Abstract

Tumor hypoxic microenvironments limit the generation efficiency of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in photodynamic therapy (PDT) and exacerbate immune suppression, severely restricting its clinical efficacy. To overcome this bottleneck, this study developed a bio-organic hybrid delivery system based on oxygen-producing cyanobacteria and nano-photosensitizers (PCC7942@ICG-NPs), which synergistically enhances efficacy through in situ oxygen delivery and augment ROS. Specifically, indocyanine green (ICG) was loaded onto bovine serum albumin (BSA) via hydrophobic interactions to form stable nanoparticles (ICG-NPs), and the positively charged surface of the nanoparticles enabled efficient self-assembly with the oxygen-producing cyanobacterium PCC7942 by electrostatic interactions. Upon near-infrared laser activation, the cyanobacteria continuously release molecular oxygen through photosynthesis, significantly increasing the local tumor oxygen partial pressure (pO₂), which potentiates ICG-mediated photodynamic therapeutic efficacy and boosts ROS production, simultaneously improving the tumor hypoxic microenvironment and triggering systemic antitumor immunity. This work provides an innovative strategy to overcome tumor hypoxia and combined PDT therapy, showing significant clinical translation potential.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, the incidence of cancer has steadily increased, establishing it as one of the leading causes of mortality worldwide1. Conventional treatment strategies, primarily involving surgical resection in combination with radiotherapy and chemotherapy, face substantial challenges, including high postoperative complication rates, systemic toxicity, and multidrug resistance2,3. With recent advances in medical science, various emerging therapeutic approaches—such as photothermal therapy, photodynamic therapy, and oncolytic virotherapy—have attracted considerable attention4,5,6. Among these, photodynamic therapy (PDT) has demonstrated considerable clinical potential. Offering advantages such as non-invasiveness, spatiotemporal controllability, and low systemic toxicity7,8,9. Its core mechanism involves the accumulation of photosensitizers at the tumor site, followed by laser irradiation to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), ultimately leading to cell death. However, PDT continues to face major challenges, including insufficient targeting, limited stability of photosensitizers, and the hypoxic tumor microenvironment10,11. Therefore, the integration of photosensitizers and oxygen-supplying agents into a single nanodrug delivery system is considered essential for overcoming these limitations12,13.

Cyanobacteria, particularly PCC7942, possess a unique advantage in tumor oxygenation regulation due to their capacity to continuously produce oxygen via photosynthesis under light exposure, thereby effectively alleviating the hypoxic tumor microenvironment and creating favorable conditions for PDT14,15. To leverage this property and address clinical challenges associated with PDT16,17,18, we constructed a bioplatform by combining PCC7942 with nano-photosensitizers. Specifically, the hydrophobic cavity of bovine serum albumin (BSA) was utilized to encapsulate the near-infrared photosensitizer indocyanine green (ICG), forming stable nanoparticles (ICG-NPs), which subsequently self-assembled with PCC7942 through electrostatic interactions to generate the composite system PCC7942@ICG-NPs (Fig. 1A). Upon intratumoral administration, the oxygen generated by PCC7942 not only alleviated tumor hypoxia but also provided a sufficient oxygen supply to support ROS generation during ICG-mediated photodynamic reactions19,20. Moreover, the laser irradiation required for ICG activation simultaneously supported the photosynthetic activity of PCC7942 (Fig. 1B)21,22. This synergistic strategy enhanced the therapeutic efficacy of ICG, further amplified the antitumor immune response, and offered innovative insights and potential clinical applications for PDT-based cancer therapy.

Materials and methods

Materials

All reagents and chemicals employed in this study were of analytical grade and purchased from commercial suppliers. Bovine serum albumin (BSA) was obtained from Guangzhou Saiguo Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China), while indocyanine green (ICG) was purchased from Keyuan Biochemical Co., Ltd. (Shandong, China). DL-dithiothreitol (DTT) was supplied by Shanghai Merryer Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride) and the reactive oxygen species (ROS) detection kit were obtained from Dalian Meilun Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Dalian, China). Monoclonal antibodies against CD11c, CD80, CD86, CD4, and CD8 were provided by BioLegend (San Diego, CA, USA). The cyanobacterial strain Synechococcus elongatus PCC7942 (PCC7942) was kindly provided by the Freshwater Algae Culture Collection of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (China). Murine 4T1 breast carcinoma cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and maintained at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO₂.

Female Balb/c mice (aged 8–10 weeks, 18–22 g) were sourced from Shenyang Pharmaceutical University’s Animal Center (Liaoning, China). All mice were maintained under controlled conditions (25 ± 1 °C, 12 h/12 h light/dark cycle) with ad libitum access to standard rodent chow and drinking water. Tribromoethanol was used as an anesthetic to anesthetize mice to alleviate the pain caused to them during the experiment.

Preparation of ICG-NPs

First, carefully mix the ICG, BSA, and DTT solutions with 1 mL of deionized water. Ensure that all components are fully dissolved before proceeding.As you prepare the mixture, slowly introduce absolute ethanol in measured increments, ensuring each addition is fully incorporated before proceeding to the next. Maintain a consistent stirring motion throughout this process for an hour.Next, we will centrifuge the mixture at a speed of 3000 revolutions per minute for a duration of 10 min to eliminate any precipitates and impurities that may have formed during the process.Following the incubation process, the liquid phase that remained after the particles settled contained ICG-NPs.Subsequently, transfer the liquid phase into an ultrafiltration device equipped with a 30-kDa molecular weight cutoff and subject it to a two-step centrifugation process.To achieve high-purity ICG-NPs, we conducted experiments for 10 min each cycle, ensuring the complete separation of impurities.

Preparation of PCC7942@ICG-NPs

Centrifuge 1 mL of PCC7942 (OD₆₀₀ = 1.0 corresponding to approximately 1 × 10⁹ CFU/mL) at 3000 rpm for 10 min to remove the culture medium, and then reconstitute it to a volume of 1 mL. Mix the impurity-removed PCC7942 with 1 mL of the above-prepared ICG-NPs under continuous stirring for 1 h to prepare PCC7942@ ICG-NPs.

Characterization of ICG-NPs and PCC7942@ICG-NPs

ICG-NPs and PCC7942@ICG-NPs were analyzed for their size and zeta potential with a Zetasizer (Malvern, UK), and their morphology was visualized through transmission electron microscopy (JEOL, Japan).

Stability assays

1 mL of ICG-NPs was uniformly dispersed in 9 mL of PBS solution (pH 7.4) containing 10% FBS. The suspension was incubated in a shaker at 37 °C with gentle agitation (100 rpm). At predetermined time points, samples were collected and transferred into cuvettes for size measurement using a Malvern Zetasizer particle size analyzer. The particle size of ICG-NPs was recorded at each time point, and three independent measurements were performed for each group.

Binding efficiency of ICG-NPs to PCC7942

The absorbance of ICG-BSA nanoparticles was measured at 790 nm. ICG-NPs were mixed with Synechococcus elongatus PCC7942 to prepare the PCC7942@ICG-NPs suspension. After incubation, the ICG-NPs bound to PCC7942 were separated by centrifugation, and the absorbance of the supernatant was measured. The binding efficiency was calculated as the percentage of ICG-NPs associated with PCC7942.

Cellular ROS detection

The production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in 4T1 cells was quantified using the fluorescent probe 2’,7’-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA).Following the seeding of cells in 6-well plates and allowing them to reach approximately 80% confluence, the culture was then subjected to co-treatment with ICG-NPs and DCFH-DA under varied experimental conditions, where the order of administration was systematically manipulated.Following this, the culture medium was collected and subsequently removed, after which the adherent cell population was washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).The optical properties of cellular structures were meticulously analyzed through the application of laser scanning confocal microscopy.

Cytotoxicity assay

4T1 cells were plated in 96-well plates and maintained at 37 °C until they reached roughly 80% confluence. The cells were then exposed to various treatment formulations for 12–24 h, corresponding to a final concentration of 5 µg/mL of ICG-NPs or an equivalent amount delivered via PCC7942. Following incubation, the cells were subjected to near-infrared (NIR) laser irradiation (808 nm, 0.3 W/cm²) for 10 min. After irradiation, the medium was replaced with 200 µL of MTT working solution and incubated again at 37 °C for 3 h. The remaining MTT solution was discarded, and 150 µL of dimethyl sulfoxide was added to solubilize the formazan product. The optical density was subsequently recorded at 490 nm using a microplate spectrophotometer.

Bacterial viabillty assay

Bacteria were cultured in appropriate liquid medium to the logarithmic growth phase, harvested by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 5 min, room temperature), washed once with saline, and adjusted to ~ 106 CFU/mL (OD600 ≈ 0.3, diluted 1:100). For viability staining, 100 µL of bacterial suspension was seeded per well in a 96-well plate, followed by the addition of 1 µL of a 100 × Live/Dead staining working solution. After incubation at 37 °C in the dark for 15 min, relative fluorescence was measured using a microplate reader (DMAO: Ex/Em = 503/530 nm; PI: Ex/Em = 535/617 nm). DMAO is a green fluorescent dye, and PI is a red fluorescent dye. Live bacteria exhibit green fluorescence, whereas dead bacteria display both green and red fluorescence.

Cellular uptake

To ensure adequate adherence, 4T1 cells (1 × 10⁵ cells per glass-bottom dish) were incubated for 16–24 h at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO₂. Cells were then incubated with 5 µg/mL ICG-NPs for predetermined durations (2, 4, and 8 h), followed by triple washing with PBS. Fixation was performed using 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, after which nuclei were stained with DAPI (1 µg/mL, 10 min). Fluorescent images were acquired on a confocal microscope using excitation/emission at 405/633 nm for DAPI and ICG, respectively.

Antitumor efficiency of @ ICG-NPs in a refractory tumor model

A tumor-bearing model was established by subcutaneous inoculation of 4T1 cells on the right side of female Balb/c mice (8 weeks old). When the initial volume of the tumor reached approximately 250 mm³, the animals were completely random method divided into 6 coqueues (n = 5/group, with a total of 30 mice) minimize the sample size under the premise of statistical validity, using a completely random method and received different regimens: PBS, ICG-NPs, ICG-NPs + Laser, PCC7942 or PCC7942@ICG-NPs + Laser, intra-tumor injection was performed every other day, and near-infrared laser irradiation (808 nm, 0.3 W/cm2, 10 min) was performed simultaneously. Cage positions were randomly assigned. During injection, a rotational sequence was adopted to avoid the time accumulation effect caused by a fixed operation sequence. Tumor growth was tracked through volume calculation every day and the body weight and survival status of the mice. Neither the operators nor the result evaluators were aware of the grouping information to prevent subjective bias from affecting the treatment or measurement results. No experimental units and results (except those that violate animal ethics principles) are excluded until the ethical endpoint of 1500 mm³ is approached. To euthanize the experimental mice humanely, perform cervical dislocation under anesthesia once the study is completed.

Tumor ROS staining

Fresh tumor tissues were immediately embedded in OCT compound and cryosectioned (8–10 μm). Sections were incubated with the ROS probe DCFH-DA (10 µM) at 37 °C for 30 min in the dark, rinsed with PBS, and subsequently fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. After counterstaining with DAPI, the samples were mounted and observed under a fluorescence microscope.

Hematoxylin & Eosin (H&E) staining

After collection, tumor and organ specimens were preserved in a 4% paraformaldehyde solution (pH 7.4, PBS) at 4 °C for 12–24 h. The fixed tissues were gradually dehydrated using a series of ethanol baths, cleared with xylene, and infiltrated with paraffin. Thin slices of 4–5 μm were cut from the solidified paraffin blocks and transferred to glass slides.

Serum bochemical assays

At the study endpoint, blood was withdrawn from the orbital sinus of the mice, followed by centrifugation at 3000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C to separate serum. The serum was divided into aliquots and stored at − 80 °C until biochemical testing. Commercial assay kits were employed to determine ALT, AST, BUN, and CRE levels in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol.

Flow cytometry analysis

Spleen and tumor samples were isolated from female Balb/c mice (8 weeks old) carrying 4T1 mammary tumors. To obtain single-cell suspensions, tissues were gently minced and subjected to enzymatic digestion with collagenase type IV. After lysis of residual red blood cells, cells were incubated with fluorescence-tagged antibodies recognizing immune surface markers, including CD3, CD4, CD8, CD80, and CD86. Flow cytometric measurements were conducted on a BD system, and subsequent analyses were performed using FlowJo software.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS software. GraphPad Prism 8.0 and Excel were utilized for quantitative analysis and graph plotting. Results are expressed as mean ± SD. Group differences were analyzed by a two-tailed Student’s t-test, with p values below 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001 considered statistically significant.

Results and discussion

Synthesis and characterization of PCC7942@ICG-NPs

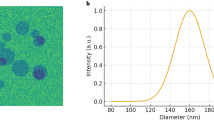

Absolute ethanol was incorporated into the mixed solution of BSA, ICG, and DTT to lower the solubility of BSA, facilitating it with ICG to form ICG-NPs. Following this, ICG-NPs with varying ratios were synthesized to assess the drug loading capacity (Fig. 2A and S1). Synechococcus elongatus PCC7942 (PCC7942) and ICG-NPs interact via electrostatic adsorption. The particle sizes of ICG-NPs, PCC7942, and the PCC7942@ICG-NPs complex were characterized (Fig. 2B). Moreover, the interaction between PCC7942 and ICG-NPs was confirmed through zeta potential measurements and transmission electron microscopy (Fig. 2C and D). Stability assays demonstrated that ICG-NPs exhibited favorable serum stability (Fig. 2E). The binding efficiency of ICG-BSA to PCC7942 was quantified using a microplate reader (Fig. 2F). Based on these data, the ICG loading was calculated to be approximately 290 µg per 10⁹ PCC7942.

Synthesis and characterization of PCC7942@ICG-NPs. A, Drug loading of ICG nanoparticles prepared with different BSA: ICG ratio. B, Size distribution of ICG-NPs, PCC7942 and PCC7942@ICG-NPs. C, Zeta potential results of ICG-NPs, PCC7942 and PCC7942@ICG-NPs. D, TEM images of ICG-NPs, PCC7942 and PCC7942@ICG-NPs. E, Size distribution results of ICG-NPs in PBS containing 10% FBS at different times. F, ICG-NPs efficiency of connecting PCC7942.

In vitro mechanistic evaluation of PCC7942@ICG-NPs

First, free ICG, ICG-NPs, and PCC7942@ICG-NPs did not exhibit significant cytotoxicity under non-laser conditions, confirming that the therapeutic efficacy of this system is strictly light-dependent (Fig. 3A). Notably, light activation significantly increased the cytotoxicity of each component, with the PCC7942@ICG-NPs group showing a significantly lower cell survival rate compared to the ICG-NPs group (Fig. 3B), demonstrating the synergistic enhancement of PCC7942 metabolic activity and ICG-NPs’ photodynamic effect. Monitoring the viability of PCC7942 using bacterial viability staining (Fig. 3C). Cell uptake experiments showed that ICG-NPs exhibited time-dependent endocytosis within 8 h (Fig. 3D). ROS detection further confirmed that laser irradiation significantly increased ROS production levels by ICG-NPs (Fig. 3E and S2). In addition, the relative oxygen production level of PCC7942 under the same light conditions was also measured (Figure S3). The PCC7942@ICG-NPs constructed in this study demonstrates a dual tumor treatment mechanism (Fig. 3F). Under activation by 808 nm laser, the encapsulated cyanobacterial strain PCC7942 improves the tumor hypoxic microenvironment through oxygen production, while the photosensitizer ICG-NPs generates ROS, and the two synergistically enhance the tumor cell-killing effect.

In vitro mechanistic evaluation of PCC7942@ICG-NPs. A, Cytotoxicity of different formulations. B, Cytotoxicity of different formulations under laser irradiation conditions. C, The effect of ICG-NPs on the viability of PCC7942 after laser irradiation at different times. D, ICG-NPs was taken up by cells at different times. E, PCC7942@ICG-NPs With or without laser production of reactive oxygen species. F, PCC7942@ICG-NPs tumor killing mechanism. Data are presented as Mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 via two-tailed student’s test.

In vivo inhibit tumor growth ability of PCC7942@ICG-NPs

The tumor growth inhibition ability of PCC7942@ICG-NPs was evaluated in a 4T1 xenograft tumor-bearing female Balb/c mouse model (Fig. 4A). Intratumoral injection was used to avoid the limitation of deep tumor penetration. Notably, the PCC7942@ICG-NPs group showed the highest inhibition of tumor growth, and the PCC7942@ICG-NPs group had a better survival rate (Fig. 4B–D and S4). In addition, we evaluated the levels of ROS in the tumor and found that the PCC7942@ICG-NPs group had higher ROS levels (Fig. 4E). These results indicated that the ability of PCC7942@ICG-NPs to inhibit tumor growth was related to ROS levels.

In vivo inhibit tumor growth ability of PCC7942@ICG-NPs. A, Schematic diagram of 4T1 tumor-bearing mouse model experiments. B, Growth curve of tumor volume for various formulations (n = 5). C, Graphs of the tumors after the last treatment (n = 5). D, Tumor weights after different treatments (n = 5). E, Fluorescent images of ROS in tumor tissue. Blue represents tumor cells and red represents ROS. Data are presented as Mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 via two-tailed student’s test. G1: PBS, G2: PCC7942, G3: Laser + ICG-NPs, G4: Laser + PCC7942@ICG-NPs.

In vivo safety assessment of PCC7942@ICG-NPs

To systematically evaluate the in vivo safety of PCC7942@ICG-NPs, a comprehensive toxicity assessment was conducted on treated mice through histopathological analysis and blood biochemical examinations. Firstly, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed on major organs, including the heart, liver, spleen, lungs, and kidneys, revealing no significant pathological abnormalities (Fig. 5A). The weight of the mice was within the normal range (Figure S5). These results preliminarily confirm the favorable biosafety profile of PCC7942@ICG-NPs. Additionally, key biomarkers of liver and kidney function, including BUN, CRE, AST, and ALT, remained within normal ranges (Fig. 5B), further demonstrating the excellent biocompatibility of PCC7942@ICG-NPs. However, long-term colonization, immune rejection, and endotoxin risk remain important issues.

In vivo safety assessment of PCC7942@ICG-NPs. A, Histopathological images of major organs stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H༆E) Scale bar is 50 μm. B, Measurement of liver and kidney function indicators, including aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and creatinine (CRE) levels. Data are presented as Mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 via two-tailed student’s test. G1: PBS, G2: PCC7942, G3: Laser + ICG-NPs, G4: Laser + PCC7942@ICG-NPs.

In vivo immune activation ability of PCC7942@ICG-NPs

To elucidate the immune mechanisms contributing to the antitumor efficacy of PCC7942@ICG-NPs, single-cell suspensions were prepared from excised tumors and spleens and subsequently analyzed by flow cytometry. Administration of PCC7942@ICG-NPs markedly promoted CD8+ T-cell infiltration within both tumor tissues and splenic compartments, thereby strengthening the overall antitumor immune response (Fig. 6A and S6-7). In comparison with the control and other treatment groups, mice receiving PCC7942@ICG-NPs exhibited a notably greater decline in regulatory T-cell populations, implying a more efficient alleviation of the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (Fig. 6B and S8-9). Moreover, a significantly elevated proportion of dendritic cells capable of recognizing tumor-associated neoantigens was observed in this group (Fig. 6 C and S10–11), highlighting the potent immunostimulatory potential of the formulation. Serum cytokine profiling further demonstrated a moderate rise in IL-1β, TNF-α, and IFN-γ levels following PCC7942@ICG-NPs combined with laser irradiation, suggesting a well-regulated immune activation without evidence of cytokine storm (Figure S12-14).

PCC7942, as a cyanobacterium, possesses inherent immunogenicity that may trigger immune recognition and activation. To mitigate this risk, BSA was employed as a biocompatible coating material, which improved the stability of the nanoparticles and reduced the direct exposure of bacterial components to the host immune system. In addition, intratumoral administration was selected as a localized delivery strategy to confine the formulation within the tumor microenvironment, thereby minimizing systemic exposure and decreasing the likelihood of widespread immune activation. This approach also promoted in situ immunogenic cell death and tumor antigen release, potentially contributing to systemic antitumor immunity. Nonetheless, intratumoral injection cannot completely eliminate immune recognition, and further investigations are warranted to comprehensively evaluate both local and systemic immune responses, so as to better define the safety profile of PCC7942@ICG-NPs.

.

Conclusion

In summary, this proof-of-concept study developed a bioplatform, PCC7942@ICG-NPs, capable of in situ oxygen generation and ROS production to inhibit tumor growth. Notably, the fabrication of ICG-NPs significantly improved ICG delivery efficiency and facilitated cellular uptake by tumor cells. Upon laser irradiation, PCC7942 generated oxygen at the tumor site while simultaneously enabling activation of the photosensitizer to produce ROS. Furthermore, the oxygen produced by PCC7942 effectively alleviated the hypoxic tumor microenvironment. In vivo experiments demonstrated that PCC7942@ICG-NPs exhibited strong antitumor efficacy and favorable biosafety in a subcutaneous tumor-bearing mouse model. This delivery strategy provides promising insights for the clinical development of photodynamic therapy.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Zhang, Y., Luo, G., Etxeberria, J. & Hao, Y. Global patterns and trends in lung cancer incidence: A Population-Based study. J. Thorac. Oncol. 16, 933–944. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2021.01.1626 (2021).

Nishikawa, H. & Overview New modality for cancer treatment. Oncology 89, 33–35. https://doi.org/10.1159/000431063 (2015).

Luo, H., Ma, W., Chen, Q., Yang, Z. & Dai, Y. Radiotherapy-activated tumor immune microenvironment: realizing radiotherapy-immunity combination therapy strategies. Nano Today. 53, 102042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nantod.2023.102042 (2023).

Gil, M. et al. Photodynamic therapy augments the efficacy of oncolytic vaccinia virus against primary and metastatic tumours in mice. Br. J. Cancer. 105, 1512–1521. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2011.429 (2011).

Lin, D., Shen, Y. & Liang, T. Oncolytic virotherapy: basic principles, recent advances and future directions. Signal. Transduct. Target. Therapy. 8, 156. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-023-01407-6 (2023).

Zhi, D., Yang, T., O’Hagan, J., Zhang, S. & Donnelly, R. F. Photothermal therapy. J. Controlled Release. 325, 52–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.06.032 (2020).

Lan, M. et al. Photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 8, 1900132. https://doi.org/10.1002/adhm.201900132 (2019).

Wan, Y., Fu, L. H., Li, C., Lin, J. & Huang, P. Conquering the hypoxia limitation for photodynamic therapy. Adv. Mater. 33, 2103978. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202103978 (2021).

Wei, F., Rees, T. W., Liao, X., Ji, L. & Chao, H. Oxygen self-sufficient photodynamic therapy. Coord. Chem. Rev. 432, 213714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2020.213714 (2021).

Zhang, C. et al. Strategic design of conquering hypoxia in tumor for advanced photodynamic therapy. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 12, 2300530. https://doi.org/10.1002/adhm.202300530 (2023).

Li, S., Yang, F., Wang, Y., Du, T. & Hou, X. Emerging nanotherapeutics for facilitating photodynamic therapy. Chem. Eng. J. 451, 138621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2022.138621 (2023).

Song, L. et al. Biogenic nanobubbles for effective oxygen delivery and enhanced photodynamic therapy of cancer. Acta Biomater. 108, 313–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2020.03.034 (2020).

Fan, X. et al. Oxygen self-supplied enzyme nanogels for tumor targeting with amplified synergistic starvation and photodynamic therapy. Acta Biomater. 142, 274–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2022.01.056 (2022).

Wang, B. et al. Cyanobacteria-based self-oxygenated photodynamic therapy for anaerobic infection treatment and tissue repair. Bioactive Mater. 12, 314–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2021.10.032 (2022).

Liu, J. et al. Engineered cyanobacteria-based self-supplying photosensitizer nano-biosystem for photodynamic therapy. Chem. Eng. J. 495, 153656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2024.153656 (2024).

An, F. et al. Rationally assembled albumin/indocyanine green nanocomplex for enhanced tumor imaging to guide photothermal therapy. J. Nanobiotechnol. 18 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-020-00603-8 (2020).

Sheng, Y. et al. Oxygen generating nanoparticles for improved photodynamic therapy of hypoxic tumours. J. Controlled Release. 264, 333–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.09.004 (2017).

Sun, M. et al. Boarding oncolytic viruses onto Tumor-Homing Bacterium-Vessels for augmented cancer immunotherapy. Nano Lett. 22, 5055–5064. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.2c00699 (2022).

Guo, X. et al. Synchronous delivery of oxygen and photosensitizer for alleviation of hypoxia tumor microenvironment and dramatically enhanced photodynamic therapy. Drug Deliv. 25, 585–599. https://doi.org/10.1080/10717544.2018.1435751 (2018).

Gao, M. et al. Erythrocyte-Membrane-Enveloped perfluorocarbon as nanoscale artificial red blood cells to relieve tumor hypoxia and enhance cancer radiotherapy. Adv. Mater. 29, 1701429. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201701429 (2017).

Qin, Y. et al. An Oxygen-Enriched photodynamic nanospray for postsurgical tumor regression. ACS Biomaterials Sci. Eng. 6, 6415–6423. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsbiomaterials.0c01099 (2020).

Sun, Q. et al. Self-generation of oxygen and simultaneously enhancing photodynamic therapy and MRI effect: an intelligent nanoplatform to conquer tumor hypoxia for enhanced phototherapy. Chem. Eng. J. 390, 124624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2020.124624 (2020).

Acknowledgements

Declared none.

Funding

This work was financially supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82372111).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Methodology: J. Bai., C. Tang., M. Sun.Performed all the experiments: M. Sun., X. Wang., H. Wang.Analyzed all data: M. Sun., X. Wang. Writing-review and editing: All authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal experiments were conducted in strict compliance with the guidelines and regulations for laboratory animal welfare established by Shenyang Pharmaceutical University (Shenyang, China), and were formally approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the aforementioned institution (Ethical Approval Number: SYPU-IACUC-S2024-1218-107).

Human and animal rights

No human were used in this study. This study adheres to internationally accepted standards for animal research, following the 3Rs principle. The ARRIVE guidelines were employed for reporting experiments involving live animals, promoting ethical research practices.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, M., Wang, X., Wang, H. et al. Regulation of tumor hypoxic microenvironment by cyanobacteria-photosensitizer hybrid bioplatform for enhanced photodynamic therapy. Sci Rep 16, 1205 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30813-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30813-9