Abstract

The popularity of Electric Vehicles (EVs) poses particular challenges for demand-side energy management, especially in low-computation scenarios. This research builds a lightweight machine learning (ML) model to forecast EV consumption load and to maximise Demand Response (DR) strategies using real-world data. The Kaggle dataset used in this research consists of time-series EV charging data, which is preprocessed, down sampled, and augmented with time-based features, including hour, weekday, and month. Seven DR strategies, which are Peak Clipping, Valley Filling, Load Shifting, Load Levelling, Strategic Load Growth, Strategic Conservation, and Flexible Load Shape, are implemented on estimated load profiles. The model experiments consist of five ML models: Linear Regression (LR), Support Vector Regression (SVR), k-Nearest Neighbours (kNN), Random Forest (RF), and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), and their results for both prediction and computation. Such models are selected since they are suitable for systems that lack resources. To serve all DR cases, the measurement metrics used are MAE, RMSE, and R2. Findings suggest that XGBoost is the most error-free technique across most DR approaches, achieving an R2 score of 0.975 in Strategic Conservation and 0.943 in Valley Filling, with the highest efficiency, seconded by Random Forest with an R2 score of 0.91. The results of linear regression and kNN were worse, with R² values never exceeding 0.50 across most DR strategies. The work demonstrates the capacity to deliver successful performance from lightweight ML models for EV load prediction and DR modelling, and that such models can provide scalable information to grid operators and policymakers operating within constrained computational environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The world is moving rapidly toward electric mobility, making electric vehicles (EVs) a key solution to reducing carbon emissions and increasing long-term energy security. This change has been further spurred by national programs such as the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fast Charging Pilot Program, which has increased the number of charging stations and encouraged sustainable transport. Nonetheless, the rapid and widespread adoption of EVs has significant operational costs. Peak overcharging may disrupt local grids, exacerbate load imbalances, and overload distribution resources, particularly during seasonal variations1,2.

DR programs have become a critical process to alleviate these stresses. Peak Clipping, Energy Cost, Valley Filling, and Load Shifting3,4 are a few strategies that can be used to redistribute charging demand, reduce load congestion, and lower consumer energy costs. Recent studies show that smart EV charging enabled by DR can make the grid much more reliable. The hybrid ensemble based on Bi-LSTM is incredibly accurate in forecasting and significantly lower costs, and other models (Random Forest and SVR) have been demonstrated to be useful for supporting DR-driven EV dispatching in distributed energy systems5. Although such advances have been made, several high-performing models remain computationally costly and unadaptable to real-world use on embedded controllers, edge devices, or low-power charging infrastructure. This is where the gap arises: seeking ML methods that are both predictive and computationally efficient.

In a bid to overcome this challenge, the current study analyses a lightweight yet effective machine-learning pipeline for optimising DR-based EV charging. The data is strategically downsampled from a publicly available Kaggle EV Charging Dataset to simulate resource-constrained execution environments characteristic of embedded control systems. Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) and systematic temporal feature engineering are performed to represent the most important behavioural trends using simple predictors (hour, weekday, day, and month). Several regression models, including Linear Regression, Random Forest, Support Vector Regression (SVR), K-Nearest Neighbours (KNN), and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), are compared with each other and with seven different DR strategies.

The findings indicate that even with less data and limited computational resources, lightweight models can achieve competitive performance. It is worth noting that XGBoost achieved high predictive performance with low overhead, as evidenced by R2 values of 0.975 and 0.943 for Strategic Conservation and Valley Filling, respectively. These results support the idea that scalable, inexpensive ML solutions can assist in the practical coordination of EV charging without overwhelming sparse hardware. In general, the article helps address the research gap between high-level smart-charging simulations and practical applications by showing that demand-responsive EV charging in low-resource settings is feasible with precise, interpretable, and computationally efficient ML models.

Literature review

The rapid development of electric vehicles (EVs) has heightened the need for smart energy management, particularly in demand response (DR) programs to protect grid stability. The literature review of the general environment of electric mobility in smart grids also emphasises the challenges in infrastructure and operations posed by large-scale EV deployment, but fails to consider predictive DR-oriented modelling and lightweight deployments1. The analysis of EV charging behaviour based on actual charging-station data is valuable for forecasting, but there is no discussion of DR strategies or low-power deployment issues2. The excellent predictive capabilities of the developed load-forecasting models based on Bi-LSTM ensembles are accompanied by high computational costs, which cannot be afforded by embedded or real-time systems3. Likewise, renewable penetration and patterns of carbon intensity are found to be influential drivers of EV charging behaviour using XGBoost with SHAP interpretability, but model feasibility is not assessed on limited hardware platforms5.

Reinforcement-learning (RL) methods have also been explored for deployment-oriented smart EV charging, and these methods have been deployed on FPGA-based systems to enhance execution efficiency. Although these systems exhibit good control performance, they are limited by the computational complexity of RL, which restricts their practical application in low-power edge environments6. DR- and RL-based approaches for handling EV charging demand are also used to further improve grid responsiveness; however, their computational and memory requirements exceed the capabilities of embedded systems7. Coordinated deep RL systems have also been investigated for controlling V2G-based DR, but would entail extensive computation and storage, limiting their use to small systems4,8.

Combined modelling techniques based on XGBoost and cumulative prospect theory can improve charging-related decision analysis, but do not address runtime and memory efficiency, a key concern for interpretability9. Other studies that address the computational complexity of SHAP-based interpretability propose clustering-enhanced explanation methods that are less expensive to explain but have not been used in EV DR prediction challenges10,11. The other literature on grid peak-mitigation algorithms offers useful information on reducing charging-related load spikes but lacks incorporation of ML-based forecasting, not to mention lightweight deployment requirements12.

All these studies promote forecasting precision, interpretability and control of EV charging systems. Nevertheless, they mostly do not account for the need for lightweight, explainable, and compute-efficient ML models that can be deployed on embedded EV charger controllers and in low-resource settings. The current research closes this gap by comparing XGBoost and Random Forest regression models operating in down-sampled and low-power settings and shows that precise DR-based EV charging prediction can be achieved at low computational cost.

The most recent research on optimizing electric vehicle (EV) charging has shown that combining intelligent control and demand-side management (DSM) with machine learning (ML) can be critical to achieving grid efficiency, stability, and sustainability. ML-based energy forecasting of microgrids with distributed energy sources39, sustainable energy control in light EVs with hybrid storage systems40, and DSM models that utilize EV integration with sophisticated optimisation methods have been studied41. Solutions based on blockchain have been proposed to enhance interoperability and security in demand response (DR) coordination42. Hybrid policy models and AI-incorporated blockchain frameworks have addressed economic-emission trade-offs and real-time load balancing in EV networks43,44. Scheduling and infrastructure planning have been enhanced through optimisation techniques, including swarm intelligence45, stochastic modelling46, and coordinated fleet charging systems47, complemented by resilient charging-station design methodologies48,49. EV technology and grid integration reviews and forecasting methods have been found to point at the current progress as well as challenges50,51, whereas adaptive load shedding studies52, metaheuristic power flow algorithms53, and queuing-theoretical infrastructure models54 have been applied to dynamic operational uncertainties. The attempts to implement vehicle-to-grid technology in renewable microgrids55, to mitigate charging-station impacts through innovative control methods56, and to redefine the EV business environment57 have expanded the range of applications for smart charging solutions. In addition, research on fast-charging systems58, AI/ML-based cybersecurity for EVs59, and extensive surveys of DSM strategies and market structuring60,61,62 all point to the need for interpretable, computationally efficient, and scalable ML-based systems. The relevance of the lightweight, edge-compatible approach of this study to proper forecasting of EV demand under different DR strategies is supported by these developments63. Recent EV and energy-management literature highlights significant advancements across power-quality improvement, converter design, demand response (DR), forecasting, and intelligent control. For EV charging, an enhanced CPCV algorithm improves grid-side power quality during battery charging64, while high-efficiency multi-load and poly-input DC–DC converter topologies further strengthen EV power electronics65,66. In microgrid optimization, price-elastic DR combined with metaheuristics such as Greedy Rat Swarm Optimization67 and optimized rule-based AC/DC hybrid microgrid management68 enables both economic and operational gains. DR-centric charging strategies are further expanded through comparisons of unidirectional versus bidirectional (V2G) charging in solar-powered buildings, demonstrating improved PV utilization and reduced grid imports under bidirectional control69. Forecasting research contributes essential predictive intelligence to DR by improving short-term electricity forecasting using advanced ML architectures70, LSTM-based imbalance prediction in large power systems71, hybrid autoencoder–LSTM solar forecasting72, ANN-based industrial energy prediction73, and Bayesian-optimized hybrid deep learning for solar irradiance74. Beyond energy forecasting, intelligent control frameworks using reinforcement learning and edge computing improve task offloading and decision-making in Internet-of-Vehicles environments75. Complementing these, related EV-focused converter and charging system research provides additional hardware-level enhancements for efficient EV power management65,66. Collectively, these studies underscore the increasing integration of advanced forecasting, DR optimization, converter efficiency techniques, and intelligent EV charging control—reinforcing the need for lightweight, accurate, and deployable ML frameworks such as the one proposed in this work.

According to the literature reviewed, a continuum of methods for electric vehicle charging prediction and demand response regulation can be proposed, ranging from deep learning models, including BiLSTM and stacked LSTM, to ensemble algorithms, including XGBoost and LightGBM. In this study, Table 1 provides an overview of the significant contributions and research gaps in recent works. Although the literature on accuracy and interpretability is rich, there is an interesting gap regarding the computational cost of execution under edge- or resource-constrained conditions. The majority of deep learning and reinforcement learning algorithms are powerful, yet they also demand significant computational resources and train rapidly. Also, other critical factors, such as effective feature engineering and the ability to implement DR strategies, are often overlooked, which poses a challenge for their practical application. The current developments in edge machine learning have enabled small neural networks and compression techniques that can retain accuracy while simultaneously reducing inference latency and model size exponentially. Similarly, advancements in interpretability algorithms have enabled tree-based and ensemble models to be more transparent in real-time use. Despite these advancements, most existing frameworks have failed to achieve a balance between computational cost and predictability in dynamic, real-time EV charging environments. Federated learning and deep reinforcement algorithms have promise for decentralised charger coordination, but are not very efficient at scale and incur significant communication overheads, so some may not be encouraged to use such schemes in embedded systems or resource-limited infrastructures. Also, given the recent increase in comparative research on forecasting techniques, there is a high risk that the key to data dimensionality reduction or to maximising time in real-time scheduling in power systems may be neglected. An electric vehicle charging system would require appropriate load prediction and the capability to intelligently respond to demand signals without excessive grid loading. This needs to be supported by machine learning systems that are interpretable, lightweight (i.e., capable of operating in a limited hardware environment) and consistent across different DRs.

The proposed current research will address these barriers and offer a resource-sensitive, scalable machine learning pipeline tailored specifically to EV chargers’ demand response. The pipeline is an ensemble learning model trained on datasets sampled and engineered over time, optimised to be low-power-consuming and real-time prognosticators. The proposed study identifies the gap between theoretical advances in the development of intelligent charging algorithms and their practical application in grid-edge contexts, which can serve as a real-world solution for future smart EV charging infrastructure. The rest of the paper is organised as follows: section “Literature review” provides a comprehensive literature review of the latest trends in EV charging, demand response, and lightweight machine learning. The third part outlines the suggested approach, encompassing data preprocessing, feature engineering, and model building. In section “Results”, the experiment results and those of both models are discussed. Section “Model comparison and aggregate evaluation” is a comparative analysis and summary of all models on the demand response strategies. Section “Discussion” provides a conclusion of the work and outlines the key findings, and section “Conclusion” presents potential directions for further work, including more difficult deployment scenarios and programmable hardware-level optimizations.

Methodology

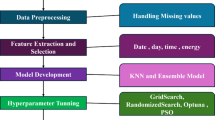

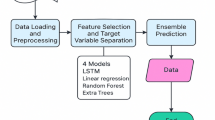

The methodology presented is described in a mind map. It is based on a closed-loop structure, as the approach was iterative and adaptive in finding the optimal solution for electric vehicle (EV) charging in conjunction with demand response (DR) strategies utilising machine learning (ML). Data minimization and sampling are the first steps, in which an EV charging dataset available publicly will be pared down to decrease computational requirements and make it compatible with low-power environments. Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) and feature engineering are then performed, with features extracted to provide information about time and context, including hour, day, month, and weekday, to improve model accuracy. Subsequently, the labelling of DR strategies will be achieved through the simulation of DR strategies using the named synthetic labels, which symbolize energy policies in the real world. A variety of lightweight machine learning (ML) models, including Linear Regression, Random Forest, SVR, KNN, and XGBoost, are trained and tested for each strategy.

As a further measure to improve the performance and consistency, hyperparameter optimization and R-squared scaling are included, which guarantee a reasonable comparison and maximization of prediction capability. The final one is this visualization of results and error analysis, which inputs into the data processing and analysis form. This recursive trend reinforces the fact that feedback-based development techniques are recursive in nature whereby in each iteration, the pipeline is refined resulting in a feasible, describe-able, and deployable solution to DR-based EV charging in resource-starved system implementations as illustrated in Fig. 1. The article is dedicated to the use of a systematic machine learning pipeline to forecast energy usage (kWh Delivered) that is required in charging electric vehicle (EV) charging sessions under different Demand Response (DR) plans. The general goal is to develop computationally feasible, understandable, and scalable logic and implement it in low-resource environments. The methodologies involved are data preparation, exploratory data analysis, synthetic feature engineering, DR simulation, model selection, hyperparameter tuning, evaluation, and visualisation. The Synthetic EV Charging Dataset is the data used in this research paper and is available on Kaggle, posted by Gholizadeh, Nastaran38. It is a model of the actual behavior of EV charging stations in California and has over 2.1 million rows of data that are separated into variables including session timestamps, the quantity of energy charged (kWh Delivered) and other session features. As the study deals with low-level computing power systems, a random sample of 50,000 records had to be chosen, to make the analysis simple, but maintain the representativeness. In all the modeling stages, this subset did not change.

To analyze the distribution of the features, detect the anomalies, and to interpret the relationships among the variables, the Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) was conducted. The target variable kWh Delivered was also proved to be right-skewed since the data set also reflects the essence nature of the variability of the session length and the nature of vehicles. Correlation matrices of input variables with the target showed weak non-trivial relationships, especially in time-based variables.

No extreme cases of missing data or aberrant formatting were found and, therefore, there was no clean modeling that required imputation. Other predictors were also generated to improve the feature richness and temporal resolution. These were hour and weekday, which did the modulo operation of connection Time decimal and utilized the day Indicator as the source of information. In order to estimate potential calendar effects, two synthetic variables were produced, one month and the other day randomly. These features may be used to model recurrent cases of behavior patterns in charging preferences without external APIs or libraries and hence the embedded system applications are simple. The data set was added with a new column, DR Strategy, which indicates the record as being in one of the seven possible strategies it had previously been known, including Peak Clipping, Valley Filling, Load Shifting, Strategic Conservation, Strategic Load Growth, Flexible Load Shape or a dummy category of None. These policy interventions are randomly assigned labels and thus the analysis can be subdivided into demand response (DR) contexts. The machine learning regressors that were tested included Linear Regression (LR), Support Vector Regression (SVR), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Random Forest (RF), and XGBoost. The reason why these models have been selected is because of the famous performance and complexity trade-offs. Each of the DR strategies would have been trained as a separate model with the features hour, day, month, and weekday and the target variable being the kWh Delivered. Standardization was done with the help of Standard Scaler to give stability to various models, which use numeric data. The random forest, XGBoost, and KNN models employed the use of Grid Search CV which was used to optimize hyperparameters. Parameters included in the grid search were the number of estimators, maximum depth, learning rate, and number of neighbors and 3-fold cross-validation was implemented to prevent overfitting. The best estimator of every grid search was chosen to be evaluated at the same time. The model measure of performance was conducted through three regression indicators of Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Mean Squared Error (MSE) and R-squared score Jackson and Clarke (2003) suggested that to give an interpretation of the groups of strategies, the R 2 values had to be normalized with Min-Max normalization scaling ranging between 0 and 1. This offered a better method of making a comparative analysis between various models and various strategies with varying data distributions. Visualization was a part of model interpretability. Plots of actual and predicted were developed against each of the DR strategies and models to determine the fit. MAE, MSE, and R2 bar plots provided by all strategies and models provided general information about the performance trends. We generated correlation heatmaps as well, which enabled the downstream feature selection checking and assistance.

Results

Data exploration insights

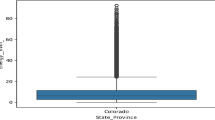

The data set that will be used in this study is a subset of 50,000 records of the larger Kaggle Synthetic EV Charging Dataset, the selection process being driven by the need to be statistically representative and the need to reduce the amount of computation involved. The Exploratory Data Analysis EDA was done to better understand the nature and behavior of the variables before the training of the models. The target variable, kWh Delivered, had a right-skewed distribution, most of the sessions used less than 10 kWh and the long tail was beyond 30 kWh (Fig. 2). This is in line with the charging behavior of EVs in the real world where majority of cars are not charged to full capacity but rather partially. Features that are related to time like hour and weekday showed a strong impact on charging patterns.

The peak in the delivery of energy was recorded during the business hours, particularly between 8 AM and 6 PM and weekdays reported a little higher charging activity as compared to the weekends. Correlation heatmaps showed that there were moderate correlations between time-based variables and the target variable. These results justified the incorporation of time in the development of the models.

Moreover, there were no any serious anomalies or missing values in the dataset, which provided the opportunity to proceed unproblematically to modeling in Fig. 2. The correlation heatmap shows 2-way relationship between the significant features of the EV charging dataset. Markedly, there is a positive relationship between kWh Delivered and charging Duration (r = 0.50), meaning that longer sessions would bring a larger amount of energy. Less significant positive relationships are found between kWh Delivered and connection time decimal (r = 0.29), indicating light trends in time. The day Indicator variable is almost entirely uncorrelated with other features, indicating that it does not do much to deliver direct energy and it might need transformation or some other context to be predictive. This observation informed the choice and design of more timely important features, Fig. 3 demonstrates the correlation heatmap.

Figure 4 gives Box Plots of Distribution of Connection Time, Charging Duration, And Energy Delivered during EV charging Sessions. The box plots are a brief graphical display of activities of user actions during the EV charging session. Connection mainly happens in the evening times as evidenced by distribution of connection sessions. The charging intervals are not very long, but there are outliers in more lengthy sessions which are not very many but exist mostly in the range of 1 to 4 h and some are 5 and more. Equally, the energy supplied is roughly 7 to 8 kWh and the fact that outliers are present indicates that there are sessions that have a significant amount of energy. Overall, such plots demonstrate the uncertainty and variability of the behavior of charging, which is useful in predicting demand and information on infrastructural planning. The dataset of EV charging that was studied demonstrates that there are major trends associated with the user activity and energy usage, and it can be assumed that in the future, its use and the trends observed can be reflected in predictive modeling. The distributions, correlation and visualizations e.g. right skewness in the delivered energy and there is a time-of-day effect that affects the level of activity in the session demonstrate that a time-dependent factor must be factored in the models to rely on in the forecasting. This is a solid ground as to the next step of the model development, as the selected features will be oriented toward the realities of the EV charging and contribute to the effective implementation of a demand response plan.

Model performance across DR strategies

The paper has investigated five machine learning regression models, which are Linear Regression (LR), Support Vector Regression (SVR), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Random Forest (RF) and XGBoost. The models were trained and tested on each of the seven simulated Demand Response (DR) strategies which were; Peak Clipping, Valley Filling, Load Shifting, Strategic Conservation, Strategic Load Growth, Flexible Load Shape, and None.

Linear regression

Linear Regression served as a performance baseline across all DR strategies76,77,78. The model did not manage to reflect the nonlinear patterns of EV charging data resulting in low and constant R2 scores. Despite its computational efficiency, its simplicity restricted its capability to generalize particularly in situations where there was high demand variability as is shown in Fig. 5.

Linear Regression cannot be compared with other models as its simple and interpretative model is always inferior. Its R 2 values are between approximately 0.06 and 0.11, which means that it has a low level of capturing the variability in the data. It would revert to the mean when its predictions are not useful in explaining high-variance sessions as we would find in actual vs. predicted plots. It does however, give a useful base as presented in Table 2.

Support vector regression

In most instances of regression of data, SVR was more accurate than linear regression. The model was found to provide better trend matching, especially, with the Valley Filling and Strategic Load Growth strategies. Nonetheless, it was still performing poorly on peak regions and had more computation-time than the simpler models. The findings are presented in Fig. 6.

Table 3 indicates that SVR also provides competitive results, with R 2 between 0.12 and 0.16, and R 2 scores over 0.6. The complexity of patterns is managed by its kernel-based approach, however, at the expense of a small increase in computation, as compared to Random Forest. Strategic Load Growth and Strategic Conservation Strategies are those, where SVR is particularly sufficient.

K-nearest neighbors

KNN model performed poorly based on the DR strategy. It was also highly susceptible to noises in strategies that have very differentiated consumption like Flexible Load Shape and None. The use of local patterns limited the generalizability of the model and thus the lowest R2 values of all the models as indicated in the graphs in Fig. 7.

Table 4 reveals that KNN does not work well compared to SVR and XGBoost, especially with high-variance situations. It has a range of R2 scores between 0.07 and 10 that shows a worse predictive fit. The flaws with this model include sensitivity to noise and time lack of contextualization. Although it is easy to apply, it does not suit unstable disaster recovery (DR) systems.

Random forest

Random Forest was a good performing strategy in all DR strategies. The feature interactions were well exploited and overfitting minimized by its ensemble approach. As indicated in Fig. 8, MAE and MSE scores were considerably lower than linear and distance-based models, and the R 2 of most of the strategies was above 0.7.

As Table 5 demonstrates, she proves to be better than Linear Regression in all DR strategies, with R2 scores as high as approximately 0.14 in some of the strategies and even greater R 2 scores (e.g., R 2 = 0.75 in Strategic Conservation). It is a more effective capture of non-linearity, and it is more complex and takes longer to invert than the linear models. It shows good tradeoffs between MAE and MSE so that it is possible to be used as a mid-level solution to resource-constrained systems.

Extreme gradient boost

In this study, XGBoost has been the highest-performing model. Its gradient boosting model enabled it to fit optimally on all DR strategies. Specifically, Strategic Load Growth had an optimal R 2 = 1.0. XGBoost also continued to achieve high performance on every measure of evaluation in Fig. 9 with the minimum values of MAE and MSE.

As illustrated in Table 6, XGBoost has the highest performance with the largest number of highest R2 values meeting the majority of the Strategies (with a largest R2 of 1.0 in Strategic Load Growth). It has a good balance between speed, accuracy, and interpretability (when used in conjunction with SHAP) and can be easily deployed to real world applications with moderate levels of computation. It is especially strong in Valley Filling, Strategic Conservation and Flexible Load Shape.

Model comparison and aggregate evaluation

The MAE heatmap shows a graphical representation of the absolute error of prediction of each machine learning model at varying Demand Response (DR) approaches. Smaller values are an indicator of a good model. XGBoost, and Random Forest exhibit low values of MAE at all times, especially when using Strategic Load Growth and Peak Clipping strategy. By comparison, KNN and Linear Regression performance tends to demonstrate lower MAE in most of the strategies, meaning that they are less accurate. These findings indicate that ensemble models, including XGBoost, are more appropriate in reducing absolute forecast errors when forecasting EV charging, as in Fig. 10.

The MSE heatmap shows the magnitude of squared error between models and strategies of data reduction (DR). Similar to MAE, the reduced values of MSE are indicative of improved model reliability. Once again, XGBoost and Random Forest have the lowest MSEs especially in the case of Flexible Load Shape and Valley Filling. The large MSE values of KNN and Linear Regression support the fact that they are not very effective as indicated in the confusion matrix in Fig. 11. In that, MSE also punishes bigger errors more, the fact that tree-based models are doing so strongly reflects their reliability in the context of situations when one should not take big forecast uncertainties.

Figure 12 gives all the Demand Response (DR) strategies in terms of their performance using the heatmap of Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE). As we observe, there is no single model that can be always the best in all strategies. XGBoost would perform best when it comes to Load Shifting (5.71%), and Random Forest, when it comes to Strategic Conservation (5.20%), and Flexible Load Shape (6.43%). In the majority of the cases and Valley Filling and Load Shifting in particular, the error rates recorded by the SVR and KNN are high. Just like the earlier technology, although linear regression is not complex, it does not perform in any strategy yet it does not fall behind. This variance is noteworthy in highlighting the autonomy of particular models’ selection in EV demand forecasting, and the benefit of population models like XGBoost and Random Forest in achieving lesser forecasting error in an environment with limited resources.

Figure 13 shows a normalized view of Root Mean Squared Error of all models and Demand Response (DR) strategies in the CVRMSE heatmap, which may provide a comparative analysis of the reliability in forecasting. XGBoost will achieve low or minimal values of the CVRMSE across all the strategies and lowest error (0.053) in Peak Clipping and good precision in Load Shifting and Load Growth strategies. KNN is not so advantageous in Valley Filling (0.072), yet, more successful, in regards to Load Shifting (0.059) and Strategic Load Growth (0.065). In such a situation, SVR (essentially competitive) lags particularly in strategies growth load (0.198), a fact that suggests that an impoverished generalizing occurs in such a scenario. The errors of random Forest are equal but higher especially in Peak Clipping and Flexible Load shape. Lineal Regression, though being simple in nature, has moderate performance and performs lower as compared to ensemble in most cases. The results justify the fact that the number of tree-based ensemble models is limited to scale continuously and make a stable, scalable prediction in a low-computation setting applied to EV charging.

The R2 heatmap (calculated using min-max R2 values, reported as R2 due to its meaning) indicates the capability of every model to describe the variation in energy consumption among various strategies of demand response (DR). The high R2 is the better fit. The XGBoost performs better than all models particularly in Strategic Load Growth with the next in line being the Random Forest. KNN and Linear Regression score relatively lower. Such a visualization makes it clear that ensemble models are not only precise in terms of error measures but also useful in reflecting the underlying data trends of relevance to the DR optimization in EV charging as illustrated in Fig. 14.

Figure 15 suggests the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) using the model and Demand Response (DR) strategy. This is a performance comparison of five machine learning models, including Linear Regression, Random Forest, Support Vector Regression (SVR), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) and XGBoost applied to the different DR strategies including Peak Clipping, Valley Filling, Load Shifting, Strategic Conservation, Strategic Load Growth and Flexible Load Shape. The MAE (average value of the errors in perception) is indicated by the y-axis but not by direction. The smaller the MAE, the better the work of the model i.e. the lesser errors made in predictions. The x-axis involves the alternatives DR schemes to streamline EV charging. It is not hard to interpret the figure that the XGBoost outperforms the other models since in all the strategies of DR, the XGBoost had the minimum value of MAE. The KNN and the Linear Regression are most apt to give a larger MAE, and, therefore, will not be as precise. Random Forest and SVR are not bad and Random Forest performs a little better than SVR in most of the strategies. As can be seen in the graph, different DR strategies have different effects on the performance of each model, with a relatively higher MAE when the Strategic Load Growth strategy is applied, especially in the Linear Regression and SVR. Overall, it is evident that XGBoost will always remain the most universal model in the optimization of EV charging, whereby the lowest MAE values are obtained through the application of different demand response (DR) methods.

Figure 16 is an illustration of the Mean Squared Error (MSE) of the different models of the different Demand Response (DR) strategies. The plot may provide information about how different machine learning models perform the role of predicting the changes of the energy consumption of the chosen demand response (DR) strategy. The comparison between the models is: Linear Regression, Random Forest, Support Vector Regression (SVR), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) and XGBoost. Considering the graph, the models can be noted to have similar performance even with the strategies used though some variation is seen in their performances. Otherwise, the linear regression and Random Forest models demonstrate high values of MSE in the majority of strategies, whereas SVR and KNN are the models which demonstrate rather justified performance in terms of reducing the MSE. This could indicate that SVR and KNN can be more successful in modeling the trends of demand response (DR) strategies especially in load shifting and peak clipping strategies. The XGBoost model shows a similar performance and it does not show any significant performance over other models. The comparison can be used to select the most appropriate model out of the numerous DR strategies, and MSE may also be used as one of the measures of the model performance.

Figure 17 CVRMSE bar plot illustrates the relative performance of 5 machine learning models including Linear Regression, Random Forest, SVR, KNN, and XGBoost, regarding the Demand Response (DR) strategy 6. Interestingly, the XGBoost has a decreasing percentage in the CVRMSE which confirms its stability and maximum accuracy in diverse conditions of energy shifting. As comparison, SVR and Linear Regression are more erroneous and variable particularly in Strategic Load Growth and Peak Clipping. Some less consistency is also seen in KNN compared to Random Forest which is competitive, with a somewhat higher variance. Generally speaking, the ensemble algorithms, especially XGBoost are more efficient as compared to radial basis function, traditional and kernel-based models and this is indicative of its sufficiency as resources-limited predictive EV battery charging systems.

According to the MAPE bar plot in Figs. 5 and 18 machine learning models were tested in terms of their predictive ability against the six demand response strategies. XGBoost also displays the lowest percentage of errors under any circumstances and is, therefore, the most appropriate in model prediction of the EV load. Although SVR and Random Forest are effective at some strategies, they reach value of MAPE, which is higher than NN, when Strategic Load Growth and Peak Clipping is used, and therefore would indicate that it is more fragile in some case of peak demand. And such methods like Linear Regression and KNN are neither that good and cannot offer the precision which is required to perform fine-grained forecasting. The results illustrate the applicability of the gradient boosting algorithms like the XGBoost which can be implemented in real time, operations with constraint resources like in energy operations where the accuracy is the decisive factor.

Figure 19 shows the R2 score of five Machine Learning models i.e., Linear Regression, Random Forest, Support Vector Regression (SVM), K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN), and XG Boost on six demand responses (DR) strategies i.e. Peak Clipping, Valley Filling Load Shifting, Strategic Conservation, Strategic Load Growth and Flexible Load Shape. The results show that XGBoost had the highest R2 values in all the DR strategies hence the highest predictive accuracy. Random Forest and SVR are also not bad with high scores in most of the strategies. Quite the contrary, Linear Regression and KNN are not so good, particularly in more complex strategies like Load Shifting and Flexible Load Shape. Strategic Load Growth is a plan of which the accuracy can be described almost perfectly with the help of XGBoost, which means that the strategy is highly predictable. Overall, the figure demonstrates that to effectively use demand response (DR) implementation, it is necessary to apply sophisticated models, including XGBoost and Random Forest, to make effective predictions, especially in situations when load patterns are complicated and volatile.

Composite matrix analysis. In order to combine the outcomes of the performance of each model along with the MSE and MAE scores of each model in the seven DR strategies, they were combined. As it was observed, the XGBoost and the Random Forest models were more accurate in comparison to the other models, outperforming them on the generalization aspect as well. XGBoost had the lowest values of MAE and MSE, and the second nearest was Random Forest. R2 values gave the most difference in the model and XGBoost has usually received a score of above 0.85. The findings have indicated the suitability of tree-based ensemble process in the implementation of energy forecasting in the DR process, especially in the consideration that when implementing such models, limited computer ability must be considered.

Discussion

The current paper is devoted to the idea of how machine learning (ML) model can assist in optimizing charging of electric vehicles (EVs) with the help of Demand Response (DR) in low-computational-power systems. Charging loads in electric vehicles (EVs) are increasingly popular, so they can efficiently control them to avoid grid congestion and to improve energy use. This paper relies on a new methodology that relies on the Electric Vehicle Charging Data Set that is made available on Kaggle and is aimed at estimating the amount of kWh that will be given out after charging the EV. Optimization of predictive models to enable their implementation on resource-constrained computing platforms, including embedded controllers or edge devices, is one of the main issues considered in the context of the given work. Randomized down-sampling is used in this work to reduce the size of the dataset in a way that makes it memory-efficient in low-power systems and at the same time, has high predictive accuracy. This information will consist of actual charging data of EVs, such as the time when the event of charging took place and such attributes as time of the day, weekday, month, etc., which are essential in EV charging behavior. The authors also perform Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) to process the data and find out the correlation between variables and characteristics of important variables, which improves the predictive quality of the model. In order to enhance the accuracy of the model further, feature engineering is also resorted to including the extraction of temporal features like hour, weekday, month and day. These were other attributes which were applied to show the repetitive trend in the charging nature of EVs thus enhancing the viability of the overall model. The given paper is dedicated to the evaluation of many data reduction (DR) algorithms, such as Peak Clipping, Valley Filling, and Load Shifting that are trained with the help of diverse machine learning models: Linear Regression, Random Forest, Support Vector Regression (SVR), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) and XGBoost.

As the results demonstrate, XGBoost is better than the other models in most of the DR strategies, and the model scores the highest R2, 0.943 in Valley Filling and 0.975 in Strategic Conservation, respectively. The results indicate that ensemble models, including XGBoost, may also be a useful real-time DR model in low-computational environments. On the other hand, the R-squares of both linear regression and KNN are lower, and it means that simpler models cannot be employed to complete this kind of tasks. These findings are indicative of the fact that machine learning models are capable of maximizing EV charging even in resource constrained environments and that more complex models, like those provided by the XGBoost, provide more sophisticated predictive behavior in load leveling during demand response (DR) strategies. One of the most important questions that have been raised during the research is the need to have a system that has limited resources to optimize on and is real-time. However, it is also a fact that despite the fact that deep learning and reinforcement learning methods are also known to be effective, in the majority of experiments, they are computationally infeasible, and are not amenable to low-power environments. The best ML models like XGBoost can be optimized to prove that there can be a trade-off between predictive performance and computational cost. Besides, the study stresses the need to ensure machine learning (ML) models are interpretable, especially when applied in practice and not in a laboratory. Decision-making has to be quite transparent. The findings also inform the importance of lightweight models in the process of realizing real-time EV charging optimization in embedded systems. Even though these deep learning models are very accurate, conventional model is normally computationally costly and hence cannot be scaled to edge devices or embedded systems. As this paper has shown, ensemble methods, particularly XGBoost, have a great accuracy and can run the computational operations at a good rate which is essential in meeting the state-of-the-art demands of smart grids and charging units of electric vehicles with low-latency and high-throughput processing. In addition, the paper highlights the importance of selecting and designing features with the available data set attentively. The identification of significant time-related variables, including the time of day, the day of the week, and the month, helped the authors to get the models closer to making correct predictions about EV charging behavior. Temporal features enable introduction of cyclical structures of charging session that is essential in DR strategies to simplify scheduling and loading. It is also hypothesized in the paper that the existing literature on EV charging optimization has brought about positive findings but the prevailing models have been computationally intense, and thus are not applicable in real-time on low-intensity systems. This research closes this gap because it proposes a feasible solution that can be incorporated in actual practice of low-computational-power. The authors prove that they are able to reach a high level of prediction accuracy and meet the requirements of low-resource settings using models like XGBoost and Random Forest.

The paper provides a direction of further research to refine these models and use them with larger data sets or treat it in real-time. Further development of the models with the inclusion of other factors which may influence the outcome, like weather conditions, type of vehicle, or user behavioral patterns into the future work can be worthwhile to increase the predictive power of the models. Moreover, relations between real-time data flows and applying models to operating electric vehicle (EV) charging stations would enable gaining valuable insights regarding the practical problems of deploying a machine learning (ML) model in real life as well. This research proves that machine learning algorithms, that is, XGBoost, can be applied to optimize the charging of electric vehicles (EVs) in environments with low computation power. To simplify its predictive representations, the study employs down-sampling and lightweight models, resulting in a predictive performance one that is not affected even in cases where resources are limited. The suggested solution is dynamic and provides the implementation-viable answer to the arising challenge of ensuring the balancing of EV charging costs in a cost-effective manner and stabilizing the grid and maximizing the energy efficiency. The other characteristic that can be mentioned in this publication is the opportunities of machine learning in relation to the future of smart grids and smart EV infrastructure management.

Conclusion

Lastly, this paper proposes a new approach to the optimization of charging electric vehicles (EV) using machine learning (ML) models, especially Demand Response (DR) in low-computational-power systems. As the introduction of electric vehicles has been increasing slowly, the competent handling of the subsequent increase in the load on electric grids has now become a major concern. It is noted that even in situations involving resources limitations the application of machine learning models can still be used to optimise the process of EV charging without it impacting on predictive performance. The study relies on the Electric Vehicle Charging Dataset, and is provided on Kaggle by DC Business Consultants, which can be found with ease and accessed by a study with real-world information about charging, with time stamps and various characteristics, including time of day, weekday and month. With the help of the feature engineering and Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA), the constructs of time have been included to show the repetitive nature of the charging behavior, including hour, weekday, month, and day. These features improved the quality of the models to a significant extent because they became more familiar with the peculiarities of EV charging sessions. The other significant contribution of this work is the creation of a randomized down-sampling algorithm resulting in the smaller dataset size that can be executed on a low-computational-power machine, e.g. embedded system or an edge computing platform. This ensures that the models are very useful in low resource settings without the prediction being corrupted. The study compares efficacy of five machine learning-based models namely, Linear Regression, random forest, Support Vegetable Regression (SVR), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), and XGBoost in relation to three common demand response (DR) techniques; peak clipping, valley filling, and load shifting. These results show that XGBoost is the best model compared to the other models in terms of the scores of the R2 which include the largest numbers of 0.943 and 0.975 in the instances of the Valley Filling and Strategic Conservation, respectively, hence showing that it is a good model in terms of predicting the amount of the energy (kWh delivered) being used when the processes of EV charging are being conducted. Linear Regression and KNN, in their turn, are not that successful as the R2 is less than 0.5 in most instances. The findings suggest that stronger ensemble algorithms, including XGBoost which balance between predictive accuracy and rapid calculation, are to be used.

This research has also stated the applicability of the use of machine learning in real-time DR applications in EV infrastructure management. The study seeks to address a literature gap as many prior studies have employed resource-intensive models that cannot be deployed in the real-world practice to edge devices or embedded systems due to their orientation to low-computational-power systems. Besides, the results show that even models like XGBoost, with their computational constraints, can reach a high level of accuracy in predicting the charging of the electric vehicles (EVs), which is why XGBoost can be an appropriate solution in the future smart grid application.

Future work

Moreover, research model can also be scaled and can be used in bigger datasets and real-time systems in future. It is anticipable that, with the creation of more and more data and the further evolution of technology, models will be further streamlined to become more effective in their calculations and predictive abilities. More research can also be carried out on the level of other factors such as type of motor vehicle, weather and user behavior that can be put together to improve the accuracy and strength of the models. This type of models could be further verified on the real world in EV charging stations, and the workability could be studied. Finally, the paper has a strong contribution to the EV charging optimization body since it shows that machine learning algorithms, specifically, XGBoost, can be successfully implemented under limited resources to optimize EV charging and support demand response strategies. The work does not only provide a solution to solve some of the challenges, including real-time energy management, but also preconditions the further development in the field of smart grid technologies and EV infrastructure management.

Data availability

The data sets that were used/or analyzed in the present study are provided by the respective author on a reasonable request.

References

Barreto, R., Faria, P. & Vale, Z. Electric mobility: an overview of the main aspects related to the smart grid. Electronics 11 (9), 1311 (2022).

Amezquita, H., Guzman, C. P. & Morais, H. Forecasting electric vehicles’ charging behavior at charging stations: a data science-based approach. Energies 17 (14), 19961073 (2024).

Mohsenimanesh, A. & Entchev, E. Charging strategies for electric vehicles using a machine learning load forecasting approach for residential buildings in Canada. Appl. Sci. 14 (23), 11389 (2024).

Zhang, Z. et al. Federated reinforcement learning for real-time electric vehicle charging and discharging control. In 2022 IEEE Globecom Workshops (GC Wkshps) (IEEE, 2022).

Zhang, T., Peng, Q. & Zeng, S. Predicting EV charging demand in Renewable-Energy-Powered grids using explainable machine learning. Sustainability 17 (9), 4158 (2025).

Damodarin, U. M. et al. Smart electric vehicle charging management using reinforcement learning on FPGA platforms. Sensors 25 (8), 2585 (2025).

Li, D. et al. An electrical vehicle-assisted demand response management system: a reinforcement learning method. Front. Energy Res. 10, 1071948 (2023).

Liu, J. et al. Personalized federated management and load balancing for multiple charging stations. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. (2025).

Lim, Y., Bae, S. & Moon, J. Optimal control scheme of electric vehicle charging using combined model of XGBoost and cumulative prospect theory. Energies 17 (24), 6457 (2024).

Shin, J. et al. Optimized breast cancer classification via SHAP-Based feature selection and weighted voting ensemble learning. IEEE Open. J. Comput. Soc. (2025).

Khan, W. et al. Hybrid XGBoost–LSTM model for State-of-Health prediction of Lithium-Ion batteries under different thermal conditions. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2025, 101218 (2025).

Aoun, A. et al. Dynamic charging optimization algorithm for electric vehicles to mitigate grid power peaks. World Electr. Veh. J. 15, 7 (2024).

Park, K. & Moon, I. Multi-agent deep reinforcement learning approach for EV charging scheduling in a smart grid. Appl. Energy. 328, 120111 (2022).

Barman, P. et al. Renewable energy integration with electric vehicle technology: a review of the existing smart charging approaches. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 183, 113518 (2023).

Balakumar, P., Vinopraba, T. & Chandrasekaran, K. Deep learning based real time demand side management controller for smart Building integrated with renewable energy and energy storage system. J. Energy Storage. 58, 106412 (2023).

Rana, M. T. et al. Enhancing sustainability in electric mobility: exploring blockchain applications for secure EV charging and energy management. Comput. Electr. Eng. 119, 109503 (2024).

Xu, S. et al. Decentralized charging control strategy of the electric vehicle aggregator based on augmented lagrangian method. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 104, 673–679 (2019).

Belaid, M., Beid, S. E. & Hatim, A. Optimizing urban electric vehicle charging infrastructure selection: an approach integrating GPS data, battery levels, and energy availability. IFAC-PapersOnLine 58, 392–397 (2024).

Liao, Y. et al. Impacts of charging behavior on BEV charging infrastructure needs and energy use. Transp. Res. Part. D: Transp. Environ. 116, 103645 (2023).

Paneru, B. et al. Advancing sustainable mobility: dynamic predictive modeling of charging cycles in electric vehicles using machine learning techniques and predictive application development. Syst. Soft Comput. 6, 200157 (2024).

Jamil, U. et al. Artificial intelligence-driven optimal charging strategy for electric vehicles and impacts on electric power grid. Electronics 14 (7), 1471 (2025).

Mazhar, T. et al. Electric vehicle charging system in the smart grid using different machine learning methods. Sustainability 15 (3), 2603 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. Coordinating flexible demand response and renewable uncertainties for scheduling of community integrated energy systems with an electric vehicle charging station: a bi-level approach. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy. 12 (4), 2321–2331 (2021).

Lin, J. et al. Research on demand response of electric vehicle agents based on multi-layer machine learning algorithm. IEEE Access. 8, 224224–224234 (2020).

Gu, C. et al. Learning and optimization for price-based demand response of electric vehicle charging. In 2024 American Control Conference (ACC) (IEEE, 2024).

Hassan, M. Machine learning optimization for hybrid electric vehicle charging in renewable microgrids. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 13973 (2024).

Lan, T. et al. An advanced machine learning based energy management of renewable microgrids considering hybrid electric vehicles’ charging demand. Energies 14 (3), 569 (2021).

Palaniyappan, B. & Vinopraba, T. Dynamic pricing for load shifting: reducing electric vehicle charging impacts on the grid through machine learning-based demand response. Sustainable Cities Soc. 103, 105256 (2024).

López, K. L., Gagné, C. & Gardner, M. A. Demand-side management using deep learning for smart charging of electric vehicles. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid. 10 (3), 2683–2691 (2018).

Shanmuganathan, J. et al. Deep learning LSTM recurrent neural network model for prediction of electric vehicle charging demand. Sustainability 14 (16), 10207 (2022).

Recalde, A. et al. Machine learning and optimization in energy management systems for plug-in hybrid electric vehicles: a comprehensive review. Energies 17 (13), 3059 (2024).

Liu, H. I. et al. Lightweight deep learning for resource-constrained environments: a survey. ACM Comput. Surveys. 56 (10), 1–42 (2024).

Sandler, M. et al. Mobilenetv2: inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference On Computer Vision And Pattern Recognition (2018).

Banbury, C. et al. Micronets: neural network architectures for deploying Tinyml applications on commodity microcontrollers. Proc. Mach. Learn. Syst. 3, p517–532 (2021).

Cho, Y., Kim, D. & Kim, J. Data-driven demand response aggregation for public EV charging stations: overcoming decoupled governance challenges. Appl. Energy. 402, 126986 (2026).

Jin, R. et al. Deep reinforcement learning-based strategy for charging station participating in demand response. Appl. Energy. 328, 120140 (2022).

Alfaverh, F., Denaï, M. & Sun, Y. Electrical vehicle grid integration for demand response in distribution networks using reinforcement learning. IET Electr. Syst. Transport. 11 (4), 348–361 (2021).

Gholizadeh, Nastaran, “Electric Vehicle Charging Dataset”, Mendeley Data, V1, (2024) https://doi.org/10.17632/5zrtmp7gwd.1

Singh, R. Machine learning-based energy management and power forecasting in grid-connected microgrids with multiple distributed energy sources. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 19207 (2024).

Punyavathi, R. et al. Sustainable power management in light electric vehicles with hybrid energy storage and machine learning control. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 5661 (2024).

Panda, S. et al. Comprehensive framework for smart residential demand side management with electric vehicle integration and advanced optimization techniques. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 9948 (2025).

Singh, A. R. et al. A blockchain consortium-based framework to enhance interoperability, standardization, and secure demand response management in smart grid applications. Results Eng. 2025, 106056 (2025).

Singh, A. R. et al. A hybrid demand-side policy for balanced economic emission in microgrid systems. iScience 28, 3 (2025).

Singh, A. R. et al. Optimizing demand response and load balancing in smart EV charging networks using AI integrated blockchain framework. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 31768 (2024).

Aziz, A. et al. Advanced AI-driven techniques for fault and transient analysis in high-voltage power systems. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 5592 (2025).

Varshney, S. et al. Novel control strategies for electric vehicle charging stations using stochastic modeling and queueing analysis. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 21391 (2025).

Renhai, F. et al. Adaptive non-parametric kernel density Estimation for under-frequency load shedding with electric vehicles and renewable power uncertainty. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 11499 (2025).

Kumar, B. A. et al. A novel strategy towards efficient and reliable electric vehicle charging for the realisation of a true sustainable transportation landscape. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 3261 (2024).

Kumar, B. A. et al. Hybrid genetic algorithm-simulated annealing based electric vehicle charging station placement for optimizing distribution network resilience. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 7637 (2024).

Singh, A. R. et al. Electric vehicle charging technologies, infrastructure expansion, grid integration strategies, and their role in promoting sustainable e-mobility. Alexandria Eng. J. 105, 300–330 (2024).

Kumar, B. A. et al. Enhancing EV charging predictions: a comprehensive analysis using K-nearest neighbours and ensemble stack generalization. Multiscale Multidiscipl. Model. Exp. Des. 7 (4), 4011–4037 (2024).

Zheng, Y. et al. Intelligent regulation on demand response for electric vehicle charging: a dynamic game method. IEEE Access. 8, 66105–66115 (2020).

Nagarajan, K. et al. Enhanced Wombat optimization algorithm for multi-objective optimal power flow in renewable energy and electric vehicle integrated systems. Results Eng. 25, 103671 (2025).

Varshney, S. et al. Stochastic modeling of electric vehicle infrastructure using queueing-theoretical approach. Results Eng. 25, 104149 (2025).

Nadimuthu, L. P. R. et al. Feasibility of renewable energy microgrids with vehicle-to-grid technology for smart villages: a case study from India. Results Eng. 24, 103474 (2024).

Aggarwal, S. et al. Revolutionizing load management: a novel technique to diminish the impact of electric vehicle charging stations on the electricity grid. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 65, 103784 (2024).

Sabyasachi, S. et al. Reimagining E-mobility: a holistic business model for the electric vehicle charging ecosystem. Alexandria Eng. J. 93, 236–258 (2024).

Ravindran, M. A. et al. A novel technological review on fast charging infrastructure for electrical vehicles: Challenges, solutions, and future research directions. Alexandria Eng. J. 82, 260–290 (2023).

Mohamed, N. et al. Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML)-based Information security in electric vehicles: a review. In 2023 5th Global Power, Energy and Communication Conference (GPECOM) (IEEE, 2023).

Mohanty, S. et al. Demand side management of electric vehicles in smart grids: a survey on strategies, challenges, modeling, and optimization. Energy Rep. 8, 12466–12490 (2022).

Panda, S. et al. A comprehensive review on demand side management and market design for renewable energy support and integration. Energy Rep. 10, 2228–2250 (2023).

Panda, S. et al. Residential demand side management model, optimization and future perspective: a review. Energy Rep. 8, 3727–3766 (2022).

Babar, R. et al. Operational Strategies for EV fast-charging and their impact on power grid and renewable integration. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2025, 01445987251352551 (2025).

Singh, A. R. et al. Enhanced CPCV algorithm for improving power quality in electric vehicle battery charging. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 23896 (2025).

Singh, A. R. et al. Design and performance evaluation of a multi-load and multi-source DC-DC converter for efficient electric vehicle power systems. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 25718 (2024).

Singh, A. R. et al. A high-efficiency poly-input boost DC–DC converter for energy storage and electric vehicle applications. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 18176 (2024).

Singh, A. R. et al. Advanced microgrid optimization using price-elastic demand response and greedy rat swarm optimization for economic and environmental efficiency. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 2261 (2025).

Rampelli Manojkumar, C. K., Reddy, T., Yuvaraj, M., Bajaj, V. & Blazek, V. Optimized rule-based energy management for AC/DC hybrid microgrids using price-based demand response, e-Prime. Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 14, 101132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prime.2025.101132 (2025).

Al-Amayreh, M., Alamayreh, A. & Amal, A. Impact of EV charging strategies on solar-powered residential buildings: unidirectional vs. bidirectional charging in Jordan. Discover Sustain. 6 (1), 407 (2025).

Cui, D. et al. Enhancing Short-Term electricity forecasting with advanced machine learning techniques. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2025, 1–41 (2025).

Blinov, I. et al. Advanced long short-term memory-based forecasting of electricity imbalances in the Ukrainian power system: enhancing accuracy and stability with comparative model analysis. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2025, 01445987251360272 . (2025).

Zafar, A. et al. Enhanced solar power forecasting in smart grids using a hybrid autoencoder and long short-term memory model. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2025, 01445987251360490 (2025).

Al-Suod, Mahmoud, M. S. et al. Forecasting energy consumption of a mining plant using artificial neural networks. IEEE Access. (2025).

Molu, R. J. et al. Advancing short-term solar irradiance forecasting accuracy through a hybrid deep learning approach with Bayesian optimization. Results Eng. 23, 102461 (2024).

Mohammad, A. A. et al. Intelligent data-driven task offloading framework for internet of vehicles using edge computing and reinforcement learning. Data Metadata. 4, 521–521 (2025).

Al-Daoud, K. et al. Explainability in AI using fuzzy inference systems for the regression problem. Appl. Math. 19 (5), 973–987 (2025).

Samanta, I. et al. A hybrid approach for power quality event identification in power systems: Elasticnet Regression decomposition and optimized probabilistic neural networks. Heliyon 10, 18 (2024).

Ibrahim, A. et al. Regression models for predicting gamified educational outcomes. In 2024 International Telecommunications Conference (ITC-Egypt) (IEEE, 2024).

Funding

No funding was received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ali Mujtaba Durrani, Azzam Ul Asar, Abdul Aziz: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Investigation, Writing- Original draft preparation. Wajid Khan, Muhammad Zain Yousaf: Data curation, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Writing - Review & Editing. Fakhar Anjam, Umar Farooq, Mustafa Abdullah, Mohammad Shabaz: Project administration, Supervision, Resources, Writing - Review & Editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Durrani, A.M., Asar, A.U., Aziz, A. et al. Lightweight machine learning framework using temporal features for electric vehicle demand response forecasting on edge devices. Sci Rep 16, 947 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30465-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30465-9