Abstract

The rapid development of deep learning (DL) is the most significant contemporary evolution of hydrological science, yet its limitations remain underexplored. This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of DL-based, traditional, and hybrid hydrological models in streamflow simulation especially in data-deficient regions. Daily discharge flow of the four sub-catchments in Samar, Philippines were modeled using HEC-HMS, Univariate Long-Short Term Memory (LSTM) Network, Classical GR4J and DL-assisted, parametrically- optimized GR4J. Results show that the classical GR4J underestimated the discharge, while the LSTM overestimated peaks. The DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J achieved the highest consistency and balance between realistic peak and low flow estimation, with NSE = 0.63–0.84, IA = 0.85–0.93, LMI = 0.76–0.82, and low MAPE (≤ 0.03) and RSR (≤ 0.02). Although the Univariate LSTM captured general trends well, it underestimated some peaks despite reaching high values in performance metrics. Many studies highlight DL’s hydrological modeling power but ignore its limits and hybrid model benefits. The results highlight that neither DL nor classical models alone are sufficient as DL-assisted approaches yield more reliable and realistic hydrological simulations, particularly in climate-sensitive, data-deficient regions like Samar.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Several studies have used deep learning for hydrological models. A model using LSTM was proposed by Yang et al.1 to increase the effectiveness of the flood models using mean daily precipitation, wind, temperature, and runoff data, they calculated a model-simulated discharge from the Global Hydrological Model GHMs + CaMa-Flood between 1971 and 2010. Nguyen and Bae2 proposed an LSTM network utilizing the Quantitative Precipitation Forecasts of MAPLE or McGill Algorithm for Precipitation Nowcasting by Lagrangian Extrapolation. Han et al.3 used LSTM-based sequence-to-sequence model in discharge simulation. Using data from Environment Canada, Atieh et al.4 presented a neural network model with new input parameter that captures the temporal and spatial variability of rainfall to predict flow-duration curves.

Mohammadi et al.5 employed a combination of hydrological models, including IHACRES, GR4J, and MISD, in series with Support Vector Machines (SVM), incorporating a comprehensive set of hydrological variables such as temperature, precipitation, evapotranspiration, relative humidity, and snow depth. In contrast, Kumanlioglu and Fistikoglu6 utilized GR4J in conjunction with Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) and a Genetic Algorithm, relying solely on evaporation and rainfall data. Similarly, Humphrey et al.7 adopted a Bayesian ANN approach alongside the GR4J model, also limiting their input to evaporation and precipitation variables.

Hybrid modeling, particularly approaches that combine classical hydrological models with deep learning, has emerged as a leading trend due to its demonstrated effectiveness in capturing complex hydrological dynamics. Kapoor et al.8 employed Taken’s Theorem to reconstruct variable features from the GR4J model before applying deep learning methods such as LSTM and CNN, effectively replacing the routing storage process and achieving improved performance over classical GR4J. Chen et al.9 utilized a data-rich watershed, combining seven SWAT-simulated variables with five meteorological variables (PCP, TEMP, RH, WS, and SR) to create a 12-variable input set for LSTM-based modeling. Cho and Kim10 focused on residual modeling using LSTM and incorporated the predicted outputs into WRF-Hydro simulations. Kim et al.11 adopted a hybrid approach by using physically based models for upstream watershed simulation and LSTM-based deep learning for dam operation modeling. Yang et al.12, working in a data-scarce glacial region, decomposed input features into trend, seasonality, and residual components and used these to model streamflow and bias errors. Lastly, Zhang et al.13 compared default, partially calibrated, and land-use-informed SWAT models to build hybrid models.

This study differs from the aforementioned studies in several key aspects. The proposed DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J model is unique in that it retains GR4J as the foundational hydrological model while integrating deep learning-derived inputs, namely, LSTM-predicted rainfall and causality-based evapotranspiration, into the simulation. Furthermore, the model employs a random optimization approach using the Legates-McCabe Index (LMI), which was not used in any of the referenced studies. While earlier works typically follow patterns such as: (1) classical model + state space reconstruction then DL8; (2) SWAT-modeled features as DL inputs9; (3) residual modeling using DL10; (4) independent classical and DL model combinations11; (5) decomposed components in DL12; or (6) land use-informed SWAT calibration models13, our approach maintains a single-process backbone (GR4J) while enhancing it with DL and causality-informed variables and an LMI-based parameter optimization technique.

All these studies show that some hydrological models may be represented by deep learning models as a substitute however, none have used a DL-assisted approach (particularly using GR4J) where separate models of rainfall and causality-based evapotranspiration were made while using a random optimization approach based on Legates-McCabes Index (LMI). This is significant because it combines the physical interpretability of traditional models with the predictive power of DL, which is still a relatively underexplored strategy.

The rapid development of deep learning (DL) is a significant contemporary evolution of hydrological science. Applying DL techniques is necessary to handle the expanding amount of information and concerns like climatic change and a growing environmental effect of humans. It is clear why DL has received so much interest given that the majority of research uses DL models for modeling or categorization. Context-based hydrology14, forecasting of urban water demand15, classifying storms for flood warnings16, and simulation of stream runoff17,18,19 are some examples of its hydrological applications. Koch and Schneider20, on the other hand, emphasized the enormous capability of DL models in simulating rainfall and runoff relationship particularly when used with ungauged basins. DL models are known to perform more accurately in modeling than other traditional statistical regression-based models21,22,23,24,25.

However, only few scientists have pointed out the disadvantages of DL in hydrology. Shen et al.26 have pointed out that DL cannot distinguish between causal or associative relationships. Sit et al.27 said that DL affects human decision-making context while Shen et al.28 emphasized that DL does not represent contextual variables or heterogenous physiographic factors, arguing that hydrological systems do not align well with standard network structures. Another is that DL needs large sample size and that training data can be sometimes unstable29.

In this era of data science where classical hydrological models have not set a higher reputation against machine learning (ML)30,31, the use of the latter (ML) for hydrological system modelling and analysis is rapidly gaining popularity.

In fact, Nearing et al.32 raised the issue asking the hydrological science community to work on a quantitative approach for a better translated theoretical hydrological modeling in his commentary “What Role Does Hydrological Science Play in the Age of Machine Learning?”.

Many scientists have tried to assess the differences as well as the advantages or disadvantages of using ML with some emphasis on deep learning (DL) over classical hydrological models. Sezen et al.33 concluded that Génie Rural à 4 paramètres Journalier better known as GR4J, a lumped conceptual model, generally performed better especially in modeling non-karst catchments compared to the other ML methods he used. On the other hand, Sit et al.27 have highlighted the potential of deep learning as a means to transform hydrological science especially in predicting and forecasting while Shen et al.28 have concluded that integrating DL to the hydrological science workbench could lead to innovative hydrological modeling approaches.

However, there are a handful of scientists who expressed their concerns and raised questions as to whether the future will need classical hydrological models 32. Kwak et al.34 pointed out that it is hard to completely replace the hydrological models with deep learning technique and concluded that combining the runoff of the hydrological model with the runoff simulation of the residuals (using DL) will give better results.

There are a lot of deep learning models used for hydrological modeling. In fact, Kim et al.35 used both data-driven machine learning models and process-based hydrological models to find out which type could perform better. His findings indicate that the data-driven machine learning models are better performing than process-based hydrological models in high-flows. In data-constrained basins, Ghimire et al.36 pointed out that among the other lumped hydrological models they tested, GR4J showed to be particularly effective for daily flow simulations.

In this study, we modeled four (4) sub-catchments using DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J as the hydrological model as a response to the Question 20 of Blöschl et al.37 in his paper, “Twenty-three unsolved problems in hydrology (UPH) – a community perspective.” Question 20 asks, “How can we disentangle and reduce model structural/parameter/input uncertainty in hydrological prediction?”.

In his paper, Demirel et al.38 have emphasized the disadvantage of using the classical GR4J. He pointed out how GR4J output produces higher uncertainty in the discharge forecasts which could lead to increased number of false alarms especially in catchments with low flows. Thus, it can be said that classical models like GR4J can sometimes produce unreliable discharge or runoff simulation which could lead to mismanaged water resources. In today’s fast-paced environment, a need to improve these classical models is essential. This is why the authors would like to propose methods to enhance GR4J by using DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J.

Materials and methods

Hydrological models

There are hydrological models that vary in nature, complexity, and use. In order to simulate how precipitation changes into runoff, hydrological models have been created.

To simulate the hydrological processes in dendritic watershed systems, the Hydrologic Engineering Center-Hydrologic Modeling System (HEC-HMS) was created. Because of the way the program is developed, it may be used to solve a variety of issues, from minor urban or natural watershed runoff to major river basin water supply and flood hydrology. By dividing the hydrologic cycle into manageable components and drawing borders around the watershed of interest, a model of the watershed is created. Every water channel or energy input in the hydrologic cycle may often be represented by a number of different models and mathematical model (as part of HEC-HMS) is applicable in various settings and under various circumstances. According to Scharffenberg et al.39, HEC-HMS is a conceptual but physically-based hydrological model. Developed by the US Army Corps of Engineers in 1998, HEC-HMS is a reliable model for simulating hydrological processes in basin systems.

To understand and quantify the effects of changing land use on stream flows, hydrologic models are frequently utilized. They also give data that may be used to advise decisions about land use. Due to the many factors involved, modeling the hydrological connection may be difficult and time intensive depending on the type of model. Table 1 shows the description and classification as well as the summarized comparison of hydrological models based on its classification.

As shown, GR4J, the main hydrological model of this study falls under the conceptual hydrological model while DL falls under the empirical hydrological model. Due to better evaluation claims from different model types as well as hydrological modeling trends, the authors used DL and GR4J as focus of this study.

GR4J model

The Modèle du Génie Rural à 4 paramètres Journalier which is also known as the GR4J hydrological model is a daily lumped rainfall-runoff model developed by Perrin et al.40. This model has been found to be more efficient and gives excellent modeling results compared to Tank models, IHACRES, HBV, SMAR, TOPMODEL, Xinanjiang and others40. GR4J is based on soil moisture accounting approach and is the latest modification of the GR3J model, which was first developed in 199941. Unlike the GR3J, the GR4J model includes a percolation function which is incorporated in the production storage component. The two main components of GR4J are rainfall and evapotranspiration, which is consistent with findings from other studies. For instance, Rossi et al.42 reported that in Puerto Rico, rainfall and evapotranspiration significantly influence runoff variability.

Considering zero-amplitude intercept storage, to determine either the net precipitation (Pn) or the net evaporation amplitude (En), the GR4J model first deducts the potential evaporation (E) from the precipitation (P). If the acquired Pn is different from zero, some Ps (rainfall that goes directly to production storage) will be used to fill the production storage of the upper soil profile as a function of the water content of that storage (S). Otherwise, if En is different from zero, the actual evaporation rate (Es) is calculated as a function of the water content of the production storage.

Upon calculating the new water content in the production store, a percolation (or infiltration) leakage (Perc) is calculated as a power function of the water content in the storage. The remaining net rainfall which is not utilized for the production storage together with the Perc (or percolated water), Pn – Ps are split into two flow components: 90% is routed using a unit hydrograph (UH1) followed by a non-linear routing storage, and the remaining 10% is routed using single unit hydrograph UH2. The two unit hydrographs UH1 and UH2 will be used to calculate the time lag between the rainfall event and the peak of the river flow. The last step includes summing up the two routed flow components. Table 2 shows the parameters of GR4J.

The following are the formulas and definitions of the GR4J parameters (t = timestep):

For production store:

Percolation leakage is calculated as:

The inflow will split into two components using unit hydrographs (UH1 and UH2). These two components, together with runoff, will be calculated using the following formulas:

where

According to Perrin et al.40, Table 3 shows the GR4J median value parameters and its 80% confidence intervals:

Random optimization algorithm

Random Optimization Algorithm (ROA) is sometimes referred to as a black-box technique since it does not require derivatives but typically, direct search. Bardossy and Singh43 have concluded that one of the robust estimation methods for parameter optimization in hydrological models is by calculation with respect to the performance indicators. Zakouni et al.44 have used ROA and found that in small network nodes, ROA performs better than Genetic Algorithm (GA). In the study of Kashiwao et al.45, they developed and tested a rainfall prediction system in Japan using neural networks where random optimization (RO) was also utilized. Huang et al.46 used ROA for optimal production scheduling and emphasized that the method significantly improved the production performance. Figure 1 shows how ROA works.

There are two components in establishing a GR4J model for a catchment. One is evapotranspiration and the other is precipitation. In this study, the authors used deep learning to model both precipitation and evapotranspiration of the GR4J model.

This paper used HEC-HMS to model the discharge flow of the sub-catchments (S7, S-8, S-9 and S-10) hereafter referred to as the “HEC-HMS discharge flow.” The simulated flow (the discharge generated from the DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J) was then compared to the HEC-HMS discharge flow by calculating several metrics of evaluation: correlation coefficient (CC), Nash–Sutcliffe efficiency (NSE), Kling-Gupta efficiency (KGE), index of agreement (IA), Legates-McCabe index (LMI), mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), percent (%) bias (PBIAS) and RMSE-observations standard deviation ratio (RSR).

Study area and data used

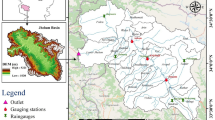

The analysis utilized daily rainfall and evapotranspiration data from four sub-catchments (see Fig. 2) in Eastern Samar, Philippines: S-7 (Oras), S-8 (Dolores), S-9 (Can-avid), and S-10 (Catubig), covering various date ranges between 2013 and 2018 (Table 4)47. These datasets were sourced from local hydrometeorological stations, with daily records ranging from approximately 1,000 to over 2,100 entries per station.

Four sub-catchments in Samar, Philippines used in this study. (The work is adapted and used under CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.en) edited using original figures from (Necesito et al., 2023) 47).

The data used in this study include the rainfall amount obtained from the DWT + Univariate-LSTM model47 and the evapotranspiration model obtained from the NARX model48. The parameter values for the DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J hydrological model were obtained using LMI-based Random Optimization Algorithm (ROA).

Rainfall data (in mm/day) demonstrated considerable spatial variability, with mean values ranging from 0.37 mm (S-7) to 3.18 mm (S-8), and maximum values reaching as high as 91.00 mm (S-8), suggesting extreme precipitation events (Table 5)47. The data had medians lower than the means and several days recording no rainfall.

Observed evapotranspiration values were more consistent across stations, with daily means around 5.74 mm/day and minimal variability (standard deviations ~ 0.39), suggesting a relatively uniform atmospheric demand over the study area (Table 6)48.

Overview of the process

Figure 3 shows the schematic diagram of the methodology used in the DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J model. As shown in Fig. 3, the DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J model starts with two (2) main inputs: rainfall and evapotranspiration. These inputs were modeled using DL techniques (DWT + LSTM and NARX) in a separate study47,48. Thus, for the LSTM model (rainfall), the model consists of one input layer and uses the Adam optimizer with a maximum of 400 epochs. The activation function employed is the rectified linear unit (ReLU). The time series data were divided into training and testing sets, with 70% allocated for training and 30% for testing. The model was implemented using Python’s Keras library (v2.11.0), which serves as an interface for TensorFlow47. For the NARX model (evapotranspiration), A Random Forest Regressor (RFR) was used as the base model, constructing multiple decision trees to identify the most optimal predictor for the NARX model. Implementation was performed using the fireTS module in Python. The dataset was split into 70% for training and 30% for testing48.

On the other hand, for the Univariate LSTM model, the model includes a single LSTM layer with ReLU activation, followed by a single output layer. It was compiled using the Adam optimizer and trained for 400 epochs with a batch size of 20. The dataset was split into 70% for training and 30% for testing.

The authors used the formulas from Perrin et al.40 and ROA for estimating the four (4) main parameters of GR4J namely: production store (X1), groundwater exchange coefficient (X2), one-day-ahead capacity of the routing store (X3), and time base of the unit hydrograph (X4) of the four sub-catchments (S7, S-8, S-9 and S-10). This current study used deep learning in combination with ROA to enhance the GR4J model.

Parameter optimization by random optimization algorithm

The following is the ROA algorithm used in this study:

Step 1: Initialize the needed variables: rainfall, evapotranspiration and area of catchment.

Step 2: Obtain a random value for the parameters in the set of range values for X1, X2, X3 and X4.

Step 3: Perform the hydrological calculation using the formulas from Perrin et al.40.

Step 4: If the termination criterion such as the chosen minimum for performance indicators, say, 0.5 for LMI is not obtained, repeat Steps 2 and 3.

In this study, the authors used ROA to obtain the optimal X1, X2, X3 and X4. Legates-McCabes Index (LMI) below is used as the constraint for optimization.

In the equation above, n represents the number of data, \({Y}_{i}\) represents the observed values, \({X}_{i}\) for the simulated values and \({\mu }_{y}\) as the mean of the observed values.

Results and discussion

Discharge simulation by deep learning (DL)-assisted GR4J model

Table 7 shows the results of evaluating the HEC-HMS discharge and the DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J simulated discharge flow.

As shown in Table 7, only two sub-catchments (S-8 and S-9) have shown satisfactory results. The sub-catchments which showed satisfying performance for the DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J model are only S-8 and S-9. Other sub-catchments like S-7 and S-10 have low performance indicators which imply that the model was not able to properly simulate the sub-catchments’ daily discharge flow based on the HEC-HMS results.

Based on the findings of Necesito et al.47 and Necesito et al.48, the simulated rainfall and evapotranspiration, which are the main input values of the DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J, DL was proven to have the capability to model and predict the components or input values. But regardless of that capability, the DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J was still not able to model the actual HEC-HMS discharge flow of the other sub-catchments (S-7 and S-10).

In this section of the paper, the authors would also like to examine thoroughly the possible issues of using DL in the field of hydrology. The authors note that most studies emphasize the strengths of DL in modeling hydrological components but often overlook the limitations of using DL alone and the potential advantages of hybrid approaches that combine DL with classical, parametrically-optimized hydrological models.

Scrutinizing the four (4) parameters of the DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J in < Table 8 > namely the capacity of the production store (X1), groundwater exchange coefficient (X2), one day ahead capacity of the routing store (X3), and time base of the unit hydrograph (X4) of the four sub-catchments (S7, S-8, S-9 and S-10), it was S-8 and S-9 which showed the highest performance indicators among the four (4). This strong performance is notable and meaningful for several reasons.

First, S-8 and S-9 also have the same X1 and X2 parameter and a difference of one (1) in the X4 parameter. According to Feigl et al.49 and Oueldkaddour et al.50, X1 is the most sensitive parameter of GR4J while Andréassian et al.51, Wang et al.52 and Nemri and Kinnard53 said that X2 is the most sensitive parameter. On the other hand, Wanzala et al.54 claimed that both X1 and X2 are both sensitive.

Looking at the other sub-catchments (S-7 and S-10), the values of X1 and X2 are far from the values obtained by S-8 and S-9. S-7 has X1 value of 633 compared to S-8’s and S-9’s X1 value of 3. X2, which was also claimed as a “sensitive parameter” by Andréassian et al.51, Wang et al.52 and Nemri & Kinnard53, have 2 (for S-8 and S-9) and 1 (for both S-7 and S-10).

As claimed by Flores et al.55, X2 and X3 are the most sensitive. S-8 and S-9, which showed very high performance values, X2 are both 2.0 and X3 values are 23.0 and 36.0 respectively, while S-7 and S-10 values are 8.0 and 4.0 respectively and X2, on the other hand, are 1.0 and 1.0, respectively.

Looking at this pattern of values, it can be said that either X1 or X2 could be the most sensitive since both S-8 and S-9 have the same values of X1 and X2 but different values of X3 and X4. The authors believe that X4 is likely not the most sensitive, as evidenced by the fact that even though S-10 shares the same X4 value as S-9, its performance metrics remain poor. In contrast, S-10’s X3 value significantly deviates from those of S-8 and S-9, both of which exhibit better performance. S-10 is more comparable to the X3 values of S-7, which also show poor performance. This suggests that X3 may have a greater influence on the outcome and could explain why S-10, like S-7, performs poorly. It can also be worth mentioning that the authors applied the parameter values of S-8 and S-9 to the poor performing sub-catchments (S-7 and S-10) but the performance indicators still remained poor.

Graphically shown in Fig. 4 as well as in Table 7 for performance indicators, the DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J models for S-8 and S-9 have modeled significant peaks and lows of the HEC-HMS discharge flows. However, the other sub-catchments (S-7 and S-10) which have shown low model performance are also showing unsynchronized daily flows.

For example, in S-8, peak flows on May 21, 2018 at 559.08 m3/s in the DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J model corresponds to the peak flows obtained in the conventional HEC-HMS, which is 680.4 m3/s while low flows corresponding to August 24, 2018 to September 15, 2018 and October 1 to October 29, 2018, for example, were also captured by the DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J.

Scrutinizing the other sub-catchments (S-7 and S-10), both low flows and high flows were not properly simulated by the DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J. In S-7, the DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J showed poor model fit. In fact, the DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J simulated a constant daily flow when the HEC-HMS discharge flow has alternating peak and low flows on the same data range. S-10 is similar to S-7, capturing only an almost constant value of less than 10 m3/s.

To compare the pure DL technique with the DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J, a Univariate LSTM model of the discharge flow was developed (see Fig. 5).

This study has shown that despite the high applicability and satisfactory performance of DL to predict the independent variables in certain hydrological models, there is still a tendency to yield inaccurate hydrological estimates. In the DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J model approach done in this study, it was found that there are certain sub-catchments which were satisfactorily modeled (S-8 and S-9) based on the discharge output. However, there are also sub-catchments which were inappropriately modeled (S-7 and S-10).

To assess and understand more the model outcomes, the authors simulated the discharge value using Univariate-LSTM for the four (4) sub-catchments. As shown in Fig. 5, the Univariate-LSTM has once again shown its ability to predict the high and low peaks of a discharge flow time series. However, we can also see in Fig. 5 that in comparison to the HEC-HMS discharge (blue curves), Univariate-LSTM has much lower peak discharge values. Examining Fig. 4 for S-8 and S-9, the DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J captured each high and low with estimations higher than the actual value which results in conservative predictions. On the other hand, using Univariate-LSTM might result in more economic engineering estimations since it has lower estimated peak discharge values.

While the potential of DL techniques to fully replace classical hydrological models remains a subject of interest, it can be concluded that DL alone faces significant challenges in accurately predicting hydrological variables. Based on the findings of this study, the effectiveness of the model will be higher when DL is supplemented with classical hydrological models. This will enhance the likelihood of obtaining higher peak estimates, which, although less cost-efficient, provide safer flood design margins.

With these results, we can conclude the importance of doing DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized models and that, at times, neither the DL nor the classical model alone is sufficient to make hydrological models. There are also some considerations regarding characteristics of the study area which might be another contributing factor why other sub-catchments (S-7 and S-10) were inappropriately modeled by the DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J.

Other possibilities would include inappropriate parameters for certain basins, and that there is a certain range of mean values for inputs like rainfall and evapotranspiration in order for the DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J to function properly. This gives us an idea that GR4J cannot be ideally used when the datasets have small amounts of rainfall recorded. This could mean that low-intensity rainfall events or even rainfall events with small standard deviations are not suitable for GR4J. In this case, an alternative can be a DL technique such as the Univariate LSTM.

In Table 5, S-8 and S-9 have precipitation mean values of 3.18 mm and 1.44 mm respectively, while S-7 and S-10 have precipitation values ranging from 0.37 mm to 0.58 mm. All sub-catchments have 0.0 as the minimum precipitation value and maximum precipitation values of 91.0 mm and 71.5 mm for S-8 and S-9, respectively, while S-7 and S-10 have 14.0 mm to 22.4 mm as maximum value. The standard deviations of the sub-catchments also tell us that S-7 and S-10 have low values. In studies where GR4J was utilized5,56,57, the study areas have high precipitation mean values (with value range like that of S-8 and S-9). Shin and Kim58 emphasized that the amount of rainfall and the type of basin also determines the applicability of the GR4J, that is, it cannot adequately simulate a dry catchment. Poor model performance in dry or arid areas is commonly reported59,60.

On the other hand, the Philippines’ Department of Agriculture – Bureau of Soils and Water Management (https://www.bswm.da.gov.ph) show the location of each sub-catchment with its corresponding pH values (see https://www.bswm.da.gov.ph/map/eastern-samar-soil-ph-rice-201808/ and https://www.bswm.da.gov.ph/map/northern-samar-soil-ph-rice-201710/). S-10 showed moderately acidic to strongly acidic. S-7 has nearly neutral, and has minimal areas with strong and very strong acidity which all indicate that they are subjected to less flooding. S-8 show moderately acid, strongly acid, very strongly acid and extremely acid parts while S-9 has moderately acid, strongly acid and very strongly acid parts. Looking at Table 8 the value of X1 or the capacity of the production soil store or simply moisture capacity is very low at both S-8 and S-9. In fact, the value is 3 only, which is very low compared to the other sub-catchments. This means that S-8 and S-9 have a very low capacity to absorb water. This supports the argument of Kozlowski & Pallardy61 when they pointed out that flooding can increase the pH level of acidic soils because it tends to change the Fe3+ and Fe2+. Thus, sub-catchments S-8 and S-9 are acidic enough and are subjected to frequent flooding causing a low X1 value.

The low \({X}_{1}\) values observed in S-8 and S-9 may be attributed to the presence of highly acidic and low water-holding capacity soils in these areas, which typically exhibit poor soil fertility and limited storage potential62. These soil characteristics can reduce the available soil moisture and storage parameter \({X}_{1}\). In addition, the relatively higher \({X}_{3}\) values of S-8 and S-9 compared to S-7 and S-10 suggest greater permeability and groundwater exchange, consistent with sandy-textured soils. Sandy soils generally exhibit lower storage capacity but higher infiltration and transmission properties. As supporting regional context, cassava, commonly cultivated in these sub-catchments63, is known to tolerate and even thrive in such sandy and acidic soils64,65. This aligns qualitatively with the observed hydrological behavior, though quantitative field validation (e.g., soil texture, pH, or infiltration measurements) would further substantiate this inference.

Looking at X3 of the sub-catchments, S-8 and S-9 have oddly higher value compared to S-7 and S-10. By formula for the nonlinear routing store, the lower the routing reservoir capacity, the higher the groundwater exchange, F. Since S-8 and S-9 have higher values than S-7 and S-10, this could mean that it has higher permeability which is a property of sandy-like soils. According to USDA NRCS National Plant Data Center66, cassava grows best in sandy-like soils.

Looking at the parameter values, modeling performance and how the simulated discharge flow behaved in the given time range of each sub-catchment, it suggests that:

-

Area size and modeling performance are unrelated. This is in contrast to the findings of Lavtar et al.67 who concluded that larger catchments correlate with improved modeling performance.

-

Certain parameter value range of the DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J can be applied to certain basins. This could mean that the range of X1, X2, X3, and X4 have ideal basins of application.

-

The time range is irrelevant to the model performance. The time range of S-8 and S-9 are less than or equal to 1 year. However, the authors tried to change the time range of S-7 and S-10 to less than or equal to 1 year, the results of the DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J in terms of metric evaluation is still poor. Thus, changing the time range of simulation, even using the same time range as that of S-8 and S-9, is unrelated to DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J performance.

-

High rainfall amount or high runoff tendencies can lead to improved model performance. This means that small rainfall events or rainfall events with small standard deviations are not suitable for DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J.

-

DL alone can lead to peak discharges but with lower estimated values compared to the HEC-HMS discharge values. The authors also tried using the classical GR4J in fusion with ROA for S-8 and S-9 (see Fig. 6) which led to a very poor model. On the other hand, using a DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J or a hydrological model composed of DL + ROA + GR4J can lead to better discharge models (Fig. 4) for certain sub-catchments like S-8 and S-9 where prior satisfactory conditions mentioned are present (e.g. high rainfall or high runoff tendencies).

The reasons behind the inapplicability of the DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J hydrological model to S-7 and S-10 can be a subject for future study which can also lead in ways to improve the DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J.

Looking at the Figs. 7, 8 and 9, where the focused sub-catchments are S-8 and S-9, we can see the synchronized peaks and lows of both rainfall and discharge values from DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J and Univariate LSTM with respect to the discharge flow modeled by HEC-HMS. However, the peak value estimations for discharge flow are somehow different. In this study, we used the classical GR4J model and it showed that classical GR4J is less efficient than the Univariate LSTM. The DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J, on the other hand, has showcased its ability to properly estimate the peak values better than the classical GR4J. Even though the Univariate LSTM showcased a better trend, some peak values are still adequately captured by the DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J (see Fig. 10).

In this study, the classical GR4J showed very low values while the Univariate LSTM overestimated the discharge flow. The DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J has outperformed the classical GR4J both in trend and in estimating the peak discharge flows. Univariate LSTM model has shown the best discharge flow trend but underestimated some of the peak discharge flows.

The Univariate LSTM model done in this study also showed some steep decrease while the DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J showed gradual decrease which is more representative of an observed hydrological behavior.

In S-8, the peak discharge flows as well as the trend were almost accurately captured by the Univariate LSTM. Thus, it is a better model in terms of trend compared to the Classical GR4J and the DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J. However, in S-9, differences relative to S-8 are minimal when the DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J and the Univariate LSTM were plotted together. There are still some differences in peak discharge flow, gradual decrease in discharge flow and positive low flow for DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J in comparison to the Univariate LSTM which showed the advantage of using the DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J.

Model comparison

The results of applied metrics are shown in Figs. 11 and 12 for both S-8 and S-9. Additionally, the two sub-catchments, S-8 and S-9, which were both precisely modeled by the DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J model are evaluated.

The discharge models set by HEC-HMS vs Univariate LSTM showed the highest accuracy based on the scatter plots and the employed performance indicators with NSE at 0.93 versus that of DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J’s 0.84; IA at 0.97 vs 0.93; LMI at 0.90 vs 0.82; and PBIAS at -18.86 vs -17.31. However, MAPE and RSR of both HEC-HMS vs Univariate LSTM and HEC-HMS vs DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J remained the same at 0.03 and 0.01, respectively.

On the other hand, Fig. 12 between HEC-HMS vs Univariate LSTM and HEC-HMS vs DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J, the latter (HEC-HMS vs DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J) has shown a higher value of NSE at 0.63; IA at 0.85; LMI at 0.76 and RSR at 0.02, while the former (HEC-HMS vs Univariate LSTM) has NSE at 0.42; IA at 0.76; LMI at 0.72 and RSR at 0.03. However, the PBIAS of the former (HEC-HMS vs Univariate LSTM) is slightly better at -17.84 while the latter (HEC-HMS vs DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J) is at -20.05. However, their MAPE values are both 0.02.

The above results for scatter plots and metrics have showed mainly how sub-catchment S-8 responded accurately to Univariate LSTM compared to the DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J model with respect to HEC-HMS generated discharge flows. This proves the findings of Yokoo et al.68 where he emphasized that deep learning is capable of getting precise results despite the lack of information about the physical characteristics of a catchment area. On the other hand, S-9 have showed that a DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J model can actually perform better by learning the physical components first of a hydrological catchment like rainfall and evapotranspiration and using classical hydrological parameters optimized by random optimization methods.

Figures 13 and 14 show the cumulative rainfall plots versus cumulative discharges. For S-8 (see Fig. 13), it can be seen that the estimates of (a) Cumulative DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J discharge values are less than (c) Cumulative Univariate LSTM; and (c) Cumulative Univariate LSTM discharge values are less than (b) Cumulative HEC-HMS discharge flows. However, the (d) Cumulative Classical GR4J substantially deviates from the other three (3) with flows much lower than the aforementioned discharge models.

S-9 (see Fig. 14), indicates that (a) Cumulative DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J and (c) Cumulative Univariate LSTM have almost the same trends and range of discharge values while (b) Cumulative HEC-HMS discharge flows have a linear trend with values higher than (a) and (c). Consistently, (d) Cumulative Classical GR4J discharge values have shown lower discharge values and a very different trend from the other three (3).

To assess the linearity of (a) and (c) in comparison to (b), we traced them using Fig. 15.

Figure 15 shows a more linear pattern change in S-9’s discharge flows for (a) Cumulative Rainfall vs Cumulative DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J compared to (b) Cumulative Rainfall vs Cumulative Univariate LSTM. This makes (a) Cumulative Rainfall vs Cumulative DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J model closer to the linear trend of the base model (b) Cumulative Rainfall vs Cumulative HEC-HMS.

Conclusion

This study evaluated the performance of a deep learning (DL)-assisted, parametrically optimized GR4J model to improve discharge simulation in data-scarce sub-catchments. One of the main objectives was to understand how DL-assisted or modified hydrological models can aid hydrologists in determining discharge flows in areas with limited datasets.

Graphical comparisons reinforced the findings that deep learning (DL)-assisted, parametrically optimized GR4J have improved the discharge simulation in data-scarce sub-catchments. In S-8 and S-9, the DL-assisted GR4J closely replicated the HEC-HMS hydrographs, effectively capturing peak discharges and recessions. In contrast, the Univariate LSTM alone produced partially unrealistic behavior, underestimating flow magnitudes, exhibiting abrupt low or even negative discharges, and oversmoothing or steeply declining trends that deviate from hydrological reality. These tendencies highlight the limitation of using DL alone without physical constraints (see Figs. 7–10).

Quantitative results demonstrated clear improvements (see Figs. 11–12). Classical GR4J underestimated discharge, while the LSTM overestimated peaks. The DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized GR4J achieved the highest consistency and balance between realistic peak and low flow estimation, with NSE = 0.63–0.84, IA = 0.85–0.93, LMI = 0.76–0.82, and low MAPE (≤ 0.03) and RSR (≤ 0.02). Although the Univariate LSTM captured general trends well, it underestimated some peaks despite reaching high values in performance metrics. The results highlight that neither DL nor classical models alone are sufficient; hybrid or DL-assisted approaches yield more reliable and realistic hydrological simulations, particularly in climate-sensitive, data-deficient regions like Samar.

This study also addressed challenges related to data availability. Rainfall data from the stations were inconsistent, with most containing only one to five years of records and rarely covering complete simultaneous events. Moreover, the absence of observed discharge or stream velocity data required the use of HEC-HMS outputs as the base reference for model comparison. Despite these data limitations, the DL-assisted GR4J proved capable of approximating discharge flow trends with improved accuracy in several sub-catchments, demonstrating the potential of hybridized models in data-scarce environments.

Nevertheless, this study has several limitations. Only one conceptual hydrological model (GR4J) and one DL architecture (Univariate LSTM) were tested, restricting the generalizability of the results. Additionally, the reliance on simulated discharge data limited the validation of absolute accuracy. The occurrence of hydrologically implausible low or negative flows in the LSTM model further indicates the need for incorporating physical constraints or hybrid coupling strategies.

Future research should therefore focus on (1) applying multiple DL structures such as Bi-LSTM, CNN-LSTM, and Transformer-based architectures; (2) extending the hybrid DL–GR4J framework to other conceptual or distributed hydrological models; (3) testing model robustness across catchments with varying climatic, topographic, and land-use conditions; and (4) developing verification procedures using time-series or signal-processing techniques to assess model suitability and performance indicator reliability.

In alignment with Nearing et al.32 “What role does hydrological science play in the age of machine learning?”, this study demonstrates that hydrological science and deep learning can complement each other and that DL models (e.g. LSTM) excel at identifying temporal patterns such as rainfall seasonality, while hydrological models provide essential physical grounding. Similarly, in the context of Blöschl et al.37 where the authors asked, “How can we disentangle and reduce model structural/parameter/input uncertainty in hydrological prediction?”, the DL-assisted GR4J could contribute to addressing this unresolved challenge for hydrological modeling when considering real-world possibilities.

In conclusion, the DL-assisted, parametrically optimized GR4J model substantially improved discharge simulation accuracy while retaining interpretability and physical realism. Although Univariate LSTM alone captured discharge trends, its tendency toward unrealistic flow behavior underscores the importance of hybrid, physically guided modeling approaches. The findings affirm that DL-assisted, parametrically- optimized hydrological models offer a practical and scientifically robust pathway for reliable discharge forecasting and water resource management in data-scarce and climate-sensitive regions.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the Figshare repository at [https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28915838.v1] (https:/doi.org/https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28915838.v1) Additional data sources include rainfall data, which can be accessed via Kaggle at [https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/ahyimi/rainfall-data] (https:/www.kaggle.com/datasets/ahyimi/rainfall-data) and evapotranspiration data available at [https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27136125.v1] (https:/doi.org/https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27136125.v1).

References

Yang, T. et al. Evaluation and machine learning improvement of global hydrological model-based flood simulations. Environ. Res. Lett. 14(11), 114027. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab4d5e (2019).

Nguyen, D. H. & Bae, D. H. Correcting mean areal precipitation forecasts to improve urban flooding predictions by using long short-term memory network. J. Hydrol. 584, 124710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2020.124710 (2020).

Han, H., Choi, C., Jung, J. & Kim, H. S. Deep learning with long short-term memory-based sequence-to-sequence model for rainfall-runoff simulation. Water 13(4), 437. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13040437 (2021).

Atieh, M., Gharabaghi, B. & Rudra, R. Entropy-based neural networks model for flow duration curves at ungauged sites. J. Hydrol. 529, 1007–1020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2015.08.068 (2015).

Mohammadi, B., Safari, M. J. S. & Vazifehkhah, S. IHACRES, GR4J and MISD-based multi conceptual–machine learning approach for rainfall–runoff modeling. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 12096. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-16215-1 (2022).

Kumanlioglu, A. A. & Fistikoglu, O. Performance enhancement of a conceptual hydrological model by integrating artificial intelligence. J. Hydrol. Eng. 24(11), 04019047. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)HE.1943-5584.0001850 (2019).

Humphrey, G. B., Gibbs, M. S., Dandy, G. C. & Maier, H. R. A hybrid approach to monthly streamflow forecasting: Integrating hydrological model outputs into a Bayesian artificial neural network. J. Hydrol. 540, 623–640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2016.06.026 (2016).

Kapoor, A., Pathiraja, S., Marshall, L. & Chandra, R. DeepGR4J: A deep learning hybridization approach for conceptual rainfall-runoff modelling. Environ. Model. Softw. 169, 105831. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2023.105831 (2023).

Chen, S., Huang, J. & Huang, J.-C. Improving daily streamflow simulations for data-scarce watersheds using the coupled SWAT-LSTM approach. J. Hydrol. 622, 129734. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2023.129734 (2023).

Cho, K. & Kim, Y. Improving streamflow prediction in the WRF-Hydro model with LSTM networks. J. Hydrol. 605, 127297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2021.127297 (2022).

Kim, Y., Chung, E.-S., Cho, H., Byun, K. & Kim, D. The future water vulnerability assessment of the Seoul metropolitan area using a hybrid framework composed of physically-based and deep-learning-based hydrologic models. Stoch. Env. Res. Risk Assess. 37(5), 1777–1798. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00477-022-02366-0 (2023).

Yang, C., Xu, M., Kang, S., Fu, C. & Hu, D. Improvement of streamflow simulation by combining physically hydrological model with deep learning methods in data-scarce glacial river basin. J. Hydrol. 625, 129990. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2023.129990 (2023).

Zhang, X., Qi, Y., Liu, F., Li, H., & Sun, S. (2023). Enhancing daily streamflow simulation using the coupled SWAT-BiLSTM approach for climate change impact assessment in Hai-River Basin. Scientific Reports, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-42512-4

Widiasari, I. R., Nugoho, L. E., Widyawan, & Efendi, R. W. (2018). Context-based hydrology time series data for a flood prediction model using LSTM. In 2018 5th International Conference on Information Technology, Computer, and Electrical Engineering (ICITACEE) (pp. 385–390). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICITACEE.2018.8576900

Du, B., Zhou, Q., Guo, J., Guo, S. & Wang, L. Deep learning with long short-term memory neural networks combining wavelet transform and principal component analysis for daily urban water demand forecasting. Expert Syst. Appl. 171, 114571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2021.114571 (2021).

Rasheed, Z., Aravamudan, A., Gorji Sefidmazgi, A., Anagnostopoulos, G. C. & Nikolopoulos, E. I. Advancing flood warning procedures in ungauged basins with machine learning. J. Hydrol. 609, 127736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2022.127736 (2022).

Wegayehu, E. B. & Muluneh, F. B. Multivariate streamflow simulation using hybrid deep learning models. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2021, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5172658 (2021).

Fu, M. et al. Deep learning data-intelligence model based on adjusted forecasting window scale: Application in daily streamflow simulation. IEEE Access 8, 32632–32651. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2974406 (2020).

Konapala, G., Kao, S.-C., Painter, S. L. & Lu, D. Machine learning assisted hybrid models can improve streamflow simulation in diverse catchments across the conterminous US. Environ. Res. Lett. 15(10), 104022. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aba927 (2020).

Koch, J., & Schneider, R. (2022). Long short-term memory networks enhance rainfall-runoff modelling at the national scale of Denmark. GEUS Bulletin, 49. https://doi.org/10.34194/geusb.v49.8292

Alizamir, M., Kim, S., Kisi, O. & Zounemat-Kermani, M. A comparative study of several machine learning-based non-linear regression methods in estimating solar radiation: Case studies of the USA and Turkey regions. Energy 197, 117239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2020.117239 (2020).

Abbot, J. & Marohasy, J. Application of artificial neural networks to rainfall forecasting in Queensland. Australia. Advances in Atmospheric Sciences 29(4), 717–730. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00376-012-1259-9 (2012).

Shortridge, J. E., Guikema, S. D. & Zaitchik, B. F. Machine learning methods for empirical streamflow simulation: A comparison of model accuracy, interpretability, and uncertainty in seasonal watersheds. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 20(7), 2611–2628. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-20-2611-2016 (2016).

Abbot, J. & Marohasy, J. Input selection and optimisation for monthly rainfall forecasting in Queensland, Australia using artificial neural networks. Atmos. Res. 138, 166–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosres.2013.11.002 (2014).

Lima, A. R., Cannon, A. J. & Hsieh, W. W. Nonlinear regression in environmental sciences using extreme learning machines: A comparative evaluation. Environ. Model. Softw. 73, 175–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2015.08.002 (2015).

Shen, C., Chen, X. & Laloy, E. Editorial: Broadening the use of machine learning in hydrology. Frontiers in Water 3, 681023. https://doi.org/10.3389/frwa.2021.681023 (2021).

Sit, M. et al. A comprehensive review of deep learning applications in hydrology and water resources. Water Sci. Technol. 82(12), 2635–2670. https://doi.org/10.2166/wst.2020.369 (2020).

Shen, C. et al. HESS Opinions: Incubating deep-learning-powered hydrologic science advances as a community. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 22(11), 5639–5656. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-22-5639-2018 (2018).

Shen, C. A transdisciplinary review of deep learning research and its relevance for water resources scientists. Water Resour. Res. 54(11), 8558–8593. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018WR022643 (2018).

Ji, H. et al. Adaptability of machine learning methods and hydrological models to discharge simulations in data-sparse glaciated watersheds. J. Arid. Land 13(6), 549–567. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40333-021-0066-5 (2021).

Rahimzad, M. et al. Performance comparison of an LSTM-based deep learning model versus conventional machine learning algorithms for streamflow forecasting. Water Resour. Manage 35(12), 4167–4187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-021-02937-w (2021).

Nearing, G. S. et al. (2021). What role does hydrological science play in the age of machine learning? Water Resources Research, 57(3). https://doi.org/10.1029/2020WR028091

Sezen, C., Bezak, N., Bai, Y. & Šraj, M. Hydrological modelling of karst catchment using lumped conceptual and data mining models. J. Hydrol. 576, 98–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2019.06.036 (2019).

Kwak, J., Han, H., Kim, S. & Kim, H. S. Is the deep-learning technique a completely alternative for the hydrological model? A case study on Hyeongsan River Basin, Korea. Stoch. Env. Res. Risk Assess. 36(6), 1615–1629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00477-021-02094-x (2021).

Kim, T. et al. Can artificial intelligence and data-driven machine learning models match or even replace process-driven hydrologic models for streamflow simulation?: A case study of four watersheds with different hydro-climatic regions across the CONUS. J. Hydrol. 598, 126423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2021.126423 (2021).

Ghimire, U. et al. Applicability of lumped hydrological models in a data-constrained river basin of Asia. J. Hydrol. Eng. 25(8), 05020018. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)HE.1943-5584.0001950 (2020).

Blöschl, G. et al. Twenty-three unsolved problems in hydrology (UPH) – A community perspective. Hydrol. Sci. J. 64(10), 1141–1158. https://doi.org/10.1080/02626667.2019.1620507 (2019).

Demirel, M. C., Booij, M. J. & Hoekstra, A. Y. Effect of different uncertainty sources on the skill of 10-day ensemble low-flow forecasts for two hydrological models. Water Resour. Res. 49(7), 4035–4053. https://doi.org/10.1002/wrcr.20294 (2013).

Scharffenberg, W., Ely, P., Daly, S., Fleming, M., & Pak, J. (2010). Physically-based simulation components. In Proceedings of the 2nd Joint Federal Interagency Conference, Las Vegas, NV, June 27 – July 1, 2010; p.8.

Perrin, C., Michel, C. & Andréassian, V. Improvement of a parsimonious model for streamflow simulation. J. Hydrol. 279(1–4), 275–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1694(03)00225-7 (2003).

Edijatno, Nascimento, N. O., Yang, X., Makhlouf, Z., & Michel, C. (1999). GR3J: A daily watershed model with three free parameters. Hydrological Sciences Journal, 44(2), 263–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/02626669909492221

Rossi, M. W., Whipple, K. X. & Vivoni, E. R. Precipitation and evapotranspiration controls on daily runoff variability in the contiguous United States and Puerto Rico. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 121(1), 128–145. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015JF003446 (2016).

Bárdossy, A. & Singh, S. K. Robust estimation of hydrological model parameters. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 12, 1273–1283. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-12-1273-2008 (2008).

Zakouni, A., Luo, J., & Kharroubi, F. (2016). Random optimization algorithm for solving the static manycast RWA problem in optical WDM networks. In 2016 International Conference on Information and Communication Technology Convergence (ICTC) (pp. 640–645). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICTC.2016.7763552

Kashiwao, T. et al. A neural network-based local rainfall prediction system using meteorological data on the internet: A case study using data from the Japan Meteorological Agency. Appl. Soft Comput. 56, 317–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2017.03.015 (2017).

Huang, Y.-C., Ding, Y.-A. & Chang, X.-Y. An optimal production scheduling under random selection within multi-objective based on batch movement and asymmetrical setup time. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 35(8), 506–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681015.2018.1520746 (2018).

Necesito, I. V. et al. Deep learning-based univariate prediction of daily rainfall: Application to a flood-prone, data-deficient country. Atmosphere 14(4), 632. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos14040632 (2023).

Necesito, I. V. et al. Modeling daily evapotranspiration time series based on non-linear autoregressive exogenous (NARX) method and climate variables for a data-deficient region. PLoS ONE 20(2), e0318675. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0318675 (2025).

Feigl, M., Herrnegger, M., Klotz, D., & Schulz, K. (2020). Function space optimization: A symbolic regression method for estimating parameter transfer functions for hydrological models. Water Resources Research, 56(10). https://doi.org/10.1029/2020WR027385

Oueldkaddour, F. Z. E., Wariaghli, F., Brirhet, H. & Yahyaoui, A. Hydrological modeling of rainfall-runoff of the semi-arid Aguibat Ezziar watershed through the GR4J model. Limnological Review 21(3), 119–126. https://doi.org/10.2478/limre-2021-0011 (2021).

Andréassian, V., Perrin, C. & Michel, C. Impact of imperfect potential evapotranspiration knowledge on the efficiency and parameters of watershed models. J. Hydrol. 286(1–4), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2003.09.030 (2004).

Wang, F., Huang, G. H., Fan, Y. & Li, Y. P. Robust sub-sampling ANOVA methods for sensitivity analysis of water resource and environmental models. Water Resour. Manage 34(10), 3199–3217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-020-02608-2 (2020).

Nemri, S. & Kinnard, C. Comparing calibration strategies of a conceptual snow hydrology model and their impact on model performance and parameter identifiability. J. Hydrol. 582, 124474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2019.124474 (2020).

Wanzala, M. A. et al. Assessment of global reanalysis precipitation for hydrological modelling in data-scarce regions: A case study of Kenya. Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies 41, 101105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrh.2022.101105 (2022).

Flores, N. et al. Comparison of three daily rainfall-runoff hydrological models using four evapotranspiration models in four small forested watersheds with different land cover in south-central Chile. Water 13(22), 3191. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13223191 (2021).

Bezak, N., Jemec Auflič, M. & Mikoš, M. Application of hydrological modelling for temporal prediction of rainfall-induced shallow landslides. Landslides 16(7), 1273–1283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-019-01169-9 (2019).

Ansori, M. B., & Anwar, N. (2022). The TRMM rainfall-runoff transformation model using GR4J as a prediction of the Tuga Dam reservoir inflow. International Journal of GEOMATE, 9(97). https://doi.org/10.21660/2022.97.1975

Shin, M.-J. & Kim, C.-S. Component combination test to investigate improvement of the IHACRES and GR4J rainfall–runoff models. Water 13(15), 2126. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13152126 (2021).

Gosling, S. N. & Arnell, N. W. Simulating current global river runoff with a global hydrological model: Model revisions, validation, and sensitivity analysis. Hydrol. Process. 25(7), 1129–1145. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.7727 (2011).

Weiland, F. C. S., van Beek, L. P. H., Kwadijk, J. C. J. & Bierkens, M. F. P. The ability of a GCM-forced hydrological model to reproduce global discharge variability. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 14(8), 1595–1621. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-14-1595-2010 (2010).

Kozlowsky, T. T., & Pallardy, S. G. (1997). Growth control in woody plants. Retrieved November 29, 2022, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/earth-and-planetary-sciences/flooded-soil

Zong, Y., Xiao, Q. & Lu, S. Acidity, water retention, and mechanical physical quality of a strongly acidic Ultisol amended with biochars derived from different feedstocks. J. Soils Sediments 16, 177–190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-015-1187-2 (2016).

Visayas State University. (2019, April 3). Food for the Hungry taps PhilRootcrops for livelihood program in Samar. https://www.vsu.edu.ph/rde-media/rde-news/2192-food-for-the-hungry-taps-philrootcrops-for-livelihood-program-in-samar

Cock, J. H., & Howeler, R. H. (1978). The ability of cassava to grow on poor soils. ASA Special Publications, pp. 145–154. American Society of Agronomy, Crop Science Society of America, and Soil Science Society of America. https://doi.org/10.2134/asaspecpub32.c6

El-Sharkawy, M. A. Cassava biology and physiology. Plant Mol. Biol. 56, 481–501. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11103-005-2270-7 (2004).

USDA NRCS National Plant Data Center. Retrieved November 5, 2025, from https://plants.usda.gov/DocumentLibrary/plantguide/pdf/pg_maes.pdf#:~:text=General:%20Cassava%20grows%20best%20on%20light%20sandy,and%20on%20soils%20of%20relatively%20low%20fertility

Lavtar, K., Bezak, N. & Šraj, M. Rainfall-runoff modeling of the nested non-homogeneous Sava River sub-catchments in Slovenia. Water 12(1), 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12010128 (2019).

Yokoo, K. et al. Capabilities of deep learning models on learning physical relationships: Case of rainfall–runoff modeling with LSTM. Sci. Total Environ. 802, 149876. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149876 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Professor Hung Soo Kim for his invaluable guidance and support in improving this manuscript. We also extend our appreciation to the editors and reviewers for their constructive feedback and efforts in helping us enhance the quality of this work.

Funding

This work was supported by Korea Environmental Industry & Technology Institute (KEITI) through R&D Program for Innovative Flood Protection Technologies against Climate Crisis Project, funded by Korea Ministry of Environment (MOE) (2022003460002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Imee V. Necesito: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Data curation, Formal analysis, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Investigation, Software, Writing—original draft, Supervision, Writing—review & editing. Junhyeong Lee: Funding, Writing—review & editing. Seonhok Baek, Yujin Kang, Duke Yu-Min Kim, Kyunghun Kim: Writing—review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Necesito, I.V., Lee, J., Baek, S. et al. Realistic daily discharge modelling in data-deficient regions using DL-assisted, parametrically-optimized hydrological model. Sci Rep 16, 1011 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30670-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30670-6