Abstract

The study aims to understand a) the prevalence, associated factors and temporal changes in multimorbidity (having 2 or more chronic conditions) in older adults in Singapore. The single-phase, nationwide cross-sectional study employed respondent-level stratified random sampling to recruit the older adults (N = 2010, ≥ 60 years). Analyses included descriptive statistics and multiple logistic regression models with sampling weights. The prevalence of multimorbidity in the current study was 48.4%, compared to 51.5% in 2012 (p = 0.18). The top three prevalent conditions were hypertension (53.7%), diabetes (24.9%), and arthritis (25.5%). The most common combinations were hypertension and diabetes (19.1%), followed by hypertension and arthritis (15.3%), and hypertension and heart problems (9.0%). Older age (75–80 years vs. 60–74 years), ethnicity (Indian and Malay vs. Chinese), education (tertiary vs. no education), disability, and requiring help with Activities of Daily Living (ADL) were associated with higher odds of multimorbidity. Multimorbidity had an inverse relationship with self-perceived health status. While there was no significant temporal change in the prevalence of multimorbidity, the prevalence remained high despite national level campaigns and preventive efforts, which is a cause for concern.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Population ageing is a key demographic event in the 21st century and has multiple impacts on health and economic sectors1. The projected global increase in the proportion of individuals aged 60 and above, from 12% in 2015 to 22% by 2050, underscores the magnitude of this phenomenon1. Ageing involves a decline in physical and mental functions, accompanied by a progressive deterioration of health, leading to higher susceptibility to various diseases1. Older adults face a multitude of health challenges, such as hearing loss, visual impairment, bone, heart, and lung diseases1 collectively contributing to a reduced quality of life. The health status of individuals serves as a determinant for healthcare utilization, and in the context of the ongoing demographic shift, the consequences for healthcare systems become increasingly profound. Increased healthcare utilization among older adults poses challenges such as increased costs, financial burden, health disparities, and lower quality of care 2. As societies struggle with these implications, addressing the healthcare needs of an ageing population becomes paramount for sustaining effective and equitable healthcare systems.

Emerging data on ageing shows the global significance of this phenomenon by shedding light on the prevalence and trends of various chronic conditions, multimorbidity, and its correlates among older adults and its impact on health status. This data is crucial for estimating the multifaceted impacts of ageing, aiding in future planning efforts. A European study, that collected data from 16 countries, revealed a multimorbidity prevalence of 37.3%, with the highest rates observed in Hungary at 51%2. The data showed a significant association between chronic conditions and both primary and secondary healthcare utilization, as well as correlations with depression, functional impairment, and poor health status2. Similarly, an Italian longitudinal study documented a substantial increase in multimorbidity from 20.2% in 2005 to 28% in 2014, accompanied by a doubling in the prevalence of chronic conditions during this period3. This rise in multimorbidity coincided with a surge in healthcare utilization with a 26.4% increase in diagnostic tests. The cumulative burden of chronic conditions has been linked to functional limitations and disability among older adults, as indicated by studies such as those by Kriegsman and colleagues4 and Patel et al5. Moreover, a Canadian study revealed higher multimorbidity prevalence among women, individuals with lower education, poorer psychological health indicators, depression, and disability6. The authors of this study also established that multimorbidity predicts 5-year mortality, with disability acting as a mediating factor in this association. Findings from a 15-year Brazilian longitudinal study among older adults underscored the role of disability as a significant determinant of all-cause mortality7.

Amidst the escalating prevalence of chronic conditions and multimorbidity, emerging evidence shows that those with multimorbidity have higher healthcare utilization and poorer health outcomes8. A comparison of data from 16 European countries showed that multimorbidity is associated with worse self-reported health status and functional capacity2. Understanding the determinants of health status has been a priority, with age, gender, ethnicity, and SES status traditionally employed as determinants of health status9. Johnson and Wolinsky9 constructed a multidimensional model of health status structure, incorporating gender and ethnicity, derived from a nationally representative sample. Their model proposed that the impact of disease on the perceived health status of older adults is mediated by disability and functional limitations, with variations observed based on gender and ethnicity. Given the multifaceted and complex nature of the health status of older adults, further studies are warranted globally to understand the factors influencing their health status.

Singapore, a city-state in Southeast Asia with a land area of 734.3 km², is home to a multiethnic population of 5.9 million10. The proportion of older adults in Singapore nearly doubled from 9% in 2010 to 16.6% in 202211 . Projections indicate a further doubling of this proportion by 2030, positioning Singapore as the tenth-ranked country globally, with 40.4% of individuals estimated to be above 60 years by 205012 . The Wellbeing of Singapore Elderly (WiSE) study conducted in 2012 was a nation-wide cross-sectional study that revealed a significant prevalence of multimorbidity among older adults (60 years and above), reaching 51.5%13. Notably, this figure is nearly twice as high as the population-level prevalence of multimorbidity, which stands at 24.9%14. The methodology and findings from the WiSE 2012 study provided a baseline for temporal comparisons for studying the multimorbidity patterns in Singapore’s older adults, making it an ideal reference point. The study’s approach to data collection, including face-to-face interviews and standardized assessment tools, established a methodological framework that could be replicated in subsequent studies to ensure valid temporal comparisons.

In Singapore, the annual societal cost associated with multimorbidity reached SGD$15,148, a substantial contrast to the SGD$2,806 for individuals without chronic conditions13. Notably, the study identified Indian ethnicity and advanced age as factors linked to higher costs13. The Integrated Screening Programme (ISP), Singapore’s national screening programme, was introduced in 2008 and allowed eligible residents to screen for hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, and breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers. The ISP was renamed to Screen For Life (SFL) in 2013 and enhanced in 2017 with incentives to reduce residents’ out-of-pocket payments for screening tests to improve screening uptake and follow-up15. In 2016, the War on Diabetes (WoD) was launched to create a supportive environment for people in Singapore to lead lives free from diabetes and for those with diabetes to manage the condition well16. ‘Healthier SG’ was implemented in 2023 as a national preventive health programme to encourage residents to enrol with a family doctor, where they would receive regular health screenings, vaccinations, and review of a personalised health plan, with the aim to reduce chronic disease burden and improve population health outcomes17 . ‘Age Well SG’ builds upon this foundation by supporting seniors to remain active, engaged, and independent in their communities. A key initiative under ‘Age Well SG’ is the expansion of Active Ageing Centres (AACs) offering various activities to keep seniors physically active and socially connected18. The current study extends this knowledge by providing updated prevalence estimates, exploring emerging or new risk factors, and evaluating changes in health status over time.

The goal of the current study is to understand a) the prevalence, associated factors and temporal changes in multimorbidity in older adults in Singapore.

Methods

Design

The WiSE study was a nationwide single-phase cross-sectional survey that aimed to determine the prevalence of dementia and depression among the older adults (60 years and older) in Singapore. The study design incorporated cross-sectional analyses of associated factors conducted using 2023 data only, whilst temporal trend analyses compared prevalence between 2012 and 2023. Both surveys employed consistent methodology with no significant changes in data collection procedures that would account for any changes in prevalence.

Sample size and sampling

Disproportionate stratified random sampling was employed based on age (60–74 years; 75–84 years; >85 years) and ethnicity (Chinese, Indian, Malay, and others). Those categorized as others included participants belonging to diverse and heterogenous ethnicities that were not able to be classified under Chinese, Malay or Indian ethnicity. Oversampling was done for various ethnic groups to ensure sufficient representation from minority groups. The sample size was calculated assuming a 10% prevalence of dementia 19, and with a statistical power of 0.8 and a type 1 error of 0.05, a sample size of 2000 older adults was estimated. Survey weights are employed during analysis to account for oversampling and non-response rates.

Participants

The data is derived from the second WiSE study conducted between March 2022 and September 2023, utilizing the same methodology as the earlier one19,20,21. The participants were selected from a national level administrative database, containing the information of all Singaporeans and permanent residents who were 60 years of age or older through a probability sampling. The older adults in the study were recruited together with the caregivers in a 1:1 ratio from the community setting. Data collected from the dyads was required for the 10/66 algorithm to capture the diagnosis of dementia and depression. The 10/66 dementia diagnosis algorithm derives the diagnosis through coefficients generated based on the data collected through Community Screening Instrument for Dementia (CSI-D), the CERAD 10-word list recall task, and the Geriatric Mental State (GMS) examination using a probabilistic approach22. The coefficients were generated from the training datasets across multiple studies conducted by the 10/66 Dementia research group globally. The diagnosis is made when the predicted probability exceeds the predetermined cut offs. The 10/66 dementia diagnosis algorithm was selected because prior studies demonstrated that it was particularly effective in distinguishing dementia in China, Southeast Asia, and India, as well as being acceptable in Latin America23. Participants were eligible if they were aged ≥ 60 years, were Singapore citizens or permanent residents, and could communicate in at least one of the following languages: English, Chinese (Mandarin), Malay, Tamil, or Chinese dialects (Hokkien, Cantonese, or Teochew). Those who were not living in Singapore during the survey period, were institutionalized (e.g., in prison), or were physically or mentally incapable of doing the interview and whose caregivers were unwilling to participate were excluded from the study. Informal caregivers who were over 21 years old were included, while paid caregivers (e.g., foreign domestic workers) were excluded. This is because paid caregivers often provide temporary care to older adults, and they are not involved in the major care decisions of the older adults (definition for the informant). Also, they often lack knowledge of the older adult’s health history, chronic conditions, and long-term health status which affects the reliability of the data.

Procedure

Lay interviewers were trained by the study team members over a period of 2 weeks, which included hands-on training, round-robin discussions with clinicians, learning videos, and mock respondent interviews. At the end of the training, an evaluation was conducted, and those who passed the evaluation were allowed to conduct the interview. A trained study team member attended the initial interviews by the interviewers for quality control and to identify any potential challenges. The contact records of the interviewers were checked weekly, and 20% QC for all interviews was conducted.

All participants received a notification letter detailing the survey at least one week before the visit from the interviewers. Interviews were conducted after obtaining written informed consent. Face-to-face interviews were conducted using computer-assisted personal interviews (CAPI). The survey lasted for 2 to 2.5 hours. A minimum of 10 attempts were made to contact each of the participants.

Ethics declaration

The study procedures were approved by relevant ethics committees (National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board (DSRB) and SingHealth Centralized Institutional Review Board (CIRB) Ref: 2020/01400). All the methods performed in the study were in accordance with the approved protocol and relevant guidelines and regulations stipulated by the ethics committee. All participants received an inconvenience fee for their time and effort as stipulated by the ethics committee.

Assessments

The assessments used in the study were part of the 10/66 assessments, which are well validated across different countries, settings and populations24. All the questionnaires and translations were used with the approval of the group.

Sociodemographic factors

Age, gender, and other sociodemographic information were captured by a simple sociodemographic questionnaire. Homeownership status, lack of financial assets, or financial strains are better proxy measures of the socioeconomic status (SES) of older adults, while education, occupation, and income are more relevant for adults25. Income is not an ideal proxy for SES for the older adults, as it tends to overinflate the income of the group. This happens because some older adults who have not retired are still working, while others who have retired, rely on accumulated wealth such as pension, home ownership or savings, or other non-monetary resources which are hard to quantify. As such, income alone does not accurately reflect the SES of the group of older adults. This is especially true in the Singapore context, as the retirement age is 63 years, and many older adults continue to work post-retirement26. Housing is considered an important determinant of health 27. Rental housing is available from the government through a public rental scheme for those who are unable to purchase their own house and have no other housing options28. Thus, this is a good proxy for the SES of older adults29. According to the classification, low SES will include people who secured rental apartments from the Housing & Development Board (HDB) Singapore.

Health status, self-rated health, and physical health conditions

This information was captured by reading a list of chronic conditions (hypertension, heart trouble or angina, arthritis or rheumatism, stroke, transient ischemic attacks (TIA), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma or breathlessness, depression, diabetes, and cancer) to the participant and asking, ‘Have you ever been told by a doctor that you have any of these conditions?’. For hypertension, heart problems, stroke, TIA, COPD, diabetes, and depression, a binary yes or no response was collected. For asthma, cancer, and arthritis, responses were captured on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (does not have a health problem) to 3 (has a problem and interferes a lot). Responses 1 to 3 were recorded as yes, while 0 was coded as no. Dementia and depression were measured using 10/66 assessments employing the Geriatric Mental State-Automated Geriatric Examination for Computer-Assisted Taxonomy (GMS-AGECAT, 21). Multimorbidity was defined as having two or more of these chronic conditions at the same time. Overall health status was captured using a single item: “How would you rate your overall health in the past 30 days?”. The responses were captured on a 5-point scale from 0 (very good) to 4 (very bad). Scores are then dichotomized and participants who rated very good (0) and good (1) were scored as 1 and those who rated their health as poorer (2–4) were scored as 0. Medical records were not accessed for validating any of these conditions.

Disability

The World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0,30) was used to capture the disability scores among the participants. The scale covers six domains of functioning and includes cognition, mobility, self-care, getting along, life activities, and participation in activities. It is scored on a 5-point scale (0–4), where 0 means no difficulty and 4 indicates extreme difficulty. A total score was used for the summation of the domain scores. A total score greater than 1 was classified as having a disability for the analysis (Rehm, 2000).

Activities of daily living (ADL)

The activities of daily living (ADL) were captured through a caregiver module as part of the 10/66 assessments employing the Geriatric Mental State-Automated Geriatric Examination for Computer-Assisted Taxonomy (GMS-AGECAT, 19). The older adults were not asked these questions, as the study was meant to look at the prevalence of dementia and thus included older adults with dementia who were cognitively incapable of answering these survey questions. The questions measured transportation, communication, toileting, eating, grooming, bathing, and dressing. The caregivers were asked if the older adults required support to perform any of the ADLs that they were previously able to perform. The response options included “no time,” “less than 1 h,” “1–2 hours,” and “more than 2 hours.” ADL impairment would include any time spent assisted on common ADLs (i.e., less than 1 hour or more for any task).

Analysis

Statistical analyses were run using Statistical Analysis Software (SAS) version 9.4. The collected data was first run in the proprietary algorithm from 10/66 (GMS-AGECAT) to obtain an indication for depression and dementia. The processed data was then uploaded into SAS in SPSS format. Scoring of multimorbidity, ADL impairment, disability, self-rated health, and SES was then performed on the imported data in SAS. Descriptive analyses were performed to describe the sociodemographic characteristics, prevalence of health conditions (physical and mental), disability, and ADL of the sample. Means, standard deviations were used to express sociodemographic characteristics of the sample while continuous variables were represented as means and standard deviations. Normality of the continuous outcome variables were assessed through histogram plots, skewness and kurtosis values, and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. We used listwise deletion to handle missing data. Multinomial logistic regression analyses were utilized to determine predictors of the presence of one chronic condition and multimorbidity (two or more chronic conditions). For temporal comparisons, we used data from the WiSE study conducted in 2012. As both studies employed similar sampling strategies and methodologies, meaningful comparisons were possible. Chi-square tests were used to compare prevalence rates between the two time points. An additional pooled multinomial logistic regression analysis was conducted to examine the temporal effects of multimorbidity between 2012 and 2023, controlling for sociodemographic confounders. Univariate analyses for multimorbidity were conducted to identify potential predictors. All independent variables were entered simultaneously into each logistic regression model based on existing theoretical understanding and prior research, allowing for the adjustment of potential confounding effects. Multimorbidity was used as the dependent variable while sociodemographic characteristics, disability, ADL, and self-rated health were used as the independent variables. All analyses were performed using sampling weights adjusting for oversampling, non-response and post stratified to ensure that the survey findings were representative of the Singapore’s older adult population.

Results

Of the 3,808 eligible participants (older adults) approached, 2,010 older adults and 1,798 caregivers were successfully recruited (response rate: 62.7%). Non-participation was attributed to several factors: exhaustion of maximum contact attempts (10 unsuccessful visits), time constraints, security concerns (fear of scams), COVID-19-related apprehensions, familial objections, and lack of interest.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample

The sociodemographic characteristics of the sample demonstrated fair representation from different sociodemographic groups (Table 1) Only 2.6% were in low SES and 22.3% met criteria for disability Table 1.

Health status

Prevalence of chronic conditions and multimorbidity

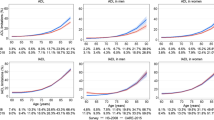

The top three prevalent conditions were hypertension (53.7%), diabetes (24.9%), and arthritis (25.5%). The most common combinations were hypertension and diabetes (19.1%), followed by hypertension and arthritis (15.3%), and hypertension and heart problems (9.0%). The prevalence of various chronic conditions is indicated in Fig. 1. The prevalence of multimorbidity increased with age and was higher in females, those with minimal education, those who were retired or homemakers, those with high SES, and among those of Indian ethnicity compared to Chinese and Malays (Table 2).

Temporal changes in chronic conditions and multimorbidity

Around 22.5% of the population had no chronic conditions, 29.1% had a single chronic condition, and 48.4% had multimorbidity (2 or more conditions). In 2023, there was a slight decrease in the number of chronic conditions. Those with no chronic conditions increased from 19.3% in 2012 to 22.5% in 2023. The proportion of those with one condition remained relatively stable (29.3% in 2012 vs. 29.1 in 2023) while those with 2 or more conditions decreased from 51.5% to 48.4% from 2012 to 2023. There were no significant age-related changes in chronic conditions from 2012 to 2023 (Table 3). The multinomial logistic regression analyses indicated no significant temporal effects between 2012 and 2023 (Table 4). The R square for this model was 0.07. Overall, there were no statistically significant differences in chronic conditions or multimorbidity between 2012 [13] and 2023 (Table 3).

Factors associated with chronic conditions and multimorbidity

Age, ethnicity, education, disability, and requiring help in daily life were associated with multimorbidity. Those who were 75–84 years of age had about 2.90 times higher odds (OR: 2.90, 95% CI: 1.55–5.42, p = 0.001) of having multimorbidity as compared to those who were 60–74 years of age. Those of Malay and Indian ethnicity had 1.62 times (OR: 1.62, 95% CI: 1.10–2.38, p = 0.015) and 3.15 times (OR: 3.15, 95% CI: 2.02–4.89, p < 0.001) higher odds, respectively, of having multimorbidity compared to those of Chinese ethnicity. Those who had completed tertiary education had lower odds (OR: 0.28, 95% CI: 0.08–0.98, p = 0.046) of having multimorbidity. Those with disability had 1.98 times higher odds (OR: 1.98, 95% CI: 1.03–3.84, p = 0.042), while those who required help with one or more of their ADL had 6.33 times higher odds (OR: 6.33, 95% CI: 1.44–27.74 p = 0.015) of having multimorbidity. While age followed a similar pattern as multimorbidity for single chronic conditions, those of Indian ethnicity and those who were unemployed (across all ethnic groups) showed higher odds of having a single chronic condition (Table 5; univariate analysis in supplementary table S1). Those who rated that they were of good health had lower odds of having multimorbidity (OR: 0.46, 95% CI: 0.29–0.72, p = 0.001) The R2 found for the model was 0.18.

Discussion

Prevalence of chronic conditions

As noted in the current study, dyadic patterns with combinations of hypertension and diabetes, hypertension and arthritis, followed by hypertension and heart diseases were also identified by Zhang and colleagues31 in their systematic review of studies from China and India, further corroborating the validity of our results. The review also noted that the most frequent conditions in the 59 studies were hypertension, diabetes, cerebro and cardiovascular disease and arthropathies, similar to what we observed in the study. A similar population-wide study in Malaysia noted comparable prevalence for hypertension (51.1%) and diabetes (27.7%,32), further corroborating our findings. Moreover, these three most prevalent conditions- mirror those frequently encountered in primary care settings33. Similar results were noted among community dwelling adults in Singapore34 as well.

Prevalence of multimorbidity and temporal changes

While we observed a similar prevalence of multimorbidity between both waves of the WiSE study, the prevalence of multimorbidity varies widely across other studies elsewhere. A systematic review of 70 community-level studies noted a pooled prevalence of 33.1% for multimorbidity35, with a significant difference observed between high-income countries and low-middle-income nations (37.9% vs. 29.7%). Another systematic review of 45 studies representing high-income countries revealed a much higher prevalence of 66.1% multimorbidity among older adults36. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 5.4 million people from 54 countries showed a global prevalence of 37.2%, noting regional, age, gender, and temporal differences in prevalence37. Another cross-sectional study conducted in Malaysia among community-dwelling older adults found a prevalence of 40.6%32. In the current study, we observed a prevalence of 47.1% for multimorbidity34. Ge et al., reported a prevalence of 35% for multimorbidity among community dwelling adults in Singapore34. Low and colleagues38, using the data from the eastern regional health systems in Singapore, noted a prevalence of 26.2%. This discrepancy among studies can also be explained based on a recent systematic review of 193 studies39, reporting a pooled prevalence of 42.4% for multimorbidity. The authors emphasized the high heterogeneity in prevalence across the studies, ranging from 2.7% to 95.6%, with older adults exhibiting a higher prevalence than younger adults (28% in those < 59 years vs. 47.6% in those 59–73 years and 67% in those ≥ 74 years of age). This observed heterogeneity was attributed to methodological differences (e.g. sampling, setting) and population characteristics such as participant age and the number of conditions included in the questionnaire. Additionally, it is important to note that this relationship between age and multimorbidity likely reflects the cumulative impact of various life course factors such as socioeconomic conditions, healthcare access, poor nutrition, occupational health hazards, and stress rather than ageing per se40,41,42.

The reported prevalence of multimorbidity in high-income countries was 44.3%, corroborating the findings of the current study. Similar observations were also noted for high income countries by other studies31 who also highlighted heterogeneity in reporting between countries contributed by underreporting of chronic conditions by participants from low and middle-income countries (LMIC). The authors also emphasized that higher mortality among those with multimorbidity in LMIC could also contribute to this discrepancy. The current study noted a lower, albeit statistically insignificant, prevalence of multimorbidity compared to the WiSE 2012 study13, which employed the same methodology (51.5% vs. 48.4%). The slight decrease in the prevalence of multimorbidity could be attributed to nationwide health campaigns aimed at raising awareness, promoting healthy lifestyle habits, and encouraging smoking cessation43.

Factors associated with chronic conditions and multimorbidity

The present study also identified that individuals of Indian and Malay ethnicities had higher odds of chronic conditions and multimorbidity compared to those of Chinese ethnicity, consistent with findings from the WiSE 2012 study13. Similar associations were noted in studies conducted in Malaysia32. Ethnic disparities in the prevalence and types of chronic conditions have been documented in prior research which have been attributed to variances in underlying causal mechanisms and genetic predispositions for these diseases44,45. Similar to the WiSE 2012 study, we found a negative correlation between multimorbidity and higher education levels. A systematic review of 18 studies revealed variations in the association between education and multimorbidity across different studies46. The review identified three dimensions: a positive association, a negative association, and no association in the included studies. These discrepancies were attributed to differences in the definition of multimorbidity, educational levels, and adjustment factors (independent variables), leading to varying associations even within the same dataset46. The authors emphasized that higher education enhances individuals’ awareness of healthy living, improves health literacy, and reduces the likelihood of experiencing multimorbidity.

The relationship between multimorbidity and health outcomes (disability and self-rated health)

Multimorbidity showed significant associations with both disability and self- rated health status, reflecting complex pathways that impact overall wellbeing. Research consistently shows that multimorbidity increases disability and the need for assistance with activities of daily living47,48 ,32), with different combinations of chronic diseases creating varying pathways to functional impairment49. Two primary mechanisms explain this relationship: chronic diseases trigger systemic inflammation that can impair physical function, particularly with cardiovascular conditions, and multimorbidity often leads to sarcopenia, both of which directly contribute to functional limitations49,50. Longitudinal studies have confirmed that disability serves as a crucial pathway through which multimorbidity ultimately affects mortality outcomes6.

Concurrently, multimorbidity shows a negative correlation with self- rated health status, a relationship observed across diverse geographical populations51,52. This association reflects the complex interplay of physiological disease interactions, medication effects, and disease self-management challenges53. Specific combinations of chronic conditions can exacerbate morbidity and caregiving responsibilities, adversely affecting perceived health53. The significance of self- rated health extends beyond subjective assessment, as it serves as a predictor of mortality and reflects individuals’ coping mechanisms and health-related behavior54. These findings align with established health status models suggesting that disease impacts on self-perceived health are mediated through disability and functional limitations, influenced by demographic characteristics9.

Temporal stability in multimorbidity: potential impact of National initiatives and the pandemic

Singer and colleagues55 noted an increase in multimorbidity from 41.6% to 46.2% in the 2010–2011 period and thereafter a stabilisation until 2014–2015 in England. A subsequent study by Head et al.,56, however, showed a steady increase from 30.8% in 2004 to 52.8% in 2019. This increase was proposed to be due to declining fatalities, earlier onset of multimorbidity, and widening socioeconomic inequalities, all compounded by the potential impact of austerity policies over the past decade. Similar results were noted from Canada57 and China58. In contrast to the increasing trends observed in these countries, the stability in the prevalence of multimorbidity among older adults in Singapore (48.4% vs. 51.5% in 2012) could be attributed to several national initiatives implemented over the past decade. These include the pioneer generation package aimed to improve the accessibility to subsidized care59, community networks for seniors, a programme jointly delivered by community partners, policy makers and healthcare systems to promote active ageing through support rendered through various domains such as preventive health, strengthening social connections, volunteerism, housing conditions, etc.60 and enhanced chronic disease management programmes that ensure subsidized care for 23 chronic conditions61. The Action Plan for Successful Ageing, launched in 201660, also strengthened preventive health services and community support systems.

However, the lack of significant decrease in the prevalence of multimorbidity despite these efforts warrants attention. A similar trend was noted by Chowdhury and colleagues37. This could be due to several factors: the increasing life expectancy leading to longer exposure to risk factors62, changes in major risk factor such as smoking, alcohol consumption, dietary habits, and physical activity levels; or changes in diagnostic criteria and improved disease detection methods63.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The study utilized respondent-level stratified random sampling, drawing from the national population database as the sampling frame, thereby enhancing the generalizability of the data to a broader Asian population, which constitutes a notable strength of the research. Additionally, conducting the survey in various languages and dialects ensured the inclusivity of minority samples. However, the cross-sectional design of the study precludes the establishment of causal relationships. Furthermore, the inclusion of conditions categorized under the chronic disease checklist, as reported in several systematic reviews, may introduce variability in comparisons across different nations. Despite this, we maintained consistency with the list and classification used in previous studies, enabling longitudinal comparisons and facilitating the tracking of changing prevalence over time. The COVID-19 pandemic might have influenced our findings in several ways. Safe distancing measures and fear of virus exposure likely reduced healthcare visits for routine check-ups and chronic disease management. This could have led to under-detection of new conditions or exacerbation of existing ones. Furthermore, the pandemic’s impact on physical activity levels, social isolation, and mental health might have affected overall health status. These factors should be considered when interpreting our results. Also, another key limitation is that the sample size was calculated based on the prevalence of depression and dementia in the original WiSE study, rather than for multimorbidity. This might affect the statistical power to detect associations between certain variables and multimorbidity patterns. Additionally, the 10/66 assessments were optimized for the diagnosis of mental health conditions rather than physical health conditions which is a limitation.

Conclusion

The study findings indicate that the prevalence of multimorbidity remained consistent between 2012 and 2023, despite demographic shifts, is a positive observation. Despite the implementation of various healthcare plans and community-level initiatives over the years to promote health behavior, early detection, and management of chronic diseases, there was no significant reduction in multimorbidity prevalence over the decade. Nonetheless, given the substantial impact of ageing on both the health and economic status of the nation, this underscores the need for continued preventive healthcare efforts. Furthermore, the study identified specific sociodemographic groups with a higher likelihood of experiencing multimorbidity, highlighting the necessity for a targeted reevaluation of ongoing healthcare and community level programs for these groups. If necessary, modifications should be made accordingly to suit the target population. The current healthcare model predominantly focuses on individual diseases and should be expanded to encompass multimorbidity, considering its persistent prevalence over the decade and its association with self-perceived health status. Adopting such a holistic approach has the potential to alleviate healthcare burdens on patients and facilitate patient-centric service delivery. Given the ageing population, future research should focus on community level integrative care models to better support those with multimorbidity in Singapore. Longitudinal studies could shed light on the causes and progression of chronic diseases among older adults.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

World Health Organization. Ageing and health. (2022). Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health

Palladino, R., Lee, T., Ashworth, J., Triassi, M., Millett, C. & M., & Associations between multimorbidity, healthcare utilisation and health status: evidence from 16 European countries. Age Ageing. 45, 431–435. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afw044 (2016).

Atella, V. et al. Trends in age-related disease burden and healthcare utilization. Aging Cell. 18, e12861. https://doi.org/10.1111/acel.12861 (2018).

Kriegsman, D. M., Deeg, D. J. & Stalman, W. A. Comorbidity of somatic chronic diseases and decline in physical functioning: the longitudinal aging study Amsterdam. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 57, 55–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00258-0 (2004).

Patel, K. V., Peek, M. K., Wong, R. & Markides, K. S. Comorbidity and disability in elderly Mexican and Mexican American adults: findings from Mexico and the Southwestern united States. J. Aging Health. 18, 315–329. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264305285653 (2006).

St John, P. D., Tyas, S. L., Menec, V. & Tate, R. Multimorbidity, disability, and mortality in community-dwelling older adults. Can. Fam Physician. 60, e272–e280 (2014).

Nascimento, C. M., Oliveira, C., Firmo, J. O. A., Lima-Costa, M. F. & Peixoto, S. V. Prognostic value of disability on mortality: 15-year follow-up of the Bambuí cohort study of aging. Arch. Geronto Geriatr. 74, 112–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2017.10.011 (2018).

Palladino, R., Nardone, A., Millett, C. & Triassi, M. The impact of Multimorbidity on health outcomes in older adults between 2006 and 2015 in Europe. Eur. J. Public. Health. 28 https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cky213.400 (2018). (suppl_4), cky213.400.

Johnson, R. J. & Wolinsky, F. D. Gender, race, and health: the structure of health status among older adults. Gerontol 34, 24–35. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/34.1.24 (1994).

Department of Statistics Singapore. Population and population structure. Archived from the original on 16. November (2023). https://www.singstat.gov.sg/publications/reference/ebook/population/population (2023).

Statista Research Department. Residents aged 65 years and older as share of the resident population in Singapore from 1970 to 2022 (2023b). https://www.statista.com/statistics/1112943/singapore-elderly-share-of-resident-population/

United Nations. World population ageing. (2015). http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WPA2015_Report.pdf.

Picco, L. et al. Economic burden of Multimorbidity among older adults: impact on healthcare and societal costs. BMC Health Serv. Res. 16, 173. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1421-7 (2016).

Asharani, P. V. et al. Health literacy and diabetes knowledge: A nationwide survey in a Multi-Ethnic population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18, 9316. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179316 (2021).

Wong, H. Z., Lim, W. Y., Ma, S. S., Chua, L. A. & Heng, D. M. Health screening behaviour among Singaporeans. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 44, 326–334 (2015).

Ministry of Health, War on Diabetes. (2020). https://www.moh.gov.sg/others/resources-and-statistics/war-on-diabetes

Ministry of Health. What is Healthier SG? (2024). https://www.healthiersg.gov.sg/about/what-is-healthier-sg/.

Ministry of Health. Age Well SG to support our seniors to age actively and independently in the community. (2023). https://www.moh.gov.sg/newsroom/age-well-sg-to-support-our-seniors-to-age-actively-and-independently-in-the-community.

Subramaniam, M. et al. Prevalence of depression among older Adults-Results from the Well-being of the Singapore elderly study. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 45, 123–133 (2016).

AshaRani, P. V. et al. Tracking the prevalence of depression among older adults in singapore: results from the second wave of the Well-Being of Singapore elderly study. Depress. Anxiety. 9071391. https://doi.org/10.1155/da/907139 (2025).

Subramaniam, M. et al. Prevalence of dementia in singapore: changes across a decade. Alzheimers Dement. 21, e14485. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.14485 (2025).

Stewart, R., Guerchet, M. & Prince, M. Development of a brief assessment and algorithm for ascertaining dementia in low-income and middle-income countries: the 10/66 short dementia diagnostic schedule. BMJ open. 6, e010712. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010712 (2016).

Prince, M. J. et al. 10/66 dementia research group. The 10/66 dementia research group’s fully operationalized DSM-IV dementia computerized diagnostic algorithm, compared with the 10/66 dementia algorithm and a clinician diagnosis: A population validation study. BMC Public. Health. 8, 219 (2008).

Prina, A. M., Mayston, R., Wu, Y. T. & Prince, M. A review of the 10/66 dementia research group. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 54, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1626-7 (2019).

Harber-Aschan, L. et al. Beyond the social gradient: the role of lifelong socioeconomic status in older adults’ health trajectories. Aging (Albany NY). 12, 24693–24708. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.202342 (2020).

Ministry of Manpower. Retirement. (2022). https://www.mom.gov.sg/employment-practices/retirement.

Dunn, J. R., Hayes, M. V., Hulchanski, J. D., Hwang, S. W. & Potvin, L. Housing as a socio-economic determinant of health: findings of a National needs, gaps and opportunities assessment. Can. J. Public. Health. 97, S11–S17 (2006).

Singapore Housing Development Board. Public rental scheme [updated 1st October 2015]. (2015). http://www.hdb.gov.sg/cs/infoweb/residential/renting-a-flat/renting-from-hdb/public-rental-scheme.

Chan, C. Q. H., Lee, K. H. & Low, L. L. A systematic review of health status, health seeking behaviour and healthcare utilisation of low socioeconomic status populations in urban Singapore. Int. J. Equity Health. 17, 39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-018-0751-y (2018).

Rehm, J. et al. On the development and psychometric testing of the WHO screening instrument to assess disablement in the general population. Int J. Methods Psychiatr Res 8 (1999).

Zhang, X. et al. Community prevalence and dyad disease pattern of Multimorbidity in China and india: a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health. 7, e008880 (2022).

Ghazali, S. S. et al. Prevalence and factors associated with Multimorbidity among older adults in malaysia: a population-based cross-sectional study. BMJ open. 11, e052126 (2021).

Lee, E. S. et al. The prevalence of Multimorbidity in primary care: a comparison of two definitions of Multimorbidity with two different lists of chronic conditions in Singapore. BMC public. Health. 21, 1409. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11464-7 (2021).

Ge, L., Yap, C. W. & Heng, B. H. Sex differences in associations between Multimorbidity and physical function domains among community-dwelling adults in Singapore. PloS One. 13, e0197443. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0197443 (2018).

Nguyen, H. et al. Prevalence of Multimorbidity in community settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J. Comorb. 9, 2235042X19870934. https://doi.org/10.1177/2235042X19870934 (2019).

Ofori-Asenso, R. et al. Recent patterns of Multimorbidity among older adults in High-Income countries. Popul. Health Manag. 22, 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1089/pop.2018.0069 (2019).

Chowdhury, S. R., Das, D. C., Sunna, T. C., Beyene, J. & Hossain, A. Global and regional prevalence of Multimorbidity in the adult population in community settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EClin. Med., 57 (2023).

Low, L. L. et al. Epidemiologic characteristics of Multimorbidity and sociodemographic factors associated with Multimorbidity in a rapidly aging Asian country. JAMA Netw. Open. 2 (11), e1915245. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.15245 (2019).

Ho, I. S. et al. Variation in the estimated prevalence of multimorbidity: systematic review and meta-analysis of 193 international studies. BMJ open. 12 (4), e057017. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-057017 (2022).

Navarro, C. et al. Intrinsic and environmental basis of aging: A narrative review. Heliyon 9, e18239 (2023).

Gianfredi, V. et al. Aging, longevity, and healthy aging: the public health approach. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 37, 125 (2025).

da Costa, J. P. et al. A synopsis on aging-Theories, mechanisms and future prospects. Ageing Res. Rev. 29, 90–112 (2016).

Health promotion board. Health Programmes, (2024). https://www.healthhub.sg/programmes.

Quiñones, A. R. et al. Racial/ethnic differences in Multimorbidity development and chronic disease accumulation for middle-aged adults. PloS One. 14, e0218462. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0218462 (2019).

Kington, R. S. & Smith, J. P. Socioeconomic status and Racial and ethnic differences in functional status associated with chronic diseases. Am. J. Public. Health. 87, 805–810. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.87.5.805 (1997).

Feng, X., Kelly, M. & Sarma, H. The association between educational level and Multimorbidity among adults in Southeast asia: A systematic review. PloS One. 16, e0261584. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261584 (2021).

Williams, J. S. & Egede, L. E. The association between Multimorbidity and quality of Life, health status and functional disability. Am. J. Med. Sci. 352 (1), 45–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjms.2016.03.004 (2016).

Su, P. et al. The association of Multimorbidity and disability in a community-based sample of elderly aged 80 or older in Shanghai, China. BMC Geriatr. 16 (178). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-016-0352-9 (2016).

Marengoni, A. et al. Patterns of Multimorbidity in a population-based cohort of older people: sociodemographic, lifestyle, and functional differences. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 75, 798–805. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glz137 (2020).

Kelley, G. A. et al. Is sarcopenia associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality and functional disability? Exp. Gerontol. 1, 100–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2017.01.017 (2017).

Honda, Y., Nakamura, M., Aoki, T. & Ojima, T. Multimorbidity patterns and the relation to self-rated health among older Japanese people: a nationwide cross-sectional study. BMJ open. 12, e063729. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-063729 (2022).

Perruccio, A. V., Katz, J. N. & Losina, E. Health burden in chronic disease: Multimorbidity is associated with self-rated health more than medical comorbidity alone. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 65, 100–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.04.013 (2012).

Mavaddat, N., Valderas, J. M., van der Linde, R., Khaw, K. T. & Kinmonth, A. L. Association of self-rated health with multimorbidity, chronic disease and psychosocial factors in a large middle-aged and older cohort from general practice: a cross-sectional study. BMC Fam Pract. 15, 185. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-014-0185-6 (2014).

Lorem, G., Cook, S., Leon, D. A., Emaus, N. & Schirmer, H. Self-reported health as a predictor of mortality: A cohort study of its relation to other health measurements and observation time. Sci. Rep. 10, 4886. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-61603-0 (2020).

Singer, L. et al. Trends in Multimorbidity, complex Multimorbidity and multiple functional limitations in the ageing population of England, 2002–2015. J. Comorb. 9, 2235042X19872030 (2019).

Head, A. et al. Inequalities in incident and prevalent multimorbidity in England, 2004–19: a population-based, descriptive study. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2, e489–e497 (2021).

Ferris, J. K. et al. Temporal multimorbidity patterns and cluster identification: a longitudinal analysis of administrative data. BMC med. 23, 370 (2025).

Yu H, et al. Temporal change in multimorbidity prevalence, clustering patterns, and the association with mortality: findings from the China KadoorieBiobank study in Jiangsu Province. Front Public Health. 12, 1389635 (2024). https:doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1389635.

Ministry of Health. Pioneer Generation Package. (2025). https://www.moh.gov.sg/managing-expenses/schemes-and-subsidies/pioneer-generation-package.

Ministry of Health Singapore. Action Plan for Successful Ageing. (2016). https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/1525Action_Plan_for_Successful_Aging.pdf

Ministry of Health. Chronic Disease Management Programme (CDMP). (2021). https://www.moh.gov.sg/managing-expenses/schemes-and-subsidies/pioneer-generation-package.

Department of Statistics Singapore. Death and life expectancy. (2025). https://www.singstat.gov.sg/find-data/search-by-theme/population/death-and-life-expectancy/latest-data.

Souza, D. L. et al. Trends of multimorbidity in 15 European countries: a population-based study in community-dwelling adults aged 50 and over. BMC Public. Health. 21 (1), 76. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-10084-x (2021).

Acknowledgements

We thank Zhang YunJue, Prof. Martin Prince and Dr. Paul McCrone for the support provided during the survey period. We disclose support for the research of this work from the Ministry of Health Singapore.

Funding

The study was funded by the Ministry of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AR, JAV, RM, LLN, SAC, WLC, and MS conceptualized the study. AR, JAV, RM, LLN, SAC, EA, WLC, SM, BYC and MS and contributed to the methodology. AR, KR, FD, PW, SS, VS, AJ, FY, HM, SAC, and MS contributed to the data collection. EA and BT conducted the analysis. MS, JAV and CSA were involved in the funding acquisition. AR conducted the project administration. MS, JAV and CSA provided the resources. AR and MS conducted the supervision. AR, BT and FD were involved in the validation. AR wrote the original draft which was modified by the rest of the co-authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare the following competing interests: The co-authors Chow Wai Ling and Stefan Ma are salaried staffs of the Ministry of Health, however, from a different department than the funding entity (Mental Health Office, Ministry of Health). The other authors have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

AshaRani, P.V., Tan, B., Roystonn, K. et al. Prevalence, associated factors and temporal trends in multimorbidity in older adults in Singapore. Sci Rep 16, 674 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30311-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30311-y