Abstract

Past studies show that Graphene Oxide (GO) enhances the structural properties of cement composites. However, GO reduces its chemical characteristics with ageing. This study determines the effects of the age of commercial and laboratory-produced GO on cementitious composites. The study considered GO of up to 35 weeks of age, and specimens were chemically characterised using various techniques. The ageing effects were evaluated using consistency, initial setting time, compressive strength, splitting tensile strength, and water absorption. The composite’s thermal resistance was also tested. GO was found to have a shelf life of 13 weeks from production to achieve favourable results. The morphology of the cement mortar was studied to determine the reason for the change in performance with GO age. This study confirms that the carbon-to-oxygen ratio (C/O) and the disorder of graphene oxide sheets (ID/IG ratio), along with the number of GO layers, govern the performance of GO-incorporated cement composites. Both ratios increase with GO age. Aged GOs in mortar increased the mean pore radius and reduced the surface area. Mortar samples with aged GOs have ettringite peaks, while early-age GO-containing samples lack ettringite peaks. Despite reduced mechanical performance with age, all mortar samples remained thermally stable at higher temperatures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High-Performance Cementitious Composites (HPCC) incorporating various materials as admixtures and additives have received considerable attention over several decades due to their favourable structural properties1,2,3. In recent years, the focus has shifted to the potential of nanotechnology in construction and building materials, exploiting the unique properties of nanomaterials to enhance the performance of cementitious composites. Such composites incorporating nanomaterials, which exhibit enhanced properties due to modified morphology, have been reported in the literature4,5,6,7,8. Pozzolanic nanomaterials such as nano-silica and nano-alumina are composed solely of SiO2 and Al2O3, respectively, and are involved in hydration reactions. They contributed to excess and denser production of calcium silicate hydrates (CSH) and calcium aluminate hydrates (C-A-H), respectively8,9. Denser hydrates reduce the micropores in the matrix, increasing the fracture energy required for failure, but unfortunately, they also elevate brittleness4,8,9. Non-pozzolanic nanomaterials such as graphene oxide (GO), carbon nanotubes, and titanium oxide can form excess hydration products with an organized crystalline structure, thereby enhancing the performance of cementitious composites10,11,12,13.

Graphene Oxide (GO), a nanosheet, has attracted the attention of researchers in recent years due to its ability to enhance the properties of cement composites10,13,14. The incorporation of GO into cement composites modified the morphology of the hardened cement matrix, thereby altering its properties. Oxygen functional groups of GO act as a platform and nucleation sites to attract Ca2 + ions in cement and assist in the denser formation of CSH and Ca(OH)210,13. The denser GO-containing cement matrix consists of more micropores and fewer mesopores. Additional hydration products enhance the compressive and tensile strengths, as extra energy is required for failure. The consistency and setting times of cement pastes with GO decrease compared to pastes without GO13,15. However, adding GO into an alkaline medium agglomerates the GO nanosheets, leading to a non-uniform nanomaterial dispersion. Hence, to overcome GO agglomeration and improve workability, GO is sonicated with polycarboxylate ether (PCE)- based admixtures before being added to the cement mixture13,16,17. The presence of GO in cement composites also improves durability properties such as water absorption, water sorptivity, resistance to combined acid and Sulphur attack, chloride penetration18,19,20,21, and residual compressive strengths at higher temperatures22. However, the repeatability of durability properties remains questionable, as only a few studies have been reported.

Past studies on GO-enhanced cementitious composites have used GO with a carbon-to-oxygen (C/O) ratio of almost 1.90, demonstrating optimal enhancement in all structural properties with the addition of 0.03% of dry laboratory- or commercial-grade GO relative to the weight of cement13,15. However, a decrease in oxygen functional groups is recorded with ageing, increasing the C/O ratio while the average interlayer distance of GO reduces. Moreover, the ratio of the D-band intensity to the G-band intensity (ID/IG) increases with ageing, indicating an increase in defect density due to the desorption of oxygen functional groups23,24. Yet, in a highly acidic aqueous medium, the oxidation of GO is slightly improved over the long term25.

Grounded in past studies of GO ageing, the number of nucleation sites that augment the formation of hydration products decreases with a decrease in oxygen functional groups. Hence, a reduction in the strength of GO-enhanced cementitious composites can be expected due to the reduced hydration products. Due to limited studies on GO stability, the effects of GO age and reduced characteristics on the properties and morphology of cement composites remain poorly understood and warrant in-depth research. This study, therefore, aims to fill this gap and focuses on the morphology and mechanical properties of cement mortar incorporating commercial and laboratory-produced GO at different ages (4 to 35 weeks after production). It is expected that this research will yield important results that significantly impact the manufacture of GO-enhanced cementitious composites and their application in construction.

GO production in laboratories typically uses deionised or distilled water, which is not economical from a commercial perspective13,26,27. Since the majority of water consumption occurs during the cleaning of graphene oxide (GO), this study will employ tap water for the purification of laboratory-synthesized GO as a cost-effective alternative, while maintaining consistency with the production methods utilized by a commercial GO manufacturer in Sri Lanka. As the tap water is used only after oxidation and quenching, its ions are not expected to chemically react with GO. The GOs were characterized using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), X-ray powder diffraction (XRD), and Raman spectroscopy, along with scanning electron microscope (SEM) imaging. The impact of GO age on the consistency of cement paste and initial setting time was studied. The mechanical properties—compressive strength, indirect tensile strength, and density—of cement mortar were measured at 7 and 28 days, with the optimum GO content. In addition, the expiry periods of commercial and laboratory-produced GO were identified based on the compressive and tensile strengths. Cement mortars of varying ages were also tested for water absorption resistance. The results obtained are supported by the morphological study of cement mortar via XRD, Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) analysis, Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), and SEM with Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX).

Methodology

Materials

Portland Pozzolana Cement (PPC) of grade 42.5 adhering to ASTM C595/C595M-1628 and oven-dried river sand passing 4.75 mm sieve size adhering to ASTM C 144 -1829 were used in cement mortar at a weight ratio of 1:3. Poly Carboxylic Ether (PCE) based superplasticizer and tap water conforming to ASTM C-494/C494M-0830 and ASTM C1602/C1602M -1831, respectively, were used in dispersing the GO uniformly in the cement mix. The cement and PCE used in this study were within their expiry period. Hence, there is no ageing effect on these materials. It is also not the standard practice to use these materials beyond their expiry period. The commercial GO was obtained from commercial GO manufacturers in Sri Lanka and will hereinafter be abbreviated as CGT-GO. All chemicals required for the laboratory synthesis of GO were procured from suppliers in Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka is well known for high-quality pure graphite32. The 99% carbon grade graphite powder with a particle size of 40 μm was obtained in Sri Lanka.

Synthesis of GO

In addition to the commercial GO (CGT-GO), this study used laboratory-synthesised GO prepared at the chemical laboratory at the Sri Lanka Institute of Information Technology. Viscous GO suspension was prepared using a modified version of Tour’s method33. Initially, the graphite powder was mixed with potassium permanganate (KMnO4) at a weight ratio of 1:3. Separately, an acid mixture consisting of concentrated phosphoric acid and concentrated sulfuric acid at a volume ratio of 1:9 was placed in an ice bath. Next, the acid mixture was transferred to the powder mixture and stirred at 550 rpm, maintaining the reaction temperature below 50 °C for 24 hours. The mixture was cooled to below 10 °C with ice, and after 12 hours, the excess KMnO4 was removed by reacting with 3 ml of 30% hydrogen peroxide. The final mixture was repeatedly washed with tap water until the supernatant was free of sulphate ions and the GO suspension was slightly acidic (pH 5.0–6.0)34,35. Using tap water for washing after the oxidation and quenching steps may introduce low levels of residual ions into the GO suspension. However, these ions are not expected to chemically react with graphene oxide36. Then, the suspension was sonicated for one hour at 60 kHz, followed by stirring at 550 rpm for 30 minutes to form a uniform GO paste. The moisture content of the GO paste was determined by heating it in an oven at 100 °C for 24 hours, after which the dry content of the GO in the paste was calculated. All materials used to synthesise the laboratory GO were within their expiry periods.

Cement paste and mortar preparations and testing

Consistency and setting times were determined using cement paste. As per ASTM standard, 650 g of Ordinary Portland cement and 200 g of potable water were used to obtain the normal consistency (10 ± 1 mm)37,38. The overall water weight was adjusted based on the GO suspension’s water content. The GO concentration was set to 0.03% by weight of cement, based on a previous study that investigated the effects of GO concentration over the range 0–0.04% and determined its optimal value13. The cement paste was mixed per the ASTM standards to obtain normal consistency. Next, the cement paste was placed in a moist cabinet at 25 °C with humidity above 95%. The initial setting time of the paste was measured when it reached 25 mm, and the final setting time was measured when the circular impression was not formed on the cement paste’s surface.

Cement mortar comprising a cement-to-river sand (CM/RS) ratio of 1:3 and a water-to-cement (W/CM) ratio of 0.6, with 0.03% GO paste content with respect to the weight of cement, was prepared at a laboratory environmental temperature of 28 ± 2 °C29,39. The river sand was sieved through a 4.75 mm sieve, oven-dried at 110 °C for 24 h, and cooled to room temperature for 12 hrs before casting29. Potable water of 26±1 °C was used to mix mortar. The PCE superplasticiser (0.6 L/100 kg of cement) was sonicated with GO at 0.03% by dry weight relative to the cement before adding it to the cement paste and mortar mixes. This optimal GO ratio is based on a previously conducted comprehensive study by the authors examining the effect of the GO ratio on the mechanical and microstructural properties of GO-enhanced cement mortar13.

Cement mortar mix was cast into moulds of 50 mm x 50 mm x 50 mm cubes and 80 mm x 160 mm cylinders40,41. The casting of cylinders and cubes was executed per the ASTM standards, ensuring constant compaction energy employing a concrete vibrating table. The specimens were detached after 24 hours and immersed in saturated lime water at 3.0 g/L concentration at 26 ± 1 °C42. The compressive strength of the cube samples was then tested at 7 and 28 days, while the cylinders used to determine splitting tensile strength were tested at 28 days40,41. Despite compression being the primary property, the splitting tensile strength indicates the mortar’s resistance to cracking and its ability to withstand tensile stresses, which control the initiation and propagation of structural failures. The use of mortar specimens isolates binder–matrix effects and minimizes the variability introduced by coarse aggregates. This approach enables a more precise interpretation of binder-level tensile mechanisms. Previous studies43,44 have shown that trends observed at the mortar scale correlate well with, and can often be extrapolated to, the behaviour of concrete. The samples were loaded at a rate of 0.3 kN/s using a universal testing machine (UTM), and the load-displacement curve was obtained.

The durability properties, such as water absorption and tensile and compressive strengths at higher temperatures (200 to 400 °C), were tested. The 28-day-aged cubes were oven-dried at 110 °C for 24 hours before being used in the water absorption test. The weight was measured after the cubes’ temperature was reduced to ambient (26 ± 1 °C). Then, the samples were placed in a water uptake container, and their weights were measured after 24 hours. Water absorption in grams per 100 cm2 was determined by measuring the change in weight over time45. The average test values in the results section are the mean of three values with a standard deviation of less than 10%.

Characterization

GOs of different ages were characterised using various techniques. Fourier-transform infrared spectra (FTIR) to study the functional groups present in the samples. For X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) was used to study the surface chemistry of the composite materials. X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) was performed using Cu K (λ = 0.154 nm) radiation, varying 2θ from 5 to 80 at a scan speed of 2/min to study crystallography. A Raman microscope spectrophotometer was used to confirm the structure proposed by XRD.

SEM equipped with an EDS system were used to collect images and elemental composition to study the morphology of the samples. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was conducted in air. The samples used for BET analysis were degassed at 200 °C for 10 hours to determine their surface area and pore volume.

Results

FT-IR analysis

Based on Fig. 1, the FT-IR spectra of freshly produced CGT and laboratory-produced GO (Lab-GO) display similar bonding and functional groups with variations in intensity. The broadband peak centred at about 3254 and 3261 cm−1 represents the O-H stretching of alcohol in CGT-GO and Lab-GO, respectively. The sharp peaks at 1616 and 1620 cm−1 of those two samples are attributed to conjugated C=C bonds of alkenes. CGT-GO showed more intense peaks at 1039 cm−1 and 1163 cm−1, corresponding to C–O stretching in aldehyde, carboxylic acid, ester, and ketone groups. The stretching frequency of C–O was observed at 1064 cm-1 in Lab-GO, but the frequency at 1039 cm-1 was not observed. The peaks at 1718 and 1730 cm-1 in CGT-GO and Lab-GO, respectively, are attributed to the C=O stretching frequency. Based on FT-IR observations, Lab-GO contains more C–H and C–C stretching, indicating more unaffected graphene layers than CGT-GO. However, grounded on the intensities of O–H and C=O bonds, CGT-GO contains more hydroxyl groups than carboxylic groups in Lab-GO.

FT-IR spectra of Lab-GO were collected at 4, 10, and 18 weeks after production (Fig. 2) to examine changes in functionality over time. Lab-GO was selected to acquire FT-IR spectra because the synthesis procedure and properties are well defined in the study and are the focus. The appearance of a peak at 2928 cm-1 with ageing (at 18 weeks) compared to 4 and 10 weeks indicates C-H stretching of the CH2 group, resulting from defects in the graphene layers. In addition, the O-H stretching frequency has shifted slightly to 3296 cm−1 (18 weeks) from 3279 cm-1 (4 weeks), indicating a weakening of the hydrogen bonding interaction with age, as evidenced by a shift towards a higher wavelength. The intensity of the cyclic alkene’s C=C stretching observed at 1624 cm−1 (4 weeks) decreases with age. Likewise, the intensity of the C-O stretching of alcohol at 1072 cm-1 (4 weeks) also shows a drop with age.

XPS analysis

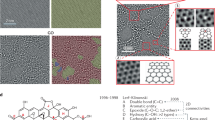

Figures 3 and 4 illustrate the XPS spectra of C1s and O1s of freshly manufactured Lab-GO and CGT-GO, respectively. The C1s spectrum of Lab-GO (Fig. 3a) is deconvoluted to four peaks at 284.80, 285.70, 287.70, and 289.15 eV representing sp2 hybridized C–C, sp3 hybridized C–C, C–O–C, and COOH, respectively. The same chemical environments of C were observed in CGT-GO (Fig. 4a), where the corresponding peaks appeared at 284.50, 285.35, 287.40, and 289.10 eV, respectively. The higher resolution XPS spectrum of O1s of Lab-GO (Fig. 3b) is deconvoluted to two peaks at 532.75 and 533.60 eV, which are attributed to C=O and C–O, respectively. In contrast, the chemical states were observed in the higher-resolution O1S spectrum of CGT-GO, which appeared at 532.60 and 533.60 eV, respectively (Fig. 4b).

Based on the atomic percentages of carbon and oxygen, the mean carbon-to-oxygen (C/O) ratio of Lab-GO was 1.802, while the C/O ratio of CGT-GO was 1.896 at 18 weeks of age. Surface bonds identified by XPS are consistent with the FT-IR results and further confirm the presence of functional groups (esters, ketones, aldehydes/carboxylic acids) in GO. The average carbon-to-oxygen (C/O) ratios vary with the ageing of the lab and CGT-produced GOs, as presented in Table 1. The C/O ratio increased by 13.5% and 14.9% with Lab and CGT-GO at 18 weeks compared to 4 weeks. C/O ratios increase with age in both GOs, as GO reduces with time when exposed to normal environmental conditions for longer periods. On average, the reduction rates for both GOs are similar. Overall, the increase in the C/O ratio with ageing for both GOs reflects a continuous reduction under ambient conditions, probably due to loss of oxygen functional groups. The XPS confirms GOs’ functional groups; however, the synthesis method affects the initial oxidation state, and long-term reduction is primarily governed by environmental exposure.

GO is known to enhance the cement strength via several mechanisms. Oxygen functional groups on GO serve as nucleation sites, enhancing the formation of more homogeneous, regular calcium silicate hydrate. Further, GO fills the nanoscale pores in the porous network of cement, leading to a less porous and denser cement material. The high surface area and mechanical strength of GO deflect the microcracks, inhibiting their propagation and thus improving the strength and toughness of cement. However, an optimal dose of oxygen would play the crucial role. High oxygen content leads to strong interactions with calcium hydroxide, which causes the aggregation of GO, which retards the overall strength, whereas low oxygen content is less effective in strengthening cement, resulting in poor interaction with cement due to its low chemical compatibility and poor dispersibility in water.

Raman spectroscopic analysis

The stacked Raman spectra in Figs. 5 and 6 show the variation in D, G, and 2D bands, and their intensities, with the ageing of Lab-GO and CGT-GO, respectively. The G and D bands appear around 1340 cm-1 and 1590 cm-1, respectively, and the wide 2D band occurs at about 2700 cm-1. The G band is the primary mode in all graphene-based materials, corresponding to carbon-bond stretching in sp2 rings and chains. The degree of disorder is observed via the D band, which arises from defects and gaps in sp2 carbon rings formed by sp3-hybridised carbon resulting from oxidation. The 2D band arises from second-order Raman scattering.

The ageing of Lab-GO and CGT-GO alters the ratio of the D peak to the G peak (ID/IG). At 4, 10, 18, and 28 weeks, the average ID/IG ratios of Lab-GO are 0.932, 0.943, 1.048, and 1.263, respectively. While the ID/IG ratios of CGT-GO are 1.076 and 1.142 at 7 and 13 weeks, respectively, the increase in the ID/IG ratio suggests that the structural disorder of GO has increased with age. A rise in the degree of disorder due to the reduction (removal of oxygen) when exposed to environmental conditions. Sunlight and ultraviolet radiation can reduce GO, even if it is placed indoors. The ratio of the intensities of the 2D peak and the G peak (I2D/IG) reflects the GO layer thickness. The I2D/IG ratio of Lab-GO ranges from 0.046 to 0.073, while the I2D/IG ratio of CGT-GO lies between 0.045 and 0.096. I2D/IG ratios of 0.07 represent multilayered GO. Hence, both Lab-GO and CGT-GO used in the experiments are multilayered.

XRD analysis

XRD patterns were acquired to study the crystallography of the synthesized materials. Figure 7 shows the XRD patterns of Lab and CGT-GO. Both GOs display a strong peak around 8–12° (2θ) with a lower full width at half maximum (FWHM), indicating higher crystallinity. The FWHM of Lab-GO is 0.898, while that of CGT-GO is 0.952, indicating that Lab-GO is slightly more crystalline than CGT-GO. The corresponding crystallite sizes are 9.28 nm and 8.76 nm, respectively. The interlayer spacing (d) between the GO layers was calculated using Bragg’s law equation (Eq. 1). The spacing between the Lab-GO sheets was found to be 0.841 nm, while that of the CGT-GO sheets was calculated to be 0.778 nm. This nanoscale spacing indicates that several GO layers are stacked (multilayered), as shown by Raman spectroscopy.

where λ is the wavelength of the bombarded X-ray beam (0.154 nm), Ɵ is the diffraction angle, and d is the interlayer spacing between the GO sheets.

Properties of cement paste and mortar with aged GO consistency, setting times and densities

The addition of GO affects the rheological, mechanical, and durability properties of cement paste and mortar. Figure 8 illustrates the consistency of HBC cement pastes containing 0.03% Lab and 0.03% CGT-GO of different ages. In general, consistency increased for GOs at lower ages and was similar to that of the control at higher ages for CGT-GO- and Lab-GO-incorporated pastes. The consistency of pastes thickened by 19.2% and 21.2% with 9-week-old CGT-GO and 12-week-old Lab-GO, respectively, while those of 18-week-old CGT-GO and 28-week-old Lab-GO increased only by 5.8% and 1.9%, respectively. For 18-week-old CGT-GO and 28-week-old Lab-GO, the results were closer to the control value of 8.7 mm. Due to ageing, the C/O ratios vary, impacting the number of nucleation sites present and the amount of water absorbed during hydration. At higher C/O ratios, as in 9 and 12 weeks of GO, the functional groups present were higher, leading to greater and quicker hydration reactions. However, at lower C/O, although some oxygenated groups are present, the increased defects and non-uniform attachment of functional groups on graphene surfaces have slightly decreased the consistency compared to that obtained at lower ages.

Figure 9 displays the impact of two different ages of Lab and CGT-GO solutions on the initial setting times of HBC cement paste. The 9- and 12-week GOs decreased the initial setting times by 6.6% and 7.6%, respectively, while the 28-week GOs increased the setting time only by 0.64%. The 18-week CGT-GO reduced the setting time by only 1.1%. The 9-week CGT-GO and 12-week Lab-GO have more oxygenated groups than those of 18 and 28 weeks, resulting in more nucleation sites and an enhanced hydration process. At long-term ageing (18 and 28 weeks for CGT and Lab-GOs, respectively), the increased defects on GO sheets and fewer nucleation sites result in fewer hydration products, leading to setting times similar to those of the control.

The average wet and dry densities of control cement mortar are 2235 kg/m3 and 2092 kg/m3, respectively. Figure 10 illustrates the change in wet and dry densities of Lab and CGT-GO-added cement mortar (W/CM 0.6) at different ages of GO. In both types of GO, density decreases with age. Compared with the control sample, the maximum increases in wet and dry mortar densities with Lab-GO were 11.1% and 8.6%, respectively, and were observed at 4 weeks. At the same age, the mortar with CGT-GO showed wet and dry densities that were improved by 9.7% and 9.1%, respectively. The lowest densities were observed at 35 weeks, when the dry density of mortar with CGT-GO remained 0.6% above the control, while the dry density of mortar with Lab-GO decreased by 0.1% compared to the control.

Compressive and tensile strength of cement mortar

Table 2 shows that the compressive strengths decrease with increasing GO age. The 7-day and 28-day strengths of Lab-GO mortar are above the control until the 15th week by 0.76% and 3.86%, respectively. Till about 15 weeks, the compressive strengths (28 days) are about the same for both Lab and CGT-GOs. However, afterwards, the performance of Lab-GO dropped below the control (by 26% at 35 weeks), while the CGT-GO-added mortar’s 7-day and 28-day compressive strengths reached similar levels to the control.

Table 2 presents the 7-day and 28-day compressive strengths of Lab GO and CGT GO dispersions added to cement mortar at different ages, along with their standard deviations. It is evident that the compressive strength decreases with increasing GO age, but indicates a long-term asymptotic value. The 7-day and 28-day strengths of Lab GO mortar are above the control until the 15th week by 0.76% and 3.86%, respectively. Till about 15 weeks, the compressive strengths (28 days) are about the same for both Lab and CGT GOs. However, after 35 weeks, the performance of Lab GO dropped below the control (by 26%), while the CGT GO-added mortar’s 7-day and 28-day compressive strengths reached levels similar to those of the control.

Figure 11 shows that an exponential decay model fitted the experimental data well, with R2 values of 0.95 for the Lab GO 28-day and CGT GO 7-day samples, and 0.86 for the CGT GO 28-day samples. The Lab GO 7-day data showed a weaker fit due to experimental variability, yet provided critical insights into GO ageing behavior. Overall, Lab GO showed superior initial performance but faster degradation than CGT GO, which maintained a reasonable enhancement throughout the study period compared to the control.

The exponential decay model (y=a + b*e(-ct)) fitted well with the experimental data, with R2 of 0.97 for the CGT GO 7-day, 0.87 for the Lab GO 28-day, and 0.82 for the CGT GO 28-day samples, as shown in Fig. 11. The Lab GO 7-day data showed a weaker fit due to experimental variability, yet provided critical insights into GO ageing behavior. Overall, Lab GO showed superior initial performance but faster degradation compared to CGT GO, which maintains a reasonable enhancement throughout the study period, compared to the control.

The Lab GO 28-day showed an exceptional early-age performance with an initial enhancement of 42.10 MPa, but degrades rapidly, as indicated by the high decay rate resulting in a short half-life of 5.8 weeks. The lower asymptotic strength (18.5 MPa), which is below that of the control, suggests that the age of the GO has a detrimental effect on the strength of the mortar with Lab GO. The behavior of Lab GO 7-day further validates the findings with a lower asymptotic strength of 12.0 MPa, which is 35% below the 7-day control. In contrast, CGO GO 28-day demonstrated a more sustainable behavior with a strong initial enhancement (32.46 MPa). CGT-GO maintains a noticeable enhancement in compressive strength throughout the study period, without showing detrimental behavior when aged, with an asymptotic strength of 26.15 MPa, which is identical to the control. Similarly, CGT-GO 7-day exhibited a significant initial enhancement, which decreases gradually, maintaining a near-control asymptotic strength. The 15-week threshold identified in the study for Lab GO samples is further validated by model fit, as the strength drops near the control level for both samples.

The enhanced initial performance of Lab GO is due to the high density of functional groups that provide nucleation sites. However, this is countered by low functional group stability. These groups deteriorate with age, resulting in agglomeration that disturbs hydration kinetics, particularly at early ages, and forms weak places in the cement matrix. Conversely, CGT-GO maintained its effectiveness over the study period with noticeable enhancement in the mortar strength. The differences in the ageing behavior are due to the functional group stability of the CGT GO, with more stable oxygen-containing groups, and the ability of CGT GO to maintain cement hydration nucleation sites effectively with ageing.

The reason for the strength change lies in the number of oxygenated functional groups, as indicated by GO’s C/O ratio and its defect (ID/IG) ratio. Lab-GO is less stable than CGT-GO, leading to a significant drop in oxygen functional groups, as shown in Table 1 and discussed in the Section. 4.3. In addition, the intensity of defects increased in Lab-GO with time compared to CGT-GO, as noticed in the previous sections. More defects and fewer nucleation sites reduced compressive strength with age in both GOs. However, the CGT-GO-added mortar performed better than the Lab-GO-added mortar despite the strength drop, as the GO is more stable.

Figure 12 illustrates the splitting tensile strengths of Lab-GO and CGT-GO-added cement mortar with varying ages (4 weeks to 35 weeks). At early ages (until about 13 weeks), tensile strength is higher than the control, and after 13 weeks, it decreases. Compared to the control (W/CM 0.6) in Fig. 12, the maximum strength is observed at 10 weeks (by 60.7%) in CGT-GO, while with Lab-GO, the peak strength is observed at 13 weeks (by 52.9%). Greater improvement is observed when GO has more nucleation sites, resulting in more hydration products. Till the 15th week, the tensile strength of Lab-GO is above the control by 16.4%, and subsequently, the strength drops, reaching 1.07 MPa in the 35th week. However, despite the drop after 13 weeks with CGT-GO, the splitting tensile strength was still above the control by 2.14% (35th week). After 18 weeks, the performance of the CGT-GO-incorporated mortar remained almost constant. CGT-GO performed better than Lab-GO due to fewer defects and a more uniform arrangement of the material during production.

The radar chart (Fig. 13) presents the 28-day compressive strengths of cement mortars with varying C/S cement sand ratios (1:3, 1.25, 1.2, and 1:1.15) and the compressive strengths of Lab-GO and CGT-GO-added mortar at a C/S ratio of 1:3. With increasing cement content (or decreasing C/S ratio), the compressive strengths increase. The compressive strengths of 13-week GOs lie within the strengths of C/S ratios 1:2.5 and 1:2. However, the GO-added mortar was prepared with a C/S ratio of 1:3. The introduction of 0.03% Lab-GO and 0.03% CGT-GO in 1:3 (C/S) mortars obtained strengths similar to those obtained with C/S 1:2. Therefore, the addition of Lab-GO and CGT-GO decreased the amount of cement required to achieve the same strengths by almost 41.3% and 33.8%, respectively.

Water absorption of GO-enhanced cement mortar

Figure 14 displays the absorption rate (in %) of Lab and CGT-GO-incorporated samples relative to the control at different ages. Positive values indicate absorption above the control sample, while negative values indicate lower absorption. Compared with the control, the water absorption rate increased with GO ageing. The peak performance of mortar with Lab-GO is observed at 4 weeks (-20.69%), while the worst is at 35 weeks (12.33%). The absorption rate of CGT-GO-added mortar was higher than that of Lab-GO at 18, 28, and 35 weeks of age, as CGT-GO is more stable and less affected by ageing. The poor water absorption in aged GO-incorporated mortar is due to the porous cement matrix, leading to fewer hydration products. The formation of hydration products depends on the number of nucleation sites present on GO.

Strength of GO-enhanced mortar at high temperatures

The compressive strengths of mortar with Lab-GO (10 weeks) and CGT-GO (10 weeks) exposed to different temperatures (200 °C, 300 °C, and 400 °C) apart from room temperature (25 °C) for a period of two hours are displayed in Fig. 15. Overall, like the control mortar, the compressive strengths of all samples increase at 200 °C and decrease at 300 °C and 400 °C. At 200 °C, the strengths increased by 1.84% and 1.49%, in Lab-GO-and CGT-GO-added mortar, respectively. These results are observed because internal steam hydrates the unreacted cement particles, thereby improving compressive strength. At higher temperatures, such as 300 ºC and 400 ºC, strength reductions of 3.7% and 14.7% were observed for mortar with Lab-GO and 7.1% and 14.6% for CGT-GO—the decrease in strength results from the loss of hydration products.

Figure 16 shows the indirect tensile strength of 0.03% Lab-GO and CGT-GO-added mortar samples at different temperatures (200 ºC and 400 ºC) alongside the results for room temperature (25 ºC). All mortar samples with GO, similar to the control, decreased in tensile strength once exposed to higher temperatures. No increase in tensile strength is observed at 200 ºC, unlike the behaviour observed for compressive strength. At 200 ºC and 400 ºC, the splitting tensile strengths dropped by 34.1% and 39.1% for mortar with Lab-GO and by 25.3% and 40% for mortar with CGT-GO. The reduction in tensile strength is due to the loss of mass from the hydration products.

Morphological characterization of GO-added cement mortar

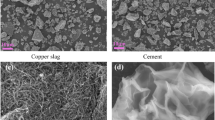

Figure 17a and b show the SEM images of multilayered Lab-GO and CGT-GO. GO sheets are widely spread, as no mechanical grinding was performed on either GO. As shown in Fig. 17a, torn sheets occur during drying and sample preparation. The damaged areas of GO display the multiple GO layers, while the crumpled areas on the graphene’s surface indicate oxygenated functional groups. SEM image of CGT-GO shown in Fig. 17b shows wavey GO sheets like in Lab-GO46.

Figure 17c and d display the SEM images of the control mortar and the Lab-GO-added cement mortar, respectively. Based on the elemental composition of the mortar obtained via EDX, the hydration products displayed on the SEMs are labelled. SEM of control mortar shown in Fig. 17c represents excess delayed ettringite crystals (spike-like structure) attached to calcium silicate crystals (CSH). In the presence of GO in cement mortar, CSH has increased, and the delayed ettringite has decreased47.

The TGA curves in Fig. 18 show the weight reduction of the control, Lab-GO, and CGT-GO-added cement mortars when exposed to higher temperatures. These TGA curves and the data summarised in Table 3 clearly show that the mass loss of the control sample is greater than that of the GO-added samples. The weight losses at 150 °C and 491 °C are more significant. The weight loss at 150 ºC corresponds to the decomposition of CSH and ettringite, and the loss of CH (calcium hydroxide) is demonstrated at 491 °C. The weight loss of CSH and ettringite (at 150 ºC) with control mortar, Lab-GO aged 7 weeks, Lab-GO aged 28 weeks, CGT-GO aged 10 weeks, and CGT-GO aged 28 weeks was 9.4 %, 3.6 %, 4.1%, 3.3 %, and 4.3 %, respectively. Decomposition of CH in control was 15.7%, while in Lab-GO of 7 weeks, Lab-GO of 28 weeks, CGT-GO of 10 weeks, and CGT-GO of 28 weeks, it was 7.2%, 8.6%, 7.2%, and 8.9%, respectively. Due to the organised arrangement of hydration products in GO-added mortar, thermal stability has increased, leading to lower decomposition of CSH, ettringite, and CH than in the control. Early aged commercial GOs and Lab GOs were more thermally stable than older samples.

The BET analysis was performed on control mortar and mortar with 0.03% Lab-GO and CGT-GO. The BET surface area of cement mortar (25.18 m2/g) increased to 36.77 m2/g upon the addition of 0.03% Lab-GO. The control mortar’s total pore and micropore volumes were estimated at 0.047 cc/g and 0.010 cc/g, respectively. Meanwhile, with 0.03% fresh Lab-GO mortar, the total pore volume remained unchanged (0.047 cc/g), but the micropore volume increased marginally to 0.011 cc/g. Furthermore, the pore radius of mortar with 0.03% Lab-GO and control mortar was the same (1.54 nm). The total pore volume comprises mesopores and micropore volumes, so an increase in the volume of micropores decreases the volume of mesopores. This was due to higher levels of hydration products in cement mortar containing 0.03% GO compared with control mortar. More hydration products strengthen the cement matrix, requiring more energy for failure. Hence, the mechanical strength of 0.03% GO-containing mortar has improved.

Incorporation of Lab-GO and CGT-GO into cement mortar impacts the surface area, total pore volume, and mean pore radius, as shown in Table 4 and Fig. 19. Adding 4-week- and 10-week-old CGT-GO increased the surface areas by 27.4% and 18.7%, respectively, and slightly decreased the pore volume by 4.3% and 6.4%, respectively. The average pore radius was lower than the control with 4-week-old CGT-GO (− 8.4%) and 10-week-old CGT-GO (− 3.9%). The incorporation of 7-week-old Lab-GO increased the surface area by 38.2%, raised the total pore volume by 21.3%, and dropped the average pore radius by 20.1%. However, adding 18-week-old Lab-GO decreased the surface area and void volume by 20.4% and 8.5%, respectively, while the mean pore size increased by 6.1%. The general tendency observed is that the surface area remains above the control up to 10 weeks of age for CGT-GO, while for Lab-GO, the surface area decreased below the control for 18-week-old GO.

The surface area of cement generally increased with the incorporation of GO due to GO’s high surface area and its ability to serve as nucleation sites for cement hydration, leading to the formation of more C–S–H. Further, a large surface area increases the absorption of water and cement, improving hydration and forming a more extensive C–S–H network, which in turn increases the internal surface area. The total pore volume is expected to decrease at the optimal GO dosage, resulting in a denser, more compact microstructure. The volume of mesopores decreases due to the pore refinement and densification, while that of micropores increases with the incorporation of the optimal GO weight. GO serves as a template for C–S–H growth, filling micropores and controlling crack propagation. Further, GO is embedded in the cement matrix, and during this process, the larger pores are converted into micropores.

The crystallography of control mortar, Lab-GO, and CGT-GO-modified cement mortar was studied via X-ray diffraction (Fig. 20). The peaks display the key hydration products of cement mortar, including sand (SiO2). The presence of early-age GO (7-week Lab-GO and 10-week CGT-GO in mortar significantly increased CSH peaks, with the most prominent peaks appearing at 27.0º, 29.5º, and 55.0º. The control mortar and the 28-week-old CGT-GO added mortar showed similar ettringite peaks at 8º, whereas the 28-week-old CGT-GO showed an additional peak at 23º.

Discussion

The improved performance of cement composites is attributed to the number of oxygenated functional groups, as indicated by GO’s C/O ratio and its defect (ID/IG) ratio. Based on FT-IR results, CGT-GO contains more hydroxyl and carboxylic groups than Lab-GO. Carboxylic groups are stable compared to hydroxyl groups. Lab-GO is unstable compared to CGT-GO due to lower carboxylic groups, but both have similar depletion rates of oxygen functional groups, as shown in Table 3. In addition, the intensity of defects and disorder increased in Lab-GO with time compared to CGT-GO, as determined via Raman spectroscopy. Both Lab-GO and CGT-GO are multilayered and highly crystalline in nature.

Based on existing studies and SEM images (Fig. 3c and d), it can be confirmed that oxygen functional groups serve as nucleation sites and form a backbone for the arrangement of calcium silicate hydrates (CSH)46,47,48. CSH is the main hydration product of cement, impacting the strength of cement composites. Introducing early-aged GOs (before 13 weeks of age) into cement mortar significantly enhanced the compressive and tensile strengths due to higher nucleation sites (oxygen-functional groups) and lower disorder. Additionally, the absorption rate is lower than that of the control, indicating fewer voids in the cement matrix. However, the BET results of cement mortar with early-aged GO showed decreased average pore radius due to increased surface area, and the impact from total pore volume was insignificant. Aged Lab-GO and CGT-GO (after 15 weeks of age) have more defects and fewer nucleation sites, which decrease the strengths and raise the absorption rate when added into the mortar. The incorporation of aged GOs into mortar increased the mean pore radius and reduced the surface area, as determined by BET analysis. In addition, mortar samples with aged GOs have ettringite peaks (in XRD analysis), while early-age GO-containing samples lack ettringite peaks. Ettringite is a weaker hydration product compared to CSH. The aged GO-containing mortar contains ettringite and CSH peaks, confirming the reason for the decreased strength. However, with age, the performance of Lab-GO and CGT-GO-added mortars decreased. Still, the overall performance of CGT-GO added cement mortar performed better than that of Lab-GO, despite the drop in strength, as the CGT-GO is stable. Regardless of the reduced mechanical performance of mortars with older GO, all cement mortar samples remained thermally stable at higher temperatures, as indicated by TGA results; the hydration products formed are thermally more stable than those in the control sample.

The expiry period for each type was determined based on the mechanical properties of Lab-GO and CGT-GO (of different ages) and the added cement mortar. However, the compressive and splitting tensile strengths of both GO-added cement mortars decreased with the ageing of GO. Still, their performance was at a peak during the early ages. Hence, an expiry period of 13 weeks can be marked on Lab-GO and CGT-GO, considered in this study. As the properties of GOs depend significantly on manufacturing processes, it is essential to note that GO from other sources may exhibit different behaviours. Hence, to validate this claim, more data should be obtained to confirm the mentioned shelf life.

Conclusions

This study confirms that the carbon-to-oxygen ratio (C/O), the disorder of graphene oxide sheets, and the number of layers govern the performance of cement composites. With the ageing of GOs (especially after 15 weeks), the performance of cement mortar decreases, ultimately reaching properties similar to those of the control mortar. Incorporation of early-aged Lab-GO and CGT-GO (up to 10–13 weeks) increased the 28-day compressive strength of both GOs by 20% and the splitting tensile strengths of both GOs by slightly above 50%. In general, the addition of Lab-GO and CGT-GO of any age improves the thermal stability of cement mortar. To achieve the benefits of nanomaterial incorporation, GO must be added to cement mortar before the GO reaches 13 weeks of age. The 13-week shelf life of Lab-GO and CGT-GO is determined based on a small sample size and depends on the GO production method and the environments to which they are exposed. Hence, to confirm the shelf life of GO, additional data are needed. Future research should concentrate on improving the chemical, thermal, and long-term stability of GO by tailored surface functionalization, effective reduction methods, and the production of protective composite frameworks.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Khan, M. I., Abbas, Y. M. & Fares, G. Review of high and ultrahigh performance cementitious composites incorporating various combinations of fibers and ultra fines. J. King Saud Univ. Eng. Sci. 29(4), 339–347 (2017).

Nayak, D. K., Abhilash, P. P., Singh, R., Kumar, R. & Kumar, V. Fly ash for sustainable construction: A review of fly ash concrete and its beneficial use case studies. Clean. Mater. 6, 100143 (2022).

Sharma, R., Jang, J. G. & Bansal, P. P. A comprehensive review on effects of mineral admixtures and fibers on engineering properties of ultra-high-performance concrete. J. Build. Eng. 45, 103314 (2022).

Behnia, B., Safardoust-Hojaghan, H., Amiri, O., Salavati-Niasari, M. & Aali Anvari, A. High-performance cement mortars-based composites with colloidal nano-silica: Synthesis, characterization and mechanical properties. Arab. J. Chem. 14(9), 103338 (2021).

Yoo, D., Oh, T. & Banthia, N. Nanomaterials in ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC) – A review. Cement Concr. Compos. 134, 104730 (2022).

Yesudhas Jayakumari, B., Nattanmai Swaminathan, E. & Partheeban, P. A review on characteristics studies on carbon nanotubes-based cement concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 367, 130344 (2023).

Ashwini, R. M. et al. Compressive and flexural strength of concrete with different nanomaterials: A critical review. J. Nanomater. 2023, 1–15 (2023).

Abhilash, P. P., Nayak, D. K., Sangoju, B., Kumar, R. & Kumar, V. Effect of nano-silica in concrete; A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 278, 122347 (2021).

Ahmed, D. N. & Alkhafaji, F. F. Enhancements and mechanisms of nano alumina (Al2O3) on wear resistance and microstructure characteristics of concrete pavement. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 871(1), 012001 (2020).

Wang, Q. et al. Research progress on the effect of graphene oxide on the properties of cement-based composites. New Carbon Mater. 36(4), 729–750 (2021).

Wang, L., Zhang, H. & Gao, Y. Effect of Tio2 nanoparticles on physical and mechanical properties of cement at low temperatures. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 1–12 (2018).

Silvestro, L. & Gleize, P. J. Effect of carbon nanotubes on compressive, flexural and tensile strengths of Portland cement-based materials: A systematic literature review. Constr. Build. Mater. 20(264), 120237 (2020).

Ganesh, S., Thambiliyagodage, C., Perera, S. V. T. J. & Rajapakse, R. K. N. D. Influence of laboratory-synthesized graphene oxide on the morphology and properties of cement mortar. Nanomaterials 13(1), 18 (2022).

Wu, Y.-Y., Que, L., Cui, Z. & Lambert, P. Physical properties of concrete containing graphene oxide nanosheets. Materials 12(10), 1707 (2019).

Gladwin Alex, A., Kedir, A. & Gebrehiwet Tewele, T. Review on effects of graphene oxide on mechanical and microstructure of cement-based materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 360, 129609 (2022).

Chuah, S., Li, W., Chen, S. J., Sanjayan, J. G. & Duan, W. H. Investigation on dispersion of graphene oxide in cement composite using different surfactant treatments. Constr. Build. Mater. 161, 519–527 (2018).

Amini, K., Soleimani Amiri, S., Ghasemi, A., Mirvalad, S. & Habibnejad Korayem, A. Evaluation of the dispersion of Metakaolin-Graphene oxide hybrid in water and cement pore solution: Can Metakaolin really improve the dispersion of graphene oxide in the calcium-rich environment of hydrating cement matrix?. RSC Adv. 11(30), 18623–18636 (2021).

Lv, S., Zhang, J., Zhu, L. & Jia, C. Preparation of cement composites with ordered microstructures via doping with graphene oxide nanosheets and an investigation of their strength and durability. Materials 9(11), 924 (2016).

Indukuri, C. S. & Nerella, R. Enhanced transport properties of graphene oxide based cement composite material. J. Build. Eng. 37, 102174 (2021).

Mohammed, A., Sanjayan, J. G., Duan, W. H. & Nazari, A. Incorporating graphene oxide in cement composites: A study of transport properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 84, 341–347 (2015).

Indukuri, C. S., Nerella, R. & Madduru, S. R. Workability, microstructure, strength properties and durability properties of graphene oxide reinforced cement paste. Aust. J. Civ. Eng. 18(1), 73–81 (2020).

Chen, Y. et al. High-temperature properties of cement paste with graphene oxide agglomerates. Constr. Build. Mater. 320, 126286 (2022).

Li, C. et al. Effect of long-term ageing on graphene oxide: Structure and thermal decomposition. R. Soc. Open Sci. 8(12), 202309 (2021).

Lin, H., Iakunkov, A., Severin, N., Talyzin, A. V. & Rabe, J. P. Rapid aging of bilayer graphene oxide. J. Phys. Chem. C 126(48), 20658–20667 (2022).

Gyarmati, B. et al. Long-term aging of concentrated aqueous graphene oxide suspensions seen by rheology and Raman spectroscopy. Nanomaterials 12(6), 916 (2022).

Habte, A. T. & Ayele, D. W. Synthesis and characterization of reduced graphene oxide (RGO) started from graphene oxide (GO) using the tour method with different parameters. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 1–9 (2019).

Benzait, Z., Chen, P. & Trabzon, L. Enhanced synthesis method of graphene oxide. Nanoscale Adv. 3(1), 223–230 (2021).

ASTM International. Standard Specification for Blended Hydraulic Cements. ASTM C595/C595M-16 ; West Conshohocken, PA, 2016.

ASTM International. Standard Specification for Aggregate for Masonry Mortar. ASTM C 144 -18; West Conshohocken, PA, 2018.

ASTM International. Standard Specification for Chemical Admixtures for Concrete. ASTM C494/C494M-08; West Conshohocken, PA, 2008.

ASTM International. Standard Specification for Mixing Water Used in the Production of Hydraulic Cement Concrete. ASTM C1602/C1602M-18; West Conshohocken, PA, 2018.

Hewathilake, H. P. T. S. et al. Geochemical, structural and morphological characterization of vein graphite deposits of Sri Lanka: Witness to carbon rich fluid activity. J. Mineral. Petrol. Sci. 113(2), 96–105 (2018).

Marcano, D. et al. Improved synthesis of graphene oxide. ACS Nano 4(8), 4806–4814 (2010).

Usgodaarachchi, L., Jayanetti, M., Thambiliyagodage, C., Liyanaarachchi, H. & Vigneswaran, S. Fabrication of r-GO/GO/α-Fe2O3/Fe2TiO5 nanocomposite using natural ilmenite and graphite for efficient photocatalysis in visible light. Materials. 16(1), 139 (2022).

Liyanaarachchi, H. et al. The photocatalytic and antibacterial activity of graphene oxide coupled CoOx/MnOx nanocomposites. Environ. Technol. Innov. 37, 103984 (2025).

Mrózek, O. et al. Salt-washed graphene oxide and its cytotoxicity. J. Hazard. Mater. 5(398), 123114 (2020).

ASTM International. Mechanical Mixing of Hydraulic Cement Pastes and Mortars of Plastic Consistency. ASTM C 305- 20. ; West Conshohocken, PA, 2020.

ASTM International. Standard Test Method for Normal Consistency of Hydraulic Cement. ASTM C 187 – 04. ; West Conshohocken, PA, 2004.

ASTM International. Standard Specification for Mortar for Unit Masonry. ASTM C270 – 19; West Conshohocken, PA, 2019.

ASTM International. Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Hydraulic Cement Mortars. ASTM C109/C109M -18; West Conshohocken, PA, 2018.

ASTM International. Standard Test Method for Splitting Tensile Strength of Cylindrical Concrete Specimens. ASTM C496/C496M-11; West Conshohocken, PA, 2011.

ASTM International. Standard Specification for Mixing Rooms, Moist Cabinets, Moist Rooms, and Water Storage Tanks Used in the Testing of Hydraulic Cements and Concretes. ASTM C511 - 21; West Conshohocken, PA, 2021.

Son, D.H., Hwangbo, D., Suh, H., Bae, B.I., Bae, S. and Choi, C.S., “Mechanical properties of mortar and concrete incorporated with concentrated graphene oxide, functionalized carbon nanotube, nano silica hybrid aqueous solution,” Case Studies in Construction Materials 2022, vol. 18.

Klun, M., Bosiljkov, V. & Bosiljkov, V. B. The relation between concrete, mortar and paste scale early age properties. Materials 14, 1569 (2021).

ASTM International. Standard Test Method for Rate of Water Absorption. ASTM C1403–13; West Conshohocken, PA, 2013.

Verma, P., Chowdhury, R. & Chakrabarti, A. Synthesis process and characterization of graphene oxide (go) as a strength-enhancing additive in concrete. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 28(11), 2575–2603 (2024).

Kang, X., Zhu, X., Qian, J., Liu, J. & Huang, Y. Effect of graphene oxide (go) on hydration of tricalcium silicate (C3s). Constr. Build. Mater. 203, 514–524 (2019).

Ghazizadeh, S., Duffour, P., Skipper, N. T. & Bai, Y. Understanding the behaviour of graphene oxide in Portland cement paste. Cem. Concr. Res. 111, 169–182 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support of Mr M. Gunawardana, Ceylon Graphene Technologies Ltd. (CGT), in providing nanomaterials for this study. They also appreciate the research facilities provided by the Sri Lanka Institute of Information Technology. The experimental facilities and testing support extended by the Sri Lanka Institute of Nanotechnology, Ultra Tech Cement Lanka, the University of Moratuwa, and CGT are acknowledged.

Funding

This research was partially funded by the Sri Lanka Institute of Information Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, all authors; methodology, SG and CT; validation, all authors; formal analysis, SG, CT and JP; investigation, SG; data curation, SG; resources, CT, JP and RKNDR; funding, RKNDR; writing-original draft, SG and CT; visualization, SG; writing-review and editing, RKNDR, CT and JP; supervision, RKNDR, CT and JP; project administration, RKNDR.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ganesh, S., Thambiliyagodage, C., Perera, S.V.T.J. et al. Influence of ageing of graphene oxide on the properties and morphology of cement mortar. Sci Rep 16, 768 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30230-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30230-y