controlling role of faults on the present geostress is the core of optimizing oil and gas reservoir exploration and development. This method is related to trap evaluation, fracturing stimulation, drilling safety and development strategy formulation25,26. Overcoming the problem of unclear fault‒stress interaction patterns in the context of different stress types is key for achieving efficient development and risk prevention and control. Under different regional stress types (compression/tension/strike-slip), a universal model has not been established for the mode of geostress disturbance caused by faults. In this study, the magnitude and direction of geostress in the study area were clarified on the basis of well logging data; finite element models were created through tectonic interpretation of seismic data; models with different dip angles were created according to the formation and evolution process of thrust faults; and different boundary stress loads were applied to simulate different stresses. Under these conditions, the influence pattern of the fault on stress. The research results in this paper have application value for determining stress distribution patterns near deep faults, designing drilling trajectories and evaluating engineering sweet spots.

Geological overview

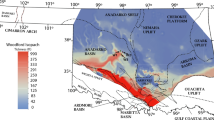

The Kelasu tectonic zone of the Kuqa depression is located in the transition zone between the Kuqa depression and the South Tianshan Basin in the Tarim Basin in western China (Fig. 1), and it has superior petroleum–geological conditions. The proven natural gas resources in this tectonic belt exceed one trillion cubic meters, and the burial depth of natural gas generally exceeds 6,500 m, making it a typical ultradeep, overpressure, and high-temperature gas reservoir. Since the discovery of the famous Keshen 2 gas field in 1998, exploration work has continued. In 2008, Well Keshen 2 made a major breakthrough in the Cretaceous Bashjiqike Formation, producing a high-yield industrial gas stream of 40 × 104 m3 per day. To date, more than 30 oil and gas reservoirs have been discovered in this area, making it the main natural gas-producing area in the Tarim Basin27,28. Exploration practices reveal that the distribution of high-quality hydrocarbon source rocks, the regionally thick gypsum‒salt caprock and the large subsalt tectonic traps are the key accumulation conditions for the formation of large gas fields in this area29,30.

Geographical location, landform and tectonic unit division of the Kuqa Depression31: (A) geographical location of the Tarim Basin; (B) geographical location of the Kuqa Depression; (C) remote sensing satellite images of the Kuqa Depression; (D) division of structural units in the Kuqa Depression. (The image are generated by CorelDRAW Graphics Suite 2024, version: CorelDRAW 2024 (v24.0.0.301), URL link: https://www.coreldraw.com).

The tectonic deformation of the Kelasu tectonic zone is characterized by significant differences in layering. The regional tectonic stress field was dominated by near-north horizontal compression, and the principal compressive stress axis was nearly north‒south (small dip angle), indicating that the stress state was mainly compressive30,31. Actual geostress data reveal that the maximum horizontal stress intensity of the piedmont thrust zone (e.g., Keshen Block 8) reaches 2.6 MPa/100 m, the horizontal minimum stress is 2.15 MPa/100 m, and the vertical stress is 2.35 MPa/100 m, which is typically greater than 2.15 MPa/100 m. A high-pressure system (formation pressure 122 MPa, temperature 175 °C) is used. This strong compressional environment led to reverse faulting earthquakes as the main mechanism, with focal depths of 10–25 km (approximately 11 km in the Kuqa depression area), reflecting deep brittle deformation.

The main reservoir of the Kelasu tectonic zone is the clastic rock of the Cretaceous Bashijiqike Formation (Fig. 2). Its petrological characteristics are as follows: low compositional maturity, medium to low structural maturity, moderate to good sorting properties, and subangular to subround grinding. The reservoir space is dominated by secondary pores, and primary pores also make certain contributions. Reservoirs have experienced various diagenetic transformations, such as compaction, cementation, corrosion and fracture32,33. Compaction and cementation are the main causes of the reduction in primary pores, whereas corrosion (especially the dissolution of carbonate cement, feldspar grains and cuttings) and fractures generated by tectonic rupture significantly increase porosity. The hanging wall of the fault zone experienced supergene corrosion and developed dissolution pores; owing to the greater burial depth, the reservoirs of the footwall were denser, but fractures improved their physical properties. In general, this reservoir has low porosity and low permeability characteristics, but the development of fractures can still achieve high production in some intervals34,35. Abnormally high pressure, hydrocarbon charging and thick gypsum‒salt caprock were key factors in the preservation of deep reservoir pores36.

Comprehensive column diagram of the Kuqa Depression27.

Data and methods

Method for determining the magnitude and direction of geostress at the well point

The determination of the geostress field is a comprehensive interpretation process that includes multidisciplinary research and multi-information fusion. The core idea is to use direct or indirect field survey data from drilling, well logging, core testing and fracturing construction to establish and calibrate the geostress model and finally obtain accurate geostress parameters. In this study, the magnitude and direction of geostress are determined mainly from well logging data. The magnitude of stress is mainly determined through dipole acoustic logging calculations37.

The principle that wellbore breakout determines the direction of geostress is based on the shear failure mechanism of the wellbore. After drilling, the stresses around the wellbore wall are redistributed, with the highest degree of stress concentration occurring in the direction of the horizontal minimum principal stress (σhmin). When the tangential stress exceeds the shear strength of the rock, shear fracture occurs, and the wellbore wall cavitates. The discrimination criterion is that a pair of dark (low-resistivity or low-wave velocity) vertical bands with a 180° symmetrical distribution can be seen on the downhole acoustic–electric imaging logging map. The direction of this paragenesis line indicates the orientation of the σhmin direction, and the vertical direction is the horizontal maximum principal stress (σHmax)38,39.

The principle of using induced fractures to determine the direction of geostress is based on the tensile fracture mechanism of the wellbore. When the pressure of the drilling fluid column is too high such that the circumferential tensile stress on the borehole wall rock exceeds its tensile strength, parallel tension fractures are generated. These kinds of cracks always open in the direction of σHmax because the rock in this direction more easily propagates. On the imaging logging diagrams, the induced fractures manifested as a pair of thin straight, straight, high-conductivity (dark color) vertical lines that were distributed 180° symmetrically. The direction of this line directly indicates the direction of σHmax40,41.

Construction methods for fault geological models with different dip angles

The goal of constructing geological models of thrust faults with different dip angles on the basis of balanced section technology is to follow the basic principle that “when the deformed stratum is restored to the undeformed state, the geometry, length, and area must remain reasonable and conserved.”42 Construction methods usually follow a systematic process. First, an unbalanced initial geological section is created on the basis of surface geology, seismic exploration or drilling data; then, on the basis of the regional tectonic background, one or more detachment layers are selected as the control baseline for changes in the fault dip angle. Under the constraint of a given shortening, by changing the occurrence (e.g., fault slope angle) of the fault on or between the detachment layer (shovel reverse fault with a steep upper part and gentler lower part), a series of different dip fault models can be systematically generated. Subsequent algorithms such as oblique shear or flexural slip were used for stratum backstripping and profile restoration, and the model was repeatedly adjusted until it reached geometric equilibrium42. Eventually, by forward modeling, the balanced model was deformed to the present state, and a geological model of thrust faults with different dip angles that was in line with the geological reality and was mechanically rational was obtained. This method ensures the reliability of the model in terms of geometry and kinematics and provides a basis for geomechanical modeling with different dip angles.

Methods for geomechanical modeling and stress field numerical simulation of faults with different dip angles

The geomechanical modeling and stress field numerical simulation in this study were conducted via the software ANSYS. The overall workflow comprises four primary stages:

-

(1)

Geometric model creation and meshing: On the basis of the results of geological exploration, well logging, and seismic interpretation, especially balanced section technology, a geogeometric model including the target fault (set with different dip angles) and surrounding strata is constructed. A 3D geological structure model was created via professional software (such as Petrel, GOCAD, and MOVE) and imported into finite element software (such as ABAQUS, ANSYS, and FLAC3D) for meshing. The mesh needs to be locally refined in the fault zone and nearby area to ensure that the stress concentration and deformation characteristics can be accurately captured.

-

(2)

Rock mechanics parameter assignment and constitutive model selection: Accurate rock mechanics parameters, including the Young’s modulus, Poisson’s ratio and density, are assigned to each rock formation and fault zone material in the model. Fault zones are usually set as weak surface materials with significantly different characteristics from those of surrounding rocks. In accordance with the simulation purpose (such as elastic analysis or fracture simulation), an appropriate constitutive model (such as the linear elastic, elastic‒plastic, or Drucker‒Prager model) is selected for the bulk rock, and geomechanical models with different dip angles are created.

-

(3)

Boundary constraints and loading conditions: Boundary conditions consistent with the actual geological environment were imposed. Typically, a vertical displacement constraint is applied at the bottom of the model, and a horizontal tectonic stress or displacement constraint is applied at the side of the model to simulate the three-dimensional distribution of the stress field. The initial geostress field (including overburden pressure and the two horizontal principal stresses) is set by theoretical calculations (e.g., a vertical stress gradient based on density logging) or field measurement data (such as the magnitude and direction of geostress) to ensure that the model simulation is in an equilibrium true geostress state before the simulation starts.

-

(4)

Numerical solution and postprocessing analysis: The solver was run for numerical simulation. The pattern of stress near the fault is simulated by applying a tectonic load, and the stress‒strain response of the model is observed. After the calculation was complete, we conducted postprocessing analysis on the results, with a focus on the output and analysis of the entire model, especially the stress field (magnitude and direction) and strain field cloud images and data around the faults with different dip angles, thereby quantitatively evaluating the mechanical behavior of faults with different dip angles and their associated effects.

Results

Direction and magnitude of in situ stress

The in situ stress field of the deep tight sandstone reservoirs in the Kelasu tectonic belt is generally a strike-slip type (σHmax > σV > σhmin), and the direction of the σHmax is generally in the N‒S direction (Fig. 3) and, locally, in the NW or NE direction; at present, the in situ stress is high, the σhmin is generally greater than 130 MPa, the horizontal stress difference is mostly greater than 30 MPa, and the distribution is strongly heterogeneous (Fig. 4). Affected by strong and continuous tectonic compression and an extremely thick salt layer, the present geostress state of the Kuqa piedmont may have undergone four transformations in the vertical direction: from the reverse fault type to the strike-slip type, then to the normal fault type, and finally back to the current strike-slip type43. There is a normal fault-type stress field above the target layer. This complex stress environment, complex structure and lithology pose great challenges to borehole wall stability in drilling. Therefore, it is necessary to study the influence pattern of faults on stress under different types of stress.

shows the well logging data used to determine the direction of the present geostress: (A) Hole wall caving in the Dabei-XY8 well; (B) borehole wall caving in the Dabei-XY8 well; (C) image of the Dabei-XY8 well-induced fractures; (D) azimuth of the induced fractures in the Dabei-XY8 well. (The image are generated by Techlog 2019.2.1, version: Techlog 2019.2.1, URL link: https://www.software.slb.com/products/techlog).

Rock mechanics parametric model

Through well logging interpretation of rock mechanical parameters at the top of the salt, the rock mechanical parameters of different formations were clarified (Table 1). The Young’s modulus of the fault zone unit was set to 30% lower than that of the surrounding rock mass to simulate its “weakness” characteristics; its Poisson’s ratio was set to a relatively high value, greater than the Poisson’s ratio of the surrounding rock by 20%, to reflect its relatively small shear bearing capacity and deformability. This scheme is a numerical equivalent approximation, and its essence is to use a very low stiffness to simulate the mechanical behavior of a fault that is prone to deformation and slip under the action of stress.

Geomechanical models of faults with different dip angles

Using the seismic section of the study area together with the tectonic map of the Bozi-Dabei area, a geological model was created via ANSYS software via finite element geomechanical modeling, and the geological model was constructed via ANSYS software on the basis of uniaxial compression tests, triaxial compression tests and well logging data. On the basis of calculations, the rock mechanical parameters used in the finite element numerical simulation are determined and assigned to the geological model. The geological model is meshed using an appropriate element type and mesh edge length to form a mechanical model. The SOLID45 element type is most consistent with the mechanical properties of reservoir rocks44. The selection of the mesh side length depends on the specific situation. The mesh formed after division should not be too large or too small. If the value is too large, the calculation time of a single numerical simulation will be longer, and the improvement in simulation accuracy will not be greatly improved. If the value is too small, the numerical simulation results will be too rough, and the numerical simulation effect will be affected. Compared with nonfault areas, the width of fault zones is generally smaller; therefore, the mesh needs to be subdivided. In accordance with the above principles, the geological model was meshed, and a total of 269522 nodes and 889562 elements were identified.

On the basis of the geological data of the study area, the equilibrium section restoration principle was used to create geomechanical models with different dip angles (Fig. 5) to simulate the effects of fault occurrence on geostress. Through numerical simulation of the stress field, distribution diagrams of σhmin and σHmax and plane shear stress distribution diagrams of faults with different dip angles were constructed.

Geomechanical models of different occurrences created on the basis of the equilibrium section restoration principle: (A) high-angle fault model; (B) low-angle fault dip model. (The image are generated by ANSYS 2021 R1, version: ANSYS 2021 R1 (v21.1), URL link: https://www.ansys.com).

Discussion

Relationship between the fault dip angle and stress in a normal fault-type stress field

Comparing the magnitude of the principal stress in different directions, for the F1 fault, when the normal fault stress field is σV > σHmax > σhmin, from the distribution diagram of σhmin with different fault dip angles (Fig. 6), the stress values under σhmin and σHmax of the fault with a low dip angle are greater (Fig. 6A and C), the overburden in the upper part is lower, the stress value of the imbricate fan is in the middle, and the overburden stress value is higher in the western periphery. The σhmin distribution diagrams near the high-dip faults (Fig. 6B and D) reveal that the σhmin is also higher than the lower σhmin, the overburden σhmin is low, and the minimum principal stress of the imbricate fan is low. The distribution patterns of σhmin and σHmax are similar. The σhmin is in the middle, and the stress of the overburden formation is locally high in the western region, which is consistent with the distribution trend of the σhmin on the low-dip faults.

(A) Distribution of σhmin near a low-angle fault; (B) distribution of σhmin near a high-angle fault; (C) distribution of σHmax near a low-angle fault; (D) σHmax near a high-angle fault. Principal stress distribution. (The image are generated by ANSYS 2021 R1, version: ANSYS 2021 R1 (v21.1), URL link: https://www.ansys.com).

The F1 fault is in a normal fault stress field environment. The σhmin and fault dip angle data are sorted to construct a scatter plot of the σhmin and fault dip angle. After fitting, the curve is y = -0.203x + 120.14; R2 = 0.918. σhmin decreases with increasing fault dip angle (Fig. 7A). The σHmax and fault dip data were collated, and scatter plots of the σHmax and fault dip were constructed. After fitting, the curve is y = -0.339x + 151.29, and R2 = 0.964 (Fig. 7B). σHmax decreases with increasing fault dip, and the fitting coefficient between the two is high, indicating that in the deep normal fault-type stress field, faults significantly control the horizontal stress.

Relationship between the fault dip angle and stress in the stress transformation zone

Numerical simulation reveals that the F2 fault is in the stress transformation zone (σHmax ≈ σV > σhmin). In the stress conversion zone, the distribution diagram of σhmin at different fault dip angles (Fig. 6) reveals that the σhmin near the dip fault is greater, the upper overburden is lower, the stress value of the imbricate fan is in the middle, and the stress value of the overburden formation is locally greater in the west than in the periphery. The distribution diagram of σhmin near the high-dip fault reveals that σhmin is also relatively high in the lower part and that the σhmin value of the overburden is relatively low.

The σhmin and fault dip angle data were collated, and a scatter diagram of the σhmin and fault dip angle data was constructed. After fitting, the curve is y = 0.079x + 117.88, and R2 = 0.302. σhmin increases with increasing fault dip angle (Fig. 8A). The data for σHmax and the fault dip angle were collated, and a scatter diagram of σHmax and the fault dip angle was constructed. After fitting, the curve y = 0.021x + 137.26, and R2 = 0.148 was obtained. σHmax increases as the fault dip angle increases (Fig. 8B). The fitting coefficient between the two is low, indicating that in the deep transformation stress field, the control effect of faults on the horizontal stress is weak.

Relationship between the fault dip angle and stress in the strike-slip stress field

Numerical simulations reveal that the F3, F4 and F5 faults are in the strike-slip stress field (σHmax > σV > σhmin). In the strike-slip stress field, the σhmin distributions of faults with different dip angles (Fig. 6) reveal that the σhmin near the dip fault was greater in the lower part and that the upper overburden was lower. The data of the σhmin and fault dip angle of the F3 fault were sorted, and a scatter diagram of the σhmin and fault dip angle was constructed. After fitting, the fitting curves y = 0.262x + 123.73 and R2 = 0.881 were obtained. σhmin increased with increasing fault dip angle (Fig. 9A). By plotting the scatter plot of σHmax and the fault dip angle and fitting the curve y = 0.313x + 145.38, R2 = 0.976, σHmax increases with increasing fault dip angle (Fig. 9B).

The data of the σhmin and fault dip angle of the F4 fault were sorted, and a scatter plot of the σhmin and fault dip angle was constructed. After fitting, the fitting curve is y = 0.319x + 138.76, and R2 = 0.900 is obtained. σhmin increases with increasing fault dip angle (Fig. 10A). By plotting the scatter plot of σHmax and the fault dip angle and fitting the curve y = 0.402x + 161.80, R2 = 0.954, σHmax increases with increasing fault dip angle (Fig. 10B).

The data of the σhmin and fault dip angle of the F5 fault were collated, and a scatter plot of the σhmin and fault dip angle was constructed. After fitting, the fitting curve is y = 0.614x + 145.65, and R2 = 0.804 is obtained. σhmin increases with increasing fault dip angle (Fig. 11A). By plotting the scatter plot of σHmax and the fault dip angle and fitting the curve y = 0.609x + 173.22, R2 = 0.949, σHmax increases with increasing fault dip angle (Fig. 11B). The fitting coefficients between the stresses and the fault dip angles of the three faults are very high, indicating that in the deep strike-slip stress field, faults significantly control the horizontal stress.

Effects of the fault dip angle on the plane shear stress

The plane shear stress distribution diagram of the low-angle fault model and the high-angle plane shear stress distribution diagram of the high-angle fault model were obtained through numerical simulation of the stress field. The plane shear stress distribution map of the low-angle faults (Fig. 12A) reveals that the plane shear stress in the upper part of the fault is low and gradually increases at the periphery, with the eastern and western local plane shear stress values being the greatest. The plane shear stress distribution map of the high-angle faults (Fig. 12B) reveals that the plane shear stress in the upper part of the fault is low and gradually increases at the periphery, with the eastern and western local plane shear stress values being the greatest. A comparison of the plane shear stress of the low-angle fault and the plane shear stress of the high-angle fault reveals that the range of influence of the plane shear stress of the low-angle fault is greater, whereas the concentration of the plane shear stress of the high-angle fault is greater.

(A) Plane shear stress distribution near a low-angle fault; (B) plane shear stress distribution near a high-angle fault. (The image are generated by ANSYS 2021 R1, version: ANSYS 2021 R1 (v21.1), URL link: https://www.ansys.com).

Conclusion

-

(1)

This study constructed a geomechanical model of thrust faults with different dip angles by integrating well logging interpretations, seismic data, and balanced profile technology. The impact of fault occurrence on the distribution of deep geostress under three typical stress mechanisms (normal fault type, stress conversion zone, and strike slip type) was systematically simulated. The numerical simulation results reveal that there is a clear coupling relationship between the fault dip angle and the geostress response and that the nature of this influence is significantly controlled by the regional stress type.

-

(2)

In the normal fault-type stress field (σV > σHmax > σhmin), both σHmax and σhmin decrease linearly as the fault dip angle increases, indicating that the high-angle fault is under tension. Under tension, it had a significant releasing effect on the stress. Near the stress transformation zone (σHmax ≈ σV > σhmin), the principal stress increases only slightly with increasing fault dip angle, and the goodness of fit is low (R2 < 0.35), indicating that the control effect of faults on geostress is significantly weakened in this environment. On the other hand, in the strike-slip stress field (σHmax > σV > σhmin), the principal stresses increase significantly with increasing fault dip angle, indicating that high-angle faults increase the stresses in the context of strike-slip motion. In addition, the fault dip angle affects the distribution pattern of shear stress: low-angle faults cause a wider range of shear stress, whereas high-angle faults increase the shear stress concentration.

-

(3)

This study provides a theoretical basis and numerical simulation support for the quantitative prediction of geostress fields near fault layers in ultradeep oil and gas reservoirs and has important guiding significance for well location deployment, drilling trajectory optimization and fracturing design. The results clearly indicate that the effects of fault occurrence on geostress distribution should be considered differently under different tectonic settings to improve the identification accuracy of engineering sweet spot identification and drilling safety.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Yu, G. et al. Variations and causes of in-situ stress orientations in the Dibei-Tuziluoke Gas Field in the Kuqa Foreland Basin, western China. Marine Petroleum Geology 158, 106528 (2023).

Wang, Song, et al. Comparison between double caliper, imaging logs, and array sonic log for determining the in-situ stress direction: A case study from the ultra-deep fractured tight sandstone reservoirs, the Cretaceous Bashijiqike Formation in Keshen8 region of Kuqa depression, Tarim Basin, China. Petroleum Science. (2022) 19 6: 2601–2617.

Xu, Ke. et al. Fracture effectiveness evaluation in ultra-deep reservoirs based on geomechanical method, Kuqa Depression, Tarim Basin, NW China. J. Petroleum Sci. Eng. 215, 110604 (2022).

Li, P. et al. Accurate stress measurement using hydraulic fracturing in deep low-permeability reservoirs: Challenges and research directions. Adv. Geo-Energy Res. 14(3), 165–169 (2024).

Chai, Y. & Yin, S. 3D displacement discontinuity analysis of in-situ stress perturbation near a weak faul. Adv. Geo-Energy Res. 5(3), 286–296 (2021).

Liu, J. et al. Asymmetric propagation mechanism of hydraulic fracture networks in continental reservoirs. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 135(3–4), 678–688 (2023).

Yang, Q. et al. Research on quantitative prediction method of structural fractures in metamorphic rock reservoirs. Sci. Reports 15(1), 28245 (2025).

Zhang, Jiaosheng, et al. The present-day in-situ stress field in Yanchang Formation Chang 8 reservoir of Jiyuan region: Characteristics and influencing factors. Geological Bulletin of China (2025): 1–11.

Faraji, M. et al. Breakouts derived from image logs aid the estimation of maximum horizontal stress: A case study from Perth Basin. Western Australia. Adv. Geo-Energy Res. 5(1), 8–24 (2021).

Xin, Yi. et al. Well Logging Evaluation of “Three Quality” of Jurassic Tight Gas Sandstone Reservoirs in Kuqa Depression. Earth Sci. 49(6), 2085–2102 (2024).

Cai, Z. et al. Quantitative Prediction of in situ Stress in Ultradeep Fracture-Cave Reservoirs and Its Applications. J. Earth Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12583-024-0001-8 (2025).

Liu, J. et al. Main controlling factors and prediction model of fracture scale in tight sandstone: insights from dynamic reservoir data and geomechanical model analysis. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 57(10), 8343–8362 (2024).

Yong, R. et al. Complex in situ stress states in a deep shale gas reservoir in the southern Sichuan Basin, China: From field stress measurements to in situ stress modeling. Marine Petroleum Geology 141, 105702 (2022).

Yang, L. et al. Model experimental study on the effects of in situ stresses on pre-splitting blasting damage and strain development. Int. J. Rock Mech. Mining Sci. 138, 104587 (2021).

Liu, J. et al. Quantitative multiparameter prediction of fault-related fractures: a case study of the second member of the Funing Formation in the Jinhu Sag. Subei Basin. Petroleum Science 15(3), 468–483 (2018).

Fan, Yong, et al. Influence of In-Situ Stress on Granite Fractures by Blasting: Insight from Circular Tunnel Experiment and Simulation. Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering (2025): 1–29.

Liu, J. G. et al. In situ stress field in the Athabasca oil sands deposits: Field measurement, stress-field modeling, and engineering implications. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 215, 110671 (2022).

Song, Z. et al. Nonlinear Intelligent Inversion Method and Practice for In-situ Stress in Stratified Rock Masses with Deep Valley. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 58(2), 1933–1955 (2025).

Chen, Z. et al. Intelligent identification of acoustic emission Kaiser effect points and its application in efficiently acquiring in-situ stress. Int. J. Minerals, Metallurgy and Mater. (2025): 1–12.

Abul Khair, H., Cooke, D. & Hand, M. The effect of present day in situ stresses and paleo-stresses on locating sweet spots in unconventional reservoirs, a case study from Moomba-Big Lake fields, Cooper Basin, South Australia. J. Petroleum Exploration Production Technol. 3(4), 207–221 (2013).

Sena, A. et al. Seismic reservoir characterization in resource shale plays: Stress analysis and sweet spot discrimination. Lead. Edge 30(7), 758–764 (2011).

Luo, A. et al. Experimental Study on the Influence of Water-rock Interaction on the Mechanical Characteristics and Creep Behavior of Shale. J. Geo-Energy Environ. 1(2), 61–69 (2025).

Li, J. et al. Three-Dimensional Multiparameter Modeling of Shale Reservoirs and Geostress Research. J. Energy Eng. 151(4), 04025034 (2025).

Chen, X. et al. Geo-mechanical model testing for stability of underground gas storage in halite during the operational period. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 49(7), 2795–2809 (2016).

Xu, K. et al. The characteristics of in-situ stress and its application in the fault-controlled fracture-vug reservoirs in the Fuman Oilfield Tarim Basin. Geol. Bull. China 44(2–3), 232–244 (2025).

Li, J. et al. Geological Characteristics and Three-Dimensional Development Potential of Deep Shale Gas in the Luzhou Area, Southern Sichuan Basin. China. J. Geo-Energy Environ. 1(1), 32–44 (2025).

Zhenping, Xu. et al. The Influence Lithologic Differences at Different Depths on the Segmentation between the Eastern and the Western zones of Kuqa Depression. Earth Sci. 49(8), 3029–3042 (2024).

Qinghua, W. et al. Multiple Décollement Model and Its Petroleum Geological Significance in Kelasu Subsalt Structural Belt. Kuqa Depression. Earth Sci. 50(1), 97–109 (2025).

He, Z. et al. Quantitative reconstruction of phase states and evolution of condensate and gas in the western Kelasu Thrust Belt, Kuqa Depression, Tarim Basin." Scientific Reports 15.1 (2025): 19305.

Zhang, R. et al. In situ stress and reservoir quality evaluation of Jurassic Ahe Formation in Kuqa depression of Tarim Basin, China. Petroleum Science and Technology (2025): 1–19.

Yang, K. et al. Influence of preexisting structures on salt structures in the Kuqa Depression, Tarim Basin, Western China: Insights from seismic data and numerical simulations. Basin Res. 36(1), e12850 (2024).

Wang, B. et al. Modelling of pore pressure evolution in a compressional tectonic setting: The Kuqa Depression, Tarim Basin, northwestern China. Marine Petroleum Geology. 146, 105936 (2022).

Wang, Q. et al. New fields and resource potential of tight sandstone oil and gas in Tarim Basin. Acta Petrolei Sinica 46(1), 89–103 (2025).

Haijun, Y. et al. Hydrocarbon charging periods and maturities in Bozi-Dabei area of Kuqa depression and their indications to the structural trap sequence. Acta Petrolei Sinica 45(10), 1480–1491 (2024).

Jin, L. et al. Genesis and logging evaluation of deep to ultra-deep high-quality clastic reservoirs: a case study of the Cretaceous Bashijiqike Formation in Kuqa depression. Acta Petrolei Sinica 44(4), 612–625 (2023).

Ren, G. et al. Quantitative Assessment of Shale Gas Preservation in the Longmaxi Formation: Insights from Shale Fluid Properties. J. Geo-Energy Environ. 1(1), 8–22 (2025).

Daines, S. R. Prediction of fracture pressures for wildcat wells. J. Petroleum Technol. 34(04), 863–872 (1982).

Zoback, M. D. et al. Well bore breakouts and in situ stress. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 90(B7), 5523–5530 (1985).

Vernik, L. & Zoback, M. D. Estimation of maximum horizontal principal stress magnitude from stress-induced well bore breakouts in the Cajon Pass scientific research borehole. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 97(B4), 5109–5119 (1992).

Li, Y. & Schmitt, D. R. Drilling-induced core fractures and in situ stress. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 103(B3), 5225–5239 (1998).

Liu, J. Evaluation method and application of fractures in tight sandstone reservoirs. Science Press:2025.

Fossen, Haakon. Structural geology. Cambridge university press: 2016.

Xu, Ke. Prediction of current in situ stress filed and its application of deeply buried tight sandstone reservoir: A case study of Keshen 10 gas reservoir in Kelasu structural belt, Tarim Basin. J. China Univ. Petroleum 49(4), 708–720 (2020).

Sun, Ke. Characterization of the length of structural fractures in low permeability reservoirs and its application:a case study of Longwangmiao Formation in MoxiGaoshiti areas. Sichuan Basin. Petrelum Geology Experiment 44(1), 160–169 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Science and Technology Major Project of China (2025ZD1401403), Tarim Oilfield Company R&D Center Technology Project "Research and Application of Exploration Geomechanics Technology" (YF202505) and the CUG Scholar Scientific Research Funds at China University of Geosciences (Wuhan) (No. 2022046).

Funding

National Science and Technology Major Project of China, 2025ZD1401403, Jingshou Liu; Tarim Oilfield Company R&D Center Technology Project "Research and Application of Exploration Geomechanics Technology", YF202505, Ke Xu; CUG Scholar Scientific Research Funds at China University of Geosciences (Wuhan), No. 2022046, Jingshou Liu.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Penglin Zheng: Resources, writing-review & editing, funding acquisition. Jingshou Liu: Writing-original draft, conceptualization, methodology, software, data curation, supervision, funding acquisition. Hui Zhang: Writing-review & editing, funding acquisition. Bohan Tian: Writing-original draft, methodology, validation, writing-review & editing. Ku Xu: Writing-review & editing, funding acquisition. Ziyi Li: Formal analysis, data curation. Jianli Qiang: Writing-review & editing, funding acquisition. Yang Luo: Writing-review & editing methodology. Yixiong Hu: Writing -Review & editing. Zhenyun Li: Writing-review & editing. Shujun Lai: Writing-review & editing, methodology. Qiuyu Chen: Writing -Review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, P., Liu, J., Zhang, H. et al. Quantitative analysis of the influence of faults on deep in situ stress under different stress types. Sci Rep 16, 572 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30140-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30140-z