Abstract

Soil erosion poses a major threat to sustainable land use in Ethiopia’s highland regions, where steep terrain and expanding agriculture accelerate environmental degradation. This study assesses erosion susceptibility in the Gubalafto district using a spatially adaptive modeling approach—Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR)—integrated with remote sensing and GIS techniques. High-resolution terrain data (12.5 × 12.5 m) were used to derive key topographic and hydrological indicators, including slope, LS factor, curvature, valley depth, channel network base level, channel network distance, and wetness index. The GWR model revealed significant spatial variation, with erosion hotspots concentrated in steep, sparsely vegetated areas near drainage networks. Validation metrics confirmed the model’s reliability and spatial sensitivity. The resulting erosion susceptibility map offers a decision-support tool for targeted watershed interventions. It identifies priority zones for terracing, reforestation, and land-use regulation, enabling more efficient allocation of conservation resources. The key finding is that slope, LS factor, and proximity to drainage channels are the dominant predictors of erosion, providing a spatially precise framework for sustainable land management in vulnerable highland ecosystems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Soil erosion is a persistent environmental challenge that undermines land productivity, disrupts hydrological systems, and accelerates ecological degradation, particularly in developing countries where conservation infrastructure is limited and land is intensively cultivated1,2. Ethiopia’s northern highlands, including the Gubalafto district, are especially vulnerable due to steep terrain, variable rainfall, and unsustainable land use practices3,4.

Over the past two decades, erosion susceptibility mapping has increasingly relied on GIS and remote sensing techniques, often coupled with statistical or multi-criteria decision-making models such as AHP, MIF, and RUSLE5,6,7. While these approaches have proven useful, they commonly assume spatial stationarity—treating predictor relationships as uniform across landscapes—and often suffer from scale mismatches, coarse data resolution, and limited capacity to capture localized terrain dynamics2,8. These limitations are particularly pronounced in topographically diverse agro-ecological settings like Ethiopia’s highlands.

This study addresses a critical gap in erosion modeling: the lack of spatially adaptive techniques that account for local variations in terrain and hydrological influence. Specifically, it integrates high-resolution terrain indices (12.5 × 12.5 m) with Sentinel-2 satellite imagery and applies Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR) to quantify spatially varying relationships between erosion drivers and hotspot intensity. GWR allows regression coefficients to vary across space, capturing localized interactions that global models overlook9,10. The selected predictors—slope, LS factor, curvature indices, valley depth, wetness index, and channel network metrics—were derived from DEM and remote sensing data, chosen for their documented relevance in erosion processes11,12.

The objectives of this study are threefold: (1) to derive key topographic and hydrological indices from DEM and satellite imagery; (2) to apply GWR to model spatially varying erosion susceptibility across the Gubalafto district; and (3) to produce a high-resolution erosion risk map that supports targeted conservation planning.

By addressing the limitations of stationarity and scale mismatch, this research contributes a spatially precise, data-driven framework for erosion assessment in highland agro-ecological zones. The findings offer practical guidance for land managers and policymakers seeking to prioritize interventions such as terracing, reforestation, and land-use regulation in erosion-prone areas.

Study area

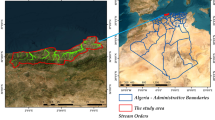

Gubalafto district is located in the North Wollo Zone of the Amhara National Regional State in northern Ethiopia. Geographically, it lies between latitudes 11°30′ to 11°50′ N and longitudes 39°30′ to 39°50′ E, encompassing a diverse landscape that ranges from rugged highlands to deeply incised valleys. The district covers an area of approximately 1,200 square kilometers and is part of the greater Tekeze River basin, which drains into the Nile system.

The topography of Gubalafto is highly variable, with elevations ranging from below 1,500 m in the lowlands to over 3,000 m in the highlands (Fig. 1). This altitudinal gradient contributes to significant climatic and ecological diversity, influencing land use patterns and erosion processes. The region experiences a bimodal rainfall regime, with the majority of precipitation occurring during the summer months. Rainfall intensity and variability, combined with steep slopes and limited vegetation cover, make the area particularly susceptible to soil erosion3,4. Land use in Gubalafto is dominated by subsistence agriculture, with crops such as teff, barley, and sorghum cultivated on terraced and sloped fields. Deforestation, overgrazing, and expansion of farmland have led to widespread land degradation. Despite efforts to implement soil conservation measures, erosion remains a persistent challenge, threatening both agricultural productivity and watershed health. This study focuses on modeling erosion susceptibility across the district to support targeted land management interventions.

Methodology

This study was conducted in Gubalafto Woreda, situated in the northern Ethiopian highlands, a region marked by steep terrain, variable rainfall patterns, and widespread land degradation. The area’s geomorphological complexity and hydrological dynamics make it particularly vulnerable to soil erosion, necessitating a spatially nuanced approach to modeling erosion susceptibility. To address this, the study employed Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR), a spatially adaptive modeling technique that captures local variations in the relationships between erosion and its driving factors.

The foundation of the analysis was a high-resolution Digital Elevation Model (DEM) obtained from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM), which provided the basis for deriving a suite of topographic indices. These indices were selected based on their relevance to erosion processes and their capacity to reflect terrain-driven hydrological behavior. Using QGIS and SAGA GIS, the DEM was processed to extract slope, profile curvature, plan curvature, LS factor (slope length and steepness), topographic wetness index (TWI), valley depth, channel network base level (CNBL), and channel network distance. Each of these parameters plays a distinct role in influencing erosion. For instance, slope and LS factor are directly linked to runoff velocity and sediment transport, while curvature indices affect flow convergence and divergence, which in turn modulate erosion intensity.

Slope values were calculated in degrees and categorized into four classes, ranging from gentle slopes to steep inclines. Steeper slopes were assumed to facilitate faster runoff and higher erosion potential, consistent with findings from Sun et al.13. Profile curvature was derived to assess the acceleration or deceleration of flow along the slope, with convex profiles indicating zones of increased erosion risk. Plan curvature, on the other hand, was used to evaluate lateral flow behavior, where positive values suggest convergent flow paths that concentrate runoff and enhance erosive force, as discussed by Cheng et al.14.

The LS factor was computed to represent the combined effect of slope gradient and slope length, a critical determinant in the Revised Universal Soil Loss Equation (RUSLE). Higher LS values typically correspond to longer and steeper slopes, which are more susceptible to erosion. The topographic wetness index (TWI) was included to capture the potential for water accumulation in terrain depressions. Areas with high TWI values are prone to saturation, reducing soil cohesion and increasing vulnerability to erosion, particularly during intense rainfall events11.

Valley depth was calculated to quantify the vertical distance between valley bottoms and surrounding terrain. This metric reflects the degree of incision and the concentration of erosive forces within drainage channels. Similarly, channel network base level (CNBL) was used to represent the elevation of stream outlets, influencing upstream erosion dynamics. Lower CNBL values typically indicate areas where erosive energy is concentrated. Channel network distance was also considered, as proximity to drainage channels affects flow accumulation and sediment transport. Areas closer to channels are more likely to experience concentrated runoff and higher erosion rates12.

To model the spatial relationship between erosion hotspots and the aforementioned variables, Geographically Weighted Regression was employed. Unlike traditional regression models that assume spatial stationarity, GWR allows regression coefficients to vary across space, thereby capturing localized interactions between predictors and the response variable. The dependent variable in this study was erosion hotspot intensity, derived from a composite index of terrain characteristics. The independent variables included all DEM-derived indices.

The GWR model was implemented using the spgwr package in R, with bandwidth selection optimized through the Akaike Information Criterion corrected (AICc) method. The model equation is expressed as:

\(yi\) : Dependent Variable (Soil erosion) at location i.

\(xik\) : Explanatory Variables (topographical indices)

\(\beta k\left( {ui,vi} \right)\) : Coefficients of the explanatory variables, which vary spatially based on the location \(\:ui,vi\).

\(\:\epsilon\:i:\) Random error term.

This formulation enables the model to account for spatial heterogeneity in erosion processes, which is particularly important in topographically diverse regions like Gubalafto.

Model diagnostics included local R² values, condition numbers, standardized residuals, and standard errors. High local R² values indicated strong explanatory power in specific regions, while low condition numbers confirmed the absence of multicollinearity among predictors. Residuals were examined for spatial autocorrelation using Global Moran’s I, calculated as:

Where \(\:{z}_{i}{z}_{\dot{J}}\) are standardized residuals and\(\:\:{\omega\:}_{i,J}\) is the spatial weight matrix. A near-zero Moran’s I value with non-significant p-values suggested that residuals were randomly distributed, validating the robustness of the GWR model15.

The final erosion susceptibility map was generated by integrating the spatially varying coefficients with the thematic layers. Areas with high LS factor, positive curvature indices, and elevated TWI values emerged as erosion hotspots. These zones were predominantly located along steep slopes and near drainage channels, consistent with previous studies in similar environments3,6. Conversely, regions with gentle slopes, dense vegetation, and low soil erodibility exhibited minimal erosion risk.

Erosion hotspots were delineated using a composite index derived from normalized DEM-based parameters including slope, LS factor, curvature, valley depth, and wetness index. Each layer was reclassified using fuzzy membership functions and weighted based on expert judgment and literature precedence. The integrated erosion susceptibility index was then thresholded into four classes—low, moderate, high, and severe—using natural breaks (Jenks optimization). Satellite imagery from Sentinel-2 (10 m resolution) was used to extract land cover features, aiding in the refinement of hotspot zones. This multi-criteria approach ensured spatial precision and facilitated the identification of priority areas for conservation planning.

Prior to susceptibility modeling, a soil erosion intensity map was generated using a direct terrain-based approach rather than a process-based erosion dynamics model. This decision was guided by the study’s aim to capture spatial variability in erosion risk using high-resolution topographic indicators. DEM-derived parameters—including slope, LS factor, curvature indices, valley depth, and wetness index—were normalized and integrated into a composite erosion index using fuzzy logic and expert-assigned weights. The resulting index was classified into four erosion intensity categories (low, moderate, high, severe) using natural breaks (Jenks optimization). No empirical soil loss model (e.g., RUSLE) was applied, as such models require extensive field calibration and soil property data, which are limited in the study region. Instead, the direct susceptibility approach was deemed appropriate for identifying erosion-prone zones based on terrain-driven hydrological behavior. This method aligns with previous studies in similar highland contexts and allows for spatially adaptive modeling using Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR), which captures localized relationships between terrain variables and erosion intensity.

To evaluate the predictive accuracy of the proposed soil erosion model, twenty seven soil loss rate samples were collected from various georeferenced locations across the study area. These samples were superimposed on the erosion intensity map, which classifies the landscape into four categories: low, moderate, high, and severe erosion. Model validation was performed using a Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve, comparing true positive and false positive rates. The Area Under the Curve (AUC) was calculated to quantify model performance. An AUC value of 0.785 was obtained, indicating a strong ability of the model to differentiate between erosion severity levels.

All spatial analyses were conducted using QGIS 3.28 for raster processing and map visualization, while statistical modeling and diagnostics were performed in R. This integrated approach allowed for a comprehensive assessment of erosion dynamics, offering valuable insights for targeted land management and conservation planning in the Gubalafto district (Fig. 2).

The proposed methodology introduces a novel geospatial framework for identifying soil erosion hotspots using geographically weighted regression (GWR). Unlike traditional global models, GWR allows for location-specific parameter estimation, capturing spatial heterogeneity in erosion drivers such as slope, curvature, and elevation. The process begins with rigorous data preparation, correcting spatial inconsistencies and standardizing resolution to 12.5 × 12.5 m, ensuring analytical precision. The erosion hotspot map is validated using spatial autocorrelation and ROC curve analysis, enhancing both statistical and spatial reliability. A key innovation is the use of local R² and residual diagnostics, which reveal micro-scale model performance and help identify outliers. This spatially adaptive approach enables more accurate erosion risk mapping and supports targeted land management interventions. By integrating high-resolution topographic indices, spatial diagnostics, and localized regression modeling, the methodology offers a scalable, data-driven solution for erosion assessment across diverse landscapes.

Results

The spatial analysis and Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR) modeling provided a detailed understanding of erosion susceptibility across the Gubalafto district. The results reveal significant spatial heterogeneity in erosion drivers, with distinct patterns emerging from the topographic, and hydrological, variables. Figure 1 illustrates the location and elevation of the study area, highlighting the altitudinal variation that contributes to differential erosion processes. Elevation gradients, ranging from valley bottoms to steep escarpments, influence runoff velocity and sediment transport, consistent with findings from Nyssen et al.4 and Haregeweyn et al.3.

The thematic layers derived from the DEM (Fig. 3a–h) show considerable variation in terrain attributes. Slope values range from near-flat zones to inclines exceeding 80°, with steeper slopes concentrated in the eastern and southwestern parts of the district. These areas correspond to high LS factor values, indicating increased erosion potential due to longer and steeper flow paths. The LS factor map (Fig. 3d) aligns with previous studies that emphasize the role of slope steepness in accelerating erosion7,13.

(a) Slope (degrees); (b) Profile curvature; (c) Plan curvature; (d) Topographic LS factor; (e) Topographic Wetness Index (TWI); (f) Valley Depth (m); (g) Channel Network Base Level (CNBL, m); (h) Channel Network Distance (m); (i) Hotspots of soil erosion; (j) Coefficient of slope; (k) Coefficient of profile curvature; and (l) Coefficient of plan curvature.

Curvature indices further refine the understanding of flow behavior. Profile curvature (Fig. 3b) reveals convex zones along ridgelines, which are associated with flow acceleration and sediment detachment. Plan curvature (Fig. 3c) identifies convergent flow zones, particularly in mid-slope areas, where runoff tends to concentrate. These curvature patterns are consistent with the erosion-prone zones identified by Cheng et al.14 and Svoray et al.16, who demonstrated that positive curvature values often coincide with gully initiation and surface instability.

The Topographic Wetness Index (TWI) map (Fig. 3e) shows high values in valley bottoms and depressions, indicating zones of potential saturation. These areas are prone to soil weakening and detachment during heavy rainfall events, as supported by Buchanan et al.11. Valley depth (Fig. 3f) and Channel Network Base Level (Fig. 3g) maps reveal deeply incised drainage systems, particularly in the central and southern regions. These features suggest concentrated erosive forces and sediment transport pathways, echoing observations from Arabameri et al.17 and Guzman et al.12.

Channel Network Distance (Fig. 3h) highlights proximity to stream channels, with lower values indicating areas more exposed to concentrated runoff. These zones, often adjacent to cropland and bare ground, exhibit heightened erosion risk due to minimal vegetative cover and frequent disturbance. The spatial distribution of land use categories reinforces this pattern. Cropland and bare ground dominate the mid-elevation zones, while forested areas are confined to higher altitudes. This distribution mirrors the erosion susceptibility patterns reported by Anderson18 and Kakembo and Rowntree19, who emphasized the protective role of vegetation in stabilizing soil.

The GWR model outputs (Figs. 3i–l and 4a–e) provide localized regression coefficients for each predictor variable. The coefficient map for slope (Fig. 3j) shows strong positive relationships in the eastern escarpments, indicating that slope steepness is a dominant erosion driver in these areas. Similarly, the LS factor coefficient map (Fig. 4a) reveals high values in regions with elongated flow paths, reinforcing its role in sediment mobilization. The curvature coefficient maps (Fig. 3k and l) show spatially variable effects, with plan curvature exerting a stronger influence in convergent zones and profile curvature being more significant in convex terrain.

The TWI coefficient map (Fig. 4b) indicates that wetness contributes to erosion primarily in saturated lowlands, where soil cohesion is reduced. Valley depth and CNBL coefficients (Fig. 46c and d) show positive associations in deeply incised areas, suggesting that topographic confinement enhances erosive energy. The Channel Network Distance coefficient map (Fig. 4e) highlights the importance of proximity to drainage channels, with closer areas exhibiting stronger erosion correlations.

Model diagnostics (Figs. 4f–i) confirm the robustness of the GWR approach. Local R² values (Fig. 4g) range from 0.45 to 0.89, indicating strong explanatory power in most regions. High R² zones coincide with areas of steep slopes and active land use, suggesting that the selected predictors effectively capture erosion dynamics. Condition numbers (Fig. 4f) remain below critical thresholds, indicating minimal multicollinearity among variables. Standard errors (Fig. 4h) are low in high R² zones, further validating model reliability. Standardized residuals (Fig. 4i) show a random spatial pattern, with no significant clustering, as confirmed by a near-zero Global Moran’s I value. This suggests that the model adequately accounts for spatial autocorrelation, consistent with the validation framework proposed by Nyssen et al.15. GWR-Derived Coefficients and Diagnostics for Erosion Modeling are shown in Table 1.

The final erosion hotspot map (Fig. 3i) integrates the GWR coefficients with thematic layers to delineate zones of high susceptibility. These hotspots are predominantly located in the eastern and southwestern parts of the district, where steep slopes, high LS factors, and minimal vegetation converge. These findings align with previous assessments in similar Ethiopian landscapes6,8 reinforcing the need for targeted conservation interventions in these zones.

Figure 5a illustrates the spatial distribution of soil erosion severity across the study region, integrating field-based soil loss measurements with the modeled erosion zones. The map categorizes the landscape into four erosion intensity classes: low, moderate, high, and severe. These classifications are derived from a predictive model that incorporates topographic, climatic, and land cover variables. Superimposed on this erosion map are sample points represented by triangular markers, each labeled with its corresponding soil loss rate in tons per hectare per year (t/ha/yr). These sample points serve as ground-truth data, enabling a direct comparison between observed erosion rates and model predictions.

The spatial alignment between sample values and modeled zones reveals a strong correlation. Sample points with high soil loss rates—such as 125, 140, and 165 t/ha/yr—are consistently located within areas classified as severe erosion. Conversely, points with lower values—such as 57 and 68 t/ha/yr—are found in zones identified as low erosion. This pattern confirms the model’s ability to accurately reflect the geomorphological and land-use factors influencing erosion dynamics. The geographic spread of sample points across varied terrain types, including escarpments, valleys, and cultivated slopes, further validates the model’s sensitivity to environmental gradients. The inclusion of latitude and longitude coordinates along the map’s borders enhances spatial referencing, while the scale bar provides context for interpreting distances and erosion extents. Overall, Fig. 5a demonstrates the model’s effectiveness in capturing real-world erosion patterns and supports its application in land degradation assessment and conservation planning.

Figure 5b illustrates the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve used to evaluate the model’s classification performance. The curve plots the true positive rate against the false positive rate, with a dashed diagonal line representing random guess performance. The solid red curve, labeled “Soil_Erosion,” demonstrates a clear deviation above the random line, indicating predictive strength. The Area Under the Curve (AUC) value of 0.785 confirms that the model performs significantly better than chance, with a high degree of sensitivity and specificity in distinguishing between erosion severity classes. This AUC score reflects the model’s robustness in translating geospatial inputs into accurate erosion predictions. Together, the spatial overlay and ROC analysis validate the model’s effectiveness in both geographic representation and statistical classification, supporting its application in erosion risk assessment and land management planning.

Overall, the results demonstrate that erosion in Gubalafto is driven by a complex interplay of terrain, and hydrology. The spatial variability captured by GWR modeling offers a nuanced understanding of these interactions, enabling more precise identification of vulnerable areas. This approach not only enhances predictive accuracy but also provides a valuable tool for land managers and policymakers seeking to mitigate erosion and promote sustainable land use in the Ethiopian highlands.

Discussion

The spatial modeling of erosion susceptibility in Gubalafto district using Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR) has revealed a complex and spatially variable interplay between topographic, and hydrological, factors. The results underscore the importance of localized terrain characteristics in shaping erosion dynamics, a finding that aligns with and extends previous research conducted in similar highland environments across Ethiopia and other regions.

Slope and LS factor

One of the most striking outcomes of this study is the spatial heterogeneity in the influence of slope and LS factor on erosion susceptibility. As shown in Fig. 3a and d, steep slopes and elongated flow paths dominate the eastern and southwestern portions of the district. These areas also exhibit high regression coefficients for slope and LS factor (Figs. 3j and 4a), indicating a strong positive relationship with erosion intensity. This observation is consistent with the findings of Saha et al.7, who demonstrated that slope steepness and slope length are among the most influential factors in predicting soil erosion in agricultural watersheds. Similarly, Sun et al.13 emphasized the role of topographic gradients in accelerating runoff and sediment transport on the Loess Plateau in China, a region with geomorphological parallels to the Ethiopian highlands.

Curvature

The curvature indices derived from the DEM provide further insight into the flow dynamics that contribute to erosion. Profile curvature (Fig. 3b) and plan curvature (Fig. 3c) reveal zones of convexity and convergence, respectively, which are associated with increased flow acceleration and concentration. The corresponding coefficient maps (Fig. 3k and l) show that these curvature features exert spatially variable influences on erosion, with plan curvature being particularly significant in mid-slope areas. This finding supports the work of Cheng et al.14, who formulated variable source areas as a bivariate process and found that curvature plays a critical role in identifying runoff-producing zones. Svoray et al.16 also demonstrated that curvature thresholds are effective predictors of gully initiation, especially when combined with other terrain indices.

Topographic wetness index

The Topographic Wetness Index (TWI), shown in Fig. 3e, highlights areas wetness index.potential saturation, primarily in valley bottoms and depressions. These zones are characterized by high moisture accumulation, which can weaken soil structure and increase susceptibility to erosion during rainfall events. The GWR coefficient map for TWI (Fig. 4b) confirms its positive association with erosion in these saturated areas. Buchanan et al.11 evaluated various wetness indices across agricultural landscapes in New York and found that TWI was a reliable indicator of erosion-prone zones, particularly in areas with poor drainage and high runoff potential.

Valley depth and channel network base level

Valley depth and Channel Network Base Level (Fig. 3f and g) further illustrate the erosive potential of incised drainage systems. Deep valleys and low base levels concentrate flow energy, enhancing sediment transport and channel erosion. The positive regression coefficients for these variables (Fig. 4c and d) suggest that topographic confinement amplifies erosive forces. Arabameri et al.17 used similar terrain metrics in their study of gully erosion in Iran and concluded that valley depth and base level are critical determinants of erosion intensity. Guzman et al.12 also observed that suspended sediment concentrations in Ethiopian highlands are closely linked to channel morphology and flow dynamics.

Channel network distance

Channel Network Distance (Fig. 3h) provides a measure of proximity to drainage channels, with lower values indicating areas more exposed to concentrated runoff. The coefficient map (Fig. 4e) shows a strong inverse relationship between distance and erosion, confirming that areas closer to channels are more vulnerable. This pattern is consistent with the findings of Berhanu et al.6, who developed a GIS-based hydrological zone map of Ethiopia and identified proximity to streams as a key factor in erosion modeling. Similarly, Haregeweyn et al.3 emphasized the role of drainage density and channel proximity in shaping erosion patterns across Ethiopian watersheds.

Land use and land cover

Land use and land cover also play a significant role in modulating erosion risk. The spatial distribution of land use categories, as reflected in the thematic layers and erosion hotspot map (Fig. 3i), shows that cropland and bare ground are concentrated in mid-elevation zones, where erosion susceptibility is highest. These areas lack sufficient vegetative cover to stabilize the soil, making them particularly vulnerable to detachment and transport. Anderson18 established a foundational classification system for land use and land cover, highlighting the erosion implications of different categories. Kakembo and Rowntree19 further demonstrated that communal lands with intensive cultivation and minimal vegetation are prone to severe erosion, a finding that resonates with the patterns observed in Gubalafto.

GWR diagnostics and validation

The GWR diagnostics presented in Fig. 4f and i validate the robustness of the model. Local R² values (Fig. 4g) indicate strong explanatory power in regions with pronounced topographic variation and active land use. The absence of multicollinearity, as evidenced by low condition numbers (Fig. 4f), and the random distribution of standardized residuals (Fig. 4i) confirm the model’s reliability. The use of Global Moran’s I to assess spatial autocorrelation yielded near-zero values, suggesting that the residuals are spatially independent and that the model effectively captures the underlying spatial processes. These validation results are in line with the methodological rigor advocated by Nyssen et al.15 in their assessment of gully erosion rates in northern Ethiopia.

The integration of field-based soil loss samples with the modeled erosion map provides a robust framework for evaluating spatial erosion dynamics. The spatial overlay in Fig. 5a reveals a compelling alignment between modeled erosion zones and field-measured soil loss rates, offering strong empirical support for the model’s predictive reliability. Sample points with exceptionally high soil loss rates—such as 140, 165, and 125 t/ha/yr—are predominantly located in topographically exposed regions, likely steep slopes or escarpments, where runoff velocity and erosive force are naturally amplified. These areas correspond to the model’s most critical erosion zones, suggesting that the predictive framework effectively captures terrain-driven erosion dynamics.

Conversely, sample points with lower soil loss rates—such as 57 and 68 t/ha/yr—are situated in relatively stable geomorphic settings, possibly valley bottoms or gently sloping agricultural lands. These zones are typically characterized by higher infiltration capacity, vegetative cover, and reduced surface runoff, which collectively mitigate erosion intensity. The model’s ability to distinguish these low-impact zones from high-risk areas demonstrates its sensitivity to spatial heterogeneity and landform variation.

Intermediate values, such as those around 85–110 t/ha/yr, appear in transitional landscapes—zones where slope, land cover, and rainfall interact in complex ways. These areas may be undergoing land-use change or experiencing seasonal erosion pulses, and their classification as moderate or high erosion zones reflects the model’s nuanced handling of such variability.

Importantly, the geographic spread of sample points across the full spectrum of erosion classes ensures that the validation is not biased toward any particular terrain type. This spatial diversity strengthens the credibility of the model and confirms its applicability for regional-scale erosion risk assessment. The observed values not only validate the model’s outputs but also highlight priority zones for conservation interventions, such as reforestation, terracing, or erosion control structures.

Figure 5a demonstrates that the model effectively captures the spatial heterogeneity of erosion intensity, with sample points falling predominantly within high and severe erosion zones. This alignment suggests that the model is sensitive to topographic and land use variations that drive erosion processes. The validation results in Fig. 5b further reinforce the model’s predictive strength. An AUC of 0.785 indicates a good balance between sensitivity and specificity, meaning the model can reliably identify areas at risk without excessive false positives. This level of accuracy is particularly valuable for watershed managers and planners seeking to implement targeted soil conservation strategies.

Validation of the soil erosion model was strengthened through the combined use of Google Earth imagery and systematic field visits. Google Earth provided high‑resolution, time‑series observations that allowed us to visually inspect erosion features across the study region. By examining historical imagery, we were able to identify progressive changes in land cover, expansion of gullies, and the appearance of bare soil patches, all of which corresponded closely with the model’s predicted high‑risk zones. This temporal dimension was particularly valuable in confirming that areas classified as severe erosion were indeed undergoing continuous degradation, while stable zones retained vegetation cover and showed minimal surface disturbance.

Complementing these remote observations, targeted field visits were conducted to ground‑truth the model outputs. During these visits, erosion features such as rills, gullies, and sediment deposits were systematically documented and compared against the predicted erosion classes. Measurements of slope gradients and soil conditions were taken to verify the accuracy of modeled parameters, while photographic evidence provided a direct record of landscape conditions. The convergence of Google Earth imagery with field observations confirmed that the model reliably captured both the spatial distribution and severity of erosion. This dual validation approach ensured that the predictive framework was not only statistically sound but also physically representative of real‑world conditions, enhancing its credibility for practical land management and conservation planning.

Comparing these findings with other regional and international studies reveals both commonalities and unique insights. For instance, Setegn et al.20 conducted a spatial delineation of erosion vulnerability in the Lake Tana Basin and found that slope, land use, and drainage proximity were dominant factors—echoing the results of this study. However, the use of GWR in the present analysis offers a more refined understanding of spatial variability, allowing for localized interpretation of regression coefficients. This contrasts with traditional global models that assume uniform relationships across space, potentially overlooking critical nuances.

In the broader context of erosion modeling, the integration of GWR with high-resolution terrain data represents a methodological advancement. While previous studies such as those by Amiri et al.10 and Arabameri et al.17 have employed machine learning algorithms to model erosion, the spatial adaptiveness of GWR provides a unique advantage in capturing local variations. This is particularly important in heterogeneous landscapes like the Ethiopian highlands, where erosion drivers can differ markedly over short distances.

The implications of these findings are significant for land management and conservation planning. The identification of erosion hotspots, particularly in areas with steep slopes, high LS factors, and minimal vegetation, provides a basis for targeted interventions. Conservation measures such as reforestation, terracing, and controlled grazing can be prioritized in these zones to mitigate erosion and enhance land productivity. The results also underscore the need for integrated watershed management approaches that consider both biophysical and socio-economic factors, as advocated by Bewket and Conway8 and Ananda and Herath1.

The GWR-based modeling of erosion susceptibility in Gubalafto district has provided a comprehensive and spatially nuanced understanding of the factors driving land degradation. By capturing local variations in terrain, hydrology, and land use, the study offers valuable insights for sustainable land management in the Ethiopian highlands. The methodological approach and findings contribute to the growing body of literature on spatial erosion modeling and demonstrate the potential of geospatial techniques in addressing environmental challenges.

Limitations of this study

While this study presents a robust spatially adaptive framework for modeling erosion susceptibility using Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR), several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the analysis relies heavily on terrain-derived parameters from DEM and satellite imagery, which, although high-resolution, may not fully capture subsurface geological variability or soil composition. The absence of detailed soil texture, land management practices, and socio-economic data limits the model’s ability to account for anthropogenic influences on erosion. Additionally, the use of fuzzy logic and expert-based weighting introduces subjectivity into the composite index, which may affect reproducibility across different regions. The GWR model, while effective in capturing spatial heterogeneity, assumes linear relationships and may not accommodate complex, nonlinear interactions among variables. Furthermore, validation was based on a limited number of field samples, which may not represent the full range of erosion dynamics across the district. Seasonal variability in rainfall and land cover was not explicitly modeled, potentially affecting temporal accuracy. Future studies should integrate multi-temporal datasets, expand field validation, and incorporate socio-environmental variables to enhance predictive reliability and policy relevance.

Conclusion

This study employed Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR) to model soil erosion susceptibility in the Gubalafto district, revealing the spatially variable influence of topographic and hydrological factors. By integrating high-resolution DEM-derived indices—such as slope, curvature, LS factor, TWI, valley depth, and channel network metrics data, the analysis identified erosion hotspots concentrated in steep, poorly vegetated, and hydrologically active zones. The localized regression coefficients provided by GWR offered a nuanced understanding of erosion dynamics, surpassing the limitations of global models that assume spatial uniformity.

The findings underscore the critical role of terrain configuration and land cover in shaping erosion risk, aligning with previous studies in Ethiopia and beyond. The model’s robustness, validated through diagnostics and spatial autocorrelation tests, confirms its suitability for complex landscapes like the northern highlands. These insights are vital for guiding targeted soil conservation strategies, such as reforestation, terracing, and sustainable land use planning.

Ultimately, this research demonstrates the power of spatially adaptive modeling in environmental assessment. It provides a foundation for future studies that incorporate dynamic variables and community-based approaches. As land degradation continues to threaten livelihoods and ecosystems, tools like GWR offer a pathway toward more informed, localized, and effective watershed management in erosion-prone regions.

Data availability

The data will be provided based on a request (Imran Ahmad: wonder_env@yahoo.com).

References

Ananda, J. & Herath, G. Soil erosion in developing countries: a socio-economic appraisal. J. Environ. Manag. 68 (4), 343–353 (2003).

Lal, R. Soil degradation by erosion. Land. Degrad. Dev. 12(6), 519–539 (2001).

Haregeweyn, N. T. et al. Soil erosion and conservation in Ethiopia. Prog Phys. Geogr. Earth Environ. 39(6), 750–774 (2015).

Nyssen, J. et al. Rainfall erosivity and variability in the Northern Ethiopian highlands. J. Hydrol. 311(1–4), 172–187 (2005).

Bahadur, K. K. Mapping soil erosion susceptibility using remote sensing and GIS: a case of the upper Nam Wa Watershed, Nan Province, Thailand. Environ. Geol. 57 (3), 695–705 (2009).

Berhanu, B., Melesse, A. M. & Seleshi, Y. J. C. GIS-based hydrological zones and soil geo-database of Ethiopia. Catena 104, 21–31 (2013).

Saha, S., Gayen, A., Pourghasemi, H. R. & Tiefenbacher, J. P. Identification of soil erosion-susceptible areas using fuzzy logic and analytical hierarchy process modeling in an agricultural watershed of Burdwan district, India. Environ. Earth Sci. 78 (23), 1–18 (2019).

Bewket, W. & Conway, D. A note on the Temporal and Spatial variability of rainfall in the drought-prone Amhara region of Ethiopia. Int. J. Climatol. 27 (11), 1467–1477 (2007).

Fotheringham, A. S., Brunsdon, C. & Charlton, M. Geographically weighted regression: the analysis of spatially varying relationships (Wiley, 2002).

Amiri, M., Pourghasemi, H. R., Ghanbarian, G. A. & Afzali, S. F. Assessment of the importance of gully erosion effective factors using the Boruta algorithm and its Spatial modeling and mapping using three machine learning algorithms. Geoderma 340, 55–69 (2019).

Buchanan, B. P. et al. Evaluating topographic wetness indices across central new York agricultural landscapes. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 18 (8), 3279–3299 (2014).

Guzman, C. D., Tilahun, S. A., Zegeye, A. D. & Steenhuis, T. S. Suspended sediment concentration–discharge relationships in the (sub-) humid Ethiopian highlands. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 17 (3), 1067–1077 (2013).

Sun, W., Shao, Q., Liu, J. & Zhai, J. Assessing the effects of land use and topography on soil erosion on the loess plateau in China. Catena 121, 151–163 (2014).

Cheng, X. et al. Improving risk estimates of runoff producing areas: formulating variable source areas as a bivariate process. J. Environ. Manag. 137, 146–156 (2014).

Nyssen, J. et al. Assessment of gully erosion rates through interviews and measurements: a case study from Northern Ethiopia. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 31 (2), 167–185 (2006).

Svoray, T., Michailov, E., Cohen, A., Rokah, L. & Sturm, A. Predicting gully initiation: comparing data mining techniques, analytical hierarchy processes and the topographic threshold. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 37 (6), 607–619 (2012).

Arabameri, A. et al. Spatial modelling of gully erosion using evidential belief function, logistic regression, and a new ensemble of evidential belief function–logistic regression algorithm. Land. Degrad. Dev. 29 (11), 4035–4049 (2018).

Anderson, J. R. A land use and land cover classification system for use with remote sensor data. US Geol. Surv. Prof. Pap 964 (1976).

Kakembo, V. & Rowntree, K. M. The relationship between land use and soil erosion in the communal lands near Peddie Town, Eastern Cape, South Africa. Land. Degrad. Dev. 14, 39–49 (2003).

Setegn, S. G., Srinivasan, R., Dargahi, B. & Melesse, A. M. Spatial delineation of soil erosion vulnerability in the lake Tana Basin, Ethiopia. Hydrol. Process. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.7476 (2009).

Funding

Project of the Key R&D Program of Hebei Province (22327302D).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.A.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, and Supervision. Writing—original draft preparation. Z.P.: Methodology, Reviewing and Editing. M.A.D.: Methodology, Software. M.B., M.K.A., G.F., M.S., Z.M.T., S.A., and G.S.Z.: Reviewing and Editing.Ethical responsibilities of Authors: All authors have read, understood, and complied with the research with responsibility. Authors guarantee that their manuscript is original, does not infringe the copyright of anyone, and has neither been previously published nor is currently under consideration for publication elsewhere.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Peng, Z., Ahmad, I., Dar, M.A. et al. Spatially adaptive modeling of soil erosion susceptibility using geographically weighted regression integrated with remote sensing and GIS techniques. Sci Rep 15, 42894 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30297-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30297-7