Abstract

Drug-resistant epilepsy (DRE) lacks a reliable early warning system. This prospective study developed an early predictive model for DRE based on baseline serum metabolite levels. Serum samples were collected from 151 prospectively recruited patients with epilepsy. Patients were categorized into the DRE and non-drug-refractory epilepsy (NDRE) groups after a four-year follow up. After propensity score matching of baseline data, including age and sex, 32 patients with DRE and 89 with NDRE were recruited and split into training and test sets at random in a 2:1 ratio. Nontargeted metabolomics of the training set identified 215 significantly altered metabolites, primarily those involved in dysregulated lipid metabolism. Compared with the NDRE group, 39 metabolites were upregulated and 176 were downregulated in the DRE group. Pathway enrichment analysis highlighted perturbations in sphingolipid metabolism, choline metabolism, Linoleic acid metabolism, and alpha-Linolenic acid metabolism. A support vector machine model incorporating 11 metabolites and one clinical characteristic achieved an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.9396 and an independent test set AUC of 0.7437. This study provides a non-invasive, serum-based objective tool to identify the potential population of patients with DRE with good sensitivity and specificity and guide targeted metabolic therapies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Epilepsy is a prevalent chronic neurological disorder distinguished by the occurrence of unprovoked seizures and has a global prevalence of 0.5–1% in developed countries and significantly higher rates in developing countries1. Although medication can control seizures in most patients, some patients still experience uncontrollable seizures due to drug resistance. In 2010, the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) defined drug-resistant epilepsy (DRE) as the failure of two appropriately chosen and tolerated anti-seizure medication (ASM) regimens (monotherapy or polytherapy) to achieve freedom from seizure for more than 1 year2. Systematic reviews have estimated the prevalence at 30%, with an annual incidence of 15%3. Patients with DRE have a higher risk of premature mortality, neuropsychological impairment, and a significant reduction in quality of life4. Consequently, it is crucial to identify DRE in patients as soon as possible.

The mechanisms behind drug resistance in epilepsy are still unknown. Current diagnostic paradigms remain reactive and rely on the outcome of medical treatment rather than predictive biomarkers, which hinders early individualization and optimization of treatment for patients diagnosed with DRE5,6. Several models and predictors have been proposed to predict DRE, including clinical and biochemical markers such as age at onset, abnormal electroencephalogram (EEG), seizure type, initial frequency of seizures, family history of epilepsy, aberrant neuroimaging, levels of high mobility group box 1, and SCN1A polymorphisms7. However, there are currently no molecular biomarkers able to identify possible DRE populations early on with good sensitivity and specificity.

The measurement of small molecule concentrations in blood, urine, cerebrospinal fluid, and other biological matrices is known as metabolomics8,9. It offers data for ensuing “omics” technologies like proteomics and genomics. Metabolomics has become a significant method for the identification of disease biomarkers, characterized by its efficiency and high-throughput precision. It not only unravels intricate biological mechanisms but also serves as a reliable way to monitor therapeutic effects. Metabolomics is widely recognized as an effective approach to disease diagnosis, classification, staging, treatment planning, and prognostic evaluation10. In 2017, the ILAE classified “metabolic etiology” as one of six major etiological categories of epilepsy11. There are several subtypes of metabolic epilepsy, such as mitochondrial diseases, folinic acid-responsive seizures, and cerebral folate insufficiency12. Basic research and translational studies have shown that the relationship between cerebral metabolism and seizures is complicated and bi-directional and forms a harmful cycle that exacerbates the negative effects of seizures. Metabolic moleculars and enzymes have turned into appealing biological targets for preventing epileptic seizures and fostering recuperation, and metabolism-based therapy methods, such as high-fat antiepileptic ketogenic diets, have progressively gained traction13.

Therefore, this study aimed to elucidate the differences in baseline serum metabolomics between DRE and non-drug-refractory epilepsy (NDRE) through a prospective cohort study. Furthermore, this study aimed to clarify the material basis for the occurrence and progression of DRE from a metabolic perspective, thereby providing a biological foundation and novel insights for further investigation of the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying DRE. Additionally, a predictive model was developed utilizing the clinical traits and potential metabolites identified in the training cohort and subsequently confirmed in the test cohort.

Results

Participants’ clinical features and basic information

The study flow chart is displayed in Fig. 1. The clinical characteristics and demographic information of the study population are presented in Table 1. Other than the number of seizures prior to diagnosis, which also did not exhibit a statistically significant difference (P > 0.05), there were no statistically significant differences between the DRE and NDRE groups (P > 0.05). In the training cohort, the DRE group exhibited more frequent seizures before diagnosis than the NDRE group (P = 0.006). Additionally, the NDRE group exhibited greater levels of total cholesterol than the DRE group within the test cohort (3.97 vs. 3.44 mmol/L, P = 0.011), but they were still within the normal physiological range.

Flowchart of the study. After strict inclusion and exclusion criteria, 151 patients with epilepsy are prospectively recruited. Details of basic information, clinical characteristics, and serum samples of the patients are collected. They are interviewed through clinical visits or phone calls every six months for four years. According to the diagnostic criteria of DRE, the patients are divided into the DRE and NDRE groups. After propensity score matching of baseline data (sex and age), the DRE (n = 32) and NDRE groups (n = 89) are ultimately included, and they are then randomly assigned to the training and test sets at a 2:1 ratio. Identification of differential metabolites, pathway enrichment analysis, and predictive model construction are analyzed in the training set. This model is further validated using the test set. DRE, drug-resistant epilepsy; NDRE, non-drug-refractory epilepsy.

Metabolomic profiling and data quality assessment

Non-targeted metabolomic analysis was performed on the serum samples of 80 patients with epilepsy in the training set (55 patients with NDRE and 25 with DRE). Data pre-processing, including peak alignment and filtering based on the coefficient of variation (< 30% in quality control samples), was conducted using the XCMS package (v3.12.0). In total, 1,090 metabolites were retained for further analysis, comprising 597 positive and 493 negative ion metabolic modes (Supplementary Table S1). Hierarchical clustering of the metabolites revealed distinct metabolic signatures between the two groups (Fig. 2A). The metabolic characteristics of the epilepsy cohorts showed good consistency within groups, but little difference between the groups, according to the hierarchical clustering dendrogram (Fig. 2B). The principal component analysis (PCA) results demonstrated that the NDRE group exhibited tighter clustering than the DRE group, however the separation trend between the two groups was not clear. The first two principal components (PC1 and PC2) accounted for 22.0% variance (R2X [cum] = 0.220) (Fig. 3A). The PCA plot including QC samples demonstrated that the QC samples clustered closely together, indicating high repeatability and consistency of the analytical process (Supplementary Fig. S1A). Plot of partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) results showed a more pronounced separation trend between patients with NDRE and DRE [R2X(cum) = 0.172, R2Y(cum) = 0.627, Q2(cum) = -0.121] (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, the plot of orthogonal PLS-DA (OPLS-DA) results also showed a separation trend between the patients with NDRE and DRE [R2X(cum) = 0.172, R2Y(cum) = 0.627, Q2(cum) = -0.197] (Fig. 3C). However, the results of permutation test (n = 200) indicated that the initial model failed to accurately predict the classification of new individuals [Q2(cum)= -0.197, pQ2(cum) = 0.305] (Supplementary Fig. S1B). Consequently, we reduced the dimensionality of the variables employed in the OPLS-DA model by including only differential metabolites instead of all metabolites [R2X(cum) = 0.414, R2Y(cum) = 0.467, Q2(cum) = 0.199] (Supplementary Fig. S1C, D). Then the model was applied to predict the classification of the test samples. The results demonstrated that the prediction accuracy of the retrained model on the test set reached 0.7317, indicating good generalization ability. However, the specificity of the model (0.7941) was substantially higher than its sensitivity (0.4286), indicating a relatively limited capacity to correctly identify true RE. Moreover, only 30% of the samples predicted as RE were confirmed to be actual RE cases (low precision). (Supplementary Table S2).

Serum metabolomic profiles and multivariate analysis of metabolic separation between the NDRE and DRE groups. A Each metabolite’s relative expression across all samples is displayed in the heat map of the overall metabolite cluster. The expression is higher when the color is redder. The expression is lower when the color is bluer. B Hierarchical clustering dendrogram of epilepsy cohorts. Closer and shorter cluster trees represent higher similarity between samples. DRE, drug-resistant epilepsy; NDRE, non-drug-refractory epilepsy.

Multivariate analysis of metabolic separation between the NDRE and DRE groups and identification of differentially abundant metabolites. A PCA score plot showing dispersion of drug-resistant epilepsy (DRE) and non-resistant (NDRE) groups along PC1. B Plot of PLS-DA results shows a separation trend between patients with NDRE and DRE. C Plot of OPLS-DA results also shows a separation trend between patients with NDRE and DRE. D Histogram graph of the number of differential metabolites shows 109 metabolites with significant differences between groups. E The volcano plot visually illustrates the distribution and change trend of upregulated and downregulated metabolites in the two groups. DRE drug-resistant epilepsy, NDRE non-drug-refractory epilepsy, PCA principal component analysis, PLS-DA partial least squares discriminant analysis, OPLS-DA orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis, VIP variable importance in projection.

Differential metabolite identification

In all, 1,090 metabolites were found and quantified. Among these, 215 metabolites with significant differences (variable importance in projection [VIP] > 1, P < 0.05) between the groups were screened, including 105 lipid metabolites, 20 steroid metabolites, 15 amino acids, 4 organic acids, and 71 other metabolites (Fig. 3D, Supplementary Table S3). The volcano plot (Fig. 3E) illustrates differential metabolites that are upregulated and downregulated based on the fold-change in metabolite levels in the DRE group relative to those in the NDRE group. In order to illustrate the general trend and extent of variation in metabolite quantitative values, a Z-score plot was also created using values derived from the relative content of metabolites (Supplementary Fig. S2)14. According to the heat map of differential metabolites (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table S2), 39 metabolites, such as Isoleucyl-Tryptophan, PC(18:3(6Z,9Z,12Z)/22:5(4Z,7Z,10Z,13Z,16Z)), PE-NMe2(16:0/20:4(5Z,8Z,11Z,14Z)), PS(18:3(9Z,12Z,15Z)/20:0) and Tauroursodeoxycholic acid, were up-regulated in the DRE group. Conversely, 176 metabolites, including PC(16:0/18:2(9Z,12Z)), Threoninyl-Proline, and Tuberoside, were downregulated in the DRE group. Furthermore, the distribution features of the 215 differential metabolites between the DRE and NDRE groups were visually represented by the rain cloud plot (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Hierarchical clustering of differentially abundant metabolites between the NDRE and DRE groups. Samples are represented by columns, metabolites by rows, and the sample cluster tree is at the top, followed by the different metabolite cluster tree on the left. The gradient color represents the quantitative value’s magnitude; the higher the expression, the redder the color, and the lower the expression, the bluer the color. DRE, drug-resistant epilepsy; NDRE, non-drug-refractory epilepsy.

Pathway enrichment analysis

The metabolites that showed notable alterations between the two groups were subjected to Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis. A total of 16 enriched metabolic pathways were identified, with the top four being sphingolipid metabolism (P = 0.002), choline metabolism (P = 0.002), Linoleic acid metabolism (P = 0.016), and alpha-Linolenic acid metabolism (P = 0.035) (Fig. 5A, Supplementary Table S4). Additionally, we analyzed how different metabolites affected the two groups’ metabolic pathways in relation to one another (Fig. 5B, Supplementary Table S5). Among these, sphingolipid metabolism was the most affected (impact > 0.1 and P < 0.05), however there was no significant pathway after FDR (False Discovery Rate) correction. When comparing the DRE group with the NDRE group, the enrichment analysis network diagram showed that most of the differential metabolites in these metabolic pathways were considerably downregulated (Fig. 5C).

Pathway enrichment analysis of different metabolites between the DRE and NDRE groups. A The enriched metabolic pathways of differential metabolites are displayed in the enrichment analysis histogram. (B) The relative impact of differential metabolites on metabolic pathways in the two groups is displayed in a KEGG topological bubble diagram. (C) A visual representation of the regulatory network of metabolic pathways and differential metabolites is provided by the KEGG pathway network diagram. KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; DRE, drug-resistant epilepsy; NDRE, non-drug-refractory epilepsy.

Predictive model construction

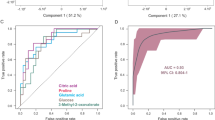

Through the integrated feature selection process, based on differential metabolites and one clinical characteristic, we screened out a marker composed of PE-NMe2(18:3(6Z,9Z,12Z) /20:5(5Z,8Z,11Z,14Z,17Z)), 5,8,11-Dodecatriynoic acid, Cyclocalopin C1, LysoPC(24:0), PC(18:1(9Z) /18:1(9Z)), 5,8,11-Dodecat-riynoic acid, 13-Nor-6-eremophilene-8,11-dione, Hovenidulcioside A2, 2,6-Dimethyl-7-octene-1,6-diol 8-O-glucoside, Myricanene B 5-[arabinosyl-(1->6)-glucoside] and 7-Methylxanthine and one clinical characteristic (number of seizures before diagnosis) (Supplementary Table S6). Based on the contributions of these variables to the predicted outcomes, we calculated the feature importance scores (Fig. 6A). Based on these biomarkers, the support vector machine (SVM) machine-learning algorithm was used to construct the prediction model. In the training cohort, DRE’s probability of disease (POD) index was greater than NDRE’s, according to the metabolite marker set (Fig. 6B). The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) constructed using the training set showed that the AUC was 0.9396 and the 95% confidence interval (CI) was 0.8827–0.9966 (P < 0.0001). Furthermore, its threshold was 0.4762 and its specificity/sensitivity was 0.8800/0.9273 (Fig. 6C). The precision-recall (PR) curve had an area under the precision-recall curve (AUPRC) of 0.9003 in the train cohort (Fig. 6D). In the test cohort, DRE’s probability of disease (POD) index was also greater than NDRE’s (Fig. 6E). The ROC constructed with the test set showed that the AUC was 0.7437 and the 95% CI was 0.5353–0.9521 (P = 0.0446). Furthermore, its threshold was 0.4762, with a specificity of 0.8235 and a sensitivity of 0.5714 (Fig. 6F). The PR curve had an AUPRC of 0.4975 in the test cohort (Fig. 6G). In constructing prediction model, we also explore other classification models, including random forest (RF), eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM). To comprehensively assess model performance, additional evaluation metrics including accuracy (ACC) and F1 score were computed (Supplementary Table S7). While several models achieved high training accuracy, the SVM demonstrated the most robust performance on the test set, achieving the highest F1 score (0.4706) and AUPRC (0.4974), along with a well-balanced trade-off between precision and recall. Notably, the minimal performance discrepancy between the training and test sets for SVM suggests a low propensity for overfitting and superior generalization capability. Based on these consistent and favorable results, we selected SVM as the optimal model. These findings suggest that DRE can be predicted using particular serum metabolites.

Predictive model construction and assessment. A Variable importance in the model. B The POD index of DRE is greater than that of NDRE in the training cohort. C The ROC curve has an AUC of 0.9396 (95% CI 0.8827–0.9966) between DRE and NDRE in the train cohort. D The PR curve had an AUPRC of 0.9003 in the train cohort. E The POD index of DRE is greater than that of NDRE in the test cohort. F The ROC curve has an AUC of 0.7437 (95% CI 0.5353–0.9527) in the test cohort. G The PR curve had an AUPRC of 0.4975 in the test cohort. POD probability of disease, ROC receiver operating characteristic, AUC area under curve, CI confidence interval, PR precision-recall, AUPRC area under the precision-recall curve, DRE drug-resistant epilepsy, NDRE non-drug-refractory epilepsy.

Discussion

Currently, drug resistance is a pressing problem in the treatment of epilepsy since it is associated with high mortality, significant burden, severe psychosocial dysfunction, and a lower quality of life. Developing reliable early warning system that could help clinicians identify people with DRE is therefore critically important. Although numerous predictors and risk factors have been identified, including clinical characteristics and biochemical indicators with some epigenetic and genetic markers, their sensitivity and specificity remain poor. To date, there has been no effective early warning model for DRE. Enzymes and metabolic substrates have become desirable molecular targets for promoting recovery and preventing epileptic seizures13. The ability of small-molecule serum metabolites to penetrate the blood-brain barrier and potentially reflect biological processes taking place in the central nervous system makes them an excellent clinical diagnostic medium. A deeper exploration of the baseline metabolic characteristics and construction of an early warning system for patients with DRE could assist clinicians in developing therapy plans and offer novel ideas for the creation of successful anti-epilepsy strategies.

In this prospective cohort study, we comprehensively investigated the baseline serum metabolomic characteristics of patients with epilepsy. Using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), 1,090 metabolites were found and quantified using non-targeted metabolic analysis. The DRE and NDRE groups’ early serum metabolite profiles were compared, and 215 metabolites—the majority of which were lipids—with notable distinctions between the groups (VIP > 1, P < 0.05) were identified. This is consistent with previous studies that have found that patients with DRE have lipid and amino acid metabolic disorder15,16,17. We further conducted KEGG enrichment analysis and found that it mainly involved pathways including sphingolipid metabolism, choline metabolism, Linoleic acid metabolism, and alpha-Linolenic acid metabolism. The majority of the differential metabolites in these metabolic pathways were considerably downregulated in the DRE group when compared to the NDRE group, according to our mapping of the differential metabolites to the respective metabolic pathways. In addition, by integrating untargeted metabolomics with machine learning algorithms, we further evaluated the predictive model’s effectiveness in the test cohort after identifying a set of 11 metabolites and one clinical feature. The model effectively predicted the early onset of DRE with an AUC of 0.9396 in the train cohort and 0.7437 in the independent testing cohort. These metabolic dysregulation phenomena observed in patients with DRE are consistent with the evidence linking metabolic dysfunction to neuronal hyperexcitation and neuroinflammation.

We observed that, compared with patients with NDRE, the levels of metabolites involved in sphingolipid metabolism were decreased in patients with DRE. Notably, sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), a bioactive sphingolipid metabolite, plays a pivotal role in modulating essential neurophysiological processes, including neuronal development, differentiation, migration, and survival18. S1P can decrease neuronal apoptosis through improving mitochondrial function and structural damage, according to mechanistic studies using both in vivo and in vitro models. This improves the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral problems linked to epilepsy and helps control epileptic seizures19.

Another early metabolic dysregulation observed in patients with DRE is associated with choline metabolism. In a study using magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging and thermometry (MRSI-t) in temporal lobe epilepsy patients with depressive symptoms, elevated choline/creatine ratios were detected in the left temporal lobe and bilateral frontal lobes20. However, in a pentylenetetrazol (PTZ)-kindled rat epilepsy model, choline levels were found to be reduced in the cerebellum and hippocampus21. Supplementation with choline in epileptic rats has been shown to confer neuroprotective effects and improve hippocampal memory function22,23. Furthermore, one study demonstrated that lipoic acid enhances memory in epileptic rats by increasing the activities of hippocampal choline acetyltransferase and acetylcholinesterase24. This also supports the significance of the cholinergic system in modulating neuronal excitability and synaptic plasticity25.

Furthermore, both linoleic acid metabolism and alpha-linolenic acid metabolism were identified as enriched metabolic pathways under DRE conditions. One study has shown that epilepsy patients exhibit lower levels of metabolites, including linoleic acid, compared to healthy individuals26. In children with epilepsy, reduced levels of linoleic acid methyl ester metabolites have been also observed27. Additionally, untargeted plasma metabolomic analyses in patients with DRE and infantile epileptic spasms syndrome have revealed significant enrichment of the linoleic acid metabolism pathway in these populations28,29. Evidence from in vivo animal studies, clinical trials, and in vitro studies suggests that linoleic acid may reduce seizure frequency and exert anticonvulsant effects30,31. At the mechanistic level, one study involving mouse models and cell experiments indicated that linoleic acid might downregulate the JAK2/STAT3 pathway, thereby contributing to the reduction of seizure frequency32. Moreover, it has been proposed that the ratio of paraxanthine to linoleate (18:2n6) could mediate the causal relationship between CD64 expression on CD14⁻CD16⁻ immune cells and epilepsy, with an intermediate Mendelian randomization (MR) mediation effect estimated at 5.05%33.

Thus, this prospective cohort study analyzed the baseline metabolic characteristics of DRE and provided a non-invasive, serum-based tool for the early identification of the potential population with DRE. These findings enhance our understanding of the metabolic mechanisms underlying DRE, provide new ideas for targeted metabolic therapy, aid clinicians in facilitating early personalized treatment strategies, and ultimately alleviate the burden on patients with epilepsy.

There are several drawbacks on this study. First, the results of multivariate data analysis, including PCA, PLS-DA and OPLS-DA were not considered satisfactory. The relatively limited sample size, compounded by the absence of strict patient stratification such as medication use, may have introduced uncontrolled variability, thereby limiting the statistical power and reliability of our findings. Multicenter studies with larger sample sizes would be more conducive to elucidating the clinical significance of these metabolites. Second, although untargeted metabolomics was employed to describe early metabolite characteristics in patients with DRE and NDRE, absolute quantification of candidate metabolites could not be performed, which lacks the reliability provided by targeted metabolomics analysis. Finally, although we identified several metabolites and metabolic pathways associated with DRE development, more investigation is needed to fully understand the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms.

Materials and methods

Research program and participants

Between 2022 and 2025, this prospective cohort study was carried out at the Epilepsy Center of the Neurology Department of Zhengzhou University’s First Affiliated Hospital. The inclusion criteria for patients with confirmed epilepsy were as follows: (1) one unprovoked (or reflex) seizure and a probability of additional seizures comparable to the general recurrence risk (at least 60%) following two unprovoked seizures over the following ten years; (2) at least two unprovoked (or reflex) seizures that occur more than 24 h apart; and (3) a diagnosis of epilepsy syndrome. The exclusion criteria for patients with epilepsy were as follows: (1) have received antibiotics, probiotics, prebiotics, vitamin, protein, or unsaturated fatty acids within the last three months; (2) a history of autoimmune disorders, including rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, multiple sclerosis, and neuromyelitis optica; (3) current or past history of malignancy and gastrointestinal surgery; (4) a history of neurological or psychiatric disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, AD, anxiety disorder, depression, autism spectrum disorder, schizophrenia; (5) have other metabolic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and metabolic syndrome; (6) undergoing irregular ASM therapy and poor compliance.

A prospective cohort was established in 2021, and 151 patients with epilepsy were recruited. After these participants were recruited, we collected their basic information, clinical characteristics, and serum samples, including clinical data, laboratory and imaging examinations, and EEG. They were interviewed through clinical visits or phone calls every six months for four years. At each follow-up, information on seizure occurrence, medication use, medication adherence and changes, and potential adverse reactions were collected. In addition, patients were required to contact the treating physician within a few days of experiencing a seizure. Based on the DRE diagnostic criteria, patients were split into DRE and NDRE groups2. After propensity score matching of baseline data such as the sex and age, the DRE (n = 32) and NDRE groups (n = 89) were ultimately included and then randomly assigned to the training and test sets at a 2:1 ratio.

Serum sample collection

Venous blood collection was performed in all patients under fasting condition. Following collection into a serum tube (BD, Oxford, UK), venous blood was centrifuged at 4 °C and 10,000 rpm for 10 min and stored at -80 °C. For analysis, the samples were thawed at 4 °C. Subsequently, 400 µL of methanol containing 0.02 mg/mL internal standard (L-2-chlorophenylalanine) was added to a 100 µL aliquot of the sample in a 1.5 mL tube. The mixture was vortexed for 30 s and extracted ultrasonically for 30 min at 5 °C (40 kHz). After incubation at -20 °C for 30 min, the samples were centrifuged at 4 °C and 13,000 g for 15 min. The supernatant was then moved to an LC-MS container for examination. A quality control (QC) sample was also made by pooling a 20 µL aliquot of supernatant from each sample.

LC–MS experiment

A tandem ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-Fourier transform mass spectrometry system (UHPLC-Q Exactive HF-X, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) was used to conduct the LC-MS analysis. The chromatographic column was an ACQUITY UPLC HSS T3 (100 mm × 2.1 mm internal diameter, 1.8 μm; Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA). The mobile phases were as follows: (A) 5% H2O / 5% ACN (with 0.1% formic acid); (B) 47.5% ACN / 47.5% IPA / 5% H2O (with 0.1% formic acid). The sample injection volume was 2 uL, and the column temperature was maintained at 40 °C. After electrospraying these materials, mass spectrum data were obtained using both the positive and negative ion scanning modes. Equal quantities of each sample extract were combined to create QC samples, which were then processed in the same way as the analytical samples. Every five to fifteen analytical samples, a QC sample was analyzed to monitor the system’s stability.

Chromatogram of total ions

The mass spectrometer continually received the chromatographically separated sample’s constituents, and the mass spectrum was continuously scanned in order to gather data. Each scan produced a mass spectrum, and the total ion current intensity was calculated by adding the ion intensities in each mass spectrum. The ordinate was the sum of the ionic strengths, and the abscissa was the total ion chromatograms for time. The total ion chromatograms of the QC samples in both positive and negative ion modes were used to evaluate the detection performance.

Identification of metabolites

Raw data for baseline filtering, peak alignment, integration, retention time correction, and peak identification were imported using Progenesis QI (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA). Ultimately, a data matrix was obtained that included data on peak intensity, mass-to-charge ratio, and retention duration. The metabolic database was compared with the MS and MS/MS mass spectrum data. The secondary mass spectrum matching score was used to identify the metabolites, and the MS mass error was set to be less than 10 ppm. The primary metabolite identification databases include popular public and self-built databases including MetaboAnalyst (https://www.metaboanalyst.ca/), the Human Metabolome Database (https://hmdb.ca/) and Metabolite Link (https://metlin.scripps.edu/).

Multivariate data analysis

We apply autoscaling to the data, that is, Z-score normalization to the data, which will transform the data into a data set with mean 0 and variance 1. The dimensionality reduction of the sample data was achieved by PCA, PLS-DA, and OPLS-DA using the “Ropls” package (v1.34.0) of R 4.4.1 (https://www.r-project.org/). Permutation tests were used to overfit the model; Q2 shows the model’s predictive power, and R2X and R2Y indicate the model’s interpretation rates for the X and Y matrices, respectively. A better model fit and a more accurate classification of the training set samples into their original categories are indicated by values nearer one. The VIP was computed using OPLS-DA dimensionality reduction, and the P-value was ascertained using statistical testing. To help identify marker metabolites, the fold-change was calculated to assess the impact and explanatory capacity of each metabolite’s content on sample categorization and discrimination. When the P value was < 0.05 and the VIP value was > 1, metabolites were considered statistically significant. Additionally, we reduced the dimensionality of the variables employed in the OPLS-DA model by including only statistically significant metabolites instead of all metabolites. Then the model was applied to predict the classification of the test samples to obtain the predicted grouping of these samples. And the corresponding accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, precision, F1 score and other results.

Advanced analysis

MetaboAnalystR (v4.0.0) was used to perform KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of the differential metabolite list (KEGG PATHWAY Database, https://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html)34. The hypergeometric distribution test served as the foundation for the enrichment analysis. The Relative Betweenness Centrality metric was used for the topological study.

Construction of predictive models

This project utilized the mlr3 framework (mlr3verse v0.3.1) to implement the training and evaluation of the machine learning models. The ensemble feature selection (EFS) method was applied for feature selection. Considering that the DRE and NDRE groups in the training set differed significantly in one clinical parameter (number of seizures before diagnosis) and that previous studies reported that the number of seizures before diagnosis was a predictor of DRE, we screened it through EFS along with metabolites. The data underwent preprocessing steps, including the removal of low-variance features and imputation of missing values, followed by a hierarchical stratified division into the training (2/3) and test (1/3) sets. Hyperparameters were optimized via random search, and the model performance was rigorously assessed using 5-fold cross-validation as well as independent testing. The feature importance was analyzed using algorithm-specific metrics, and repeatability was ensured through parallel computing, fixed random seeds, and modularized pipelines. The disease probability (POD) index of the training set and the validation set was calculated by the determined best set. The POD index is the ratio of the number of randomly generated decision trees predicted to be DRE to the number of decision trees predicted to be NDRE. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used to illustrate the results, highlighting the model’s key predictive attributes and capacity for generalization. The “pROC” package (v1.18.5) was used to construct the ROC curve35, and the ggplot2 package (v3.5.1) was used to draw the graphics. To determine the optimal prediction model, we simultaneously constructed four distinct machine learning models: XGBoost, RF, SVM, and LightGBM. Each model underwent hyperparameter optimization via cross-validation to maximize the cross-validated AUC. Model performance was evaluated on both the cross-validation set and an independent test set, using multiple metrics including AUC, ACC, classification error rate (CE), AUPRC, and F1 score. The final model was selected based on its comprehensive performance on the independent test set.

Statistical analysis

The t-test is used to compare the two groups’ continuous variables, which have a normal distribution and are displayed as the mean ± standard deviation. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare groups, and continuous variables that were not normally distributed are displayed as medians and interquartile ranges. To compare categorical variables between the two groups, the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test was employed. The Wilcox test/t test package (v4.4.0) and SPSS V.27 for Windows (IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) were used for statistical analyses. The threshold for statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Conclusions

In this prospective cohort study, we analyzed the baseline serum metabolic signatures between patients with DRE and NDRE and developed a non-invasive, serum-based predictive model for identifying the potential population of patients with DRE at an early stage, with a cross-validated AUC of 0.810 and an independent test set AUC of 0.794. These findings enhance our understanding of the metabolic mechanisms underlying DRE, provide new ideas for targeted metabolic therapy, aid clinicians in facilitating early personalized treatment strategies, and ultimately alleviate the burden on patients with epilepsy.

Data availability

The serum metabolomics data sets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

Banerjee, P. N., Filippi, D., Allen, W. & Hauser The descriptive epidemiology of epilepsy—a review. Epilepsy Res. 85 (1), 31–45 (2009).

Kwan, P. et al. Definition of drug resistant epilepsy: consensus proposal by the ad hoc task force of the ILAE commission on therapeutic strategies. Epilepsia 51 (6), 1069–1077 (2010).

Kalilani, L. et al. The epidemiology of drug-resistant epilepsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epilepsia 59 (12), 2179–2193 (2018).

Kwan, P., Schachter, S. C. & Brodie, M. J. Drug-resistant epilepsy. N Engl. J. Med. 365 (10), 919–926 (2011).

Janmohamed, M., Brodie, M. J. & Kwan, P. Pharmacoresistance—epidemiology, mechanisms, and impact on epilepsy treatment. Neuropharmacology 168, 107790 (2020).

Anyanwu, C. & Motamedi, G. K. Diagnosis and surgical treatment of Drug-Resistant epilepsy. Brain Sci. 8(4). 49 (2018).

Li, Z. et al. Potential clinical and biochemical markers for the prediction of drug-resistant epilepsy: a literature review. Neurobiol. Dis. 174, 105872 (2022).

Shao, Y. & Le, W. Recent advances and perspectives of metabolomics-based investigations in parkinson’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 14 (1), 3 (2019).

Bhargava, P. & Anthony, D. C. Metabolomics in multiple sclerosis disease course and progression. Mult Scler. 26 (5), 591–598 (2020).

Goodacre, R. et al. Metabolomics by numbers: acquiring and Understanding global metabolite data. Trends Biotechnol. 22 (5), 245–252 (2004).

Scheffer, I. E. et al. ILAE classification of the epilepsies: position paper of the ILAE commission for classification and terminology. Epilepsia 58 (4), 512–521 (2017).

Lin, L. et al. Treatment, therapy and management of metabolic epilepsy: a systematic review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19(3). 871 (2018).

Rho, J. M. & Boison, D. The metabolic basis of epilepsy. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 18 (6), 333–347 (2022).

Rao, G., Sui, J. & Zhang, J. Metabolomics reveals significant variations in metabolites and correlations regarding the maturation of walnuts (Juglans regia L.). Biol. Open. 5 (6), 829–836 (2016).

Wu, H. C. et al. Altered metabolomic-genomic signature: a potential noninvasive biomarker of epilepsy. Epilepsia 58 (9), 1626–1636 (2017).

Detour, J. et al. Metabolomic characterization of human hippocampus from drug-resistant epilepsy with mesial temporal seizure. Epilepsia 59 (3), 607–616 (2018).

Zhang, H. et al. Untargeted lipidomic analysis of human hippocampus for temporal lobe epilepsy with hippocampal sclerosis. Epilepsy Res. 161, 106299 (2020).

van Echten-Deckert, G. The role of sphingosine 1-phosphate metabolism in brain health and disease. Pharmacol. Ther. 244, 108381 (2023).

Ben, X. et al. Metabolomics-driven exploration of sphingosine 1-phosphate mechanisms in refractory epilepsy. Neurobiol. Dis. 212, 106953 (2025).

Oates, M. et al. An exploratory study of brain temperature and choline abnormalities in temporal lobe epilepsy patients with depressive symptoms. Epilepsia Open 8 (4), 1541–1555 (2023).

Carmody, S. & Brennan, L. Effects of pentylenetetrazole-induced seizures on metabolomic profiles of rat brain. Neurochem. Int. 56 (2), 340–344 (2010).

Lee, S. H. et al. Late treatment with choline alfoscerate (L-alpha glycerylphosphorylcholine, α-GPC) increases hippocampal neurogenesis and provides protection against seizure-induced neuronal death and cognitive impairment. Brain Res. 1654, 66–76 (2017).

Wong-Goodrich, S. J. E. et al. Water maze experience and prenatal choline supplementation differentially promote Long-Term hippocampal recovery from. Seizures Adulthood Hippocampus. 21 (6), 584–608 (2011).

de Freitas, R. M. Lipoic acid increases hippocampal choline acetyltransferase and acetylcholinesterase activities and improvement memory in epileptic rats. Neurochem. Res. 35 (1), 162–170 (2010).

Picciotto, M. R., Higley, M. J. & Mineur, Y. S. Acetylcholine as a neuromodulator: cholinergic signaling shapes nervous system function and behavior. Neuron 76 (1), 116–129 (2012).

Wang, D. et al. GC-MS-Based metabolomics discovers a shared serum metabolic characteristic among three types of epileptic seizures. Epilepsy Res. 126, 83–89 (2016).

Chen, Y. et al. Screening of metabolic markers in pediatric epilepsy disorders. J. Transl. Med. 23 (1), 1018–1018 (2025).

Chen, J. et al. Integrated analysis of proteomics and metabolomics in infantile epileptic spasms syndrome. Sci. Rep. 15(1). 4457 (2025).

Guo, H. L. et al. Integrating metabolomics and lipidomics revealed a decrease in plasma fatty acids but an increase in triglycerides in children with drug-refractory epilepsy. Epilepsia Open 8 (2), 466–478 (2023).

1, A. Y. T., Burnham, W. M. & Auvin, S. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and epilepsy. Epilepsia 51(8). 1348-1358 (2010).

Pourmasoumi, M. et al. Association of Omega-3 fatty acid and epileptic seizure in epileptic patients: a systematic review. Int. J. Prev. Med. 9, 36–36 (2018).

Zeng, X. et al. α-Linolenic acid ameliorates pentylenetetrazol-induced neuron apoptosis and neurological impairment in mice with seizures via down-regulating JAK2/STAT3 pathway. Br. J. Nutr. 132 (1), 1–12 (2024).

Chen, J. et al. Causal relationship between immune cells and epilepsy mediated by metabolites analyzed through Mendelian randomization. Sci. Rep. 14(1). 19644 (2024).

Xia, J. & Wishart, D. S. Web-based inference of biological patterns, functions and pathways from metabolomic data using metaboanalyst. Nat. Protoc. 6 (6), 743–760 (2011).

Robin, X. et al. pROC: an open-source package for R and S + to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinform. 12, 77 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to all the kind volunteer participants in the study.

Funding

This study was sponsored by grants from Key project of Henan Provincial Natural Science Foundation (HNSZRKXJJZDXM2023019), Key Scientific Research Project of Henan Province University (24A320031), Henan Province Science and Technology Project (242102311134), Henan University Science and Technology Innovation Team Support Program (25IRTSTHN040).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, ZR and YJ; investigation, WK, QH, MC and LX; data curation, WK, QH, ZZ, RL and YM; writing—original draft preparation, WK, ZR and YJ; visualization, YF; supervision, ZR and YJ; project administration, ZR and YJ; funding acquisition, ZR and YJ. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declarations

The Institutional Review Board of Zhengzhou University’s First Affiliated Hospital gave its approval to this study (No. 2021-KY-0574-002). The Helsinki Declaration and the Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice were followed when conducting the study. Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Consent to participate/consent to publish

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kang, W., Han, Q., Chen, M. et al. Alterations in serum metabolomics predict drug-resistant epilepsy. Sci Rep 16, 1003 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30741-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30741-8