Abstract

We examine the relationship between rural wealth and the consumption of nutritious and healthy foods. Our measure of rural wealth is based on productive assets and the ownership of livestock by households. We relate this to household dietary diversity and food based dietary guidelines (FBDGs) which is a government-led initiative to promote overall health and prevent chronic diseases by fostering the consumption of nutritious and healthy foods. Employing a rich balanced panel data of about 6626 farm households, we estimate different panel data estimators. Our results reveal a clear positive association between wealth and dietary diversity a s well as the FBDGs. As rural wealth increases, households tend to shift from starchy foods to more nutrient-rich sources, particularly those high in protein. Notably, individual food groups such as fruits, vegetables, dairy, legumes, and fish show increases in consumption as assets and livestock holdings grow, as do animal-sourced foods such as meat, milk, and eggs. Among livestock, large ruminants have the greatest impact on households’ intake of nutritious foods. Further, our findings highlight the gendered nature of nutritional gains, with all households—including those headed by women benefiting from increased wealth. Nutritional improvements are especially pronounced when women have greater bargaining and decision-making power in the household. Overall, we show that livestock and asset ownership could be significant entry and leveraging points for improving the consumption of nutritious and healthy foods with implications for improved health and wellbeing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hunger and food insecurity continue to be important development challenges facing developing countries1. While progress has been made, this remains heavily challenged by different shocks such as climate change, conflicts, and health pandemics2,3,4. There have been deliberate attempts to address these, as evidenced in global targets such as the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development which encompasses the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)5. The second SDG seeks to create a world free of hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition while promoting sustainable agriculture by 2030. However, progress to achieve these targets are overall slow6. As it stands, about 1 in 10 people are hungry with 2.4 billion experiencing moderate to severe food insecurity6. In terms of achieving the various targets of reducing hunger and increasing the consumption of nutritious and healthy foods, only about 17% of the targets are on track to be achieved by 2030. On the flip side, there is also marginal progress in achieving a similar proportion (17%) of these goals, while there has been regression and at best stagnation for about 65% of these targets7.

So far, several factors have been highlighted as limiting the achievement of these goals of reducing hunger and increasing the consumption of nutritious and healthy foods. Some of these factors range from climate change3, conflicts2,8, health pandemics4, and food prices9,10, and farm production diversity11. Affordability of nutritious and healthy foods has also been shown to be a constraining factor in the access and consumption of nutritious foods12,13,14. From all these studies, the role of wealth comes out strongly. Different proxies of wealth are associated with dietary diversity15,16,17,18. While some of these relationships are positive, others are negative. Livestock and other productive assets could be used to increase the production of food. Moreover, livestock could also provide animal-sourced sourced food such as meat, milk and eggs besides serving as saving devices and increasing resilience in rural areas19. Despite these positive implications, the relationship between wealth and diet is complex and often non-linear. For instance, recent literature suggests that the consumption of unhealthy foods, especially ultra processed foods increases with wealth20. Given these mixed insights so far, more evidence is warranted about this important relationship.

In this paper, we examine the relationship between wealth and the consumption of nutritious and healthy foods. We are interested in answering the question - how does rural wealth (assets and livestock) affect dietary diversity and the consumption of nutritious foods? By rural wealth, we refer to livestock ownership as well as the ownership of productive assets (e.g., farm equipment, fishery tools, or information assets) that households could sell and use to smooth consumption in times of shocks. Some of these assets include agricultural and irrigation equipment that increase agricultural production, livestock for manure and draught power, fishery equipment that increase the production of aquatic foods and information assets that increase the provision of nutrition information and guidelines to households11,21,22. We consider different outcomes of food consumption such as the household dietary diversity score (HDDS) which comprises 12 food groups commonly consumed by households23. We also use the Zambian food based dietary guidelines which is a contextual, flexible, locally developed, and adaptable food guide recommended for improved nutrition and health in Zambia6. Unlike the standard HDDS, it is made up of six food groups: cereals, starchy roots, and tubers; vegetables; fruits; fish, insects, and animal-source foods; dairy; and legumes, pulses, and nuts. We further create different cutoffs around the Zambian FBDGs where we explore the consumption of all the six food groups as well as at least three of the food groups. In the interest of heterogeneity, we also estimate the association between assets and livestock and the individual food groups. We further disaggregate livestock into large ruminants, small ruminants, and poultry to understand their individual contribution to the consumption of nutritious and healthy foods. Given the important role of women in livestock keeping19, we perform some gender disaggregated analysis exploring intra-household decision making by women.

We employ a rich two wave balanced panel dataset of 6626 households in Zambia and estimate the correlated random effect model to control for time invariant unobserved heterogeneity. We also estimate the standard household fixed effect estimator. We obtain several key results. First, we observe a positive association between livestock ownership and the consumption of nutritious and healthy foods, an insight which is maintained when we also consider the ownership of productive assets. Second, we observe a positive association between livestock and assets and the consumption of nutritious and healthy foods in line with the Zambian FBDGs. Third, we underscore food group heterogeneity where we find that in response to assets and livestock increases, households tend to consume healthy food groups such as fruits and vegetables, diary, legumes, and fish. Deep diving into what livestock matters, we further show that cattle offer the biggest nutritional gains to households. The fifth key insight is the gendered nature of these results where we show that all households, including female headed households are benefitting from the ensuing nutritional gains. In addition, we show higher nutritional gains when women are in charge of household decision making and control. These insights are robust to several cut-offs of the outcomes, estimation strategies and the use of both linear and non-linear modelling approaches.

The study makes several contributions to the empirical literature on rural wealth and the consumption of nutritious foods. It demonstrates that ownership of productive assets and livestock—often representative of wealth in rural communities could serve as significant entry points for improving dietary diversity and promoting the consumption of healthy foods24. Livestock shows strong positive effects on the intake of animal-sourced foods such as milk, eggs, meat, poultry, and fish, supporting findings from previous research in conflict-affected and smallholder settings8,19,25,26. Our study provides empirical support to studies that have established that assets act as buffers against income shocks27,28,29.

Additionally, the paper highlights the role of locally developed FBDGs in Zambia and shows that increases in assets and livestock support households in meeting these dietary standards and improving overall welfare. We identify cattle as the most influential livestock for driving nutritious food consumption, followed by goats and poultry25. Another notable contribution is from a gender perspective. We find that nutritional improvements benefit all households, including those led by women. The positive impact of livestock ownership is especially pronounced in female-headed households, while the benefits of asset ownership are somewhat less for these households compared to male-headed ones. This suggests distinct underlying mechanisms—livestock may directly enhance food consumption in female-headed households, whereas in male-headed households, assets may be used to smooth consumption or generate income for food purchases. Moreover, the findings reveal that when women oversee household decision-making relating to production, consumption and commercialization, the consumption of nutritious and healthy foods increases.

Data and variable measurement

Rural livelihood household survey

We rely on the 2015 and 2019 panel waves of the Rural Agricultural Livelihoods Survey data from Zambia. The survey was led by the Indaba Agricultural Policy Research Institute (IAPRI) in collaboration with the Ministry of Agriculture and the Zambia Statistics Agency. The survey is nationally representative and involved the country’s 10 provinces namely Central, Copperbelt, Eastern, Luapula, Lusaka, Muchinga, Northern, Northwestern, Southern, and Western provinces. The survey followed a stratified two-stage sampling design. In the first stage, primary sampling units which were enumeration areas were defined, and this involved a minimum of about 30 farm households. From this, a household listing exercise was undertaken, and households were stratified based on the total area under crop cultivation, cultivation of some special crops and livestock ownership as well as sources of income. Systematic sampling was then carried out to select 20 households across the three strata in each of the randomly selected enumeration areas.

The RALS 2012 covered 442 Standard Enumeration Areas (SEAs) across the 10 provinces and a total of 8,839 households. In 2015 and 2019, 7933, and 7241 households were surveyed. The sample in 2015 and 2019 were expected to yield reliable estimates at provincial and national levels except for the Eastern province, whose estimates are statistically valid at the district level as well. In 2015 and 2019, the survey included a 24-hour recall of the various food groups that were consumed by households, alongside food expenditures. For the outcome measures, the survey has detailed sections on the various income sources of the household, gender issues as well as all the assets that are owned by the household.

Measurement of variables

Zambian Food-Based dietary guidelines

Food-Based Dietary Guidelines (FBDGs) define what a healthy diet means to a country by providing harmonized food and nutrition guidance that can inform and orient food-system policies and programs. The Zambian Food-Based Dietary Guidelines (FBDGs) provide scientifically proven recommendations on diet and a healthy lifestyle to prevent and reduce the risk of non-communicable diseases while meeting nutrition and energy requirements. This FBDG technical manual is primarily intended for technical experts who promote food consumption and diets for use in designing, implementing, and assessing nutrition programs including the development of policies and nutrition education materials. The development of the FBDGs in Zambia was multi-sectoral, involving stakeholders from different sectors. It involved the consolidation of comprehensive evidence to establish the diet and health relationships, benefits of eating well and risks of unhealthy foods which formed the scientific basis of the FBDGs. An assessment was conducted for communities (end users) to ensure an understanding of the guidelines as well as pre-test acceptability and usability of the guidelines. Therefore, the guidelines are grounded on the food systems approach, taking cognizance of the available local foods and the consumption patterns. The Zambia FBDGs are based on the six food groups1: cereals, starchy roots, and tubers2; vegetables3; fruits4; fish, insects, and animal-source foods5; dairy; and6 legumes, pulses, and nuts. We count the number of individual food groups consumed by households. In addition to these, we also generate various cutoff variables to understand heterogeneities therein. We create two dichotomized variables capturing households that consume all six of the individual food groups of the FBDGs and those that consume at least three of these food groups.

Household dietary diversity scores

We also rely on the household dietary diversity scores (HDDS) which is a standard measure of food access and availability in smallholder farmers and is very useful for cross-country comparisons and analyses25. The HDDS is derived from a 24-hour food intake recall that any household members have consumed within the household. The score is designed from 12 standard food groups. The 12 groups are cereals, white tubers and roots, legumes, nuts and seeds, vegetables and vegetable products, fruits, meat, eggs, fish and fish products, milk and milk products, sweets and sugars and syrups, oils and fats, spices, condiments, and beverages. However, the standard 12 food groups in HDDS also contain foods with little or undesirable nutritional and health effects particularly when consumed in large quantities (sugars and sweets, oils and fats, and condiments). Hence, we also compute the HDDS of 9 healthy food groups, excluding these unhealthy food groups4.

Wealth (Assets and livestock)

We proxy for wealth using assets and livestock. For livestock, we considered the number of livestock owned such as cattle, goat, sheep, and poultry. From this, we use the livestock conversion scale to transform them into tropical livestock units30. This conversion is based on the Food and Agriculture conversion scale where a large ruminant such as cattle takes a value of 0.7, a small ruminant such as goats and sheep takes 0.1 while poultry assumes a value of 0.01.

For assets, we consider different sets of productive assets and inputs that are important for stirring farm production and productivity increases, livestock productivity and strengthening small scale fisheries. Some of these assets include farm equipment (ploughs, harrows, cultivators, rippers, planters, tractor, knapsack sprayers), irrigation equipment (water pumps, irrigation trucks and lorries, water tank, boreholes), transport assets (trailer, motorcycle, bicycle), livestock assets (cattle dip, crush pen), processing equipment (crop shellers, hand mills, hammer mills), fishery assets (fishing nets, boats, canoes), information assets (TV, radio, cell phone) and other assets such as sewing machine, generators and solar panels. From these assets, we generate an asset index using principal component analysis (PCA). PCA is a method used to reduce the number of variables in a dataset while retaining as much of the original data’s variance as possible. It does this by identifying directions along which the data varies – these directions are known as principal components. In our case, the first principal component serves as a general wealth indicator and captures a large share of asset variance.

Linking wealth and dietary diversity

Assets and livestock can play a significant role in enhancing the consumption of nutritious and healthy foods through multiple pathways. First, they can be consumed directly as animal source foods (ASFs), providing essential nutrients for improved health8,25. Second, productive assets may be utilized for farm production, increasing the availability of diverse and nutritious foods11,19. These assets enhance agricultural productivity, enable households to cultivate a wider range of crops, ensuring year-round access to various food groups. For example, irrigation equipment can support vegetable and fruit production during dry seasons, while crop processing equipment allows for better storage and utilization of harvests, reduce post-harvest losses and improveoverall food security. Third, information assets such as radios and mobile phones enable the delivery of campaigns and educational programs that promote the consumption of nutritious and healthy foods22,37. Access to such information can empower households to make informed choices regarding food purchases and consumption, helping them to better understand the importance of including all recommended food groups in their diets.

Additionally, assets can serve as a saving mechanism, representing wealth that can be drawn upon for food purchases or investments in nutrition33. For instance, households may sell livestock or utilize productive assets to generate income that can be used to buy food items that are not produced on-farm, such as fruits, vegetables, or dairy products. This financial flexibility is crucial during periods of food scarcity or economic hardship, enabling households to maintain dietary quality and diversity. Livestock assets also function as a buffer and risk-coping strategy, helping households manage income shocks and maintain food security (28‚29 ‚35). Finally, assets can stimulate non-farm employment, generating income that further supports access to nutritious foods (19‚38). Ownership of transport assets, small machinery, or information devices can create opportunities for wage labor, trading, or service provision within and beyond the agricultural sector. This diversification of income sources strengthens household resilience and expands the means through which households can purchase variety of healthy foods. Overall, these multiple pathways highlight how assets and livestock may increase the consumption of nutritious and healthy foods. In doing so, one overlapping and moderating factor is the role of gender19. Gender plays a moderating role by shaping decision-making and control over resources, thereby affecting household dietary outcomes and priorities.

Ethical considerations

This study made use of data from the Rural Agricultural Livelihood Survey (RALS), through a partnership with the Central Statistical Office (now the Zambia Statistics Agency) and the Ministry of Agriculture. As the Zambia Statistical Agency is legally authorized to conduct national surveys, it is not required to seek separate ethical approval. Before the interviews began, all participating households provided informed consent.

Empirical strategy

We are interested in understanding the relationship between wealth and the consumption of nutritious and healthy foods. Given that we have panel data, we directly dive into panel data models estimating the following regression equation:

\(\:{Y}_{it}\) represents the various outcomes of interest including HDDS, FBDGs and various cutoff points on FBDGs. Our variable of interest is \(\:{A}_{i}\) whose parameter estimate \(\:\delta\:\) shows the relationship between wealth (livestock and assets) and the various outcomes. \(\:{\varvec{X}}_{\varvec{i}}\) is a vector of household level control variables and \(\:{\mu\:}_{i}\) is the stochastic error term. We also have \(\:{c}_{1i}\) which represents time-invariant unobserved heterogeneity, \(\:{d}_{t}\) is time-fixed effects, and \(\:{\mu\:}_{it}\) is the stochastic error term. Our panel data enables us to effectively control for time-invariant unobserved heterogeneity such as skills, preferences, and motivation which may be driving both wealth and dietary diversity.

Two common estimators commonly used to control for time invariant unobserved heterogeneity are the household fixed effect (FE) estimator and the random effect (RE) estimator. The choice of any of these estimators depends on the assumptions about correlations between unobserved heterogeneity and the observed characteristics. It may also depend on the level of within-variation in the outcomes and the length of the panel. For linear models, the FE estimator has been used as the workhorse in controlling time-invariant unobserved heterogeneity. However, this estimator could lead to the incidental parameters problem for non-linear models. The RE estimator on the other hand is quite restrictive and is more commonly used in experimental studies given that it assumes strict exogeneity (no correlation) between the observed covariates and unobserved heterogeneity31. To relax this strict assumption, pseudo fixed effects estimator also known as the Mundlak Chamberlain device (correlated random effect model) is recommended. These models assume that the correlation between observed covariates and unobserved heterogeneity is a linear function of the average across time of all the time-varying covariates in Eq1. (32). This estimator has several advantages over both the FE and RE estimators: (1) it relaxes the strict exogeneity assumption of the RE estimator2, it provides more efficient estimates than the FE estimator when the within variation in data is smaller than the between variation and avoids the incidental parameters problem for non-linear models. We use both the CRE model and test robustness by also specifying the FE estimator31. In terms of application, the CRE model is akin to the RE model but with the addition of time averages of all time-varying covariates (\(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{\varvec{X}}}_{\varvec{i}})\) as shown in the following specification:

So far, we have controlled for time invariant unobserved heterogeneity but have not controlled for reverse causality in the relationship between wealth and dietary diversity. Addressing this would require an instrumental variable which is usually not trivial to find in such settings. Given we could not control this bias, we refer to our estimates as correlates that are suggestive of the impact of wealth on the consumption of nutritious and healthy foods. By no means are our estimation results causal given these identification shortfalls.

Results and discussion

Descriptive insights

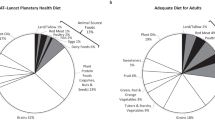

Table 1 shows the summary statistics of the variables used in the empirical estimation over the panel years and when pooled. The HDDS in 2015 was 5.90 which rose to 6.13 in 2019 indicating that households are consuming diverse diets. After excluding the three unhealthy food groups, we still observe an average consumption of about 4 food groups. An interesting insight here is the increase in HDDS12 over the panel years. For the same period, the HDDS9 rather decreases, suggesting that the consumption of some nutritionally questionable foods increases over time. Akin to the HDDS9, we also observe a reduction in the FBDGs. Figures 1 and 2 show the consumption of the individual food groups of both HDDS and FBDGs and their percentage changes over time.

Turning to the Zambian FBDGs which rely exclusively on the consumption of 6 nutritious and healthy foods, we further observe that households are consuming about 4 of these food groups suggesting adherence to these nutrition guidelines. The FBDG cutoffs further tell an interesting story wherein just 3% of households consume all 6 food groups (FBDG1) as opposed to 67% that consume at least 3 of the 6 food groups (FBDG2). One interesting trend from Fig. 2 is the increasing consumption of pulses such as legumes which have been described as pro-poor and environmentally friendly. Households report an average livestock unit of about 3.3 per household implying livestock is an important asset for them that they can consume, sell, or use as a saving mechanism.

Empirical insights

Here, we present the empirical results of the association between wealth (livestock and asset ownership) and the various food consumption indicators including the HDDS, FBDGs and the various cutoffs from the FBDGs. We also present the results of the heterogeneity analyses based on livestock, the different individual food groups and by gender. We also present some robustness checks where we employed different non-linear estimators.

Wealth and dietary diversity

We begin with the association between livestock and HDDS with and without additional controls. As shown in Fig. 3, we observe a positive association between livestock and the consumption of diverse diets by households. In response to livestock increases, households increase their dietary diversity and consume more diverse foods.

Livestock and HDDS. Notes This figure shows the CRE estimates of livestock and household dietary diversity score. The controlled specification includes controls such as age and educational level, gender of the household head, household size, access to extension services and cooperative membership, credit access, distance to farm, farm size and cultivated land, market participation, off-farm participation, income per capita, occurrence of droughts, floods as well as pest and disease shocks. These results are significant at the 1% level of probability. Full results are presented in Table S1 in the supplementary material.

Figure 4 also shows a positive association between assets and the consumption of diverse foods among smallholder households. Households with greater assets tend to have more diverse diets compared to those with fewer assets, highlighting the importance of these productive assets which have been highlighted to represent rural wealth for the most part24,33. Higher levels of assets may indicate better access to a variety of foods, leading to improved dietary diversity. Moreover, different categories of assets (farm and irrigation equipment, livestock manure) can increase farm production diversity which is important for the consumption of healthy and nutritious foods11.

Asset index and HDDS. Notes This figure shows the CRE estimates of livestock and household dietary diversity score. The controlled specification includes controls such as age and educational level, gender of the household head, household size, access to extension services and cooperative membership, credit access, distance to farm, farm size and cultivated land, market participation, off-farm participation, income per capita, occurrence of droughts, floods as well as pest and disease shocks. These results are significant at the 1% level of probability. Full results are presented in Table S1 in the supplementary material.

These positive associations between wealth and HDDS could be explained by different factors. For instance, livestock such as poultry, goats and cattle can be consumed directly as meat and could also provide other ASFs such as eggs and milk34. Moreover, assets are usually productive and can be utilized to provide additional income support to households to enable them to purchase a diverse portfolio of food from markets. Besides, livestock could also be used as a saving device and to smoothen consumption in times of shock such as conflicts and climate change29,35. Under such shocks, households could either consume these livestock directly or sell to get income which can be used to purchase other food items19,36.

Wealth and Zambian FBDG

We now show the insights from the association between wealth and the FBDGs. As shown in Fig. 5, we observe a positive association between livestock and the consumption of diverse diets. Remember that these FBDGS are made up of 6 food groups (pulses, beans, nuts, and seeds; dairy; fish, insects, and meat; fruits; vegetables; and cereals and tubers) that are locally adapted in the Zambian context and offer nutritional and health gains to smallholder households. Figure 6 also shows similar insights for assets where we observe that in response to livestock increases, households increase the consumption of nutritious and healthy foods in line with the Zambian FBDGs. This is an interesting insight as the FBDGs are very much in line with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly Goal 2 (Zero Hunger) and Goal 3 (Good Health and Well-being). Thus, we underscore and show that a critical entry point to increase the consumption of nutritious and healthy foods could be to stimulate asset and livestock ownership as they have the potential to be productive and ensure nutritional gains.

Livestock and FBDGs. Notes This figure shows the CRE estimates of livestock and household dietary diversity score. The controlled specification includes controls such as age and educational level, gender of the household head, household size, access to extension services and cooperative membership, credit access, distance to farm, farm size and cultivated land, market participation, off-farm participation, income per capita, occurrence of droughts, floods as well as pest and disease shocks. These results are significant at the 1% level of probability. Full results are presented in Table S2 in the supplementary material.

Assets and FBDGs. Notes This figure shows the CRE estimates of livestock and household dietary diversity score. The controlled specification includes controls such as age and educational level, gender of the household head, household size, access to extension services and cooperative membership, credit access, distance to farm, farm size and cultivated land, market participation, off-farm participation, income per capita, occurrence of droughts, floods as well as pest and disease shocks. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1. Full results are presented in Table S2 in the supplementary material.

Our findings on the positive association between wealth and the consumption of nutritious and healthy foods corroborate different studies in the existing literature on the positive implications of assets and livestock ownership for food and nutrition security19. Specifically, we bolster existing studies on the importance of livestock as a source of animal-sourced foods which increase food and consumption diversity8,25,26. One important pathway that may be driving the results is access to different information assets such as television, radio, and mobile phones that can be used to deliver information campaigns and knowledge on the consumption of nutritious and healthy foods37. Moreover, mobile phones could be used to enhance the impact of remittance on food access22.

Further analysis on Zambian FBDG

In the interest of understanding more about the association between wealth and the FBDGs, we created some cutoffs on these food groups. In the previous regression, we just modeled the number of food groups consumed in the FBDGs. Given that more is better in terms of a balanced diet and assuming appropriate nutritional bundles, we created two dummies for households that consume all 6 individual food categories as well as at least 3 of these food categories. Table 2 shows the results of the association between wealth and the consumption of all the food categories in the FBDGs. We observe a positive association between both assets and livestock and this outcome.

Table 3 presents the relationship between wealth and the consumption of at least three of the food categories of the FBDGs. The magnitudes here are larger than in the case of the consumption of all the food categories. For instance, as shown in column4, an additional livestock unit leads to a 0.2 percentage point increase in consuming at least three of the six food categories. For assets, this is even larger (about a 5-percentage point increase).

Beyond these FBDGs cutoffs, we also take a deep dive to understand which individual food groups respond more to wealth increases. We present the results for the individual HDDS groups in the supplementary material (Tables S5 and S6) and keep the individual FBDGs here. Table 4 shows the relationship between livestock and the consumption of all 6 individual food categories. All the coefficients are positive, but we only observe a statistically significant effect for dairy and vegetables. Every additional livestock unit leads to an increase in dairy and vegetable consumption by about 0.1 and 0.6 percentage points respectively. These results are indicative of two of the pathways that we described above about the possible consumption of animal-sourced foods from livestock, but also about access to nutritious foods which could happen through livestock sales11,25,26,34,38,39.

Table 5 shows the relationship between assets and consumption of the individual food groups. Unlike with the livestock case, we observe positive and statistically significant associations for all the food groups except starch. This is an important result as households with better access to assets are moving away from the consumption of starch. In terms of the magnitudes of the individual food groups, we observe the biggest impact on the consumption of fish, dairy products, fruits, legumes, and vegetables in that order. As previously highlighted, this could be explained by access to nutritious and healthy foods for asset rich households which could arise from asset sales19,36 as well as utilizing these assets for farm production which is a driver of dietary diversity. Moreover, the impacts on fish consumption could be explained through the ownership of fishery assets such as fishing nets, boats, and canoes which can increase the capture of fish and other aquatic products21.

Livestock heterogeneity analysis

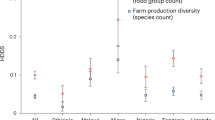

So far, we have considered livestock without understanding which livestock matters more for food consumption and diversification. We now consider the different livestock by categorizing them into large ruminants, small ruminants, and poultry. We find evidence about the importance of all the different livestock categories although their contribution to food consumption and diversity varies and decreases with their size. Figure 7 reveals that cattle have the most significant influence on dietary diversity and nutritional outcomes in rural Zambian households. Indeed, cattle ownership indicates a higher economic status for households. In terms of food consumption, households owning cattle have access to animal-source foods such as milk and meat, which can contribute to a more diverse and protein-rich diet39. Households owning small ruminants may benefit from increased protein intake and dietary diversity as shown in Fig. 7. Additionally, small ruminants are often more affordable and easier to manage than cattle, making them accessible to a wider range of households especially women. Finally, ownership of poultry can enhance household nutrition by increasing access to protein-rich foods. Poultry are also relatively low-cost livestock options, making them accessible to households with limited resources34,40. Moreover, poultry ownership is usually gendered as they are managed by women for the most part19.

Livestock heterogeneity. Notes This figure shows the CRE estimates of livestock and household dietary diversity score. The controlled specification includes controls such as age and educational level, gender of the household head, household size, access to extension services and cooperative membership, credit access, distance to farm, farm size and cultivated land, market participation, off-farm participation, income per capita, occurrence of droughts, floods as well as pest and disease shocks. Results are statistically significant at the 1% level of probability. Full results are presented in Table S9 in the supplementary material.

Gender insights

We also explore whether there are disparities in dietary diversity and nutritional outcomes based on gender. Understanding gender heterogeneity about assets is crucial for designing gender-sensitive interventions and policies that promote equitable access to healthy and diverse diets. Policymakers can use these to address gender disparities in asset ownership and empower women in decision-making related to food security and nutrition in the household. We perform two different estimations to shed light on gender heterogeneity. In the first place, we consider the gender of the household head and perform some regressions using this sub-sample. In the second place, we go deeper to understand who the main decision maker of the household is, as these matters more for food consumption and dietary diversity19.

Table 6 shows the relationship between wealth, HDDS and FBDGs for the female headed sub-sample. We obtain positive and statistically significant associations for both HDDS and FBDGs with livestock and assets. This suggests that nutritional gains from livestock and asset ownership translate to both male and female headed households. A further analysis and comparison with the male headed sample shows that these effects are also positive, but the magnitudes are lower for the case of livestock, although higher for assets (Table S12 in the supplementary material). While women are more attached to livestock which may offer their households immense nutritional gains, male headed households on the other hand own more assets which they can use to support their household food consumption needs. Our result corroborates earlier analysis showing that women’s ownership of assets can greatly strengthen their income generating capacity and increase their bargaining power in households21.

After showing that nutritional and food consumption gains translate to male as well as female headed households, we forge on to understand what happens when women are decision-makers (in charge of decision-making regarding assets and livestock) in households. Just like the case of the female headed households, we created two samples where we compare the magnitudes for households where women are main decision makers versus men. Table 7 shows the insights from the sub-sample when women are decision makers in the household. The main insights about the positive implications of dietary diversity and adherence to the FBDGs are maintained. Comparing the two sub-samples, we observe larger magnitudes for women decision makers than for men (Table S13 in the supplementary material). This provides more empirical support on the important role of women when it comes to increasing and ensuring the consumption of nutritious and healthy foods. Despite these insights from the sub-sample analysis, one may argue that this does not clearly show the role of female headed households and gendered decision making. Given this, we interacted our two gendered variables with assets and livestock. Tables S14 and S15 in the supplementary materials show these results. We find higher magnitudes for the association between assets and diets for both female headed households and when women have control over decision making. For livestock, we only obtain statistically significant results for male headed households, possibly suggesting aspects of limited livestock ownership by women.

Robustness checks and additional analysis

We undertake some robustness checks to confirm and bolster the existing claims from the analyses. In the first place, we reduce the number of food groups in the HDDS from 12 to 9. Here, we exclude some unhealthy food groups such as spices, sugars and condiments and estimate the association with wealth. As shown in Figs. 8 and 9, we again observe a positive association between livestock and assets with the consumption of a diverse set of nutritious and healthy foods. These insights offer more evidence on the important role of wealth in increasing the consumption of nutritious and healthy foods.

Livestock and reduced HDDS. Notes This figure shows the CRE estimates of livestock and household dietary diversity score. The controlled specification includes controls such as age and educational level, gender of the household head, household size, access to extension services and cooperative membership, credit access, distance to farm, farm size and cultivated land, market participation, off-farm participation, income per capita, occurrence of droughts, floods as well as pest and disease shocks. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1. Full results are presented in Table S16 in the supplementary material.

Assets and reduced HDDS. Notes This figure shows the CRE estimates of livestock and household dietary diversity score. The controlled specification includes controls such as age and educational level, gender of the household head, household size, access to extension services and cooperative membership, credit access, distance to farm, farm size and cultivated land, market participation, off-farm participation, income per capita, occurrence of droughts, floods as well as pest and disease shocks. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1. Full results are presented in Table S16 in the supplementary material.

The second robustness check is about employing a nonlinear model in place of a linear model. Three of our outcomes, the HDDS of both the 12 and 9 food groups and the FBDGs are all count outcomes. To properly account for this count nature of the outcomes, we use a Poisson regression model that is best suited for these outcomes41. As shown in Table 8, our estimates are similar in sign, magnitude, and statistical significance to the linear estimations for both assets and livestock. This adds credence and supports the evidence so far on the positive association between wealth and the consumption of nutritious and healthy foods.

Implications for global food security and poverty

Our findings have important implications for SDG 2 (zero hunger), SDG 3 (good health and well-being), SDG 5 (gender equality), SDG 8 (decent work and economic growth), and SDG 12 (responsible consumption and production). Moreover, it is policy relevant as it is based on FBDGs which is a growing initiative of many Governments in Africa in line with multinationals such as the Food and Agriculture of the United Nations. As it stands, about 12 African countries currently have FBDGs. Some of these countries are Benin, Ethiopia, Gabon, Ghana, Kenya, Namibia, Nigeria, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, and South Africa, Tanzania and Zambia6. We identify some policy options to reach these stated goals based on the findings of the study. Some of these relate to strengthening livestock development programs and stirring agricultural investments as well as gendered-sensitive policies.

Implementing livestock development programs that support smallholder farmers in acquiring and managing livestock can be beneficial. These programs can focus on improving animal husbandry practices, providing veterinary services, and facilitating access to markets for livestock products, thereby enhancing household food security and dietary diversity. Livestock represents an important aspect of rural wealth in many African countries as they offer a plethora of benefits especially in arid and semi-arid countries. Many households usually amass productive assets such as livestock after seasonal harvests33,42. As lack of banking facilities and other saving vehicles are common in many rural areas due to missing and imperfect markets, households turn to saving in these assets, and livestock which can increase food consumption and diversity24. Relatedly, encouraging investments in agricultural assets and technologies, such as irrigation systems, quality seeds, and fertilizers, can boost agricultural productivity and diversify crop production. This can lead to increased availability of nutritious foods, contributing to improved dietary diversity and nutritional outcomes in rural areas. Talking about assets, supporting asset-building initiatives, such as asset and livestock transfers which are increasingly incorporated in many poverty graduation programs are crucial in stimulating the consumption of nutritious and healthy foods. By enhancing households’ economic resilience and capacity to purchase diverse food items, these initiatives can contribute to improved dietary diversity and nutrition security.

Livestock and other assets could represent important aspects of rural wealth and prosperity and contribute to addressing poverty and food insecurity especially in the framework of poverty graduation and social protection schemes that involve livestock transfer and donation programs19. These asset transfer and livestock donation programs are important for improved nutrition through dietary diversity where households consume more animal sourced foods such as meat43. When these transfers are gendered and directed to women, they become productive as they increase meat and milk consumption while also increasing income with ensuing impacts on the consumption of eggs and fresh vegetables44. In Zambia, a livestock gift program where dairy cows, draft cattle and goats were distributed have been shown to increase dietary diversity and consumption expenditure39. Beyond food consumption and nutrition implications, these livestock transfers are productive, creating jobs for the poor, building more assets, and improving resilience while getting households out of poverty45,46.

Furthermore, given the gendered insights about the importance of women in inducing the consumption of nutritious and healthy foods, it would be important to develop and implement gender-responsive policies. These policies could address different tenets of women’s empowerment, access to resources, and participation in decision-making processes related to food and nutrition, as they are significant entry points to address and reduce gender disparities in food consumption patterns. Ensuring equitable access to assets and opportunities for women can lead to improved nutrition outcomes for both women and their families. Relatedly and although not directly implied by our results, it would be important to invest in nutrition education and various knowledge awareness campaigns. These programs can greatly disseminate the importance of diverse diets, and adherence to dietary guidelines and empower households to make informed food choices. These campaigns should target both men women and effectively spread responsibility. By incorporating these practical policy implications into targeted programs and initiatives, policymakers, government agencies, and stakeholders can work towards addressing the challenges of food insecurity, promoting healthy eating practices, and improving nutrition outcomes in Zambia.

Conclusion

This study examines the relationship between rural wealth and the consumption of healthy and nutritious foods in Zambia. Specifically, it investigates how household wealth, measured through the ownership of productive assets and livestock, influences dietary diversity and adherence to the Zambian FBDGs. Employing a two wave panel data from the Rural Agricultural Livelihoods Survey and employing different data estimators, we report several key results. First, we establish a positive association between livestock and asset ownership with dietary diversity based on both the household dietary diversity score and the food based dietary guidelines. Second, we show that individual food groups in the HDDS and FBDGs such as fruits, vegetables, dairy, legumes, and fish respond differently to livestock and asset increases.

Third, we further observe that in response to wealth increases, households transition from starchy to protein-rich foods. Fourth, we show suggestive evidence that all livestock (cattle, goats, and chicken) offer nutritional gains but livestock size matters with cattle and goats offering more gains than poultry. Fifth, we show that the food consumption and nutritional gains of assets and livestock are gendered as they translate to higher gains for women. Finally, and related to the above, in households where women are the main decision makers, the nutritional gains of asset and livestock ownership are larger. Overall, this paper improves the understanding of how rural wealth influences food choices, dietary diversity, and nutrition outcomes, highlighting the importance of considering assets and livestock as key entry points for stirring the consumption of nutritious and healthy foods.

Like every analysis, we have some limitations of the study. Future studies may want to address and move in the direction of these limitations. First, our study focuses entirely on rural Zambia. It would have been interesting to look at urban regions and their food environments where the dynamics may be somewhat different. The second limitation comes from our measures of dietary diversity. We have used both HDDS12 and HDDS9 as well as the context-specific FBDGs but for all these, we just examined the food groups with little or no hint at the quantities consumed which is a better proxy for nutrition adequacy. Future work may want to use more detailed and disaggregated data to assess the guidelines in more depth. Finally, we refer to our estimates as correlations given that we are not able to control all forms of endogeneity especially reverse causality.

Data availability

The datasets used for the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Evaluation of FAO’s contribution to Sustainable Development Goal 2 – End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Aug 20]. Available from: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/f3a8d0e3-460b-4683-8cfd-7d8cbd716cd5/content

Anderson, W. et al. Violent conflict exacerbated drought-related food insecurity between 2009 and 2019 in sub-Saharan Africa. Nat Food [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Aug 20];2(8):603–615. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s43016-021-00327-4

Hasegawa, T. et al. Extreme climate events increase risk of global food insecurity and adaptation needs. Nat Food [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 20];2(8):587–95. (2021). Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s43016-021-00335-4

Jr. Tabe-Ojong, M. P., Nshakira-Rukundo, E. & Haile Gebrekidan, B. COVID-19 and food insecurity in Africa: A review of the emerging empirical evidence. Eur Rev Agric Econ [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 20];50(3):853–78. (2023). Available from: https://academic.oup.com/erae/article-abstract/50/3/853/7091560

United Nations. The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2024. 51. (2024) p.

FAO. Zambia Food Based Dietary Guidelines. [cited 2025 Aug 20]; (2024). Available from: https://policycommons.net/artifacts/2046119/zambia-food-based-dietary-guidelines/2798553/

Razzaq, A., Qin, S., Zhou, Y., Mahmood, I. & Alnafissa, M. Determinants of financial inclusion gaps in Pakistan and implications for achieving SDGs. Sci Rep [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 20];14(1):13667. (2024). Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-024-63445-6

Fadare, O., Srinivasan, C. & Zanello, G. Livestock diversification mitigates the impact of farmer-herder conflicts on animal-source foods consumption in Nigeria. Food Policy [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 20];122:102586. (2024). Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0306919223001847

Ameye, H., Bachewe, F. N. & Minten, B. The rising price of nutritious foods: the case of Ethiopia. Glob Food Secur [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 20];31:100582. (2021). Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211912421000900

Kidane, D. & Woldemichael, A. Does inflation kill? Exposure to food inflation and child mortality. Food Policy [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 20];92:101838. (2020). Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0306919220300221

Mulenga, B. P., Ngoma, H. & Nkonde, C. Produce to eat or sell: Panel data structural equation modeling of market participation and food dietary diversity in Zambia. Food Policy [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 20];102:102035. (2021). Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0306919221000130

Bai, Y., Alemu, R., Block, S. A., Headey, D. & Masters, W. A. Cost and affordability of nutritious diets at retail prices: evidence from 177 countries. Food Policy [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 20];99:101983. (2021). Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0306919220301871

Hirvonen, K., Bai, Y., Headey, D. & Masters, W. A. Affordability of the EAT–Lancet reference diet: a global analysis. Lancet Glob Health [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Aug 20];8(1):e59–66. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/langlo/article/PIIS2214-109X(19)30447-4/fulltext?amp=1

Ryckman, T., Beal, T., Nordhagen, S., Chimanya, K. & Matji, J. Affordability of nutritious foods for complementary feeding in Eastern and Southern Africa. Nutr Rev [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 20];79(Supplement_1):35–51. (2021). Available from: https://academic.oup.com/nutritionreviews/article-abstract/79/Supplement_1/35/6164906

Abdelmenan, S. et al. The social stratification of availability, affordability, and consumption of food in families with preschoolers in Addis Ababa; the EAT Addis Study in Ethiopia. Nutrients [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Aug 20];12(10):3168. (2072). Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/-6643/12/10/3168.

Baye, K. & Kennedy, G. Estimates of dietary quality in infants and young children (6–23 mo): Evidence from demographic and health surveys of 49 low-and middle-income countries. Nutrition [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 20];78:110875. (2020). Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0899900720301581

Kubuga, C. K. & Aguree, S. Adherence to daily food-based dietary recommendations and its association with anemia among Ghanaian women. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2025 Feb 20 [cited 2025 Aug 20];25(1):712. Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-025-21961-8

Liguori, J. et al. Individual-level drivers of dietary behaviour in adolescents and women through the reproductive life course in urban Ghana: A Photovoice study. Matern Child Nutr [Internet]. Oct [cited 2025 Aug 20];18(4):e13412. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/ (2022). https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.13412

Collishaw, A., Janzen, S., Mullally, C. & Camilli, H. A review of livestock development interventions’ impacts on household welfare in low-and middle-income countries. Glob Food Secur [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 20];38:100704. (2023). Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211912423000342

Baye, K. & Yaregal, Z. The Global Diet Quality Score predicts diet quality of women of reproductive age in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Br J Nutr [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 20];130(9):1573–9. (2023). Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/british-journal-of-nutrition/article/global-diet-quality-score-predicts-diet-quality-of-women-of-reproductive-age-in-addis-ababa-ethiopia/D3492272CAD148D9F588CD90A3DCC9B9

van der Meulen Rodgers, Y. & Kassens, A. L. Women’s asset ownership and children’s nutritional status: evidence from Papua New Guinea. Soc Sci Med [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2025 Aug 20];204:100–7. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277953618301382

Wantchekon, L. & Riaz, Z. Mobile technology and food access. World Dev [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 20];117:344–56. (2019). Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305750X19300129

Kennedy, G., Ballard, T. & Dop, M. Guidelines for measuring household and individual dietary diversity [Internet]. FAO; [cited 2025 Aug 20]. (2011). Available from: https://openknowledge.fao.org/items/9bb3c3ce-66cf-4b00-b460-de29822bbd75

Tabe Ojong MPJr, Hauser, M. & Mausch, K. Does Agricultural Commercialisation Increase Asset and Livestock Accumulation on Smallholder Farms in Ethiopia? J Dev Stud [Internet]. 2022 Mar 4 [cited 2025 Aug 20];58(3):524–44. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2021.1983170

Azzarri, C., Zezza, A., Haile, B. & Cross, E. Does Livestock Ownership Affect Animal Source Foods Consumption and Child Nutritional Status? Evidence from Rural Uganda. J Dev Stud [Internet]. 2015 Aug 3 [cited 2025 Aug 20];51(8):1034–59. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2015.1018905

Hoddinott, J., Headey, D., Dereje, M. & Cows Missing Milk Markets, and Nutrition in Rural Ethiopia. J Dev Stud [Internet]. 2015 Aug 3 [cited 2025 Aug 20];51(8):958–75. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2015.1018903

Aragón, F. M., Oteiza, F. & Rud, J. P. Climate change and agriculture: Subsistence farmers’ response to extreme heat. Am Econ J Econ Policy [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Aug 20];13(1):1–35. Available from: https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/pol.20190316

Carter, M. R. & Lybbert, T. J. Consumption versus asset smoothing: testing the implications of poverty trap theory in Burkina Faso. J Dev Econ [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2025 Aug 20];99(2):255–64. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304387812000077

Verpoorten, M. Household coping in war-and peacetime: Cattle sales in Rwanda, 1991–2001. J Dev Econ [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2025 Aug 20];88(1):67–86. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304387808000072

Jahnke, H. E. & Jahnke, H. E. Livestock production systems and livestock development in tropical Africa [Internet]. Vol. 35. Kieler Wissenschaftsverlag Vauk Kiel; 1982 [cited 2025 Aug 20]. Available from: https://appec-h.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Livestock-production-systems.pdf

Wooldridge, J. M. Correlated random effects models with unbalanced panels. J Econom [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2025 Aug 20];211(1):137–50. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304407618302392

Mundlak, Y. On the pooling of time series and cross section data. Econom J Econom Soc [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 20];69–85. (1978). Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1913646

Brockington, D. Persistent peasant poverty and assets. Exploring dynamics of new forms of wealth and poverty in Tanzania 1999–2018. J Peasant Stud [Internet]. 2021 Jan 2 [cited 2025 Aug 20];48(1):201–20. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2019.1658081

Alderman, H., Gilligan, D. O., Leight, J., Mulford, M. & Tambet, H. The role of poultry transfers in diet diversity: A cluster randomized intent to treat analysis. Food Policy [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 20];107:102212. (2022). Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0306919221001913

Fafchamps, M., Udry, C. & Czukas, K. Drought and saving in West Africa: are livestock a buffer stock? J Dev Econ [Internet]. 1998 [cited 2025 Aug 20];55(2):273–305. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304387898000376

Nguyen, G. T. H., White, B. & Ma, C. When Faced with Income and Asset Shocks, Do Poor Rural Households in Vietnam Smooth Food Consumption or Assets? J Dev Stud [Internet]. 2019 Sept 2 [cited 2025 Aug 20];55(9):2008–23. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2018.1528350

Abate, G. T. et al. Digital tools and agricultural market transformation in Africa: Why are they not at scale yet, and what will it take to get there? Food Policy [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 20];116:102439. (2023). Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0306919223000374

Alary, V., Corniaux, C. & Gautier, D. Livestock’s contribution to poverty alleviation: how to measure it? World Dev [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2025 Aug 20];39(9):1638–48. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305750X11000271

Jodlowski, M., Winter-Nelson, A., Baylis, K. & Goldsmith, P. D. Milk in the data: food security impacts from a livestock field experiment in Zambia. World Dev [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 20];77:99–114. (2016). Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305750X15001904

Mullally, C., Rivas, M. & McArthur, T. Using Machine Learning to Estimate the Heterogeneous Effects of Livestock Transfers. Am J Agric Econ [Internet]. 2021 May [cited 2025 Aug 20];103(3):1058–81. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/https://doi.org/10.1111/ajae.12194

Tabe-Ojong, M. P. J. Context matters: Oil palm production and women’s dietary diversity in the tropical forest of Cameroon. J Agric Econ [Internet]. 2024 Feb [cited 2025 Aug 20];75(1):323–40. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/https://doi.org/10.1111/1477-9552.12559

Collier, P. & Lal, D. Why poor people get rich: Kenya 1960–1979. World Dev [Internet]. 1984 [cited 2025 Aug 20];12(10):1007–18. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0305750X84900263

Rawlins, R., Pimkina, S., Barrett, C. B., Pedersen, S. & Wydick, B. Got milk? The impact of Heifer International’s livestock donation programs in Rwanda on nutritional outcomes. Food Policy [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 20];44:202–13. (2014). Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0306919213001814

Ayele, Z. & Peacock, C. Improving access to and consumption of animal source foods in rural households: the experiences of a women-focused goat development program in the highlands of Ethiopia. J Nutr [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 20];133(11):3981S-3986S. (2003). Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022316623025646

Gulesci, S. Poverty alleviation and interhousehold transfers: evidence from BRAC’s graduation program in Bangladesh. World Bank Econ Rev [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Aug 20];35(4):921–49. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/wber/article-abstract/35/4/921/5999477

Phadera, L., Michelson, H., Winter-Nelson, A. & Goldsmith, P. Do asset transfers build household resilience? J Dev Econ [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2025 Aug 20];138:205–27. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304387818304772

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MPTO and SMEB conceptualized and developed the study. They then sought for data and MPTO undertook the formal analysis. Together, they wrote the manuscript with RMM who was also very instrumental in getting the data across. All authors revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tabe-Ojong, M., Eke Balla, S. & Mofya-Mukuka, R. Rural wealth is associated with the consumption of nutritious and healthy foods in Zambia. Sci Rep 16, 593 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30216-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30216-w