Abstract

Biofilms in historic buildings represent stable microbial ecosystems shaped by long-term environmental filtering. We investigated bacterial and fungal communities forming biofilms on walls and ceilings in a 19th-century cheese ripening cellar in Poland, characterized by low temperature, high humidity, and minimal light - conditions resembling natural subterranean habitats. Using high-throughput 16 S rRNA and ITS sequencing, we revealed distinct taxonomic and predicted functional profiles associated with surface type (wall vs. ceiling) and material (brick vs. stone). The wall biofilms exhibited greater taxonomic and functional diversity, with enrichment in heterotrophic, fermentative, and polymer-degrading taxa and pathways, whereas ceiling biofilms showed predicted enrichment in aerobic, stress-tolerant, and potentially methanogenic lineages. The co-occurrence network analysis revealed more complex and tightly connected associations in wall biofilms, dominated by Actinobacteriota (21–97%) and Ascomycota (60–97%), suggesting stable ecological organization despite the limited sample size. Environmental factors, such as pH, redox potential, and electrolytical conductivity, explained a substantial proportion of the variance in the microbial diversity and predicted functional traits. Overall, this study highlights traditional ripening cellars as semi-natural built ecosystems that sustain specialized, spatially structured microbiomes. The results provide new insights into microbial adaptation, functional potential, and ecological resilience in heritage food environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Microorganisms are capable of colonizing a wide range of environments including natural and anthropogenic surfaces1,2,3. One of the most effective survival strategies developed by microbial communities is the formation of a biofilm - a structured surface-attached mode of life that enables protection. cooperation and long-term survival in changing environmental conditions4,5,6.

Biofilms are formed not only in natural habitats, but also in built environments, where they contribute to both ecological processes and material degradation7,8. Their presence on stone, brick, wood and plaster surfaces can affect the chemical composition and structure of buildings and the quality and safety of products in food-related environments9,10,11.

Traditional ripening rooms represent ecologically stable built environments where the architecture, material composition, and microclimate jointly shape microbial colonization. Architectural diversity, such as the presence of vaulted ceilings, thick stone foundations, and brick walls, creates a mosaic of surfaces that differ in roughness, porosity, and nutrient-retaining capacity12,13. Materials like limestone and brick, in particular, are highly susceptible to colonization due to their ability to retain moisture and organic residues, which promotes the establishment of biofilms8. Once formed, these biofilms influence not only the condition of wall and ceiling surfaces but also the microbial balance of the entire ripening space, contributing to the composition of the airborne microbiome and potentially affecting cheese maturation. The combination of heterogeneous substrates and a consistent microclimate of high humidity, low temperature, and limited light makes such cellars robust model systems for exploring microbial succession, ecological filtering, and functional specialization in built environments14,15,16.

Although biofilms in medical and industrial settings have been extensively studied, the surface-associated microbiota in traditional cheese cellars remains under-researched. In particular, little is known about the effects of surface material (stone vs. brick) and spatial location (walls vs. ceilings) on biofilm composition and function. Available literature data reported that composition of biofilms on walls is usually composed of bacteria (Pseudomonas spp., Bacillus spp., Staphylococcus spp., and Actinobacteria spp.), and fungi (Aspergillus spp., Penicillium spp., Cladosporium spp., Stachybotrys spp.)8,17. Additionally, the genera Paenisporosarcina and Amycolatopsis were identified e.g. on the walls at Wawel Royal Castle in Krakow, Poland8.

These findings indicate that the substrate type and architectural context may act as selective filters for microbial colonization, a hypothesis directly tested in the present study.

We hypothesized that both the bacterial microbiome and mycobiome of the biofilm vary depending on the surface orientation (walls vs. ceilings) and the substrate type (stone vs. brick) and that ecological interactions within these biofilms reflect environmental filtration and microhabitat-specific selection.

Here, we characterized bacterial and fungal communities forming mature architectural biofilms in a historic cheese ripening facility and investigated their predicted functional roles and ecological network structures.

Materials and methods

Study area

The research was conducted in a historic cheese ripening room, located on the grounds of the Ślesin Farm (northwestern Poland; 53°09′53″N, 17°42′11″E) (Supplementary Material 4, Fig. S1). The ripening room (area: 228 sq m, max height: 2.5 m, min height [under spans] 1.8 m) is located in an over 100-year-old cellar (built in 1890), which was once part of the farm’s barn complex. The foundations and lower parts of the walls were built of fieldstone, while the upper structure of the walls and vault is made of red brick. The ceiling consists of cradle vaults supported by brick pillars.

The average temperature in the cellar is 10 °C ± 2 °C, and the relative humidity remains stable at ~ 85%, which creates optimal microclimatic conditions for traditional cheese maturation. The cheeses are matured on birch wood shelves and are regularly maintained by cheesemakers. The structural and environmental characteristics of the cellar make it a suitable semi-natural environment for long-term microbial colonization and biofilm development.

Biofilms sampling

Biofilm samples (labeled as PD) were collected in the summer of 2021 from a long-ripened cheese cellar. The sampling locations (Supplementary Material 4, Fig. S2) were selected based on the macroscopic evidence of biological colonization, surface morphology, and lithological type of the walls and ceilings (Supplementary Material 4, Fig. S1), particularly in the vicinity of shelves where cheeses were aged. For each surface type (stone wall, brick wall, ceiling), three independent biofilm patches were scraped at a distance of ~ 50–80 cm from each other and ~ 1.5–2.5 m above the floor (samples from the walls and ceiling, respectively), yielding biological triplicates for each location. The samples were obtained using sterile stainless steel tools and transferred into sterile tubes. They were stored and transported at 4 °C to the laboratory, where DNA extraction was performed immediately. A short description (location and material) of the collected biofilm samples is provided in Table 1.

Physicochemical analysis of biofilm samples

A water suspension was prepared by mixing an 8.75 g sample with 25 ml of deionized water18. The pH, electrolytical conductivity (EC) and redox potential (Eh) were measured using Hach HQ4d, HQ11d multimeters and pHC301, CDC40103, and MTC101 electrodes, respectively (Hach Lange, USA).

The same suspensions were shaken for 1 h at 125 rpm on an orbital shaker SM-30 (Edmund Bühler GmbH, Germany) to obtain a water-extractable form of nitrogen and phosphorus. The contents of N-NO3, N-NO2, N-NH4 and P-PO4 in the extracts were determined colorimetrically using an AA3 AutoAnalyzer (Seal Analytical, Germany).

Carbon forms (Total C, Total Inorganic C, and Total Organic C) were measured in soil samples using Shimadzu TOC-VCSH with the SSM5000A module (Japan).

The total contents of Cu, Fe, Mn, Mg, K, Ca, and Na were measured on a flame atomic absorption spectrometer (Hitachi ZA3300, Japan) after digestion in the mixture of 4 ml HF, 4 ml HCl, and 1 ml HNO3 using an Anton Paar Multiwave 5000 microwave digestion system (Anton Paar GmbH, Austria). Contents of nutrients and elements were expressed in mg per kg while carbon forms in percent. Each of these factors was measured in three replicates.

DNA extraction and sequencing

The triplicate biofilm samples from each surface type (microhabitat) were homogenized and combined to obtain a representative composite sample for each location (PD_B1–PD_B4). DNA extraction from the collected biofilms was carried out using a DNeasy®PowerLyzer® PowerSoil® Kit (QIAGEN). To isolate DNA, 0.30 g of the research material was weighed into a PowerBead Tube and processed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. DNA was extracted in three independent technical replicates for each location. Pooling of the resulting DNA extracts was performed to reduce stochastic variation between replicates and to obtain a representative DNA sample for each environment.

Each pooled DNA sample was subsequently sequenced three times as technical replicates. Metagenomic DNA analysis of bacterial and fungal populations was performed within the V3-V4 hypervariable region of the 16 S rRNA gene and the ITS region. High-throughput next-generation sequencing (NGS) was carried out on the Illumina MiSeq platform using paired-end (PE) technology, 2 × 300 bp reads with the MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 (Illumina, USA). Specific primer pairs 341f (CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG) and 785r (GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC)19, were used for bacterial 16 S rRNA amplification, while ITS1FI2 (GAACCWGCGGARGGATCA) and 5.8 S (CGCTGCGTT CTTCATCG)20 were used for fungal ITS amplification and library preparation. PCR reactions were performed using Q5 Hot Start High-Fidelity 2X Master Mix (New England Biolabs, USA). Sequencing and library preparation were performed by an external service provider (Genomed S.A., Warsaw, Poland).

Bioinformatic and statistical analysis

Bioinformatic processing of sequencing data was conducted using QIIME 2 (version 2024.10)21 employing the DADA2 plugin for high-resolution amplicon sequence variant (ASV) inference22. Taxonomic assignment of bacterial sequences was performed using the SILVA 138 reference database23. For fungal community analysis, taxonomic classification was performed using the UNITE database, version 10, dynamic release (classifier-unite-ver10_dynamic-04.04.2024-Q2-2024.5.qza). This classifier is specific for fungal ITS sequences and does not include all eukaryotes. The dynamic release was chosen, as it incorporates frequent updates and refined curation of fungal taxa24,25. Taxonomy was assigned to ASVs using the q2-feature‐classifier classify‐sklearn naïve Bayes taxonomy classifier26.

Adapter sequences were removed from raw reads using Trim Galore27 which internally employs Cutadapt27 and FastQC28 and sequence trimming parameters were determined based on quality score profiles. Specifically, forward and reverse reads targeting the 16 S rRNA gene were truncated to 260 bp and 180 bp, respectively. The ITSxpress plugin28 was used for trimming ITS regions to remove conserved flanking sequences. Default filtering parameters were applied in DADA2 for both bacterial and fungal datasets.

Alpha and beta diversity metrics were initially calculated in QIIME 2, and further diversity analyses were conducted in R (version 4.4.2)29,30,31,32 using the BiodiversityR package33. Alpha-diversity was evaluated using the Shannon, Simpson and Pielou Evenness indices. Because Shannon values are non-linear and can be difficult to interpret directly, we converted them into effective numbers of species (Hill numbers of order q = 1) calculated as exp(H′), following the recommendations proposed by Jost (2006) and Lefcheck (2012)34,35. This transformation expresses diversity on a linear scale, where values can be interpreted as the equivalent number of equally abundant taxa, facilitating direct comparisons among samples. To minimize the influence of sequencing errors and spurious rare taxa, we additionally filtered features occurring at < 0.1% relative abundance within each sample. Shannon diversity metrics were calculated both before and after filtering to assess the stability of the results. Beta-diversity patterns were evaluated using both phylogenetic and non-phylogenetic distance metrics. For the 16 S rRNA gene dataset, beta diversity was assessed using three complementary approaches: Aitchison (CLR-Euclidean) distances, to account for the compositional nature of the data; weighted UniFrac, incorporating phylogenetic relationships and abundance; and unweighted UniFrac, reflecting presence/absence-based phylogenetic similarity. Aitchison distances were calculated from CLR-transformed data after count-zero multiplicative (CZM) replacement (zCompositions package), using Euclidean distances and PCoA ordination (ape). Weighted and unweighted UniFrac distances were computed on the rarefied ASV Tables (30,000 reads per sample) using a rooted phylogenetic tree generated in QIIME2. The resulting distance matrices were ordinated by PCoA, and plots were generated in R (ggplot2), with axis labels indicating the proportion of variance explained. For the ITS dataset, UniFrac metrics were not applicable due to the absence of a universally accepted fungal phylogeny. Therefore, Aitchison distances (CLR–Euclidean) were used exclusively to describe compositional dissimilarities, following the same pipeline as for 16 S. Group differences were evaluated using PERMANOVA (adonis2, vegan, 9,999 permutations), and the homogeneity of multivariate dispersion (PERMDISP) was assessed with the same number of permutations34,36,37. Stress values were examined to assess the goodness of fit, and consistent clustering patterns with PCoA confirmed the robustness of the beta-diversity structure. To control for multiple testing, p-values from all PERMANOVA tests were adjusted using the Benjamini–Hochberg (FDR) correction38.

Functional predictions for bacterial communities were carried out using the FAPROTAX database (version 1.2.10)39, within a Python 3 environment. Fungal functional guilds were assigned using the FunGuild database (version 1.1)40, also executed in Python 3.

To evaluate differences in taxonomic abundances between categorical groups (e.g., wall vs. ceiling; brick vs. stone), microbiological data were CLR-transformed to account for their compositional nature41. Group comparisons were performed using Wilcoxon rank-sum test and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Multiple testing correction was applied using the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) procedure, and taxa with adjusted p-values (p_adj) < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

To explore the relationships between the community composition and environmental variables, we performed redundancy analysis (RDA). For this analysis, the ASV count table was first transposed (samples × taxa) and subjected to a Hellinger transformation42 using the decostand function in the vegan package. The Hellinger transformation converts raw counts into square-rooted relative abundances, reducing the impact of differences in sequencing depth and making Euclidean-based ordination methods such as RDA more appropriate. The significance of the model, individual environmental predictors and canonical axes were evaluated using permutation-based ANOVA (anova.cca) with 999 permutations.

All statistical analyses and graphical visualizations were conducted in R (version 4.4.2)31, using the following R packages: ggplot243, ggpubr44, pheatmap45, vegan46, MASS47, phyloseq48, igraph49, and Hmisc50, compositions51, rstatix52.

Results

Physicochemical characteristics of biofilm samples

The basic physicochemical parameters describing the biofilm samples are summarized in Table 1.

The physicochemical characteristics of collected samples were closely connected with the substrate material – brick and stone and were significantly different for each sample (p < 0.01; Table 1). They had alkaline reaction (> 8 with the exception of sample PD_B3–7.81), a substantial fraction of IC in relation to TC (81–90%), and high contents of alkaline and alkaline earth metals, among which potassium and calcium were the most abundant (up to 24.8 g kg− 1 and 22 g kg− 1, respectively). What is more, iron (Fe) was the third abundant element reaching up to 13 g kg− 1. The values of Eh indicated quite reducing conditions that correspond with Fe contents. There were also high N-NO3 contents in the samples ranging from 371.63 ± 2.01 (PD_B4) to 64.236 ± 192 mg kg− 1. It is worth noting that sample PD_B3 contained high amounts of salts (EC = 122.6 µS cm− 1), which was reflected by the highest levels of N-NH4, Mg, and K forming a distinctive niche for microorganisms.

Microbial community structure

In this study, four DNA biofilm samples, each analyzed in triplicate, were sequenced. The final datasets contained between 97,788 and 124,764 sequences per sample. Additional information about the sequences is provided in Supplementary Material 4: Table S1, Fig. SS3 and Fig. S4.

Microbial diversity

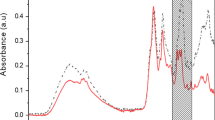

The microbial diversity in the analyzed biofilm samples was assessed using biodiversity estimates for individual samples (alpha diversity) (Fig. 1a and b) and microbial community similarity between the samples (beta diversity) (Fig. 1c and d). The Shannon and Simpson indices were used to quantify microbial diversity. Additionally, the Pielou Evenness index was employed to assess the evenness of species distribution, providing insight into the relative abundance of different taxa within the microbial community.

Based on the indicators shown in Fig. 1a and b, it can generally be observed that the microbial biodiversity of both bacteria and fungi in biofilms developing on the walls of the cheese ripening room was higher compared to those on the ceiling. All the calculated bacterial and fungal biodiversity indices were approximately 38–43% lower for the ceiling in terms of Shannon entropy (p < 0.01), 12% for the Simpson index, and 21–27% lower for Pielou evenness (p > 0.01).

Alpha (a and b) and beta (c and d) diversity. The boxplots corresponds to the bacterial (a) and fungal (b) biodiversity indices: Simpson, Shannon, and Pielou index and represents the diversity between the samples. The Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) illustrates the variability of bacteria (c) and fungi (d) between the biofilms.

The principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) analysis revealed that the microbial composition of the biofilms differed notably depending on the sampling location (wall vs. ceiling), in agreement with the taxonomic distinctions described below. In the PCoA plot for bacterial communities, the samples collected from the walls (PD_B1 and PD_B2) clustered closely together, indicating a high degree of compositional similarity between these biofilms. In contrast, the ceiling-derived samples (PD_B3 and PD_B4) were clearly separated from the wall samples and from each other, suggesting a distinct and more heterogeneous bacterial structure, with PD_B3 exhibiting the most divergent profile (Fig. 1c).

The weighted UniFrac PCoA revealed clear separation between wall and ceiling associated biofilms (Fig. 1). PERMANOVA applied to the weighted UniFrac matrix confirmed a significant effect of group (R² = 0.999, F = 2101.2, p = 0.0001), with no significant heterogeneity of dispersion (PERMDISP F(3,7) = 3.48, p = 0.074). For 16 S, using Aitchison (CLR–Euclidean) distances, PERMANOVA showed a strong effect of publicationName group (R² = 0.937, F = 34.50, p = 0.0001). However, dispersion heterogeneity was detected (PERMDISP F(3,7) = 4.64, p = 0.0275), indicating that part of the PERMANOVA signal may be influenced by differences in within-group variability. For the ITS dataset, analyzed in Aitchison space (CLR–Euclidean), PERMANOVA also indicated significant community differentiation (F = 34.47, R² = 0.937, p = 0.0002), while PERMDISP showed no difference in dispersion (F(3,7) = 0.874, p = 0.507). After Benjamini–Hochberg correction, both comparisons remained significant (weighted UniFrac p_FDR = 0.0003; Aitchison p_FDR = 0.0002). Together, these results confirm strong and consistent compositional and phylogenetic differentiation between wall and ceiling biofilms.

Taxonomic classification of the microbial community

The relative abundance of bacterial and fungal phyla colonizing the biofilms is shown in Fig. 2. The community structure differed in the sampling location, with the wall biofilms (PD_B1, PD_B2) showing greater diversity than the ceiling biofilms (PD_B3, PD_B4), particularly on stone surfaces. Actinobacteriota dominated the ceiling samples (up to 93%), whereas wall biofilms contained higher proportions of Pseudomonadota (previously Proteobacteria) (~ 39%) and Bacteroidota (22–35%). Additional phyla detected at lower abundances included Candidate Phyla Radiation (Patescibacteria), Planctomycetota, Chloroflexota (previously Chloroflexi), Bacillota (previously Firmicutes), Gemmatimonadota and Halobacterota (up to 2% on the stone walls; Fig. 2a).

Among fungi, Ascomycota predominated across all the samples (58–96%), with wall biofilms exhibiting higher diversity and additional contributions from Mortierellomycota and Rozellomycota. The ceiling biofilms contained higher proportions of Fungi Incertae sedis (13–19%), whereas the wall biofilms showed unique Rozellomycota enrichment (2.4%; Fig. 2b).

Relative abundance of top 10 bacterial (a) and fungal (b) genera (%), representing the microbial community identified in the biofilm samples. Differences in the relative abundance of dominant taxa at the genus level as a function of the sampling location (walls vs. ceiling) (c and d) and the wall construction material (brick vs. stone) (e and f).

At the genus level (Fig. 3), distinct colonization patterns were observed depending on the sampling location. The ceiling surfaces (PD_B3 and PD_B4) were enriched in Amycolatopsis (39% and 20%), Pseudonocardia (20% and 3%), and unidentified members of the Micrococcales order (8% and 15%), whereas their presence in the wall biofilms (PD_B1 and PD_B2) was markedly lower, i.e. 7% and 1.4% for Amycolatopsis, 4% and 2.5% for Pseudonocardia, and only 0.08% for Micrococcales, corresponding to a 78–99% reduction (p < 0.05). Additionally, unidentified Actinobacteria were substantially more abundant on the ceiling (17.1% and 1.53%) than on the walls (0.90% and 0.45%), indicating a strong enrichment of Actinobacterial lineages in the ceiling biofilms (p < 0.05). Other taxa, such as Rubrobacter, exhibited similar but statistically non-significant differences between the ceilings and the walls. Wall biofilms, in contrast, were dominated by Flavobacteriaceae (10% and 12%), Balneolaceae (10% and 16%), (p < 0.05) and Halomonas (6–7%), and Salinisphaera (13–16%), (p > 0.05) which occurred at much lower levels on the ceiling surfaces (0.5–2.5%), corresponding to reductions of 91–99% (Fig. 3c). The wall material (brick vs. stone) had less influence on the composition of the bacterial community. Actinomycete-related taxa, including Amycolatopsis, Pseudonocardia, and unidentified members of the Pseudonocardiaceae family and Actinobacteria class, were on average 60% more abundant on brick than on stone, but with p < 0.05. In contrast, Flavobacteriaceae family (p < 0.05) and halotolerant taxa such as Halomonas (p > 0.05) and, in particular, Salinisphaera (p > 0.05) preferred stone surfaces (Fig. 3e). Detailed data on the abundance of all taxa are presented in Supplementary Material 1.

Fungal communities exhibited opposite trends to bacteria. Wall biofilms (PD_B1 and PD_B2) were enriched in Cordycipitaceae genus Incertae sedis (20–50%), Cladosporium (0.7–4.5%), Aspergillaceae genus Incertae sedis (p < 0.05), Debaryomyces (p < 0.05), and Acremonium (7–16%), as well as unidentified species of Hypocreales (1–4%) (p > 0.05; Fig. 3d). At the same time, ceiling samples (PD_B3 and PD_B4) were dominated by Hypocreales genus Incertae sedis (30–61%) and unidentified Fungi species (13–19%) (p < 0.05). As in the case of the bacteria, the wall material affected the fungal communities: most taxa preferred brick, while Debaryomyces and unidentified Fungi were more abundant on stone (p < 0.05; Fig. 3f). Detailed data on the abundance of all taxa are presented in Supplementary Material 2.

The RDA analysis (Fig. 4a and b) evidenced that the different taxa constituting the biofilms in the cheese ripening rooms have clear preferences for environmental variables. EC and pH were the most important variables shaping the composition of the microbiome, especially of bacteria of the order Pseudonocardiales (Amycolatopsis and Pseudonocardia) and fungi of the class Dothideomycetes. Permutation-based ANOVA (999 permutations) for the bacterial community confirmed that the overall RDA model was highly significant (F = 157.9, p = 0.001). The tests of individual terms showed that Eh, pH and EC were all significant community composition predictors (p = 0.001 each). The axis-wise tests further indicated that the first three canonical axes were significant (p = 0.001), with RDA1 explaining the largest share of variance. Permutation-based ANOVA (999 permutations) of fungal ITS data confirmed that the RDA model was significant (F = 43.2, p = 0.001). All three variables Eh, pH and EC were significant predictors (p = 0.001), with Eh explaining the largest share of variance, followed by EC and pH. The axis tests indicated that the first three canonical axes were all significant (p = 0.001).

Predicting microbial function in biofilms

Functional profiling of the bacterial communities using FAPROTAX revealed distinct metabolic potentials between the wall (PD_B1, PD_B2) and ceiling (PD_B3, PD_B4) biofilms (Fig. 5). Only ecologically relevant categories consistent with the cheese-ripening cellar environment (e.g., chemoheterotrophy, fermentation, polymer degradation, denitrification, and ureolysis) were considered in the interpretation. Functions unlikely to occur under the studied conditions (e.g. photoautotrophy) were excluded as database artefacts.

Heat map showing the predicted functional activity of microorganisms assigned to different functional groups in the analysis of 16 S rRNA amplicon sequences. The color intensity represents the level of a given function in each sample: dark red - higher predicted functional activity, blue - lower activity, white - neutral activity (close to zero).

The biofilms formed on the wall surfaces were characterized by a strong enrichment of heterotrophic metabolic pathways. In particular, such functions as chemoheterotrophy, aerobic chemoheterotrophy, fermentation, nitrate reduction, xylanolysis, and chitinolysis showed consistently higher relative abundances in the PD_B1 and PD_B2 samples. These processes likely support organic matter turnover, nutrient cycling, and maintenance of stable biofilm structures under nutrient-rich yet microaerophilic conditions.

In contrast, the ceiling biofilms (PD_B3 and PD_B4) displayed elevated levels of methanogenesis, particularly hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis (CO₂ reduction with H₂) and nitrite respiration, suggesting the presence of localized anaerobic microniches within ceiling-associated biofilms. Interestingly, the levels of some functional categories, such as nitrification aerobic ammonia or nitrite oxidation were consistently low across all the samples, suggesting limited nitrifying activity in this environment (Fig. 5).

These results highlight strong functional differentiation between the ceiling and wall biofilms in the cheese ripening room, likely driven by environmental gradients such as light availability, nutrient deposition, and potentially microaerobic or anaerobic conditions.

Heat map showing the predicted functional activity of microorganisms assigned to different functional groups in the analysis of ITS region sequences. The color intensity represents the level of a given function in each sample: dark red - higher predicted functional activity, blue - lower activity, white - neutral activity (close to zero).

The functional assignment of fungal taxa based on the FunGuild analysis revealed distinct ecological strategies between the biofilms developing on the walls (PD_B1 and PD_B2) and the ceiling (PD_B3 and PD_B4) surfaces of the cheese ripening room (Fig. 6). The fungal communities associated with the wall biofilms exhibited a significantly higher functional diversity and were dominated by taxa classified into saprotrophic and multifunctional trophic modes. In particular, samples from the brick and stone walls (PD_B1 and PD_B2) exhibited an elevated relative abundance of several functional guilds. Saprotrophs, which are responsible for the degradation of organic matter, were especially prominent in PD_B1. Multifunctional fungi, characterized by combined ecological roles, such as saprotrophic and symbiotic functions, were abundant in both PD_B1 and PD_B2. Additionally, endophytes and endophyte–saprotrophs, typically associated with plant material but also capable of degrading complex organic substrates, were well represented. Other groups, including wood saprotrophs, fungal parasites, and animal parasites, were detected almost exclusively in the wall-associated biofilms (Fig. 6).

Ecological networks

Figure 7 presents the ecological networks established for the 20 most important microbial taxa: bacteria (16 S) in the upper part and fungi (ITS) in the lower part. The analysis was based on the co-occurrence of taxa in different samples, which may suggest ecological relationships, e.g. mutualism, competition, or interdependence.

The ecological network indicates the dominance of Actinobacteriota, which form a highly connected cluster, suggesting a stable and integrated ecological community. Figure 7 shows a large, strongly connected cluster of red nodes (Actinobacteriota) which may indicate an intense interdependence of this bacteria phylum. The presence of Pseudomonadota and Bacteroidota in the mixed cluster indicates the possibility of complementary interactions especially in the degradation of organic substances present in the biofilm and the exchange of metabolites. The mixed green-blue-red groups (Actinobacteriota, Pseudomonadota, Bacteroidota) may suggest more complex interactions between phyla, e.g. cooperation in the degradation of organic matter or exchange of metabolites. It should be noted that there are a few individual unrelated nodes (outliers), which may suggest that these taxa are unique to a single sample or poorly associated with the rest of the microbiota (Fig. 7). The red cluster coincides with the dominance of the genera Pseudonocardia (ASV15) and Amycolatopsis (ASV1) - filamentous bacteria with adhesive and antagonistic properties. The connections in the Bacteroidota and Pseudomonadota network suggest the interaction of these groups with Actinobacteriota in multispecies biofilm formation. When considering the richness of bacteria in biofilms, this also confirms the co-occurrence of microorganisms such as taxonomic units belonging to Halomonas (ASV13), Flavobacteriaceae (ASV4; Fig. 7, Supplementary Material 3).

Ascomycota (red nodes) forming a distinct cluster are a common group of fungi associated with decomposition of matter and biofilms in damp environments such as cellars (Fig. 7). The significant role of an unexplained taxon classified as Fungi phylum Incertae sedis may indicate the presence of poorly explored environmental fungi, potentially specific to the conditions of the cheese cellar (high humidity, limited ventilation, presence of volatile organic compounds from fermenting dairy products). Basidiomycota (blue) seemed to be less numerous, but also associated with the main cluster, which may suggest a less central but still important role. The strongly associated cluster around the green node may indicate the role of a phylogenetically unexplained fungal taxon as a potential key organism in this biofilm microbiota.

Discussion

Each ecosystem is characterized by the presence of autochthonous microorganisms that colonize surfaces and form structured biofilms adapted to local environmental conditions5. In built environments, such as historic cheese cellars, biofilms reflect a combination of environmental filtering, surface material properties, and long-term microbial succession. From the surface biofilm, microorganisms can penetrate into the stone, becoming endolithic, whereas bioreceptivity (the ability of a material to be colonized by living organisms) defines the properties of a building that attract and support biological colonization7. The cheese ripening rooms studied here, a more than 100-year-old structure with thick brick and stone walls and cradle vault ceilings, offer a stable microclimate, characterized by low temperature (~ 10 °C), high humidity (~ 85%), and minimal light. These conditions closely resemble those found in natural subterrestrial ecosystems (e.g., caves or crypts), and thus position the cellar as a semi-natural niche for microbial colonization and differentiation. The long-term environmental stability makes this type of setting a model habitat for investigating microbial biofilms in food-related built environments and comparing them with microbial consortia in caves or on exposed stone surfaces.

Building stone is known to provide a habitat for a range of microorganisms (bacteria, archaea, cyanobacteria, algae, fungi and lichens), some of which contribute to biodeterioration, while others stabilize the microbial community12,53. Effective conservation strategies depend on knowing which microorganisms are present, what energy sources they use, and how they influence colonization and succession7,12. For instance, sulfur-oxidizing bacteria such as Acidithiobacillus and Thiobacillus, and nitrifiers like Nitrosomonas represent chemoautotrophs, while heterotrophic taxa including Pseudomonas, Bacillus, and actinomycetes such as Streptomyces contribute to organic matter degradation. Chemoorganotrophic groups are represented by sulfate-reducing bacteria (Desulfovibrio) and denitrifiers (Paracoccus), whereas halophilic microorganisms like Halomonas and archaea (Halobacterium) thrive in salt-enriched niches54,55,56,57,58. Biofilms in such settings enhance survival through retention of water and nutrients59, which is particularly relevant in food storage spaces like cheese ripening rooms. Importantly, previous studies on cave or outdoor stone microbiomes reported abundant extremotolerant taxa, such as Acidobacteria or Cyanobacteria, which were rare or absent in our system60. This contrast suggests that while mineral substrate provides a common ecological scaffold, the presence of organic residues and volatiles derived from cheese production creates selective pressures unique to food-associated built environments61,62. Thus, the cheese cellar represents a hybrid between lithic and food-processing ecosystems, where stone-associated resilience traits co-exist with fermentative and heterotrophic functions linked to dairy maturation.

We observed a clear divergence in the microbial community composition and diversity between the wall and ceiling biofilms, with higher biodiversity and metabolic complexity in wall-associated communities (PD_B1 and PD_B2). This was especially evident in samples taken from the stone surfaces due to the increased microstructural heterogeneity, which, as in natural substrates, favored the development of a more taxonomically and functionally diverse microbiota. Notably, the highest biodiversity occurred in the stone wall biofilm (PD_B2) in comparison to the brick material, which offer increased microstructural heterogeneity and mineral content. Similarly, Cutler and co-workers reported that stone material yields greater concentrations of DNA and gives a more representative picture of endolithic microbial communities53. Our observations suggest that these surfaces supported taxonomically and functionally diverse microbiota, with notable preferences: Flavobacteriaceae, Balneolaceae, Halomonas and Salinisphaera on the walls, and Amycolaptosis, Pseudonocardia, and Micrococcales on ceilings and brick. Cave and monument biofilms are often dominated by Streptomyces, Crossiella, and Pseudonocardia, with Amycolatopsis and Pseudonocardia present but usually at lower relative abundance compared to Streptomyces63,64. Compared to cave and monument studies, our biofilms (especially samples PD_B3 and PD_B4) contained a higher proportion of filamentous Actinobacteriota (Amycolatopsis, Pseudonocardia), with antimicrobial potential. Their ability to produce antibiotics, siderophores, and polyketides may reflect selective pressures to control opportunistic competitors in food-associated environments, a trait less critical in outdoor lithic systems dominated by phototrophs and lichens. The co-occurrence of halotolerant taxa (Halomonas, Salinisphaera) further reflects adaptation to the humid, salt-enriched microclimate of the cellar, while polymer-degrading bacteria (Flavobacteriaceae, Balneolaceae) probably exploit organic residues of dairy origin65,66,67,68,69.

Actinobacteriota, Pseudomonadota, and Bacteroidota, are all involved in adhesion, biofilm matrix formation, and organic matter degradation70. In our study, Actinobacteriota reached up to 93% relative abundance, followed by Pseudomonadota (39%) and Bacteroidota (~ 35%). These taxa play distinct roles in biofilm formation and resilience70. Actinobacteriota such as Amycolatopsis and Pseudonocardia act as potentially keystone taxa: they secrete exopolysaccharides that reinforce matrix cohesion and produce antimicrobials that regulate the community composition71,72. Pseudomonadota, represented for example by Halomonas and Salinisphaera, contribute metabolic flexibility through tolerance to salinity, including nitrate reduction and utilization of simple organic acids, ensuring biofilm activity under fluctuating oxygen levels73,74. Bacteroidota, including Flavobacteriaceae and Balneolaceae, specialize in polymer degradation (e.g., chitinolysis, xylanolysis), releasing nutrients for the community and supporting trophic interactions within the biofilm. Rubrobacter representatives provide stress resistance to desiccation and oxidative damage, while Bacillota and lactic acid bacteria contribute to fermentation, pH modulation, and flavor compound production. Together, these groups illustrate functional complementarity, ensuring structural persistence, resource cycling, and resilience of the biofilm66,71,75,76.

The fungal biofilm components followed similar spatial trends, meaning that the wall and ceiling surfaces, although differing in substrate and orientation, supported overlapping phylum-level groups with distinct quantitative profiles. The dominant fungal phylum across all biofilms was Ascomycota, accounting for 58–96% in the wall biofilms, and 76–84% in the ceiling biofilms. This group is also the basis of other biofilms colonizing buildings, where it is identified as a biodeteriogen77, and other environments78,79. This phylum, widespread in architectural and natural environments, contributes to EPS production, enzymatic activity, and interactions with bacterial communities80,81,82. Minor fungal phyla (Table S3.) probably assist in substrate degradation but remain functionally uncharacterized. The wall biofilms were enriched in such genera as Acremonium and Cladosporium, known for saprotrophic activity and degradation of structural polysaccharides83, while the ceiling biofilms contained more Hypocreales genus Incertae sedis and unidentified fungi (Fungi genus Incertae sedis), consistent with airborne deposition84. These “similar spatial trends” indicate that both bacterial and fungal communities respond to wall vs. ceiling microhabitats in parallel: walls are colonized by metabolically active, surface-adapted taxa, whereas ceilings accumulate more passive, spore-driven communities85.

The functional predictions of the biofilm-forming bacterial and fungal communities indicate that the wall-associated biofilm is metabolically more active than the ceiling biofilm (Figs. 5 and 6). Wall taxa such as Halomonas and Salinisphaera were linked to chemoheterotrophy, denitrification and alternative respiration, reflecting their ability to use nitrate or organic acids as electron acceptors under oxygen-limited conditions73,74,86,87. Fermentative genera including Bacteroides, Lactobacillus and Streptococcus contributed to acid production, while Lysobacter species were associated with chitin degradation and hydrolysis of structural polysaccharides. These complementary functions not only sustain microbial balance within the biofilm but may also influence cheese maturation through acidification, proteolysis, and the breakdown of extracellular biopolymers88,89. The overall dominance of heterotrophic and fermentative pathways in the wall-associated biofilms suggests an adaptation to nutrient-rich, microaerophilic microenvironments, enriched in volatile and organic residues from cheese ripening. Similar metabolic signatures have been described in other food-related built environments, where organic residues support mixed bacterial–fungal biofilms with active carbon turnover and redox cycling88,90.

In contrast, the ceiling biofilms (PD_B3 and PD_B4) were functionally distinct displayed more passive and low-energy-yield metabolic profiles. Predicted enrichment in hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis (CO₂ reduction with H₂), and nitrite respiration indicates the potential formation of localized anaerobic microzones within ceiling biofilms, possibly resulting from restricted gas exchange and higher moisture retention. Although direct methane production was not measured, such predictions are not necessarily artefactual, as micro-anoxic or microaerophilic conditions are common within mature and compact biofilms, even in nominally aerobic environments. These zones can support facultatively anaerobic or methanogenic taxa capable of maintaining energy metabolism through hydrogen- or carbon dioxide–dependent pathways91,92. The presence of these predicted functions therefore likely reflects spatial heterogeneity in oxygen diffusion rather than erroneous functional assignment.

Interestingly, the consistently low abundance of aerobic ammonia oxidation, nitrite oxidation, and nitrification functions acrossall samples predicts minimal nitrifying activity in this environment. Instead, nitrogen cycling appears dominated by denitrifying and nitrate-reducing taxa such as Halomonas and Paracoccus, which couple nitrate reduction to organic matter oxidation54,55,56,57,58. These processes likely support organic matter turnover, nutrient cycling, and maintenance of stable biofilm structures under nutrient-rich yet microaerophilic conditions.

Fungal members of the biofilm, dominated by Ascomycota, likely complement these bacterial processes by contributing extracellular enzyme activity (e.g., cellulases, proteases) and exopolysaccharide production, thereby enhancing biofilm cohesion and substrate degradation81,82. The co-occurrence of bacterial and fungal degraders is a typical feature of mixed biofilms in confined, humid environments such as caves, wine cellars, and cheese-aging chambers93,94,95.

Finally, the ecological network analysis (Fig. 7) provided complementary insight into the structure and potential ecological organization of bacterial and fungal communities in ripening cellar biofilms. The wall-associated biofilms exhibited more complex and highly connected networks, analyzed separately for bacteria and fungi, compared to ceiling-associated ones. These densely clustered, domain-specific structures indicate ecological complementarity and niche partitioning, i.e. processes frequently associated with the stabilization of long-lived microbial consortia96,97. Key taxa such as Pseudonocardia, Amycolatopsis, Halomonas, and unclassified Ascomycota were identified as probable hub organisms. Such hub taxa are often regarded as potentially keystone taxa that promote spatial organization, mediate resource flows, and buffer the community against disturbance98,99. Their roles in secondary metabolite production and substrate degradation likely underpin the functional cohesion observed in wall-associated biofilms.

In contrast, the ceiling biofilms revealed sparser and less modular networks, aligning with their lower biodiversity and metabolic activity. This suggests that ceiling-associated taxa represent more stochastic colonization events shaped by airborne deposition rather than stable cooperative assemblages100. Overall, this network-level differentiation reinforces the role of architectural substrates and physicochemical gradients in shaping not only the taxonomic composition, but also the ecological structuring and stability of microbial communities in built environments15,101.

The strong inter-fungal relationships and the presence of stable clusters highlighted in the network suggest that the fungal microbiota also plays an important role in biofilm formation and potentially influences the surface microbiota of cheeses during the ripening process. It should be noted that the certain moulds (e.g. Penicillium sp., Geotrichum sp.) are known to be important forcheese maturation and the presence of certain fungi may then be beneficial102. However, the presence of unidentified or opportunistic fungi highlights the need for further evaluation of their potential impact on product safety and quality.

Summarizing, the co-occurrence of these taxa in networks suggests the existence of stable, functionally integrated consortia that can modulate the microclimate and cheese ripening conditions. Although interkingdom interactions were not directly analyzed, the parallel bacterial and fungal network structures suggest potential cross-domain coordination, a phenomenon reported in other built and fermentative ecosystems where fungi provide structural scaffolds and bacteria contribute metabolic versatility103.

From a technological perspective, the dominance of heterotrophic and fermentative functions in wall-associated biofilms may play a beneficial role in the cheese ripening process. These functions are associated with the degradation of complex organic compounds (e.g., casein, polysaccharides), production of organic acids. and modulation of pH, i.e. factors that contribute to flavor development, texture changes, and inhibition of spoilage organisms. The presence of xylanolytic and chitinolytic activity may further support the breakdown of structural polysaccharides, potentially originating from the production environment or microbial biomass. Conversely, the occurrence of photoautotrophic and methanogenic functions in ceiling biofilms suggests a more passive or environmental microbiome, less directly involved in cheese maturation. However, such communities may influence the air microbiota and serve as a source of microbial dispersion, possibly affecting the early colonization of cheese surfaces or contributing to the overall microbial terroir of the ripening room15,104,105.

Conclusions

This study provides an initial insight into the microbial ecology of traditional cheese ripening rooms, which function as semi-natural built ecosystems capable of sustaining spatially structured and functionally diverse microbial biofilms. Clear differences were observed between wall- and ceiling-associated biofilms: the wall surfaces, especially stone walls, supported more taxonomically diverse and metabolically active communities, whereas the ceiling biofilms were less diverse, dominated by filamentous Actinobacteriota and airborne fungi.

At the phylum and genus level, Actinobacteriota, Pseudomonadota, and Bacteroidota dominated the bacterial communities, with Pseudonocardia and Amycolatopsis likely acted as structural and defensive potentially keystone taxa, Halomonas and Salinisphaera contributing to nitrogen cycling and stress tolerance, and Flavobacteriaceae and Balneolaceae driving polymer degradation. The fungal communities were dominated by Ascomycota, with abundant Acremonium and Cladosporium on the walls, and Hypocreales and unidentified fungi more abundant on the ceilings.

The ecological network analysis revealed more complex, strongly connected bacterial and fungal networks on the walls than the ceilings, with key hub taxa contributing to biofilm cohesion and resilience. Although interkingdom interactions were not directly analyzed, the parallel bacterial and fungal networks suggest potential cross-domain coordination under the stable environmental filtering of the cellar.

Overall, our results indicate that the microbial assemblages in cheese ripening rooms share some traits with cave and monument microbiomes and display distinctive features linked to dairy-associated selective pressures, such as enrichment in fermentative and polymer-degrading taxa. While these findings are based on a limited sample set and predictive functional tools, they underscore the value of cheese-ripening rooms as model systems for studying microbial succession, ecological filtering, and community specialization in built environments. Future comparative studies, including multi-site sampling, metagenomic or metatranscriptomic validation, and broader temporal monitoring, are needed to confirm and extend these observations.

Data availability

The raw sequencing data have been submitted to the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database under BioProject’s ID: PRJNA927028. All other data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Dang, H. & Lovell, C. R. Microbial surface colonization and biofilm development in marine environments. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 80, 91–138 (2016).

Zhao, A., Sun, J. & Liu, Y. Understanding bacterial biofilms: from definition to treatment strategies. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 13, 1137947 (2023).

Coenye, T. et al. Global challenges and microbial biofilms: identification of priority questions in biofilm research, innovation and policy. Biofilm 8, 100210 (2024).

Marzban, G. & Tesei, D. The extremophiles: adaptation mechanisms and biotechnological applications. Biology (Basel). 14, 412 (2025).

Römling, U. Is biofilm formation intrinsic to the origin of life? Environ. Microbiol. 25, 26–39 (2023).

Sharma, D., Misba, L. & Khan, A. U. Antibiotics versus biofilm: an emerging battleground in microbial communities. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 8, 1–10 (2019).

Gaylarde, C. C. Influence of environment on microbial colonization of historic stone buildings with emphasis on cyanobacteria. Heritage 3, 1469–1482 (2020).

Dyda, M., Pyzik, A., Wilkojc, E., Kwiatkowska-Kopka, B. & Sklodowska, A. Bacterial and fungal diversity inside the medieval Building constructed with sandstone plates and lime mortar as an example of the microbial colonization of a Nutrient-Limited extreme environment (Wawel Royal Castle, Krakow, Poland). Microorganisms 7, 416 (2019).

Carrascosa, C., Raheem, D., Ramos, F., Saraiva, A. & Raposo, A. Microbial biofilms in the food Industry—A comprehensive review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18, 2014 (2021).

Debroy, A., George, N. & Mukherjee, G. Role of biofilms in the degradation of microplastics in aquatic environments. J. Chem. Tech. Biotechnol. 97, 3271–3282 (2022).

Nowicka-Krawczyk, P., Komar, M. & Gutarowska, B. Towards Understanding the link between the deterioration of Building materials and the nature of aerophytic green algae. Sci. Total Environ. 802, 149856 (2022).

Liu, X., Koestler, R. J., Warscheid, T., Katayama, Y. & Gu, J. D. Microbial deterioration and sustainable conservation of stone monuments and buildings. Nat. Sustain. 3, 991–1004 (2020).

Faccia, M., Natrella, G., Gambacorta, G. & Trani, A. Cheese ripening in nonconventional conditions: A multiparameter study applied to protected geographical indication Canestrato Di Moliterno cheese. J. Dairy. Sci. 105, 140–153 (2022).

Dias, J. M. et al. Impact of environmental conditions on the ripening of Queijo de Évora PDO cheese. J. Food Sci. Technol. 58, 3942–3952 (2021).

Busetta, G. et al. The wooden shelf surface and cheese rind mutually exchange microbiota during the traditional ripening process. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 409, 110478 (2024).

Sun, L., D’Amico, D. J. & Composition Succession, and Source Tracking of Microbial Communities throughout the Traditional Production of a Farmstead Cheese. mSystems. 6, (2021).

Ruhal, R. & Kataria, R. Biofilm patterns in gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Microbiol. Res. 251, 126829 (2021).

Banach, A. M. et al. Effects of summer flooding on floodplain biogeochemistry in Poland; implications for increased flooding frequency. Biogeochemistry 92, 247–262 (2009).

Klindworth, A. et al. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, e1–e1 (2013).

Schmidt, P. A. et al. Illumina metabarcoding of a soil fungal community. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 65, 128–132 (2013).

Bolyen, E. et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible Microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 852–857 (2019).

Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods. 13, 581–583 (2016).

Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D590 (2012).

Abarenkov, K. et al. The UNITE database for molecular identification and taxonomic communication of fungi and other eukaryotes: sequences, taxa and classifications reconsidered. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, D791 (2023).

Nilsson, R. H. et al. The UNITE database for molecular identification of fungi: handling dark taxa and parallel taxonomic classifications. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D259–D264 (2019).

Bokulich, N. A. et al. Optimizing taxonomic classification of marker-gene amplicon sequences with QIIME 2’s q2-feature-classifier plugin. Microbiome 6, 1–17 (2018).

Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J. 17, 10–12 (2011).

Andrews, S. FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=2781642 (2010).

Lozupone, C., Knight, R. & UniFrac A new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 8228–8235 (2005).

Lozupone, C. A., Hamady, M., Kelley, S. T. & Knight, R. Quantitative and qualitative β diversity measures lead to different insights into factors that structure microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 1576–1585 (2007).

R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, (2024). https://www.r-project.org/

Faith, D. P. Conservation evaluation and phylogenetic diversity. Biol. Conserv. 61, 1–10 (1992).

Kindt, R. BiodiversityR: package for community ecology and suitability analysis. Version 2.16-1, https://cran.r-project.org/package=BiodiversityR (2018).

Jost, L. Entropy and diversity. Oikos 113, 363–375 (2006).

Lefcheck, J. S. Diversity as effective numbers – sample(ecology). Blog post at https://jonlefcheck.net/2012/10/23/diversity-as-effective-numbers/ (2012).

Paradis, E. & Schliep, K. Ape 5.0: an environment for modern phylogenetics and evolutionary analyses in R. Bioinformatics 35, 526–528 (2019).

Leinster, T. & Cobbold, C. A. Measuring diversity: the importance of species similarity. Ecology 93, 477–489 (2012).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 57, 289–300 (1995).

Louca, S., Parfrey, L. W. & Doebeli, M. Decoupling function and taxonomy in the global ocean Microbiome. Science 353, 1272–1277 (2016).

Nguyen, N. H. et al. FUNGuild: an open annotation tool for parsing fungal community datasets by ecological guild. Fungal Ecol. 20, 241–248 (2016).

Mangnier, L. et al. A systematic benchmark of integrative strategies for microbiome-metabolome data. Commun. Biol. 8, 1–17 (2025).

Legendre, P. & Gallagher, E. D. Ecologically meaningful transformations for ordination of species data. Oecologia 129, 271–280 (2001).

Wickham, H. Data analysis. In: ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. 189–201. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24277-4_9 (Springer, 2016).

Kassambara, A. ggplot2 based publication ready plots. R Package Ggpubr Version 0 6 1 CRAN. https://doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.PACKAGE.GGPUBR (2025).

Kolde, R. Pretty heatmaps. R package pheatmap version 1.0.13, CRAN, (2025). https://doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.PACKAGE.PHEATMAP

Oksanen, J. et al. Community ecology package. R Package Vegan Version 2 7-1 CRAN. https://doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.PACKAGE.VEGAN (2025).

Venables, W. N. & Ripley, B. D. Modern Applied Statistics with S (Springer, 2002). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-21706-2

McMurdie, P. J. & Holmes, S. Phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of Microbiome census data. PLoS One. 8, e61217 (2013).

Csárdi, G. & Nepusz, T. The igraph software package for complex network research. R package igraph, CRAN, (2006). https://cran.r-project.org/package=igraph

Jr, F. E. H. Harrell Miscellaneous. R package Hmisc version 5.2-3 (CRAN, 2025). https://doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.PACKAGE.HMISC.

van den Boogaart, K. G., Tolosana-Delgado, R. & Bren, M. Compositional data analysis. R package compositions version 2.0–9, CRAN, (2025). https://doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.PACKAGE.COMPOSITIONS

Kassambara, A. Pipe-friendly framework for basic statistical tests. R Package Rstatix Version 0 7 2 CRAN. https://doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.PACKAGE.RSTATIX (2023).

Cutler, N. A., Oliver, A. E., Viles, H. A. & Whiteley, A. S. Non-destructive sampling of rock-dwelling microbial communities using sterile adhesive tape. J. Microbiol. Methods. 91, 391–398 (2012).

Jones, D. S., Schaperdoth, I. & Macalady, J. L. Biogeography of sulfur-oxidizing Acidithiobacillus populations in extremely acidic cave biofilms. ISME J. 10, 2879–2891 (2016).

Martin-Pozas, T. et al. Microbial and geochemical variability in sediments and biofilms from Italian gypsum caves. Microb. Ecol. 88, 1–19 (2025).

Turrini, P., Chebbi, A., Riggio, F. P. & Visca, P. The geomicrobiology of limestone, sulfuric acid speleogenetic, and volcanic caves: basic concepts and future perspectives. Front. Microbiol. 15, 1370520 (2024).

Schröer, L., Boon, N., De Kock, T. & Cnudde, V. The capabilities of bacteria and archaea to alter natural Building stones – A review. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegradation. 165, 105329 (2021).

Kosznik-Kwaśnicka, K., Golec, P., Jaroszewicz, W., Lubomska, D. & Piechowicz, L. Into the unknown: microbial communities in Caves, their Role, and potential use. Microorganisms 10, 222 (2022).

Skipper, P. J. A., Skipper, L. K. & Dixon, R. A. A metagenomic analysis of the bacterial Microbiome of limestone, and the role of associated biofilms in the biodeterioration of heritage stone surfaces. Sci. Rep. 12, 1–18 (2022).

He, J. et al. From surviving to thriving, the assembly processes of microbial communities in stone biodeterioration: A case study of the West lake UNESCO world heritage area in China. Sci. Total Environ. 805, 150395 (2022).

Ozturkoglu-Budak, S. et al. Volatile compound profiling of Turkish divle cave cheese during production and ripening. J. Dairy. Sci. 99, 5120–5131 (2016).

Santamarina-García, G. et al. Relationship between the dynamics of volatile aroma compounds and microbial succession during the ripening of Raw Ewe milk-derived idiazabal cheese. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 6, 100425 (2023).

Gogoleva, N. et al. Microbial tapestry of the Shulgan-Tash cave (Southern Ural, Russia): influences of environmental factors on the taxonomic composition of the cave biofilms. Environ. Microbiome. 18, 1–23 (2023).

Rangseekaew, P. & Pathom-Aree, W. Cave actinobacteria as producers of bioactive metabolites. Front. Microbiol. 10, 436943 (2019).

Louati, M. et al. Elucidating the ecological networks in stone-dwelling microbiomes. Environ. Microbiol. 22, 1467–1480 (2020).

Ding, X. et al. Microbiome characteristics and the key biochemical reactions identified on stone world cultural heritage under different climate conditions. J. Environ. Manage. 302, 114041 (2022).

Cho, J. Y. et al. Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) degradation by the newly isolated marine Bacillus sp. JY14. Chemosphere 283, 131172 (2021).

Al Farraj, D. A. et al. Exploring the potential of halotolerant bacteria for biodegradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon. Bioprocess. Biosyst Eng. 43, 2305–2314 (2020).

Tomczyk-Żak, K. & Zielenkiewicz, U. Microbial diversity in caves. Geomicrobiol. J. 33, 20–38 (2016).

69 et al. Diversity and composition of culturable microorganisms and their biodeterioration potentials in the sandstone of Beishiku Temple, China. Microorganisms 11, 429 (2023).

Yaradoddi, J. S. & Kontro, M. H. Actinobacteria: ecology, diversity, classification and extensive applications. In: Actinobacteria: Ecology, diversity, Classification and Extensive Applications. Eds. Yaradoddi, J. S., Kontro, M. H., Ganachari, S. V. 69–88 (Springer Nature Singapore, 2022).

El Othmany, R., Zahir, H., Ellouali, M. & Latrache, H. Current Understanding on adhesion and biofilm development in actinobacteria. Int. J. Microbiol. 1, 6637438 (2021).

Bisaccia, M. et al. Bacterial diversity of marine biofilm communities in Terra Nova Bay (Antarctica) by Culture-Dependent and -Independent approaches. Environ. Microbiol. 27, e70045 (2025).

Joshi, R. V., Gunawan, C. & Mann, R. We are one: multispecies metabolism of a biofilm consortium and their treatment strategies. Front. Microbiol. 12, 635432 (2021).

Mihajlovski, A., Gabarre, A., Seyer, D., Bousta, F. & Di Martino, P. Bacterial diversity on rock surface of the ruined part of a French historic monument: the Chaalis abbey. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegradation. 120, 161–169 (2017).

Saadouli, I. et al. Diversity and adaptation properties of actinobacteria associated with Tunisian stone ruins. Front. Microbiol. 13, 997832 (2022).

Vázquez-Nion, D., Rodríguez-Castro, J., López-Rodríguez, M. C., Fernández-Silva, I. & Prieto, B. Subaerial biofilms on granitic historic buildings: microbial diversity and development of phototrophic multi-species cultures. Biofouling 32, 657–669 (2016).

Ren, B. et al. A comprehensive assessment of fungi in urban sewer biofilms: community structure, environmental factors, and symbiosis patterns. Sci. Total Environ. 806, 150728 (2022).

Mukhebi, D. W., Musangi, C. R., Isoe, E. M., Neondo, J. O. & Mbinda, W. M. Endophytic and epiphytic metabarcoding reveals fungal communities on cashew phyllosphere in Kenya. PLoS One. 19, e0305600 (2024).

Debnath, A., Das, B., Devi, M. S. & Ram, R. M. Microbial polymers: applications and ecological perspectives. In: Microbial Polymers: Applications and Ecological Perspectives. 45–68, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-0045-6_2 ((Springer Singapore, 2021).

Shaffer, J. P. et al. Transcriptional Profiles of a Foliar Fungal Endophyte (Pestalotiopsis, Ascomycota) and Its Bacterial Symbiont (Luteibacter, Gammaproteobacteria) Reveal Sulfur Exchange and Growth Regulation during Early Phases of Symbiotic Interaction. mSystems 7, (2022).

Manici, L. M., Caputo, F., De Sabata, D. & Fornasier, F. The enzyme patterns of Ascomycota and basidiomycota fungi reveal their different functions in soil. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 196, 105323 (2024).

Baldrian, P. et al. Production of extracellular enzymes and degradation of biopolymers by saprotrophic microfungi from the upper layers of forest soil. Plant. Soil. 338, 111–125 (2011).

Yan, D. et al. Diversity and composition of airborne fungal community associated with particulate matters in Beijing during haze and non-haze days. Front. Microbiol. 7, 185348 (2016).

Gaylarde, C. C. & Baptista-Neto, J. A. Microbiologically induced aesthetic and structural changes to dimension stone. Npj Mater. Degrad. 5, 1–8 (2021).

Wang, L. & Shao, Z. Aerobic denitrification and heterotrophic sulfur oxidation in the genus Halomonas revealed by six novel species characterizations and Genome-Based analysis. Front. Microbiol. 12, 652766 (2021).

He, W. et al. The diversity and nitrogen metabolism of culturable Nitrate-Utilizing bacteria within the oxygen minimum zone of the Changjiang (Yangtze River) estuary. Front. Mar. Sci. 8, 720413 (2021).

Ghosh, S. et al. Engineered biofilm: innovative nextgen strategy for quality enhancement of fermented foods. Front. Nutr. 9, 808630 (2022).

Neviani, E., Gatti, M., Gardini, F. & Levante, A. Microbiota of cheese ecosystems: A perspective on cheesemaking. Foods 14, 830 (2025).

Bertuzzi, A. S. et al. Omics-Based Insights into Flavor Development and Microbial Succession within Surface-Ripened Cheese. mSystems. 3, (2018).

Duarte, M. S. et al. Multiple and flexible roles of facultative anaerobic bacteria in microaerophilic oleate degradation. Environ. Microbiol. 22, 3650–3659 (2020).

Ceriotti, G., Borisov, S. M., Berg, J. S. & De Anna, P. Morphology and size of bacterial colonies control anoxic microenvironment formation in porous media. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 17471–17480 (2022).

Espinosa-Ortiz, E. J., Rene, E. R. & Gerlach, R. Potential use of fungal-bacterial co-cultures for the removal of organic pollutants. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 42, 361–383 (2022).

Cailhol, D. et al. Fungal and bacterial outbreak in the wine vinification area in the Saint-Marcel show cave. Sci. Total Environ. 733, 138756 (2020).

Turrini, P. et al. The microbial community of a biofilm lining the wall of a pristine cave in Western new Guinea. Microbiol. Res. 241, 126584 (2020).

Widder, S. et al. Challenges in microbial ecology: Building predictive Understanding of community function and dynamics. ISME J. 10, 2557–2568 (2016).

Komar, M. et al. Metabolomic analysis of photosynthetic biofilms on Building façades in temperate climate zones. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegradation. 169, 105374 (2022).

Banerjee, S., Schlaeppi, K. & van der Heijden, M. G. A. Keystone taxa as drivers of microbiome structure and functioning. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16, 567–576 (2018).

Xiong, X. et al. Keystone species determine the selection mechanism of multispecies biofilms for bacteria from soil aggregates. Sci. Total Environ. 773, 145069 (2021).

Bontemps, Z., Moënne-Loccoz, Y. & Hugoni, M. Stochastic and deterministic assembly processes of microbial communities in relation to natural attenuation of black stains in Lascaux Cave. mSystems. 9, (2024).

Jo, J., Price-Whelan, A. & Dietrich, L. E. P. Gradients and consequences of heterogeneity in biofilms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 20, 593–607 (2022).

Lessard, M. H., Viel, C., Boyle, B., St-Gelais, D. & Labrie, S. Metatranscriptome analysis of fungal strains penicillium Camemberti and geotrichum candidum reveal cheese matrix breakdown and potential development of sensory properties of ripened Camembert-type cheese. BMC Genom. 15, 1–13 (2014).

Floc’h, J. B. et al. Inter-Kingdom networks of Canola Microbiome reveal Bradyrhizobium as keystone species and underline the importance of bulk soil in microbial studies to enhance Canola production. Microb. Ecol. 84, 1166–1181 (2021).

Somers, E. B., Johnson, M. E. & Wong, A. C. L. Biofilm formation and contamination of cheese by nonstarter lactic acid bacteria in the dairy environment. J. Dairy. Sci. 84, 1926–1936 (2001).

Ibrahim, R. A. et al. Neoteric biofilms applied to enhance the safety characteristics of Ras cheese during ripening. Foods 12, 3548 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank Jerzy Dejk of the Potulicka Foundation for granting access to the cheese ripening room and assisting with sample collection.

Funding

This work was supported by the Potulicka Foundation Economic Center (project no. 1/6-40-21-10-0603-0018-0049).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.G. - Conceptualization, sampling, experimental work, data analysis, data visualization, writing original draft, writing review and editing. K.K. - Literature review, writing original draft. A.K. - Conceptualization, sampling, data analysis, writing original draft. A.B. – Experimental work, data analysis, writing original draft. S.J. - Bioinformatic analysis, data visualization. J.P. – Provision of research materials, project funding. A.W. – Conceptualization, funding acquisition, sampling, writing review and editing, supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Goraj, W., Kagan, K., Kuźniar, A. et al. Spatial and functional differentiation of microbial biofilms in a traditional cheese ripening environment. Sci Rep 15, 45638 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30318-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30318-5