Abstract

Sustainable production of CH4, an industrially important gas, from renewable resources presents a critical solution to energy security challenges. This study demonstrates photocatalytic conversion of glucose, a model biomass compound, to CH4 using a metal co-catalyst loaded TiO2 photocatalyst under ambient conditions. We confirmed that CH4 was formed through photocatalytic reduction of CO2, which was generated in situ during glucose oxidation, establishing a closed-loop conversion of biomass-derived carbon within a single reaction system. PtOx-TiO2 (x = 0, 1) exhibited significantly higher activity for CH4 production than PdOx-TiO2 (x = 0, 1). The CH4 yield with PtOx loading was approximately ten times greater than that obtained with PdOx loading, with an optimal PtOx loading of 2.0 wt% yielding the highest CH4 amount of 10.600 µmol L− 1 after 6 h. In contrast, PdOx-TiO2 showed a higher selectivity for H2 generation. Analysis of the reaction products, including sugars (arabinose, erythrose, and glyceraldehyde) and organic acids (formic acid, acetic acid, and gluconic acid), elucidated the glucose degradation pathways. The mechanism of CH4 formation was identified as the methanation of CO2 and H+, both produced during photocatalytic oxidation of glucose and water. Deuterium-labeling experiments further revealed that the hydrogen atoms in CH4 originated from both glucose decomposition and water splitting. These findings demonstrate a novel and sustainable tandem photocatalytic process that integrates oxidation and reduction reactions on a single catalyst surface, providing mechanistic and practical insights into the direct conversion of biomass into CH4 under mild conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Biomass refers to organic materials derived from living organisms that can be used as renewable energy resources. Biomass possesses carbon-neutral characteristics that do not affect atmospheric CO2 concentrations1,2. Therefore, it has attracted attention as a climate change countermeasure3,4, and the utilization of biomass is being promoted globally toward the construction of energy supply processes that do not depend on fossil resources5,6. Furthermore, non-food biomass resources are attracting attention as they do not compete with food production7,8. Agricultural and forestry residues such as rice straw and thinned timber represent particularly promising examples of these resources9,10, and their effective utilization is expected to contribute to the realization of a sustainable circular society.

Since biomass is a sustainable resource, the production of useful substances through its conversion has attracted global attention11,12,13. Biomass primarily yields fuel and chemicals14,15. Fuels include bioethanol, which is produced by processes such as catalytic treatment under high-temperature and high-pressure conditions or microbial fermentation16,17. Biomass is also converted into useful chemicals, such as sugars18,19, which are in high demand as raw materials for pharmaceuticals and functional foods, and organic acids15,20, which possess high industrial utility value as basic chemicals. Biomass can be converted into a diverse range of useful substances, and conversion methods are being actively researched worldwide. Nevertheless, existing biomass conversion processes face numerous challenges, including the requirement of energy-intensive reaction conditions at high temperatures and pressures, significant environmental burdens, and high capital investment and operating costs21,22,23. Consequently, concerns have been raised regarding the sustainability of these conversion processes, and there is a demand for the development of novel biomass conversion processes that operate under milder conditions with reduced environmental impacts and enhanced economic viability.

In recent years, photocatalysis has attracted attention as a method of converting biomass into useful substances24,25. Photocatalysts are materials that absorb light, which is a renewable energy source, and promote oxidation and reduction reactions under mild conditions at ambient temperature and pressure26. When semiconductor photocatalysts are irradiated with light having energy greater than their band gap, electrons in the valence band are excited to the conduction band, and simultaneously, holes are generated in the valence band. These holes cause oxidation reactions, whereas excited electrons cause reduction reactions26. Furthermore, it is known that these oxidation and reduction reactions generate reactive oxygen species, such as hydroxyl radicals and superoxide anion radicals, from water and oxygen27.

The generation of various fuel sources and useful chemicals has been confirmed through photocatalytic biomass conversion. For example, Speltini et al. confirmed H2 generation by irradiating sunlight on cellulose suspensions containing Pt-loaded TiO228, and Wang et al. converted C2-C6 compounds such as ethylene glycol, xylitol, and sorbitol, to methanol using Cu-loaded titanium oxide nanorods29. Furthermore, Paola et al. demonstrated vanillin production through ferulic acid conversion using TiO2 or TiO2-WO330, and Nakata et al. confirmed the generation of sugars such as arabinose, erythrose, glyceraldehyde, and D-arabino-1,4-lactone through D-fructose decomposition using TiO231.

Future fossil fuel shortages owing to the depletion of fossil resources have become a serious challenge32,33. This depletion necessitates the identification and development of alternative feedstocks for both energy production and chemical manufacturing. CH4 emerges as a particularly promising candidate due to its exceptional versatility across multiple industrial applications34,35. It functions not only as synthesis gas and fuel for power generation36, but also serves as a raw material for manufacturing basic chemicals such as ethylene and methanol37,38. This broad applicability positions CH4 as an industrially crucial gas that could help address the challenges posed by diminishing fossil fuel resources. Currently, CH4 production relies primarily on natural gas refining39,40. While this production method is considered low risk and economical41,42, it presents significant sustainability concerns given the ongoing depletion of fossil resources43,44. Based on the above background, in recent years, biogas upgrading and power-to-gas (PtG) technologies have attracted considerable attention from the perspective of reducing fossil resources consumption45,46,47. Biogas upgrading is a process to obtain high-purity CH4 by removing carbon dioxide (CO2), water vapor, hydrogen sulfide (H2S), and other impurities from biogas, a renewable resource45,46. However, this process involves complex purification steps, leading to high costs and significant energy consumption48,49. In contrast, PtG technology produces methane by electrolyzing water with renewable energy sources such as wind and solar power to generate H2, which is then reacted with CO245,47. Nevertheless, this approach still faces critical challenges in terms of sustainability, since water electrolysis requires substantial energy input and the subsequent methanation reaction requires heating in the intermediate temperature range (300–400 °C)49.

From the perspective of sustainability, CO2 methanation has attracted attention50,51. This is a reaction that generally synthesizes CH4 by passing H2 and CO2 through catalysts under high temperatures and pressures52,53. While CO2 is typically emitted when CH4 is utilized, CO2 methanation recovers the emitted CO2 and synthesizes CH4 again, theoretically enabling carbon neutrality54. However, since the reaction must be conducted generally under mid-temperature (300–500 °C) and high-pressure, challenges include energy consumption and high risk55. Although recent studies have explored the reaction under low temperature (ca. 150 °C), such as photothermal methods56,57, the reaction still requires energy consumption for heating. In contrast, photocatalytic CO2 methanation utilizes renewable solar energy to convert CO2 and water into CH4 and has attracted significant attention as a sustainable pathway for CH4 production58,59,60. However, photocatalytic CO2 methanation still has low CH4 production efficiency and high cost for CO2 recovery and supply, and the design of high-pressure systems60. Based on the above background, this study focused on photocatalytic biomass conversion to establish a sustainable CH4 production process. Specifically, glucose was selected as a biomass derived compound, and CH4 generation via photocatalytic degradation was investigated, since the theoretical potential of glucose as a carbon source, which yields up to six CH4 molecules per glucose molecule.

Based on the above background, this study focused on photocatalytic biomass conversion to establish a sustainable CH4 production process. Specifically, glucose was selected as a biomass derived compound, and CH4 generation via photocatalytic degradation was investigated. Furthermore, to improve the photocatalytic activity, this study investigated the loading of metal co-catalysts, and PtOx and PdOx (x = 0, 1) were selected, as previous studies have reported that the loading of these co-catalysts is effective for CH4 production61,62. Using TiO2 loaded with these metal co-catalysts, the amount of CH4 generated by glucose degradation was compared and examined to determine the optimal metal co-catalyst for CH4 production. Additionally, elucidation of the CH4 generation mechanism was attempted through a detailed analysis of the glucose degradation pathways and product distribution in photocatalytic reactions.

Experimental

Preparation of metal co-catalyst-loaded TiO2

PtOx and PdOx particles were loaded on the TiO2 (here after, PtOx-TiO2 and PdOx-TiO2, respectively) surface using the photodeposition method63. Ultrapure water (50 mL) and 2-propanol (Wako Pure Chemical, 99.7%, 50 mL) were mixed and TiO2 (P25, Evonik) was added. Hexachloroplatinic (IV) acid hexahydrate (Wako Pure Chemical, 98.5%) or palladium (II) chloride (Wako Pure Chemical, 99.0%) was added as the metal precursor at 0.5 wt% of TiO2 based on the previous work61. The prepared suspension was stirred while being irradiated with ultraviolet (UV) light for 2 h using a 300 W HgXe lamp (UV-7, U-VIX). The light irradiation intensity was set at 6.0 mW cm− 2. After light irradiation, the suspension was filtered by suction and the obtained powder was washed with ultrapure water and dried at 110 °C for 12 h.

Characterization of photocatalysts

The prepared photocatalysts were characterized using the following methods. To investigate the changes in the crystal structure of TiO2 caused by the loading of metal co-catalysts (PtOx and PdOx), X-ray diffraction analysis was performed using an X-ray diffractometer (SmartLab, Rigaku). Measurements were conducted using Cu-Kα radiation with a tube voltage of 45 kV, tube current of 200 mA, scanning range of 10–60°, and scanning speed of 5.0° min− 1. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis was performed using an X-ray photoelectron spectrometer (JPS9030, JEOL). Mg Kα radiation (tube voltage, 10 kV; tube current, 20 mA) was used as the X-ray source and charge correction was performed using the C 1s peak (285.0 eV) as a reference. H2-TPR was performed in a quartz U-tube and ca. 200 mg of sample was used in each measurement using an automated flow chemisorption analyzer (ChemBET Pulsar, Anton Paar). The samples were pretreated under He flow until the temperature was ramped to 150 °C at a rate of 20 °C min− 1. The flow of 5% H2/Ar was then switched into the system, and the sample was heated up to 800 °C at a rate of 5 °C min− 1. To confirm the microstructure of the metal co-catalysts on the TiO2 surface in detail, TEM images were obtained and the diameter measurements of PtOx and PdOx were performed for 20–30 particles using a 200 kV field-emission transmission electron microscope (JEM-2100 F, JEOL). Scanning Transmission Electron Microscope (STEM) images were obtained using a 200 kV schottky field-emission atomic-resolution scanning transmission electron microscope (JEM-ARM200F, JEOL). The specific surface area of the photocatalyst was determined by the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method and was analyzed using a high-precision gas adsorption analyzer (BELSORP-mini II, Microtrac) after the sample was degassed in vacuum at 120 °C for 12 h. Diffuse reflectance spectra were measured using an UV-Vis spectrophotometer (UV-2600i, Shimadzu) under the following conditions: wavelength of 200–800 nm, slit width of 5.0 nm, low-speed scanning, and light source switching wavelength of 300 nm. The obtained spectra were processed using Kubelka-Munk transformation. Photoluminescence (PL) spectra of the photocatalysts were measured using a spectrofluorometer (JASCO, FP-6500). The measurement conditions were as follows: mode, emission; slit width, 5 nm; response, 2 s; sensitivity, low; excitation wavelength, 380 nm; starting wavelength, 350 nm; ending wavelength, 450 nm; data interval, 0.1 nm; and scan speed, 100 nm/min. Electrochemical impedance measurement (EIS) conditions were electrolyte: 0.1 mol L− 1 Na2SO4 (99.0%, Wako Pure Chemical Industries), reference electrode: Ag/AgCl electrode.

Preparation of photoelectrode

The photoelectrode was fabricated using the following method. 30 mg of the powdered photocatalyst, 50 µL of 20 wt% Nafion solution (Wako Pure Chemical Industries), and 1 mL of ultrapure water were mixed and stirred for 30 min to prepare the photocatalyst suspension. 600 µL of this photocatalyst suspension was drop-casted onto fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO, active area of ca. 2.25 cm2) coated glass, which were cleaned with ethanol (99.5%, Wako Pure Chemical Industries) before the casting, with an attached tape (1 cm width). The obtained sample was heat-treated at 120 °C for 1 h in a drying oven. The tape was removed, and a Tefloncoated Cu wire was soldered onto the exposed FTO part using a Cerasolzer (Kuroda Techno.). Subsequently, all parts exposed to Cerasolzer and FTO were coated with epoxy resin to create the photoelectrode.

Glucose decomposition reaction

The reaction vessel contained a solution of glucose (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, 98.0%) dissolved in 20 mL of ultrapure water to achieve a concentration of 25 mmol L− 1, along with 20 mg of the photocatalyst. To maintain a constant reaction temperature, a cool plate was placed on a magnetic stirrer, and the reaction vessel was positioned on top. Prior to light irradiation, the mixture was stirred in the dark for 30 min and samples were collected from both the gas and liquid phases. A 300 W HgXe lamp (UV-7, U-VIX) was used as the light source, and the light intensity was set to 50 mW cm− 2. Gas samples (1 mL) were collected 3 h after the start of the light irradiation, and 1 mL of gas and 500 µL of liquid were collected after 6 h. The collected liquid samples were centrifuged, and the supernatant was filtered through a filter (RephiQuik Syringe Filter, pore size 0.22 μm, RephiLe Bioscience, Ltd.) for recovery.

Figure S1 and S2 represent a schematic overview and picture of the experimental setup respectively. In this study, a reactor was placed on a cool plate positioned above a magnetic stirrer. An aqueous glucose solution and photocatalyst were introduced into the reactor, and UV irradiation was applied to the reaction solution through a quartz glass window from the side. The gas chamber inside the reactor has a volume of ca. 5 mL.

GC and HPLC analysis

The products obtained from glucose decomposition were analyzed as follows: quantitative analysis of CH4 and CO2 was conducted using a gas chromatograph (GC, GC2014, Shimadzu) with flame ionization detector (FID) detection connected to a methanizer (MTN-1, Shimadzu). A packed column (GC Stainless Column 4.0 m×3.0 mm I.D. Porapak Q 50/80, Shinwa Chemical Industries) was used with a column temperature of 40 °C, flow rate of 31 mL min− 1, detector temperature of 150 °C, and injection port temperature of 150 °C. Pure nitrogen was used as the carrier gas. Quantification of CH4 and CO2 in this study was performed as follows. First, 1 mL of the gas phase in the reaction vessel was sampled and injected into the GC for analysis. Based on the obtained peak areas, the concentrations of the target gases in 1 mL of the gas phase (ppm) were determined using the single-point calibration method. As standard samples, push-can type standard gases of methane (GL Sciences, 99.9%), and carbon dioxide (GL Sciences, 99.9%) were used. Subsequently, from the calculated ppm values, the volume (mL) of each target gas contained in 1 mL of the gas phase was obtained, and the amount of gas produced was calculated by dividing this volume by the standard molar volume of an ideal gas (22.4 × 103 mL mol− 1).

The quantitative analysis of H2 was performed using a GC (GC2014, Shimadzu) with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD). A packed column (GC Stainless Column 2.0 m×3.0 mm I.D. Molecular Sieve 13 × 60/80, Shinwa Chemical Industries) was used, with the column temperature set to 50 °C, flow rate to 10 mL min− 1, detector temperature to 100 °C, and injection port temperature to 70 °C. Pure argon was used as the carrier gas. Quantification of H2 this study was performed in the same method for CH4 and CO2. As standard samples, push-can type standard gases of hydrogen (GL Sciences, 99.99%) were used.

The starting material, glucose, and other sugars produced after the reaction were labeled with 4-aminobenzoic acid ethyl ester (ABEE, Tokyo Chemical Industry) and then subjected to qualitative and quantitative analysis using high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, Shimadzu). ABEE labeling was performed according to the following procedure: First, ABEE, sodium cyanoborohydride (Tokyo Chemical Industry), and acetic acid (Wako Pure Chemical Industries) were mixed at a molar ratio of 8:2:27, and the ABEE labeling reagent was prepared by dissolving the mixture in methanol (Wako Pure Chemical Industries) equivalent to 9 times the total volume of the three substances contained in the mixture. To 40 µL of ABEE labeling reagent, 10 µL of the sample was added and stirred for 30 s. Subsequently, centrifugation was performed at 10,000×g for 2 min using a centrifuge (3780, KUBOTA). The solution was placed in a block bath (DB105, SCINICS) and incubated at 80 °C for 1 h. After incubation, the sample was removed and air cooled for 2 min to return to room temperature. Subsequently, centrifugation was performed at 10,000×g for 2 min using a centrifuge. Ultrapure water (200 µL) and chloroform (200 µL; Wako Pure Chemical Industries) were added to the sample, stirred for 1 min, and centrifuged again under the same conditions. From the solution separated into two layers, 150 µL of the supernatant was collected, diluted with 300 µL of ultrapure water, and centrifuged under the same conditions. This sample was used for HPLC measurement. A reverse-phase column (CAPCELL PAK C18 AQ, column 150 × 4.6 mm I.D., OSAKA SODA) was used, and a wavelength of 305 nm was detected using a UV detector (SPD-20 A, Shimadzu). The column temperature was set to 40 °C, flow rate was 1.0 mL min− 1, injection volume was 20 µL, and elution time was 60 min. The carrier solution used was a mixture of 20 mmol L− 1 ammonium acetate aqueous solution (Wako Pure Chemical Industries) and acetonitrile (Wako Pure Chemical Industries) at a volume ratio of 87:13. For gluconic acid, formic acid, and acetic acid quantification, HPLC (Shimadzu) was used with an organic acid analysis column (Rezex ROA-Organic Acid, 300 mm×7.8 mm I.D., Phenomenex) and UV detection at 210 nm. A 2.5 mmol L− 1 sulfuric acid solution was used as the mobile phase with a flow rate of 0.5 mL min− 1 at a column temperature of 60 °C.

Deuterium labeling experiments

To analyze the reaction mechanism through deuterium labeling, photocatalytic reactions were conducted using D2O instead of ultrapure water. In the reaction vessel, 20 mg of PtOx-TiO2 with a PtOx loading rate of 0.5 wt% relative to TiO2 was added, and 20 mL of D2O was added. The reaction was performed in a closed system, using a lid equipped with a septum for gas sampling. UV light (light irradiation intensity: 50 mW cm− 2) was irradiated using a HgXe lamp (UV-7, U-VIX). After stirring in the dark for 30 min, the UV irradiation was initiated. Gas samples (1 mL) were collected from the gas phase 3 and 6 h after the start of the reaction, and molecular weight analysis of CH4 was performed using GC-MS (GCMSQP2020, Shimadzu). RT-Msieve 5 A (RESTEK) was used as the separation column. The column flow rate was 32.9 mL min− 1, the column oven temperature was 30 °C, the vaporization chamber temperature was 150 °C, the interface temperature was 190 °C, the detector voltage was 0.1 kV, the split ratio was 20, and m/z was set to 16, 17, 18, 19, and 20.

CH4 generation from CO2 aqueous solution

To verify the hypothesis that CH4 generation by the photocatalytic reaction originates from methanation, which is the reaction between CO2 and H+, CH4 generation experiments using CO2 aqueous solutions were conducted. To maintain a constant reaction temperature, a cool plate was placed on a magnetic stirrer, and the reaction vessel was positioned on top. Ultrapure water (20 mL) and the photocatalyst (20 mg) were added to the sealed reaction vessel. Before starting the light irradiation, CO2 bubbling was performed for 30 min on the solution in the reaction vessel. Subsequently, stirring was conducted in the dark, and the gas samples were collected. A 300 W HgXe lamp (UV-7, U-VIX) was used as the light source, and the light irradiation intensity was set to 50 mW cm− 2. Gas samples (1 mL each) were collected 3 and 6 h after the start of light irradiation.

Catalytic reaction of CO2 and H+ in the dark

To confirm whether the CH4 generated from CO2 and H+ could be produced by a catalytic reaction in the dark as a control, the following experiment was conducted. A cool plate was installed on a magnetic stirrer to maintain a constant reaction temperature, and the reaction vessel was placed on top. The reaction vessel was charged with 20 mL of ultrapure water containing 25 mmol L− 1 glucose and 20 mg of the photocatalyst. The reaction vessel was sealed with a lid for gas sampling. Pure hydrogen (99.99%) and pure CO2 (99.9%) were added to the reaction vessel in 50 µL volumes, and 1.0 mL of gas from within the reaction vessel was sampled for quantitative analysis before addition, 3 h after addition, and 6 h after addition in the dark.

Quantitative analysis of CH4 was performed using a gas chromatograph (GC2014, Shimadzu) equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID). A packed column (GC Stainless Column 4.0 m × 3.0 mm I.D. Porapak Q 50/80, Shinwa Chemical Industries) was used with a column temperature of 40 °C, flow rate of 31 mL min− 1, detector temperature of 150 °C, and injection port temperature of 150 °C. Pure nitrogen was used as the carrier gas.

Results and discussion

Characterization of PtOx and PdOx

Figure 1a shows the X-ray diffraction patterns of the prepared PtOx-TiO2, PdOx-TiO2, and pristine TiO2. The peak at 25.3° for TiO2 corresponds to the (101) plane of the anatase phase, whereas the peak at 37.8° is assigned to the (103), (004), and (112) planes of the anatase phase. Additionally, the peak at 47.9° corresponds to the (200) plane of the anatase phase64,65. The peak at 54.7° was associated with the (105) and (211) planes of the anatase phase and the (211) plane of the rutile phase64,65. Since these peaks were similarly observed in PtOx- and PdOx-loaded TiO2, no significant changes were observed in the X-ray diffraction patterns of TiO2 due to PtOx and PdOx loading.

(a) XRD patterns of the prepared photocatalysts (orange: PtOx-TiO2; purple: PdOx-TiO2; green: TiO2). (b) XPS spectrum of PtOx-TiO2 (Pt 4f orbital, orange: metallic Pt, blue: PtO). (c) XPS spectrum of PdOx-TiO2 (Pd 3d orbital, purple: metallic Pd, orange: PdO). (d) TEM image of the PtOx-TiO2 photocatalyst. (e) TEM image of the PdOx-TiO2 photocatalyst.

To analyze the chemical states of PtOx-TiO2 and PdOx-TiO2, XPS analysis was conducted. Figure 1b shows the XPS spectrum of the Pt 4f orbital in PtOx-TiO2, while Fig. 1c displays the corresponding Pd 3d orbital spectrum in PdOx-TiO2. In the Pt 4f spectrum, two main peaks (Pt 4f5/2 and Pt 4f7/2) are observed. The peaks at 72.1 eV and 75.0 eV are attributed to metallic Pt, while those at 73.1 eV and 76.1 eV correspond to PtO66. Similarly, the Pd 3d spectrum exhibits two main peaks (Pd 3d3/2 and Pd 3d5/2), with peaks at 338.9 eV and 345.6 eV attributed to metallic Pd, and peaks at 340.2 eV and 345.6 eV assigned to PdO67. These XPS results confirm the successful loading of both metallic and oxidized forms of Pt and Pd onto the TiO2 surface. These XPS results confirm the successful loading of both metallic and oxidized forms of Pt and Pd onto the TiO2 surface. However, the XPS spectrum suggested that the relative abundance of oxidized species (PtO, PdO) remained lower than that of the metallic species (Pt0, Pd0). The deposition of the oxides may derive from the partial oxidation of Pt0 or Pd0 by photogenerated holes (Eqs. 1 and 2) or dissolved oxygen (Eqs. 3 and 4):

Although these oxidation processes are thermodynamically possible, their occurrence is significantly suppressed due to the presence of 2-propanol as a hole scavenger, which minimizes the oxidation of Pt0 and Pd0 via the photodeposition. Consequently, the relative abundance of oxidized species (PtO, PdO) remains lower than that of metallic Pt and Pd in the final catalysts.

Figure S3 shows the H2-TPR profiles of the prepared PtOx-TiO2 and pristine TiO2. A peak was observed for PtOx-TiO2 at approximately 60–90 °C, which can be attributed to PtOx68. Figure S4 also shows the H2-TPR profiles of the prepared PdOx-TiO2 and TiO2. A peak was observed for PdOx-TiO2 at approximately 60–70 °C, which can originate from PdOx69.

TEM measurements were conducted to observe the average size and crystal structure of PtOx and PdOx nanoparticles loaded on TiO2. Figure 1d shows the TEM image of PtOx-TiO2. The TEM image revealed that Pt nanoparticles with an average diameter of approximately 3 nm were attached to the surface of the TiO2 particles. The measurement of the lattice fringe spacings confirmed periodic structures of 0.189 nm and 0.227 nm, which correspond to the (200) plane of TiO2 and the (111) plane of Pt, respectively. Similarly, Fig. 1e shows the TEM image of PdOx-TiO2, which revealed that Pd nanoparticles with an average diameter of approximately 4 nm were attached to the surface of the TiO2 particles. The lattice fringe spacings of 0.191 and 0.225 nm correspond to the (200) plane of TiO2 and the (111) plane of Pd, respectively. Notably, the lattice fringes attributed to PtO and PdO were not observed in either case. These observations suggest that the loading amounts of PtO and PdO were lower than their respective metallic forms, which is consistent with the XPS results.

Figure S5 and S6 shows the PtOx and PdOx particle size distributions for PtOx-TiO2 and PdOx-TiO2, respectively. The mean particle size of the PtOx particles was determined to be 3.38 ± 0.71 nm. Particles with a diameter of 2 nm accounted for 4.2% of the total, while those of 3 nm, 4 nm, and 5 nm represented 62.5%, 25.0%, and 8.3%, respectively. No particles with a diameter of 1 nm were observed. The mean particle size of the PdOx particles was determined to be 3.86 ± 0.47 nm. Particles with a diameter of 3 nm accounted for 16.7% of the total, while those of 4 nm, and 5 nm represented 70.8%, and 4.2%, respectively. No particles with a diameter of 1 nm and 2 nm were observed.

STEM measurements were conducted to observe photo-induced changes in the oxidation state of PtOx particles in PtOx-TiO2 during the glucose decomposition reaction. STEM images of PtOx-TiO2 before and after 6 h of light irradiation are shown in Figures S7 and S8, respectively. The bright spots in Figure S7 and the dark spots in Figure S8 are both attributed to PtOx particles. These observations indicate that the PtOx particles changed from bright to dark during light irradiation. This contrast change may be attributed to the oxidation of Pt to PtO during light irradiation, or to the coverage of the particles by glucose and its degradation byproducts.

Figure S9 shows the UV-vis spectra of PtOx-TiO2, PdOx-TiO2, and bare TiO2. In the wavelength range of 400–800 nm, both PtOx-TiO2 and PdOx-TiO2 exhibit higher apparent absorption than bare TiO2. Although a localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) of Pt or Pd has been reported around 410 nm70, our spectra do not show a distinct, narrow plasmon band; instead, the enhancement is broad across the visible region. Considering that TEM reveals sub-10 nm particles for PdOx-TiO2 in this study (Fig. 1e) and that Pd particles below 10 nm typically exhibit only UV features71, together with the presence of both metallic and oxidized states of Pt and Pd confirmed by XPS (Fig. 1b, c), it is likely that partial oxidation of Pt and Pd dampens the plasmonic response. Therefore, while some contribution from LSPR cannot be completely excluded, it is not considered the dominant origin of the enhanced visible absorption. Instead, the increased visible absorption is attributed to a combination of (i) interfacial charge-transfer transitions between supported PtOx or PdOx species and TiO2, (ii) defect-related sub-band-gap absorption arising from Ti3+ centers and oxygen vacancies generated during photodeposition, (iii) enhanced light scattering by supported nanoparticles that increases the effective optical path length in diffuse-reflectance measurements, and (iv) the intrinsic visible-light absorption of PtO and PdO72,73. These factors collectively account for the broadband enhancement observed for both PtOx-TiO2 and PdOx-TiO2.

Glucose conversion and products analyses

Figure 2a shows the glucose decomposition rates using the prepared PtOx-TiO2 and PdOx-TiO2, as well as control experiments using TiO2 alone, and without the photocatalyst. The glucose decomposition rate was calculated using the formula (Glc0-Glc6)/Glc0 × 100, where Glc0 represents the glucose concentration before light irradiation and Glc6 represents the glucose concentration after 6 h of light irradiation. The glucose decomposition rates were 13.36% for PtOx-TiO2, 7.83% for PdOx-TiO2, 7.70% for TiO2, and 0.44% for the case without photocatalyst. The glucose decomposition rate was improved by PtOx loading compared to that of TiO2, whereas no significant difference was observed between PdOx-TiO2 and TiO2.

(a) Decomposition rate of glucose after 6 h of the experiment (n = 3, *: p < 0.05, orange: PtOx-TiO2, purple: PdOx-TiO2, green: TiO2, red: No photocatalyst). (b) Changes in CH4 concentration (n = 3, orange: PtOx-TiO2, purple: PdOx-TiO2, green: TiO2, red: no photocatalyst). (c) Time course of CH4 concentration using PtOx-TiO2 with different PtOx loading rates on TiO2 (n = 3, *: p < 0.05, orange: 0.5 wt%, green: 1.0 wt%, blue: 2.0 wt%, purple: 4.0 wt%). Time course of (d) CO2, and (e) H2 concentration (n = 3, *: p < 0.05, orange: PtOx-TiO2, purple: PdOx-TiO2, green: TiO2, red: No photocatalyst).

Figure 2b shows the changes in CH4 concentration when using PtOx-TiO2, PdOx-TiO2, TiO2, and without the photocatalyst. In the case of PtOx-TiO2, CH4 was generated at 3.691 µmol L− 1 after 3 h, and the concentration was approximately the same at 3.748 µmol L− 1 after 6 h. In contrast, with PdOx-TiO2, CH4 concentration was minimal at 0.456 µmol L− 1 after 3 h and 0.349 µmol L− 1 after 6 h. CH4 concentration was not detected when TiO2 was used alone or without a photocatalyst.

PtOx-TiO2 showed significant CH4 generation compared to PdOx-TiO2 and pristine TiO2. Therefore, the effect of PtOx loading ratio on TiO2 was investigated to identify the optimal photocatalytic conditions for CH4 generation from glucose. Figure 2c shows the changes in CH4 concentration when using PtOx-TiO2 with different loading ratios was used. In the system using PtOx-TiO2, the CH4 generation after 6 h of light irradiation was 3.748 µmol L− 1 when the PtOx loading ratio on TiO2 was 0.5 wt%, 5.732 µmol L− 1 at 1.0 wt%, 10.600 µmol L− 1 at 2.0 wt%, and 6.696 µmol L− 1 at 4.0 wt%. These results revealed that maximum CH4 concentration was achieved when using PtOx-TiO2 with a loading ratio of 2.0 wt%.

STEM measurements were conducted to clarify the underling mechanism that the CH4 production rate peaked at 2.0 wt% PtOx loading but declined at 4.0 wt%. Figures S10 and S11 show the STEM images of 2.0 wt% PtOx-TiO2 and 4.0 wt% PtOx-TiO2, respectively. In the 2.0 wt% loading system, uniformly sized PtOx nanoparticles with an average diameter of approximately 7 nm were observed to be dispersed on the TiO2 surface. On the other hand, in the 4.0 wt% loading system, aggregated PtOx particles (average size: 15 nm) were observed, indicating a significant deterioration in dispersion.

The decline in photocatalytic activity at these loading rates can be attributed to two possible factors: (i) the reduction of the active site accessibility and light-harvesting efficiency and (ii) the decrease in the metal-semiconductor interfacial area due to nanoparticle aggregation. To assess the contribution of the decreased accessible active sites to the overall photocatalytic performance, the accessible active site density of 2.0 wt% PtOx-TiO2 and 4.0 wt% PtOx-TiO2 was calculated as follows. The accessible active site density for 2.0 wt% PtOx-TiO2 and 4.0 wt% PtOx-TiO2 was estimated according to the following procedure. First, the specific surface area of TiO2 (P25, Evonik) used in this study was determined to be 49.2 m2 g− 1 by BET method. Therefore, the theoretical total surface area of TiO2 weighing x g can be calculated as 4.92 × 105x cm2. In the case of 2.0 wt% PtOx-TiO2, x g of TiO2 theoretically supports 0.02x g of PtOx, while 4.0 wt% PtOx-TiO2 supports 0.04x g of PtOx. STEM analysis (Figures S10 and S11) revealed that the average diameters of PtOx particles in the 2.0 wt% and 4.0 wt% loading samples were approximately 7 nm and 15 nm, respectively. Assuming that each PtOx particle is a perfect sphere, the corresponding particle volumes were calculated to be 5.72π × 10− 20 cm3 for 2.0 wt% and 5.63π × 10− 19 cm3 for 4.0 wt%. For simplicity, if the PtOx particles are considered to consist entirely of metallic Pt with a density of 21.45 g cm− 3, the mass of a single particle can be estimated as 1.23π × 10− 18 g and 1.21π × 10− 17 g for the 2.0 wt% and 4.0 wt% systems, respectively. Based on these values, the total number of particles corresponding to 0.02x g and 0.04x g of Pt loading can be derived. Treating the photocatalyst as a flat surface, each PtOx particle was approximated as a circle, with a projected area of 1.23π × 10− 13 cm2 for 2.0 wt% and 5.63π × 10− 13 cm2 for 4.0 wt%. Consequently, the theoretical total surface area of PtOx particles was estimated to be 2.00 × 103x cm2 for the 2.0 wt% sample and 1.86 × 103x cm2 for the 4.0 wt% sample. From these results, the theoretical accessible active site densities were calculated to be 99.59% and 99.62% for the 2.0 wt% and 4.0 wt% systems, respectively, as shown in Eqs. 5 and 6.

These calculations indicate that the accessible active site density was slightly higher in the 4.0 wt% PtOx loading system. Thus, the observed difference in photocatalytic activity between the two samples is unlikely to result from variations in light-shielding by the PtOx nanoparticles. Instead, it is more likely attributable to a reduction in the effective metal-semiconductor interfacial area caused by nanoparticle aggregation.

Figure 2d and e show the photocatalytic generation of CO2 and H2 from aqueous glucose solutions using PtOx-TiO2, PdOx-TiO2, and TiO2 as photocatalysts, compared to light irradiation without photocatalyst addition. For CO2 generation, the concentration after 6 h of light irradiation was 971 µmol L− 1 for PtOx-TiO2, 620 µmol L− 1 for PdOx-TiO2, and 391 µmol L− 1 for TiO2. In contrast, glucose photolysis without a photocatalyst produced only 0.110 µmol L− 1 of CO2. The CO2 generation performance followed the order PtOx-TiO2 > PdOx-TiO2 > TiO2. For H2 generation, the concentration after 6 h of light irradiation reached 3874 µmol L− 1 for PdOx-TiO2, 2365 µmol L− 1 for PtOx-TiO2, and 15.3 µmol L− 1 for TiO2. No H2 generation was observed without the photocatalyst. The H2 generation performance demonstrated the order PdOx-TiO2 > PtOx-TiO2 > TiO2.

These results reveal distinct catalytic selectivity patterns among the photocatalysts. While PtOx-TiO2 exhibited superior CO2 generation efficiency, PdOx-TiO2 demonstrated the highest H2 production capability. Both metal co-catalyst modified TiO2 significantly outperformed pure TiO2 for both products, confirming the enhancement effect of the metal co-catalysts on the photocatalytic glucose conversion process.

It has been reported that photocatalytic decomposition of glucose produces sugars74. The analysis of these sugar products is important for understanding the reaction pathways.

Figure 3a shows the HPLC chromatograms of the sugar products contained in the solution after glucose decomposition for 6 h using photocatalysts PtOx-TiO2, PdOx-TiO2, and TiO2, as well as the results from a control experiment involving glucose decomposition under light irradiation alone without photocatalysts. Sugars contained in each sample were identified by comparing the retention times (R.T.) of sugar standard samples after ABEE labeling. The R.T. of standard substances were approximately 21.4 min for arabinose, 25.8 min for erythrose, and 38.8 min for glyceraldehyde, respectively. Based on a comparison with the R.T. of standard substances, peaks corresponding to arabinose, erythrose, and glyceraldehyde were clearly detected in all photocatalytic systems using PtOx-TiO2, PdOx-TiO2, and TiO2, confirming the formation of these sugar compounds. In contrast, in the photolysis of glucose alone without photocatalysts, only the formation of arabinose was detected, and its peak was confirmed in the chromatogram, while the peaks of erythrose and glyceraldehyde were below the detection limit.

(a) HPLC chromatograms of sugar products and standards of arabinose, erythrose and glyceraldehyde. Concentration of (b) arabinose, (c) erythrose, and (d) glyceraldehyde in the products (n = 3, *: p < 0.05). (e) HPLC chromatograms of organic acid products and standards of gluconic acid, acetic acid and formic acid. (f) Concentration of formic acid in the products. All products obtained from glucose decomposition after 6 h of light irradiation using PtOx-TiO2 (orange), PdOx-TiO2 (purple), and TiO2 (green), no photocatalyst (red).

Figures 3b-d present the concentrations of sugar products in the reaction solution after 6 h of photocatalytic glucose decomposition. Arabinose concentrations (Fig. 3b) were 1401 µmol L− 1 for PtOx-TiO2, 968 µmol L− 1 for PdOx-TiO2, 556 µmol L− 1 for TiO2, and 19 µmol L− 1 for glucose decomposition without photocatalyst. Erythrose concentrations (Fig. 3c) were 119 µmol L− 1 for PtOx-TiO2, 93 µmol L− 1 for PdOx-TiO2 and 30 µmol L− 1 for TiO2. Glyceraldehyde concentrations (Fig. 3d) were 106 µmol L− 1 for PtOx-TiO2, 72 µmol L− 1 for PdOx-TiO2, and 27 µmol L− 1 for TiO2. The concentration of all three sugar products decreased in the order of PtOx-TiO2 > PdOx-TiO2 > TiO2, confirming that metal co-catalyst loading significantly enhanced sugar formation from glucose decomposition, and PtOx-TiO2 exhibited the highest glucose decomposition rate and the maximum production amounts for all sugar compounds. This result suggests that the PtOx loading promotes the photocatalytic reaction. On the other hand, although PdOx loading did not cause significant improvement in the glucose decomposition rate itself, the production amounts of arabinose, erythrose, and glyceraldehyde were clearly improved. This indicates that PdOx-TiO2 possesses a specific reaction selectivity. Thus, PdOx loading guided the photocatalytic activity of TiO2 to specific reaction pathways, thereby promoting the conversion of glucose to these sugar compounds.

Organic acids are generated during the photocatalytic degradation of glucose. Figure 3e shows HPLC chromatograms of organic acids in glucose degradation sample using PtOx-TiO2, PdOx-TiO2, and TiO2, as well as in glucose degradation without a photocatalyst, under light irradiation. The R.T. of standards were approximately 11.9 min for gluconic acid, approximately 16.9 min for formic acid, and approximately 18.8 min for acetic acid, respectively. By comparing the retention times of reaction products with those of standard compounds, the formation of gluconic acid, formic acid, and acetic acid was confirmed in all photocatalytic systems. Furthermore, the formation of these acids was also confirmed in the glucose degradation without photocatalyst.

Figure 3f shows a comparison of the formic acid concentrations produced by the different photocatalysts. The formic acid concentrations were 2691 µmol L− 1 for PtOx-TiO2, 2775 µmol L− 1 for PdOx-TiO2, 881 µmol L− 1 for TiO2, and 63 µmol L− 1 in the absence of photocatalyst. No significant difference was observed between the formic acid concentrations of PtOx-TiO2 and PdOx-TiO2.

Based on the aforementioned results, it was demonstrated that the metal co-catalysts loading onto TiO2 contributed significantly to the enhancement of formic acid production. Notably, the observation that PdOx-TiO2 exhibited the highest formic acid concentration suggests that the formic acid generation pathway proceeds preferentially in PdOx-loaded systems. Conversely, for sugar production (arabinose, erythrose, glyceraldehyde), PtOx-TiO2 demonstrated the highest production. Initially, it was anticipated that the superior oxidative capability of PtOx-TiO2 would confer advantages in formic acid generation as well, however, the experimental findings deviated from this expectation. This phenomenon is attributed to the efficient secondary oxidation of formic acid within the PtOx-TiO2 system. Specifically, it is postulated that the subsequent oxidative conversion of generated formic acid to CO2 is substantially enhanced in PtOx-TiO2 systems. This hypothesis is corroborated by the maximum CO2 production observed in the PtOx-TiO2 system, demonstrating internal consistency with the proposed mechanism.

Table S1 represents the carbon balance after 6 h of light irradiation. The carbon balance of each carbon-containing compound with a known production amount was calculated, and an approximate total carbon value was obtained by summing these values. The carbon balances were 94.69% for PtOx-TiO2, 98.52% for PdOx-TiO2, 95.18% for TiO2, and 99.69% for the case without photocatalyst. All of these values were close to 100% and the remaining fraction, less than 100%, is considered to be composed of other organic compounds that were not quantified in this study.

Discussion of mechanism of CH4 generation

Glucose addition is essential for CH4 generation, as demonstrated by a control experiment without glucose. Figure S12 shows the CH4 concentrations with and without glucose addition. After 6 h of light irradiation, the CH4 concentration for glucose solution decomposition was 3.748 µmol L− 1, whereas only 0.240 µmol L− 1 was observed in the absence of glucose. The significantly reduced CH4 production without glucose compared to that with glucose solution decomposition confirms that glucose introduction is essential for efficient CH4 generation.

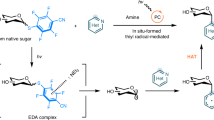

The photocatalytic degradation of glucose produced CO2 and H2, sugars such as arabinose, erythrose, and glyceraldehyde, and organic acids including formic acid, acetic acid, and gluconic acid. The presumed reaction pathways for glucose degradation based on these results are shown in Fig. 4a. The photocatalytic degradation of glucose proceeds via several distinct reaction pathways. The first reaction pathway involves gluconic acid as an intermediate. Initially, glucose is oxidized to produce gluconic acid, which then undergoes decarboxylation to generate arabinose75. During the decarboxylation of gluconic acid, CO2 and H+ are formed as byproducts75. The second reaction pathway involves direct generation of arabinose through C1-C2 bond cleavage of glucose. The third reaction pathway encompasses erythrose formation through C2-C3 bond cleavage of glucose, as well as glyceraldehyde formation through C3-C4 bond cleavage of glucose. The arabinose generated in the first and second pathways proceeds through sequential reactions, wherein formic acid elimination produces erythrose, and further formic acid elimination from erythrose produces glyceraldehyde. During these sequential elimination reactions, H2 is formed as a byproduct75. Subsequently, the oxidation of glyceraldehyde leads to acetic acid formation, and when complete oxidation of glyceraldehyde occurs, CO2 is ultimately generated. Thus, the photocatalytic degradation of glucose produces sugars, organic acids, and H2, while simultaneously generating CO2 and H+.

The preceding experiments elucidated the production pathways of sugars, organic acids, CO2 and H+ during photocatalytic glucose decomposition; however, the generation mechanisms underlying CH4 formation remain insufficiently characterized. Consequently, based on accumulated experimental evidence, we examined the mechanisms governing CH4 generation during glucose decomposition using metal co-catalyst-loaded TiO2 photocatalysts (Fig. 4b). Upon photoirradiation, the holes generated within the valence band of TiO2 reacted with water molecules to form hydroxyl radicals as reactive oxygen species. Concurrently, the photoexcited electrons generated in the conduction band interact with molecular oxygen to produce superoxide anion radicals, which are also reactive oxygen species. These photogenerated holes and reactive oxygen species facilitate glucose oxidation, ultimately yielding CO2 and H+ through sequential intermediates comprising sugars and organic acids. Furthermore, H+ is concomitantly generated along with hydroxyl radicals during water oxidation. The resultant H+ ions undergo reduction by photoexcited electrons in the conduction band, thereby forming H2. Subsequently, the CO2 and H+ species produced through these photocatalytic processes are anticipated to undergo methanation reactions at the metal co-catalyst surface, culminating in CH4 formation.

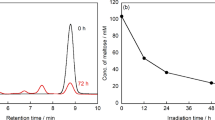

To verify whether CH4 generation proceeds via the proposed methanation mechanism, we conducted controlled experiments under photoirradiation conditions using CO2 as the sole carbon source instead of glucose. The experimental protocol involved the addition of 20 mL of ultrapure water and 20 mg of photocatalyst to a sealed reaction vessel equipped with a septum-fitted lid for gas sampling. Subsequently, CO2 was introduced into the solution by bubbling for 30 min to achieve saturation, followed by UV irradiation of the reaction system. Gas-phase samples were collected prior to photoirradiation and at 3 h and 6 h intervals following irradiation initiation. Quantitative CH4 analysis was performed using GC. The experimental results are presented in Fig. 4c. CH4 generation was observed following photoirradiation initiation, with production quantities after 6 h measuring 9.875 µmol L− 1 for PtOx-TiO2, 4.784 µmol L− 1 for PdOx-TiO2, and 0.525 µmol L− 1 for pristine TiO2. Confirmation of CH4 generation in the absence of added glucose conclusively demonstrates that methanation reactions occur between photocatalytically generated H+ and dissolved CO2, thereby establishing a mechanistic pathway for CH4 production.

A control experiment under dark conditions was conducted to confirm that the observed CH4 generation depends on photocatalytic reactions, specifically demonstrating that CH4 is not produced in the absence of light irradiation, even when CO2 is present in the environment. To maintain the experimental conditions as similar as possible to those under light irradiation, glucose at 25 mmol L− 1 was dissolved in 20 mL of ultrapure water, although glucose was not required for this particular reaction. Subsequently, 20 mg of photocatalyst was added to the reaction vessel. The reaction vessel was sealed using a lid equipped with a septum for gas sampling. Pure hydrogen (99.99%) and pure CO2 (99.9%) were added to 50 µL of the reaction substrate, and the reaction was conducted under dark conditions without light irradiation. Gas samples (1.0 mL) were collected from the gas phase of the reaction vessel before substrate addition, 3 h after addition, and 6 h after addition, followed by the quantitative analysis of CH4 using gas chromatography. As shown in Figure S13, CH4 generation was below the detection limit under dark conditions when either PtOx-TiO2 or PdOx-TiO2 was used. These results clearly demonstrate that the CH4 generation observed in this study was induced by photocatalytic processes.

To identify the sources of hydrogen atoms that constitute CH4 molecules with the aim of elucidating the detailed mechanism of CH4 generation through photocatalytic reactions, deuterium-labeling experiments were conducted. Specifically, 20 mL of D2O containing 25 mmol L− 1 glucose and 20 mg of PtOx-TiO2 were added to a closed reaction vessel and irradiated with UV light (light irradiation intensity: 50 mW cm− 2). Gas generated in the reaction system was sampled 6 h after the start of light irradiation, and molecular weight analysis was performed using GC-MS. The analysis results are shown in Fig. 4d. methane corresponding to molecular weights of 16 (CH4), 17 (CH3D), 18 (CH2D2), 19 (CHD3), and 20 (CD4) was detected, with R.T. of 4.52 min, 4.50 min, 4.41 min, 4.44 min, and 4.41 min, respectively. The detection of chemical species in which hydrogen atoms in CH4 molecules were substituted with deuterium (CH3D, CH2D2, CHD3, and CD4) confirmed that the D+ involved in methane generation was supplied by D2O. Meanwhile, the detection of unlabeled CH4 suggests that hydrogen species were also supplied by the glucose molecules themselves. These results reveal that the sources of H+ in the photocatalytic glucose decomposition originate from both water and glucose.

(a) Presumable reaction pathways for the photocatalytic decomposition of glucose. (b) Schematic illustration of CH4 production through glucose decomposition using metal co-catalyst-loaded TiO2. (c) CH4 production using CO2 as the starting material (n = 3, orange: PtOx-TiO2, purple: PdOx-TiO2, green: TiO2). (d) Mass spectra of CH4 generated through photocatalytic degradation of glucose in D2O solution (black: TIC, red: m/z 16, blue: m/z 17, orange: m/z 18, purple: m/z 19, green: m/z 20).

In Fig. 2b, PtOx-TiO2 reached a plateau after 3 h of light irradiation. On the other hand, when CO2 solution was used as the starting material, the CH4 production on PtOx-TiO2 (Fig. 4c) increased continuously, rather than plateauing. Specifically, the CH4 concentration was approximately 4.357 µmol L− 1 during the first 3 h of UV irradiation and further increased to 5.444 µmol L− 1 between 3 and 6 h. This behavior may be attributed to differences in the availability of CO2, which serves as the carbon source for CH4 formation. Figure S14 shows the temporal profiles of CO2 concentrations for reactions starting from CO2 and from glucose, on PtOx-TiO2. In the case of glucose decomposition with PtOx-TiO2, the CO2 concentration increased to approximately 599 µmol L− 1 during the first 3 h of irradiation but decreased to 350 µmol L− 1 between 3 and 6 h. In contrast, for CO2 conversion using PtOx-TiO2, the CO2 concentration in the reactor was approximately 21,150 µmol L− 1 before irradiation, 19,186 µmol L− 1 at 3 h, and 19,403 µmol L− 1 at 6 h, indicating that sufficient CO2 was available compared with the glucose decomposition case. These results suggest that, in CH4 production from glucose decomposition using PtOx-TiO2, the platoo observed in CH4 formation after 3 h of irradiation can be partly attributed to insufficient CO2 supply for the methanation. In addition, in this study, it was also possible that the decomposition reaction of the CH4 occurred on PtOx-TiO2 systems76, which suggested that the generation and degradation rates of CH4 might have become comparable after 3 h of light irradiation.

Table S2 represents a comparison between this work and previous studies regarding CH4 yields in photocatalytic degradation of glucose. In CH4 production via photocatalytic degradation of glucose, previous studies have shown that Pd loading effectively promotes CH4 production62. However, this work demonstrated the CH4 production with not only PdOx but also that the PtOx loading systems and exhibited that PtOx-TiO2 showed CH4 yields ca. ten times higher than those of the PdOx-TiO2. Furthermore, this work suggested that methane is ultimately produced via the methanation of CO2, produced via decomposition of glucose, and H+, derived from both glucose and water, which was not clarified in previous studies.

The significant difference in CH4 generation between PtOx-TiO2 and PdOx-TiO2 observed in this study originates from the fundamental differences in the electronic and chemical properties of the Pt and Pd species. This difference in performance can be explained by two factors. The first is the utilization efficiency of electrons, which serves as the driving force for photocatalytic reactions. PL measurements were conducted to investigate the suppression ability of carrier recombination in the prepared photocatalysts. Figure S15 shows the PL spectra of PtOx-TiO2, PdOx-TiO2, and bare TiO2. It was found that the PL intensity was the highest for bare TiO2, followed by PtOx-TiO2, and the lowest for PdOx-TiO2. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was conducted to further investigate in detail the suppression of carrier recombination by the supported metals. Figure S16 shows the Nyquist plots of PtOx-TiO2, PdOx-TiO2, and bare TiO2 under light irradiation, obtained from electrochemical impedance measurements. All photocatalysts exhibited Nyquist plots with a compressed semicircular feature within the measured range, corresponding to high- and mid-frequency domains that reflect charge-transfer processes at the photocatalyst–electrolyte interface. The semicircle radii decreased in the order of TiO2 > PdOx-TiO2 > PtOx-TiO2. The equivalent circuit used for fitting is shown in the upper-left corner of Figure S16. Rₛr represents the solution resistance, corresponding to the distance between the origin and the first point in the plot. The constant phase element (CPE) represents a pseudo-capacitance associated with the curvature of the semicircle, while Rₜr denotes the charge-transfer resistance between the photocatalyst and the electrolyte, which corresponds to the semicircle radius77. Among the samples, PtOx-TiO2 exhibited the smallest semicircle radius, indicating the lowest charge-transfer resistance and hence the most efficient interfacial charge transfer, followed by PdOx-TiO2 and bare TiO2. These results confirm that PtOx loading effectively suppresses electron-hole recombination by promoting charge separation and interfacial transport. Since Pt possesses a larger work function than Pd78, it functions as a more powerful electron trap site at the interface with TiO2 and efficiently captures photoexcited electrons. This superior charge separation efficiency provided abundant electrons available for reduction reactions on the Pt co-catalyst surface, thereby improving the overall efficiency of the methanation reaction. The second factor is the reaction selectivity of the co-catalyst surface. CH4 generation requires the cleavage of stable C-O bonds in CO2, which is a reaction with a high-energy barrier60. According to d-band center theory, Pt has a higher d-band center than Pd and can more strongly adsorb and activate CO2 and its reaction intermediates79. This strong interaction promotes the cleavage of the carbon-oxygen bonds, which is the rate-determining step of methanation. In contrast, the relatively weak adsorption capability of Pd makes carbon-oxygen bond cleavage difficult, causing electrons to be preferentially consumed in the competing hydrogen evolution reaction, which proceeds more readily. This is consistent with the experimental results showing that the PdOx-TiO2 system generated more H2 than the PtOx-TiO2 system. In conclusion, the synergistic effect of the superior electron-capture capability of Pt and its inherently high selectivity toward methanation reactions creates an advantage in CH4 generation over Pd.

Conclusions

This study successfully demonstrated sustainable CH4 production through photocatalytic glucose degradation under ambient conditions. Mechanistic investigations revealed that photocatalytic glucose degradation proceeds via complex reaction pathways involving intermediate sugars and organic acids. These compounds undergo further oxidation to generate CO2 and H+. CH4 formation occurs primarily through the methanation of internally produced CO2 and H+, which are reduced on the metal co-catalyst surface by photoexcited electrons. This mechanism was validated through control experiments, including CH4 production from CO2-saturated solutions under irradiation, and confirming that no CH4 generation occurs under dark conditions. The theoretical potential of glucose as a carbon source, which yields up to six CH4 molecules per glucose molecule, highlights the efficiency of this photocatalytic approach. Although current conversion rates require optimization for practical implementation, this research establishes the fundamental feasibility of photocatalytic biomass-to-fuel conversion under mild conditions.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Priyadharsini, P. et al. Genetic improvement of microalgae for enhanced carbon dioxide sequestration and enriched biomass productivity: review on CO2 bio-fixation pathways modifications. Algal Res. 66, 102810 (2022).

Wei, R., Meng, K., Long, H. & Xu, C. Biomass metallurgy: A sustainable and green path to a carbon-neutral metallurgical industry. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 199, 114475 (2024).

Freitas, E. N. et al. Challenges of biomass utilization for bioenergy in a climate change scenario. Biology 10, 1277 (2021).

Vijay, V., Kapoor, R., Singh, P., Hiloidhari, M. & Ghosh, P. Sustainable utilization of biomass resources for decentralized energy generation and climate change mitigation: A regional case study in India. Environ. Res. 212, 113257 (2022).

Rathore, A. S. & Singh, A. Biomass to fuels and chemicals: A review of enabling processes and technologies. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 97, 597–607 (2022).

Awasthi, M. K. et al. A comprehensive review on thermochemical, and biochemical conversion methods of lignocellulosic biomass into valuable end product. Fuel 342, 127790 (2023).

Babu, S. et al. Exploring agricultural waste biomass for energy, food and feed production and pollution mitigation: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 360, 127566 (2022).

Piercy, E. et al. A sustainable waste-to-protein system to maximise waste resource utilisation for developing food-and feed-grade protein solutions. Green. Chem. 25, 808–832 (2023).

Illankoon, W. et al. Evaluating sustainable options for valorization of rice by-products in Sri lanka: an approach for a circular business model. Agronomy 13, 803 (2023).

Kans, M. & Löfving, M. Unlocking the circular potential: A review and research agenda for remanufacturing in the European wood products industry. Heliyon (2024).

Wang, Y. & Wu, J. J. Thermochemical conversion of biomass: potential future prospects. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 187, 113754 (2023).

Gupta, N., Mahur, B. K., Izrayeel, A. M. D., Ahuja, A. & Rastogi, V. K. Biomass conversion of agricultural waste residues for different applications: a comprehensive review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29, 73622–73647 (2022).

Jha, S., Okolie, J. A., Nanda, S. & Dalai A. K. A review of biomass resources and thermochemical conversion technologies. Chem. Eng. Technol. 45, 791–799 (2022).

Zhou, Y. et al. Hydrothermal conversion of biomass to fuels, chemicals and materials: A review holistically connecting product properties and marketable applications. Sci. Total Environ. 886, 163920 (2023).

Deng, W. et al. Catalytic conversion of lignocellulosic biomass into chemicals and fuels. Green Energy Environ. 8, 10–114 (2023).

Ye, H. et al. Research progress of nano-catalysts in the catalytic conversion of biomass to biofuels: synthesis and application. Fuel 356, 129594 (2024).

Malik, K. et al. Lignocellulosic biomass for bioethanol: insight into the advanced pretreatment and fermentation approaches. Ind. Crops Prod. 188, 115569 (2022).

Alawad, I. & Ibrahim, H. Pretreatment of agricultural lignocellulosic biomass for fermentable sugar: opportunities, challenges, and future trends. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 14, 6155–6183 (2024).

Sant’Ana Júnior, D. B., Kelbert, M., Hermes de Araújo, P. H. & de Andrade, C. J. Physical pretreatments of lignocellulosic biomass for fermentable sugar production. Sustain. Chem. 6, 13 (2025).

Chen, Y. et al. Sustainable production of formic acid and acetic acid from biomass. Mol. Catal. 545, 113199 (2023).

Banerjee, N. Biomass to energy—an analysis of current technologies, prospects, and challenges. BioEnergy Res. 16, 683–716 (2023).

Caballero, J. J. B., Zaini, I. N. & Yang, W. Reforming processes for Syngas production: A mini-review on the current status, challenges, and prospects for biomass conversion to fuels. Appl. Energy Combust. Sci. 10, 100064 (2022).

Buffi, M., Prussi, M. & Scarlat, N. Energy and environmental assessment of hydrogen from biomass sources: challenges and perspectives. Biomass Bioenergy 165, 106556 (2022).

Zhang, L., Choo, S. R., Kong, X. Y. & Loh, T. P. From biomass to fuel: advancing biomass upcycling through photocatalytic innovation. Mater. Today Chem. 38, 102091 (2024).

Liu, X. et al. Heterogeneous photocatalytic conversion of biomass to biofuels: A review. Chem. Eng. J. 476, 146794 (2023).

Nakata, K. & Fujishima, A. TiO2 photocatalysis: design and applications. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev. 13, 169–189 (2012).

Nakata, K., Ochiai, T., Murakami, T. & Fujishima, A. Photoenergy conversion with TiO2 photocatalysis: new materials and recent applications. Electrochim. Acta. 84, 103–111 (2012).

Speltini, A. et al. Sunlight-promoted photocatalytic hydrogen gas evolution from water-suspended cellulose: a systematic study. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 13, 1410–1419 (2014).

Wang, M., Liu, M., Lu, J. & Wang, F. Photo splitting of bio-polyols and sugars to methanol and Syngas. Nat. Commun. 11, 1083 (2020).

Di Paola, A., Bellardita, M., Megna, B., Parrino, F. & Palmisano, L. Photocatalytic oxidation of trans-ferulic acid to Vanillin on TiO2 and WO3-loaded TiO2 catalysts. Catal. Today. 252, 195–200 (2015).

Usuki, S. et al. Photocatalytic production and biological activity of D-arabino-1, 4-lactone from D-fructose. Sci. Rep. 15, 1708 (2025).

Shanmugam, G. 200 years of fossil fuels and climate change (1900–2100). J. Geol. Soc. India. 99, 1043–1062 (2023).

Kanwal, S. et al. An integrated future approach for the energy security of pakistan: replacement of fossil fuels with Syngas for better environment and socio-economic development. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 156, 111978 (2022).

Arutyunov, V., Savchenko, V., Sedov, I., Arutyunov, A. & Nikitin, A. The fuel of our future: hydrogen or methane? Methane 1, 96–106 (2022).

Li, Q., Ouyang, Y., Li, H., Wang, L. & Zeng, J. Photocatalytic conversion of methane: recent advancements and prospects. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. 134, e202108069 (2022).

Li, R. et al. Recent advances in the conversion of methane to Syngas and chemicals via photocatalysis. ChemPhotoChem 8, e202300240 (2024).

Liu, J. et al. From fundamentals to chemical engineering on oxidative coupling of methane for ethylene production: A review. Carbon Resour. Convers. 5, 1–14 (2022).

Srivastava, R. K., Sarangi, P. K., Bhatia, L. & Singh, A. K. Shadangi, K. P. Conversion of methane to methanol: technologies and future challenges. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 12, 1851–1875 (2022).

Govindarajan, S. K., Ansari, M. I., Pavan, T. N. V. & Kumar, A. Field-scale complexities associated with production of CH4 from coal bed methane reservoir. Discov. Appl. Sci. 7, 184 (2025).

Bi, Y. & Ju, Y. Review on cryogenic technologies for CO2 removal from natural gas. Front. Energy 16, 793–811 (2022).

Imtiaz, A. et al. Challenges, opportunities and future directions of membrane technology for natural gas purification: a critical review. Membranes 12, 646 (2022).

Xie, W. et al. Methane storage and purification of natural gas in Metal-Organic frameworks. ChemSusChem 18, e202401382 (2025).

Mathur, S. et al. Industrial decarbonization via natural gas: A critical and systematic review of developments, socio-technical systems and policy options. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 90, 102638 (2022).

Ediger, V. Ş. & Berk, I. Future availability of natural gas: can it support sustainable energy transition? Resour. Policy. 85, 103824 (2023).

Collet, P. et al. Techno-economic and life cycle assessment of methane production via biogas upgrading and power to gas technology. Appl. Energy 192, 282–295 (2017).

Adnan, A. I., Ong, M. Y., Nomanbhay, S., Chew, K. W. & Show, P. L. Technologies for biogas upgrading to biomethane: A review. Bioengineering 6, 92 (2019).

Wulf, C., Linßen, J. & Zapp, P. Review of power-to-gas projects in Europe. Energy Procedia. 155, 367–378 (2018).

Ardolino, F., Cardamone, G., Parrillo, F. & Arena, U. Biogas-to-biomethane upgrading: A comparative review and assessment in a life cycle perspective. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 139, 110588 (2021).

Daiyan, R., MacGill, I. & Amal, R. Opportunities and challenges for renewable power-to-X. ACS Energy Lett. 5, 3843–3847 (2020).

Tommasi, M., Degerli, S. N., Ramis, G. & Rossetti, I. Advancements in CO2 methanation: A comprehensive review of catalysis, reactor design and process optimization. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 201, 457–482 (2024).

Pham, C. Q. et al. Carbon dioxide methanation on heterogeneous catalysts: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 20, 3613–3630 (2022).

Li, L. et al. Research progress and reaction mechanism of CO2 methanation over Ni-based catalysts at low temperature: a review. Catalysts 12, 244 (2022).

Usman, M., Podila, S., Alamoudi, M. A. & Al-Zahrani, A. A. Current research status and future perspective of Ni-and Ru-Based catalysts for CO2 methanation. Catalysts 15, 203 (2025).

Kim, J. Ni catalysts for thermochemical CO2 methanation: A review. Coatings 14, 1322 (2024).

Ullah, S. et al. Recent trends in plasma-assisted CO2 methanation: a critical review of recent studies. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 43, 1335–1383 (2023).

Ren, Y. et al. Concentrated solar CO2 reduction in H2O vapour with > 1% energy conversion efficiency. Nat. Commun. 15, 4675 (2024).

Ren, Y. et al. Photothermal synergistic effect induces bimetallic Cooperation to modulate product selectivity of CO2 reduction on different CeO2 crystal facets. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. 136, e202410474 (2024).

Ren, Y. et al. Concentrated solar-driven catalytic CO2 Reduction: From Fundamental Research to Practical Applications. ChemSusChem 18, e202402485 (2025).

Ulmer, U. et al. Fundamentals and applications of photocatalytic CO2 methanation. Nat. Commun. 10, 3169 (2019).

Wang, P. et al. Recent advances and challenges in efficient selective photocatalytic CO2 methanation. Small 20, 2400700 (2024).

Iervolino, G. et al. Photocatalytic production of hydrogen and methane from glycerol reforming over Pt/TiO2–Nb2O5. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 46, 38678–38691 (2021).

Vaiano, V. et al. Simultaneous production of CH4 and H2 from photocatalytic reforming of glucose aqueous solution on sulfated Pd-TiO2 catalysts. Oil Gas Sci. Technol. 70, 891–902 (2015).

Wenderich, K. & Mul, G. Methods, mechanism, and applications of photodeposition in photocatalysis: a review. Chem. Rev. 116, 14587–14619 (2016).

Miao, L. et al. Preparation and characterization of polycrystalline anatase and rutile TiO2 thin films by Rf Magnetron sputtering. Appl. Surf. Sci. 212, 255–263 (2003).

Orendorz, A. et al. Phase transformation and particle growth in nanocrystalline anatase TiO2 films analyzed by X-ray diffraction and Raman spectroscopy. Surf. Sci. 601, 4390–4394 (2007).

Li, Q. et al. Effect of photocatalytic activity of CO oxidation on Pt/TiO2 by strong interaction between Pt and TiO2 under oxidizing atmosphere. J. Mol. Catal. Chem. 258, 83–88 (2006).

Veziroglu, S. et al. PdO nanoparticles decorated TiO2 film with enhanced photocatalytic and self-cleaning properties. Mater. Today Chem. 16, 100251 (2020).

Zhang, C., He, H. & Tanaka, K. -i. Catalytic performance and mechanism of a Pt/TiO2 catalyst for the oxidation of formaldehyde at room temperature. Appl. Catal. B. 65, 37–43 (2006).

Luo, M. F. & Zheng, X. M. Redox behaviour and catalytic properties of Ce0. 5Zr0. 5O2-supported palladium catalysts. Appl. Catal. A. 189, 15–21 (1999).

Zielińska-Jurek, A. & Hupka, J. Preparation and characterization of Pt/Pd-modified titanium dioxide nanoparticles for visible light irradiation. Catal. Today. 230, 181–187 (2014).

Leong, K. H., Chu, H. Y., Ibrahim, S. & Saravanan, P. Palladium nanoparticles anchored to anatase TiO2 for enhanced surface plasmon resonance-stimulated, visible-light-driven photocatalytic activity. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 6, 428–437 (2015).

Nguyen, P. A. et al. Highly dispersed PtO over g-C3N4 by specific metal-support interactions and optimally distributed Pt species to enhance hydrogen evolution rate of Pt/g-C3N4 photocatalysts. Chem. Eng. J. 464, 142765 (2023).

Cao, Y., Zhou, C., Chen, Y., Qin, H. & Hu, J. Enhanced CO sensing performances of PdO/WO3 determined by heterojunction structure under illumination. ACS Omega 5, 28784–28792 (2020).

Terada, C., Usuki, S. & Nakata, K. Synthesis of l-Rare sugars from d-Sorbitol using a TiO2 photocatalyst. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 11, 9030–9035 (2023).

Da Vià, L., Recchi, C., Davies, T. E. & Greeves, N. Lopez-Sanchez, J. A. Visible‐light‐controlled oxidation of glucose using titania‐supported silver photocatalysts. ChemCatChem 8, 3475–3483 (2016).

Yu, L., Shao, Y. & Li, D. Direct combination of hydrogen evolution from water and methane conversion in a photocatalytic system over Pt/TiO2. Appl. Catal. B. 204, 216–223 (2017).

Usuki, S. et al. Dual-function ZnO/CeO2 photocatalyst for simultaneous methane decomposition and CO2 adsorption at room temperature. Chem. Eng. J. 161408 (2025).

Gu, D., Dey, S. K. & Majhi, P. Effective work function of Pt, Pd, and Re on atomic layer deposited HfO2. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89 (2006).

Mancera, L. A., Groß, A. & Behm, R. J. Stability, electronic properties and CO adsorption properties of bimetallic PtAg/Pt (111) surfaces. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 26, 18435–18448 (2024).

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS Program for Forming Japan’s Peak Research Universities (J-PEAKS) Grant Number JPJS00420230003.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yuma Uesaka: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Data curation, Investigation. Kio Kawakatsu: Investigation, Methodology. Mana Akita: Investigation, Methodology. Toshiya Tsunakawa: Investigation, Methodology. Satoki Yoshida: Investigation. Naoko Taki: Investigation. Tiangao Jiang: Investigation. Shanhu Liu: Methodology. Eika W. Qian: Methodology. Sho Usuki: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Kazuya Nakata: Methodology, Conceptualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Uesaka, Y., Kawakatsu, K., Akita, M. et al. Methane production via photocatalytic degradation of glucose on PtOx and PdOx-loaded TiO2. Sci Rep 16, 721 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30321-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30321-w