Abstract

The Aeroleaf, a Savonius-based vertical-axis wind turbine (VAWT) designed for urban environments, is compact and omnidirectional but limited in aerodynamic efficiency. In this study, the baseline Aeroleaf was compared with a conventional Savonius wind turbine (CSWT) under identical Reynolds number conditions (Re ≈ 1.7 × 10⁵, U = 7 m/s). The Aeroleaf achieved a peak Cp of 0.107 at TSR of 0.5, while the CSWT reached Cp = 0.120 at TSR = 0.8, confirming that although the Aeroleaf operates optimally at lower TSRs (advantageous for low-wind startup) its maximum efficiency is 11% lower than the CSWT. Static torque analysis further showed that the Aeroleaf produced 0.301 N·m at α = 90°, demonstrating good startup potential but limited aerodynamic output. To address these shortcomings, four optimized blade profiles (scooplet, S-shaped, Roy, and elliptical) were integrated into the Aeroleaf’s three-dimensional structure and evaluated through unsteady CFD simulations. Among these, the scooplet profile delivered the strongest improvement, achieving Cp = 0.180 at TSR = 0.6 and static torque of 0.443 N·m, corresponding to 68.2% and 47% gains over the Aeroleaf baseline. The S-shaped, Roy, and elliptical profiles achieved peak Cp values of 0.159, 0.132, and 0.124 with static torques of 0.317, 0.350, and 0.420 N·m, respectively. Dynamic torque–azimuth analysis confirmed the same order of performance, with the scooplet reaching the highest peak torque of 1.2 N·m and the largest average torque. These findings demonstrate that optimized blade profiles, especially the scooplet, overcome the Aeroleaf’s aerodynamic limits, improving efficiency and startup for reliable small-scale urban wind energy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global electricity demand is projected to triple by 2050, while the share of fossil fuels in the energy mix is expected to decline below 60% from the current 80%1. Since fossil fuels are finite and a major source of greenhouse gas emissions, renewable energy has become central to achieving sustainable growth. Wind energy, in particular, has emerged as one of the most scalable options, contributing about 4% of global electricity generation and expected to grow substantially in the coming decades2.

Wind turbines are classified into horizontal-axis wind turbines (HAWTs) and vertical-axis wind turbines (VAWTs). HAWTs dominate large-scale electricity generation due to their higher efficiency but require yaw mechanisms and sophisticated control to align with wind direction3. VAWTs, on the other hand, operate independently of wind direction and are therefore attractive for small-scale and urban applications where winds are turbulent and multidirectional4,5,6.

VAWTs consist primarily of lift-driven Darrieus and drag-driven Savonius configurations. While Darrieus turbines achieve higher aerodynamic efficiency, they suffer from poor self-starting ability and greater structural complexity. In contrast, Savonius turbines are mechanically simple, exhibit reliable self-starting at low wind speeds, and tolerate highly unsteady inflow3. These characteristics make Savonius rotors suitable for decentralized or urban applications; however, their aerodynamic shortcomings (particularly low Cp, poor startup performance under weak winds, and high drag) remain significant barriers to wider adoption7,8.

To address these limitations, extensive efforts have targeted both structural parameters and blade profiles. Parametric investigations into three-dimensional configurations have shown that aspect ratio (AR), overlap ratio (OR), number of blades, endplate diameter ratio (De/D), and number of stages strongly influence performance4,9. Optimized OR values between 0.15 and 0.18 and AR values between 1.5 and 2.0 have been shown to improve Cp and torque in controlled conditions10. Two-bladed designs are typically preferred, as additional blades induce reverse torque and increase aerodynamic losses11. Similarly, endplate ratios near unity enhance pressure capture, while larger ratios increase inertia and hinder startup12,13,14. Multi-stage arrangements can smooth torque fluctuations but excessive staging lowers Cp15,16,17. These studies confirm that fine-tuning structural parameters is critical for enhancing performance under real-world operating conditions.

In parallel, significant advances have been achieved through pre-optimized blade profiles. The Roy profile increased static torque by over 30% compared to semicircular blades and achieved experimental Cp values up to 0.27 under Reynolds numbers on the order of 10⁵ at wind speeds of 6–8 m/s18,19. The S-shaped profile, developed through optimization algorithms, achieved Cp ≈ 0.29 in simulations at similar Reynolds ranges and performed well at higher tip-speed ratios20. Elliptical blades helped reduce boundary-layer separation losses, reaching Cp values up to 0.33 numerically and ≈ 0.27 experimentally at wind speeds around 7 m/s21. The scooplet profile, which introduced a curved leading edge to enhance pressure buildup on the concave side, achieved the highest reported efficiencies for Savonius-type rotors, with Cp = 0.359 in 2D and ≈ 0.304 in 3D at Reynolds numbers above 1.2 × 10⁵22. Additional improvements have also been reported through the use of guide vanes, deflectors, and hybrid Darrieus–Savonius systems23,24,25,26,27,28,29. Nevertheless, most of these optimizations remain confined to two-dimensional analyses or simplified test conditions, leaving a clear gap regarding their aerodynamic performance when embedded in realistic three-dimensional Savonius geometries operating in urban, low-speed, and turbulent flow environments.

The Aeroleaf turbine represents a commercialized adaptation of the Savonius concept, featuring a distinctive three-dimensional blade curvature intended to reduce noise and improve performance in variable urban wind conditions. Its geometry ensures omnidirectional operation and mechanical resilience. Importantly, when benchmarked against established studies, its structural parameters, AR, OR, blade number, and endplate ratio, align closely with previously reported optimal values, thereby reinforcing the soundness of its three-dimensional configuration. However, the CFD simulations conducted in this study reveal that the Aeroleaf achieves a lower Cp than conventional Savonius turbines at similar TSRs, indicating that its aerodynamic efficiency is compromised despite its structural advantages. This discrepancy between the turbine’s claimed urban suitability and the aerodynamic weakness demonstrated through numerical analysis defines the critical research gap addressed in this work.

The present study tackles this challenge by integrating advanced 2D blade profiles (Roy, S-shaped, elliptical, and scooplet) into the three-dimensional Aeroleaf configuration. These profiles have been independently optimized in prior two-dimensional studies but have not been systematically assessed within a three-dimensional Savonius framework adapted for urban environments. The main challenge lies in the Aeroleaf’s limited aerodynamic performance, characterized by a relatively low Cp, combined with the need for strong startup torque to ensure reliable operation under low and fluctuating wind conditions. Therefore, the objective of this work is twofold: to enhance the aerodynamic efficiency by increasing Cp and to improve startup capability by maximizing static torque. To achieve this, advanced numerical methods are employed to analyze the complex aerodynamic phenomena governing Savonius-type turbines. Computational approaches such as the Finite Element Method (FEM) and the Finite Volume Method (FVM) are widely used for modeling structural and fluid interactions30,31,32, with Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) in particular serving as a powerful tool to capture unsteady flow physics33,34,35. In this study, unsteady three-dimensional CFD simulations are conducted using the k-ε Realizable turbulence model, which provides a balance between computational efficiency and accuracy in predicting flow separation, vortex interactions, and boundary-layer behavior around rotating blades36,37. Simpler models such as the standard k-ε are computationally efficient but fail to reliably capture unsteady separation and vortex dynamics, as demonstrated by Zhou and Rempfer38. The SST k-ω model offers improved near-wall predictions and separation accuracy, as shown in the work of Roy and Ducoin39, while high-fidelity approaches such as Large Eddy Simulation (LES) can resolve detailed vortex structures but remain computationally prohibitive for practical engineering applications40,41. The k-ε Realizable model, as successfully applied by Kumar and Saini42 in twisted-blade Savonius simulations, provides a robust compromise, delivering reliable three-dimensional predictions at a manageable cost. All simulations are carried out in ANSYS Fluent, a well-established commercial FVM solver, with careful attention to mesh refinement, near-wall resolution, and boundary conditions to ensure realistic representation of physical flow behavior. By explicitly modeling unsteady rotor motion, the present approach captures critical aerodynamic mechanisms (including dynamic stall, vortex shedding, and blade–wake interactions) that directly influence turbine performance. The comparative analysis of the Aeroleaf baseline with optimized profiles within a three-dimensional framework not only identifies the most effective configuration for enhancing Cp and startup behavior but also establishes design guidelines for future improvements in small-scale urban wind turbine technology.

Case study geometry

Aeroleaf 3D configuration

The CSWT reference geometry in this study follows Banerjee’s configuration (D = 0.9 m, H = 1.0 m, OR = 0.12), consisting of two semicircular buckets extruded straight in 3D without spanwise curvature. In contrast, the Aeroleaf turbine employs blades with pronounced three-dimensional curvature. To evaluate its aerodynamic characteristics in detail, a full 3D model of the Aeroleaf rotor was constructed, highlighting the unique spanwise curvature of its blades. As shown in Fig. 1, the rotor exhibits varying diameters averaging about 366 mm, which corresponds to a representative frontal swept area of 0.293 m². These averaged parameters capture the compact design of the Aeroleaf and serve as the reference values for subsequent aerodynamic analysis.

Benchmarking against earlier parametric studies on Savonius turbines, the Aeroleaf’s structural parameters, AR, OR, two-bladed configuration, and endplate ratio of unity, align closely with values previously reported as optimal for improving aerodynamic efficiency. Table 1 provides a comparison of Aeroleaf’s geometric features with established optimal ranges from the literature.

Integration of pre-optimized profiles

To address the limited aerodynamic efficiency of the Aeroleaf turbine, four pre-optimized blade profiles reported in the literature (Roy, scooplet-based, S-shaped, and elliptical) were systematically integrated into its three-dimensional configuration (Fig. 2). These profiles were selected due to their demonstrated improvements in Cp and startup performance over conventional semicircular blades under both numerical and experimental conditions2,3,4,5. The original Aeroleaf employs a circular blade cross-section. In this study, its blades were redesigned using each optimized profile while preserving the characteristic 3D curvature of the Aeroleaf structure (Fig. 3). This approach enables assessment of whether two-dimensional profile optimizations can be effectively transferred to a realistic three-dimensional urban turbine geometry.

Method

Governing equation

In this study, the Finite Volume Method (FVM) was employed to numerically solve the conservation equations governing turbulent, incompressible airflow around a Savonius turbine. This approach accurately captures the principles of mass, momentum, and energy conservation. According to the Betz momentum theory43, it is impossible to capture all the power available in the airflow. To evaluate the turbine’s aerodynamic performance, key metrics such as the Cp and Ct are utilized, as defined in Eq. 1 and Eq. 2. These coefficients are expressed as functions of the nondimensional parameter known as the TSR, which serves as a standardized measure for comparing different turbine designs. The TSR, calculated using Eq. 3, represents the ratio of the blade tip velocity to the free-stream wind velocity, providing a basis for assessing efficiency across varying operational conditions.

In above equations, H(m) is the rotor’s height, R(m) is rotor’s radius and A(m2) represent to the area of turbine facing the airflow. In addition, ωs (rad/s) represents the angular velocity, D(m) is the rotor’s overall diameter, and U(m/s) is the free-stream velocity.

Turbulence modeling

Turbulent flow equations can be addressed using various computational techniques. Direct Numerical Simulation (DNS) and Large Eddy Simulation (LES) provide highly accurate results but are limited in application due to their substantial computational demands, requiring access to advanced research facilities with high-performance computing (HPC) resources. Conversely, the Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) equations, in conjunction with appropriate turbulence closure models44, offer an optimal trade-off between computational efficiency and accuracy, making them the preferred choice for practical engineering analyses.

This study employs Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) turbulence modeling to analyze the flow. In this approach, flow variables are decomposed into two components: a time-averaged mean component and a fluctuating component. The mean component is obtained by time-averaging the flow quantities, while the fluctuating component represents deviations from the mean, capturing the turbulent fluctuations (Eq. 4).

In the RANS formulation, the decomposition of variables introduces additional variables, which necessitates supplementary equations to close the system. The form of these additional equations depends on the specific type of RANS turbulence model employed45,46. The \(\:\overline{{\text{u}}_{\text{i}}^{{\prime\:}}{\text{u}}_{\text{j}}^{{\prime\:}}}\) which represents the Reynolds stress tensor in Eq. 13, introduces six additional unknowns. To address this problem, two equation turbulence model such as \(\:\text{k}\:-\:{\upomega\:}\:\), \(\:\text{S}\text{t}\text{a}\text{n}\text{d}\text{a}\text{r}\text{d}\:\text{k}\:-\:{\upepsilon\:}\) and \(\:\text{S}\text{h}\text{a}\text{r}\:\text{S}\text{t}\text{r}\text{e}\text{s}\text{s}\:\text{T}\text{r}\text{a}\text{s}\text{p}\text{o}\text{r}\text{t}\) are commonly used, each with its own advantages and disadvantages. The \(\:\text{S}\text{t}\text{a}\text{n}\text{d}\text{a}\text{r}\text{d}\:\text{k}\:-\:{\upepsilon\:}\) model is a robust turbulence model that is fairly accurate and requires low computational resources47,48; however, it is not effective for predicting boundary layer separation. The \(\:\text{S}\text{S}\text{T}\:\text{k}-{\upomega\:}\) model combines the strengths of two turbulence models: it utilizes the \(\:\text{k}-{\upomega\:}\:\text{m}\text{o}\text{d}\text{e}\text{l}\) formulation in the near-wall regions for accurate boundary layer predictions and transitions to the \(\:\text{k}-{\upepsilon\:}\:\text{m}\text{o}\text{d}\text{e}\text{l}\) formulation in regions far from the wall to improve performance in the freestream49. The \(\:\text{R}\text{e}\text{a}\text{l}\text{i}\text{z}\text{a}\text{b}\text{l}\text{e}\:\text{K}-{\upepsilon\:}\:\text{m}\text{o}\text{d}\text{e}\text{l}\) model performs better near the wall compared to the \(\:\text{S}\text{t}\text{a}\text{n}\text{d}\text{a}\text{r}\text{d}\:\text{k}\:-\:{\upepsilon\:}\) model50. Both the \(\:\text{S}\text{S}\text{T}\:\text{k}-{\upomega\:}\) and \(\:\text{R}\text{e}\text{a}\text{l}\text{i}\text{z}\text{a}\text{b}\text{l}\text{e}\:\text{K}-{\upepsilon\:}\:\text{m}\text{o}\text{d}\text{e}\text{l}\) models achieve good accuracy near the wall; however, the computational cost of the \(\:\text{R}\text{e}\text{a}\text{l}\text{i}\text{z}\text{a}\text{b}\text{l}\text{e}\:\text{K}-{\upepsilon\:}\:\text{m}\text{o}\text{d}\text{e}\text{l}\) is lower. On the other hand, the \(\:\text{R}\text{e}\text{a}\text{l}\text{i}\text{z}\text{a}\text{b}\text{l}\text{e}\:\text{k}-{\upepsilon\:}\:\text{m}\text{o}\text{d}\text{e}\text{l}\) demonstrates superior agreement with experimental results compared to all other turbulence models51,52.Therefore, in this study, the \(\:\text{R}\text{e}\text{a}\text{l}\text{i}\text{z}\text{a}\text{b}\text{l}\text{e}\:\text{K}-{\upepsilon\:}\:\text{m}\text{o}\text{d}\text{e}\text{l}\) is used for calculating the transport of \(\:\text{k}\) and \(\:{\upepsilon\:}\).

\(\:\text{R}\text{e}\text{a}\text{l}\text{i}\text{z}\text{a}\text{b}\text{l}\text{e}\:\text{K}-{\upepsilon\:}\:\text{m}\text{o}\text{d}\text{e}\text{l}\) provides equations for turbulent kinetic energy \(\:\left(\text{k}\right)\) (Eq. 5) and turbulent dissipation rate \(\:\left({\upepsilon\:}\right)\) (Eq. 8) as presented below respectively53. The Reynolds stress tensor is modeled using two transport equations. The \(\:\text{k}\) term represents the turbulent kinetic energy, while the \(\:{\upepsilon\:}\) term denotes the dissipation rate of kinetic energy. Equations 5 and 8 represent the transport equations for \(\:\text{k}\) and \(\:{\upepsilon\:}\).

In Eq. 5, \(\:{{\upmu\:}}_{\text{t}}\) represents the turbulence viscosity, which is calculated using Eq. 6. Hear, \(\:{{\upsigma\:}}_{\text{k}}=1\) is a model constant. \(\:{\text{G}}_{\text{k}}\) denotes the production of turbulence kinetic energy caused by velocity gradients, while \(\:{\text{G}}_{\text{b}}\) accounts for the turbulence kinetic energy generated by buoyancy forces. Finally, \(\:{\text{S}}_{\text{k}}\) Represents an additional source term that may arise from external effects or user-defined contribution. It is known that, in the \(\:\text{R}\text{e}\text{a}\text{l}\text{i}\text{z}\text{a}\text{b}\text{l}\text{e}\:\text{K}-{\upepsilon\:}\:\text{m}\text{o}\text{d}\text{e}\text{l}\), \(\:{\text{C}}_{{\upmu\:}}\) is not constant and is instead determined dynamically during the solution process using Eq. 7. In the dynamic calculation of \(\:{\text{C}}_{{\upmu\:}}\), \(\:{\text{A}}_{0}=4.04\) is a model constant, while \(\:{\text{A}}_{\text{s}}=\sqrt{6}\text{c}\text{o}\text{s}\left({\varnothing}\right)\) is a factor that depends on the strain and rotation rates of the flow. Here, \(\:{\varnothing}\) is a parameter related to the strain and rotation rates. The term \(\:{\text{U}}^{\text{*}}=\sqrt{{\text{S}}_{\text{i}\text{j}}{\text{S}}_{\text{i}\text{j}}+{{\Omega\:}}_{\text{i}\text{j}}{{\Omega\:}}_{\text{i}\text{j}}}\) represents the combined effects of the strain rate and rotation rate tensors, where \(\:{\text{S}}_{\text{i}\text{j}}\) is the strain rate and \(\:{{\Omega\:}}_{\text{i}\text{j}}\) is the rotation rate Tensor.

The transport equation for the dissipation rate \(\:{\upepsilon\:}\) is calculated using Eq. 8.

In the above equation \(\:{{\upsigma\:}}_{{\epsilon}}=1.2\), \(\:{\text{C}}_{1{\epsilon}}=1.44\:\text{a}\text{n}\text{d}\:{\text{C}}_{2}=1.9\) are model constants. The coeffect \(\:{\text{C}}_{1}\) and other variables are determined using Eqs 9 to 11.

Continuity and momentum equations

a) Continuity Eq.

In the given equation, \(\:\overline{{\text{u}}_{\text{i}}}\) represents the mean velocity of the airflow, \(\:{\text{u}}_{\text{i}}^{{\prime\:}}\) denotes the fluctuating component of the velocity magnitude induced by the effects of turbulence, and \(\:{\text{x}}_{\text{i}}\) corresponds to the direction of the flow.

b) Momentum equation:

The momentum equation must be solved alongside the mass balance Eq.

Eq.13 represents the momentum equation, where t denotes time, \(\:\stackrel{-}{\text{p}}\) is the average pressure, \(\:{\uprho\:}\) is the air density, and \(\:{\upmu\:}\) is the dynamic viscosity of atmospheric air54.

Computational domain and boundary conditions

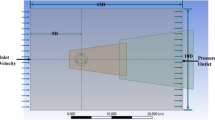

The computational setup was divided into two regions (a stationary outer domain and a rotating inner domain) to capture the aerodynamic behavior of the rotor while minimizing boundary effects, as illustrated in Fig. 4. The stationary domain was constructed as a rectangular cuboid with dimensions of 20D, 12D, and 10 H. The rotating domain was defined as a cylindrical subdomain enclosing the rotor, with a diameter of 1.2D and a height of 1.1 H. These dimensions were selected based on values recommended in the literature and were confirmed through our own sensitivity analysis42,50,55,56.

The sensitivity analysis of the computational domain is summarized in Fig. 5, where the effect of varying key geometric parameters on the predicted Cp was systematically evaluated. For the stationary domain, four parameters were examined: (a) the inlet distance, (b) the outlet distance, (c) the domain width, and (d) the domain height. The results show that increasing the inlet distance beyond five rotor diameters produced negligible changes in Cp, confirming that a value of 5D provides sufficient flow development upstream. Similarly, increasing the outlet distance beyond 15D caused no further variation in Cp, indicating that wake recovery was adequately captured. The domain width was particularly important as it governs the blockage ratio. At the selected width of 12D, the blockage ratio was sufficiently low to avoid confinement effects, and further increases in width had no meaningful influence on Cp. Finally, the stationary domain height converged at around 10 H, ensuring enough clearance above and below the turbine to minimize vertical boundary interactions. These findings confirm that the selected stationary domain dimensions eliminate artificial acceleration of the flow and are consistent with values recommended in the literature.

For the rotating domain, two parameters were analyzed: (e) the rotating zone diameter and (f) the rotating zone height. As shown in Fig. 5, Cp increased initially with domain size but quickly reached convergence, stabilizing at a diameter of 1.2D and a height of 1.1 H. Below these values, the smaller rotating domain imposed artificial shear at the interface with the stationary region, slightly underpredicting rotor performance. Above these values, no significant changes in Cp were observed, confirming that the selected configuration provides an accurate balance between computational efficiency and solution accuracy. The consistent convergence trends across both stationary and rotating regions demonstrate that the adopted computational domain dimensions are both robust and fully aligned with recommendations reported in previous CFD studies of Savonius and Darrieus turbines.

Boundary conditions are also shown in Fig. 4. At the inlet, a uniform velocity of 7 m/s with a turbulence intensity of 5% was specified, while a pressure outlet with atmospheric pressure was imposed at the outlet. The turbine blades were modeled with a no-slip wall condition, and symmetry boundary conditions were applied on the side walls to minimize wall effects. The cylindrical rotating domain was assigned a constant angular velocity, and an interface condition was implemented at the contact surface between the rotating and stationary regions to ensure smooth data transfer.

Mesh generation and independence study

Boundary layer calculation

The performance evaluation of the Savonius rotor is fundamentally linked to the accurate computation of torque on the rotor walls, which serves as the basis for determining the Cp. Torque is calculated on the rotor’s surface, where a no-slip boundary condition is applied. This boundary condition generates a boundary layer near the rotor walls, necessitating precise near-wall treatment to ensure accurate simulation results. Within the boundary layer, the viscous sublayer forms immediately adjacent to the wall. In this thin region, viscous forces dominate over turbulent effects, and the flow velocity increases with distance from the wall. Proper resolution of the viscous sublayer is crucial for capturing accurate wall shear stress, particularly in simulations involving enhanced wall functions. To resolve the boundary layer, fine meshing is required in the near-wall regions, commonly referred to as boundary layer meshing. This mesh is typically generated using meshing software, where its accuracy depends on critical input parameters defined before meshing. Among these, the distance of the first mesh node from the rotor wall is particularly significant, as it determines the mesh’s suitability for capturing near-wall flow phenomena.

The parameter y+, a dimensionless measure of wall proximity, is widely used to guide the calculation of this distance. For the chosen viscous model in this study, the y+ value was set to 5 to achieve optimal near-wall resolution. Using the inflation technique, the first layer thickness was calculated based on the value and the rotor dimensions. The resulting thickness of the first layer was determined to be 0.23 mm, ensuring that the mesh captures the viscous sublayer accurately. This approach enables the boundary layer effects to be modeled effectively, ensuring reliable predictions of rotor performance53,57,58. The distance of the first node from the wall is calculated using Eq. 1444:

In Eq 0.14, y+ is a non-dimensional parameter, and y is distance of first node from the wall. \(\:{\text{u}}_{\text{t}}\) represents the friction velocity, which is calculated using Eq 0.15. \(\:{{\uptau\:}}_{\text{w}}\) is the wall shear stress, which can be calculated using Eq 0.16 and the local coeffect of friction, \(\:{\text{C}}_{\text{f}}^{{\prime\:}}\), is estimated using the empirical formula given by Eq 0.1759. The calculated values of mesh parameters are shown in Table 2.

Mesh and time step independency

Mesh resolution plays a crucial role in determining the accuracy of CFD simulations, and therefore a mesh independence study was performed to ensure that the solution is unaffected by further refinement. The analysis was first conducted on the CSWT, with four grid levels ranging from 1.1 to 4.5 million elements, as summarized in Table 3. Each refinement step included increases in inflation layers and reductions in growth rate, leading to improvements in near-wall resolution (average y + decreasing from 9.63 in Grid 1 to 3.27 in Grid 4). The torque values obtained show convergence from 3.377 N.m to 3.495 N.m, with less than 0.5% variation between Grid 3 (3.46 million cells) and Grid 4 (4.5 million cells). Based on this, Grid 3 was selected for all subsequent simulations, providing an optimal balance between accuracy and computational cost. Representative meshes for the four grid levels are illustrated in Fig. 6.

To further verify near-wall resolution, Fig. 7 presents the y + contour for the scooplet-based turbine, which represents the most geometrically complex rotor among those tested. The results confirm that y + values remain below 5 near the blade edges, demonstrating that the mesh adequately resolves the viscous sublayer and validating its applicability for all turbine configurations.

A polyhedral mesh was ultimately employed for all simulations, as it significantly reduces computational overhead compared to pure tetrahedral meshes while maintaining high accuracy. The domains were initially meshed using tetrahedral elements and later converted to polyhedral elements within the Fluent environment, as illustrated in Fig. 8. The final mesh quality, with an inverse orthogonal quality of ~ 0.93, indicates that the computational grids used in this study, were of high quality, with values well within the acceptable range reported in the literature.

The selection of an appropriate time step is critical to ensure both numerical accuracy and computational efficiency. To evaluate sensitivity, torque evolution was analyzed using angular increments of 3°, 2°, 1°, and 0.5° per step as presented in Fig. 9. The results showed that coarse steps of 3° and 2° introduced noticeable deviations, while 1° and 0.5° steps produced nearly identical torque responses. Since 0.5° offers no significant improvement over 1° but doubles the computational cost, a time step of 1° per step was adopted in this study, consistent with previous recommendations23, ensuring reliable resolution of unsteady flow phenomena at practical cost.

Set up and solution

Ansys Fluent was used to perform the CFD simulations, applying a three-dimensional transient analysis approach to accurately calculate the flow characteristics. Interfaces were defined at all shared boundaries between the domains to ensure continuity and air at \(\:25^\circ\:\text{C}\) was selected. The problem is initially formulated under steady-state conditions; however, a transient flow model is employed to account for mesh motion required for region definition. All simulations are conducted under unsteady-state conditions to ensure convergence of the solution and numerical stability. A pressure-based solver is utilized, with the pressure-velocity coupling handled using the SIMPLE (Semi-Implicit Method for Pressure-Linked Equations) algorithm. To improve the accuracy of the computational results, a second-order upwind scheme is implemented for the spatial discretization of convection terms, including the momentum equation, turbulent kinetic energy, and turbulent dissipation rate. This approach minimizes interpolation errors and numerical diffusion, thereby enhancing the precision and reliability of the simulations60,61,62,63,64. The least-squares cell-based algorithm is employed to compute all gradients, while a first-order implicit formulation is utilized for the transient algorithm.

Validation of CFD model

The accuracy of the numerical framework was validated against the experimental and numerical results of Banerjee, who studied a CSWT with a rotor diameter of 0.9 m, height of 1 m, and OR of 0.12. The same geometry was modeled in this study, and performance was assessed over a TSR range of 0.2–1.2.

Figure 10 compares the predicted Cp and Ct with Banerjee’s experimental and numerical results. In the experimental study, the maximum Cp = 0.23 was observed at TSR = 0.74, while in the numerical study, the maximum Cp = 0.21 occurred at TSR = 0.8 using the SST k-ω turbulence model. In the present simulations, the realizable k-ε model predicted a peak Cp of 0.21 at TSR = 0.8, showing excellent agreement with both benchmarks. The deviation of the maximum Cp from the experimental value remains within ~ 9%, confirming that the realizable k-ε model can capture peak performance trends with high fidelity and yields results very close to the widely accepted SST k-ω model, consistent with recent studies recommending realizable k-ε for VAWT simulations in complex separated flows. Similarly, the Ct curve from the present study follows the same overall trend as Banerjee’s results, albeit with slightly lower values across the TSR range. This deviation in Cp and Ct can be attributed to differences in turbulence modeling (realizable k-ε versus SST k-ω), simplifications in the CFD setup such as the exclusion of shafts and support structures, and near-wall resolution effects. Experimental uncertainties, including wind tunnel blockage, turbulence intensity, and small geometric tolerances, may also contribute. Despite these minor deviations, the close agreement of Cp and the consistent Ct trend confirm that the present model is reliable and validated.

To further verify statistical stability, the torque history was monitored across successive revolutions of the CSWT configuration. Previous studies have indicated that solution convergence is typically reached after three to four revolutions, with Mohammad et al3. reporting convergence by the third revolution and Schwidran et al65. by the fourth. In this study, five full revolutions were simulated, and the average torque per revolution was calculated to assess stability. As shown in Fig. 11, the average torque values across the first to fifth revolutions were − 4.264, − 3.408, − 3.560, − 3.462, and − 3.403 N·m, respectively. These results demonstrate that the solution achieved ~ 99% convergence by the third revolution, with subsequent variations below 1%. The inclusion of a fourth and fifth revolution further confirmed consistency, verifying that the numerical setup had reached a reliable steady-state response.

Results and discussion

To evaluate the aerodynamic performance of the Aeroleaf wind turbine, four optimized blade profiles were analyzed and compared with the original circular profile. Each optimized profile was integrated into the 3D model, and numerical simulations were conducted to assess their impact on the Cp.

Aeroleaf turbine and CSWT

The performance of the Aeroleaf turbine was evaluated against the CSWT under identical simulation conditions, with both geometries scaled to maintain the same Reynolds number (Re ≈ 1.7 × 10⁵) at a wind speed of 7 m/s (A = 0.293 m², CSWT diameter = 0.366 m, height = 0.8 m). This ensured that the comparison remained independent of geometric scaling effects, as all other parameters, including turbulence intensity, were kept consistent.

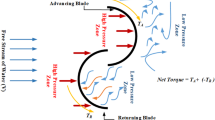

Figure 12 presents the variation of Cp and Ct with TSR. The Aeroleaf achieves its maximum Cp of 0.107 at TSR = 0.5, confirming its optimal performance at lower rotational speeds compared to the CSWT, which reaches a higher Cp.max of 0.12 at TSR = 0.8. This shift in peak performance toward lower TSR supports the prediction that the Aeroleaf’s three-dimensional rotor curvature enhances momentum capture in low-speed conditions, making it well-suited for urban and low-wind-speed applications. In practical terms, the Aeroleaf’s optimal TSR of 0.4–0.6 corresponds to a feasible operating speed of about 2.3 RPS at 7 m/s, reinforcing its advantage in environments where startup reliability is critical.

The Ct distribution further highlights this trade-off. At low TSR values, the Aeroleaf exhibits higher Ct values than the CSWT, confirming its superior static torque and startup potential. However, as TSR increases, the CSWT demonstrates consistently higher Ct, indicating stronger torque generation at higher rotational speeds. Overall, while the Aeroleaf demonstrates better performance in the low-TSR regime, both its maximum Cp and Ct remain lower than those of the CSWT.

This outcome confirms the expected gap. While the Aeroleaf’s three-dimensional configuration improves performance under low-speed inflow and offers structural advantages, its aerodynamic efficiency remains lower than that of the CSWT. To address this limitation, the present study integrates pre-optimized blade profiles into the Aeroleaf’s three-dimensional structure, with the goal of combining its low-speed operability with enhanced aerodynamic efficiency.

Performance comparison of aeroleaf and novel turbines

To enhance the Aeroleaf’s aerodynamic efficiency while preserving its low-TSR operability, four pre-optimized blade profiles (elliptical, Roy, S-shaped, and scooplet) were integrated into the Aeroleaf’s three-dimensional configuration and assessed under the same conditions (U = 7 m/s, Re ≈ 1.7 × 10⁵). Figure 13 plots Cp and Ct as a function of TSR for the Aeroleaf baseline and all novel turbines.

The optimized turbines shift the performance envelope upward across the low-TSR range. The elliptical turbine achieves a peak Cp = 0.137 at a TSR = 0.5, delivering a 28% gain over the Aeroleaf baseline (maximum Cp = 0.107). The Roy turbine reaches Cp = 0.147 at a TSR = 0.6, a 37.4% increase, reflecting improved pressure capture and a longer moment arm on the advancing blade. The S-shaped turbine attains Cp = 0.159 at TSR = 0.7, a 49.5% rise, consistent with better momentum redirection at intermediate TSRs. The scooplet turbine provides the strongest improvement, peaking at Cp = 0.179 at TSR = 0.6, which is a 68.2% increase relative to the Aeroleaf. These trends are physically consistent with the geometry of each profile. The elliptical section reduces adverse pressure gradients and delays separation at low TSR. The Roy profile enhances the effective arm of force near α = 90° and 270°. The S-shape promotes smoother redirection of the oncoming flow toward the concave side at mid TSR. The scooplet, with its curved leading edge, raises static pressure on the advancing bucket and delays separation on the back of that blade, which allows more flow to reach the returning bucket at α = 0° and 180°.

Torque behavior closely follows the aerodynamic performance trends. Across the low-TSR band, all optimized turbines increase Ct relative to the Aeroleaf baseline, with the scooplet design showing the largest improvement. The S-shaped and Roy profiles also yield noticeable gains, while the elliptical profile provides a moderate but consistent enhancement. At higher TSR, however, the CSWT produces greater Ct, reflecting its lower drag penalties on the returning blade. These results confirm that while the optimized Aeroleaf designs outperform the baseline configuration at low TSR, their torque generation diminishes more rapidly at higher TSR compared to the lift-driven CSWT.

Similarly, the Cp curves exhibit the characteristic roll-off of drag-driven turbines at elevated TSR, driven by increased negative torque on the returning blade and stronger form drag. By contrast, the CSWT maintains performance longer as lift contributions scale more effectively with rotational speed. This reduction at a high TSR does not undermine the objective of the present study, since the relevant operating regime for urban, low-wind sites is TSR ≈ 0.4–0.7, where the optimized profiles (particularly the scooplet and S-shaped designs) demonstrate significantly higher Cp and Ct. Overall, integrating pre-optimized profiles into the Aeroleaf’s three-dimensional geometry improves aerodynamic efficiency in the intended low-TSR operating window while preserving the structural and inflow resilience of the base design.

Startup performance and flow field analysis of novel rotors

Static torque evaluation and results

Startup capability was assessed by calculating the static torque of the novel rotors under fixed conditions. Each turbine was held at an azimuthal angle of 90°, the most critical orientation for self-starting, where the advancing blade faces the incoming flow and the returning blade experiences maximum drag. Simulations were performed at an inlet velocity of 7 m/s with a turbulence intensity of 5%. Aerodynamic forces on the blades were resolved from the pressure and shear stress distributions, and the net torque was obtained by integrating these forces around the axis of rotation.

The results, shown in Fig. 14, indicate clear differences among the designs. The scooplet rotor achieved the highest static torque at 0.443 N·m, followed by the elliptical (0.420 N·m), Roy (0.350 N·m), and S-shaped (0.317 N·m) profiles, while the baseline Aeroleaf produced only 0.301 N·m. Relative to the Aeroleaf, the scooplet provided a 47% increase, the elliptical a 39% increase, the Roy a 16% increase, and the S-shape a 5% increase. These results confirm that all redesigned rotors improved the Aeroleaf’s startup potential, with the scooplet geometry offering the most effective enhancement for reliable operation in low-speed and urban wind conditions.

Torque–Azimuth characteristics

Building on the static torque evaluation, which quantified startup capability at the critical fixed orientation (α = 90°), the torque–azimuth behavior was further analyzed under dynamic conditions to confirm these findings. Figure 15 presents the instantaneous torque variation over one full revolution for the four rotors operating at TSR = 0.7 and an inlet velocity of 7 m/s. Unlike the static case, where the rotor was fixed, this analysis captures the unsteady aerodynamic loading during continuous rotation.

The results show that the scooplet rotor consistently produces the strongest torque response, with peak values reaching approximately 1.2 N·m. The Roy and S-shaped profiles achieve maximum torques of about 0.95 N·m and 0.91 N·m, while the elliptical rotor peaks at 0.90 N·m. Although peak torque values differ, the average torque over one cycle follows the same order observed in the static case: scooplet > elliptical > Roy > S-shape. This agreement confirms that the static torque assessment at α = 90° reliably reflects startup potential, while the torque–azimuth analysis provides complementary evidence of superior cycle-averaged performance by the scooplet profile.

Flow field analysis

The aerodynamic mechanisms underlying the torque results can be explained by analyzing the velocity, streamline, and pressure fields of the rotors. These flow visualizations reveal how blade geometry governs wake development, vortex dynamics, and surface pressure loading, which directly determine torque generation and startup capability.

Velocity contours

The torque differences discussed in the previous section can be directly linked to the underlying flow structures. Figure 16 shows velocity contours at three axial planes (200, 400, and 600 mm above the rotor base), illustrating wake development for the four novel turbines. The S-shape, Roy, and elliptical rotors generate large separated shear layers and recirculation zones in the wake of the returning blade. These unsteady eddies increase turbulence intensity and dissipate energy, leading to higher aerodynamic losses. In contrast, the scooplet rotor exhibits a much smoother wake with weaker vortex structures, confirming that its curvature helps redirect incoming flow more efficiently and reduces adverse pressure gradients. This smoother wake development supports the higher static and average torque observed for the scooplet design.

To better resolve near-blade dynamics, Fig. 17 presents close-up velocity contours at the mid-plane. In the S-shaped rotor (Fig. 17a), boundary layer separation occurs on the top of the returning bucket, generating a localized low-velocity zone. When separation occurs prematurely, it raises pressure on the returning blade surface and produces negative torque. In this case, separation occurs only after the blade’s main curvature, which helps to delay the onset of negative torque but does not completely eliminate it.

For the Roy rotor (Fig. 17b), part of the incoming flow passes through the central gap between the blades and reattaches on the downstream side of the returning bucket. This additional momentum input increases the driving torque compared to the S-shaped case, though unsteady wake interactions still introduce fluctuations. A similar mechanism is observed in the elliptical rotor (Fig. 17d), where flow redirected through the central passage also enhances torque on the returning blade, although boundary layer separation remains more pronounced than in the scooplet design.

In contrast, the scooplet rotor (Fig. 17c) demonstrates two distinct advantages. First, a low-velocity region forms inside the scooplet extension, corresponding to a high-pressure zone that enhances positive driving torque on the advancing blade. Second, flow passing between the scooplet extension and the main rotor is redirected with higher momentum, contributing additional torque while stabilizing the wake. Importantly, boundary layer separation on the returning bucket occurs only near the end of the blade, which delays negative torque generation. These combined effects explain why the scooplet consistently delivers superior static and dynamic torque performance compared to the other profiles.

Streamline plots

Figure 18 illustrates the velocity streamlines at the mid-plane, highlighting vortex dynamics. The Roy, S-shape, and elliptical rotors produce asymmetric vortex pairs, where one vortex dominates in size and strength. This imbalance results in uneven blade loading, unsteady torque, and higher cyclic fluctuations. In contrast, the scooplet rotor exhibits nearly symmetrical vortex structures, reflecting balanced pressure distribution between the advancing and returning blades. This symmetry stabilizes the wake and reduces torque oscillations, complementing the improvements observed in the torque–azimuth plots.

Pressure fields

Pressure contours at the mid-plane are shown in Fig. 19. The S-shape, Roy, and elliptical designs exhibit pronounced low-pressure zones near the tips of the advancing blades, caused by abrupt curvature and early boundary layer detachment. These pressure deficits reduce the effective driving force and increase aerodynamic losses. The scooplet profile avoids this unfavorable tip separation, instead maintaining higher and more uniform pressure loading along the blade. The greater pressure differential between the concave and convex surfaces of the scooplet blade directly enhances driving torque, explaining its superior static torque compared to other turbines.

Comparison with recent studies on VAWT performance improvements

This study demonstrated that integrating optimized blade profiles into the Aeroleaf turbine leads to substantial performance gains. Among the tested designs, the scooplet-based rotor achieved the best results, with a peak Cp of 0.18 at TSR = 0.6, corresponding to a 68.2% improvement over the baseline Aeroleaf, and a static torque of 0.443 N·m, ensuring reliable self-starting capability. The S-shaped, Roy, and elliptical profiles provided additional gains of 45.6%, 23.4%, and 15.9%, respectively.

As shown in Table 4, recent studies on both Savonius and Darrieus turbines have reported improvements through strategies such as J-foil modifications, airfoil optimization, blade height adjustments, Gurney flaps, and vortex deflectors, with Cp enhancements typically ranging from 9% to over 40%. While effective, these approaches often require added components or structural modifications that may complicate manufacturing or limit deployment in small-scale and urban applications.

By comparison, the scooplet-modified Aeroleaf rotor provided a 68.2% increase in efficiency and the highest static torque without additional attachments or complex structural changes, making it a practical and competitive alternative to more elaborate modification strategies. These results confirm that simple but carefully optimized blade geometries can deliver improvements comparable to advanced aerodynamic interventions, while preserving the mechanical simplicity and robustness that are critical for urban wind energy applications.

Conclusion

This study investigated the aerodynamic performance and startup behavior of the Aeroleaf wind turbine after integrating four optimized blade profiles (scooplet, S-shaped, Roy, and elliptical) into its three-dimensional structure. This study validated a CFD framework for VAWT analysis by reproducing the results of Banerjee’s CSWT experiments with good agreement (maximum Cp = 0.21 at TSR = 0.8 versus 0.23 experimental). After validation, the baseline Aeroleaf turbine was compared directly with the CSWT at Re ≈ 1.7 × 10⁵ and U = 7 m/s. The Aeroleaf achieved its peak Cp = 0.107 at TSR = 0.5, whereas the CSWT reached Cp = 0.120 at TSR = 0.8. Thus, while the Aeroleaf operated optimally at a lower TSR, advantageous for low-speed startup, its maximum Cp was ~ 11% lower than the CSWT, confirming its aerodynamic shortcoming. The Aeroleaf also delivered a static torque of 0.301 N·m at α = 90°, which, although higher at low TSR compared to the CSWT, remained insufficient for consistent startup.

To address this limitation, four optimized blade profiles were integrated into the Aeroleaf geometry. The scooplet profile delivered the strongest improvement, achieving a maximum Cp of 0.180 at a TSR of 0.6, representing a 68.2% gain over the Aeroleaf baseline. The S-shaped rotor reached a maximum Cp of 0.159 at a tip-speed ratio of 0.7, corresponding to a 45.6% increase. The Roy profile attained 0.132 at a tip-speed ratio of 0.7, marking a 23.4% improvement, while the elliptical rotor achieved 0.124 at a tip-speed ratio of 0.6, showing a 15.9% enhancement.

Static torque evaluations confirmed the same order of improvement. The scooplet rotor produced 0.443 N·m, which is 47% higher than the Aeroleaf baseline. The elliptical rotor generated 0.420 N·m, corresponding to a 39% gain. The Roy rotor reached 0.350 N·m, reflecting a 16% increase, while the S-shape produced 0.317 N·m, offering a 5% improvement.

Dynamic torque–azimuth analysis at a tip-speed ratio of 0.7 further reinforced these findings. The scooplet rotor reached a peak cycle torque of about 1.2 N·m, compared to 0.95 N·m for the Roy profile, 0.91 N·m for the S-shaped rotor, and 0.90 N·m for the elliptical rotor. More importantly, the scooplet maintained the highest average torque over one revolution, confirming its superior aerodynamic and startup performance. Flow field analysis linked these improvements to physical mechanisms: the scooplet reduced wake eddies, delayed separation on the returning blade, generated symmetrical vortex pairs, and sustained stronger pressure differentials across its blades. These aerodynamic features directly explain its superior Cp and torque performance.

In summary, while the Aeroleaf inherently benefits from a lower optimal TSR, its lower maximum Cp represents a key drawback. Incorporating optimized profiles, particularly the scooplet, overcomes this shortcoming, yielding 68.2% higher aerodynamic efficiency and 47% higher static torque compared to the baseline. These results confirm that simple geometry refinements can transform the Aeroleaf into a practical, efficient solution for small-scale, low-wind, and urban wind energy applications.

While this study provides a comprehensive numerical assessment of optimized Aeroleaf configurations, opportunities remain to broaden its scope in future work. The analysis was conducted at 7 m/s, representative of typical low-wind urban conditions, ensuring clear insights into performance at the operating regime most relevant for the Aeroleaf. Extending this framework to multiple wind speeds and turbulent inflows would further enrich the characterization of performance under diverse environmental conditions. Similarly, complementing the present CFD framework with experimental measurements of the modified Aeroleaf turbines would provide valuable validation and support technology transfer toward field applications. Future investigations may also incorporate structural integrity, acoustic behavior, and long-term durability, as well as explore hybrid or adaptive blade geometries. Together, these directions build directly on the present findings and can accelerate the development of robust, efficient, and practical small-scale wind turbines for urban environments.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- \(AR\) :

-

\(aspect\:ratio\:\left(=H/D\right)[-]\)

- \({C}_{p}\) :

-

\(power\:coefficient\left(={P}_{turbine}/{P}_{available}\right)[-]\)

- \({C}_{T}\) :

-

\(torque\:\:coefficient\:\left(=\frac{T}{\frac{1}{2}\rho\:A{V}^{2}R}\right)[-]\)

- \({\text{C}}_{\text{f}}^{{\prime\:}}\) :

-

\(local\:coeffect\:of\:friction\:[-]\)

- \(\:D\) :

-

\(\:diameter\:of\:turbine\:\left[m\right]\)

- \(d\) :

-

\(blade/bucket\:diameter\:\left[m\right]\)

- \(\:D_f\) :

-

\(\:\:drag\:force\:\:\left[N\right]\)

- \(\:D_l\) :

-

\(\:\:lift\:force\:\:\left[N\right]\)

- e :

-

\(\:\:overlap\:distance\:\left[m\right]\)

- \(H\) :

-

\(\:\:height\:of\:turbine\:\left[m\right]\)

- \(k\) :

-

\(\:\:turbulence\:kinetic\:energy\:\left[\frac{{m}^{2}}{{s}^{2}}\right]\)

- \(OR\) :

-

\(overlap\:ratio\:\:\left(=\frac{e}{d}\right)[-]\)

- \(Re\) :

-

\(reynolds\:number\:(\:=\frac{\rho\:DV}{\mu\:})\:[-]\)

- \(\tau_w\) :

-

\(wall\:shear \: stress [Pa]\)

- \(TSR\) :

-

\(tip-speed\:ratio\:(=\frac{\pi\:ND}{60V})\:[-]\)

- \(u_t\) :

-

\(\:\:friction\:velocity\:\left[\frac{m}{s}\right]\)

- \(y\) :

-

\(\:the\:distance\:from\:the\:wall\:to\:the\:centroid\:of\:the\:first\:fluid\:cell\:\left[m\right]\)

- \(y^+\) :

-

\(dimensionless\:wall\:distance\:[-]\)

- \(\:\alpha\:\) :

-

\(\:\:angle\:of\:attack\:\left[^\circ\right]\)

- \(\:\omega\:\) :

-

\(\:\:specific\:rate\:of\:turbulent\:dissipation\:\left[\frac{1}{s}\right]\)

- \(\:{\omega\:}_{s}\) :

-

\(\:\:rotational\:speed\:of\:the\:turbine\:\left[\frac{rad}{s}\right]\)

- \(\:\epsilon\:\) :

-

\(\:turbulent\:dissipation\:rate\:\left[\frac{{m}^{2}}{{s}^{2}}\right]\)

- CSWT:

-

Conventional Savonius Wind Turbine

- FVM:

-

Finite Volume Method

- HAWT:

-

Horizontal-Axis Wind Turbines

- RPS:

-

Revolutions per Second

- SWT:

-

Savonius Wind Turbine

- VAWT:

-

Vertical-Axis Wind Turbines

References

Hostick, D., Belzer, D., Hadley, S., Markel, T. & Marnay, C. Projecting Electricity Demand in 2050 (Oak Ridge National Laboratory Report, 2014).

Ram, M., Aghahosseini, A. & Breyer, C. Job creation during the global energy transition towards 100% renewable power system by 2050. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 156, 119–135 (2020).

Su, R., Gao, Z., Chen, Y., Zhang, C. & Wang, J. Large-eddy simulation of the influence of hairpin vortex on pressure coefficient of an operating horizontal axis wind turbine. Energy Convers. Manag. 267, 115864 (2022).

Abdolahifar, A. & Zanj, A. A review of available solutions for enhancing aerodynamic performance in Darrieus vertical-axis wind turbines: A comparative discussion. Energy Convers. Manag. 327, 119575 (2025).

Maldar, N. R., Ng, C. Y. & Oguz, E. A review of the optimization studies for Savonius turbine considering hydrokinetic applications. Energy Convers. Manag. 226, 113495 (2020).

Hosseini Rad, S. et al. A systematic study on the aerodynamic performance enhancement in H-type Darrieus vertical axis wind turbines using vortex cavity layouts and deflectors. Phys. Fluids. 36 (12), 125170 (2024).

Nachaiyaphum, K. & Photong, C. An electric power generation improvement for small Savonius wind turbines under low-speed wind. Indonesian J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 29 (2), 618–625 (2023).

Im, H. & Kim, B. Power performance analysis based on Savonius wind turbine blade design and layout optimization through rotor wake flow analysis. Energies (Basel). 15 (24), 9500 (2022).

Talukdar, P. K., Sardar, A., Kulkarni, V. & Saha, U. K. Parametric analysis of model Savonius hydrokinetic turbines through experimental and computational investigations. Energy Convers. Manag. 158, 36–49 (2018).

Alom, N. & Saha, U. K. Evolution and progress in the development of Savonius wind turbine rotor blade profiles and shapes. J. Sol Energy Eng. 141 (3), 030801 (2019).

Ramadan, A., Yousef, K., Said, M. & Mohamed, M. H. Shape optimization and experimental validation of a drag vertical axis wind turbine. Energy 151, 839–853 (2018).

Banerjee, A. Performance and flow analysis of an elliptic bladed Savonius-style wind turbine. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy. 11 (3), 033307 (2019).

Seifi Davari, H., Botez, R. M., Davari, S., Chowdhury, M., Hosseinzadeh, H. & H. & Blade height impact on self-starting torque for Darrieus vertical axis wind turbines. Energy Convers. Management: X. 24, 100814 (2024).

Toor, Z., Bahaidarah, H. M., Zayed, M. E. & Rehman, S. Experimental evaluation of a NACA-0022 airfoil under steady and dynamic pitch oscillations at low Reynolds numbers for wind power applications. Results Eng. 26, 105391 (2025).

Alom, N., Kolaparthi, S. C., Gadde, S. C. & Saha, U. K. Aerodynamic Design Optimization of elliptical-bladed Savonius-style Wind Turbine by Numerical Simulations Vol. 6 (Ocean Space Utilization; Ocean Renewable Energy (American Society of Mechanical Engineers, 2016).

Ghafoorian, F., Mirmotahari, S. R. & Wan, H. Numerical study on aerodynamic performance improvement and efficiency enhancement of the Savonius vertical axis wind turbine with semi-directional airfoil guide Vane. Ocean Eng. 307, 118186 (2024).

Akhlaghi, M., Mirmotahari, S. R., Ghafoorian, F. & Mehrpooya, M. Numerical study of control rod’s cross-section effects on the aerodynamic performance of Savonius vertical axis wind turbine with various installation positions at Suction side. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Mech. Eng. 48, 2143–2165 (2024).

Afify, R., Saber, E. & Awad, H. Investigation of an innovative Savonius turbine in practice. Sci. Rep. 15, 6937 (2025).

Alom, N. & Saha, U. K. Influence of blade profiles on Savonius rotor performance. Numerical simulation and experimental validation. Energy Convers. Manag. 186, 267–277 (2019).

Chan, C. M., Bai, H. L. & He, D. Q. Blade shape optimization of the Savonius wind turbine using a genetic algorithm. Appl. Energy. 213, 148–157 (2018).

Sharma, S. & Sharma, R. K. Performance improvement of Savonius rotor using multiple quarter blades – A CFD investigation. Energy Convers. Manag. 127, 43-54 (2016).

Jacob, J. & Chatterjee, D. Design methodology of hybrid turbine towards better extraction of wind energy. Renew. Energy 131, 625-643 (2019).

Ferrari, G., Federici, D., Schito, P., Inzoli, F. & Mereu, R. CFD study of Savonius wind turbine: 3D model validation and parametric analysis. Renew. Energy 105, 722-734 (2017).

Zemamou, M., Aggour, M. & Toumi, A. Review of Savonius wind turbine design and performance. Energy Procedia 141, 383-388 (2017).

Gonçalves, A. N. C., Pereira, J. M. C. & Sousa, J. M. M. Passive control of dynamic stall in a H-Darrieus vertical axis wind turbine using blade leading-edge protuberances. Appl. Energy. 324, 119700 (2022).

Wong, K. H., Lee, K. Y., Ng, J. H., Wang, X. H. & Fazlizan, A. The effects of inertia on a straight-bladed vertical axis wind turbine. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 1500, 012005 (2025).

Abdallah, A., William, M. A., Moharram, N. A. & Zidane, I. F. Boosting H-Darrieus vertical axis wind turbine performance: A CFD investigation of J-Blade aerodynamics. Results Eng. 27, 106358 (2025).

Ntantis, E. L. & Xezonakis, V. Improving transonic performance with adjoint-based NACA 0012 airfoil design optimization. Results Eng. 24, 103189 (2024).

Farajyar, S., Ghafoorian, F., Mehrpooya, M. & Asadbeigi, M. C. F. D. Investigation and optimization on the aerodynamic performance of a Savonius vertical axis wind turbine and its installation in a hybrid power supply system: A case study in Iran. Sustainability 15, 5318 (2023).

Soroush, H., Nourani, A. & Farrahi, G. A machine learning model to predict fracture of solder joints considering geometrical and environmental factors. Theoret. Appl. Fract. Mech. 136, 104865 (2025).

Golmohammadi, A., Soroush, H. & Khodaygan, S. A machine learning-based model to predict residual stress in aluminum shell formed by shot peening. Int. J. Solids Struct. 313, 113250 (2025).

Abdolahi, A., Soroush, H. & Khodaygan, S. Process capability analysis of additive manufacturing process: a machine learning-based predictive model. Rapid Prototyp. J. 31, 724–741 (2025).

Tavoosi, S. N., Hoseinian, S. M. A. & Shamloo, A. Developing a droplet-based microfluidic device for CTC single-cell encapsulation and downstream molecular analysis. In 2023 30th National and 8th International Iranian Conference on Biomedical Engineering (ICBME), 52–58 (IEEE, 2023).

Ebrahimi, S., Rostami, Z., Alishiri, M., Shamloo, A. & Hoseinian, S. M. A. Magnetic sorting of Circulating tumor cells based on different-level antibody expression using a divergent serpentine microchannel. Phys. Fluids 35 (12), 121906 (2023).

Mahdavi, F. et al. Design and fabrication of multiplex microfluidic LAMP PCR for simultaneous detection of opportunistic protozoa. Sens. Biosensing Res. 48, 100787 (2025).

Ranjbar, M., Mostafavi, A., Rajendran, P. T., Komperda, J. & Mashayek, F. Modal analysis of turbulent flows simulated with spectral element method. Phys. Fluids 36 (12), 125164 (2024).

Mostafavi, A., Ranjbar, M., Yurkiv, V., Yarin, A. L. & Mashayek, F. On the energy analysis of two-phase flows simulated with the diffuse interface method. Phys. Fluids 37 (7), 072125 (2025).

Zhou, T. & Rempfer, D. Numerical study of detailed flow field and performance of Savonius wind turbines. Renew. Energy 51, 373-381 (2013).

Roy, S. & Ducoin, A. Unsteady analysis on the instantaneous forces and moment arms acting on a novel Savonius-style wind turbine. Energy Convers. Manag 121, 281-296 (2016).

Akwa, J. V., Vielmo, H. A. & Petry, A. P. A review on the performance of Savonius wind turbines. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 16, 3054–3064 (2012).

Mostafavi, A., Ranjbar, M., Yurkiv, V., Yarin, A. L. & Mashayek, F. MOOSE-based finite element framework for mass-conserving two-phase flow simulations on adaptive grids using the diffuse interface approach and a Lagrange multiplier. J. Comput. Phys. 527, 113755 (2025).

Kumar, A. & Saini, R. P. Performance analysis of a Savonius hydrokinetic turbine having twisted blades. Renew. Energy 108, 502-522 (2017).

Sørensen, J. N. & Okulov, V. Ramos-García, N. Analytical and numerical solutions to classical rotor designs. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 130, 100793 (2022).

ANSYS CFX-Solver Theory Guide. (2009). http://www.ansys.com

Coughtrie, A. R., Borman, D. J. & Sleigh, P. A. Effects of turbulence modelling on prediction of flow characteristics in a bench-scale anaerobic gas-lift digester. Bioresour Technol. 138, 297–306 (2013).

Blazek, J. & Elsevier Computational Fluid Dynamics: Principles and Applications. ( (2005). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-044506-9.X5000-0

Dragomirescu, A. Performance assessment of a small wind turbine with crossflow runner by numerical simulations. Renew. Energy. 36, 957–965 (2011).

Pope, K., Dincer, I. & Naterer, G. F. Energy and exergy efficiency comparison of horizontal and vertical axis wind turbines. Renew. Energy. 35, 2102–2113 (2010).

Alom, N. & Saha, U. K. Examining the aerodynamic drag and lift characteristics of a newly developed elliptical-bladed Savonius rotor. J. Energy Resour. Technol. 141 (5), 051201 (2019).

Mohamed, M. S. et al. Design Optimization of Savonius and Wells Turbines (2011).

Hassan Saeed, H. A., Nagib Elmekawy, A. M. & Kassab, S. Z. Numerical study of improving Savonius turbine power coefficient by various blade shapes. Alexandria Eng. J. 58, 429–441 (2019).

Roy, S. & Saha, U. K. Wind tunnel experiments of a newly developed two-bladed Savonius-style wind turbine. Appl. Energy. 137, 117–125 (2015).

Sharma, S. & Sharma, R. K. CFD investigation to quantify the effect of layered multiple miniature blades on the performance of Savonius rotor. Energy Convers. Manag. 144, 275–285 (2017).

Akwa, J. V., Alves da Silva Júnior, G. & Petry, A. P. Discussion on the verification of the overlap ratio influence on performance coefficients of a Savonius wind rotor using computational fluid dynamics. Renew. Energy. 38, 141–149 (2012).

Masdari, M., Tahani, M., Naderi, M. H. & Babayan, N. Optimization of airfoil based Savonius wind turbine using coupled discrete vortex method and salp swarm algorithm. J. Clean. Prod. 222, 47–56 (2019).

Abbasi, S. & Daraee, M. A. Ameliorating a vertical axis wind turbine performance utilizing a time-varying force plasma actuator. Sci. Rep. 14, 18425 (2024).

Michna, J. & Rogowski, K. CFD calculations of average flow parameters around the rotor of a Savonius wind turbine. Energies (Basel). 16, 281 (2022).

Blazek, J. Computational Fluid Dynamics: Principles and Applications (Elsevier, 2005).

Schlichting, H. & Gersten, K. Boundary-Layer Theoryspringer,. (2016).

(Numerical Computation of Internal and External Flows & Elsevier (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7506-6594-0.X5037-1

Ghafoorian, F., Mirmotahari, S. R., Eydizadeh, M. & Mehrpooya, M. A systematic investigation on the hybrid darrieus-savonius vertical axis wind turbine aerodynamic performance and self-starting capability improvement by installing a curtain. Next Energy 6, 100203 (2025).

Zamre, P. & Lutz, T. Computational-fluid-dynamics analysis of a Darrieus vertical-axis wind turbine installation on the rooftop of buildings under turbulent-inflow conditions. Wind Energy Sci. 7, 1661–1677 (2022).

Abdolahifar, A. & Zanj, A. Addressing VAWT aerodynamic challenges as the key to unlocking their potential in the wind energy sector. Energies 2024. 17, 5052 (2024).

Seifi Davari, H., Seify Davari, M., Botez, R. M. & Chowdhury, H. Advancements in vertical axis wind turbine technologies: a comprehensive review. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 50, 2169–2216 (2025).

Marinić-Kragić, I., Vučina, D. & Milas, Z. Computational analysis of Savonius wind turbine modifications including novel scooplet-based design attained via smart numerical optimization. J. Clean. Prod. 262, 121310 (2020).

Eltayeb, W. A. & Somlal, J. Performance enhancement of Darrieus wind turbines using plain flap and gurney flap configurations: A CFD analysis. Results Eng. 24, 103400 (2024).

Seifi Davari, H., Botez, R. M., Davari, S., Chowdhury, M., Hosseinzadeh, H. & H. & Numerical and experimental investigation of Darrieus vertical axis wind turbines to enhance self-starting at low wind speeds. Results Eng. 24, 103240 (2024).

Seifi Davari, H., Kouravand, S., Seify Davari, M. & Kamalnejad, Z. Numerical investigation and aerodynamic simulation of Darrieus H-rotor wind turbine at low Reynolds numbers. Energy Sour. Part A Recover. Utilization Environ. Eff. 45, 6813–6833 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Seyed Mohammadali Hosseinian contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, software development, data analysis, and writing of the original draft. Mohsen Mohseni was involved in the methodology, validation, visualization, and the review and editing of the manuscript. Mohammad Sadegh Karimi provided supervision and participated in the review and editing process. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hosseinian, S.M., Mohseni, M. & Karimi, M.S. Advanced blade profiles for improved efficiency in Savonius wind turbines: the aeroleaf case study. Sci Rep 16, 1022 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30636-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30636-8