Abstract

Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is a major public health concern. However, its relationship with the long-term mortality risk remains underexplored in the general population. We aimed to examine the association between liver fibrosis, assessed using the age-adjusted Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) residual index, and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in individuals with MASLD. This cohort study included 134,686 adults diagnosed with MASLD via ultrasonography and metabolic abnormalities during health screenings at two Korean centers between 2002 and 2022. The participants were followed up for mortality outcomes using the National Death Registry. The FIB-4 index was calculated from age, AST, ALT, and platelet count adjusted for age using residual modeling. Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate the hazard ratios (HRs) for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, adjusting for sociodemographic, behavioral, and clinical covariates. Age-stratified analyses were also performed. During a mean follow-up of 11.2 years, 2,129 all-cause and 348 cardiovascular deaths occurred. A higher age-adjusted FIB-4 index was associated with increased risk of all-cause mortality (HR 1.489, 95% CI 1.353–1.639) and cardiovascular mortality (HR 1.478, 95% CI 1.175–1.860). These associations persisted after adjustment. In stratified analyses, all-cause mortality associations were significant in both age groups, whereas cardiovascular mortality was significant only in those aged > 39 years. The age-adjusted FIB-4 index was independently associated with increased risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with MASLD. Assessing liver fibrosis using FIB-4 may provide prognostic information beyond traditional cardiometabolic risk factors in this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), previously referred to as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), is the most prevalent chronic liver disease globally, affecting approximately one-third of the adult population1,2. Its rising incidence is largely driven by the increasing burden of obesity, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome3,4. Although historically viewed as a liver-specific disorder, MASLD is now recognized as a systemic condition strongly linked to extrahepatic complications, particularly cardiovascular disease (CVD), which remains the leading cause of death in this population5,6.

Among the histological features of MASLD, liver fibrosis is the strongest predictor of long-term outcomes, surpassing its prognostic importance7. The Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) index, a simple noninvasive score calculated from age, aminotransferase levels, and platelet count, is widely used to estimate liver fibrosis in both clinical and research settings8. Elevated FIB-4 scores have been associated not only with adverse hepatic outcomes, such as cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, but also with increased risk of cardiovascular events and mortality7,9,10,11.

However, despite its widespread use, the diagnostic accuracy of FIB-4 is limited by age-dependent variability and a substantial false-positive rate in the general population. Recent evidence indicates that nearly one-third of individuals with elevated FIB-4 values do not have advanced fibrosis12. These limitations highlight the importance of refining FIB-4–based risk stratification approaches, such as age adjustment, when applying the score to large population-based cohorts.

Despite these associations, limited data exist on whether FIB-4 can stratify all-cause and cardiovascular mortality risks, specifically among individuals with MASLD. Previous studies have often evaluated composite cardiovascular outcomes and all-cause mortality, and few have directly compared cardiovascular mortality risks between high and low FIB-4 levels in large, well-characterized MASLD cohorts7,10,11,13.

Cardiovascular mortality was selected as a primary outcome because CVD is the leading cause of death among individuals with MASLD, and fibrosis severity has been closely linked to cardiometabolic abnormalities and cardiovascular outcomes in prior research. Therefore, evaluating cardiovascular mortality provides clinically meaningful insight into the prognostic value of FIB-4 in this population.

Given the high prevalence of MASLD and the simplicity of calculating FIB-4 from routine laboratory tests, clarifying its prognostic value for mortality risk stratification has important clinical implications for the early identification and targeted management of high-risk patients. We therefore hypothesized that a higher FIB-4 index is independently associated with an increased risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality among individuals with MASLD.

Methods

Ethics statement

Our study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Kangbuk Samsung Hospital, which waived the requirement for informed consent because only de-identified data routinely collected during health screening examinations were used (IRB No: KBSMC2025-07-012). All procedures were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations and with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study population

This study was conducted using data from the Kangbuk Samsung Health Study, a cohort study of Korean adults aged ≥ 18 years who attended annual or biennial comprehensive health examinations at the Total Healthcare Center of Kangbuk Samsung Hospital in Seoul and Suwon, South Korea, as previously described14.

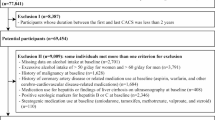

A total of 849,341 participants were enrolled between 2002 and 2022 (Fig. 1). For the present analysis, we included participants who underwent abdominal ultrasonography and met the diagnostic criteria for MASLD at baseline. MASLD was defined as the presence of hepatic steatosis on ultrasonography in individuals with at least one metabolic abnormality (e.g., central obesity, hypertension, or impaired glycemia) and the absence of excessive alcohol consumption (≥ 30 g/day for men and ≥ 20 g/day for women).

To further eliminate confounding from liver conditions unrelated to MASLD, participants with hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positivity, hepatitis C virus antibody (anti-HCV) positivity, or evidence of chronic liver disease were excluded.Participants with missing data on key variables—including FIB-4 components (AST, ALT, platelet count, age), alcohol intake, and mortality status—were also excluded.

FIB-4 values ≥ 10 were excluded because such extreme values typically represent laboratory error, acute illness, or severe hematologic abnormalities rather than stable MASLD-related fibrosis. This approach has been adopted in prior population-based studies to prevent undue distortion of model estimates.

We then applied the following first-stage exclusion criteria:

(1) FIB-4 values ≥ 10 indicate potentially implausible or extreme outliers (n = 15).

(2) History of cancer (n = 3,705).

(3) History of coronary artery disease or use of related medications, including aspirin, warfarin, or medications for stroke or heart disease (n = 10,595).

(4) Current use of medications for hepatitis or evidence of chronic liver disease on ultrasonography (n = 285).

(5) HBsAg or anti-HCV positivity (n = 2,887).

(6) Current use of medications potentially associated with liver toxicity, including amiodarone, tamoxifen, methotrexate, valproate, or systemic corticosteroids (n = 359).

After accounting for overlapping exclusions, 17,005 participants were excluded, leaving 152,499 participants for analysis.

As a second-stage exclusion, we further excluded 17,813 participants with a follow-up duration of < 2 years from baseline to death or censoring (< 730.5 days) to reduce potential reverse causation bias. This lag-time approach is widely used in epidemiologic studies to minimize the influence of preclinical disease15,16,17.

The final study population consisted of 134,686 participants with MASLD who had at least 2 years of follow-up.

Definitions of MASLD and the liver fibrosis score

MASLD at baseline was defined according to international consensus criteria. MASLD was diagnosed in participants who met the following criteria:

-

(i)

Evidence of hepatic steatosis on ultrasonography.

-

(ii)

Presence of at least one metabolic abnormality.

-

(iii)

Absence of excessive alcohol consumption.

Abdominal ultrasonography was performed using a Logic Q700 MR 3.5-MHz transducer (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA) by experienced radiologists who were blinded to the study aims. Images were obtained conventionally with the participants in the supine position, with their right arms raised above their heads18. Hepatic steatosis was defined as a diffuse increase in fine echoes in the liver parenchyma compared to that in the kidney or spleen parenchyma19. The interobserver and intraobserver reliability for ultrasonographic diagnosis of steatosis was high, with kappa statistics of 0.74 and 0.94, respectively20. Transient elastography (FibroScan) data were not available in this cohort because it was not part of the routine health examination program.

Metabolic dysfunction was defined as the presence of at least one of the following five criteria:

(1) Central obesity (waist circumference ≥ 94 cm for men or ≥ 80 cm for women).

(2) Elevated blood pressure (systolic ≥ 130 mmHg or diastolic ≥ 85 mmHg or use of antihypertensive medication).

(3) Dysglycemia (fasting glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL, HbA1c ≥ 5.7%, or use of diabetes medication).

(4) Elevated triglyceride levels (≥ 150 mg/dL or use of lipid-lowering medications).

(5) Low HDL cholesterol (< 40 mg/dL in men or < 50 mg/dL in women or use of lipid-lowering medications).

Although BMI ≥ 23 kg/m² is often included in MASLD definitions for Asian populations, it was not applied in the present study because individual race or nationality could not be determined owing to data anonymization. Therefore, central obesity was defined solely based on waist circumference.

Excessive alcohol consumption was defined as an average daily intake of ≥ 30 g for men or ≥ 20 g for women. Participants who exceeded these thresholds were excluded from the MASLD definition.

The FIB-4 index was calculated as (age × AST) divided by (platelet count × √ALT), where AST and ALT are serum liver enzyme levels measured in units per liter (U/L), and platelet count is expressed in 10⁹/L. To account for the strong correlation between FIB-4 and age, we generated an age-adjusted residual variable by regressing FIB-4 on age and extracting residuals. This variable was used as the primary exposure in the survival analysis to isolate liver-related risks, independent of age.

Mortality outcomes

Mortality data were obtained from the National Death Registry maintained by Statistics Korea. All-cause mortality was defined as death from any cause during follow-up based on the presence of a recorded ICD-10 code in either of the two mortality fields in the linked dataset. The date of death was derived from separate year, month, and day variables and converted into a standard date format.

Cardiovascular mortality was defined as death with an ICD-10 code in the range of I00–I99, indicating disease of the circulatory system. This classification was applied if any of the available death codes began with the letter “I” followed by two digits (e.g., I21 for myocardial infarction).

Statistical analysis

Cox proportional hazards regression was used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between age-adjusted FIB-4 residual variables and the risk of cardiovascular mortality. The proportional hazards assumption was evaluated using Schoenfeld residuals tests, and no violations were detected in any of the fitted models. The time scale was defined as the period from the date of the baseline health examination to the date of death or the end of follow-up (December 31, 2022), whichever occurred first. Survival time was right censored at the end of the follow-up period for the individuals who survived.

Missing values for key categorical covariates, including regular physical activity, educational attainment, obesity, smoking status, and marital status, were handled using multiple imputation by chained equations under the missing-at-random assumption. The proportion of missing data for imputed variables was generally low, ranging from 0.1% (obesity) to 15.6% (educational attainment). Detailed missingness patterns are presented in Supplementary Table S1. Ten imputed datasets were generated using logistic regression models, with age, sex, and FIB-4 score as predictors. Imputation was conducted using the mi impute logit command in Stata with a long data format.

The age-adjusted FIB-4 residual variable was generated by regressing FIB-4 on age alone and extracting the residuals, consistent with methodological recommendations for residualizing composite biomarkers. This variable was defined as a passive variable within the imputed datasets to ensure consistent adjustment across imputations. Sex and other covariates were not included in the residualization model because they were incorporated separately into the multivariable Cox models.

Finally, variables included in the multivariable models were selected based on clinical relevance and prior literature. Systolic blood pressure and fasting glucose were incorporated in the fully adjusted model as they represent independent cardiometabolic risk factors rather than intermediates on the causal pathway between hepatic fibrosis and mortality.

Results

Of the 134,686 participants with MASLD, 92.5% had a low FIB-4 index (< 1.30) and 7.5% had an intermediate or high index (≥ 1.30). Participants with higher FIB-4 levels were significantly older (mean age: 56.0 vs. 40.8 years; standard deviation [SD], 5.8; P < 0.001), and more likely to be married and engage in regular physical activity, but less likely to be male, obese, or current smokers. They also had higher systolic blood pressures and fasting glucose levels. All baseline characteristics differed significantly between the two FIB-4 categories (P < 0.001 for all comparisons), as summarized in Table 1.

During a mean follow-up of 11.2 years (SD, 5.8), 2,129 participants died from any cause and 348 died from cardiovascular disease. The age-adjusted FIB-4 residual variable was significantly associated with an increased risk for both outcomes. The hazard ratios (HRs) were 1.489 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.353–1.639) for all-cause mortality and 1.478 (95% CI, 1.175–1.860) for cardiovascular mortality (Table 2).

The results of the multivariate Cox regression analysis are shown in Table 3. In the basic model adjusted for sex (Model 1), age-adjusted FIB-4 was associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality, HR 1.642 (95% CI, 1.489–1.811), and cardiovascular mortality, HR 1.636 (95% CI, 1.300–2.057). These associations remained robust after adjusting for lifestyle and sociodemographic factors in Model 2, HR 1.568 (95% CI, 1.416–1.737) for all-cause mortality and HR 1.556 (95% CI, 1.230–1.968) for cardiovascular mortality, and were slightly attenuated but still significant in the fully adjusted Model 3, HR 1.489 (95% CI, 1.353–1.639) for all-cause mortality and HR 1.478 (95% CI, 1.175–1.860) for cardiovascular mortality.

In age-stratified analyses using Model 3, an association with all-cause mortality was observed in both age groups, with HR 1.881 (95% CI, 1.254–2.823) for participants aged ≤ 39 years and HR 1.445 (95% CI, 1.313–1.590) for those aged > 39 years. Regarding cardiovascular mortality, a significant association was only found in the older age group, HR 1.435 (95% CI, 1.145–1.798), whereas the estimate in the younger age group, HR 1.881 (95% CI, 0.617–5.739), was not statistically significant.

Discussion

In this large cohort of 134,686 individuals with MASLD, a higher FIB-4 index was associated with a 48.9% increase in all-cause mortality risk and a 47.8% increase in cardiovascular mortality risk. When stratified by age, the association with all-cause mortality was more pronounced in younger participants, with a hazard ratio of 1.881 in those aged < 39 years compared with 1.445 in those aged ≥ 39 years. These findings are consistent with those of previous studies that reported that advanced fibrosis is a strong predictor of all-cause mortality in patients with MASLD. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to specifically evaluate cardiovascular mortality using the FIB-4 index in an MASLD population. Furthermore, our findings highlight that elevated FIB-4 levels confer a greater relative mortality risk in younger individuals, underscoring the importance of early identification and risk stratification in this subgroup.

Participants were categorized into high and low FIB-4 groups according to the distribution of the age-adjusted residual variable, which represents the FIB-4 values after removing the effect of age. This approach minimized the confounding effect of age, an intrinsic component of the FIB-4 formula, allowing for a more accurate evaluation of its association with mortality. Missing covariate data were handled using multiple imputations by chained equations under the missing-at-random assumption, which enhanced the validity and robustness of our findings. Unlike most previous studies that directly used raw FIB-4 values without accounting for their inherent correlation with age or excluded participants with incomplete data, our methodology allowed for a less biased and more precise estimation of the relationship between the severity of liver fibrosis and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with MASLD.

The observed association between higher FIB-4 levels and increased mortality risk in MASLD may be explained by the close link between advanced hepatic fibrosis and systemic metabolic and vascular derangements. Progressive fibrosis is accompanied by chronic low-grade inflammation, increased oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction, and procoagulant activity, all of which contribute to the initiation and progression of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease21,22. Furthermore, fibrosis progression in MASLD often coexists with insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, which are key components of metabolic syndrome and synergistically amplify cardiovascular risk23. These interconnected mechanisms may explain the increased risk of cardiovascular mortality in patients with elevated FIB-4 levels.

In all-cause mortality, advanced fibrosis reflects a greater degree of hepatic architectural distortion and impaired synthetic function, predisposing patients to liver-related complications, such as hepatic decompensation, variceal bleeding, and hepatocellular carcinoma24. In addition, advanced fibrosis is often accompanied by sarcopenia, malnutrition, and increased susceptibility to infections, which contribute to excess non-liver-related mortality25,26.

The stronger relative association between elevated FIB-4 levels and all-cause mortality observed in younger individuals may reflect a more aggressive disease phenotype or the presence of additional, unmeasured risk factors in this subgroup. Previous studies have suggested that specific genetic variants, such as PNPLA3 and TM6SF2, may exacerbate disease severity in patients with advanced fibrosis, potentially accelerating liver injury progression in this subgroup27,28. In younger adults, elevated FIB-4 levels are less likely to be confounded by age-related comorbidities, such as chronic kidney disease or frailty, and therefore, may represent a more advanced stage of liver disease relative to peers of the same age. As younger individuals generally have a lower baseline risk of death, the proportional effect of advanced fibrosis on mortality is amplified. This finding underscores the need for targeted screening and intervention strategies to mitigate long-term adverse outcomes in younger patients with MASLD and elevated FIB-4 levels.

In contrast, the association with cardiovascular mortality was statistically significant only in older participants, likely reflecting the cumulative burden of traditional cardiometabolic risk factors (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, atherosclerosis), which act synergistically with hepatic fibrosis to increase cardiovascular risk29. In younger individuals, the relatively small number of cardiovascular deaths may have limited the statistical power to detect an association, even though the point estimate suggested a potential increased risk. Together, these findings suggest that while advanced hepatic fibrosis increases premature all-cause mortality in younger adults, its impact on cardiovascular mortality becomes more apparent later in life, when background cardiometabolic risks are more prevalent.

This study has several limitations. First, the severity of fibrosis was not confirmed using direct noninvasive modalities, such as transient elastography, magnetic resonance elastography, or liver biopsy. In addition, the FIB-4 index is an indirect marker of hepatic fibrosis and has limited diagnostic accuracy. Its sensitivity is lower in younger individuals, whereas in older adults, the score may be overestimated because of the age component in the formula. To mitigate this limitation, we generated an age-adjusted residual variable to remove the direct effect of age on FIB-4 values, thereby reducing potential age-related bias in risk estimation. Second, the classification of all-cause and cardiovascular mortalities was based on death certificates and diagnostic codes, which may have been misclassified. Third, information on lifestyle factors, such as alcohol consumption, smoking status, and physical activity, was obtained from self-reported questionnaires, which were subject to recall bias and misclassification. However, these data were collected in a standardized health-screening setting, and participants were unlikely to have a strong incentive to misrepresent their behavior, making differential bias less likely. Fourth, because individuals with viral hepatitis or excessive alcohol intake were excluded by design, subgroup analyses based on HBV/HCV status or alcohol consumption were not feasible. However, this restriction also strengthened the internal validity of our study by ensuring that the association between FIB-4 and mortality was evaluated in a population with metabolically driven steatotic liver disease rather than in individuals with liver injury from viral or alcohol-related causes. By limiting the cohort to MASLD-consistent etiologies, our findings more accurately reflect the clinical utility of FIB-4 in this specific population. Finally, as this cohort comprised Korean adults undergoing routine health checkups, the findings may not be fully generalizable to populations with different ethnic backgrounds, healthcare systems or environmental exposures.

Despite these limitations, this study has several strengths. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first large-scale investigation to evaluate cardiovascular mortality according to FIB-4 levels, specifically in a MASLD population, including detailed age-stratified analysis. We applied an age-adjusted residual approach to reduce the potential bias from the intrinsic age component of the FIB-4 formula and used multiple imputations for missing data, thereby enhancing the robustness of our findings. The large sample size of 134,686 participants and long follow-up period allowed for precise estimation of mortality risk. From a clinical perspective, our results underscore the utility of FIB-4, a simple and widely available index, in identifying patients with MASLD, particularly in younger individuals who are at an increased risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. These findings support the potential role of the FIB-4 index in routine risk stratification and prioritization of early preventive interventions in high-risk subgroups. In conclusion, the age-adjusted FIB-4 index was independently associated with increased all-cause and cardiovascular mortality risk in individuals with MASLD. Assessment of liver fibrosis using FIB-4 may provide prognostic information beyond traditional cardiometabolic risk factors in this population.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to restrictions from the Institutional Review Board but may be available from the Kangbuk Samsung Health Study upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Younossi, Z. M. et al. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology 64 (1), 73–84 (2016).

Estes, C., Razavi, H., Loomba, R., Younossi, Z. & Sanyal, A. J. Modeling the epidemic of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease demonstrates an exponential increase in burden of disease. Hepatology 67 (1), 123–133 (2018).

Younossi, Z. M., Kalligeros, M. & Henry, L. Epidemiology of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 31 (Suppl), S32–s50 (2025).

Koliaki, C., Dalamaga, M., Kakounis, K. & Liatis, S. Metabolically healthy obesity and metabolic Dysfunction-Associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD): navigating the controversies in disease development and progression. Curr. Obes. Rep. 14 (1), 46 (2025).

Byrne, C. D. & Targher, G. NAFLD: a multisystem disease. J. Hepatol. 62 (1 Suppl), S47–64 (2015).

Targher, G., Byrne, C. D. & Tilg, H. MASLD: a systemic metabolic disorder with cardiovascular and malignant complications. Gut 73 (4), 691–702 (2024).

Dulai, P. S. et al. Increased risk of mortality by fibrosis stage in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology 65 (5), 1557–1565 (2017).

Sterling, R. K. et al. Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Hepatology 43 (6), 1317–1325 (2006).

Cholankeril, G. et al. Longitudinal changes in fibrosis markers are associated with risk of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 78 (3), 493–500 (2023).

Vieira Barbosa, J. et al. Fibrosis-4 index can independently predict major adverse cardiovascular events in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 117 (3), 453–461 (2022).

Anstee, Q. M. et al. Prognostic utility of Fibrosis-4 index for risk of subsequent liver and cardiovascular events, and all-cause mortality in individuals with obesity and/or type 2 diabetes: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 36, 100780 (2024).

Graupera, I. et al. Low accuracy of FIB-4 and NAFLD fibrosis scores for screening for liver fibrosis in the population. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 20 (11), 2567–2576 (2022). e6.

Feng, Q., Izzi-Engbeaya, C. N., Manousou, P. & Woodward, M. Fibrosis status, extrahepatic Multimorbidity and all-cause mortality in 53,093 women and 74,377 men with metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) in UK biobank. BMC Gastroenterol. 25 (1), 546 (2025).

Chang, Y. et al. Metabolically healthy obesity and the development of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 111 (8), 1133–1140 (2016).

Paluch, A. E. et al. Daily steps and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis of 15 international cohorts. Lancet Public. Health. 7 (3), e219–e28 (2022).

Yang, H. et al. Physical frailty, genetic predisposition, and the risks of severe non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and cirrhosis: a cohort study. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 15 (4), 1491–1500 (2024).

Yoon, M. et al. Association of physical activity level with risk of dementia in a nationwide cohort in Korea. JAMA Netw. Open. 4 (12), e2138526 (2021).

Chang, Y., Ryu, S., Sung, E. & Jang, Y. Higher concentrations of Alanine aminotransferase within the reference interval predict nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin. Chem. 53 (4), 686–692 (2007).

Mathiesen, U. L. et al. Increased liver echogenicity at ultrasound examination reflects degree of steatosis but not of fibrosis in asymptomatic patients with mild/moderate abnormalities of liver transaminases. Dig. Liver Dis. 34 (7), 516–522 (2002).

Ryu, S. et al. Age at menarche and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 62 (5), 1164–1170 (2015).

Francque, S. M., van der Graaff, D. & Kwanten, W. J. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and cardiovascular risk: pathophysiological mechanisms and implications. J. Hepatol. 65 (2), 425–443 (2016).

Targher, G., Byrne, C. D. & Tilg, H. NAFLD and increased risk of cardiovascular disease: clinical associations, pathophysiological mechanisms and Pharmacological implications. Gut 69 (9), 1691–1705 (2020).

Zheng, H., Sechi, L. A., Navarese, E. P., Casu, G. & Vidili, G. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and cardiovascular risk: a comprehensive review. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 23 (1), 346 (2024).

Gan, C. et al. Liver diseases: epidemiology, causes, trends and predictions. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 10 (1), 33 (2025).

Chon, H. Y. & Lee, T. H. Liver cirrhosis and sarcopenia. Annals Clin. Nutr. Metabolism. 14 (1), 2–9 (2022).

Kusnik, A. et al. Clinical overview of Sarcopenia, Frailty, and malnutrition in patients with liver cirrhosis. Gastroenterol. Res. 17 (2), 53–63 (2024).

Romeo, S. et al. Genetic variation in PNPLA3 confers susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat. Genet. 40 (12), 1461–1465 (2008).

Liu, Y. L. et al. TM6SF2 rs58542926 influences hepatic fibrosis progression in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat. Commun. 5, 4309 (2014).

Guan, L., Li, L., Zou, Y., Zhong, J. & Qiu, L. Association between FIB-4, all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and cardiovascular disease risk among diabetic individuals: NHANES 1999–2008. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 10, 1172178 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted using data from the Kangbuk Samsung Health Study. We thank all study participants and the healthcare personnel involved for their dedication and continued support.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (RS-2023-00274176).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: W.L.; Methodology: Y.L. and W.L.; Formal analysis and investigation: Y.L. and W.L.; Writing – original draft: Y.L.; Writing – review and editing: Y.L. and W.L.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Kangbuk Samsung Hospital (IRB No: KBSMC2025-07-012).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, Y., Lee, W. Liver fibrosis index and mortality in metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease: a Korean cohort study. Sci Rep 16, 950 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30518-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30518-z