Abstract

This study investigates the combined use of concrete demolished waste powder (CDWP) and tile waste powder (TWP) as partial replacements for cement (0 to 15%) and fine aggregate (0 to 30%) in concrete. The concrete fresh properties, hardened properties and microstructural analysis were evaluated. Results show that CDWP and TWP reduce workability due to their rough and angular nature. The optimum replacement levels (5% CDWP and 10% TWP) improve fresh density and enhance mechanical strength through pozzolanic activity and improved interfacial transition zone (ITZ). However, higher replacement levels adversely affect workability and microstructure which leads to reduced strength. A strong correlations were observed between fresh properties and hardened properties. Furthermore, the SEM analysis confirms that improved microstructure is observed at lower replacement levels (5% CDWP and 10% TWP) and weak microstructure at higher levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rapid industrialization, urban expansion, and population growth have led to a sharp rise in waste generation and present serious environmental hazards1. Also, the concrete industry is a major contributor to carbon dioxide emissions and negative impacts on the environment2. Recycling waste materials in the concrete industry has gained significant importance due to the environmental pollution caused by increasing waste generation3. The consumption of natural resources and the management of solid waste present significant challenges4. To promote sustainability, researchers are exploring the use of various waste materials in concrete. The use of waste materials conserves natural resources and decreases carbon dioxide emissions5. A study6 also highlighted that the utilization of waste materials in concrete is essential for promoting sustainability and reducing the cost of concrete. Globally, construction and demolition waste (C&D) is estimated at around 2 to 3 billion tons per year. Also, C&D accounts for 25 to 30% of total waste generation. The C&D waste is further increasing at the rate of 3 to 5% annually due to the rapid urbanization, infrastructure expansion, and population growth7. Furthermore, the study8 also indicates that the use of ceramic materials such as tiles, sanitary fittings, and electrical insulators has been steadily increasing in modern construction. However, a significant amount of these ceramics becomes waste during manufacturing, transportation, and installation because of their brittle characteristics. In line with this, a study9 highlights that the growing demand for concrete in infrastructure development is placing significant pressure on natural resource reserves. Therefore, incorporating ceramic waste into concrete production presents a promising approach to both environmental conservation and concrete properties.

Incorporating fine ceramic aggregates up to 20% enhances the compressive and flexural strengths of mortars. However, the strengths tend to decline as the proportion of ceramic aggregates continues to further increase (more than 20%)10. The findings indicate that the strength of concrete decreases with an increasing proportion of waste ceramic tile aggregates. However, up to 10% of tile aggregate appears feasible, as the reduction in strength remains relatively minor11. The optimal replacement of ceramic waste aggregate was 20%. The concrete made with 20% ceramic waste aggregate shows superior strength properties compared to other mixtures12. Furthermore, results indicated that concrete mixtures containing 50% CTW as a replacement for brick aggregates showed an approximately 16.7% increase in mechanical strength13. A study14 concluded that sand can be replaced with up to 5% waste tiles and coarse aggregates can be substituted with up to 25% waste tiles. Also, study15 noted that the concrete mix made with 15% ceramic tile waste as a replacement for fine aggregate achieved optimal strength.

However, the study16 indicates that fine ceramic aggregates led to an improvement in concrete strength, but the improvement in concrete strength was small. A review17 also concluded that numerous researchers have found that concrete exhibits low compressive strength during its early stages of curing. A study18 also highlights that the reduction in density and strength is attributed to ceramic waste having a lower weight and higher porosity compared to conventional coarse aggregate. Furthermore, the study11 concluded that both compressive and split tensile strengths gradually declined as the proportion of tile aggregate in the mix increased. The reduction in strength is due to weak bonding at the interface between the cement paste and the tile aggregates.

The bonding can be improved by using supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) such as fly ash19, silica fume20, waste glass21, waste marble22 and steel slag23. The SCMs improve bonding by reacting chemically with calcium hydroxide (CH) released during cement hydration. The pozzolanic reaction produces additional calcium silicate hydrate (CSH) gel. The CSH gel densifies the bond between the cement paste and aggregates. A denser ITZ reduces porosity and microcracks, enhancing adhesion and mechanical interlocking. The concrete microstructure becomes stronger, which leads to improved compressive and tensile strengths. Therefore, the performance of concrete made with ceramic waste can be improved with the addition of pozzolanic materials.

Similarly, concrete demolished waste powder (CDWP) can also act as a supplementary cementitious material. The CDWP contains unhydrated cement particles and exhibits pozzolanic activity, which contributes to additional CSH formation and densification of the cement mix. Thereore, the literature highlights CDWP potential as a sustainable SCM for improving the performance of concrete. In line with this, a study confirmed that both processing waste and demolition waste exhibited pozzolanic activity24. The concrete mix made with 20% CDWP is lighter and exhibits improved workability. Also, it achieves a strength of 14 MPa (28 days), which is 1 MPa below the required characteristic strength25. A study also indicates that replacing recycled powder up to 30% has either a positive impact or only a slight adverse effect on the mechanical properties of recycled powder concrete26. The findings also indicate that concrete demolished waste fines can be used in large amounts within ternary blends to refine pore structure, lower water absorption, and preserve mechanical strength in the 40 MPa class concrete27.

Research significance

The previous research has mostly focused on the individual use of CDWP and TWP. However, limited attention given to their combined application in concrete. The combined use of CDWP and TWP in concrete has not been extensively explored. In this study, concrete waste demolished waste powder (CDWP) was used as a pozzolanic material. The replacement percentages of CDWP vary from 0 to 15% and 0 to 30% for TWP. Fresh properties were evaluated through slump flow and fresh density while the hardened properties were evaluated through compressive and tensile strength. Also, the correlations between fresh and hardened properties were developed, and microstructural analysis was performed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The findings of this study demonstrate that ceramic waste materials combined with CDWP can be effectively used as partial replacements for cement and aggregates in concrete production. The approach not only promotes sustainable construction by reducing landfill waste and conserving natural resources but also improves the mechanical properties of concrete.

Materials

Cement

Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC) with normal setting times was used as the binder throughout the study. The cement type and properties were kept constant in all mixtures to ensure consistency and reliable comparison of results.

Aggregates

Natural river sand, locally available and commonly used in practical construction, was employed as the fine aggregate. Furthermore, normal weight crushed coarse aggregate with a maximum size of 19.5 mm was used as coarse aggregate. Both fine and coarse aggregates were used in a saturated surface dry (SSD) condition to ensure consistent moisture content, which helps maintain accurate water-to-cement ratios and improves the reliability of the concrete mix design.

Concrete demolished waste powder

Concrete demolished waste was collected, then crushed and ground in the laboratory to produce a fine powder with particle sizes below 75 microns (passing sieve #200), comparable to the typical particle size of cement. Figure 1 shows the concrete demolished waste and the ground powder. The fine particle size enhances the powder reactivity by increasing its surface area which promotes pozzolanic reactions within the cementitious matrix. Therefore, the powder is suitable for use as a partial replacement of cement in concrete mixtures.

The chemical composition of the demolished concrete waste powder was determined using X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectroscopy. The measurements were performed with an EDX-7000 spectrometer under an air atmosphere, employing a 10 mm collimator diameter. Samples were prepared in polypropylene cups, and data acquisition was conducted in live mode for 60 s. The instrument utilized a Rhodium (Rh) target X-ray tube, operating at 50 kV and a current of 31 µA. The XRF spectrum of demolished concrete waste powder is presented in Fig. 2. The XRF spectrum of the powdered demolished concrete waste reveals a complex elemental composition characteristic of typical cementitious materials.

Furthermore, the quantitative elemental and oxide composition of CDWP is presented in Table 1. The findings reveal that CDWP is a promising material for partial cement replacement in concrete production. The major oxides present in CDWP are silicon dioxide (SiO2) and calcium oxide (CaO) which are 53.669% and 35.668%, respectively. Silicon dioxide plays a crucial role in pozzolanic activity by reacting with CH to form additional CSH gel. The CSH gel contributes to improving the binding properties and enhances the strength and durability of concrete. Furthermore, calcium oxide contributes hydraulic properties that are essential for cement hydration and subsequent strength development. Additionally, element analysis indicates minor amounts of aluminum (4.115%) and iron (8.286%) are present, which contribute to the formation of calcium aluminate and ferrite phases. The calcium aluminate and ferrite can influence the setting time and early strength gain of the cementitious matrix. Other oxides, such as titanium dioxide (TiO2), potassium oxide (K2O), and sulfur trioxide (SO3), are present in small amounts and do not significantly affect the microstructure and durability of the cementitious matrix. The sum of silicon dioxide (SiO2), calcium oxide (CaO), and iron oxide (Fe2O3) in the concrete demolished waste powder (CDWP) exceeds 70%. Therefore, it can be considered a pozzolanic material and can be used as a partial cement replacement in concrete.

Tile waste

Tile waste was collected from a construction demolition site and grinding to reduce the particle size to less than 4.75 mm (pass through a sieve #4), comparable to the particle size of natural sand. Figure 3 illustrates the original tile waste and the fine tile powder. The use of recycled tile waste not only promotes sustainable construction practices by reducing landfill disposal but also offers potential benefits in improving concrete properties.

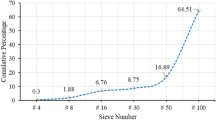

The scanning electron microscopy (SEM) results indicate that the tile waste particles exhibit a rough surface texture with irregular and angular shapes (Fig. 4). The rough and angular surfaces are beneficial as they enhance particle interlocking and provide additional friction, which improves the bond strength between the tile particles and the cement matrix. Therefore, the stronger bond can contribute to the concrete strength. However, the irregular shape of the tile particles negatively affects the workability of the mix due to increasing internal friction among the particles. Furthermore, the particle size distribution observed through SEM confirms the presence of a range of fine to coarse particles. The variation in particle sizes allows better packing density and reduces the voids within the concrete mix. Therefore, the reduced voids lead to enhanced durability and mechanical properties when tile waste is used as a partial replacement for fine aggregate in concrete.

Testing procedure

The flowability of concrete with varying percentages of concrete demolished waste powder (CDWP) and tile waste powder was evaluated through the slump cone test as per ASTM C143/C143M standard28. The test measured the workability of fresh concrete mixes by determining the slump value, which indicates the consistency and ease of placement of concrete. The compressive strength of the concrete mixes containing different proportions of CDWP and tile waste powder was assessed using cylindrical specimens with dimensions of 150 mm diameter by 300 mm height. The sample was prepared and tested as per ASTM C39/C39M standards29. The compressive strength test was conducted at both 7 and 28 days of curing. Similarly, the tensile strength of the concrete was determined through the splitting tensile strength test as per ASTM C496/C496M standard procedures30. The cylindrical specimens of size 150 mm in diameter and 300 mm in height were casted for the splitting tensile strength test. The splitting tensile strength test was conducted at both 7 and 28 days of curing. The microstructural characteristics of concrete incorporating varying percentages of CDWP and TWP were examined using SEM. SEM analysis was performed to investigate the internal structure and bonding behavior within the concrete matrix influenced by the CDWP and TWP. The specimens for SEM were collected from the central portion of broken samples obtained after strength testing to ensure representative microstructural features of the fractured surface. Furthermore, before the imaging, the samples were carefully polished to produce a smooth surface, enhancing visibility and contrast of the microstructural details.

Mix design, sample Preparation and casting

In this study, the cement was partially replaced with concrete demolished waste powder (CDWP) in varying percentages from 0%, 5%, 10% and 15%. Furthermore, the sand was partially replaced with tile waste powder (TWP) in varying percentages from 0%, 10%, 20% and 30%. The concrete mix design was carried out using the nominal mix proportion of 1:1.5:3. The water-to-cementitious material ratio (w/cm) was maintained constant at 0.60 for all mixes to ensure comparable hydration conditions. The details quantification of materials is presented in Table 2. Concrete specimens incorporating varying percentages of CDWP and TWP were prepared with standard casting procedures to ensure uniformity. Before the mixing process started, all raw materials, including cement, sand, coarse aggregates, CDWP, and TWP were accurately weighed according to the designed mix proportions (Table 2).

The dry materials were thoroughly mixed in a mixer to achieve a homogeneous blend. Subsequently, the required amount of water was gradually added while mixing continued to form a consistent concrete mix, typically ranging from 8 to 10 min. The mixer stops once a uniform mix is achieved. Immediately after the mixing process stopped, the fresh concrete was transferred to a slump cone to evaluate its flowability and then filled the steel cylindrical molds measuring 150 mm in diameter and 300 mm in height for compressive and splitting tensile strength tests. The molds were filled in three equal layers, with each layer compacted by 25 blows of a standard tamping rod to eliminate entrapped air and ensure proper consolidation. After filling the molds, the top surface of each specimen was leveled and finished with a trowel. After 24 h, the specimens were demolded carefully and submerged in a water tank maintained at room temperature (25 to 30 °C) for curing until the specified testing ages of 7 and 28 days.

Results and discussions

Fresh concrete

Slump flow

Figure 5 shows the slump flow of concrete with varying proportions of cement replaced by concrete demolished waste powder (CDWP) and sand replaced by tile waste powder (TWP). The findings indicate that the control mix (C0T0) showed the highest slump value of 83 mm, indicating superior workability as compared to the other mixes made with CDWP and TWP. However, the slump value decreased with the substitution of CDWP and TWP. The mix made with 5% CDWP and 10% TWP replacement (C5T10) showed a slump of 78 mm, and the mix made with 10% CDWP and 20% TWP (C10T20) showed 63 mm. The mix with the highest replacement levels of 15% CDWP and 30% TWP (C15T30) exhibited the lowest slump value of 45 mm. Therefore, the results suggest that increasing the substitution of cement and fine aggregate with CDWP and TWP, respectively, adversely affects the concrete’s workability. The decrease in slump is primarily due to the physical characteristics of the CDWP and TWP particles, which possess a rough surface texture and angular shape compared to the smoother, more rounded natural aggregates and cement particles. The rough surface texture and angular shape lead to an increase in internal friction and inter-particle resistance within the concrete mix, which results in lower flowability. A study16 also indicates that ceramic materials with greater porosity tend to absorb more water. Therefore, less free water is available for flowability. A similar study31 noted that the angular texture and rougher surface of ceramic waste particles increase internal friction within the concrete mixture, reducing fluidity and making the mix harder to handle. Additionally, the higher water absorption by ceramic particles decreases the amount of free water in the mix, which is essential for preserving workability. Therefore, as the replacement levels of waste increase, the concrete mixture becomes stiffer and less workable. Although the use of plasticizers is recommended in practice to improve flowability at higher replacement levels. However, no admixtures were used in this study which highlights the limitation and need for future research to investigate the effectiveness of plasticizers in such mixes.

Fresh density

Figure 6 shows the fresh density of concrete mixes made with partial replacements of cement by CDWP and sand by TWP at various proportions. The findings indicate that the control mix (C0T0) exhibited a fresh density of 2275 kg/m³ and the mix made with 5% CDWP and 10% TWP (C5T10) shows a fresh density of 2295 kg/m³.

However, further increases in the replacement levels to 10% CDWP with 20% TWP (C10T20) and 15% CDWP with 30% TWP (C15T30) resulted in a gradual decrease in fresh density (2280 kg/m³ and 2225 kg/m³, respectively). Therefore, the results indicate that moderate replacement of cement and sand with CDWP and TWP (C5T10) can enhance the fresh density of the concrete mix due to improved particle packing and reduced void content. The finer particles of CDWP and TWP fill the voids between the coarser aggregates and cement particles which lead to a denser and more compact fresh concrete. Additionally, the angular and irregular shapes of the waste powders can contribute to mechanical interlocking which further enhances the packing efficiency. However, the higher replacement levels appear to reduce the density due to low flowability which increases the risk of voids. The reduced flowability, particularly at higher percentages of waste materials, limits the ability of the mix to compact properly and increases the risk of entrapped air voids. Therefore, the presence of such voids diminishes the overall fresh density and may negatively impact the workability and mechanical performance of the hardened concrete.

Hardened concrete

Compressive strength

Figure 7 shows the compressive strength of concrete mixes with partial replacement of cement by CDWP and sand by TWP at varying replacement levels. The findings indicate that the control mix (C0T0), with no replacements, achieved a compressive strength of 31.4 MPa at 28 days. The mix made with 5% of the cement was replaced by CDWP and 10% of the fine aggregate by TWP (C5T10), the compressive strength increased to 33.8 MPa which indicates an improvement a compressive strength as compared to the reference concrete. The increase in strength can be attributed to the pozzolanic activity of the waste powders, which contain reactive silica and alumina. The silica reacts with the CH produced during cement hydration to form an additional CSH gel. The secondary CSH gel contributes to the densification of the cementitious matrix by filling in the capillary pores and refining the pore structure. Furthermore, CSH gel improves the binding properties within the concrete which results in a stronger and more cohesive matrix. Furthermore, the ITZ improves due to the pozzolanic reaction and micro-filling effect of the waste powders. The denser microstructure and refined ITZ observed at mix C5T10 are expected to reduce permeability and enhance resistance to ingress of water and aggressive ions. Therefore, the findings suggest potential improvements in durability aspects such as sulfate resistance and reduced chloride penetration at lower substitution.

The fine particles of CDWP and TWP fill the voids and pores around the aggregate particles which leads to a denser packing in the ITZ. Similarly, a study32 indicates that replacing the cementitious paste with limestone fines (LF) improves strength and durability mainly due to enhancing the packing density of the mix. Also, the newly formed CSH gel due to pozzolanic reaction enhances the bond between the aggregate surface and the surrounding cement paste which reduces porosity and microcracks in the ITZ. The ITZ becomes stronger and more compact which improves the mechanical performance of the concrete. However, further increases in replacement levels to 10% CDWP and 20% TWP (C10T20) caused a slight reduction in compressive strength to 30.4 MPa. The decline suggests that higher proportions of waste materials adversely affect the concrete’s mechanical properties. Furthermore, the highest replacement level of 15% CDWP and 30% TWP (C15T30) mix shows significantly decreased compressive strength (26.7 MPa). The reduction in compressive strength at higher replacement levels (C15T30) occurs because the CDWP is less reactive than cement. Therefore, replacing high percentages of cement with less reactive materials reduces the cementitious compounds which leads to a weaker concrete mix. A study33 indicates that the decrease in strength can be attributed to the presence of excess chemical compounds that lack corresponding reactants to form hydration products. These unhydrated compounds can lead to poor packing density, which subsequently increases the pore volume within the mix. Furthermore, increasing the waste percentages reduces the workability of the fresh concrete mix which makes it harder to properly mix and compact. The poor compaction results in more air voids and a less dense concrete structure. Therefore, a less dense mix cause weak microstructure which leads to lower compressive strength. Also, the increase in porosity and reduction in compactness may lead to higher permeability and making the mixes more susceptable to durability-related deterioration.

Splitting tensile strength

The experimental results for the tensile strength of different concrete mixes are presented in Fig. 8. The findings indicate that the CDWP and TWP influence the tensile strength behavior of concrete in a non-linear manner. The control mix (C0T0) made of 100% ordinary Portland cement and natural sand shows a splitting tensile strength of approximately 3.2 MPa. The mix made with 5% CDWP and 10% TWP (C5T10) shows that the tensile strength increased to a peak value of 3.6 MPa. The improvement in tensile strength can be attributed to several contributing factors. Firstly, the pozzolanic reactivity of CDWP results in the consumption of CH and forms additional CSH gel. The CSH gel contributes to the refinement of the microstructure and densification of the cementitious mix. Secondly, the angular shape and rough texture of CDWP and TWP particles enhance the mechanical interlocking and bond strength which contribute positively to tensile performance. Also, the micro-filling ability of CDWP and TWP fine particles helps fill the voids within the mix which reduces porosity and leads to a denser concrete mix. However, a further increase in the replacement levels to 10% CDWP and 20% TWP (C10T20) resulted in a marginal decrease in tensile strength (3.5 MPa) but remained higher than the control mix (3.2 MPa). Furthermore, the mix made with the highest substitution levels (C15T30) showed a significant decrease in tensile strength, reducing to approximately 2.4 MPa. The reduction indicates that excessive substitution of reactive and cohesive cement with less reactive materials (CDWP) decreases the tensile capacity of concrete due to a weaker ITZ and increased internal porosity. Also, the higher CDWP and TWP percentages can adversely affect the workability of fresh concrete which makes the compaction process more difficult. The poor compaction contributes to the formation of voids and leads to reduced tensile capacity. Similarly, a study34 also concluded that when replacing a portion of cement with recycled fine powder in mortar and concrete, most mechanical properties tend to decline as the replacement level increases. Therefore, it is advisable to limit the replacement amount to no more than 20%.

Correlation between fresh and hardened properties

Figure 9 illustrates the correlation between slump flow and compressive strength at 7 and 28 days for concrete mixes made with varying CDWP and TWP percentages. Two linear regression models were developed to quantify the relationship for both curing ages. The findings indicate that a positive correlation exists between slump flow and strength properties. The improved workability enhances the compaction of the concrete mix which reduces the risk of internal voids and increases the density of the hardened mix. The enhanced compaction also facilitates better bonding between the cement paste and aggregates, which significantly contributes to both compressive and tensile strength development. For the 7 and 28 days, the compressive and tensile strength, the linear regression equation is

The equation indicates a strong linear correlation with an R² value of 0.81 (7 days) which highlights a significant dependence of early-age compressive strength on slump flow. The positive relationship demonstrates that the slump value is a critical factor influencing the mechanical performance of concrete, particularly when recycled materials such as CDWP and TWP are used. A similar positive correlation was observed in the 28-day compressive strength which highlights that the workability affects the early strength and continues to impact the long-term strength development of concrete. Therefore, adequate workability ensures proper compaction, reduced void content, and enhanced bonding between the paste and aggregate particles which contribute to strength development.

However, it is important to maintain a balance, as excessively high slump may lead to segregation and bleeding which compromises the structural strength of concrete. However, the R² value for the 28 days of the compressive and strength regression model is 0.79 and 0.56, respectively, which are lower than the corresponding values of 0.81 and 0.91 observed at 7 days. The difference is due to the fact that the slump effectively represents the workability of fresh concrete and strongly influences early-age strength development. The compressive strength at later ages is governed by various factors such as ongoing cement hydration, pozzolanic reactions of CDWP and TWP, curing conditions, and microstructural. These factors introduce additional variability that is not captured by slump flow. Therefore, the lower R² at 28 days reflects the more complex strength development over time and demonstrates that although workability remains important, several other factors, such as ongoing cement hydration, pozzolanic reactions of CDWP and TWP, curing conditions, and microstructure, also influence long-term mechanical performance.

Figure 10 illustrates the correlation between fresh density and compressive and tensile strengths at 7 and 28 days for concrete mixes made with CDWP and TWP. Two linear regression models were developed to quantify the relationship for both curing ages. The findings reveal a positive correlation between fresh density and both compressive and tensile strengths, which indicates that higher fresh density improves concrete mechanical performance.

The increased density enhances the compaction of the concrete mix, reducing internal voids and improving the packing of aggregates and cement paste, which significantly contributes to strength development. For the 7 and 28 days compressive and tensile strengths, the linear regression equations are:

The equations indicate a very strong linear correlation between fresh density and concrete strength, with the R² values greater than 90% for both 7 and 28 days. Therefore, the fresh density remains a significant predictor of mechanical performance over time. The increasing fresh density improves concrete compaction, reduces void content, and enhances the bond between cement paste and aggregates which significantly contributes to both compressive and tensile strength. Also, other factors such as ongoing cement hydration, the pozzolanic activity of CDWP and TWP, curing conditions, and microstructural influence long-term performance. Therefore, maintaining optimal fresh density and adequate workability ensures proper compaction and mechanical strength in recycled concrete mixes.

Microstructure analysis

Scanning electronic microscopy (SEM)

Figure 11 shows the SEM results of reference concrete (C0T0) at different magnifications, which consists of 100% ordinary Portland cement and natural aggregate. The control mix serves as a reference specimen for comparison with modified mixes that are made with CDWP as cement replacement and TWP as sand. Despite being a control mix, the SEM images reveal the presence of voids, ITZ, and microcracks. These voids reduce the bulk density of the concrete and serve as stress concentration points that can initiate microcracking under load and compromise mechanical performance. Furthermore, the ITZ typically contains higher concentrations of calcium hydroxide (portlandite) and ettringite crystals, as well as microvoids and unhydrated cement particles. The region is more porous than the bulk paste due to the bleeding of water towards the aggregate. Although the ITZ in the C0T0 mix appears relatively thin, it remains a microstructurally weak zone in concrete that affects mechanical and durability properties. A strong and dense ITZ is essential for effective load transfer between the cement paste and aggregates. Therefore, the ITZ C0T0 mix displays moderate porosity, suggesting adequate (not optimal) packing and bonding.

The microcracks are primarily attributed to drying shrinkage, in which free water evaporates from the paste and the cement matrix undergoes volumetric contraction. Although these cracks are not structurally critical at the micro level, their accumulation and propagation over time, especially under loading or environmental exposure, can contribute to decreased load carry capacity. Despite the presence of voids and microcracks, the microstructure of the reference concrete appears to be well consolidated. The hydration products, particularly CSH gel, are densely distributed in the bulk paste. The relatively dense matrix and thin ITZ indicate a stable microstructure that gives satisfactory strength.

Figure 12 shows the SEM results of concrete made with 5% CDWP as cement replacement and 10% TWP as sand. The findings indicate a dense microstructure with minimal porosity as compared to the reference concrete, indicating more efficient hydration. The improvement can be attributed to the pozzolanic reactivity of the CDWP and the micro filler effect of both CDWP and TWP. The pozzolanic reaction involves the chemical reaction of silica present in CDWP and calcium hydroxide (portlandite) formed during cement hydration. The reaction leads to the formation of an additional CSH gel. The CSH gel improves the binding properties and contributes to strength and microstructure. Also, the fine particle size and angular morphology of CDWP and TWP contribute to the micro filling of voids which leads to improved particle packing and reduced capillary pore volume. The densification of the matrix improves the interconnectivity which leads to better mechanical interlocking and stress distribution within the cementitious mix. A study35 also indicates that the pore structure analysis indicates that the addition of micro ceramic powder (MCP) refines the pore network due to its physical filling effect and pozzolanic reactivity. Therefore, the modified mix shows improved compressive strength with partial replacement of conventional materials.

However, the SEM images also show narrow hairline cracks due to shrinkage or thermal stresses during hydration. The crack is narrow and not interconnected. Therefore, it does not significantly affect the concrete strength. More importantly, the mix does not show any large cracks which are often indicative of poor compaction or the presence of unhydrated particles. The concrete is well-compacted, and the cement particles have effectively hydrated to form CSH gel. The high density and low porosity contribute significantly to the concrete’s strength. The compact nature of the microstructure allows for better stress distribution, enhancing the concrete’s mechanical properties. Moreover, the ITZ appears well-bonded. The improved ITZ can be attributed to both the pozzolanic activity and the micro filler effect which enhances the continuity and density of the matrix at the aggregate interface. Therefore, the dense and strong bond between the particles contributes to the strength and makes it a highly effective construction material.

Figure 13 shows the SEM results of concrete made with 10% CDWP and 20% TWP. The findings indicate a dense microstructure with minimal porosity as compared to the reference concrete. Therefore, the hydration process appears effective even with the replacement of 10% cement with CDWP. The formation of abundant CSH gel due to pozzolanic reaction contributes to the concrete strength. Furthermore, a well-bonded interfacial ITZ is observed which indicates strong bonding between the cement paste and aggregate particles. The strong ITZ facilitates efficient load transfer across the cement aggregate interface and minimizes stress concentration. Therefore, the strength of concrete is improved (Figs. 7 and 8). Furthermore, the SEM images show no apparent larger number of voids or microcracks at the ITZ which reflects good particle packing and paste-aggregate bonding despite the 10% CDPW and 20% TWP. However, the presence of a slightly porous region was noted within the bulk matrix. The porosity may be attributed to a reduction in workability caused by the increased volume of fine recycled powders.

Furthermore, the higher surface area and angularity of CDWP and TWP particles tend to increase the water demand of the mix. Therefore, the lack of water potentially leads to incomplete compaction and entrapped air voids. Also, the reduced workability can obstruct during placing and compaction which results in small pockets of porosity. However, the overall microstructure remains dense and strong. The pozzolanic activity of CDWP and the micro filler effect of TWP contribute to the refinement of the pore structure and enhancement of the ITZ. A study36 noted that the mix made with ceramic waste as a sand replacement shows a strong ITZ due to the micro-filler effect. The mechanisms work synergistically to offset the potential negative effects of increased percentages of waste materials. The mix represents a viable, sustainable alternative to conventional concrete which balances the recycled material usage with mechanical strength.

Figure 14 shows the SEM results of concrete made with 15% CDWP as cement replacement and 30% TWP as sand. The findings reveal the presence of numerous voids, porous regions, and micro-cracks throughout the cement matrix. Compared to mixes with lower replacement levels (C5T10 and C10T20), the increase to 15% CDWP and 30% TWP has resulted in a noticeable deterioration of the microstructure. The voids indicate incomplete compaction and increased entrapped air due to reduced workability (Fig. 5). The irregular shapes and higher surface area of CDWP and TWP particles demand more mixing water and can disrupt the flowability of the concrete which leads to inefficient compaction and the formation of voids. The voids act as stress concentrators and weaken the load carrying capacity. Additionally, the presence of porous regions suggests a less dense microstructure due to higher percentages of cement replacement. The reduced availability of reactive cementitious material and the potential for incomplete hydration can lead to a pore structure and higher porosity which negatively impact the concrete’s mechanical strength.

The SEM analysis also reveals a network of large cracks due to poor workability and non-reactive particles. The poor workability makes it difficult to achieve better compaction and during placement. The poor compaction results in entrapped air pockets, voids, and heterogeneous zones where the paste fails to fully envelop the aggregates and filler particles. A study37 also indicates that poor workability negatively impacts the performance, application, and final quality of concrete during setting and finishing. Furthermore, an increase in concrete porosity leads to lower density and poorer compaction, resulting in a decrease in compressive strength. Furthermore, the non-reactive particles do not contribute to the hydration process. Therefore, it does not generate binding compounds such as CSH that provide strength and cohesion which results in cracks. The insufficient compaction and the inert nature of some particles induce internal stresses. The stresses lead to the formation and propagation of large cracks within the microstructure. A study38 indicates that the microstructural configuration of recycled powder increases the water demand and adversely affects the workability of concrete. Similarly, the SEM analysis of construction and demolition waste (CDW) aggregates reveals that CDW particles are generally more angular compared to natural aggregates, which contributes to a reduction in the workability of concrete39. Therefore, the mix made with 15% CDWP and 30% TWP shows lower strength as compared to the other mixes (Figs. 7 and 8).

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

The FTIR spectra (Fig. 15) illustrate the transmittance behavior of concrete made with varying proportions of CDWP and TWP as partial replacements for cement and fine aggregate, respectively. The findings indicate that significant changes in transmittance are observed, particularly for the sample with 5% CDWP and 10% TWP (C5T10). A lower transmittance value compared to the control and other mixes, indicating a higher degree of absorption likely due to increased chemical interactions and bond formations within the matrix. However, the samples with higher CDWP and TWP percentages (C10T20 and C15T30) exhibit transmittance closer to the control. The results are consistent with a previous study40 which indicates that the peaks corresponding to Si-O stretching vibrations in the 900 to 1000 cm− 1 range show minimal changes, indicating stable polymerization. A study41 also reported that the CSH peak for OPC was identified around 970 cm⁻¹, indicating the asymmetric stretching vibrations of Si-O-Si bonds. Furthermore, when nano silica (NS) was added along with metakaolin (MK), the peak shifted from 974 cm⁻¹ to 1002 cm⁻¹, suggesting a broadening of the Si-O band.

Therefore, the shift indicates an increase in the degree of silicate polymerization due to the formation of a silica (SiO2) gel. A study41 indicates that the bands appearing in the 1400 to 1500 cm− 1 range are attributed to carbonate vibrations. The broad OH stretching peak (3400 cm− 1) variations suggest different moisture content or hydration degrees in mixes. A study42 also noted that the broad absorption band at higher wavenumbers is attributed to two types of water. One associated with gypsum at around 3550 cm⁻¹, and the other linked to water bound within the cement matrix near 3428 cm− 1 during the hydration process. Therefore, the optimum replacement levels (5% CDWP and 10% TWP) have a more pronounced impact on the molecular interactions within the cement matrix, especially in the Si-O stretching region. The modifications suggest enhanced chemical reactions and potential improvements in the silicate polymerization process, which contribute to the development of a denser and more durable microstructure (Fig. 12). However, higher substitution percentages tend to bring transmittance values closer to those of the control mix, indicating that excessive replacement reduces the chemical effects. Therefore, the CDWP and TWP optimum percentages show promise for sustainable concrete production by partially utilizing CDWP and TWP without compromising the concrete performance.

Limitations and impact

-

The CDWP and TWP used were obtained locally. Their chemical composition, porosity, and reactivity can differ from other demolition or ceramic sources, which impact the concrete performance.

-

Reduced workability at higher replacement levels can cause poor compaction and extra voids which resulting in lower strength.

-

One water-to-cement ratio (0.60) was used in this study. Different ratios could change the optimum replacement levels and improve performance at higher substitutions.

-

Long-term strength development and durability properties such as resistance to chloride penetration, sulfate attack, carbonation, and freeze thaw cycles, were not evaluated.

The limitations indicate that the findings are reliable within the scope of this study, but further laboratory and practical tests are required to confirm their applicability under different materials source, mix designs, and durability conditions.

Conclusions

In this study, the cement was partially replaced with CDWP in varying percentages from 0%, 5%, 10% and 15%. Furthermore, the fine aggregate was partially replaced with TWP in varying percentages from 0%, 10%, 20% and 30%. The fresh properties (slump flow and fresh density) and mechanical properties (compressive and tensile strength) were evaluated. Furthermore, correlations between fresh and mechanical properties were developed. Also details microstructure analysis was performed through SEM and FTIR analysis. The detailed conclusions are as follows:

-

The concrete workability is reduced due to the rough and angular nature of CDWP and TWP particles.

-

The CDWP and TWP improve fresh concrete density due to better particle packing and reduced voids. However, higher replacement levels decrease density due to reduced workability and poor compaction which leads to more entrapped air.

-

The partial replacement of cement and fine aggregate with CDWP and TWP can enhance the compressive strength of concrete at lower substitution levels (5% CDWP and 10% TWP) due to pozzolanic activity and improved interfacial transition zone. However, higher replacement levels adversely affect strength.

-

Splitting tensile strength also increased in a similar pattern to compressive strength due to pozzolanic activity, improved microstructure, and mechanical interlocking. However, higher replacement levels reduce tensile strength.

-

Slump flow shows a strong correlation with early-age concrete strength which highlights the importance of workability for compaction and mechanical performance. However, its influence decreases at 28 days due to additional factors like hydration, curing, and pozzolanic reactions. Furthermore, fresh density shows a strong positive correlation with both compressive and tensile strengths at 7 and 28 days, indicating that higher density significantly enhances mechanical performance by improving particle packing and reducing voids.

-

The SEM findings align well with the mechanical strength results, confirming that improved microstructure is observed at lower replacement levels and weak microstructure at higher replacement levels.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the manuscript.

References

Ahmad, F., Qureshi, M. I., Rawat, S., Alkharisi, M. K. & Alturki, M. E-waste in concrete construction: recycling, applications, and impact on mechanical, durability, and thermal properties—a review. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 10, 246 (2025).

Alogla, S. M. & Almusayrie, A. I. Compressive strength evaluation of concrete with palm tree Ash. Civ. Eng. Archit. 10, 725–733 (2022).

Abbas, M. M. Recycling waste materials in construction: mechanical properties and predictive modeling of waste-Derived cement substitutes. waste Manag. Bull 3, 168–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wmb.2025.01.004 (2025).

Tanash, A. O. et al. A review on the utilization of ceramic tile waste as cement and aggregates replacement in cement based composite and a bibliometric assessment. Clean. Eng. Technol. 17, 100699 (2023).

Mangi, S. A., Raza, M. S., Khahro, S. H., Qureshi, A. S. & Kumar, R. Recycling of ceramic tiles waste and marble waste in sustainable production of concrete: a review. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 29, 18311–18332. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-18105-x (2022).

Mawashee, R. S. A., Shhatha, M. A. A. & Alatiya, Q. A. J. Waste ceramic as partial replacement for sand in integral waterproof concrete: the durability against sulfate attack of certain properties. Open. Eng. 13, 20220455 (2023).

Sakthibala, R. K., Vasanthi, P., Hariharasudhan, C. & Partheeban, P. A critical review on recycling and reuse of construction and demolition waste materials. Clean. Waste Syst. 12, 100375 (2025).

Bommisetty, J., Keertan, T. S., Ravitheja, A. & Mahendra, K. Effect of waste ceramic tiles as a partial replacement of aggregates in concrete. Mater. Today Proc. 19, 875–877 (2019).

Nasir, A., Butt, F. & Ahmad, F. Enhanced mechanical and axial resilience of recycled plastic aggregate concrete reinforced with silica fume and fibers. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 10, 4 (2025).

Li, L. et al. Microstructure and transport properties of cement mortar made with recycled fine ceramic aggregates, Dev. Built Environ. 22, 100643 (2025).

Paul, S. C., Faruky, S. A. U., Babafemi, A. J. & Miah, M. J. Eco-friendly concrete with waste ceramic tile as coarse aggregate: mechanical strength, durability, and microstructural properties. Asian J. Civ. Eng. 24, 3363–3373 (2023).

Sivakumar, A., Srividhya, S., Sathiyamoorthy, V., Seenivasan, M. & Subbarayan, M. R. Impact of waste ceramic tiles as partial replacement of fine and coarse aggregate in concrete. Mater. Today Proc. 61, 224–231 (2022).

Basak, S., Haque, M. R., Azad, A. K. & Rahman, M. M. Performance of ceramic tiles waste as a partial replacement of brick aggregate on mechanical and durability properties of concrete. J. Eng. Adv. 5, 9–13 (2024).

Adekunle, A. A., Abimbola, K. R. & Familusi, A. O. Utilization of construction waste tiles as a replacement for fine aggregates in concrete. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 7, 1930–1933 (2017).

Yahya, N. et al. Mechanical and rheological properties of concrete with ceramic tile waste as partial replacement of fine aggregate, in: IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng., IOP Publishing, 12033 (2020).

Anderson, D. J., Smith, S. T. & Au, F. T. K. Mechanical properties of concrete utilising waste ceramic as coarse aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 117, 20–28 (2016).

Suchithra, S., Sowmiya, M. & Pavithran, T. Effect of ceramic tile waste on strength parameters of concrete-a review, Mater. Today Proc. 65, 975–982. (2022).

Ikponmwosa, E. E. & Ehikhuenmen, S. O. The effect of ceramic waste as coarse aggregate on strength properties of concrete. Niger J. Technol. 36, 691–696 (2017).

Kumar, S., Murthi, P., Awoyera, P., Gobinath, R. & Kumar, S. Impact resistance and strength development of fly Ash based Self-compacting concrete. Silicon 14, 481–492. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12633-020-00842-2 (2022).

Wu, W., Wang, R., Zhu, C. & Meng, Q. The effect of fly Ash and silica fume on mechanical properties and durability of coral aggregate concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 185, 69–78 (2018).

Manivel, S., Prakash Chandar, S. & Nepal, S. Effect of glass powder on compressive strength and flexural strength of cement mortar. Int. J. Civ. Eng. Technol. 8, 855–861 (2017).

Lee, W. H., Lin, K. L., Chang, T. H., Ding, Y. C. & Cheng, T. W. Sustainable development and performance evaluation of marble-waste-based geopolymer concrete. Polym. (Basel). 12, 1924 (2020).

Sheen, Y. N., Le, D. H. & Sun, T. H. Innovative usages of stainless steel slags in developing self-compacting concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 101, 268–276 (2015).

Antony, J. & Nair, D. G. Potential of construction and demolished wastes as Pozzolana. Procedia Technol. 25, 194–200 (2016).

Haroon, M., Khan, R. B. N. & Khitab, A. Performance of concrete containing waste demolished concrete powder as a partial substitute for cement. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 43, 573–590 (2025).

Xiao, J., Ma, Z., Sui, T., Akbarnezhad, A. & Duan, Z. Mechanical properties of concrete mixed with recycled powder produced from construction and demolition waste. J. Clean. Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.03.277 (2018).

de Lima, D. O., de Lira, D. S., Rojas, M. F. & Junior, H. S. Assessment of the potential use of construction and demolition waste (CDW) fines as eco-pozzolan in binary and ternary cements. Constr. Build. Mater. 411, 134320 (2024).

ASTM, ASTM C143/C143M-12 Standard Test Method for Slump of Hydraulic-Cement Concrete, Annu. B. ASTM Stand. (2015).

A. C39/C39M, Standard test method for compressive strength of cylindrical concrete specimens, Annu. B. ASTM Stand. (2003).

C496/C496M, Standard Test Method for Splitting Tensile Strength of Cylindrical Concrete Specimens1, Man. Hydrocarb. Anal. 6th Ed. 545-545-3. (2008).

Govindarajalu, E. & Ganapathy, G. P. Reuse of ceramic waste in concrete production for a sustainable ecosystem. Matéria (Rio Janeiro). 29, e20240325 (2024).

Li, L. G., Chen, J. J. & Kwan, A. K. H. Roles of packing density and water film thickness in strength and durability of limestone fines concrete. Mag Concr Res. 69, 595–605 (2017).

Gayathiri, K. & Praveenkumar, S. Retaining the particle packing approach and its application in developing the cement composites towards sustainability. J. Build. Pathol. Rehabil. 8, 26 (2023).

Yu, P., Li, T. & Gao, S. Study on the effect of recycled fine powder on the properties of cement mortar and concrete, desalin. Water Treat. 319, 100481 (2024).

Li, L., Liu, W., You, Q., Chen, M. & Zeng, Q. Waste ceramic powder as a pozzolanic supplementary filler of cement for developing sustainable Building materials. J. Clean. Prod. 259, 120853 (2020).

Fatima, B., Batool, F. & Sangi, A. J. Experimental investigation on the use of ceramic tiles as aggregates in concrete. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 10, 1–16 (2025).

Mehta, V. Sustainable approaches in concrete production: an in-depth review of waste foundry sand utilization and environmental considerations. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 31, 23435–23461 (2024).

Liu, Q., Tong, T., Liu, S., Yang, D. & Yu, Q. Investigation of using hybrid recycled powder from demolished concrete solids and clay bricks as a pozzolanic supplement for cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 73, 754–763 (2014).

Mucsi, G., Halyag Papné, N., Ulsen, C., Figueiredo, P. O. & Kristály, F. Mechanical activation of construction and demolition waste in order to improve its pozzolanic reactivity. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 9, 3416–3427 (2021).

Bhat, P. A. & Debnath, N. C. Study of structures and properties of silica-based clusters and its application to modeling of nanostructures of cement paste by DFT methods, in: IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng., IOP Publishing, 12001 (2013).

Jamsheer, A. F., Kupwade-Patil, K., Büyüköztürk, O. & Bumajdad, A. Analysis of engineered cement paste using silica nanoparticles and Metakaolin using 29Si NMR, water adsorption and synchrotron X-ray diffraction. Constr. Build. Mater. 180, 698–709 (2018).

Amado-Fierro, Á., Sierra, A. L. M., Fernandez-Gonzalez, A. & Centeno, T. A. Approach to hydrochar as a partial cement substitute in mortars, case stud. Constr. Mater. 22, e04829 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The author extends the appreciation to the Deanship of Postgraduate Studies and Scientific Research at Majmaah University for funding this research work through the project number (ER-2025–2160).

Funding

This work does not received external fundings.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.A. (Abdullah Alzlfawi) was responsible for writing the original draft and developing the methodology. W.A. (Wael Alattyih) contributed to the conceptual design, review editing, and manuscript revision. M.T.N. (M. Tayyab Naqash) performed the statistical analysis, prepared the figures, and participated in review editing and revisions. J.A. (Jawad Ahmad) supervised the project, contributed to review editing and revisions, and finalized the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alzlfawi, A., Alattyih, W., Naqash, M.T. et al. Properties of sustainable concrete containing demolished concrete and tile waste powders. Sci Rep 16, 787 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30348-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30348-z