Abstract

The production of cultivated sea cucumber Stichopus horrens broodstock is urgently being carried out, considering the sharp decline of natural broodstock. Therefore, natural broodstock (F0) were spawned, and their larvae were reared in a hatchery until they metamorphosed into seeds (F1). Further cultured in the earthen pond for 16 months to reach broodstock size. After determining the sex by the evisceration method, males and females were cultured in separate concrete tanks measuring 2 × 1 × 1m3 to regenerate internal organs and gonad maturation, and fed with fresh grounded Sargassum sp. and Ulva sp. at 3% biomass. Eleven months later, the F1 broodstock was divided into three groups based on body weight: small (116.22 ± 9.81 g and 109.80 ± 5.72 g), medium (134.08 ± 7.48 g and 136.10 ± 12.78 g), and large (152.56 ± 190.01 g and 170.20 ± 7.92 g) for male and female, respectively. Five pairs from each broodstock group were spawned separately in fifteen 30 L polycarbonate tanks. The F1 broodstock could produce 180,000 to 820,000 eggs per broodstock, but not significantly different (P > 0.05) among broodstock size groups. The highest egg diameter (200.92 ± 18.18 μm) and larval survival were obtained in the large broodstock size group and were significantly different (P < 0.05) from the others. The highest hatching rate (82.12 ± 4.38%) was obtained in large broodstock size, followed by medium broodstock size, and was significantly different (P < 0.05) from the small broodstock size group. Mean F1 is suitable for domesticated broodstock, especially from large broodstock size groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sea cucumbers are marine invertebrates with high commercial value. One species that fishermen widely catch is Stichopus sp., locally named Gamat. This sea cucumber has a high collagen content and various metabolite compounds such as amino acids, polysaccharides, triterpene glycosides, carotenoids, vitamins, minerals, phenolic compounds, bioactive compounds, peptides, chondroitin sulfate, and saponins1,2,3,4,5.

This intense exploitation has led to a significant decline in natural sea cucumber populations. The imbalance between the level of sea cucumber captured and the low recruitment rate will accelerate the extinction of the sea cucumber population in its habitat. Therefore, to anticipate the extinction of sea cucumbers in nature, in this case, Stichopus sp., it is necessary to produce seeds from the hatchery.

Seed production efforts have been undertaken in the Gondol Marine Biota Scientific Conservation Area (MBSCA, Gondol) since 2022. It has shown significant progress, with larval survival to the doliolaria stage by 12–22%, which then metamorphoses into seeds6. Lately, the availability of natural broodstock has become increasingly limited, so the sustainability of the hatchery is expected to be carried out using domesticated broodstock. In aquaculture, the core of domestication is the total control of an organism’s life cycle, including its breeding activities7.

Successful domestication is when the entire life cycle of aquatic biota can be maintained in the cultivation system. The commodity in this study is Stichopus sp. The domestication carried out is almost perfect, where wild broodstock has been able to adapt to a new environment in captivity and controlled8, can utilize the feed provided so that it can grow and even be able to spawn and produce seeds9. In shrimp, the weight and age of the broodstock are targeted in the domestication process because they affect reproductive performance10,11,12. Generally, large broodstock tend to have better reproductive performance than small ones13. However, little is known about the reproductive performance of domesticated F1 broodstock of Stichopus sp., particularly in relation to broodstock size. Therefore, this study was conducted to obtain information on the reproductive performance of Stichopus sp. F1 broodstock in different size groups are used for hatchery and seed production activities.

Materials and methods

Maintenance of cultivated F1 broodstock

The Stichopus horrens F1 broodstock used in this study came from seeds produced in the hatchery of MBSCA, Gondol. The seeds cultivated in the pond are selected solely based on size, specifically 13.31 ± 3.17 g. They were then raised in an experimental earthen pond of the Institute for Mariculture Research and Fisheries Extension (IMRAFE), Gondol, Bali. Although cultivated under the same environmental conditions and fed for 16 months, they exhibit varied growth (54–151 g). At this size, from the same genus, S. chloronotus, the gonads have formed14, so this size is categorized as potential broodstock and used for sex determination.

Sex determination was conducted for 121 potential broodstock by injecting 0.2 µL of 0.5 M Potassium chloride solution (CAS 7447-40-7 Merck). Sixty-five were found as male with a length of 14.4 ± 2.7 cm and a weight of 77.8 ± 22.4 g, and 56 were female with a length of 14.5 ± 2.7 cm and a weight of 88.7 ± 28.2 g. Seventeen unknown sex with a length of 13.38 ± 2.3 cm and a weight of 45.7 ± 20.9 g were not used for further cultivation. After the sex was determined, the male and female were kept separately in two 2 × 1 × 1 m3 concrete tanks, fed with fresh grounded Sargassum sp. and Ulva sp., in a 2:1 ratio, 3% of the total sea cucumber biomass for the regeneration of internal organs and gonad maturation. In addition to the two feeds, the sea cucumbers eat benthos that grow on the walls and bottom of the tank. After 11 months of culture, they have reached a length of 17.9 ± 5.0 cm and a weight of 156.7 ± 52.2 g for males and 17.7 ± 5.2 cm and 137.7 ± 27.5 g for females, although gonad maturation was not verified histologically, body length and weight were used as practical proxies for reproductive maturity based on previous correlations reported in related species15.

Spawning of cultivated broodstock

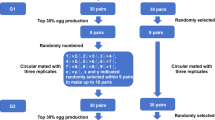

Before spawning, the F1 broodstock was measured, weighed. Total length is not used as a main component in grouping, because certain individuals tend to shrink at the time of measurement, even in non-stress conditions. So, the grouping was based on the broodstock body weight and divided into three size groups, namely small (S), medium (M), and large (L). The average length and weight of the male broodstock from the small size group (13.18 ± 2.03 cm; 116.22 ± 9.81 g), medium (15.0 ± 2.15 cm; 134.08 ± 7.48 g), and large (16.46 ± 3.28 cm; 152.56 ± 19.01 g) groups. The average length and weight of the female broodstock for the small size group (12.40 ± 1.14 cm; 109.80 ± 5.72 g), medium (14.20 ± 1.25 cm; 136.10 ± 12.78 g), and large (15.90 ± 2.56 cm; 170.20 ± 7.92 g) groups. Indeed, an overlap in body weight of male broodstock between the medium and large size groups, but this does not occur in female broodstock groups, and statistical analysis showed that both male and female broodstock groups are significantly different. After grouping small, medium, and large broodstock categories, five pairs were found to represent each group. According to their group, each female was placed in a polycarbonate container with a volume of 30 L. Then, the male was placed in a plastic basket and put into the container to prevent the male and female from mixing (Fig. 1). Each size group had five replicates, so the number of spawners was 15 pairs. Spawning is carried out for two consecutive days during the new moon period.

The seawater used for spawning passes through a sand filter and a 5 μm cartridge filter (Purerite PS-05, KEMFLO). After filtration, the seawater is stored in a concrete tank, sterilized using two 35-watt UV lamps (UV Lamp SAKKAI PRO 35 W) for 16 h, and is ready to transfer into the spawning tank. Each spawning tank is covered with black plastic to maintain a stable temperature.

Larvae rearing

Eggs produced from each pair of broodstock size groups are harvested and incubated for 24 h in 15 units of 100 L black plastic tanks according to treatment. After hatching, the larvae are stocked at a density of 200 individuals L− 1 in 15 units of an 80 L larval rearing tank. Previous research indicates that the feed for larvae to juveniles of the sea cucumber consists of Diatom species, whose nutritional value and size are suitable for larval mouth size and behaviour. Larvae were fed with Chaetoceros muelleri, Isochrysis galbana, Nitzchia sp., and Navicula sp. according to larval development (Table 1). The planktonic larval stage is fed with the smallest size and planktonic feed, namely Chaetoceros muelleri, followed by Isochrysis galbana and benthic diatom Nitzschia sp., and Navicula sp. is given after the larvae metamorphose into benthic pentactula.

Water replacement starts on the fifth day by slowly lowering the water by 20% and then adding UV-sterilized water using a plankton net. The water changes every two days. Water quality monitoring, including temperature, is carried out daily, while pH, dissolved oxygen, ammonia, and nitrite are monitored twice a week. After 40 days of rearing, larvae metamorphosed into juveniles, ready to harvest, and were kept in a nursery tank.

Data analysis

The variables observed include the length and weight of the broodstock, the number of broodstock spawning, the number of eggs, the egg diameter, the hatching rate, the development of the larvae, the survival rate, and the proportion of large, medium, and small juveniles at the end of the study. Egg diameter and total length of larvae were measured using a microscope connected to a camera (Nikon DXM 1200 F) and Win-Roof ver. 5.0 software.

The normality and homogeneity of all data sets were checked through the Non-Parametric One-Sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Levene Test, respectively (SPSS v. 20, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Differences among treatments were detected in One-Way ANOVA, followed by post hoc Tukey HSD. Data are expressed as mean SE of the mean (n = 10–15). The significance level was 0.05.

Results

Spawning of F1 broodstocks, fecundity, egg diameter, and hatching rate

Based on size and age, the F1 broodstock used in the study met the criteria for being a natural broodstock. Indeed, we realize that the number of broodstock used to obtain the same number of replications in each group is relatively small. However, based on this limitation, in two days of spawning trials, three pairs of each small, medium, and large size group broodstock were functionally reproductively mature and spawned with an average number of eggs: 489,600 ± 202,413, 420,000 ± 217,607, and 684,800 ± 215,556 eggs, respectively. Statistically, the number of eggs from the three broodstock size groups was not significantly different (P > 0.05) (Table 2). Since the environmental and handling of each broodstock pair were the same, their failure to reproduce was likely to have one male or female broodstock with immature gonads. Unfortunately, histological analysis was not conducted at the end of the study for two pairs from each size group that did not spawn.

The egg diameters in all size groups differed significantly (F2,6 = 22.149, P = 0.002), with the highest average found in the large size group (200.92 ± 18.18 μm), followed by the medium and small size groups of 174.22 ± 15.61 and 137.65 ± 12.47 μm, respectively. Meanwhile, the average hatching rate in the large size group (82.12 ± 5.37%) was not significantly different (P > 0.05) from the medium size group (67.84 ± 7.64%) but significantly different from the small size group (26.29 ± 8.52%) (F2,6 = 47.350, P = 0.000).

Larval development, survival rate, and percentage of juveniles

Larval development was not different in broodstock of different sizes. Early auricularia is characterized by a well-visible functional mouth, esophagus, cloaca, and ciliated band used for feeding and movement. Final auricularia is reached 13–15 days after hatching, and on the 17 − 21 days after hatching the larvae reach the doliolaria stage. Approaching the metamorphosis to the pentactula, the behaviour changes from planktonic to benthic larvae, the ciliated band disappears, five tentacles are visible, and the larvae move to the bottom of the rearing tank, occurring after 21 days after hatching (Figs. 2 and 3).

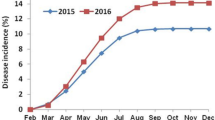

The survival of larvae 40 days after hatching was significantly different (F2,6 = 35.816, P = 0.000) between large-size groups and medium and small broodstock groups. Meanwhile, the medium and small-size broodstock groups did not significantly different (P > 0.05). The survival rate pattern of larvae for each size broodstock group is shown in Fig. 4.

Figures 5 and 6 show the average length and weight of juvenile S. horrens and the percentage of juvenile size groups. No separation of juvenile size groups was conducted because their sizes varied greatly, visually distinguishable into large, medium, and small size groups. Measurements and weighing can be done per individual for large and medium-sized juvenile groups. For small-sized juvenile groups, measurements can be done individually, but for weighing, a minimum of 6–10 individuals is required to be readable by the scale used. The analysis results show that each size group’s body length, weight, and percentage are not significantly different (P > 0.05).

Larval rearing water quality

The water quality parameters in the larval rearing, including temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen, ammonia, and nitrite, are presented in Table 3 and are still feasible to support sea cucumber larvae rearing.

Discussion

Spawning of F1 broodstock, fecundity, egg diameter, and hatching rate

Two-year-old S. horrens broodstock have succeeded in spawning for the three size groups studied, with a range of sizes; even small female and male broodstock groups with an average body weight of 105–125 g can spawn, as well as broodstock in large and medium groups. The broodstock used in this research is much larger than other species. The first gonad maturity in Actinopyga echinites was detected at a total weight of 65 g by Kohler et al.16, and Sembiring et al.17 reported that F1 broodstock H. scabra can spawn at an average body weight of 122.6 ± 32.37 g. This indicates that the nutritional reserves of the broodstock play an important role and can improve reproductive performance. The quantity and quality of these nutrient reserves determine the fecundity and quality of the eggs, as also mentioned by Schreck et al.18. Thus, the energy source required for embryo and larval development depends mainly on the broodstock’s nutrient reserves19.

The three-size broodstock groups show the same spawning frequency, and the number of eggs produced did not differ significantly, because there is a large difference in the number of eggs between individuals in one broodstock size group. Given that the broodstock used in this experiment is the same age, the maintenance from seed to broodstock is done under the same environmental and feed conditions. If the variation in the number of eggs produced in each broodstock size group does not vary significantly, then the larger the size of the broodstock, the higher the number of eggs that can be produced; thus, it can be concluded that the larger the size of the broodstock, the higher the spawning success. This is in line with Gianasi20, who reports that in Cucumaria frondosa, optimal environmental conditions can increase egg reproduction in addition to the broodstock’s size. Furthermore, apart from environmental conditions, other external factors that can affect broodstock productivity include the type of feed given, the maintenance container, the phase of the moon, and the season (photoperiod and temperature)21,22,23,24. Ru et al.25 also reported that sea cucumbers use nutritional sources to support gonad growth, so their reproductive performance depends on the availability and quality of food. The feed given to the broodstock during maintenance is ground Sargassum sp. and Ulva sp. In addition, the broodstock also eats benthos that grow naturally in the broodstock maintenance tank. Moreover, Wen et al.26 reported that A. japonicus and S. horrens prefer Sargassum sp. as food. Xu et al.27 also reported that the food source for Stichopus monotuberculatus comes from Sargassum sp., phytoplankton, and organic matter.

The average diameter of eggs from the three size groups of F1 broodstock S. horrens was significantly different (P < 0.05), with the highest individual average egg diameter (217.31 ± 18.51 μm) obtained from the large size group broodstock. Conand15 reported that the Stichopus variegatus begins maturing at a length of 270 mm and with an oocyte diameter of 180 μm, but its fecundity is only 10,000 oocytes. The egg diameter in this experiment is far bigger, even compared to the small-size group (132–154 μm). De La Rosa et al.28 state that the large egg’s diameter indicates a more significant food reserve that can support the development of the embryo and larvae when hatching, making these conditions excellent for the survival of sea cucumber larvae.

The egg-hatching rates of the large and medium groups differed significantly (P < 0.05) from the small groups. The highest hatching rate is obtained from the large group, followed by the medium-sized group, so the lowest hatching rate is in the small group. The condition of the female broodstock can affect egg quality and hatching rate. Marquet et al.29 reported that the egg-hatching rates of Holothuria arguinensis and H. Mamata were influenced by egg quality, fertility rates, and environmental conditions. The same has been reported in sea urchins Paracentrotus lividus30.

During spawning and egg incubation, salinity and temperature were maintained at 33–34 ppt and 30–31 °C for all broodstock size groups, and these ranges are optimum for most sea cucumbers, as reported by Hu et al.21. The salinity level is one of the significant environmental factors affecting the hatching rate. Tu et al.31 reported that the Japanese sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus can produce a high hatching rate at a salinity of 34 ppt. Asha et al.32 also noted that the optimal salinity range for hatching H. scabra eggs and rearing the larvae to the auricularia stage is 33–35 ppt. Furthermore, Falconer and Mackay33 also state that the phenotype of an organism is influenced by its genotype, environment, and interaction. In this study, large broodstock groups resulted in higher hatching rates. The higher hatch rate is likely due to increased maternal investment and better egg quality, rather than being attributed to an inherited trait.

Compared to the performance of the natural broodstock, which has a high egg production of 1–2 million eggs, the egg production of the F1 broodstock is still much lower, at 400,000–600,000 eggs. Environmental conditions in nature, which vary the availability of food, result in a higher fecundity of natural broodstock than domesticated broodstock, which is kept in tanks and fed a limited type of food. This difference in fecundity is likely related to higher nutrition due to the availability of more varied foods during broodstock rearing in ponds. During rearing in the concrete tank for the regeneration of the gastrointestinal tract and gonads, gonad maturation, and spawning of the broodstock, the feed given is limited to Sargassum sp., Ulva sp., and benthos that grow on the inner wall of the tank. Therefore, research on natural and artificial feeds for domesticated broodstock still needs to be continued. Cong et al.34 state that the variation in fecundity in sea cucumbers is related to the difference in the amount of food consumed by sea cucumbers.

Larval development, survival rate, and percentage of juveniles

The development of sea cucumber larvae from different broodstock size groups did not differ significantly (P > 0.05). Larvae of S. horrens of large broodstock size have a high survival rate and significantly differ from medium and small broodstock sizes. In addition, larger sizes have more energy sources to provide nutrients for the development of embryos and larvae when hatching, making this condition very favourable for the survival of larvae35. This can be seen from the diameter of the eggs produced by large-sized broodstock, which is more significant than the diameter of the eggs in other broodstock size groups. Morgan36 reports that Australostichopus mollis larvae from larger-sized broodstock tend to have better access to food sources in the early developmental phase, which supports increased growth and larval survival. Peters-Didier and Sewell37 reported a relationship between egg size and lipid content, as the lipid content in eggs is a significant energy reserve in the early development of Australostichopus mollis larvae. This makes it possible for larger broodstock sizes to provide more energy for each egg, which in turn has the potential to produce better larvae.

Some research results state that the larval development stage of the S. horrens sea cucumber is the same as that of other Aspidochirotes sea cucumbers38,39,40,41. The food and environmental factors during larval rearing significantly affect juvenile survival42. Water quality is important in a sea cucumber hatchery because larvae are susceptible to environmental changes43. In this study, water temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen, ammonia, and nitrite were relatively consistent and generally within the normal range for maintaining sea cucumber larvae of tropical holothurian species39,44.

Conclusion

Based on the result of the first generation of domesticated S. horrens of all broodstock size groups successfully spawned. Besides the significant variation in the number of eggs produced in each broodstock size group, the large broodstock group (170.33 ± 9.10 g) provides the highest egg diameter (200.92 ± 18.18 μm) and larval survival. These results emphasize that a large broodstock group is suitable for use as a broodstock-based hatchery. Considering that larval development and juvenile growth patterns are the same as those produced by natural broodstock, then juveniles produced from F1 Stichopus horrens broodstock are ideal for sustainable aquaculture.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sottoroff, I. et al. Characterization of bioactive molecules isolated from sea cucumber Athyonidium Chilensis. Revista De Biología Mar. Y Oceanografía. 48 (1), 23–35 (2013).

Pangestuti, R. & Arifin, Z. Medicinal and health benefit effects of functional sea cucumbers. J. Traditional Complement. Med. 8, 341–351 (2018).

Rahael, K., Rahantoknam, S. P. & Hamid, S. K. The amino acid of sandfish sea cucumber (Holothuria scabra): dry method with various feeding enzyme. Journal Physics: Conference Series. 1424, 012005 (2019).

Xing, R. et al. Authentication of sea cucumber products using NGS-based DNA mini-barcoding. Food Control. 129, 108199 (2021).

Yang, L., Wang, Y., Yang, S. & Zhihua Lv. Separation, purification, structures, and anticoagulant activities of fucosylated chondroitin sulfates from Holothuria scabra. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 108, 710–718 (2018).

Sembiring, S. B. M. The Survival, Growth, and accelerating morphological development of Stichopus horrens are affected by the initial larval stocking densities. Hayati J. Biosci. 32 (1), 233–240 (2025).

Liao, I. C. & Huang, Y. S. Methodological approach used for the domestication of potential candidates for aquaculture. Recent advances in Mediterranean aquaculture finfish species diversification. Zaragoza: CIHEAM, 97–107. Preprint at https://om.ciheam.org/article.php?IDPDF=600609 (2000).

Widiastuti, Z., Setiawati, K. M., Sembiring, S. B. M. & Giri, N. A. Utilization of seaweed to support sea cucumber domestication activities (Stichopus sp.). In Proceedings of the XVI Annual National Seminar on Fisheries and Marine Research, Department of Fisheries, Faculty of Agriculture, Gadjah Mada University, Yogyakarta. 50–54 (2019).

Setiawati, K. M., Widiastuti, Z., Sembiring, S. B. M. & Giri, N. A. Growth and reproduction performance of sea cucumber (Stichopus sp.) fed with different feed regime. E3S Web of Conferences. 322 (2021).

Coman, G. J. & Crocos, P. J. Effect of age on the consecutive spawning of ablated Penaeus semisulcatus broodstock. Aquaculture 219 (1–4), 445–456 (2003).

Nur, A., Yudhistira, A., Ruliaty, L. & Soleh, M. The effect of ages on reproductive performances of banana shrimp, Penaeus indicus. Media Akuakultur Indonesia. 2 (1), 65–112 (2022).

Racotta, I. S., Palacios, E. & Ibarra, A. M. Shrimp larval quality in relation to broodstock condition. Aquaculture 227 (1–4), 107–130 (2003).

Hoang, T., Lee, S. Y., Keenan, C. P. & Marsden, G. E. Effect of age, size, and light intensity on spawning performance of pond-reared Penaeus merquensis. Aquaculture 212 (1–4), 373–382 (2002).

Hoareau, T. & Conand, C. Sexual reproduction of Stichopus chloronotus, a fissiparous sea cucumber on reunion Island, Indian ocean. SPC Beche-de-mer Inform. Bull. 15, 4–12 (2001).

Conand, C. Ecology and reproductive biology of Stichopus variegatus an Indo-Pacific coral reef sea cucumber (Echinodermata: Holothuroidea). Bull. Mar. Sci. 52 (3), 970–981 (1993).

Kohler, S., Gaudron, S. M. & Conand, C. Reproductive biology of Actinopyga echinites and other sea cucumbers from La Réunion (Western Indian Ocean): implications for fishery management. Western Indian Ocean. J. Mar. Sci. 8 (1), 97–111 (2009).

Sembiring, S. B. M., Wibawa, G. S., Giri, N. A. & Haryanti, H. Reproduction and larval rearing of sandfish (Holothuria scabra). Mar. Res. Indonesia. 43 (1), 11–17 (2018).

Schreck, C. B., Contreras-Sanchez, W. & Fitzpatrick, M. S. Effects of stress on fish reproduction, gamete quality, and progeny. Aquaculture 197 (1–4), 3–24 (2001).

Huang, X. et al. Lipid content and fatty acid composition in wild-caught silver pomfret (Pampus argenteus) broodstocks: effects on gonad development. Aquaculture 310 (1–2), 192–199 (2010).

Gianasi, B. L. Exploring the potential of the sea cucumber Cucumaria frondosa as an aquaculture species. Thesis. Memorial University of Newfoundland, Canada. 292 (2018).

Hu, C. et al. Spawning, larval development and juvenile growth of the sea cucumber Stichopus horrens. Aquaculture 404-405, 47–54 (2013).

Laguerre, H. et al. First description of embryonic and larval development, juvenile growth of the black sea-cucumber Holothuria forskali (Echinodermata: Holothuroidea), a new species for aquaculture in the north-eastern Atlantic. Aquaculture 521, 734961 (2020).

Rakaj, A. et al. Spawning and rearing of Holothuria tubulosa: A new candidate for aquaculture in the mediterranean region. Aquac. Res. 49, 557–568 (2017).

Tehranifard, A., Uryan, S., Vosoghi, G., Fatemy, S. M. & Nikoyan, A. Reproductive cycle of Stichopus herrmanni from Kish Island, Iran. SPC Beche-de-mer Inform. Bull. 24, 22–27 (2006).

Ru, X., Zhang, L., Liu, S., Jiang, Y. & Li, L. Physiological traits of income breeding strategy in the sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus. Aquaculture 539, 736646 (2021).

Wen, B. et al. Effects of dietary inclusion of benthic matter on feed utilization, digestive and immune enzyme activities of sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus (Selenka). Aquaculture 458, 1–7 (2016).

Xu, Q. et al. Sea ranching feasibility of the hatchery-reared tropical sea cucumber Stichopus monotuberculatus in an inshore coral reef Island area in South China sea (Sanya, China). Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 918158 (2022).

De La Rosa, J. N. B., Pacheco-Vega, J. M., Godínez-Siordia, D. E., Espino-Carderin, J. A. & Yen-Ortega, E. E. Artificial reproduction and description of the embryonic, larval, and juvenile development of sea cucumber (Holothuria inornata semper 1868) with three different microalgae diets. Aquacult. Int. 32, 2905–2922 (2023).

Marquet, N., Conand, C., Power, D. M., Canário, A. V. M. & González-Wangüemert, M. Sea cucumbers, holothuria arguinensis and H. mammata, from the Southern Iberian peninsula: variation in reproductive activity between populations from different habitats. Fish. Res. 191, 120–130 (2017).

Guettaf, M., San Martin, G. A. & Francour, P. Interpopulation variability of the reproductive cycle of Paracentrotus lividus (Echinodermata: Echinoidea) in the south-western mediterranean. J. Mar. Biol. Ass U K. 80, 899–907 (2000).

Tu, P. T. C., Manuel, A. V., Huynh, G. T., Tsutsui, N. & Yoshimatsu, T. Impact of short-term salinity and turbidity changes on hatching and survival rates of Japanese sea cucumber, Apostichopus japonicus (Selenka, 1867), eggs. Asian Fisheries Sci. 35, 90–94 (2022).

Asha, P. S., Rajagopalan, M. & Diwakar, K. Influence of salinity on hatching rate, larval and early juvenile rearing of sea cucumber Holothuria scabra jaeger. J. Mar. Biol. Ass India. 53 (2), 218–224 (2011).

Falconer, D. S. & Mackay, T. F. C. Introduction To Quantitative Genetics 3th edn, 433 (Longman, 1989).

Cong, J. et al. Sex differences in the growth of sea cucumber (Apostichopus japonicus). Aquaculture 582, 740475 (2024).

Widyastuti, Y., Subagja, J. & Gustiano, R. Reproduction of selected and non-selected nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) with artificial induced breeding: character of broodstock, egg, embryo, and larvae. Jurnal Iktiologi Indonesia. 8 (1), 1–20 (2008).

Morgan, A. D. Assessment of egg and larval quality during hatchery production of the temperate sea cucumber, Australostichopus mollis (Levin). J. World Aquaculture Soc. 40 (5), 629–642 (2009).

Peters-Didier, J. & Sewell, M. A. Maternal investment and nutrient utilization during early larval development of the sea cucumber Australostichopus mollis. Marine Biology. 164(178), 1–14 (2008).

Chen, C. P. & Chian, C. S. Short note on the larval development of the sea cucumber Actinopyga echinites (Echinodermata: Holothuroidea). Bull. Inst. Zool. Acad. Sinica. 29 (2), 127–133 (1990).

Hu, C. et al. Larval development and juvenile growth of the sea cucumber Stichopus sp. (Curry fish). Aquaculture. 300 (1–4), 73–79 (2010).

McEuen, F. C. Spawning behaviors of Northeast Pacific-sea cucumbers (Holothuroidea: Echinodermata). Mar. Biol. 98, 565–585 (1988).

Ramofafia, C., Byrne, M. & Battaglene, S. C. Development of three commercial sea cucumbers, holothuria scabra, H. fuscogilva, and actinopyga mauritiana: larval structure and growth. Mar. Freshw. Res. 54 (5), 657–667 (2003).

Yu, Z., Wu, H., Tu, Y., Hong, Z. & Luo, J. Effects of diet on larval survival, growth, and development of the sea cucumber holothuria leucospilota. Hindawi Aquaculture Nutr. 2022(1), 10p Article ID 8947997 (2022).

Asha, P. S. & Muthiah, P. Reproductive biology of the commercial sea cucumber Holothuria spinifera (Echinodermata: Holothuroidea) from Tuticorin, Tamil Nadu, India. Aquacult. Int. 16, 231–242 (2006).

Knauer, J. Growth and survival of larval sandfish, holothuria scabra (Echinodermata: Holothuroidea), fed different microalgae. J. World Aquaculture Soc. 42 (6), 880–887 (2011). (2011).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all technicians at the sea cucumber hatchery for their technical assistance during the experiment and to the Directorate of Research and Innovation Funding, Deputy for Facilitation of Research and Innovation, National Research and Innovation Agency.

Funding

This research was funded by the Directorate of Research and Innovation Funding, Deputy for Facilitation of Research and Innovation, National Research and Innovation Agency (No. 61/II.7/HK/2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sari Budi Moria Sembiring and Ketut Maha Setiawati joined in all activities, from arranging the idea and designing the experiment, broodstock, larval and juvenile rearing, samples collection, larval measurement, statistical analysis, data interpretation, and preparation of the original draft. Jhon Harianto Hutapea, Gunawan Gunawan, Ananto Setiadi, and Ni Wayan Widya Astuti joined in conducting broodstock, larval and juvenile rearing, sample collection, larval measurement, and statistical analysis. Haryanti Haryanti and Nyoman Adiasmara Giri arranged the idea, designed the experiment, performed data interpretations, and prepared the original draft. Rarastoeti Pratiwi performed data interpretations and prepared the original draft. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript **.**.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sembiring, S.B.M., Setiawati, K.M., Hutapea, J.H. et al. Reproductive performance of the first generation Stichopus horrens broodstock. Sci Rep 16, 1167 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30858-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30858-w