Abstract

Modelling of grinding load motion is important for determining the dynamic parameters of grinding bodies in grinding chambers, which directly affects the determination of energy consumption of rock destruction in mills of various types. The aim of the work is to create a digital physical model of the grinding load of a drum mill, taking into account the physical properties of the grinding rock with the possibility of optimising the grinding process using artificial intelligence. For physical simulation of the grinding load of the drum mill by the finite element method, the LS Dyna programme from the Ansys package was used. The finite element mesh was built in Altair Hypermesh, LS Prepost software was used to create the model and visualise the results of calculations, and ParaView was used for post-processing of the results. In the work the processes of rock pieces destruction at impact and abrasive impact of grinding bodies on the crushed material with consideration of physical properties of rock were investigated. As a result of combining several models of grinding load motion at different operating modes of the mill, a generalised model of the process of rock destruction was obtained, which takes into account physical properties of the material being ground, sizes of balls and pieces of rock, as well as the influence of fine fractions on the grinding process. It has been established that the criterion for optimising the mill design and operating parameters can be the rock grinding speed. The dynamic portraits of grinding load obtained in the study allow to optimise the grinding process by the criterion of energy consumption.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rock grinding is an important stage in the process of mineral processing. The essence of this process is that the raw material is crushed to the smallest particles, providing the necessary opening of the mineral to extract valuable components. However, it should be noted that rock grinding requires significant energy inputs, making it one of the most energy-intensive stages in the entire extraction chain. Therefore, the development of efficient methods and technologies to optimise the grinding process is becoming an important area of innovation in the mining industry1,2.

Grinding is a complex technological process, which is carried out in specialised mills of different types depending on the required size of the ground material. Ball, vibratory, planetary and other types of mills are widely used to provide the required degree of grinding of the final product. Often the technological process of grinding includes several stages of grinding the rock in different mills. For example, a ball mill may be used to achieve coarse grinding and primary processing of the material. The ground material is then subjected to the next grinding stage in a vibratory mill to obtain medium particle size. Finally, to obtain ultrafine fractions, the rock may be ground in a planetary mill. This is due to the principle of operation of the different types of mills, and consequently the requirements for the size of the pieces of rock to be fed - for example, large pieces will significantly reduce the efficiency of the vibrating mill, and the planetary mill may fail altogether3,4,5.

It should also be noted that, in the overwhelming majority of industrial schemes of fine grinding of metal ores, preliminary operations such as washing and drying are not included in the technological process. Grinding is usually performed immediately after crushing or classification, with only a general control of the feed moisture content to avoid excessive dusting or sticking of the material. Therefore, these factors were not considered as a key part of the present study6,7.

Thus, the ball mill is involved both in a single-stage grinding process and as the first stage of a multi-stage process. Improving its efficiency is an extremely important task, as it increases the beneficiation efficiency of many minerals and reduces the specific energy consumption of grinding. The power of ball mill drives varies from hundreds of kilowatts to tens of megawatts, and even a small reduction in energy consumption will have a significant impact on the economic performance of mining and processing enterprises8.

The paper9 discusses the creation of a digital physical model of the grinding load of a drum mill with rock. With its help it is possible to quickly conduct experiments on optimisation of various mill parameters - number, weight and size of balls, size and number of lifters, mill speed, etc. to achieve the best energy efficiency of grinding. In addition, the numerical model opens up opportunities for optimisation using artificial intelligence - after training on the numerical model, the AI will be able to make a decision to change the mill operating parameters in real time and control the mills remotely.

The article10 presents a mathematical model of grinding in a ball mill based on the assumption of uniform mixing of grinding bodies and rock. The model was developed for laboratory mills, and the article provides instructions for scaling the results obtained in the laboratory to production mills. This model can predict mill performance within certain limits using experiments on smaller mills, but once scaled, the predictions may not be accurate, and the analytical model does not provide a visual assessment of fracture processes.

Modern CAD-systems will help to visualise the mill operation process and perform calculations in real scale11. Various articles describe methods of ball mill modelling in such systems as Rocky DEM, LS Dyna, Abaqus and others12,13,14. The authors of the articles15,16,17,18 use discrete element method (DEM) to simulate the motion of the grinding load. The articles discuss in detail the mechanics of ball motion in the mill and derive relations that allow predicting the rate and nature of rock fracture based on the parameters of ball motion. An overview of the application of the discrete element method for ball mill simulation is presented in the article19. In it, on the basis of the considered simulations, dependencies describing the probability of cracks in the rock from the ball energy, the fracture rate from the size of rock and ball particles, the number of collisions per second at different ball sizes, etc. are presented.

In articles20,21 simulation modelling of apatite-nepheline ore grinding process with determination of wear parameters of mill lining elements in Rocky DEM software is considered. The types of wear occurring in the ball mill have been analysed, it has been established that depending on the strength of processed rocks and the mode of medium movement in the ball mill abrasive, impact-abrasive or fatigue type of wear can be observed. On the basis of modelling results the service life of lining is calculated. A grinding process control system for mills using modern variable frequency drives is proposed.

Also the discrete element method is applied to the modelling of planetary mills, the results are described in articles12,13. Using the planetary mill model, the authors determined the dependences of grinding efficiency on loading, rotational speed, ball size and other parameters. The papers present visual results of simulations that allow us to evaluate the distribution of ball velocities in the drum. At the same time, in all the above works, the motion of grinding balls is calculated in the model, and in some of them18 the motion of rock, which is determined in exactly the same way as the balls - by the discrete element method. The process of rock fracture is not taken into account, the shape of rock pieces is spherical due to the limitations of the simulation method.

A lot of works are devoted to modelling ball mills using artificial intelligence, or training AI models on the example of physical simulations of mills or experimental data. For example, in22, the model is trained on data from one of the fields. The authors claim that the model showed much better predictive ability compared to statistical methods23,24. Similar models are presented in papers25,26. The models were trained on real data, which is by far the most accurate source of reliable training and test sample. But the downside of this approach is the narrow coverage of the sample - that is, the model is trained on a specific rock and mill model, or on a small number of diverse rocks or mills. The authors of the papers27,28,29 applied a more universal method - they created a training and test sample using the results of physical simulations using the discrete element method. The advantage of using simulation results to train AI models is the possibility of creating an infinite number of combinations of different parameters, such as rock strength and size, mill loading, parameters of grinding bodies and the mill itself, etc. But, as mentioned above, the discrete element method used does not accurately model the rock fracture in the mill, which will lead to a discrepancy between the predictions of the AI models and the experimental data.

This paper presents a model of a mill not only with a grinding feed, but also with the rock to be broken. Such a model clearly demonstrates the processes of splitting and abrasion of rock pieces, which is much closer to reality compared to the currently used models.

In order to achieve the set goal, the following tasks were solved within the framework of this work:

-

1)

Develop a model of a ball mill with destructible rock;

-

2)

to develop a model of collision of one grinding ball with one piece of rock for quick adjustment and verification of rock material parameters;

-

3)

visually and analytically evaluate the validity of the simulation results.

Materials and methods

The first step in our research was to create a simulation of a grinding load with no rock - only balls using the Discrete Element Method (DEM). Since this model contained no rock, the calculations were fast. However, when rock particles were added, the DEM simulation of balls had to be abandoned in favour of spheres divided into finite elements.

In the second stage of our research, the material modelling of the rock itself was carried out to achieve accuracy and reliability of the results when modelling the grinding process in the mill. The Johnson-Holmquist (JH-II) model was used. In addition, the structure of the rock piece was modelled.

The third stage of the work is devoted to the modelling of the contact process between the ball KE model and the SPH model of the rock.

The final stage of the research was the construction of a dynamic portrait of the grinding load with the grinding rock, as well as obtaining the dependences linking the efficiency of the grinding process and its energy consumption.

Simulation software used

The 3D model of the mill drum, balls and rock was created in Blender v.4.0. Altair Hypermesh 2023.1 was used to construct the finite element mesh of the rock. In this software, the 3D model of the rock piece was broken down into a finite element mesh with a given step size. Next, elements that were too fine were manually eliminated as they would reduce the time step of the modelling and increase the overall computation time. The finite element mesh of the drum and balls did not require manual processing, so it was created in LS Prepost v.4.10. In the same programme the physical parameters of the model were set, such as free fall acceleration, surface friction coefficients, material properties, etc. This model was used for simulation in LS Dyna R14.1. The results of the calculations were processed in LS Prepost and the graphs of rock mass and ball energy were exported using the same programme. ParaView 5.12.1 was used for post-processing and visualisation of the results.

Calculation of the developed model was performed on a computer complex with 20 CPU cores. The calculation took about 100 h. Calculation of the developed model can be run on more nodes to speed it up. It is also worth noting the use of the GROUPABLE flag in the definition of contact maps: it allows combining several contacts into a single interprocessor message, which reduces the amount of information transferred between MPP processes, speeding up the computation30,31.

Initial data for modelling

Operating modes of the mill

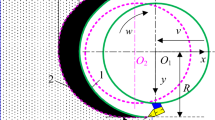

There are three main modes of ball mill operation - cascade, mixed and waterfall (Fig. 1):

-

in the cascade mode, the grinding bodies roll over, abrading the rock;

-

in the mixed mode, both the flying and rolling phases are present;

-

in the waterfall mode, the grinding bodies fall on the rock, destroying it mainly by impact rather than by abrasion.

There is also a centrifugation mode in which centrifugal force exceeds gravity and the balls, as well as the rock, move with the drum. This mode is not considered in this paper.

At low drum speeds, the grinding balls cascade. At the moment of start-up the balls and rock are rotated by an angle θ, after which they start moving. In the operating mode, the grinding medium does not change its position and the grinding bodies move along a closed trajectory, rising and descending in a cascade back to the starting point. The slow-moving core is located in the middle of the grinding media. Grinding of the material occurs mainly due to abrasion of the rock by the grinding bodies - this mode is used for grinding soft rocks.

The mixed mode is characterised by both impact and abrasion effects on the rock. Balls with a higher angular velocity relative to the centre of the mill are lifted to a certain height under the action of centrifugal force and then fall on the rock. Balls with lower angular velocity roll down in a cascade, abrading the rock. This mode is used for grinding ores with different strengths.

In the waterfall mode, the angular velocity is sufficient for most of the grinding bodies to rise with the drum and then fall on the rock. In this mode, grinding occurs mainly by the impact of the balls on the rock, which allows grinding hard but brittle rock as well as large pieces of rock.

The diameter of the mill balls was selected based on the generally accepted ratio of grinding chamber diameter to ball diameter, the value of which is in the range of 30–60.

The diameter of the drum was taken equal to 1.7 m, which corresponded to the value of the diameter of the grinding chamber of the pilot mill, on which the research was conducted to experimentally confirm the main results presented in this article.

Based on the above, the value of ball diameter was taken as 50 mm. The values of angular velocity of rotation of grinding chamber were chosen in the range from 2 to 40 rpm. At values of angular speed of rotation of the grinding chamber less than 2 rpm the intensity of interaction of balls with rock tends to 0, and grinding practically does not occur. At values of angular speed of rotation of the grinding chamber greater than 40 rpm the balls under the action of centrifugal forces begin to stick to the walls of the grinding chamber (self-lining mode) and grinding also practically does not occur.

Calculation of mill drum rotational frequency

The mill operating mode is determined by the relative mill speed ψ and the filling factor ϕ, calculated by formulas (1) and (2)32,33:

where n – the mill speed, rpm; ncr – the critical mill speed, rpm; V – the volume of the mill drum, m3; VН – the volume of grinding bodies, m3. The critical frequency of rotation is the frequency at which the centrifugal force is equal to or exceeds the force of gravity, and the load rotates together with the drum without breaking away from it. The critical frequency is calculated by formula (3):

where g – the free fall acceleration, m/s2, D – the inner diameter of the mill drum, m. The volume of the mill drum V is calculated by formula (4), and the volume of grinding bodies by formula (5)34,35:

where L – drum length, m; GH – mass of grinding bodies, kg; γu – ball bulk density, kg/m3. Thus, the fill factor can be calculated by the formula (6):

Experimental installation

To validate the computational model, field experiments were performed on a facility developed and customised by IPCON RAS. First, a 3-D model of a pilot test stand based on a drum mill was made (Fig. 2), and then the mill itself was manufactured.

3-D model of experimental-industrial stand based on drum mill (Kompas 3D v22.1, https://kompas.ru/).

Field tests

Field tests were carried out on an industrial prototype of a drum mill with a diameter of 1.7 m. The power consumed by the electric motor did not exceed 12 kW; the number of revolutions of the grinding chamber did not exceed 40 rpm. The maximum length of the drum was 200 mm; the maximum weight of the grinding load was 800 kg; the diameter of the balls was 50 mm. To confirm the results of computer modelling, the end face of the pilot plant of the drum mill was made of thick-walled plexiglass (Figs. 3 and 4D).

Results and discussion

Modelling the movement of the grinding media without rock

The first step in our research was to create a simulation of a grinding load with no rock - only balls using the Discrete Element Method (DEM). Since this model contained no rock, the calculations were fast. But when rock particles were added, the DEM simulation of balls had to be abandoned in favour of spheres divided into finite elements - the reasons will be described later in this paper.

As described in several papers11,12,13,14, the grinding balls in a ball mill can be considered as a bulk medium. The discrete element method is well suited for the simulation of bulk materials as follows:

-

material particles are represented by spheres with a given volume and density;

-

contacts of particles with each other and other objects are described by Hooke’s law and friction forces.

The scheme of DEM-particle interaction is shown in Fig. 336,37.

The motion of the ball along the three coordinate axes is described by the system of Eq. (7)

where x, y, z – coordinates of the ball’s centre of mass, m; c – resistance coefficient, kg/s; k – elasticity coefficient, Н/м; ρ – material density, kg/m3; V – volume of the ball, m3. Resistance coefficient is set in CONTROL_DISCRETE_ELEMENT settings, elasticity coefficient is calculated based on Young’s modulus specified in the material properties. The rotation of the ball is described by formula (8)

where φ – rotation angle, rad; M – force moment, N m; I – moment of inertia, kg∙m2. LS Dyna allows you to set an arbitrary moment of inertia, which allows you to simulate not only full-body spheres, but also thin-walled spheres.

The mill parameters are given in Table 1. The material of the mill and balls is steel 20. Figure 4 shows the distributions of ball velocities at angular speeds of mill rotation of 8, 16 and 24 rpm, respectively.

Linear velocity distribution of grinding balls inside a mill rotating at different angular velocities (kinematic profile of the grinding load). (A) 8 rev/min, (B) 16 rev/min, (C) 24 rev/min, (D) validation of digital modelling results using prototypical industrial sample ball mill (Ansys LS Dyna R14.1, https://www.ansys.com/products/structures/ansys-ls-dyna).

Rock material model

In order to achieve accurate and reliable results when modelling the grinding process in the mill, it is necessary to pay special attention to the material modelling of the rock itself. The Johnson-Holmquist model (JH-II) was used - it takes into account the accumulated damage and allows an accurate description of the fracture processes of brittle materials. According to this model, the stress in the material is determined by formula (9)38,39,40,41:

where \(\sigma _{i}^{*}\)– stress in the undamaged material, determined by formula (10):

In formulas (2) and (3), the symbol “*” denotes normalised values. Stress and pressure are normalised by the pressure value at the Hugoniot elastic limit point, strain rate is normalised by the reference value of strain rate given in the calculation. The value a – is the coefficient of normalised stress in the undamaged material, n – is the strength factor of the undamaged material, c – is the strain rate coefficient, \({\dot {\varepsilon }^*}\)– is the normalised strain rate. The pressure values t* and p* are determined by relations (11) and (12)

where T – is the tensile strength of the material in Pa; p – is the pressure; PHEL – is the pressure at the point of the Hugoniot elastic limit.

The coefficient D of formula (2) reflects the accumulated damage based on the change in strain per one cycle of calculations \(\Delta {\varepsilon ^p}\) and the ultimate strain \(\varepsilon _{f}^{p}\) (13):

The ultimate strain is calculated by formula (14):

The parameters d1 and d2 determine the rate at which damage accumulation occurs. For example, if d1 is zero, the fracture occurs within one cycle of calculations, i.e. instantaneously. Finally, the parameter \(\sigma _{f}^{*}\) is determined by formula (15):

where b – is the coefficient of normalised stress in the damaged material; m – is the strength factor of the damaged material; SFmax – is the maximum normalised strength of the damaged material.

In undamaged material the compressive stress is determined by formula (16), tensile stress – by formula (17):

where k1, k2, k3 – are pressure coefficients; µ is determined by formula (18):

Material fracture is accompanied by stress growth. The coefficient β, varying from 0 to 1, determines the part of strain energy that will be converted into stress. In the developed simulation, the coefficient β is equal to one, which means that there is no loss of strain energy. Knowing the Hugoniot elastic limit (HEL) and the shear modulus G, the value of µhel can be found from relation (19):

Finally, knowing the value of µhel, we can find the pressure at the point of the Hugoniot elastic limit – PHEL (20):

Modelling a piece of rock

Once the material model was selected, a method of modelling the rock structure had to be chosen. The first option was the smoothed particle hydrodynamics (SPH) method. Contrary to its name, this method is not only suitable for modelling liquids and gases, but also for bulk materials and even solids. This method, unlike finite element mesh destruction (ADD_EROSION in LS Dyna), does not remove destroyed elements from the simulation - that is, it correctly calculates the interaction of all fragments after destruction.

The method consists in dividing the body into particles. The physical parameters (density, temperature, etc.) at each point of space are given by function (21)42:

where A(r) – is the quantity sought; mj – is the mass of the particle; ρj – is the density of the particle; W – is the kernel function; h – is the smoothing length. The kernel function describes the dependence of a physical quantity on the distance to the particle. Often a cubic spline or Gaussian function is used as the kernel function43. The smoothing length serves to limit the particle interaction distance (22):

Thus, the speed of calculations increases, since the interaction of particles at a distance greater than 2 h is ignored.

Before simulation of grinding in a mill involving a large number of balls and rock, it was decided to debug the fracture model on the example of interaction of one ball with one piece of rock. The calculation of such a debugging model is much faster than that of a whole mill. The parameters of the ball are given in Table 2. Dolomite was chosen as the rock, and the parameters of the Johnson-Holmquist model for dolomite are given in Table 3. The parameters of the rock piece are given in Table 4.

The first problem with SPH modelling of the rock structure was the incorrect calculation of the contact between the DEM ball and the rock. When increasing the ball diameter, starting from a certain value (about 40 mm) the ball began to pass through the rock. The result is shown in Fig. 5.

Contact modeling of DEM ball and SPH rock. 1 – initial state, 2 – impact (Ansys LS Dyna R14.1, https://www.ansys.com/products/structures/ansys-ls-dyna).

In order to overcome this error, it was decided to model the ball not by a DEM-particle, but by a finite element (FE) sphere composed of tetrahedrons. The sphere consists of 766 elements; the radius, material and other parameters are identical to the DEM sphere. The result of the impact is shown in Fig. 6. To clarify, the number of 766 tetrahedral elements was not chosen arbitrarily by the authors but was generated automatically by the meshing algorithm in LS Dyna based on the selected surface discretisation. The sphere was initially approximated by a polyhedron with 320 triangular faces, which was found to provide a satisfactory balance between geometric accuracy and computational efficiency. When this polyhedron was converted into a solid body, the mesher created a consistent tetrahedral grid consisting of 766 elements. This number is therefore a natural outcome of the chosen surface approximation and the internal meshing rules (element quality criteria, edge ratios, and angular constraints) rather than a fixed input parameter. A finer initial approximation (e.g., 1280 faces) would have produced several times more elements, significantly increasing the simulation time without a proportional improvement in accuracy. For this reason, the 320-face polyhedron and the resulting mesh of 766 tetrahedrons were adopted as an optimal compromise for the present study.

Contact modeling of FEA ball and SPH rock. 1 – initial state, 2 – impact (Ansys LS Dyna R14.1, https://www.ansys.com/products/structures/ansys-ls-dyna).

As can be seen from the simulation, the contact between the KE ball and the rock is calculated correctly. However, the result was still not sufficiently reliable, as the fracture cracks characteristic of impact on brittle material were poorly manifested during impact. Also the calculation of SPH-particles required quite a lot of computational resources - the simulation of loading with many balls and pieces of rock would take too long. Therefore, this method had to be abandoned in favour of a FE mesh with element removal at fracture.

In order to correctly simulate fracture using the KE-mesh, it is necessary to set an element failure criterion for the material used (ADD_EROSION). The exceedance of equivalent strain calculated by the formula (23) was chosen as the criterion of failure.

where \(\varepsilon _{{ij}}^{{dev}}\) components of the plastic deformation deviator related to the plastic deformation tensor ε by the relation (24):

A maximum value of εeff = 0.01 was chosen for the simulation, which is typical for dolomite45.

Before determining the mesh size of 8 mm, a simulation with a finer mesh of 5 mm was tested. The finer the mesh, the more accurate the fracture can be simulated, but the calculation time increases significantly, both because of the overall increase in the number of elements and because of the reduced calculation time step. LS Dyna allows for explicit and implicit calculations, and their scope of application is shown in Fig. 7.

The implicit method has the advantage of a larger time step, but it is applicable only for static and quasi-static analysis problems where mesh changes are slow. The formulation of the problem for implicit analysis is as follows (25)46:

where K – is the stiffness matrix; x – is the coordinate matrix; F – is the force matrix. Due to the fact that the position of elements changes slowly, the implicit solver uses large time steps for incrementation and after each step iteratively calculates the convergence of the obtained solution. Since the process consists in the sequential solution of systems of linear equations, the implicit method can be run not on the central processor, but on the graphics adapter of the computer, which significantly speeds up the calculations.

Despite the advantages of the implicit method, it is not suitable for dynamic problems where the position of elements and the forces acting on them can change significantly within milliseconds - for example, impact and destruction. The grinding process in a ball mill is just such a problem, so the explicit method was used for its calculation. The formulation of the problem for the explicit method is represented by Eq. (26):

where M – mass matrix; \(\ddot {x}\) – acceleration matrix; С – damping matrix; \(\dot {x}\) – velocity matrix; K – stiffness matrix; x – coordinate matrix; F – force matrix. The explicit solver does not calculate the convergence of each solution; instead, it uses extremely small increments, on the order of microseconds or less, to obtain reliable results. Thus, the time step is a very important criterion for both the correctness of the results and the speed of computation. LS Dyna calculates it automatically using the formula (27):

where l – is the minimum distance between two mesh nodes; c – is the propagation velocity of a longitudinal wave in a solid, calculated by formula (28) for a three-dimensional mesh and by formula (29) for a two-dimensional mesh.

In the above formulas, E – is Young’s modulus; v – is Poisson’s ratio; ρ – is the density of the material. Since Young’s modulus, Poisson’s ratio and density are determined by the modelled material, the distance between the nodes remains the only parameter that allows controlling the time step - the larger the distance, the larger the time step. Figure 8 shows the rock fracture simulation with grid sizes of 8, 5 and 3 mm.

Contact modeling of FEA ball and FEA rock with grid sizes of 8, 5 and 3 mm (Ansys LS Dyna R14.1, https://www.ansys.com/products/structures/ansys-ls-dyna).

In all three simulations, cracks characteristic of brittle fracture are clearly visible. After interaction with the ball, the rock disintegrates into several large fragments, and fragments smaller than the mesh size are removed from the simulation. Figure 9 shows a plot of the mass of a piece of rock for the given mesh sizes.

To determine the convergence of the results, a criterion of relative mass change was chosen, determined by the formula (30):

where me – is the mass of removed elements; m – is the initial mass of the rock. For the rock with mesh sizes of 3, 5 and 8 mm, the relative change is 0.533; 0.608 and 0.613, respectively. It is evident from the data that smaller mesh size removes less mass from the simulation, but the results are fairly close to each other. For the most accurate simulation of the mill operation it is necessary to choose the mesh size corresponding to the size of the finished grinding product - the elements will be removed from the simulation as the finished product would be poured out of the mill through the end meshes. It should be noted, however, that the calculation time increases exponentially as the mesh size decreases. In industry, the finished product is usually of the order of hundreds of microns in size - the developed model allows calculations with such a fine mesh, but, as follows from the results above, such a fine mesh is not required to obtain a sufficiently accurate calculation. The issue of determining the optimal mesh size for a particular type and size of rock, mill, etc. is not considered in this paper.

Simulation times of rock fracture with SPH structure, 3, 5 mm and 8 mm mesh are presented in Fig. 10.

Figure 11 shows a graph of the time dependence of the kinetic energy of the ball, which shows that 70.76; 75.80 and 78.33 J of ball energy was used to crush a piece of rock at 8, 5 and 3 mm mesh, respectively.

Results

By combining the mill, ball and rock models described above, we built a model of the grinding load with rock. One of the frames of the simulation result is shown in Fig. 12.

Snapshot of loaded mill simulation result, postprocessed with ParaView (ParaView 5.12.1, https://www.paraview.org/).

The mill operates in waterfall mode, so impact grinding dominates (Fig. 13). But abrasion is also present, although it is not as effective for hard rock (Fig. 14).

Simulation of impact destruction (ParaView 5.12.1, https://www.paraview.org/).

Simulation of abrasive destruction (ParaView 5.12.1, https://www.paraview.org/).

The ball and rock materials are similar to those mentioned above. Additional parameters of the model are given in Table 5.

Discussion

The criteria for optimisation of the design and parameters of the mill operation, as well as proof of the adequacy of the developed model to the real dynamic processes occurring in the grinding chamber of the drum mill can be the values of the experimental data obtained at the pilot plant of the drum mill, presented in Fig. 4D. In particular, experimental studies of dolomite grinding kinetics were carried out. Figure 15 shows a graph of the dependence of the change in the mass of rock in the mill on time at angular speeds of 16 and 12 rpm.

In the section from 0 to 2.5 s grinding does not occur, because at time 0 the drum is stopped, at time 1 s it starts moving, at time 2 s it gains the set speed and only at about 2.5 s the first balls and pieces of rock fall on the drum. Therefore, it is useful to analyse the performance not from the beginning of the simulation but from the moment of the actual start of the grinding process - in this case from the point of 2.5 s. As can be seen from the graph, grinding is much faster at 16 rpm, as the mill operates in waterfall mode at this angular velocity, which is confirmed by a photograph of the process (Fig. 4D). At 12 rpm, the mill operates in mixed mode, due to which the grinding speed is much lower, which is consistent with empirical data on the grinding of hard rocks. For rocks such as the dolomite presented in the simulation, the waterfall mode is better suited, as demonstrated by the simulation results and confirmed experimentally in the pilot plant.

Although washing and drying operations may in principle affect the grinding process, they are rarely applied in industrial practice for ores of the class studied. Excessive moisture can lead to the formation of agglomerates, reducing the efficiency of abrasion, while washing can remove clay and fine fractions, thereby slightly improving breakage kinetics. In our supplementary laboratory experiments, we observed that both moisture content and washing degree can modify the rate at which the rock is transformed into fine fractions under different mill regimes. However, these aspects were beyond the scope of the present article, which focused on the development and validation of a universal digital model of grinding load motion and rock breakage.

For experimental confirmation of the results of modelling of the grinding load motion, a series of experiments was carried out to establish the dependence of the mill productivity on the diameter of grinding balls. The results of experimental studies are presented in Fig. 16. The experiments were carried out at angular speeds of mill rotation of 8, 16 and 24 rpm, which corresponded to the values of angular speeds of mill rotation, adopted in the computer model of the mill and used in the compilation of the kinematic portrait of grinding load, presented in Fig. 4.

The analysis of the dependencies presented in Fig. 16 shows that the drum mill productivity is in parabolic dependence on the ball diameter, with increasing angular velocity of rotation (up to a certain value, until the mill does not enter the centrifugation mode) increases its productivity in the waterfall mode of operation. At angular speeds of about 8 rpm the mill operates in the cascade mode and its productivity is significantly lower than in the waterfall mode. These conclusions are in good agreement with the results of computer modelling of the grinding process obtained using the same values of ball diameter, drum diameter and angular speed of its rotation.

It should be noted that the choice of the optimal ball diameter is largely determined by the physical and mechanical properties of the processed rock. For softer rocks, medium-diameter balls provide a balance between abrasion and impact mechanisms, while for hard and strong rocks larger balls are preferable due to their higher impact energy. However, in the case of brittle materials, excessively large balls may cause overgrinding and an undesired increase in fine fractions. In this study, the main focus was placed on validating the digital model of the grinding process, whereas a detailed correlation between rock properties and optimal ball size selection will be the subject of future research.

Confirmation of the results of computer modelling on the pilot plant of the drum mill showed satisfactory convergence of the results of theoretical and experimental studies, the value of which was 87%.

Conclusion

The process of creating a digital model of the grinding motion of the grinding load of a drum mill with rock is presented, which allows to investigate the influence of various factors on the process of rock grinding.

The task of developing a model of a ball mill with destructible rock is fulfilled, and comparative results of grinding speed at different angular speeds of the mill − 12 and 16 rpm - are obtained. Despite the fact that the data reflect not the speed of obtaining a finished product, but grinding to a certain fraction, they can be used to assess the impact on the grinding process of various parameters such as the number and size of balls and pieces of rock, the design of the drum, the speed of its rotation and others. As mentioned above, the model showed a much higher grinding speed in the waterfall mode compared to the mixed mode, which is consistent with experimental data in the grinding of hard rocks. Also in the work were presented frames of abrasion and impact fracture of rock obtained during the simulation, which confirms the validity of the model.

Thus, the model makes it possible to conduct research, optimise production processes and make informed decisions based on the data obtained. Programmatic variation of parameters can be used to optimise the grinding process using artificial intelligence - for example, in evolutionary algorithms. The developed mill model requires a significant amount of computational resources, so it is recommended to run it on high-performance clusters.

In order to accelerate the tuning and verification of rock material parameters, a model of contact of one ball with one piece of rock was developed. It allows to evaluate the influence of the finite element mesh size on the validity of the results, to select the rock material parameters, to estimate the energy required for crushing, etc., and the result is calculated several orders of magnitude faster than the mill simulation. For the effective functioning of the mill model, it is important to pre-analyse the interaction of one ball with one piece of simulated rock according to the methodology presented in the paper. This approach will ensure that the process is correctly and accurately modelled and that reliable results are obtained using this model. Further development of the model will include the integration of material strength criteria into the selection of grinding ball sizes, which will enable a closer link between grinding regimes and the physical properties of specific rock types.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. In addition, the LS-Dyna simulation results of single ball-rock impact and ball mill grinding process are publicly available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16997503.

References

Vasilyeva, N., Golyshevskaia, U. & Sniatkova, A. Modeling and improving the efficiency of crushing equipment. Symmetry 15 (7), 1343. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym15071343 (2023).

Duryagina, A. M., Talovina, I. V., Lieberwirth, H. & Ilalova, R. K. Morphometric parameters of sulphide ores as a basis for selective ore dressing. J. Min. Inst. 256, 527–538. https://doi.org/10.31897/PMI.2022.76 (2022).

Aleksandrova, T., Nikolaeva, N., Afanasova, A., Romashev, A. & Kuznetsov, V. Justification for criteria for evaluating activation and destruction processes of complex ores. Minerals 13 (5), 684. https://doi.org/10.3390/min13050684 (2023).

Efmov, D. A. & Gospodarikov, A. P. Technical and technological aspects of the use of Reuleaux triangular profle rolls in crushing units in the ore processing plant. Min. Inf. Anal. Bull. 10 (2), 117–126. https://doi.org/10.25018/0236_1493_2022_102_0_117 (2022).

Chitalov, L. S. & Lvov, V. V. Comparative assessment of the bond ball mill work index tests. Min. Inf. Anal. Bull. 1, 130–145. https://doi.org/10.25018/0236-1493-2021-1-0-130-145 (2021).

Zhukovskiy, Y. L., Korolev, N. A. & Malkova, Y. M. Monitoring of grinding condition in drum mills based on resulting shaft torque. J. Min. Inst. 256, 686–700. https://doi.org/10.31897/PMI.2022.91 (2022).

Heinicke, F., Lieberwirth, H., Kühnel, R. & Aleksandrova, Т. N. Advantages of selective grinding using high-pressure grinding rolls combined with air classification. Obogashchenie Rud 1, 3–7. https://doi.org/10.17580/or.2022.01.01 (2022).

Lvov, V. & Chitalov, L. Semi-Autogenous wet grinding modeling with CFD-DEM. Minerals 11 (5), 485. https://doi.org/10.3390/min11050485 (2021).

Kravtsov, A. A., Anishchenko, V. I., Atrushkevich, V. A. & Pytalev, I. A. Prospects of WEBRTC technology application for remote control of mining equipment. Sustain. Dev. Mountain Territories. 12 (46), 592–599. https://doi.org/10.21177/1998-4502-2020-12-4-592-599 (2020).

Morrell, S. & и Man, Y. T. Using modelling and simulation for the design of full scale ball mill circuits. Minerals Eng. 10 (12), 1311–1327. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0892-6875(97)00123-4 (1997).

Yin, Z., Wang, N. & Li, T. DEM investigation of discrete heat transfer behavior of the grinding media in ball mills. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/4249726 (2022).

Amannejad, M. & Barani, K. Effects of ball size distribution and mill speed and their interactions on ball milling using DEM. Mineral. Proc. Extr. Metall. Rev. 42 (6), 374–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/08827508.2020.1781630 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. A DEM based scale-up model for tumbling ball mills. Powder Technol. 409, 117854. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2022.117854 (2022).

Xie, C. & Zhao, Y. Investigation of the ball wear in a planetary mill by DEM simulation. Powder Technol. 398, 117057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2021.117057 (2022).

Bian, X. et al. Effect of lifters and mill speed on particle behaviour, torque, and power consumption of a tumbling ball mill: experimental study and DEM simulation. Minerals Eng. 105, 22–35 (2017).

Jayasundara, C. T. & Zhu, H. P. Impact energy of particles in ball mills based on DEM simulations and data-driven approach. Powder Technol. 395, 226–234 (2022).

Rodriguez, V. A., de Carvalho, R. M. & Tavares, L. M. Insights into advanced ball mill modelling through discrete element simulations. Minerals Eng. 127, 48–60 (2018).

Lee, H., Kim, K. & Lee, H. Analysis of grinding kinetics in a laboratory ball mill using population-balance-model and discrete-element-method. Adv. Powder Technol. 30 (11), 2517–2526 (2019).

Tavares, L. M. A review of advanced ball mill modelling. KONA Powder Part J. 34, 106–124. https://doi.org/10.14356/kona.2017015 (2017).

Beloglazov, I. & Plaschinsky, V. Development MPC for the grinding process in SAG mills using DEM investigations on liner wear. Materials 17 (4), 795. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17040795 (2024).

Plaschinsky, V. A., Beloglazov, I. I. & Akhmerov, E. V. The analysis of wear model of working members in ball mills during ore milling. Mining Inf. Anal. Bull. 7, 91–110 (2024).

Umucu, Y. et al. The evaluation of grinding process using artificial neural network. Int. J. Mineral. Proc. 146, 46–53 (2016).

Klyuev, R. V. Optimization of power consumption at concentration plants using statistical analysise. MIAB Min. Inf. Anal. Bull 12, 150–161 (2024).

Balovtsev, S. V. & Merkulova, A. M. Comprehensive assessment of buildings, structures and technical devices reliability of mining enterprises. MIAB Min. Inf. Anal. Bull 3, 170–181 (2024).

Al Bannoud, M., Martins, T. D. & dos Santos, B. F. Control of a closed dry grinding circuit with ball mills using predictive control based on neural networks. Dig. Chem. Eng. 5, 100064 (2022).

Yu, J. et al. A machine learning approach for ball milling of alumina ceramics. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 123 (11), 4293–4308 (2022).

Jayasundara, C. T. & Zhu, H. P. Predicting liner wear of ball mills using discrete element method and artificial neural network. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 182, 438–447 (2022).

Li, Y. et al. Prediction of ball milling performance by a convolutional neural network model and transfer learning. Powder Technol. 403, 117409 (2022).

Nayak, D. K. et al. Monitoring the fill level of a ball mill using vibration sensing and artificial neural network. Neural Comp. Appl. 32, 1501–1511 (2020).

Brian, W. Efficient processing of multiple contacts in MPP DYNA. In 8th European LS-DYNA Users Conference, Strasbourg (2011).

Suslikov, Z. Y. L. Assessment of the potential effect of applying demand management technology at mining enterprises. Sustainable Dev. Mountain Territories. 16 (3), 895–908. https://doi.org/10.21177/1998-4502-2024-16-3-895-908 (2024).

Atrushkevich, D. Y. V., Kubrin, V. A. & Adamova, S. S. Evaluation of shock pulses energy in the grinding rocks process for various types of mills. Sustainable Dev. Mountain Territories. 14 (3), 468–478. https://doi.org/10.21177/1998-4502-2022-14-3-468-478 (2022).

Gao, P. et al. Enhancing the capacity of large-scale ball mill through process and equipment optimization: an industrial test verification. Adv. Powder Technol. 31 (5), 2079–2091. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apt.2020.03.001 (2020).

Khetagurov, V. N., Kamenetsky, E. S., Gegelashvili, M. V. & Marzoev, A. T. Granulometric composition study of fine product obtained by dolomite grinding in a centrifugal mill of vertical type. Sustainable Dev. Mountain Territories. 16 (1), 197–204. https://doi.org/10.21177/1998-4502-2024-16-1-197-204 (2024).

Atrushkevich, D. Y. V. & Adamova, V. A. Determination of damping coefficient of shock impulse for rocks grinding process. Sustainable Dev. Mountain Territories. 14 (4), 702–710. https://doi.org/10.21177/1998-4502-2022-14-4-702-710 (2022).

Peng, Z., Doroodchi, E. & Moghtaderi, B. Heat transfer modelling in discrete element method (DEM)-based simulations of thermal processes: theory and model development. Progress Energy Comb. Sci. 79, 100847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pecs.2020.100847 (2020).

Kieckhefen, P. et al. Possibilities and limits of computational fluid dynamics–discrete element method simulations in process engineering: a review of recent advancements and future trends. Ann. Rev. Chem. Biomolec Eng. 11, 397–422. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-110519-075414 (2020).

Hallquist, J. O. LS-DYNA Keyword User’s Manual. 2, 2097 (Livermore: Livermore Software Technol. Corpor., 2007).

Johnson, G. R. & Holmquist, T. J. A computational constitutive model for brittle materials subjected to large strains, high strain rates, and high pressures. In Shock Wave and High-Strain-Rate Phenomena in Materials 1075–1082 (CRC Press,1992).

Johnson, G. R. & Holmquist, T. J. An improved computational constitutive model for brittle materials. AIP Conf. Proc. Am. Inst. Phys. 309 (1), 981–984. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.46199 (1994).

Cronin, D. S. et al. Implementation and validation of the Johnson-Holmquist ceramic material model in LS-Dyna. In Proc. 4th Eur. LS-DYNA Users Conf, vol. 1 47–60 (2003).

Monaghan, J. J. Smoothed particle hydrodynamics. Rep. Progress phys. 68 (8), 1703. https://doi.org/10.1088/0034-4885/68/8/R01 (2005).

Doroszuk, B. et al. Calibrating the digital twin of a laboratory ball mill for copper ore milling: integrating computer vision and discrete element method and smoothed particle hydrodynamics (DEM-SPH) simulations. Minerals 14 (4), 407. https://doi.org/10.3390/min14040407 (2024).

Baranowski, P. et al. Fracture and fragmentation of dolomite rock using the JH-2 constitutive model: parameter determination, experiments and simulations. Int. J. Impact Eng. 140, 103543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2020.103543 (2020).

Mishra, S. et al. High strain rate response of rocks under dynamic loading using split Hopkinson pressure bar. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 36, 531–549. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10706-017-0345-2 (2018).

Balakrishnan, K., Sharma, A. & Ali, R. Comparison of explicit and implicit finite element methods and its effectiveness for drop test of electronic control unit. Proc. Eng. 173, 424–431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2016.12.042 (2017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, VAC, YVD; methodology, DAZ, AAK; software, LS; validation, RVK; formal analysis, DAZ, AAK; investigation, VVK, AIK; resources, VVK, AIK; data curation, RVK; writing—original draft preparation, YVD, NVM, DAZ, AAK, RVK; visualization, VVK, AIK; project administration, VAC, YVD; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chanturia, V.A., Dmitrak, Y.V., Kravtsov, A.A. et al. Digital simulation of rock grinding process in ball mill. Sci Rep 15, 45653 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30289-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30289-7