Abstract

This study aims to assess the predictive ability of a radiomics nomogram incorporating clinical features and ultrasound radiomics signature in determining the presence of lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI) in endometrioid adenocarcinoma (EAC) before surgical intervention. This retrospective, single-center study included 171 patients diagnosed with EAC. Stratified random sampling was utilized to divide the data into a training group for model construction, and a test group for assessing the model’s reliability, with a ratio of 7:3. Ultrasound radiomics features were extracted from the ultrasound images. Then, the Z-score method and the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) were used to select significant features, and the ultrasound radiomics score (Rad-score) was constructed. A comprehensive prediction model was established based on the multivariate logistic regression analysis, and a nomogram was drawn. The model diagnostic performance was assessed via the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity on training and test sets. Model comparisons were performed using the Delong test. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses found that the independent risk factors of LVSI in EAC were preoperative histological grade and Rad-score. In the comprehensive prediction model, the AUC, sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy for the training set were 0.83 (95% CI: 0.76–0.91), 0.96, 0.64, and 0.71; for the test set, the values were 0.75 (95% CI: 0.57–0.93), 0.75, 0.70, and 0.71, respectively. The ultrasound radiomics and comprehensive prediction models showed good prediction efficiency, characterized by high sensitivity with moderate specificity for LVSI in EAC. In the preoperative evaluation of LVSI in EAC, the comprehensive prediction model can obtain high sensitivity with moderate specificity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Endometrial cancer (EC) is the most common gynecological malignancy in developed countries and the third most common female malignancy in China1, accounting for 2% of new cancer cases and 1% of deaths worldwide in 20202. In recent years, due to the increase in obesity and aging in the population, the incidence and mortality of endometrial cancer are increasing3. Endometrioid adenocarcinoma(EAC) is the primary subtype of EC, accounting for 75% to 80% of endometrial cancer cases4.

The lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI) is a crucial prognostic factor that impacts each patient’s recurrence risk and influences recommendations for adjuvant therapy5. One of the initial stages in the metastatic spread of EAC has been assumed as LVSI, which is pathologically defined as detecting tumoral cells in lymphatics or small vessels outside the core tumor6. The LVSI status of endometrial cancer is essential in guiding lymph node dissection. If LVSI is present in a uterine specimen, it is necessary to perform a staging lymphadenectomy to evaluate lymph node involvement7. According to the latest European Society of Gynecologic Oncology (ESGO) guidelines recommendations, lymph node excision can be performed if LVSI-positive status is present, even in the absence of other histological risk factors8. Fariba et al.9reported that the presence of LVSI in early-stage endometrial cancer has a significant and independent impact on 3-year and 5-year survival rates. Karin et al.3also reported that LVSI is the most potent independent risk factor for lymph node metastasis and poor survival in patients with endometrioid adenocarcinoma.

However, LVSI cannot currently be assessed by preoperative biopsy, and its status can only be determined by pathology after the surgical removal of the uterine body10. Therefore, preoperative noninvasive prediction of LVSI status in EAC can help in clinical decision-making. Several studies have developed predictive nomograms for LVSI using MRI or clinical parameters11]– [12. However, to date, no validated ultrasound-based radiomics model exists for LVSI prediction in EAC, presenting a significant research gap.

Radiomics can extract a significant amount of hidden, objective data inaccessible to regular examiners13. Radiomics, first introduced in 2012, involves utilizing computers to extract and analyze numerous advanced quantitative imaging features from medical images14. This process provides significant diagnostic and therapeutic information that benefits medical professionals15. Information about the tumor is obtained by analyzing quantitative image features such as intensity, shape, size or volume, and texture. These features are then utilized to develop a model16. Being able to visualize the heterogeneity of a tumor can help determine its aggressiveness and diversity.

At present, radiomics has made significant progress in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). An MRI-based nomogram with an receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of 0.89 in the training set and 0.85 in the test set demonstrated the ability to accurately predict LVSI in patients with early EC, according to a multicenter investigation17. Based on the radiomic and clinical characteristics of multi-parameter MRI, Wang et al. established a combination model with an AUC of 0.88 that had a good predictive value for LVSI status in EC patients18. However, MRI has drawbacks, including cost, length of examination, and contraindications for some individuals (such as those with certain implants). These factors contribute to MRI’s limited ability to predict LVSI. We hypothesized that ultrasound-based radiomics could offer a more accessible alternative with performance comparable to MRI for this specific task.

For the assessment and ongoing monitoring of uterine and adnexal disorders, ultrasound has long been the preferred non-invasive, inexpensive, radiation-free imaging technique. More and more studies have extended radiomics to ultrasound imaging and achieved encouraging results. Relevant literature reported that ultrasound radiomics could preoperatively predict the presence of LVSI in breast cancer and rectal cancer and showed good predictive ability (AUC was more significant than 0.84)19,20. However, few reports in the literature on ultrasound radiomics predict preoperative LVSI in EAC. Therefore, we conducted the study.

Methods

Research population

This is a single-center retrospective observational study. The Medical Ethics Committee of the Central Hospital of Wuhan approved the study, and all research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent to participate was waived by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Central Hospital of Wuhan with the approval number of WHZXKYL2022-230-01 and all research was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. EAC patients confirmed by postoperative pathology in our hospital from December 2017 to December 2022 were retrospectively analyzed.

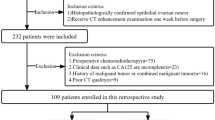

The inclusion criteria for this study were: (1) Transvaginal ultrasound examination was performed within 14 days before surgery; (2) All patients underwent endometrial biopsy before operation. (3) Each patient underwent a hysterectomy or radical hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection. (4) postoperative pathological results confirmed EAC, and the basic clinical data of the patients were complete. The following patients were excluded from the study: (1) Those whose LVSI diagnosis was ambiguous; (2) Those who were given adjuvant chemoradiotherapy before surgery; (3) Those whose low-quality pictures made it challenging to identify the endometrial lesion. Finally, 171 patients were identified and assigned to the training set and the test set by stratified random sampling with a ratio of 0.7:0.3. Clinical and pathological data, such as the patient’s age, menopause status, tumor size, preoperative histological grade, LVSI, Ki-67and serum CA125, CA199, etc., were gathered from the electronic medical record. Tumor size, the maximum diameter of the tumor, was derived from ultrasonic examination. No missing data were present in the final cohort for the analyzed variables. A post-hoc power analysis was conducted to indicate that our sample size provided over 90% power to detect a significant difference for the primary outcome, confirming the adequacy of the cohort for this study.

Histopathological analysis and the gold standard

Endometrial biopsy was performed through simple biopsy, dilatation, and curettage or hysteroscopic resection. Tumor histological grade and Ki67 were based on preoperative endometrial biopsy. EAC was histopathologically divided into two groups: low-grade EAC (FIGO G1-G2) and high-grade EAC (FIGO G3)21. The number of solid, nonsquamous components determined the FIGO grading system for EAC. Grades 1, 2, and 3 were characterized by ≤ 5%, 6–50%, and > 50% solid nonsquamous components, respectively22. All patients underwent bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and complete hysterectomy. LVSI is a morphologically viable tumor embolus located within the endothelial-lined lumina, including red blood cells or lymphocytes outside the tumor mass23. The postoperative pathological findings were finally regarded as the gold standard for the presence or absence of LVSI.

Instruments and methods of ultrasonic examination

Before surgery, every individual underwent a standardized preoperative assessment using transvaginal ultrasonography with a frequency range of 5-9 MHz high-end ultrasound devices (such as the Philips iU22, GE VolusonE10, and Mindray Resona7). The ultrasound examinations were performed using standard clinical presets for gynecological imaging. Key parameters such as gain, depth, and focal zones were optimized for each patient to ensure clear visualization of the endometrium and the lesion. The patient’s bladder was empty and in the lithotomy position. The probe was placed in the posterior vaginal fornix. The probe was rotated, and the uterine and pelvic cavity were observed. The size and shape of the uterus and double adnexa were analyzed, and the endometrial condition was evaluated. If a uterine lesion is found, it is necessary to scan it from multiple sections and angles to understand the overall information of the lesion. A radiologist with over ten years of experience in gynecological ultrasonography selected the tumor’s largest cross-section with the clearest imaging. The radiologist carefully scanned and studied the tumor’s size, shape, margin, and echo. All images were stored in DICOM format with original pixel spacing, and no resizing was performed.

Ultrasound image segmentation and feature extraction

The ultrasound images were exported from the imaging system. A free, open-source platform for medical image computation, 3D slicer v4.11 (http://www.slicer.org), was used to import the image24. Our criterion for drawing region of interest (ROI) is to draw along the tumor edge. The ROIs were manually delineated slice-by-slice on the 2D ultrasound image that displayed the largest cross-sectional area of the tumor. The radiologists were instructed to carefully trace the entire tumor boundary while excluding obvious artifacts and calcifications. In this study, the ROIs of the lesions were manually drawn on 2D ultrasound images using a 3D slicer by two radiologists who were unaware of the pathological findings. Additionally, 50 images were independently drawn by two radiologists after being chosen at random from all the images. The consistency of various observers was assessed using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). We regarded the features as having high confidence when their consistency tests were more than 0.75 and kept them for further research. The average ICC for the retained features was 0.82 (range: 0.76–0.91). The 3D Slicer Radiomics Extension Pack was used to extract all radiomics features.

Feature selection and model establishment

A total of 837 ultrasound radiomics features were extracted from each ultrasound image. We utilized Z-score normalization for these features to enhance the comparability of quantitative radiomics features. Specifically, each feature was standardized by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation across the training set, and the same transformation was applied to the test set. Subsequently, T-test was used for statistical analysis of all ultrasound radiomics features, and only ultrasound radiomics features with p values less than 0.05 were retained. This resulted in 152 features being retained for further analysis.

For the highly reproducible ultrasound radiomics features, the Pearson correlation coefficient was used to measure the correlation between them. When the correlation coefficient between any two ultrasound radiomics features was greater than 0.9, only one of the features was retained. After this step, 48 features remained.

We used least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO)regression, which was implemented using the ‘glmnet’ package in R, and tenfold cross-validation on the training data set to identify the non-zero features to LVSI status prediction, creating the radiomics score (Rad-score) with the remaining 7 features. The optimal λ parameter was selected using the minimum criteria from the 10-fold cross-validation. We used multifactor logistic regression modeling to construct the radiomics model and selected the optimal subset of features from the training set. Univariate analyses were utilized to identify the clinicopathological risk factor associated with LVSI.

We conducted a multivariate logistic regression analysis to choose the ultimate predictors for LVSI, considering the Rad-scores and independent clinical variables. A comprehensive prediction model was established based on the multivariate logistic regression analysis in the training cohort, and a nomogram was drawn. A clinical model was created using only the independent clinical risk factors to compare. Next, the nomogram’s performance was evaluated in the test set using the AUC. The sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of the final models were computed. The Delong test was used to compare different AUC.

Statistical analysis

For the analysis, we used SPSS 22.0 and R language (version 4.2.2). Specific R packages included: glmnet for LASSO, pROC for ROC analysis and Delong test, rms for nomogram and calibration curve, and rmda for decision curve analysis. We utilized the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact probability technique to statistically analyze count data and test hypotheses related to radiomics features. We employed the independent samples T-test or Mann-Whitney U test to analyze measurement data. Specifically, the Chi-square test was used for categorical variables (e.g., menopause status, histological grade), and the Mann-Whitney U test was used for continuous variables that were not normally distributed (e.g., Rad-score). If the two-sided p-value is less than 0.05, it is considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinicopathological data of the patients

In this study, a total of 171 patients who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria were included. They were then divided into the training set (119 patients) and the test set (52 patients) using stratified random sampling in a ratio of 0.7:0.3.

There were 132 cases in the LVSI-negative group, while the LVSI-positive group had 39 cases. The clinically acceptable thresholds for CA125 and CA199 in endometrial cancer are 35U/mL and 25U/mL, respectively25. When at least 40% of tumor cells express Ki-67, it is considered to have a high expression (+)26. The clinical and pathological information on EC is shown in Table 1. Age, menopausal status, tumor size, preoperative histological grade, LVSI, Ki-67, and serum CA125 and CA199 differences between the two sets are not statistically significant (p > 0.05 for all), indicating that it was reasonable to divide the two groups at random.

Radiomics feature extraction

The radiomics workflow is demonstrated in Fig. 1.

There were 837 ultrasound radiomics features taken from lesions in each patient. After LASSO regression and tenfold cross-validation, seven radiomics ultrasound features were utilized as the radiomics signatures for predicting LVSI in EC. The selected features primarily originated from wavelet-transformed images and included first-order statistics and texture features, suggesting that both intensity distribution and textural heterogeneity patterns are relevant for LVSI prediction.

The Rad-score formula of the radiomics is as follows:

Rad-score=-1.25-0.01xOriginal_firstorderTotalEnergy-0.20xWavelet.HLHglszmZone%-0.18xWavelet.HHLfirstorderSkewness-0.12xWavelet.HHLfirstorderTotalEnergy-0.10xWavelet.HHLfirstorderMedian-0.07xWavelet.LHHglszmLowGrayLevelZoneEmphasis-0.01xWavelet.HHHglrlmGrayLevelVariance.

Model establishment and efficacy assessment

In this training set, we utilized logistic regression on the best subset of features to construct an ultrasound radiomics model. Additionally, we evaluated the model using the test set. The ultrasound radiomics model had an AUC of 0.80 (95% CI: 0.71–0.89) for the training set and an AUC of 0.74 (95% CI: 0.56–0.92) for the verification set.

Univariate analysis found that preoperative histological grade and Ki67 were significant predictors of LVSI. After multivariate analysis, the preoperative histological grade was demonstrated as an independent predictor of LVSI (Table 2). A clinical model was developed using the independent predictors, and it was found to have an AUC of 0.71 (95% CI 0.60–0.82) in the training group and 0.66 (95% CI 0.49–0.82) in the test group.

A comprehensive prediction model was created by combining the preoperative histological grade and the Rad-score through multivariate logistic regression analysis. The comprehensive predictive model had an AUC of 0.84 (95% CI: 0.76–0.92) in the training set (Fig. 2A) and 0.75 (95% CI: 0.57–0.93) in the test set (Fig. 2B).

The training set’s sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy were 0.96, 0.64, and 0.71, respectively, and those of the test set were 0.75, 0.70, and 0.71, respectively (Table 3). And the performance comparison among the three models were shown in Table 4. The Delong test indicated that the combined nomogram performed significantly better than the clinical model in the training cohort (p = 0.007), but the improvement over the radiomics model alone was not statistically significant in either cohort (training p = 0.371, test p = 0.776).

Figure 3A displays a nomogram that utilizes a comprehensive prediction model to quantify patient factors and predict the presence or absence of LVSI before surgery. According to the calibration curve in Fig. 3B, the comprehensive prediction model in our study is accurate. Based on Fig. 3C, the comprehensive prediction model showed strong clinical utility according to decision curve analysis (DCA).

Discussion

LVSI has been recognized as an essential predictor of EAC lymph node involvement, high risk of early EAC recurrence, and poor survival27,28. Preoperative prediction of LVSI is crucial because it can avoid overtreatment and guide the clinical selection of appropriate personalized treatment options. As a non-invasive examination method, MRI is currently the primary preoperative evaluation method for EAC. While MRI offers excellent soft tissue contrast, its higher cost, limited availability, and longer acquisition time make it less feasible for routine use in many clinical situations. Moreover, LVSI cannot be assessed by preoperative biopsy or by routine examination methods before surgery but only after surgical removal of the corpus uteri. During cryo-examination, the pathologist should be asked about LVSI status whenever the decision is made to proceed with lymphadenectomy. Therefore, preoperative prediction of LVSI status is essential. Ultrasound-based radiomics provides a promising alternative by leveraging widely available ultrasound images to extract quantitative features for predicting LVSI.

Our preliminary study showed LVSI related to preoperative staging and Rad- scores, but with age, menopausal status, tumor size, Ki − 67, serum CA125 and CA199, etc. Previous studies have shown that preoperative histological grade is a predictor associated with LVSI in EAC, which was confirmed in our study12,17,29. A retrospective study of 327 EC patients also reported that tumor size ≥ 2 cm was an independent factor for LVSI30. Tortorella et al.31reported that diffuse LVSI was significantly correlated with tumor size. Zhou et al.32showed that serum CA 125 ≥ 21.2 U/mL could predict LVSI positivity in EC women. Measuring the CA 125 level may help obtain a more accurate individual risk assessment of LVSI in EC patients. However, the study by Zhou et al. included 28 patients with non-endometrioid cancer as well as 183 patients with endometrioid cancer. These studies contradict our results. A possible weakness of our study may be the preoperative consideration of tumor size by ultrasound and tumor grade assessed by preoperative biopsy. The pathological grade of EAC is usually evaluated by curettage or endometrial biopsy. However, these methods are somewhat blind curettage and invasive, and the histological samples obtained are too small to accurately reflect the histological grade of the tumor. Preoperative assessment of these factors may be less accurate than final postoperative pathology and does not always correspond to definitive histological examination. Our preliminary study showed that ultrasound radiomics features based on the ultrasound image had high diagnosis performance for LVSI in EAC. The diagnostic performance of the nomogram model offers only a slight improvement compared to the radiomics model. This may be because the ultrasound radiomics features already contain information such as preoperative histological grade as well as tumor size or because we only included endometrioid adenocarcinoma.

The radiomics features selected in our model primarily reflect textural heterogeneity and intensity distribution patterns within the tumor. These quantitative descriptors may capture underlying pathological characteristics associated with LVSI, such as irregular vascular patterns, necrotic regions, and invasive tumor growth fronts, which are not discernible to the naked eye. This provides a potential biological rationale for the predictive capability of our ultrasound-based radiomics signature, translating subjective image appearances into objective, quantifiable data.

Our comprehensive model achieved a test AUC of 0.75, which is comparable to some MRI-based radiomics models for LVSI prediction in EC, which reported test AUCs ranging from 0.75 to 0.8817,18,29. While MRI benefits from superior soft-tissue contrast and is currently the primary preoperative imaging modality for EC staging, our ultrasound-based approach offers a widely accessible, cost-effective, and real-time alternative. The performance of our model, coupled with the advantages of ultrasound, suggests that ultrasound radiomics holds significant promise as a valuable preoperative tool, particularly in resource-constrained settings or as a complementary test to refine risk stratification.

The proposed nomogram offers a user-friendly, quantitative tool for clinicians to preoperatively stratify the risk of LVSI in EAC patients. This could potentially aid in surgical planning, such as tailoring the extent of lymphadenectomy, and in counseling patients regarding their individualized risk profile and potential need for adjuvant therapy. By providing a non-invasive estimate of LVSI status, this model may help to optimize treatment strategies and avoid both under- and over-treatment. For example, during the preoperative ultrasound examination, the radiologist could segment the tumor, calculate the Rad-score, and use the nomogram to estimate the probability of LVSI. This quantitative assessment could then be discussed in a multidisciplinary team meeting to guide decisions regarding the extent of lymphadenectomy. Future integration with AI tools could potentially automate feature extraction and score calculation, enabling real-time risk prediction during the ultrasound scan itself.

Our study has some potential advantages. The meta-analysis by Meng33 et al. showed that MRI had moderate diagnostic power for assessing the LVSI status of endometrial cancer, but its clinical applicability was poor. Although MRI has better spatial resolution and quantitative stability, ultrasound has several advantages over MRI in terms of ease of operation and providing real-time observation. This makes it an essential tool in the diagnosis and treatment of EAC. Radiomics is vital in diagnosing diseases, predicting tumors’ biological behavior, and assessing treatments’ effectiveness. Wu et al.19 performed a retrospective analysis of 203 patients with rectal cancer based on ultrasound images and established a model to predict LVSI of rectal cancer before surgery. Luo et al.29applied MRI radiomics to predict LVSI of EC, but they included only 144 patients in this study. Xi et al.34 conducted a retrospective diagnostic model in identifying ovarian cancer based on ultrasound and the outcome was promising. However, there are few reports on ultrasound-based radiomics that pre-predict LVSI in EAC. In addition, in our study, all patients with non-endometrioid adenocarcinoma were excluded to eliminate the influence of different histological subtypes on the ultrasound radiomics results.

To address reproducibility, while we acknowledge that feature values may vary across different devices, we mitigated this by applying normalization to minimize batch effects and improve the generalizability of the radiomics features. And to reduce segmentation variability, all ROIs were manually segmented by two experienced radiologists blinded to the clinical outcomes. We assessed inter-observer reproducibility using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for radiomics features, and only features with ICC > 0.75 were retained for model building. This ensures that the selected features are robust and reproducible across different observers. The combined nomogram is in fact a comprehensive judgment made after fully considering clinical factors and ultrasound imaging characteristics, which is very beneficial for clinicians.

Our study has some limitations that must be addressed for more accurate results. First, the study’s retrospective design was conducted in a single institution. Second, the lack of external validation limits the generalizability of our findings; future multi-center external validation is necessary to confirm the model’s performance across different populations and ultrasound machines. Third, we only captured ultrasound 2D images of the most significant sections, which may have missed essential details related to intratumoral heterogeneity present in the entire tumor volume. Fourth, while we used multiple ultrasound devices, the potential variability in radiomics features across different manufacturers and protocols, despite our standardization efforts, remains a concern. Fifth, the absence of a central pathology review for LVSI status might introduce some variability in the reference standard. Finally, our model requires prospective validation in a clinical setting to assess its real-world impact.Hence, future studies must conduct a large sample, multi-center, and multi-modal prospective cohort study with strict variable control to ensure better accuracy.

Conclusions

In summary, we have developed a comprehensive prediction model to provide clinicians with a new method for noninvasively predicting the presence or absence of LVSI in EAC before surgery. This tool demonstrates high sensitivity with moderate specificity, offering a valuable and accessible complement to existing preoperative assessments.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71 (3), 209–249 (2021).

Katagiri, R. et al. Reproductive factors and endometrial cancer risk among women. JAMA Netw. Open. 6 (9), e2332296 (2023).

Stålberg, K. et al. Lymphovascular space invasion as a predictive factor for lymph node metastases and survival in endometrioid endometrial cancer - a Swedish gynecologic cancer group (SweGCG) study. Acta Oncol. 58 (11), 1628–1633 (2019).

Passarello, K., Kurian, S. & Villanueva, V. Endometrial cancer: an overview of Pathophysiology, Management, and care. Semin Oncol. Nurs. 35 (2), 157–165 (2019).

Kim, S. I. et al. Prediction of lymphovascular space invasion in patients with endometrial cancer. Int. J. Med. Sci. 18 (13), 2828–2834 (2021).

Peters, E. E. M. et al. Reproducibility of lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI) assessment in endometrial cancer. Histopathology 75 (1), 128–136 (2019).

Crosbie, E. J. et al. Endometrial cancer. Lancet 399 (10333), 1412–1428 (2022).

Concin, N. et al. ESGO/ESTRO/ESP guidelines for the management of patients with endometrial carcinoma. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 31 (1), 12–39 (2021).

Yarandi, F., Shirali, E., Akhavan, S., Nili, F. & Ramhormozian, S. The impact of lymphovascular space invasion on survival in early stage low-grade endometrioid endometrial cancer. Eur. J. Med. Res. 28 (1), 118 (2023).

Long, L. et al. MRI-based traditional radiomics and computer-vision nomogram for predicting lymphovascular space invasion in endometrial carcinoma. Diagn. Interv. Imaging. 102 (7–8), 455–462 (2021).

Valletta, R. et al. A nomogram for preoperative prediction of tumor aggressiveness and lymphovascular space involvement in patients with endometrial cancer. J. Clin. Med. 14 (11), 3914 (2025).

Celli, V. et al. MRI- and Histologic-Molecular-Based Radio-Genomics nomogram for preoperative assessment of risk classes in endometrial cancer. Cancers (Basel). 14 (23), 5881 (2022).

Moro, F. et al. Developing and validating ultrasound-based radiomics models for predicting high-risk endometrial cancer. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 60 (2), 256–268 (2022).

Kumar, V. et al. Radiomics: the process and the challenges. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 30 (9), 1234–1248 (2012).

Litvin, A. A., Burkin, D. A., Kropinov, A. A. & Paramzin, F. N. Radiomics and digital image texture analysis in oncology (Review). Sovrem Tekhnologii Med. 13 (2), 97–104 (2021).

Gillies, R. J., Kinahan, P. E. & Hricak, H. Radiomics: images are more than Pictures, they are data. Radiology 278 (2), 563–577 (2016).

Liu, X. F., Yan, B. C., Li, Y., Ma, F. H. & Qiang, J. W. Radiomics feature as a preoperative predictive of lymphovascular invasion in early-stage endometrial cancer: A multicenter study. Front. Oncol. 12, 966529 (2022).

Wang, J. J. et al. Prediction of lymphovascular space invision in endometrial cancer based on Multi-parameter MRI radiomics model. Curr. Med. Imaging. 20, e15734056266366. (2024).

Wu, Y. Q. et al. An endorectal ultrasound-based radiomics signature for preoperative prediction of lymphovascular invasion of rectal cancer. BMC Med. Imaging. 22 (1), 84 (2022).

Du, Y. et al. Ultrasound radiomics-based nomogram to predict lymphovascular invasion in invasive breast cancer: a multicenter, retrospective study. Eur. Radiol. 34 (1), 136–148 (2024).

Colombo, N. et al. ESMO-ESGO-ESTRO consensus conference on endometrial cancer: diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 27 (1), 16–41 (2016). ESMO-ESGO-ESTRO Endometrial Consensus Conference Working Group.

Soslow, R. A. et al. Endometrial carcinoma diagnosis: use of FIGO grading and genomic subcategories in clinical practice: recommendations of the international society of gynecological pathologists. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 38 (Suppl 1(Iss 1 Suppl 1), S64–S74 (2019).

Bereby-Kahane, M. et al. Prediction of tumor grade and lymphovascular space invasion in endometrial adenocarcinoma with MR imaging-based radiomic analysis. Diagn. Interv Imaging. 101 (6), 401–411 (2020).

Fedorov, A. et al. 3D slicer as an image computing platform for the quantitative imaging network. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 30 (9), 1323–1341 (2012).

Jiang, P. et al. Combining clinicopathological parameters and molecular indicators to predict lymph node metastasis in endometrioid type endometrial adenocarcinoma. Front. Oncol. 11, 682925 (2021).

Kong, W. et al. Development and validation of a nomogram involving immunohistochemical markers for prediction of recurrence in early low-risk endometrial cancer. Int. J. Biol. Markers. 37 (4), 395–403 (2022).

Peters, E. E. M. et al. Substantial lymphovascular space invasion is an adverse prognostic factor in High-Risk endometrial cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 41 (3), 227–234 (2022).

Veade, A. E. et al. Associations between lymphovascular space invasion, nodal recurrence, and survival in patients with surgical stage I endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma. World J. Surg. Oncol. 17 (1), 80 (2019).

Luo, Y., Mei, D., Gong, J., Zuo, M. & Guo, X. Multiparametric MRI-Based radiomics nomogram for predicting lymphovascular space invasion in endometrial carcinoma. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 52 (4), 1257–1262 (2020).

Oliver-Perez, M. R. et al. Lymphovascular space invasion in endometrial carcinoma: tumor size and location matter. Surg. Oncol. 37, 101541 (2021).

Tortorella, L. et al. Substantial lymph-vascular space invasion (LVSI) as predictor of distant relapse and poor prognosis in low-risk early-stage endometrial cancer. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 32 (2), e11 (2021).

Zhou, X., Wang, H. & Wang, X. Preoperative CA125 and fibrinogen in patients with endometrial cancer: a risk model for predicting lymphovascular space invasion. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 28 (2), e11 (2017).

Meng, X. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of MRI for assessing lymphovascular space invasion in endometrial carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Acta Radiol. 65 (1), 133–144 (2024).

Xi, M. et al. Ultrasonographic diagnosis of ovarian tumors through the deep convolutional neural network. Ginekol. Pol. 95, 181 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept and design (XY, BZ, JL), acquisition of data (XY, BZ, YY), analysis and interpretation of data (BZ, WL), drafting of the manuscript (XY, BZ), critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content (JL, XC), technical support (XS), and study supervision (JL). All authors have made a significant contribution to this study and have approved the final manuscript. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ye, X., Zhou, B., Yang, Y. et al. Ultrasound based radiomics nomogram combined with clinical parameters to predict lymphovascular space invasion in endometrioid adenocarcinoma. Sci Rep 16, 751 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30324-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30324-7