Abstract

We derive fast protocols for charging a three-qubit Ising spin-chain quantum battery, using amplitude and phase control of the global transverse field. For weak coupling between the qubits in the chain, where the initial ground state of the system is the spin-down state, we find that the optimal strategy is to fix the control amplitude at its maximum value while properly varying the phase with time. For the strong coupling case, where the initial ground state is the one-excitation Dicke state \(\vert {W} \rangle\), we apply two related charging protocols. In the first approach we use a pulse-sequence derived numerically in the recent work (Stojanović and Nauth in Phys Rev A 108:012608, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.108.012608), composed of delta Bang pulses and intervals where the control is switched off. We call this method fast charging via subspace decomposition, since it involves identifying and manipulating effective two-level subsystems. Here we find analytically the characteristics of the pulses composing the sequence, which were calculated numerically in the above reference. In the second approach, we apply a similar pulse-sequence with delta Bang pulses and Off intervals, but with a carrier frequency which brings on resonance the initial \(\vert {W} \rangle\) state and the target spin-up state of maximum energy. We call this method charging via resonant excitation. We calculate numerically the characteristics of the pulses in the sequence and find a shorter charging time compared to the non-resonant method inspired by the above reference. We also use numerical optimal control to solve the problem of full charging the quantum battery but for finite values of the control amplitude and find that, for some relatively large values of this bound, the optimal solution has similar structure with the sequence incorporating delta Bang pulses but longer duration, as expected. Although this study focuses on a three-spin chain, the proposed methodology can be also extended to larger spin-chains. The lowest and highest energy eigenstates need to be identified first, serving as the initial and target states. Then, optimal control can be exploited to find the amplitude and phase modulation of a field resonant to this transition, which maximize the stored energy in the battery for a given duration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantum batteries (QBs)1,2 have emerged as a significant research frontier in quantum technology, offering the prospect of energy storage devices that surpass their classical counterparts at microscopic scales. This potential for superior performance in energy storage and retrieval is rooted in distinctly quantum mechanical principles, including superposition and entanglement2, a concept supported by extensive theoretical work3,4,5,6,7. A broad spectrum of QB models has been put forward, from fundamental few-level systems to complex many-body constructions like spin chains, quantum oscillators, and interacting frameworks such as the Su–Schrieffer–Heeger and Sachdev–Ye–Kitaev models8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60. In parallel, experimental efforts are materializing QB prototypes across diverse platforms like superconductors39,54, quantum dots40, organic microcavities41, and nuclear spin systems31.

Maximizing the energy stored in a QB hinges on the critical task of designing effective charging protocols. To this end, researchers have investigated a wide array of quantum control techniques to address this challenge61. Simple pulsed protocols have been used for two-level QBs20 and harmonic oscillator QBs25. Methods such as stimulated Raman adiabatic passage (STIRAP)62,63 have been applied to charge three-level QBs in both open12 and closed42 environments. Adiabatic passage has likewise been adapted for systems of non-interacting qubits15. To accelerate charging, protocols derived from shortcuts to adiabaticity64 have been broadly applied, from simple few-level systems43,44 to more elaborate ones like the Ising chain45 and the Lipkin–Meshkov–Glick model46. The quantum adiabatic brachistochrone method, a related approach, has been realized experimentally in superconducting qutrit QBs39. Additionally, strong-pulse protocols have demonstrated rapid charging in many-body QBs47, while the quantum speed limit formalism has refined the theoretical bounds on charging times65,66. Optimal control theory67,68,69,70,71 has recently proven to be a particularly effective tool for determining the ideal driving fields for qubit-based QBs49,50 and coupled oscillator systems51. Other sophisticated approaches like reinforcement learning have been used to successfully charge Dicke52 and cavity-Heisenberg spin-chain QBs53. These developments highlight how essential advanced control strategies72,73 are for realizing the full potential of QB technologies.

In a preceding work74, we analyzed a QB model consisting of two spin-1/2 particles governed by an Ising interaction, with control exerted through the amplitude and phase of a transverse field in the presence of a static longitudinal field. Our findings revealed that the charging dynamics depend crucially on the relative strengths of the Ising coupling, J, and the longitudinal field, \(\Omega _z\). Two distinct operational regimes were identified. For weak coupling (\(J<\Omega _z\)), where the initial ground state of the system is the spin-down state, the fastest charging is achieved by applying the transverse field at its maximum available strength with a properly modulated phase, allowing the minimum charging time to approach zero as this control bound increases. For strong coupling (\(J>\Omega _z\)), where the initial ground state is a maximally entangled Bell state, the time-optimal protocol is structurally different, incorporating a “singular arc” where the transverse control is switched off and the phase is immaterial. This feature imposes a finite, non-zero lower limit on the charging time even for large values of the maximum control amplitude, which time is inversely proportional to the Ising coupling strength.

The present work builds upon this foundation, extending our analysis to a more complex and scalable architecture: a three-qubit (N = 3) spin chain. This progression enables us to examine the scalability of the control schemes and reveal new dynamical features specific to a three-body interacting system. For weak coupling, where the initial ground state of the system is the spin down state, we find similarly to the spin-pair case that the optimal strategy is to keep the control amplitude fixed at its maximum value while properly varying with time the phase. Again, the full charging duration tends to zero as the maximum control amplitude increases. For the strong coupling case, where the initial ground state is now the one-excitation Dicke state \(\vert {W} \rangle\), the heightened complexity of the three-qubit Hilbert space demands a more sophisticated control methodology. We therefore investigate two distinct charging strategies. The first approach is based on a recent work for fast Dicke state preparation through global transverse control of Ising coupled qubits75. We call this method fast charging via subspace decomposition, since it involves identifying and manipulating effective two-level subsystems. Via this methodology, a pulse sequence of the form Bang-Off-Bang-Off-Bang accomplishing the desired state transfer is obtained in Ref.75. Here, the term “Bang pulse” refers to a pulse equal to the maximum control amplitude. The sequence in Ref.75 is composed of delta Bang pulses, with very high amplitude relative to the interaction and negligible duration, also known as “delta kicks” in the literature, and intervals where the transverse control is switched off and the system evolves only under the Ising interaction, the “Off” pulses. The rotation angles and phases of the Bang pulses and the durations of the Off pulses are calculated numerically in Ref.75. Here we use this pulse sequence for the fast charging of our QB, while we also explain how the pulse characteristics of the sequence can be derived analytically. Although this method accomplishes the transfer between the \(\vert {W} \rangle\) and the highest energy spin-up state, the corresponding framework arises when the carrier frequency of the applied control field is tuned to the transition from the spin-down to the spin-up state. In the second methodology we combine a control field resonant to the transition from the initial \(\vert {W} \rangle\) to the target spin-up state with a Bang-Off-Bang-Off-Bang pulse-sequence inspired from Ref.75; we call this approach charging via resonant excitation. We calculate numerically the characteristics of the pulses in the sequence and find a shorter charging time for the QB, compared to the previous non-resonant method motivated by the work in Ref.75. Then, we use numerical optimal control to solve the problem of full charging the QB for several finite values of the maximum control amplitude. We find that, for some relatively large values of this bound, the Bang-Off-Bang-Off-Bang sequence arises as the optimal solution, where now the Bang pulses have finite height. Of course, the times needed for full charging with finite control amplitude are longer than the limit obtained with delta Bang pulses. Although the present study centers around a three-spin chain, the proposed technique can be also applied to larger spin-chains in the following way: the lowest and highest energy eigenstates are identified first, serving as the initial and target states. Then, a field resonant to this transition is used to drive the QB, and optimal control is exploited to find its amplitude and phase modulation which maximize the stored energy in the QB for a given duration.

This article is organized as follows. In “Optimal charging of an Ising N-qubit quantum battery” section is introduced the three-qubit QB model and framed the charging process as a problem of optimal control. In “Case \(J<\Omega _z/2\)” and “Case \(J>\Omega _z/2\)” sections are derived optimal charging protocols for the weak and strong Ising coupling regimes, respectively. Specifically, “Case \(J>\Omega _z/2\)” section provides a detailed analysis of two charging strategies: via subspace decomposition and through resonant excitation. In “Discussion” section are further discussed the obtained results while the paper concludes in “Conclusions” section.

Optimal charging of an Ising N-qubit quantum battery

Consider an Ising spin-chain with N spins-1/2 in the standard NMR framework, consisting of a constant longitudinal magnetic field \(\Omega _z\) and time-dependent transverse fields \(\Omega _x(t), \Omega _y(t)\) acting as the control functions, described by the Hamiltonian (\(\hbar =1\))75

with

where J is the Ising interaction. The system is schematically illustared in Fig. 1 for \(N = 3\).

Schematic illustration of the QB and the charging protocols. (a) A three-spin Ising chain with coupling J, driven by a global transverse field with bounded amplitude \(0\le \Omega (t) \le \Omega _0\) and phase \(\phi (t)\). (b,c) Representative charging protocol for weak and strong coupling, where note the different initial state in each case.

Charging of this quantum battery corresponds to transferring population from the initial state \(\vert {\psi (0)} \rangle\), which is usually taken to be the ground state, to the excited states such that at the final time T the stored energy is maximized

We consider transverse control fields with time-varying amplitude \(\Omega (t)\) and phase \(\phi (t)\),

while \(\omega _c\) denotes the carrier frequency. We impose an upper bound \(\Omega _0\) on the control amplitude

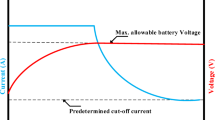

and under this restriction we find \(\Omega (t), \phi (t)\) maximizing the stored energy (3) for a given duration T. As we increase T, the achieved stored energy also increases, until its maximum possible value is reached. We refer to this situation as full charging, and the corresponding duration is the minimum time for full charging.

In this work we concentrate on a spin-chain with \(N=3\) qubits. In this case, Hamiltonian \(\hat{H}_1\) couples only the states

where note that \(\vert {0} \rangle =(0 \; 1)^T, \vert {1} \rangle =(1 \; 0)^T\) are the individual spin-down and spin-up states, respectively. Let

be the representation of the system state on this restricted manifold, with \(c_i, i=0, 1, 2, 3\), the corresponding probability amplitudes. The Schrödinger evolution under Hamiltonian (1) leads to the system

for the state vector \(\vert {\psi (t)} \rangle =[c_0(t), c_1(t), c_2(t), c_3(t)]^T\), where we have also used Eq. (4).

To formulate the optimal control problem of maximizing the stored energy (3), we use Schrödinger equation (8) as state equation and denote with \(\vert {\lambda (t)} \rangle =[\lambda _0(t), \lambda _1(t), \lambda _2(t), \lambda _3(t)]^T\) the corresponding adjoint ket state. By applying the optimal control formalism for quantum systems76, we get the control Hamiltonian

where \(A, B \in {\mathbb {R}}\) depend on \(\vert {\psi } \rangle , \vert {\lambda } \rangle\) and the off-diagonal elements of the matrix in Eq. (8), \(C\in {\mathbb {R}}\) depends on \(\vert {\psi } \rangle , \vert {\lambda } \rangle\) and the diagonal elements of the same matrix, while \(\Re , \Im\) denote real and imaginary parts, respectively. If we define the derivative with respect to \(\vert { \psi } \rangle\) as

then \(\vert {\psi } \rangle , \vert {\lambda } \rangle\) satisfy the pair of Hamilton’s equation

where H denotes the matrix in Eq. (8). Note that the first equation is actually Schrödinger Eq. (8) as expected, while the second one leads to a similar equation for \(\langle {\lambda }\vert\). The adjoint variables should also satisfy the terminal condition

which connects the final adjoint state with the final state \(\vert {\psi (T)} \rangle\) because of Eq. (3), defining thus a two-point boundary value problem.

Pontryagin’s maximum principle67,68 states that the optimal controls \(\Omega ^*(t), \phi ^*(t)\) should be chosen to maximize the control Hamiltonian (9). Given that \(\phi\) is unrestricted, for \(\Omega (t)\ne 0\) it is

which leads to

Observe from Eq. (14) that if either \(A\ne 0\) or \(B\ne 0\) then the optimal control amplitude maximizing \(H_c\) is \(\Omega ^*(t)=\Omega _0\). When \(A=B=0\) for a finite duration then maximum principle provides a priori no information about the optimal \(\Omega\). In this situation \(\Omega ^*\) can take any value in the interval \([0, \Omega _0]\) and the corresponding optimal control is called singular. Special consideration require the time intervals for which \(\Omega ^*(t)=0\), where the phase is immaterial. As we will see below, for the problem at hand numerical optimization indicates that the optimal amplitude take the boundary values 0 and \(\Omega _0\), at least for the examples considered here. We use the numerical optimal control solver of Ref.77, which does not need to formulate the two-point boundary value problem from scratch, just code the dynamics correctly and define the cost function to be maximized, here the stored energy. The program terminates when an optimal solution is found, according to its termination criteria.

From Eq. (3) we see that the stored energy also depends on the initial state \(\vert {\psi (0)} \rangle\), usually taken to be the ground state. From Eq. (2a) for the QB Hamiltonian \(\hat{H}_0\) we easily find that the energies of the states \(\vert {\psi _i} \rangle\), \(i = 0, 1, 2, 3\), are \(E_0 = 3(J - \Omega _z)\), \(E_1 = -(J+\Omega _z)\), \(E_2 = \Omega _z - J\), \(E_3 = 3(J + \Omega _z)\). Thus which one is the ground state of the battery depends on the ratio

Based on this observation we need to distinguish two cases. Representative charging protocols for both cases are schematically illustrated in Fig. 1.

Case \(J<\Omega _z/2\)

In this case, the ground state is the spin-down state \(\vert {\psi _0} \rangle\). Using it as the initial state \(\vert {\psi (0)} \rangle =\vert {\psi _0} \rangle\) in Eq. (3), we obtain the following expression for the stored energy in terms of the final populations of the states with at least one excitation

where \(\chi =J/\Omega _z<1/2\) and for the closed system under study we have used \(\left| c_0(T)\right| ^2\) = \(1 - \left| c_1(T)\right| ^2\) − \(\left| c_2(T)\right| ^2 - \left| c_3(T)\right| ^2\). The maximum stored energy is \(\Delta E_{max}=6\Omega _z\).

We would like starting from state \(\vert {\psi _0} \rangle\) to maximize the stored energy and since the spin-up state \(\vert {\psi _3} \rangle\) has the highest energy we choose the carrier frequency in Eq. (8) as \(\omega _c= 2 \Omega _z\) to bring them on resonance, ending up with the equation

We use numerical optimal control to solve the problem of fully charging a quantum battery with ratio \(\chi =J/\Omega _z=1/4\), for three values of the maximum control amplitude \(\Omega _0/\Omega _z = 1, 1.5, 5\). The results are displayed in Figs. 2, 3 and 4, respectively, where for each case we plot the optimal control amplitude and phase, as well as the time evolution of charging energy and state populations. Observe that for all cases the optimal control amplitude is constant throughout the whole time interval. Further numerical simulations support that this is a general characteristic of the optimal control for the case under study, independent of the maximum control amplitude \(\Omega _0\). A similar behavior has also been observed in the time-optimal control of two- and three-qubit gates for Rydberg atoms78. The optimal phase on the other hand is time-dependent, with a steeper variation for the smaller control amplitudes \(\Omega _0 = \Omega _z\) and \(\Omega _0 = 1.5\Omega _z\), as shown in Figs. 2b and 3b, and smoother evolution for the larger control amplitude \(\Omega _0 = 5\Omega _z\), as displayed in Fig. 4b. As a consequence, the evolution of stored energy and populations is more wavy in the former cases than in the latter.

In Fig. 5a we plot the minimum necessary time for full charging (black curve) versus the maximum control amplitude \(\Omega _0\). We observe that this duration approaches zero as \(\Omega _0\) increases. This behavior can be understood by considering a delta pulse with amplitude \(\Omega _0\rightarrow \infty\), duration \(T\rightarrow 0\) and constant phase \(\phi\). Then, the J-term in Eq. (17) can be neglected and we get the solution

If the pulse area is selected as \(\Omega _0T=\pi /2\), then \(|c_3(T)|=1\) and the battery is fully charged within \(T\rightarrow 0\). In Fig. 5b we also plot the average charging power versus \(\Omega _0\) (black curve).

Optimal control amplitude (a) and phase (b), along with the corresponding time evolution of stored energy (c) and populations (\(|c_0|^2\) black, \(|c_1|^2\) red, \(|c_2|^2\) green, \(|c_3|^2\) blue) (d) for full charging in minimum time, when \(\Omega _0/\Omega _z=1\) and \(\chi =J/\Omega _z=1/4\).

Optimal control amplitude (a) and phase (b), along with the corresponding time evolution of stored energy (c) and populations (\(|c_0|^2\) black, \(|c_1|^2\) red, \(|c_2|^2\) green, \(|c_3|^2\) blue) (d) for full charging in minimum time, when \(\Omega _0/\Omega _z=1.5\) and \(\chi =J/\Omega _z=1/4\).

Optimal control amplitude (a) and phase (b), along with the corresponding time evolution of stored energy (c) and populations (\(|c_0|^2\) black, \(|c_1|^2\) red, \(|c_2|^2\) green, \(|c_3|^2\) blue) (d) for full charging in minimum time, when \(\Omega _0/\Omega _z=5\) and \(\chi =J/\Omega _z=1/4\).

Case \(J>\Omega _z/2\)

In this case, the ground state is \(\vert {\psi _1} \rangle\). Using it as the initial state \(\vert {\psi (0)} \rangle =\vert {\psi _1} \rangle\) in (3), we obtain the following expression for the stored energy in terms of the final populations of the states with at least one excitation

where \(\chi =J/\Omega _z>1/2\) and for the closed system under study we have used \(\left| c_0(T)\right| ^2\) = \(1 - \left| c_1(T)\right| ^2\) − \(\left| c_2(T)\right| ^2 - \left| c_3(T)\right| ^2\). The maximum stored energy is \(\Delta E_{max}=4(1+\chi ) \Omega _z > 6\Omega _z\), since \(\chi > 1/2\). Thus, the maximum stored energy achieved in the strong coupling case, where the system starts from the entangled state \(\vert {\psi _1} \rangle\), is higher than that obtained for weak coupling, where the starting state is the spin-down state \(\vert {\psi _0} \rangle\). This is obviously a quantum advantage of this type of QB.

The maximization of stored energy is achieved by transferring the total population of the system to the highest energy eigenstate, which is the three-excitation state \(\vert {\psi _3} \rangle\). In “Fast charging via subspace decomposition” section we adopt an analytical approach, inspired by the work of Stojanović et al.75, which leverages the underlying symmetries of system (17) to construct a fast and efficient charging protocol. Note that Eq. (17) is obtained by applying fields with carrier frequency \(\omega _c= 2 \Omega _z\), which brings on resonance states \(\vert {\psi _0} \rangle , \vert {\psi _3} \rangle\). In “Charging via resonant excitation” section we obtain a faster pulse-sequence by using a carrier frequency which brings on resonance the current initial state \(\vert {\psi _1} \rangle\) with the target state \(\vert {\psi _3} \rangle\).

Fast charging via subspace decomposition

We present a method to accomplish the transfer \(\vert {\psi _1} \rangle \rightarrow \vert {\psi _3} \rangle\) in system (17), which is based on the work of Stojanović et al.75. The foundation of this method lies in the decomposition of the 4D subspace, spanned by the basis of excitation number states \(\{\vert {\psi _0} \rangle , \vert {\psi _1} \rangle , \vert {\psi _2} \rangle , \vert {\psi _3} \rangle \}\), into smaller, independent subspaces where the dynamics of Eq. (17) are simpler to analyze. This decomposition is possible because the Ising interaction, expressed by the diagonal part of the matrix in Eq. (17), as well as the x-component of the applied field, expressed by the real part of the off-diagonal elements in the same equation, both commute with the x-parity operator, \(\hat{X}_p = {\hat{\sigma }}_x \otimes {\hat{\sigma }}_x \otimes {\hat{\sigma }}_x\). This operator has two eigenvalues, \(+1\) and \(-1\), and we can define a parity basis, \(\{\vert {v_1} \rangle , \vert {v_2} \rangle , \vert {v_3} \rangle , \vert {v_4} \rangle \}\), where vectors \(\vert {v_1} \rangle , \vert {v_2} \rangle\) span the \(+1\) eigensubspace and \(\vert {v_3} \rangle , \vert {v_4} \rangle\) span the \(-1\) eigensubspace, which is related to the excitation basis by:

In this parity basis, evolution (17) is described by the matrix

where

and

Observe that the Ising part \(H_0\) is diagonal, thus it does not couple the two subspaces, while \(H_1\) becomes block-diagonal when \(\sin {\phi }=0 \rightarrow \phi =0\) or \(\pi\), i.e. the field is along the x-axis:

with the ± sign corresponding to the two opposite phases. A state prepared in one of the subspaces will remain within that subspace for all time under the evolution of operators in Eqs. (22) and (24). This decoupling is the key to simplifying the control problem and forms the core geometric justification for the approach: by confining the evolution to a lower-dimensional invariant subspace, the control path becomes significantly less complex.

The proposed control protocol is structured as a sequence of extremely short, high-amplitude Bang pulses, approximated as Dirac delta-functions, separated by periods of free evolution (Off pulses). The Bangs are global rotational pulses generated by a strong control field \(\Omega (t) = \Omega _0 \gg J\). Their duration is negligible and their function is to rotate the state vector instantaneously. The corresponding propagator is

where the rotation angle \(\theta = \Omega _0 \tau\) is finite and the phase \(\phi\) is constant over the Bang “duration” \(\tau \rightarrow 0\).

In the parity basis, the initial state \(\vert {\psi _1} \rangle\) and the target state \(\vert {\psi _3} \rangle\) are superpositions of vectors from both subspaces, as derived from Eq. (20):

To accomplish the transfer \(\vert {\psi _1} \rangle \rightarrow \vert {\psi _3} \rangle\), a five-step pulse-sequence of the form Bang-Off-Bang-Off-Bang is used in Ref.75. The corresponding path traveled can be expressed as \(\vert {\psi _1} \rangle\) \(\xrightarrow {\text {bang}}\) \(\vert {A} \rangle\) \(\xrightarrow {\text {off}} \vert {B} \rangle\) \(\xrightarrow {\text {bang}} \vert {C} \rangle \xrightarrow {\text {off}} \vert {D} \rangle \xrightarrow {\text {bang}} \vert {\psi _3} \rangle\) , where states \(\vert {A} \rangle , \vert {B} \rangle , \vert {C} \rangle , \vert {D} \rangle\) belong to one of the parity subspaces.

The first Bang rotates the initial state \(\vert {\psi _1} \rangle\) so that it lies entirely within one of the invariant subspaces; here we choose the \((-1)\) subspace. If \(\theta _1, \phi _1\) denote the rotation angle and phase of the Bang, respectively, the requirement that the rotated state \(\hat{U}_{\text {bang}}\vert {\psi _1} \rangle\) has zero projection in the \((+1)\) subspace gives the conditions

By processing the real and imaginary parts of the above relations it is not hard to end up with the solution \(\theta _1=3\pi /4\) and \(\phi _1=\pi /2\). The resulting state expressed in the parity basis is

In analogy with the first Bang, the last Bang rotates the ultimate state within the \((-1)\) subspace to the final target state \(\vert {\psi _3} \rangle\). We derive the corresponding conditions by taking the inverse rotation from the target state back to the \((-1)\) subspace. Similarly to the previous case we get

The corresponding solution is \(\theta _3=\pi /4\) and \(\phi _3=\pi /2\), while the state just before the Bang is

During the intermediate evolution from state \(\vert {A} \rangle\) after the first Bang to state \(\vert {D} \rangle\) before the last Bang the system remains within the \((-1)\) subspace. In this two-dimensional subspace the above states can be expressed as

while matrices (22) and (24) as

where

and the ± sign corresponds to the field phase \(\phi =0\) or \(\pi\). State \(\vert {A_s} \rangle\) is transferred to state \(\vert {D_s} \rangle\) by the intermediate part Off-Bang-Off of the pulse-sequence, thus

Let \(\xi _{1, 2} = Jt_{1,2}\) denote the rotation angles corresponding to the first and second Off pulses with duration \(t_{1,2}\), respectively, and \(\theta _2 = \lim _{\tau \rightarrow 0}(\Omega _0\tau )\) the rotation angle corresponding to the middle Bang pulse. For the phase of the Bang pulse, among the possible choices \(0, \pi\) which ensure that the state remains within the subspace we select \(\phi _2=\pi\) so the matrix \(\hat{H}_{-1x}^{(s)}\) is applied and as we will see leads to a positive angle \(\theta _2\). Parameters \(\xi _{1, 2}, \theta _2\) can be found by using Eq. (35). To simplify the calculations we exploit the observation that states \(\vert {A_s} \rangle , \vert {D_s} \rangle\) correspond to antipodal points on the Bloch sphere, see Fig. 6. We can use the diameter connecting these points as the new \(z'\) axis of the rotated coordinate system displayed in Fig. 6. In this new frame, the rotation axes corresponding to matrices \(\hat{H}_0^{(s)}\) and \(\hat{H}_{\pm 1x}^{(s)}\) become

while the initial and final states within the subspace

with \(\gamma\) being an overall phase accounting for the effect of identity matrices in Eq. (33). Condition (35) can be expressed as

where note that the effect of the second Off pulse is applied to state \(\vert {D_s} \rangle\) to get a simpler relation. From Eq. (38) we obtain

By taking the absolute square of both sides of any of the above equations we get

The total duration of the pulse sequence is determined by the durations of the Off pulses, since the Bang pulses are instantaneous, thus \(T=t_1+t_2= (\xi _1+\xi _2)/J\). To minimize T we take the derivative with respect to \(\xi _1\) and find the condition

By taking the derivative of Eq. (40) with respect to \(\xi _1\) we easily find

and if we plug it in Eq. (41) we get the condition

The acceptable solution of Eq. (43) is \(\xi _2=\xi _1\), since the other solution \(\xi _2 = \pi /4 - \xi _1\) leads to a false equality when plugged in Eq. (40). Using the equality of \(\xi _i\) in Eq. (40) we find

thus

To find angle \(\theta _2\), we multiply Eq. (39a) with the complex conjugate of Eq. (39b) to get

which gives

We have calculated analytically the optimal pulse sequence which was derived numerically in Ref.75, where note that \(\theta _2\) is the rotation angle around the \(-z'\) axis. Within the reduced subspace we found the minimum time trajectory displayed in Fig. 6, while the initial and final Bang pulses serve to instantaneously enter and exit this subspace. The corresponding total duration is

Note that this time limit has been derived using delta Bang pulses.

Charging via resonant excitation

To implement more efficiently the transfer \(\vert {\psi _1} \rangle \rightarrow \vert {\psi _3} \rangle\), we choose in Eq. (8) the carrier frequency as \(\omega _c = 2 (J +\Omega _z)\), which brings the initial and target states on resonance, ending up with the equation

We first show that, contrary to the case studied in “Case \(J<\Omega _z/2\)” section, a single delta Bang pulse cannot achieve the desired transfer instantaneously. We consider such a pulse with amplitude \(\Omega _0\rightarrow \infty\) and duration \(T\rightarrow 0\) so the rotation angle \(\theta = \Omega _0 T\) is finite, and constant phase \(\phi\). Then, the J-term in Eq. (49) can be neglected and we get the solution

From these expressions it is clear that whenever \(c_0(T) = 0\), we necessarily also have \(c_3(T) = 0\), thus a complete population transfer to state \(\vert {\psi _3} \rangle\) cannot be achieved with this method.

The next thought is to consider a Bang-Off-Bang sequence with delta Bangs; we show that this approach does not work either. Propagating the initial state forward by Bang-Off and the final state backward by the terminal Bang and demanding the equality of the resultant states,

we get the system of equations

where \(\theta _1, \theta _2\) and \(\phi _1, \phi _2\) are the rotation angles and phases of the two Bangs and \(\xi =JT\) is the normalized duration of the Off pulse. If we multiply Eqs. (52a) and (52d) and divide the result with the product of Eqs. (52b) and (52c) then we obtain, after some simplifications, the following equation

Now observe that, since one side of Eq. (52b) is real, it is necessarily \(e^{2 i \phi _2} = \pm 1\) and similarly \(e^{2 i \phi _1} = \pm 1\) from Eq. (52d) and \(e^{i (2\xi -\phi _1-\phi _2)} = \pm 1\) from Eq. (52c). From the first two relations we get \(e^{4 i \phi _1} = e^{4 i \phi _2} = 1\) and from the last \(e^{i (8\xi -4\phi _1-4\phi _2)} = 1\), which give \(e^{i8\xi }=1\) when combined. As is evident from Eq. (53), this would require the fractional term to be zero. Since the numerator is a non-zero constant, this yields a mathematical impossibility. Therefore, the Bang-Off-Bang sequence cannot accomplish the desired transfer.

Inspired by the previous work75, we try next a Bang-Off-Bang-Off-Bang sequence. Since Eq. (49) does not possess the symmetry of Eq. (17), here we cannot apply the procedure of “Fast charging via subspace decomposition” section to derive the pulse parameters analytically. We thus calculate them using numerical optimization. Let \(\theta _i\) and \(\phi _i\), \(i = 1, 2, 3\), denote the rotation angles and phases of the three delta Bang pulses and \(\xi _{1, 2}\) the normalized durations of the Off pulses. We propagate the initial state using this sequence and ask to find the pulse parameters which minimize the total duration \(T=(\xi _1+\xi _2)/J\) while achieving full charging of the quantum battery, \(|c_3(T)|=1\). The corresponding optimal parameters obtained from the numerical solution are presented in Table 1.

The corresponding total duration is

Note that this duration, obtained with resonant excitation between the initial and target states, is shorter than the one previously found in Eq. (48), as anticipated. The duration for full charging given in Eq. (54) is obtained using delta Bang pulses, thus imposes a lower limit on the necessary time when using the same sequence but with Bang pulses of finite amplitude.

We next use numerical optimal control to solve the problem of full charging a quantum battery with ratio \(\chi =J/\Omega _z=1\), but for finite maximum control amplitude, using the same upper bound values as in the case \(J < \Omega _z/2\), i.e. \(\Omega _0/\Omega _z = 1, 1.5, 5\). The results are presented in Figs. 7, 8 and 9, respectively. Observe that for small maximum control amplitude, \(\Omega _0=\Omega _z\), the optimal \(\Omega (t)\) is constant and equal to the maximum value, see Fig. 7a, as in the case \(J < \Omega _z/2\). But for larger \(\Omega _0 = 1.5\Omega _z\), the optimal \(\Omega (t)\) develops the structure Bang-Off-Bang, see Fig. 8a, while for even larger \(\Omega _0 = 5\Omega _z\) the sequence Bang-Off-Bang-Off-Bang arises, as shown in Fig. 9a. In Fig. 10 we plot the normalized maximum achievable stored energy \(\Delta E(T)/\Delta E_{max}\) obtained with numerical optimization, where \(\Delta E_{max}=4(1+\chi ) \Omega _z = 8\Omega _z\) for \(\chi = 1\), versus the available charging time T, for the same three values of the maximum control amplitude: \(\Omega _0/\Omega _z=1\) (black line), \(\Omega _0/\Omega _z=1.5\) (red line), and \(\Omega _0/\Omega _z=5\) (green line). The vertical line indicates the time limit given in Eq. (54), obtained with the Bang-Off-Bang-Off-Bang sequence with delta Bang pulses. Since for the finite value \(\Omega _0/\Omega _z=5\) the optimal pulse sequence has the Bang-Off-Bang-Off-Bang form displayed in Fig. 9a, the corresponding green curve intersects the full charging horizontal axis \(\Delta E(T)/\Delta E_{max} = 1\) at a duration longer than this limit. In Fig. 5a we plot the minimum time for full charging versus the maximum control amplitude (red curve), up to the value \(\Omega _0/\Omega _z = 10\). Note that it approaches the horizontal line corresponding to the limit (54), indicating that the optimal control maintains the Bang-Off-Bang-Off-Bang shape up to this value. We point out that for larger values of the maximum control amplitude \(\Omega _0\) more complicated optimal sequences may arise, with shorter charging times than the limit (54) obtained for this particular form. Finally, in Fig. 5b we display the corresponding average charging power as a function of \(\Omega _0\) (red curve).

Optimal control amplitude (a) and phase (b), along with the corresponding time evolution of stored energy (c) and populations (\(|c_0|^2\) black, \(|c_1|^2\) red, \(|c_2|^2\) green, \(|c_3|^2\) blue) (d) for full charging in minimum time, when \(\Omega _0/\Omega _z=1.5\) and \(\chi =J/\Omega _z=1.\).

Discussion

We begin the discussion by elucidating the relation between the charging protocols obtained in this work and the conventional coherent driving \(\Omega _0 \cos (\omega _c t)(\sigma _++\sigma _-)\) with constant amplitude applied on resonance. This conventional protocol is actually optimal in the case of a QB composed of non-interacting spins. The protocols derived here are essentially generalizations of this protocol for QBs with interacting spins. This is obvious in the weak coupling case, where the constant control amplitude is reinforced with a time-dependent phase (a chirp), which is capable to drive all the spins simultaneously to the spin-up target state, despite their different frequencies due to the interactions. A constant amplitude protocol without the proper phase modulation would fail to handle these interactions. For the strong coupling case where the starting state is not the conventional spin-down state but an entangled state, the additional feature of Off intervals appears in the optimal amplitude.

Next, it is instructive to explain how the obtained results are reconciled with the quantum speed limit. To demonstrate the argument is more convenient to work with the quantum speed limit for large control bound \(\Omega _0\). For a constant control with amplitude \(\Omega (t)=\Omega _0\) and phase \(\phi\), in the limit \(\Omega _0\gg J\), the Hamiltonian matrices for both the weak and strong coupling cases, Eqs. (17) and (49), are essentially proportional to \(\Omega _0\) and the same is true for the eigenenergies. Consequently, the quantum speed limit is proportional to \(1/\Omega _0\), which tends to zero for \(\Omega _0\rightarrow \infty\), This is consistent with our finding regarding the full charging time for weak coupling, but for strong coupling our analysis suggests a finite charging time even for very large \(\Omega _0\). The resolution comes when we realize that the quantum speed limit provides the minimum time for a quantum system to evolve from some initial state to an orthogonal state. For weak coupling the orthogonal state is indeed the target spin-up state, as discussed below Eqs. (18). But for strong coupling where the system starts from the entangled state, the orthogonal state where it evolves within the vanishingly small quantum speed limit is not the target spin-up state but a superposition state. This can be seen from Eqs. (50), where the choice \(\theta =\arccos (\sqrt{2/3})\) that nullifies the probability amplitude of the starting state, \(c_1(T) = 0\), does not lead to \(|c_3(T)| = 1\) but to a state with nonzero \(c_0(T), c_2(T) \ne 0\) also. The target spin-up state can be reached by exploiting the coupling, and this leads to a nonzero lower bound on the minimum-time, no matter how large is \(\Omega _0\). We close the discussion about speed limits observing that for the weak coupling case, where the system starts from the spin-down state, we expect an increase in the charging time with the number of spins. For the strong coupling case the situation is more complicated because the lowest energy starting state depends on the coupling and the charging time depends from where the system sets off.

Another interesting observation is regarding the symmetry of obtained protocols. For the case of weak coupling, the symmetry of the optimal amplitude and phase may be attributed to the symmetry of the Hamiltonian matrix in the corresponding Eq. (17) and the symmetry between the initial and target states. Even for the case with strong coupling, where the initial and target states are not symmetric, the symmetry of system (17) leads to equal durations of the Off pulses in the subspace decomposition method, which uses that system. On the other hand, when Eq. (49) is used for strong coupling in the resonant method, the symmetry is broken and this is reflected on the solutions obtained with either finite or delta bang pulses.

We also discuss the possible effect of dissipation on the optimal charging protocols. Dissipation processes limit the charging time window. If the minimum time for full charging is shorter than this window then the protocols will not be affected; otherwise, full charging is unattainable and an efficient protocol should do the best possible within the available time frame determined by dissipation. In the light of this observation, the Off intervals in the charging protocol for the strong coupling case may be reduced or even eliminated. The unavoidable presence of dissipation provides a serious motivation for deriving fast and efficient charging protocols.

Regarding the experimental implementation of the proposed protocols, note that from the amplitude \(\Omega (t)\) and phase \(\phi (t)\) the transverse component \(\Omega _x(t), \Omega _y(t)\) of the applied field can be obtained using Eq. (4). The implementation of such control fields in the NMR framework considered here is a routine procedure, see for example Ref.79.

Finally, note that although here we concentrate on the stored energy, a similar procedure can be followed for maximizing ergotropy, the maximum amount of work that can be extracted from the battery via a unitary process1. Specifically, after having charged the battery with the highest stored energy, the lowest energy eigenstate should be set as the target state in the optimal control problem, to extract the maximum possible work.

Conclusions

In this work, we obtained some fast protocols for charging a three-qubit Ising spin-chain quantum battery, using amplitude and phase control of the global transverse field. Two distinct cases were identified. For weak coupling between the qubits in the chain, where the initial ground state of the system is the spin-down state, we found that the optimal strategy is to keep the control amplitude fixed at its maximum value while properly modulate the phase with time. For the strong coupling case, where the initial ground state is the one-excitation Dicke state \(\vert {W} \rangle\), we employed two related charging protocols. In the first approach we used a pulse-sequence derived numerically in the recent work75, consisting of delta Bang pulses and intervals where the control is switched off. We named this method fast charging via subspace decomposition, because it involves identifying and manipulating effective two-level subsystems. In this article we derived analytically the characteristics of the pulses composing the sequence, which were calculated numerically in Ref.75. In the second approach, we used a similar pulse-sequence with delta Bang pulses and Off intervals, but with a carrier frequency which brings on resonance the initial \(\vert {W} \rangle\) state and the target spin-up state having maximum energy; we named this method charging via resonant excitation. We calculated numerically the characteristics of the pulses in the sequence and found a shorter charging time compared to the non-resonant method motivated by Ref.75. We also used numerical optimal control to solve the problem of full charging the quantum battery but with finite values of the control amplitude and found that, for some relatively large values of this bound, the optimal solution has similar structure with the sequence using delta Bang pulses but longer duration, as expected. The present work concentrates on a three-spin chain but the suggested approach can be also extended to larger systems. The lowest and highest energy eigenstates must be identified first, serving as the initial and target states. Then, optimal control can be used to calculate the amplitude and phase modulation of a control field resonant to this transition, to maximize the stored energy in the battery for a given duration.

Data availability

Data sets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Alicki, R. & Fannes, M. Entanglement boost for extractable work from ensembles of quantum batteries. Phys. Rev. E 87, 042123. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.87.042123 (2013).

Campaioli, F., Gherardini, S., Quach, J. Q., Polini, M. & Andolina, G. M. Colloquium: Quantum batteries. Rev. Mod. Phys. 96, 031001. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.96.031001 (2024).

Binder, F. C., Vinjanampathy, S., Modi, K. & Goold, J. Quantacell: Powerful charging of quantum batteries. New J. Phys. 17(7), 075015. https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/17/7/075015 (2015).

Rossini, D., Andolina, G. M., Rosa, D., Carrega, M. & Polini, M. Quantum advantage in the charging process of Sachdev–Ye–Kitaev batteries. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 236402. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.125.236402 (2020).

Gyhm, J.-Y., Šafránek, D. & Rosa, D. Quantum charging advantage cannot be extensive without global operations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 140501. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.128.140501 (2022).

Campaioli, F. et al. Enhancing the charging power of quantum batteries. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 150601. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.118.150601 (2017).

Gyhm, J.-Y. & Fischer, U. R. Beneficial and detrimental entanglement for quantum battery charging. AVS Quantum Sci. 6(1), 012001. https://doi.org/10.1116/5.0184903 (2024).

Andolina, G. M. et al. Charger-mediated energy transfer in exactly solvable models for quantum batteries. Phys. Rev. B 98, 205423. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.98.205423 (2018).

Le, T. P., Levinsen, J., Modi, K., Parish, M. M. & Pollock, F. A. Spin-chain model of a many-body quantum battery. Phys. Rev. A 97, 022106. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.97.022106 (2018).

Zhang, Y.-Y., Yang, T.-R., Fu, L. & Wang, X. Powerful harmonic charging in a quantum battery. Phys. Rev. E 99, 052106. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.99.052106 (2019).

Barra, F. Dissipative charging of a quantum battery. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 210601. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.122.210601 (2019).

Santos, A. C., Çakmak, B., Campbell, S. & Zinner, N. T. Stable adiabatic quantum batteries. Phys. Rev. E 100, 032107. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.100.032107 (2019).

Andolina, G. M. et al. Extractable work, the role of correlations, and asymptotic freedom in quantum batteries. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 047702. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.122.047702 (2019).

Crescente, A., Carrega, M., Sassetti, M. & Ferraro, D. Ultrafast charging in a two-photon Dicke quantum battery. Phys. Rev. B 102, 245407. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.102.245407 (2020).

Santos, A. C., Saguia, A. & Sarandy, M. S. Stable and charge-switchable quantum batteries. Phys. Rev. E 101, 062114. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.101.062114 (2020).

Santos, A. C. Quantum advantage of two-level batteries in the self-discharging process. Phys. Rev. E 103, 042118. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.103.042118 (2021).

Carrasco, J., Maze, J. R., Hermann-Avigliano, C. & Barra, F. Collective enhancement in dissipative quantum batteries. Phys. Rev. E 105, 064119. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.105.064119 (2022).

Dou, F.-Q., Lu, Y.-Q., Wang, Y.-J. & Sun, J.-A. Extended Dicke quantum battery with interatomic interactions and driving field. Phys. Rev. B 105, 115405. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.105.115405 (2022).

Barra, F., Hovhannisyan, K. V. & Imparato, A. Quantum batteries at the verge of a phase transition. New J. Phys. 24(1), 015003. https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/ac43ed (2022).

Gemme, G., Grossi, M., Ferraro, D., Vallecorsa, S. & Sassetti, M. IBM quantum platforms: A quantum battery perspective. Batteries 8(5), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries8050043 (2022).

Shaghaghi, V., Singh, V., Benenti, G. & Rosa, D. Micromasers as quantum batteries. Quantum Sci. Technol. 7(4), 04LT01. https://doi.org/10.1088/2058-9565/ac8829 (2022).

Rodríguez, C., Rosa, D. & Olle, J. Artificial intelligence discovery of a charging protocol in a micromaser quantum battery. Phys. Rev. A 108, 042618. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.108.042618 (2023).

Kamin, F., Abuali, Z., Ness, H. & Salimi, S. Quantum battery charging by non-equilibrium steady-state currents. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 56(27), 275302. https://doi.org/10.1088/1751-8121/acdb11 (2023).

Downing, C. A. & Ukhtary, M. S. A quantum battery with quadratic driving. Commun. Phys. 6(1), 322. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-023-01439-y (2023).

Downing, C. A. & Ukhtary, M. S. Energetics of a pulsed quantum battery. Europhys. Lett. 146(1), 10001. https://doi.org/10.1209/0295-5075/ad2e79 (2024).

Hadipour, M., Haseli, S., Wang, D. & Haddadi, S. Practical Scheme for Realization of a Quantum Battery (2023).

Kamin, F. H., Tabesh, F. T., Salimi, S. & Santos, A. C. Entanglement, coherence, and charging process of quantum batteries. Phys. Rev. E 102, 052109. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.102.052109 (2020).

Pirmoradian, F. & Mølmer, K. Aging of a quantum battery. Phys. Rev. A 100, 043833. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.100.043833 (2019).

Zhang, X. & Blaauboer, M. Enhanced energy transfer in a Dicke quantum battery. Front. Phys. 10, 1097564. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2022.1097564 (2023).

Crescente, A., Carrega, M., Sassetti, M. & Ferraro, D. Charging and energy fluctuations of a driven quantum battery. New J. Phys. 22(2020), 063057. https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/ab91fc (2020).

Joshi, J. & Mahesh, T. S. Experimental investigation of a quantum battery using star-topology NMR spin systems. Phys. Rev. A 106, 042601. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.106.042601 (2022).

Mohan, B. & Pati, A. K. Reverse quantum speed limit: how slowly a quantum battery can discharge. Phys. Rev. A 104, 042209. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.104.042209 (2021).

Niedenzu, W., Mukherjee, V., Ghosh, A., Kofman, A. G. & Kurizki, G. Quantum engine efficiency bound beyond the second law of thermodynamics. Nat. Commun. 9(1), 165. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01991-6 (2018).

Ferraro, D., Campisi, M., Andolina, G. M., Pellegrini, V. & Polini, M. High-power collective charging of a solid-state quantum battery. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 117702. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.120.117702 (2018).

Zhao, F., Dou, F.-Q. & Zhao, Q. Quantum battery of interacting spins with environmental noise. Phys. Rev. A 103, 033715. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.103.033715 (2021).

Rossini, D., Andolina, G. M. & Polini, M. Many-body localized quantum batteries. Phys. Rev. B 100, 115142. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.100.115142 (2019).

Zakavati, S., Tabesh, F. T. & Salimi, S. Bounds on charging power of open quantum batteries. Phys. Rev. E 104, 054117. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.104.054117 (2021).

Zhao, F., Dou, F.-Q. & Zhao, Q. Charging performance of the Su–Schrieffer–Heeger quantum battery. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, 013172. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevResearch.4.013172 (2022).

Hu, C.-K. et al. Optimal charging of a superconducting quantum battery. Quantum Sci. Technol. 7(4), 045018. https://doi.org/10.1088/2058-9565/ac8444 (2022).

Buy Wenniger, I. et al. Experimental analysis of energy transfers between a quantum emitter and light fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 260401. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.131.260401 (2023).

Quach, J. Q. et al. Superabsorption in an organic microcavity: Toward a quantum battery. Sci. Adv. 8(2), 3160. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abk3160 (2022).

Dou, F.-Q., Wang, Y.-J. & Sun, J.-A. Closed-loop three-level charged quantum battery. Europhys. Lett. 131(4), 43001. https://doi.org/10.1209/0295-5075/131/43001 (2020).

Moraes, L. F. C., Saguia, A., Santos, A. C. & Sarandy, M. S. Charging power and stability of always-on transitionless driven quantum batteries. Europhys. Lett. 136(2), 23001. https://doi.org/10.1209/0295-5075/ac1363 (2022).

Dou, F.-Q., Wang, Y.-J. & Sun, J.-A. Highly efficient charging and discharging of three-level quantum batteries through shortcuts to adiabaticity. Front. Phys. 17(3), 31503. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11467-021-1130-5 (2021).

Moraes, L. F. C., Duriez, A. C., Saguia, A., Santos, A. C. & Sarandy, M. S. Quantum battery supercharging via counter-diabatic dynamics. Quantum Sci. Technol. 9(4), 045033. https://doi.org/10.1088/2058-9565/ad71ed (2024).

Dou, F.-Q., Wang, Y.-J. & Sun, J.-A. Charging Advantages of Lipkin–Meshkov–Glick Quantum Battery (2022).

Guo, W.-X., Yang, F.-M. & Dou, F.-Q. Analytically solvable many-body Rosen–Zener quantum battery. Phys. Rev. A 109, 032201. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.109.032201 (2024).

Yang, F.-M. & Dou, F.-Q. Resonator-qutrit quantum battery. Phys. Rev. A 109, 062432. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.109.062432 (2024).

Mazzoncini, F., Cavina, V., Andolina, G. M., Erdman, P. A. & Giovannetti, V. Optimal control methods for quantum batteries. Phys. Rev. A 107, 032218. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.107.032218 (2023).

Evangelakos, V., Paspalakis, E. & Stefanatos, D. Fast charging of an Ising-spin-pair quantum battery using optimal control. Phys. Rev. A 110, 052601. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.110.052601 (2024).

Rodríguez, R. R. et al. Optimal quantum control of charging quantum batteries. New J. Phys. 26(4), 043004. https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/ad3843 (2024).

Erdman, P. A., Andolina, G. M., Giovannetti, V. & Noé, F. Reinforcement learning optimization of the charging of a Dicke quantum battery. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 243602. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.133.243602 (2024).

Sun, P.-Y., Zhou, H. & Dou, F.-Q. Cavity-Heisenberg spin-j chain quantum battery and reinforcement learning optimization (2024). arxiv:2412.01442

Gemme, G., Grossi, M., Vallecorsa, S., Sassetti, M. & Ferraro, D. Qutrit quantum battery: Comparing different charging protocols. Phys. Rev. Res. 6, 023091. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevResearch.6.023091 (2024).

Catalano, A. G., Giampaolo, S. M., Morsch, O., Giovannetti, V. & Franchini, F. Frustrating quantum batteries. PRX Quantum 5, 030319. https://doi.org/10.1103/PRXQuantum.5.030319 (2024).

Grazi, R., Sacco Shaikh, D., Sassetti, M., Traverso Ziani, N. & Ferraro, D. Controlling energy storage crossing quantum phase transitions in an integrable spin quantum battery. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 197001. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.133.197001 (2024).

Ali, A. et al. Ergotropy and capacity optimization in Heisenberg spin-chain quantum batteries. Phys. Rev. A 110, 052404. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.110.052404 (2024).

Yang, H.-Y. et al. Optimal energy storage in the Tavis–Cummings quantum battery. Phys. Rev. A 109, 012204. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.109.012204 (2024).

Downing, C. A. & Ukhtary, M. S. Hyperbolic enhancement of a quantum battery. Phys. Rev. A 109, 052206. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.109.052206 (2024).

Mitra, A. & Srivastava, S. C. L. Sunburst quantum Ising battery. Phys. Rev. A 110, 012227. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.110.012227 (2024).

Stefanatos, D. & Paspalakis, E. A shortcut tour of quantum control methods for modern quantum technologies. Europhys. Lett. 132(6), 60001. https://doi.org/10.1209/0295-5075/132/60001 (2021).

Král, P., Thanopulos, I. & Shapiro, M. Colloquium: Coherently controlled adiabatic passage. Rev. Mod. Phys. 79, 53–77. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.79.53 (2007).

Vitanov, N. V., Rangelov, A. A., Shore, B. W. & Bergmann, K. Stimulated Raman adiabatic passage in physics, chemistry, and beyond. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 015006. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.89.015006 (2017).

Guéry-Odelin, D. et al. Shortcuts to adiabaticity: Concepts, methods, and applications. Rev. Mod. Phys. 91, 045001. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.91.045001 (2019).

Deffner, S. & Campbell, S. Quantum speed limits: From Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle to optimal quantum control. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 50(45), 453001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1751-8121/aa86c6 (2017).

Shrimali, D., Panda, B. & Pati, A. K. Stronger speed limit for observables: Tighter bound for the capacity of entanglement, the modular Hamiltonian, and the charging of a quantum battery. Phys. Rev. A 110, 022425. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.110.022425 (2024).

Pontryagin, L. S., Boltyanskii, V. G., Gamkrelidze, R. V. & Mishchenko, E. F. The Mathematical Theory of Optimal Processes (Interscience Publishers, 1962).

Schättler, H. & Ledzewicz, U. Geometric Optimal Control: Theory, Methods and Examples (Springer, 2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3834-2.

Stefanatos, D. Optimal design of minimum-energy pulses for Bloch equations in the case of dominant transverse relaxation. Phys. Rev. A 80, 045401. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.80.045401 (2009).

Boscain, U., Sigalotti, M. & Sugny, D. Introduction to the Pontryagin maximum principle for quantum optimal control. PRX Quantum 2, 030203. https://doi.org/10.1103/PRXQuantum.2.030203 (2021).

Lokutsievskiy, L. V., Pechen, A. N. & Zelikin, M. I. Time-optimal state transfer for an open qubit. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 57(27), 275302. https://doi.org/10.1088/1751-8121/ad5396 (2024).

Koch, C. P. et al. Quantum optimal control in quantum technologies. Strategic report on current status, visions and goals for research in Europe. EPJ Quantum Technol. 9, 19. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjqt/s40507-022-00138-x (2022).

Duncan, C. W., Poggi, P. M., Bukov, M., Zinner, N. T. & Campbell, S. Taming quantum systems: A tutorial for using shortcuts-to-adiabaticity, quantum optimal control, and reinforcement learning (2025). arxiv:2501.16436

Evangelakos, V., Paspalakis, E. & Stefanatos, D. Rapid charging of a two-qubit quantum battery by transverse field amplitude and phase control. Quantum Sci. Technol. 10(3), 035024. https://doi.org/10.1088/2058-9565/add207 (2025).

Stojanović, V. M. & Nauth, J. K. Dicke-state preparation through global transverse control of Ising-coupled qubits. Phys. Rev. A 108, 012608. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.108.012608 (2023).

Ansel, Q. et al. Introduction to theoretical and experimental aspects of quantum optimal control. J. Phys. B At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 57(13), 133001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6455/ad46a5 (2024).

Caillau, J.-B., Cots, O., Gergaud, J., Martinon, P. & Sed, S. OptimalControl.jl: A Julia Package to Model and Solve Optimal Control Problems with ODE’s. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13336563 . https://control-toolbox.org/OptimalControl.jl

Jandura, S. & Pupillo, G. Time-optimal two- and three-qubit gates for Rydberg atoms. Quantum 6, 712. https://doi.org/10.22331/q-2022-05-13-712 (2022).

Lapert, M., Zhang, Y., Janich, M. A., Glaser, S. J. & Sugny, D. Exploring the physical limits of saturation contrast in magnetic resonance imaging. Sci. Rep. 2(1), 589. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00589 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The publication fees of this manuscript have been financed by the Research Council of the University of Patras.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Already incorporated in the text

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Evangelakos, V., Paspalakis, E. & Stefanatos, D. Fast protocols for charging a three-spin-chain quantum battery. Sci Rep 15, 45626 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30354-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30354-1