Abstract

Molecular analysis is mandatory in the diagnostic work-up of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs). Indeed, it is essential for clinical decisions, from patients’ selection for systemic treatment to identifying unrecognized syndromic conditions. Since GISTs are recognized as a heterogeneous family of different clinical entities, molecular analysis should also require a feasible, rapid, and reliable diagnostic workflow. Herein, we present our experience on the performance and clinical utility of two lab-developed multigene-NGS panels specifically built for GIST analysis. Among 163 analyzed GISTs, 72.4% carried KIT mutations while 11.0% were PDGFRA-mutant. Among putative KIT/PDGFRA WT cases that arrived at our attention from an external analysis, nine of 10 were found carrying either KIT or PDGFRA pathogenic mutations by our panel. On 26 KIT/PDGFRA/BRAF WT patients at the first level, the second level panel identified NF1 or SDHA mutations in 16 cases, while 10 patients did not display any mutation, except for two of them found as carriers of SDHC epimutation. This optimized NGS diagnostic approach helps to characterize the molecular profiles of GIST and drastically reduces the number of truly non-KIT and non-PDGFRA-addicted GIST cases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The inclusion of molecular analysis of KIT and PDGFRA in the diagnostic work-up of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) is considered standard clinical practice1. KIT and PDGFRA mutations have a proven pathogenetic role in GISTs and represent the main targets of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) currently used in clinical practice2,3. The clinical relevance of molecular analysis has grown over time, showing profound implications that clearly affect the overall survival of GIST patients4. Indeed, GISTs are recognized worldwide as a heterogeneous family of different clinical entities with well-settled molecular features. Besides KIT and PDGFRA mutations, affecting about 90% of all GISTs, over the years, other rarer but clinically significant molecular alterations have been found5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. Each molecular data has both predictive and prognostic values, essential for every clinical decision, from patients’ selection for systemic treatment to identifying unrecognized syndromic conditions16,17,18.

For this reason, in the past years, conventional Sanger sequencing and Real-Time PCR have been progressively replaced by multigene Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) technologies, capable of identifying both frequent events at a low variant allele frequency and other genetic alterations, such as those in SDHx, NF1, and BRAF mutations19. Anyway, to date a laboratory test (commercial or not) that includes the most relevant genes in the management of GISTs (KIT, PDGFRA, SDHx, NF1, BRAF, KRAS, FGFR1) is not available in routine clinical practice, which leads either to missing important genetic information in GIST diagnostics, or to rely on multiple assays or techniques to complete the molecular assessment of the tumor. Moreover, since some GIST-relevant genes are challenging due to either large dimensions or the presence of many similar pseudogenes (NF1, SDHx), they are frequently excluded from commercial NGS panels for oncology. Actually, even if commercial oncology NGS panels generally include KIT, PDGFRA, and BRAF full or hotspot sequencing, no commercial assay targets SDH subunits along with NF1 and FGFR1. Noteworthy, while KIT and PDGFRA and more recently BRAF mutations are notoriously targets of specific drugs currently used in clinical practice, the identification of SDHx and NF1 mutations holds clinically relevant value for prognostic outcome prediction and therapeutic decision making, besides essential information on the need for genetic counselling and surveillance for the patient and close relatives.

To date, molecular analysis is mandatory for clinical practice, but should also require a feasible, rapid, and reliable targeted multi-gene test and a standardized diagnostic workflow20.

This study aimed to develop and validate two laboratory-designed multigene NGS panels specifically optimized for GIST molecular assessment, addressing current limitations of commercial assays by improving coverage of challenging genomic regions and enabling comprehensive, clinically relevant mutation profiling in a single workflow.

Materials and methods

Patients

We included patients affected by GIST managed in different centers, expert or not in GIST, and arrived at our attention for molecular testing using lab-developed multi-gene panels. All pathological, clinical, and follow-up data were anonymously collected from in- and out-patient medical records in an electronic database. Confirmed written consent for molecular testing was obtained from all patients.

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki protocols. The study was reviewed and approved by the local Institutional Ethical Committee of Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria Policlinico S. Orsola-Malpighi, Bologna, Italy (approval number 113/2008/U/Tess), and informed consent was provided by all living patients.

Molecular analysis

All analyzed tumor samples were formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded (FFPE). DNA was extracted from two to three 10-um-thick sections, according to the selection performed by a pathologist on the last Hematoxylin and Eosin (H/E) slide. The DNA was then quantified using a Qubit fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Sequencing was performed using two multi-gene NGS panels developed in the Molecular Pathology Laboratory of Solid Tumors - IRCCS Policlinico di S.Orsola, allowing the analysis of the following genomic regions.

Panel 1 (“first-level” panel, 229 amplicons, 15.04 kb, human reference sequence hg19/GRCh37)11: BRAF (exons 11, 15), CTNNB1 (exon 3), EGFR (exons 12, 18, 19, 20, 21), EIF1AX (exons 1, 2), GNA11 (exons 4, 5), GNAQ (exons 4, 5), GNAS (exons 8, 9), H3F3A (exon 1), HRAS (exons 2, 3), IDH1 (exon 4), IDH2 (exon 4), KIT (exons 8, 9, 11, 13, 17), KRAS (exons 2, 3, 4), MED12 (exons 1, 2), MET (exons 2, 14), MYC (exons 1–3), NRAS (exons 2, 3, 4), PDGFRA (exons 12, 14, 18), PIK3CA (exons 10, 21), PTEN (exon 5), RET (exons 5, 8, 10, 11, 13, 15, 16), RNF43 (exons 2, 8), SMAD4 (exons 6, 9, 10, 11, 12), TERT (promoter region, g.1295141–g.1295471), and TP53 (exons 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9).

Panel 2 (“second-level” panel, 276 amplicons, 23.02 kb, human reference sequence hg19/GRCh37): SDHA (entire coding sequence - CDS), SDHB (CDS), SDHC (CDS), SDHD (CDS), NF1 (CDS), FGFR1 (CDS). According to previous validation21, only mutations present in at least 5% of the total number of reads analyzed and observed in both strands were considered for mutational calls. The Varsome (https://varsome.com/) and Franklin by Genoox (https://franklin.genoox.com/clinical-db/home) tools were used to evaluate the ACMG classification of each reported variant (last accessed 20th August 2024). Only Pathogenic/Likely Pathogenic and VUS (Variant of Uncertain Significance) variants were reported.

Statistical analysis

Comparison between main clinic-pathological features (gender, age, primary tumor site) and molecular subgroups was performed with either Unpaired t-test or Pearson’s chi-square statistics, by using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows Version 19.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

A total of 163 GIST patients were included, of which 153 (93.9%) underwent molecular analysis upfront in our laboratory, while 10 (6.1%) were sent from other laboratories as initially suspected KIT/PDGFRA WT cases. Overall, 136 patients (83.4%) underwent lab-developed “first-level” panel only, whereas the remaining 27 (16.6%) underwent both “first-” and “second-level” panels. Tumor and patients’ characteristics are reported in Table 1.

Among 136 patients studied with the “first-” panel only, KIT mutations were found in 118 cases (72.4%), and PDGFRA mutations were detected in 18 cases (11.0%).

In particular, for KIT mutations: 85.6% in exon 11, 10.2% in exon 9, 3.9% in exon 13, 1.7% in exon 17, and 0.6% in the splicing site (Fig. 1).

A summary of the distribution and most frequent types of KIT variants is listed in Supplementary Table 1. In three cases, biallelic or triallelic KIT mutations were detected. The Variant Allele Frequency (VAF) for all detected mutations ranged from 5% to 99% (mean 45.1%) (Fig. 2).

All the detected mutations were pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants, except for two (exon 11: c.1730_1774 + 3dup; exon 9: p.Ser451Cys), classified as “variant of uncertain significance - VUS”. However, they were considered pathogenetic according to the type of mutation and patients’ clinical features.

For PDGFRA mutations: 83.3% in exon 18, 11.1% in exon 14, and 5.6% in exon 12 (Fig. 1). All mutations were pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants, with a VAF ranging from 6% to 80% (mean 34.7%) (Fig. 2). The distribution of PDGFRA variant types is listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Notably, 90% (9 out of 10) cases referred to as putative KIT/PDGFRA WT from an external analysis resulted in KIT or PDGFRA mutations already at the first-level panel performed for validation in our laboratory (Table 2).

Many of these previously undetected mutant cases were carriers of complex genetic events, including large rearrangements (mainly duplications) or deletions spanning the intron 10/exon 11 boundary (6 cases), while one harbored a low-allele-fraction mutation. For most of them, this finding led to a significant therapeutic change, especially in considering imatinib adjuvant therapy in high-risk cases, with a potential impact on overall prognosis. In the other case (1 out 10), a BRAF p.Val600Glu mutation was detected using the first-level panel. Conversely, no alterations were detected in the RAS (KRAS, HRAS, NRAS) genes. Overall, the first-level panel successfully identified mutations in 12 cases with low-allele-fraction variants (VAF < 20%; mean: 13%), which would likely have been missed by Sanger sequencing due to its lower detection limit. Moreover, in 13 cases, it also identified very large alterations such as duplications, deletions, or insertions larger than 30 nucleotides, confirming the sensitivity not only of the test but also of the mapping algorithm.

Among 26 patients who required both “first-” and “second-level” panels because they resulted KIT/PDGFRA/BRAF WT from the first-level panel, a further second-level panel analysis allowed us to identify other gene alterations in 16 patients. In particular, NF1 mutations were found in 9 cases (5.5% of the entire cohort) (Fig. 1), with a VAF ranging from 10% to 96% (mean = 54.7%) (Fig. 2). SDHA mutations were found in 7 cases (4.3% of the entire cohort), with a VAF ranging from 12% to 85% (mean 38.9%) (Fig. 2), thus confirming the high prevalence of subunit A mutation in SDH-deficient GIST. In two cases, harboring pathogenetic SDHA mutations, a TP53 co-mutation was detected.

In 10 patients (6.1% of the entire cohort), no gene alterations, either by first or second level panel analysis, were found. At a further deeper analysis of two cases with clinical features belonging to SDHx-deficient GIST, an expected SDHC promoter methylation was discovered (Fig. 1). Therefore, in only 8 patients (4.9% of the entire cohort), with morphological and immunohistochemical features consistent with the diagnosis of GIST, no gene alterations have been found (Fig. 1).

In order to evaluate the ability of the second-level panel to identify SDHx mutations, 21 known SDH-deficient cases already characterized by Sanger sequencing were analyzed for internal validation. By second-level analysis, SDHx mutations were found in all cases, thus confirming the high diagnostic sensitivity of the panel, especially for SDHA mutations that are more challenging to identify due to the presence of highly similar pseudogenes. The analysis identified multiple types of SDHx mutations, with a vast majority of missense and nonsense variants (22 and 10, respectively), but also frameshift ins/del and splice-site mutations (6 cases).

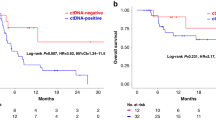

Looking at the entire cases included in the study, a correlation between clinical-pathological features and tumor genotype has been confirmed. In particular, a statistical difference in median age at diagnosis (p = 0.0001) and primary tumor site (p = 0.0001) was found, with SDH-deficient GISTs mostly affecting young-adult patients (mean age at diagnosis: 37 ± 3 years) with exclusive gastric localization (30/30) (Fig. 3A-B). Conversely, while KIT mutant cases showed an equal distribution in primary tumor site, NF1-mutant cases had an exclusive small intestine localization (9/9), and PDGFRA-mutant cases had gastric localization only (18/18) (Fig. 3B).

Discussion

Mutational analysis incorporation in the diagnostic work-up of all GISTs should be considered standard practice, due to its undoubted predictive value for disease classification, prediction of sensitivity to molecular-targeted therapies, as well as a prognostic relevance1. Thus, centralization of mutational analysis in a laboratory enrolled in an external quality assurance program and with high expertise in the disease may be relevant, especially for those cases without typical molecular alterations1. The lack of KIT and PDGFRA mutations, which once was enough to classify GISTs as WT, nowadays deserves to be interpreted in the specific patient clinical context and, if needed, questioned in case of genotype-phenotype clinical consistency19. Secondly, it then requires further analysis for the identification of other alterations, which are currently actionable or allow to identify those GISTs underlying unrecognized syndromes17,18.

In the present study, we reported the performance of two lab-developed multigene panels specifically built for GIST molecular analysis with a two-step approach to establish a standardized analytical workflow useful in clinical practice.

As expected, in 83.4% of cases first-level panel allowed the identification of pathogenetic alterations. Among patients undergoing second-level analysis, NF1 and SDHx mutations were found in more than half of the cases. Thus, excluding those two cases with SDHC methylation, in 93.9% of GISTs, at least one gene alteration by both panels has been found.

Noteworthy, all patients referred as KIT/PDGFRA WT from external analyses, which underwent the first-level panel for validation, were found to be mutated, including one case with a BRAF p.V600E mutation (Table 2). In this latter case (PAN_6, Table 2), the external institution had only performed KIT and PDGFRA analysis using Sanger sequencing, and for this reason, it had not been possible to identify the BRAF mutation. In 4 cases (PAN_36, PAN_69, PAN_102, PAN_103 - Table 2), the initial analysis was performed using Real-Time PCR, and it is known that the use of mutation-specific methods could lead to false negative results if the variants present in the sample are not included in the set of mutations identifiable by the kit in use. The other cases initially classified as WT (PAN_12, PAN_29, PAN_101, PAN_105, PAN_106 - Table 2) were analyzed in external institutions using NGS kits. However, these undetected mutant GIST cases included both very large rearrangements (duplications or deletions of more than 42 nucleotides) or intron 10/exon 11 spanning deletions or low-allele-fraction mutations. To ensure the accuracy of the results obtained using our lab-developed panel and to rule out possible false positives, the analysis was performed twice. Furthermore, the positivity of these cases was also confirmed by the clinical course of the patients. These results confirm previous reports on the most frequently missed KIT mutations in GISTs and support the need to refer patients with putative KIT/PDGFRA WT GIST to highly specialized molecular diagnostic centers that implement appropriate NGS panels and bioinformatic pipelines to detect even complex variants19. Indeed, the frequency of complex or large alterations and of low-allele-fraction mutations is high (18 cases carrying at least one of the two; 13.2% of all KIT/PDGFRA-mutant patients), thus further highlighting the need for centralization of GIST molecular diagnosis at least for WT cases, since these alterations would have probably been missed by routine molecular analyses.

The performance of the second-level panel in the detection of SDHx-mutations was validated on additional 21 SDHx-deficient GISTs, confirming the high diagnostic sensitivity of the panel (100% of mutations correctly identified), especially for the detection of SDHA mutations that are more challenging to identify due to the presence of highly similar pseudogenes. Actually, few SDHA mutations were classified as VUS, probably due to the still low frequency of these alterations and to the absence of hotspot mutation domains, which is the typical mutational profile expected for tumor suppressor genes. In these cases, coupling NGS panel sequencing with SDHB immunohistochemistry should help to identify SDH-deficient GISTs4,22,23,24. Moreover, clinical features should always guide the need for further molecular testing: in fact, we showed that two patients classified as WT from first and second-level panel analyses but showing typical features of SDH-deficient GISTs were confirmed as carriers of SDHC epimutations. Therefore, in agreement with data shown in the literature, the concordance between genotype and phenotype has been confirmed, highlighting once again the importance of clinical features to interpret unusual or unexpected molecular alterations or when typical alterations are not found6,7,10,11,12.

SDH-deficiency should always be investigated in younger patients, especially females, with gastric primary GIST and without conventional gene mutations. This is also valid when SDHx mutations with uncertain significance or when no SDHx mutations are found, recommending the implementation of immunohistochemistry (IHC) for SDH complex subunit B (SDHB) and subunit A (SDHA) in the diagnostic workflow25. Conversely, small intestine primary GISTs, generally multifocal, without KIT and PDGFRA mutations, should raise suspicion of an NF1-related GIST, even when the pathognomonic NF1 clinical features are lacking17. In these KIT/PDGFRA WT cases without a clear diagnosis of NF1 syndrome but just suspected for multifocality and site localization of GIST, the multigene first-level panel could be more useful. Conversely, for KIT/PDGFRA WT cases with clinical features of a genetic disease, the multigene second-level panel could help to characterize the NF1-related GIST and to make a diagnosis of neurofibromatosis genetic disease. The e of NF1-related GIST in our series was 9 out of 26 KIT/PDGFRA wild-type cases (5.5% of the entire cohort). The detection rate of NF1-related GIST in our series was higher than expected from previous reports6, even if a very recent NGS-based approach reached a similar high frequency (16/35)26. These discrepancies could reflect either the expected fluctuations due to the small numbers of a rare disease, the possible higher efficacy of our panel in detecting variants in a very challenging gene (NF1 is very large and with known similar pseudogenes), or lastly, the possibility that more difficult GIST molecular diagnoses were prevalently directed to our specialized center. Importantly, given the established associations of NF1 and SDHx variants with hereditary tumor syndromes, the identification of either SDH-deficient or NF1-related GISTs should always prompt genetic counseling to guide appropriate genetic testing, interpret variants of uncertain significance, and provide information for patient and family risk assessment and management.

Notably, in our series, only 4.9% of cases were truly negative (KIT/PDGFRA/BRAF/NF1/SDHx). In these cases, there is a need to widen and deepen the molecular analyses, since it is known that quadruple WT GIST may have very heterogeneous mutational profiles, with agnostic relevance in case of NTRK-fusion positive GISTs4,27,28. We therefore suggest that this very rare molecular condition should be profiled by a comprehensive sequencing assay, to uncover unexpected or rare conditions, that are usually not included in routine NGS panel analyses.

Sequential workflow of routine molecular assessment in GISTs Therefore. based on our clinical and molecular experience, the routine molecular assessment in GIST could follow a sequential workflow, that firstly explores KIT/PDGFRA mutations which are expected in more than 80% of GISTs, thus speeding up the molecular diagnostic assessment of the disease and lowering the economic burden, being able to analyze in the same run also other solid tumors that are covered by the same NGS panel., (Fig. 4).

Conversely, the second-level panel is restricted only to the lower number of cases that remain negative after the first-level analysis. In our hands, this approach is able to save time and money, even if a truly dedicated GIST panel can indeed be designed that merges the two gene lists.

In conclusion, in clinical practice, an additional double-check of the molecular analysis in high-volume reference centers is still crucial, even just for KIT and PDGFRA genes. This approach lowers the percentage of KIT/PDGFRA WT GIST from the previously known 10–15% to less than 5% and this result is extremely important in any context. Furthermore, in specialized centers, the expertise of the multidisciplinary team can benefit from the application of the suggested diagnostic workflow which combines a high-performance laboratory test with the experienced clinical assessment of patients, thus being able to classify GIST according to all known molecular subgroups (KIT/PDGFRA/BRAF/NF1/SDHx mutant). In practice, this optimized sequential approach helps to characterize the molecular profiles of GISTs and drastically reduces the number of truly oncogene-negative GIST cases which undoubtedly deserve further molecular screening within research programs.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Casali, P. G. et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: ESMO-EURACAN-GENTURIS clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 33, 20–33 (2022).

Maleddu, A., Pantaleo, M. A., Nannini, M. & Biasco, G. The role of mutational analysis of KIT and PDGFRA in Gastrointestinal stromal tumors in a clinical setting. J. Transl Med. 9, 75 (2011).

Cicala, C. M., Olivares-Rivas, I., Aguirre-Carrillo, J. A. & Serrano, C. KIT/PDGFRA inhibitors for the treatment of Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: getting to the gist of the problem. Expert Opin. Investig Drugs. 33, 159–170 (2024).

Call, J. et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor patients with molecular testing exhibit superior survival compared to patients without testing: results from the life raft group (LRG) registry. Cancer Invest. 41, 474–486 (2023).

Corless, C. L., Fletcher, J. A. & Heinrich, M. C. Biology of Gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 22, 3813–3825 (2004).

Boikos, S. A. et al. Molecular subtypes of KIT/PDGFRA Wild-Type Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A report from the National institutes of health Gastrointestinal stromal tumor clinic. JAMA Oncol. 2, 922–928 (2016).

Pantaleo, M. A. et al. SDHA loss-of-function mutations in KIT-PDGFRA wild-type Gastrointestinal stromal tumors identified by massively parallel sequencing. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 103, 983–987 (2011).

Nannini, M. et al. Integrated genomic study of quadruple-WT GIST (KIT/PDGFRA/SDH/RAS pathway wild-type GIST). BMC Cancer. 14, 685 (2014).

Lee, J. H. et al. Tropomyosin-Related kinase fusions in Gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Cancers (Basel). 14, 2659 (2022).

Miettinen, M. & Lasota, J. Succinate dehydrogenase deficient Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs)—A review. Int. J. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 53, 514–519 (2014).

Janeway, K. A. et al. Defects in Succinate Dehydrogenase in Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors Lacking KIT and PDGFRA Mutations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 108, 314–318 (2011).

Miettinen, M., Fetsch, J. F., Sobin, L. H. & Lasota, J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors in patients with neurofibromatosis 1: a clinicopathologic and molecular genetic study of 45 cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 30, 90–96 (2006).

Agaimy, A. et al. V600E BRAF mutations are alternative early molecular events in a subset of KIT/PDGFRA wild-type Gastrointestinal stromal tumours. J. Clin. Pathol. 62, 613–616 (2009).

Shi, E. et al. FGFR1 and NTRK3 actionable alterations in Wild-Type Gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J. Transl Med. 14, 339 (2016).

Pantaleo, M. A. et al. Genome-wide analysis identifies MEN1 and MAX mutations and a neuroendocrine-like molecular heterogeneity in quadruple WT GIST. Mol. Cancer Res. 15, 553–562 (2017).

Heinrich, M. C. et al. Kinase mutations and Imatinib response in patients with metastatic Gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J. Clin. Oncol. 41, 4829–4836 (2023).

Gasparotto, D. et al. Quadruple-Negative GIST is a Sentinel for unrecognized neurofibromatosis type 1 syndrome. Clin. Cancer Res. 23, 273–282 (2017).

Pantaleo, M. A. et al. SDHA germline variants in adult patients with SDHA-Mutant Gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Front. Oncol. 11, 778461 (2022).

Astolfi, A. et al. Undetected KIT and PDGFRA mutations: an under-recognised cause of Gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs) incorrectly classified as wild-type. Pathology 55, 136–139 (2023).

Denu, R. A. et al. Utility of clinical next generation sequencing tests in KIT/PDGFRA/SDH Wild-Type Gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Cancers (Basel). 16, 1707 (2024).

Kopanos, C. et al. VarSome: the human genomic variant search engine. Bioinformatics 35, 1978–1980 (2019).

Miettinen, M. et al. Immunohistochemical loss of succinate dehydrogenase subunit A (SDHA) in Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) signals SDHA germline mutation. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 37, 234–240 (2013).

Gill, A. J. Succinate dehydrogenase (SDH)-deficient neoplasia. Histopathology 72, 106–116 (2018).

Pantaleo, M. A. et al. Analysis of all subunits, SDHA, SDHB, SDHC, SDHD, of the succinate dehydrogenase complex in KIT/PDGFRA wild-type GIST. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 22, 32–39 (2014).

Florou, V. et al. A review of genomic testing and SDH- deficiency in Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: getting to the GIST. Cancer Med. 14, e70669 (2025).

Nishida, T. et al. Molecular and clinicopathological features of KIT/PDGFRA wild-type Gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Cancer Sci. 115, 894–904 (2024).

Urbini, M. et al. Gain of FGF4 is a frequent event in KIT/PDGFRA/SDH/RAS-P WT GIST. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 58, 636–642 (2019).

Demetri, G. D. et al. Diagnosis and management of Tropomyosin receptor kinase (TRK) fusion sarcomas: expert recommendations from the world sarcoma network. Ann. Oncol. 31, 1506–1517 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The NGS panel described in this study is the subject of a filed patent application (Patent Application No. PCT/IB2025/055494).

Funding

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Union – Next Generation EU through the Italian Ministry of University and Research under PNRR - M4C2-I1.3 Project PE_00000019 “HEAL ITALIA” to Maria A. Pantaleo (PI Spoke 8 University of Bologna) CUP J33C22002920006.

The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Commission. Neither the European Union nor the European Commission can be held responsible for them.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.N., A.As, M.A.P and D.d.B. provided study concept and design; M.G.P. and A.D.L. provided selection of cases; A.As., T.M., L.G., A.C., D.d.B provided analysis, and interpretation of data; M.N., A.As., M.C.N., L.G., A.C., D.d.B. drafted the manuscript; M.A.P. was involved in critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; M.A.P. obtained funding. All authors read and approved the final paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nannini, M., Astolfi, A., Maloberti, T. et al. Performance and clinical utility of two targeted multigene panels for GIST molecular characterization. Sci Rep 16, 855 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30548-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30548-7