Abstract

Denture stomatitis is frequently associated with Candida species, particularly Candida albicans. The emergence of drug-resistant C. albicans strains has highlighted the need for alternative approaches to prevent and manage denture stomatitis. In this context, the antifungal effects of Azadirachta indica (neem) leaf and Ficus benghalensis (banyan) aerial root extracts were evaluated and compared. The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of herbal extracts from A. indica and F. benghalensis were determined against azole-resistant, azole-susceptible, and standard strains (C. albicans MTCC 3018) of C. albicans using various solvents. A fungal adhesion assay and an evaluation of the antifungal efficacy of acrylic resin discs pre-treated with ethanolic herbal extracts were also conducted. The ethanolic herbal extracts inhibited all tested fungal strains, with a MIC of 50 µg/ml. A reduction in fungal adhesion of 72% ± 3.1% at 3 h and 76.7% ± 2.8% at 36 h was observed for the azole-resistant strain on denture base resin discs treated with the ethanolic extract of A. indica. The antifungal efficacy of A. indica-treated denture resin was 71% ± 4.2% against the azole-resistant strain and 100% ± 0.0% against the azole-susceptible strain of C. albicans. These findings suggest that the evaluated herbal extracts possess significant antifungal properties. The reduction in viable C. albicans adhesion to acrylic denture surfaces indicates the potential of A. indica to be used as a natural alternative to conventional antifungal agents for the prevention and treatment of drug-resistant denture stomatitis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acrylic denture resins are susceptible to microbial adhesion, resulting in the formation of plaque. The microbial population on dentures may serve as a potential source of both oral and systemic diseases. When denture plaque coexists with poor denture hygiene, it contributes significantly to Candida-associated denture stomatitis1. This condition affects long-term denture wearers and has a high prevalence rate, ranging from 25% to 65%2.

Mechanical cleaning of dentures by brushing can be challenging for elderly individuals3. Chemical disinfection and microwave irradiation have been suggested as alternatives; however, the long-term effects of these treatments on denture materials remain uncertain4.

The widespread and indiscriminate use of antimicrobial agents in healthcare has contributed to the development of drug-resistant microbes. In contrast, plant-based products are generally considered safer than conventional pharmacological drugs and are less harmful to the environment. The leaves of Azadirachta indica (neem) exhibit a significant anti-candidal effect against Candida albicans by preventing its colonization5. A previous study reported that the antimicrobial activity of the ethanolic extract of neem leaves against C. albicans was comparable to that of 3% sodium hypochlorite and significantly greater than that of 2% chlorhexidine6.

The antimicrobial activity of underground root extracts of Ficus benghalensis (banyan) has also been documented against Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Escherichia coli, suggesting that the aerial roots of F. benghalensis may also serve as a promising antimicrobial agent7. Therefore, we evaluated and compared the antifungal effects of neem leaf and banyan aerial root extracts against azole-susceptible and azole-resistant strains of C. albicans.

Materials and methods

The A. indica leaf and F. benghalensis aerial root samples were collected from the State Forest Research Institute, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India (12.8745° N, 80.0809° E). The herbal samples underwent taxonomic identification and the preparation of reference herbarium specimens by a plant biologist. The voucher specimen of the collected plant has been deposited in the Herbarium of the Department of Plant biotechnology, Bharath Institute of Higher Education and Research (BIHER), Chennai, India, under the voucher number BIHER/PHC/2017/023. The leaf and root extracts were prepared using the cold maceration method8. The leaves and aerial roots were thoroughly rinsed with water to remove dust and foreign matter, then shade-dried for seven days. After drying, the samples were finely ground using a grinder and stored in amber-coloured bottles.

Extraction was carried out by immersing 20 g of the powdered sample in 200 mL of various solvents—ethanol, ethyl acetate, chloroform, methanol, acetone, or water. The mixtures were incubated in a shaker-incubator at 25 °C for 24 h. After incubation, they were filtered using Whatman filter paper, and the filtrates were dried. These extracts were then dissolved in 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to a final concentration of 1 mg/mL and stored at 4 °C until further use9.

The C. albicans MTCC 3018 (IMTECH, Chandigarh, India), azole-resistant and azole-susceptible strains of C. albicans were procured from the Department of Microbiology of a Dental college. The antifungal susceptibility tests (Agar diffusion assay and E test) were performed to confirm the susceptibility and resistance pattern of C. albicans strains. The cultures were inoculated onto Sabouraud Dextrose Agar (SDA) supplemented with 0.05 g/L of chloramphenicol to obtain pure fungal isolates. For inoculum preparation, yeast suspensions prepared from 1 to 3 pure colonies were adjusted in Sabouraud Dextrose Broth (SDB) to match the turbidity of a 0.5 McFarland standard (optical density [OD] = 0.12–0.15 at 530 nm), corresponding to 1–5 × 10⁶ colony-forming units (CFU)/mL10.

Agar well diffusion assay and microbroth dilution assay

Agar well diffusion was carried out against all three isolates of C. albicans (C. albicans MTCC 3018, azole-resistant and azole-susceptible strains of C. albicans.) Mueller Hinton Agar supplemented with 2% glucose and 0.5 µg/ml methylene blue dye was used for agar well diffusion assay. The assay was tested with 100 µl of the A. indica and F. benghalensis extracts. A separate agar well diffusion assay was performed using 10% DMSO to confirm that it did not independently exhibit any anticandidal activity. Amphotericin B (50 µg -Himedia) served as the positive control and sterile saline as the negative control. The microbroth dilution method was performed in accordance with the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines11to determine the MIC of A. indica and F. benghalensis extracts against C. albicans MTCC 3018, azole-resistant and azole-susceptible strains of C. albicans. In brief, 100 µL of sterile Sabouraud Dextrose Broth (SDB) was dispensed into all wells of a sterile 96-well microtiter plate. Subsequently, 100 µL (comprising a concentration of 100 µg) of the plant extract was added to the first well and subjected to two-fold serial dilution across wells 1 to 11 for dilution of the 100 µg concentration. From the eleventh well, 100 µL was discarded to maintain uniform volume. The twelfth well, containing only broth and fungal suspension without the extract, served as the growth control. Then, 10 µL of a standardized C. albicans suspension (adjusted to approximately 1 × 10⁶ CFU/mL) was added to each well. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Each assay was conducted in triplicate. To determine the MIC of the herbal extracts, five µL from each well was spot-inoculated onto SDA plates and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h to evaluate fungal growth. The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of the extract that completely inhibited visible fungal growth on SDA.

Acrylic disc fabrication

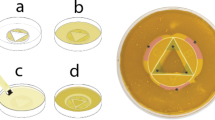

Heat-polymerized polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) resin (Dental Products of India, Mumbai, India) was selected for specimen fabrication. Standardized disc-shaped samples were prepared, each measuring 6.0 mm in diameter and 2.0 mm in thickness, in order to maintain uniformity for subsequent testing. To ensure reproducibility, metal master discs of the same dimensions were first fabricated through precision milling12. These served as templates for impression making. Impressions of the metal discs were obtained using a high-consistency silicone rubber material13 (Aquasil Putty, Dentsply, USA), which provided accurate negative replicas (Fig. 1). The silicone molds were then used to cast wax patterns with modeling wax (DPI, Mumbai, India), thereby standardizing the size and shape of the test samples. The wax patterns were invested in a conventional dental flask and processed into heat-cured acrylic resin discs by the compression molding technique14, using a flask and clamp assembly. The preparation of all acrylic specimens strictly adhered to the manufacturer’s guidelines. A powder-to-liquid ratio of 3:1 by volume was maintained for the acrylic resin mix. Polymerization was carried out in a water bath using a standard curing cycle, consisting of 74 °C for 2 h followed by terminal boiling at 100 °C for 1 h, to ensure complete polymerization and minimize residual monomer content15.

After deflasking, the specimens were retrieved and subjected to conventional finishing and polishing using abrasive sandpapers of progressively finer grits, followed by pumice polishing on a lathe to achieve a smooth surface. Post-polishing, the discs were immersed in an ultrasonic cleaner for 20 min to remove surface debris. Finally, all specimens were dried on absorbent paper, packed in sterilization pouches, and sterilized with ethylene oxide gas to eliminate microbial contamination before use in the experimental phase.

Fungal adhesion assay on denture base resin

The adhesion assay was performed following the method described by Samaranayake and MacFarlane16, with minor modifications. Forty acrylic discs were pre-treated in 5 mL (300 µg/ml) of different solutions (ethanol extract of A. indica, ethanol extract of F. benghalensis, 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate or normal saline) placed in glass beakers for 30 min at room temperature. The final concentration of the extracts in the solvents was prepared as 300 µg/ml. The treatment groups included: Group A – ethanol extract of A. indica 300 µg/ml; Group F – ethanol extract of F. benghalensis300µg/ml; Group CHX – 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate w/v (Rexidin, Indoco, Mumbai, India); and Group NS – normal saline (SRL Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India). Chlorhexidine served as the positive control, while normal saline served as the negative control. Each group included 10 discs.

After treatment, the discs were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Three discs from each group were then placed into three separate 10 mL glass test tubes, each containing 4 mL of yeast-cell suspension adjusted to match a 0.5 McFarland standard (~ 10⁶ CFU/mL). The suspensions included azole-resistant, azole-susceptible, and Candida albicans MTCC 3018, ensuring complete immersion of the discs. The tubes were incubated in a shaker-incubator at 37 °C for 3 h at 120 rpm, followed by three successive washes with PBS to remove non-adherent yeast cells. For control three discs were placed in sterile Sabouraud dextrose broth.

The discs were then stained using first and second step of Gram staining, omitting the decolourization and counterstaining step17. Once air-dried, the stained discs were mounted on glass slides and yeast cells were enumerated under light microscope (Olympus CX-31, Japan) using glycerol. Twenty randomly selected fields were examined under 40× magnification18,19.

The average number of yeast cells from 20 microscopic fields was calculated for each of the three acrylic discs and expressed as the mean cell count for that subgroup. To standardize the data, filamentous forms were excluded, and budding daughter cells were counted only once. The procedure was repeated using three additional discs per group to determine adhesion counts after 36 h of incubation. Blank control discs were examined first to clearly distinguish them from the acrylic discs with adhered, stained yeast cells, which appeared as hazy images. An overview of the assay methodology is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Antifungal efficacy of denture base acrylic resin pre-treated with plant extracts on C. albicans biofilm

Forty prepared acrylic discs were treated in 5 mL of the following solutions prepared with 10% DMSO and placed in glass beakers, for 30 min at room temperature: Group A – ethanol extract of A. indica (300 µg/ml); Group F – ethanol extract of F. benghalensis (300 µg/ml); Positive Control (Group CHX) – 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate; and Negative Control (Group NS) – normal saline. Each group included 10 discs.

Following treatment, the discs were rinsed with PBS. Three discs from each group were then placed in three 10 mL glass test tubes, each containing 4 mL of standardized Sabouraud dextrose broth yeast-cell suspensions of azole-resistant (Subgroup AR), azole-sensitive (Subgroup AS), and C. albicans MTCC 3018 ensuring full immersion of the discs. These subgroups were designated within each of the four groups: A, F, CHX, and NS. The yeast suspension was standardized to 0.5 McFarland (approximately 1 to 5 × 10⁶ CFU/mL). The discs were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C at 75 rpm, followed by washing with 1 mL of PBS. Colony-forming unit (CFU) analysis was used to quantify viable yeast cells adhering to acrylic resin discs pre-treated with plant extracts, following 24 h of biofilm development.

Post-incubation, the resin discs were transferred to polypropylene tubes containing 1 mL of sterile PBS and subjected to ultrasonic vibration (Ultrasonic Cleaner, Arotec, Brazil) for 20 min to dislodge adherent cells20. The sonicated solutions were serially diluted in PBS (10⁻¹ to 10⁻⁴). A 50 µL aliquot from the final dilution was plated onto Sabouraud Dextrose Agar (SDA) and incubated aerobically at 37 °C for 48 h, after which the colonies were counted. The assay was performed in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

A one-way ANOVA was used to determine the level of significance in the number of fungal adhesions on acrylic resin discs among the three strains of C. albicans, measured after 3 h and 36 h of incubation. An independent t-test was employed to compare the number of fungal adhesions within each C. albicans strain between the two time points (3 h and 36 h). The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to assess the statistical significance of the results obtained from the fungal viability assay. For all statistical analyses, a p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant at a 95% confidence interval.

Results and interpretation

Zone of Inhibition and mic determination

The 10% DMSO solvent exhibited no antifungal activity in the agar well diffusion assay, indicating that 10% DMSO did not interfere with the assay results. Normal saline, used as the negative control, produced no zone of inhibition. Amphotericin B, on the other hand, showed a consistent zone of inhibition measuring 15 mm against both azole-resistant and azole-susceptible isolates. Therefore, Amphotericin B was employed as the positive control for comparison with the values of A. indica and F. benghalensis. The azole-resistant strain exhibited resistance to fluconazole, itraconazole, and miconazole. The herbal extracts did not show any inhibition except ethanolic extracts of A. indica and F. benghalensis. The zone of inhibition for ethanolic extracts of (A) indica was 16 mm for C. albicans azole sensitive and resistant strains and 17 mm for C. albicans MTCC 3018 respectively. Ethanolic extracts of F. benghalensis showed a zone of inhibition of 15 mm for C. albicans azole sensitive and resistant strains. These values were on par with amphotericin (B) The MIC determined for the herbal extracts are presented in Table 1.

Fungal adhesion on denture base resin

The results of the fungal adhesion assay on denture base resin pre-treated with the herbal extracts are presented in Table 2; Fig. 3. One-way ANOVA performed using Epi Info statistical software, revealed a statistically significant difference in the adhesion of all three C. albicans strains among the four pre-treatment groups at both 3 h and 36 h of incubation.

The independent t-test (Table 3) showed a statistically significant difference in the adhesion of all three C. albicans strains between 3 h and 36 h of incubation across all pre-treatment groups.

Antifungal efficacy of denture base acrylic resin pre-treated with plant extracts on C. albicans biofilm

No viable yeast cells of the azole-sensitive strain or the standard strain of C. albicans were detected after 24 h of incubation on denture acrylic discs pre-treated with chlorhexidine or the ethanolic extract of A. indica for 30 min. Among all pre-treated acrylic discs, the highest number of viable yeast cells after 24 h of incubation was observed in the azole-resistant strain (Fig. 4).

The Kruskal-Wallis test revealed a statistically significant difference in the viability of all three C. albicans strains among the four pre-treatment groups. The Post Hoc Dunn test revealed a statistically significant difference in the viability of fungal cells of the azole-sensitive strain on denture acrylic resin discs pre-treated with the ethanolic extract of F. benghalensis when compared to those treated with the ethanolic extract of A. indica and chlorhexidine (p < 0.05). A significant difference was also observed in the viability of azole-sensitive fungal cells on discs treated with normal saline compared to those treated with the ethanolic extract of A. indica and chlorhexidine (p < 0.05). For the azole-resistant strain, the Post Hoc Dunn test showed a statistically significant reduction in fungal cell viability on acrylic resin discs pre-treated with the ethanolic extract of A. indica when compared to those treated with the ethanolic extract of F. benghalensis and normal saline (p < 0.05). Similarly, for the standard strain, a statistically significant difference in fungal viability was observed on discs treated with normal saline when compared to those treated with the ethanolic extract of A. indica and chlorhexidine (p < 0.05).

Discussion

Drug resistance in C. albicans

C. albicans is a common member of the oral microbiota but can become pathogenic under certain conditions, leading to infections such as denture stomatitis. This condition is prevalent among denture wearers, with studies indicating a global prevalence ranging from 20% to 67%21. The pathogenesis involves the formation of biofilms on denture surfaces, which serve as reservoirs for C. albicans, facilitating persistent infections and potential systemic dissemination.

The increasing resistance of C. albicans to conventional antifungal agents, particularly azoles, poses a significant challenge. Mutations in the ERG11 gene reduce azole binding to its target enzyme, while overexpression of ERG11 increases the enzyme levels, reducing drug effectiveness22. Efflux pumps such as CDR1, CDR2, and MDR1 actively expel azoles from the fungal cell, and are upregulated by mutations in their transcriptional regulators TAC1 and MRR123. Other mechanisms include ERG3 inactivation, which blocks toxic sterol buildup, and chromosomal changes like isochromosome formation that amplify resistance genes24. Together, these adaptations allow C. albicans to survive prolonged azole exposure in clinical settings. These developments, coupled with the side effects and costs associated with synthetic antifungals, underscore the need for alternative treatments.

A. indica, commonly known as neem, has been traditionally used in Indian medicine for various ailments, including oral infections. Studies have demonstrated the antifungal properties of neem leaf extracts against C. albicans, with efficacy comparable to standard antifungal agents25. The active compounds in neem, such as azadirachtin and nimonol, contribute to its antifungal activity26.

Similarly, F. benghalensis, known as the banyan tree, has been recognized for its medicinal properties. The presence of bioactive compounds like flavonoids and terpenoids contributes to its antimicrobial efficacy27.

The exploration of plant-based antifungal agents like A. indica and F. benghalensis offers promising alternatives to conventional treatments, particularly in the context of rising antifungal resistance and the need for cost-effective, safe therapies. Further research into their mechanisms of action and clinical efficacy is warranted to fully harness their therapeutic potential.

MIC

The ethanolic extracts of A. indica and F. benghalensis were the only extracts that inhibited all three strains of C. albicans. The MIC for both extracts was found to be 50 µg/mL. These findings align with previous research15 in which ethanolic neem leaf extracts exhibited significant antifungal activity against C. albicans, with MIC values ranging from 150 to 500 µg/mL. These studies support the potential of A. indica as an effective antifungal agent.

The anticandidal effect of A. indica leaf extracts observed in the present study may be attributed to its diverse array of bioactive constituents. This hypothesis has been supported by previous studies suggesting that compounds such as quercetin, β-sitosterol, and desacetylimbin contribute significantly to its antifungal activity28. Other researchers have reported the presence of limonoids (e.g., meliantriol), triterpenes, and a range of bitter principles including nimbidin, nimbinin, nimbin, nimbosterol, margosine, and azadirachtin as key antifungal agents29. Additionally, the antimicrobial potential of A. indica may be enhanced by the presence of alkaloids, glycosides, resins, phenols, terpenes, and gums30. Some investigators have also proposed that neem extracts inhibit Candida virulence by suppressing protease enzyme activity, a crucial factor in fungal invasion and tissue degradation. Collectively, these phytochemicals likely act synergistically, contributing to the observed antifungal effects against C. albicans.

The variation in MIC values observed between the present study and previous research may be attributed to differences in extraction protocols. Factors such as the method of extraction (infusion vs. maceration), duration of exposure, and temperature conditions during the process can significantly influence the phytochemical yield and bioactivity of the extract. Additionally, discrepancies in the ratio of plant material to solvent and the particle size of the powdered leaf sample may affect the concentration and availability of active compounds. Variability in geographical origin, plant age, and harvesting season can also contribute to fluctuations in the potency of herbal extracts. Such methodological variations highlight the importance of standardized preparation protocols to ensure reproducibility and comparability across studies.

Fungal adhesion on denture base resin

In the present study, discs treated with normal saline consistently showed the highest yeast adhesion across all strains and time intervals, with the azole-sensitive strain reaching 100.15 cells/mm² at 36 h. In contrast, chlorhexidine exhibited the lowest adhesion values (≤ 4.3 cells/mm²), closely followed by A. indica, especially against the standard strain (3 h: 1 cell/mm²; 36 h: 3.35 cells/mm²). A. indica also performed better than F. benghalensis, particularly against the azole-resistant strain (36 h: 8.35 vs. 17.55 cells/mm²). Across all groups, fungal adhesion increased notably over time, especially in untreated samples pretreated with normal saline. These results highlight the significant antifungal potential of A. indica as a natural alternative to chlorhexidine in reducing Candida adhesion on denture bases.

The one-way ANOVA results demonstrated that fungal adhesion to denture base resin differed significantly among the groups at both 3 and 36 h of incubation for all tested Candida albicans strains. The consistently low p-values (< 0.001) indicate that the observed differences are highly unlikely to have occurred by chance and reflect a true biological effect. Importantly, the statistical significance across azole-resistant, azole-sensitive, and standard strains suggests that the tested intervention influenced fungal adhesion irrespective of the strain’s antifungal susceptibility profile. These findings support the robustness of the antifungal effect and emphasize the potential clinical applicability of the material in reducing candidal colonization on denture surfaces.

Independent t-test results showed that both Azadirachta indica and Ficus benghalensis ethanol extracts significantly reduced fungal adhesion on denture base resin at 3 and 36 h across azole-resistant, azole-sensitive, and standard strains (p < 0.05). The effect was strongest for A. indica against resistant and standard strains at 36 h (p < 0.001), while F. benghalensi also maintained consistent antifungal activity. Chlorhexidine demonstrated expected inhibitory effects, confirming the assay reliability. These findings indicate the potential of plant-based extracts as adjuncts in preventing candidal colonization on denture surfaces.

The results of the present study, which demonstrated that denture base resin discs pre-treated with the ethanolic extract of A. indica exhibited reduced adhesion of C. albicans, are consistent with findings reported in recent literature. A study by Shorouq-Khalid Hamid et al. showed a significant reduction in C. albicans colony counts on denture acrylic resin specimens incorporating neem leaf powder compared to conventional resin specimens31. However, they noted a disadvantage in the form of discoloration and compromised aesthetics, along with reports of a bitter taste in the mouth. Similar antifungal activity was observed by Polaquini et al., who evaluated the antimicrobial effects of neem extract on composite dental resin materials. Their study confirmed the extract’s potential in inhibiting biofilm formation and reducing C. albicans colonization on resin surfaces6. These findings support the use of A. indica as a surface treatment alternative to direct incorporation into prosthetic materials.

Extracts of A. indica reduce the adhesion of C. albicans to denture resin through multiple bioactive mechanisms. Phytochemicals such as nimbidin and azadirachtin disrupt fungal cell wall and membrane integrity, weakening the organism’s ability to attach to surfaces15. Hyphal development, a critical factor in Candida adhesion and biofilm formation, is also inhibited by neem constituents19. Studies suggest that neem may interfere with the expression of adhesion-related genes, including the ALS gene family, thereby impairing fungal surface binding32. In addition, neem compounds suppress the secretion of hydrolytic enzymes like proteases and phospholipases, which facilitate colonization and tissue invasion. Surface modification effects induced by neem treatment—such as changes in surface energy or electrostatic charge—may further contribute to reduced microbial adherence to acrylic resin.

Candidal CFU viability assay

The azole-resistant strain showed the highest viability among all strains in the viability assay. The extract of A. indica and chlorhexidine completely inhibited the azole-sensitive and standard strains while significantly reducing the viability of the azole-resistant strain to 75.01 × 10³ CFU/mm², outperforming both the extract of F. benghalensis and chlorhexidine, indicating its strong antifungal potential.

For the azole-resistant strain, the post hoc Dunn test revealed no significant difference in antifungal activity between Azadirachta indica extract and chlorhexidine (p = 0.49), indicating comparable inhibitory potential. Similar non-significant differences were also observed for the azole-sensitive and standard strains (p = 1.0).

A. indica exhibits potent antifungal activity through multiple mechanisms. Azadirachtin disrupts fungal cell membranes, causing leakage and cell death33. It inhibits key fungal enzymes like chitin synthase and glucan synthase, hindering cell wall formation34. It also interferes with the synthesis of structural cell wall components such as chitin and glucans. Additionally, it modulates fungal gene expression involved in metabolism and stress responses, further impairing fungal viability35.

Future scope

Future studies should focus on identifying, isolating and characterizing the specific antifungal compounds in A. indica. Long-term in vivo studies are needed to assess biocompatibility and clinical efficacy in denture wearers. Exploring synergistic effects of A. indica with conventional antifungals may enhance therapeutic outcomes. Standardization of extraction methods and formulation protocols will improve reproducibility and application potential.

Conclusion

The present study confirms the potent antifungal activity of A. indica ethanol leaf extract, particularly against azole-resistant Candida albicans. Its ability to reduce adhesion and viability on denture resin surfaces suggests promising applications in denture hygiene and oral candidiasis management. Neem extract may serve as a natural, effective, and biocompatible alternative to synthetic antifungal agents in prosthodontic care.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Pereira-Cenci, T., Bel Cury, D., Crielaard, A. A., Ten Cate, J. M. & W. & Development of Candida-associated denture stomatitis: new insights. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 16, 86–94. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1678-77572008000200002 (2008).

Chandra, J. et al. Biofilm formation by the fungal pathogen Candida albicans: development, architecture, and drug resistance. J. Bacteriol. 183, 5385–5394. https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.183.18.5385-5394.2001 (2001).

Kulak, Y., Arikan, A. & Kazazoglu, E. Existence of Candida albicans and microorganisms in denture stomatitis patients. J. Oral Rehabil. 24, 788–790. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2842.1997.00659.x (1997).

Machado, A. L., Breeding, L. C., Vergani, C. E. & da Perez, C. Hardness and surface roughness of Reline and denture base acrylic resins after repeated disinfection procedures. J. Prosthet. Dent. 102, 115–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3913(09)60123-6 (2009).

Surya, R. S. & Balsaraf, K. D. Antifungal efficacy of Azadirachta indica (neem) – an in vitro study. Braz J. Oral Sci. 13, 242–245. https://doi.org/10.1590/1677-3225v13n3a13 (2014).

Polaquini, S. R., Svidzinski, T. I., Kemmelmeier, C. & Gasparetto, A. Effect of aqueous extract from Neem (Azadirachta indica A. Juss) on hydrophobicity, biofilm formation and adhesion in composite resin by Candida albicans. Arch. Oral Biol. 51, 482–490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archoralbio.2005.11.007 (2006).

Gayathri, M. & Kannabiran, K. Antimicrobial activity of Hemidesmus indicus, Ficus benghalensis, and Pterocarpus marsupium Roxb. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 72, 641–643. https://doi.org/10.4103/0250-474X.78519 (2010).

Bitwell, C., Indra, S. S., Luke, C. & Kakoma, M. K. A review of modern and conventional extraction techniques and their applications for extracting phytochemicals from plants. Sci. Afr. 19, e01585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sciaf.2023.e01585 (2023).

Abubakar, A. R. & Haque, M. Preparation of medicinal plants: basic extraction and fractionation procedures for experimental purposes. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 12, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.4103/jpbs.JPBS_175_19 (2020).

Lee, J. A. & Chee, H. Y. In vitro antifungal activity of equol against Candida albicans. Mycobiology 38, 328–330. https://doi.org/10.4489/MYCO.2010.38.4.328 (2010).

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts; approved standard, 3rd ed. CLSI document M27-A3. CLSI, (Wayne, PA, 2008).

Ismaeil, M. A. A. & Ebrahim, M. I. Antifungal effect of acrylic resin denture base containing different types of nanomaterials: a comparative study. J. Int. Oral Health. 15, 78–83. https://doi.org/10.4103/jioh.jioh_62_22 (2023).

Marcroft, K. R., Tencate, R. L. & Hurst, W. W. Use of a layered silicone rubber mold technique for denture processing. J. Prosthet. Dent. 11 (4), 657–664. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3913(61)90173-1 (1961).

Mahler, D. B. Inarticulation of complete dentures processed by the compression molding technique. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1, 551–559. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3913(51)90040-6 (1951).

Singh, S., Palaskar, J. N. & Mittal, S. Comparative evaluation of surface porosities in conventional heat-polymerized acrylic resin cured by water bath and microwave energy with microwavable acrylic resin cured by microwave energy. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 4, 147–151. https://doi.org/10.4103/0976-237X.114844 (2013).

Samaranayake, L. P. & MacFarlane, T. W. An in vitro study of the adherence of Candida albicans to acrylic surfaces. Arch. Oral Biol. 25, 603–609. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-9969(80)90075-8 (1980).

Nolff, T. M. et al. The role of gram stain in differentiating superficial cutaneous fungal organisms. J. Cutan. Pathol. 52, 511–513. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.14827 (2025).

Redfern, J. et al. Critical analysis of methods to determine growth, control and analysis of biofilms for potential non-submerged antibiofilm surfaces and coatings. Biofilm 7, 100187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioflm.2024.100187 (2024).

Darwish, M. et al. Effect of denture adhesives on adhesion of Candida albicans to denture base materials: an in vitro study. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 22 (11), 1257–1261. https://doi.org/10.5005/jp-journals-10024-3209 (2021).

Marra, J. et al. Effect of an acrylic resin combined with an antimicrobial polymer on biofilm formation. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 20, 643–648. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1678-77572012000500014 (2012).

Gendreau, L. & Loewy, Z. G. Epidemiology and etiology of denture stomatitis. J. Prosthodont. 20, 251–260. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-849X.2011.00698.x (2011).

Sanglard, D. & Odds, F. C. Resistance of Candida species to antifungal agents: molecular mechanisms and clinical consequences. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2, 73–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(02)00181-0 (2002).

Prasad, R. & Rawal, M. K. Efflux pump proteins in antifungal resistance. Front. Pharmacol. 5, 202. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2014.00202 (2014).

Selmecki, A., Forche, A. & Berman, J. Aneuploidy and isochromosome formation in drug-resistant Candida albicans. Science 313, 367–370. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1128242 (2006).

Mahmoud, D. A., Hassanein, N. M., Youssef, K. A. & Abou Zeid, M. A. Antifungal activity of different Neem leaf extracts and Nimonol against some important human pathogens. Braz J. Microbiol. 42, 1007–1016. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1517-83822011000300003 (2011).

Sharma, H. et al. Antifungal efficacy of three medicinal plants against oral Candida albicans: a comparative analysis. Indian J. Dent. Res. 27, 433–436. https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-9290.183135 (2016).

Kumar, S. & Pandey, A. K. Chemistry and biological activities of flavonoids: an overview. Sci. World J. 2013, 162750 https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/162750 (2013).

Chava, V. K., Manjunath, S. M., Rajanikanth, A. V. & Sridevi, N. The efficacy of Neem extract on four microorganisms responsible for causing dental caries. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 13, 769–772. https://doi.org/10.5005/jp-journals-10024-1227 (2012).

Alzohairy, M. A. Therapeutic role of Azadirachta indica (neem) and their active constituents in disease prevention and treatment. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2016, 7382506 https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/7382506 (2016).

Parida, M. M., Upadhyay, C., Pandya, G. & Jana, A. M. Inhibitory potential of Neem (Azadirachta indica Juss) leaves on dengue virus type-2 replication. J. Ethnopharmacol. 79, 273–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-8741(01)00395-6 (2002).

Hamid, S. K., Al-Dubayan, A. H., Al-Awami, H., Khan, S. Q. & Gad, M. M. In vitro assessment of the antifungal effects of Neem powder added to polymethyl methacrylate denture base material. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 11, e170–e178. https://doi.org/10.4317/jced.55649 (2019).

Islam, R. et al. Antimicrobial and antibiofilm activity of Neem (Azadirachta indica) against multidrug-resistant pathogens. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 20, 184. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-020-02987-7 (2020).

Pavela, R. Essential oils for the development of eco-friendly mosquito larvicides: a review. Ind. Crops Prod. 76, 174–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2015.06.050 (2015).

Sujatha, B. B., Antony, J. E., Nazeem, P. A. & Jeeva, S. Antibacterial and antifungal activities of Azadirachta indica (neem) root extract. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 6, 204–207 (2014).

Oliveira, R. A., De Paula, L. G., Vieira, C. H. & Silva Antifungal potential of Neem (Azadirachta indica) leaf extracts against alternaria spp. Braz J. Microbiol. 49, 243–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjm.2017.04.001 (2018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JMP performed experiments, analysed data, and wrote the initial manuscript. HMA assisted in performing experiments and contributed to writing manuscript. LS provided microbiologic assistance. MK supervised the project and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Philip, J.M., Mahalakshmi, K., Abraham, H.M. et al. Antifungal efficacy of Azadirachta indica and Ficus benghalensis extracts against azole resistant Candida albicans on denture resin. Sci Rep 15, 43567 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30708-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30708-9