Abstract

A controlled peatland rewetting experiment was conducted on two adjacent drained peatland sites in southeastern Norway. Eddy covariance monitoring of CO2 and CH4 fluxes at both sites began in 2019. In 2021, the Treatment Site was rewetted while the Control Site remained drained. Using nine environmental variables and the processed flux data as training data, Bayesian Additive Regression Tree (BART) models were used to generate annual flux balances for CO2 and CH4. The 4-year mean annual flux at the Control Site was 17.3 ± 10 g CO2-C m− 2 yr− 1 and 4.6 ± 0.1 g CH4-C m− 2 yr− 1. At the Treatment Site, the 2-year mean annual flux before the rewetting was 12.2 ± 3.8 g CO2-C m− 2 yr− 1 and 1.8 ± 0.04 g CH4-C m− 2 yr− 1. In the first year after rewetting the annual flux was 53.3 ± 13 g CO2-C m− 2 yr− 1 and 3.8 ± 0.3 g CH4-C m− 2 yr− 1, and in the second year after rewetting the annual flux was 41.2 ± 18 g CO2-C m− 2 yr− 1 and 3.4 ± 0.4 g CH4-C m− 2 yr− 1. BART counterfactual modeling was able to estimate the effect of the rewetting on CO2 and CH4 fluxes. Two years after the rewetting, the BART counterfactual modeling estimated that the cumulative fluxes had increased by 80.3 ± 49 g CO2-C m− 2 and 3.4 ± 0.47 g CH4-C m− 2 because of the rewetting. Carbon flux monitoring of both sites is ongoing as the Control Site remains drained and the soil and vegetation at the Treatment Site continues to adjust to the altered hydrological regime after rewetting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Starting approximately 12 000 years ago, present day northern peatlands began to form and accumulate large quantities of carbon, significantly impacting the global C budget1. The average carbon flux in northern peatlands across the Holocene is estimated to be -18.6 g C m− 2 yr− 1, with the fastest rates of carbon accumulation occurring in the early Holocene (-25 g C m− 2 yr− 1)1. Today, estimates of the carbon stock of northern peatlands are as high as 1055 Gt C2. However, draining of both northern and tropical peatlands for agriculture and forestry combined with the extraction of peat as a fuel source has likely turned peatlands from a global carbon sink to a carbon source3. Draining of peatlands increases carbon emissions through increasing the rate of oxidative microbial decomposition, increasing dissolved carbon loss, and making peatlands more vulnerable to fire4. At present, drained peatlands emit approximately 2 Gt CO2 annually, which accounts for 5% of all anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions5.

Norway has the third largest extent of peatlands in Europe, after Finland and Sweden. However, given Norway’s topographical complexity and ecosystem diversity, estimating peatland area in the country is challenging. The Norwegian area frame survey of land cover estimated that Norwegian peatlands cover 41 655 km26, while Moen et al.7 estimated the area of peatland in Norway to be 44 700 km2. Estimates of the drained peatland area in Norway also vary. Kløve et al.8 estimated that 5050–5700 km2 of peatlands have been drained in Norway: 4200 km2 for forestry and between 850 and 1500 km2 for agricultural purposes. Synthesizing the work of Johansen9, Johansen10, and Moen and Øien11, Moen et al.7 estimated that the area of drained peatland in Norway to be 7000 km2. These estimates primarily define peatlands as lands where peat reaches at least 30 cm deep. Conversely, the 2023 National Inventory Report (NIR) for Norway, which reports the land sector carbon balance of Norway to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), and which defines forested organic soils as those reaching 40 cm deep, estimated a drained organic soil area of 2317 km212. However, if drained forested mineral soils are included in this estimate, the total area of drained soil becomes 7790 km2, an estimate much closer to Moen et al.7.

Previous research suggests that drained peatlands could contribute significantly to Norway’s annual carbon emissions. Using tier-1 IPCC emission coefficients, the 2023 NIR for Norway estimated that drained organic soils in Norway emit 4.65 million tons of CO2e yr− 1, or 9% of Norway’s annual carbon emissions, which were 49.2 million tons CO2e yr− 1 in 202112. Joosten et al.13 estimated that 3618 km2 of peatlands are drained in Norway and that these lands emit 5.55 million tons CO2e yr− 1. Regardless, both estimates by the NIR12 and Joosten et al.13 are made with tier-1 IPCC coefficients, which do not incorporate country-specific data and thus are inherently uncertain. Grønlund et al.14 estimated carbon emissions from peat soils used for agricultural purposes in Norway via long-term monitoring of subsidence rates, mineral content, and CO2 flux measurements. The authors estimated the area of agricultural peat soil to be 630 km2 and the total C loss to be approximately 1.8 to 2 million tons CO2e yr− 1 (600 g C m− 2 yr− 1). Higher resolution estimates of carbon emissions from all drained Norwegian peatlands, not only agricultural peatlands, are currently not available in part because only very few studies have measured carbon fluxes in these landscapes in Norway8.

Given the potential for drained peatlands to be a significant contributor to Norway’s carbon emissions, the Norwegian Environment Agency has prioritized peatland rewetting work to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and improve ecosystem health. As of 2020, 80 sites have been restored, and more sites are to be restored in the coming decades15.

While results of peatland rewetting vary, previous research indicates rewetting most often leads to a reduction in vertical carbon fluxes of CO216,17. However, CH4 fluxes commonly increase after rewetting, though emission levels are highly dependent on vegetation composition and level of ecological succession18. Methane emissions after rewetting can also lag because of long term suppression of methane producing microorganisms19. As such, it is important that long term studies (i.e., longer than three years) are conducted to better understand the carbon dynamics of restored peatlands and their true potential for climate mitigation. However, long-term monitoring programs for restored peatlands are rare, which is a limitation of current research16.

Waterborne lateral carbon fluxes in peatlands can be equal to or greater than vertical carbon fluxes and are important to consider when establishing a carbon balance of peatland ecosystems20,21. After peatland rewetting, dissolved organic carbon (DOC) fluxes can be particularly high if a high volume of soil is left exposed22. However, lateral fluxes in peatland ecosystems have been studied less than vertical carbon fluxes23. Lateral carbon transport includes DOC, dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC), particulate organic carbon (POC), dissolved CO2 gas and dissolved CH4 gas. DOC is commonly the largest source of carbon transport from peatlands. Once transported offsite, on average between 80 and 100% of DOC is eventually respired and emitted to the atmosphere as CO222.

This research is motivated by current estimates which indicate carbon emissions from drained peatlands in Norway are a major component of the country’s land sector carbon budget13. However, the current lack of field-based research monitoring such emissions in Norway limits the accuracy of these estimates. The timely aim of this project is to investigate to what extent peatland rewetting in Norway would have its intended effect of carbon emission reduction as envisaged by Husby15.

To achieve these aims a controlled peatland rewetting experiment is being conducted, in which two adjacent peatland sites–the Treatment Site and Control Site–were selected and monitored for vertical CO2 and CH4 fluxes using eddy covariance. After two years of monitoring, the Treatment Site was rewetted while the Control Site remained drained. This paper focuses on the short-term response in vertical CO2 and CH4 fluxes at the Control Site and Treatment Site two years before and two years after the rewetting. Additionally, vegetation mapping, water table depth monitoring, soil analyses, and coarse estimates of DOC fluxes were conducted at both sites. Monitoring at both sites is ongoing to develop a longer time series of flux data that will be used to study the longer-term effects of rewetting.

Methods

Site description, drainage conditions, experimental design, and timeline

To date, most peatland rewetting projects by the Norwegian Environment Agency have been conducted in southeastern Norway. Consequently, drained peatland sites in this region were prioritized. The selected sites needed to be relatively close to share a single off-grid power supply and be easily accessible for routine maintenance of the measurement equipment and power systems. Two peatland sites in the Regnåsen and Hisåsen Nature Reserve (Trysil Municipality, Innlandet County) met all selection criteria (Fig. 1).

Both the Control Site and Treatment Site were presumably drained for forestry. Aerial photography indicates that both sites were drained between 1956 and 197524, though the exact year is uncertain due to a lack of historical records. The Control Site was drained by six parallel drainage ditches, spaced by 20–30 m (measured from the center of one drainage ditch to the next), and that range from approximately 1 to 1.5 m deep. The Treatment Site was drained with seven parallel drainage ditches, spaced by 15 to 25 m and that range from approximately 1 to 1.2 m deep.

An eddy covariance tower was installed at the center of both the Treatment Site (61.105185°N, 12.254734°E) and the Control Site (61.111581°N, 12.250595°E) in June 2019. The flux tower at the Treatment Site is located at 680 m asl. and the flux tower at the Control Site is located at 640 m asl. The drainage ditches at the Treatment Site cover 4.7 ha and 3.3 ha at the Control Site. The Treatment Site underwent rewetting from September to November 2021, while the Control Site remained drained. For consistency in tracking annual fluxes, 1 October 2021 is used as the rewetting date. Annual fluxes are reported for the two years before the rewetting (1 October 2019–30 September 2021), which is referred to as the Pre-Treatment Period. Similarly, annual fluxes are reported for two years after the rewetting (1 October 2021–30 September 2023), which is referred to as the Treatment Period. 2019/20 is used to represent the first year of the study from 1 October 2019–30 September 2020. The same notation is used to refer to the second (2020/21), third (2021/22), and fourth year (2022/23) of the study. However, there is one exception to this convention. Dissolved organic carbon (DOC) lateral fluxes were estimated on a standard calendar basis in 2021 and 2022.

Regional geography, geology, climate, and ecosystem description

The Regnåsen and Hisåsen Nature Reserve is 15.7 km2 and ranges from 400 to 720 m asl. in elevation. The reserve was created in 2017 to preserve biological diversity, including the lichens, coniferous forests, and peatland types in the area25. The reserve is dominated by evergreen conifers with scattered peatlands appearing in flat or depressed landscapes. The geology is dominated by Precambrian rocks of the Baltic shield, predominantly slowly weathering quartzite and feldspar-dominated granites26. The Köppen-Grieger climate classification is subarctic (Dfc - cold, no dry season, cool summers)27. For the period between 1991 and 2020 the mean annual temperature was 3.4 °C and the mean annual precipitation was 946 mm28.

The Regnåsen and Hisåsen Nature Reserve is in southeastern Norway. Catchments of the Control Site and Treatment Site are shaded in blue and orange, respectively. The outlet of each site’s catchment is marked with a blue dot. A black dot marks the placement of the two flux towers. The 90% footprint of the two flux towers is delineated by the red dotted polygon. The map was created in QGIS 3.30 (QGIS.org, 2023).

Rewetting description

From September to November 2021, the Treatment Site was rewetted though ditch blocking by the Norwegian Environment Agency (Fig. 2). Three hundred and sixteen peat dams at 40 cm elevation intervals were built using peat excavated from between the ditches. In total, 3 823 m of ditches were blocked that had previously drained the site. To minimize soil and vegetation disturbance the first step in the soil excavation process was to remove the grasses and shrubs, including their rootzones, and set them aside. The ditches were then filled. Once this was completed, the vegetation was replaced to its original location. Some of the trees growing on the site, primarily those on the edges of the ditches, were cut down and also used to fill the ditches. To our knowledge, the rewetting of the Treatment Site did not affect the Control Site.

Peat coring

Between 6 and 8 August 2024, peat samples were collected at 5 cm intervals in three replicate profiles within a 10 × 10 m area at both the Treatment Site and Control Site. Coring was conducted manually in approximately 0.5 m increments. Cores were immediately photographed and subsequently cut in 5 cm intervals and transferred to plastic bags. Samples were kept cold at approximately 5 °C until they were processed in the laboratory.

Based on the total weight of the volume-specific samples before and after drying (48 h), the water contents and bulk densities were calculated. Soil pH was measured directly in soil water extractions, using a soil to water ratio of 1:5. Deionized water was added and the mix shaken for 1 h at room temperature, centrifuged and finally filtered through a 5 μm membrane filter before the pH measurement (pHenomenal pH 1100 LTM, VWR, Darmstadt, Germany). After drying the subsamples were finely ground and analyzed for carbon (C) and nitrogen (N) concentration using a Eurovector elemental analyzer (Redavalle, Italy) coupled to Isoprime (Isoprime Ltd., Cheadle Hulme, UK) isotope ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS). Depth-integrated soil C pools were calculated based on soil bulk density and content of soil C reported in four depths: 0–30, 30–50, 50–100 and 0–100 cm.

Vegetation mapping

Vegetation at the site was mapped in-situ using field-computers, and polygon delineation assisted by aerial photos in QGIS. The vegetation was mapped in accordance with the Nature in Norway v.2.3 classification system29, which includes standardized mapping guidelines. Mapping was conducted in August 2022 over 0.25 km2 area surrounding each flux tower. The mapping scale was set to 1:20 000 with a minimum polygon size of 1 000 m2.

Meteorological measurements and water table depth monitoring

Radiation was measured with a CNR4 radiometer (Kipp & Zonen, Netherlands). Air temperature and relative humidity were measured with a HMP155 (Vaisala, Finland). Soil temperature was measured using a Stevens HydraProbe sensor (Stevens Water Monitoring Systems Inc, USA). Five WatsonC loggers equipped with RKL-01 water table depth sensors (Hunan Rika Electronic Tech Co. Ltd) were installed in five water table depth monitoring wells at both the Treatment Site and the Control Site. For the location of the water table depth monitoring wells see Supplementary Information (Sect. 1, Table S1).

Gaps in the time series of the meteorological variables measured onsite (shortwave and longwave radiation, air temperature and pressure, vapor pressure deficit, wind speed) were filled using the bias-corrected ERA5-Land dataset30, downloaded from the Climate Data Store (CDS) of the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S). The ERA5-Land variables were first bias corrected by using a simple linear regression with the corresponding onsite variable. A random forest regression was then trained for each meteorological variable, using the bias-corrected ERA5-Land meteorological variables, time since rain, and growing degree days as predictors. Gaps in the onsite meteorological and soil temperature time series were then filled using the random forest regression31. Annual ET estimates were obtained by gap filling eddy covariance ET data with a random forest model using the gap-filled meteorological and surface variables as predictors.

Eddy covariance measurements

To monitor vertical carbon fluxes of CO2 and CH4, eddy covariance flux towers were installed at each site on 19 June 2019. The flux towers are equipped with a HS50 sonic anemometer (Gill Instruments Ltd, UK), a Li-7200 infrared gas analyzer for CO2 and H2O mixing ratios, and a Li-7700 open-path gas analyzer for CH4 densities (LI-COR Biosciences, USA). These instruments were installed at a height of 2.8 m above ground level and sampled at 20 Hz. These raw data are processed in 30-minute intervals following the conventional eddy covariance method32 implemented in EddyPro version 6.2.0 (LI-COR Biosciences, USA). A block average Reynolds decomposition was used to extract turbulent fluctuations, and corrections were applied for anemometer tilt, a constant time lag compensation, and a high and low-pass filter correction33,34, as well as the Webb, Pearman, and Leuning (WPL) correction for CH4 fluxes35.

For quality control, the statistical tests proposed by Vickers and Mahrt36 were used on the raw data and the flagging system proposed by Foken and Wichura37 were used to filter out flux estimates affected by instrument errors (e.g., rain or frost on the anemometer) or unfavorable micrometeorological conditions (e.g., lack of stationarity or turbulent mixing at low wind speeds). Following Vickers and Mahrt36, the number of spikes and drop-outs, as well as the absolute limits, amplitude resolution, skewness and kurtosis, and discontinuities in the raw data time series were used for EC flux filtering. Data exceeding the threshold proposed in Vickers and Mahrt36 were discarded. In a manner consistent with Pirk et al.38,39 data was also discarded when the mean horizontal wind speed was below 1.5 m s− 1. All fluxes with quality flags 1 and 2 in the scheme by Foken and Wichura37 were also discarded.

Lastly, all data reported here uses positive numbers to represent carbon fluxes from the surface to atmosphere and negative numbers are used to represent carbon fluxes from the atmosphere to surface.

Statistical flux modeling

All valid eddy covariance measurements were used as training data for a set of Bayesian Additive Regression Tree (BART) models. These BART models were introduced in the statistics literature by Chipman et al.40 and more recently reviewed by Hill et al.41. BARTs can be thought of as Bayesian (i.e., probabilistic) extensions of popular ensemble-based decision tree machine learning methods. The latter include random forests and extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost), both of which have shown promise for gap-filling eddy covariance data38,42. In this study, BARTs were chosen over a random forest or XGBoost approach because of their superior computational performance43, and because BARTs provide uncertainty quantification. Specifically, BARTs are sum-of-tree models more closely related to boosting than to bagging-based methods like random forests40. What sets BARTs apart from the aforementioned conventional ensemble-based decision tree methods is their foundation in Bayesian inference44,45 rather than traditional optimization techniques. Instead of producing a single forest based on an ensemble of decision trees, a BART model generates a posterior meta-ensemble of forests. This uncertainty-aware framework enhances robustness in decision-making and causal inference41.

In this study, BARTs were constructed in the probabilistic programming language PyMC46 as presented by Quiroga et al.47. Specifically, the BART models were trained to predict fluxes based on nine environmental variables. The environment variables used included shortwave and longwave incoming radiation, air temperature and pressure, vapor pressure deficit, wind speed, growing degree days, time since rain, and soil temperatures at five depths (5–70 cm). For further information about the BART model setup, see the Supplementary Information (Sect. 2).

For consistency between modeling of actual fluxes and counterfactual fluxes, the BART flux estimates, which matched the eddy covariance flux measurements closely, were also used even when valid measurements from the eddy covariance system existed. Summary statistics in the form of the mean, 5th percentile, and 95th percentile of the 200-member posterior ensemble of the BART predictions are used as the best estimate of actual fluxes.

Counterfactual flux modeling

In the original experimental design, the continuously drained Control Site was intended to serve as the counterfactual to the rewetted Treatment Site. However, differences between the CO2 and CH4 fluxes between the two sites before the rewetting of the Treatment Site, meant that it was not possible to use the Control Site as a counterfactual representation of fluxes at the Treatment Site after rewetting. Instead, counterfactual BART modeling was used to develop best estimates of the effect of the rewetting on CO2 and CH4 fluxes.

A BART model was built for both the Treatment Site and the Control Site from the eddy covariance data from 1 October 2019 until the rewetting in October 2021; these are referred to as the Pre-Treatment Models. Separate BART models were built for both sites from eddy covariance data from 1 October 2021–1 October 2023; these are referred to as the Treatment Models.

To determine if the Pre-Treatment Models could accurately simulate fluxes during the Treatment Period at the Control Site, and to obtain a counterfactual estimate of what the fluxes would have been at the Treatment Site had the rewetting not occurred, we used the Pre-Treatment Models to simulate Treatment Period fluxes at both sites. To run this simulation, the Pre-Treatment Models were forced with nine environmental variables from the Treatment Period to make flux predictions. At the Control Site, we hypothesized that the Pre-Treatment Model simulation of the Treatment Period would match our best estimate of the actual Treatment Period fluxes derived from the Treatment Model. At the Treatment Site, we hypothesized that the Pre-Treatment Model simulation of Treatment Period would diverge from the actual fluxes as estimated by the Treatment Model, and that this divergence would be representative of the effect of the rewetting.

Lateral carbon flux estimation methods

To estimate dissolved organic carbon (DOC) concentrations in the streams draining the Control Site and the Treatment Site, water samples were collected in 0.5 L bottles on seven different occasions at the Control Outlet and the Treatment Outlet (Fig. 1). Four sampling trips were made to take DOC samples before the rewetting in 2021 (22 June, 26 July, 28 July, and 30 July), and three trips were made to take samples after the rewetting in 2022 (9 September, 13 September, and 10 October). For further details about the water sampling, see Supplementary Information (Sect. 3).

A coarse estimate of DOC fluxes was made using Eq. 1.

Where DOCf is the lateral DOC flux (g C m− 2 yr− 1), where Q is the lateral discharge rate (m3 yr− 1), where DOCc is DOC concentration (g C m− 3), and where A is catchment area (m2). Discharge was estimated using a simple water balance model. For further details about the method of discharge estimation, see Supplementary Information (Sect. 4).

Results

Vegetation mapping

The peatlands at Regnåsen and Hisåsen are formed by species-poor fens (V1-E-1) and swamp forests with a scattered tree-layer dominated by Pinus sylvestris (V2-E-1) and Betula pubescens (Table 1). These areas receive an influx of groundwater, but the slow weathering and nutrient poor bedrock provides low levels of basic plant nutrients. The peatlands of both ecosystem types are dominated by the vascular plants: Trichophorum cespitosum, Eriophorum vaginatum, Carex puciflora, Andromeda polifolia and Vaccinium species. The bottom-layer is dominated by Sphagnum species such as S. compactum, S. tenellum, S. lindbergii and S. papillosum48. On firm dry ground Pinus sylvestris form heather forests with Pleurozium schreberi (T4-E-4), whereas Hylocomium splendens, Polytrichum sp. and Sphagnum mosses form the bottom-layer on more moist ground (T4-E-1). The very small lakes (L) are typically dystrophic (high levels of dissolved humus and low oxygen levels), with species such as Scheuchzeria palustris along the water’s edge.

The mapping area at the Control Site consisted of predominantly species-poor fen systems (V1-E-1: 42%), blueberry forest (T4-E-1: 36%) and swamp forest (V2-E-1: 14) (Fig. 3). The Treatment Site consisted of predominantly species-poor fens (V1-E-1: 40%), blueberry forest (T4-E-1: 35%), and swamp forest (V2-E-1: 23%).

Nature in Norway (NiN) vegetation map of the Treatment Site (south) and Control Site (north) at a 1:20 000 scale. Vegetation mapping was conducted in August 2022, approximately 10 months after the rewetting of the Treatment Site. The map was created in QGIS 3.3049.

The effect of the rewetting on the water table depth

Figure 4 compares the median water table depth in five wells at the Control Site and the Treatment Site in the year before the rewetting in 2020/21, and two years after the rewetting, in 2022/23. The median water table depth across all wells at the Control Site was 30 cm in the year before the rewetting and 29 cm two years after the rewetting. The median water table depth across all wells at the Treatment Site was 30 cm in the year before the rewetting and 21 cm two years after the rewetting. Therefore, as estimated by the five wells at the Treatment Site, the rewetting raised the median water table level by 9 cm.

Soil characteristics

The peat characteristics, as measured after the rewetting of the Treatment Site, were similar at the two sites in pH and carbon content with both properties increasing slightly with depth (Table 2). However, the total carbon stock to 1 m depth was markedly higher at the Treatment Site than at the Control Site, particularly at depths below the depth influenced by rewetting (0.5–1 m). Overall, the peat can be characterized as an acidic, organic rich peat.

Vertical CO2 fluxes

Instantaneous CO2 fluxes

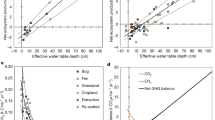

Over the four years of the study at the Control Site the growing season CO2 flux ranged from − 7.5 µmol m− 2s− 1 during the daylight hours to 5.0 µmol m− 2s− 1 at night (Fig. 5a; Table 3). Before the rewetting at Treatment Site the growing season CO2 flux ranged from − 6.3 µmol m− 2s− 1 during the daylight hours to 5.9 µmol m− 2s− 1 at night. After the rewetting at Treatment Site the growing season CO2 flux ranged from − 5.9 µmol m− 2s− 1 during the day to 5.5 µmol m− 2s− 1 at night.

In the two years before the rewetting, the mean growing season CO2 flux during daylight hours was − 2.2 µmol m− 2 s− 1 at the Control Site and − 2.0 µmol m− 2 s− 1 at the Treatment Site (Fig. 5b). In the first year after the rewetting, the mean growing season CO2 flux during the daylight hours was − 1.8 µmol m− 2 s− 1 at the Control Site and − 1.1 µmol m− 2 s− 1 at the Treatment Site. In the second year after the rewetting, the growing season mean CO2 flux during the daylight hours was − 1.89 µmol m− 2 s− 1 at the Control Site and − 1.90 µmol m− 2 s− 1 at the Treatment Site. During the non-growing season, the mean CO2 flux at all hours of the day were similar at both Treatment Site and Control Site across all four years of the study, ranging from from 0.29 to 0.33 µmol m− 2s− 1.

Cumulative CO2 fluxes

The cumulative CO2 flux after one year at the Control Site was 8.2 ± 9 g C m− 2, 11.8 ± 17 g C m− 2 after two years, 18.8 ± 11 g C m− 2 after three years, and 69.0 ± 24 g C m− 2 after four years (Fig. 5c). The Pre-Treatment Model predicting Treatment Period fluxes estimated that after four years the cumulative flux would be 22.4 ± 49 g C m− 2, lower than but within the uncertainty range of the best estimate of the actual cumulative flux (69.0 ± 24 g C m− 2) at this time.

The cumulative CO2 flux after one year at the Treatment Site was 21.5 ± 9 g C m− 2, 24.3 ± 13 g C m− 2 after two years, 77.6 ± 9 g C m− 2 after three years, and 118.8 ± 15 g C m− 2 after four years (Fig. 5d). The Pre-Treatment Model predicting Treatment Period fluxes estimated that had the rewetting not occurred the cumulative flux would have been 38.7 ± 47 g C m− 2 after four years. Therefore, the counterfactual modeling estimated that the rewetting increased the CO2 flux by 80.3 ± 49 g C m− 2 in the two years after the restoration (Table 5).

Annual CO2 fluxes

The mean annual CO2 flux at the Control Site across the four years of the study was 17.3 ± 10 g C m− 2 yr− 1 and ranged from 3.6 ± 20 g C m− 2 yr− 1 (second year) to 50.2 ± 26 g C m− 2 yr− 1 (fourth year) (Table 4). At the Treatment Site the mean annual CO2 flux was 12.2 ± 3.8 g C m− 2 yr− 1 before the rewetting and 47.3 ± 5.4 g C m− 2 yr− 1 after the rewetting. The highest annual CO2 flux at the Treatment Site was 53.3 ± 13 g C m− 2 yr− 1 in the year after the rewetting. In the following year, the fourth year of the study, the annual CO2 flux decreased to 41.2 ± 18 g C m− 2 yr− 1.

Vertical CH4 fluxes

Instantaneous CH4 fluxes

Across all four years of the study, CH4 fluxes at the Control Site ranged from − 2.8 nmol m− 2 s− 1 to 50.7 nmol m− 2 s− 1 (Fig. 5e). Before the rewetting the CH4 fluxes at the Treatment Site ranged from − 5.9 nmol m− 2 s− 1 to 35.9 nmol m− 2 s− 1, and after the rewetting CH4 fluxes ranged from − 3.4 nmol m− 2 s− 1 to 35.5 nmol m− 2 s− 1 (Fig. 5f).

Across all years of the study, the mean CH4 flux at the Control Site during the growing season was 28.0 nmol m− 2 s− 1 and during the non-growing season was 7.2 nmol m− 2 s− 1 (Fig. 5e). Before the rewetting at the Treatment Site the mean CH4 flux was 14.6 nmol m− 2 s− 1 during the growing season and 0.5 nmol m− 2 s− 1 during the non-growing season (Fig. 5f). After the rewetting at the Treatment Site the mean CH4 flux was 20.0 nmol m− 2 s− 1 during the growing season and 6.25 nmol m− 2 s− 1 during the non-growing season.

Cumulative CH4 fluxes

The cumulative CH4 flux after one year at the Control Site was 5.2 ± 0.11 g C m− 2, 10.3 ± 0.25 g C m− 2 after two years, 14.9 ± 0.14 g C m− 2 after three years, and 18.5 ± 0.31 g C m− 2 after four years (Fig. 5g). The Pre-Treatment Model predicting Treatment Period fluxes estimated that after four years the cumulative flux would be 20.6 ± 0.43 g C m− 2, slightly higher than the estimate of the actual flux at this time.

The cumulative CH4 flux after one year at the Treatment Site was 1.5 ± 0.06 g C m− 2 yr− 1, 3.5 ± 0.14 g C m− 2 after two years, 7.3 ± 0.25 g C m− 2 after three years, and 10.7 ± 0.37 g C m− 2 after four years (Fig. 5h). The Pre-Treatment Model predicting Treatment Period fluxes estimated that had the rewetting not occurred the cumulative flux would have been 7.0 ± 0.03 g C m− 2, lower than the actual flux at this time. Therefore, the counterfactual modeling estimated that the rewetting increased the CH4 flux by 3.7 ± 0.37 g C m− 2 in the two years after the restoration (Table 5).

Annual CH4 fluxes

The mean annual CH4 flux at the Control Site across the four years of the study was 4.6 ± 0.1 g C m− 2 yr− 1 and ranged from 5.2 ± 0.1 g C m− 2 yr− 1 (first year) to 3.6 ± 0.3 g C m− 2 yr− 1 (fourth year) (Table 4). At the Treatment Site the mean annual CH4 flux was 1.8 ± 0.04 g C m− 2 yr− 1 before the rewetting and 3.6 ± 0.13 g C m− 2 yr− 1 after the rewetting. The highest annual CH4 flux at the Treatment Site was 3.8 ± 0.3 g C m− 2 yr− 1 in the year after the rewetting. In the following year, the CH4 flux was 3.4 ± 0.4 g C m− 2 yr− 1.

CO2 fluxes at the Control Site (a) and Treatment Site (b) in 30 min intervals by hour of the day; cumulative CO2 fluxes at the Control Site (c) and Treatment Site (d); CH4 fluxes at the Control Site (e) and Treatment Site (f) in 30 min intervals by hour of the day; and cumulative CH4 fluxes at the Control Site (g) and Treatment Site (h).In c, d, g, and h the solid blue lines are the Pre-Treatment Models, the orange lines are the Treatment Models, and the dashed blue lines are the Pre-Treatment Model simulations of Treatment Period fluxes (i.e., a predicted flux for the Control Site (c, g) and a counterfactual flux for the Treatment Site (d, h)). In c, d, g, and h the shaded areas indicate the 90th percentile range from the 5th percentile to 95th percentile. The yellow bar represents the rewetting time period at the Treatment Site in September to November of 2021. The grey bar on the Control Site plots indicate the same time period and is included to indicate that the flux data at the Control Site was processed in exactly the same manner as the Treatment Site. The Control Site remains drained and was unaffected by the rewetting of the Treatment Site.

Lateral fluxes

DOC concentrations

In 2021, the mean DOCC across the four sampling dates was 28.8 mg l− 1 at the Control Site and across the three sampling dates in 2022 was 23.3 mg l− 1 at the Treatment Site (Table S2). In 2022, the mean DOCC across the three sampling dates was 34.0 mg l− 1 at the Control Site and 41.7 mg l− 1 at the Treatment Site (Table S2).

Lateral DOC carbon flux estimates

The estimated discharge from the Control Site was 35 900 m3 in 2021 and 26 500 m3 in 2022 (Table S3). The estimated lateral DOCf from the Control Site was 17 g C m− 2 yr− 1 in 2021 and 19 g C m− 2 yr− 1 in 2022.

The estimate discharge from the Treatment Site was 54 800 m3 in 2021 and 40 500 m3 in 2022 (Table S3). The estimated lateral DOCf from the Treatment Site was 14 g C m− 2 yr− 1 in 2021 and 15 g C m− 2 yr− 1 in 2022.

Discussion

Distinguishing between short-term and long-term effects of rewetting

This paper reports four years of flux data from 2019 to 2023, including two years of the flux data from the Treatment Site prior to the rewetting, two years of flux data from the Treatment Site after the rewetting, and four years of flux data from the Control Site during which the site remained in the drained condition. With only two years of flux data after rewetting at the Treatment Site, our results reflect only the short-term effects of rewetting. Monitoring at both sites is ongoing to collect a time series of flux data that will allow for the assessment of the longer-term effects of rewetting.

Vertical and lateral carbon flux dynamics

In reports of the land sector carbon budget to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), Norway uses IPCC Tier 1 coefficients to estimate greenhouse gas emissions from drained peatlands. The Tier 1 CO2 emission coefficient for a drained nutrient poor inland organic soil that is forest, shrubland, and non-forest in a drained condition is 37 g C m− 2 yr− 122. By comparison the mean CO2 flux at the Control Site across the four years of the study was 17.3 ± 10 g C m− 2 yr− 1, a slightly lower-than-expected mean value. However, the variability in the annual flux of CO2 from the Control Site was higher than expected. In the first three years of the study the Control Site was nearly CO2 neutral. However, in the fourth year of the study the CO2 fluxes increased to 50.2 ± 26 g C m− 2 yr− 1. To our knowledge, the rewetting of the Treatment Site did not have an effect on the Control Site, making this increase unexpected. The annual mean water table depth at the Control Site remained unchanged throughout the study and annual rainfall totals in the first three and last year of the study were similar. The reason for the observed increase in CO2 fluxes from the Control Site in the last year of the study is unclear, and a longer time series of flux data is needed to explain this increase.

The Treatment Site in the two years before the rewetting also had a lower-than-expected mean CO2 flux of 12.2 ± 3.8 g C m− 2 yr− 1. In the first year after the rewetting the CO2 flux at the Treatment Site increased to 53.3 ± 13 g C m− 2 yr− 1, which was likely related to the soil and vegetation disturbances caused by the rewetting activities. During the rewetting, trees growing in the ditches were cut down while the low-lying vegetation was mechanically removed from the ditches. Peat was then excavated from the areas between the ditches to fill the ditches, and then the vegetation was replaced. While the flux data was not formally partitioned in this study, the felling of trees and movement and replacement of low-lying vegetation appear to have reduced plant CO2 uptake. In addition, the soil excavations likely lead directly to an increase in the labile carbon pool and a higher rate of organic matter mineralization. In the second year after the rewetting the annual CO2 flux decreased to 41.2 ± 18 g C m− 2 yr− 1. Ongoing monitoring at the site will determine if and by how much CO2 emissions at the Treatment Site continue to decrease in future years.

Short-term increases in CO2 and CH4 fluxes after the completion of rewetting projects, like those observed at the Treatment Site in this study, are well documented50. However, it is the longer-term effects of rewetting on carbon fluxes that are most important when considering the carbon balance of such rewetting projects. A growing number of studies indicate that the majority of restored temperate and boreal peatlands return to CO2 sinks on time scales of approximately twenty years50,51,52. However, in some cases, rewetting has not returned previously drained peatland sites to a CO2 sink within this time period52. Additionally, Wilson et al.52 state that CO2 fluxes from restored peatlands may be more sensitive to inter-annual variability in weather conditions. Thus, previous research suggests CO2 fluxes at the Treatment Site are likely to continue to gradually decrease, but that the annual flux variability may be high, especially in comparison to pristine peatlands.

Overall, the CO2 fluxes from both sites in this study, including the Treatment Site after rewetting, were relatively weak CO2 sources. Ojanen et al.53 estimated CO2 fluxes at 68 drained for forestry peatland sites in Finland by subtracting litter input to soil from CO2 soil efflux and found that nutrient rich sites were on average CO2 sources of 142 g C m− 2 yr− 1 and nutrient poor sites were on average CO2 sinks of -52 g C m− 2 yr− 1. As such, the range of CO2 fluxes of both sites in this study across all years, which ranged from 3.6 ± 20 to 53.3 ± 13 g C m− 2 yr− 1, were higher than CO2 fluxes found on nutrient poor forestry-drained peatlands in Finland, but was well within the range of what has been found in Finland on forestry-drained peatlands overall.

The mean annual CH4 flux at the Control Site was 4.6 ± 0.1 g C m− 2 yr− 1, while the mean annual CH4 flux at the Treatment Site was 1.8 ± 0.04 g C m− 2 yr− 1 before the rewetting. Thus, the CH4 flux at the Control Site was more than double that of the Treatment Site during the Pre-Treatment Period. The water table level of both sites before the rewetting was similar and the vegetation type of the two sites were also similar. This study did not analyze carbon fractions, but it is possible that the Control Site had a higher percentage of labile carbon than the Treatment Site. Before the rewetting there was also a weak uptake of CH4 at the Treatment Site in the non-growing season. Methane oxidation that results in CH4 uptake in drained peatlands has also been observed in several other studies54,55. The strength of this uptake in the non-growing season weakened with the rewetting, but surprisingly was still occurring. Future work at the site would also benefit from soil analyses that measured the nutrient content of the peat at both sites. Incubation experiments could also be performed on peat from the site to study near surface CH4 oxidation, which can be an important determinant of overall CH4 fluxes56.

Annual CH4 fluxes increased after the rewetting at the Treatment Site to a two-year mean of 3.6 ± 0.13 g C m− 2 yr− 1, which was double the mean flux before rewetting. The increase in CH4 emissions will likely decrease through time as observed in Kalhori et al.51. In addition, modeling work indicates that short-term increases in CH4 emissions from rewetted peatlands do not offset the benefits of decreased CO2 emissions when multi-decadal or century long time scales are considered5,57.

Our rough estimates of DOC export, however crude given the low number of samples collected and the greatly simplified methodology used for estimating discharge, suggest that lateral carbon transport from the peatland sites is possibly a significant contributor to the net ecosystem carbon balance of both sites. DOC is commonly significant to the net ecosystem carbon balance in peatland ecosystems, and especially of drained peatlands20,58. The DOC export estimates in this study ranged from 14 to 19 g C m− 2 yr − 1, which are the same order of magnitude as the vertical carbon fluxes observed at both sites. The IPCC Tier 1 estimate of DOC export from drained boreal peatlands is 13 g C m− 2 yr − 1, while the estimate for natural boreal peatlands is 8 g C m− 2 yr − 122. Given these IPCC estimates, it seems likely that the Control Site DOC export will remain similar in future years, while the Treatment Site DOC flux may start to slowly decline as the site recovers from the disturbance caused by the rewetting. Haapalehto et al.59 found that after rewetting of boreal peatlands in Finland, DOC levels take at least 5 years to decrease from pre-rewetting levels, while peatland hydrology takes roughly 10 years to approximate pristine peatland hydrology.

Water table depth and implications for carbon fluxes

The median water table depth of both the Control Site and of the Treatment Site before rewetting was approximately 30 cm, and after the rewetting the median water table depth at the Treatment Site rose to 20 cm. At three forestry-drained peatland sites in central and southeastern Norway, Stachowicz et al.60 measured water table depth both before and after rewetting. The authors found that before rewetting the water table depths were 20, 23, and 30 cm, and thus overall, slightly shallower than the water table depths at the Control Site and Treatment Site in this study. After rewetting of the three sites, which was also achieved by ditch blocking, Stachowicz et al.60 found that the water table depth rose by an average of 6 cm, and 8 cm at the study site most similar two sites in this study. This result is very similar to the change in water table depth after rewetting at the Treatment Site in this study of 10 cm. As such, it appears that the drainage conditions of the two sites in this study, and the effects of the rewetting on water table depth at the Treatment Site, are similar to other sites recently rewetted in southern and central Norway.

To upscale carbon fluxes from drained peatlands, it is increasingly common to use water table depth transfer functions. Koch et al.61 developed such relationships for drained peat soils in Denmark, Evans62 did so for the UK, and Tiemeyer et al.63 for Germany. However, applying these transfer functions to the Control Site in this study gives a mean annual CO2 flux ranging from of 100 to 900 g C m− 2 yr− 1, and thus greatly overestimates the actual mean annual CO2 fluxes at the Control Site in this study of 17.3 ± 10 g C m− 2 yr− 1. This overestimation is likely because these relationships were not developed specifically for forestry-drained peat soils. Conversely, Ojanen and Minkkinen64 developed a water table depth to carbon flux transfer function for forestry-drained boreal peatlands in Finland. This transfer function estimates an annual flux of -17 g C m− 2 yr− 1, and thus much more closely approximates the observed fluxes at the site (underestimates by 34 g C m− 2 yr− 1). Developing similar transfer functions for peatlands drained for forestry in Norway is currently not possible because of a lack of carbon flux data. To our knowledge, this is the first study to report CO2 and CH4 fluxes from a forestry-drained peatland in Norway.

Vegetation dynamics

The vegetation mapping was conducted after the rewetting of the Treatment Site, but the mapping of the Control Site revealed that only 20% of the Control Site flux tower footprint was classified as drained fen vegetation, while 69% of the footprint was fen vegetation associated with nutrient poor pristine fens. Vegetation mapping using the Nature in Norway system is a binary typology in which the peatland is mapped as either a drained fen vegetation type or as a pristine fen vegetation type. The mapping system does not have vegetation types for transitional states between pristine and drained fen vegetation. The presence of Betula (birch) and Pinus (pine), together with the coverage of shrubs, and less dominance of Sphagnum mosses, were used for mapping of drained fen vegetation. The sites in this study appear to have been drained effectively enough to support greater tree cover than they would have under undrained conditions but not drained effectively enough for the afforestation efforts to be successful. Nutrient poor peatlands drained for forestry in Finland have been found to typically be carbon sinks53, however in this study the Control Site and the Treatment Site before rewetting were both weak carbon sources. This phenomenon may be explained by the fact that the sites in this study were very slowly afforesting and thus the tree growth was not fast enough to turn the sites into carbon sinks as has been observed in Finland.

The exact date that the two sites were drained is unknown due to a lack of historical records and can only be constrained to sometime between 1956 and 1975 using ariel photography. Despite it being at least 50 years since the sites had been drained, the canopies of both sites remained open at the start of this project in 2019, with only discontinuous coverage of birch (Betula pubescens) and pine (Pinus sylvestris). Forestry drained peatlands in the Nordic countries typically have a 60–100 stand rotation time64 during which the ditches are commonly cleaned multiple times65. It is not clear when the afforestation efforts at the Treatment Site and Control Site were abandoned. Whether the sites were sowed or planted after ditching, or if the ditches were ever maintained is unknown.

The BART model

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first time that Bayesian Additive Regression Tree (BART) models have been applied to eddy covariance data. The BART models used in this study were adopted because they warrant more testing in geoscientific applications, provide comparatively easily attainable uncertainty estimates, and can be used to estimate causal effects.

Note that, other than the hyperparameters of the Particle Gibbs sampler (number of chains, steps, and burn-in), the BART models employed here only have two hyperparameters: m (the number of regression trees) and the prior scale of the standard deviation. Thus, like other decision tree-based methods, they require minimal input from the user while maintaining a high predictive performance. At the same time, the fact that BARTs are Bayesian models make them less prone to overfit and provide valuable uncertainty quantification41. Although more flexible probabilistic machine learning models such as Bayesian neural networks39 exist for flux estimation, their added flexibility comes at the cost of being considerably more challenging to set up than BARTs.

Of the nine environmental variables that the BART models in this study used to predict CO2 and CH4 fluxes, water table depth was not one of them despite water table depth being one of the most important environmental variables used in the peatland carbon flux modeling66. Water table depth was omitted so that the Pre-Treatment Model could predict the counterfactual Treatment Period fluxes at the Treatment Site. Including actual water table depth, which significantly changed during the Treatment Period, would interfere with the estimation of counterfactual fluxes. In future work, hydrological modeling could estimate the water table depth of the Treatment Site had it not been restored and these estimations could be used in the counterfactual BART modeling, which might improve the Pre-Treatment Models ability to predict Treatment Period fluxes. Because water table depth was omitted as a BART predictor the fluxes that are estimated by the Pre-Treatment Models in the Treatment Period are likely less accurate than they would have been had we modeled the counterfactual water table depth and included it as a predictor. We hypothesize that the Pre-Treatment Model would have more accurately predicted Treatment Period fluxes at the Control Site if water table depth had been included, which would have in turn increased our confidence in the accuracy of the counterfactual estimates at the Treatment Site.

Another limitation of our counterfactual modeling is that some of the other environmental variables used to force BART model simulations of the counterfactual fluxes may have been affected by the restoration, such as soil temperatures at five depths (5–70 cm) and vapor pressure deficit. However, the other environmental variables used to force the BART models including shortwave and longwave incoming radiation, air temperature and pressure, wind speed, and growing degree days, we expect to be minimally affected by the restoration or not affected at all (i.e., time since rain).

Limitations and future work

The primary limitation of most peatland rewetting studies, including this study to date, is that the sites are only monitored for three or fewer years after rewetting, which is not sufficient to determine the steady state effect of the rewetting on the ecosystems carbon balance17,51. Monitoring at the sites is continuing so that a longer time series of CO2 and CH4 fluxes after the rewetting is recorded. An additional limitation of this study is that, while it included a drained peatland site as a control, it did not include a pristine reference peatland site. In future studies, monitoring a third, undisturbed peatland would strengthen the experimental design.

The great variation in vegetation composition, nutrient status, micrometeorology, hydrology, and land use history of peatlands make it difficult to predict carbon emissions of a specific drained peatland and how the specific peatland site will respond to rewetting17. In addition, Norwegian peatland ecosystems vary greatly by climate, proximity to the coast, and elevation13, and many of them are still not present on official maps6. However, predicting carbon emissions has been shown to be possible in other studies. By taking chamber-based CO2, CH4, and N2O efflux measurements at drained peatlands across Finland, Ojanen et al.53 were able to build a model that explained 66% of the variation in the total annual CO2 effluxes at 68 study sites across Finland. Conducting similar multi-site studies across drained Norwegian peatlands would help characterize carbon flux variability and could further assist in refining emissions estimates at the country level.

Overall, the DOC export estimates in this study were limited by a coarse estimation of discharge, sparse DOC measurements, and by solely considering DOC as the lateral carbon transport mechanism. We recommend that further work include the installation of v-notch weirs to track discharge from both the Treatment and Control Sites. In addition, hydrological models could be calibrated to these weir data so that discharge can be simulated in both past and future. A total of seven DOC measurements were made in this study, and these measurements did not span the entire snow free season. DOC measurements throughout the snow free season need to be taken to resolve the possible seasonal patterns in DOC concentration. Lastly, while DOC is often the most significant contributor to lateral carbon fluxes in drained organic soils22, dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) and particulate organic carbon (POC), are also contributors to lateral carbon transport and also warrant being measured at both sites.

Conclusion

Differences in CO2 and especially CH4 fluxes between the Control Site and Treatment Site before the rewetting meant that the Control Site could not serve as the counterfactual representation of the fluxes at the Treatment Site, as was originally intended by the experiment. However, the ability of the BART models to predict counterfactual carbon fluxes appears to be a promising alternative in determining the effect of rewetting on the net ecosystem carbon balance. Even though the Control Site did not serve directly as a counterfactual representation of the Treatment Site, tracking carbon fluxes at the Control Site is beneficial as it is currently the only drained for forestry peatland being actively monitored for carbon fluxes in Norway.

At both the Control Site and the Treatment Site, the mean annual CO2 fluxes were lower than - and CH4 fluxes were higher than - the IPCC Tier 1 emission coefficients for boreal drained nutrient poor organic soils. Export of DOC was similar in magnitude to the vertical CO2 and CH4 flux at both the Treatment Site and Control Site, warranting more accurate DOC estimates in the future.

The CO2 flux from the Treatment Site increased significantly after the rewetting but decreased from the first to the second year after rewetting. Previous peatland rewetting studies suggest that the carbon mitigation potential of peatland rewetting can take approximately 10–20 years to be realized51. However, in some cases, rewetting does not return peatland ecosystems to carbon sinks within this time period67. As such, monitoring at the Control Site and Treatment Site will continue to elucidate the carbon flux trajectory of both sites in the years to come.

Data availability

The BART gap-filled flux data, the nine environmental variables that were used as the BART predictors, and the water table depth data are all available for download at the following DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17552123.

References

Yu, Z., Loisel, J., Brosseau, D. P., Beilman, D. W. & Hunt, S. J. Global peatland dynamics since the last glacial maximum. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, L13402. https://doi.org/10.1029/2010GL043584 (2010).

Nichols, J. E. & Peteet, D. M. Rapid expansion of Northern peatlands and doubled estimates of carbon storage. Nat. Geosci. 12, 917–921. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-019-0454-z (2019).

Frolking, S. et al. Roulet, N. Peatlands in earth’s 21st century climate system. Environ. Rev. 19, 371–396. https://doi.org/10.1139/A11-014 (2011).

Leifeld, J. & Menichetti, L. The underappreciated potential of peatlands in global climate change mitigation strategies. Nat. Commun. 9, 1071. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03406 (2018).

Günther, A. et al. Prompt rewetting of drained peatlands reduces climate warming despite methane emissions. Nat. Commun. 11, 1644. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15499-z (2020).

Bryn, A., Strand, G. H., Angeloff, M. & Rekdal, Y. Land cover in Norway based on an area frame survey of vegetation types. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift - Nor. J. Geography 72. 3, 131–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/00291951.2018.1468356

Moen, A., Lynstad, A. & Øien, D. I. Norway. In Joosten, H., Tanneberger, F. & Moen, A. (eds.) 2017. Mires and Peatlands of Europe: Status, Distribution and Conservation. Stuttgart: Schweizerbart Science. (2017).

Kløve, B., Berglund, K., Berglund, Ö., Weldon, S. & Maljanen, M. Future options for cultivated nordic peat soils: can land management and rewetting control greenhouse gas emissions? Environ. Sci. Policy. 69, 85–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2016.12.017 (2017).

Johansen, A. The extent and use of peatlands in Norway. In: Global Peat Resources (ed. E. Lappalainen), 113–117. (1996).

Johansen, A. Myrarealer Og torvressurser i Norge. Jordforsk Rapp. 1, 1–37 (1997). Mire area and peat resources in Norway.

Moen, A. & Øien, D. I. Faktaark Fra to prosjekter med vurdering av truethet Og vernestatus for våtmark (myr Og kjelde) i Norge. [Information from two projects with evaluation of impact factors and status for protection of wetlands (mires and springs) in Norway]. NTNU Vitensk Museum not notat. 4, 1–62 (2011).

National Inventory Report Norway. Greenhouse Gas Emissions 1990–2021: National Inventory Submission, submitted under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Kyoto Protocol. (2023). https://unfccc.int/documents/627398

Joosten, H. et al. Metoder for å Beregne Endring I Klimagassutslipp Ved Restaurering Av Myr. Naturhistorisk Rapport 10 (NTNU Vitenskapsmuseet, 2015).

Grønlund, A., Hauge, A., Hovde, A. & Rasse, D. P. Carbon loss estaimtes from cultivated peat soils in norway: a comparison of three methods. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 81, 157–167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10705-008-9171-5 (2008).

Husby, V. Plan for the rewetting of wetlands in Norway. Miljø-Direktoratet. M-1903. (2020).

Strack, M. & Zuback, Y. C. A. Annual carbon balance of a peatland 10 year following rewetting. Biogeosciences 10, 2885–2896. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-10-2885-2013 (2013).

Weldon, S., Parmentier, F. J. W., Grønlund, A. & Silbernnoinen, H. Rewetting of bogs: the potential for carbon storage and reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. Norsk Institutt for Bioøkonomi. 2 (113), (2016).

Waddington, J. M. & Day, S. M. Methane emissions from a peatland following rewetting. J. Phys. Res. 112, G03018. https://doi.org/10.1029/2007/JG000400 (2007).

Goodrich, J. P., Campbell, D. I., Roulet, N. T., Clearwater, M. J. & Schipper, L. A. Overriding control of methane flux Temporal variability by water table dynamics in a Southern hemisphere Raised bog. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosciences. 120, 819–831. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014JG002844 (2015).

de Wit, H. A., Ledesma, J. L. J. & Futter, M. N. Aquatic DOC export from subartic Atlantic blanket bog in Norway is controlled by sea salt deposition, temperature, and precipitation. Biogeochemistry 127, 305–321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-016-0182-z (2016).

Billett, M. F. et al. Linking land-atmosphere-stream carbon fluxes in a lowland peatland system. Global Biochem. Cycles. 18, GB1024. https://doi.org/10.1029/2003GB002058 (2004).

Drösler, M., Verchot, L. V., Freibauer, A. & Pan, G. Drained Inland Organic Soils. 2013 Supplement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories: Wetlands. (2013).

Beckebanze, L. et al. Lateral carbon export has low impact on the net ecosystem carbon balance of a polygonal tundra catchment. Biogeosciences 19, 3863–3876. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-19-3863-2022 (2022).

Norge i Bilder Geodata AS. (2016). https://www.norgeibilder.no.

Lovdata Regulations on the protection. of Regnåsen and Hisåsen nature reserve, Trysil municipality, Hedmark. (2022). https://lovdata.no/dokument/LF/forskrift/2017-06-21-885

Ramberg, I. B., Bryhni, I. & Nøttvedt, A. The Making of a Land: Geology of Norway (Geological Society of Norway, 2007).

Peel, M. C., Finlayson, B. L. & McMahon, T. A. Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 11, 1633–1644 (2007).

Hersbach, H., Bell, B., Berrisford, P., Hirahara, S., Horányi, A., Muñoz-Sabater,J., Nicolas, J., Peubey, C., Radu, R., Schepers, D., Simmons, A., Soci, C., Abdalla,S., Abellan, X., Balsamo, G., Bechtold, P., Biavati, G., Bidlot, J., Bonavita, M.,… Thépaut, J. N. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society. 146(730), 1999–2049. https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.3803 (2020).

Halvorsen, R. et al. Towards a systematics of ecodiversity: the EcoSyst framework. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 29 (11), 1887–1906. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.13164 (2020).

Muñoz-Sabater, J. et al. ERA5-Land: A state-of-the-art global reanalysis dataset for land applications. Earth Syst. Sci. Data. 13, 4349–4383 (2021).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: machine learning in python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Gu, L. et al. The fundamental equation of eddy covariance and its application in flux measurements. Agric. For. Meteorol. 152, 135–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2011.09.014 (2012).

Moncrieff, J., Clement, R., Finnigan, J., Meyers, T. & Averaging, Detrending, and filtering of eddy Co-variance time series. In Handbook of Micrometeorology Vol. 29 (eds Lee, X. et al.) (Springer, 2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-2265-4_2.

Moncrieff, J. B. et al. Verhoel, A. A system to measure surface fluxes of momentum, sensible heat, water vapour and carbon dioxide. J. Hydrol. 188–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1694(96)03194-0 (1997).

Webb, E. K., Pearman, G. I. & Leuning, R. Correction of flux measurements for density effects due to heat and water vapour transfer. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.49710644707 (1980).

Vickers, D. & Mahrt, L. Quality control and flux sampling problems for tower and aircraft data. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 14, 512–526 (1997).

Foken, T. & Wichura, B. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology. Tools for Quality Assessment of Surface-Based Flux Measurements. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 78. (1996).

Pirk, N. et al. Snow-Vegetation-atmosphere interactions in alpine tundra. Biogeosciences 20 (11), 2031–2047. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-20-2031-2023 (2023).

Pirk, N. et al. Disaggregating the carbon exchange of degrading permafrost peatlands using bayesian deep learning. Geophys. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2024GL109283 (2024).

Chipman, H. A., George, E. I. & McCulloch, R. E. BART: Bayesian Additive Regression Trees. The Annals of Applied Statistics. 4(1), 266–298 https://doi.org/10.1214/09-AOAS285 (2010).

Hill, J., Linero, A. & Murray, J. Bayesian additive regression trees: A review and look forward. Annual Rev. Stat. Its Application. 7, 251–278. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-statistics-031219-041110 (2020).

Vekura, H. et al. A widely-used eddy covariance gap-filling method creates systematic bias in carbon balance estimates. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-28827-2 (2023).

He, J. & Hahn, P. R. Stochastic tree ensembles for regularized nonlinear regression. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 118, 551–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.2021.1942012 (2021).

Martin, O. A., Ravin, K. & Junpeng, L. Bayesian Modeling and Computation in Python Boca Ratón. ISBN 978-0-367-89436-8 (2021).

Murphy, K. P. Probabilistic Machine Learning: Advanced Topics (MIT Press, 2023). http://probml.github.io/book2

Abril-Pla, O. et al. Zinkov, R. PyMC: a modern, and comprehensive probabilistic programming framework in python. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 9, e1516. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.1516 (2023).

Quiroga, M., Garay, P. G., Alonso, J. M. & Loyola, J. M. Martin, O.A. Bayesian additive regression trees for probabilistic programming, arXiv, (2023). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2206.03619

Kyrkjeeide, M. O., Lunde, L. M. F., Lyngstad, A. & Molværsmyr, S. Restaurering av myr. Overvåking av tiltak i 2021. NINA Rapport 2051. Norsk institutt for naturforskning, Trondheim. (2021).

QGIS Development Team. QGIS Geographic Information System. Open Source Geospatial Foundation. (2025). Available at: https://qgis.org

Nugent, K. A., Strachan, I. B., Strack, M., Roulet, N. T. & Rochefort, L. Multi-year net ecosystem carbon balance of a restored peatland reveals a return to carbon sink. Glob. Change Biol. 24, 5751–5768. https://doi.org/10.111/gcb.14449 (2018).

Kalhori, A. et al. Temporally driven carbon dioxide and methane emission factors for rewetted peatlands. Commun. Earth Environ. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01226-9 (2024).

Wilson, D. et al. Multiyear greenhouse gas balances at a rewetted temperate peatland. Glob Chang. Biol. 22, 4080–4095 (2016).

Ojanen, P., Minkkinen, K., Alm, J. & Pentillä, T. Soil-atmosphere CO2, CH4 and N2O fluxes in boreal forestry-drained peatlands. For. Ecol. Manag. 260, 411–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2010.04.036 (2010).

Lohila, A. et al. Greenhouse gas flux measurements in a forestry-drained peatland indicate a large carbon sink. Biogeosciences 8, 3203–3218 (2011).

Turetsky, M. R. et al. A synthesis of methane emissions from 71 northern, temperate, and subtropical wetlands. Glob Chang. Biol. 20, 2183–2197 (2014).

Askaer, L., Elberling, B., Friborg, T., Jørgensen, C. J. & Hansen, B. U. Plant-mediated CH₄ transport and C gas dynamics quantified in-situ in a phalaris arundinacea-dominant wetland. Plant. Soil. 343, 287–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-011-0718-x (2011).

Zou, J. et al. Rewetting global wetlands effectively reduces major greenhouse gas emissions. Nat. Geosci. 15, 627–632. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-022-00989-0 (2022).

Dinsmore, K. J. et al. Role of the aquatic pathway in the carbon and greenhouse gas budgets of a peatland catchment. Glob. Change Biol. 16, 2750–2762. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.02119.x (2010).

Haapalehto, T., Kotiaho, J. S., Matilainen, R. & Tahvanainen, T. The effects of long-term drainage and subsequent rewetting on water table level and pore water chemistry in boreal peatlands. J. Hydrol. 519, 1493–1505 (2014).

Stachowicz, M., Lynstad, A., Osuch, P. & Grygoruk, M. Hydrological response to rewetting of drained Peatlands- A case study of three Raised bogs in Norway. Land https://doi.org/10.3390/land14010142 (2025).

Koch, J. et al. Water-table-driven greenhouse gas emission estimates guide peatland restoration at National scale. Biogeosciences 20, 2387–2403. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-20-2387-2023 (2023).

Evans, C. D. et al. Overriding water table control on managed peatland greenhouse gas emissions. Nature 593, 548–552. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03523-1 (2021).

Tiemeyer, B. et al. A new methodology for organic soils in National greenhouse gas inventories: data synthesis, derivation and application. Ecol. Indic. 109 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2019.105838 (2020).

Ojanen, P. & Minkkinen, K. The dependence of net soil CO2 emissions on water table depth in boreal peatlands drained for forestry. Int. Mire Conserv. Group. https://doi.org/10.19189/Ma (2019).

Sikström, U. & Hökkä, H. Interactions between soil water conditions and forest stands in boreal forests with implications for ditch network maintenance. Silva Fennica 50(1), 1–29 (2016).

Mozafari, B., Bruen, M., Donohue, S., Renou-Wilson, F. & O’Loughlin, F. Peatland dynamics: A review of process-based models and approaches. Sci. Total Environ. 877. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.162890 (2023).

Schaller, C., Hofer, B. & Klemm, O. Greenhouse gas exchange of a NW German Peatland, 18 years after rewetting. JGR Biogeosciences. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1029/2020JG005960

PyMC Community. Bayesian Additive Regression Trees: Introduction. (2022). https://www.pymc.io/projects/examples/en/latest/case_studies/BART_introduction.html

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the US-Norway Fulbright Foundation for Educational Exchange for its support of this project through a 10-month student research stipend awarded to Michael Bekken. Thanks also to Magni Olsen Kyrkjeeide at NINA for assistance with the Sphagnum species, the PyMC community for their helpful reference guide introducing Bayesian Additive Regression Trees68, and Arnstein Berg for assisting in collecting DOC samples. Many thanks to Paul Christiansen for help with soil coring and Tenna Melissa Nielsen for help with chemical analyses. This study is a contribution to the strategic research initiative LATICE (UiO GEO103920), the Center for Biogeochemistry in the Anthropocene, as well as the Center for Computational and Data Science at the University of Oslo.

Funding

This work was funded by the Norwegian Environment Agency (Monitoring Peatland Greenhouse Gas Fluxes after Rewetting), the European Research Council (Project 101116083), and the Novo Nordisk Foundation through the Global Wetland Center (research grant NNF23OC0081089).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.L. and N.P. conceptualized the research and are responsible for the experimental design of the study. A.I. and K.S.L. assisted with selection of the analytical instruments that were used. N.P. and A.I. conducted the eddy covariance data processing. M.B., A.V., and J.K.K. collected the DOC samples and estimated lateral discharge rates. P.H. and A.B. conducted the vegetation mapping. B.O. collected and analyzed the peat samples. M.B. analyzed the eddy covariance data and lateral carbon flux data and wrote the original draft of the manuscript. All co-authors provided feedback on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bekken, M.A.H., Vatne, A., Larsen, P. et al. Carbon dynamics of a controlled peatland rewetting experiment in the Norwegian boreal zone. Sci Rep 16, 1216 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30836-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30836-2