Abstract

The task of few-shot named entity recognition (NER) is to identify named entities by using limited annotated samples. Meta-learning, as a specific paradigm in the field of machine learning, has shown good results in acquiring the ability to “learn how to learn” and in quickly learning new tasks. However, some methods in the field of meta-learning identify named entities by calculating the word-level similarity between the query set and support set, without fully considering the label semantic information. To address this issue, we propose a method called UnionPromptNER for few-shot named entity recognition in the bridging domain. This method utilizes a joint prompt strategy to acquire label semantics, and then introduces a framework for computing the semantic representation of joint prompts. Through experiments on three different types of datasets, our proposed method achieved the best results in 19 out of 20 different settings compared with a series of previously optimal methods based on the micro F1 metric.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As an essential component of the transportation infrastructure, bridges play a pivotal role in fostering economic development and enhancing the quality of human life. Numerous bridges have been constructed globally. For instance, at the end of 2022, China had 1,032,200 road bridges with a total length of 85.7649 million linear meters. Among them, there are 8,816 super-sized bridges with a total length of 16.2144 million linear meters, and 15.96 thousand large bridges with a total length of 44.3193 million linear meters.During the construction of road bridges, the industry has accumulated a large amount of textual data, including construction plans, regulatory references, and various types of contracts.These texts contain a wealth of entity and relationship information, which must be explored. Research on key information extraction methods based on named entity recognition in bridge texts can provide core data support for generating specialized plans, intelligent decision-making during the operation of road bridges, and knowledge sharing in the field. This is also an important trend in the digitalization and intelligent development of the civil engineering industry. Figure 1 illustrates the corresponding results when the entities of the NER module in the bridge domain are correctly recognized and when they fail to be correctly recognized.

Named entity recognition (NER), a fundamental task in information extraction, is dedicated to extracting entity information from unstructured text and categorizing it into relevant classes. It has received wide attention and significant development in research fields such as machine learning, deep neural networks, and natural language processing. However, it is important to note that text related to bridges exhibits distinct domain-specific characteristics in terms of specialized terminology, writing style, and structural organization. General domain named entity recognition methods, which typically focus on identifying person names, organization names, and place names, may not yield optimal performance when applied to the bridge domain. The differences between general domain data and bridge domain data in three aspects of professional terminology are shown in Table 1. Additionally, during the process of named entity recognition, the availability of annotated data specifically tailored to the bridge domain is limited, and manual annotation is both time-consuming and expensive. Hence, it is imperative to investigate a named entity recognition solution that is well-suited for the limited sample scenarios encountered in the bridge domain.

In summary, our contributions are as follows:

-

(1)

We introduce a bridge text small-sample named entity recognition approach, UnionPromptNER, which based on joint prompt learning, leveraging the information extraction capabilities of pre-trained models.

-

(2)

We utilize a a joint prompt strategy to acquire label semantics. Furthermore, we introduce a framework for computing the semantic representation of joint prompts.

-

(3)

Experimental results on multiple few-shot NER datasets demonstrate that UnionPromptNER achieves the best results in 19 out of 20 different settings compared with a series of previously optimal methods based on the micro F1 metric.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides an introduction to the current research status of pre-trained models and small-sample named entity recognition in both domestic and international contexts. Section 3 introduces the problem formulation of a few-shot named entity recognition(NER). The proposed method is described in Sect. 4. The next two sections present the experimental setup and results. Finally, conclusions are drawn including limitations and future directions of this study.

Related work and background

Pre-training and fine-tuning

Pre-training refers to the process of training a general language model using large-scale datasets, which are then used as an initializer or feature extractor for downstream tasks. In recent years, several large-scale models trained on massive amounts of data have been proposed, such as BERT1, GPT2, RoBERTa3, and T54, which have played significant roles in advancing the field of natural language processing. Prieto et al.5 conducted a study in which ChatGPT was used to generate a construction schedule for a simple construction project. Hassan et al.6 used a BERT-based model to identify risky and hazardous construction situations. Moon et al.7 used a BERT model to automatically detect contractual risk clauses in construction specifications.

The main advantages of pre-training are a reduction in the need for labeled data, improved model generalization, faster training speed, and a reduced risk of overfitting. Fine-tuning refers to using a pre-trained model as the initial parameter and then conducting a small amount of training on a new task to achieve better performance. Fine-tuning language models for large-scale instruction tasks can significantly improve the performance and generalization ability of models in various settings. It is a common and effective approach to enhance the effectiveness and usability of pre-trained language models8. Lester et al.9 proposed a method for fine-tuning frozen language models by using soft prompts. This prompt tuning method became more competitive as the scale of the model increased. It almost matches the performance of full-model fine-tuning on large models, and has the advantages of robustness and efficiency. Sun et al.10 compared full-parameter and LoRA tuning strategies on a Chinese instruction dataset and found that the choice of the base model, the number of learnable parameters, size of the training dataset, and cost are all key factors that affect the performance of instruction-following models.

Pre-training and fine-tuning have become common paradigms for natural language understanding tasks such as named entity recognition, question answering, and text summarization.

Prompt-based learning

Although pre-training and fine-tuning paradigms have made significant breakthroughs in various natural language processing domains, they have some limitations. Pre-trained models have a large number of parameters and limited flexibility in their model structures. Although fine-tuning can reduce the differences between task distributions, its effectiveness may be limited if the differences are substantial11. Additionally, fine-tuning requires maintaining copies of the model parameters for each downstream task during the inference process, which can be inconvenient.

To address these limitations, many researchers have started exploring the use of large-scale pre-trained language models and have developed a new paradigm in natural language processing called “prompting.” Prompting involves leveraging prompts or cues along with a small amount of labeled data to unlock the potential of large models12,13. This approach aims to overcome the parameter inflexibility and the limited effectiveness of fine-tuning when dealing with substantial differences in task distributions. Using prompts, researchers can guide the behavior of the model and achieve better performance on specific tasks.

In general, prompting allows pre-trained language models to incorporate additional information when performing downstream tasks9,14. According to Petroni et al.15, a language model serves as the knowledge base. The LAMA dataset provides manually created completion templates that enable the exploration of knowledge within pre-trained language models. These templates are query sentences designed manually, allowing the extraction of knowledge from the pre-trained language model and achieving similar results compared to using the model directly. However, manually designing templates as discrete prompts can be time-consuming, costly, and requires extensive expertise from designers16. Shin et al. introduced gradient-based search methods to automatically create prompts for various tasks, thereby reducing the effort required to construct prompt text17. Additionally, some researchers have designed continuous prompts by adding specific prefixes corresponding to small tasks, replacing the need for manual prompt template design and learning through backpropagation18. Numerous studies have demonstrated the significant impact of prompt template quality on the model performance.

In summary, prompting-based learning is indeed a worthwhile direction of research, as it not only unlocks the potential of pre-trained language models but also allows for the exploration of their capabilities.

Few-shot NER

The goal of few-shot named entity recognition (NER) tasks is to classify the identified entities using only a small amount of annotated data. In recent years, several methods have been proposed to address different few-shot learning tasks14,19,20,21,22,23,24 in the NLP community. Sun et al.25 proposed an example-based approach for few-shot NER. This approach is inspired by question-answering to identify entity spans in new and unseen domains. Cui et al.26 proposed a template-based method for NER, treating NER as a language model ranking problem in a sequence-to-sequence framework, where original sentences and statement templates filled by candidate named entity spans are regarded as the source and target sequences, respectively. Wang et al.27 proposed a self-training method for semi-supervised training using a large amount of unlabeled data. A large-scale human-annotated dataset, Few-NERD, was proposed to introduce more fifine-grained entity types in few-shot NER28. Chen et al.29 proposed a self-describing mechanism that described all entity types as a unified concept set. Mapping between types and concepts can be modeled and learned to address the issue of knowledge mismatch. Current Few-shot NER studies have mostly focused on prompt-based formulations to exploit the Pre-trained Language Model (PLM) knowledge more effectively. To address the issue of knowledge mismatch, Kim et al. designed different label mapping methods to achieve the accurate matching of entities30. Beryozkin et al. merged labels of different patterns into the same classification system for knowledge sharing31. Guo et al.32 proposed a Boundary-Aware LLMs for Few-Shot Named Entity Recognition(BANER) to address the over/under-detected false spans in the span detection stage and unaligned entity prototypes.Tang et al.33 introduced data stratification as a preliminary step to consider all entity types fairly and proposed FsPONER which is to incorporate term frequency alongside sentence embedding, enhancing domain-specific NER performance.

We have conducted an extensive and systematic literature review. We searched through major academic databases such as IEEE Xplore, ScienceDirect, SpringerLink, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. The search keywords included combinations of “bridge”, “civil engineering”, “few-shot learning”, “named entity recognition”, “NER”, “limited data”, and related terms. We also reviewed the references of relevant papers to ensure we did not miss any potential studies.

After this thorough investigation, we can confirm that, to the best of our knowledge, there are no existing studies that have specifically focused on few-shot NER in the bridge domain. Previous research on NER in civil engineering or bridge-related fields has primarily relied on large annotated datasets, and few-shot learning approaches have not been applied to this specific domain.

In Contrast to the above related works, we propose a better architectural framework to utilize cue words to mine the semantic information of entities.

Methodology

In this section, we formally present the UnionPromptNER scheme. The Architecture of UnionPromptNER is illustrated in Figure 2.

Problem formulation

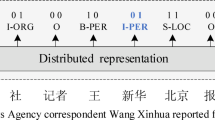

In this section, we focus on the few-shot NER task. Unlike NER tasks with abundant labeled datasets, few-shot NER tasks require fine-tuning with only a small amount of labeled data. This assumption aligns better with real-world scenarios, because acquiring a large amount of high-quality labeled data often incurs significant costs. Specifically, when training the new dataset D with label space Y, we assumed that each type had only K training examples in the training set. In other words, each type contained K data instances with their corresponding true labels. Therefore, the total number of labeled examples is \(K_{tot}=K*|Y|\) . Subsequently, the trained model was tested using an unseen test set \((X_{test}, Y_{test}) \sim D_{test}\). In the NER task, a training sample refers to a continuous entity span \(e=\{x_{1},...,x_{m}\}\) with a positive class label attached. A typical 2-way 2-shot episode is shown in Figure 3.

Prompt schemas

Inspired by existing frameworks such as Prompt Learning26,34 and Metric Learning, our UnionPromptNER incorporates prompt words to provide label semantics and additional semantic information for the metric-learning model. We propose a simple and effective union prompt word template that allows us to provide different prompt words to the model, which is consistent with metric learning approaches that use token-level similarity as a metric. Starting from this template, we introduced two types of prompt words used in UnionPromptNER: fixed-template prompt words and label-semantic prompt words.

Prompt A: Fixed-Template Prompts Typically, the input to an NER system is a natural language sentence. Given a natural language sentence \(X=[x_{1},x_{2},...,x_{n}]\) composed of multiple subwords and a set of label categories \(L=[none,l_{1},l_{2},...,l_{m-1}]\), where \(m=|L|\) and none represents the O-type, we define a fixed prompt word template to restructure the input sentence as follows:

The template function \(\varvec{V}{prompt}(L)\) is used to fill in the template with entity type set, and \(X_{p}\) is the result obtained by converting X through the template function. For example, if the entity type set is none, person name, location name, organization name, technical term, and the input sentence is “The Wuhan Yangtze River Bridge is located in Hubei Province.” By constructing the fixed prompt word template, the resulting prompt words would be “Find some entities, such as none, person name, location name, organization name, technical term:”, which is then concatenated with the input sentence to obtain the final transformed result: “Find some entities, such as none, person name, location name, organization name, technical term: The Wuhan Yangtze River Bridge is located in Hubei Province.” This transformation, using a fixed prompt word template, provides additional semantic information to the model and guides the model to extract entities based on the prompted words.

Prompt B: Label-Semantic Prompts Label semantic prompts are used to add entity labels to the entity words in the input sentence, allowing the model to learn label semantic information. Unlike fixed-prompt word templates, label semantic prompts provide local information to each entity in the model. Specifically, let \(V_{B}(x,y)\) be a label semantic-prompt function. For a given input sentence \(X=[x_{1},x_{2},...,x_{n}]\) and entity label sequence \(Y=[y_{1},y_{2},...,y_{n}]\) , for a certain entity , we first retrieve its corresponding label x from the entity label sequence Y, and then replace entity x in the input sentence with the template \('[x|L]'\) which combines the entity with the label, resulting in the constructed result \(x^{'}=V_{B}(x,y)\).

It is worth mentioning that there are other ways to construct prompts, but in practical applications, we found that these two methods performed exceptionally well.

Model and training

The UnionPromptNER architecture uses a transformer backbone to encode different prompt word results and combines these two types of prompt word results.

During the training phase, we used a small number of samples from the training set \(D_{test}\), where each sample was obtained from a few-shot sequence (\(\delta _{train}, \varrho _{train}\)). We extracted the label set from the support set \(\delta _{train}\) and translated each label into a natural language tag by using a lookup table. This results in a set of tags denoted by \(\Theta\). For an input sentence \(X=[x_{1},x_{2},...,x_{n}]\) and its corresponding label sequence \(Y=[y_{1},y_{2},...,y_{n}]\), we obtain the results \(r_{A}=V_{A}(x,\Theta )\) and \(r_{B}=V_{B}(x,\Theta )\) using fixed template prompt words and label semantic prompt words, respectively.

Next, we fed the prompt word results into a pre-trained language model (PLM) and computed the representations in the intermediate layer as follows:

Next, we combine the two intermediate results using parameter \(\rho\) as follows:

Where \(\rho \in (0,1)\) is a hyperparameter.

Specififically, we employ projection network \(f_{\mu }\) and \(f_{\Sigma }\) for producing Gaussian distribution parameters:

Where \(\mu _{i} \in \Re ^{l}\), \(\Sigma _{i} \in \Re ^{l \times l}\) represents the mean and diagonal covariance of the Gaussian distribution space, respectively. ELU for exponential linear units, and \(\varepsilon \approx e^{-14}\) for numerical stability.

In the case of few-shot learning, for word elements \(x_{m}\) from the support set and word elements \(x_{n}\) from the query set, the Gaussian distributions of the two word elements are as follows:

The distance between two word elements and their corresponding Gaussian distributions can be calculated using the following formula:

Where \(D_{KL}\) means the Kullback-Leibler divergence.

Let \(\delta _{train}^{'}\), \(\varrho _{train}^{'}\) be collections of all tokens from sentences in \(\delta _{train}\), \(\varrho _{train}\). For each \(q \in \varrho _{train}^{'}\), the associated loss function is computed as:

Where \(\chi _q\) is defined by \(\chi _q = \{p \in \delta _{train}^{'}|p,q\) have the same labels}.

To calculate the total loss function for the same batch, which is the sum of the loss functions for all samples, the following process is typically followed:

Inference

In the inference phase, for each word element x in the query set, the Euclidean distance was calculated based on its representation in the feature space. The word element with the shortest Euclidean distance was selected from all the word elements in the support set, and the corresponding label was returned as the label for word element x. This provides an entity label for the word element x.

Experiments

Experiment datasets

To demonstrate the few-shot learning ability of our method, we conducted experiments on two well-designed N-way K-shot few-shot NER datasets and a bridge-domain construction schema text dataset. CROSSNER CrossNER consists of four NER datasets from different domains: CoNLL0335(News), OntoNotes36(Mixed), WNUT-201737(Social), and GUM38(Wiki). FEW-NERD Ding et al.28 propose a human-annotated low-shot named entity recognition dataset called Few-NERD, which is a large-scale dataset specially designed for few-shot NER with 8 coarsegrained and 66 fifine-grained entity types from Wikipedia.We utilize the IO tagging scheme, where the “O” tag is used for non-entity labeling, and entity tags are assigned corresponding entity type labels. We also converted the annotated abbreviations into plain text, for example, by converting [LOC] to [location]. Bridge Text Dataset Bridge Text Dataset were sourced from more than 100 Chinese specifications and construction plan documents in the field of bridges. Following the format of the CoNLL dataset, we prepared two types of low-shot datasets: 1-shot and 5-shot.

Baselines

For different datasets, we chose different baselines for comparison. For Few-NERD, we compared our approach with recently proposed methods such as DecomposedMetaNER39 and ESD40. Additionally, the baselines include a contrastive learning method CONTaiNER41, a prototypical network, ProtoBERT42,43,44, the nearest neighbor-based network NNShot, and its Viterbi decoding variant StructShot45. In addition to DecomposedMetaNER and ProtoBERT, our baselines also include SimBERT, which is a model that predicts labels according to the cosine similarity of word embedding in non-fine-tuned BERT. A classifification head based method, TransferBERT[1], is based on a pre-trained BERT, a few-shot sequence labeling model Matching Network46, and a few-shot CRF model for slot tagging of task-oriented dialogue L-TapNET+CDT44. For bridge-text datasets, our baselines include DecomposedMeta-NER, ESD, ProtoShot, and StructShot.

Evalution protocols

We followed the N-way K-shot downsampling setting proposed by Ding et al.28. This sampling strategy ensures that the sampling set contains N types of entities, and each type of entity appears \(K \sim 2K\) times. We report the micro-F1 scores with standard deviations for the different baselines.

The calculation formula for the micro-F1 is as follows.

Where the calculation formula for \(precision_{mi}\) and \(recall_{mi}\) are as follows.

In formulas (10) and (11), \(TP_{i}\) refers to True Positive for class i , which means that the positive instances in class i are correctly classified as positive. \(FP_{i}\) refers to a False Positive for class i, which means that the negative instances in class i are incorrectly classified as positive instances. \(FN_{i}\) refers to False Negative for class i, which means that the positive instances in class i are incorrectly classified as negative.

Implemention details

We implemented our method using PyTorch version 1.13.1. We used AdamW47 for optimization and set the AdamW optimizer with a 10% linear warmup scheduler; the weight decay ratio was le-2. The value of the hyperparameter is chosen from 0.15, 0.35, 0.55, 0.75, 0.95 and is set to 0.75 by default (which is good enough for almost all cases). The learning rates of the encoder is 2e-4, and the learning rate of the decoder is 2e-3. For all datasets, we train UnionPromtNER for 50-100 epochs. We set the batch size to 1 to narrow the gap between training and fine-tuning, which means that we used one episode per step to update our model. We trained our model on the training set and used the validation set to select the model with the highest F1 scores.

Results and analysis

Main results

Tables 2, 4, and 5 report the performance of UnionPromptNER on the three different datasets. It can be observed that: 1) in the 20 sets of experiments, our method achieved the best performance in 19 sets. To compare with other SOTA methods, we collected the configurations of the other methods and calculated their average and maximum improvement values on the three different datasets. The results indicate that UnionPromptNER significantly outperforms the previous SOTA methods in terms of the micro-averaged F1 score, with an average improvement of 2.84% and a maximum improvement of 11.48%. These comparisons suggest that the proposed method is effective for few-shot NER. 2) in the two types of datasets in Few-NERD, our method shows a more significant performance improvement on Few-NERD Intra compared to Few-NERD Inter. From the results in Table 1, it can be seen that when facing challenging tasks, UnionPromptNER exhibits superior transfer learning capabilities compared with previous methods.

Our architecture of using multiple prompts also mitigates overfitting. We conduct two experiments on Few-NERD to prove this empirically. Figure 4 shows the training curves for CONTaiNER (Das et al., 2022) and our model. From the curves, it can be observed that the performance trends of both models on the training set are similar. However, the performance of CONTaiNER on the development set stops improving much earlier, while our model performs better in the later training epochs. Compared to CONTaiNER, our model shows significant improvement in the later stages. This indicates that in the few-shot setting UnionPromptNER is less affected by overfitting.

To compare whether there are significant differences in the metric data between the experimental group (UnionPromptNER) and the control groups (DecomposedMetaNER, ESD, CONTaiNER, StructShot, ProtoBERT, and NNShot), we conducted a paired t-test on the Intra data in Table 2, and the corresponding result data are presented in Table 3.

Among them, “U” in Table 3 refers to the UnionPromptNER proposed in this paper, while “D”, “E”, “C”, “S”, “P”, and “N” represent the DecomposedMetaNER, ESD, CONTaiNER, StructShot, ProtoBERT, and NNShot models respectively. It can be seen from the result data that compared with the aforementioned methods, the p-values of the UnionPromptNER method proposed in this paper are all far less than 0.05. That is, from the perspective of the result data, there are significant differences between the experimental group and the control groups, which indicates that the performance of UnionPromptNER is significantly better than that of the methods in the control groups.

Ablation study

In this section, we demonstrate the contributions of the different parts of UnionPromptNER. The ablation study results for the Few-NERD (including Intra and Inter), OntoNotes, and Bridge Text datasets are shown in Table 6.

Fixed-Template Prompts & Label-Semantic Prompts According to Table 6, based on the comparison between the prompt-based method and the non-prompt-based method, the former consistently outperforms the latter in terms of performance. These improvements align with the motivations discussed in previous sections. With the help of these two prompt methods, the model can better utilize the information provided and learn the representations for each token in the input statement.

The Effectiveness of Masked Weighted Average According to the results from Table 6, our UnionPromptNER demonstrates significantly better performance across all testing datasets compared to all baseline models, which indicates that both prompting methods contribute to the final performance of the model. By adjusting the value of the average weight \(\rho\), the weights of the two representations for different data distributions can be balanced. Through multiple experiments, we found that the model performed optimally in most cases, when \(\rho =0.75\). Therefore, 0.75 can be considered as the default hyperparameter in our framework. In addition, when other values of \(\rho\), UnionPromptNER still demonstrated performance above most of the baseline models, indicating that our proposed framework is robust.

Qualitative Error Analysis We conducted a qualitative error analysis, taking the experimental results of the six baseline models in Table 2 and our proposed UnionPromptNER model on the Few-NERD dataset as examples. Due to the lack of relevant examples, models such as ProtoBERT, NNShot, and ESD struggled to understand the task requirements and were prone to semantic comprehension biases. When handling the task, the DecomposedMetaNER, CONTaiNER, and StructShot models failed to fully extract or utilize the key information in the input text, missing important attribute information of entities, which resulted in mediocre performance. In contrast, the UnionPromptNER proposed in this paper, by integrating the advantages of multiple prompt strategies, can consolidate the guidance of different prompt methods on key information, thereby reducing the occurrence of information omission errors and interference errors caused by redundant information.

Case Study We selected a small number of examples from the WNUT 1-shot dataset and Bridge Text dataset 1-shot to validate the prediction capabilities of the UnionPromptNER and CONTaiNER models. The results are presented in Tables 8 and 9. UnionPromptNER provides better predictions than CONTaiNER in most cases.

We also applied UnionNERPrompt to the dataset of the water transportation and water conservancy industry for testing, and the test results are shown in Table 10. It can be seen from Table 10 that compared with the CONTaiNER model, UnionNERPrompt also performs well on the dataset of the water transportation and water conservancy industry, with higher accuracy.

Similarly, we have tried other prompt construction methods: direct restore formula prompts (denoted as C), restore form with type explanation prompts (denoted as D), and nested entity hierarchical restoration prompts (denoted as E). The comparison results between these three methods and the fixed-template prompts as well as the label-semantic prompts are shown in Table 7. It can be seen from Table 7 that these three methods have the problems of insufficient accuracy and coverage.

Limitations

Because of our proposed model’s reliance on prompts from large language models, the model is unable to retain span information, meaning that it cannot represent the span of words or phrases in the output of large language models. This requires the extraction of predicted entity types and spans from the output of the large language model through manually designed parsing strategies. However, when the sentence to be predicted contains many repeated words or phrases, the effectiveness of this solution is prone to local optima. This is a data contamination problem that current mainstream large language models temporarily cannot avoid when predicting specific natural language processing tasks, as the training data used by these models are not publicly disclosed.

Another limitation of this study is the interpretability of the model results. Despite the surprising new capabilities exhibited by large language models with increasing model size and training data, there is currently a limited understanding of the source and interpretability of these new capabilities. It remains unclear why these large language models perform well in downstream natural language processing tasks, even without explicit training. Another limitation of this work is that it does not provide guidance on how to obtain the optimal \(\rho\) value that needs to be preset.

Conclusion

In this paper, we introduce UnionPromptNER, a method for bridge domain few-shot named entity recognition via a union prompting strategy. Our approach uses a union prompt strategy to instruct Pre-trained language models to extract entities with specific classes. We tested UnionPromptNER under 20 settings and found that it substantially outperformed the previous SOTA results by an of 2.84% and a maximum of 11.48% in the relative gains of micro F1. Ablation studies were conducted to demonstrate the positive impact of multiple prompt schemas on the generalizability of our model. This study provides a novel, simple, and effective baseline for few-shot learning in NER.

This paper has some possible limitations and future work should address the following problems: 1)To enhance the proposed model, it is possible to incorporate a priori knowledge by utilizing emerging technologies such as sentence embedding and knowledge graph embedding. This is particularly advantageous as external knowledge bases for specific domains often include more comprehensive vocabulary definitions. 2)Although the proposed model can perform a few-shot NER bridge domain, joint entity and relation extraction should be further studied. In addition, because bridge documents contain many tables, efficient tabular information extraction is another important and challenging task that should be considered in the future.

In addition, based on NER-related research, intelligent knowledge base questions and answering solutions for bridge domain information extraction should be explored.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author Shuangshuang Xu on reasonable request via e-mail jhyxss@163.com.

Code availability

The code used for this study are published in https://github.com/SSX0629/bridge-pro-ml.

References

Devlin, J., Chang, M. W., Lee, K. & Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. 4171-4186(2019).

Radford, A., Narasimhan, K., Salimans, T. & Sutskever, I. Improving Language Understanding by Generative Pre-Training. (2019).

Liu, Y. H. et al. RoBERTa: A Robustly Optimized BERT Pretraining Approach. arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.11692 (2019).

Raffel, C. et al. Exploring the Limits of Transfer Learning with a Unified Text-to-Text Transformer. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 140, 1–67 (2020).

Prieto, S. A., Mengiste, E. T. & Borja, G. S. Investigating the Use of ChatGPT for the Scheduling of Construction Projects. Buildings. 13(4), 857 (2023).

Mohamed, H., Hebatallah, A., Marengo, E. & Nutt, W. A BERT-Based Model for Question Answering on Construction Incident Reports. Natural Language Processing and Information Systems. 215-223(2022).

Seonghyeon, M., Chi, S. & Im, S. B. Automated detection of contractual risk clauses from construction specifications using bidirectional encoder representations from transformers (BERT). Automation in Construction. Vol. 142(2022).

Chung, H. W. et al. Scaling instruction-finetuned language models. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 25(70), 1–53 (2024).

Lester, B., Rfou, R. A. & Constant, N. The Power of Scale for Parameter-Efficient Prompt Tuning. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. 3045-3059(2021).

Sun, X. H., Ji, Y. J., Ma, B. C. & Li, X. G. A Comparative Study between Full-Parameter and LoRA-based Fine-Tuning on Chinese Instruction Data for Instruction Following Large Language Model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.08109 (2023).

Liu, P. F. et al. Pre-train, Prompt, and Predict: A Systematic Survey of Prompting Methods in Natural Language Processing. ACM Comput. Surveys. 55(9), 1–35 (2023).

Wang, R. Z. et al. K-Adapter: Infusing Knowledge into Pre-Trained Models with Adapters. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021. 1405-1418(2021).

Moiseev, F., Dong, Z., Alfonseca, E. & Jaggi, M. SKILL: Structured Knowledge Infusion for Large Language Models. NAACL 2022 - 2022 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Proceedings of the Conference. 1581-1588(2022).

Gao, T. Y., Adam, F. & Chen, D. Q. Making Pre-trained Language Models Better Few-shot Learners. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing. 3816-3830(2021).

Petroni, F. et al. Language models as knowledge bases?. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing. 2463-2473(2019).

Shin, R. et al. Constrained Language Models Yield Few-Shot Semantic Parsers. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. 7699-7715(2021).

Shin, T. et al. AutoPrompt: Eliciting Knowledge from Language Models with Automatically Generated Prompts. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP). 4222-4235(2020).

Li, X. L. & Liang, P. Prefix-Tuning: Optimizing Continuous Prompts for Generation. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing. 4582-4597(2021).

Geng, R. Y. et al. Dynamic Memory Induction Networks for Few-Shot Text Classification. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. 1087-1094(2020).

Sheng, J. W. et al. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing(EMNLP). 1681-1691(2020).

Brown, B. B. et al. Language Models are Few-Shot Learners. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems. 1877-1901(2020).

Schick, T. & Schütze, H. It’s Not Just Size That Matters: Small Language Models Are Also Few-Shot Learners. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. 2339-2352(2021).

Wang, S. H. et al. GPT-NER: Named Entity Recognition via Large Language Models. Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: NAACL 2025. 4257-4275(2025).

Wang, S. B. et al. Data Whisperer: Efficient Data Selection for Task-Specific LLM Fine-Tuning via Few-Shot In-Context Learning. In Proceedings of the 63rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. 23287-23305(2025).

Ziyadi, M. et al. Example-Based Named Entity Recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:2008.10570 (2020).

Cui, L. Y. et al. Template-Based Named Entity Recognition Using BART. Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021. 1835-1845(2021).

Wang, Y. Q. et al. Meta Self-training for Few-shot Neural Sequence Labeling. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining. 1737-1747(2021).

Ding, N. et al. Few-NERD: A Few-Shot Named Entity Recognition Dataset. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing. 3198-3213(2021).

Chen, J. W. et al. Few-shot Named Entity Recognition with Self-describing Networks. In Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. 5711-5722(2022).

Kim, H., Yoo, J., Yoon, S. & Kang, J. Automatic Creation of Named Entity Recognition Datasets by Querying Phrase Representations. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. 7148-7163(2023).

Cohn, I. et al. Audio De-identification: A New Entity Recognition Task. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. 197-204(2019).

Guo, Q. J. et al. BANER: Boundary-Aware LLMs for Few-Shot Named Entity Recognition. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Computational Linguistics. 10375-10389(2025).

Tang, Yong. J., Hasan, R. & Runkler, T. FsPONER: Few-shot Prompt Optimization for Named Entity Recognition in Domain-specific Scenarios. In Proceedings of the 27th European Conference on Artificial Intelligence. 3757-3764(2024).

Paolini, G. et al. Structured Prediction as Translation between Augmented Natural Languages. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on International Conference on Learning Representations. ICLR,(2021).

Sang, T. K. & Meulder, F. D. Introduction to the CoNLL-2003 Shared Task: Language-Independent Named Entity Recognition. In Proceedings of the Seventh Conference on Natural Language Learning at HLT-NAACL 2003. 142-147(2003).

Pradhan, S. et al. Towards Robust Linguistic Analysis using OntoNotes. In Proceedings of the Seventeenth Conference on Computational Natural Language Learning. 143-152(2013).

Derczynski, L., Nichols, E., Erp, M. V. & Limsopatham, N. Results of the WNUT2017 Shared Task on Novel and Emerging Entity Recognition. In Proceedings of the 3rd Workshop on Noisy User-generated Text. 140-147(2017).

Zeldes, A. The GUM corpus: creating multilayer resources in the classroom. Language Resources and Evaluation. 51(3), 581–612 (2017).

Ma, T. T. et al. Decomposed Meta-Learning for Few-Shot Named Entity Recognition. Find. Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2022, 1584–1596 (2022).

Wang, P. Y. et al. An Enhanced Span-based Decomposition Method for Few-Shot Sequence Labeling. In Proceedings of the 2022 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. 5012-5024(2022).

Das, S. S. S., Katiyar, A., Passonneau, R. & Zhang, R. CONTaiNER: Few-Shot Named Entity Recognition via Contrastive Learning. In Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. 6338-6353(2022).

Snell, J., Kevin, S. & Zemel, R. Prototypical Networks for Few-shot Learning. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems. 4080-4090(2017).

Fritzler, A., Logacheva, V. & Kretov, M. Few-shot classification in named entity recognition task. In Proceedings of the 34th ACM/SIGAPP Symposium on Applied Computing. 993-1000(2019)

Hou, Y. T. et al. Few-shot Slot Tagging with Collapsed Dependency Transfer and Label-enhanced Task-adaptive Projection Network. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. 1381-1393(2020).

Yang, Y. & Katiyar, A. Simple and Effective Few-Shot Named Entity Recognition with Structured Nearest Neighbor Learning. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP). 6365-6375(2020).

Vinyals, O. et al. Matching Networks for One Shot Learning. In Proceedings of the 30th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems. 3637-3645(2016).

Loshchilov, I. & Hutter, F. Decoupled Weight Decay Regularization. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on International Conference on Learning Representations. ICLR,(2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wei Tian: Project administration. Shuangshuang Xu: Methodology and Writing. Yongwei Wang: Data Curation. Hao Li: Investigation. Hao Zhu: Validation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tian, W., Xu, S., Wang, Y. et al. UnionPromptNER serves as a union prompting method to bridge few-shot named entity recognition. Sci Rep 16, 1224 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30822-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30822-8