Abstract

Ostertagia ostertagi is a highly prevalent nematode that affects grazing cattle and impacts performance and welfare by reducing appetite and hindering weight gain. Despite its economic significance, the influence of the abomasal parasite O. ostertagi on the rumen microbiome remains unexplored. We examined the effects of subclinical O. ostertagi infection and vaccination on the rumen microbiome at taxonomic and functional levels. In an experimental trial, calves treated with vaccine or adjuvant-only were orally challenged with O. ostertagi larvae daily for 25 days; 4 groups of animals (UNF: unvaccinated, unchallenged; VAC: vaccinated, challenged; CHE: unvaccinated, challenged, high cumulative faecal egg counts (cFEC), and CLE: unvaccinated, challenged, low cFEC) were selected for whole shotgun metagenomic sequencing. Using a rigorous permutation test based on partial least squares discriminant analyses, we identified 36 (91), 38 (31), 21 (57), 41 (64) and 29 (57) microbial genera (genes) that distinguished VAC, CHE and CLE from UNF, CHE from CLE, and CHE from VAC, respectively. The subclinical infection reshaped the rumen microbiome; enrichment of opportunistic pathogens such as Listeria, and depletion of Filifactor in infected animals were identified as potential biomarkers for host immune response, whereas Actinomyces and Microspora were potential biomarkers of resistance to infection. Microbial biochemical pathways like acetogenesis (e.g., Elusimicrobium, nrfA), pectin and hemicellulose degradation (e.g., Sphaerochaeta), and phosphorus and sulphur metabolism (e.g., Candidatus Accumulibacter and Desulfatibacillum) were also affected by parasitism. Both infection and vaccination altered methanogens, methanotrophs and the methane metabolism pathway, highlighted by distinct gene clustering patterns between infected and uninfected animals. Clustering patterns of infected and vaccinated animals exhibited some similarities, which may reflect immune system modulation of the ruminal microbiome as a result of an abomasal infection. This study unveils critical changes in the rumen microbiome due to the infection by and vaccination against the abomasal parasite O. ostertagi. Our results highlight the importance of monitoring microbial dynamics in the development of effective anthelmintic treatments and vaccines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ostertagia ostertagi is an abomasal parasitic nematode of cattle that negatively impacts the gastrointestinal function of the host. O. ostertagi’s life cycle consists of a free-living phase and a parasitic phase. The free-living phase starts when eggs develop in deposited faeces into first-stage larvae (L1), hatch and moult into second-stage larvae (L2), which develop and moult into infective third-stage larvae (L3). These larvae move onto the herbage, where they are ingested by the grazing animals, starting the parasitic phase of the life cycle1. The L3 larvae lose their protective sheath in the rumen, and pass into the abomasum, where they penetrate the gastric glands and develop into forth-stage larvae (L4) and subsequently to young adults (L5). The L5 leave the gastric glands and continue their maturation in the mucosal surface, and females will produce eggs in the gastrointestinal tract lumen2. Ostertagiasis has three clinically distinctive conditions. Type I disease affects young cattle and occurs when L5 larvae exit the gastric glands, causing damage. Clinical signs of type I ostertagiasis depend on infection level, ranging from reduced appetite and stunted growth to diarrhoea, rapid weight loss and even death. Pre-type II disease occurs when larval development is arrested after entering the gastric glands, and it is usually clinically mild or silent. Type II disease is most common in yearling (older) cattle and results from the resumed development of previously inhibited larvae, leading to clinical signs similar to type I disease1. Damage to the gastric glands caused by parasite development results in increased abomasal pH, which leads to hypergastrinaemia (i.e., increased blood gastrin levels)3,4,5 and hyperpepsinogenaemia (increased blood pepsinogen levels)6, which is a biomarker for nematode exposure in first-season calves7,8,9.

One of the most economically impactful and widely recognized effects of Ostertagia parasitism in cattle is the host’s inappetence1,3,4,10,11,12. For example, depressed voluntary feed intake in infected animals has been associated with a 73% weight gain reduction and a 74% digesta passage rate decrease. Infected calves with a moderate parasite burden may cost up to 30% more to rear to finishing or breeding compared to uninfected calves, due to impaired growth and increased management costs13. A negative correlation between O. ostertagi antibody levels in milk (a proxy for infection level) and milk yield has been reported in temperate climates14.

The gastrointestinal tract microbiota plays a key role in shaping the digestive efficiency across multiple species, including humans15, pigs16,17, chickens18, and cattle19. In beef cattle, the rumen microbiome has been associated with feed conversion efficiency and methane emissions20,21, appetite, and growth22. Given the close associations between the rumen microbiome and host performance traits, investigating the impact of parasitism by O. ostertagi on rumen microbiome profiles is of great interest and can have multiple applications, e.g., the identification of ruminal microbiome biomarkers to identify animals resistant to infection, in the development of probiotics to mitigate the impact of infection, development of vaccines, and even selection of the most resistant animals for breeding.

Nematode-parasitic infections have been suggested to lead to increased abundance of potentially pathogenic microorganisms in the gastrointestinal microbiome of the host. For example, Li et al. (2016) reported that although absent from the abomasal microbiome of uninfected goats, the pathogenic Pasteurellaceae family was significantly increased in goats challenged with Haemonchus contortus infectious larvae23; Lass et al. (2013) showed that co-infecting mice with the pathogen Bordetella bronchiseptica promoted the survival of the intestinal nematode Heligmosomoides polygyrus24.

Immunity to O. ostertagi develops only slowly, with cattle remaining susceptible even after long grazing periods. In developed production systems, this parasite is controlled through the application of anthelmintics, and vaccines are being developed. Vaccination against O. ostertagi is advantageous in comparison to the use of anthelmintics because it prevents development of potential anthelmintic-resistant parasites. Ideally, a vaccine should build up the animal’s immunity, by preventing or altering the establishment and consequent damage to the abomasum gastric glands, and therefore avert typical ostertagiasis clinical signs (e.g., inappetence), while not unfavourably impacting the rumen microbiome. Furthermore, since the microbiome deeply influences the host immune responses, and has been shown to affect vaccine immunogenicity and efficacy25, understanding the interplay between the rumen microbiome and the vaccine is crucial for the development of efficient vaccines.

Methods

The main objective of this study was to understand whether parasitism by O. ostertagi impacted the rumen microbiome composition and, if so, to characterize the main taxonomic and functional changes. At the taxonomic level, we focused particularly on potentially pathogenic microbes and those previously associated with methane production. At the functional level, we analysed microbial KEGG-annotated genes. Additionally, we investigated whether a protective native vaccine against O. ostertagi, based on thiol-binding proteins from excretory-secretory products (ESP) of adult parasites26 influenced rumen microbiome profiles. Beyond microbiome composition, we aimed to explore the host’s immune responses to parasitism and their associations with microbiome shifts, providing insights into the interplay between infection, immunity, and microbial dynamics. We also examined how resilience to O. ostertagi (assessed by cFEC) influenced these taxonomic and functional alterations, considering the broader context of rumen microbiome complexity, biological networks, and functions. All methods and procedures described herein are reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines27.

Animals and experimental procedure

An experimental trial was carried out to determine the effect of a native vaccine against O. ostertagi in dairy cattle (British Friesian and Norwegian Red at the Moredun Research Institute, Scotland, UK) based on thiol-binding proteins purified from adult O. ostertagi excretory-secretory products (ES-Thiol) as described in28. All calves were sourced by Moredun Bioservices from a commercial dairy farm in Lanark, Scotland, prior to being transported to Moredun animal accommodation. Animals were maintained at MRI in two penned areas of a covered farm building on straw bedding, fed twice daily on calf pellets with ad libitum access to fresh water. Conditions were managed to exclude accidental infection with helminth parasites from feed, by separating these from other animals and using disinfectant footbaths for personnel. Calves were confirmed helminth-naïve at the start of the experiment by conducting a faecal worm egg count29 and observing zero parasite eggs in all samples.

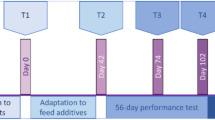

This experiment included 20 male calves of 4–5 months of age. Animals were allocated into 2 groups, balanced for breed (8 British Friesian and 2 Norwegian Red per group), age and weight, which were evenly distributed between the two pens. The first group (n = 10) received a native vaccine (30 µg ES-Thiol + 750 µg Quil A® adjuvant, Brenntag Biosector) whereas the second group (n = 10) received an adjuvant-only injection (750 µg Quil A®), administered intramuscularly on days 0, 21 and 42 of the experimental trial (Fig. 1). On day 42, both groups were subjected to an infection challenge consisting of oral administration of 1000 O. ostertagi L3 (isolate MOo2) per day, for 25 days (excluding weekends), spanning from days 42 to 76. From day 56 onwards, faeces samples were collected regularly to determine each animal’s cumulative faecal egg count (cFEC), an indicator of worm fitness used to assess vaccine efficacy against O. ostertagi30. The cFEC of each calf was calculated as the area under the FEC curve using the composite trapezoid rule31. Based on cFEC distribution within the adjuvant-only group, 4 animals with the highest (CHE) and 4 animals with the lowest (CLE) cFEC were selected for postmortem rumen digesta sampling. From the vaccinated group, 4 animals were selected from the second and third quantiles of the cFEC distribution (VAC) (Fig. 2). Additionally, 4 age- and weight-matched British Friesian calves that did not receive vaccine nor adjuvant and were not infection-challenged were included as uninfected negative controls (UNF). Thus, the 16 animals selected for rumen microbiome characterisation included: 4 VAC (3 British Friesian, 1 Norwegian Red, vaccinated and infection-challenged), 4 CHE (all British Friesian, adjuvant-only, infection-challenged resulting in high cFEC), 4 CLE (3 British Friesian, 1 Norwegian Red, adjuvant-only, infection-challenged resulting in low cFEC), and 4 UNF (all British Friesian, unvaccinated, not infection-challenged). All animals were housed under identical conditions. None of the 16 animals showed signs of clinical disease.

Relationship between cumulative faecal egg count (cFEC) and worm burden. (a) Scatter plot illustrating the distribution of cFEC (represented by pink triangles) and worm burden (represented by dark green diamonds) across different experimental groups (CHE, CLE, VAC and UNF refer to infected animals with high cFEC, low cFEC, vaccinated, and uninfected unvaccinated, respectively). Significance levels, determined through one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, are denoted by asterisks (*P < 0.01, **P < 0.001, ***P < 0.0001). Non-significant comparisons are not shown. (b) The linear regression model (represented by the dashed line) shows the association between worm burden and cFEC. The shaded area represents the 95% confidence interval around the regression line. The model yielded an R2 of 0.4 and a p-value of 0.004.

Measurement of parasite specific antibody responses

Parasite-specific IgA, IgG1, and IgG2 levels in blood serum samples collected from the animals during the experiment were quantified by ELISA (Fig. 1). High-binding 96-well microplates were coated with 50 µL/well of O. ostertagi L3 somatic antigen, diluted to 5 µg/mL in 0.5M carbonate buffer (pH 9.6). Plates were blocked with phosphate buffer solution (PBS) containing 3% fish gelatine for 1 h at 37 °C to minimize nonspecific binding. Serum samples were diluted 1:100 in containing 0.5% Tween-80 and 0.5M NaCl and applied in duplicate to the wells. After 1 h of incubation at 37 °C, plates were washed six times with PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20 using an ELx405 plate washer (Bio-Tek). Secondary antibodies were used to detect specific immunoglobulin isotypes. Mouse anti-bovine IgG1 monoclonal antibody (clone K37.2G6, 1:1600, Bio-Rad), mouse anti-bovine IgG2 monoclonal antibody (clone K192.4F10, 1:1600, Bio-Rad), and mouse anti-bovine IgA monoclonal antibody (clone K84 2F9, 1:1600, Bio-Rad) were applied, followed by a tertiary polyclonal rabbit anti-mouse Ig antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (P0260, Dako) at dilutions of 1:8000 for IgG1 and 1:1000 for IgG2 and IgA. Each incubation step lasted 1 h at 37 °C, with six washes between steps. Immunoreactivity was visualized using 100 µL of o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (OPD) substrate (SigmaFast OPD, P9187) at room temperature for 6 min. The reaction was stopped by adding 25 µL of 2.5 M sulfuric acid (H2SO4) per well. Optical density was measured at 492 nm (OD492) using a SpectraMax ABS Plus plate reader (Molecular Devices).

Identification of abundances of microbial organisms and microbial genes in rumen samples

Rumen digesta samples were collected from 16 animals within 10 min after slaughter. Sampling rumen digesta at slaughter results in well mixed samples. DNA was extracted from the samples following the methodology described in32.

Illumina TruSeq DNA Nano libraries were prepared from genomic DNA and sequenced on Illumina NovaSeq 6000 systems by Edinburgh Genomics (Edinburgh, UK). Paired-end reads (2 × 150 bp) were generated, resulting in between 8 and 50 gigabytes per sample (between 28 and 165 million paired reads). For taxonomic classification, the sequence reads of the samples were aligned to a database including genomes from the Hungate 1000 Collection33 and metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) from beef rumen samples34 using Kraken35. For functional annotation, DIAMOND was used to blast the reads for each sample against the KEGG database (downloaded 15/09/18)36. Gene abundance was calculated as the sum of reads mapping to each KEGG orthologue.

Statistical analyses

The normality of residuals from linear models regressing total worm burden and cFEC separately on treatment group was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test in R. Residuals for total worm burden did not deviate from normality, whereas those for cFEC did. Because the cFEC data contained zeros, we applied a log(x + 1) transformation. Group differences were then analysed using one-way ANOVAs, followed by Tukey’s post-hoc multiple comparison tests. Post-hoc power analyses were conducted for both worm burden and cFEC (effectsize37 and pwr38 packages in R (Version 1.3.959)), using 4 samples per group and significance level of 0.05. Three measures of average daily gain (ADG) were created per animal; ADG, ADGpre and ADGpost were generated based on linear regressions of body weight against test date using experimental trial days − 1 to 90, − 1 to 28 and 42 to 90, respectively. ADG, ADGpre and ADGpost were compared between groups using one-way ANOVAs. Live weights at weighting day (experimental trial days − 1, 7, 21, 28, 42, 49, 62, 69, 84, and 90) were also compared between groups using one-way ANOVAs.

Linear mixed-effects models were used to assess the effects of treatment and time (day) on immunoglobulins concentrations obtained from ELISA (IgA, IgG1 and IgG2). Since for the UNF group, we had only serology results for day 91, immunoglobulins concentrations were regressed on experimental group (CHE, CLE and VAC only), time (day) was used as covariate, and random intercepts were included to account for repeated measurements within individual animals, assumed to be normally distributed with mean 0 and variance \({\sigma }_{u}^{2}\), thereby modelling the correlation of repeated measures. These models were calculated using packages lme439 and lmerTest40 in R (Version 1.3.959). Post-hoc pairwise differences between treatment groups were compared using the emmeans41 package in R (Version 1.3.959). P-values were adjusted using the Bonferroni method. Then, a fixed-effects model was fitted to evaluate differences in immunoglobulins concentrations at day 91, in which the immunoglobulins were regressed on experimental group (UNF, CHE, CLE and VAC); when appropriate, TukeyHSD test was applied to explore pairwise differences.

A total of 3 domains, 45 phyla, 461 families, 1200 microbial genera and 8393 microbial genes (i.e., KEGG orthologues), were identified in the 16 rumen digesta samples. At the domain level, we compared the Archaea:Bacteria ratio between treatment groups to understand the impact of infection and vaccination on the overall balance of the microbial communities and potential impact on methane emissions42. Alpha diversity was assessed at the phylum, family, microbial genus, and microbial gene levels by the adjusted Shannon index based on maximum entropy (H’adj43) and beta diversity was assessed by calculating Bray–Curtis dissimilarity over samples of the same type (BC). Diversity measures were estimated using the vegan44 package in R (Version 1.3.959). We used ANOVA and PERMANOVA to compare H’adj and BC dissimilarity matrices, respectively, between the treatment groups. Additionally, non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) plots based on BC dissimilarity matrices were analysed for clustering patterns potentially associated with the treatment effect.

In each dataset (i.e., phylum, family, genus, and gene levels), variables were removed if they were absent from at least one sample, or if their relative abundance was lower than 0.001%, leaving 27 phyla, 288 families, 899 microbial genera and 3124 microbial genes for further analyses. Prior to further statistical analyses, the microbiome datasets were centred-log ratio (CLR) transformed, to account for their compositional nature45.

Partial Least Squared Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) models were applied to evaluate the suitability of the microbiome profiles at microbial phylum, family, genera, and genes level (using their CLR-transformed abundances) to discriminate CLE, CHE, and VAC from UNF. Additionally, the same PLS-DA strategy was applied to compare CHE and CLE, to evaluate the effects of animal resilience on the microbiome of infected non-vaccinated animals and CHE and VAC, to clarify the impact of vaccination on infection-challenged animals. A total of 40,320 PLS-DA models were calculated within each pairwise comparison using permuted labels to obtain the complete distribution of the variable importance in projection (VIP) scores. A p-value was calculated for each explanatory variable, based on the VIP distribution. The p-value < 0.05 was used as threshold to identify the microbiome features mostly contributing to the discriminations. These analyses were performed using the mixOmics package46 in R (Version 1.3.959). Microbial genes identified as discriminating between treatment groups were explored for their metabolic pathways in KEGG47,48,49. Pairwise comparisons of UNF with CHE, CLE, or VAC, of CHE with CLE and of CHE with VAC will be referred to as UNF-CHE, UNF-CLE, UNF-VAC, CHE-CLE and CHE-VAC throughout the manuscript.

To evaluate the association between immunoglobulins concentrations and microbes/microbial genes differentiating experimental groups, Pearson correlations were calculated between the concentration of immunoglobulins at day 91 and each microbial features identified as important in the PLS-DA analyses. The p-value < 0.05 threshold was used to identify significant correlations.

Co-abundance networks were created using the Graphia Pro software50, based on the CLR-transformed abundances of 3124 microbial genes derived from each experimental group, using a minimum correlation threshold of r = 0.98. Clustering was performed using the Markov clustering method available in Graphia Pro, using the granularity value of 2. Information pertaining to the biochemical pathways each microbial gene takes part in (according to KEGG database), and to whether the microbial gene was considered important for the UNF-CLE, UNF-CHE, and UNF-VAC discriminations was included in the network and used in enrichment analyses of the clusters (C).

Results

Cumulative faecal egg count and worm burden

We compared the groups based on cFEC and abomasal worm burden to assess their association with variations in microbiome profiles. The average ± standard deviation of cFEC for the treatment groups CHE, CLE, VAC and UNF were 452 ± 127, 175 ± 41, 141 ± 17 and 2 ± 2, respectively. Log-transformed cFEC values differed significantly (p < 0.05), with pairwise comparisons revealing that cFEC was significantly higher in CHE than both CLE and VAC, which did not differ from each other, and all three were higher than UNF. The abomasal total worm burdens (luminal and mucosal) were of 7663 ± 2525, 5650 ± 582, 7888 ± 1894, and 138 ± 243, respectively for CHE, CLE, VAC and UNF. As expected, CHE, CLE and VAC all had significantly (p < 0.05) higher worm burden than UNF animals (Fig. 2). Post hoc analyses indicated that the study had 100% power to detect differences in cFEC and 74% power for worm burden, suggesting that the significant differences observed are robust, while the lower power for worm burden should be accounted for when interpreting non-significant results.

The abomasal worm burden shows a significant moderate linear relationship with cFEC (R2 = 0.4, Fig. 2), mainly due to the different treatment groups. Interestingly, cFEC varied largely in CHE and VAC, but not in CLE; abomasal worm burden varied substantially in CHE but not in VAC or CLE. The high worm burdens observed in CHE, CLE and VAC animals in comparison to lower cFEC burdens are consistent with the mode of action of the vaccine, which reduces egg output but does not affect worm burdens51.

No significant differences between experimental groups were detected for ADG, ADGpre and ADGpost.

Microbiome diversity

Alpha and beta diversity indices showed no significant differences between treatment groups. However, post hoc analysis revealed low power (32 and 17% for genera and genes level adjusted Shannon indices), suggesting that the sample size may have been insufficient to detect small effects, and therefore, this lack of difference should be interpreted with caution. NMDS plots based on BC dissimilarity matrices showed no clustering pattern that could be associated to the treatment effect (Figs. S1 and S2), suggesting that neither infection or vaccination substantially affected the richness and/or distribution of microbes in the rumen nor the dissimilarities of microbiome structures between animals.

Comparing microbiome profiles between treatment groups

Rigorous permutation tests based on PLS-DA were used to identify differences between groups by maximising the separation of samples based on their microbiome compositions. Pairwise comparisons UNF-CHE, UNF-CLE and UNF-VAC in PLS-DA revealed some differences between microbiome profiles at different levels. At phylum level, Elusimicrobia was enriched in CHE, Fusobacteria and Cyanobacteria were enriched in CLE, and Euryarchaeota was depleted in VAC (Fig. S3).

A total of 16, 14 and 5 families were identified as differentially abundant in UNF-CHE, UNF-CLE, and UNF-VAC, respectively (Fig. 3). For example, Elusimicrobiaceae, a family that includes acetogenic starch users52, was 78% more abundant in CHE than in UNF, and Streptomycetaceae, one of the most important actinobacteria producing amylase in the rumen53, was 103% and 76% more abundant in CLE and VAC, respectively, than in UNF (Table S1).

Microbial families driving the differences between uninfected and infected or vaccinated animals. CHE, CLE, VAC and UNF refer to infected animals with high cumulative faecal egg count (cFEC), low cFEC, vaccinated, and uninfected unvaccinated, respectively. Observations were projected into the biplots based on centred log-ratio transformed abundances of 288 families, but only phyla with p-value < 0.05 of the variable importance in projection based on permutation tests of the partial least squares discriminant analyses are shown. Table cells coloured grey, blue, green, or orange represent microbial families enriched in UNF, CHE, CLE, or VAC respectively.

We identified 36, 38, and 21 microbial genera differently abundant between UNF and CHE, CLE, and VAC, respectively (Fig. 4). For example, acetate-producer Acetobacter, previously associated with increased pH54,55, and Aminobacter were 56% more abundant in CHE and CLE, respectively, than in UNF, whereas Pseudopropionibacterium, an opportunistic mammals pathogen56, had 49% higher abundance in VAC than in UNF (Table S2).

Microbial genera driving the differences between uninfected, infected, and vaccinated animals. CHE, CLE, VAC and UNF refer to infected animals with high cumulative faecal egg count (cFEC), low cFEC, vaccinated, and uninfected unvaccinated, respectively. Observations were projected into the biplots based on centred log-ratio transformed abundances of 899 genera, but only those with p-value < 0.05 of the variable importance in projection based on permutation tests of the partial least squares discriminant analyses are shown. Table cells coloured grey, blue, green, or orange represent microbial genera enriched in UNF, CHE, CLE, or VAC respectively.

Investigating the microbial genera important in both UNF-CHE and UNF-CLE discriminations revealed 2 microbial genera enriched (Methylocystis, a facultative methanotroph57, and Geodermatophilus), and 4 depleted (Syntrophomonas, Yersinia, Thermobacillus, Sphaerochaeta) in CHE and CLE in comparison to UNF (Fig. 5). Additionally, we compared microbial genera identified for the UNF-CHE and UNF-CLE discriminations with those identified for the UNF-VAC discrimination. However, most genera were uniquely identified as important for each discrimination, i.e., out of 18 microbial genera enriched in CHE in comparison to UNF, 16 were not identified as enriched in any other treatment groups.

Microbial genera important for discrimination of infected and vaccinated from uninfected, unvaccinated animals. CHE, CLE, VAC and UNF refer to high cumulative faecal egg count (cFEC), low cFEC, vaccinated, and uninfected unvaccinated animals, respectively. Left: microbial genera important for the discrimination of CHE, CLE, and VAC from UNF, highlighting genera shared among the comparisons. Centre: microbial genera important for the discrimination of CHE and CLE from UNF. Right: microbial genera important to discriminate infected (CHE + CLE = INF) and VAC from UNF. The arrows ↑ and ↓ refer to microbial genera enriched or depleted, respectively, in comparison to UNF.

The PLS-DA analyses revealed that 91, 31, and 57 microbial genes differed in UNF-CHE, UNF-CLE and UNF-VAC, respectively. For example, guaC, a housekeeping gene involved in purine interconversions, essential for recycling and managing nucleotides58, had 72% higher abundance in CHE, lnuA_C_D_E, a gene associated with antibiotic resistance59 had 95% higher abundance in CLE, and lysine-metabolism-involved argA had 31% higher abundance in VAC, in comparison to UNF (Fig. 6, Table S3).

Microbial genes driving the differences between uninfected and infected or vaccinated animals. CHE, CLE, VAC and UNF refer to infected animals with high cumulative faecal egg count (cFEC), low cFEC, vaccinated, and uninfected unvaccinated, respectively. Observations were projected into the biplots based on centred log-ratio transformed abundances of 3124 genes, but only those with p-value < 0.05 of the variable importance in projection extracted from permutations within partial least squares discriminant analysis are shown, except for 66, 7 and 15 microbial genes, which were omitted in UNF-CHE, UNF-CLE, and UNF-VAC for figure clarity. Table cells coloured grey, blue, green, or orange represent microbial genes (none omitted) enriched in UNF, CHE, CLE, or VAC respectively.

Most microbial genes identified for the UNF-CHE, UNF-CLE and/or UNF-VAC were uniquely identified (e.g., out of 91 microbial genes identified in the UNF-CHE comparison, only 17 were also important for other comparisons, Fig. 7). Some microbial genes were important for more than one comparison, for example, modE was depleted in CHE, CLE and VAC, in comparison to UNF (− 11%, − 17% and − 8%, respectively, Table S4).

Microbial genes important for discrimination of infected and vaccinated from uninfected, unvaccinated animals. CHE, CLE, VAC and UNF refer to high cumulative faecal egg count (cFEC), low cFEC, vaccinated, and uninfected unvaccinated animals, respectively. Left: microbial genes important for the discrimination of CHE, CLE, and VAC from UNF, highlighting genes shared among comparisons. Centre:microbial genes important for the discrimination of CHE and CLE from UNF. Right: microbial genes important for the discrimination of infected (CHE + CLE = INF) and VAC from UNF. The arrows ↑ and ↓ refer to microbial genes enriched or depleted, respectively, in comparison to UNF.

We investigated the metabolic pathways in which microbial genes enriched or depleted in infected or VAC animals were involved. Microbial genes enriched in infected animals were involved in biosynthesis of nucleotide sugars and polyketide sugar unit biosynthesis (e.g., evaA), amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism (e.g., GPI), bacterial secretion system and biofilm formation—Vibrio cholerae (e.g., gspD), lysine biosynthesis (e.g., murE), cationic antimicrobial peptide (CAMP) resistance and two-component system (e.g., dltB), monobactam biosynthesis (e.g., dapB), arginine and proline metabolism (e.g., pip), and lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis (e.g., lpxC).

Microbial genes depleted in infected animals were involved in selenocompound metabolism (e.g., metE), pyrimidine metabolism (e.g., psuK), and chloroalkane and chloroalkene degradation (e.g., nifD).

Microbial genes enriched in VAC animals were involved in pentose and glucuronate interconversions (e.g., rhaB), biosynthesis of amino acids (e.g., metB), and biosynthesis of cofactors (e.g., bioB), whereas genes depleted in VAC animals were involved in the nitrogen cycle pathway (e.g., nrfH).

The CLR-transformed abundances of 3124 microbial genes were investigated in a co-abundance network based on UNF records (Fig. 8), in which clusters were highlighted if microbial genes important (VIP ≥ 1) for the pairwise discriminations (UNF-CHE, UNF-CLE, UNF-VAC) were overrepresented. Additionally, clusters were analysed for overrepresentation of microbial genes according to the biochemical pathways to which they belong.

Co-abundance network of microbial genes in uninfected animals (UNF). Each node represents the CLR-transformed abundance of a microbial gene, and each edge represents a correlation between nodes of r = 0.98 or higher. Clusters with overrepresentation of microbial genes important (VIP ≥ 1) in the PLS-DA analyses for the pairwise discrimination of CHE, CLE, and VAC from UNF animals are labelled accordingly, and the increased or decreased abundance of microbial genes in each treatment group in comparison to UNF is indicated between the brackets by a ↑ or a ↓, respectively. Labels include information about overrepresentation regarding the biochemical pathways to which these microbial genes belong.

The critical value for Pearson correlation at 2 degrees of freedom is 0.98 for p < 0.02, which means that correlations equal of higher than our threshold of 0.98 have a 0.02 probability to occur by chance, indicating that the network is highly accurate.

The co-abundance network showed that microbial genes important for the UNF-CLE discrimination were overrepresented in clusters C12, C38, C39, C44, and C47. For example, microbial genes enriched in CLE and microbial genes associated with monobactam biosynthesis (Fig. 8) were overrepresented in C12. Microbial genes important for the UNF-CHE discrimination were overrepresented in C10, C11, C14, C15, C16, C18, C19, C27, C35, C36, C42, C49, C59, and C62. For instance, microbial genes enriched in CHE, and microbial genes associated with biofilm formation—Vibrio cholerae were overrepresented in C14. Microbial genes important for the UNF-VAC discrimination were overrepresented in C20, C43, C58, and C64, and for example, C64 had overrepresentation of microbial genes enriched in VAC, and of microbial genes associated with butanoate metabolism.

Microbiome profiles associated with resistance or susceptibility to infection

We compared microbiome profiles of CHE and CLE animals using PLS-DA to evaluate differences in microbial taxa (genus-level) and microbial genes (KEGG) related to resilience to infection. This analysis identified 41 microbial genera and 64 microbial genes differing between CHE and CLE (Fig. 9). For example, phosphorus-accumulating C. Accumulibacter and sulphur-reducing Desulfofarcimen were depleted in resistant animals (i.e., CLE). Actinomyces, Cellulomonas, a highly cellulolytic genus, and Micromonospora were enriched in resistant animals in relation to CHE. Also enriched in resistant animals were genes exoP (K16554), which showed positive correlations with IgA and IgG1, and E3.2.2.1 (K01239), positively correlated with IgG2.

Microbial genera and genes distinguishing parasite-resistant, parasite-susceptible, and vaccinated animals. CHE and CLE refer to infected animals with high and low cumulative faecal egg count, respectively, and VAC refers to animals that received vaccine prior to infection challenge. Observations were projected into the biplots based on centred log-ratio transformed abundances of 899 microbial genera and 3124 genes, but only those with p-value < 0.05 of variable importance in projection extracted from permutations within partial least squares discriminant analysis are shown, except for 28 and 21 microbial genes (CHE-CLE and CHE-VAC, respectively), which were omitted for clarity. Table cells coloured blue, green or orange represent microbial genera and genes enriched in CHE, CLE and VAC, respectively (none omitted).

Comparison of microbiome profiles of CHE and VAC identified 29 microbial genera and 57 microbial genes important for the discrimination, including e.g., Parabacteroides, C. Accumulibacter, and methanogen Candidatus Methanoplasma, enriched in CHE. In addition, Cyanobium, Pseudopropionibacterium, and Syntrophomonas were depleted in CHE in comparison to VAC. Microbial genes nrfA and nfrH, involved in nitrate cycle pathway, were enriched in CHE in comparison to VAC, and they both were negatively correlated with IgA and IgG1.

Serology and microbiome

Parasite-specific immunoglobulin concentrations were quantified by ELISA to evaluate antibody responses in serum from the different treatment groups (CHE, CLE and VAC). The ELISA assays measured optical density at 492 nm (OD492), which was used as an indicator of relative antibody concentration for each isotype (IgA, IgG1 and IgG2).

Linear mixed-effects models were then used to assess differences in longitudinal parasite-specific IgA, IgG1 and IgG2 between treatment groups (CHE, CLE and VAC), providing insight into immune system responses to infection60. These results showed that IgA concentrations did not differ between VAC, CHE and CLE groups. However, IgG1 levels were higher in VAC than in both CHE or CLE (p < 0.0001), and IgG2 was higher in VAC than in CHE (p = 0.0044). Over the experimental period, IgA concentrations remained stable, whereas IgG1 and IgG2 levels increased over time (+ 0.00184, p < 0.0001 and + 0.0019, p = 0.00000116, respectively). In addition, IgA levels did not differ among VAC, CHE and CLE groups, but IgG1 was higher in VAC than CHE or CLE (p < 0.0001), and IgG2 was higher in VAC than in CHE (p = 0.0044). Interestingly, IgG2 levels were consistently higher in the CLE than in CHE, although this difference was not significant (Table S4).

Serology data from samples collected on day 91 were available for all treatment groups, including UNF. Results from the linear model showed that CHE, CLE and UNF groups had significantly lower concentrations of IgA, IgG1 and IgG2 than the VAC group. Estimated differences between IgA levels of CHE, CLE, UNF and VAC were of 0.054 (p = 0.006), 0.060 (p = 0.003) and 0.068 (p = 0.001); for IgG1 they were 0.299 (p < 0.0001), 0.314 (p < 0.0001) and 0.366, (p < 0.0001); and for IgG2, they were 0.398 (p = 0.004), 0.281 (p = 0.038), and 0.399 (p = 0.004), respectively (Table S4).

To assess the synchrony between immune response and microbiome shifts in response to treatments, we estimated Pearson correlations between immunoglobulin concentrations on day 91 and abundances of microbial genera/genes (Table 1). Several significant correlations were identified, which should be interpreted as treatment effects and do not imply a causal relationship between microbiome and immunoglobulins concentrations. Microbes and microbial genes enriched or depleted in CHE in comparison to UNF mostly showed negative correlations with IgA and IgG1. Those enriched in CLE or VAC were mostly positively associated with IgG1 and IgG2, whereas microbes and genes depleted in CLE or VAC showed mostly negative correlations with all immunoglobulins.

Methane

The Archaea:Bacteria ratio, which offers an approximate insight into the microbial community structure, did not differ significantly between treatment groups (Fig. S4). We observed enrichment of a few methane-metabolising microorganisms in CHE and CLE, e.g., C. Methanoplasma and Methylocystis were enriched in CHE, Methyloversatilis was enriched in CLE and VAC, and Methanosphaera was depleted in CLE.

In uninfected animals, the co-abundance network analysis revealed that genes from the methane metabolism pathway (Fig. S5) were overrepresented in two major clusters (C44 and C58, with hxlB, comA, cofC, and aksE in C44, and mtrC and mcrD in C58). In C44, there was also overrepresentation of genes depleted in CLE in comparison to UNF, and in C58 there as also overrepresentation of genes depleted in VAC in comparison to UNF. When constructing comparable networks using gene abundances from CLE, CHE, and VAC animals (separately, i.e. one network per experimental group), these clusters were fragmented into multiple smaller clusters, indicating that the associations between microbial genes in the rumen microbiome changed due to the infection and vaccination (Fig. S6).

Discussion

Nematode parasitism poses a significant challenge to ruminant health, often manifesting in inappetence and weight loss. However, in our experiment, infected calves did not exhibit weight loss or decreased ADG, similarly to a previous study on lambs infected with the abomasal parasite Haemonchus contortus61. Moreover, in experiments comparing infected with uninfected pair-fed calves3, it was found that gastrointestinal function is compromised in parasitized animals, independent of inappetence and weight loss. Here, we investigated the impact of O. ostertagi on the rumen microbiome and identified 36, 38, and 21 microbial genera, along with 91, 31, and 57 microbial genes, as key discriminators of UNF-CHE, UNF-CLE and UNF-VAC, respectively. We also investigated differences in microbiome profiles relating to animals’ resistance to the parasite, by comparing CHE to CLE (since both groups were challenged with the same number of infected larvae but responded very differently in terms of egg development) and CHE to VAC (enabling the evaluation of vaccination effects).

Our results support that gastrointestinal dysfunction in infected animals extends beyond inappetence and suggest that alterations in the rumen microbiome are a major contributing factor. For example, Thermobacillus, Syntrophomonas, and Sphaerochaeta depletion was in line with the increasing level of infection (i.e., their abundances decreased in CLE and decreased further in CHE, in comparison to UNF). Thermobacillus is a hemicellulolytic bacterium that can also utilise xylan62. Syntrophomonas is a butyrate-degrading hydrogen-producing bacterium previously isolated from rumen fluid63, and its depletion in infected animals in comparison to both UNF and VAC could indicate that the butyrate available in the rumen environment of infected animals may not be sufficient to maintain Syntrophomonas’s normal levels of growth. Sphaerochaeta, a pectinolytic acetate producer, here depleted in CHE, CLE and VAC, was previously found depleted in the rumen of low efficiency in comparison to high efficiency dairy cattle64. In addition, Cellulomonas, an important cellulolytic genus, was enriched in CLE in relation to CHE. These results indicate a progressive disruption of fermentation potential along the infection gradient (from UNF, to CLE, and then to CHE), and suggest that microbiota changes impair fibre digestion.

Alongside Sphaerochaeta, other acetogens were found depleted (e.g., Lachnospira65,66,67) and enriched (e.g., Elusimicrobium and Acetobacter) in infected animals, suggesting that O. ostertagia parasitism alters acetogenesis, in line with previous reports of reduced acetate concentration in the rumen of nematode-infected animals68. Although Acetobacter is a facultative anaerobe 69, previous studies reported it had increased abundances in dairy cows with increased ruminal pH (in comparison to low pH associated with heat stress54 and laminitis55). Increased abomasal and ruminal pH has also been reported in parasitised animals, affecting microbial communities and microbial protein synthesis3,61,68,70.

Both Lachnospira and Sphaerochaeta are key rumen pectinolytic acetogenic microorganisms. Pectin degradation produces methanol, an important substrate for methane production by methylotrophs, and leads to microbial growth (often to greater extent than fermentation of starch)71, contributing to microbial protein synthesis, essential for animal growth and productivity72,73. The decreased abundance of pectinolytic organisms in infected animals observed in this study could be associated with previously reported decreased methane production (g/d) and impaired productivity of parasitised animals74,75. Acetate production decreases when hydrogen-using methanogens, e.g., Acetobacter, are reduced76. Reports of reduced methane production74, together with decreased acetate concentration68 are in agreement with our observation of shifts in methanogens and methanotrophs (described below), as well as changes in acetogenic communities.

Previous work showed decreased methane production (g/day) but increased total methane yield (g/kg dry matter intake) in nematode parasitised ruminants beyond what could be expected solely due to decreased feed intake and passage rates74,75. Additionally, 17 O. ostertagi peptides associated with methane metabolism have been predicted from transcriptomic data77. However, the functional consequences of these peptides on rumen methane production are unclear given that their expression was significantly enriched in free-living stages of O. ostertagi. We found no significant differences in the Archaea:Bacteria ratio, a crude proxy for methane production42,78. However, the abundances of some methanogens and C1 compounds users changed between treatment groups. For example, Tsukamurella, an actinobacterium previously reported as negatively associated with CH4 emissions in beef cattle79, as well as the methanogen C. Methanoplasma80 and the methanotroph Methylocystis81 were enriched in CHE and/or CLE. Methyloversatilis, which includes methylotrophs and methanotrophs82,83, was enriched in CLE and VAC in comparison to UNF.

Our network analysis revealed that the associations between microbial genes and methane metabolism pathway were different among experimental treatment groups. For example, genes in C44 from the UNF-based network were involved in biosynthesis of cofactors, including coenzyme B, M and F420 biosynthesis, required for Wolfe cycle in methanogenesis84. In contrast, although microbial genes in C2 and C3 of CHE-based and CLE-based networks, respectively, were similarly involved in coenzymes B, M and F420 biosynthesis, they were also involved in methanofuran biosynthesis, which is essential for activation and conversion of carbon dioxide into methane85, and in methanogenesis (including gene mcrA). This result highlights that the relationships between different microbial genes varied due to infection and vaccination in comparison to uninfected animals.

Analysis of the UNF-based co-abundance network highlighted that genes in the methane metabolism pathway were overrepresented in C44 and C58, with genes depleted in CLE being overrepresented in C44, and those depleted in VAC being overrepresented in C58. Comparing the UNF-based network with CHE-, CLE- and VAC-based networks revealed that UNF-based C44 and C58 were fragmented into multiple smaller clusters in the other networks, suggesting that associations between microbial genes (and therefore, between microbial functional potentials) was altered by the different treatments. Interestingly, the association between microbial genes from the methane metabolism pathway, genes depleted in CLE and genes depleted in VAC was maintained despite the treatment groups: UNF-based C44 and C58, CHE-based C2, CLE-based C3 and C29, and VAC-based C2 and C42 all had overrepresentation of the three groups of genes. This result suggests that there is a consistent relationship between microbial genes depleted due to low levels of infection and/or increased resistance (via either vaccine or natural variation of immune system responses) and genes in the methane metabolism pathway. Previous works by Houdijk et al. (2017) and Fox et al. (2018) reported reduced methane production (g/h) in sheep and lambs, respectively, infected by Teladorsagia circumcincta in comparison to uninfected controls74,75. Our results are in line with these observations, i.e., infected animals producing less methane; however, the strong association we observed here pertains to the most resistant animals, and not to all infected animals. Furthermore, the clustering of genes depleted in VAC, genes depleted in CLE, and genes in the methane metabolism pathway suggests that infected and vaccinated animals may both have reduced methane production, in comparison to uninfected animals. The response is likely due to an effect of the immune response on the rumen microbiome, rather than a direct consequence of the presence of the nematode. This interpretation is supported by the observation that methane metabolism genes clustered together with genes depleted in CLE, but not with those depleted in CHE. Overall, some microbial genera and genes known to be associated with methane production were altered in infected in comparison to uninfected animals. However, we cannot, based on our analyses, conclude about the impact of these alterations on the magnitude of methane production of the host animals.

The rumen microbiome is highly anaerobic with traces of oxygen. However, we have identified some aerobic and facultative anaerobic organisms in the rumen. Auricularia, an aerobic fungi with a global distribution that grows on wood86, and Paludisphaera, an aerobic bacterium that inhabits a variety of terrestrial environments87, were enriched in CHE and VAC, whereas the facultative anaerobe Acetobacter was enriched in CHE. Whilst it is possible that Acetobacter uses oxygen naturally introduced in the rumen during feeding, drinking and rumination, thereby contributing to the maintenance of the anaerobic environment54, these results could be suggesting some dysregulation over oxygen entering the rumen during infection, leading to dysbiosis.

Although our animals were infected at subclinical levels, some alterations in the rumen microbiota indicate that the ruminal pH may have been affected, and that this, together with alterations in microbial communities’ structure, may have affected methane production patterns74. In the present work, Trichosporon was depleted in CHE, in agreement with a previous work on goats reporting its negative correlation with pH88. Changes in ruminal pH affect nitrogen digestibility and protein metabolism, due to decreased protein digestibility and/or increased nitrogen losses in urine, with lambs fed diets sufficient in protein and trace elements showing higher resilience to parasites61, as well as improved ability to produce parasite-specific IgA89. In our study, some microbial genes involved in biosynthesis of amino acids (e.g., argA, cysM), nitrogen metabolism (e.g., GDH2) and lysine biosynthesis (e.g., dapA, dapB, murE) were enriched in infected animals in comparison with uninfected, and some genes in the nitrogen metabolism were also enriched in CHE in comparison with vaccinated animals (e.g., nrfA and nrfH). The microbial gene dapB, enriched in CHE and negatively correlated with IgG1 concentration, is involved in the production of diaminopimelate, which can act as an intermediate either for lysine or for peptidoglycan production90. Furthermore, in the UNF-based network (Fig. 8), genes involved in amino acids biosynthesis clustered together with genes depleted in CHE (C16 and C35) as well as with genes enriched in CHE (C62). The clustering patterns changed when the network was based on CHE data, reflecting changes in the microbial metabolic pathways in the rumen of infected animals. Ruminal pH is an important modulator of enteric methane production. For example, cows with reticulorumen pH of 6.22–6.42 had 46% higher methane emissions than cows with pH < 6.2291. In a study on the beef cattle microbiome, Martínez-Álvaro et al. (2020) reported that Candidatus Methanomethylophilus clustered together (in a correlation-based network) with other acetogens and was negatively associated with methane emissions21,92. Based on this, methane emissions are expected to be reduced in infected animals in the present study, in which we observed increased abundances of C. Methanomethylophilus (methylotroph archaea) and Acetobacter (acetate producer associated with increased ruminal pH) in CHE in comparison to UNF.

Previous studies reported depleted abundances of Filifactor93 and increased levels of IgA94 in the faecal microbiome of human patients with inflammatory Behcet’s disease, suggesting that Filifactor may be a biomarker for inflammatory response. In agreement, Filifactor was depleted in the rumen of CHE and had a negative correlation of -0.13 with IgA, although not significant. Our serology results also showed that the concentration of IgA increased as UNF < CLE < CHE < VAC. Although the difference of IgA between UNF and CHE was not significant (potentially due to low sample size), increased serum IgA levels have been previously reported in grazing cattle infected with O. ostertagi60. In addition, the cFEC and the worm burden in CHE varied largely, compared to other groups. These results suggest that some CHE animals may have mounted an immune response, and that IgA may have played a protective role, limiting the progression to clinical disease, despite the high parasite burden.

Sulphate-reducing bacteria (SRB) were more abundant in CHE animals. For example, Desulfatibacillum was more abundant in the rumen of CHE in comparison to UNF animals, whereas Desulfofarcimen95 was more abundant in CHE than in CLE. SRBs can use hydrogen to produce hydrogen sulphide (H2S)96,97 potentially competing with methanogens for hydrogen like observed in the rumen of infected animals74,75. However, H2S production and fate in the rumen is highly under ruminal pH control98. For example, animals associated with lower ruminal pH were more resilient regarding H2S ruminal concentration and exhibited no significant changes in performance e.g., dry matter intake, ADG99. Therefore, increased Desulfatibacillum abundance and the associated rise in H2S production could contribute to clinical signs such as inappetence and weight loss in infected animals. However, in the present study, H2S was most likely not sufficiently elevated to cause such effects. Desulfatibacillum may be a suitable candidate for biomarker of parasite infection independent of feed intake levels, whereas Desulfofarcimen may help identify animals that are more vulnerable to infection.

Some microbes were enriched in CHE in comparison to UNF, but not in CLE; for example, Dietzia and Actinoalloteichus have previously been identified as a cause of mastitis in dairy cattle100,101. However, some species are suitable probiotics in inflammatory bowel disease, especially Crohn’s disease in human patients, and have been shown to have inhibitory effect on the growth of Mycobacterium avium, the etiological agent of Johne disease in cattle102,103. Micromonospora, enriched in CLE in comparison to UNF and CHE, can produce the antibiotic G-148, which has broad-spectrum activity against helminths104. CHE and CLE groups were orally administered the same amount of L3 infectious larvae during the infectious challenge, but this resulted in CHE having a significantly higher cFEC, as well as a more variant cFEC than CLE. Regarding worm burdens, CHE and CLE were not significantly different, mostly because although two CHE animals had higher worm burden, two others had worm burden similar to CLE. In addition, although non significantly, the concentration of IgG2 in CLE was higher than in CHE in all timepoints throughout the experiment, highlighting the improved resistance of CLE, which could stem from variation in immune response (through IgG2) as well as in the rumen microbiome profiles.

Gordonia was previously identified in the microbiota of the insect-infectious entomopathogenic nematode Rhabditis regina (dauer stage)105, and was here enriched in CLE. Entomopathogenic nematodes differ from others because their microbiota is the main factor promoting the death of the host. It is possible that Gordonia was found here because it was part of Ostertagia’s microbiota.

Cronobacter, depleted in CHE in comparison to UNF, and Aerococcus, depleted in CHE in comparison to UNF, VAC and CLE are opportunistic pathogens106,107. Enterococcus is an opportunistic pathogen depleted in CLE, and Yersinia, a known mammal pathogen, was depleted in CHE and CLE, and was negatively correlated with IgA. The lower abundance of these opportunistic pathogens in the rumen of infected animals may be attributed to various factors; (i) the presence of the nematode in the infected animals may have triggered an immune response, which may have led to changes in the rumen environment, (ii) microbes that thrive in the rumen of Ostertagia-infected animals may outcompete these pathogens, (iii) these opportunistic pathogens may be more sensitive to the changes brought on by the nematode (e.g., ruminal pH), or even to the stress the infected host is under. Microbial genes associated with biofilm formation were enriched in infected animals (e.g., gspD in CHE, rpoS in CLE). Microorganisms are able to organise themselves into biofilms, producing polymers that facilitate attachment and matrix formation, and changing the phenotypes of the biofilm-associated microorganisms, towards decreased antimicrobial susceptibility108. Therefore, we can hypothesize that, in the presence of this parasite, the biofilm development works as a defence mechanism.

Xenorhabdus is depleted in CLE in comparison to UNF. This bacterium establishes mutualistic symbiosis with juvenile infectious entomopathogenic nematodes109, having been identified as the one of the main reasons for the insecticide action of these nematodes. However, it also produces antibiotics to avoid other microbes from colonizing and growing in nematode-killed insects. Xenorhabdus has not previously been reported as part of the healthy rumen microbiota. However, its detection in the present study—at a minimum relative abundance of 0.001% in the rumen fluid of at least 16 steers—supports that its presence is a true biological observation. Therefore, this bacterium might play a role associated with the defence of the rumen microbiota communities from external microbes that could otherwise get established and lead to dysbiosis. The enrichment of microbial genes associated with cationic antimicrobial peptide (cAMP) resistance in infected animals (e.g., dltB in CHE), together with the depletion of an antimicrobial producing bacterium Xenorhabdus may be an indication of rumen dysbiosis.

The mastitis-associated Dietzia, the opportunistic pathogen of mammals Pseudopropionibacterium56 and the methylotroph Methyloversatilis were all enriched in CLE and VAC, whereas Auricularia and Paludisphaera were enriched in both CHE and VAC in comparison to UNF. These similarities between CLE and VAC may be expected as both groups were subjected to the same infection challenge and showed similar increased cFEC in comparison to UNF, but substantially lower than in CHE. This can be attributed to an improved immune response in CLE (through more resistant animals) and in VAC (through the improvement of the immune response due to the vaccine). Pseudopropionibacterium was also enriched in CLE and VAC in comparison to CHE and significantly positively associated with IgG2, highlighting its potential as biomarker for resistance. However, the microbial differences we observed between CHE and VAC animals indicate that vaccination does not replicate the microbiome changes associated with natural resistance; instead, vaccinated animals show a distinct microbial signature consistent with reduced egg output but unchanged adult worm establishment, as expected from a vaccine that targets egg production rather than worm burden. In comparison with VAC, CHE animals were enriched with Parabacteroides, previously reported as enriched in the gut of lambs infected with Teladorsagia circuncincta110, and methanogen C. Methanoplasma. In addition, nitrate-cycle genes nrfA and nrfH were enriched in CHE but negatively correlated with IgA and IgG1, suggesting that their abundance may be associated with weaker host immune responses. C. Accumulibacter was enriched in CHE in comparison to all other groups, indicating it could be a biomarker for high levels of cFEC independent of vaccination status.

These findings suggest that the infection with O. ostertagi affects not only the abomasum (the specific site of infection), but also the rumen microbiome, likely through systemic immune responses. This highlights the value of rumen digesta as a source of microbial biomarkers for infection status and resilience, with potential applications in microbiome-driven breeding strategies111 aimed at improving herd-level resilience. By identifying microbial genera consistently altered in vaccinated and infected animals, our study provides a basis for developing targeted microbial interventions, such as probiotics or microbiome-guided nutritional strategies, to support animals during the period when immunity is developing (i.e., the first year of life), whether through vaccination or natural exposure. Such interventions could mitigate negative impacts of both infection and vaccination on animal performance, helping to maintain feed efficiency and reduce production losses. These microbial signatures also open opportunities to identify consortia that enhance vaccine efficacy, accelerate the development of protective immunity in young cattle, or counteract the adverse effects of infection on digestion and methane emissions. Ultimately, translating these microbial indicators into practical tools would improve animal resilience, reduce reliance on anthelmintics, and support more sustainable and profitable ruminant production systems.

A key limitation of this study is the relatively small sample size, which may reduce the statistical power to detect subtle associations and limit the generalisation of the findings. Differences between treatment groups reported here provide valuable insights into the relationship between the rumen microbiome and host responses to Ostertagia infection and vaccination, however, more subtle differences in microbiome profiles may have been missed. Despite this limitation, the study provides a foundation for understanding the impact of an abomasal parasite infection on the rumen microbiome.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrates that Ostertagia ostertagi parasitism alters the rumen microbiome, with potential downstream impacts on key physiological processes such as nitrogen, pectin and hemicellulose metabolism, and methane production. Changes in microbial communities and functional capacities reflect a complex interplay between parasitism and the host’s immune response. Potential new microbial biomarkers related to pH alterations (Acetobacter), methane metabolism (Methyloversatilis), sulphate metabolism (Desulfatibacillum), and phosphorus utilisation (C. Accumulibacter) in infected animals were identified. The depletion of pectinolytic organisms such as Lachnospira and Sphaerochaeta highlights how infection disrupts normal fermentation processes, with consequences for methane metabolism and feed conversion efficiency. Furthermore, the enrichment of biofilm-associated genes and antibiotic-producing microbes like Micromonospora in the resistant CLE group, suggests that the microbiome may play a protective role, enhancing resistance to infection and supporting immune function. This study reveals that the effect of parasitism on the rumen microbiome extends beyond changes in feed intake and gastrointestinal function. The differential clustering of methane metabolism genes between infected and uninfected animals, as well as similarities between infected with low cFEC and vaccinated animals suggests that parasitism and immune response both influence methane metabolism, potentially contributing to the previously observed reductions in methane production in infected animals. This highlights the need for further investigation into the associations between parasitism, immune responses and microbiome function, particularly in the context of methane mitigation and performance improvement. Overall, our findings underscore the importance of understanding intricate relationships between host and microbiome in the context of parasite infections, which could inform strategies for improving animal health, productivity and sustainability of animal production systems.

Data availability

Data generated or analysed during this study are available in the European Nucleotide Archive ([ENA Browser] (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/browser/home)) under project accession number PRJEB92076.

Abbreviations

- ADG:

-

Average daily weight gain calculated based on experimental trial days − 1 to 90

- ADGpre:

-

Average daily weight gain calculated based on experimental trial days − 1 to 28

- ADGpost:

-

Average daily weight gain calculated based on experimental trial days 42 to 90

- BC:

-

Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index

- C:

-

Clusters

- CAMP:

-

Cationic antimicrobial peptide

- cFEC:

-

Cumulative faecal egg counts

- CHE:

-

Unvaccinated, challenged animals that had high cFEC at the end of the trial

- CLE:

-

Unvaccinated, challenged animals that had low cFEC at the end of the trial

- CLR:

-

Centred-Log ratio

- DNA:

-

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- ESP:

-

Excretory-secretory products

- H’adj:

-

Adjusted Shannon index

- IgA:

-

Immunoglobulin A

- IgG1:

-

Immunoglobulin G1

- IgG2:

-

Immunoglobulin G2

- MRI:

-

Moredun Research Institute

- NMDS:

-

Non-metric multidimensional scaling

- OPD:

-

O-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride

- OD:

-

Optical density

- PBS:

-

Phosphate buffer solution

- PLS-DA:

-

Partial last squares-discriminant analysis

- SRB:

-

Sulphate-reducing bacteria

- UNF:

-

Unvaccinated, unchallenged animals

- VAC:

-

Vaccinated, challenged animals

- VIP:

-

Variable importance in projection

References

Myers, G. H. & Taylor, R. F. Ostertagiasis in cattle. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 1, 195–200 (1989).

Saverwyns, H. Study of Ostertagia ostertagi excretory-secretory products. Univertiteit Gent (2008).

Fox, M. T. et al. Ostertagia ostertagi infection in the calf: Effects of a trickle challenge on appetite, digestibility, rate of passage of digesta and liveweight gain. Res. Vet. Sci. 47(3), 294–298 (1989).

Fox, M. T., Uche, U. E., Vaillant, C., Ganabadi, S. & Calam, J. Effects of Ostertagia ostertagi and omeprazole treatment on feed intake and gastrin-related responses in the calf. Vet. Parasitol. 105(4), 285–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-4017(02)00026-2 (2002).

Farningham, D. A., Mercer, J. G. & Lawrence, C. B. Satiety signals in sheep: Involvement of CCK, propionate, and vagal CCK binding sites. Physiol. Behav. 54(3), 437–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-9384(93)90232-5 (1993).

Fox, M. T., Gerrelli, D., Shivalkar, P. & Jacobs, D. E. Effect of omeprazole treatment on feed intake and blood gastrin and pepsinogen levels in the calf. Res. Vet. Sci. 46(2), 280–282 (1989).

Charlier, J. et al. Serum pepsinogen levels to monitor gastrointestinal nematode infections in cattle revisited. Res. Vet. Sci. 90(3), 451–456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rvsc.2010.06.029 (2011).

Berghen, P., Hilderson, H., Vercruysse, J. & Dorny, P. Evaluation of pepsinogen, gastrin and antibody response in diagnosing ostertagiasis. Vet. Parasitol. 46(1–4), 175–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4017(93)90057-t (1993).

Kenyon, F. & Jackson, F. Targeted flock/herd and individual ruminant treatment approaches. Vet. Parasitol. 186(1–2), 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.11.041 (2012).

Fox, M. T. et al. Endocrine effects of a single infection with Ostertagia ostertagi in the calf. Int. J. Parasitol. 17(6), 1181–1185. https://doi.org/10.1016/0020-7519(87)90170-6 (1987).

Fox, M. T. Pathophysiology of infection with Ostertagia ostertagi in cattle. Vet. Parasitol. 46(1–4), 143–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4017(93)90055-r (1993).

Hawkins, J. A. Economic benefits of parasite control in cattle. Vet. Parasitol. 46(1), 159–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4017(93)90056-S (1993).

‘Plan now for effective parasite control in cattle | Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs’. Accessed: Apr. 28, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.daera-ni.gov.uk/news/plan-now-effective-parasite-control-cattle

Almería, S., Adelantado, C., Charlier, J., Claerebout, E. & Bach, A. Ostertagia ostertagi antibodies in milk samples: Relationships with herd management and milk production parameters in two Mediterranean production systems of Spain. Res. Vet. Sci. 87(3), 416–420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rvsc.2009.05.001 (2009).

Cani, P. D. & Knauf, C. How gut microbes talk to organs: The role of endocrine and nervous routes. Mol. Metab. 5(9), 743–752. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2016.05.011 (2016).

Nowland, T. L., Plush, K. J., Barton, M. & Kirkwood, R. N. Development and function of the intestinal microbiome and potential implications for pig production. Anim. Open Access J. MDPI 9(3), 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9030076 (2019).

Camarinha-Silva, A. et al. Host genome influence on gut microbial composition and microbial prediction of complex traits in pigs. Genetics 206(3), 1637–1644. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.117.200782 (2017).

Diaz-Sanchez, S. et al. Using fecal microbiota as biomarkers for predictions of performance in the selective breeding process of pedigree broiler breeders. PLoS ONE https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216080 (2023).

Shabat, S. K. B. et al. Specific microbiome-dependent mechanisms underlie the energy harvest efficiency of ruminants. ISME J. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2016.62 (2016).

Roehe, R. et al. Bovine host genetic variation influences rumen microbial methane production with best selection criterion for low methane emitting and efficiently feed converting hosts based on metagenomic gene abundance. PLOS Genet. 12(2), e1005846. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1005846 (2016).

Martínez-Álvaro, M. et al. Identification of complex rumen microbiome interaction within diverse functional niches as mechanisms affecting the variation of methane emissions in bovine. Front. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.00659 (2020).

Lima, J. et al. Identification of rumen microbial genes involved in pathways linked to appetite, growth, and feed conversion efficiency in cattle. Front. Genet. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2019.00701 (2019).

Li, R. W. et al. The effect of helminth infection on the microbial composition and structure of the caprine abomasal microbiome. Sci. Rep. 6, 20606. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep20606 (2016).

Lass, S. Generating super-shedders: Co-infection increases bacterial load and egg production of a gastrointestinal helminth. J. R. Soc. Interface 10(80), 20120588. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2012.0588 (2013).

de Jong, S. E., Olin, A. & Pulendran, B. The impact of the microbiome on immunity to vaccination in humans. Cell Host Microbe 28(2), 169–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2020.06.014 (2020).

Geldhof, P. et al. Vaccination of calves against Ostertagia ostertagi with cysteine proteinase enriched protein fractions. Parasite Immunol. 24(5), 263–270. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3024.2002.00461.x (2002).

N. P. du Sert et al., ‘Reporting animal research: Explanation and elaboration for the ARRIVE guidelines 2.0’, PLOS Biol., vol. 18, no. 7, p. e3000411, July 2020, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000411.

Price, D. R. G. et al. Characterisation of protective vaccine antigens from the thiol-containing components of excretory/secretory material of Ostertagia ostertagi. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.12.08.570749 (2023).

Christie, M. & Jackson, F. Specific identification of strongyle eggs in small samples of sheep faeces. Res. Vet. Sci. 32(1), 113–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0034-5288(18)32448-2 (1982).

Meyvis, Y. et al. Vaccination against Ostertagia ostertagi with subfractions of the protective ES-thiol fraction. Vet. Parasitol. 149(3–4), 239–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2007.08.014 (2007).

Taylor, S. M., Kenny, J., Edgar, H. W., Ellison, S. & Ferguson, L. Efficacy of moxidectin, ivermectin and albendazole oral drenches for suppression of periparturient rise in ewe worm egg output and reduction of anthelmintic treatment for lambs. Vet. Rec. 141(14), 357–360. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.141.14.357 (1997).

Yu, Z. & Morrison, M. Improved extraction of PCR-quality community DNA from digesta and fecal samples. Biotechniques 36(5), 808–812. https://doi.org/10.2144/04365ST04 (2004).

Seshadri, R. et al. Cultivation and sequencing of rumen microbiome members from the Hungate1000 Collection. Nat. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.4110 (2018).

Stewart, R. D. et al. Assembly of 913 microbial genomes from metagenomic sequencing of the cow rumen. Nat. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03317-6 (2018).

Wood, D. E. & Salzberg, S. L. Kraken: Ultrafast metagenomic sequence classification using exact alignments. Genome Biol. 15(3), R46. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2014-15-3-r46 (2014).

Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND | Nature Methods. Accessed: May 12, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.nature.com/articles/nmeth.3176

Ben-Shachar, M. S., Lüdecke, D. & Makowski, D. effectsize: Estimation of effect size indices and standardized parameters. J. Open Source Softw. 5(56), 2815. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.02815 (2020).

S. Champely et al., pwr: Basic functions for power analysis. (Mar. 17, 2020). Accessed: Nov. 21, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/pwr/.

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01 (2015).

Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B. & Christensen, R. H. B. lmerTest package: Tests in linear mixed effects models. J. Stat. Softw. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v082.i13 (2017).

Searle, S. R., Speed, F. M. & Milliken, G. A. Population marginal means in the linear model: an alternative to least squares means. Am. Stat. 34(4), 216–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/00031305.1980.10483031 (1980).

Wallace, R. J. et al. Archaeal abundance in post-mortem ruminal digesta may help predict methane emissions from beef cattle. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05892 (2014).

Veech, J. A. ‘Measuring biodiversity’, reference module in earth systems and environmental. Sciences https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-409548-9.10296-9 (2017).

J. Oksanen et al., vegan: Community ecology package. (Oct. 08, 2025). Accessed: Nov. 21, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/vegan/index.html.

Greenacre, M. Compositional Data Analysis in Practice (Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2018). https://doi.org/10.1201/9780429455537.

K.-A. L. Cao et al., mixOmics: Omics Data Integration Project. (2023). Bioconductor version: Release (3.17). https://doi.org/10.18129/B9.bioc.mixOmics.

Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. Publ. Protein Soc. 28(11), 1947–1951. https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.3715 (2019).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28(1), 27–30 (2000).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: Biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53(D1), D672–D677. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae909 (2025).

© 2020-2022 Graphia Technologies Ltd, ‘Graphia’, Graphia. Accessed: May 12, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://graphia.app/.

Price, D. R. G. et al. Characterisation of protective vaccine antigens from the thiol-containing components of excretory/secretory material of Ostertagia ostertagi. Vet. Parasitol. 328, 110154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2024.110154 (2024).

Campanaro, S. et al. In vitro fermentation of key dietary compounds with rumen fluid: A genome-centric perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 584–585, 683–691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.01.096 (2017).

Ratnakomala, S., Perwitasari, U. & Yopi,. The amylase production by Actinobacteria isolated from rumen fluid. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 439(1), 012019. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/439/1/012019 (2020).

Zhao, S., Min, L., Zheng, N. & Wang, J. Effect of heat stress on bacterial composition and metabolism in the rumen of lactating dairy cows. Anim. Open Access J. MDPI 9(11), 925. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9110925 (2019).

Guo, J. et al. Characterization of the bacterial community of rumen in dairy cows with laminitis. Genes 12(12), 1996. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes12121996 (2021).

C. J. Hurst, 6.4 listing of opportunistic bacteria affecting livestock mammals. In Opportunistic Bacteria Associated with Mammalian Livestock Disease. SpringerLink, vol. 5, in Advances in Environmental Microbiology, vol. 5. , Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92373-4 (2018).

Finn, D., Ouwerkerk, D., & Klieve, A. Methanotrophs from natural ecosystems as biocontrol agents for ruminant methane emissions. Meat & Livestock Australia Limited, Queensland, Monograph, 2012. Accessed: Apr. 22, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://era.dpi.qld.gov.au/id/eprint/2290/.

Kessler, A. I. & Gots, J. S. Regulation of guaC expression in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.164.3.1288-1293.1985 (1985).

Le, L. T., Huang, Z., Whiteson, K. & Jiang, S. The occurrence and diversity of antibiotic resistance and virulence factor genes in wastewater from four North American treatment plants. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 8(8), 1650–1664. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1EW00820J (2022).

Grønvold, J. et al. Development of immunity to Ostertagia ostertagi (Trichostrongylidae: Nematoda) in pastured young cattle. Acta Vet. Scand. 33(4), 305–316. https://doi.org/10.1186/BF03547296 (1992).

El-Ashram, S. et al. Microbial community and ovine host response varies with early and late stages of Haemonchus contortus infection. Vet. Res. Commun. 41(4), 263–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11259-017-9698-5 (2017).

Rakotoarivonina, H., Hermant, B., Monthe, N. & Rémond, C. The hemicellulolytic enzyme arsenal of Thermobacillus xylanilyticus depends on the composition of biomass used for growth. Microb. Cell Factories 11(1), 159. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2859-11-159 (2012).

McInerney, M. J., Mackie, R. I. & Bryant, M. P. Syntrophic association of a butyrate-degrading bacterium and methanosarcina enriched from bovine rumen fluid. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 41(3), 826–828. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.41.3.826-828.1981 (1981).

Zhang, H. et al. Association of residual feed intake with peripartal ruminal microbiome and milk fatty acid composition during early lactation in Holstein dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 105(6), 4971–4986. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2021-21454 (2022).

Dusková, D. & Marounek, M. Fermentation of pectin and glucose, and activity of pectin-degrading enzymes in the rumen bacterium Lachnospira multiparus. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 33(2), 159–163. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1472-765x.2001.00970.x (2001).

Wojciechowicz, M., Heinrichova, K. & Ziołecki, A. A polygalacturonate lyase produced by Lachnospira multiparus isolated from the bovine rumen. J. Gen. Microbiol. 117(1), 193–199. https://doi.org/10.1099/00221287-117-1-193 (1980).

Gradel, C. M. & Dehority, B. A. Fermentation of isolated pectin and pectin from intact forages by pure cultures of rumen bacteria. Appl. Microbiol. 23(2), 332–340 (1972).

Corrêa, P. S. et al. Interaction between methanotrophy and gastrointestinal nematodes infection on the rumen microbiome of lambs. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 100(6), fiae083. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsec/fiae083 (2024).