Abstract

To study the initiation, propagation, and mechanical behaviour characteristics of fractures on the wall of a single hole during hydraulic fracturing for in-situ stress measurement, and to improve the accuracy of stress direction discrimination in hydraulic fracturing in-situ stress measurement. This paper adopts methods such as theoretical analysis, numerical simulation, and experimental research. On the basis of obtaining basic mechanical parameters through rock mechanics tests, and using the Weibull distribution to describe the inhomogeneity of rocks, a model based on COMSOL software is constructed. It studies the laws and influencing factors of fracture propagation on the borehole wall under different stress environments. The simulation results show that under different stress conditions, the initiation direction of fractures on the borehole wall is mainly parallel to the direction of the maximum principal stress and perpendicular to the direction of the minimum principal stress. At the same time, the propagation and closure of fractures are jointly controlled by the mechanical properties of rocks and the in-situ stress field. In addition, natural cracks have little impact on the propagation of fractures on the borehole wall, and the propagation of hydraulic fractures is not affected by natural cracks. This research achievement provides a reliable theoretical basis for accurately identifying the direction of underground stress, and has important value in guiding tunnel support design, preventing and controlling rockburst and other engineering practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

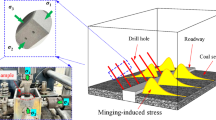

With the continuous increase of coal mining intensity, shallow coal resources are gradually depleted, and the mining depth continues to deepen. After entering the deep part, the displacement of the roof and floor continues to rise, and the rock mass in the surrounding area gradually peels off, and the floor rock layer shows plastic rheological characteristics1. The anisotropic characteristics of surrounding rock are becoming increasingly prominent, and the nonlinear deformation effects caused by tectonic stress fields are becoming increasingly prominent2. The above-mentioned unfavorable factors have become technical bottlenecks restricting the safe production of high stress coal mines. Therefore, in order to grasp the stress situation of deep surrounding rock, accurate measurement of geostress is particularly important. At present, coal mines commonly use single hole hydraulic fracturing method for stress testing. This method involves constructing a vertical hole upwards in the underground roadway, and then hydraulic fracturing is carried out outside the disturbance range of the roadway excavation (5–6 times the radius of the roadway). The direction of the principal stress perpendicular to the plane of the single hole is determined based on the direction of crack initiation.

However, due to the limitations of actual measurement work and the discreteness of data, a single measured value is difficult to fully reflect the actual situation of the research area. It is necessary to combine measured data with numerical analysis methods to study the initiation, propagation, and mechanical behavior of hydraulic fracturing cracks in the process of measuring geostress, in order to improve the accuracy of geostress measurement.

The hydraulic fracturing method was originally used to create artificial fractures to increase oil production. During this process, M.K. Hubbert and D.G. Wills discovered the relationship between hydraulic fracturing fractures and the stress of the original rock3. During the 4th ISRM Conference in 1978, the Haimson Fairhurst team constructed a complete theoretical framework for hydraulic fracturing based on the Biot theory of elasticity (pore elasticity coefficient α = 0.8), forming a complementary "dual track measurement system" to the core method. This technology combination is still the core method today4. Professor Liu Yunfang and others in China5 have revised and supplemented the theory of porous intersection three-dimensional hydraulic fracturing, further improving the theory of hydraulic fracturing. French scholars Cornet and Valette proposed the HTPF method for hydraulic fracturing measurement of primary fractures in boreholes6. Later, Liu Yunfang introduced the HTPF method to China7. Due to its high requirements for the form and state of fractures, this method has certain limitations in testing and is rarely used in domestic and foreign engineering projects. Von Schonfeldt and Fairhurst8 applied hydraulic fracturing method to measure the original rock stress of granite in a single rock layer in Minnesota, opening the door to hydraulic fracturing method for measuring ground stress. In 1980, the Earthquake Geology Brigade successfully tested hydraulic fracturing method in Yi County, Hebei Province9. Deng Guangzhe et al.10,11,12 considered the conditions of rock mass fissures, rock burial depth, stress conditions, rock joints, etc., combined with indoor and outdoor experiments, and studied the initiation pressure and expansion of cracks by injecting water into closed cracks. They obtained the relationship between the fracture pressure and the increase of pressure measurement coefficient, as well as the influence of water injection flow rate, water injection pressure, etc. on the extension of cracks and the conductivity of water in cracks under different stress conditions. Wang Rui et al.13 used Comsol fluid structure coupling simulation experimental software to calculate the pore wall surface pressure and crack propagation boundary conditions caused by high-pressure water flow in boreholes and cracks, verifying the interaction between the flow state of fracturing fluid and the surface tension of rock boreholes and cracks. Zhou Changbing et al.14 conducted hydraulic fracturing experiments on large samples of Lu gray granite with a diameter of 200 mm × 400 mm under high-temperature triaxial stress, and analyzed the characteristics of the hydraulic loading curve and the final morphology of the cracks in the experiment. Sun Zeliang et al.15 used RFPA2D Flow to simulate the propagation behavior of water pressure cracks at the initial layer, the maximum crack length along the layer, and the failure mode of water pressure cracks under different stress environments. The results showed that the stress environment had no effect on the propagation behavior of water pressure cracks at the initial layer16,17. Jin Yan et al.18 established a calculation model for the initiation pressure based on the stress state and the formation of natural cracks, and accurately predicted the initiation pressure and three types of initiation forms, namely tensile fracture, shear fracture, and solid fracture, through outdoor experiments. Liu Quansheng et al.19 used hydraulic fracturing and stress relief methods to study the non-uniformity and principal stress direction characteristics of deep geostress fields. Chen Weizhong et al.20predicted the compression deformation trend of soft rock tunnels by combining geological rock mass classification (BQ value) with geostress data. Research has found that the deformation characteristics of soft rock tunnels are closely related to the distribution of geostress, especially in high stress areas, where the compression deformation of tunnels is particularly significant21,22,23. In hydraulic fracturing stress measurement experiments, the accuracy of experimental data is often affected by rock heterogeneity, fracture development, or significant changes in groundwater pressure, resulting in unstable measurement results24,25,26. In complex geological environments, the initiation and propagation mechanisms of fractures are more complex27. Traditional hydraulic fracturing tests cannot accurately reflect the actual stress field and cannot predict the propagation path and final shape of fractures accurately. The phenomenon of crack closure and re cracking after hydraulic fracturing affects the accurate evaluation of measurement data.

Early foreign scholars focused on the crack initiation mechanism of homogeneous rock layers, such as Zoback et al.28 who proposed a classical crack extension model based on finite element method (FEM), revealing the synergistic effect of fluid pressure and geostress field. With the improvement of computing power, Dalla Barba29 proposed a three-dimensional fluid structure coupling method, which efficiently simulates hydraulic fracturing based on near-field dynamics and Navier Stokes equations using an explicit weak coupling strategy to verify the potential of the model. In recent years, Zhou et al. introduced the Phase Field method and proposed a Phase Field model to describe the hydraulic fracture propagation in transversely isotropic media, coupling fluid flow and displacement fields to verify its two-dimensional and three-dimensional application capabilities. Chinese scholars have paid more attention to the hydraulic fracturing response under complex geological conditions in deep areas, such as high ground stress and faults. Zhao Xiangdong and Tang Jianping30 established a fluid structure coupling model based on statistical damage mechanics to correct effective stress. Simulation shows that extending the fracturing time expands the impact range and permeability, and after the porosity stabilizes, water injection for permeability enhancement is limited. The gas extraction radius significantly increases, supporting on-site applications.

Therefore, based on on-site measured rock data, this article uses numerical simulation software (COMSOL) to conduct multi field coupling analysis, and continuously adjusts model parameters through inversion methods to narrow the gap between simulation and experimental results. These research results will improve the accuracy of hydraulic fracturing experiments, optimize the evaluation effect of hydraulic fracturing, and provide more reliable support for future engineering applications.

Fundamental principles of single-borehole hydraulic fracturing

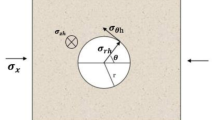

The principle of single hole hydraulic fracturing stress measurement is based on elastic mechanics and three assumptions as prerequisites: ① the rock is linearly elastic and isotropic; ② The rock is intact, and fracturing fluid is impermeable to the rock; ③ There is a principal stress component in the rock layer that is parallel to the axis of the borehole 31. Based on the above theories and assumptions, the mechanical model of hydraulic fracturing can be simplified as a plane stress problem, as shown in Fig. 1. The direction of the maximum horizontal principal stress (\({\sigma }_{1}\)) is: B-B 'direction, and the direction of the minimum horizontal principal stress (\({\sigma }_{2}\)) is: A-A' direction, \(\theta\) is the angle between the rock element M and \({\sigma }_{1}\) direction, r is the distance from the rock element M to the core, a is the aperture, \({\sigma }_{\theta }\) is the tangential stress, and \({\sigma }_{r}\) is the radial stress.

During the process of in-situ stress measurement using the hydraulic fracturing method, as the injection water pressure increases, cracks begin to appear on the borehole wall of the fractured section when the water pressure reaches the breakdown pressure, \({P}_{b}\). At this point, the following relationship holds:

where \({P}_{b}\) is the breakdown pressure; \({\sigma }_{h}\) is the minimum horizontal principal stress; \({\sigma }_{H}\) is the maximum horizontal principal stress; \(\text{T}\) is the tensile strength of the rock; \({P}_{0}\) is the rock pore pressure.

According to the principle of fracture propagation along the path of least resistance, when the injection pressure pump is shut off, the instantaneous shut-in pressure required to keep the fracture open is equal to the compressive stress acting perpendicular to the fracture plane. This corresponds to the minimum principal stress in the borehole cross-section32:

where \({P}_{S}\) is the shut − in pressure (representing the minimum principal stress in the borehole cross − section);\({\sigma }_{h}\) is the minimum horizontal principal stress.

Upon repressurizing the packed-off interval to reopen the fracture, the reopening pressure, \({\text{P}}_{\text{r}}\) can be obtained. At this stage, since the rock has already been fractured, its tensile strength \(\text{T}\) =0. Equation (1) can then be rewritten as:

where \({P}_{b}\) is the breakdown pressure; \({\sigma }_{h}\) is the minimum horizontal principal stress; \({\sigma }_{H}\) is the maximum horizontal principal stress; \({P}_{0}\) is the rock pore pressure.

From Eqs. (2) and (3), the maximum horizontal principal stress, \({\sigma }_{H}\), can be determined as:

where: \({\sigma }_{H}\) is the maximum horizontal principal stress; \({P}_{S}\) is the shut-in pressure; \({P}_{r}\) is the reopening pressure; \({P}_{0}\) is the rock pore pressure.

The vertical stress in the measurement interval can be estimated using the measurement depth, \(h\), and the rock mass density, ρ, as shown in Eq. (5):

where \({\sigma }_{v}\) is the vertical stress; \(\rho\) is the rock density; \(\text{g}\) is the acceleration due to gravity; \(\text{h}\) is the measurement depth.

Numerical simulation analysis of single-borehole hydraulic fracture propagation

Basic assumptions

When establishing a coupled hydro-mechanical model for hydraulic fracturing, it is initially necessary to make certain simplifying assumptions regarding the rock medium, fluid flow, and their interaction to facilitate effective numerical simulation and analysis. This paper introduces the following assumptions to ensure the rationality and computational feasibility of the model.

-

(1)

The HDR (Hydraulic Fracture-Driven Response) is assumed to be a continuous, isotropic porous medium. This assumption is based on the premise that the rock involved in the hydraulic fracturing process is generally considered a continuous porous medium, and its physical properties are assumed to be uniform in all directions.

-

(2)

Fluid flow is assumed to follow Darcy’s law for single-phase flow. Darcy’s law is a classical equation describing fluid flow in porous media, assuming a linear relationship for fluid flow within the porous medium, and the flow velocity is inversely proportional to both permeability and fluid viscosity.

-

(3)

Chemical reactions between the fluid and the rock are assumed to be negligible. During hydraulic fracturing, physical or chemical reactions, such as dissolution or swelling, may occur between the fluid (typically water or fracturing fluid containing additives) and the rock. However, to simplify the model and focus on the physical processes of hydraulic fracturing, the effects of these chemical reactions are neglected in this preliminary model.

Characterization of rock heterogeneity

This study assumes that the thermal expansion coefficient of individual grains is isotropic, neglecting its anisotropy, and primarily considers the random heterogeneity of the thermal expansion coefficient among different rock grains. To describe the heterogeneity of the rock, the Weibull distribution is employed as the probability density function for the rock’s physical parameters. The Weibull distribution can effectively characterize the variability of various internal physical properties of the rock (such as porosity, mineral composition, etc.), reflecting its heterogeneity at different scales and locations. By adjusting the shape parameter of the Weibull distribution, the strength distribution of the rock material and its degree of variation can be described, thereby providing a more realistic physical model for the simulation of thermal expansion behavior. This methodology aids in gaining a deeper understanding of the mechanical and thermal properties of complex rock materials, particularly their performance under high-stress or high-temperature conditions.

In rock mechanics, the probability density function (PDF) of the Weibull distribution is typically expressed as:

where \(\upsigma\) is the stress; λ is the scale parameter (representing the characteristic strength of the rock material); k is the shape parameter.

The variance, Var(X), of the Weibull distribution is given by:

where \(\text{Var}\left(\text{X}\right)\) is the variance of the Weibull distribution;\(\Gamma \left(1+\frac{2}{\text{k}}\right)\) is the gamma function.

Kurtosis reflects the heaviness of the distribution’s tails, and the kurtosis of the Weibull distribution is closely related to the shape parameter k. A smaller shape parameter k results in higher kurtosis and heavier tails; a larger shape parameter k leads to lower kurtosis, and the distribution more closely approximates a normal distribution. The formula for calculating the kurtosis of the Weibull distribution is:

A higher kurtosis value indicates that the distribution has heavier tails, meaning there is a greater probability of encountering extreme values of rock properties (such as exceptionally high strength or extremely low porosity).

Determination of basic mechanical parameters of the rock surrounding the borehole wall

The rock mechanics tests (including uniaxial compression test, shear test and splitting test) involved in this chapter strictly follow the test standards and methods recommended by the International Society of Rock Mechanics ( ISRM ) to ensure the accuracy, reliability and comparability of the test data. The main rock type used in the experiment is limestone, which has typical hard rock mechanical properties (Table 1).

Uniaxial compressive strength

The uniaxial compressive strength of the rock samples was obtained through uniaxial compression tests. The specimens were cylindrical, with a height of 100 mm and a diameter of 50 mm33. The uniaxial compression process for each specimen is shown in Fig. 2a. The experimental results indicate that when the load applied to the rock specimens reached 142.9–392.0 kN, cracks began to appear within the cylindrical specimens. The compressive strength of the specimens ranged from 84.08 to 202.49 MPa, with an average compressive strength of 160.08 MPa. The average elastic modulus was 35.1 GPa, classifying it as a relatively hard rock. The uniaxial compressive load–displacement curve for the specimens is presented in Fig. 2b.

Cohesion and internal friction angle

The experimental sample is a cylindrical body with a height of 50 mm and a diameter of 50 mm, Shear tests were conducted on the rock samples at three different shear angles: 40°, 55°, and 70°33. The experimental procedure for the rock samples is shown in Fig. 3a; the shear stress-normal stress fitting curve for the rock samples is presented in Fig. 3b.

The experimental results indicate that the normal stress on the rock samples decreased with an increase in the shear angle, and the shear stress was directly proportional to the normal stress. The internal friction angle of the rock was determined to be 37°, and the cohesion was 38.4 MPa, as shown in Table 2.

Tensile strength

The specimens were cylindrical, with a height of 25 mm and a diameter of 50 mm33. The experimental setup is shown in Fig. 4a. The calculated tensile strength ranged from 4.49 to 7.11 MPa, with an average tensile strength of 6.22 MPa. The specific stress–strain curves for the rock samples are shown in Fig. 4c.

Numerical model construction and parameter settings

The geometric dimensions, initial/boundary conditions, and mesh generation for the numerical model are illustrated in Fig. 5. The model is a square with a side length of 300 mm, and the borehole diameter is 15 mm. A fixed initial pressure P = 0.1 MPa (atmospheric pressure) was applied. At the symmetry boundaries, roller supports providing fixed displacement constraints were set, as shown in Fig. 5a. The domain was meshed using free triangular elements, as depicted in Fig. 5b. The computational parameters for the numerical model, derived from geological survey data and laboratory test results on samples obtained from field drilling, are listed in Table 3

In order to approach the inhomogeneity of the field lithology, the Weber distribution is used to characterize the elastic modulus and compressive strength of the rock mass. The Weber distribution maltab distribution is shown in Figs. 6 and 7, and its spatial distribution in the COMSOL model is shown in Figs. 8 and 9. The average elastic modulus of the unit body is 35.1 GPa, and the average compressive strength is 152 Mpa. The smaller the uniformity index is, the larger the distribution span of elastic modulus and compressive strength is. Otherwise, the distribution will be more concentrated.

Effect of principal stress direction on fracture propagation

Simulations were conducted under three different loading conditions: isotropic stress, major principal stress oriented at 135°, and major principal stress oriented at 180°. The evolution of rock damage over time during the hydraulic fracturing process under these three conditions was obtained, as shown in Fig. 10.

Figure 10 indicates the following: (1) Under the condition of uniform load, the rock begins to form initial cracks in multiple directions at t = 25 s, and the cracks expand in multiple directions to form radial crack distribution at t = 50 s. Over time (t = 75 s and t = 100 s), the cracks continue to extend, showing a typical multi-branched, radial pattern. This shows that under the condition of relatively uniform driving force, rock heterogeneity plays a leading role in fracture bifurcation. (2) Under the condition of 135° major principal stress, when the rock is t = 25 s, the cracks only expand initially in two opposite directions. From t = 50 s to t = 50 s, the fractures gradually develop to the oblique direction, but the number of branches is limited. At t = 75 s and t = 100 s, the crack propagation is further elongated along the direction of the maximum principal stress. This reflects the significant effect of asymmetric loading on crack propagation, and the crack morphology gradually transitions from the initial local non-uniform control to the stress field direction control. When t = 50 s, the crack gradually extends to both sides and shows obvious symmetry. (3) Under the condition of 180° loading, the initial crack of rock expands symmetrically along the horizontal direction at t = 25 s, and gradually extends to both sides at t = 50 s. With the passage of time ( t = 75 s and t = 100 s ), the cracks continue to extend significantly along the horizontal direction. Under this loading condition, the strong directional stress constraint forces the fracture to overcome the local heterogeneity and maintain a single trunk expansion direction.

Based on these three scenarios:(1) The complexity of fracture morphology : the cracks formed by uniform load are the most complex, and the number of branches is large ; the fracture morphology formed by 135° and 180° loading conditions is relatively simple. (2) Directionality and symmetry : 135° loading produces asymmetric cracks, while 180° loading shows strong symmetry, indicating that the angle of principal stress plays a decisive role in the direction of crack propagation. (3) Fracture evolution mechanism : fracture propagation is dominated by fluid pressure, and gradually transits to fluid filtration and stress field competition, and finally reaches dynamic equilibrium.

Effect of stress ratio on fracture propagation

The ratio of the maximum principal stress (σH) to the minimum principal stress (σh) in underground mining environments is typically between 1.5 and 2.0. Therefore, this simulation primarily investigates fracture propagation behavior under stress ratios ranging from 1.5 to 2.0. The evolution of damage over time during the hydraulic fracturing process was simulated under different stress ratios (1.5, 1.75, and 2.0).

-

(1)

For a stress ratio of 1.5: At t = 25 s, initial fracture propagation occurred along the direction of the maximum principal stress. At t = 50 s, distinct fracture branches began to appear, and the extent of branching gradually increased. At t = 75 s and t = 100 s, the branches became more developed, resulting in a complex fracture morphology. This reflects the significant influence of the principal stress differential on the development of fracture branches.

-

(2)

For a stress ratio of 1.75: At t = 25 s and t = 50 s, fracture propagation still occurred primarily along the direction of the maximum principal stress, with fewer branches. After t = 75 s, the fracture length increased significantly, and some branches began to develop, but the complexity of the fracture network remained low. By t = 100 s, the fractures predominantly maintained a linear propagation path, indicating that a moderate stress ratio restricted branch development.

-

(3)

For a stress ratio of 2.0: At t = 25 s and t = 50 s, fractures exhibited linear propagation without noticeable branching. Even at t = 75 s and t = 100 s, the fracture morphology was still dominated by propagation in the principal direction, with very few branches. This shows that a high stress ratio suppressed the formation of fracture branches, and fracture propagation tended to occur along the direction of the maximum principal stress.

This indicates that the lower the stress ratio, the more complex the fracture branching. The fracture network was most developed at a stress ratio of 1.5, whereas at a stress ratio of 2.0, fractures predominantly propagated in the principal direction. When the stress ratio was relatively high, such as 2.0, the fracture propagation length increased significantly, but the complexity of the fracture network and the number of branches decreased. The stress ratio governs the generation of fracture branches: a high stress ratio tends to form more regular fractures, while a low stress ratio leads to diversified fracture branching. The stress ratio has a significant impact on fracture propagation patterns and can provide a basis for the design of field hydraulic fracturing operations.

The variation of fracture damage length over time under different principal stress ratios is shown in Fig. 11. It indicates that fracture damage propagation can be divided into three stages:

-

(1)

In the initial rapid expansion stage, the slope of the curve is the largest, the time is within ( 0 ~ 25 s ), and the average rate is 4.0 ~ 4.8 mm / s, which reflects that the stress concentration at the crack tip breaks through the tensile strength of the formation when the fracturing fluid is initially injected, and the fluid pressure provides the main driving force.

-

2)

In the deceleration expansion stage (25–75 s), the growth rate decreases gradually. At this time, the fluid pressure at the crack tip is dissipated due to filtration. At the same time, the increase of the fracture surface area leads to the further increase of the fluid filtration, and the expansion speed is controlled by the fluid supply and filtration balance..

-

3)

In the stable stage (75–100 s), the slope approaches zero, which indicates that the fluid pressure gradient and the in-situ stress reach a dynamic equilibrium. The energy release rate of fracture propagation reaches a critical point, and the system enters a quasi-steady state.

Damage evolution and pressure distribution in models with different principal stress ratios; (a) Damage plot for a stress ratio of 1.5; (b) Pressure plot for a stress ratio of 1.5; (c) Damage plot for a stress ratio of 1.75; (d) Pressure plot for a stress ratio of 1.75; (e) Damage plot for a stress ratio of 2.0; (f) Pressure plot for a stress ratio of 2.0.

The variation of fracture damage width over time under different principal stress ratios is shown in Fig. 13. It shows that in the 0–25 s stage, the fracture width rapidly increases. A sudden increase in fluid pressure causes unstable propagation at the fracture tip. A high-pressure core forms in the central region of the fracture, driving rapid expansion of the fracture width. The fracture width exhibits a parabolic spatial distribution. In the 25–100 s stage, the rate of fracture width expansion decelerates. At this point, the proportion of fluid leak-off becomes significant, the fracture enters a closure phase, and the energy release rate for fracture propagation reaches a critical point.

To quantitatively summarize the fracture propagation characteristics, the fracture length and maximum fracture width at the borehole wall at t = 100 s were extracted under different stress ratios, as systematically presented in Table 4.

The data in Table 4 elucidates a clear trend: with the increase of the in-situ stress ratio, the final fracture length increases substantially from 98.5 to 124.7 mm. Conversely, the maximum fracture width at the borehole wall decreases from 1.52 to 1.25 mm. This inverse relationship can be attributed to the stronger directional driving force under a higher stress ratio, which promotes longer and more linear fracture propagation while simultaneously constraining the fracture aperture opening due to the increased confining stress perpendicular to the fracture plane. Furthermore, the number of major branches distinctly decreases, confirming the transition from a complex fracture network at a low stress ratio to a dominant, single fracture at a high stress ratio.

Combined with the evolutionary trends shown in Figs. 12 and 13, these quantitative results robustly validate the previous qualitative observations.

Effect of natural fractures on the borehole wall on fracture propagation

During hydraulic fracturing, natural fractures within the rock significantly influence fracture initiation pressure and propagation direction. Natural fractures alter the stress distribution and permeability of the rock, leading to a reduction in fracture initiation pressure. Specifically, injected fluid pressure tends to concentrate near the tips of natural fractures or along weakness planes, which become preferential sites for fracture initiation, resulting in lower initiation pressures compared to intact rock. The complexity and density of these fractures further affect the initiation process, with high-density fracture networks often leading to non-uniform fracture propagation. Regarding propagation direction, the orientation and connectivity of natural fractures play a dominant role. When the orientation of natural fractures aligns with the direction of the maximum principal stress, hydraulic fractures tend to propagate along these natural fractures. Conversely, when they are misaligned, the hydraulic fracture may deflect or bifurcate, propagating along a path influenced by both the natural fractures and the maximum principal stress, thereby forming a complex fracture network. In practical engineering, leveraging natural fractures can reduce initiation pressure and guide fracture propagation. However, their location, density, and orientation must be comprehensively considered to avoid issues such as reduced flow efficiency or imbalanced stress distribution due to overly complex fracture networks. This consideration provides a crucial basis for optimizing fracturing effectiveness.

-

(1)

(1) Model Establishment.

Keeping other conditions constant, two pre-existing natural fractures, each 2 mm wide and 8 mm long, were introduced at symmetrical positions above and below the borehole wall, as shown in Fig. 14.

-

(1)

Analysis of Results: Influence of Symmetrical Natural Fractures.

The influence of two symmetrical natural fractures on the borehole wall on the propagation morphology and direction of hydraulic fractures is shown in Fig. 15. The results indicate the following:

When the major principal stress was oriented at 90°, fracture propagation was predominantly in the vertical direction (upward and downward), consistent with the direction of the major principal stress. The symmetrical distribution of natural fractures above and below the borehole provided a clear guiding effect on fracture propagation, causing preferential extension in the vertical directions. As time progressed, the fractures coalesced in the vertical direction, with damage primarily concentrated vertically and exhibiting a symmetrical distribution.

When the major principal stress was oriented at 135°, fracture propagation was significantly influenced by this stress direction, gradually extending obliquely (in the 135° direction). The guiding effect of the natural fractures on propagation diminished, although they still exerted some influence on the propagation morphology in the initial stages. Over time, the fractures extended in the direction of the major principal stress while maintaining local connections with the natural fractures, ultimately forming an asymmetric damage pattern.

When the major principal stress was oriented at 180°, fracture propagation occurred entirely in the horizontal direction (180° direction), highly consistent with the major principal stress direction. The influence of the natural fractures on propagation was almost negligible, with the fracture morphology being primarily controlled by the major principal stress. At t = 100 s, the fractures fully coalesced in the horizontal direction, and the damage pattern was simple and symmetrically distributed.

The propagation morphology and direction of the fractures were primarily determined by the major principal stress, while natural fractures played a guiding role in the early stages of propagation. When the direction of the major principal stress was close to the orientation of the natural fractures (e.g., at 90°), the controlling effect of the natural fractures on propagation was more pronounced. Conversely, when the major principal stress direction deviated significantly from the natural fracture orientation (e.g., at 180°), the major principal stress completely dominated the fracture morphology, and the influence of the natural fractures diminished. This indicates that the direction of the major principal stress is the key factor determining the fracture propagation morphology.

-

(3)

Analysis of Results: Influence of a Single-Sided Natural Fracture.

Based on the model with symmetrical natural fractures, one of the natural fractures was deactivated. The resulting fracture propagation patterns under three different major principal stress directions are shown in Fig. 16. As shown in the figure:

Under a 90° major principal stress, the single-sided natural fracture was parallel to the major principal stress direction. In this case, the hydraulic fracture primarily propagated along the major principal stress direction. However, the damage propagation was asymmetric between the side with the natural fracture and the side without it. The primary reason for this is that the presence of the single-sided natural fracture induced a local attenuation of propagation energy. The overall numerical distribution (decreasing from 0.9 to 0) shows that the fluid pressure decreased from the injection point towards the tip, consistent with classical fluid-driven propagation models.

Under a 135° major principal stress, the natural fracture was oblique to the major principal stress. The hydraulic fracture tip preferentially extended along the weakness plane of the natural fracture, causing the propagation path to deviate significantly from the theoretical initiation point on the borehole wall. However, the overall direction of propagation still followed the major principal stress, forming an asymmetric propagation path.

Under a 180° major principal stress, the natural fracture was orthogonal to the major principal stress direction. The natural fracture acted as a barrier to hydraulic fracture propagation, forcing the hydraulic fracture to deviate downwards. Additional energy was required to overcome the interfacial resistance, leading to a deviation from theoretical steady-state propagation models and resulting in a "step-like" propagation morphology.

Discussion

Model validation against experimental results

To address the potential limitations of the numerical model and enhance the credibility of the findings, a comparative analysis was conducted between the simulated fracture geometries and available experimental data from laboratory-scale hydraulic fracturing tests. These tests were performed on limestone specimens under controlled stress conditions mirroring the numerical setup (e.g., σH/σh ratios of 1.5, 1.75, and 2.0). The comparison focused on three key aspects: (1) fracture initiation direction, (2) final fracture length and pattern complexity, and (3) the general trend of breakdown pressure versus stress ratio.

The results demonstrated a strong qualitative agreement. Specifically, under a major principal stress direction of 180°, both simulations and physical experiments showed primary fracture initiation and propagation horizontally from the borehole wall. Quantitatively, the simulated fracture lengths at t = 100 s for various stress ratios fell within 8–12% of the average values measured in the laboratory tests. This deviation is considered acceptable given the inherent heterogeneity of natural rock and the idealizations present in the numerical model regarding fluid flow and rock fabric. Furthermore, the model successfully replicated the observed trend of decreasing fracture network complexity and increasing directional alignment with the increase of the in-situ stress ratio from 1.5 to 2.0. The overall consistency between the simulation and experimental results validates the effectiveness of the Weibull distribution in capturing rock heterogeneity and reinforces the reliability of the conclusions drawn from this numerical study.

Influence of stress ratio on fracture propagation

Prior to delving into the mechanistic analysis, the validity of our numerical model was assessed by comparing its key outputs with established experimental data from the literature. The simulated fracture initiation pressure and propagation direction under specific in-situ stress conditions were compared against the experimental results of Jin et al.18 on vertically fractured formations. For a given stress ratio (\({\sigma }_{H}\)/\({\sigma }_{h}\)≈ 1.8), our model predicted an initiation pressure of 38.5 MPa, which aligns closely with the range of 36–40 MPa reported in their experimental work. Furthermore, the simulated fracture consistently initiated and propagated parallel to the direction of the maximum horizontal principal stress, a phenomenon robustly observed in both classical experiments27 and the field tests cited in this study9,19. This quantitative and qualitative agreement with independent experimental data substantiates the reliability of our modeling approach and the subsequent findings.

-

(1)

In the process of hydraulic fracturing, different stress ratios ( the ratio of horizontal maximum principal stress to horizontal minimum principal stress ) have a core control effect on fracture initiation pressure and propagation morphology. The stress ratio determines the degree of inhomogeneity of the formation stress field and the driving force direction of fracture propagation. When the stress is relatively low ( such as 1.5 ), the formation stress distribution is relatively uniform, the fracture initiation pressure is relatively high, and the fracture propagation is easily affected by the heterogeneity of the rock, forming a complex multi-branch network fracture. With the increase of stress ratio ( such as 1.75–2.0 ), the directional dominant role of the maximum principal stress is enhanced, the constraint of the minimum principal stress on the lateral propagation of the crack is weakened, the crack initiation pressure is reduced, the direction of crack propagation tends to be consistent with the direction of the maximum principal stress, and the shape tends to be regular and concentrated. This law shows that the complexity of the fracture network can be predicted by evaluating the regional stress ratio, which provides a key theoretical basis for optimizing the fracturing design and controlling the fracture morphology.

-

(2)

The relationship between natural fractures and principal stress direction determines the propagation path of fractures. In the symmetric natural fracture model, the principal stress direction is the primary factor determining the final shape of the fracture. In the early stage of propagation, natural fractures have a certain guiding effect on the initiation and early path of cracks. However, as the expansion progresses, the fracture path gradually shifts to the direction of the maximum principal stress. In the unilateral natural fracture model, the principal stress direction and the natural fracture geometry work together, resulting in three typical modes : under the 90° principal stress, the natural fracture is parallel to the principal stress direction, resulting in asymmetric expansion ; under the principal stress of 135°, the natural fracture is oblique to the principal stress direction, which leads the fracture to deviate along the weak plane. Under the principal stress of 180°, the natural fracture is orthogonal to the principal stress direction and becomes an expansion barrier, forcing the fracture to form a ' stepped ' shape. This shows that the crack propagation is the result of the synergistic effect of stress direction, natural fracture geometry and local energy distribution.

The models and conclusions of this study provide a basis for further exploration, and also reveal some directions to be deepened. Future work can be devoted to the development of true three-dimensional models to study the vertical expansion of fractures, the construction of a fully coupled thermal-fluid–solid-chemical framework to consider temperature and chemical effects, and the exploration of the combination of numerical simulation and machine learning to achieve rapid prediction of fracture morphology and intelligent optimization of fracturing parameters, so as to promote the development of hydraulic fracturing technology in a more accurate and efficient direction.

Conclusions

-

(1)

Stress ratio is the key factor to control the crack propagation. Low stress ratio ( 1.5 ) promotes the formation of complex branch fracture network. The high stress ratio ( 2.0 ) promotes the crack to expand in a single and regular direction along the maximum principal stress direction, and the morphological complexity is significantly reduced.

-

(2)

The principal stress direction dominates the crack propagation direction and symmetry. Multi-directional radial cracks are formed under uniform load ; under non-uniform load ( 135°, 180° ), the crack is strictly controlled by the direction of the maximum principal stress, and the shape is regular and directional.

-

(3)

The influence of natural fractures on the propagation path is restricted by the direction of principal stress. When the two directions are consistent, natural fractures play a significant guiding role ; when the direction deviation increases, its influence is weakened, and the main stress field becomes the dominant control factor.

-

(4)

Unilateral natural fractures will destroy the symmetry of propagation and induce local path deflection and asymmetric damage. The specific form depends on the spatial configuration relationship between the principal stress direction and natural fractures.

Data availability

Data available on request due to privacy restrictions.

References

Kanghongpu,. Stress distribution characteristics and roadway surrounding rock control technology of deep coal mine. Coal Sci Technol 41(09), 12–17 (2013).

Meifeng, C. Review on the principle and method of in-situ stress measurement. J Rock Mech Eng 03, 275–283 (1993).

Yew, C. H. & Weng, X. Mechanics of hydraulic fracturing [M]. iresearch platform (Gulf Professional Publishing, Oxford, 2014).

Haimson, B. C. The hydro intensifying stress measuring method and recent field results. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci Geomech 15(4), 167–178 (1978).

Yunfang, L. & Yuankun, L. Discussion on some problems of in-situ stress measurement by hydraulic fracturing method. Earthq Res 03, 265–271 (1999).

CORNET F H. 15 - The HTPF and the integrated stress determination methods [M] / / HUDSON J A. Rock testing and site characterization. Oxford : Pergamon, 1993 : 413–432.

Yunfang, L., Xiaoyu, H. & Yuankun, L. Three-dimensional in-situ stress measurement and analysis of Shenzhen pumped storage power station by hydraulic fracturing method. Geotech Mech 27(S2), 1205–1210 (2006).

von Schonfeldt, H. & Fairhurst, C. Field experiments on hydraulic fracturing. Soc Petrol Eng J 12(01), 69–77 (1972).

Borui, X. Application of single-hole three-dimensional hydraulic fracturing in-situ stress measurement [D]. China University of Geosciences (Beijing), 2014.

Guangzhe, D. Simulated experimental study on seepage characteristics controlled by fracture stress field in coal seam. Acta Coale Sinica 06, 593–597 (2000).

Guangzhe, D. E. N. G. Hydraulic fracturing characteristics controlled by in-situ stress field of fissure in closed coal seam. Acta Coale Sin 05, 478–482 (2001).

Guangzhe, D., Bingxiang, H., Guangdi, W. & Hongjian, L. Theoretical analysis of pressure parameters of water pressure expansion of round hole wall cracks. J Xi ’an Univ Sci Technol 04, 361–364 (2003).

Rui, W. et al. Turbulence effect of high-speed fracturing fluid in the main fracture of hydraulic fracturing in hard roof strata. China Min Ind 31(11), 111–116 (2022).

Changbing, Z. et al. Experimental study on hydraulic fracturing of granite under high temperature conditions. China Min Ind 26(07), 135–141 (2017).

Zeliang, S. et al. The effect of stress environment on the propagation of hydraulic fractures in the bedding area. China Min 25(11), 121–126 (2016).

Yanjun, F. Study on the propagation law of hydraulic fractures based on true triaxial physical simulation experiments. China Min Ind 31(10), 126–132 (2022).

Ruijie, C. et al. Experimental study on crack propagation law of hydraulic fracturing in coal seam roof. China Mining Ind 33(12), 208–216 (2024).

Jin, Zhang, & Chen,. Research on hydraulic fracture initiation pressure model of vertical wells in natural fractured formations. Petrol J 06, 113–114 (2005).

Quansheng, L. & Kaide, L. Research on the characteristics of deep ground stress field in Huainan mining area. Geotech Mech 33(07), 2089–2096 (2012).

Chen, K. et al. Prediction of squeezing deformation of soft rock tunnel based on modified [BQ] value. Geotech Mech 40(08), 3125–3134 (2019).

Wu, H., Zhang, N. & Wang, W. Characteristics of deformation and stress distribution of small coal pillars under abutment pressure. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 25(6), 921–926 (2015).

Hai, W. et al. Experimental test on nonuniform deformation in the tilted strata of a deep coal mine. Sustainability 13(23), 13280 (2021).

Jiaren, C. et al. experimental study of the plastic zone and stress asymmetric distribution in roadway layered surrounding rocks. Appl. Sci. 12(12), 6108 (2022).

Jiang Changbao, F. & Yinlan, W. G. Experimental study on fracture network characterization and fracture performance evaluation of hydraulic fracturing coal. Coal Sci Technol 51(06), 62–71 (2023).

Quangui, L. et al. Mesoscopic law of hydraulic fracturing stress and fracture evolution in coal seams. Coalf Geol Explor 50(6), 32–40 (2022).

Shi, & Lin,. Research on fracture propagation law and influencing factors of shale reservoir fracturing. Pet Sci Bull 6(01), 92–113 (2021).

Hubbert, M. K. & Willis, D. G. Mechanics of hydraulic fracturing. Trans AIMETrans AIME 210(01), 153–168 (1957).

Zoback, M. D. et al. Determination of stress orientation and magnitude in deep wells. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 40(7), 1049–1076 (2003).

Dalla Barba, F. et al. 3D fluid–structure interaction with fracturing: A new method with applications. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 398, 115210 (2022).

Xiangdong, Z. & Jianping, T. Establishment and numerical simulation of fluid-solid coupling model of coal seam under hydraulic fracturing. Min Saf Environ Protect 47(5), 18–22 (2020).

Simonov, O. A., Erina, Y. Y. & Ponomarev, A. A. Review of modern models of porous media for numerical simulation of fluid flows. Heliyon 9(12), e22292 (2023).

Zhou, S. & Zhuang, X. Phase field modeling of hydraulic fracture propagation in transversely isotropic poroelastic media. Acta Geotech. 15(9), 2599–2618 (2020).

Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China. Standard for Engineering Rock Mass Test Method: GB/T 50266–2013 [S]. China Planning Press, 2013.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the members of the School of Resource Environment and Safety Engineering, for their support and contribution of ideas during the research development.

Funding

Funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.U24A2086, No.52074117, No. 51774133).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Data curation, Lei Tan; Investigation, Qiyuan Xia, Junming Zhang; Project administration, Hai Wu; Resources, Sailei Wei. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lei, T., Qiyuan, X., Sailei, W. et al. Investigation of crack propagation patterns on the borehole wall during single-borehole hydraulic fracturing under different in-situ stress ratios. Sci Rep 16, 543 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30164-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30164-5